6.00: Improper Play, Illegal Action, and Misconduct

Until 2009, right-hander Frank Chapman was believed to be one Frederick Joseph Chapman, born on November 14, 1872, and at age fourteen the youngest player in major-league history. But those vital statistics we know now belong to an upholsterer in Erie, Pennsylvania, who may never have played ball at all, let alone pitched a game in the majors. Thanks to researcher Richard Malatzky, we’ve learned Chapman was a minor-league pitcher whose real first name was Frank, and that he was born in 1861.

Chapman’s lone major-league appearance came on July 22, 1887, in the uniform of the American Association’s Philadelphia A’s and ended on one of the strangest batter’s inference calls ever made. Opposing Chapman that afternoon were the fledgling Cleveland Blues, who had joined the AA in 1887 as a replacement for the Pittsburgh Allegheny club (after Pittsburgh had jumped to the National League). By the bottom of the sixth inning, Philadelphia trailed, 6–2, but had a rally going with Harry Stovey on third and Lou Bierbauer on first with hard-hitting Ted Larkin at the plate. On a pitch to Larkin, Bierbauer jogged toward second base to draw a throw from Cleveland catcher Charlie Snyder and Stovey then raced for home when Cleveland second sacker Cub Stricker ran Bierbauer back to first. Seeing that Stovey would be out when Stricker suddenly wheeled and threw home instead, Larkin wrestled with Snyder, allowing Stovey to regain third base. Umpire Mitchell (first name unknown) at first called Stovey out, a call befitting today’s Rule 6.01 (a) (3) on batter’s interference, but then reversed himself and called Larkin out.

While Cleveland was rightfully arguing that Stovey should be the one ruled out, Mitchell, to the astonishment of everyone, abruptly forfeited the game to the A’s. Just as astonishingly, AA president Wheeler Wikoff later upheld the forfeit. Because Cleveland was leading when the game was forfeited, no pitching decisions were awarded and Chapman was spared a likely loss. As for Mitchell, the forfeit came in the second of the only three games he umpired in the majors before departing without leaving behind a shred of biographical information.

The vast majority of the time, a player who continues to behave as if he were a base runner after he has been called out will be nailed for interference, but there have been notable instances when an umpire chose to rule otherwise. In the bottom of the sixth inning of Game Four of the 1978 World Series at Yankee Stadium on October 14, the Yankees trailed the Dodgers, 3–0, but had Thurman Munson on second base and Reggie Jackson on first with Lou Piniella batting. Piniella hit a line shot to Los Angeles shortstop Bill Russell, who dropped it. There was some question whether Russell dropped the liner on purpose, hoping to set up an easy double play, in which case Piniella would be out according to Rule 5.09 (a) (12) and Munson and Jackson would not be forced to vacate their respective bases. However, second-base umpire Joe Brinkman made no call, so the play continued. Russell retrieved the ball, tagged second to force Jackson, and then fired to first expecting to double up Piniella. But the ball hit Jackson, who was continuing to run, and bounced off down the right-field line into foul territory. Before the errant peg could be chased down, Munson scored and Piniella reached second.

It then fell on first-base umpire Frank Pulli to judge whether Jackson was guilty of interference. Instant replay angles gave the impression that Jackson not only had continued to run after being forced at second but also may have flicked his hip into the path of the throw. Pulli thought otherwise, contending that Jackson neither had intended to interfere with the play by continuing to run nor with the throw when he saw it coming toward him. The Dodgers vehemently dissented, but Pulli’s call stood and the Yankees eventually scored two runs in the inning and wound up winning the game, 4–3, and eventually the Series.

This rule allows an umpire considerable latitude, as the Boston Red Sox learned on October 14, 1975, in the bottom of the 10th inning in Game Three of the World Series at Cincinatti. With the score tied, 5–5, Cincinnati center fielder Cesar Geronimo led off with a single. Reds manager Sparky Anderson then sent up Ed Armbrister to pinch-hit for pitcher Rawly Eastwick. While attempting to lay down a sacrifice bunt, Armbrister became entangled with Red Sox catcher Carlton Fisk as Fisk sprang out from behind the plate to field the ball. The two seemed to lock together forever before Armbrister finally broke free to run to first, enabling Fisk to seize the ball and throw it to second baseman Denny Doyle, hoping to get Geronimo.

When Fisk’s throw went into center field, the Reds ended up with runners on second and third, and plate umpire Larry Barnett wound up with Fisk and Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson in his face, howling that Armbrister should be out for interference and Geronimo made to return to first. Barnett insisted the collision did not constitute interference because it had not been intentional, and first-base umpire Dick Stello came to his support even though there was nothing in the rule at the time to stipulate that a batter’s interference must be intentional for it to be deemed an illegal action. A few minutes later the Reds won the game, 6–5, on a single by Joe Morgan.

In the early game there was considerable disagreement over whether a runner should be declared out when he was hit by a batted ball, since it so often was an unavoidable accident. The first effort to address this issue was in 1872, when a rule was created that any player who willfully let a batted or thrown ball hit him was automatically out.

In 1877, the rule was altered so that any baserunner, whether his act was willful or not, was out if he was struck by a batted ball before it had passed a fielder. The revision was necessary when it grew apparent that umpires could not be expected to judge whether a runner had intentionally let a ball hit him. Since an official scorer could not be expected to judge either whether the batted ball would have resulted in a hit or an out if a runner had not interfered with it, the vote was to count any batted ball that struck a runner as a single.

The lone exception to this rule occurs when a runner occupying his base is called out for being hit by a ball that has already been ruled an infield fly and could not possibly dodge it without stepping off his base and risking being doubled off. No official scorer in major-league history has ever been challenged, however, by the following fictious situation:

On the closing day of the season, Mike Stroke of the Hawks trails Bill Clout of the Eagles by one percentage point in the race for the league batting title. As luck would have it, the Hawks and the Eagles face each other in the final game. Clout elects to sit out the contest to protect his slim lead. To further aid his teammate’s bid for the batting crown, the Eagles’ pitcher, John Flame, intentionally walks Stroke each time he comes to bat.

Stroke’s last plate appearance comes with two out in the ninth inning and his team trailing, 6–0. So effective has Flame been to this point against the other eight members of the Hawks’ order that he is working on a no-hitter. The gem in the making of course only provides Flame with all the more incentive to purposely pass the dangerous Stroke for the fourth time in the game.

