Too much worldly wisdom is poison for the soul.

—Amish minister

Groups facing cultural extinction must indoctrinate their offspring if they want to preserve their unique social heritage. Socialization of the very young is a potent form of social control. As cultural values slip into a child’s mind, they become personal values—embedded in conscience and laced with emotion. Socialization legitimated by religion is more powerful than law in directing and motivating personal behavior. Concerned that the dominant culture will demolish their traditional values, the Amish carefully guide their children.

The Amish believe that the Bible commissions parents to instruct their children in religious matters as well as in Amish ways. For example, day care centers, nursery schools, and kindergartens are not permitted because children are to be taught by their parents. Child rearing is an informal process where children learn the ways of their culture through interaction, observation, and modeling. Unlike modern youth, Amish children have little exposure to diverse ideas and cultural perspectives beyond their family and ethnic community.

Given their fears of the outside world and their convictions about parental instruction, it is surprising that the Amish sent their children to public schools for more than a century. However, the peaceful coexistence was shattered in the mid-twentieth century when a bitter clash erupted between the Amish and state officials that resulted in dozens of arrests and imprisonment. What disrupted the century-long peace?

The rise of the Amish school system chronicles a fascinating dialogue between the Amish and the forces of progress. The Amish were willing to negotiate on some issues, but on the education of their children they refused to budge. Many parents paid for their stubbornness with imprisonment. Why were these gentle people willing to sit behind bars? Why did they resort to courts, petitions, and politics to preserve humility? Those intriguing questions thread their way throughout the story.

The voices of progress trumpeting the virtues of education were not about to be insulted by a motley group of peasant farmers. Through a variety of legal actions, the Amish were subpoenaed back to the bargaining table again and again.1 Finally, in 1972, the United States Supreme Court ruled in their favor, stating that “there can be no assumption that today’s majority is ‘right’ and the Amish and others are ‘wrong.’ A way of life that is odd or even erratic but interferes with no rights or interests of others is not to be condemned because it is different.”2 But that is getting ahead of our story.

“We’re not opposed to education,” said one Amishman. “We’re just against education higher than our heads. I mean education that we don’t need.” Indeed, for many years Amish youth were educated in public schools alongside their non-Amish neighbors.3 When one-room public schools were established in Pennsylvania in 1844, the eldest son of an esteemed Amish bishop was a member of a school board.4 The enforcement of compulsory attendance laws in 1895 stirred some criticism, but for the most part, the Amish supported public education in one-room schools.5 Even in the twentieth century, Amish children attended public elementary schools, and their fathers frequently served as board members. In fact, in some schools Amish children held the majority. Policies and curriculum reflected local sentiment. Teachers affirmed the rural culture, often their own, and complied with local requests. In rural Pennsylvania, children typically attended school about four months of the year. Providing a practical education in basic skills, local public schools were ensconced in a rural context that dovetailed smoothly with Amish culture. All of that was about to change as state officials, in the name of progress, decontextualized education.

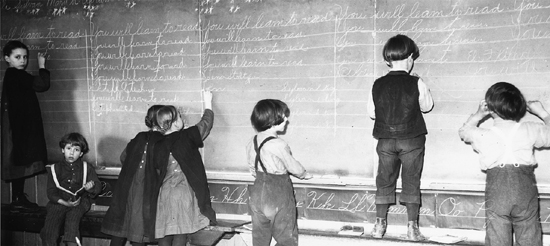

Amish children at the blackboard in a one-room public school ca. 1950.

The changes began in 1925, when the state legislature lengthened the school year. Eventually it raised the age of compulsory attendance, enforced attendance, and encouraged the consolidation of large schools. At first the Amish took the changes in stride. But when they realized that the forces of modernity would pull schools away from local control, away from their rural roots, the Amish began to resist.

Rumors of a new consolidated school agitated a heavily populated Amish township in 1925. A candidate for public office declared his opposition to consolidated schools and promised not to close any of the one-room buildings.6 Fears of consolidation were not illusions. The state was already paying school districts $200 each time they closed a one-room school. Indeed, over a twenty-year period (1919–39), 120 one-room schools were abandoned in Lancaster County alone.

Mushrooming interest in education prompted an Amishman to write four articles debunking “excessive” education in a county newspaper in 1931. In a rare public outcry, he contended that a common elementary education was enough for an agricultural people. “Among all the Amish people in Lancaster County,” he said, “you couldn’t find one who ever took any high school, college or vocational school education. Yet I don’t believe there’s a class of people in the entire world that lead a happier life than do our people on the average. For pity’s sake, don’t raise the school age for farm children . . . for if they don’t do farm work while they’re young they seldom care for it when they’re older.” Complaining of rising school taxes, he asserted, “I am in favor of public schools, but I am not in favor of hiring teachers at twice the salaries that farmers are making to teach our girls to wash dishes and to dance.” He then described a young, educated female acquaintance who unfortunately could not boil an egg even though she was “a bright scholar, a good dancer, busy attending parties, in fact very busy equipping herself to be modern flapper with lots of pep.” Concluding that experience is a better teacher than higher education, he said, “Brother, if you want an educated modern wife, I wish you lots of wealth and patience and hope the Lord will have mercy upon your soul.”7

