THE BELT AND ROAD INITIATIVE: CHINA REACHES OUT

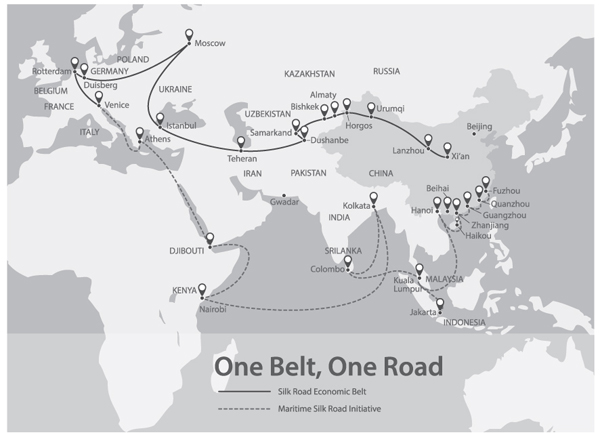

When President Xi Jinping launched the westward-leading One Belt, One Road initiative in 2013 to connect China with its Eurasian neighbours, he described it as the modern version of the ancient Silk Road, a global public good widely accessible to all. As the project evolved, it was renamed the Belt and Road Initiative for its proposed maritime (Belt) and land (Road) routes that would connect more than sixty-five countries estimated to account for a third of global GDP and two-thirds of the total population (Figure 5.1).1 These are countries desperate to improve their infrastructure to increase their long-term growth potential. Estimates of total investments over the life of the project vary between $1 trillion and $8 trillion.2

Figure 5.1 The Belt and Road Initiative

Source: iStock.com/hakule.

In its first five years, what began as a regional infrastructure initiative became a prominent feature of Xi’s long game to expand China’s global presence. There are many different views of the BRI’s potential, but it has variously been called the latest phase in the rationalization and expansion of China’s earlier reform and opening up,3 the “largest overseas investment drive ever launched by a single country,”4 and as “the project of the century,” with potentially game-changing implications for China’s global influence and for the balance of power.

The BRI has also had bad headlines, however, including about practices of “debt trap diplomacy” and the initiative’s being a new form of colonialism. Financial flows in the initial phase of the BRI have been dominated by bank loans channelled to neighbouring countries and to resource-rich developing economies. Some argue that these flows, along with development aid and financial support, are intended to support China’s goal of becoming a leading member of the international community by encouraging other countries to enter its system of rules.5 But Australian strategic studies expert Hugh White argues China’s motive is to consolidate its position at the centre of global supply chains and manufacturing networks. To that end, the BRI provides an opportunity to develop technologies and set standards that will have global significance as China consolidates its position as an upper-middle-income country.6 Still others argue that the BRI is a way to deploy China’s excess industrial capacity and production to its less-developed neighbours. Jin Liqun, founding president of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) founded by China, counters that, although the initiative has attracted attention to China’s own interests, its central purpose is to promote connectivity and economic integration as a public good accessible to all by investing in badly needed infrastructure projects across Asia, into Europe, Africa, and, more recently, Latin America.

In May 2017, President Xi chaired the inaugural Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, attended by twenty-nine heads of state and delegates from more than one hundred countries. The Forum celebrated the creation in 2015 of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank with US$100 billion in initial capital that sets the rules, but ones that are very much in line with international norms. China is also cooperating with the other so-called BRICs group of developing economies – Brazil, Russia, India, and China – to create a New Development Bank to mobilize resources for development projects.7

Although Chinese leaders’ objectives for the BRI sound grandiose, even visionary, the challenges lie in implementation. In its first half-decade, the BRI’s record is a mix of successes and significant problems, of learning about the inevitable weaknesses and major problems of infrastructure projects. Infrastructure megaprojects have a venerable history in both developed and developing countries of providing new facilities and connectivity, whether in post-conflict reconstruction, projects to update and modernize facilities, or projects for economic development. But large, long-term, cross-border infrastructure investment projects that appear politically attractive – indeed, the long-term benefits of well-planned, well-timed projects are substantial – are fraught with political and practical risks.

