CHINA INVESTS ABROAD: A NEW ERA OF CHINESE CAPITAL

China’s outward direct foreign investment and mergers and acquisitions transactions boomed over the 2015–17 period, signalling a new era of capital and competition in the country’s long game to become a global power. By 2016 China ranked second to the United States in outward FDI; by 2017 its accumulated stock of assets, at $1.5 trillion, equalled its stock of inward FDI from the rest of the world.1

China’s history as an investment destination is well known, as is its outward investment record. Prior to its accession to the WTO in 2001, China sought foreign investment as a way to address domestic capital shortages. Investment approvals were case-by-case and restricted to activities that served the national interest. Outward investment was restricted and heavily regulated, totalling a mere $27 billion in 1999. WTO accession signalled Chinese enterprises to “go out” to increase their global competitiveness and access natural resources and technical expertise as part of the national investment-led, export-oriented growth strategy. The registration and approval of outward FDI was streamlined, and thresholds for investments in natural resource development projects were raised above those for other projects. Following the 2008–09 global financial crisis, investors took advantage of depressed asset prices abroad to acquire a wider range of foreign assets. As rebalancing slowed domestic growth in response, Chinese enterprises were motivated to seek new markets and foreign assets to maintain their growth. In 2016 outflows of FDI surged by 45 per cent over the previous year to $196.2 billion. With 13 per cent of the global total, China became the single most important home country and host economy among the emerging market economies.

Surging capital outflows attracted criticism and backlash, however, both in China and abroad. In China the outflows caused unanticipated exchange-rate depreciation and pressures on the capital account, undermining national development objectives. As noted in the previous chapter, a number of high-profile acquisitions of US entertainment and tourism enterprises – deemed by the authorities to be passive assets and “frivolous” acquisitions – helped to frustrate China’s investment objective to obtain natural resources and acquire knowledge and technologies. Foreigners also reacted warily to the rapid increase in Chinese acquisitions and the state’s active role in supporting Chinese investors seeking technology assets. Beginning in late 2016, Beijing cracked down on outward FDI, focusing in particular on that by highly leveraged privately owned enterprises.

To put this shift in context, one study finds that trade-related motives were prominent factors both in supporting China’s role as the top-ranked merchandise exporter among emerging market economies and in hedging against the erection of trade barriers against those exports.2 These motivations are evident in China’s growing presence in Africa and other areas where natural resources are found. Africans have been prominent partners as China has invested heavily in raw materials to take advantage of the major growth opportunities in that continent’s emerging market economies. To that end, in October 2018, at the seventh annual China-Africa Cooperation Forum, President Xi announced $60 billion in financial support for Africa.

As Chinese wages and production costs rose, efficiency-seeking investments gained in importance, as did projects to access technology, brands, and distribution networks. Chinese investors also sought to evade domestic regulatory restrictions or to gain financial advantage through round tripping and using outward FDI as a pretext to transfer financial wealth abroad.

Structural policies also influenced the growth of deals. Global financial advisory firms such as PwC and JP Morgan, close followers of trends in China’s outbound mergers and acquisitions,3 identified several such trends, including the emphasis on long-term sustainable (slower) growth, rising middle-class consumption, and more liberal and streamlined procedures in the regulatory and financial environments. Availability of competitive financing was another encouraging factor, as was the desire to hedge against a depreciating renminbi.

In late 2016, however, the investment atmosphere changed abruptly as the Party leadership became increasingly concerned about the systemic effects of rising corporate indebtedness and the effects on the exchange rate of the 45 per cent surge in capital outflows that year. Official scrutiny increasingly focused on some of the very large transactions completed earlier in the year, which had put downward pressure on the currency and drained foreign exchange reserves – sensitive issues in the wake of the serious financial volatility of 2015 and the large depreciation of the renminbi.

The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission ordered banks to re-evaluate loans to “some large entities” that had made large foreign acquisitions in 2016 and earlier. Three borrowers, Anbang Insurance Group, Dalian Wanda Group, and HNA Group, were singled out for closer scrutiny of their credit exposures. Acquisitions of businesses unrelated to their core businesses or stated objectives were of particular interest, especially ones that required transfers of large amounts of foreign exchange abroad or that relied heavily on debt financing originating in the home market. Although HNA and Wanda survived the scrutiny, albeit with changed behaviour, Anbang was a casualty for reasons discussed below, and the enterprise was dissolved.

