CHINA’S RISE: GETTING ITS HOUSE IN ORDER

China’s rise and economic transformation have been driven by favourable demographics, a high saving rate, and impressive industrial investment by both Chinese and foreigners as the country opened up to the world. But China’s progress has not been without its problems and related challenges of managing the tensions of a politicized market place and growing statism under President Xi Jinping.

Even as China becomes more of a global force, its leaders are preoccupied with “getting its house in order” with reforms that address risks while serving the Party’s primary goal of political stability. Three priorities stand out: maintaining economic growth at sustainable rates, dealing with the systemic risks posed by an immature financial system as China becomes a global player, and addressing the persistent low productivity of state-owned enterprises. The existing development model encouraged massive rural-urban migration, raised incomes, and supported the emergence of a burgeoning middle class, but these have come at a heavy cost. The polluted environment endangers people’s health; incomes and wealth are unequally distributed;1 the some 150,000 SOEs have supported industrial growth rates by borrowing to finance their activities and running up large debts that outstrip their ability to repay.

As the Party responds to the contradiction between pursuing “growth at any cost” and popular demands for a better quality of life, economic growth must also satisfy the implicit social contract between the people and the Party whereby the people tolerate the Party’s autocratic ways in exchange for steady improvements in jobs and living standards. It is to these ends that China is restructuring and rebalancing its low-cost, labour-intensive, export-oriented industrial base to one that is more services-based, consumer-oriented, and productivity driven – and sustainable. Improving productivity performance will support slower but more sustainable growth; at the officially anticipated annual real rate of around 6 per cent, the economy would double in size every twelve years.

The reform agenda, however, is highly politicized. To restore a power base free of corruption, the Party is seeking changes affecting all major interest groups within government, the military, and the economy. To counterbalance the resulting political pressures, Xi has centralized administrative power.2 The anti-corruption campaign is part of this evolving structure, as are a National Security Council and small leading groups that oversee various policy areas and report directly to Xi. The anti-corruption campaign is popular because of its focus on reducing the misuse of political privilege that had become widespread among Party members and elites. In March 2018 a National Supervisory Commission was inaugurated with the mandate to broaden the anti-corruption campaign beyond the Party to “all public posts.”3

No one expects China to be problem-free with these changes. At the National People’s Congress in March 2018, Xi focused on three “tough battles” in the real economy: addressing financial risks, reducing poverty, and tackling pollution. The poverty-reduction battle emphasizes poverty relief, improved market access for production from poorer regions, and access to better education and health services.4 Modernizing the financial system and developing a greener and cleaner economy are part of rebalancing the economy to rely more on services sectors and on innovation and productivity performance to drive growth.

At the same time, Xi is pursuing his dream of a major rejuvenation to restore China’s greatness in the world. Global benchmarks are apparent in vows of Chinese leadership in global forums and in initiatives to become a world military power and technology leader and to expand China’s global influence through infrastructure investments and connectivity. China is engaged in potentially game-changing initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative, which are ambitious and risky and not yet well understood in Western countries, where there is a tendency to focus on and magnify the risks of failure.

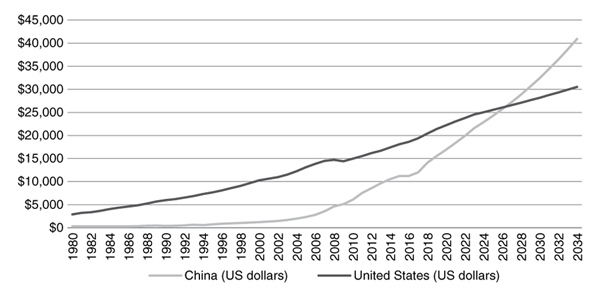

These aspirations and the prospect of China’s eclipsing the United States as the world’s largest economy by 2030 or sooner (Figure 1.1) have strengthened expectations of a global shift in economic and political power. Different measures of GDP give differing crossover points. In Figure 1.1, the measure is US dollar GDP measured in current dollars, and the crossover point is estimated to be 2027, according to the International Monetary Fund. Another commonly used measure is purchasing power parity (PPP), which takes into account the cost of living in respective countries. Since Chinese prices are lower than US prices, a given dollar amount of income goes much further than in the United States. By PPP measures, China’s GDP eclipsed that of the United States in 2014.

