CHAPTER SIX

The Psychology of Cooperation

The key concern addressed in this volume is how to most effectively motivate cooperative behavior in groups. The analyses in the prior chapters suggest that social motivations are generally important in any effort to motivate cooperation within groups, organizations, communities, or societies. And this is especially the case when voluntary cooperation is at stake. While the prior chapters address this point directly, they do not consider a subsequent question arising from the importance of social motivations. That question is how to best understand the interrelation among social motivations. This issue is addressed by Tom Tyler and Steven Blader (2000, 2003) in the context of the group engagement model. Here I want to address this question by distinguishing between those aspects of social motivation that are directly linked to group structure—group-based policies and practices—and those social motivations that are dispositional in character. This distinction is important because it is those social motivations that are linked to group-based policies and practices that shape dispositions and influence cooperative behaviors. They need to be the focus of efforts to motivate desired behavior. Procedural justice and trust are elements of groups that are linked to their policies and practices and therefore can be shaped by changes in how groups function. They are, therefore, the natural focus of efforts at institutional design.

Procedural Justice

The argument underlying the procedural justice literature is that people defer to decisions because those decisions are made through fair processes. This procedural justice effect is found to be distinct from the influence of concerns about either outcome favorability or outcome fairness. As such, procedural justice provides a way for acceptable decisions to be made in situations in which people cannot be given what they want or feel they deserve. Similarly, the literature on trust argues that people will defer to authorities that they infer are trustworthy (Tyler and Huo 2002).1

John Thibaut and Laurens Walker (1975) conducted the original procedural justice research, and their hope was that people would be willing to accept out-comes because those outcomes are fairly decided upon—that is, because of the justice of the decision-making procedures used to achieve them. Thibaut and Walker performed the first systematic set of experiments designed to show the impact of procedural justice. Their studies demonstrate that people’s assessments of the fairness of third-party decision-making procedures independently shape their satisfaction with their outcomes. This finding has been widely con-firmed in subsequent laboratory studies of procedural justice (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler et al. 1997).

The original hope of Thibaut and Walker was that the willingness of all the parties to a dispute to accept decisions that they viewed as fairly arrived at would provide a mechanism through which social conflicts could be resolved. Subsequent studies find that when third-party decisions are fairly made, people are more willing to voluntarily accept them (Kitzman and Emery 1993; Lind et al. 1993; MacCoun et al. 1988; Wissler 1995). What is striking about these studies is that procedural justice effects are found in studies of real disputes, in real settings. They confirm the earlier experimental findings of Thibaut and Walker. The results of procedural justice research are optimistic about the ability of social authorities to bridge differences in interests and values and to make decisions that the parties to a dispute will accept. Their arguments point to a particular perspective on institutional design and provide evidence to support that perspective.

Procedural justice judgments are found to have an especially important role in shaping adherence to agreements over time. For example, Dean Pruitt and colleagues have studied the factors that lead those involved in disputes to adhere to mediation agreements that end disputes (Pruitt et al. 1993). They find that procedural fairness judgments about the initial mediation session are a central determinant of whether people are adhering to the mediation agreement six months later.

A second study also suggests that procedural justice encourages long-term obedience to the law. Raymond Paternoster and collegues examined the long-term behavior of people who dealt with the police because the police were called to their home on a domestic violence call (Paternoster et al. 1997). In such cases the problem was typically that a man was abusing his spouse/significant other. When they were at the person’s home the police could threaten the man, and even arrest and take him into custody. The researchers explored the impact of various police actions upon the man’s likelihood of committing future abuse. Their study found that a strong predictor of future rule-breaking was whether the man involved experienced his treatment by the police as fair. If he did, he was less likely to break the law in the future.

Beyond the fairness of the manner in which authorities make particular decisions, studies generally find that when a climate or culture of procedural justice characterizes an institution, compliance with rules is more widespread and more easily obtained. Consider the case of prisons, institutions that people often think of as highly coercive. Even in prisons authorities seek and benefit from cooperation by prisoners, and studies of prisons suggest that the fair administration of prison rules facilitates such cooperation (Sparks, Bottoms, and Hay 1996).

