Who are the owners of web 2.0 sites, and what are their motivations for providing their services? Often the owners of web 2.0 platforms are media corporations. Google for example owns YouTube and Blogger, Yahoo owns Flickr, and News Corporation owns Myspace. According to the Forbes 2000 ranking1 News Corp’s assets are $US 56.13 billion, the assets of Google amount to $US 40.5 billion, and the assets of YouTube are $US 14.49 billion. Obviously the aims of these companies are generating profits and increasing their capital stock. At the same time access to the mentioned 2.0 platforms is free of charge. Thus, why do these companies provide web 2.0 services for free? In this context critical scholars (Fuchs 2009b; Scholz 2008) have stressed that web 2.0 is about new business models, based on which user-generated content and user data are exploited for the profit purposes. In this case users receive access to web 2.0 platforms for free, and profit is generated by selling user data and space for advertisements. Selling user data for profit generation requires the surveillance of web 2.0 users for collecting these data. In order to understand how far capital accumulation in web 2.0 is connected to surveillance, in this chapter I address the following question:

How does surveillance contribute to capital accumulation on web 2.0, and how do the owners of commercial web 2.0 sites collect and disseminate user information?

In order to answer this question, first some hypotheses about and theoretical foundations of consumer surveillance on web 2.0 are outlined (section 2). Section 3 describes the method used for the empirical case study. In section 4 the results are described and interpreted. Conclusions are drawn in section 5.

In the following I will give a brief outline of the central notions and concepts that are used in this chapter: surveillance, consumer surveillance, and web 2.0.

Neutral definitions of surveillance argue that surveillance does not necessarily imply coercion, domination, or oppression. They focus on the collection, storage, processing, and transmission of information about individuals, groups, masses, or institutions, irrespective of the context, motivations and consequences of surveillance. They either do not refer to the purposes of surveillance and the interests behind surveillance (see for example Ball/Webster 2003, 1; Solove 2004, 42; Bogard 2006, 101; Bogolikos 2007, 590) or they do not judge whether these purposes are normatively desirable or not (see for example or Ball 2006, 297; Clarke 1988, 499; Rule 1973/2007, 21). Sometimes neutral definitions explicitly point at the ambiguity of surveillance (see for example Hier and Greenberg 2007, 381; Lyon 2007, 137; Clarke 1988, 499; Haggerty 2006, 41; Lyon 2003, 13). In contrast to neutral definitions, negative notions of surveillance consider the latter always as a form of domination. Such understandings stress the coercive, hierarchical, and dominative character of surveillance and can for example be found in the work of Michel Foucault (1977/2007), Oscar Gandy (1993), Toshimaru Ogura (2006), and Christian Fuchs (2008; 2009a). So there are on the one hand neutral concepts of surveillance and on the other hand negative ones.

Consumer surveillance can be understood as a form of surveillance that aims at predicting and, in combination with (personalized) advertising, controlling the behaviour of consumers (Turow 2006, 282). Unlike workers, consumers for a long time were not under the control of capital. They were an anonymous mass, buying standardized mass products (Ogura 2006, 273). But as Campbell and Carlson state the “last decades of the twentieth century also saw a massive expansion of efforts to use surveillance technologies to manage consumers” (Campbell and Carlson 2002, 587).

According to Mark Andrejevic, the increased tendency towards consumer surveillance is a reaction to the growing amount and variety of consumer products, which make necessary “techniques to stimulate consumption” (Andrejevic 2002, 235). To stimulate consumption means controlling the behaviour of consumers, that is, to make them buy certain commodities or services. Advertising is used as a means for influencing consumer behaviour. As Turow puts it: “the goal of advertising is straightforward: to persuade people to purchase or otherwise support the product, service or need” (Turow 2006, 282). The more knowledge an advertiser has on consumers and their behaviour, the more specifically they can be addressed by advertising campaigns. Ogura stresses that the main motive for consumer surveillance is to know as many details as possible about the behaviour of unknown customers (Ogura 2006, 271). This allows the creation of personalized marketing campaigns, which are tailored to the habits, lifestyles, attitudes, hobbies, interests, etc. of specific consumers or consumer groups. The idea behind personalized advertising is that the more appealing an ad is to a specific individual the more likely it is that s/he will buy a certain product.

For personalized sales strategies to be successful, marketing campaigns need to create the illusion that individuality and authenticity can be achieved by buying certain consumer products. Contemporary sales strategies thus rest on the surveillance and categorization of consumers as well as on an ideology that ties individuality to specific consumption patterns. Mass media play an important role in disseminating this ideology. In this context Mathiesen has coined the notion of the synopticon. In his view “synopticism, through the modern mass media in general and television in particular, first of all directs and controls or disciplines our consciousness” (Mathiesen 1997, 230). Controlling the behaviour of consumer, that is to make them buy certain commodities and services, also requires controlling their mind. Surveillance and manipulation are two complementary strategies for influencing consumer behaviour. Capital can only be accumulated when commodities and services are sold and surplus is realized. The more commodities people buy, the more capital can be accumulated. Capital is therefore interested in influencing consumer behaviour in order to sell evermore commodities and services. Thus, if consumer surveillance stimulates consumption, it serves the interest of capital.

The term web 2.0 is used for describing technological changes and/or changes in social relations and/or changes in technology usage and/or new business models. It has also been argued that the term web 2.0 describes nothing really new because web 2.0 is not based on fundamental technological advancements (see for example boyd 2007, 17 Scholz 2008, online). Some critical scholars have argued that these terms function as a market ideology for stimulating profit generation. Christian Fuchs for example argues that “the main purpose behind using these terms seems to be a marketing strategy for boosting investment” (Fuchs 2009b, 80; see also Scholz 2008, online).

However, irrespective of whether these terms describe technologically new phenomena or whether they have been used as ideologies for advancing new spheres for capital accumulation, the fact is that the term web 2.0 today is widely used for describing an increasing amount of commercial and non-commercial web applications that have in common the involvement of users in the production of content. Technological refinements have made it much easer for users to produce their own media (Harrison/Barthel 2009, 157, 159).

Most understandings of web 2.0 have in common that they point at this active involvement of users in the production of content, that is user-generated content, as the central characteristic of web 2.0 (boyd 2007, 16; Fuchs 2008, 135; 2009, 81; Cormode/Krishnamurthy 2008, online; O’Reilly 2005, online; Bruns 2007, online; van Dijck 2009, 41; Allen 2008, online; Harrison/Barthel 2009, 157; Kortzfleisch et al. 2008, 74; Jarrett 2008, online; Beer/Burrows 2007, online).

The main hypothesis that underlies this empirical study is:

H: The terms of use and privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms are designed to allow the owners of these platforms to exploit user data for the purpose of capital accumulation.

Zizi Papacharissi and Jan Fernback (2005) conducted a content analysis of privacy statements of 97 online portal sites. They tested the credibility as well as the effectiveness of these statements and found that “privacy statements frequently do not guarantee the protection of personal information but rather serve as legal safeguards for the company by detailing how personal information collected will be used” (Papacharissi and Fernback 2005, 276). Their study focused on the language used in these statements but did not evaluate which information online portal sites do collect and use. In a subsequent discourse analysis of privacy statements they analyzed the rhetoric of four corporate web 2.0 (MSM, Google, Real.com, and Kazaa) applications and found out that privacy statements support profit generation (Fernback and Papacharissi 2007).

