Bigness ruins everything.

—Amish carpenter

Human interaction is shaped not only by cultural beliefs and symbols but also by patterns of social behavior. Societies, like buildings, have distinctive architectural styles. Like blocks of Legos, social relations can be arranged in many different ways. In some societies males dominate, in others females do, and in still others neither does. The organizational pattern of each society creates a distinctive social architecture.

Growing up in an Amish family with eighty first cousins nearby is quite different from living in a nuclear family with two cousins living a thousand miles apart. Child-rearing practices in Amish families, where both parents often work at home, differ radically from dual-career families whose children play in daycare. A society’s architectural design shapes human behavior in profound ways. What features distinguish the social architecture of Amish society? What is the organizational shape of Gelassenheit?

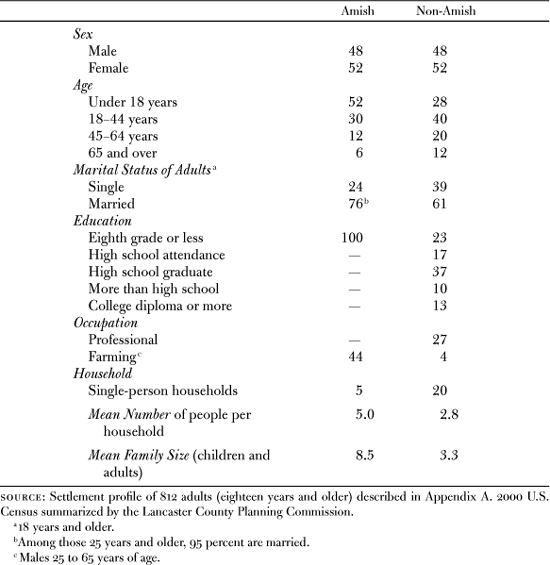

Demographic factors—birth rates, mobility, marital status, and family size—are the building blocks of a society’s social structure. Table 4.1 compares the demographic differences between the Amish and non-Amish population in Lancaster County. The Amish are more likely than their neighbors to marry, live in large households, terminate school early, and engage in farming. A striking feature of Amish society is the large proportion (52 percent) of people under eighteen years of age. With only 6 percent of its members over sixty-five, Amish life tilts toward child rearing. Schools, rather than retirement villages, dominate the social landscape.

TABLE 4.1

Demographic Characteristics of Lancaster County Amish and Non-Amish Populations (in percentages)

The individualization of modern society, reflected in spiraling percentages of single people and single-parent homes, is largely absent from Amish society. Whatever the Amish do, they do together. Only 5 percent of Amish households are single-person units, compared to 20 percent for the county. Moreover, virtually all of the single-person households adjoin other Amish homes. Several households are often on the same property. Many double households include a small adjacent Grossdaadi house for the grandparents. Five people live in the average Amish household—nearly double the county rate of 2.8 per household. The majority of Amish reside in a household with a half dozen other people or at least live adjacent to one. Moreover, additional members of the extended family live just across the road or beyond the next field.

Age and gender roles are essential building blocks in Amish society. The Amish identify four stages of childhood: babies, little children, scholars, and young people.1 The term little children is used for children from the time they begin walking until they enter school. Children between the ages of six and fifteen are often called scholars. Young people from mid-teens to marriage explore their independence by joining informal youth groups called “gangs” that crisscross the settlement.

Social power increases with age. In a rural society where children follow the occupations of parents, the elderly provide valuable advice. Younger generations turn to them for wisdom in treating an earache, making pie dough, training a horse, predicting a frost, or designing a quilt. In a slowly changing society, the seasoned judgment of elders is esteemed, unlike fast-paced societies where children teach new technologies to their parents. The power of age also molds the life of the church, where the words of an older minister count more than those of a younger one. The chairman of the ordained leaders in the settlement is traditionally an older bishop with the longest tenure in that office. Wisdom accumulated by experience, rather than by professional or technical competence, is the root of power in Amish society.

Although power increases with age, gender distinctions produce inequality. In the realm of church, work, and community, the male voice carries greater influence. Age and gender create a patriarchy that gives older men the greatest clout and younger females the least. One mother said, “How people see women hasn’t changed that much. We’re still seen as second class. Of course, we really emphasize family life. And when you think about how much the children of divorce suffer—that’s all such a mess. We emphasize family life. That’s what is important to us, to have good family relations. But I don’t think women are becoming more free in our community. That’s how it seems to me.”

Amish families are organized around traditional gender roles. Although in Amish marriages, like others, various power equations emerge depending on the personalities of the partners, the husband is seen as the spiritual head of the home. He is responsible for its religious welfare and usually has the final word on matters related to the church and the outside world. Among farm families, husbands organize the farming operation and supervise the work of children in barns and fields. Many husbands assist their wives with gardening, lawn care, and child care, but others do little. Husbands rarely help with household work—washing, cooking, canning, sewing, mending, cleaning. The visible authority of the husband varies by household, but Amish society is primarily patriarchal and vests final authority for moral and social life in the male role.

The church teaches that, in the divine order of things, wives are expected to submit to their husband’s authority. This theme is emphasized in the wedding vows.2 A fifty-year-old woman noted, “I think maybe our wedding sermons today are easier on the woman’s role in the home. I know a lot of women have felt put down in the wedding sermon. I know some of the preachers try harder these days to say kinder things about the woman’s role in the home.”

Entrusted with the responsibility of raising a large family, many Amish women are very efficient managers. Married women rarely have full-time jobs outside the home. In addition to providing child care, the wife normally oversees the garden, preserves food, cooks, cleans, washes, sews, and supervises yard work. An Amish woman’s garden and flowers are her kingdom.3 Many women mow their lawns with push mowers, without engines. Moreover, those who live on a farm often assist with barn chores—feeding calves, milking cows, and gathering eggs—as well as harvesting crops and vegetables. Others do clerical work or bookkeeping in their husband’s shop. The work is hard and the hours long, but there is quiet satisfaction in nourishing thriving families, tending productive gardens, baking pies, sewing colorful quilts, and watching dozens of grandchildren find their place in the Amish world. One woman, who had baked fifty-six pies in preparation for the lunch following church at her home said, “It’s no big deal because the children always help.”

