86 Biopolitics as a Critical Diagnosis1

Why include a chapter on ‘biopolitics’ in the Handbook of Frankfurt School Critical Theory? Two reasons seem to speak against it: first, there is not a single work concentrating on ‘biopolitics’ from a canonical Frankfurt School-style critical theorist. In spite of the many disagreements in the debate on ‘biopolitics’, its starting point2 is routinely tracked to Michel Foucault’s conclusion in Le Volonté de Savoir3 that since the late nineteenth century we live in a new era of politics in which ‘the life of the species is waged on its own political strategies’ (Foucault, 1978 [1976], hereafter HS1: 143). The debate on ‘biopolitics’ is still prolific, even though Foucault almost completely ceased to use ‘biopolitics’4 after Le Volonté de Savoir: on the one hand, we find works that directly pick up Foucault’s genealogical enterprise and analyse biopolitics as a dominant form of power in both early and contemporary liberalism where politics has become the ‘politics of life itself’ (Rose, 2007; for an overview see Lemke, 2011 [2007]: esp. chapter 7). On the other hand, ‘biopolitics’ has been turned into a proper philosophical concept: Giorgio Agamben takes biopolitics to produce the ‘bare life’ whose ‘inclusive exclusion’ is sovereign power’s fundamental mechanism (Agamben, 1998 [1995]: 6–9), Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri see biopolitics as the new mode of sovereign power’s ontology in the age of Empire, bringing forth the very subjects capable of resisting it (Hardt and Negri, 2000: 22–30), and Roberto Esposito (2008 [2004]) attempts to do justice to both sides of biopolitics by reading it through the ‘paradigm of immunization’.5

Nowhere in this debate do we find a voice belonging to the ‘Frankfurt School’ tradition in critical theory. Even worse – and this is the second reason why ‘biopolitics’ might seem an unlikely candidate for this Handbook – Le Volonté de Savoir is a frontal attack on analyses of a repressed sexuality like Herbert Marcuse’s (1998 [1956]) Eros and Civilization, himself of course a prominent member of the Frankfurt School. In 1978, Foucault used precisely the argument of Le Volonté de Savoir to mark his distance to the Frankfurt School: ‘I don’t think that the Frankfurt School can accept that what we need to do is not to recover our lost identity, or liberate our imprisoned nature, or discover our fundamental truth; rather, it is to move toward something altogether different’ (Foucault, 1998 [1980]: 275; on Marcuse as target, see Foucault, 1980 [1975]; 2001 [1981]: 1016 f.).

Despite these two reasons I argue that the ‘stature’ of Foucault’s model of critique is very similar to that of the early Frankfurt School’s model of critique. I do so by closely re-reading Foucault’s usage of ‘biopolitics’ in Le Volonté de Savoir and by highlighting two methodological affinities: one relates to Foucault’s subtle distinction between a critical and a descriptive conceptualisation of ‘biopolitics’ to Horkheimer’s (2002 [1937]) famous distinction between critical and traditional theory. This affinity becomes visible only when we pay close attention to Foucault’s model of critique and the role ‘biopolitics’ plays in it. Explaining Foucault’s model of critique enacted in Le Volonté de Savoir will reveal a second affinity between Foucault’s and Adorno’s model of critique: both conceive critique as a diagnostic practice of the present producing a very special, effective knowledge capable of emancipating us from that present. And although both affinities have their limits – they show us similarities in the ‘stature’ of critique, not in its inner details – they disclose something important in the debate about biopolitics mentioned above: the distinction between critical and descriptive roles of ‘biopolitics’, made possible by the conception of critique as producing effective knowledge, enables us to understand how ‘biopolitics’ is supposed to help us criticise our contemporary world – and how this might fail.

I start by arguing that we should understand Foucault’s critique as a diagnostic practice of prefigurative emancipation and briefly sketch the affinity to Adorno’s model of critique. This enables us to understand the critical function of ‘biopolitics’ in Le Volonté de Savoir as opposed to the descriptive role of ‘biopolitics’ Foucault afterwards hinted at. And I argue that this distinction mirrors Horkheimer’s famous distinction between critical and traditional theory in two important respects. I conclude with three implications for critical theory drawn from the analysis of the critical function of ‘biopolitics’.

Critique as a Diagnostic Practice

Foucault’s model of critique has been subject to a variety of interpretations:6 prominent readings have focussed on the ‘critical attitude’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 24) and the ethical dimension of critique as a practice of the self (Butler, 2004 [2001]), on the ‘art of not being governed quite so much/like this [tellement]’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 29) and the subversive dimension of critique as a practice of resistance (Lemke, 2012: chapter 4) or on the genealogical method and the disruptive effects of critique as a practice of revealing the historical contingency of seemingly necessary contemporary realities (Geuss, 2002; Saar, 2008; Koopman, 2013).

Instead, I start from Foucault’s account of his approach as an analysis of practices and the ‘experiences’7 they constitute: objective yet constructed realities like madness, criminality and sexuality. Foucault analyses them along the three axes of knowledge, power and self-relations and therefore elaborates conceptual frameworks for each of the three axes. Although developed successively and with an almost flamboyant terminological plurality, they share a certain negativism embodied in three methodological imperatives which Foucault names nihilism, nominalism and historicism (Foucault, 2010 [2008]: 5 f., footnote): the three conceptual frameworks are nihilistic because they ‘perform a systematic reduction of value’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 51); and they are nominalistic and historicistic because they reject universals as the guidelines of analysis, asking instead when and how these universals were themselves produced and transformed in the practices which are to be analysed (see Vogelmann, 2017a: 46–50).

If we accept this self-interpretation of Foucault’s approach, then its critical power resides precisely in his methodological perspective. Foucault’s practice of critique therefore is, first and foremost, a very specific knowledge-producing practice: a diagnostic of the present that produces counter-truths. These counter-truths effect what I shall call a ‘prefigurative emancipation’: glimpses of desubjugation and desubjectivation. On this interpretation, Foucault’s model of critique shares important traits with Adorno’s, most notably the fundamental idea of critique producing effective knowledge.

A Diagnosis of the Present

Understanding the critical activity as a kind of diagnosis follows directly from Foucault’s self-interpretation because the three conceptual frameworks of all three axes are utilised as tools to analyse the present.

On the axis of knowledge, Foucault’s most important conceptual innovation is his distinction between ‘depth knowledge’ [savoir]8 and knowledge [connaissances] as we know it: whereas knowledge in the sense of connaissances are statements to which we can assign a truth value, ‘depth knowledge’ in the sense of savoir consists of the conditions of existence (not of possibility!9) for a statement such that it can have a truth value. The analysis of practices along the axis of savoir therefore is directed at the conditions which must be in place for practices to produce statements eligible for truth values – the conditions of existence for being ‘within the true’, as Foucault (2010 [1969]: 224) says in reference to Georges Canguilhem. This methodological shift takes us from an analysis of the truth values of statements to the analysis of the conditions of existence for statements to be able to have truth values – because diagnosing these conditions of existence has a political significance, Foucault (2008 [2004]: 36 f.) claims: it shows us what needed to be done for certain statements to be ‘within the true’: what struggles had to be fought, what power relations needed to be established and what subjectivities had to be formed. The conceptual framework on the axis of knowledge is designed to enable this critical diagnosis.