The business model of most commercial web 2.0 platforms is to generate profit through selling space for advertisements (Fuchs 2009b, 81; Allen 2008, online). Thus web 2.0 platforms provide their services for free in order to attract as many users as possible (Fuchs 2008, 2009b). Selling space for advertisements in order to generate profit is nothing new. Traditional media companies also employ this strategy. Dallas Smythe (1981) has in this context pointed out that media companies generate profit by selling media consumers as a commodity to advertisers.

Fuchs (2009b) has applied Smythe’s notion of the audience commodity to web 2.0. He argues that in contrast to traditional media environments on web 2.0, users are not only recipients but, at the same time, also producers of media content. They can therefore be characterized as prosumers or produsers (Fuchs 2009b; Bruns 2007, online; van Dijck 2009, 4; see also Toffler 1980). Advertisers favour personalized advertisements over mass advertisements because personalized advertisements increase the effectiveness of marketing campaigns (Charters 2002; Fuchs 2009). As personalized advertisements for advertisers are more valuable than mass advertisements, the owners of web 2.0 platforms can charge higher rates for personalized ads. Because personalized advertising is based on information about consumers, I assume that the owners of commercial web 2.0 platforms, in order to increase their profits, surveil users, and sell information about them to advertisers.

This main hypothesis will be tested along with the following three topics and six sub-hypotheses:

1. Advertising (H1a and H1b)

2. Data Collection (H2a and H2b)

3. Data Dissemination (H3a and H3b)

H1a: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to target users with personalized advertisements directly on the platform.

H1b: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms is allowed to target users with personalized advertisements via e-mail.

The average user of user-generated content sites is highly educated and well paid (van Dijck 2009, 47). Thus, “all UGC [user generated content] users—whether active creators or passive spectators—form an attractive demographic to advertisers” (van Dijck 2009, 47). Furthermore the technical features of Internet technologies such as web 2.0 provide various means for personalized advertising (see for example: Campbell and Carlson 2002; Starke-Meyerring and Gurak 2007; Wall 2006).

Because the aim of every company is to increase its profits, it is likely that the owners of web 2.0 platforms will make use of the technical possibilities and the available information about users for purposes of profit accumulation. Because selling space for personalized advertisements is a potential source for profit accumulation (Allen 2008, online; Fuchs 2009; van Dijck 2009), I hypothesize that commercial web 2.0 companies will place such ads directly on the platform (see H1a) as well as distribute them via e-mail (see H1b).

2. Data Collection

H2a: The majority of commercial Web 2.0 platforms are allowed to track the surfing behaviour of users for advertising purposes.

User information available on web 2.0 platforms not only includes information that users provide by themselves, but also information about their surfing behaviour, IP address, and their technical equipment, which is collected automatically while they are using the platform.

José van Dijck (2009) argues that especially automatically tracked data about the surfing behaviour of users is of interest for advertisers. Petersen (2008, online) also stresses that what is valuable on web 2.0 sites is not content, but context data. Advertisers are not only interested in user data but also in their actual behaviour. Tracking data about consumer behaviour and providing this information to advertisers constitutes another potential source of profit for web 2.0 companies.

H2b: In order to use commercial web 2.0 platforms, users in a majority of cases have to provide the following personal information: e-mail address, full name, country of residence, gender, and birthday.

Although data about the surfing behaviour and IP addresses of users can be tracked automatically, other personal information has to be actively provided by users. Van Dijck states that in order to use a web 2.0 site, users have to register and provide information about themselves such as name, gender, e-mail address, nationality, etc. (van Dijck 2009, 47). Web 2.0 users are both “content providers” and “data providers” (van Dijck 2009, 47). The more data web 2.0 users provide, the more data can be sold and the more profit can be generated. Thus the owners of web 2.0 platforms are interested in gathering as much information about users as possible. One possibility for forcing users to provide data about themselves is an obligatory registration on the platform.

3. Data Dissemination

H3a: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to sell aggregated information.

H3b: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to sell personally identifiable information.

Web 2.0 companies can increase their profits by selling not only space for advertisements, but also information about users to advertising companies. These companies use this information in order to create targeted advertisements. In terms of the panoptic sort (Gandy, 1993) this means that web 2.0 platforms identify information about consumers and pass it on to marketing companies that categorize and assess this information in order to create personalized advertisements.

A common distinction in regard to personal data is the differentiation between personal information and personally identifiable information (PII). PII is generally conceived as information that reveals the identity of a unique person (Krishnamurthy and Wills 2009, 7; Reis 2007, 383). It is “a unique piece of data or indicator that can be used to identify, locate, or contact a specific individual” (Reis 2007, 383). PII includes full name, contact information (mail address, e-mail address, phone number), bank and credit information, and social security number (Reis 2007, 383). Information that is collected anonymously (for example, age, gender, race, purchasing habits), as well as aggregate information about a group of individuals, is generally not considered as PII (Reis 2007, 383).

Both kinds of personal information can potentially be sold to advertisers. Thus selling this information is another possibility for satisfying a web 2.0 company’s desire for capital accumulation.

The hypotheses described in section 2 were addressed by conducting a content analysis of the terms of use and privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms. It mainly focused on quantitative measures. Nevertheless the quantification of results needs to be based on a qualitative analysis of the sample. As Krippendorff states, “the quantitative/qualitative distinction is a mistaken dichotomy” (Krippendorff 2004, 86) because “all reading of texts is qualitative, even when certain characteristics of a text are later converted into numbers” (Krippendorff 2004, 16). Krippendorff mentions four important components of a content analysis (compare: Krippendorff 2004, 83). These components are:

• Unitizing (selecting those texts that are of interest in order to answer the research questions)

• Sampling (selecting a manageable subset of units)

• Recording/coding (transforming texts into analyzable representation)

• Narrating (answering the research questions)

The methodological procedure employed in this empirical study was oriented on these principles. First relevant texts (units), were identified. Second, a sample of all units was selected, which was subsequently coded. In a fourth step, the hypotheses were answered by evaluating the results of the coding (see section 4).

The units, on which this content analysis is based, are the terms of use and privacy statements of web 2.0 platforms. These documents constitute a legal contract between owners and users of web 2.0 platforms, and define rights and responsibilities of both platform owner and users. Because they describe what platform owners are allowed to do with user data (Papacharissi and Fernback 2005; Fernback and Papacharissi 2007; van Dijck 2009, 47; Campbell and Carlson 2002, 59), these documents are a viable source for figuring out how far platform owners are allowed to collect and disseminate user data.

The sample selection was based on the Alexa Top Internet Sites Ranking. Alexa provides a daily updated ranking of the 1,000,000 most popular sites on the Internet. The ranking is compiled based on a combination of the number of daily visitors and page views (see Alexa.com). The sample was selected based on the 1,000,000 most popular sites ranking from April 27, 2009. All web 2.0 platforms that were among the top 200 sites were selected.