MAJOR CHINESE MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS IN 2016

When Chinese entities began investing abroad in the 1980s, the initial objective was, as noted, to source natural resources and later to acquire producers in the developing world. Acquisitions in Europe and North America followed after the turn of the century. Most of these were small deals, but there were two large exceptions in the Canadian energy industry by Chinese SOEs: in 2010 Sinopec paid $4.6 billion for a share of Canada’s Syncrude, and in 2013 CNOOC acquired Nexen, an oil and gas company, in a $15 billion acquisition.

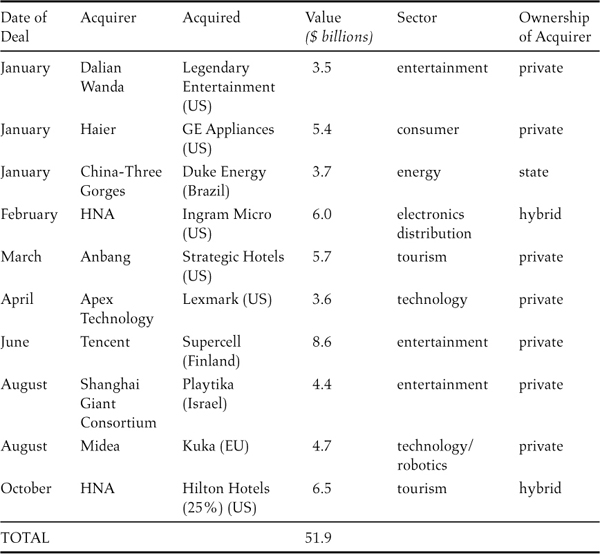

The capital surge that took place in 2016 included ten deals individually valued at more than $3 billion, listed in Table 4.1 and summarized below.4 Together they illustrate the diversity of investors and their sectoral targets. All but one investor was a privately owned enterprise or a hybrid in which ownership was unclear. US firms were targets in six of the ten acquisitions. As for their sectoral targets, entertainment and tourism dominated with five deals. Wanda, HNA, and Anbang became the focus of an official crackdown, however, on the grounds that their entertainment and tourism deals were not in the national interest.

Table 4.1 Top Ten Mergers and Acquisitions by Chinese Firms, 2016

Source: Yang Ying, “China’s top ten global M&A deals in 2016,” China Daily, 1 June 2017, available online at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/bizchina/2017top10/2017-06/01/content_29568764.htm.

Anbang Insurance Group: This company was founded in 2004 as an auto insurer, but quickly branched into asset management and became one of China’s largest insurance companies, with an estimated $114 billion in assets. In June 2017, however, Anbang’s chairman and founder was relieved of his responsibilities and in May 2018 sentenced to eighteen years in jail on fraud and embezzlement charges. Presumably because of these convictions, which reportedly are under appeal, in June 2018 nearly all of Anbang’s assets were transferred to the China Insurance Security Fund while the state sought a private buyer.

Anbang’s fall from grace followed a series of widely publicized international acquisitions in South Korea, the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Two US acquisitions were particularly high profile: the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in 2014 and a large share of Strategic Hotels and Resorts in 2016. A bid for Starwood hotels in 2016 was withdrawn, however, under pressure from Chinese financial regulators concerned about managing the risks of a large acquisition in an industry outside Anbang’s core competence in insurance.

Chinese insurers face a dilemma: their customer base is aging, and therefore their liabilities from insuring these customers are rising at the same time that asset growth is slowing in the home market. One way to resolve this dilemma is to acquire foreign-income-generating assets. Anbang’s approach was to grow its income in China by selling universal life policies – risky wealth-management products promising high returns in a short period but that contrast sharply with the longer-term, protection-focused policies offered by the industry both inside and outside China. Anbang also diversified beyond foreign insurance assets into real estate and hotels as it sought to escape the increasingly tightly regulated home market by moving capital abroad. Regulators reacted negatively to the evidence of this capital movement, especially into risky foreign real estate and hotels deemed to be outside Anbang’s core competence. In December 2016 the State Administration of Foreign Exchange moved to block acquisitions judged to be speculative, while permitting “strategic” acquisitions or ones with synergies with the acquirer’s domestic business in China.5 In May 2017 Anbang was suspended from issuing new products for three months because of its apparent tolerance of high risks in these products, which “deviate from the fundamentals of insurance.”