The farmer’s fear of encroaching education was an omen of a confrontation that came to a head in 1937. A plan to abandon ten one-room schools in one sweep and replace them with a consolidated elementary building sparked the controversy. Induced by a federal grant, officials in East Lampeter Township, home of many Amish, began building the new school despite local objection. Incensed that the plans would place their children on school buses and in large classrooms with strange teachers, a coalition of citizens, largely Amish, organized themselves. Without the blessing of the church but with the help of Philadelphia lawyers, they obtained a court order in April 1937 to halt construction. The two-month delay was soon overturned by a higher court. Construction resumed, and the “newfangled” school opened in the fall of 1937. Some Amish children attended a one-room school that was still open, but others hid at home.8

In a surprising display of stubbornness, attorneys for the Amish renewed their fight in court. After meeting with Amish parents, Governor George H. Earle declared that he would reopen the ten one-room schools. The local school board balked, and the matter was tossed back and forth in a game of political ping pong for another nine months. The issue was finally settled when the U.S. Court of Appeals blessed the new school. In a conciliatory gesture, public officials maintained a one-room school for the Amish, but it only accommodated a few of them. The highly publicized dispute divided the larger community as well as the Amish themselves.9 Such aggressive use of the law was rare, if not unprecedented, in Amish history.

In the midst of the East Lampeter dispute, a more ominous cloud loomed over Amish country.10 School codes required attendance until age sixteen, but farmhands and domestic workers could drop out at fourteen. Hoping to bolster public education, legislators wanted to stretch the school term from eight to nine months and raise attendance age for farm youth to age fifteen. Such talk, on top of the recent strife, frightened Amish leaders. Raising the compulsory age to fifteen years for farmhands and extending the school year would deprive farmers of valuable help. Moreover, Amish youth would be bused to a large consolidated high school for a year until they were fifteen.

Frightened by the rumors, eight Amish bishops, representing all sixteen districts, petitioned a state legislator in March 1937 to “oppose all legislation” extending the school year and raising the age of compulsory attendance. The proponents of progressive education were not intimidated, however, by a few barefoot farmers. In July 1937, as the Amish began their wheat harvest, state legislators raised the compulsory attendance age for rural youth to fifteen and lengthened the school term to nine months. This action mobilized the Amish in a massive protest that would dwarf the ongoing dispute in East Lampeter Township. After finishing their harvest and watching the completion of the consolidated building, the bishops met in September to chart their course. Sure that the revised school code would “lead our children away from the faith,” they asked someone in each church district to tap local sentiment. Most of the members supported making a plea to state officials if it could be done in a “gentle way.” The opinion of a small minority was articulated by preacher Jacob Zook: “Better leave our fingers off; the Amish have stirred up enough stink for the present.”

Most of the Amish, however, wanted action. With tacit support from the bishops, sixteen delegates, preachers, and laymen met on 14 September 1937. They organized themselves and began a two-year struggle that would take them to legislative halls and the governor’s office. Calling themselves the Delegation for Common Sense Schooling, they hammered out a bargaining position with two key features. First, they would not send their children into the nurture and teaching of the world until they were grown. Second, they would send their children to public schools on four conditions: an eight-month school year, exemption after eighth grade, one-room schoolhouses, and teaching children the truth. After polishing a formal petition, the delegates launched a plan to gather sympathetic signatures and agreed “not to go to law, nor court, nor hire a lawyer.”

Armed with a thousand copies of their petition, the Amish canvassed for signatures in numerous townships among members and nonmembers. Public opinion split in response to the Amish plea. To haggle over one additional year of schooling seemed petty to many, but others applauded the Amish. In any event, the Plain folk were able to garner more than three thousand signatures of support, which they pasted into a 130-foot scroll. Moreover, prominent businessmen from several communities rallied in support of the Amish with their own petition.

Bearing their signed petition, Amish representatives visited Governor Earle. Surprised by the public outcry, he stalled by asking Attorney General James H. Thompson to investigate whether the new school law violated religious freedom. Shifting their tactics in the Thanksgiving season, the Amish tried some rural diplomacy on the governor. They presented him with a basket holding a dressed turkey, a gallon of cider, and an ear of corn—symbolic first fruits of the field, flock, and orchard—hoping he would reciprocate with leniency.

Despite their Thanksgiving offering, the Amish soon realized that their only recourse was to petition the General Assembly of Pennsylvania. So the Delegation for Common Sense Schooling wrote a new petition, “To Our Men of Authority,” hoping to persuade state legislators to change the statewide law. They pleaded again to have Amish children exempt from schooling after the eighth grade regardless of their age. “We do not wish to withdraw from the common public schools,” they concluded, but “at the same time we cannot hand our children over to where they will be led away from us.” The delegation also sent a pamphlet explaining their goals to Amish churches and promised that they would defend themselves “with the word of God rather than . . . with the services of a lawyer.”11

In December 1937 three events shrouded the traditional gaiety of the Amish wedding season. First, the consolidated East Lampeter school had opened its doors despite Amish protests. Second, their Thanksgiving offering, formal petitions, personal meetings with state officials, and pleading letters had not exempted Amish fourteen-year-olds from school. Many, in fact, were hiding at home. Third, the Amish learned that Moderns cherished education and would not cater to rural peasants. Amishman Aaron King, living on the settlement’s eastern fringe, was jailed for refusing to send his fourteen-year-old daughter to high school. King was convicted after a federal district court turned down his appeal in December 1937.12

The Christmas present that the Delegation for Common Sense Schooling had hoped to receive in exchange for their Thanksgiving offering had not arrived. Instead, they faced a frightening question: Would they be willing to sit in prison for the sake of their children? The new year opened on a bleak note. Attorney General Thompson declared that religious freedom and the rights of conscience could not obstruct the enforcement of law. In a blunt assessment of their bargaining clout, the Amish school committee concluded in January 1938 that “we got nothing.”