For the purpose of this study web 2.0 sites were defined as sites that feature content that is entirely or almost entirely produced by users (see section 2). According to this understanding, web 2.0 involves wikis, weblogs, social networking sites, and file-sharing sites (sharehoster).

The selection process resulted in a sample of 71 sites that mainly feature user-generated content. Two of these had to be excluded because they provided neither terms of use nor privacy statements.2 Another four sites were excluded because they are subsites of sites that were listed earlier in the ranking.3 Thirteen sites had to be excluded because of language barriers. On these sites, the privacy policies and terms of use were not available in English, German, or Spanish4 and therefore could not be coded. The final sample consisted of 52 web 2.0 platforms. The terms of use and privacy statements of these platforms were downloaded on April 27, 2009, and analyzed according to a predefined coding scheme.

The construction of the coding scheme followed the six subhypotheses, underlying this study. As a pretest, the privacy policies and terms of use of ten randomly selected platforms were analyzed according to the initial coding scheme. After the pretest, the coding scheme was redefined and extended.

The final coding scheme was structured along the following four main categories:

• General characteristics

• Advertising

• Data collection

• Data dissemination

Within the category “general characteristics”, two subcategories were used in order to evaluate under which conditions users can access the platform and how the user has to accept the terms of use. The category “advertising” aimed at grasping the advertising practices of web 2.0 companies and consisted of five subcategories that addressed advertising, personalized advertising, third-party advertising, e-mail advertising for the platforms own products and services and e-mail advertising for third-party products and services. The category “data collection” consisted of four subcategories. These were used in order to find out how and what information about users is collected on web 2.0 platforms. The subcategories included: employment of behavioural tracking techniques for advertising purposes, association of automatically tracked data with a user’s profile information, required information for platform usage, and data combination. The category “data dissemination” comprised three subcategories concerning whether platform owners are allowed to sell statistically aggregated, non-personally identifying information and personally identifying information about users to third parties. If the analyzed terms of use and privacy policies did not contain information on a specific category, this category was coded 99, i.e., “not specified”.

The content analysis was based on a sample of 52 web 2.0 platforms: 51 of them are commercial. The only non-commercial platform among the sample is Wikipedia. Since the hypotheses refer to commercial web 2.0 platforms, Wikipedia was excluded from the data evaluation. Thus the following results are derived from a content analysis of 51 commercial web 2.0 platforms. Section 7.4.1 describes the quantified results of the content analysis and answers the hypotheses. In section 7.4.1 the results are interpreted and supplemented with some qualitative findings.

The following description of results is structured along three main topics of the content analysis

1. Advertising

2. Data Collection

3. Data Dissemination

1. Advertising

H1a: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms is allowed to target users with personalized advertisements on the platform.

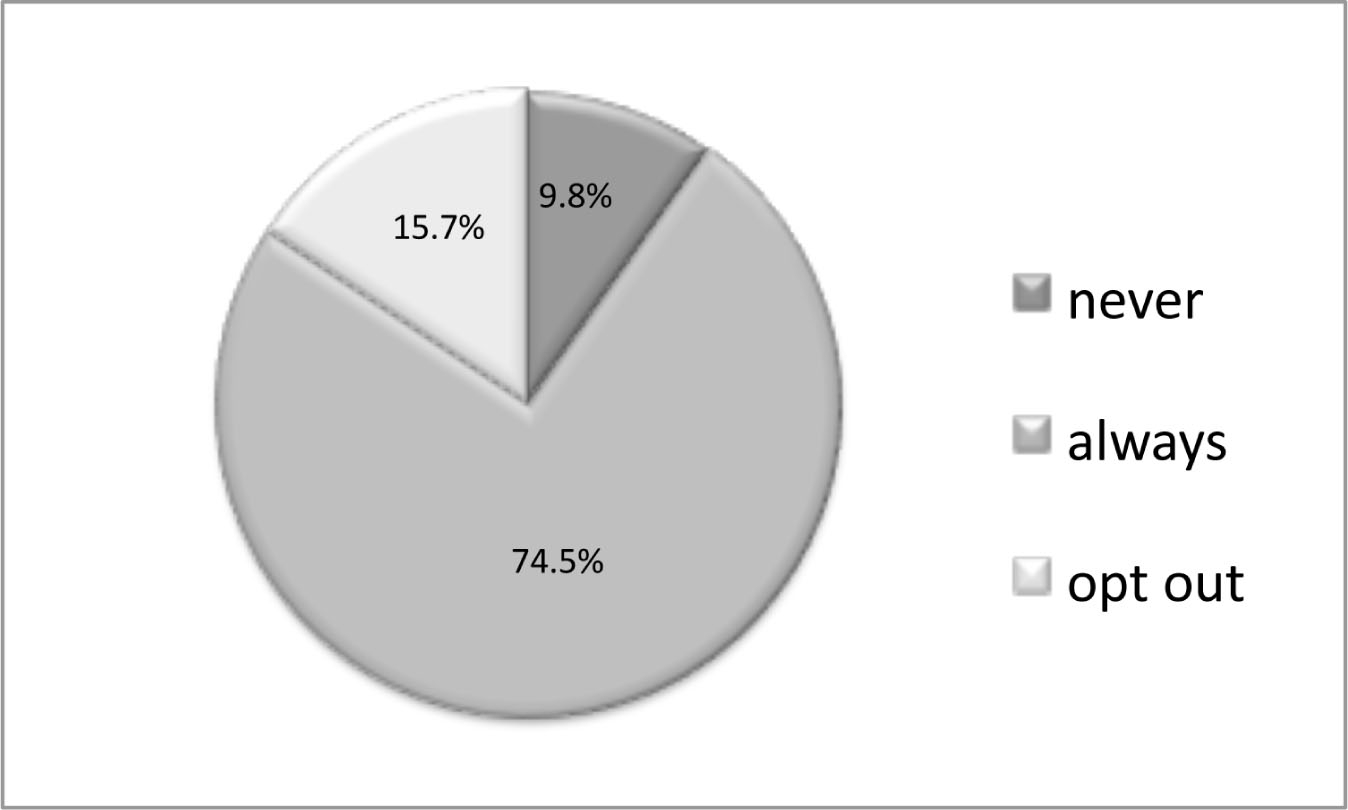

Of all analyzed commercial web 2.0 platforms, 94.2% display advertisements. Only on 5.8% of all analyzed platforms advertisements will never be shown to users. Figure 7.1 illustrates that on 74.5% of all analyzed platforms personalized advertisements can be found. In these cases the user does not have any way to deactivate this feature (opt-out). On another 15.7%, personalized advertising is activated as a standard setting, but the user is allowed to opt out. This means that in total, on 90.2% of all analyzed web 2.0 platforms personalized advertisements are potentially shown to users. Only 9.8% of all analyzed platforms never feature personalized advertisements.

Figure 7.1 Personalized advertising on commercial web 2.0 platforms, N=51.