Figure 1.1 Trajectory of Growth of Gross Domestic Product, China and the United States, 1980–2034

The outcome of the 2016 US presidential election unexpectedly added to this narrative, as the new president projected a view of each nation on its own, rather than continuing to cooperate in the post-war US-led world order. Preoccupations with “America First” and “making America great again” marked a significant shift towards zero-sum policy thinking. Together with an erratic, transactional approach to international relations, a vacuum in global leadership has opened, one that China could move to fill.

Indeed Xi Jinping aspires to shape reforms in global governance, as he made clear in a June 2018 speech, when he predicted that, by 2050, China will have become “a leader of composite national strength and international influence.” Xi also called for China to “lead the reform of the global governance system with the concepts of fairness and justice,” signalling what former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd predicted is likely to be a wave of Chinese international policy activism.5

Xi has elaborated this theme in a series of high-profile international events since 2014. That year, China chaired the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit, at which negotiating a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific was proposed. In 2015 China and the United States also worked out a joint leadership initiative on climate change at talks leading to the Paris Agreement on Climate Change. In 2015 as well, as part of the BRI, China launched the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a new multilateral institution to help fund major infrastructure and connectivity investments in the region and beyond. In 2016 China hosted the annual meeting of G20 leaders in Hangzhou, where the central theme was “building an innovative, invigorated, interconnected and inclusive world economy.” In January 2017 Xi’s keynote speech to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, further committed China to building a moderately prosperous future with a community of shared destinies for humanity and win-win cooperation. In April 2017 Xi’s first official meeting with the new US president, Donald Trump, set an initial positive tone at the top in the bilateral relationship. In his April 2018 keynote speech to the Boao Forum for Asia, entitled “Openness for Greater Prosperity, Innovation for a Better Future,” Xi committed to strengthened protection of IP rights and to opening up more of the Chinese economy by liberalizing trade and investment – reforms very much in line with political priorities for the bilateral relationship.6 In a 2019 visit to Rome, Xi welcomed Italy’s endorsement of the BRI, the first such commitment by a G7 government, and at the second Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in April 2019 he elaborated further on these themes.

This is a remarkable series of positive messages about how Chinese interests include commitments to the world’s collective future, but Chinese and Americans interpret them very differently. China realizes it is a big beneficiary of globalization. China’s economic growth – and access to foreign investment, trade, and ideas – has been spectacularly successful in pulling people out of poverty. In contrast the United States is struggling with the political fallout from an economy in which significant groups have fallen behind, immigration and foreigners are blamed, and public support for globalization is undermined.

The current US administration has expressed its views of China in its National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy, both released in December 2017. These documents stereotype China as a revisionist power seeking regional hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region and projecting its power in Cold War fashion. Some experienced diplomats and analysts have discounted this approach as simplistic and lacking in understanding of Chinese motivations, while missing China’s actual challenge. China, they argue, is seeking neither military conflict nor to overthrow the existing system. As Paul Heer, a former national intelligence officer, maintains, the true challenge is that China is competing with the United States on its own terms, challenging the US conception of its exclusive role in the world and pursuing the dream to re-establish China’s status as a great power (but not global pre-eminence).7 China is not intimidated by any attempted US trade war, but instead is engaging in tit-for-tat. None of this, it is argued, implies a zero-sum calculus by China; instead, as Xi’s speeches make clear, China acknowledges interdependence. The United States should, too, because it will have to find ways to accommodate Chinese aspirations and ambitions.