We find an analogous ‘shift’ on the axis of power. As a general concept, power has to be understood as relational, strategic and productive: power is neither a thing possessed, nor contingent on the will of a subject, nor merely a repressive force. Power relations are fragile, exist only when exercised and can incite and induce as well as constrain and repress (HS1: 92–7; 1998 [1982]: 340–5). Most importantly, power must not be reduced to any particular type of power relations, be they juridical, disciplinary or regulatory. Foucault focusses on how power relations operate instead of asking whether they are legitimate or not – again, as with knowledge not being analysed in the categories of truth and falsehood, we see Foucault enacting a ‘systematic reduction of value’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 51). And again, he argues for it by pointing out that freeing the diagnostic concept of power from a narrow ‘juridico-discursive’ (HS1: 82) understanding enables a critical diagnosis. Hence Foucault insists that ‘[k]nowledge and power are only an analytical grid’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 52), that they are not ‘entities, powers [puissances] or something like transcendentals’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 51) and that they ‘only have a methodological function’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 51).

Foucault’s notion of self-relations again introduces a methodological shift in perspective to enable a critical diagnosis of ‘the forms and modalities of the relation to self by which the individual constitutes and recognizes himself qua subject’ (Foucault, 1990 [1984]: 6). Focussing on self-relations and how they are enacted liberates the analysis from two values commonly presupposed: authenticity and autonomy. Foucault’s analysis of the practices in which the self is able to participate and influence its own formation is carefully crafted in order to show that the questions whether this self is a ‘true self’, an authentic or autonomous self, are so pressing to us only because they belong to our self-practices. Yet they do not belong to subjectivity in general and we should not, in Foucault’s view, integrate them in our diagnostic concepts.

Using these three conceptual frameworks of knowledge, power and self-relations, Foucault’s critique aims at a diagnosis of the present that renders visible how ‘what exists’ limits us in our thoughts, in our actions and in our being (Foucault, 1998 [1983]: 449 f.). Revealing these limits and how they are produced in our contemporary practices demonstrates that these limits are not inevitable but can be changed by changing our practices. Hence we need to search for ‘weak spots’ in those practices currently solidifying our limitations.

Foucault presents his model of critique as an inversion of Kant’s critique because it does not search for the universal limits of reason but for the concrete limits of our present, and not in order to safely keep reason inside those limits but in order to emancipate us from them (Foucault, 1997a [1984]: 315; 2010 [2008]: 11–14, 26 f.). Hence Foucault’s critique has a difficult relation to truth: the critical diagnosis of the present does not result in a representation of reality but attempts to formulate an effective truth that operates in reality through its impacts on its readers (Foucault, 1998 [1980]: 242–6) – aiming at ‘a transformation of the relationship we have with our knowledge’ (Foucault, 1998 [1980]: 244). Such a rupture on the level of ‘depth knowledge’ [savoir], Foucault claims, leads to moments of ‘desubjugation’ and ‘desubjectivation’ – prefiguring our emancipation.

Counter-Truths

If desubjugation and desubjectivation are to be achieved with a diagnosis of the present, and hence with the production of a specific knowledge, we have to ask: what kind of knowledge is supposed to be so effective? Obviously critique cannot aim at desubjugation and desubjectivation by repeating what we already know. But neither does it suffice to falsify what is commonly supposed to be true. Both operations would still take place at the level of knowledge [connaissances] as true or false statements but would fail to address the conditions of existence that determine what statements can have truth-values at all. Critique as a diagnosis of the present must therefore produce counter-truths that do not submit to the rules of the current conditions of existence of true-or-false knowledge (our current ‘truth-regime’10). The knowledge of a diagnosis of the present must challenge this truth-regime and thus the conditions of existence that grant contemporary knowledge [connaissances] its place ‘within the true’. For only on the level of ‘depth knowledge’ [savoir] will ‘the system of truth and falsity […] reveal the face it turned away from us for so long and which is that of its violence’ (Foucault, 2014 [2011]: 5). Hence it is only on this level that the diagnosis acquires political significance.

Counter-truths make up an ‘unwieldy knowledge’ that stubbornly refuses to submit to the rules of the existing truth-regime without completely disregarding it. Instead it toys with the knowledge [connaissances] currently ‘within the true’ by relating to it on the level of savoir and thereby opposing it without disproving it, without taking it to be false. Unwieldy knowledge tries to change the current truth-regime by revealing the political significance of its truths: it demonstrates what struggles had to be fought and what alternative forms of knowledge had to be subjugated in order to arrive at the solemn truths we are now accustomed with.

Producing counter-truths escapes contemporary truth ‘not by playing a game that [is] totally different from the game of truth, but by playing the same game differently’ (Foucault, 1998 [1984]: 295) because counter-truths contest the conditions of existence of statements to be true or false. Therefore they are neither true nor false according to the present truth-regime – hence Foucault repeatedly speaks of ‘fictions’: if his books challenge the current truth-regime, they are neither true nor false according to this truth-regime but lead readers to relate differently to the book’s subject, to form or at least to anticipate a different ‘experience’ of madness, of criminality, or of sexuality. If critique as a diagnosis of the present challenges the truth-regime by producing unwieldy knowledge, it creates (a glimpse of) a new experience, a new correlation of those three axes.

Désassujettissement: Desubjectivation and Desubjugation

How are desubjugation and desubjectivation connected to this practice of producing unwieldy knowledge via a diagnosis of the present? The connection can certainly not be too close, for taking the production of unwieldy knowledge to directly liberate us from contemporary power relations and modes of subjectivation would be a gross overestimation of the effects of (academic) knowledge production. Critique is ‘an instrument for those who fight, those who resist and refuse what is’ (Foucault, 1998 [1978]: 236), but it cannot replace those struggles.

Still, we should not underestimate the effects of critique as a diagnosis of the present. Desubjectivation and desubjugation are prefigured by it: Foucault’s critique enables its addressees to anticipate their emancipation from the limits of our thoughts, actions and beings that the diagnosis reveals.11 Desubjectivation becomes possible because the critique’s diagnosis invites its addressees to change their perspectives on how they establish their self-relations or on the practices of the self they participate in – to the point where they feel they no longer want to be who they are, maybe no longer have to be who they are and ideally do not already have to be someone else.12 And although the practice of critique aims for an ethos, a critical attitude, we should not interpret it as primarily an ethical practice of the self because the primary aim is to desubjectivate: to place critique’s addressees on the intersection of ‘no longer’ and ‘not yet’ – no longer having the self-understanding they thought was necessary and ‘not yet’ having to have another self-understanding but enjoying a precious (and no doubt short-lived) moment of indeterminacy.