Mingled with the work are many pleasant moments of reprieve—a quilting party, a “frolic,” a sale, a wedding, and, of course, perpetual visiting. In addition to the endless chores, one woman said, “we sing, laugh, smile, and go through mid-life crises. We are real. Some of us even believe in women’s rights, anyhow if we know what they are.”

Women vote in church business meetings and nominate men for ministerial duties. They do not, however, participate in the community’s formal power structure. They cannot be ordained, nor do they serve as members of special committees. Virtually all Amish schoolteachers are single women, but they too are on the fringe of the formal leadership structure.4

One of the remarkable changes in gender relations is the growing number of women who own and operate businesses. About 15 percent of the hundreds of Amish businesses are operated by women. In some cases husbands work for their wives who are the owners. Gender influences shape business involvements. Women tend to operate food, craft, and quilt industries but not metal, woodworking, or construction firms. An attorney who works with both Old Order Mennonites and Amish noted that Amish women are much more involved in real estate transactions and much more likely to speak up at a real estate settlement.5

Without the prod of market forces, labor-saving devices have come more slowly in the kitchen than in the barn. The ban on electricity has, of course, eliminated many appliances from Amish homes. Even with ample help from children, it is a challenge to manage a household of eight or more people without electric mixers, blenders, dishwashers, microwave ovens, and clothes dryers. Increasingly, washing machines and sewing machines are powered by air pressure as are mixers, beaters, and blenders. The kitchens and bathrooms in newer Amish homes have a modern appearance, with lovely state-of-the-art cabinetry. Contemporary-looking gas stoves and refrigerators have eliminated old wood cookstoves and iceboxes, although kerosene space heaters are still widely used. Permanent-press fabrics, disposable diapers, cake mixes, and cleaning detergents have lightened household work in many ways. Nevertheless, some Amish women think the acceptance of labor-saving devices has favored the men. One young woman described the tilted balance of power this way:

The joke among us women is that the men make the rules so that’s why more modern things are permitted in the barn than in the house. The women have no say in the rules. Actually, I think the main reason is the men make the living and we don’t make a living in the house. So you have to go along with what they need out there. You know, if the public health laws call for it, you have to have it. In the house you don’t. Even my Dad says that he thinks the Amish women get the brunt of it all around. They have so many children and are expected to help out with the milking. Some help for two hours with the milking from beginning to end and they have five little children. That’s all right if a man helps them in the house and puts the children to bed, but a lot of them don’t. I don’t think it’s fair that we have the push mowers to mow the lawns with. It is hard work on some of these lawns. We keep saying that if the men would mow the lawns there would be engines on them, and I am sure there would be. Years ago they used to mow the hay fields with an old horse mower, but now they have engines on the field mowers so it goes easier for the horses, but they don’t care about the women.

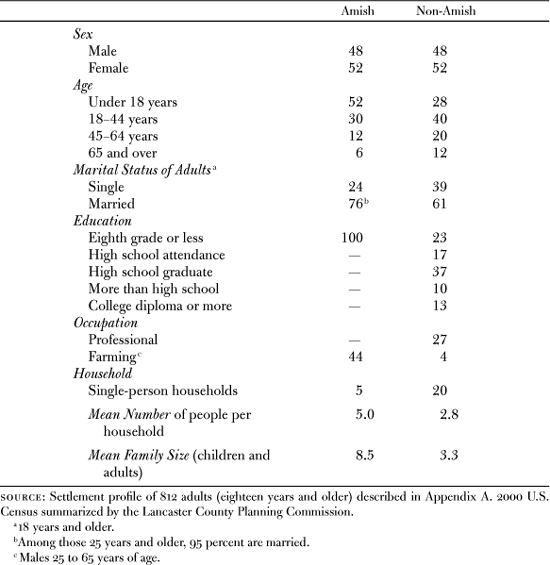

Using horses to pull a modern hay baler, a family works together to harvest a new crop of hay.

Another woman declared that the church accepted gasoline-powered weed trimmers “because the men needed to trim their fence posts, which left the women feeling, at last, we may need to fight for our rights!” These statements show the growing sensitivity of some women to gender roles. Amish women are not liberated by modern standards, but many find fulfillment in durable, defined roles within their extended families. They know who they are and what is expected of them. One husband said: “A wife is not a servant; she is queen and the husband is the king.”

Marriage in Amish society accents not romance but the importance of a loving, durable partnership. Many Amish couples experience a partnership in their marriage that was typical of preindustrial, rural life before the rise of factory work. One woman described the joy of a good partnership as she drove the horses pulling the hay baler while her husband stacked the bales on a wagon in the face of an impending storm: “The machinery all worked, and the green hay smelled so good, and the horses felt brisk, and we were in a hurry. It’s a wonderful feeling at a time like that. We two, the four horses, and the baler all working harmoniously together, with the wind grabbing at our clothes and manes, as if to say, it’s helping us along.”6

Several Amish women offered the following recipe on “How to Preserve a Husband” from the back of a cookbook they had printed for distribution.

First use care and find one not too young, but one that is tender and a healthy growth. Make your selection carefully and let it be final. Otherwise, they will not keep. Like wine, they improve with age. Do not pickle or put in hot water. This will make them sour.

Prepare as follows:

Sweeten with smiles according to the variety. The sour, bitter kind are improved by a pinch of salt of common sense. Spice with patience. Wrap well in a mantle of charity. Preserve over a good fire of steady devotion. Serve with peaches and cream. The poorest varieties may be improved by this process and will keep for years in any climate.7

As largely self-employed people, Amish women, ironically, have greater control over their work and daily affairs than do many other women who hold full-time clerical and nonprofessional jobs. Unfettered by the pressure to succeed in a career, Amish women devote their energies to family living. While their work is hard, it is their work, and it brings as much satisfaction as a professional career, if not more. Amish women view professional women working away from home and children as a distortion of God’s created order that can only lead to divorce, unruly children, and family disruption. Their role models are other Amish women who have managed their families well. Happiness, after all, depends on one’s values and social point of reference. All things considered, within their context Amish women express high levels of social and personal satisfaction. Indeed, women in modern society, often burdened by conflicting role expectations and professional pressures to excel, may experience greater anxiety over their roles than many Amish women.