Others disagree. Course Correction, a 2019 report by the Asia Society’s Task Force on US-China Policy, sees the two countries on a collision course as the foundations of good will built up over many years erode. Many Americans see China’s rise under Xi Jinping as unfairly undercutting US prosperity and security, while Chinese increasingly view the United States as a declining power. This essential relationship, the report insists, must be prevented “from running off the rails.”8

Understanding the changing dynamics of China’s relationship with the United States is essential to Canada’s learning to live with China. I return to these dynamics in later chapters; here, I focus on China’s domestic economic objectives and the tensions between market forces and state intervention – both the focus of much US criticism – which complicate the rebalancing and restructuring of the Chinese economy necessary to grow at a sustainable rate. These tensions are recognized in the 13th Five-Year Plan (2016–20), and were extensively discussed in 2013 at the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress. At that meeting, Xi stated “the focus of the restructuring of the economic system ... is to allow the market [forces] to play a ‘decisive role’ in the allocation of resources.”9 These words were a call for government to withdraw from its long-established practice of pricing and allocating key production inputs such as land, capital, and energy, and instead allow the operation of market forces in deregulated and competitive product markets. Instead, in 2015–16, high-level political support for market reforms evaporated as the government scrambled to address the multiple challenges of the stock market meltdown, large capital outflows, and exchange-rate depreciation. In 2017 the state increased its role in domestic enterprises as Party members participated in decision making in both SOEs and private firms. Party cells reportedly were to be established in foreign-invested joint ventures as well.10

Fighting corruption, revamping the military, and national security ranked higher in Party priorities than did economic reform and modernization until 2016–17, when President Xi labelled financial risks a “threat to national security” requiring regulatory and other reforms (see Chapter 3). To avoid unwanted currency depreciation, cross-border capital flows had to be curbed, despite their importance to the open economy and the internationalization of the renminbi. To support growth objectives, banks were encouraged to finance growth-supportive corporate investments while managing them in ways that would avoid rising debt defaults in a slower-growing economy. Opening the market to foreign competition also had to be managed carefully to reduce competitive pressures on SOEs. Financed by borrowing at subsidized rates from state-owned banks, SOEs were chosen to support short-term growth objectives. With private sector indebtedness reaching levels as high as 170 per cent of GDP, however, the OECD and IMF warned of default risks and bank runs associated with a hard landing. This resulted in mixed signals, suggesting that the authorities were operating with one foot on the accelerator to meet growth targets and one foot on the brake to avoid politically risky side effects.

This tension between state and market suggests that, to the Chinese authorities, “sustainable growth” is participative and redistributive. The 13th Five-Year Plan addresses both goals. It calls for accelerated financial reform, opening financial markets, and improving competition in “national monopoly sectors,” while including resources for social welfare proposals to combat poverty, improve the social insurance system, adjust pension funds, reform public hospitals, and provide health insurance for the jobless.

Following the 19th Party Congress in late 2017 and the National People’s Congress in March 2018, a new team, including Xi’s allies, took charge of the Politburo Standing Committee. For this seven-person Party leadership group, tackling corruption remained a political priority that outranked the importance of economic modernization and reform – despite a strong case for the growth-augmenting potential of increasing the efficiency of SOEs and other enterprise reforms.

One notable exception to this agenda was the priority given the goal of a low-carbon future. The 13th Five-Year Plan includes a number of “green” proposals that focus on low-carbon industry systems, “green” finance, new-energy vehicles, forest protection, and an online environmental monitoring system. Since the 1970s, China’s heavy reliance on coal to fuel the industrial economy has been a major source of carbon emissions. Pledges since 2009 to cut carbon intensity have been expanded to cap carbon emissions and increase the sources of non-fossil fuels to 20 per cent of energy requirements by 2030, with greenhouse gas emissions expected to peak between 2025 and 2030. Measures have already been taken to limit energy consumption and to cut energy and carbon intensity. The pragmatic introduction of market-based approaches would augment these administrative measures. At the end of 2017, a carbon-trading system was announced that covers power-generation plants, and an exchange for trading emissions permits has been given the go-ahead. What is missing is a market-determined carbon price.11

These actions – and inactions – speak louder than words. Additional rebalancing is required, but this is constrained by conflicting political and economic objectives. Achieving the objectives of sustainable growth, a modern financial system, and more competitive SOEs would require structural changes that, in turn, depend on a political decision to take the foot off the brake and allow the accelerator (market forces) to work.

