Shunning works a little bit like an electric fence around a pasture.

—former Amishman

Social life balances on a tripod of culture, structure, and ritual. In order to survive, societies must develop cultural blueprints—collective guidelines that translate values and beliefs into expectations for social behavior. The social architecture, the organizational structure of a society, reflects the values in its cultural blueprint. However, culture and structure are lifeless forms until they are energized by social interaction. Chapters 3 and 4 examined the cultural blueprint and the social architecture, respectively, of Amish society. This chapter explores the patterns of social interaction and the religious rituals that energize and reaffirm the moral order of Amish life.

Religious rituals fuse culture and structure into social music. Without ritual, a group’s culture and structure are static—like an orchestra frozen on stage. For example, culture exists in the minds of the musicians; the players understand the musical notations and they know how to play their instruments. Structure is present on the stage as well. Arranged carefully in their proper sections, the musicians face the conductor. But there is no ritual, no interaction, no music until the conductor’s baton signals the start of the performance—the ritualized interaction. Cultural knowledge and social architecture suddenly blend into music. In a similar fashion, the rituals of interaction combine culture and structure into a social symphony in Amish life.

Social interaction in American society is organized by rituals ranging from handshakes and greetings to graduations and funerals. Religious rites rejuvenate the moral order of a group and place its members in contact with divine power. Amish rituals are not hollow. From common meals to singing, from silent prayer to excommunication, the rites are filled with redemptive meanings. As sacred rituals, they retell holy stories, recharge group solidarity, and usher individuals into divine presence.

The rituals of Amish life have two striking features: their oral character and their predictable formulas. The orality of Amish culture stands in contrast to the written documents of modern life. Collective memory is a powerful organizer and transmitter of Amish values. Hymns do not have musical notations, and neither sermons nor church rules are written down. The tradition is embodied in the people and their stories. This gives the ethos of the community an organic character that is informal, nonrational, and flexible.1

On the other hand, the ritual sequence of events is fairly firm. From weddings to funerals, from baptisms to ordinations, the ritual pattern is fixed. Individuals cannot tinker with ritual recipes. In fact, the protocol for Amish weddings is so clear that a wedding rehearsal is not required. There is one way to be baptized, one way to be married, and one way to be buried—the Amish way. The rigidity of the ritual eliminates any individual choice and makes the ceremonial life of the community highly predictable.2

The Amish blueprint for expected behavior, called the Ordnung, regulates private, public, and ceremonial life. Ordnung does not translate easily into English. Sometimes rendered ‘ordinance’ or ‘discipline,’ the Ordnung is an ordering of the whole way of life—a code of conduct that the church maintains by tradition rather than by systematic rules.3 A member noted: “The order is not written down. The people just know it, that’s all.” Rather than a packet of rules to memorize, the Ordnung is the “understood” set of expectations for behavior. In the same way that the rules of grammar are learned by children, so the Ordnung, the grammar of order, is absorbed by Amish youth. The Ordnung evolved gradually over the decades as the church sought to strike a balance between tradition and change. Interpretation of the Ordnung varies somewhat from congregation to congregation.

A young minister describes the Ordnung as an “understanding.” He explained: “Having one understanding, getting together and discussing things and admonishing according to that understanding and punishing according to the understanding, getting principles built up on an even basis, you know, can be beneficial” (emphasis added). In some areas of life, the Ordnung is very explicit; for example, it prescribes that a woman’s hair should be parted in the center and that a man’s hair should be combed with bangs. Other facets of life, left to individual discretion within limits, include food preferences, job choice, style of house, place of residence, and hobbies. The Ordnung contains both prescriptions—you ought to wear a wide-brimmed hat—and proscriptions—you should not own a television.

Children learn the Ordnung from birth by observing adults and hearing them talk. Ordnung becomes the taken-for-granted reality—“the way things are” in the child’s mind. In the same way that non-Amish children learn that women, rather than men, wear lipstick and shave their legs, so Amish children learn the ways of the Ordnung. To the outsider, the Ordnung appears as a maze of legalistic rules. But to the child growing up in the world of the Ordnung, wearing an Amish hat or apron wherever one goes is just the normal thing to do. It is the way things are supposed to be, the way God intended them.

The Ordnung defines certain things as simply outside the Amish world. Asked whether an Amish person could be a real estate agent, a member replied: “Well, it’s just unheard of, a child wouldn’t even think of it.” All in all, the Ordnung represents the traditional interpretations—the rules, regulations, and standards—of what it means to be Amish. Although children are taught to follow the Ordnung from birth, it is not until baptism that they make a personal vow to uphold it forever.4

Core understandings of the Ordnung regarding education, divorce, cars, and so forth are fairly stable and need little verbal reinforcement. One woman said, “We’re not supposed to wear makeup, but it’s something the bishops don’t need to mention. I don’t even think they know about makeup. They wouldn’t really know how to talk about it.” The outer edges of Ordnung evolve, however, as the church faces new issues. Some technological innovations, such as calculators, are permitted by default; but others, such as embryo transplants in dairy cows, are strictly forbidden. Other issues, such as installing phones in Amish shops, may fester for many years. When a new practice such as eating in restaurants or using the Internet becomes “an issue,” it is discussed by the ordained leaders, and if a consensus develops, it becomes grafted into the Ordnung.

Two Amish teens rollerblade in front of their home. The Ordnung regulates dress, technology, and the decor of homes.

The Amish are reluctant to change their mind after a practice becomes ingrained into the Ordnung. Rather than overturn old practices, they often develop ingenious ways to bypass them. For example, freezers are not permitted in Amish homes because they would bring other electrical appliances, but members are permitted to own one in the home of a non-Amish neighbor. Because changing the Ordnung is difficult, the Amish are slow to outlaw things at first sight. If seen as harmless, a new practice—for example, the use of barbecue grills or trampolines—will drift into use with little ruckus.

Adherence to the Ordnung varies among families and church districts. Some bishops are more lenient than others in their enforcement of it. If a member conforms to the symbolic markers of the Ordnung, there is considerable “breathing space” in which to maneuver and still appear Amish. The Ordnung is enforced with leniency under special circumstances. A retarded child may be permitted to have a bicycle, which is usually off-limits, or a family may be permitted to use electricity in their home to operate medical equipment for an invalid. Although self-propelled riding equipment such as a riding lawn mower is forbidden, electric wheel chairs are widely used by the disabled.