Writing a letter to Attorney General Thompson the next day, Stephen F. Stoltzfus, the head of the Amish delegation, said that his impatient delegates wanted “to take a stand, but I tried to cool them down and got them persuaded to just keep quiet and see what we get.” He ended by saying: “If we get nothing from our men in authority, we must do something ourselves. Why can’t the Board of Public Instruction show us leniency and exempt our children when they have a fair education for farm and domestic work? If we educate them for businessmen, doctors, or lawyers, they will make no farmers.” Hoping to avoid a public confrontation, the attorney general urged the Amish not “to do something drastic such as take a stand, as you call it.” Citing the rumors and publicity that would surely come if they “took a stand,” he admonished them to have “patience as taught in the Bible.”

By the late spring of 1938, Amish patience was dwindling. They discussed setting up private schools and decided to consult state officials. Public officials discouraged such schools and urged the Amish to bring their plea to the legislative assembly. The Amish proceeded on both fronts. They laid plans to open two private schools and to approach the State General Assembly. So in the midst of the July wheat harvest, the Amish were once again drafting a petition. After receiving the bishops’ blessing, 500 copies were sent to legislators and other public officials. Included with the petition was an amendment to the school code prepared for the Amish by the attorney general’s staff to allow fourteen-year-olds to obtain work permits. Thus, in May 1939 state legislators passed a measure permitting fourteen-year-olds to quit school for farm and domestic work. But by then the Amish had already opened their first two private schools—on nearly the same day that the ten one-room schools were sold on public auction.13

After two years of strenuous effort, the Amish had reached only one of their goals—work permits for fourteen-year-olds who had completed eighth grade. Accordingly, fifty-four permits were granted to Amish youth in the fall of 1939. The two-year battle had not achieved much, but it brought a gift in disguise. The struggle had forced the Amish to hone and clarify their educational philosophy for the first time. In the midst of intense bargaining, they had developed strong convictions about the nature of Amish education that would guide them in future battles for the minds of their children.

Some outsiders were dismayed by the Amish. Ralph T. Jefferson, an “educated” state representative from Philadelphia, wrote to the Amish and declared that “education is the greatest gateway to knowledge.” Displaying gross ignorance of Amish culture, he urged them to “turn on your radio, the water, the light, the heat, the gas, the electric, and turn your mind again to the electric churn, milker, sweepers, irons, and washers” as evidence of the fruits of education. Such counsel to the Amish was a superb example of the folly of higher ignorance!

Ironically, World War II gave the pacifist Amish a brief reprieve. The demand for farm products and the national preoccupation with the war put domestic politics on hold. In May 1943 new legislation gave local school boards more flexibility to issue work permits. The war also stalled construction of new Amish schools for another decade. Apart from minor skirmishes in local school districts, the battle for the minds of Amish youth was eclipsed by the war, and leniency prevailed.

The educational peace of the war years vanished in 1949. With the war behind them, educators and politicians across the country were more convinced than ever that public education was the key to keeping the world safe for freedom and democracy. In April 1949 new legislation raised the compulsory school age to sixteen, unless children were excused for farm or domestic work. A hidden clause gave the state superintendent of public instruction new power over work permits. The new law also required districts to bus students to high schools in neighboring townships if the district did not have a high school of its own. This sudden turn of events incited a bitter dispute between the Amish and public officials. Hundreds of Amish parents were arrested, and many were jailed until a compromise was struck in the fall of 1955.

Brandishing the new regulations, the state superintendent restricted work permits to “dire financial circumstances.” The permits had to be approved not only by local and county educators but also by the superintendent himself. As a final gesture of his determination to enlighten Amish citizens, he threatened to withdraw state subsidies from school districts that overlooked the new regulations.

These actions only crystallized the Amish resolve. At least two dozen Amish fathers were arrested in the fall of 1949 for refusing to send their fourteen-year-old children to school.14 Two fathers appealed the conviction, but a court decision upheld the Amish arrests by ruling that religious sects were not immune from compliance with reasonable educational duties.15 Provided with such legal ammunition, the Pennsylvania Department of Public Instruction opened a vigorous campaign to keep Amish youth in school.16

Meeting in February 1950, Amish bishops issued a fifteen-point statement, once again reiterating their traditional opposition to education beyond eight grades and fourteen years of age. Unlike earlier statements, this one was not addressed to legislators and did not plead for leniency. It merely spelled out their position and implied that this time they would “take a stand.” They would follow their conscience, and like Anabaptist martyrs of old, they were willing to suffer the consequences. One thing was certain in this round of negotiations—they would sit behind bars before acquiescing to educational progress.17

The bishops’ statement fell on deaf ears. In the fall of 1950, 98 percent of the work applications from Lancaster County were rejected by the Department of Public Instruction.18 Realizing that the state’s threat to withdraw financial subsidies was not a bluff, local school districts began arresting Amish fathers who refused to send fourteen-year-olds to school. Within a three-day period in September 1950, thirty-six fathers were prosecuted. Refusing to pay fines because, they argued, they were innocent, many spent several days in jail until they were bailed out by non-Amish sympathizers.19 Frontpage newspaper photos showed Amish entering the Lancaster County Prison. Bold headlines declared: “Dozens Go to Jail,” “Twenty Amish Violators Prosecuted,” and “Two Ministers Among Nineteen Sent to Jail.”

Some fathers are released from prison during the school crisis of the 1950s.