Dalian Wanda Group: This company was also singled out by concerned regulators, who focused on six of its recent foreign acquisitions. They restricted Wanda’s assets, directing banks to stop funding the acquisitions and to refuse any proposal by Wanda to use offshore assets as collateral for other financing. Regualtors also prohibited Wanda from injecting cash from its domestic businesses into offshore ones.

Wanda was founded in 1988 as a private company. It became active in commercial real estate – claiming to have developed its commercial properties into the world’s largest real estate enterprise – and aggressively expanded its Cultural Industries Group into China’s largest cultural enterprise. In 2015 the Dalian Wanda Group reported assets of $44 billion.6 Since 2009 the group has also pursued a number of international acquisitions in sports marketing and real estate, with deals in the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe. Those best known, however, are in entertainment, with high-profile US acquisitions that included AMC Entertainment, one of the world’s largest theatre operators, in 2012 and Legendary Entertainment in 2016. Regulators, however, labelling these as a “buying spree,” moved in July 2017 to restrict bank funding for further international acquisitions by Wanda or for transfers to its offshore subsidiaries. Wanda responded by selling a portfolio of tourism and hotel projects in China to a Chinese holding company and refocusing on its core real estate business model.7

HNA Group: In mid-2017 this company was subjected to intense scrutiny since, like Wanda, it had been on a “buying spree,” acquiring tourism and other assets valued at $40 billion over a twenty-eight-month period.8 By some estimates, HNA – a privately held conglomerate that has leveraged existing assets to fund the purchase of new ones – is one of China’s most aggressive deal makers.9 HNA was founded in 2000 as Hainan Airlines, which remains its flagship unit, and a local airfreight company on the island of Hainan. At its height HNA Group had as many as one hundred and eighty thousand employees worldwide. In 2015 it became a Fortune 500 company reporting $90 billion in assets. Its divisions include aviation, tourism, shipping, retail, real estate, and financial services. Its international assets have included New Zealand’s largest financial services firm, a stake in Hilton Worldwide, aviation service companies in fourteen countries, and a large shareholding in Deutsche Bank (before reducing its stake twice, in 2018 and 2019). HNA’s acquisition spree included thirty-five deals worth an estimated $27 billion. The 25 per cent stake in Hilton Worldwide was divested in early 2018 as changes in financial regulation in China reduced the possibility of rolling over debts in regulators’ quest to reduce leverage in large conglomerates such as HNA.

Unlike its real estate assets, however, HNA’s acquisition in 2016 of Ingram Micro, an electronics products distributor, was seen to strengthen its capabilities, in this case through the use of Ingram’s supply chain network. Ingram’s international profile was seen as a positive factor in the expansion of HNA’s foothold in emerging market economies. Since this transaction was also the largest-ever Chinese takeover of an American IT company, the deal was reviewed by US regulators on security grounds and subsequently approved. As with Anbang and Wanda, Chinese regulators scrutinized the transaction in June 2017 for its potential to contribute to systemic financial risk. Unlike with the other two, however, there are few signs of similar bank lending restrictions on HNA Group. Company spokespeople have defended its acquisitions as part of a disciplined strategy,10 yet in late 2018 HNA moved to sell Ingram as it sought to reduce its indebtedness.

Apex Technology: In contrast to the three preceding troubled companies, Apex Technology’s acquisition of Lexmark was quite straightforward. Founded in 2000 in Zhuhai, Guangdong province, Apex designs, manufactures, and markets inkjet and laser cartridge components and other core printer parts. It is one of the world’s largest manufacturers of global aftermarket imaging supplies and cartridge chips, marketed through a sales network that extends to more than a hundred countries. Apex is listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, with nearly 70 per cent of its shares held by Zhuhai Seine Technology. The Lexmark acquisition was a transaction that relates directly to Apex’s core business in the acquisition of a global brand, and with it, enlarged its market share, described by the company as a means to “build a global printer empire” and as a “landmark event for the global printing industry.”11

Haier: This company is well known for its successful emergence from modest origins as the collectively owned Qingdao Refrigerator Factory. With the company facing bankruptcy in 1984, its founder and chief executive officer, Ruimin Zhang, began its transformation into a global home appliance brand. He succeeded in transforming Haier from an imitator into a world-famous innovative company by constantly adjusting business strategies to the demands of the market environment. Haier internationalized by positioning itself as a local brand in various markets, rather than by acquiring local assets. It is now a multinational with more than sixty thousand employees, distributing its products in some twenty-five countries. In 2013 Haier was selected as Forbes Asia’s “Fabulous Fifty” company. In 1993 Haier listed a subsidiary, Qingdao Haier Refrigerators, on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, and in 2005 acquired a controlling stake in Haier CCT Holding, a publicly listed joint venture on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange.