The argument that legitimacy is rooted in the fair exercise of authority is not a new one, or one that only applies to policing. Philip Selznick’s classic examination of industrial settings makes a similar point about workplace rules, commenting that “There is a demand that the rules be legitimate, not only in emanating from established authority, but also in the manner of their formulation, in the way they are applied, and in their fidelity to agreed-upon institutional purposes. The idea spreads that the obligation to obey has some relation to the quality of the rules and the integrity of their administration” (1969, 29). This argument has received widespread support in studies of employee behavior in workplaces (see, e.g., Tyler and Blader 2000).

Similarly, discussions of national level legal authority—in particular, the U.S. Supreme Court—emphasize that its legitimacy is linked to public views about the fairness of its decision making procedures. Walter Murphy and Joseph Tanenhaus (1968) have noted that the Court has retained a substantial reservoir of public support even when it makes unpopular decisions. They attribute this continued support for the legitimacy of the Court’s role as an interpreter of the U.S. Constitution to the public belief that the Court’s decisions are principled applications of legal rules and not political in character. This point has been emphasized by members of the Court itself, when arguing that it must present an image of “principled” decision making to retain public support (Tyler and Mitchell 1994).

Motive-based Trust

This analysis treats motive-based trust as developing in parallel with procedural justice. Of the two constructs, it is motive-based trust that is the less clearly defined. Procedural justice refers to definable procedural features. On the other hand, trust is an inference about something unobserved—the intentions, motives, and character of an authority. However, as Fritz Heider recognized in his classic work on interpersonal perception (1959), it is this unobservable set of motives and intentions that people infer from the behaviors that they observe in others. And studies in groups consistently find that people place considerable weight upon their inferences about other’s character and motives (Tyler and De-goey 1996), using such judgments to evaluate and respond to people’s actions. Hence, the same action can be responded to very differently depending upon inferences about the motives that underlie it. In this analysis, trust and procedural justice are treated as two aspects of group-based policies and practices.

Testing the Model

Is a focus on procedural justice and motive-based trust a good way to shape dispositions and motivate voluntary cooperation? In other words, if we distinguish between policies and practices (procedural justice, trust), dispositions (attitudes, values, identification), and cooperative behaviors, is there evidence that policies and practices shape cooperation by influencing dispositions?

This argument can be tested using causal modeling and the panel datasets that have already been outlined: one on employees in work settings, the other on residents in communities. First, consider the panel study of employees. We can create latent variables to reflect three constructs: social motivations (procedural justice, motive-based trust), instrumental motivations, and dispositions (attitudes, values, identity). Using those latent constructs, the influence of group-based policies and practices upon attitudes and cooperative behaviors can be examined.

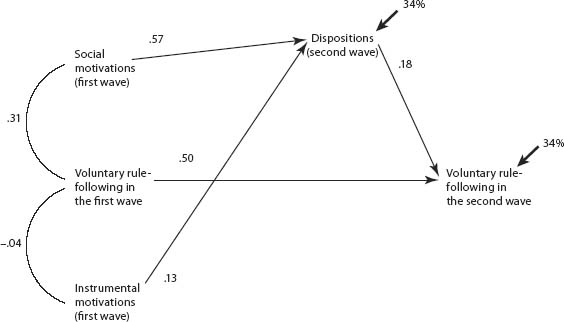

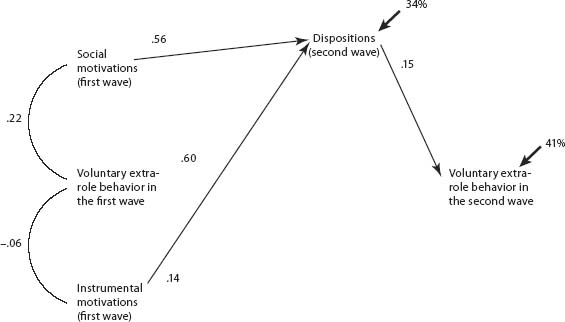

Figure 6.1 examines the influence of group-based policies and practices upon dispositions and on voluntary rule-following within the sample of employees. Figure 6.2 presents a similar analysis using extra-role behavior as the dependent variable. In each analysis the dispositions and behaviors in the model are those measured during the second-wave interviews, while social motivations and instrumental judgments are measured during the first-wave interviews. As a consequence, the causal flow is from group-based policies and practices to dispositions and behaviors. And because the design is a panel design it is possible to control for the influence of cooperation as reported during the first interview.

