We’re not just backwoods dirt farmers anymore.

—Amish shop owner

In the later part of the twentieth century, the Amish experienced two transformations that had the potential to destroy or bolster their destiny. Sweeping changes in the broader society forced them to grapple with two simple, but profound questions: Who will educate our children? How will we earn a living? Over the years, the answers would determine their fate. Public school consolidation and scarce farmland placed these questions on the bargaining table. The Amish would have preferred the serenity of the past, but the forces of progress were relentless. As we have seen, schooling was nonnegotiable. They refused to relinquish the education of their children. The question of work, however, was different.

At first, the Amish refused to bargain, but gradually they agreed to deal. Ironically, they had refused to budge on public education for fear that it would lead them off the farm. Yet a few years later, a bleak economic scenario led them to hedge on their commitment to farming. Why were they willing to abandon the soil after plowing it for almost three hundred years? What factors led to this historic agreement, which could bring their cultural demise?1

The Amish have always been a people of the land. Ever since persecution in Europe pushed them to rural isolation, they have been tillers of the soil—and good ones.2 The land has nurtured their common life. They have been stewards of the soil—plowing, harrowing, fertilizing, and cultivating it. The springtime fragrance of freshly plowed ground energizes them. They pulverize soil in their fist to test its level of moisture. Whereas all soil looks like dirt to city folks, the Amish have an eye for good soil. The rich limestone soil of Lancaster County, like a magnetic force, holds their community together and ties them to their history. They have tenaciously clung to the soil and have purchased more of it whenever possible.

“Agriculture,” according to one leader, “is a religious tenet, a branch of Christian duty.” The divine injunction to Adam in Genesis “to till the ground from which he came” provides a religious mandate for farming.3 The Amish believe that the Bible instructs them to earn their living by the sweat of their brow. Tilling it ushers them into the presence of God. “I don’t know what will happen if we get away from the soil,” a young farmer said. “I can see where it’s not a very good thing. You get away from working with the soil and you get away from nature and then you are getting away from the Lord’s handiwork.”

Another member argues that the Amish were unable to establish a stable life in North America until they began farming the rich soils of Lancaster County, where they could “live together, worship together, and work together.”4 A businessman explained that “good soil makes a strong church” but worries that a paradox lies below the soil’s surface. “The best soil,” he said, “holds the best people and makes them a faster people and they become prosperous and the prosperity is not good for the church and so it gets you coming in the back door.” He believes that the vitality of the Amish community depends on the quality of the local soil. But he fears that the prosperity germinating in the land will, in the long run, ruin the church with luxury.

An Amish woman who left a farm said, “Leaving it means leaving part of my soul. When you’ve tilled the soil for generations, the feel of it can never be left behind.” Describing her former garden, she said, “On each side were wooded areas. The soil was very good, with a sand-like substance. The garden grew veggies, watermelons, and grapes to perfection. And how I loved it!”

Although the Amish delight in working in it, the soil is not an end in itself; it is the seedbed for Amish families. A persistent theme, extolled by virtually all Amish elders, praises the farm as the best place to raise a family. Even the owners of booming Amish industries repeat the litany of praise for the family farm. Despite satisfaction in their thriving enterprises, businessmen worry about the fate of their grandchildren, growing up away from the farm. Farms provided a habitat for raising sturdy families. Parents and children worked together. Daily chores taught children personal responsibility and the virtue of hard work. Parents were always nearby—directing, supervising, advising, or reprimanding. Pitted against the forces of nature, families forged a strong sense of identity and cohesion. Moreover, the demands of farmwork kept young people at home and limited interaction with the outside world. The family farm was the cradle of Amish socialization—a cradle that until recently held the core of their way of life.

Although farming has always been foremost, some Amish settlers had worked as millers, tanners, and brewers. A few Amish have always worked in traditional crafts, such as blacksmithing, carpentry, painting, watch repair, and furniture making.

Nonfarm work evolved gradually after the Depression of the 1930s. As cars gained widespread acceptance and horse travel declined, the Amish developed their own carriage and harness shops and began shoeing their own horses. Amish shops also began repairing horse-drawn machinery in mid-century as tractor farming gained in popularity among other farmers. A few small carpentry shops also developed in the 1950s. The third phase of nonfarm work evolved in the 1970s, when more sizeable cabinet and welding shops emerged.5

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Amish were caught in a demographic squeeze. Their population had doubled between 1940 and 1960. To accommodate their growth, they bought more farms in the center of the settlement and also began moving into southern Lancaster County.6 In fact, one public official reported that between 1920 and 1940 the Amish bought every farm on public sale near the hub of their settlement except one, which was sold on a Sunday.7 The pressure peaked in the late 1960s when eighty young couples started housekeeping in one year and only ten farms were sold on the open market.8

The Amish were not the only people desiring land. Lancaster County was the fastest growing metropolitan area in Pennsylvania between 1960 and 1970. Suburbs began nibbling away at prime farmland. The number of tourists jumped from some 1.5 million in 1963 to nearly 4 million a decade later.

