CHAPTER ONE

Why Do People Cooperate?

A cross the social sciences there has been a widespread recognition that it is important to understand how to motivate cooperation on the part of people within group settings. This is the case irrespective of whether those settings are small groups, organizations, communities, or societies.1 Studies in management show that work organizations benefit when their members actively work for company success. Law research shows that crime and problems of community disorder are difficult to solve without the active involvement of community residents. Political scientists recognize the importance of public involvement in building both viable communities and strong societies. And those in public policy have identified the value of cooperation in the process of policy making—for example, in stakeholder policy making groups.

Understanding why people are motivated to cooperate when they are within these group settings is a long-term focus of social psychological research. In particular, social psychologists are interested in identifying the motivations that are the antecedents of voluntary cooperation. The goal of this volume is to examine the psychology of cooperation, exploring the motivations that shape the degree to which people cooperate with others. In particular, this analysis focuses on the factors that influence voluntary cooperation. A better understanding of why people cooperate is essential if social psychology is to be helpful in addressing the question of how to motivate cooperation in social settings.

Cooperation in the Real World

The issue of cooperation is central to many of the problems faced by real-world groups, organizations, and societies (De Cremer, Zeelenberg, and Murnighan 2010; Van Lange 2006; VanVugt et al. 2000). As a result, the fields of management, law, and political science all seek to understand how to most effectively design institutions that can best secure cooperation from those within groups. Their efforts to address these issues are mainly informed by the findings of social psychological and economic research on dyads and small groups.

Work organizations encourage positive forms of cooperation, like working hard at one’s job and contributing extra-role and creative efforts to one’s work performance (Tyler and Blader 2000). They also seek to prevent personally rewarding, but destructive, acts such as sabotage and the stealing of office supplies by encouraging deference to rules and policies. For these reasons a central area of research in organizational behavior involves understanding how to motivate cooperation in work settings (Frey and Osterloh 2002).2 Management is the study of motivation in work organizations.

Law is concerned with how to effectively shape behavior so as to prevent people from engaging in actions that are personally rewarding but damaging to others and to the group—actions ranging from illegally copying music and movies to robbing banks (Tyler 2006a; Tyler and Huo 2002). In addition, the police and courts need the active cooperation of members of the community to control crime and urban disorder by reporting crimes and cooperating in policing neighborhoods (Tyler and Huo 2002). And, of course, it is important that people generally support the government through actions such as the paying of taxes (Braithwaite 2003; Feld and Frey 2007). Hence, an important aspect of the study of law involves seeking to understand the factors shaping cooperation with law and legal authorities. Regulation explores how the law can shape the behavior of people in different communities.

Those who hold political office want people to cooperate by participating in personally costly acts ranging from paying taxes to fighting in wars (Levi 1988, 1997). Further, it is equally important for people to actively participate in society in ways that are not required, such as by voting, by maintaining their communities through working together to deal with community problems, and by otherwise helping the polity to thrive (Putnam 2000). For these reasons, understanding how to motivate cooperation is central to political scientists, leading to an interest in exploring why people do or do not have trust and confidence in the government (Levi and Stoker 2000). Governance involves the study of how to motivate desired political behaviors.

One aspect of governance involves studies of public policy, which are concerned with developing social policies that can effectively coordinate the actions of people within communities.3 Such efforts focus on creating a procedure for developing and implementing policies and policy decisions, be they decisions about whether to go to war or where to site a nuclear power plant. The key to success in such efforts is to create policies that all of the people within a community are motivated to accept—that is, to be able to gain widespread rule adherence (Grimes 2006). And, as is true in the other arenas outlined, the value of cooperation in general is widely recognized. In particular, it is important that people not just do what is required. Many aspects of involvement in a community are voluntary, and it is especially important to motivate community residents to engage in voluntary acts such as voting and participating in community problem solving over issues such as environmental use (May 2005).

