CHAPTER FIVE

Cooperation with Political Authorities

The prior discussion of public interactions with the police is an example of the general category of governmental concerns when dealing with local communities and individuals within them. That study was directed at people’s connections to their local communities and to the actions of the police within those communities.

A broader concern is with political authorities. It involves the question of how public views and public satisfaction/dissatisfaction should be studied. I would argue that any government program or policy should be viewed through the framework of how it influences or shapes the relationship that members of the public have with the government. This is equally true of local authorities with whom community residents have personal contact, and national-level political and legal authorities.

The government depends heavily on such voluntary cooperation from citizens (Tyler 2002). We want citizens to cooperate with government in many ways, including to willingly obey the law (Tyler 2006a), to help the police to fight crime and terrorism (Sunshine and Tyler 2003), to be willing to assume duties such as fighting in wars (Levi 1997) and paying taxes (Scholz and Lubell 1998; Scholz and Pinney 1995), and to generally be engaged in their communities and in the political process (Putnam 1993). All of these behaviors are shaped by public views about the government and of its policies and actions. I will argue that these views are social motivations and that government policies and actions need to be viewed through a lens of how they shape the social connections between people and their government. Because it supports such cooperative behavior on the part of citizens, I will argue that social motivations help political systems to be more effective and viable.

For example, the effectiveness of legal authorities, law, and government depends upon the widespread belief among citizens that these are legitimate and entitled to be obeyed. The classic argument of political and social theorists has been that for authorities to perform effectively those in power must convince everyone else that they “deserve” to rule and make decisions that influence the quality of everyone’s lives. It is the belief that some decision made or rule created by these authorities is “valid” in the sense that it is entitled to be obeyed by virtue of who made the decision or how it was made that is central to the idea of legitimacy. While some argue that it is impossible to rule using only power, and others suggest that it is possible but more difficult, it is widely agreed that authorities benefit from having legitimacy, and find governance easier and more effective when a feeling that they are entitled to rule is widespread within the population.

Given the importance of this value, we need to understand how public views about legitimacy—that is, public “trust and confidence”—are created and maintained (Levi and Stoker 2000). If we understand the conditions under which supportive public values, such as legitimacy, play an important role in shaping public actions, we can understand how to build a civic society in which people take the personal responsibility and obligation to be good citizens onto themselves (Tyler and Darley 2000).

One factor that influences legitimacy is public reaction to the organizational issues—the justice of the procedures used to wield political authority and trust in political leaders—leading the impact of governmental policies and practices to shape public views about government. Hence, these social factors need to be a key concern in the long-term effort to create and maintain public support for political authorities and institutions, and for the government more generally. Studies consistently find that a key antecedent of assessments of the legitimacy of government is the judgment about the fairness of the procedures the government uses to exercise governmental authority, and of the trustworthiness of government authorities and institutions (Tyler and Mitchell 1994). And in the political context the judgment of the fairness of the procedures used to empower authority are also found to be distinct and separately important (Gonzalez and Tyler 2008).

Although both outcomes and procedural justice/trust in authorities are found to shape people’s satisfaction with their outcomes when they are dealing with legal authorities (Casper, Tyler, and Fisher 1998), it is the procedural justice of government actions/trustworthiness of government authorities that generalizes to shape views about law and government (Tyler, Casper, and Fisher 1989). Hence, when it makes policies, the government needs to not only be sensitive to the objective quality of those policies but to how their creation and implementation is viewed by the public.

Underlying our policy analysis is the view that government depends upon the goodwill and voluntary acceptance of most of the members of the community most of the time. In the terms already outlined, the public needs to be positively disposed toward government and hence more willing to voluntarily cooperate with government authorities and institutions. This means that to be effective, government authorities must be sensitive to the appearance of fairness as well as to its reality; they need to create and implement public policies with an awareness of how the public views those policies. Based upon empirical research it is clear that the public is very ethical in its evaluations of authorities, judging them against criteria of fairness and trustworthiness. In particular, the public is very sensitive to its assessment of whether the authorities are exercising their authority in ways that are fair. Such procedural justice judgments shape the legitimacy of the authorities in the eyes of citizens and influence whether people cooperate with authorities.