When Amish leaders tally up the size of their churches, they count families, not individuals.8 The family, the keystone of Amish society, is large in both size and influence. Most Amish youth marry between the ages of nineteen and twenty-five, on a Tuesday or Thursday in November, as the harvest season comes to a close. Marriage is highly esteemed, and raising a family is the professional career of Amish adults. Nine out of ten adults are married.

Marriage vows are rarely broken. An Amish woman explained, “I don’t think us Amish should allow divorce. I think you need to work things out. That’s how we’re taught. We’re taught over and over, when you decide to marry, you will spend the rest of your life with this person. You need to work it out.” There are, of course, some de facto divorces, and in rare cases couples may live apart, but divorce is taboo. People who initiate divorce are automatically excommunicated. If a husband divorces his wife and leaves the community, she can remain within the church but cannot remarry until he dies.

Many Amish babies are born at home and welcomed by siblings.

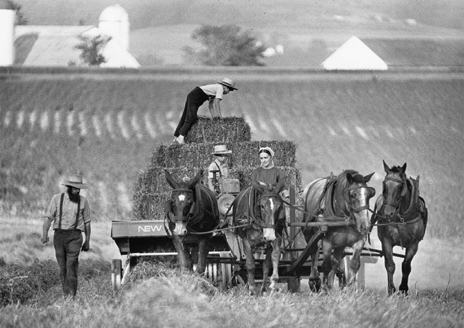

Believing that large families are a blessing from God, couples yield to the laws of nature and produce sizeable families.9 Although the church informally frowns on birth control, some couples do use artificial and natural means to regulate the arrival of newborns in one way or another. Despite such attempts, Amish culture continues to value large families. One young mother, after giving birth to four children, said with a measure of satisfaction, “Well, I’m half done now.” Including parents and children, the average family has 8.5 members, compared to the county norm of 3.3. By age forty-five, the typical Amish woman has given birth to 7.1 children, whereas her neighbors average 2.8. Death and disease reduce the number, yielding families that average 6.5 children. Slightly over 10 percent of Amish families have ten or more children. By the turn of the twenty-first century, about 1,100 new babies were arriving in the Lancaster settlement every year.

While Amish children are numerous, the cost of their upbringing is relatively low. There are no swimming pool memberships, tennis lessons, stereos, computer games, summer camps, sports cars, college tuition, or designer clothes to buy. Children assume daily chores by five or six years of age, and their responsibilities in the barn and house grow rapidly. They are seen not as economic burdens but as blessings from the Lord and as new members who will contribute their share to the family economy. Even with the growth of businesses, the labor provided by children is an economic asset to the community.

The power of the family extends beyond sheer numbers. The family’s scope and influence dwarfs that of the modern nuclear family. Amish life is spent in the context of the family. In contemporary families social functions from birth to death, from eating to leisure, often leave the home. In contrast, Amish activities are anchored at home. Children are usually born there. They play at home and walk to school. By age fourteen, children work full-time in the home, shop, or farm. They are taught by their extended family, not by television, babysitters, popular magazines, or daycare teachers. Young couples are married at home. Church services rotate from home to home. Most meals are eaten at home. Adults work at home or nearby. Plentiful recreational activities, such as swimming, sledding, skating, softball, volleyball, and corner ball, centered near home, have no admission fees.

FIGURE 4.1 Births, Baptisms, and Weddings in the Lancaster Settlement, 1990–2000. Source: The Diary

Social events, singings, “Sisters Days,” quilting parties, and work “frolics” are staged in homes. Occasionally, men will slip away for a day of deep sea fishing or several days of hunting, but the majority of Amish recreation is close to home and nature. In the past, vacations to “get away from home” were rare, but increasingly many couples take “trips” of several weeks to other settlements. Others will take shorter trips to historical sites, the zoo, or a flower show. A few older couples vacation in Florida for several winter months at Pinecraft, a small Amish village that attracts retirees from many settlements.10 Out-of-state travel by van, train, or bus (but not air) often includes visiting in other settlements.

Despite increased traveling, home remains the site for many activities. Although the Amish do buy groceries and commercial products, much of their food is homegrown, and much clothing is homemade. Even table games are homemade. Instead of eating at a pizza shop, they will more likely make pizza at home. Men’s hair is cut at home. Time and money spent on shopping trips are thus minuscule compared to the American norm. There are no visits to the health spa, pet parlor, hairdresser, car wash, or sports stadium, and thus there is more time for “home work” and “home play.” Although the Amish use modern medicines, they are more likely to rely on home remedies, natural foods, and herbs; and they only visit a doctor as a last resort. Retirement occurs at home. Funerals are held at home, and the deceased are buried in nearby cemeteries. All of these centripetal forces pull the Amish homeward most of the time. Staying home is not a dreaded experience of isolation; it means being immersed in the chatter, work, and play of the extended family.

Despite their commitment to home, recent trends are pulling some activities away. Less food and clothing and fewer toys and products are made at home. More commercial games and toys are bought. More couples are taking extended trips away from home. Nevertheless, by contemporary standards most of the dramas of Amish life are staged at home or very nearby. Very few life-cycle functions have left their homes, and in this regard the Amish stand apart from the modern world.

In contrast to the mobility of contemporary families, Amish families are tied to a geographical area and anchored in a large extended family. Many people live on or within several miles of their childhood homestead. Others may live as far as fifteen miles away. After a new family settles down in a residence, it typically remains there for life. Thus geographical and family roots run very deep. A mother of six children explained that all of them live within Lancaster County and that she delights in visiting her thirty-six grandchildren at least once a month. Those living on the other side of her house, of course, she sees every day. With families averaging nearly seven children, it is not unusual for a couple to have forty-five grandchildren. A typical child will have two dozen aunts and uncles and as many as eighty first cousins. Although some of these relatives are scattered on the settlement’s fringe, many live within a few miles of home. To be Amish is to have a niche, a secure place in a thick web of family ties. Embroidered or painted rosters of extended family names hang on the walls of every Amish home—a constant reminder of the individual’s notch in the family tree.

A modern kitchen in a contemporary Amish home. A gas refrigerator chills food and gas-pressured lamps provide light.