Lancaster County was enticing new industry because of its dependable, anti-union labor force as well as its proximity to eastern metropolitan markets. Some thirty-six new industries entered the county between 1960 and 1970.9 They, of course, needed land and attracted employees who needed housing.

All of these factors increased the squeeze on farmland. The cheap land of the Depression years had turned into gold. In 1940 the Amish were paying between $300 and $400 per acre for farmland.10 By the early 1970s, farmland had escalated to $2,000 per acre, and it more than doubled again to $4,550 per acre by 1981, and again to $10,000 per acre by 2000.11 The Amish found themselves in a serious quandary by the mid-1970s: How could they farm without land? At first blush, tourism, suburbs, and industrial expansion were the likely culprits, but that was only half the story. Even if development had frozen, the rapid growth of the Amish themselves would have forced the crisis. In short, there were simply too many babies for too few farms.

Without a high school diploma, the Amish could not pursue professional jobs. If they left the farm, their training held them to manual work. By 1960, some Amish were already working in shops, warehouses, and even factories. Higher wages made nonfarm work so attractive that a few even rented out their farms to take on “outside” jobs. Church leaders were alarmed. A bishop contended that “the lunchpail is the greatest threat to our way of life.” Working in factories was not only frowned upon, it was in fact a test of church membership in the 1940s. In the school controversy of the late 1930s, the Amish repeatedly promised state legislators that they would keep their youth on the farm. Indeed, church members were excommunicated in that era if they worked in cities or nonfarm jobs.12

When some Amish began leaving the farm in the 1970s because of scarce land, a bishop worried: “Leave this one generation grow up off the farm, and their sons won’t want to farm.” In 1975 another bishop articulated his fears this way: “Past experiences have proven that it is not best for Amish people to leave the farm. If they get away from the farm they soon get away from the church, at least after the first generation.”13 The lunchpail threat intensified in the 1960s when mobile home factories were built on the edge of the Amish community to attract hardworking, anti-union Amish and Mennonite employees. By the early 1970s, more than one hundred Amishmen were carrying their lunchpails to several nearby plants. But a few years later, an economic recession closed several of the trailer factories, to the quiet applause of Amish leaders.14

FIGURE 10.1 The Demographic Crisis in the Lancaster Settlement

Why did the factory system, symbolized by the lunchpail, frighten Amish leaders? First, they believed that removing the father from the family during the day would weaken his influence. Without watching their father at work, Amish youth would lose a significant role model. Furthermore, fathers could not supervise children from a factory. Second, the factory might subvert the father’s own values. Worldly values, conveyed by non-Amish employees, would undoubtedly tarnish even the most faithful member who spent five days a week in a foreign culture. Third, factory employment threatened community solidarity and social capital. Personnel policies, time cards, and production schedules would make it difficult to participate in community events such as funerals, weddings, barn raisings, and other mutual aid activities. Fourth, the fringe benefits of factory employment—health insurance, retirement funds, and life insurance—would undermine a community that thrived on mutual dependency. With such perks, who would need the support of the church?

The factory, in short, would fragment the family, deplete social capital, and eventually ruin the community. An elderly bishop summed up the dilemma: “It’s best for a Christian to be on the farm. When they carry a lunchpail and go to a factory and some places it’s not too good, men and women working together and so on. We’d rather have them on the farm but the land just doesn’t reach around anymore.”

Compared to the stormy school crisis of the 1950s, the occupational quandary of the 1970s was a quiet battle with little publicity or government meddling. But the long-term consequences of Amish work were just as important as schooling. Amish sages knew intuitively that factory work was dangerous. Even some experts predicted that without agriculture, “it is doubtful the Old Order Amish could survive.”15 Nevertheless, the babies kept coming as the acres declined. Was there no escape from the dilemma? The U.S. Supreme Court would not bail the Amish out this time; they would have to find their own way out. Given the harsh facts on the bargaining table, the Amish—with great reluctance—decided to talk.

Was there any middle ground between the stark choice of factory work or financial collapse? There were a variety of alternatives: birth control, migration out of the United States, migration to other regions of the county and state, subdivision of farms, and nonfarm work. Birth control was not a likely option. Although the church had no official position, artificial contraception was generally considered interference with God’s will and the natural order. Despite those sentiments, some families use various forms of birth control; however, sizeable families of five to seven children remain highly esteemed. Migration to other countries was never discussed, but the other alternatives were thinkable.