The BRI’s reported sources of finance have relied heavily on debt finance through loans from China’s policy banks and state-owned commercial banks. A review of high-profile problem cases leads to the conclusion that much work is needed to standardize governance procedures and lending standards among this plethora of lending institutions. Institutional reforms could also help to diffuse project risks. In the absence of such change, there are many reports of political backlash generated by Chinese interests, policies, and business practices. Continuing these practices could undermine both China’s reputation and the BRI’s future prospects, and have undesirable geopolitical effects in the light of the US decision to brand China as a strategic competitor.

THE BRI’S MISSION AND PERFORMANCE SINCE 2014

The BRI has both international and domestic objectives. At the local level, Chinese authorities see the BRI as a way to develop connections between youthful populations in neighbouring countries and the aging Chinese population and China’s shrinking labour force. BRI megaprojects also might be of a scale that allows China to redirect excess production by industrial SOEs – such as steel and cement makers – to new markets where demand is growing. Developing new markets, in turn, could open opportunities to shift the composition of Chinese exports from consumer goods produced by the “world’s workshop” to higher-value-added capital goods. For example, telecom equipment, construction machinery, and turbines will all be in demand as the economy restructures to produce more services in construction and engineering and to realize China’s goal to lead in advanced manufacturing.

In 2017 the Fitch ratings agency reported that BRI projects worth US$900 billion were either planned or under way.8 Since then the results and implications have begun to appear. A wave of fundraising and institution building since 2014 has created a number of prominent infrastructure projects. A centrepiece is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which runs from the Chinese border through Pakistan to the port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea. Other major projects include construction of an oil pipeline through Myanmar to Yunnan province, and development of the Greek port of Piraeus into a transshipment hub for trade between Asia and Europe. China’s tech giants are also engaging with the BRI as Alibaba and Ant Financial invest in Bangladesh and develop mobile payment and digital financial services in Pakistan through a strategic partnership.

Chinese financial institutions have allocated significant funding to the BRI. In 2014 China’s sovereign wealth fund created a Silk Road Fund of $40 billion. The Financial Times has reported that, by the end of 2014, two major Chinese policy banks had made loans of nearly $700 billion,9 while in 2015 $82 billion was transferred by the Chinese state to three state-owned banks to fund BRI projects.10 By the end of 2017, the AIIB had approved twenty-three projects and invested $4.2 billion; projects tended to cluster in the energy sector (ten) and in transportation (six) as a variety of infrastructure projects got under way in thirteen countries: Azerbaijan (1), Bangladesh (2), Georgia (1), India (5), Indonesia (3), Myanmar (1), Oman (2), Pakistan (2), the Philippines (1), and Tajikistan (2).11 Information on the cost of funds is scarce, but available data show that the majority of these projects were financed by loans. The Chinese Ministry of Commerce reports that the Silk Road Fund had invested US$6 billion in fifteen projects, while the China Development Bank had issued US$168 billion in loans, and loan commitments by the Export-Import Bank of China totalled more than US$101 billion. Three state-owned commercial banks had also provided credit.

Some estimates of the potential effects of the BRI on trade and investment flows in the region and on actual and potential growth are available. The Economist Intelligence Unit estimates that, by the first quarter of 2018, most BRI trade and investment flows were accounted for by ten countries, with Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Russia in the lead – understandably, since project development in these economies would be easier than in less developed ones. Pakistan’s significance is largely determined by the transportation potential of the CPEC.12

The Ministry of Commerce also reported in May 2018 that trade deals had risen by 19.2 per cent, year over year, in the first quarter of that year, while non-financial investment grew by 17.3 per cent. Free trade negotiations were reported to be under way with three countries, including Pakistan, and seventy-five economic and trade cooperation zones were being created with BRI countries.13 A May 2017 report from the state-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council announced that forty-seven central government SOEs were then involved in 1,676 projects in BRI countries.14