Critique’s aim of desubjugation likewise demands that critique must not prescribe what to do. As a diagnosis, critique gives ‘tactical pointers’ (Foucault, 2007 [2004]: 18) for those who fight13 – tracing the ‘lines of fragility’ mentioned above – but does not lead those who fight. Critique is not an alternative form of governing, but aims to make its addressees imagine the anarchic moment of no longer being ‘governed like that and at that cost’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 29). The unwieldy knowledge that critique produces reveals those practices that shape and uphold the conditions of existence of the present truth-regime. Thus, Foucault demonstrates that the necessity of the ‘experiences’ he analyses, of madness, criminality, sexuality, etc., is forged, both real and fabricated. These experiences are made necessary through certain practices which are therefore those practices against which to fight makes a difference not just to those practices.

In sum, Foucault’s critique is a practice of diagnosing the present by analysing practices and the ‘experiences’ they produce along the three axes of knowledge, power and self-relations. These three axes operationalise his methodological perspective characterised by the three methodological imperatives of nihilism, nominalism and historicism in order to produce unwieldy knowledge or counter-truths: truths which oppose our contemporary truth-regime on the level of depth-knowledge and thereby enable the addressees of Foucault’s critique to anticipate thinking, acting and being different – to be desubjectivated and desubjugated, if only for a spell.

The First Affinity: Adorno’s Riddles

Before I show how Le Volonté de Savoir enacts this complex model of critique let me demonstrate a certain affinity between Foucault’s and Adorno’s models of critique on the methodological level. Affinities between Adorno’s and Foucault’s models of critique have of course been explored, albeit from different angles, for example by focussing on Adorno’s and Foucault’s shared concern for ‘bodily freedom’ (Honneth, 1986), on the Kantian heritage of their models of critique (Cook, 2013), or on their view on history (Allen, 2016: chapter 5), to name just a few. My remarks add to this ‘comparative spadework’ (Cook, 2013: 966) but emphasise the ‘methodological’ affinity resulting from a similar expectation about the effects of critique’s knowledge.14

We can start by noticing that Adorno, like Foucault, conceives critique as a diagnostic practice that produces a very specific knowledge: critique, or philosophy in its proper form,15 is an interpretative practice (Adorno, 1977 [1973]: 126) the task of which is not to give meaning and legitimacy to the reality it interprets but to acknowledge the ‘incomplete, contradictory and fragmentary’ nature of our present, to make visible the violence reigning supreme, and to ‘banish’ these ‘demonic forces’ (Adorno, 1977 [1973]: 126). Critique, in other words, has to diagnose the present which does not mean simply to map reality but to change it:

Just as riddle-solving is constituted, in that the singular and dispersed elements of the question are brought into various grouping long enough for them to close together in a figure out of which the solution springs forth, while the question disappears – so philosophy has to bring its elements, which it receives from the sciences, into changing constellations, or, to say it with less astrological and scientifically more current expression, into changing trial combinations, until they fall into a figure which can be read as an answer, while at the same time the question disappears. (Adorno, 1977 [1973]: 127)

Adorno understands critique as a practice of diagnosing the present – ‘the state of the world rushing toward catastrophe’ (Adorno, 2005 [1962]: 13) – and thereby articulating a knowledge that frees us from that present. A successful critique would dissolve the present that gave rise to its diagnosis because of this diagnosis. Again, we would have to ask precisely how we can understand this strikingly effective critical knowledge – a question I cannot pursue here.16 Yet the parallel to Foucault’s perspective on critique and to his expectations towards the knowledge critique has to produce is apparent.

A second commonality in their methodological perspective is the negative conception of emancipation: if critique, by constructing its diagnostic constellations, dissolves the very reality thus interpreted, critique is precisely an emancipating practice in the negative sense of emancipation as ‘letting go’. Since Adorno holds that critical theory’s ‘utopian moment […] is stronger the less it […] objectifies itself into a utopia’ (Adorno, 2005 [1969]: 292), emancipation cannot be thought of as a positive state of affairs to be achieved. Instead, the emancipation critique strives for is, for both Adorno and Foucault, ‘an Ausgang, a way out of our infernal present’ (Cook, 2013: 974). Thus, Adorno’s critique is not meant to tell its addressees what to do or to think – at most it offers a model of practiced resistance as a life lived less wrongly and glimpses of what an emancipated life might be (Freyenhagen, 2013: 170).

These two similarities in the methodological perspectives of Adorno and Foucault are not meant to turn Foucault into ‘Adorno’s other son’ (Allen, 2016: 163). Yet they remind us of the shared expectation of Foucault and the early Frankfurt School that critique is to produce an effective, unwieldy knowledge that frees us from our present, even if only temporarily.

The Critical Role of ‘Biopolitics’

Le Volonté de Savoir applies this complex model of critique and ‘biopolitics’ names the unwieldy knowledge of that critical diagnosis – or so I argue. I begin by demonstrating that Foucault uses the methodological perspective outlined above. In a second step, I show that ‘biopolitics’ has a critical function in the final part: it names the counter-truths with which Foucault’s critique intends to prefiguratively emancipate his readers. I argue that Foucault’s development of ‘biopolitics’ into the object of analysis and contemporary work continuing in this direction turn ‘biopolitics’ into a descriptive concept that stands in need of another critical diagnosis. Finally, I draw attention to the affinity of this distinction with Max Horkheimer’s famous differentiation between traditional and critical theory.

The Methodology of Le Volonté de Savoir, Parts 1–4

What is the book’s target? Sexuality, obviously, though not ‘sexual behaviors in Western societies’ but the way ‘in which […] these behaviors [have] become the object of a knowledge’ (Foucault, 2002 [1977]: 11). His critique is directed against the ‘experience’ of sexuality,17 its constitutive practices and the prominent idea of sexuality being repressed by power. This ‘repressive hypothesis’ (HS1: 10) rests on a mistaken view of power and sexuality – yet it is a mistake that pays off:

What sustains our eagerness to speak of sex in terms of repression is doubtless this opportunity to speak out against the powers that be, to utter truths and promise bliss, to link together enlightenment, liberation, and manifold pleasures; to pronounce a discourse that combines the fervor of knowledge, the determination to change the laws, and the longing for the garden of earthly delights. (HS1: 7)

Any analysis relying on the repressive hypothesis must assume that the power most important for constituting our contemporary experience of sexuality is a negative, repressive form of power; that truth is apriori set apart from and against power; and that sexuality holds important truths about us. Foucault’s aim is precisely to overcome all of these three preconceptions. His refutation of the repressive hypothesis (in parts 2 and 3) is directed against the historical thesis that sexuality has been increasingly repressed since the seventeenth century, against the historical–theoretical thesis that the power relations predominantly take a negative form and against the historical–political thesis that the critique of repression is a form of resistance to the power relations that dominate the experience of sexuality (HS1: 12). Instead, he argues that the discourse on sexuality has not been repressed but incited, that repressive power is just one but not the most important form of power exercised in the ‘dispositif’18 of sexuality, and that speaking the truth about sex has not simply been avoided. On the contrary, ‘we’ have worked hard to establish the conditions of existence to make true or false statements about sexuality, to found the ‘Scientia sexualis’. The will to truth is precisely what characterises ‘our’ experience of sexuality (HS1: especially 67–70).