Examples of Practices Prescribed by the Ordnung:

color and style of clothing

hat styles for men

order of the worship service

kneeling for prayer in worship

marriage within the church

use of horses for fieldwork

use of Pennsylvania German

steel wheels on machinery

Examples of Practices Prohibited by the Ordnung:

air transportation

central heating in homes

divorce

electricity from public power lines

entering military service

filing a lawsuit

jewelry, including wedding rings and wrist watches

joining worldly (public) organizations

owning computers, televisions, radios

owning and operating an automobile

pipeline milking equipment

using tractors for fieldwork

wall-to-wall carpeting

A maze of rules to the outsider, the Ordnung feels like stuffy legalism even to some Amish, but for most of them it is a sacred order that unites the church and separates it from worldly society. In the words of one minister, “A respected Ordnung generates peace, love, contentment, equality, and unity.... It creates a desire for togetherness and fellowship. It binds marriages, it strengthens family ties, to live together, to work together, to worship together, and to commune secluded from the world.”5

All things considered, there are several levels of piety in the moral order of Amish society:

1. Acceptable behavior—so widely practiced that it’s never discussed;

2. Esteemed behavior—expected of ordained leaders and their spouses, but not of laymembers;

3. Frowned upon behavior—discouraged by the church but not a test of membership;

4. Forbidden behavior—proscribed by the Ordnung and a test of membership.

A fifth category involves behavior that is so immoral—for example, murder—and is so clearly wrong that it is not even included in the Ordnung. Indeed, in a sixth category are ambiguous practices that are acceptable in some districts but not in others. These levels of piety vary somewhat across the settlement from plainer to higher districts. The exact guidelines change over the years as the normative order flexes with new issues and new leaders.

Following the Ordnung—wearing proper clothing, plowing with horses, shunning publicity, avoiding worldly pleasures, and singing the hymns of the Ausbund—is a sacred ritual that symbolizes faithful obedience to the vows of baptism, the order of the community, and the will of God. Abandoning self and bending to the collective wisdom provide divine blessing and the promise of eternal life.

Small children accept and practice the Ordnung as they receive it from their parents. Before they are baptized, Amish youth are under the care of their parents, and the church has no official jurisdiction over them. Some Amish teenagers conform to the Ordnung and others do not. Some rebel or “sow wild oats” during rumspringa—the “running around” years that begin at age sixteen. During this ambiguous stage, when they are neither in nor out of the church, teenagers face the most important decision of their lives: Will I join the church? It is not a trivial matter. Those who kneel for baptism must submit to the Ordnung for the rest of their lives. If their obedience to the church falters, they will be ostracized forever. Young adults who decline baptism eventually drift away from the community. However, they will not be shunned, because they have not made a baptismal pledge. As good Anabaptists, the church takes the importance and integrity of adult baptism very seriously.

Romantic ties may add an incentive for church membership, for Amish ministers only marry church members. “We have no weddings for someone who is not a member of the church. It’s as simple as that,” said one young husband. For many young people, the rite of baptism is the natural climax of a process of socialization that funnels them toward the church. For others, it is a difficult choice. Some leave home and flirt with the world, while others flirt with it behind their parents’ backs. But in the end, nine out of ten youths promise to embrace their birthright community for life. A young married husband described the tug of romance, land, family, and community that pulls young people toward baptism:

Most of the young sowing wild oats are just out there to put on a show. It’s just something that kind of comes and goes. If they have well-established roots, most of them kind of have their mind set on a particular girl. There is something that really draws them back.... Like I say, the close family ties are the thing that really draws you back. I still think it [Amish life] is a better lifestyle, I really think so. If you grow up with it, there really is something here that just kind of draws. If you do a lot of this running around and going on, it kind of makes you feel foolish after awhile.

The typical age of baptism ranges from sixteen to the early twenties. Sixty percent join the church before they are twenty-one. Girls often join at a younger age than boys. Instruction classes during the five months preceding the ceremony place the stark implications of baptism before the candidates. During the first half hour of church services over the summer months, the novices meet with the ministers for instruction. The ministers and bishop review the eighteen articles of the Dordrecht Confession of Faith and emphasize selected aspects of the Ordnung.6 On the Saturday before the baptism, there is a special wrap-up session when candidates are given their last chance to turn back. Hostetler notes that “great emphasis is placed upon the difficulty of walking in the straight and narrow way. The applicants are told that it is better not to make a vow than to make a vow and later break it.”7 Young men are reminded that they are consenting to serve as leaders if ever called by the church.

The baptismal rite follows two sermons during a regular Sunday morning service.8 After the final instruction class, the ministers will say, “Go take your seats with bowed heads.” The candidates sit in a bent posture, with a hand over the face, signaling their willingness to submit—to give themselves under the authority of the church. The deacon provides a small pail of water and a cup. The bishop tells the candidates to go on their knees “before the Most High and Almighty God and His church if you still think this is the right thing to do to obtain your salvation.” The candidates are then asked three questions:

The young owner of this carriage will need to get rid of his stereo speakers and other frills before he is baptized.

1. Can you renounce the devil, the world, and your own flesh and blood?

2. Can you commit yourself to Christ and His church, and to abide by it and therein to live and to die?

3. And in all the order (Ordnung) of the church, according to the word of the Lord, to be obedient and submissive to it and to help therein? (emphasis added)9

The congregation stands for prayer while the applicants remain kneeling. Then the bishop lays his hands on the head of the first applicant. The deacon pours water into the bishop’s cupped hands and it drips over the candidate’s head. The bishop then extends his hand to each member as he or she rises and says, “May the Lord God, complete the good work which he has begun in you and strengthen and comfort you to a blessed end through Jesus Christ. Amen.” The bishop’s wife greets the young women with a “holy kiss,” and the bishop likewise greets the men and wishes them peace. In a concluding word, the bishop admonishes the congregation to be obedient and invites other ministers to give a testimony of affirmation. The ritual of baptism places the new members into full fellowship, with all the rights and responsibilities of adult membership.10

The worship service dramatically reenacts the Amish moral order. Social structure and beliefs coalesce in a sacred ritual that embodies the core meanings of Amish culture. The worship service imprints the “understandings” of the Ordnung in the collective consciousness. This redemptive ritual reminds members who they are as it ushers them into divine presence. With few props and scripts, the drama of worship reaffirms the symbolic universe of Amish culture.