Of all commercial web 2.0 platforms, 58.9% explicitly state in their privacy statements that they allow third-party advertising companies to place cookies on users’ computers for personalized advertising purposes, without giving the user a way to opt out. Another 7.8% allow users to opt out of third-party cookies. This means that on 66.7% of all analyzed platforms third-party cookies are activated as a standard setting. Only 3.9% of all commercial web 2.0 platforms explicitly state that they do not allow third parties to use cookies in order to collect information about users. The remaining 29.4% of all analyzed privacy statements do not refer to whether or not they support third-party cookies.

These results confirm H1a: On the vast majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms, users receive personalized advertisements; on 74.5% of all analyzed platforms personalized advertisements are always shown to users; 15.7% provide the possibility to deactivate personalized ads. Furthermore 56.9% of all analyzed platforms allow third parties to place cookies on a user’s computer. On 7.8% third-party cookies are allowed unless a user explicitly deactivates this feature.

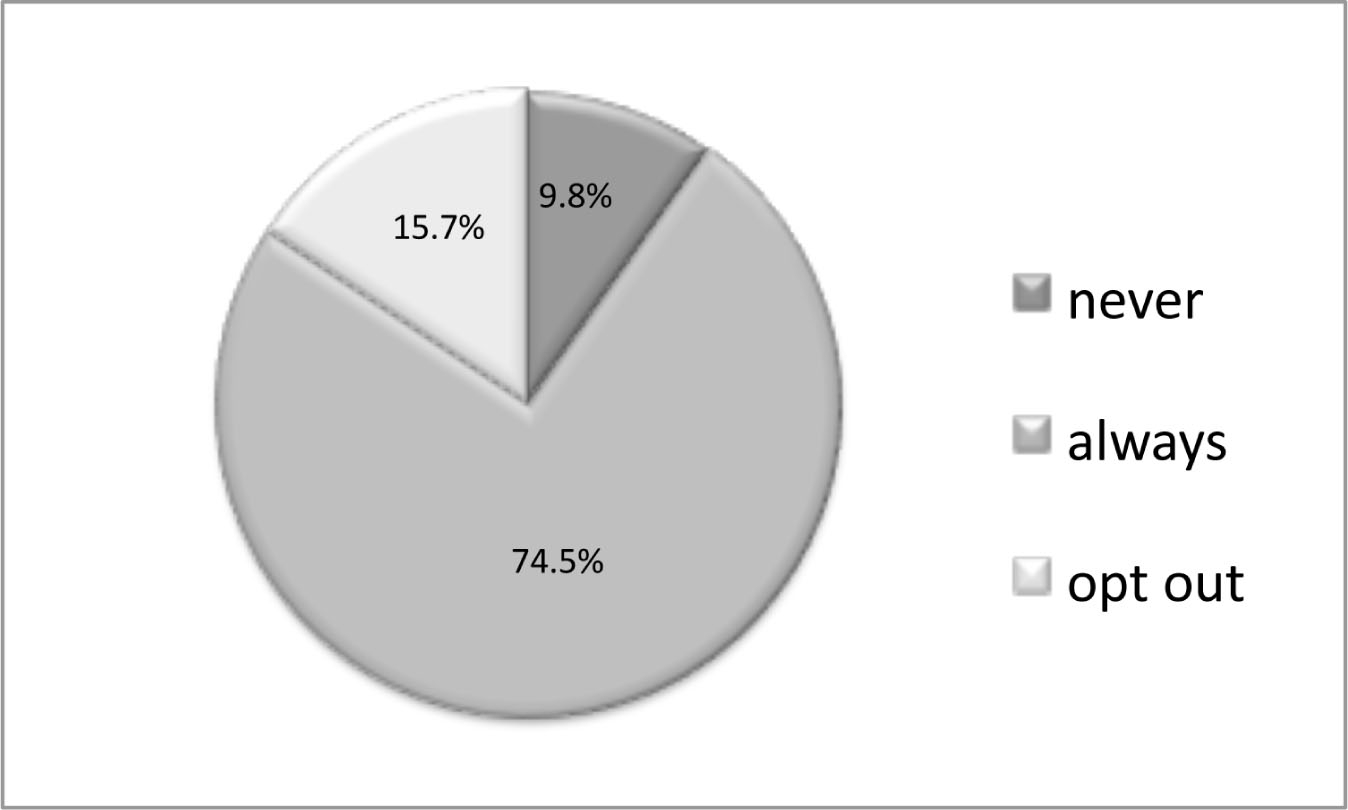

H1b: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to target users with personalized advertisements via e-mail

On 58.9% of all analyzed commercial web 2.0 platforms, the default setting is set so the user’s e-mail addresses are used for advertising the platforms’ own products and services. On 19.7% of all analyzed platforms this standard setting is unchangeable, but 39.2% do permit users to modify this default setting and to opt out of receiving such advertising e-mails. Another 17.6% allow users to opt in for receiving advertising e-mails regarding the platforms products and services, and 23.5% never use the user’s e-mail address for their own advertising purposes (see Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Advertising E-mails on Commercial Web 2.0 Sites, N=51

Of all analyzed commercial web 2.0 platforms, 62.7% do not use users’ e-mail addresses for advertising third-party products and services; 25.5% by default send advertising e-mails for third-party products and services; 15.7% give users a way to deactivate this feature (opt-out). On 9.8% of all analyzed sites users are not alowed to opt out of receiving advertising e-mails for third-party products and services. On 11.8% of all commercial web 2.0 platforms users can opt in for receiving third-party advertising e-mails (see Table 7.1).

Using the contact information provided by users for advertising products and services is a common practice on web 2.0. Nevertheless, on the majority of sites (56.8%), the user is put in the position to choose whether or not s/he wants to receive advertising e-mails (opt-in or opt-out). Less frequently the user’s e-mail address is used for advertising third-party products and services. On the majority of sites (62.7%) users will not receive third-party advertising e-mails.

2. Data Collection

H2a: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to track the surfing behaviour of users for advertising purposes.

The data evaluation confirms this hypothesis and shows that the vast majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to track the surfing behaviour for advertising purposes: 94.1% of all commercial web 2.0 platforms use behavioural tracking techniques for surveilling the behaviour of users on the site; 80.4% use the gathered information for advertising purposes.

H2b: In order to use commercial web 2.0 platforms, users in a majority of cases have to provide the following personal information: e-mail address, full name, country of residence, gender, and birthday.

On all analyzed commercial web 2.0 platforms, users have to complete a registration form for receiving full access to all services. During the registration process, users are required to provide certain information. On all platforms, users have to provide their e-mail address. Name as well as birthday is required on 54.9%, gender on 43.10%, and country on 37.3 % of all analyzed web 2.0 platforms.