In the midst of the school controversy in the early 1940s, new colonies were established in Lebanon County, some forty miles north of Lancaster, and in St. Mary’s County, Maryland.16 But for the next twenty-five years, Amish migration to other counties stalled. In the 1950s, the Amish began to sprawl southward in Lancaster County, but by 1980 land was becoming scarce there as well. Migration within the county provided only temporary relief from the demographic squeeze. In the mid-1960s, land pressures as well as internal unrest prompted some families to start new settlements in other counties of the state.17 Land in the new areas could often be purchased for one-fourth its price at home, enabling a farmer to sell a Lancaster farm and buy three or four elsewhere. Nearly a dozen new settlements were spawned from Lancaster by 1980, as shown in Appendix D.

The outward migration abated in the early 1980s, but by then roughly 15 percent of the Lancaster settlement had moved to other counties of the state.18 Outward migrations began again in the 1990s—this time to Kentucky, Indiana, Wisconsin, and elsewhere. Indeed, by 2000, some 10,000 descendants of Lancaster were living in twenty-eight other settlements. But the migrations still did not relieve the pressure of growth at home.

Subdividing farms provided a second solution. A farm of seventy acres, divided in half, could support two families. Larger farms were sometimes split into three sections. A new house and barn were often erected on each section. A subdivision was frequently accompanied by a shift to specialized farming—vegetable farming, game animals, dog breeding, chickens—that required less land so the family could still cling to the farm, or at least to a corner of it. Outward migration and the subdivision of farms kept families on the land and perpetuated their home-based culture. But these adjustments were not enough.

With the friendly options exhausted, the Amish were finally forced to negotiate. Unwilling to leave Lancaster County en masse, they began to search for nonfarm work. It was not a formal decision by any means, but by 1980 the signals were clear—the Amish would leave the farm rather than migrate. By the 1980s, they were pressuring township supervisors for commercial zoning in the hub of their settlement—a sure sign that they had decided to shift occupations instead of to flee.

Although the Amish were willing to negotiate the type of work, they refused to budge on the conditions of employment. First, they wanted to work at home or as near to it as possible. Second, they wanted to control the nature and content of their work. Third, they insisted that the work, whenever possible, stay within their ethnic environment. Finally, the work had to remain within the moral order of Amish culture. For example, photography, television repair, jewelry shops, and hair dressing were unthinkable.

Rejecting the lure of factory jobs, the Amish reluctantly agreed to leave the farm if they could retain control of their work. Small shops based at home made a perfect compromise. The Amish would leave their plows behind, but they would not work in large industrial factories owned by outsiders. Instead they would create their own Amish mini-factories—small shops and cottage industries—and keep them nearby home.

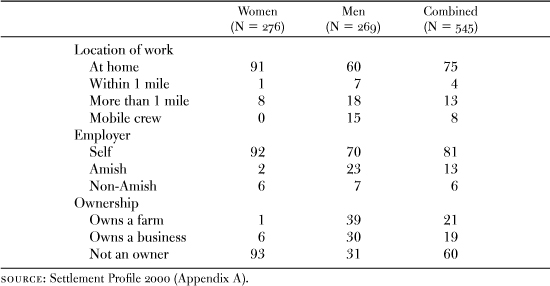

TABLE 10.1

Primary Work of Adults (aged 25–65) by Gender (in percentages)

Today, about two-thirds of the Amish have abandoned their plows, but some of their jobs support the farm economy.19 Involvement in nonfarm jobs varies greatly among church districts. In the heart of the settlement, with scarce land and easy commercial access, nonfarm jobs climb beyond 90 percent in some districts. In more rural areas, on the southern fringe of the county, the majority of men are still farming.20 The percentage of men involved in farming varies by age. About half of the mid-age men are farming, but only a third of those who are under thirty or over fifty years of age are tilling the soil. Nearly 85 percent of adult women consider homemaking their primary work, but many of them have secondary jobs related to crafts, quilts, produce markets, retail stores, or domestic work. About 15 percent find their primary employment in such roles.

The location of Amish work is cross tabulated by gender in Table 10.1. Perhaps the most striking fact is that although fewer Amishmen are plowing fields these days, 60 percent of them are still working at home. Among women the number working at home rises to 91 percent. About 15 percent of the men, but none of the women, travel with mobile construction crews.

Many people are working at or near home even though they are working in cottage industries and retail stores. Thus, despite the transformation, Amish work, for the most part, remains near home.