In a broader arena, regulation and governance involve international relations, questions of compliance with laws, and political relations among states (Simmons 1998). The question of what motivates states to follow international norms, rules, and commitments has been a long-standing concern of international relations (Hurd 1999). It is an issue that is of increasing centrality as the dynamics among states, multinational organizations, and nongovernmental organizations becomes more complex (Reus-Smit 1999). And underlying all of these forms of cooperation is the ability to motivate mass publics whose behavior plays a key role in the stability and viability of societies to both follow laws and accept agreements. Over the past decade, all of these issues have taken on a new urgency as terrorism has made clear the tremendous difficulties that the lack of public cooperation in the form of organized opposition across national borders can pose to institutional actors in the international arena.

The first goal of this volume is to test the range and robustness of one type of motivation—social motivation—in these types of settings. This volume does so by systematically exploring the importance of two aspects of social motivation: organizational policies and practices (procedural justice, motive-based trust) and dispositions (attitudes, values, identity). The importance of these motivations is compared to that of instrumental motivations involving the use of incentives and sanctions.

What perspective is advanced in this volume? The findings herein will show that people are motivated by a broader range of goals than is easily explained via material self-interest—that is, by people’s concerns about incentives and sanctions. Across the five areas examined, social motivations are consistently found to explain significant amounts of variance that are not explained by instrumental factors. This suggests that broadening the motivational framework within which cooperation is understood will help to better explain how to motivate cooperation.

In fact, the results of this volume go further than simply arguing that social motivations have value. They suggest that cooperative behavior, especially voluntary cooperation, is better explained by such social motivations than it is by the traditionally studied impact of instrumental variables such as incentives and sanctions. When the magnitude of the influence of instrumental and social motivations is directly compared, social motivations are found to explain more of the variance in cooperation than can be explained by instrumental motivations. As a consequence, those seeking to best understand how to motivate cooperation should focus their attention upon social, as opposed to instrumental, motivations for behavior.

The results suggest that the influence of social motivations on voluntary cooperation is especially strong. Because organizations focus heavily upon motivating such voluntary behavior, social motivations become even more important to the study of how to obtain desired behaviors in groups, organizations, and communities.

A second purpose of this volume is to test the range within which social motivations are important. While it is not possible to test the model in all group settings, three distinct settings are examined. The first setting involves work organizations (management); employees are interviewed about their workplaces and their views are linked to their workplace cooperation. The second setting is community-based and looks at people’s rule related behaviors (regulation); residents of a large metropolitan community are interviewed about their views concerning law enforcement, and their willingness to cooperate with the police is measured. The third setting is also community-based, but examines political participation using several studies of participation in governance within communities in Africa (governance). By comparing these three diverse settings an assessment can be made of the breadth of the influence of social motivation.

Finally, the third purpose of the volume is to test a psychological model of cooperation. That model argues that organizational policies and practices (procedural justice, motive-based trust) influence dispositions (attitudes, values, identity) and through them shape cooperation.4 This model provides an organizing framework for understanding how the different social motivations are dynamically connected to one another. This psychological model provides guidelines concerning how to exercise authority in groups, organizations, and communities. It suggests that authorities should focus on acting in ways that encourage judgments that they are using just procedures when exercising their authority and that their intentions and character are trustworthy. Procedural justice and motive-based trust lead to favorable dispositions and, through them, motivate voluntary cooperation on behalf of groups.

Beyond Material Self-interest

Psychologists distinguish between motivations, which are the goals that energize and direct behavior, and people’s judgments about the nature of the world used to make plans and choose when to take action and how to behave—that is, which choices to make. This book is about the nature of desired goals.

The issue of cognition or judgment and decision making involves choices that people must make about how to most effectively achieve desired goals. It explores how, once they have a goal, people make decisions about how and when to act so as to most likely achieve that goal. Motivation explores the issue of what goals people desire to achieve. Unless we know what goal people are pursuing, we cannot understand the intention of their actions. Of course, people may make errors that lead them to fail to achieve their desired goals. Nonetheless, their actions are guided by their purposes.