On his way to first base, Stroke roundly curses Flame, who merely sneers at him. Stroke seemingly is powerless to do anything to gain revenge against Flame and the Eagles for denying him a fair chance to claim the batting crown. But then, suddenly, an opportunity presents itself. Tim Speed, the Hawks’ next batter, slices a sharp groundball toward the second baseman, and Stroke, running to second, makes what appears to be only a token attempt to avoid being hit by it.

Must the official scorer give Speed a hit and deprive Flame of a no-hitter? Rule 6.01 (a) (11) says he does, but happily no major-league official scorer to date has been made to face the unpleasant prospect of ending a no-hit bid on such a rude technicality when no one really can be certain of Stroke’s intent.

However, when a Pacific Coast League game on July 6, 1963, between the Spokane Indians and the Hawaii Islanders (won by Spokane, 18–0) terminated with Islanders pinch-runner Stan Palys being hit by a batted ball with two out in the ninth inning to seemingly end a no-hit bid by Indians hurler Bob Radovich, PCL president Dewey Soriano happened to be in attendance. Soriano immediately contacted the press box and notified them that no base hit was to be awarded and to credit a putout to the first baseman unassisted because Palys was out for “unsportsmanlike play” rather than runner interference. Palys, in Soriano’s judgment, had “danced up and down” in front of Spokane’s first baseman, obviously staging himself to be hit by a grounder toward first rather than allowing the first baseman to make a play.

With base hits becoming more precious with each passing year in today’s climate, would a major-league official ever dare do the same if Palys had been less blatant? Especially if, unlike Soriano, he had not witnessed it for himself? In all honesty, would Soriano have made the same decision if he had not seen the play with his own eyes but only received a report of it?

Note that hindering a fielder does not necessarily have to be a physical action or inaction. It can also be verbal and can come from either the dugout or the playing field. Until the early part of the twentieth century, players in all parks sat on benches only some 15 or 20 yards from the playing field and would often holler “Watch out!” to the opposing player chasing down a foul pop near their bench or “I’ve got it!” when two or more opponents were racing for a short fly ball. Generally umpires, most of the time working alone, would ignore complaints of interference or obstruction if a ball fell safely because of verbal chicanery simply by saying they didn’t hear anything.

But it was a rougher game back then. Today, with every game having at least four umpires, one is almost certain to overhear any effort to convey verbal misinformation (albeit by some accounts Yankees base runner Alex Rodriguez got away with a bit of vocal mischief in a 2007 game against Toronto). Too, players on both teams will anger justifiably at such illegal tactics. What with the salary money at stake, no one wants to instigate an injury on a falsely induced collision involving a fellow player.

Observe that Rule 6.01, for all the contingencies it covers, has no comment on whether it constitutes interference if a runner deliberately kicks the ball out of the fielder’s hand or glove as he is being tagged out on a slide into a base. The key word here is “deliberately.” In 1871, the rule became that when a fielder holding the ball tagged a runner who was off a base, the runner was out even if he somehow knocked the ball out of the fielder’s hand. This rule was rescinded in 1877, but an umpire could still call a runner out for interference if, in his judgment, an intentional effort was made to dislodge the ball from a fielder’s grasp. Without the interference proviso it was felt, rightly, that some runners would stop at nothing to make a fielder drop the ball when a tag play was imminent.

Ty Cobb was notorious for kicking balls out of basemen’s gloves without being called on it, but it was easier in Cobb’s day when infielders wore skimpier gloves with only rudimentary webbing. A more recent miscreant was Eddie Stanky. On October 6, 1951, at the Polo Grounds, in Game Three of the World Series, Stanky fired up millions watching on TV—as well as his New York Giants teammates—with a foot maneuver that, momentarily at least, rattled the seemingly invincible New York Yankees to the core.

In the bottom of the fifth, after Giants pitcher Jim Hearn fanned, Stanky coaxed a walk out of Yankees starter Vic Raschi and then tried to steal second base. Catcher Yogi Berra’s throw beat Stanky to the bag, but Stanky kicked the ball out of shortstop Phil Rizzuto’s glove with a quick flick of his big toe (but again, this was nearly seventy years ago and gloves were still considerably smaller than they are today). When the ball rolled away into the outfield, Stanky took off for third base. Rizzuto was charged with an error on the play rather than registering what should have been the Giants’ second out. Umpire Bill Summers turned a deaf ear to Rizzuto’s shriek that Stanky’s kick constituted interference, nor did he pay any attention to a Yankees protest that Stanky had never touched second base before picking himself up from the ground and darting to third.

Later in the inning, Berra dropped a throw home on what ought to have been the third out, and the Giants then broke the game open by scoring five runs in the frame—all of them unearned. The following morning, a Sunday headline on the New York Times sports page referred to the episode as Stanky’s “Field Goal Kick.” Much was made of how the play had not only shot the Giants to a 2–1 lead in the Series, but had given them all the momentum and left the heavily favored Yankees in disarray.

Unhappily for the Giants, the Yankees got lucky. It rained that Sunday, postponing Game Four at the Polo Grounds and allowing Yankees manager Casey Stengel to send Allie Reynolds to the mound the following afternoon with an extra day’s rest. Reynolds hurled a 6–2 win to even the Series and revive the confidence of his teammates. The Yankees went on to win the world championship, four games to two, making Stanky’s field goal kick no more than a footnote in Series lore.

In a game on May, 25, 2011, at San Francisco’s AT&T Park, Giants catcher Buster Posey sustained a broken left ankle and torn ligaments in a violent home-plate collision when the Florida Marlins’ Scott Cousins crashed into him while trying to score the go-ahead run in the 12th inning on a sacrifice fly. The force of the collision prevented Posey from handling the throw from right fielder Nate Schierholtz, which was on target. The injury truncated Posey’s season to just 45 games. Cousins defended his part in the collision, telling the San Francisco Chronicle it was the only way he could have scored what proved to be the winning run in Florida’s 7–6 triumph. “If I saw a clean lane to slide, that’s the play I’m making,” Cousins added. “I have speed and like to believe I’m going to beat the ball. But there was no chance on that play. It was a game-changing play in extra innings, and I had to play as hard as I could.”