3. Data Dissemination

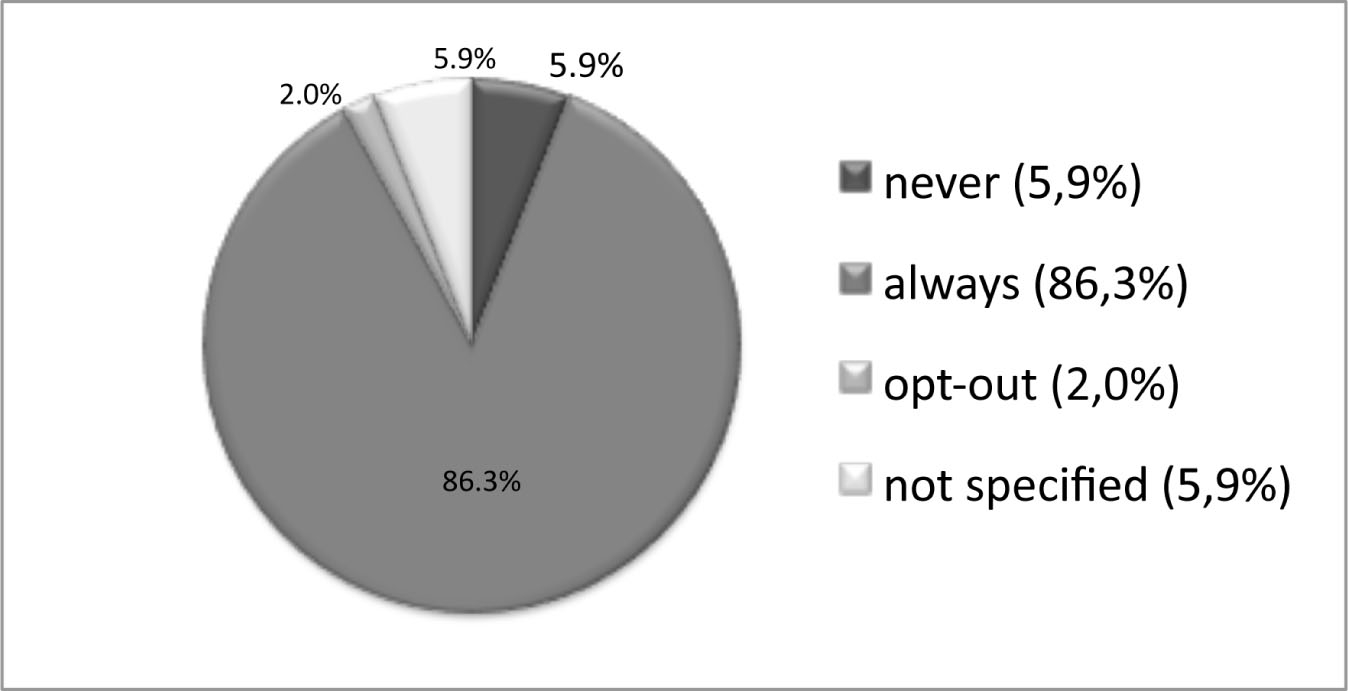

H3a: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms is allowed to sell aggregate information.

Of all analyzed privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms, 86.3% state that platform owners are allowed to pass on aggregate information about users to third parties for any purpose. In these cases the user does not have a way to opt out. Only 2% allow users to opt out of passing on aggregate information about themselves; 5.9% do not explicitly state whether or not circulating aggregate information is allowed. Only 5.9% declare that aggregate information is never handed on to advertisers (see Figure 7.2). Aggregated information involves all kind of information that does not personally identify a specific user. Thus it can include demographic information and other information provided by users (except of name contact information and social security number), as well as information regarding the surfing patterns of users.

Figure 7.2 Dissemination of aggregate information on commercial web 2.0 platforms, N=51.

Furthermore the privacy statements also indicate that 58.9% of all commercial platforms allow third parties to track the surfing patterns of users directly on the platform (see H1a). In this case instead of gathering and selling aggregated information about users, platform owners sell access to user data to third parties that gather information about users on their own.

These results confirm H3a and show that almost 90% of all commercial platforms are allowed to aggregate information about users and sell this information to advertisers.

H3b: The majority of commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to sell personally identifiable information.

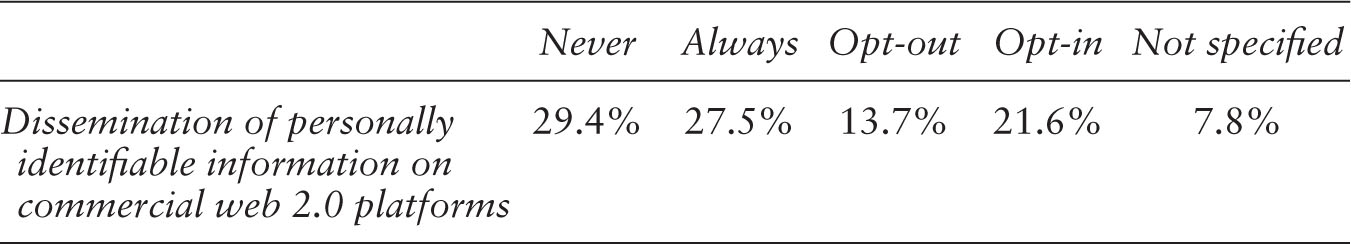

On the one hand 29.4% of all analyzed commercial web 2.0 platforms in their privacy statements state that they under no circumstances pass on any information that identifies a user personally. On the other hand 27.5% are by all means allowed to circulate personally identifiable information. On 13.7% of all platforms, personally identifiable information is only handed onto third parties until a user opts out: 21.60% have to ask for a user’s permission to pass on personally identifiable information—that is, users have to explicitly opt in. And 7.8 % of all platforms in their privacy statements do not state how they deal with data that personally identifies an individual (see Table 7.2).

Table 7.2 Dissemination of Personally Identifiable Information on Commercial Web 2.0 Platforms, N=51

As these data show, personally identifiable information is less frequently passed on to third parties than aggregated information. In approximately one-third of all cases (35.3%) users are allowed to choose (opt-in, opt-out) whether or not they want to allow the dissemination of information that personally identifies them. In approximately a second third (29.4%) of all cases personally identifiable information will under no circumstances be passed on to third parties. Approximately a third (27.5%) of all platforms do sell PII under all circumstances.

The first important result of this study is that there is only one non-commercial platform among the 52 most popular web 2.0 sites (1.9%). The fact that contemporary web 2.0 is mainly a commercial web 2.0 has far-reaching consequences for users, because the main aim of these platforms is profit maximization. As will be shown, this motive of profit maximization at the same time creates financial benefits for platform owners and a broad range of disadvantages for individuals and society.

This study has confirmed the assumption that the business model of commercial web 2.0 platforms is based on advertising. Thus, users receive access to web 2.0 platforms for free, and profit is generated by selling space for advertisements. The content analysis has shown that in more than 90% of all cases these advertisements are even personalized. Personalized advertising aims at targeting specific individuals or groups of individuals in a way that fits their lifestyle, interests, habits, or attitudes. It is based on the assumption that the more specifically an ad is directed towards an individual, the more likely it will influence his/her actual shopping behaviour. Thus this form of advertising is considered more effective than mass advertising. Therefore the owners of web 2.0 platforms can charge higher advertising rates for personalized advertisements, which allow them to increase their profits.