The goal of this examination of political authority is to expand the consideration of the motivations underlying cooperation in several ways. Most obviously, the scope of the study is enlarged by the type of cooperation being examined. Here the focus is on two types of voluntary cooperation in the political arena.

The first type is participation in the political process by attending political meetings, raising political issues, contacting political authorities, and becoming involved in the political process through attending rallies and demonstrations. The second type is voting in elections.

Second, this research moves beyond that already discussed because it considers societies in which both instrumental and social factors vary more extremely than is true within the United States. In the case of Africa, for example, people are focused upon basic instrumental necessities such as having food or water. There are also dramatic variations in the justice of government procedures, the trustworthiness of political authorities, and the legitimacy of government. Hence, the range of the variables under consideration is larger than has been true in the previous analyses.

Social Motivations in Political Settings

In discussing social motivations in managerial and community settings, I have used the results of panel data sets. In examining the role of social motivations in political settings, I rely upon secondary analysis of two previously collected cross-sectional data sets that are based upon interviews with samples of people living in Africa. The first, Afrobarometer Round 1, contains 21,531 interviews with people from twelve African countries. The interviews were conducted in 1999–2001.1 The second, Afrobarometer Round 3, includes 25,397 interviews with people from eighteen African countries that were conducted in 2005.2 The Round 2 interviews were not considered in this analysis because they did not include relevant questions.

My focus in analyzing both surveys is upon the antecedents of two types of participation: political participation and voting behavior. Instrumental motivations are those linked to government performance in meeting basic economic and social needs. Social motivations include attitudes toward government, values, identity, procedural justice, and trust in authorities.

Each analysis includes several types of control. First, dummy variables were included to account for the country in which the interview occurred. Second, country-level objective indices of economic performance and quality of governance were included.3 Finally, respondent demographic characteristics—age, gender, and education—were included. These controls were added during the first stage of a two-stage regression analysis. Instrumental and social motivations were added during the second stage.4

Round 1

Respondents were asked about their participation in their community, using items that included both attending community meetings and raising political issues as well as their recent voting behavior.5 Both indices reflect voluntary behavior. The participation index ranged from never (0) to often (3). The mean level of participation was 0.84. Among those registered to vote, in countries that had elections, 5 percent indicated that they decided not to vote; 15 percent did not vote, for whatever reason; and 80 percent voted.

Instrumental motivations include, first, the level of social welfare, which is the frequency with which people get basic services such as food and water,6 and government economic performance in dealing with social problems.7 Social motivations included attitudes toward government,8 legitimacy,9 identification with society,10 procedural justice,11 and trust in specific government institutions.12 These two overall indices were moderately intercorrelated (r = 0.19, p < .001).

Round 3

Respondents were asked about their participation in their community, including attending community meetings, raising political issues, and contacting political authorities,13 as well as their recent voting behavior. Both indices reflect voluntary behavior. In the case of participation, the index ranged from never (0) to often (3). The mean level of participation was 0.46. In the case of voting, 5 percent of those interviewed decided not to register; 2 percent registered, but then decided not to vote; 3 percent registered and intended to vote but for some reason were unable to do so; and 90 percent registered and voted.

Instrumental motivations include the level of social welfare,14 government economic performance,15 and the degree of enforcement of the law.16 Social motivations included attitudes toward government,17 legitimacy,18 procedural justice,19 and trust in specific government institutions.20 The correlation between social and economic indices was 0.38 (p < .001).