The play was nonetheless reminiscent of Pete Rose’s horrendous crash into Cleveland catcher Ray Fosse during the 1970 All-Star Game that severely curtailed Fosse’s career. Cousins’s critics claimed that he could have avoided the collision by sliding to the third-base line side of the plate and brushing it with his hand. Posey also had his critics who contended he was blocking Cousins’s path to the plate before having the ball in his possession.

In the wake of the Posey-Cousins collision and others like it both before and after 2011, MLB, at long last, laggardly adopted new rules regarding plate collisions—but not until nearly three years later, scarcely in time for them to go into effect for the 2014 season. The rules implemented then, under Rule 7.13, are essentially the same as those in Rule 6.01 (i).

Rule 6.01 (i) has been enormously expanded from the previous rules addressing collisions at home plate. While the Posey-Cousins confrontation was catalytic in tardily bringing about a new set of rules governing plays at the plate, there were numerous collisions in the 40 some years since the Rose-Fosse episode between catchers and baserunners that were just as violent and some even worse. In 1987, Royals outfielder Bo Jackson, better known for his football exploits, broke Cleveland catcher Rick Dempsey’s thumb as he plowed into him. Five years later, Astros third baseman Ken Caminiti KO’d Atlanta catcher Greg Olson in a plate collision, sending him to the hospital.

Given the many examples of vicious collisions from recent times, imagine what the catcher-runner battles must have been like in the rough-and-tumble years prior to the arrival of Babe Ruth and the Liveball Era. Rather amazingly, they were few and far between. Early day catchers, for one, were in general a bigger and hardier breed than other position players, let alone pitchers, and used to not only use their bodies but even the ball itself as a weapon to deter overly ambitious runners. Too, they wore masks and chest protectors and eventually shin guards, whereas runners came armed with only their spikes. Players like Ty Cobb changed all that to a degree, but even Cobb spent considerable time on the disabled list owing to base running mishaps and unnecessarily hard tags.

Lest the reader think that Rule 6.01 (i) (1) or (2) has eliminated or even thoroughly clarified illegal contact between catchers and baserunners, incidents that could be judged to constitute rule violations but do not still occur, while incidents deemed rule violations are perfectly legal. One of the former that received special attention came at Wrigley Field on June 19, 2017, in the bottom of the sixth inning of a game between the Padres and Cubs. Anthony Rizzo led off the frame by tripling. After second baseman Ian Happ fanned, third baseman Kris Bryant flied out to center fielder Matt Szczur. Rizzo tagged at third base and raced for home as soon as the catch was made. His trip began on the foul side of the third-base line, but when he saw Szczur’s throw would reach San Diego catcher Austin Hedges ahead of him, he swerved into fair territory and came at Hedges’s knees and elbows first without making any effort to touch the plate. Hedges held on to the ball but was forced to leave the game afterward. Rizzo was merely chided in the press for actively seeking out the collision and wrongly defended by his manager Joe Maddon, who said, “The catcher is in the way. You don’t try to avoid him in an effort to score and hurt yourself. You hit him, just like Riz did.”

This rule and many of its ramifications followed one of the most iniquitous base-running incidents in history and, in the absence of it, its perpetrator almost inconceivably went unpunished. In Game Two of the National League Division Series on October 10, 2015, at Dodger Stadium between the Dodgers and the New York Mets, the home team trailed, 2–1. In their half of the seventh inning with one out, the Dodgers had Enrique Hernandez on third and Chase Utley on first when Howie Kendrick came to bat. Kendrick rapped a sharp grounder to Mets second baseman Daniel Murphy, who tossed the ball to shortstop Ruben Tejada to start a potential double play. Utley slid far to the right side of second base, missing it altogether and colliding with Tejada’s leg as he was turning to make a throw to first. Tejada was flipped by the contact and was carried off the field with a fractured right fibula—but not before Utley was called out at second and trotted off the field, having never touched the bag. Since it appeared to Dodgers manager Don Mattingly that Tejada dragged his foot near second base but hadn’t actually touched it, he requested a video review. When the force out call at second was overturned, Utley trotted back out to the base. After Mets skipper Terry Collins pointed out that Utley had never touched second before leaving the field, he was in effect grudgingly told that since second-base umpire Chris Guccione blew the call, Utley had no need to tag the bag before his departure.

The Mets lost the game, 5–2, but still won the series, three games to two. Utley was initially suspended for two games but fought it and ultimately had it erased. However, in February 2016 MLB and the Players Association agreed that “slides on potential double plays will require runners will make a bona fide attempt to reach and remain on the base. Runners may still initiate contact with a fielder as a consequence of an otherwise permissible slide. A runner will be specifically prohibited from changing his pathway to the base or utilizing a ‘roll block’ for the purpose of initiating contact with the fielder.” Utley finished his 16th consecutive season in the majors in 2018 before retiring. Tejada was never again more than a part-time major leaguer and has spent most of his time since 2015 in the minors.

Following the rule change as a direct result the Utley incident, coincidentally a ticky-tack game-ending example of the current version of runner interference occurred on June 17, 2016, at the Mets’ Citi Field in Queens, New York. Trailing the Atlanta Braves in the bottom of the ninth, 5–1, Mets first baseman James Loney walked with one out. The next batter, catcher Kevin Plawecki, hit a ground ball to Braves shortstop Erick Aybar who tried for two by firing the ball to second baseman Jace Peterson to retire Loney. But Peterson’s throw to first baseman Freddie Freeman was not in time to catch Plawecki. However, second-base umpire Mark Wegner immediately flashed the sign that Loney’s slide into second had interfered with Peterson’s effort to turn two, bringing the game to abrupt halt.

Loney’s slide was nowhere near being in the Utley category—he brushed Peterson with an elbow as he slid into second—but the contact, slight as it was, clearly impinged on Peterson’s throw to first in Wegner’s judment, which is the key criterion on a current interference call of this nature.

Prior to the 2013 season, a pitcher was permitted to feint toward third (or second) base, and then turn and throw or feint a throw to first base if his pivot foot disengaged the rubber after his initial feint. This was called the “fake to third, throw to first” play and over the years caught many an unwary runner. Abolishing this bit of trickery made runners look less foolish, but also deprived spectators of witnessing an age-old gambit that many are still unaware is now illegal.