Because web 2.0 is based on user-generated content it potentially constitutes a useful data source for advertisers. Apart from selling space for advertisements, selling these data is another convenient strategy for web 2.0 platform owners to generate profits. But before this information can be sold, it needs to be collected and stored. The more user information is available to platform owners, the more information can be sold and the more profit can be generated. This study shows that there are two main ways to collect data in web 2.0: First, users provide information about themselves either in the course of using the site or during the registration process. The fact that on 100% of all analyzed sites, registration is required for receiving full access to the platform’s services ensures that every user provides at least a minimum of information about him/herself. As the following quotation from the terms of service of Tagged.com illustrates, commercial web 2.0 platforms try to learn as much as possible from each user:

During registration, users also complete survey questions that provide information that is helpful for us to understand the demographics and consumer behavior of our users, such as identifying the users’ eye color, style, personality type, favorite color, sport, food, activity or TV show, post-graduation plans or graduation year. (Tagged Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

Second, on most commercial platforms (94.1%) behavioural tracking methods are used to automatically store data on a user’s hardware, software, or site usage patterns. This double strategy for collecting information about users that can be used for personalized advertising is for example expressed in the YouTube privacy policy:

We may use a range of information, including cookies, web beacons, IP addresses, usage data and other non-personal information about your computer or device (such as browser type and operating system) to provide you with relevant advertising. (YouTube Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

As such the fact that this information about users is available is not necessarily problematic; risks for users rather arise through the usage of this data, particularly when this information is disseminated to third parties. This content analysis illustrates that, in fact, around 90% of all commercial web 2.0 platforms are allowed to pass on aggregated information about users to third parties. Aggregated information includes all kinds of statistical data about users, which do not identify an individual personally. This kind of information is thus ranging from site usage patterns to sociodemographic information to information about social relationships with other users, etc. Furthermore, according to this study up to 63% of all commercial web 2.0 platforms even sell information that identifies an individual personally.

The majority of all commercial platforms allow third-party advertising companies to place cookies on the computer of users in order to collect information about them for advertising purposes. The ways in which these third parties deal with user information is not described in the platforms’ own terms of use, but subject to the third party’s terms of service. This is for example pointed out in the Fotolog privacy policy:

In some cases, our business partners may use cookies on our site. For example, an advertiser like Google may place a cookie on your computer to keep track of what country you are from so they show ads in the correct language. Fotolog has no access to or control over these cookies. (Fotolog Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

Whereas in terms of profit, personalized advertising is beneficial for advertisers (because it increases the effectiveness of advertising) as well as for the owners of web 2.0 platforms (because it allows them to charge higher advertising rates and to sell user information), it brings along a number of disadvantages and risks for web 2.0 users. These risks for users arise due to the fact that the creation of personalized ads requires detailed information about a consumer’s habits, attitudes, lifestyles, etc., that is, the surveillance of users. In the following three main undesirable consequences of consumer surveillance and personalized advertising for users are identified:

1. Negative consequences for the personal life of web 2.0 users:

The fact that web 2.0 users are surveilled and information about them is sold to third parties can have undesirable consequences for individual users. The available information about them, which is stored in databases, can be combined with information from other sources and can produce a detailed picture about the life of an individual. As the following quotation from the Netlog privacy policy illustrates, advertising networks can access many different web 2.0 sites and are thus able and allowed to combine information from various sources. This quotation furthermore shows the limited reach of terms of services and privacy policies: Third parties are indeed allowed to access user information on a specific web 2.0 site; however, the ways that they deal with this information is not covered by the specific website’s privacy policy, but rather is subject to the third party’s policies.

Your online profile will also be used by other websites in the BlueLitihium Network to provide you with targeted advertising. These websites may combine the personal data collected on the Netlog website with personal data collected from other sources. Consult the privacy policies of our advertisement providers to learn more about how your personal data are used by them. (Netlog Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

It therefore becomes almost impossible to determine which information is collected and to whom it is disseminated. The more commercial web 2.0 applications an individual is using, the more likely it is that widespread information about him/her is available and disseminated to various companies. This is problematic because it is not determinable for what purposes this information will be used and if the individual agrees to all these uses of his/her data. The possible undesirable consequences for an individual are manifold and range from political surveillance to professional and economic disadvantages due to employer surveillance to disadvantages regarding health or life insurance. In the light of newly developed mobile applications such as the face recognizer “Recognizr” from the software company The Astonishing Tribe (TAT), the fact that a broad range of information about individuals is stored in databases becomes increasingly threatening. “Recognizr” is a facial recognition application for mobile phones, which retrieves information about strangers from web 2.0 sites if they are photographed with a cameraphone. Thus this application potentially allows the identification of every web 2.0 user everywhere and any time. It also allows instant retrieval of a broad range of information about users from their 2.0 profiles simply by taking a user’s picture. In economic contexts, such an application could be used as another tool for enhancing capital accumulation by personalizing shop offers according to a person’s shopping habits, which can be instantly retrieved from a person’s web 2.0 profiles. In political contexts, it can have negative effects on individuals (e.g., the identification of protesters during a demonstration) and as a consequence limit the right to political opposition and protest. At the moment “Recognizr” only allows identifying individuals who are using this application as well (The Astonishing Tribe, 2010, online). Nevertheless it could potentially also be used for identifying persons that have not given their permission.

2. Exploitation of web 2.0 users:

In addition to potentially causing personal disadvantages for individuals, a second problem is that realizing profit out of personalized advertising also constitutes a form of exploitation of web 2.0 users (Fuchs 2010). Christian Fuchs (2010) has pointed out that on web 2.0 sites, users are productive workers because they create media content and usage data that result in profit. Without this content, web 2.0 sites would not be attractive to users, and the owners of these sites would therefore be unable to sell user data for advertising purposes and no profit could be generated. Tiziana Terranova has in this context spoken of “unwaged, enjoyed and exploited, free labor” (Terranova 2000, 33).

Advertising on web 2.0 platform is only rewarding for advertisers if the site’s users form an attractive demographic audience of potential consumers. Thus only if a platform has enough users, will advertisers be willing to buy space for ads. User data can only be sold when enough users leave their information on the site. This shows that without the work done by users who produce and upload content, it would be impossible to generate profit. Thus the owners of web 2.0 platforms exploit the labour power of users in order to satisfy their profit interests.

3. Manipulation and the reinforcement of a consumer culture:

Another undesirable consequence of this web 2.0 business model is that users are permanently confronted and annoyed with ads that try to foster the illusion that individuality and authenticity can be achieved by buying certain consumer products. Because most web 2.0 sites are commercial and employ an advertising-based business model, for users it becomes nearly impossible to escape from this atmosphere of consumption.