The arrests and jailing continued intermittently for five years. In Leacock Township alone, more than 125 parents were arrested, some of them five to seven times. One Amish father, arrested seven times, appealed his conviction as a test case in February 1954. Once again, a higher court sustained the conviction. This spurred a new round of arrests in the fall of 1954.20 The five-year confrontation was bitter. Public opinion split. Amish members of local school boards as well as some other members resigned. Still, many officials were annoyed that the obstinate Amish were making such a ruckus over one year of schooling.

In order to keep their fifteen-year-olds out of public high school, some Amish parents made them repeat eighth grade. Others held their children back from first grade so that they would be fifteen by the time they completed eighth grade. Still others decided to take a stand and suffer arrest and brief imprisonment. One township developed an “eighth-grade-plus” program so that Amish students did not have to go to public high school.

Not all Amish were willing to sit in jail. One Amishman recalled his experience as a fourteen-year-old after his father had taken him out of school: “We were in the field one day, and the constable came and served Dad some papers. I had three days to appear in school. The next morning Pop said, ‘You are going to school. I have neighbors all around me, and I am not going to sit in jail. I just can’t.’ He was looked down on by some. After repeating eighth grade again, I read a hundred books, everything from classic literature to a series of biographies of the leaders of our country. And the irony of it was that when we had to take our high school entrance tests, I had the highest mark in the whole county.”

Was there no escape from this bitter battle between modernity and tradition? After his adamant stand on work permits, the state superintendent could hardly renege on his policy. But he was also tired of the rancorous public opinion that scorned his interpretation. Finally, he conceded that “something might be able to be worked out within the law for both.” For their part, the Amish had chosen martyrdom over political action, and they were not about to lose face. As the arrests continued in the fall of 1953, the Amish bishops endorsed a proposal that promised to save face for everyone involved.

The Amish position congealed in December 1953, when the bishops and the Amish School Committee approved a proposal for a vocational training program for children who had completed eighth grade in a public school. The proposed solution appeased both parties. On the one hand, the state could say that Amish fourteen-year-olds were indeed in school; and on the other hand, the Amish were able to control the educational context and curriculum. After several delays and rounds of discussion, an agreement on the compromise was finally reached in 1955. With the blessing of the state, the six-year struggle ended when the Amish opened their first vocational school in January 1956 in an Amish home.21

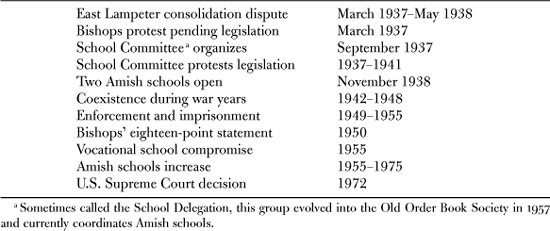

TABLE 7.1

Turning Points in the Amish School Controversy

Under the vocational program, an Amish teacher held classes three hours per week for a dozen or so fourteen-year-olds in an Amish home. The youth recorded their work activities and studied English, math, spelling, and vocational subjects. Attendance records were submitted to the state. But in essence the children were under the guidance of their parents for most of the week, an astonishing victory for the Amish.22 It was a victory that Lancaster County School Superintendent Arthur Mylin called “ridiculous.” Nevertheless, the vocational school arrangement continues today.

The inauguration of the vocational program silenced debate on high school attendance, but it camouflaged a more serious issue stalking the Amish—the consolidation of public elementary schools. Elementary consolidation was gaining momentum by the mid-1950s. The Amish refused to send their children to the consolidated schools or, in some townships, to new junior high schools.23 They had always resisted busing children to faraway classrooms with strange teachers and children, but it was the use of television in public elementary schools that incensed them, according to one Amishman. Beleaguered by political fights and imprisonment, the Amish decided to withdraw from the bargaining table once and for all and build their own schools. Thus, over the years, the Amish of Lancaster County have built and operated some 160 one-room elementary schools.

Back to our riddle: Why did the Amish, in the words of preacher Jacob Zook, make such a “big stink” about education? Why were these gentle people willing to be arrested, fined, and imprisoned? What provoked them to hire attorneys, lobby legislators, solicit signatures, and circulate petitions? A scrutiny of the statements they wrote during the struggle reveals their objections to modern education. In short, they did not want to lose control of education, to have it pulled out of their rural cultural context. For religious endorsement, they appealed to the Bible, the teachings of Christ, the examples of the apostles, the witness of Anabaptist martyrs, their Amish forebears, tradition, and conscience as well as religious liberty granted by the Constitution.

Numerous themes echoed throughout their litany of protest:24

(1) Location. The Amish wanted a local school, preferably one within walking distance. They did not want their children bused away.

(2) Size. They objected to large consolidated schools where pupils were sorted into separate rooms and assigned different teachers each year. The Amish repeatedly pled for the one-room school, which had served them so well in the past.

(3) Control. They believed that schools should be under the local community’s control. According to their interpretation of the Bible, parents were responsible for nurturing and training their children.

(4) Length. While they supported local one-room elementary education, the Amish felt that children belonged at home after the elementary grades. Parents also campaigned for a shorter (eight-month) school year so that children could help with spring planting.

(5) Teachers. They wanted teachers who were trustworthy and also sympathetic to Amish values and rural ways. The Amish refused, in their words, to just “hand their children over” to professional educators.