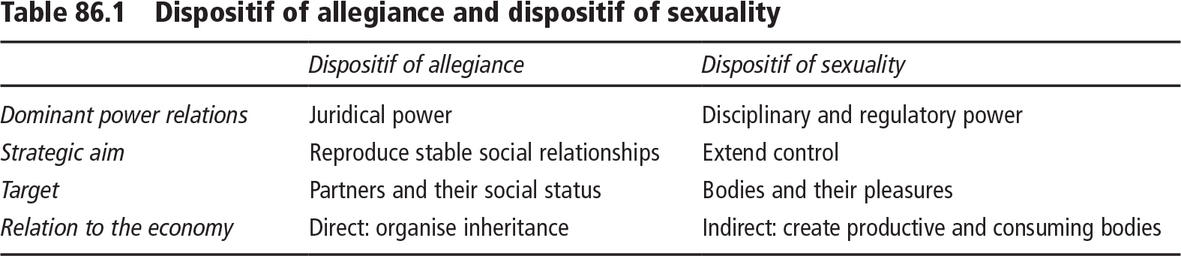

Only now can Foucault proceed with his positive analysis of the ‘experience’ of sexuality. After rejecting the juridical analysis of power and introducing his relational, productive and strategic notion of power (the diagnostic concept I have outlined above) Foucault argues that the dispositif of sexuality is constituted by four ‘great strategic unities’ (HS1: 103): the hysterisation of women’s bodies, the pedagogisation of children’s sex, the socialisation of procreative behaviour and the psychiatrisation of perverse pleasure (HS1: 104 f.). Sexuality is the ‘experience’ produced in the practices of these four strategies and Foucault contrasts this dispositif of sexuality with the dispositif of ‘alliances’ (see Table 86.1). Yet the dispositif of sexuality has not replaced the dispositif of alliances but overdetermines it. The linkage is provided by the family, and psychoanalysis, Foucault claims, rests precisely in this interstice.

This very schematic sketch of Foucault’s argumentation renders visible his methodological perspective. He reconceptualises power by freeing it from the dominant normative framework in which it is usually thought, namely in terms of legitimation. Cutting off the king’s head in political science (HS1: 88 f.) means nothing more (and nothing less) than getting rid of the conceptual analysis of power in juridical terms and thus corresponds precisely with the nihilistic ‘systematic reduction of value’ (Foucault, 1997 [1978]: 51).

Conceptualising power strictly relationally operationalises the nominalistic methodological imperative: ‘One needs to be nominalistic, no doubt: power is not an institution, and not a structure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; it is the name that one attributes to a complex strategical situation in a particular society’ (HS1: 93). Hence, power is not an entity or a transcendental category but a diagnostic concept designed to make visible the wide range of very different and ever-changing power relations within society.

Finally, Foucault provides a historical explanation why we have come to analyse power purely in juridical terms. The historistic dimension of his methodological perspective entails that the concept of power cannot be anything more than a heuristic device leading the historical analysis of concrete techniques, mechanisms and strategies of power at a certain place and at a certain time.

While Foucault develops his concept of power on the methodological level in the book, he presupposes the already existing conceptual tools for analysing knowledge from this methodological perspective throughout. Analysing the ‘will to knowledge’ that drives the discourse on sex and that has constituted sexuality as a domain ‘within the true’ relies on the distinction between knowledge [connaissances] and depth-knowledge [savoir]. For only if the conditions of existence for statements to have truth-values are not epistemic conditions can we avoid the Aristotelian model in which the ‘desire to know is no more than a game of knowledge in relation to itself, it does no more than show its genesis, delay, and movement’ (Foucault, 2014 [2011]: 16). And only then can we analyse the social struggles in and through which the regime of truth on which our ‘Scientia sexualis’ is founded.

Although the third axes of self-relation is not yet present, Foucault’s methodological perspective operationalised with the conceptual apparatuses on the first two axes is almost fully developed and is designed to analyse sexuality nihilistically, nominalistically and historicistically. Thus we find Foucault enacting precisely the model of critique described above: a nihilistic, nominalistic and historicist diagnosis of sexuality as an ‘experience’ produced by practices that must be analysed along the analytic axes of knowledge and power. And ‘biopolitics’ is the name, as I shall argue, of the ‘counter-truths’ which are produced by Foucault’s critique and which are supposed to desubjectivate and desubjugate us from the ‘experience’ of sexuality. In other words: ‘Biopolitics’ in Le Volonté de Savoir has the critical function of emancipating us from sexuality – or of at least offering us a glimpse of what that might be like.

Biopolitics and Pleasures: Counter-Truths

Part 5 of Le Volonté de Savoir, entitled ‘Right of Death and Power over Life’, opens with the contrast between sovereign power – the asymmetrical ‘right to take life or to let live’ (HS1: 136) – and biopower: a new form of power in ‘the West’ (HS1: 136)19 that is first and foremost ‘a power that exerts a positive influence on life, that endeavors to administer, optimize, and multiply it, subjecting it to precise controls and comprehensive regulations’ (HS1: 136). Although this power has not lost but amplified its ability to kill, its elaborate mechanisms to do so are merely the backside of its incomparably more developed mechanisms to foster and regulate life.20

Foucault’s readers know the claim that power ‘in the West’ has fundamentally changed: in Discipline and Punish, Foucault argued that disciplinary power mechanisms targeting the individual body to render it docile and productive have become the dominant form of power relations (Foucault, 1977 [1975]: 215–28). Yet this is but one half of biopower, Foucault now explains: whereas disciplinary power relations ‘centered on the body as a machine’ (HS1: 139), biopolitical power relations target the body as a living organism understood biologically and regulate processes on the level of the species. Politics no longer takes ‘biological life’ as a given but fosters, regulates and shapes it on the level of the very processes constituting it as ‘living’.21 Thus we return to Foucault’s claim with which I began this chapter: that our present is characterised by the fact that ‘the life of the species is waged on its own political strategies’ (HS1: 143).

What’s sex got to do with it? Sexuality is precisely what links the two poles of biopower: on the individual level, it enables disciplinary micro-practices controlling and optimising the individual body; on the level of the population, sexuality enables regulatory control mechanisms (HS1: 146). The four ‘strategic unities’ that constitute the ‘experience’ of sexuality all combine disciplinary and biopolitical mechanisms, Foucault claims:

The first two [of these strategic units; F. V.] rested on the requirements of regulation, on a whole thematic of the species, descent, and collective welfare, in order to obtain results at the level of discipline; the sexualization of children was accomplished in the form of a campaign for the health of the race […]; the hysterization of women, which involved a thorough medicalization of their bodies and their sex, was carried out in the name of the responsibility they owed to the health of their children, the solidity of the family institution, and the safeguarding of society. It was the reverse relationship that applied in the case of birth controls and the psychiatrization of perversions: here the intervention was regulatory in nature, but it had to rely on the demand for individual disciplines and constraints [dressages]. (HS1: 146 f.)