In both cases the panel analyses results support the argument that a focus upon social motivations is a good way to understand how to shape dispositions and influence cooperative behavior in work settings. In both social motivations are the primary factor shaping dispositions, with a secondary influence of instrumental motivations. Hence, loyalty to groups is strongly related to evaluating those groups as having fair procedures and trustworthy authorities. And people are more strongly loyal to those groups that deliver desired resources.

The results also indicate that dispositions shape voluntary cooperation. In both models there are no direct paths from either social or instrumental aspects of group-based policies and practices. Rather, both paths flow through dispositions. Hence, developing favorable dispositions toward the group is the key to promoting voluntary behavior. Although two distinct types of voluntary behavior are considered—voluntary rule-following and extra-role behavior—what is most striking about the analyses is their similarity. There are no differences linked to what type of voluntary cooperation is at issue.

FIGURE 6.1. Employee voluntary rule-following (CFI = 0.81).

FIGURE 6.2. Employee extra-role behavior (CFI = 0.80).

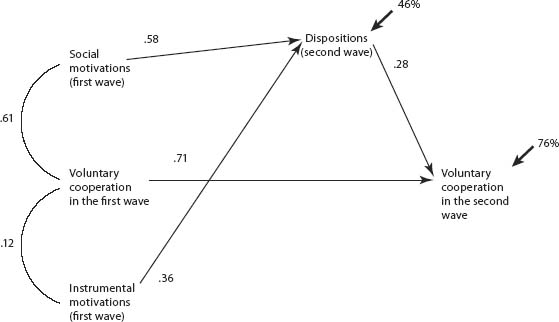

FIGURE 6.3. Voluntary cooperation with the police (CFI = 0.83).

Figure 6.3 shows a similar analysis of cooperation in the case of the residents of New York whose panel interviews were considered in chapter 4 and focus on their willingness to cooperate with the police. In this case, the issue is the willingness to engage in actions that help the police to manage social order in one’s community either by reporting crime and criminals or by joining collective efforts to police the community. This could be motivated by instrumental judgments, such as the effectiveness of the performance of the police, or by social motivations, including identification with the police, judgments about their legitimacy and morality, and the favorability of attitudes toward them. Again, voluntary cooperation flows from favorable dispositions that are shaped primarily by procedural justice and motive-based trust, but also by instrumental evaluations. In this case, the balance between social motivations and instrumental motivations is more even, with instrumental motivations having a greater role in shaping dispositions. However, as before, the influence of both social and instrumental motivations flows through dispositions.

The Influence of Social Motivations on Dispositions

These analyses indicate that policies and practices shape dispositions, and through them influence voluntary cooperation. The link to dispositions is important because it shows the effect of policies and practices on people’s general orientation toward their group. In other words, the particular actions taken by authorities and the policies they adopt have a broad and long-lasting impact upon people because they lead to a general disposition toward the group. This general orientation then shapes whatever forms of cooperative behavior are relevant in any given context and at any particular moment.

Further, while the figures in this chapter show an overall effect of policies and practices upon dispositions a separate analysis of each disposition indicates that in both of the studies procedural justice and motive-based trust have a distinct influence upon each of the four dispositions: identification with the police, attitudes toward the police, legitimacy, and moral value congruence.

Process-based Design

The analyses outlined provide a theoretical framework for understanding the psychology underlying cooperation. Process-based design is a strategy for managing within groups, organizations, communities, and societies that is based upon the arguments of this psychological model. Such an approach can be applied to work organizations through process-based management, to law with process-based regulation, and in politics via process-based governance.

In unpacking the social motivations described in the model it is important to make a distinction between group-based policies and practices that lead authorities to be viewed as procedurally just and trustworthy, dispositional factors (attitudes, values), identity, and cooperative behaviors. The reason for making this distinction is to allow a focus on strategies for building social motivation and securing high levels of voluntary cooperation.

The goal here is to articulate and support empirically a model for exercising authority in groups, organizations, and communities that I believe provides authorities with useful insights about how to create and sustain motivation. This model is process-based. Process-based design applies the ideas of the social psychology of procedural justice (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler 2001; Tyler et al. 1997; Tyler and Lind 1992; Tyler and Smith 1998) and motive-based trust (Tyler and Huo 2002) to issues central to all types of groups. This volume presents a particular perspective on the psychology of justice and on its implications for the dynamics of groups, organizations, and communities.