(6) Curriculum. They argued that high schools lauded “worldly wisdom,” a phrase they borrowed from the Martyrs Mirror. Worldly wisdom clashed with “wisdom from above.” A favorite scripture stated clearly that the wisdom of man was foolishness in the eyes of God (1 Cor. 1:18–28). Furthermore, knowledge “puffeth up” and makes one proud (1 Cor. 8:1). Citing still another scripture, the Amish insisted that worldly philosophy would spoil their children (Col. 2:8). Evolution, science, and sex education in the public school curriculum symbolized the vanity of worldly wisdom.

(7) Mode. Although they use textbooks in their own schools today, the Amish have always stressed the limits of “book learning.” They repeatedly argued for practical training guided by example and experience. They stressed learning manual skills, for they believed that they should earn their bread by the sweat of their brow. Book learning, they feared, would lead their youth away from manual work. They wanted an Amish equivalent of internships and apprenticeships supervised by parents.

(8) Peers. Too much association with worldly friends, they feared, would corrupt their youth and lead to marriage and other forms of “unequal yoking” with outsiders.

(9) Consequences. The paramount fear lurking beneath all the concerns was that modern education would lead Amish youth away from farm and faith and would undermine the church. The wisdom of the world, said Amish sages, “makes you restless, wanting to leap and jump and not knowing where you will land.” In the final analysis, they knew that modern education would deplete their cultural and social capital and, in the long run, ruin the church.

Religious reasons undergirded Amish objections to consolidated modern education. But could not these spiritual explanations be brushed aside for economic ones? Were not children essential to the maintenance of a labor-intensive farm economy? Both religious and economic factors partially explain the stubborn Amish resistance to modern education; however, a deeper reading of the bargaining sessions provides some additional clues to why these gentle people resorted to political action in order to preserve humility.

An Amish leader provided hints to the deeper reason for rejecting progressive education when he described Amish opposition to high school: “With us, our religion is inseparable with a day’s work, a night’s rest, a meal, or any other practice; therefore, our education can much less be separated from our religious practices.”25 An Amish farmer said: “They tell me that in college you have to pull everything apart, analyze it and try to build it up from a scientific standpoint. That runs counter to what we’ve been taught on mother’s knee” (emphasis added). Although few articulated it as eloquently as these people, the Amish realized that the consolidated high school, designed to homogenize different cultures, would also destroy them. Indeed, a major purpose of public education is to integrate diverse students into a common national culture.

The engineering logic of specialization and efficiency—so successful in producing radios and Model T Fords on the assembly line—was being applied to education, resulting in large educational factories for hundreds of students. Having rejected the Model T, the Amish also feared the new model of education. They intuitively grasped that modern schools would immerse their youth in mainstream culture. Such an education, outside an Amish context, would divorce Amish youth from their ethnic past. Despite their eighth-grade education, Amish parents realized that progressive education would fracture their traditional culture. Today dozens of one-room Amish schools, woven into Amish culture, stand as the antithesis of modern, specialized education.

An embodiment of modernity, the consolidated school was a Great Separator. High school education would separate children from their parents, their traditions, and their values. Education would become decontextualized—separated from the daily setting of Amish life. The Amish world, tied together by religious threads of meaning, would be divided into component parts: academic disciplines, courses, classes, grades, and multiple teachers. Even religion would be studied, analyzed, and eventually separated from family, history, and daily life. It would become just another subject for critical analysis. Professional specialists—educated in worldly universities and separated from the Amish in time, culture, and training—would be entrusted with nurturing their precious children. Such experts would encourage Amish youth to maximize their potential by pursuing more education to “liberate” themselves from the shackles of parochialism. By stirring aspirations and raising occupational hopes, the experts would steer Amish youth away from farm and family or would certainly encourage restlessness if they did decide to stay at home.

Passing from teacher to teacher and from subject to subject in an educational assembly line, Amish students would encounter bewildering ideas that would challenge their folk wisdom. The same teacher would not trace a child’s performance in several subjects or have the delight of seeing a student mature over several years. Moreover, Amish parents would be severed from the curriculum, policies, and authorities that would indoctrinate their youth. Abstract textbooks, written by distant specialists, would encourage intellectual pursuits that surely would turn manual labor into drudgery. Most importantly, public schools would plunge Amish youth into social settings teeming with non-Amish. High school friendships with outsiders would make it easier to leave the church in later years. Finally, high school would separate Amish children from humility. In an environment that champions individuality, they would become self-confident, arrogant, and proud. Academic competition would foster individual achievement and independence, which in turn would diminish Gelassenheit and sever dependency on the ethnic community.

In sum, the high school, a merchant of modernity, would sell young Amish a new set of values that would pull them from their past. The intellectual climate—rational thought, critical thinking, scientific methods, symbolic abstractions—would breed impatience with the slow pace of Amish life and erode the authority of Amish tradition. Amish youth would learn to scrutinize their culture with an analytic coolness that would threaten the bishops’ power. In all of these ways, high schools would cultivate a friendship with modernity and encourage youth to leave their birthright church. The Amish did not define the threat in such rational ways, but they understood its menace.

The goals of Amish education differ drastically from the agenda of contemporary education. Amish schools are designed to prepare Amish youth for successful careers in Amish life, not in mainstream society. By all accounts, Amish schools meet their objectives well. Amish schools create cultural and social capital by controlling the flow of ideas and social interaction. The schools build upon ethnic ties and stifle relationships with outsiders—all of which increases dependence on the church. The boycott of high school obstructs the path leading to marriage with outsiders, preparation for professional careers, and participation in civic life.

Abstract and analytical modes of thought are simply not encouraged in Amish schools. The teachers propagate ideas and values that undergird the ethnic social system. Overlapping networks of like-minded others within the small school insulate the child from rival explanations of reality and help to keep Amish ideology intact. The schools are an important link in the process of socialization that reproduces the values and structures of Amish society.