A simple example of the distinction between cognition and motivation is found in the instrumental analyses of action. The goal that energizes people within instrumental models is the desire to maximize their rewards and minimize their costs—for example, the punishments that they experience. To do so, people make estimates of the likely gains and losses associated with different types of actions. These judgments about the nature of the world shape the degree to which people engage in different behaviors in the pursuit of their goal of maximizing rewards and minimizing punishments.

Within the arenas of law, management, political science, and public policy, most discussions of human motivation are drawn from the fields of psychology and economics. The assumption that people are seeking to maximize their personal utilities—defined in material terms—underlies much of the recent theory and research in both psychology and economics. The argument is that people are motivated by this desire, but simplify their calculations when seeking to maximize their personal utilities by “satisficing” and using heuristics. Further, while motivated to maximize their utilities, people also have limits as information processors, making errors and acting on biases. In other words, people may be trying to calculate their self-interest in optimal ways, but lack the ability to do so well; so they are acting out of the desire to maximize their own material self-interest, but they do it imperfectly due to limits in their time, information, and cognitive abilities.

The Interface of Psychology and Economics

In the past several decades there have been tremendous advances in the connection between economics and psychology. Economists have drawn upon the research and insights of psychologists and have also conducted their own empirical research as part of the burgeoning field of behavioral economics. The goal of this volume is to further the connection between psychology and economics by showing the value of considering the range of motivations that are important in social settings.

A major area of psychology upon which economists have drawn in the last several decades is that of judgment and decision making. This area, characterized by the work of psychologists such as Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974, 1981; see also Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky 1982; Kahneman and Tversky 2000), focuses upon the cognitive errors and biases that shape the individual judgments of people seeking to pursue their material self-interest during decision making (Brocas and Carrillo 2003; Dawes 1988; Hastie and Dawes 2001; Hogarth 1980; Nisbett and Ross 1980; Plous 1993; Thaler 1991).

The literature on judgment and decision making is not primarily focused on issues of motivation but on cognition. It seeks to understand how people use their subjective knowledge of the world to make decisions, and assumes that a key motivation for such actions is the desire to maximize material gains and minimize material losses. However, an important message from social psychology is that both cognition and motivation are important. They act in tandem to shape behaviors such as cooperation (see Higgins and Kruglanski 2001). As a consequence, this analysis of decision making can profit from being combined with an expanded analysis of the motivations for action.

In terms of motivations, economists have generally operated on the assumption that people are motivated to maximize their own personal self-interest, a self-interest defined in terms of material gains and losses. No doubt, most psychologists and economists would acknowledge that people can be motivated by a broader range of motivations than material gains and losses, but these other motivations have not been the primary focus of this research. Similarly, the models of human motivation dominating law, management, political science, and public policy have not generally been broader in their focus than to consider the role of incentives and sanctions (Green and Shapiro 1994; Pfeffer 1994).5

While incentives and sanctions have dominated the study of motivation (Goodin 1996), there have been suggestions of the need for a broader focus (Zak 2008). In articulating such a broader vision of human motivation this work connects to the recent work of behavioral economists working in this area (see, among others, Falk and Kosfeld 2004; Fehr and Falk 2002; Fehr and Gächter 2002; Fehr and Rockenbach 2003; Frey 1997; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Stutzer and Lalive 2001). It does so by arguing for the potential benefits—of those involved in studying law, management, political science, and public policy—of considering a broader range of the motivations that can shape behavior in institutional settings.

While the experimental economics literature increasingly acknowledges social motivations, the use of experimental methodologies makes it difficult to compare their degree of influence to that of instrumental motivations. In contrast, the survey approach outlined here makes more explicit comparisons of relative influence in nature settings by providing an estimate of the amount of the variance in cooperation that is explained by a particular group of variables in a real-world setting. Such comparisons highlight the importance of social motivations.