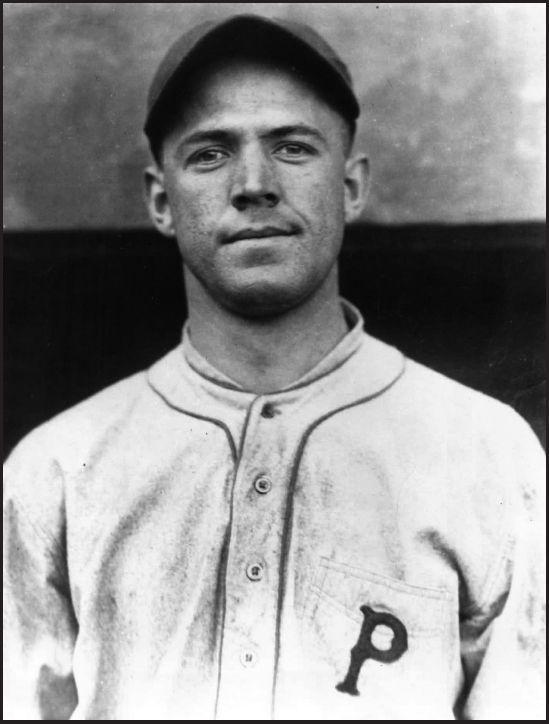

Before the spitball was outlawed in 1920, a pitcher was free to bring his pitching hand in contact with his mouth anywhere on the diamond. He could even bring the ball in contact with his mouth for a while the Pittsburgh Pirates had a pitcher, Marty O’Toole, who loaded up for a spitter by licking the ball with his tongue. O’Toole’s only season of note was 1912, when he won 15 games. There is a tale that the reason he went into a tailspin after 1912 came in one of his outings that season in an early July game against the Phillies when Phils first sacker Fred Luderus found an insidious way to emasculate his spitter. Luderus purportedly harbored a tube of liniment in his pants pocket and applied a dab of it each time the ball came into his hands. Balls in 1912 often lasted several innings and sometimes even an entire game. By the third inning O’Toole’s tongue was so raw he had to be removed from the mound. Pittsburgh manager Fred Clarke, aware of what Luderus was doing, protested. But it went nowhere when Phils skipper Red Dooin pointed out that there was nothing in the rules to prevent it and, furthermore, Luderus was only trying to protect the health of his teammates who would otherwise be exposed to millions of germs. The problem with the tale is that the game in question, on July 9, was won by O’Toole, 2–0. Historian Dick Thompson postulated that the true reason for O’Toole’s abrupt decline was overwork and never really learning to control his spitter, allowing batters to lay off it once they realized this.

Regardless, the proviso making it illegal for a pitcher to bring his pitching hand in contact with his mouth or lips was not added to the anti-spitball rule until 1968. There was a massive effort at the time to rid the game of the spitter after the majors were given little choice but to acknowledge that many pitchers were using it. The estimates ran as high as 50 or 60, an average of about three pitchers on a team. One hurler, Cal Koonce of the New York Mets, in an inconceivable moment of candor, admitted in a piece that appeared in the September 2, 1967, issue of The Sporting News that the spitter was an important weapon in his arsenal. Subsequently asked if he had really made such an admission, Koonce said, “I don’t know what all the fuss is about. A lot of pitchers in the [National] league throw the spitter and everyone knows who they are.”

It seems unbelievable, in any case, that for forty-eight years after the spitball was outlawed the Official Playing Rules Committee failed to stipulate that a pitcher could not spit on his pitching hand. Since 1968, the rule has been amended to allow a pitcher to go to his mouth if he is not on the mound.

When the spitball was banned, the majors introduced a corollary rule that any player who intentionally discolored or defaced a ball would be kicked out of the game and the ball removed from play. If the umpires were unable to detect a transgressor, then the pitcher would be ejected as soon as the ball was in his possession and socked in addition with a 10-day suspension.

For obvious reasons, this rule didn’t fly and was subsequently redrafted so that it was not all bark and no bite. Realizing they were verging on overreacting to the spitball specter and the concomitant bad press that followed Ray Chapman’s beaning death, major-league tsars privately tempered their stance, even as they continued to rail publicly against pitchers who loaded up the ball. After a livelier type of horsehide was slipped into play during the early 1920s, no one wanted to punish hurlers any more than they were already having to suffer as they watched their ERAs mount alarmingly. In 1922, George Uhle of Cleveland became the first moundsman since the 1890s to win 20 games with an ERA over 4.00. Eight years later Pittsburgh’s Ray Kremer became the first pitcher ever to collect 20 wins with an ERA over 5.00 (5.02). In 1938, Bobo Newsom topped Kremer’s negative mark with he won 20 for the St. Louis Browns with a 5.08 ERA.

The last time a pitcher threw a spitball in a major-league game without facing the possibility of being penalized for it was in 1934, when Burleigh Grimes was in his final season in the majors. Grimes was the last to remain active of the 17 hurlers who had been given special dispensation in 1920 to continue throwing spitters in the majors until their careers were over. When Grimes notched his 270th and final win on May 30, 1934, by beating the Washington Senators, 5–4 in a relief role for the New York Yankees, it was the last victory by a hurler legally permitted to throw a spitter.

Burleigh Grimes legally threw a spitball pitch in the major leagues for a record nineteen seasons.

For some twenty-four years after the anti-spitball edict was enacted, no pitcher was ejected from a game specifically for violating the rule. Finally, on July 20, 1944, in a Thursday night game at St. Louis against the New York Yankees, Nels Potter of the Browns was tossed out by home-plate umpire Cal Hubbard in the fifth inning with New York’s Don Savage at the plate. Nearly a quarter century after the anti-spitball rule went into effect, Potter became its first victim when Hubbard tired of watching him blow on the ball in such a way that it looked like he was spitting on it. Potter insisted he was doing nothing wrong and got huffy with Hubbard. His defiance helped convict him, for it was never proven that he was spraying saliva on the ball when he blew on it. The game, which St. Louis won, 7–3, was nearly forfeited to New York when Brownie fans rained the field with bottles for some 15 minutes after Potter’s ejection was announced.

A few years before the Potter incident, the Yankees were certain that Tommy Bridges of the Detroit Tigers was shutting them down with a spitter. When Yankees skipper Joe McCarthy finally induced umpire Bill McGowan to take a look at the ball, Tigers catcher Mickey Cochrane dropped it as he handed it to McGowan and then rolled it in the dirt down the third-base line when he went to pick it up. Variations of Cochrane’s stratagem have been used time and again ever since 1920 by catchers and infielders when an arbiter has asked to examine a suspicious ball.