School children practice for a parents’ day program. Colorful chalk artwork is on the blackboard. The teacher is on the far right, her assistant is on the left.

To Moderns, this is indeed a provincial education that restricts consciousness—and so it is. But in a society where an expanded consciousness is not the highest virtue, Amish schools have ably passed on the traditions of faith to new generations. Indeed, they are one of the prime reasons for the growth and vitality of Amish life. These islands of provincialism may not stretch Amish consciousness, but they do provide secure and safe settings for the emotional and social development of children. And that is the solution to our riddle. In order to protect the meek ways of Gelassenheit, these normally gentle people had to bargain aggressively with imperialistic forces that sought to enlighten them with a worldly education, an education that in time might have destroyed them.

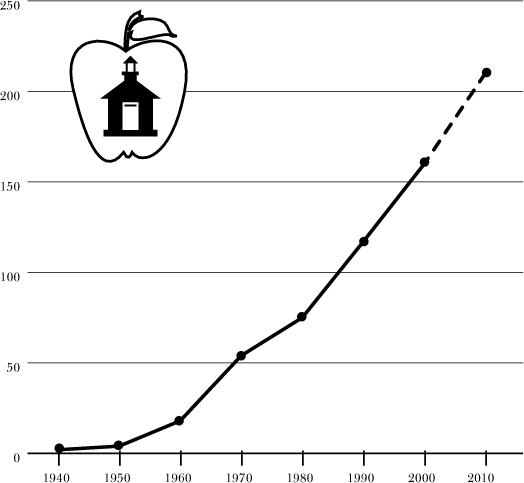

Today, with few exceptions, children in the Lancaster settlement attend one-room private schools staffed by Amish teachers.26 In some cases, the Amish bought one-room schoolhouses when the public townships discarded them. Most recently, they have built their own schools. However, the twenty-year transition to Amish schools (1955–75) provoked some internal debate. Some Amish parents wanted to send their children to public elementary schools to give them more opportunities to interact with outsiders. However, the interest of such parents in public education quickly waned upon the arrival of sex education, television, and the teaching of evolution. These developments prodded the rapid growth of Amish schools. In 1950 there were only three Amish schools, but by 1975 there were sixty-two.

Today more than 4,700 Amish pupils attend nearly 160 private schools in the Lancaster settlement, as shown in Figure 7.1.27 On average, thirty-one students attend the one-room schools, which are typically built on the edge of an Amish farm. Throughout eight grades they learn spelling, English, German, mathematics, geography, and history. Although taught by Amish teachers, classes are conducted in English. Practical skills, applicable to everyday Amish life, are emphasized rather than abstract and analytic ones. Science is excluded from the curriculum.

The values of obedience, tradition, and humility eclipse rationality, competition, and diversity. Whereas modern high school students write analytical essays, conduct scientific experiments, and learn to think critically, Amish youth prepare for apprenticeships in farming, crafts, business, and manual trades—where experience counts more than a degree. Devotional exercises—Scripture reading, singing, and repeating the Lord’s Prayer—are held each morning, but religion is not taught. To teach religion as an academic subject would objectify it and open the door for critical analysis. The Amish believe that formal religious training belongs in the domain of the family and church. They hope that religion permeates the school “all day long in our curriculum and in the playgrounds.” This goal is accomplished “by not cheating in arithmetic, by teaching cleanliness and thrift in health, by saying what we mean in English, by learning to make an honest living from the soil in geography, and by teaching honesty, respect, sincerity, humbleness, and the golden rule on the playground.”28

A one-room Amish school is a beehive of orderly activity as a teacher moves around the room teaching about thirty pupils in eight grades. Fresh cut flowers sit on the teacher’s desk, colorful chalk art decorates a side of the blackboard, smiley stickers adorn pages of completed homework, seventeen straw hats hang in a row on the back wall, and a paddle stands near the teacher’s desk. Some teachers work with two grades at a time. While some students come forward to work on the blackboard or recite answers, others quietly do their lessons or help each other. Hands are frequently in the air, asking permission to sharpen pencils, clarify an assignment, or go to the outhouse. Order prevails amidst the hum of activity, and students receive a great deal of personal attention from the teacher as well as help from peers. At recess a mother brings Popsicles to celebrate her daughter’s birthday. A middle-aged professional photographer seeing this sight for the first time was moved to tears as he muttered quietly, “This is the way it should be compared to our modern commotion.”

FIGURE 7.1 The Growth of Schools in the Lancaster Settlement, 1940–2010. Source: Blackboard Bulletin, November 2000. Estimate for 2010 based on current trends.

Amish schools lack the educational trappings taken for granted in public schools—sports programs, dances, physical education, cafeterias, field trips, clubs, bands, choruses, computers, guidance counselors, and principals. Even new Amish schools are copycat buildings—all constructed alike from an 1877 blueprint for a cost of about $35,000, which includes books and other supplies. Battery-operated clocks, gas lanterns, coal stoves, hand-pumped water, and outdoor toilets are the typical accessories in an Amish school. Many of the textbooks are produced by Amish publishers.29 Recess breaks in the morning and afternoon provide “time-out” for recreation. Spelling bees and recitation by class groups are common. Children usually carry their lunches in colorful plastic lunch boxes. Since 1975 the Amish have also operated several “special schools” for students with various physical and learning disabilities.30

Amish parents control their schools. They elect a three- to five-member school board that oversees the school’s operation. In some cases a board may administer up to three schools. The school board hires and fires teachers, maintains the building, and advises on curriculum. Other parents are involved with the school through visits, work “frolics,” and special programs. The Amish support their own schools through two taxes collected by the treasurer of the board. Members pay a head tax to support the schools, and in addition, parents pay a fee for each pupil. On the average it costs about $400 per year to educate an Amish child, about one-twentieth of the $8,000 it costs to educate one in a local public school. Nevertheless, the Amish in Lancaster County also pay millions of dollars each year in real estate taxes to support public education. In contrast to some public schools, where parents are kept at arm’s length by professional educators, Amish schools give parents free access to the curriculum, instruction, and administration. In all ways, the schools are locally owned and operated.