Each district holds services every other Sunday in the home of a member.11 Services begin early, with some members arriving by 8:00 a.m. Members either drive by horse and buggy or walk to the service. The prelude for the day is played out on the keyboard of country roads as the rhythmic clip-clop of hoofbeats converge on the meeting site. The three-hour service culminates in a light noon meal, followed by informal visiting throughout the afternoon. The local congregation swells in size as some friends and family from other districts join the service. Unlike some contemporary congregations where attendance is sporadic, everyone shows up and packs into several rooms of a member’s home, a basement, or a shop. It is not unusual for two hundred adults and children to squeeze into a house. Partitions between rooms are opened. Backless benches and folding chairs face the preacher in a central area. Benches, songbooks, and eating utensils are transported from home to home in a special wagon.

The service is organized around unison singing and two sermons. The main sermon lasts about an hour. Illustrations are taken from the Bible, nature, and local events. Preachers follow a published lectionary of New Testament scriptures for the year, which appears in Appendix E. Sermons often include references to accounts of suffering in the Martyrs Mirror. Preachers remind members that they are pilgrims and strangers traveling in a different direction than the outside world. Obedience and humility are key themes in the service. Ministers urge members to obey the commandments of the Scripture, the vows of baptism, and those in authority over them. After reading the Scripture, the deacon may also admonish members to be obedient to the Lord. The following is the traditional order of the Sunday morning service:

fellowship upon arrival

silence in worship areas

congregational singing (40 minutes)

ministers meet in a separate room

opening sermon (25–30 minutes)

silent kneeling prayer

scripture reading by deacon (members standing)

main sermon (50–70 minutes)

affirmations from other ministers and elders

kneeling prayer is read from a prayer book

benediction (members standing)

closing hymn

Members’ Meeting, as necessary

fellowship meal

visiting and fellowship12

The Amish have no altar, organ, offering, church school, ushers, professional pastors, printed liturgy, pulpit, cross, candles, steeples, robes, flowers, choirs, or handbells. Contemporary props of worship are completely absent. Plain people gather in a plain house and worship in simplicity. A traditional, unwritten “liturgy” regulates each moment of the service. The ceremony symbolizes the core values of Amish society.

Following the last hymn, a brief Members’ Meeting may be held to discuss mutual aid, to discipline a member, or to announce plans for district activities. A light lunch with a traditional menu follows the service.13 The modest meal has the character of a fellowship gathering rather than a large feast. In the afternoon visiting cliques emerge around age and gender, but for the most part, the day is a common experience. From beginning to end, the worship symbolizes waiting, unity, and humility; it is a ritualistic reenactment of Gelassenheit.

Gender, age, and leadership roles shape the worship in several ways. Men and women enter the house by separate doors and sit in separate areas. Women do not lead any aspect of the worship, but after the service they prepare and serve the meal. They eat at separate tables from the men and are responsible for cleaning up. Age characteristics are pronounced in the ordering of social behavior. The eldest members enter the house and worship areas first, followed by others in roughly descending age. Seating in the worship areas is dictated by age and gender, with spaces designated for older and younger members.

One enters the worship area as a man or woman, not as a family member or an individual. One is accountable to the church, expected to behave and dress according to the patterns for a particular role—young woman, older man, and minister. By dividing families in the seating area, the church symbolizes its authority not only over the individual but over the family as well.

Leadership status is also visible. The ministers take their seats in the “ministers’ row.” The adult men shake hands with the ministers outside as they assemble or as they find seats in the house. Women may shake hands with the ministers in the kitchen or as they enter the worship area. The handshake, often without words, is an act of deference to the ministers’ authority and a reaffirmation of good standing in the fellowship.

As the young unmarried men enter the house, the older men, who are already seated, take off their hats. The young men walk by the ministers’ row and shake their hands in an act of deference as well. As the first song begins, the ministers take off their hats in one sweeping action. On the first word of the third line of the first song, the ordained leaders take their hats and walk to another room in the house to counsel together and select the preacher of the morning. After meeting for thirty minutes, they return during the last verse of the second hymn, hanging their hats on the wall which signals that the worship is about to begin. Ordained men are the only ones who stand or speak in the service. Afterward, they sit at the table that is served first.

The cultural values embedded in the ritual structure stun modern consciousness. The entire service creates a radically different world—a world of waiting. There are no traces of rushing. The day of worship stretches from 8:00 a.m. to about 3:00 p.m. The extremely slow tempo of singing ushers in a different temporal order. One song may stretch over twenty minutes. In a rising and falling chant, each word expands into a miniature verse in itself. The congregation sings from the Ausbund—a hymnal with only printed words.14 Many of the Ausbund hymns were written by persecuted Anabaptists in the sixteenth century. The ancient tunes, learned by memory, are sung in chant-like unison without any rhythm. The slow and methodic chant-like cadence reflects a sixteenth-century medieval world in image and mood.

A song leader sits among the congregation. In a spirit of humility, he is selected on the spot. A member described the selection process: “You’ll see men whispering, ‘You do it, you do it,’ until someone finally goes ahead and does it.” The leader sings the first syllable of each line and then the congregation joins in the second one.

The lengthy service is conducted without coffee breaks, worship aids, or special music. Very young children sleep, wander among the aisles, or occasionally munch crackers. Four- and five-year-olds sit patiently on backless benches and on the laps of their parents. The service trains children in the quiet discipline of waiting. It is a lesson in Gelassenheit—waiting and yielding to time, parents, community, and God.

The grammar of the worship incorporates humility and submission. It would be considered pretentious for a minister to prepare a written sermon or even bring a polished outline. Ministers do not know who will preach the morning sermon until they meet while the congregation sings the first hymn. If a visiting minister is present, he will likely be asked to preach. The preacher is chosen by a consensus of the ordained leaders while the congregation is singing. The spontaneous selection preempts any pretensions of pride. As he begins his sermon a few minutes later, the preacher reminds the congregation that he is a servant of God ministering to them in his “weakness.”