At this point, the critical function of the concepts ‘biopolitics’ and ‘biopower’ become apparent: the diagnosis of our present as the biopolitical age reveals the ‘political significance’ of the will to truth that manifests itself vis-à-vis sexuality and that dominates even the apparent resistance against its repression. All those practices looking for truth within sexuality – whether to ground control over individuals and populations by recourse to the ‘natural facts’ of sexuality or whether to resist the repression of sexuality – are still part of the regime of practices that constitutes ‘sexuality’ as an object of our desire to know that is carefully nurtured and put to use by the biopolitical power relations. Thus, the attempt to deploy ‘truths’ of sexuality against its ‘repression’ is complicit in enabling the biopolitical and disciplinary power mechanism. ‘Irony of this dispositif: it makes us believe that what is at stake in it is our “liberation”’, as Foucault (HS1: 159) writes in the very last sentence of the book.22

On my methodological reading of Le Volonté de Savoir then, ‘biopolitics’ names those counter-truths of Foucault’s critical diagnosis which challenge the discourse of sexuality on the level of its conditions of existence. They do not attempt to disprove the discourse on sexuality – as untrue or ideological – but reveal the struggles necessary to establish and sustain its ability to form statements with truth-value at all. They enable us to realise that even our strategies of resistance and their theoretical foundations only lead us deeper into what we believe to fight against. The desubjectifying and desubjugating effects of these counter-truths summarily named ‘biopolitics’ derive directly from this opposition on the level of depth-knowledge: for the consequence of accepting Foucault’s diagnosis would be to rid ourselves of all self-conceptions related to the dispositif of ‘sexuality’ and to fight in order to free ourselves from biopower.

At precisely this point, Foucault imagines a future which can no longer understand our will to truth about sex because it belongs to another regime of truth from which our fascination with sexuality, our hopes towards and our demands of it seem strange and astonishing. Foucault does not attempt to depict this new world but he deems its prefiguration necessary:

[…] we must dream [devons songer] that perhaps one day, in a different economy of bodies and pleasures, people will no longer quite understand how the ruses of sexuality, and the power that sustains its dispositif, were able to subject us to that austere monarchy of sex, so that we became dedicated to the endless task of forcing its secret, of exacting the truest of confessions from a shadow. (HS1: 159, my emphasis)23

Biopolitics thus names the counter-truths resulting from a critical diagnosis that reveals how the dispositif of sexuality limits us in our thoughts, our actions and our subjectivities and how attempts to ‘free’ our own ‘repressed’ sex are driven by the very will to truth that has established the biopolitical and disciplinary power mechanisms shaping our actions and our subjectivities. The critical function of the concept of biopolitics is precisely to show us the full extent to which we are ‘captured’ by the dispositif of sexuality, to estrange us from it and to thereby give us a glimpse of what a truly emancipated life would entail.

After La Volonté de Savoir

Biopolitics quickly vanishes from Foucault’s vocabulary, even though Foucault starts his lecture course in 1978 with the stated intention to study ‘something that I have called, somewhat vaguely, bio-power’ (Foucault, 2007 [2004]: 1) and announces in 1979 that ‘only when we know what this governmental regime called liberalism was, will we be able to grasp what biopolitics is’ (Foucault, 2008 [2004]: 22). The course summary dryly admits that the lecture course was devoted ‘entirely to what should have been only its introduction’ (Foucault, 2008 [2004]: 317), namely the analysis of (neo-)liberalism as a political rationality: as a specific regime of truth of governmental practices (see Vogelmann, 2012; Oksala, 2013).

This does not necessarily mean that Foucault abandoned the study of biopolitics. Some scholars argue that Foucault’s notion of governmentality is ‘nothing else than the name of a new analytical perspective on biopolitics’ (Muhle, 2008: 269, my translation).24 If we consider ‘governmentality’ to be a further development of Foucault’s ‘analytics of power’, as he himself suggests (Foucault, 2007 [2004]: 118–20; see Patton, 2015: 113; for an opposing view cf. Fassin, 2010: 185 f., 196), this would continue the argument from Le Volonté de Savoir stringently: developing the concept of power in order to analyse sexuality without presupposing the repressive hypothesis left us with the critical diagnosis of biopolitics – and its analysis again is in need of new conceptual tools. So with the methodological perspective offered by the concept of governmentality, we can envision an ‘analytics of biopolitics’ (Lemke, 2010: 432–4; 2011 [2007]: chapter 9; Rabinow and Rose, 2015 [2006]: 308–23) along the three axes of knowledge, power and self-relations (see Lemke, 2010: 432 f.): on the axis of knowledge, the most pressing question is how ‘life’ is made knowable. On the axis of power, we have to analyse what is done with this knowledge and what relations of power sustain the ‘regime of truth’ that supports this knowledge. Finally, on the axis of self-relations, we analyse the impact of this knowledge and of these power relations on the self-understanding of subjects and their constitution.

However, while continuing Foucault’s methodological perspective, this changes the status and the function of ‘biopolitics’: instead of a critical concept naming the counter-truths which result from Foucault’s diagnosis of the present, ‘biopolitics’ now is a descriptive concept that names the object analysed. ‘Biopolitics’ was intended to estrange, to prefiguratively emancipate readers from their investment into the truths of sexuality. By taking the conceptual space that ‘sexuality’ occupied in Le Volonté de Savoir, it loses this function – and consequently the ‘analytics of biopolitics’ must either produce new counter-knowledge or proceed with a different model of critique.

The Second Affinity: Horkheimer’s Critical Knowledge

Distinguishing between ‘biopolitics’ as a critical concept that names the counter-truths produced by Foucault’s diagnostic critique of the dispositif of sexuality and ‘biopolitics’ as a descriptive concept designating the object of critique brings us to the second affinity with Frankfurt School Critical Theory: for it mirrors Horkheimer’s famous distinction between critical and traditional theory – or so I claim.

How to understand Horkheimer’s distinction is of course itself contested but the following two aspects should be uncontroversial. A first key difference between critical and traditional theory is that the latter aims at correctly mapping the world whereas the former aims to emancipate and thus to transform it (Horkheimer, 2002 [1937]: 197, 208 f., 217, 219). In other words, critical theory has an explicit knowledge-interest that sets it apart from traditional theory which cannot even admit of having a knowledge-interest. According to Horkheimer, traditional theory thus does not only differ in its knowledge-interest but ideologically misconceives its own activity and the knowledge it produces (Horkheimer, 2002 [1937]: 221–4, especially 222).

Second, critical theory conceptualises the historicity of its knowledge differently than traditional theory does. Instead of accepting the received view of a timeless truth to be uncovered by bourgeois science, critical theory recognises that its own knowledge has a ‘temporal core’ (Horkheimer and Adorno, 2002 [1947]: xi). Although Horkheimer admits that this leads into difficulties he remains adamant that critical theory is ‘opposing the idea of an absolute, suprahistorical subject or the possibility of exchanging subjects, as though a person could remove himself from his present historical juncture and truly insert himself into any other he wished’ (Horkheimer, 2002 [1937]: 240).

Both differences concern the specific kind of knowledge produced by a critical or traditional theory – critique is again, as in Foucault’s model of critique, specified as first and foremost a knowledge-producing practice. Yet the affinity goes beyond this general commonality, for both differences between critical and traditional theory are present in the distinction between ‘biopolitics’ as a critical and as a descriptive concept. First, using ‘biopolitics’ descriptively would indeed revert to a mere mapping of a particularly interesting aspect of our present, yet would not amount to a critique – unless the analysis is either supplanted with new counter-truths or is transplanted into another model of critique. Turning the diagnosis ‘biopolitics’ into the object of critique without providing new unwieldy knowledge transforms the theoretical activity of Foucault’s diagnostic practice of critique into an analysis that either must seek another account for its critical force (e.g. by becoming a form of immanent critique) or that ceases to be critical altogether.