The teachers are typically single Amish women who were educated through the eighth grade in Amish schools. Teachers typically earn $40 to $50 per day, or about $8,000 per year. This is about one-sixth of the pay of their public school counterparts, not to mention their lack of benefits. They are not state certified but are selected on the basis of their natural interest in teaching, their academic ability, and their endorsement of esteemed Amish values—faith, sincerity, and willingness to learn from other teachers.31 Whereas modern school administrators recruit teachers on the basis of degrees, certification, and professional skills, the Amish believe the foremost qualification is “good Christian character.”32 Ironically, these nonprofessional Amish teachers—free of the typical restrictions imposed by principals, professional organizations, and bureaucratic classroom policies—have great latitude to shape curriculum and policies according to their best judgment.

Students enjoy the delights of community over lunch.

The Old Order Book Society provides guidelines for curriculum and administration to encourage uniformity across the schools.33 Amish teachers must support church values, but in contrast to professional teachers, they have an astonishing amount of freedom to shape their instructional setting. Typically, teachers are on probation for the first three years until they have proven themselves.34 Each year several countywide teachers’ meetings provide opportunities to receive teaching tips from experienced teachers. In addition, an Amish teachers’ magazine, the Blackboard Bulletin, is a helpful source of ideas and encouragement for teachers. In Amish schools, cultural integrity triumphs over specialized expertise.

What are the outcomes of Amish schools? Research evidence from other settlements suggests that, on the average, Amish students perform as well as other rural non-Amish students in basic quantitative skills, spelling, and word usage.35 While Moderns ask whether Amish schools compare favorably with public ones, the more important question is how well an education prepares pupils for adulthood in their society. On that issue, Amish schools fare as well as if not better than many public schools. The vitality of Amish culture certifies the ability of its schools to prepare its pupils for a successful life in Amish society.

The social continuity in an Amish school is astonishing. In some instances, all the children in one family will have the same teacher for all eight grades. And unlike modern children, who may have as many as fifty different teachers by the time they graduate from high school, many Amish children have had only one teacher. Parents relate to one teacher, who over the years develops a keen understanding of the family’s idiosyncracies. A teacher may relate to as few as ten families in a school year because several children come from the same family. Older children tutor younger ones. On the playground, like-minded Amish play together with cousins and neighbors, insulated from the contamination of outside culture. In the Amish school, sacred and secular, moral and academic, spiritual and intellectual, public and private spheres are not mixed together; they have never been separated.

Although some may occasionally take high school correspondence courses, Amish children rarely attend high school. Even Amish teachers are urged to prepare for teaching through self-education rather than correspondence courses. Young shop workers occasionally take short courses in specialized mechanics, but few Amish youth aspire to go to high school. Describing high school, a minister said: “There’s no longing for it, no call for it. It’s rarely mentioned. I don’t know of anybody who would want to go.” For the occasional youth who does attend high school or college, separation from the church is painful if the youth is a member.

A professional social worker, excommunicated by the Amish church prior to her senior year in college, described trying to dissuade her bishop from excommunicating her: “He was a just and deeply caring person. I met him out in the field. I asked questions about education and sin and tried my best to make him understand that I wanted to continue both my education and my membership in the Amish community. He would not say that further education was a sin and he agonized in his efforts to explain why excommunication was necessary if I would not repent. Both of us were sensitive and hurt deeply; we cried unashamedly.”36

The relationship between the Amish and public education officials mellowed after the Amish received the blessing of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972. Some legislators share pending regulations with Amish leaders for reaction and counsel. In some cases, informal agreements spell out mutual expectations. Amish schools, for instance, are typically heated by coal stoves in the classroom because they rarely have basements. Building basements for the sole purpose of housing furnaces would have been quite costly. However, state fire regulations prohibit furnaces in open classrooms. After several discussions, state officials agreed to overlook the furnace requirements. In addition to heating systems, a variety of other issues have been quietly solved behind the scenes with state officials over the years in favor of the Amish—water testing, teacher certification, attendance reports, immunization, Worker’s Compensation, and unemployment benefits among others.37

In the mid-1980s new regulations called for schools to be state certified. This was a rather perfunctory process for the Amish. According to an Amish spokesman, state officials agreed to honor past informal agreements and not impose new regulations if the Amish, in turn, would agree not to obstruct the pending legislation. Free to set their own standards, the Amish designed and printed their own certification forms. A few descriptive facts on each school are reported on the certification form, which is sent to the state each year. Schools are required to be open 180 days a year. “For many things,” an Amish spokesman said, “it is better if we don’t even ask state officials because it just puts them on the spot.” The bitter struggles of early years have been replaced with benign neglect and mutual respect.