In these projects, there is a noticeable focus on land-based infrastructure, while growth in trade and investment is slow. Although detailed data from English-language sources are sparse and many reported projects predate BRI, one indicator that reflects expanding economic potential and reduced trade costs is the increased transcontinental rail services that are beginning to replace costly and slow-moving ocean transportation. By the end of 2016, forty such services had appeared, connecting cities in China and Europe. Seventeen hundred freight trains travelled from China to Europe in 2016, double the traffic in 2015.15

In March 2019 the BRI reached a new phase in its mission when the Italian government became the first G7 country to endorse the initiative. Rome’s reported objectives are twofold: to attract Chinese investments that will enable it to diversify beyond dependence on Brussels, and to sell “Make in Italy” in China. China’s motives are more strategic: to attract Italy into a dependent relationship by offering needed investments in aging Italian ports, and to extend Xi Jinping’s vision of the BRI as a platform connecting China and Europe. The European Commission, for its part, has adopted a view similar to that of the United States, branding China a “systemic rival” that treats European companies unfairly.16

INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS: SOME RISKY CASES

Balancing these developments are indicators of significant risks, particularly those of indebtedness as governments struggle with debt repayments to Chinese financial institutions. Sceptics focus on both the quantitative and qualitative characteristics of project management by Chinese institutions and ask whether the BRI is a development agency or a new form of colonialism.17 Some large BRI projects have attracted particularly intense international criticism because of the practice by Chinese lenders of requiring compensation in the form of equity stakes when borrowers are unable to repay loans – instead of, for example, rescheduling or forgiving the debts. Some argue that Chinese financial institutions are self-interested and purposely resort to expensive debt financing to acquire key assets such as ports.18 Others counter by arguing that host countries might have domestic problems they are unable to manage and that Chinese interest rates are quite reasonable. Five cases illustrate the risks some borrowers and lenders have faced.

The BRI Centrepiece: The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has gained prominence as a BRI project both for its significant scale and location and because of rising concerns about Pakistan’s apparent inability to service its Chinese debts. The CPEC also has geopolitical significance as a land corridor linking southwestern China and the Arabian Sea through Gwadar, a potential gateway due to its location near the Strait of Hormuz, through which a fifth of the world’s oil passes. By agreement between China and Pakistan, 91 per cent of Gwadar’s port revenues for the next forty years will go to the port’s operator, Chinese Overseas Port Holding Company, and 9 per cent to the Pakistan government.

The CPEC is also the site of industrial development, energy, and infrastructure projects – including a highway, railway, and pipeline – expected to total an estimated $60 billion.19 At least $33 billion is expected to be invested in energy projects, with China providing 80 per cent of the financing, reportedly at high interest rates.20 The scale of Pakistan’s public debt-to-GDP ratio – nearly 70 per cent in 2017 – has attracted IMF concerns about its ability to service that debt.21 Already China has moved to halt funding for three infrastructure projects. Progress on the Gwadar port is also slow, with few new berths to attract cargo vessels beyond those bound for Chinese projects located in the immediate area.22 In late 2018 Pakistan reduced the scale and cost of the Karachi-Peshawar railroad project.

Other Problem Cases

In 2016, Sri Lanka and China agreed to develop lands adjoining the port of Hambantota, already a $2 billion underperforming investment and one that other lenders had refused to fund. There was also stiff resistance from Sri Lankan workers to the proposed land acquisition for an adjoining industrial park, who complained it would become a Chinese settlement. When the Sri Lankan government found it impossible to service the existing debt, the newly elected president sought and received $1.1 billion debt relief in exchange for granting a ninety-nine-year lease to a Chinese bank holding company on 80 per cent of the port.23 Reports of this development attracted international criticism of China’s objectives, a subject of considerable sensitivity around a project in such close proximity to India. Added to general concern was the existence of a similar deal made in Greece in 2016, when a Chinese shipping company was permitted to acquire a 67 per cent stake in the Port of Piraeus. As a result, China was developing a reputation for practising “debt diplomacy” by agreeing to loan-financed projects that countries might be unable to repay, which would affect their public finances and undermine their ownership of infrastructure assets.24