The rite of humility is described by one member: “The one who has the main sermon will often begin by saying, ‘I’m not qualified to preach, but I preach because God called me to preach. I wish that someone else, a visiting minister, or someone who would be more capable of delivering the sermon, would preach but because that’s not the case, I will give myself up to be used by God to preach the sermon today’” (emphasis added). The member continued: “I never cease to be amazed how they can get up and preach for a whole hour without referring to notes or their closed Bible.” In a ritual enactment of humility that downplays individualism, preachers and audience rarely look directly at one another. By yielding in humility to others and giving himself up in front of the congregation, the preacher reenacts the essence of Gelassenheit.

The congregation kneels twice in prayer. The first prayer, a silent one, follows the opening sermon and lasts several minutes. The entire congregation waits on God quietly, in humility, on their knees on a hard floor. The Amish believe that it would be preposterous for someone to offer a spontaneous prayer. It is better to wait together in silence. The congregation kneels a second time near the end of the service as the deacon reads a traditional prayer.

Symbols of collective integration unite the ritual. Singing in unison prevents the showy display that accompanies solos, choirs, and musical performances. A praise song, the “Lob Lied,” is the second hymn in every service just before the sermon.15 Thus, on a given Sunday morning, all the congregations holding services across the settlement are singing the same song at roughly the same time, an experience one member described as giving a beautiful feeling of unity among the churches. From the elderly bishop to the youngest child, kneeling together in prayer and singing in unison create a shared sense of humility. Children are not shuttled off to church school, and adults are not given a chance to select a stimulating adult class. The common worship does not cater to special-interest or age groups. The specialization of modern life is simply not present. There is little individual expression in the service. One does not choose a special pew. Seating patterns are determined by age and sex, and one simply follows in line and fills in each bench. Ministers and a few elders give brief affirmations to the main sermon—in essence, endorsements of it. For the most part, the service is a common experience for old and young alike.

Simplicity pervades the service, from backless benches to bare walls and black vests. The uniform dress code prevents ostentatious display. Members dress in full conformity with the Ordnung. Some young men may sport styled hair to show off their last months of independence before joining the church, but they also kneel in humility. Members dress appropriately for their age and sex because this is the sacred moment of the religious week when even the careless are careful to follow the Ordnung. The outward uniformity signals spiritual unity as the community gathers in the presence of God.

Fitting some two hundred people into several large rooms or the basement of a house forces a physical closeness. Chairs and benches are packed tightly together. A young minister replayed the surprised reaction of visitors to the kneeling: “They said, ‘Everyone squats, bangs, crashes, and suddenly goes down, and where’s the kneeling pads?’ We don’t have them, you know, and it’s nothing to us because it’s our tradition.” Though viewed as confining by Moderns, the physical closeness symbolizes the unity of the tight-knit community, close to one another and close to God, in worship. For some, of course, the worship becomes an empty Sunday protocol. But for most, it is a redemptive heartbeat that reaffirms the community’s moral order twenty-six times a year.

The continuity of Amish worship over the decades is striking. A description of an Amish service written more than a century ago is virtually identical to the format today.16 Members born at the turn of the twentieth century report few changes across the decades. “It might be a little shorter and the singing might be a little faster! The sermons are very similar. There has been very little change in the Scripture that is quoted. Each minister is different, but, as a whole, it’s the same meaning expressed in different words.” Indeed, the speed of the singing signals the extent of assimilation into the larger culture. High districts sing faster.17 As the geographical size of some districts shrank in the 1990s, their services began earlier because people had less distance to travel. Compared to other spheres of Amish life, the patterns of worship have remained largely unchanged.

Hymn books and benches arranged in an Amish basement await a worship service.

Sunday is a holy day and many things are sacralized. Work, unless required for the care of animals, is forbidden as is the use of money or any purchase. Carriages are used to attend church services; cars may be hired only if there is an emergency. Coats with hooks and eyes and dresses fastened with pins are worn to Sunday service. Even smoking is discouraged among the few men who do. One minister said, “Those who smoke should leave their tobacco at home. Who would think of carrying a loaf of bread to church and eating a slice of it in front of others?”

Communion and the ordination of leaders are ritual high points that underscore the lowly values of Gelassenheit. The fall and spring communion services are rites of intensification. They revitalize personal commitment and fortify group cohesion within each district and throughout the settlement. A traditional sequence of events prepares the way for each fall and spring communion service: the Bishops’ Meeting, a congregational Counsel Meeting, the Ministers’ Meeting, and finally holy communion.

An all-day meeting of the bishops in September and March addresses controversial issues stirring in the community. Contentious issues, such as using voice mail, playing baseball in local leagues, playing golf, using computers, using harvesters, and troublesome youth, are discussed. If a consensus among the bishops emerges, it becomes embedded into the “understanding” of the Ordnung.

Following the Bishops’ Meeting, a “preparatory,” or Counsel Meeting is held in local districts in conjunction with the regular worship service. This service of self-examination is held two weeks before communion. The sermon of the morning creates an emotional buildup to the counsel service, when members are asked to affirm the Ordnung, indicate peace with God, and express a desire to partake of communion. Sometimes the counsel service is a tense time when sin and worldliness are purged from the community. A member said: “Twice yearly, you know, they have their Bishops’ Meeting, and then they come back to the church and announce what’s up, you might say. Then the church, everybody, is given a voice to say ‘yes or no.’ And you can say, ‘No, I’m not agreed,’ but you’d better have good documentation, and that’s the way it should be.”

The counsel sermon is often two and a halfhours long, signaling the meeting’s importance. Children and nonmembers usually are not present. The sermon traces the Old Testament story from Genesis to the conquest of the Promised Land. The pivotal moment is the defeat of Joshua’s army by the people of Ai. Amish ministers stress that hidden plunder had to be confessed and given up before Joshua’s army could proceed to victory. The sermon then turns to the New Testament and shows how the golden thread of the Bible leads to Christ. Ministers plead with the congregation to destroy the “old leaven” so the body can be healthy and grow. They stress that hidden sins of pride and disobedience, if not confessed, will, like the hidden sins of Israel at Ai, lead to the church’s defeat.