ACHIEVING SUSTAINABLE GROWTH: AVOIDING THE “MIDDLE-INCOME TRAP”

Major structural reforms are required to the supply side of the Chinese economy to raise productivity and encourage innovations and technologies that use capital and labour more efficiently. Such a supply-side transition will not be not easy, however, and the risks to growth are real. In 2008 the World Bank’s Growth Commission found that, in the post-war period, only thirteen developing countries experienced annual growth rates of at least 7 per cent for twenty-five years or longer. These countries shared certain common characteristics that included economic openness, macroeconomic stability, committed and capable government, high rates of savings and investment, and reliance on market forces to allocate resources.12 Studies of the reasons a country’s economic growth slows or stagnates have identified a variety of factors. Commonly, as abundant labour supplies are used up and wages rise, exports become uncompetitive and growth in incomes slows unless new sources of growth are tapped, most importantly by encouraging technological development to improve productivity performance. The alternative is to risk being squeezed between low-wage competitors in mature industries and innovators in industries undergoing rapid technological change, and suffering slowing growth as a consequence. In addressing the risks of falling into this “middle-income trap” of slow or stagnant growth, each country has to find its own solution. South Korea is a well-known success story, where government stepped back from its roles as owner and intervenor in the economy and instead set the framework for the private sector and introduced supporting policies to promote more advanced education and modern finance, among other goals.

China’s leaders are concerned about these risks, and since 2015 have sought to sustain growth by improving manufacturing and industrial productivity. They have set ambitious technological goals for the Made in China 2025 strategic plan. As I discuss in Chapter 2, this strategic initiative is controversial, not least because of its generous government financial support, its official emphasis on producing in China goods previously sourced abroad, and its policy discrimination favouring Chinese over foreign firms.

The contrast between these political choices and what economic theory prescribes to escape the middle-income trap can be seen in the work of Peking University professor Huang Yiping.13 Applying lessons the World Bank’s Growth Commission learned from countries that avoided the trap, Huang recommends strengthening China’s research and education base, providing more education for the country’s 300 million migrant workers, and further liberalization and modernization of the financial system to support the risk- taking necessary to finance technological innovation and industrial upgrading. Among the key lessons to be learned from other countries, Huang notes the importance of legal and political policies to liberalize entry to protected sectors dominated by state enterprises, and the protection of property rights in order to encourage risk- taking and innovation.

FINANCIAL MODERNIZATION AND REBALANCING

Financial system reform and modernization are integral both to achieve China’s economic rebalancing objectives and to avoid the middle-income trap. SOEs figure prominently in these reforms because of their close institutional linkages with state-owned banks, which view them as low-risk, government-connected borrowers. Until recently, debt rollovers and debt-equity conversions were favoured over defaults. As the Bank for International Settlements has estimated, however, non-financial companies account for two-thirds of China’s total official debt level – one of the world’s highest, exceeding 260 per cent of GDP – with SOEs accounting for one of the most serious debt problems.14

At the July 2017 meeting of the National Financial Work Conference, Xi Jinping identified financial risks as a national security threat, and in his opening speech to the 19th Party Congress later in the year he stressed SOE indebtedness as a priority. He also underscored the need for deleveraging, which would require a shift away from the quantitative growth targets that drove borrowing in the first place. To that end, moves to strengthen the powers of China’s financial regulators and improve coordination among them were a key policy outcome of the National Financial Work Conference.15 In 2018 the IMF, in its Article IV consultation report, welcomed China’s formation of a Financial Stability and Development Committee, chaired by Vice-Premier Liu He.16 The IMF emphasized the importance of assessing the evolution of systemic risks in particular, and recommended that China strengthen its regulatory and macroprudential policy framework.17