Though Rule 6.02 (c) (7) does not so specify, it is also illegal for a pitcher to have on his person a jagged fingernail that he can use to nick the surface of a ball. But fingernails are not nearly as much of a worry to umpires as other devices that are at once more disruptive and harder to detect. On August 3, 1987, at a game in Anaheim, Joe Niekro—then with the Minnesota Twins—was caught red-handed with both an emery board and a strip of sandpaper in his hip pocket with one out in the bottom of the fourth inning with the score tied, 2–2, when plate umpire Tim Tschida confronted him on the mound. Niekro was suspended for 10 days, but few pitchers have made it so easy for officials to ferret out their methods for doctoring balls. When asked to empty his pockets, Niekro clumsy tried to throw the emery board away, but it landed nearly at his feet.

During a game at Baltimore’s Camden Yards on June 21, 1992, Orioles manager Johnny Oates complained that New York Yankees pitcher Tim Leary was putting “sandpaper scratches” on the ball. The umpires checked Leary’s glove and hand and found nothing, but TV cameras earlier showed Leary putting his mouth to his glove and later spitting something out of his mouth when he reached the Yankees dugout at the end of the inning. Asked later why he only inspected Leary’s hand and glove, first-base umpire Dave Phillips said, “I don’t want to put my hand into somebody’s mouth.”

When Steve Carlton was in his prime, sportswriters were quite willing to respect his desire not to give interviews. The loss to their readers was small, they felt. Carlton wasn’t very interesting anyway. What was fascinating, though, was how he got away year after year with cutting the ball. No one ever figured out the instrument Carlton used, and he was scarcely about to break his code of silence to convict himself.

But if Leary’s and Carlton’s techniques for defacing a ball were too subtle to allow an umpire in indict them, Los Angeles Dodgers’ hurler Don Sutton was not so fortunate. Pitching against the St. Louis Cardinals at Busch Stadium II on July 14, 1978, Sutton was given the heave in the bottom of the seventh inning by umpire Doug Harvey after he scrupulously collected three balls that had become mysteriously scuffed while in Sutton’s hands. Even though Harvey could not determine how Sutton was doctoring the balls, he defended his ejection by saying, “I represent the integrity of the game and I’m going to continue to do it if necessary.” Sutton responded by suing Harvey for jeopardizing his livelihood. The threat worked. Sutton received only a warning for the incident—never even a fine, let alone a suspension.

The starting points for an umpire who has to decide whether a pitcher is deliberately throwing at a batter are the pitcher’s history, prior events in the game, and his own intuition. Whether or not the pitcher hits a batter is often irrelevant. In a game on May 1, 1974, at Three Rivers Stadium against the Cincinnati Reds, Dock Ellis of the Pirates hit the first three batters he faced in the game—Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, and Dan Driessen—and then threw four fastballs high and tight to cleanup hitter Tony Perez to force in a run. When Ellis nearly nailed Johnny Bench with his next two pitches, still no one thought there was malice aforethought in his wild steak. After all, Ellis had tossed a no-hitter four years earlier and claimed afterward that he did it while on LSD. Finally, though, Pirates manager Danny Murtaugh lifted Ellis before anyone was killed. Said Reds manager Sparky Anderson when asked later for his views on Ellis’s performance: “No one would be crazy enough to deliberately hit the first three men. He was so wild he just didn’t know where the ball was going.” Later it emerged that several days before the game Ellis had purportedly boasted he would throw at everyone in sight once he took the mound.

In contrast, Texas Rangers reliever Bob Babcock was booted from a game against the California Angels on May 26, 1980, at Anaheim Stadium after just one pitch—his first pitch of the season no less! Babcock entered the fray in the top of the seventh inning following a beanball war during the previous frame that had culminated in a benches-clearing brawl after Rangers third baseman Buddy Bell was tossed for charging the Angels’ Bruce Kison on the mound. As a consequence, the umpires were especially vigilant. When Babcock’s first delivery narrowly missed Dan Ford, leading off the inning for the Angels, all four men in blue were convinced he was headhunting on orders from Rangers manager Pat Corrales. Babcock tried to claim his foot had slipped off the rubber as he released the pitch, but no one was about to buy it. He was thumbed from the game by plate umpire Bill Haller almost as soon as the ball whizzed past Ford’s head. The following inning Rangers pinch-hitter Johnny Grubb was hit by a pitch and he and Kison were both tossed when he too charged the mound. The game then fell into the hands of reliever Mark Clear and the Angels lost, 6–5, when their defense unraveled.