The Amish families who live near each other form a church district or congregation—the primary social unit beyond the family. In the Lancaster settlement the number of households per church district ranges from twenty to fifty, with an average of thirty-four. With many double households, the average district has about twenty major family units. Some 80 adults and 90 youth under nineteen years of age give the typical district a total of 170 people.11 Church services are held in homes, and as congregations grow, they divide.

A district’s geographical size varies with the density of the Amish population. On the edge of the settlement, church districts stretch twelve miles from side to side, but in the settlement’s hub they shrink dramatically. Families in small geographic districts, often within a half-mile of each other, are able to walk to services. In recent years the physical size of church districts has shrunk because more people have gone into nonfarm occupations, which has reduced the spread of land required for a district.

Roads and streams form the boundaries of most church districts. Like members of a traditional parish, the Amish participate in the church district that encircles their home. The members of a district worship together every other week. Sometimes they attend the services of adjoining districts on the “off Sunday” of their congregation. Residents of one district, however, cannot become members of another one unless they move into its territory. Because there are no church buildings, the homes of members become the gathering sites not only for worship but also for socializing.

The church district is the social and ceremonial unit of the Amish world. Self-contained and autonomous, dozens of congregations are linked together by a network of ordained leaders and extended families. Baptisms, weddings, excommunications, and funerals take place within the district. Fellowship meals after worship and other activities bring members of the district together. Members visit, worship, and work together in a dense ethnic network. In short, the church district is family, factory, church, club, and precinct all bundled into a neighborhood parish.

Districts ordain their own leaders and, on the recommendation of their bishop, have the power to excommunicate members. Errant members must confess major sins publicly before other members. Local congregations, under the leadership of their bishop, vary in their interpretation of religious regulations. Some districts permit power lawn mowers and others do not. Some allow fancier furniture than others. Decisions to aid other districts financially and to participate in community-wide Amish programs are made by the local district. Congregational votes are taken on recommendations of the bishop. John Hostetler has aptly called this system a “patriarchal democracy.”12 Although each member has a vote, it is usually a vote to accept or reject the bishop’s recommendation.

Because families live so close together, many members of a district are often related. Throughout the settlement six surnames—Stoltzfus, King, Fisher, Beiler, Esh, and Lapp—account for over 70 percent of the households. The rank order of surnames is displayed in Table 4.2. Kinship networks are dense both within and between church districts, and there are many repetitious names. For example, there are 115 Samuel Stoltzfuses, 115 Mary Stoltzfuses, 56 Mary Kings, 52 John Kings, and so on in the Lancaster settlement. One rural mail carrier had to distinguish among sixty Stoltzfus families. Moreover, he had three Amos E. Stoltzfuses and three Elam S. Stoltzfuses on the same route!

TABLE 4.2

Rank Order of Household Surnames

The frequency of similar names has led to many nicknames based on physical traits, personal habits, or an unusual incident related to the person. The nicknames tend to follow patriarchal lines across several generations. “Cookie Abner” derives from a teenage eating incident, and “See more Levi” has very large eyes. “Pud Reuben” was a heavyset man who was nicknamed “Pud.” His children became Pud’s Aaron, or Pud’s Sally. Families sometimes develop nicknames—“the Squeakies,” “the Piggys” (who live near Piggy’s Pond), “the Mo-boys,” “the Izzies,” “the Jackies,” and “the Butchers” to name a few of hundreds. One woman said, “I’m a Bootah. That goes way back to my great-grandparents. When they got their marriage license, the clerk wasn’t too bright, and she wrote their names ‘Bootah’ (butter) instead of Beiler. So ever since we’ve been the Bootahs. I think our children will be Squeakies because the nicknames usually follow the man’s line, but they don’t always pass from one generation to the next.”

The leadership team in each district typically consists of a bishop, two or three ministers, and a deacon.13 The leaders are viewed as servants of both God and the congregation. In fact, their German titles translate literally as ‘servant.’14 A bishop serves as the spiritual head and typically presides over two districts.15 One district is the bishop’s “home” congregation. Congregations meet every other week, and thus their bishop is able to attend each of their regular meetings. The bishop officiates at baptisms, weddings, communions, funerals, and members’ meetings. As spiritual head of the leadership team, he interprets and enforces church regulations. If disobedience or conflict arises, he is responsible to resolve it. Family and church networks are often entangled in controversies of one sort or another that require delicate diplomacy.

The bishop is responsible for recommending excommunication or, as the case may be, the reinstatement of penitent members. While considerable authority is vested in the office of bishop, final decisions to excommunicate or reinstate members require a congregational vote. Diverse personalities among the bishops lead to diverse interpretations of rules. Some leaders are “open-minded,” whereas others take firm doctrinaire positions. Some are stern, and others are loving and gentle. The bishop is the incarnate symbol of church authority. One member remarked that every time she sees a policeman, he “reminds me of a bishop.” She added, however, that her bishop is a kind person, more concerned about the inner spiritual life of people than about outward regulations.

If the office of bishop is vacated by death or illness, a nearby bishop is given temporary oversight of the congregation. Eventually one of the ministers from the two congregations is ordained bishop by the biblical custom of “casting lots.” The ordination of a bishop may be delayed several years if the eligible ministers are too young or inexperienced. A senior bishop explained that he prefers to ordain bishops who have demonstrated their ability to raise a family dedicated to the church. Plans to ordain a bishop are approved by the local congregation as well as by the settlement-wide Bishops’ Meeting.

The minister, or preacher, fills the second leadership role in the local district. A congregation usually has two and sometimes three preachers, depending on their age and health. One of them serves as the lead minister, working closely with the bishop to give spiritual direction to the congregation. In addition to general leadership, ministers preach long sermons without the aid of notes. Without professional credentials or special training, ministers are selected from within the congregation and serve unpaid for life. They earn their own living by farming, carpentry, or other related occupations, including business.

Each congregation has a deacon whose public duties are limited to reading Scripture and prayers in worship services. He supervises an “alms fund” and attends to the material needs of families. The deacon assists with baptism and communion and carries responsibility for reproving wayward members. At the request of the bishop, the deacon, often accompanied by a minister, visits members who have violated church regulations. The outcome of the visit is reported to the bishop, who then takes appropriate action. The deacon also carries messages of excommunication or reinstatement to members from the bishop. One bishop called this aspect of the deacon’s role “the dirty work.”