With the acquisition of GE Appliances, Zhang is reportedly moving to transform Haier from a manufacturer into a distributor of consumer goods and services, including food delivery via the Internet. The aim is to become a networked company of independent business units that act like customer-focused startups. GE Appliances will be given considerable autonomy with respect to its future strategy and business development. For Haier this is a market-seeking transaction; for GE it is the successful exit of its North American brand manufacturing business, which had been on the market for some time. Haier sees the GE brand as a way to expand its market share while leveraging the brand with Haier’s innovative capabilities.

GD Midea Group: Midea was founded in 1968 in Beijiao, Guangdong province, to produce plastic parts. It then expanded into the production of electric fans and appliances, and in 1993 was listed as a public company on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange. It is now both a Fortune 500 company and a Fortune Global 2000 company. It is also China’s biggest appliance manufacturer and a close competitor to Haier as beneficiary of a government subsidy to rural residents to enable them to purchase modern appliances. Midea still leads Haier in retail sales volume, but this has been declining in recent years.

In 2016 Midea attracted international attention with its acquisition of nearly 50 per cent of German robot maker Kuka AG. Unlike some other transactions, this one was not about acquiring brand or an international presence. Rather, the purchase of the German company represented the acquisition of technical capabilities to apply to Midea’s existing China-based operations. Midea has said its goal is to transform its manufacturing with robot technology (it already uses Kuka robots in its factories), allowing it to reduce its workforce by 20 per cent by 2018. In 2014 smartphone maker Xiaomi took a 1.3 per cent stake in Midea with the intention of applying smart phones to home-appliance operations.

Tencent Holdings: This company, founded in 1998, describes itself as “an Internet Technology and Cultural Enterprise.” It is a leading provider of Internet value-added services in China, and has been listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange since 2004. Tencent provides social platforms and digital-content services through communications, information, entertainment, and financial services.12 By 2017 its computer gaming business was growing at an 11 per cent annual rate with the introduction of popular new games and eSports. Online gaming revenue grew by 28 per cent in 2017, and Tencent’s share of the Chinese online payments market was more than 39 per cent, second only to Alipay’s. In late 2017 Tencent’s market capitalization topped US$500 billion.13

Tencent emphasizes development and innovation capabilities, with more than half of its employees designated as R&D staff. Tencent Research Institute was set up in 2007 with a 100 million renminbi investment in campuses in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. The acquisition in 2016 of a majority stake in Supercell, a mobile game maker, for an estimated $8.6 billion expanded Tencent’s capabilities by adding a globally recognized innovator to its global games network. The acquisition of Supercell, whose games are played by one hundred million people daily, is intended to develop games for the global market. Supercell will maintain its base in Finland and contribute its production model of working in small independent teams or “cells” to the enterprise.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE 2016 OUTWARD FDI SURGE

The above cases illustrate both domestic and international drivers of business decisions to invest abroad. Investors seek new markets through trade and by the acquisition of new or better technologies, product brands, and better distribution networks. Escaping regulatory restrictions in the home market is also a common motivation. In the ten transactions listed in Table 4.1, three of the investors – Apex Technology, Haier, and HNA Group – sought to expand their global market share, while Tencent’s aim was to develop a global market presence with the Supercell acquisition. Brand seeking was also an evident driver in Apex Technology’s acquisition of Lexmark, a well-known global brand. Haier’s improvement strategy was also successfully leveraged into a brand, while Tencent deliberately sought a global brand that could be used to establish a more prominent presence in international markets – and to encourage innovation in existing operations. Relatedly, the Tencent acquisition and HNA Group’s hotel and tourism acquisitions aimed to expand core capabilities. Midea is the sole example of a transaction undertaken primarily to learn and use acquired technology to expand its core capabilities in its domestic operations, rather than abroad.

The three sizable enterprises that attracted regulatory attention and penalties aspired to enlarge their presence in international markets, but they were using financing strategies that regulators regarded as contributing to systemic risk in China. Anbang’s strategy was also designed to escape domestic financial regulatory restrictions by using foreign capital to diversify the term structure of its financial assets. Significantly, within three years, all three companies had unwound some or all of their foreign acquisitions.