The second difference between critical and traditional theory is mirrored by the two usages of ‘biopolitics’ as well and accounts for the fact that Foucault’s critique is not easily repeatable because the counter-truths produced by Foucault’s diagnostic practice are tied to the very specific present the critique analyses and to this present’s limits of what is or is not ‘in the truth’. Thus, repeating Foucault’s critique of sexuality by using ‘biopolitics’ in its critical function today cannot fail to disappoint. For even if we could suppose that the present dispositif of sexuality has remained relatively unchanged, the critical discourse on sexuality has not. Yet if the analysis of a ‘repressed sexuality’ no longer frames that discourse, a diagnosis to the contrary no longer constitutes counter-truths: statements bordering on the limit of our truth-regime that oppose that very truth-regime on the level of depth-knowledge. In this sense, Foucault’s critique has a ‘temporal core’ and, like Horkheimer’s critical theory, cannot think of itself as timeless truth.

As with the first affinity between Adorno’s and Foucault’s model of critique, the correspondence between Horkheimer’s and Foucault’s distinctions concerns the knowledge critique produces. In fact, the distinction between critical and traditional theory relies on the methodological perspective outlined with the first affinity; taken together they constitute a similar ‘stature’ of critique even though the inner details remain different. Yet it demonstrates an affinity between Foucault and Horkheimer and Adorno that is misinterpreted if we either presuppose the Habermasian reconstruction of the early Frankfurt School or a less systematic account of Foucault’s methodological perspective (cf. McCarthy, 1990).

Biopolitics and Critique

My methodological re-reading of Le Volonté de Savoir started from the relationship between ‘biopolitics’ as it appears in Foucault’s published work, his model of critique in which the concept is used and the methodological affinities to Adorno’s model of critique. These seemingly simple exegetical issues allowed identifying the changed role of ‘biopolitics’ within the diagnostic critique aimed at prefigurative emancipation and its affinity to Horkheimer’s distinction between critical and traditional theory. This in turn leads to three implications for using ‘biopolitics’ as a concept within critical theory more broadly.

First, saying that ‘biopolitics’ takes on a descriptive role in an ‘analytics of biopolitics’ as outlined, for example, by Lemke does not accuse this analytic of being an uncritical enterprise. Yet it does mean that ‘biopolitics’ as a concept cannot afford the analysis any critical force by itself. If ‘biopolitics’ assumes the conceptual place of the object under study (the ‘experience’ in Foucault’s terminology), and if the ‘analytics of biopolitics’ still intends to use Foucault’s model of critique, then its critical diagnosis must forge a new set of counter-truths in order to challenge ‘apparently natural or self-evident modes of practice and thought – inviting us to live differently’ (Lemke, 2010: 434).

This emphasises, second, how demanding Foucault’s model of critique is and what a peculiar relationship to truth it has. If critique succeeds in changing our relation to what we know on the level of depth-knowledge, emancipating us from certain truths by revealing how their conditions of existence are forged in and through social struggles, a repetition of that critique cannot have the same emancipatory effect. Hence Foucault’s model of critique is not just conceptually demanding because it is committed to philosophically wide-ranging and contentious claims but also because its counter-truths have a ‘temporal core’: Foucault’s model of critique requires a ‘philosophical ethos that could be described as a permanent critique of our historical era’ (Foucault, 1997a [1984]: 312) – yet it also requires this permanent critique not to repeat itself, for once we have come to accept the counter-truths it offers, these cease to function as counter-truth. Toying with the current conditions of existence for statements to be able to have a truth-value, these counter-truths lose their ability to prefiguratively emancipate us once they are included within our discourses. If critique is to stay at the limits of what we can think, do and be, it has to acknowledge and transform with its own effects on these limits.

The same holds for Adorno’s model of critique and Horkheimer’s defence of a critical theory different from traditional theory. The two affinities outlined suggest that in each case, conceptualising critique as a diagnostic practice producing an effective, unwieldy knowledge is the reason for the high demands placed on critique. One such demand is a philosophical account of truth’s historicity without relativising truth – a task that shows where Foucault and Adorno and Horkheimer clearly part ways.25

Third, and more concrete, this leads to the much broader question whether an ‘analytics of biopolitics’ should develop another model of critique. Maybe we could understand the different ways in which Agamben, Hardt and Negri or Esposito have developed the notion of biopolitics precisely as re-deploying it within very different conceptions of critique:26 within a dystopian critique of sovereignty’s hidden structure that makes ‘biopolitics’ the target of critique, within a post-Marxist critique of Empire’s absorption of the life-forces of the multitude that sees ‘biopolitics’ as a resource for critique or within a constructive critique of the paradigm of immunisation that emphasises ‘biopolitics’ ambivalent relation to critique.27 Yet precisely at this juncture, when critical theory develops new and exciting relationships between ‘biopolitics’ and critique, we might come to appreciate the common ‘stature’ of Foucault’s and Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s critique with its focus on the knowledge critique produces: for how do these re-deployments of ‘biopolitics’ account for the wrongness of what they criticise? What truths do we affirm when we base our critique on an opposition between ‘life’ within and without the reach of ‘politics’ – for example a life with the inherent capability to escape biopolitics (Mills, 2015: 97 f.)? Having learned our lesson about sexuality, we should not disregard its implications with respect to ‘life’: what power mechanisms shaped the depth-knowledge enabling us to think and speak of life beyond politics? What counter-truths could we come up with to forge an understanding of life that does not implicate our critique in those power relations? Thinking through this question would offer us, I think, a further glimpse of prefigurative enlightenment.

Notes

1. Thanks go to Daniel Loick for his constructive criticism of an early draft.

2. The conceptual history of ‘biopolitics’ is of course older than its usage in critical theory: see Esposito (2008 [2004]: 16–24).

3. Since my reading emphasises the role of depth-knowledge [savoir], I prefer the French book title which is also more informative than the English translation History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction.

4. In The Birth of Biopolitics (Foucault, 2008 [2004]) hardly ever mentions ‘biopolitics’, being instead an analysis of liberalism as a political rationality – because, Foucault argues, ‘the analysis of biopolitics can only get under way when we have understood the general regime of this governmental reason’ (ibid.: 21 f.).

5. Lemke (2011 [2007]), Campbell (2013), and Folkers and Lemke (2014) provide good overviews from different perspectives.

6. See Vogelmann (2017b) for more details.

7. ‘Experience’ here means not a subjective episode but the ‘correlation of a domain of knowledge [savoir], a type of normativity, and a mode of relation to the self’ (Foucault, 1997b [1984]: 199 f.).

8. I take the term ‘depth knowledge’ from Hacking (2002 [1981]: 77).

9. Foucault’s insistence on this difference between conditions of existence and conditions of possibility is most pronounced in Foucault (2010 [1969]: e.g. 116) where he repeatedly distinguishes conditions of possibility as ‘principles of construction’ from conditions of existence. See Gutting (1989: 242).