In another case, an investment by CITIC, a state-owned Chinese financial institution, in Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar drew international criticism of its estimated $7.5 billion price tag as unnecessarily expensive, and raised questions about the risks of future debt distress and the strategically important port’s falling into Chinese hands.25 A more recent case with a high public profile is in Malaysia, where the costs of “unequal treaties” between Chinese SOEs and Malaysian interests for Chinese projects on the drawing board became a subject in that country’s May 2018 general election. Projects valued at $23 billion were suspended, including the $20 billion China-backed East Coast Rail Link, the BRI’s single largest project, and three pipelines. After the election, President Mahathir Mohamad set out to renegotiate the terms of project financing and, even though construction had started, he temporarily cancelled the project in early 2019. Pushback from elsewhere in the region about this BRI “failure” might have been a factor in China’s subsequent agreement to renegotiate the project for a more modest price. As Mahathir observed, “China doesn’t conquer countries, but increases its influence.”26 His actions marked the first time an Asian government had pushed back against the BRI in such a public way.

Taken together, these cases raise questions about the professionalism of project finance decisions by lending institutions and accusations of “debt traps.” One China scholar, a student of the ancient Silk Road, has noted a historical parallel between the terms for leasing the port of Hambantota to China and those of the China’s Qing rulers in ceding Hong Kong to the British.27

RISK MANAGEMENT IN INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS

This partial litany of difficulties and shortcomings in some high-profile BRI projects, of which that in Pakistan is one of the largest, indicates the importance of risk management, project design, and project finance in unleashing the BRI’s economic potential. The IMF, in its spring 2018 evaluation of Pakistan’s economy, warned of the country’s rising current account deficit (4.8 per cent of national income), fiscal deficit (in absolute terms soon to be the highest in history), and estimated foreign currency reserves that are less than required to finance ten weeks of imports. In July 2018, following his election as president, Imran Khan revealed that Pakistan was so deeply in debt that he would have to seek IMF support. In October 2018 he followed through with a formal request for a bailout.

TWR Advisory Group, a Washington-based consultancy, estimates that, overall, BRI projects worth $419 billion, or 32 per cent of BRI total lending, have encountered performance delays, public opposition, or national security controversies.28 A detailed evaluation of the performance of BRI projects indicates the need for a strong focus on debt sustainability – the provision of debt financing of a size that a country can repay without incurring “debt distress.” The Center for Global Development in Washington29 found that twenty-three of sixty-eight countries eligible for BRI lending were vulnerable to debt distress, adding substantially to the risks – which will only be magnified by additional lending. In eight countries, any BRI financing would add to the risks of debt distress.30 The Center for Global Development also reminds us that infrastructure is a critical engine of growth in developing economies, but that with debt financing the fuel for this engine is public borrowing and should therefore support productive investment. Too much debt can have significant negative effects: if a country’s growth performance is insufficient or revenues are inadequate to cover debt-servicing costs, its government will encounter debt distress and need to reduce or restructure its debt or, at the extreme, to default.

Ideally such project risks are minimized by careful project selection and risk sharing. Only projects that are financially, economically, and politically viable should be selected. They should also be environmentally and socially sustainable. Once selected they should be managed, recognizing that the growth effects of different investments will differ. This means risks should be diversified and reduced by, among other measures, partnering with other lenders and investors. Investment decisions should be decided jointly with the host country, rather than unilaterally by the lender, and assistance should be made available to indebted countries to repay their loans. Better public relations are required, including transparency with the local media and host communities, and investing companies should train local labour forces and work with all stakeholders, rather than focusing on the party in power.31

Partnering with other lenders and investors is of particular relevance to the BRI, especially in the early days of AIIB-funded projects, when precedents are created. Chinese investors might believe they achieve “multiplier effects” by relying mainly on other Chinese financing sources instead of partnering with established multilateral lenders such as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank. But such a China-first strategy has already had negative consequences, including the perception that China “hijacks” projects. Instead of helping to expand China’s international influence, smaller countries might hedge by seeking closer relationships with other large countries. Quality controls in the AIIB are essential. The BRI’s long-term vision will bear fruit only if investments are seen to be of value to people in the region and to provide payoffs to Chinese and other foreign investors.