The deacon also represents the congregation when young couples plan to marry. The groom brings a church letter of “good standing” from his deacon to the deacon of the bride’s congregation, who then meets with her to verify the plans for matrimony. The bride’s deacon then announces, or “publishes,” the date of the wedding in the local congregation. The deacon does not arrange marriages, but he does symbolize the church’s supervision of them. The bishop, ministers, and deacon function as an informal leadership team that guides and coordinates the activities of the local district.

The rotation of worship services from home to home shapes Amish identity and forms the bedrock of their social organization. This distinctive feature has bolstered the strength of their community. While the Old Order Amish share some cultural traits with other Plain people in the region, the Amish are set apart because they are not “meetinghouse” people. Their mobile “sanctuary” distinguishes them from Old Order Mennonites, who worship in meetinghouses. The Amish view a permanent church building as a symbol of worldliness, a view that goes back to the Anabaptist rejection of cathedrals in Europe.

At about the time of the Civil War, some Amish were tempted to use church buildings. Beginning in 1862 a series of national Ministers’ Meetings grappled with, among other things, lightning rods, insurance, photographs, and holding worship services in meetinghouses.16 Few Lancaster bishops participated in these meetings because they feared that liberal changes in the Midwest would drift eastward and stir up controversy at home. Their fears were not in vain.

Progressive-minded members in two districts of eastern Lancaster County began pressing for changes. The internal strife forced a stalemate that delayed the observance of communion in one congregation for seven years (1870–77). The discord came to a head in the late fall of 1876 when preacher Gideon Stoltzfus in the lower Pequea district was “silenced” from preaching by his bishop. He was charged with fellowshipping with liberal Amish in the Midwest. Eventually, about two-thirds of his district, some seventy-five progressive members, left the Old Order Amish and formed what later became a Mennonite congregation. Within several years, the progressives fulfilled the Old Order’s worst fears by building a meetinghouse.

A few miles to the east and a few months later, in the spring of 1877, a similar division erupted in the Conestoga district, leaving only eight families with the Old Order Amish. And as the sages predicted, the progressives in that area also erected a meetinghouse by 1882.17 These ruptures in two Lancaster districts within six months stunned the small Amish community, which at that time contained only six districts and less than five hundred members.

Thus 1877 marks a pivotal point in the Amish saga—a landmark that still casts a shadow over Amish consciousness. From that juncture to the present, the Old Order Amish have seen what happens when a progressive group drifts off and builds a meetinghouse. Eventually they hold Sunday school, and soon they drop the German dialect. In time they accept cars and electricity, and before long they wear fancy clothes and attend high school. The 1877 division serves as a timely reminder of the long-term consequences when a progressive group becomes enchanted by such worldly things as meetinghouses.18

Worshiping in homes is a prudent way of limiting the size of Amish congregations. The physical size of houses controls the numerical size of church districts. This practice serves two important roles: it keeps the organizational structure of the settlement simple, and it guarantees that each individual has a social home in a small congregation. So while the Amish sanctuary floats, the individual is securely anchored in a strong social network. People are known by first names. Birthdays are remembered, and illness is public knowledge. In contrast, Moderns often float anonymously in and out of permanent sanctuaries. The mobile Amish sanctuary affirms the centrality of the family by keeping religious functions tied to the home and integrated with family life. This is a radical departure from modern religion with its specialized services in sanctuaries cut off from the other sectors of life.

A mobile meetinghouse not only assures individuals of a secure niche in a small social unit but also enhances informal social control. Close ties in family networks place informal checks on social behavior. The mobile sanctuary assures that, on the average, members will visit the home of every family once a year. These annual visits also serve as subtle inspection tours that stymie the proliferation of worldly furnishings in Amish homes. The visits shore up social cohesion and solidarity. How many people in contemporary congregations have toured the homes of all of their fellow members in the past year?

The mobile sanctuary protests the “cathedrals” of modern Christendom, which the Amish view as ostentatious displays of pride that point, not heavenward, but earthward to the congregation’s social prestige. The financial resources used by many congregations for buildings, steeples, organs, and pastors are used by the Amish for mutual aid. Expansion, fueled by biological growth, is not dependent on evangelistic programs and state-of-the-art facilities that compete with other churches. The Amish are baffled as to why Moderns build opulent homes but do not worship in them and then construct expensive sanctuaries for once-a-week gatherings. Although Amish homes are not luxurious, they are heavily used for worship, work, eating, and socializing.

The decision to reject the meetinghouse has profound theological and sociological implications. Moving to a meetinghouse separates church and home, religion and life. It cuts a congregation’s ties to a specific geographic area and breaks up the intimate bonds of face-to-face relations. The use of a meetinghouse encourages the growth of large congregations where individuals easily become lost in the crowd. Finally, a meetinghouse becomes an abstract symbol, so that church becomes a place, rather than the living embodiment of a people; a location for worship, rather than the incarnation of religious practice.19 The mobile sanctuary, while not a public symbol, is deeply etched in Amish consciousness. Small, local, informal, lowly, and unpretentious, it is the structural embodiment of Gelassenheit—a major clue to the growth and well-being of Amish society.

One of the striking aspects of Amish society is the absence of bureaucracy. The organizational structure is loose and fuzzy. Kitchens, shops, and barns provide office space for informal committees. There are no headquarters, professionals, executive directors, or organizational charts. Apart from schoolteachers, there are no paid church employees, let alone professional ones. The nebulous structure confounds outsiders. Public officials are not always sure who to contact to ascertain Amish opinions and policies. The vitality of Amish culture is remarkable, despite the lack of consultants, corporate offices, strategic plans, and elaborate flow charts. Amish society is linked together by a web of interpersonal ties that stretches across the community. How is unity possible with dozens of loosely coupled congregations?

The solution to this riddle lies in the fairly flat leadership structure. Each bishop typically serves two districts. The eighty adults in each district are only one step away from the top of the church hierarchy. The flat, two-tier structure links grassroots members directly to the citadel of power and has several benefits. Each bishop personally knows the members of his districts and in this way monitors the pulse of the community. Members feel a close tie to the central decision-making structure because their bishop attends the fall and spring Bishops’ Meetings and can provide feedback on the discussion. The bishop, in turn, understands the larger concerns of his fellow bishops across the settlement. Thus he can personally explain churchwide regulations to his members. With about 160 adult members in his two districts, he knows his people well and is able to monitor social change on a first-name basis.