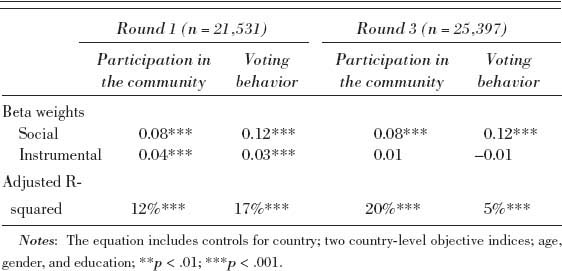

TABLE 5.1

Antecedents of Cooperation

The results of the regression analysis are shown in table 5.1.21 In both of the surveys, people’s attitudes, values, identity, and judgments about procedural justice and trust influenced the two cooperative behaviors considered—political participation and voting. Further, that influence was found to be distinct from the effects of instrumental judgments about instrumental issues such as social welfare and the quality of government performance. In Round 1 the influence of social motivations upon participation decisions was twice as strong as that of instrumental motivations, while in Round 3 only social motivations influenced decisions about participation. In Round 1 social motivations were four times as influential in decisions about whether to vote as were instrumental motivations, while in Round 3 only social motivations influenced the decision about whether to vote.

The findings suggest that people are more likely to participate in the political process of their community by attending meetings, raising issues, and contacting government and other authorities when they have favorable social motivations—that is, favorable attitudes, supportive values, a positive identity, a view that the procedures of government are fair, and a trust in political authorities. There is also some evidence that better economic/social conditions (i.e., favorable instrumental conditions) promote cooperation.

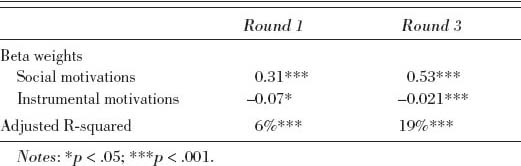

An alternative approach to examining the influence of social motivations upon cooperation is to consider the respondents’ judgments without including objective information about their social/political environment. This approach was used with a structural equation model in which economic and social motivations were treated as indicators of latent factors and were used to predict a latent factor of cooperation. The results are shown in table 5.2.22

TABLE 5.2

Antecedents of Cooperation among African Respondents

The results support the suggestion that social motivations have a reliable and distinct influence upon cooperation. And because these results examine that influence when considered alone, they also provide an estimate of the magnitude of that influence. In Round 1, it is 6 percent of the variance in cooperation; in Round 3, 19 percent. This increase reflects the better measurement of both types of motivation in the later round of the Afrobarometer. If we completely exclude instrumental indices from the analysis and simply consider the ability of social motivations to explain cooperation, the amount of variance in cooperation explained for Round 1 is 6 percent, and for Round 3, 18 percent. In other words, the social motivations are the primary factors shaping the overall equations shown in table 5.2, since the amount of variance explained remains essentially the same irrespective of whether instrumental judgments are considered.

These findings reinforce those in table 5.1, which shows that instrumental and social motivations influence cooperation above and beyond the objective nature of people’s economic and political environment. Of the two, social motivations show the strongest distinct influence. Further, that effect is consistently positive, with greater procedural justice and trust, stronger favorable attitudes and identity, and more supportive values leading people to engage in more voluntary cooperation. The analysis in table 5.2 similarly supports the argument that social motivations have a distinct positive influence and suggests that their influence can be strong. This strength is most clearly suggested in the Round 3 data, where both social and instrumental motivations are better measured.

As noted at the beginning of this chapter, one motivation for using an African data set is the centrality of instrumental issues to people’s lives. For example, in Round 3, 38 percent indicated going without food several times or more, while 37 percent indicated a similar frequency of going without water, 42 percent without medical care, 66 percent without a cash income, and 30 percent without cooking fuel. Hence, instrumentally based social welfare issues are central to people’s lives, and this setting is a key one in which to consider the influence of social motivations. Are people whose lives are focused on issues such as obtaining basic resources still affected by social motivations in deciding whether to be involved in the political process?

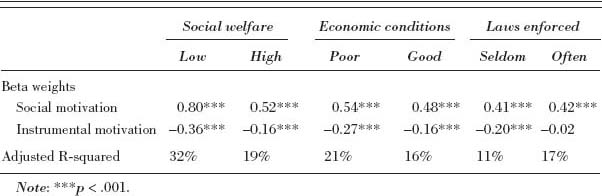

TABLE 5.3

The Influence of Social Motivations under Varying Economic Situations

To examine the influence of instrumental circumstances on social motivations, respondents were divided at the median on the three instrumental indices: social welfare (frequency of receiving basic services), economic conditions (government performance in dealing with economic problems), and whether or not the laws were enforced against the wealthy and connected.