10. Although Foucault uses the notion of a ‘truth-regime’ from time to time, he does not develop it conceptually (Weir, 2008: 370–4). I use it as a shorthand for ‘conditions of existence for statements to be candidates for truth-values’. For a more general discussion, see Nigro (2015).

11. On prefiguration and prolepsis, see Wright (1993: 46, fn. 12), Maeckelbergh (2011: 3).

12. Martin Saar’s ‘genealogical blueprint’ captures well what desubjectivation means: ‘Tell me the story of the genesis and development of my self-understanding using the notion of power (or related notions, such as strategy, or interest, subjection, submission, exploitation, etc.) in such a way that hearing you talk, I don’t want to be as I thought I have to be, and that, hearing you talk, I realize that this isn’t necessary’ (Saar, 2002: 236 f.).

13. In Security, Territory, Population, Foucault claims that his work embodies only the following conditional imperative: ‘If you want to struggle, here are some key points, here are some lines of force, here are some constrictions and blockages’ (Foucault, 2007 [2004]: 18).

14. In this respect my remarks are close to Thomas McCarthy’s six ‘broad affinities’ (McCarthy, 1990: 437–41). Yet his interpretation of Foucault and of the Frankfurt School Critical Theory relies mostly on Habermas’ conceptions of both, which prevents further dialogue. McCarthy acknowledges that to some extent: see ibid.: 464, fn. 1.

15. When Adorno characterises his understanding of philosophy, philosophy and critique are identical. Just one example: ‘If philosophy is still necessary, it is so only in the way it has been from time immemorial: as critique […]’ (Adorno, 2005 [1962]: 10).

16. For a thoughtful and detailed explanation of Adorno’s interpretative method of critique and its connection to epistemological questions, see Christ (2012).

17. Looking back, Foucault writes in The Use of Pleasure: ‘What I planned, therefore, was a history of the experience of sexuality, where experience is understood as the correlation between fields of knowledge, types of normativity, and forms of subjectivity in a particular culture’ (Foucault, 1990 [1984]: 4).

18. ‘Dispositif’ is rendered incoherently as ‘deployment’, ‘layout’, ‘organisation’ and the like by the English translation – ‘unhelpful’ (Elden, 2016: 53) indeed.

19. For a nuanced critique from a post-colonial perspective on Foucault’s Eurocentric genealogy of biopolitics, see Stoler (2004 [1995]).

20. Hence, the ‘massacres have become vital’ (HS1: 137): they can be committed only in the ‘name of life’ (ibid.). Foucault developed this functional analysis of state racism first in his lecture course Society Must Be Defended (Foucault, 2003 [1997]: 254–63). For critique and development of this controversial analysis, see e.g. Stoler (2004 [1995]), Balibar (1995 [1989]: 40–2), Lemke (1997: 224–38).

21. ‘For the first time in history, no doubt, biological existence was reflected in political existence; the fact of living was no longer an inaccessible substrate that only emerged from time to time, amid the randomness of death and its fatality; part of it passed into knowledge’s field of control and power’s sphere of intervention’ (HS1: 142).

22. I use my own translation of Foucault’s original sentence ‘Ironie de ce dispositif: il nous fait croire qu’il y va de notre “libération”’ (Foucault, 2001 [1976]: 211) since the English translation is ‘free’ to the point of distortion.

23. Judith Butler famously criticises Foucault’s use of the term ‘pleasures’ because it would contradict Foucault’s critique of sexuality as power-ridden dispositif to posit ‘a “multiplicity of pleasures” in itself which is not the effect of any specific discourse/power exchange’ (Butler, 1990: 97). Yet Foucault does not assume pleasures free from any power/knowledge-regime but pleasures of a different regime (a ‘different economy of bodies and pleasures’) than the regime of ‘sexuality’. See Repo (2014).

24. Lemke (2011 [2007]: 44–50), Oksala (2013: 61–3), Gros (2015: 259) advances similar claims.

25. For Foucault, see Vogelmann (2014), on Horkheimer’s and Adorno’s account of truth’s historicity, see Shomali (2010: chapter 2).

26. I thank Valentin Jandt for discussions on this point. In his brilliant BA-Thesis Politics – Life – Critique (University of Bremen, 2015, on file with the author), he explores the critical function of the concepts of biopolitics in the works of Foucault, Agamben, and Hardt and Negri.

27. There are of course many more developments that reshape the relationship between ‘biopolitics’ and ‘critique’. To mention only a few: Achille Mbembe’s concept ‘necropolitics’ (Mbembe, 2003) as well as Banu Bargu’s ‘biosovereignty’ (Bargu, 2014: 43–54) build on Agamben’s re-interpretation of ‘biopolitics’, focussing on its ‘thanatopolitical’ side and making it the target of critique. Others explore biopolitics as a source of critical agency or resistance: see e.g. Beatriz Preciado’s (2013 [2008]: 352) call for reclaiming ‘the right to participate in the construction of biopolitical fictions’ or Mike Laufenberg’s (2014) ‘politics of care’ that turns the care about life against its current political occupation.

References

(1977 [1973]): The Actuality of Philosophy. In: Telos 31, 120–33.

(2005 [1962]): Why Still Philosophy? In: Critical Models. Interventions and Catchwords. New York: Columbia University Press, 5–17.

(2005 [1969]): Resignation. In: Critical Models. Interventions and Catchwords. New York: Columbia University Press, 289–93.

(1998 [1995]): Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

(2016): The End of Progress. Decolonizing the Normative Foundations of Critical Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

(1995 [1989]): Foucault and Marx. The Question of Nominalism. In: Michel Foucault, Philosopher. Ed. by Timothy J. Armstrong. New York: Routledge, 38–57.

(2014): Starve and Immolate. The Politics of Human Weapons. New Directions in Critical Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

(1990): Gender Trouble. Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

(2004 [2001]): What Is Critique? An Essay on Foucault’s Virtue. In: The Judith Butler Reader. Ed. by Sara Salih and Judith Butler. Malden MA: Blackwell, 301–21.

(2013): Biopolitics. An Encounter. In: Biopolitics. A Reader. Ed. by Timothy C. Campbell and Adam Sitze. Durham: Duke University Press, 1–40.

(2012): Un jeu avec le réel – esquisse de la méthode critique d’Adorno. In: Philosophie 113, 37–57.

(2013): Adorno, Foucault and Critique. In: Philosophy & Social Criticism 39(10), 965–81.

(2016): Foucault’s Last Decade. Cambridge: Polity Press.

(2008 [2004]): Bíos. Biopolitics and Philosophy. Translated by Timothy Campbell. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

(2010): Coming Back to Life. An Anthropological Reassessment of Biopolitics and Governmentality. In: Governmentality. Current Issues and Future Challenges. Ed. by Ulrich Bröckling, Susanne Krasmann and Thomas Lemke. New York: Routledge, 185–200.

and (2014): Einleitung. In: Biopolitik. Ein Reader. Ed. by Andreas Folkers and Thomas Lemke. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 7–61.

(1977 [1975]): Discipline and Punish. The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books.