A seniority system based on age and tenure undergirds the power structure of the bishops. A young minister described the decision-making process among the bishops: “The oldest ones have priority. It tends to point to the oldest one. If they want a final decision, they say to him, ‘Let’s hear your decision.’” If health permits, the senior bishop presides over the Bishops’ Meeting, as well as various Ministers’ Meetings a few weeks later. The diplomatic skills of this highly esteemed elder statesman are crucial for upholding harmony. A minister described the seniority system: “Many bishops go to the oldest bishop to ask for his advice on a certain issue. And he will not hesitate to give his opinion, based on Scripture. Then he will conclude and say, ‘Don’t do it that way just because I told you, go home and work with your church.’ So it is not a dictatorship by any means; it works on a priority basis and a submitting basis” (emphasis added).

Twice each year, some seventy-five bishops across the settlement confer on problems and discuss changes that might imperil the welfare of the church. Four regional Ministers’ Meetings, involving bishops, ministers, and deacons, follow on the heels of the Bishops’ Meeting each fall and spring. These regional meetings of ordained leaders, numbering over one hundred men, meet in a home, barn, or cabinet shop. The bishops report on issues from their Bishops’ Meeting and solicit the ministers’ support. Other concerns or special problems are also handled. The leaders’ meetings play a significant role in maintaining cohesion and harmony across the settlement.

Historically, the hub of the settlement was around the village of Intercourse, but with the southward expansion the geographical and ideological center has shifted toward Georgetown. The number of districts grew from 11 in 1920 to 131 by 2000, stretching the organizational patterns. The leadership structure was revised in three ways to fit the prolific growth. First, the span of each bishop’s control remained the same. In pyramid fashion, growing organizations often add rungs in their hierarchy as well as widen the control of top managers. The Amish have resisted this pattern. Instead of adding more congregations to each bishopric, they increased the number of bishops as districts multiplied. Keeping two districts per bishop and allowing all bishops to participate in the Bishops’ Meeting prevented the development of new levels of authority. The flat architecture enhances social control as well as the church’s ability to monitor social change.

Multiplying the number of bishops, however, led to other problems. With eighteen districts in the 1940s, nine bishops could easily meet and conduct their business informally. As the number of bishops increased, leadership became consolidated in an informal “executive committee” of senior bishops. The wisdom of this small group carries compelling authority in the Bishops’ Meeting. Membership in this senior caucus of bishops is based on age and tenure rather than on election or appointment. Members of this inner circle do not directly supervise other bishops, for even these senior members have their own districts. Without the benefit of professional consultants or middle managers, all the bishops serve, in their words, as “watchmen on the walls of Zion,” looking out for the church’s welfare.

FIGURE 4.2 Distribution of Church Districts in the Lancaster Settlement and Boundaries of Four Regional Ministers’ Meetings

The growing number of districts precipitated a third change in organizational structure. By 1975 the community had expanded to fifty-two districts. It was difficult to find a meeting place to accommodate the large group of ordained leaders, which by then consisted of some two hundred bishops, ministers, and deacons. Conducting business was hampered without a loudspeaker system and formal parliamentary procedures. Thus, in April 1975, the leaders were divided into north and south subgroups along Route 340, an east and west road through the heart of the settlement.20 Facing relentless expansion, the settlement was divided again in 1993 into four quadrants, as shown in Figure 4.2. Bishops from the entire settlement continue to meet twice a year, followed by meetings of the ordained leaders in each respective quadrant. Many members credit the leaders’ meeting as a key factor that enabled the settlement to avoid schism and maintain a semblance of unity despite enormous change in recent years.

No formal committees report to the Amish bishops. Over the years, as lay members have formed committees for special projects, they have often consulted with ordained leaders as a gesture of goodwill. In general, the ministers and bishops, guardians of tradition, are reluctant to initiate or endorse new ventures or serve on committees. The formal power structure, slanted toward tradition, reacts to social changes but rarely exercises a leadership role in establishing new programs. Although the bishops’ body has steered clear of formalized procedures, several networks have emerged to address special needs. In each case, interested laymen, sometimes with, and other times without, the blessing of the bishops, have coordinated activities that require resources beyond the scope of local districts. These networks illustrate how social capital is mobilized to address special needs across the settlement.

1. Amish Aid Society. Community barn raisings have been a longtime public symbol of mutual aid among the Amish. An informal plan pays for replacement materials and property destroyed by a fire or storm. Begun in 1875, the Amish Aid Society seeks to spread the costs of disaster across the community. Property owners who join the plan are assessed a fluctuating amount per $1,000 of property valuation. It is “assessment by need after the fire,” said one member. A committee monitors the plan, and each church district has a director who records property assessments and collects the “fire tax.” When the central treasury becomes depleted, the committee asks the director in each district to collect a new assessment. Collections vary by the frequency of fires but average about one a year. This modest system of fire and storm insurance operates without paid personnel, underwriters, agents, offices, computers, lawsuits, or profits. Its sole purpose is to provide a network of support for members. Manual labor for cleanup and rebuilding is freely given by members whenever disaster strikes.21

2. Old Order Book Society. In 1937, in response to the consolidation of public schools, a group of laymen organized a School Committee, which sought to have Amish children excused from public school after the eighth grade. Eventually Amish schools were built and administered by local Amish school boards. The School Committee evolved into a statewide organization known as the Old Order Book Society, which coordinates Amish schools today. The society maintains a liaison with state education officials and provides guidelines for the administration of one-room Amish schools. Representatives from different settlements in Pennsylvania attend the society’s annual meeting.22

3. Amish Liability Aid. In the 1960s, Amish businessmen began purchasing commercial liability insurance to protect themselves from lawsuits. The church had a longstanding opposition to worldly insurance programs, which use the force of law and undermine mutual aid. To resolve the dilemma of providing protection against lawsuits without using commercial insurance, Amish Liability Aid was established in 1965. Within a decade, the plan had nearly a thousand members.23 According to one member, this plan “protects you from others when there’s an accident and you’re not protected yourself.” Participation is voluntary, and members of the plan make a small annual contribution that fluctuates with the level of need across the settlement.