Much of the counsel sermon and admonitions emphasize positive examples of how to live. The bishop also presents the church’s position on issues that are “making trouble at the time,” or things that “the bishops are not allowing yet.”18 The dress code is reaffirmed, and questionable social practices—cell phones, credit cards, the Internet—are discouraged. “We are asked to work against these troubles,” a young minister explained, “and clean ourselves of them, and then we expect a testimony from each member to see if he is in agreement with that counseling.” A member explained the procedure: “Two of the ministers go around, one with the men and one with the women, and they go around and ask each one, ‘Are you agreed?’ and everyone says, ‘I’m agreed.’ And you’d better be, too! Or have some grounds for it, which is right. This is done in front of the entire congregation.” If they disagree, members are asked to come to a front bench and explain their position.

If a serious impasse cannot be resolved, communion may be postponed until the congregation is “at peace”—meaning that all members concur with the Ordnung. The Counsel Meeting is a critical moment for purging sins of selfishness, pride, self-will—any moral decay that might erode the common life. The Counsel Meeting is a special moment when the moral order, the Ordnung, is reaffirmed and the collective will prevails. It is especially moving if a repentant offender rejoins the fellowship. If harmony emerges in the Counsel Meeting, communion follows in two weeks. The results of the local Counsel Meetings are reported at the respective Ministers’ Meetings in the settlement. A day of fasting normally occurs between the Counsel Meeting and communion.

Although somber in mood, the communion service is a celebration of unity within the body. The observance of communion begins about 8:00 a.m. and continues until 4:00 p.m. without a formal break. During the lunch hour, people quietly leave the main worship area in small clusters to eat in an adjoining room. The service peaks as the minister retells the suffering of Christ and the congregation shares the bread and wine. Some ministers pace their sermons so that the passion story occurs about 3:00 P.M., to coincide with the supposed moment of Christ’s death.

The bishop breaks bread to each member. The congregation drinks grape wine from a single cup that is passed around to commemorate the suffering and death of Jesus Christ. The sacrifice and bitter suffering of Christ are emphasized and held up as models for members. When speaking of the wine and bread, the bishop stresses the importance of individual members being crushed like a grain of wheat and pressed like a small berry to make a single drink. A bishop explained: “If one grain remains unbroken and whole, it can have no part in the whole . . . if one single berry remains whole, it has no share in the whole . . . and no fellowship with the rest.”19 These metaphors legitimize the importance of individuals yielding their wills for the welfare of the larger body.

The service culminates in footwashing, as the congregation sings. Segregated by sex and arranged in pairs, members dip, wash, and dry each other’s feet. Several tubs of warm water and towels are placed throughout the rooms. Symbolizing extreme humility, the washer stoops rather than kneels to wash the foot of a brother or sister. One bishop reminds his members that they are “stooping to the needs of their brother.” The ritual of humility concludes with a “holy kiss” and an exchange of blessing between the two partners. At the end of the footwashing, alms are handed to the deacon for the poor fund, the only offering ever taken in an Amish service. Having affirmed the moral order, the purified community is rejuvenated for another six months of life together.

The ordination of leaders is the emotional high point in the ritual life of the community. The customary practice of leadership selection mirrors Amish values and stands in sharp contrast to the selection of professional pastors.20 Only married men who are members of the local church district are eligible for ministerial office. The personal lifestyle of candidates is valued far above training or competence. There is no pay, training, or career path associated with the role of minister. It is considered haughty and arrogant to aspire for the office. Ministers are called by the congregation in a biblical procedure known as “the casting of lots,” in which they yield to the mysteries of divine selection. The term of office is for life. If a vacancy arises because of illness, death, or the formation of a new church district, a unanimous congregational vote is required to proceed.

The ordination service is typically held at the end of a communion service, often on a weekday. Male and female members proceed to a room in the house and whisper the name of a candidate to the deacon, who passes it on to the bishop. Men who receive three or more votes are placed in the lot. Typically, about a half dozen men receive enough votes. At the last instruction class before baptism, young men pledge to serve as leaders if called upon by the church. Thus, personal reasons for being excused from the lot are unacceptable. Those in the lot are asked if they are “in harmony with the ordinances of the church and the articles of faith.” If they answer yes, they kneel for prayer, asking God to show which one he has chosen.21

Members of a church district gather at a home for a worship service.

The lot “falls” on the new minister without warning. A slip of paper bearing a Bible verse is placed in a song book. The book is randomly mixed with other song books, equaling the number of candidates. Seated around a table, each candidate selects a book. The bishop in charge says: “Lord of all generations, show us which one you have chosen among these brethren.” The presiding bishop then opens each book, one by one, looking for the fateful paper that says the lot “falls on the man as the Lord decrees.”22 The service is packed with tears and emotion. Like a bolt of lightning, the lot strikes the new minister’s family with the stunning realization that he is about to assume a high and heavy calling for the rest of his life.

In the spirit of Gelassenheit, the “winner” receives neither applause nor congratulations. Rather, tears, silence, sympathy, and quiet words of support are extended to the new leader and his family, who must now bear the heavy burden of servanthood for the rest of their lives as they give themselves up to the church. This is the holiest of moments in Amish life because in a mere second, Almighty God reaches down from the highest heavens and selects a shepherd for the flock.

The simple ritual, based on biblical precedent, is an astute mechanism for leadership selection.23 Once again, personal desires are surrendered to the common welfare. The leader and his family yield to the community by “giving themselves up” for the larger cause. No perks, prestige, financial gain, career goals, or personal objectives drive the selection or accrue to the officeholder. In fact, just the opposite. Members of the congregation quietly speculate what the newly ordained couple will have to give up as they more fully “give themselves under” the authority of the church. In addition to wearing plainer clothing, they may have to put away some borderline items—fancy curtains or machinery—to better comply with the Ordnung and exemplify faithful behavior for the rest of the flock.

Core values of Amish culture are reaffirmed in the ritual, for only local, untrained men are acceptable candidates. The congregation can nominate the brightest and best who have lived among them for many years. Although it would be haughty to seek ordination, some individuals may privately hope for the office or at least enjoy the rewards of respect if ordained. The permanency of the choice underscores the durability of commitment and community. The entire ritual is a cogent reminder that leadership rests on the bedrock of Gelassenheit.