In recent years there has been an increasing effort to empirically examine the internal dynamics of firms—for example, in the relational contract model (Baker, Gibbons, and Murphy 2002). The key argument of the relational contract model is that we need to move beyond the formal structure of organizations, recognizing that formal rules and contracts are incomplete and must be supplemented by an understanding of the more informal “relational contracts” that allow particular people to use their own detailed knowledge of their situation to adapt to new and unique contingencies. Relational contracts offer important advantages over formal contracts because they can be more flexibly linked to the realities of particular situations and people. But they are held in place by weaker organizational forces, making the likelihood of nonadherence a more serious problem for organizations that value relational contracts and want to facilitate their use.

The goal of organizational design, in other words, is to induce greater levels of rule adherence and high performance among the people in organizations by implementing the best possible relational contracts. The question is how to design groups or organizations so as to facilitate the maintenance of relational contracts—that is, to create conditions under which such contracts will be honored even in the face of temptation. In other words, the focus on social motivation in this volume coincides with the increasing focus by economists on interpersonal processes within groups and organizations (see, e.g., Gächter and Fehr 1999).

A similar concern with understanding how people behave in social settings underlies the recent efforts of experimental economists. A major recent effort is a fifteen-society study of cooperative behavior, one that seeks to identify the motivations shaping cooperation. The authors find that beyond seeking material payoffs, people have social preferences—that is, “subjects care about fairness and reciprocity, are willing to change the distribution of material outcomes among others at a personal cost to themselves, and reward those who act in a pro-social manner while punishing those who do not, even when these actions are costly” (Henrich et al. 2004, 8). These authors undertook an ambitious cross-cultural series of studies of cooperation and demonstrated that in none of their fifteen studies were people’s behaviors consistent with a narrow material self-interest model. In each there was evidence of social motivations. Commenting on these cross-cultural studies, Colin Camerer and Ernst Fehr (2004) refer to these motivations as “social utility,” and indicate that they are found throughout societies that differ widely in social, economic, and political characteristics (see also Gintis et al. 2005). The argument that people will accept personal costs to enforce fairness rules is also supported by more recent experimental research (Gürerk, Irlenbusch,´and Rockenbach 2006).

The focus of much of this behavioral economic-based research is to understand how people feel about market situations. It is striking, therefore, that studies consistently find that people use fairness-based judgments in market settings. One approach that people are often found to use is to adjust their marketplace behavior to reflect justice norms (Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler 1986). Further, people will refuse to engage in market transactions when moral principles are being violated (Baron and Spranca 1997; Tetlock and Fiske 1997). Finally, people justice when deciding on the suitability of markets as allocation mechanisms (Frey, Benz, and Stutzer 2004; Sondak and Tyler 2007) or when negotiating (Hollander-Blumoff and Tyler 2008).

A New Framework for Voluntary Cooperation

The goal of this volume is to build upon the suggestion that we need a better understanding of the factors that shape people’s behavior in social settings—that is, to provide a better sense of what social motivations are and how they influence people’s cooperative behavior. To do so this work will present an analysis of several studies and, through them, move toward a broader framework for understanding human motivation within social settings. That framework includes concern with costs and benefits, as well as issues such as “reputation” as defined by economists. As framed in economic analysis, these issues are instrumental and are linked to concerns about material gains and losses. The studies reviewed here suggest that social mechanisms that move beyond such reputational influences also help us to explain additional aspects of voluntary cooperation. These social mechanisms provide another set of goals or reasons that lead people to take the actions that they do when they are in social settings.

In this analysis I will identify several types of social psychological mechanisms that deal with issues relevant to cooperation and to test their importance in organizational settings of three types—managerial, legal, and political. This demonstration is based upon the premise that it is by showing that social motivations strongly influence cooperation that their value in social settings can best be demonstrated.

The core argument is that while people are clearly motivated by self-interest and seek to maximize their material rewards and minimize material deprivations, there is a rich set of other, more social motivations that additionally shape people’s actions. These motivations have an important influence on behavior that is distinct from instrumental calculations but that has not received as much attention as have material gains and losses. The argument that social motives are important has implications for issues of the design of groups, organizations, and communities (Tyler, 2007, 2008, 2009). The primary implication is that there are a broader range of motivations that can be tapped to encourage desirable behaviors than is encompassed within traditional incentive and sanctioning models.6

The Myth of Self-interest

One of the reasons the issue of social motivations has organizational implications is that people are generally found to overestimate the centrality of self-interest and of material gains and losses to the motivation of their behavior. D. T. Miller uses “the myth of self-interest” to capture this idea—that people’s own image of their motivation is skewed in the direction of viewing themselves and others as more strongly motivated by self-interest than is actually the case (see Miller 1999; Ratner and Miller 2001).