The overall performance of China’s financial institutions is strongly influenced by that of four large state-owned commercial banks that dominate China’s financial sector and its role in supporting the real economy. The negative consequences of shadow banking activities and the ready supply of credit to connected state-owned borrowers are well known. These practices have troubled the IMF, which, after warning against them in 2016, subsequently supported measures to rein in the interbank borrowing, proliferating wealth-management products, and off-balance-sheet activities that were riskier parts of the immature financial system. Notably, the outcomes included a smaller shadow banking sector and reduced connections between banks and non-banks.18 Following the March 2019 National People’s Congress, People’s Bank of China governor Yi Gang signalled further reforms to improve investors’ risk management by freeing up prices in capital markets and expanding the supply of hedging tools.

One increasingly dynamic feature of China’s financial sector is Internet finance, which includes deposits, loans, investments, insurance, equity crowdfunding, and Internet fund sales, and is creating alternative financial instruments and channels for consumers, savers and investors. Online consumer financial services to savers and lenders has proliferated rapidly in this environment. Initial official supervision of these Internet activities was light, as regulators practised forbearance and watched and learned as the industry evolved. But fraudulent operators took advantage of the regulatory vacuum, creating new risks that led to a crackdown by the central bank and financial regulators in 2016–17. The bank led multiple agencies in designing a cleanup plan and a crackdown on fraudulent online payments, peer-to-peer (P2P) lending, equity crowdfunding, wealth management, and online insurance. Agencies in the provinces that register corporations were instructed to reject any new registrations of companies with “finance” in their names or business descriptions.19 The State Council set up a task force involving ten agencies to better regulate Internet finance and introduce measures to reduce risk, improve the competitive environment, and boost risk awareness of investors.20 In May 2017 the People’s Bank of China replaced its technology department with an oversight committee “to oversee financial technology” in light of the speedy growth of the industry and in recognition of cross-sector financial risks.21 Subsequently, in July 2018, the central bank opened a third-party payment platform called Nets Union Clearing Corporation, which subjects all financial transactions of third-party-payment firms such as Alipay and TenPay to regulatory oversight. By the end of that year, the combined negative growth effects of uncertainties generated by the US-China trade dispute and the regulatory crackdown on shadow banks were evident as market forces were allowed to set prices. The benchmark Chinese Securities Index 300 ended the year down more than 25 per cent over the previous year, compared with an 8 per cent decline in the S&P 500 index. New daily mark-to-market requirements played a significant role by eliminating the perception that such prices were guaranteed.22

These financial reforms are key features of China’s larger quest for financial modernization and rebalancing. But the timing and somewhat ad hoc implementation of regulatory reforms created problems that proved to be disruptive in mid-2018 as P2P investors, faced with the government’s emphasis on deleveraging, sought to monetize their assets only to find that many borrowers had defaulted or the platform owners had run off with their money. P2P lending collapsed in mid-2018, requiring regulatory standardization throughout the industry that would take a year or more to implement.23 Despite these problems, official support for further development of the P2P industry has continued in recognition of the scarcity of alternative credit sources for consumers and the many small businesses unable to access more conventional lenders.

SOE REFORM: THE PARTY RUNS THE ECONOMY

SOE reform is a contentious issue within China’s rebalancing strategy. Under the status quo, numerous “zombie” firms are kept alive with loans from the state-owned banks, mainly to maintain employment levels regardless of borrowers’ underlying competitiveness. Western economists prescribe more efficient measures, such as swapping debt for equity, encouraging firms suffering from temporary market setbacks to issue shares to management as incentive payments, or merging with more successful competitors. Uncompetitive zombies would be forced into bankruptcy. In contrast, Chinese reform objectives emphasize “bigger is better,” with government retaining its ownership of the largest SOEs and reshuffling their assets to reduce excess capacity while increasing their sectoral concentration. Private investors are meant to be attracted to specified “strategic” industries aligned with an import-substitution industrial policy. The expressed goal is to improve SOE efficiency and productivity, but the implicit goal is to do so without generating large-scale unemployment.