Unlike many Protestant denominations, the Amish rarely have a leadership crisis. Although to the outsider the simple ritual may resemble a divine lottery, it has profound social consequences. The abrupt “falling of the lot” prevents “campaigning” beforehand. All members may nominate candidates, but in the final analysis the leader is “chosen by the decree of the Lord.” In a critical moment that will shape its life for years, the community also yields because it must accept “the shepherd that the Lord selects.” Being selected by divine choice is quite different from being invited to serve a congregation with a sixty-to-forty vote. The minister may not be the first choice of some members, but his authority comes by divine mandate unequaled by charisma, seminary training, or theological degrees. Members who are unhappy with the choice can quarrel with God, not a faulty political process or a power play by a search committee. Furthermore, only God fires Amish ministers. It is, in short, an ingenious solution to leadership selection that in a plain and simple manner confers stability, authority, and unity to community life.

Communion is a sacred rite that revitalizes the moral order, but it is not enough to preserve the Ordnung. The Amish, like other people, forget, rebel, and, for a variety of reasons, stray into deviance. Formal social controls swing into action when informal ones fail. Rituals of confession help to punish deviance and reunite backsliders into full fellowship. Confessions diminish self-will by reminding members of the supreme value of submission. A few deviants may play the confessional role with little remorse, but most confessions are cathartic moments when the power of the corporate body unites with divine presence to purge the cancerous growth of individualism.24

In general, transgressions against the moral order are redeemed by two types of confessions: free will or requested. Free-will, or “open and willing” confessions are initiated by the offender. By contrast, requested confessions are initiated by church leaders to deal with deviant members. Depending on the circumstances and severity of the issue, the confession may take four forms: private, sitting, kneeling, and kneeling followed by a six-week ban.

In a free-will confession, a member may feel guilty for having a fault (fehla). The guilt might arise from various violations of the Ordnung—having some banned technology, inadvertently riding with someone under the ban, premarital sexual relations, cheating in a business transaction, or flying in an airplane. The person goes to the deacon or minister and confesses the fault. In some cases the deacon may offer loving counsel and close the issue in private. In other cases a public form of confession may be required. Free-will confessions involve few complications because the wayward person is cooperative and penitent.

The process becomes more strained when violators do not take the initiative. Through personal observation or reports of members, ordained leaders become aware of a transgression. A member may have used a tractor in the field, installed a silo unloader, joined a township planning commission, filed a lawsuit, attended a dance, participated in a non-Amish Bible study group, or installed a computer in their business.

Following the procedures for dealing with an offending person outlined in Matthew 18, the bishop typically asks the deacon and a minister to visit the wayward member. If the offense is a minor matter that has drawn little attention in the church, and if the member displays an attitude of contrition, the issue may be dropped at this stage. Minor issues solved in the privacy of barns and homes do not require public confession. The errant member simply acknowledges the fault and promises to stop the insulting behavior or to “put away” the offensive item. The deacon reports the outcome of the private confession to the bishop.

Serious matters that draw public attention require public confessions. The offender will be asked to make a confession at a Members’ Meeting before the entire congregation. Depending on circumstances, it may be a sitting, kneeling, or kneeling and ban confession, representing levels two, three, and four respectively. Confessions are handled in a Members’ Meeting, known as the sitting church or sitz gma, which follows a Sunday worship service. Children, nonmembers, and visitors are excused. The frequency of Members’ Meetings varies according to the press of issues in each district.

In the case of a sitting confession, the bishop explains what happened, and the member remains seated wherever he or she is and then says, “I want to confess that I have failed. I want to make peace and continue in patience with God and the church and in the future to take better care.” For a kneeling confession, the bishop invites the wayward member to come forward and kneel near the ministers in the midst of the congregation. The bishop asks the person several questions about the offense and if they are willing to stop it. The person may be sobbing with remorse. Defendants may also be given time to explain their side of the story. After answering the questions, the person leaves the area and the bishop explains a possible punishment.

If the hearing does not produce new information, the bishop presents the congregation with a punishment proposed by the ministers earlier in the morning. Members are asked if they agree with the proposed sanction. A member said: “The congregation usually agrees with the bishop’s layout, except if they know things that the ministers don’t, then they may have to recounsel the whole thing again.” A vote (der Rat) is taken by asking each member if they support the proposed punishment. Sometimes there will be disagreement or discussion at this point, but generally the congregation affirms the action proposed by the bishop. The unanimous consent of the congregation is sought before the individual returns to hear the verdict. The confessor is then invited back to the meeting and asked: “Are you willing to take on the discipline of the church?” Depending on the circumstances, the person is then reinstated or informed that a six-week ban will be enacted.

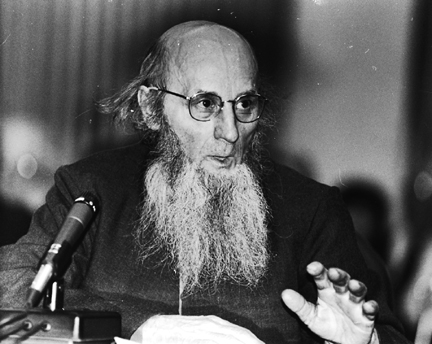

A Lancaster bishop testifies before a government committee.

The most severe form of punishment (level four) is a six-week ban.25 This, in effect, is a temporary excommunication. If penitent, the offender is eventually restored to full fellowship. Offenders come to the three church services during the six-week period and meet with the ministers for admonition during the congregational singing. The offender enters the service after everyone else has been seated and sits near the ministers in the center. As a sign of remorse, he or she sits bent over with a hand over the face during the service. The offender leaves immediately after the worship service without shaking hands or participating in the meal and fellowship. The six-week exile allows them time to reflect on the seriousness of their transgression and to taste the stigma of shunning. Other members often visit them during this time to show their love and support.

At the end of the ban, offenders are invited to make a kneeling confession in a Members’ Meeting. They are also asked two questions: Do you believe the punishment was deserved? Do you believe your sins have been forgiven through the blood of Jesus Christ? Those who confess their sin and promise to “work with the church” are reinstated into it. The bishop offers offenders the hand of fellowship, pulls them up from their knees, and gives them a kiss of peace. In the case of women, the bishop’s wife gives the kiss. The meeting concludes with some fitting words of comfort.26 Many times this is a beautiful moment of catharsis and healing in the life of the church.

For the “headstrong” who will not submit or confess to the church, the six-week probation leads to full excommunication. Errant members are invited to come to church. “If they don’t come,” explains a member, “then the church, you might say, subpoenas them; they must be there in two weeks, and if they don’t come then they lose their membership.” This places the burden of responsibility on the offender.