As the terms of use and privacy statements of most commercial web 2.0 platforms ensure that platforms owners are allowed to sell space for advertisements and user data to third parties, commercial web 2.0 users do not have any way to protect themselves from these undesirable consequences unless they refrain from using these commercial platforms. If users do not agree to the terms set by platform owners they are excluded from using their services. The results of this content analysis confirm that the terms of use allow the platform owners to force users to provide data about themselves by threat of exclusion. This unequal power relation between platform users and owners, which puts platform owners in the position to set the terms of the contract, is expressed in the following passage of Google’s privacy policy:

You can decline to submit personal information to any of our services, in which case Google may not be able to provide those services to you. (Google Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

The business practices of commercial web 2.0 providers do not only have undesirable consequences for the individual user, but also negatively affect society as a whole. Personalized advertising brings about a commodification of information because data are increasingly turned into a tradable commodity. The web 2.0 business model thus contributes to the commercialization of the Internet on the one hand because the omnipresence of advertising creates an atmosphere of consumption and, on the other hand, because this business model is based on the transformation of user information into commodities.

Personalized advertising has undesirable consequences for web 2.0 users and society as a whole, but it is beneficial for business interests of the owners of commercial web 2.0 platforms and advertisers. It allows owners to charge higher advertising rates, and it increases the effectiveness of advertisers’ marketing campaigns.

This unequal relation of advantages for owners and advertisers and disadvantages for users and society is not reflected in the terms of use and privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms. These documents rather aim at creating the illusion that personalized advertising is beneficial for web 2.0 users. The language used obviously intends to approach users in a personal way to create an atmosphere of friendship; but these documents ideologically mask the unequal power relation between owners, who design the terms of use in a way that allows them to generate profit out of users’ work and information, and users, who have to accept them. In this spirit Hyves.com for example writes

Hyves consists of a network of friends. We deal with your information as you would expect from friends. So Hyves takes your privacy very seriously and will deal with your information with due care. (Hyves Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

Furthermore the language of the terms of use and privacy statements describes personalized advertising as beneficial for web 2.0 users, because it will ensure that users only receive “relevant and useful” information, “improve user experience”, and “prevent” them from seeing uninteresting ads. YouTube for example writes:

YouTube strives to provide you with relevant and useful advertising and we may use the DoubleClick cookie, as well as other third-party ad-serving systems, to do so. (YouTube Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

Similarly Facebook emphasizes that personalized advertising benefits the user:

Facebook may use information in your profile without identifying you as an individual to third parties. We do this for purposes such as aggregating how many people in a network like a band or movie and personalizing advertisements and promotions so that we can provide you Facebook. We believe this benefits you. You can know more about the world around you and, where there are advertisements, they’re more likely to be interesting to you. (Facebook Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

The fact that in most privacy policies the word “selling” does not appear constitutes another aspect of the ideological character of the analyzed terms of use and privacy policies. Instead of “selling” the word “sharing” is used, which again reinforces the illusion of friendship and mutual benefits:

From time to time, Tagged may share the email address and/or other personally identifiable information of any registered user with third parties for marketing purposes. In addition, Tagged may share a registered user’s email address with third parties to target advertising and to improve user experience on Tagged’s pages in general. (Tagged Terms of Service, accessed on April 27, 2009)

The results of the content analysis confirm that the terms of use and privacy policies of commercial web 2.0 sites are designed to allow the owners widespread use of user information. At the same time, a qualitative reading of these documents shows that their language, style, and structure is confusing, misleading, ideological, or even manipulative. The main ideology, on which these statements rest, is one of friendship, of equality, of sharing, and of user benefits. They try to create the impression that the only aim of these platforms is to provide to its users an attractive high-quality service and experience that allows them to produce their own media content and to connect with friends. The fact that these platforms are owned by commercial companies that aim at increasing their profits by selling user information and space for advertisements remains hidden.

Apart from this ideological character, another problem concerning the privacy policies and terms of use of commercial web 2.0 platforms is their limited reach. Most platforms give third-party advertising companies access to user information. Nevertheless the privacy policies and terms of use of these platforms do not cover how third parties deal with user information. In fact these documents explicitly state that once data are handed over to a third party, the platform owners no longer have any control over further usage of this data. This fact can be illustrated with the following quotation from the privacy policy of Megaupload:

We use third-party advertising companies to serve ads when you visit our website. These companies may use information (not including your name, address, e-mail address or telephone number) about your visits to this and other websites in order not only to provide advertisements on this site and other sites about goods and services that may be of interest to you, but also to analyze, modify, and personalize advertising content on Megaupload.com. We do not have access to or control over any feature they may use, and the information practices of these advertisers are not covered by this Privacy Policy. (Megaupload Privacy Policy, accessed on April 27, 2009)

This qualitative analysis shows that the privacy statements and terms of use of commercial web 2.0 platforms ideologically mask the unequal power relationship between platform owners and users, conceal the profit motivations of platform owners, and downplay the risks for users that arise due to personalized advertising. Some privacy statements and terms of use even create the impression that platform owners intentionally want to delude users.

In summary, the analysis and interpretation of the results of the conducted content analysis shows that the main hypothesis underlying this study can be confirmed:

H: The terms of use and privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms are designed to allow the owners of these platforms to exploit user data for the purpose of capital accumulation.

This case study of consumer surveillance on web 2.0 has shown that contemporary web 2.0 mainly is a commercial web 2.0 and that the business model of web 2.0 corporations rests on economic surveillance. The terms of use and privacy statements of commercial web 2.0 platforms allow the widespread use of user data in a way that supports the profit interests of platform owners. The business model of most commercial web 2.0 platforms is based on personalized advertising. Capital is accumulated by selling space for advertisements as well as by selling user data to third-party advertising companies. Furthermore these documents try to advance an ideology of friendship and mutual benefits and thus mask and downplay the unequal power relationship between platform owners and users. Whereas personalized advertising satisfies the profit interests of platform owners it has undesirable consequences for individual users as well as for society. Thus, in terms of reducing economic surveillance and its negative effects on individuals and society the search for and support of an alternative web 2.0 is of specific importance. The launch of the newly developed non-commercial social networking site Diaspora might be an important step into this direction: “Diaspora doesn’t expose your information to advertisers, or to games you play, or to other websites you visit”.5

1 See Forbes Magazine (2010): The Global 2000. http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/21/global-2000-leading-world-business-global-2000–10_land.html (accessed December 13, 2010).

2 xvideos.com [rank 107] and xnxx.com [163].

3 orkut.co.in [rank 54] and orkut.com [106] belong to orkut.com.br [11]; files.wordpress.com [127] belongs to wordpress.com [7]; and wikimedia.org [192] belongs to wikipedia.org [3].

4 The following 13 sites had to be excluded because of language issues: 2 Russian sites (vkontakte.ru [rank 28]; odnoklassniki.ru [48]); 6 Chinese sites (youku.com [53]; ku6.com [94]; kaixin001.com [110]; 56.com [116]; xiaonei.com [132]; people.com.cn [188]); 2 Japanese sites (mixi.jp [84]; nicovideo.jp [119]); 1 Taiwanese site (wretch.cc [97]); 1 Polish site (nasza-klasa.pl [100]); 1 Persian site (blogfa.com [179]).

5 See Diaspora: what is diaspora. http://blog.joindiaspora.com/what-is-diaspora.html (accessed on December 14, 2010).

Allen, Matthew. 2008. Web 2.0: an argument against convergence. First Monday 13 (3) http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2139/1946 (accessed June 20, 2010).