A long list of industries has been reserved for SOEs, including defence, state monopolies in oil and electricity, telecoms and transportation (for example, rail, aerospace, and auto producers), construction, finance, metals, and mining, although restrictions are being relaxed to permit 50 per cent private ownership on a case-by-case basis. Privately owned enterprises are dominant in manufacturing and a range of tertiary industries, including leasing and commercial services, scientific research and polytechnical services, information technology (IT), real estate, resident and other services, transport storage, and postal services, as well as, to some extent, health care and education.24

The planning mentality in SOE policy has a long history. Prior to the 1980s, SOEs accounted for 80 per cent of total output, a share that has since declined to around 20 per cent.25 As many as 150,000 SOEs still exist, however – two-thirds of them owned by local governments. SOEs account for about half of the national total of bank loans and for a major share of troubled corporate debt. Reforming the state sector involves at least partial privatization of some SOEs and allowing others to go bankrupt. Those that remain are gradually being consolidated and encouraged to grow through domestic mergers and international acquisitions. Rationalization of SOEs in polluting industries such as steel and cement will be managed according to such criteria as geographic concentration and their potential employment implications. The latter, indeed, are the subject of debate, with some prominent voices arguing that additional government funding should not go to the state sector if the primary purpose is to maintain jobs in zombie firms. The funds would be better used to help laid-off workers find new jobs in the private sector – the underlying principle being to “protect people, not companies or jobs.”26

The role of SOEs was intensely debated in 2013 at and following the Third Plenum of the 18th Party Congress, but the outcome was ambiguous. New goals assigned to SOEs reflected a mix of objectives. For example, SOEs were directed to develop new technologies and become national champions, but champions that were to maintain economic stability by investing when growth slows and by leading sectoral restructuring.27 Finance ministry proposals to impose budget constraints and rate-of-return objectives on SOEs were ignored. Instead SOEs were chosen to drive the transition to a more innovative, advanced manufacturing economy. In effect, the short-term outcome was to increase reliance on SOEs.

Mergers and acquisitions among SOEs followed, creating huge entities. In 2015 COSCO and China Shipping merged, creating the world’s fourth-largest container shipping company, and in November 2016 Wuhan Iron and Steel and Baosteel merged to form the country’s largest steelmaker. The State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, which is responsible for SOEs, has pushed for more and larger national champions. To that end, it has combined the largest railway equipment makers, and is reported to have its eye on chemical producers.28 In mid-2017 two other SOEs merged, one a very large coal-fired-power generator and the other the largest coal-mining enterprise, to create the world’s largest power generator.

Private capital has also been sought to revitalize SOEs. In a high-profile transaction in mid-2017, Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, JD.com, and Didi Chuxing rode to the rescue of China Unicom, the country’s second-largest telecom SOE, with estimated investments of nearly $12 billion in new and existing shares of the company’s unit listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange; SOE capital was also included, as China Life Insurance bought a large share (all dollar amounts in this book are US dollars).29

In 2018 SOEs also acquired troubled privately owned enterprises whose growth had slowed with the slower-growing economy and the introduction of measures to rein in shadow banks, on which such enterprises had depended for capital. By September, SOEs had acquired ten privately owned groups, touching off a debate about the negative effects of state ownership on innovation and revitalizing the economy. It was also noted that private groups in sectors dominated by SOEs, including steel, coal, and aluminum, had suffered disproportionately from factory closures and production limits.30

An outstanding question about these state-related reforms is whether size will matter more than performance and efficiency. Rationalization and modernization are required at the micro level to cut subsidies, reform tax incentives, place more emphasis on quality control, and promote best practices. A 2016 IMF study of the SOE reform strategy expresses scepticism that it will improve resource allocation. By IMF estimates, an alternative reform package of debt restructuring, hard budget constraints, more competition, and the provision of financial support to workers, rather than to firms, would, along with complementary reforms, raise output between 3 and 9 per cent in the medium term.31 This is a sober reminder of the cost of maintaining the status quo.