As I will demonstrate, research in widely disparate types of groups suggests that common principles underlie motivation across diverse settings. My suggestion is that these common principles inform the exercise of authority irrespective of whether a person is managing a group, an organization, or a community, and irrespective of whether one is wielding legal, political, managerial, or some other form of authority. Of course, context matters, and there are distinct issues within any particular type of group. However, my goal in this volume is to stress what is common across these diverse types of social settings.

I will contrast the process-based approach to group design to the instrumentally based command-and-control model of authority. This model concentrates collective resources in authorities, who then use those resources to shape the behavior of group members via strategies involving the use of incentives and sanctions. Studies suggest that such approaches are able to shape cooperative behavior. However, as I have already outlined in some detail, they are often costly and inefficient, and I argue that process-based approaches are a valuable addition to the strategies that authorities can use to motivate behavior in groups.

It is difficult to attempt management in a process-based manner because it goes against our intuitions about “human nature.” As noted earlier, the “the myth of self-interest” has been coined in recognition of the widespread belief in our society that people are motivated by the desire for personal gain. People, themselves, describe their motivations, as well as the motivations of others, as being to gain all that they can for themselves. Further, people think about such gains in terms of material gains—that is, as money, possessions, power. So we “know” that people really care about outcomes, and it is difficult not to manage based upon the belief that people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are shaped by their reactions to the favorability and fairness of the resources they gain or lose when dealing with others.

We tend to assume that people are motivated by the level and favorability of the resources they receive in groups. So we expect that people will work harder if paid more, will follow the rules if they think they would be caught and punished for breaking them, and will leave a group when given the opportunity to move to a group with greater resources and opportunities.

This view of human motivation flows easily into a widespread model of authority—the command-and-control model—that argues that authorities manage by providing incentives for desired behaviors and threatening or delivering sanctions for undesirable behavior. By deploying their resources, authorities can shape the gains and loses experienced by those within their groups and thereby shape their behavior.

The process-based and command-and-control models differ in several ways. First, they differ in their view about how to exercise authority in groups. Instrumental approaches lend themselves to a command-and-control approach to the exercise of authority. Resources and power are concentrated in authorities, who then deploy those resources in systems of incentives and sanctions. Second, they differ in their view about the goal of authorities. Instrumental approaches focus on the aim of creating and maintaining structures within which people’s behavior is instrumentally motivated to move in line with group goals. The maintenance of desired behavior requires the continued presence of systems for delivering incentives and for the surveillance of behavior and the delivery of sanctions.

The process-based approach to design focuses on the concerns of those people within a group. It builds systems of authority and management in an effort to understand and connect with the concerns of the individuals within the group. Because this model builds itself on the premise that people’s own internal judgments are motivating, it seeks to activate those internal motivations. Once activated, these motivations are separate from instrumental aspects of the person’s relationship to the group. Hence, the process-based model is based on the idea of gaining commitment from group members by focusing on their perspective about what a just group climate is. This climate includes, but is not necessarily limited to, group procedures for decision making. It also involves how people are treated by authorities during decision making, something typically found to be influential in shaping trust. This leads to supportive attitudes and values and a merging of self and group in the formation of identity (Tyler and Blader 2000).

These two sets of motivations—instrumental and process-based—are not completely independent of one another. And it is not necessary that they be independent for process-based approaches to be an effective strategy. What is important is that process-based motivations be distinct from instrumental motivations, something tested in the studies examined in this volume. Of course, instrumental motivations also support identity and can potentially join with social motivations in building identity and encouraging cooperation.2

As intuitively plausible as the outcome-based view of human nature and motivation is, research does not support it as an exclusive focus. Process-based management builds on that research by focusing on other issues that people are actually found to care about, including processes and the motivations of authorities.

One simple reason to focus on procedures is that, as has been shown, people’s cooperation within organizations is strongly shaped by their judgments about processes. Although people could potentially make decisions about whether to accept decisions, whether to work hard, and/or whether to stay or leave based upon either outcomes or processes, research consistently finds that people are actually the most strongly influenced by their process-based judgments and their assessments of the trustworthiness of authorities. Process-based approaches build directly on this finding by leading to the exercise of authority in ways that shape these judgments. By so doing, those engaged in the process-based exercise of authority are managing by giving people what they want when they deal with authorities and organizations. People want to experience fair processes, and they want to feel that the authorities and institutions with whom they are dealing are worthy of their trust. By focusing on exercising authority in ways that connect with these human desires, authorities can more effectively gain desirable behavior from those within their groups.