These cases offer useful insights into larger policy trends in China. Chinese policy and regulatory frameworks had a significant influence on enterprise behaviour by encouraging firms to “go out.” With the shift in policy focus to rebalancing and restructuring the economy, the state-owned banks also changed firms’ behaviour through their willingness to accommodate domestic corporate borrowing, ostensibly to support real economic growth. This emphasis on debt-financed growth had consequences both intended and unintended, as evident in the three prominent cases where bank oversight of the actual uses of these funds appears to have been inadequate, as domestic funds were used to finance foreign acquisitions. In retrospect, however, it is apparent that acquisitions of foreign assets peaked in 2016 as regulators insisted that large foreign transactions be consistent with core businesses. SOE ChemChina’s acquisition of Swiss-based Syngenta for $43 billion, completed in June 2017, although a large transaction, was clearly one that would expand ChemChina’s core competence and bring valuable knowledge assets into the Chinese economy. Permitted transactions will still be funded by Chinese financial institutions, but there will be increased regulatory sensitivity to significant capital outflows and their exchange-rate effects.

Finally it should be noted that the lag in official recognition of the consequences of increased corporate leverage was partly due to the underdeveloped state of coordination among financial regulators and the central bank, and institutions such as the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce that are responsible for outward FDI policy. When the authorities recognized the potential systemic risks in late 2016, they increased regulatory scrutiny of acquirers’ proposed transactions and imposed capital controls to reduce pressures on the use of foreign exchange reserves to prevent unwanted exchange-rate depreciation. These measures were the main reason the investment boom ended. Thirty potential acquisitions of US and European assets valued at $75 billion were cancelled in 2016, including Anbang’s proposed acquisition of Starwood Hotels & Resorts.14 The effects of the changed policy environment are evident in the list of major transactions in 2017 in Table 4.2.

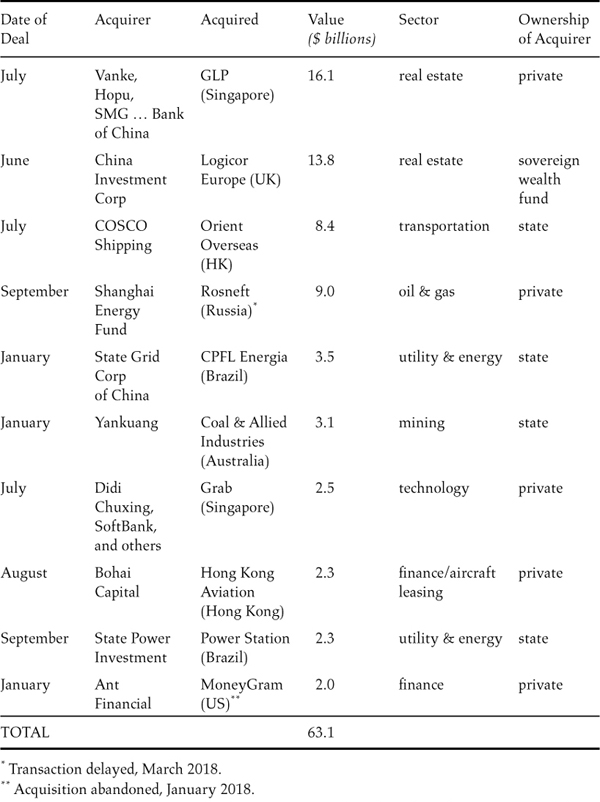

Table 4.2 Top Ten Mergers and Acquisitions by Chinese Firms, 2017

Source: Pan Yue, “2017 in Review: China’s Top 10 Outbound Deals Reflect Beijing Crackdown on ‘Unsound’ Investment,” China Money Network, 8 December 2017, available online at https://www.chinamoneynetwork.com/2017/12/08/2017-review-chinas-overseas-investment-remains-robust-140b-despite-tight-regulations.

A comparison of Tables 4.1 and 4.2 reveals marked differences in Chinese outward FDI in 2016 and 2017, with significant implications. In 2016 most of the acquired firms were American, with Chinese acquirers in the entertainment, tourism, and consumer products businesses (six of ten) and the remainder in technology and energy. In addition, most of the Chinese acquirers were privately owned enterprises. Three transactions in hotels and entertainment were unwound in response to regulatory pressures.