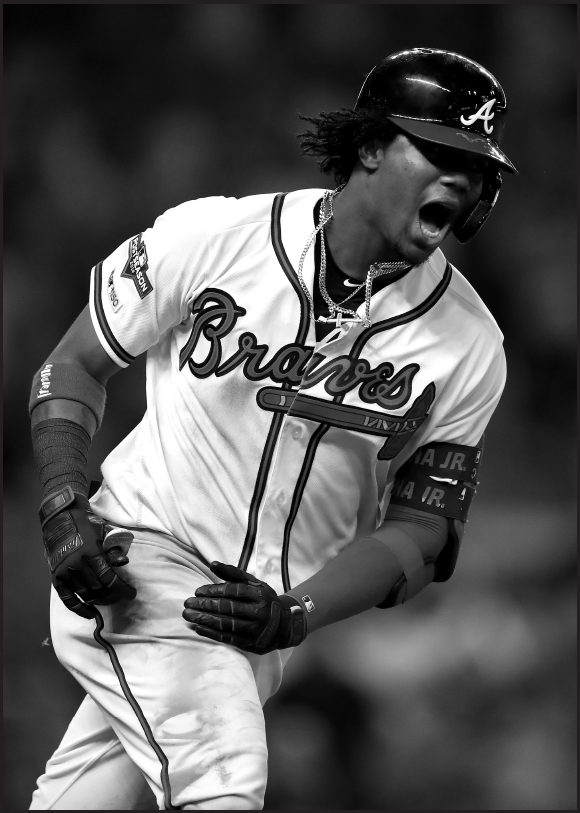

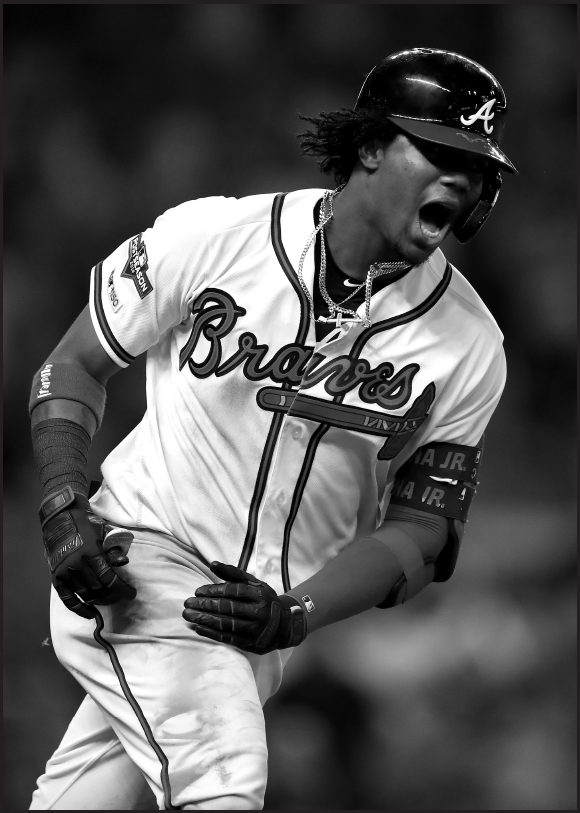

Babcock is not the only major-league hurler to be ejected after just one pitch. An even more notorious episode arose in a game at Atlanta’s Sun Trust Park on August 15, 2018, when Miami starter Jose Urena drilled the Braves’ rookie leadoff hitter Ronald Acuna Jr. in the left elbow area with his first pitch of the night in the bottom of the first inning. Acuna had entered the game having homered in a rookie-record five straight games, three of them against the Marlins. At first the umpires seemed inclined to treat Urena’s pitch as simply an errant one. But when Acuna veered off toward the mound as he was starting to take his base and threw off the wrap he wore around his swollen elbow, Braves manager Brian Snitker led the charge out of the Atlanta dugout.

Braves outfielder Ronald Acuna Jr. set a frosh record in 2018 when he homered in five straight games. He conquered the sophomore jinx in 2019 by leading the National League in runs and stolen bases along with belting 41 homers, many of them as the Braves’ leadoff hitter.

That quickly, the event disintegrated into a benches-clearing scuffle with both Urena and Snitker ejected from the game after the umpires huddled around crew chief Paul Nauert. The end result was that stiff warnings were issued to both teams, Atlanta won the game, 5–2, Urena escaped a suspension largely because he carried a reputation for wildness—the 2018 season marked his second in a row leading the National League in hit batsmen—and Acuna’s home-run streak remained intact because he was hit by a pitch in his lone plate appearance. His streak ended the following night, however, in an 11–5 loss to Colorado.

In sandlot games, an argument often arises if a batter switches from batting righ handed to hitting lefty or vice versa when an opposing team has not changed pitchers while he is batting. As Rule 6.06 (b) reads, however, a batter is free to switch to the opposite side of the plate after every pitch. Before 1907, a batter could switch sides even while a pitcher was in the midst of his delivery. Since then the rule has been that if the batter is in the batter’s box and the pitcher is in position to deliver the ball, the batter cannot switch unless time is called by the umpire, allowing him to step out of the box and make the change.

Rule 6.03 (a) 2 makes an attempt by a batter to switch sides while time is in cause for an umpire to declare him out for an illegal action. In the early game it was not uncommon for batters, particularly foxy switch-hitters like Tommy Tucker, to do just that without penalty. One of the first victims of this rule (formerly 6.06 [b]) was Philadelphia Phillies outfielder and leadoff hitter Johnny Bates. In a game against the Cincinnati Reds at the Reds’ Palace of the Fans on August 27, 1910, Bates, a left-handed hitter, was called out by home-plate umpire Mal Eason when he changed to the right side of the plate while Reds pitcher Fred Beebe was in motion. Bates nonetheless went 1-for-3 that day and scored a run in the Phils’ 5–2 win.

Prior to the rule generated by Pat Venditte’s recent arrival in the game, the problem became more complex for an umpire, however, when a switch-hitter faced a switch-pitcher. In a Western Association game in 1928, Paul Richards of Muskogee (the same Paul Richards who would later exasperate umpires with his ingenious tests of the rules as a major-league manager) baffled Topeka hitters by throwing left handed to lefty hitters and right-handed to righty hitters until switch-hitter Charlie “Swamp Baby” Wilson came up in the ninth inning as a pinch-hitter. Each time Richards changed his glove from one hand to the other Wilson matched him by moving to the opposite side of the plate. Said Richards in recalling the incident: “Finally I threw my glove down on the ground, faced him square with both feet on the rubber, put my hands behind my back and let him choose his own poison.” In recounting the story, Richards would always end by slyly confessing he walked Wilson on a 3-and-2 count when he missed the plate with a slow left-handed curve.

This rule was first inserted in 1975. Before then, if a batter was discovered to have struck a ball with a “loaded” or doctored bat, the hit counted and the offending bat was simply removed from the game (although the batter could be subject to further sanctions if it was a repeat violation or a particularly flagrant one). The procedure, if a bat was protested, was for the umpires to inspect it and then either allow it to continue in play or confiscate it for a more thorough examination if it looked suspicious.