Some promising reform ideas are in play, such as allowing the award of share ownership to employees of SOEs in order to give them a stake in their firm’s commercial success. SOEs are also being reclassified as commercial or public services, allowing the former to be treated more like private businesses. Most public attention has focused on mixed ownership reforms like those in the China Unicom deal. SOEs that sell shares to private investors, however, can expect to be subjected to more challenging demands than would be forthcoming from the state. A key problem is that potential investors would be unwilling to become co-owners of zombie or struggling firms when the state remains reluctant to give private investors more strategic influence by allowing them majority stakes.

Giving boards of directors of SOEs more say is another reform option that has not materialized; instead the Party is increasing its own control. SOEs will continue to access cheap capital, but are expected to follow the government’s agenda. As noted earlier, SOEs are required to have an Enterprise Party Committee with a mandate to review major strategic decisions before they are presented to the board – with this imposition the Party, in effect, is acting as owner.32 SOE officials are also being subjected to stepped-up political education, making them more risk averse in the wake of the anti-corruption campaign and undermining both morale and performance. As Nicholas Lardy (2019) argues, the state has “struck back”: Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized the increasing importance of SOEs while reducing the roles of market forces and private enterprises.33

The drive for “national champion” SOEs has international implications. SOEs have moved into international markets in such industries as construction, steel, and railways to increase their business and participate in state-backed large infrastructure projects such as the BRI. If these national champions are seen to push other firms and bidders aside, they could provoke a public backlash against Chinese capital. Another source of potentially negative international reaction could be expected from huge “megamerger” SOEs that encounter execution difficulties – a common risk in completing mergers everywhere. Such difficulties and even failures of mergers could also create negative spillovers and backlash beyond the Chinese economy. A third concern is the appearance of state capital investment and operation companies, created to manage existing state assets and to invest in new assets, including in privately owned enterprises in the fast-growing consumer, health care, and IT sectors. Will state investors convert these more-productive private enterprises into SOEs, with consequential negative effects on efficiency and innovation? How wise will the state be as investor? Crowding out private investors could cause another backlash as investors demand state assistance in order to compete.

MORE BALANCE NEEDED FOR SUCCESSFUL ECONOMIC RESTRUCTURING

Chinese leaders’ reform strategy and pursuit of great power status for China will have significant implications for the rest of us. As we have seen, restructuring the supply side of the economy requires institutional and policy reforms and innovations that raise productivity and use available capital more efficiently. Further rationalization of inefficient and loss-making SOEs is unfinished business dating back to the 1990s, and then premier Zhu Rongji’s energetic campaign to withdraw intervention, permit bankruptcies, and privatize underperforming SOEs contrasts sharply with the mixed messages sent out today. Everyone has a stake in seeing China succeed, not least because of the political risks of negative spillovers should one of the world’s largest economies experience a financial crisis. Even in a more benign outcome, China will choose its own mix of state and market. The Chinese economy cannot be expected to converge with the market economies of the West, and Western countries, including Canada, will have to come to grips with that reality in learning to live with China.

The recurring theme in this book is thus one of tension and balance. Restructuring or rebalancing the Chinese economy is a clear objective. Balance is also sought between the Party’s political objectives for stability and freeing market forces to sustain economic growth at rates sufficient to avoid the middle-income trap. But tensions are evident. Xi Jinping has increased his autocratic control of China’s institutions of power. He has increased repression and prescribed greater political content in academic curricula and the control of universities and non-governmental organizations, presumably to rein in actions or writings that might challenge the Party’s legitimacy. The growth implications of this politicization of economic institutions and policy seemed to be secondary considerations. Yet, at the March 2019 National People’s Congress, leaders stressed risks to economic growth and moved to improve the business environment by reducing taxes. There were other signs of change, if not of changing the game, in the declining leverage of corporate China and local governments. China’s innovation performance will be a critical factor in its economic future and its influence in the world. Here again there are mixed signals from the state: encouragement to reach the technological frontier, but in state-approved ways, rather than by riskier, market-led, bottom-up innovations and protection of IP rights. Innovation is the subject to which I turn in the next chapter.