(1978 [1976]): The History of Sexuality. Volume I: An Introduction. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books.

(1980 [1975]): Body/Power. In: Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. Ed. by Colin Gordon. New York: Pantheon Books, 55–62.

(1990 [1984]): The Use of Pleasure. Volume 2 of the History of Sexuality. Translated by Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage Books.

(1997 [1978]): What Is Critique? In: The Politics of Truth. Ed. by Sylvère Lotringer and Lysa Hochroth. New York: Semiotext(e), 23–82.

(1997a [1984]): What is Enlightenment? In: Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Vol. I. Ed. by Paul Rabinow. London: Penguin, 303–19.

(1997b [1984]): Preface to The History of Sexuality, Volume Two. In: Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume I. Ed. by Paul Rabinow. London: Penguin, 199–205.

(1998 [1978]): Questions of Method. In: Power. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume III. Ed. by J. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 223–38.

(1998 [1980]): Interview with Michel Foucault. In: Power. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume III. Ed. by J. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 239–97.

(1998 [1982]): The Subject and Power. In: Power. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume III. Ed. by J. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 326–48.

(1998 [1983]): Structuralism and Post-Structuralism. In: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume II. Ed. by J. Faubion. New York: The New Press, 433–58.

(1998 [1984]): The Ethics of the Concern for the Self as a Practice of Freedom. In: Ethics, Subjectivity and Truth. Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954–1984, Volume I. Ed. by Paul Rabinow. New York: The New Press, 281–301.

(2001 [1976]): La Volonté de Savoir. Histoire de la Sexualité I. Paris: Gallimard.

(2001 [1981]): Les mailles du pouvoir (n°297) In: Dits et Écrits II. 1976–1988. Ed. by Daniel Defert, François Ewald and Jaques Lagrange. Paris: Gallimard, 1001–1020.

(2002 [1977]): Preface to the Italian edition of La Volonté de Savoir. In: Pli 13, 11–12.

(2003 [1997]): Society Must Be Defended. Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–1976. Translated by David Macey. New York: Picador.

(2007 [2004]): Security, Territory, Population. Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978. Translated by Graham Burchell. Ed. by Michel Senellart. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(2008 [2004]): The Birth of Biopolitics. Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979. Translated by Graham Burchell. Ed. by Michel Senellart. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(2010 [1969]): The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Translated by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books.

(2010 [2008]): The Government of Self and Others. Lectures at the Collège de France 1982–1983. Translated by Graham Burchell. Ed. by Frédéric Gros. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(2014 [2011]): Lectures on the Will to Know. Lectures at the Collège de France 1970–1971 and Oedipal Knowledge. Translated by Graham Burchell. Ed. by Daniel Defert. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(2013): Adorno’s Practical Philosophy. Living Less Wrongly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(2002): Genealogy as Critique. In: European Journal of Philosophy 10(2), 209–215.

(2015): Is There a Biopolitical Subject? Foucault and the Birth of Biopolitics. In: Biopower. Foucault and Beyond. Ed. by Vernon W. Cisney and Nicolae Morar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 259–73.

(1989): Michel Foucault’s Archaeology of Scientific Reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

(2002 [1981]): The Archaeology of Michel Foucault. In: Historical Ontology. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press, 73–86.

and (2000): Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

(1986): Foucault and Adorno. Two Forms of the Critique of Modernity. In: Thesis Eleven 15(1), 48–59.

(2002 [1937]): Traditional and Critical Theory. In: Critical Theory. Selected Essays. New York: The Continuum Publishing Company, 188–252.

and (2002 [1947]): Dialectic of Enlightenment. Philosophical Fragments. Translated by Edmund Jephcott. Ed. by Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

(2013): Genealogy as Critique. Foucault and the Problems of Modernity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

(2014): Sexualität und Biomacht. Vom Sicherheitsdispositiv zur Politik der Sorge. Bielefeld: transcript.

(1997): Eine Kritik der politischen Vernunft. Foucaults Analyse der modernen Gouvernementalität. Berlin: Argument Verlag.

(2010): From State Biology to the Government of Life. Historical Dimensions and Contemporary Perspectives of ‘Biopolitics’. In: Journal of Classical Sociology 10(4), 421–38.

(2011 [2007]): Biopolitics. An Advanced Introduction. Translated by Eric Frederick Trump. New York: New York University Press.

(2012): Foucault, Governmentality, and Critique. Boulder/London: Paradigm Publishers.

(2011): Doing is Believing. Prefiguration as Strategic Practice in the Alterglobalization Movement. In: Social Movement Studies 10(1), 1–20.

(1998 [1956]): Eros and Civilization. A Philosophical Inquiry into Freud. London: Routledge.

(2003): Necropolitics. In: Public Culture 15(1), 11–40.

(1990): The Critique of Impure Reason. Foucault and the Frankfurt School. In: Political Theory. An International Journal of Political Philosophy 18(3), 437–69.

(2015): Biopolitics and the Concept of Life. In: Biopower. Foucault and Beyond. Ed. by Vernon W. Cisney and Nicolae Morar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 82–101.

(2008): Eine Genealogie der Biopolitik. Zum Begriff des Lebens bei Foucault und Canguilhem. Bielefeld: transcript.

(2015): Wahrheitsregime. Zürich/Berlin: Diaphanes.

(2013): Neoliberalism and Biopolitical Governmentality. In: Foucault, Biopolitics, and Governmentality. Ed. by Jakob Nilsson and Sven-Olov Wallenstein. Huddinge: Södertörn University, 53–71.

(2015): Power and Biopower in Foucault. In: Biopower. Foucault and Beyond. Ed. by Vernon W. Cisney and Nicolae Morar. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 102–117.

(2013 [2008]): Testo Junkie. Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Translated by Bruce Benderson. New York: The Feminist Press.

and (2015 [2006]): Biopower Today. In: Biopower. Foucault and Beyond. Ed. by Vernon W. Cisney and Nicolae Morar. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 297–325.

(2014): Herculine Barbin and the Omission of Biopolitics from Judith Butler’s Gender Genealogy. In: Feminist Theory 15(1), 73–88.

(2007): The Politics of Life Itself. Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-first Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

(2002): Genealogy and Subjectivity. In: European Journal of Philosophy 10(2), 231–45.

(2008): Understanding Genealogy. History, Power, and the Self. In: Journal of the Philosophy of History 2(3), 295–314.

(2010): Politics and the Criteria of Truth. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

(2004 [1995]): Race and the Education of Desire. Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

(2012): Neosocial Market Economy. In: Foucault Studies 14, 115–37.

(2014): Kraft, Widerständigkeit, Historizität. Überlegungen zu einer Genealogie der Wahrheit. In: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie 62(6), 1062–86.

(2017a): The Spell of Responsibility. Labor, Criminality, Philosophy. Translated by Daniel Steuer. London: Rowman & Littlefield International.

(2017b): Critique as a Practice of Prefigurative Emancipation. In: Distinktion 18(2), 196–214.

(2008): The Concept of Truth Regime. In: The Canadian Journal of Sociology 33(2), 367–89.

(1993): Explanation and Emancipation in Marxism and Feminism. In: Sociological Theory 11(1), 39–54.