Central to this volume is the suggestion that these ideas about human motivation shape institutional designs. Of special concern is that theories can “win” in the marketplace of ideas, independent of their empirical validity (Ferraro, Pfeffer, and Sutton 2005, 8). In particular, the motivational assumptions of economics can be the key to the design of policies and practices within organizations, even when a broader conception of motivation might produce institutions more consistent with the factors actually shaping the behavior of people within organizations.

Two types of cooperation are considered in this volume: rule adherence (following organizational policies and rules) and performance (being productive and creating resources for the group). The starting point of this study is the recognition that people vary in how much effort they exert on behalf of the groups, organizations, and communities to which they belong. The members of most groups can point to examples of people who are always ready to step up and help their group—to volunteer and to take on responsibility for meeting the group’s needs. They can also think of those who often seem to do little more than what is specifically required by their roles in the group, who never voluntarily take on any added obligations, and who are generally uninvolved in their groups. Finally, there are those who cannot even be expected to do what is required by their roles, preferring to shirk those tasks whenever possible.

What predicts these differences in people’s behavior when they are in groups? Why are some people motivated to cooperate more fully with the groups to which they belong than are others? This study will contrast the role of two basic types of motivation in shaping the degree to which people cooperate with the groups, organizations, or communities of which they are members. These are instrumental and social motivations.

The issue of motivation is of concern because people usually have considerable latitude to determine the extent and nature of their efforts within the groups to which they belong. They may choose to expend a great deal of effort on promoting the goals and functioning of the group; or they may take a less active role, and do what they feel is required to get by.7 The choices people make regarding their behavioral engagement with the group have important implications for the group’s functioning and viability. The goal here is to understand the motivations that influence these choices.

Psychologists identify a wide variety of types of potential motivation. This volume will simplify that discussion and focus on the two basic types of motivations, instrumental and social. Instrumental motivations are linked to the connection between cooperation and material self-interest. Irrespective of whether they are motivated by the desire to gain material resources or the goal of avoiding material costs, these behaviors are responsive to people’s calculations of short-term material gain and loss.

Cooperation as a Theoretical Issue

Social scientists generally recognize that people have mixed motivations when interacting with others. On the one hand, there are clear personal advantages to be gained by cooperation. On the other hand, people are often unable to maximize their pursuit of personal self-interest if they act in ways that simultaneously maximize the welfare of the group. So to some extent people are motivated to cooperate, and to some extent to act out of personal self-interest. People must balance between these two distinct motivations (i.e., act on “mixed motivations”) when shaping their level of cooperative behavior. Social psychologists explore the psychological dynamics underlying cooperation in a wide variety of situations ranging from dyadic bargaining (Rusbult and Van Lange 2003; Thibaut and Kelley 1959) to group and community level social dilemmas (see Kopelman, Weber, and Messick 2002; Weber, Kopelman, and Messick 2004). Across all of these literatures, a common theme is the desirability of motivating individuals to act in ways that transcend their self-interest and serve the interests of their groups.

While social psychology is generally focused upon dyads and small groups, mixed-motive conflicts within institutions and communities have been studied most directly by social psychologists within the literature on social dilemmas (Baden and Noonan 1998; Ostrom et al. 2002). This literature asks how people deal with situations in which the pursuit of short-term self-interest by all the members of a group has negative implications for the group and, in the long term, for those people who are members of the group. Social dilemmas have two characteristics: “(a) at any given decision point, individuals receive higher payoffs for making selfish choices than they do for making cooperative choices, regardless of the choices made by those with whom they interact, and (b) everyone involved receives lower payoffs if everyone makes selfish choices than if everyone makes cooperative choices” (Weber, Kopelman, and Messick 2004, 94).