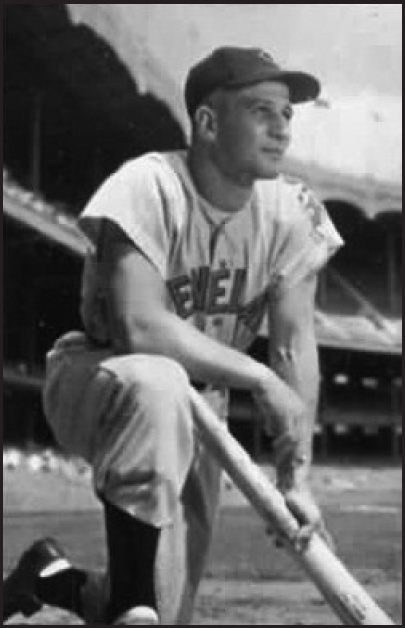

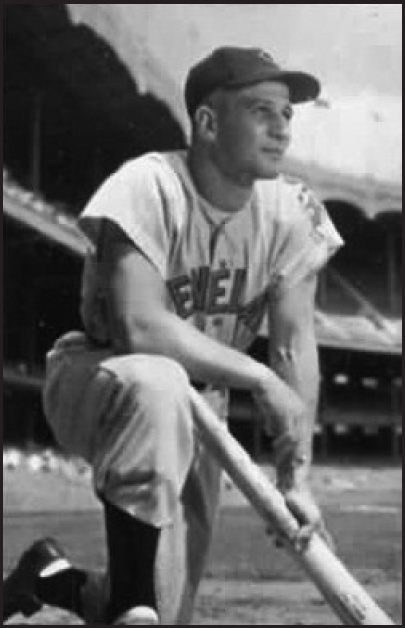

Loaded bats have been part of the game almost from its inception. Players in the nineteenth century would often pound nails into the meat ends of their bats and then coat the nail heads with varnish or some other substance that would conceal them from chary opponents. A much more recent incident occurred in 1954 when Cleveland third baseman Al Rosen was found to be using a bat studded with nails after slugging three home runs in a two-game set with the Boston Red Sox on May 18–19. At the time, Rosen was hitting .382 with nine homers and 38 RBIs in just 30 games, and coming off a season in which he had paced the American League in every important slugging department and almost won the Triple Crown. Soon after being deprived of his “magic” bat, Rosen suffered a broken finger. The dual setback caused a dramatic decline in his production. For the remaining 124 games of the 1954 campaign, Rosen hit well below .300 and notched just 15 home runs and 64 RBIs. The sharp drop, even though some of it was definitely attributable to Rosen’s injury, fostered speculation that he may have been using a loaded bat for some time before he was caught.

Caught using a bat studded with nails in 1954, Cleveland third baseman Al Rosen sustained a badly broken finger shortly thereafter. The finger injury is thought to have stopped him from ever again being the great slugger he had formerly been, but it will never be certain whether he used the illegal bat in his MVP season in 1953.

Forty years later, another Cleveland slugger, outfielder Albert Belle, was suspended for 10 games after the corked bat he used in a game on July 15, 1994, was finally confiscated after a byzantine chase by umpires to recapture it following its theft from the umpires’ dressing room. But no bat violation was more embarrassing to its culprit than the one seen by a national TV audience on June 3, 2003, in an interleague game at Wrigley Field between the Cubs and the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. In the bottom of the first inning, Cubs outfielder Sammy Sosa came to the plate with two on and one out against Tampa’s Geremi Gonzalez. When Sosa grounded out to second base, his bat broke. He was immediately ejected from the game after plate umpire Tim McClelland examined it and found it was heavily corked. Sosa contended the bat had slipped into the game by accident and was used only in batting practice to entertain fans but was nonetheless suspended for seven games.

Probably the most bizarre loaded bat incident in the last half century came on September 7, 1974, at Shea Stadium while the Yankees were using it as a temporary home during a time when their own stadium was being renovated. In the second game of a doubleheader with Detroit, New York third baseman Graig Nettles broke his bat after lining a fastball from Woodie Fryman to left field in the bottom of the fifth . . . and six superballs tumbled out of the barrel. Nettles was declared automatically out, with the out credited to Tigers catcher Bill Freehan, but was not ejected from the game by plate umpire Lou DiMuro even though three innings earlier he had homered for the game’s only run, in all likelihood with the same bat. He was subsequently suspended for 10 games, however, by American League president Lee MacPhail who did not buy his excuse that the bat had been given to him by an admiring fan and he was unaware of its illicit contents. Rules authorities believe the Nettles incident more than any other prompted the creation of Rule 6.03 (a) (5).

Although the question is not specifically addressed in this rule, the absence of any proscription to the contrary licenses a vigilant fan to lean over the railing behind his favorite team’s dugout and whisper to the manager that an opposition hitter is batting out of turn. Indeed, the only people in a ballpark who are forbidden by rule to call such a violation to a manager’s attention are the official scorer and the umpiring crew. An umpire in particular is required to keep still, which is not to say that all arbiters know or abide by this rule. In her book, You’ve Got to Have B*lls to Make It in This League, Pam Postema recalled the following moment in a minor league game she was officiating:

Once in a while I even showed up a manager or one of my own partners. For instance, one night I had the plate and noticed a batter step into the box who wasn’t supposed to be there. He was batting out of order. Stupid rookie. Just as I was getting ready to call the batter out for hitting out of order, I heard the scorekeeper yell down to her husband, who happened to be one of the managers, “Woody, that’s the wrong batter, honey,” she said.

Too late, I called the guy out and quickly figured out who was supposed to be up next. Meanwhile, my partner, who didn’t have a clue what the rule said, whispered, “Are you sure you’re right?” Hey, it was no big deal to me. I knew the rule. I called it. End of discussion.

Postema’s recollection makes it distressingly apparent that neither she nor her partner nor the official scorer nor the official scorer’s manager-husband knew the present-day rule on a player batting out of order.

However, the rule in 1912 was a bit different. It was not left solely to the opposing team’s manager to inform an umpire that a player had batted out of order.

Dick Cotter, a backup catcher in the NL for two seasons, is listed in all reference works today as having played his last major-league game on September 26, 1912. In actuality, he played his last game six days later on October 2 and emerged as its hero, but it didn’t count. None of it counted because the custom during the 1910s dictated that all statistics from protested games that were thrown out were permanently eradicated. And who was responsible for the game being protested? Not Pittsburgh, the losing team, though technically its secretary officially lodged the protest but only after a writer at the game brought it to his attention long after both teams had left the field that he had grounds for a protest. That nameless writer, it need be said, along with several other scribes at the game, had made frantic efforts from the press box “to put the home team next to the mistake before it was too late.”

The muddle began in the bottom of the ninth when Cotter, a right-handed hitter, pinch-hit for Wilbur Good, a left-handed hitter who had been sent up to bat for Cubs pitcher Jimmy Lavender and was called back when the Pirates replaced right-hander Howie Camnitz on the hill with southpaw Hank Robinson. Cotter ripped a single over first base that brought home Cubs outfielder Cy Williams with the run that tied the game, 5–5. Cotter then stayed in the contest, replacing catcher Jimmy Archer who had been pinch run for by Williams, while Charlie Smith replaced Lavender on the hill. After Smith held Pittsburgh scoreless in the visitors’ half of the 10th frame, Chicago threatened in the home half, bringing Cotter to the plate with two out and a chance to drive in the winning run. Only Cotter this time was batting not in the ninth spot in the order, which Lavender had occupied, but the eighth spot, which had belonged to Archer. With two out and Vic Saier on second and Frank Schulte on third, Cotter lined a single over second base off Robinson to plate Schulte with the walk-off winning run—at least insofar as everyone connected with the Pittsburgh and Chicago clubs then believed.