While social and instrumental motivations can act in conjunction, as noted, it is also important to remember that instrumental motivations can undermine social motivations. Further, even when they act in concert, there are reasons to prefer social motivations. In particular, even when they are effective, instrumental motivations require large amounts of collective resources to deliver incentives and/or maintain credible sanctioning risks. Social motivations do not require the use of such collective resources and can, therefore, free up resources for other group tasks.

A further gain associated with process-based approaches is that they build up supportive attitudes and values among group members. Such attitudes and values are desirable because when people have these internal motivations, they are personally motivated to engage in desirable behaviors and do so without the need for incentives or surveillance. Their behavior becomes self-motivated in the sense that their actions are governed by their own values and are not linked to external resources. Hence, an additional reason for focusing on the process-based issues of procedural justice and trust is that these judgments about experience have a strong influence on people’s internal motivations—that is, their attitudes and values. People can potentially be motivated by either extrinsic or internal motivations, but the advantages of self-motivation are clear.

Tom Tyler (2009) presents this argument in the context of law and legal authority, arguing for a self-regulatory approach to social order. The point here is similar. However, regulation has traditionally dealt with only one aspect of cooperation: stopping undesirable behavior. The broader argument here is that self-motivation leads both to self-regulation and also to the desire to do what helps groups.

Elements of Procedural Justice

An understanding of the elements of procedural fairness that form the basis for process-based management strategies can best be based on the four-component model of procedural justice, which was developed in work settings (Blader and Tyler 2003b). This model identifies four procedural components, or evaluations, each of which contributes to overall procedural justice judgments. Those com ponents are defined by (1) two distinct aspects of organizational processes, and (2) two sources of information about procedures. Each of these four components influences employee definitions of procedural justice.

One of the aspects of organizational processes considered in the model refers to the organization’s decision-making procedures. Specifically, the model considers employees’ evaluations of the quality of decision making in their organization. Consideration of these evaluations links to the elements of legal procedures and emphasizes issues of decision maker neutrality, the objectivity and factuality of decision making, and the consistency of rule application (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler and Lind 1992).

There is a distinct, but potentially equally important, issue involving the quality of people’s treatment by organizational authorities. Quality of interpersonal treatment constitutes the second aspect of organizational processes. Quality of treatment involves treatment with politeness and dignity, concern for people’s rights, and other aspects of procedures that are not directly linked to the decisions being made through the procedure.

Each of these two aspects of procedures (quality of decision making, quality of treatment) can potentially be linked to two sources of procedure. One source of information involves the rules of the organization. The formal rules and structures of the organization, as well as statements of organizational values, communicate information about organizational procedures. For example, organizations vary in terms of whether they have formal grievance procedures that allow people to voice complaints. They also differ in their statements of corporate values (“corporate vision statements”). One common formal organizational statement that concerns relationships among employees is to “treat each other with respect, dignity, and common courtesy” and “express disagreements openly and respectfully.” These are both statements about the type of procedures that the corporation views as reflecting its values.

The other source of information is an employee’s experience with his supervisor or supervisors. While they are constrained by formal institutions and procedures, organizational authorities typically have considerable discretion concerning the manner in which they implement decision-making procedures and how they make decisions regarding issues that have no formal procedures associated with them. Further, they have a great deal of flexibility about how they treat those with whom they deal. The same decision-making procedure can be implemented in a way that emphasizes the dignity of those involved, or employees can be treated rudely or dismissively. A similar situation is found with the law. There are formal laws and rules constraining the conduct of police officers and judges. However, those authorities typically have considerable latitude in the manner in which they exercise their authority within the framework of those rules.

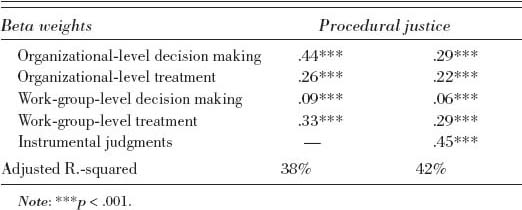

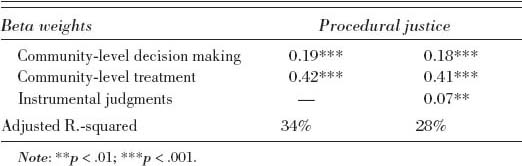

TABLE 6.1

Components of Procedural Justice: Employees

The four-component model argues that each of the four elements defined by these two dimensions has an important role in the definition of the fairness of procedures. While the four-component model provides a guideline for the types of evaluations that compose overall evaluations of an organization’s procedural justice, the essential argument advanced here is that the nature of those evaluations is noninstrumental and nonmaterial. Neither of the aspects of organizational processes emphasized in this model of the antecedents of procedural justice (quality of decision making, quality of treatment) is directly linked to evaluations of the favorability or fairness of the outcomes people receive.