In situations with social dilemma–type characteristics, the interest of the group, organization, or society lies in motivating greater levels of cooperation from the individual. Because cooperation is central to this discussion it is important to clarify what is meant by the term cooperation in this volume. The term is used in various research areas of psychology, and is defined in a variety of ways. In this volume, cooperation will be defined as a decision about how actively to involve oneself in a group, organization, or community through taking actions that will help the group to be effective and successful. These actions may have long-term benefits for the individual, but they are not necessarily linked to immediate benefits or costs. In fact, they are often in conflict with people’s immediate material self-interest.

As noted, the concept of cooperation being used here develops most directly from the literature on social dilemmas. That literature recognizes that there is a conflict between an individual’s immediate personal or selfish interests and the actions that maximize the interests of the group (Komorita and Parks 1994). However, in the long term people have an interest in the well-being of the group. In other words, “social dilemmas can be defined as situations in which the reward or payoff to each individual for a selfish choice is higher than that for a cooperative one, regardless of what other people do; yet all individuals in the group receive a lower payoff if all defect than if all cooperate” (Smithson and Foddy 1999, 1–2). That is, the individual also loses if group resources are destroyed, since she benefits from those resources herself.

And, as in social dilemma situations generally, the individual has mixed motivations. On the one hand, if none of the members of the group cooperate, the group will fail, to the mutual loss of everyone. On the other hand, the individual’s self-interest does not unambiguously lie in maximally cooperating. The individual would benefit if others in the group were to cooperate and she could simply “free ride” on the efforts of others. As Jonathan Baron notes, “each person benefits by consuming the fruits of others’ labor and laboring himself as little as possible—but if everyone behaved this way, there would be no fruits to enjoy” (2000, 434).

In organizations, the benefits of membership depend, in the long term, upon maintaining the efficiency and effectiveness of the group. This requires cooperation from group members. Yet, each individual can easily imagine that others would do the work needed, leaving her free to pursue her own desired activities. Hence, the group urges the person to put aside her immediate concerns and to act on behalf of the group by cooperating. This is a public goods dilemma in the sense that people are tempted to let other group members take on the work of making the group successful but are also at risk if everyone takes this same attitude. If all take a “free ride,” the group will not succeed.

The key issue in this volume is the degree to which people do, in fact, engage in cooperative behavior on behalf of their group. In this case, the people being interviewed are employees in various organizations or residents in a community. Those employees/residents have an interest in gaining the benefits of group membership, and as long as they are in a group, potentially gain when the group is effective and viable. On the other hand, it is often not in their immediate self-interest to follow group policies or to put extra effort into achieving group goals. People’s self-interest can conflict with group interests, as when it is advantageous to steal office supplies, or employees can feel that they have little to gain from working when that work will not be observed and rewarded by management. Similarly, the residents of communities reasonably see risks associated with reporting criminals or otherwise aiding legal authorities.

What Types of Cooperation Influence Group Success?

Two types of cooperation are central to the viability of groups—rule adherence and performance. The aspect of cooperation examined in many experimental games is cooperation that occurs when people follow rules limiting their exercise of their self-interested motivations (Tyler and Blader 2000). People want to fish in a lake, but limit what they catch to the quantity specified in a permit. They want to exploit others in bargaining, but follow rules dictating fairness. They want to steal from a bank, but defer to the law. In all of these situations, people are refraining from engaging in behavior that would benefit their self-interest but is against the welfare of others and/or of their group. This area of research is referred to as regulation and involves limiting undesirable behavior. This aspect of cooperation involves rule adherence—following the rules groups develop to regulate the use of resources.

The other aspect of cooperation involves performance on behalf of the group to create resources or perform tasks for the group (Tyler and Blader 2000). Groups also want their members to actively engage in tasks that effectively deal with group problems. In work institutions these tasks involve job performance issues; in communities they involve working with neighborhood groups, meeting about community problems, and otherwise helping the larger community deal with its concerns. Governments rely upon their members to vote and participate in the political process. The performance of these behaviors encourages the effectiveness and viability of the group.