Andrejevic, Mark. 2002. The work of being watched: interactive Media and the explotation of self-disclosure. Critical Studies in Media Communication 19 (2): 230–248.

Ball, Kirstie. 2006. Organization, surveillance and the body: towards a politics of resistance. In Theorizing Surveillance: The panopticon and beyond, ed. David Lyon, 296–317. Portland, OR: Willan.

Ball, Kirstie and Frank Webster. 2003. The intensification of surveillance. In The intensification of surveillance, ed. Kirstie Ball and Frank Webster, 1–16. London: Pluto.

Beer, David and Roger Burrows. 2007. Sociology and, of and in web 2.0: some initial considerations. Sociological Research Online 12 (5). http://www.socresonline.org.uk/12/5/17.html (accessed June 20, 2010).

Bogard, William. 2006. Welcome to the society of control. In Surveillance and visibility, ed. Kevin Haggerty and Richard Ericson, 4–25. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bogolicos, Nico. 2007. The perception of economic risks arising from the potential vulnerability of electronic commercial media to interception. In Handbook of technology management in public administration, ed. David Greisler and Stupak, 583–600. Boca Raton: CRC.

boyd, dannah. 2007. The significance of social software. In BlogTalks reloaded: Social software research & cases, ed. Thomas Burg and Jan Schmidt, 15–13. Norderstedt: Books on Demand.

Bruns, Axel. 2007. Produsage, generation C, and their effects on the democratic process. Media in Transition 5. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/7521/ (accessed September 14, 2009).

Campbell, Edward John and Matt Carlson. 2002. Panopticon.com: online surveillance and the commodification of privacy. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 46 (4): 586–606.

Charters, Darren. 2002. Electronic monitoring and privacy issues in business-marketing: the ethics of the DoubleClick experience. Journal of Business Ethics 35: 243–254.

Clarke, Roger. 1988. Information technology and data veillance. Communications of the ACM 31 (5): 498–512.

Coates, Tom. 2005. An addendum to a definition of social software. http://www.plasticbag.org/archives/2005/01/an_addendum_to_a_definition_of_social_software/ (accessed September 14, 2009).

Cormode, Graham and Balachander Krishnamurthy. 2008. Key differences between web 1.0 and web 2.0. First Monday 13 (3). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2125/1972 (accessed September 14, 2009).

Fernback, Jan and Zizi Papacharissi. 2007. Online privacy as legal safeguard: the relationship among consumer, online portal, and privacy policies. New Media and Society 9 (5): 715–734.

Foucault, Michelle. 1977/2007. Panopticism. In The surveillance studies reader, ed. Sean P. Hier and Josh Greenberg, 67–76. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Fuchs, Christian. 2008. Internet and society: Social theory in the information age. New York: Routledge.

Fuchs, Christian. 2009a. Social networking sites and the surveillance society. Salzburg/Vienna: Unified Theory of Information Research Group.

Fuchs, Christian. 2009b. A contribution to the critique of the political economy of the Internet. European Journal of Communication 24 (1): 69–87.

Fuchs, Christian. 2010. Labor in informational capitalism and on the Internet. The Information Society 26 (3): 179–196.

Gandy, Oscar. 1993. The panoptic sort: A political economy of personal information. Boulder: Westview.

Haggerty, Kevin and David Lyon. 2006. Tear down the walls. In Theorizing surveillance: The panopticon and beyond, 23–45. Portland, OR: Willan.

Harrison, Teresa M. and Brea Barthel. 2009. Wielding new media in web 2.0:exploring the history of engagement with the collaborative construction of media products. New Media & Society 11 (1): 155–178.

Hier, Sean P. and Josh Greenberg. 2007. Glossary of terms. In The surveillance studies reader, ed. Sean Hier and Josh Greenberg, 378–381. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Jarrett, Kylie. 2008. Interactivity is evil: A critical investigation of Web 2.0. First Monday 13 (3). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2140/1947 (accessed September 14, 2009).

Kortzfleisch, Harald, Ines Mergel, Shakib Manouchehri, and Mario Schaarschmidt. 2008. Corporate web 2.0 applications. In Web 2.0, ed. Berthold Hass, Gianfranco Walsh, and Thomas Kilian, 73–87. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer.

Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lyon, David. 2003. Surveillance as social sorting: computer codes and mobile bodies. In Surveillance as social sorting, ed. David Lyon, 13–30. London: Routledge.

Lyon, David. 2007. Everyday surveillance: personal data and social classifications. In The surveillance studies reader, ed. Sean P. Hier and Josh Greenberg, 136–146. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Mathiesen, Thomas. 1997. The viewer society: Michel Foucault’s panopticon revisited. Theoretical Criminology 1: 215–237.

Ogura, Toshimaru. 2006. Electronic government and surveillance-oriented society. In Theorizing surveillance: The panopticon and beyond, ed. David Lyon, 270–295. Portland, OR: Willan.

O’ Reilly, Tim. 2005. What is web 2.0?: design patterns and business models for the next generation of software. http://oreilly.com/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html (accessed September 14, 2009).

Papacharissi, Zizi and Jan Fernback. 2005. Online privacy and consumer protection: an analysis of portal privacy statements 49 (3): 259–281.

Petersen, Soren Mark. 2008. Loser generated content: from participation to exploitation. First Monday 13 (3). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2141/1948 (accessed September 14, 2009).

Reis, Leslie Ann. 2007. Personally identifiable information. In Encyclopedia of privacy, ed. William G. Staples, 383–385. Westport/London: Greenwood.

Rule, James B. 1973/2007. Social control and modern social structure. In The surveillance studies reader, ed. Sean P. Hier and Josh Greenberg, 19–27. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Scholz, Trebor. 2008. Market ideology and the myths of Web 2.0. First Monday 13 (3). http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2138/1945 (accessed September 14, 2009).

Smythe, Dallas. 1981/2006. On the audience commodity and its work. In Media and cultural studies, ed. Meenakshi Gigi Durham and Douglas Kellner. Malden: Blackwell.

Solove, Daniel. 2004. The digital person: Technology and privacy in the information age. New York: New York University Press.

Starke-Meyerring, Doreen and Laura Gurak. 2007. Internet. In Encyclopedia of privacy, ed. William G. Staples, 297–310. Westport/London: Greenwood.

The Astonishing Tribe. 2010. Recognizr covered by FOX News and SC Magazine. Press Release. May 3, 2010. http://www.tat.se/site/media/news_1.php?newsItem=42 (accessed June 20, 2010).

Toffler, Alvin. 1980. The third wave. New York: Bantam.

Turow, Joseph. 2006. Cracking the consumer code: advertisers, anxiety, and surveillance in the digital age. In The new politics of surveillance and visibility, ed. Kevin Haggerty and Richard Ericson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Van Dicjk, José. 2009. Users like you? theorizing agency in user-generated content. Media, Culture & Society 31 (1): 41–58.

Wall, David. 2006. Surveillant internet technologies and the growth in information in information capitalism: spams and public trust in the information society. In The new politics of surveillance and visibility, ed. Kevin Haggerty and Richard Ericson, 240–261. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.