In each situation there is considerable freedom to improvise. Ministers try hard to “work with the church” and mediate conflicts in peaceful ways. There is, however, a firm resolve to seek solutions that will maintain harmony and save the integrity of the Ordnung as well as the authority of leaders. The entire process hinges on an attitude of submission—of Gelassenheit. Individuals who display an attitude of contrition are quickly forgiven and reinstated into the fellowship.

The obstinate who challenge the authority of leaders will feel the harsh judgment of the church. A petty, tit-for-tat syndrome, fueled by envy, sometimes sours the confessional process. In one case, a member pressed for action against a bishop’s son who was attending films and flaunting a car. In due time, the bishop sought his revenge by threatening to excommunicate the member for installing a telephone in his barn. In general, senior bishops counsel younger bishops and ministers to “work with their people,” to try to persuade them to cooperate through gentle discussion.

The ritual of confession is filled with humility and healing as well as shame. A member sketched the sequence after young church members attended a wild party hosted by Amish youth who had not joined the church:

They go before the church and they must make a confession depending on the severity of what happened, and they may even lose their membership. They hardly ever refuse to make a confession. Can you picture this, after the church service, after these long sermons, we have a song, and then all the nonmembers go out quiet as a mouse, and can you imagine yourself, a young boy or girl, and you have to get off your seat and walk up and sit right in front of the ministers, and you’re supposed to talk so that the whole church hears you and you get questioned about this thing. Can you imagine not giving up? [emphasis added]. That’s pretty impressive, it gets pretty strong.

The social pressure to confess is strong, but some confessions also become moments of healing that unite the congregation. A young couple, married for several years, asked the church to exclude them for six weeks because they felt guilty about their premarital behavior. A member described the experience: “They asked to be expelled, and so there was this six-week period of repentance. When they were reinstated as members it was such a sensational thing, and everybody felt that this couple really wanted to expose themselves and let the church know that they were sorry for what they had done and wanted to lead a better life. Everybody felt so good about it. It was really a healthy thing for the church. It was really a good feeling.”

Confession in front of the gathered body ritualizes an individual’s subordination to the group. It strikes at the heart of individualism and heralds the virtues of Gelassenheit. In its cathartic value, it bears a rough resemblance to modern psychotherapy, but it is less expensive and much more humiliating. In contrast to psychotherapy, most Amish confessions are initiated by the call of the church, not the individual. The ritual of Amish confession, one of the costs of community, has been largely untouched by modernity. A minister emphatically claimed that “not a thing has changed” in the confessional procedure over the years.

Corporations are not afraid to dismiss insubordinate employees, but contemporary churches, in the name of tolerance and love, are reluctant to dismiss deviant members. When confession fails, excommunication is the final recourse among the Amish. If baptism is the front door to Amish life, excommunication is the exit. The back door, however, is not slammed quickly. It can only be closed by the unanimous vote of a congregation after efforts to win back the deviant have failed. The German word Bann means ‘excommunication.’27 The English word ban is also used. From the internal perspective of Amish culture, the ban is designed to purify the body and redeem the backslider. The separation unites the community against sin, purges deviance, and reaffirms the moral order. In the same way that punishing criminals reaffirms the legal code of modern society, expelling sinners clarifies and rejuvenates the Amish Ordnung.

If persons refuse to come before the church to confess their sins, they will face excommunication. A congregational vote (der Rat) is taken to endorse a proposed expulsion. Hoping for the best, members may ask the deacon and minister to make a final visit with the offending member and plead for his or her return. If stubbornness persists, the congregation will eventually vote to excommunicate.

A final rite concludes the series of sad events. The deacon and a minister visit the wayward person and inform him or her of the church’s action. Following an old Benedictine formula, the elders repeat the following verse: “To deliver such an one unto Satan for the destruction of the flesh, that the spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord Jesus.” This quote from Luther’s German translation of 1 Corinthians 5:5 terminates the membership.28 If the member refuses to come to the door, the verse is repeated aloud outside the house.

Although expulsion sounds harsh to Moderns, who value tolerance, the Amish demonstrate considerable patience and leniency. A young farmer is given six months, until the next communion service, to remove the rubber tires from his tractor. A businessman using a computer is allowed to complete a major eight-month project before he must “put it away.” A family that buys an “English” house outfitted with electricity has a year of grace before the wiring must be torn out. In the case of adultery, divorce, or purchase of an automobile, excommunication is virtually automatic unless the deviant confesses the wrong. In most cases, ordained leaders display considerable patience as they work with their members and “try to win them back.”

If all else fails, the back door to the Amish house will close. An old bishop was fond of saying: “The ban is like the last dose of medicine that you can give to a sinner. It either works for life or death.” Leaders believe that errant members bring excommunication upon themselves by their stubbornness. But the back door always remains open a crack. Expelled members are always welcome to come back and will be reinstated if they are willing to kneel and confess their error. One man, excommunicated for dishonest business practices, decided to repent and confess his faults after nearly a year of exile. Others occasionally rejoin the church after many years. A senior bishop, in explaining the ban, emphasized the importance of love: “If love is lost, God’s lost too. God is love, doesn’t the Bible tell us God is love? And I sometimes think that love is worth more than fighting about this and that. You lose friendship through it.”

The doctrinal statement of the Amish emphasizes the importance of maintaining the church’s purity. “An offensive member and open sinner [must] be excluded from the church, rebuked before all and purged out as a leaven and thus remain until his amendment, as an example and warning to others and also that the church may be kept pure from such ‘spots’ and blemishes.”29 Although the theological intent of excommunication is to purge sin from the body, its social consequence is maintenance of the Ordnung. The ban is the ultimate form of social control. When mavericks sidestep the Ordnung or “jump the fence too far,” they are disowned to preserve the integrity of the moral order. Order, authority, and identity take precedence over tolerance. These practices may seem harsh to modern sensitivities, but even Moderns, who cherish tolerance, are ready to imprison criminals and expel dissidents, political traitors, illegal aliens, and insubordinate employees.

A unique feature of Amish excommunication is the practice of Meidung, often called “shunning.” As a reminder of the seriousness of their infractions, expelled people are shamed in ceremonial ways. Contrary to popular opinion, members can talk with persons who are under the ban, but certain forms of interaction are taboo. “Compared to other church disciplines, ours has teeth in it,” said one member. Meidung, the “teeth” of Amish discipline, is designed to bring the wayward back and to preserve the moral boundaries of the community.