In sum, the distinction drawn between two functions of cooperative behaviors differentiates between those that proactively advance the groups’ goals through performance of actions that help the group and those that limit behaviors that are obstacles to achieving the group’s goals. What this suggests is that people cooperate with groups both by doing things that help the group in a positive, proactive manner and also by refraining from doing things that may hurt the group. This volume terms these types of behavior or nonbehavior cooperation since people make choices along each of these dimensions as to whether they are going to do things that help (or don’t hurt, as the case may be) the group.

Voluntary Cooperation

Within both forms of cooperation this volume distinguishes between cooperating in required ways and voluntary cooperation. In the case of workplace productivity employees are required to engage in those behaviors that are linked to their job description. Such expected behaviors are the “in-role” behaviors that are defined by their job. For example, they are expected to be in the office during the working hours of 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM. In addition, employees may engage in extra forms of cooperation that are not required, ranging from helping others to coming up with new ideas about how the organization can be more effective. Such “extra-role” behaviors are not a required aspect of the job, and are thought of as voluntary in nature.

With policy adherence and rule-following, employees are expected to act in ways that are consistent with organizational policies and rules about appropriate conduct. Such compliance is part of appropriate behavior within the organization. In addition, employees may or may not follow rules willingly, deferring to them in the sense that they follow rules irrespective of whether their behavior is being observed by others. Such willing buy-in leads people to voluntarily accept the rules.

The focus on social motivations is especially relevant in situations in which the goal is to motivate voluntary cooperative behavior. Motivation is linked to the viability of a strategy of delivery. Employees motivated by incentives need a clear set of expected behaviors and a direct link between those behaviors and rewards. So, for example, coming to work on time and performing clearly specified tasks can be connected to rewards. Sanctions are similar, although they add the complexity that people try to hide their behavior, so there must be effective surveillance strategies in place to detect rule-breaking. In either case, people are not motivated to act in the absence of a link between their actions and a reward/sanction.

In many settings, however, it is desirable for people to engage in cooperation even when incentives and sanctions are not being effectively deployed. As has been noted, even when effective, there are problems with incentive- and/or sanction-based approaches. One way to win the support of employees is to provide them with benefits for themselves. However, it is usually difficult to give everyone all the benefits they want. Further, companies are least able to provide desired benefits during times of transition or economic downturn, when they are most in need to employee cooperation if they are to be viable. Hence, work organizations benefit when people will cooperate for noninstrumental reasons. This analysis labels such cooperation “voluntary” because it is shaped by social, rather than instrumental, motivations.

With sanctions the value of voluntary cooperation becomes even clearer. Sanction-based strategies are always costly to implement because they require the development and maintenance of credible sanctioning strategies. So, for example, it is clear that crimes, such as employee theft, can be deterred by sanctions, but only when management deploys sufficient resources to establish a credible connection between such behavior and the likelihood of being caught and punished. In this context it is clear that the authorities benefit when people cooperate for social, rather than instrumental, reasons. Again, such cooperation is “voluntary” in character.

Tom Tyler and Steven Blader (2000) differentiate between two forms of cooperative behavior: discretionary cooperative behavior and mandated cooperative behavior. Mandated cooperation occurs when people engage in behavior that is dictated or required by group rules or norms. The terms and guidelines of the behavior are prescribed by some rule or policy of the group.

In contrast, discretionary behavior is that which is not directly required by the rules or norms of group membership. Such behavior is “voluntary” in the sense that it is not specifically required by group rules or norms and is not directly linked to incentives or sanctions. Thus, this distinction between types of cooperative behavior involves the nature of the behavior involved. Mandated—that is, required—behaviors originate from external sources (group rules), while discretionary behaviors originate with the group members themselves. For example, carrying out the duties prescribed in one’s job description can be considered mandated behavior. In contrast, picking up trash from the office floor or fixing paper jams in the photocopy machine is something that people may or may not do (unless they are part of a group of employees for whom these tasks are mandatory).