As Table 4.2 shows, major transactions reported in 2017 contrasted in several dimensions from those in 2016. Only one target firm on the list was American; the others were in Asia and the Pacific (including Australia), Brazil (2), the United Kingdom, and Russia (one each). It should be noted that the Bohai Capital acquisition was part of a larger set of transactions during that period, when Bohai Leasing, controlled by HNA, acquired Avolon Holdings, an aircraft leasing company owned by HNA, which in turn acquired the aircraft leasing unit of CIT Group, a US financial services holding company, for $10 billion.

Of the ten transactions, SOEs and China’s sovereign wealth fund accounted for five, while three of the five private acquirers were large equity players. The sectoral composition of these transactions showed a marked change from a year earlier, with the majority directly related to natural resources and related acquisitions. Four were in energy and utilities and mining, four in transportation and logistics, and two in technology. MoneyGram, the US acquisition, was abandoned in the face of regulatory pressures from the CFIUS. The bidder for Rosneft encountered both financial troubles and regulatory pressures that continued to delay completion into 2018.

Two main factors help explain the changes in sectoral composition of transactions over the two years. First, Chinese policy towards capital outflows was significantly tightened in late 2016 as the size of capital outflows “melted away” China’s foreign-exchange reserves and as policy placed more weight on the potential value of the proposed investments to China’s long-term development objectives. The second factor was changes in host-country policies towards the review and approval of outward FDI transactions. In the United States, where China is now seen as a strategic rival, there are increased political pressures for more stringent criteria to evaluate the implications of acquisitions of technology, evident in Ant Financial’s abandoned bid for MoneyGram.

Those sectors experiencing the largest declines in transactions were entertainment, consumer products and services, and real estate and hospitality – sectors deemed to have dubious value to national development. Less evident is the diversification into other sectors, such as health, biotech, IT, transportation, and infrastructure, that experienced stable investment and growth. Most acquisitions of US assets in 2017 were by privately owned enterprises, although SOEs were responsible for three deals in energy and mining.15

Changes in policies were the main driver of these sectoral and other developments. Tighter regulatory controls were placed on outward FDI by directing banks to limit the conversion of renminbi into foreign currency for foreign acquisitions and by informally blocking foreign investments that might cause large capital outflows. A new outward FDI management regime was also created that classifies sectors as encouraged, restricted, or prohibited. “Encouraged” firms include BRI-related infrastructure, investments that promote competitiveness in export markets and Chinese technical standards outside China, high-tech and advanced manufacturing investments, oil and gas, energy and mining, and agricultural and services sector investments. The “restricted” category includes real estate, entertainment, hospitality – the “guilty” sectors in 2016 – and financial investments unrelated to physical projects abroad. The “prohibited” sectors include businesses exporting unapproved core technologies, those prohibited by international agreements, or those that could harm China’s interests and security.16

A mid-year summary by New York-based Rhodium Group of the effects of this tighter regulatory oversight shows that new activity dropped by 20 per cent in the first quarter of 2017, but recovered somewhat in the second quarter.17 Moreover, large transactions comparable to those in 2016 were not repeated, and the declining size of the deals was then reflected in reduced capital outflows.

THE FUTURE OF CHINESE CAPITAL: UNCERTAINTY, OPPORTUNITY, AND RISK

By 2018 the slowing pace of new activity added to growing uncertainty about future trends in Chinese outward FDI.18 Rhodium Group’s 2018 summary estimates a drop of 84 per cent from a year earlier in the number of Chinese companies completing acquisitions and greenfield investments. In 2016 completed Chinese investment in the United States totalled $46 billion, fell to $29 billion in 2017, and in 2018 hit a seven-year low of $4.8 billion.19 Adding to Beijing’s crackdown on outward investment is increasing US regulatory scrutiny of Chinese acquisitions in the United States. Chinese private investors are now constrained at home by capital controls and tighter financial conditions that, among other things, limit debt rollovers, which had become a common practice. At the same time, US regulatory hurdles have increased the time and costs of completing transactions; indeed, HNA, Wanda, and Anbang are now selling US assets. Rhodium Group also notes the marked shift in sectoral composition towards investments in health and biotech. By mid-year 2018, Chinese venture capital investment in US biotech companies totalled $5.1 billion, surpassing the $4 billion record total for the entire year in 2017.20 Beijing’s new focus on medicine – cancer research, in particular – as a strategic sector had not yet attracted the attention of US regulators.21 The numbers of investments in hotels, real estate, and entertainment are still significant, but they are much smaller and do not cause capital outflows.