4. National Steering Committee. In the early 1960s, some Amish youth served as conscientious objectors in hospitals as an alternative to military service. These young men frequently became worldly, sometimes married non-Amish nurses, and often did not return home. And when they did, they found it difficult to fit into their rural communities. In an effort to solve this problem, Amish leaders across the nation met in Indiana in 1966. This meeting gave birth to a National Steering Committee, which became a broker of sorts between the Amish community and government officials.

Initially focused on alternative service, more recently the committee has mediated legal disputes between the government and the Amish on Social Security, hard hats, unemployment insurance, Worker’s Compensation, 401(k) savings plans, and many other matters. In the role of a meek lobbyist, the committee chairman stays abreast of legislation that might impinge on Amish life. He also provides feedback to legislators who want Amish reactions to pending legislation. The National Steering Committee has three members, directors in various states, and a network of local representatives. An annual national meeting reviews the work of the committee, whose chairman lives in the Lancaster settlement.24

TABLE 4.3

Social Networks and Committees by Date of Origin and Functiona

The committee functions as a self-perpetuating body outside the formal structure of the church. Individual bishops support the committee and often attend some of the meetings. In terms of size, structure, procedures, and written guidelines, the committee reflects the greatest imprint of bureaucracy of any organization to date. Despite this bureaucratic stamp, the committee operates from a home office with volunteer labor.

5. Church Aid. Caught between the rising costs of hospitalization and their reluctance to accept Medicare, some Amish families began buying medical insurance in the late 1960s. Fearing that commercial insurance would undercut the community’s reliance on spontaneous mutual aid, the Amish have always frowned on commercial policies. Rising hospital costs threatened to bring a fuller embrace of commercial insurance and to undercut traditional mutual aid. Thus, a group of Amishmen initiated Amish Church Aid—an informal community-based version of hospital insurance. The program began in January 1969, and within four years 1,450 members from thirty-six districts were involved in the program.25 Amish families may join Church Aid only if the ordained leaders in their district support the plan. About 75 percent of the districts participate. Some districts do not subscribe because of its similarity to commercial insurance. Nonparticipants with large medical bills are usually assisted by alms funds from their own district as well as from adjoining ones. Members who participate in Church Aid make a monthly contribution and receive help with medical bills that exceed a deductible of several thousand dollars. Church Aid guidelines make it clear that members involved in motor vehicle accidents in which they are the driver will not be reimbursed for medical expenses.26 The plan will also not assist with organ transplants or expenses at cancer clinics in Mexico.

6. Disaster Aid. The Lancaster Amish have been longtime participants in disaster relief projects organized by Mennonite Disaster Service. In 1969 they formed an Amish Disaster Committee to coordinate responses to Hurricane Camille in Florida. This committee eventually became a subcommittee of Mennonite Disaster Service and provides volunteers to assist in cleanup and rebuilding projects following natural disasters—tornadoes, hurricanes, and floods—outside the Amish community.

7. Bruderschaft Library. Following the example of some other Amish communities, the Lancaster Amish organized a historical library in May 1979. The project blossomed, and in August 1984 the Pequea Bruderschaft Library was incorporated northeast of the village of Intercourse. Established by a board of seven directors, the historical library exists “to assist members of the Amish Church and others in learning about past historic beliefs and practices of the Amish Church.”27 A new building was constructed in 1990, south of Gordonville. Several part-time librarians maintain the collection and aid researchers and curious tourists.28

8. Product Liability Aid. With more and more Amish operating businesses, product liability issues began to create concerns in the late 1980s. On the one hand, dealers selling Amish products in other states wanted proof of product liability insurance. The bishops, on the other hand, were not eager for businesses to rely on “worldly insurances that could prove harmful to the Old Order Amish way of life.”29 Finally, in 1992 the Product Liability Aid program was established to help members with large liability claims for one of their products. A five-member board of directors and an advisory board of ordained officials gives oversight to the plan, which solicits funds to help shop owners, contractors, bakers, farmers, and others who face liability problems related to their products.

9. Helping Hand. This informal network provides loans to Amish people who are purchasing property or setting up a business. Begun in the Midwest, the network was established in the Lancaster settlement in 1998. This network provides connections between the wealthy and the needy.

10. People’s Helpers. This mental health network that formed in 1998 was described by one participant as “a group of our people nationwide who do counseling.” Although this informal network of caregivers began in another state, Amish from the Lancaster settlement who are interested in mental illness and depression actively participate. The group provides informal support to families who have members struggling with mental illness and refers friends to professional counselors and medical personnel.

11. Safety Committee. In response to accidents on farms and in shops, a Safety Committee formed in 1998 to encourage both safety training and compliance with government safety standards. “It helped us know what to do in case of an accident or fatality,” said one member.

These eleven informal networks link resources with special needs across the community.30 For the most part, committee leaders work with ordained leaders to build ties of understanding and gain their support. No central board or administrator appoints or oversees these special interest clusters. The networks mobilize social capital resources to serve community-wide needs. Each committee arose spontaneously to meet special needs beyond the capacity of local districts. While some of these committees show traces of bureaucracy, they are mostly informal, flat, small, and obedient to tradition. Although their loose structure would create nightmares for modern bureaucrats, they have served the Amish community well.

A health-related organization that is not formally operated by the Amish merits special mention: the Clinic for Special Children. Established in 1990 by a physician, Dr. Holmes Morton, it serves Old Order Amish, Old Order Mennonites, and other families who suffer from a high incidence of genetic diseases such as glutaric aciduria and maple syrup urine disease. It provides infant testing programs as well as diagnostic and medical services for children with inherited metabolic disorders. The clinic addresses a major need and has provided excellent service to the community. The Amish have expressed their gratitude for Dr. Morton’s work by generously supporting annual benefit auctions for the clinic.31

The social architecture of Amish society is small, compact, local, informal, and homogeneous—what sociologists sometimes call a Gemeinschaft. These features dramatically diverge from the design of postindustrial societies. Amish social structure embodies Gelassenheit and bolsters the groups’ defensive strategy against worldliness. A brief overview of the distinctive features concludes our architectural tour of Amish society.