All things considered, the Amish have held the upper hand in the thirty-six-year dispute that finally ended with the U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1972. Following that decisive judgment, the Old Order Amish Steering Committee “fully accepted and approved” the Supreme Court’s ruling, leaving no doubt about the hierarchy of judicial authority in Amish minds.38 The only issue they had to concede was a longer (180-day) school year. Even so, with fewer holidays and shorter vacations, Amish schools are able to end early to honor spring planting. Thus, on all the key issues—location, size, control, compulsory age, and curriculum—Amish convictions held sway.

In March 1989, President George Bush and drug czar William Bennett visited Lancaster County to promote a national campaign against illegal drugs. After making a speech at a local high school, the president’s entourage met with Amish and Old Order Mennonite leaders in an Old Order school.39 Meeting with Old Order leaders in a simple classroom without television cameras, the president said, “We came here to salute you” because the national drug problem is “hopefully nonexistent” in communities like yours.40 He was wrong.

According to one Amishman, a few Amish youth had begun dabbling with drugs in the 1970s. The problem hit the national press in the summer of 1998 when two Amish boys were arrested for dealing cocaine with the Pagans motorcycle gang. The sensational story prompted a feeding frenzy by the national media as news of the story spread.41 Television, newspapers, and news magazines from around the world covered the story, almost with glee, at the discovery of sin among the Amish. Parents and elders were embarrassed by the stigma and the media attention. Some of them were quick to note that although the two lads had been raised Amish, they were not members of the church and thus were “really not Amish.” The two men were eventually sentenced to twelve months in prison with immediate work release privileges, a sentence that some Amish considered far too lenient.

The whole event was a sobering wake-up call for the church and for many Amish teens as well. Indeed, the crop of baptismal candidates hit an all-time high in the fall of 1998, when more than four hundred entered the church. Concerned parents, in cooperation with the FBI, helped to arrange a series of informal meetings in the Amish community to tell Amish parents and teens about the dangers of drugs. The sad episode reminded church leaders that the evils of the world were not always found in faraway places but were sometimes lurking behind their own barns.

The arrested youth and their drug-using friends are a small minority within the Amish community, but they pose a perplexing riddle. Why do the Amish, who fought so hard for the right to teach their children, permit rebellious teens to flirt with the world? And why do some youth, educated in the ways of obedience, turn to mischief just a few years later? Rowdy youth are an embarrassment to church leaders and a stigma in the larger community. The rebellious antics, often called “sowing wild oats,” have become a rite of passage for some youth during rumspringa, the “running around” years that begin at age sixteen. In some cases, the mischief is carefully hidden from parents; but in other instances, church rules are openly mocked. Sometimes Amish parents, themselves constrained by the rules of the church, may vicariously participate in their offspring’s misconduct. Although all Amish youth join a gang and “run around” before marriage, the majority of them enjoy their freedom in fairly traditional and quiet ways.42

An unbaptized Amish youth dressed in contemporary clothing adjusts the sunroof on his car.

Rumspringa is an awkward moment in Amish life—a liminal stage when youth are neither in the church nor out of it. They are truly betwixt and between; no longer under the control of their parents, yet still free from the church. Although socialized in an Amish environment, they have not taken their baptismal vow. Amish leaders, chagrined by the worldly behavior of some teens, point out that they are helpless to control the problem because the youth are unbaptized. They attribute this slippage in the social system to poor parental guidance and lax enforcement.

To both insider and outsider, the rowdiness appears, at first glance, as a tatter on the quilt of Amish culture. There is, however, a compelling sociological explanation for this persistent tradition. Most of the rowdy youth eventually settle down to become humble Amish adults. There are exceptions, but for the most part the youth that flirt with the world eventually return to the church. Flirting with the world serves as a form of social immunization. Teenage mischief provides a minimal dosage of worldliness that strengthens resistance in adulthood. Indeed, this apparent quirk in Amish culture has a redeeming function in the social system that may partially explain its persistence.

A fling with worldliness gives Amish youth the impression that they have a choice regarding church membership. The open space before baptism underscores the perception that they are free to leave the Amish if they choose. The evidence, however, suggests that the perceived choice is partially an illusion. Amish youth have been thoroughly immersed in a total ethnic world with its own language, symbols, and worldview. Moreover, all of their significant friendships are within the Amish community. To leave the Amish fold would mean severing cherished friendships and family ties, although if unbaptized, they would not be shunned. Rejecting their birthright culture would thrust them into an entirely different world—a foreign world and a foreign culture. Even on escapades to faraway cities, Amish youth travel together. These portable peer groups insulate even the would-be rebels from the terror of a solitary encounter with the larger world.

In many ways, Amish youth do not have a real choice because their upbringing and all the social forces around them funnel them toward church membership. This is likely why more than 90 percent of them do, in fact, embrace Amish ways. A few youth do not join the church, and they appear to fare quite well as they move into mainstream society. But for the majority who do join, the illusion of a choice serves a critical function in adult life. Thinking they had a choice, adults are more likely to comply with the demands of the Ordnung later in life. Members might reason this way: After all, because I chose to be baptized and vowed on my knees to support the church with the full knowledge of its requirements, I should now be willing as an adult to obey the demands of the Ordnung.

Without the perception of choice—the opportunity to sow wild oats—adult members might be less willing to comply with church rules, and in the long run this would weaken the community’s ability to exercise social control. Many rowdy youth are “reaped” later by the church in the form of obedient adults who willingly comply with the Ordnung because they believe they had a choice. Thus, the wild oats tradition yields a rich harvest for the church—a cornerstone in the group’s ability to develop compliant adults. And that may be the reason that parents who were willing to suffer imprisonment for the sake of their youths’ education are also willing to let them flirt with the world.