The policy trend is now clear but its trajectory is uncertain. China-US trade tensions and fears of a trade war reflect a heightened rivalry between the two superpowers touched off by two main factors. One is President Xi Jinping’s widely publicized ambitious goals for MIC 2025 to make China a world leader in advanced manufacturing, and his global connectedness vision for the Belt and Road Initiative. The other factor is the Trump administration’s increased focus on Chinese acquisitions of US technology, allegedly by unfair means, which the administration insists must stop. Tariffs are its weapon of choice, particularly the unilateral application of US Section 301 tariffs (on its trading partners, not just China) on a widening range of goods and the use of tariffs for national security reasons under Section 232 (b) of the Trade Expansion Act.

The effect of these US policies on Chinese outward FDI is likely to be negative. Tighter policies will increase transactions costs by widening the scope and processes of security screenings by the CFIUS and defining them in the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act. The US Department of Commerce is also being directed to impose stricter controls on technology transfers to foreign firms. These measures are discouraging Chinese FDI that might develop R&D facilities that have security or military applications, such as machine learning and semiconductors. Additional restrictions also might be forthcoming as outcomes of Section 301 investigations.

Although these developments imply growing restrictions on cross-border FDI to and from China, the underlying assumption – that China engages in forced technology transfers – should be evaluated against the statistical evidence. Missing from the popular narrative is evidence that China’s protection of intellectual property is improving. Nicholas Lardy has pointed out that China’s payments of licensing fees and royalties for using foreign technology nearly tripled between 2007 and 2017, and according to the IMF China ranks fourth in the world in the size of its annual payments to acquire technology.22 As well, the Canada-China Business Council reports that, in 2016, concerns about Chinese infringements of their intellectual property were of declining importance to Canadian businesses.23

The negative US stance also might create incentives for foreign manufacturers to localize production behind the US tariff wall. The European Union and other economies will continue to seek Chinese capital and business to offset their slow growth prospects. Host markets also stand to benefit as Chinese firms build channels in their value chains for foreign suppliers to access the Chinese market – access that could be useful to small firms in Western markets. In sectors such as e-commerce, electronics, machinery, environmental technology, and transportation infrastructure, Chinese firms are among the world’s largest and most advanced. Infrastructure firms, for instance, could provide channels for engineering and design firms to become suppliers to the BRI, which, among other things, seeks to facilitate adjustments by China’s old industrial sectors, such as iron and steel, by channelling excess capacity into infrastructure projects in underserved markets in neighbouring countries.

Given the potential opportunities, many host countries will continue to seek Chinese capital, including cross-border mergers and acquisitions, much of which will create benefits for world consumers as well as providing technological advances, price competition, and business innovation. Risks exist, however, that have policy implications.

FUTURE ISSUES: SYSTEM DIFFERENCES AND TECHNOLOGY

One key policy implication is that China is becoming a major global source of capital, a trend that will continue but perhaps shift in direction to countries other than the United States. Estimates of the magnitude of China’s outward flows illustrate this point. According to United Nations statistics, in 2017 China’s global stock of outward FDI was $1.48 trillion – the US total was $7.8 trillion – up from just $27 billion in 1999 and equivalent to 12 per cent of China’s GDP.24 If China’s GDP growth were to continue at 6 per cent annual rates and the ratio between outward FDI and GDP remained 12 per cent, by 2020 the total stock of Chinese outward FDI would be more than $1.7 trillion, a 13 per cent increase over 2017. The total might be even larger if the domestic economy grows more slowly and outward investment picks up in search of more global opportunities. Either way, the numbers are large.

Second, host governments that seek to minimize the risks of Chinese mergers and acquisitions while remaining open to the benefits of cross-border investment face substantial differences between the Chinese system and their own, as I recount in Canada’s case in the final chapter. In general, many market participants and analysts argue that some key changes are desirable in China, beginning with a more transparent regime to govern outward FDI. Moves in this direction were announced by the State Council in November 2018, and were included in Chinese commitments in China-US trade and technology talks in early 2019. Achieving this greater transparency, however, would require more robust regulatory capacities to enforce policies and ensure they have the desired effect on investor behaviour.