1. Small. From egos to organizational units, Gelassenheit prefers small-scale things. The Amish realize that larger things bring specialization, hierarchy, and elite subgroups that remove average people from power. Meeting in homes for worship limits the size of congregations. Ironically, this commitment to small-scale units makes individuals “big” psychologically in that they are known intimately by a small, stable group. It is impossible to get lost in the crowd in an Amish congregation. The security provided by a small congregation lessens the pressure for individuals to “make it on their own.” Small farms are preferable to large ones. Small schools provide a personalized education. Large craft and manufacturing operations are frowned upon because big operators garner attention to themselves, establish a threatening power base, and insult the egalitarian community with excessive wealth.

An Amish businessman explained:

My people look at a large business as a sign of greed. We’re not supposed to engage in large businesses, and I’m right at the borderline now and maybe too large for Amish standards. The Old Order Amish don’t like large exposed volume. You don’t drive down the road and see big Harvestore silos sitting on Amish farms, you don’t see one of those big 1,000-foot chicken houses. I can easily tell you which are the Mennonite farms. They’ll feed 200 head of cattle, have 50,000 chickens, and milk 120 cows. They’re a notch completely ahead of us.... My business is just at the point right now where it’s beyond where the Old Order Amish people think it should be. It’s just too large.

Another businessman expressed the fear of large organizations: “Our discipline thrives with a small group. Once you get into that big superstructure, it seems to gather momentum and you can’t stop it.” Describing a growing Amish organization that the bishops curbed, he said: “It became self-serving, like a pyramid. Suppose we get a rotten egg leading it sometime? He can do more damage, and wreck in one year what we built up in twenty years. That’s why the bishops curbed it.” The Amish do not read the scientific literature that analyzes the impact of size on social life, but they realize that in the long run the modern impulse for large-scale things could debilitate their community.

Volleyball is a favorite activity at family gatherings.

2. Compact. The Amish have resisted the modern tendency to specialize and separate social functions. Unlike many forms of religion in modern society, Amish faith is not partitioned off from other activities. Work, play, child rearing, education, and worship, for the most part, are neither highly specialized nor separated from one another. The same circle of people interacting in family, neighborhood, church, and work blends these functions together in a compact network of social ties. Members of these overlapping circles share common values. Social relations are multiplex, meaning an actor relates to another person in many different functions: as a relative, neighbor, co-worker, and church member. The dense webs of social interaction minimize privacy. Gossip, ridicule, and small talk become informal means of social control as networks crisscross, so that as one member observed, “Everybody knows everything about everyone else.” Indeed, in the words of another member, “The Amish grapevine is faster than the Internet.”

If modernity separates through specialization and mobility, it is not surprising to hear Amish pleas for social integration—for “togetherness,” “unity,” and a “common mind.” On one occasion, the bishops admonished teenagers to stay home more on weekends and urged parents to have morning worship with their families as “a good way of staying together.” A young woman explained why the church frowns on central heating systems: “A space heater in the kitchen keeps the family together. Heating all the rooms would lead to everyone going off to their own rooms.” Another member described the compact structure of Amish society this way: “What is more Scriptural than the closely-knit Christian community, living together, working together, worshiping together, with its own church and own schools? Here the members know each other, work with and care for each other, every day of the week.”32

3. Local. Amish life is staged in a local arena. Largely cut off from mass communication, rapid transit, geographical mobility, and the World Wide Web, Amish life revolves around the immediate neighborhood. Business-people are somewhat conversant about national affairs, but the dominant orientation is local, not cosmopolitan. Things close by are known, understood, and esteemed. Typical phrases in Amish writings—“home rule,” “home community,” “local home standards”—anchor the entire social system in the local church district. The local base of Amish interaction is poignantly described in an Amish view of education: “The one-room, one-teacher, community school near the child’s home is the best possible type of elementary school. Here the boys and girls of a local community grow up and become neighbors among each other.”33

4. Informal. With few contractual and formal relationships, Amish life is fused by informal ties anchored in family networks, common traditions, uniform symbols, and a shared mistrust of the outside world. The informality of Amish society expresses itself in many ways. Social interaction is conducted on a first-name basis without titles. Oral communication takes precedence over written. Few written records are kept of the meetings of ordained leaders. Organizational procedures are dictated by oral tradition, not policy manuals and flow charts. Although each bishop wields considerable influence, the congregations across the settlement are loosely coupled together by family networks rather than formal policies.

Burials take place in local family cemeteries marked with equal-size tombstones. The small stones in the foreground mark the graves of children.

5. Homogeneous. The conventional marks of social class—education, income, and occupation—have less impact in Amish society. Ending school at eighth grade homogenizes educational achievement; and in the past, the traditional vocation of farming leveled the occupational structure. Some Amish own several farms and display discreet traces of wealth in their choice of farm equipment and animals. In recent years, business owners and artisans have emerged as new occupational groupings. Similar occupational pursuits in bygone years minimized financial differences, but that is beginning to change with the rise of Amish businesses. Today farms are typically valued at over $500,000, and it is not uncommon for an Amish business to have annual sales exceeding $2 million. The recent changes seriously threaten the historic patterns of equality.

The financial resources of farm and shop owners often exceed that of shop workers, who toil for hourly wages. High land values and productive businesses are disturbing the egalitarian nature of Amish society. One member, describing a certain rural road, said: “Three Amish millionaires live up there, but they don’t drive around in Cadillacs, own a summer home at the bay, or have a yacht.” Although wealth in Amish society is not displayed conspicuously, the recent changes have generated a social class of entrepreneurs with considerable money. Despite growing inequality, there is at least an attempt to maintain common symbols of faith and ethnicity on the surface. A well-to-do businessman and farm laborer dress alike, drive a horse to church, and will be buried in identical Amish-made coffins.

On the whole, the structure of Amish society is relatively flat, compared to the hierarchical class structure of postindustrial societies. There are few examples of extreme wealth and virtually no poverty in Amish society. In all of these ways, Amish architecture displays an elegant simplicity—small, compact, local, informal, and homogeneous—a simplicity that embodies Gelassenheit and partially explains the riddle of Amish survival.