In light of the BRI’s focus on public investment in infrastructure, lessons on project design could be applied based on the extensive experience of multilateral development banks and other institutions. For example, infrastructure investments could be timed to counter severe cyclical downturns, such as that following the 2008–09 global financial crisis. Carefully chosen investments in real assets, combined with coordinated expansionary macroeconomic policy, could help offset the recessionary effects of lower demand, maintain consumption, and stimulate growth through capital spending. Such spending would increase aggregate demand and supply, raise productivity, and generate future economic returns. Importantly, fiscal expansion of this kind has been most effective as part of a cooperative strategy among countries, rather than by one government’s acting on its own. Such spending is also more likely to have the desired effect if applied to already-approved projects that are more likely to expand aggregate demand quickly.

Another lesson from past experience is that not all forms of infrastructure spending have the same growth effects. Energy, communications, and transportation investments facilitate economic activity; maintaining and renewing infrastructure stocks often provides higher returns than new investments. Location also matters, since investments in one place can have spillover effects to other locations, especially in urban areas. Efficient public investment can serve as a catalyst for growth by supporting or enabling the delivery of key public services and by connecting firms and citizens to economic opportunities.32

Note, however, that it is possible to overinvest in infrastructure. Avoiding this outcome requires careful testing of public finance decisions for their strategic importance – and ensuring such projects will generate positive returns. It has been shown that efficient public investment can double the growth effect over time; investment thus should go far beyond short-term stimulus to enhance both productivity and long-term growth prospects.

Two other factors to take into account in project design are, first, the importance of accompanying changes in structural policies to remove obstacles to growth or to free up growth processes; and, second, the need for high standards in lending decisions. The AIIB, in particular, should make high-quality and inclusive lending decisions, not convenient political ones. Achieving this objective would require the implementation of prudent lending standards and the working out of an agreed approach to handling debt distress. Indeed debt distress – its causes and management – is of particular concern as lending by China’s policy banks ramps up. As noted earlier, the China Development Bank and the Export-Import Bank of China have already made large loans that will require repayments totalling nearly $700 billion – equal to the total lending of the World Bank and six regional development banks.33 According to some reports, China might be running out of resources to support the BRI because very few projects are financed in renminbi, which make the BRI dependent on a limited supply of US dollars. This development alone might push China to co-finance projects with multilateral institutions.34

The absence in the BRI of standardized procedures for pricing assets and of procedures to follow with respect to distressed debt in the event of project failure has undermined China’s reputation amid charges of “debt trap diplomacy.” The Center for Global Development argues strongly for the adoption of the same or harmonized prudent lending standards by all international organizations. A similarly agreed approach to managing distressed debtors is also required. There is much to learn and apply in this regard from the experience of the OECD-based Paris Club, a well-respected multilateral institution founded in 1956 that coordinates sustainable solutions to the payment difficulties encountered by debtor countries.35 The Center for Global Development recommends a revised Paris Club organization that would include China as an architect to update its collective approach. The Export-Import Bank of China alone has credit exposure of $90 billion, so there is a strong argument for revising the existing coordinating institution to include China.