Political and policy differences also appear in commercial transactions, particularly those with Chinese SOEs, whose decisions might be driven by political, rather than commercial, criteria. This is a particular concern to Canadians. Separating government ownership from enterprise management is a challenge that could be addressed by introducing modern corporate governance practices and applying more stringent transparency requirements to SOEs. Although accounting and external audit practices are gradually becoming more independent, the pace is slow. Financial investors also might have objectives that conflict with national policy objectives – evident in Chinese regulators’ concerns about firms using mergers and acquisitions as a form of capital flight, as hedges against currency devaluation, or in response to the anti-corruption campaign.

Host governments nevertheless should remain open to the net benefits of Chinese investment. Until recently there were relatively few barriers to Chinese FDI in North America or western Europe. Since 1975 the United States has relied on the CFIUS to screen proposed acquisitions for national security concerns. Screening has been reasonably light handed, and few deals have been formally blocked. But rising geopolitical tensions and rivalry are changing this behaviour as the US administration imposes tariffs on a widening range of Chinese goods and China retaliates. Some, perhaps many, Chinese firms are likely to look for alternative investment locations such as Canada and Europe, while adding to the Chinese presence in Africa, Latin America, and eastern Europe.

Canada, too, has a record of accepting Chinese mergers and acquisitions, with ninety-seven deals completed between 1996 and 2015 – again, mostly small, with only six having reported values of more than $1 billion. Despite this apparent openness, however, in the past decade the OECD has rated Canada as having an opaque FDI screening system, requiring security screening, a “net benefits” test, and, since December 2012, a restriction on SOEs owning controlling stakes in oil sands companies other than in unspecified “exceptional circumstances.” Canadian authorities have blocked few deals, although the rejection of a hostile bid for Potash Corporation by BHP Billiton of Australia in 2012 was highly visible.25 The current federal government has signalled its desire to attract Chinese capital to aid its growth objectives, but has made few changes to address the OECD’s criticisms of the opaque screening regime.

Western Europe has also been relatively open to Chinese investment, with 362 completed deals between 1988 and 2015, twenty-one of which had reported values greater than $1 billion. Some countries do not have an investment screening regime. It is not clear whether current pressures arising from lagging economies, immigration debates, and Brexit negotiations risk creating barriers, but European and Chinese leaders recognize each other’s economies as significant partners through trade and capital flows. Recognition of the risks we outlined earlier suggest the need for a clearer framework for the European relationship by negotiating bilateral investment agreements or developing a joint dialogue with both the United States and Canada on the elusive goal of global governance for investment, which inevitably must include China.

The third implication is growing political concern about China’s pursuit of high-tech deals. Already there is a backlash in Europe in the wake of bids by Chinese firms seeking to leapfrog competitors by acquiring advanced technology – Midea’s quest for Kuka, discussed earlier, is an example – and it is a significant concern in US debates about reciprocity and openness to international trade. These concerns have implications for industry competition, technological development, and national security. The core challenges are respect for and enforcement of intellectual property rights, non-discrimination, and reciprocity in market access. Chinese firms are developing technical skills by learning from their Western competitors through the purchase of technologies and through acquisitions. Yet foreign firms in China continue to report requirements for quotas and local content, denial of market access, and discriminatory industrial policies to force technology sharing. This lack of reciprocity is becoming a powerful factor in the growing US sense of unfairness concerning China-US trade, which the current administration is using to justify labelling China a strategic rival.

CONCLUSION

China’s new era of capital and competition has attracted an increasingly intense US backlash in response to China’s stated technology ambitions and unfair policies and practices to acquire foreign technologies. Backlash is not limited to America: charges of unfair business practices have been levelled at China’s state-owned financial institutions for their lending practices in Malaysia, Pakistan, India, and Myanmar.

Although the long-standing objective to “go out” remains, China’s outward investment boom peaked in 2016 because of problems at home, negative effects on the domestic economy, and revealed weaknesses in China’s regulatory frameworks. The top ten investments in 2017 indicate a changing composition of investors and acquisitions as Chinese corporate decision makers wrestle with the effects of the country’s slowing growth and declining returns on investors’ domestic assets. These are reasons to expect the pace of Chinese outward FDI to continue to slow. At the same time, the United States’ dramatic expansion of export controls on sensitive technologies and increasingly restrictive approach to approvals of new transactions mean that Chinese outward FDI flows are likely to be directed to countries in Europe, Africa, and those along the Belt and Road, the initiative to which I turn next.