The structural equation-based regression shown in table 5.2 was then run within the subgroups created. The results are shown in table 5.3. The findings are consistent across the three instrumental variables. First, having a more difficult instrumental situation led people to be more likely to participate in the political process for instrumental reasons. This is reflected in the negative coefficients shown in table 5.3, which consistently indicate that negative circumstances lead to more political behavior. In addition, however, those who have stronger social motivations were consistently found to be more politically cooperative, irrespective of their instrumental circumstances. In fact, to the extent that there is variation, social motivations were more strongly linked to political cooperation under more negative instrumental circumstances. There was no evidence that social motivations became irrelevant under more unfavorable social and economic circumstances, but instrumental issues do become more important.

These findings suggest that when we consider an environment where both instrumental and social motivations vary more widely than they did in the American samples already considered, we continue to find strong evidence of the effects of social motivation upon voluntary cooperation. Further, we find these effects upon cooperation to be of a new type—interactions with political authorities and institutions. Here the focus is upon political cooperation, both by generally participating in the political process and by voting. Hence, these findings support the prior suggestion that social motivations shape cooperation.

I have already noted that cooperation with authorities is especially key during times of scarcity and crisis, when collective resources are stressed and greater sacrifices are required from members for a society to be able to prevail. These findings reinforce the view that in such settings social motivations are a key antecedent of the willingness of the public to cooperate in the political process under difficult circumstances. Margaret Levi (1997) gives one example of this connection by showing a link between trust in government and the willingness to serve in the military during wartime, and the findings herein support that suggestion and extend it to the link between social motivations (of which trust is one) and general political cooperation.

Combined with our prior findings these results suggest that, irrespective of whether our focus is on groups, institutions, or society in general, social motivation is an important antecedent of effectiveness because it leads to high levels of engagement and motivation among group members. People who feel connected to groups do what is needed to help them succeed when they feel a link to group authorities and institutions.

The argument that supportive attitudes and values—such as trust and con-fidence in political authorities and institutions—facilitate group effectiveness parallels the findings reported here based upon studies of managerial and legal authority. All of the types of institutions discussed rely heavily upon the loyalty of their members and, as a result, benefit enormously from members’ willingness to “go the extra mile” to help them. Employees who support management are more invested in their jobs and bring to the workplace more creativity and a greater willingness to put in whatever effort is needed to get the job done. The result is that such companies are more likely to prevail in competitive business environments. The degree to which firms have desirable attitudes, such as trust, among their employees shapes the quality and quality of the work performed. Through their influence upon work performed employee attitudes shape the profitability of organizations and, consequently, their likelihood of long-term survival. Similarly, political scientists argue that if citizens support government and are willing to act on its behalf, the government is more stable and effective.

As I have noted, previous authors have argued for the importance of legitimacy to effective governance. These findings support the argument that social motivations play a distinct role in shaping voluntary political behaviors. These findings support that argument, but make the broader point that social motivations, which include legitimacy, have a distinct influence on voluntary cooperation. That point reinforces the argument of the prior chapters which showed a similar effect in managerial and community settings.

The large literature on the value of social capital for communities that has developed in recent years argues that it is important for people to have the types of associations with others that build trust and encourage active political participation (Putnam 2000). Within work organizations researchers have shown the importance of voluntary extra-role behaviors to the effectiveness of work organizations (Tyler and Blader 2000). And legal authorities have emphasized the centrality of public cooperation to efforts to maintain social order. Hence, the importance of being able to engage people’s internal motivations has become more widely recognized.

Policy Implications

The data examined herein explore the influence of social motivations, including trust and procedural justice, upon participation in the political process in Africa. They suggest that social motivations shape cooperative behavior in this environment, one characterized by high levels of instrumental need and wide variations in procedural justice, trustworthiness, institutional legitimacy, identification with society, and supportive attitudes toward government. Hence, these findings suggest the breadth of the findings already outlined and their potential applicability to a wide variety of social contexts.