It is worth taking a moment to explain how it is that the performance of mandated behaviors can be cooperative in nature. What is cooperative about doing what one is required to do? One important issue is the quality of the performance of even required behaviors. As already noted, group members usually have considerable latitude in how they carry out their group-related tasks. This latitude includes some freedom in the energy they put into doing what is required and in the quality with which they carry out those tasks. So, for instance, employees can do their jobs in an adequate manner, carrying out their duties as specified without much emphasis on the quality of their work or the nature of the task.

Alternatively, people can perform the same mandated behaviors with an emphasis on high performance and with a concern that the tasks be completed in the best manner possible. Since people have the option of performing these mandated behaviors in either of these forms, cooperation with the group is a relevant concept to consider when examining mandated behaviors. People are cooperating with the groups they belong to when they perform mandated behaviors and especially when they do them with vigor and zeal rather than with a focus on what is merely sufficient.

The enthusiasm with which people engage in their jobs has been recognized to be important even in situations in which theirs are low-level jobs (Newman 1999). Even jobs that seem largely defined by rules and procedures depend heavily for their success on the motivations of employees. Managers cannot effectively supervise all aspects of job performance, or can only do so by investing large amounts of their time and effort in surveillance and instruction. As a consequence, it is important that employees be motivated to do their jobs. Katherine Newman’s study is an excellent example because it focuses on fast food restaurants. Even in that setting, one of highly repetitive jobs and extensive safety regulations, she finds that managers view the willingness to voluntarily help as a highly desirable employee characteristic. This is not only true in work organizations. As has been noted, community cooperation is central to managing community tasks such as social order.

The distinction between two types of cooperative behavior—mandated and discretionary—is important because it is anticipated that mandated behavior is more strongly motivated by instrumental judgments and concerns. Instrumental judgments involve people’s assessments of the likelihood that engaging in cooperative behavior will be rewarded and/or that failing to engage in cooperative behavior will be punished. In other words, there is some direct link between cooperation and people’s material self-interest. In contrast, discretionary behavior is primarily motivated by people’s attitudes and internal values. That is, people’s discretionary behavior is influenced by their sense of what it is desirable and/or right and appropriate to do.

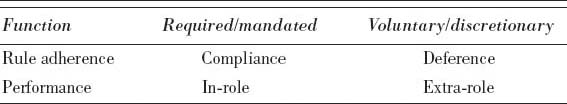

TABLE 1.1

Forms of Cooperative Behavior

One reason for predicting that mandated behaviors will be instrumentally motivated is that rewards and punishments are most typically linked to the degree to which people engage in the behaviors that are required by their group. For example, the salaries of employees are based upon whether and how well they do their job. The group monitors how well people perform their required tasks because those are the criteria that define the behaviors that the group expects from the individual person. Further, expectations are developed by the group member that doing one’s job well will lead to rewards.

In contrast, discretionary behaviors are not specified by the group, and hence are not typically rewarded or punished by the group. The degree to which they are enacted, therefore, is likely to be more strongly dependent upon whether people feel some internal motivation to engage in such discretionary behaviors. These internal motivations develop from attitudes and values, such as feelings about the legitimacy of group authorities or about commitment to the group. These attitudes and values provide people with personal reasons for acting cooperatively, as opposed to extrinsic reasons like the possibility of gaining rewards or the risk of being punished. This is not to say that people’s material self-interest is not affected by whether or not they cooperate. It may be. However, people are not deciding whether to cooperate by looking for a direct linkage between their cooperation and their material self-interest.

Taken together, the distinctions outlined lead to the four forms of cooperation outlined in table 1.1. Complying with rules is distinguished from deference by the expectation that people who defer to rules will do so even in the absence of external losses (sanctions). Similarly, extra-role behaviors are enacted without the anticipation of external gains (incentives). People engage in such behaviors even when they do not anticipate that others will know whether or not they have done so.