The four-component model highlights a set of procedural criteria that are distinct from judgments about the favorability or fairness of employee’s outcomes. This is, of course, typical of procedures in any type of organization. We can, for example, distinguish the adversary trial procedure from the verdict of the trial, and can contrast that procedure to other ways of making decisions, such as the inquisitorial trial procedure.

Is the four-component model supported by the findings of the studies outlined? To test the model the four components were measured in the study of employees, and a structural equation model–based regression analysis was used to test the influence of each component on overall judgments of procedural justice and motive-based trust. This test was conducted with and without controls on instrumental judgments. The instrumental judgments were treated as indicators of a single observable indicator of instrumental elements of the job.

The results of the analysis are shown in table 6.1. They support the suggestion of the four-component model in finding that the four elements each contribute to overall procedural justice, irrespective of whether instrumental judgments are included in the equation. The four-component model is a good framework Components of Procedural Justice: Community within which to understand the organizational policies and practices that are central to justice.

TABLE 6.2

Components of Procedural Justice: Community

A similar analysis was conducted using the community-based sample and similar results are shown in table 6.2.3 In this case, overall indices of decision making and interpersonal treatment were used, since there is no parallel distinction between work group and organization; hence, the judgments are community level assessments. Again, both decision making and interpersonal treatment were important for procedural justice, irrespective of whether instrumental judgments were controlled for.

Trust

I have presented a four-component model that is shown to have wide applicability. It focuses upon two key components: quality of decision making and quality of interpersonal treatment. These two elements are found to have distinct influence, an influence that occurs both at the general organizational level and in subgroups, such as work groups in organizations. How does this analysis relate to issues of trust? In contrast to the literature on procedural justice, the literature on trust has not developed a detailed model of the antecedents of trust. As a consequence, this analysis will consider the influence of the same aspects of policy and practices that have been shown to shape procedural justice.

Why Are Authorities Trusted?

The analysis in this volume follows that of Tom Tyler and Yuen Huo (2002) and treats trust as a distinct aspect of authorities, not something that is part of procedural justice. But the two are intertwined. Trust is sometimes seen as an an tecedent of procedural justice, and sometimes treated as occurring in parallel to procedural justice. When we do treat trust as an antecedent of procedural justice we typically find that it is the most important issue shaping procedural justice judgments in the context of personal experiences with an authority. When we treat trust and procedural justice as independent we find that both contribute strongly to decision acceptance.

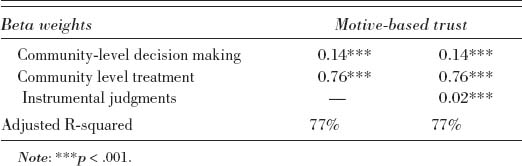

TABLE 6.3

Components of Trust: Employees

TABLE 6.4

Components of Trust: Community

Treating trust as distinct from procedural justice allows the issue of what promotes trust to be directly addressed. One element revealed as important in these analyses is the quality of decision making. If people are allowed to present their concerns to a neutral authority, they are more likely to trust it. Further, when people feel treated with dignity and respect they are more trusting. Authorities can facilitate these beliefs by justifying their decisions in ways that make clear that they have considered the arguments raised and either can or cannot accept those arguments. It is also important for authorities to make clear that they are sincerely interested in the well-being of the parties involved—for example, through acknowledging the needs of those involved, the difficulties they may be operating under, and/or their efforts to act in good faith.

Although the framework for understanding policies and practices used to consider trust was developed in the context of procedural justice, it also helps us to understand motive-based trust. Hence, the elements of fair decision making and just interpersonal treatment that shape overall assessments about the fairness of group procedures also shape trust in group authorities. These two judgments are clearly intertwined, and regardless of whether we treat them as distinct and parallel influences or consider trust as an element of procedural justice, the broader implication is the same. Policies and practices of the type outlined shape dispositions and influence cooperation.