The importance of these concerns are illustrated by examples in Southeast Asian countries, where China’s lack of experience with investment projects leads project managers to choose to work instead with Japanese, European, and US institutions, even if initial Chinese bids are financially and politically attractive. A recent example is a high-profile Chinese bid to supply high-speed rail in Indonesia.36 Japan had worked on a project proposal that was overtaken by one from China based on the bidder’s record of building such projects in China and on its financial capacity. The Chinese bidder readily met Indonesian conditions, including omitting a state guarantee on the project loan, waiving the requirement of a budget contribution from the Indonesian government, accepting to enter into a joint venture with Indonesian partners who would receive majority control, and other production and job-creation promises. In 2015 the Chinese consortium won the project by accepting unusually high financial, operational, and political risks. The project then hit a wall: eighteen months after breaking ground, construction still had not begun. One reason was that Jakarta had encountered difficulties obtaining the land required for the rail line, indicating lack of planning and preparation. This is not an isolated case. China has developed an international reputation for producing high-speed trains, but managing in foreign markets is challenging because of Chinese firms’ lack of planning and preparation and their inadequate understanding of local markets and institutions. As a result, while China’s trade with Southeast Asia flourishes, its investment performance in the region is weak.

BACKLASH: MIXED MESSAGES AND BAD NEWS

This focus on the need for risk management might suggest that China’s infrastructure diplomacy has backfired, with major reputational costs. Yet one of China’s objectives is to win new friends. To increase the probability of achieving that objective, Chinese lenders should draw upon accumulated experience at the World Bank, the multilateral development banks, and national aid programs to “up their game” in terms of standards setting and debt sustainability.

Much can be done to reduce risk and improve future performance.37 Multilateralizing the BRI is an obvious option, but potential partners might have reservations about the economic viability of the projects and less tolerance of high levels of corruption and other institutional weaknesses in borrowing countries. Also noted is the absence in the BRI of uniform standards to ensure the fair pricing of debt and agreed procedures to follow if a project fails. Relationships between China and host governments are also seen as important; joint involvement in project development and decision making, though desirable, is often lacking. Greater willingness on China’s part to assist debtor countries to repay loans is also desirable – for example, it could help them develop product markets in China. As well, project managers should be more willing to use local sourcing to counter criticism that they rely too heavily on imported Chinese materials, equipment, and labour.

A potentially significant development in late 2018 that could ameliorate these risks was the agreement between President Xi and Japanese prime minister Shinzō Abe to embark on joint infrastructure projects as the two governments move to normalize their difficult political relationship. By engaging China in this way, Japan has recognized the opportunity to shape BRI strategy, gain added business for Japanese firms, and initiate a cooperative process with potentially positive geopolitical implications. Of even greater consequence, China’s engaging with Japan could also help to address criticism that the BRI is a hidden long game in which China pursues its own agenda and geostrategic goals using Chinese-financed, Chinese-constructed transportation infrastructure to expand its military reach. Notably, unlike Italy’s endorsement of the BRI, through which it seeks Chinese capital, Japan’s overture initiates a new era of cooperation in building infrastructure.

What is less clear, while the BRI is enhancing these regions’ economic potential through its emphasis on infrastructure, is whether the new investments will conform to Chinese standards and use Chinese technologies, including high-speed trains and data networks. Although still a distant prospect, some analysts have suggested that one day the BRI might challenge the Western rules-based order.38

Be that as it may, conduct of the April 2019 Belt and Road Forum illustrated some Chinese flexibility and a shift of emphasis to the BRI as a win-win proposition. One hundred countries attended the Forum, thirty-six of them sending their head of state. The Chinese host’s tone was subdued even as officials reported Chinese companies had invested $90 billion in BRI projects and that, during the 2013–18 period, Chinese banks had extended $200–$300 billion in loans.39 Xi Jingping’s address was conciliatory, emphasizing the reform and opening measures announced at the 2019 session of the National People’s Congress. These measures included expanding market access for foreign investors without Chinese partners, intensifying protection of intellectual property, ending forced technology transfers, engaging more in macroeconomic coordination and relying on market forces in renminbi valuation, and adopting a binding mechanism to honour agreed international laws and regulations.40

More immediately, attention is required to address the practical difficulties – including project selection, design, and risk management – of fully realizing the potential economic returns from BRI projects. Although debt distress is a risk, it can and should be managed according to internationally recognized standards, rather than leaving partner country institutions indebted to Chinese banks. As noted, there are early signs that Beijing is holding itself more accountable on these issues; with the BRI as the Chinese leader’s signature global initiative, Beijing could hardly do anything less.