Disagreements about the practice of Meidung helped to trigger the Amish separation from other Anabaptists in 1693. It has remained a distinguishing feature of Amish life. An Amish bishop explained: “In the Martyrs Mirror, you read that if there’s a ban and no shunning, it’s like a house without doors or a church without walls where the people can just walk in and out as they please.” The application of shunning varies in Amish settlements, but in principle, it remains a cornerstone of Amish polity.30

The Dordrecht Confession of Faith includes an article on shunning that spells out its theological justification:

If anyone whether it be through a wicked life or perverse doctrine is . . . expelled from the church he must also according to the doctrine of Christ and his apostles, be shunned and avoided by all the members of the church (particularly by those to whom his misdeeds are known), whether it be in eating or drinking, or other such like social matters. In short that we are to have nothing to do with him; so that we may not become defiled by intercourse with him and partakers of his sins, but that he may be made ashamed, be affected in his mind, convinced in his conscience and thereby induced to amend his ways.31 (emphasis added)

A statement by the Lancaster bishops calls for shunning members “if they behave in a way that is offensive, irritating, disobedient or carnal, so that they may be caused to turn back, or till they come out of their disobedience.”32

Shunning is a ritual of shaming that is used in public occasions and face-to-face interaction to remind the ostracized that they are outside the moral order. Shunning does not reflect personal animosity, but rather it is a ritual means of shaming the wayward and reminding everyone of the boundaries of membership. Conversation is not forbidden, but members may not shake hands or accept anything directly from the offender. However, members are encouraged to help, assist, and visit people under the ban.

Thus, shunning is an asymmetrical, one-way relationship. Members can help offenders, but offenders may not have the dignity of aiding a member. A grandmother who is a member may not accept her baby grandson directly from the hands of her shunned daughter. A check or a Christmas gift should not be accepted directly from a shunned person. Gifts, money, or payments from an offender, following the ritual formula, are placed on a table or counter and picked up by a member in a separate transaction. Members cannot accept a ride in the car of someone under the ban. Members of a volunteer fire company should not ride on a fire truck driven by a former member. Said one member about to face Meidung, “You suddenly lose all your security, and you become a goat, like a piece of dirt.”

The symbolic shaming also takes place during meals at weddings and funerals if shunned persons are present. The practice makes some family gatherings awkward. The banned person may attend but will likely be served at a separate table or at the end of a table covered with a separate tablecloth. In one case, an adult male who was shunned was excluded from the plans for his father’s funeral. Soon afterward, he decided to make amends with the church and return to the fold. A woman who persisted in attending a non-Amish Bible study was placed under the ban. Although continuing to live with her Amish husband, she eats at a separate table and abstains from sexual relations. Parents must shun adult children who are excommunicated. Brothers and sisters are required to shun each other.33 Members who do not practice shunning will jeopardize their own standing in the church.

The application of shunning varies widely from family to family. Many times it is relaxed in private homes but tightened in public settings if other church members are present, attesting to its ritual character and ceremonial role in the community. Many families treat family members under the ban with love and care in the privacy of their homes. Despite its theological purposes, shunning is a painful process. One woman said, “I’m not responsible for being born into a church that practices shunning. I have an uncle and aunt and cousins in the ban, and it may separate us on the social level, but it could never sever the cord of love.” Another person, whose parents are shunned, said, “Most people learn to live with it and not make a big deal of it. But it’s always there casting a shadow over all the relationships with people that are Amish.”

Excommunicated people are shunned until they repent. Upon confessing their sins, they are fully restored to membership in the church. But for unrepentant people, shunning becomes a lifetime quarantine. Amish-born people who never join the church are not shunned. Only those who break their baptismal vow by leaving the church or falling into disobedience are ostracized. Shunning places a moral stigma on the expelled because as “blemished” ones they have broken their baptismal vows and have turned their back on the church and God.

Meidung also clarifies an important principle in Amish life that is hard for Moderns to grasp. The church holds higher authority than the family. Individuals are accountable first to the church and then to their families. Only the church can divorce members. Only the church can separate families, because its authority reigns over all other spheres of life. Whereas in modern life the ranking of moral authority is individual, family, church; the order is turned upside down in Amish life. The threat of shunning is a powerful deterrent to disobedience in a community where everyone is linked by family ties.

The possibility of Meidung cautions those who would mock the church, scorn its Ordnung, or spurn the counsel of ordained leaders. To be shamed for life is no small matter when it means separation from family, friends, and neighbors. Meidung is a potent tool for social control. “It has holding power,” an Amish minister said. A former Amishman, shunned for more than fifty years because he joined a liberal church, said: “Shunning works a little bit like an electric fence around a pasture with a pretty good fence charger on it.” When asked about the ability of the church to hold its members, one person said: “That’s easy to answer, it’s the Meidung. If it weren’t for shunning, many of our people would leave for more progressive churches where they could have electricity and cars.”34

Shunning is the cornerstone of social control in Amish society. Baptism, communion, and confession are redemptive means to encourage compliance with the Ordnung. When those modes fail, the Meidung is there—a silent deterrent that encourages those who think about breaking their baptismal vows to think twice! Indeed, it is one of the secrets of the riddle of Amish survival.

Two cornerstones of Amish faith and practice give it credibility. Young adults clearly have a choice regarding church membership. In this way the church maintains the integrity of adult baptism. Second, those who are excommunicated are always welcome to return upon confession of their transgression. Sins that are confessed before God and the community are forgiven and as much as possible forgotten. These two features—the integrity of adult choice and full restoration of the wayward—lend credibility to the Amish story.

Amish rites of redemption and purification have stood the test of time and show few, if any, traces of erosion. They symbolize, rehearse, and communicate the essence of Amish culture. Kneeling for the rites of baptism, prayer, ordination, footwashing, and confession portrays the humble stance of Gelassenheit. The Amish have refused to yield their sacred rituals to modern individualism, with its easy tolerance of any behavior. Such a concession would surely erode their moral order. Their attempts to preserve order may seem legalistic and harsh at first blush, yet the personnel policies that shape the ethos of corporate and government bureaucracies are hardly less restrictive. The regulatory mindset is not unique to the Amish; they have simply applied it to the moral bedrock that undergirds their entire way of life.