Meanwhile, umpires Brick Owens and Bill Brennan had been aware that Cotter had batted out of turn when he hit in the eighth spot instead of the ninth, the spot he’d occupied when he entered the game, but looked the other way because they “thought it was up to the opposing team to claim the point, so did not declare Dick out.” The New York Sun said both officials “waited for manager [Fred] Clarke to lodge a protest, but none was forth coming, and Owens, the-umpire-in-chief that day, declared that no further protests could be made, that the chance was lost when the Pirates rushed from the field.” They learned otherwise before the evening was out when soon after they wired the protest on Pittsburgh’s behalf to NL president Tom Lynch, Lynch read them the riot act.

Since the Giants had already clinched the NL pennant—ironically on the day that Dick Cotter played his final official ML game—the protested contest was not replayed because it meant nothing.

Except to Dick Cotter.

Observe that this rule is a comparatively recent revision of the old rule that allowed a team manager to wait after noticing a batter has batted out of turn until the batting snafu produces a positive result for the offending team. Here is the old rule in action.

On August 2, 1923, in the first game of a doubleheader at Washington, St. Louis Browns skipper Lee Fohl, a compulsive batting order juggler, had not just two but four players batting out of order—outfielders Ken Williams and Baby Doll Jacobson, plus shortstop Wally Gerber and catcher Hank Severeid. The Williams-Jacobson mistake was rectified in the top of the first inning when Williams, who was listed in the fourth spot, batted third and walked, a positive result. Washington skipper Donie Bush protested immediately and Jacobson, who should have been hitting ahead of Williams, was declared out and Williams made to bat again. Even though Bush also noticed early in the game that Gerber and Severeid had switched positions in the batting order, he held his powder for their first three trips through the order because neither of them did anything positive. But in the ninth inning, when Gerber singled a runner to third with two out, Bush spoke up that Gerber was batting in Severeid’s sixth spot in the order. His timing was impeccable. Plate umpire Red Ormsby ruled Severeid out to end the game and effectively erase Gerber’s lone hit on the day.

Personally, this author prefers the old rule. Anything that requires a manager to strategize on the fly as the game progresses I’m for.

During one of his at-bats against the New York Giants at Braves Field on August 9, 1950, Boston third baseman Bob Elliott requested that umpire Augie Donetelli shift his positioning slightly—Donatelli, the roving umpire on a three-man crew, was in Elliott’s line of vision, making it difficult for him to pick up the baseball. When Donatelli complied, Giants second baseman Eddie Stanky saw his chance to further rattle Elliott. Before the next pitch, he sidled over to where Donatelli had been standing and began doing jumping jacks.

Elliott pretended not to see Stanky’s antics, and the game proceeded without incident. On August 11, against the Phillies at Shibe Park, Stanky decided to see if his new “calisthenics” routine could rile Philadelphia’s hotheaded catcher Andy Seminick. This time Stanky evoked the reaction he was aiming for—Seminick stepped out of the batter’s box and demanded that home plate umpire Al Barlick make Stanky cease his antics. Barlick conferred with his three fellow umpires, one of them Donatelli, and Donatelli informed his crew that they had a problem. He had seen Stanky perform this same stunt just two days earlier and consulted the rule book after the game. Therein he discovered that Major League Baseball had lasted for nearly seventy years without ever having cause to outlaw jumping up and down in a batter’s line of vision. Hence Barlick had no choice but to allow Stanky to continue for the rest of the game and then contact National League President Ford Frick afterward in an effort to get some clarification.

Failing to locate Frick prior to the next afternoon’s game, the umpiring crew went to Stanky’s manager, Leo Durocher, and requested that he tell Stanky to drop his jumping jacks act until an official ruling could be made. But Durocher, who had once said there was nothing Stanky could do well on the ball field except beat you, instructed Stanky to continue doing as he pleased. When Stanky did so and added waving his arms exaggeratedly that afternoon, tempers flared. In the second inning, Seminick broke Giants third baseman Hank Thompson’s jaw with his elbow on a hard slide into third. By the fourth inning, second-base umpire Lon Warneke felt he was left with no choice but to eject Stanky when he again waved his arms with Seminick at bat, but it was too little too late. In sliding into second base later in the inning, Seminick took out Stanky’s replacement, Bill Rigney, and detonated a benches-clearing brawl that took the NYPD’s help to subdue it and Warneke having to eject both Rigney and Seminick. After the game, Frick was finally heard from. He instructed all his umpires in the future to eject fielders for “antics on the field designed or intended to annoy or disturb the opposing batsman.” Though the language has changed and expanded, the rule has remained on the books ever since. A form of it actually first appeared in 1931 and may have been what Frick finally stumbled on when he was pushed for help by his umpires.

On numerous occasions, an umpire has invoked the ultimate power bestowed on him in Rule 6.04 (e) (4.08) and expelled every player on a team’s bench from a game. One of the most volatile incidents occurred on September 27, 1951, in a game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves at Braves Field which resulted in the only ejection of a player who never participated in a major league game. Trying to hold a slim first-place lead over the onrushing New York Giants, the Dodgers were tied, 3–3, with Boston in the bottom of the eighth when Jackie Robinson speared a groundball and fired it home to catcher Roy Campanella seemingly in time to nail Bob Addis trying to score from third . . . but plate umpire Frank Dascoli called Addis safe. Campanella was swiftly dispatched for arguing, coach Cookie Lavagetto soon followed when the debate continued to rage, and finally Dascoli cleared the entire Dodgers bench.

Among the record 15 players who were banished was outfielder Bill Sharman, just up from the Dodgers’ Forth Worth farm club in the Texas League after the club had finished its season. Sharman failed to get into a game with Brooklyn in 1951, however, and then quit baseball after one more season in the minors to pursue an NBA career. After joining Bob Cousy, Bill Russell, and Sam Jones to play on several championship Boston Celtics teams, Sharman eventually made the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, but he never had the thrill of seeing his name in a major-league box score, even though it once appeared in an umpire’s report on players who were booted from the game.