Even more striking in light of societal trends, married women still work at home. One Amishwoman was very blunt: “You shouldn’t be in business if you’re married.” It is rare to find married women with children who hold a full-time job outside their homes. Many mothers have sideline jobs—such as quilting, baking, craft work, and sewing—but these are usually based at home. Many women are involved in the quilting industry, which often involves several operations at different locations as well as “middle women” who buy and sell quilts.21 Women and children often tend small roadside stands on their property that sell produce, baked goods, and crafts to tourists and non-Amish neighbors. Some married women hold part-time jobs cooking in restaurants or tending market stands in urban areas several days a week. Increasingly, women are becoming involved in a variety of businesses. Indeed, 17 percent of the hundreds of Amish businesses are owned by women.22

Many single females hold a full-time job away from home. Young women who work before marriage and older single women are typically employed outside their home. One older woman harnesses her horse on Sunday morning to travel to church, but on Monday she walks to a small real estate office where she works as a receptionist. She operates the office computer, which in a split second can display real estate listings throughout the country. The more typical pattern is for single women to work as teachers, cooks in restaurants, domestics in motels, bakers in bakeshops, or salesclerks in Amish stores and market stands. Others clean the homes of their non-Amish neighbors.

Farmers often retire at a young age to allow a son to take over the farm. After retirement, a grandfather or grandmother may set up a small shop on the farm for supplemental income. Whenever possible, a father “gets out of the way” so a son can raise his family on the farm, until the process repeats itself in the next generation.

Perhaps even more important than location is the context of work. Amishmen who work away from home carry lunchpails, but not to factory jobs—70 percent are self-employed, and 23 percent work for an Amish employer. Thus, more than 93 percent of the men work in an Amish environment, as shown in Table 10.1. “Where,” asked an Amish businessman rhetorically, “is the best place for these Amish boys to work if they can’t all farm? In a big factory or tobacco warehouse in Lancaster City, or in a small shop with an Amish boss and other Amish employees?”

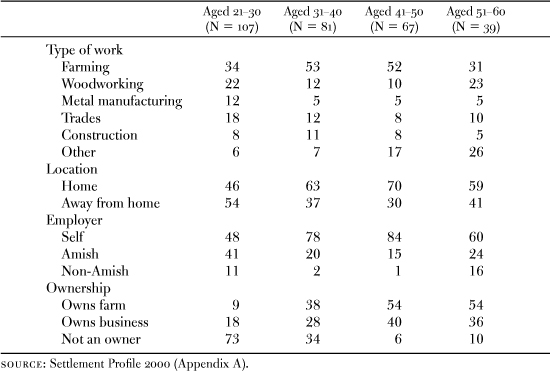

TABLE 10.2

Primary Work of Adult Men by Age (in percentages)

Those who are not self-employed or working for fellow Amish may be part of an Amish work crew employed by a Mennonite or other Plain-dressing employer. Still others, employed by non-Amish employers, typically work side-by-side with fellow Amish. The Amish rarely work outside of ethnic networks.23 In the final analysis, although 40 percent of Amish married men work away from home, they usually toil in an ethnic cocoon, which defuses the lunchpail threat. A few work outside the cocoon, but the number is minuscule.24 Even non-Amish employers are usually local people who are sympathetic to Amish values and willing to adjust to community concerns in exchange for conscientious work.

Given the crescendo of nonfarm jobs in recent years, it is surprising to find so few differences between age groups in Table 10.2. Men under age thirty are more likely to work away from home in nonfarm jobs and less likely to be self-employed than older men. Thus, while nonfarm jobs have increased dramatically in some church districts, the Amish have not relinquished control over the conditions of their work. They were willing to dicker with modernity over the type of work, but they were not about to negotiate its location, control, or ethnic setting.

In some ways the turn of the twenty-first century brought the best of times and the worst of times. Tobacco prices were in the cellar, and milk prices hit the dump of a thirty-year low, strangling the income of farmers. Searching for new ways to squeeze an income out of their land, more farmers began raising vegetables, flowers, organically grown chickens, exotic wild animals, and puppies for pet stores. Others were experimenting with yogurt and cheese products. Near Quarryville, about two dozen Amish farmers formed a milk cooperative. They bought milk processing equipment from Israel with hopes of making kosher milk products—yogurt and cheese—for Orthodox Jews in New York City.

Meanwhile, businesses were pulsing with profits, enticing more and more farm boys to abandon their cows and plows. In the heart of the settlement, one observer counted ten dairy barns with empty stables. The Amish were still farming the land, but they had turned to their shops for their primary income. In another township, a farmer sold his cows and rented his land to a non-Amish farmer so he could build storage sheds. A non-Amish neighbor worried about these ominous trends that “might destroy the Amish way of life.” The economic woes of farming made the good fortunes of business even more attractive to aspiring young lads. Farming required an enormous investment for land, animals, and equipment. It was simply easier, cheaper, and more profitable to set up a shop than to go into farming.

An ironic turn followed the sagging fortunes of farmers. The wealthier businessmen were beginning to amass enough capital to buy more farms. One business owner was pleased that he could buy a farm for each of his four daughters. Between 1984 and 1996 the Amish bought nearly 180 farms totaling some 15,000 acres. By the mid-1990s they were buying about 20 farms a year. At the turn of the century, they owned some 1,400 farms—about 40 percent of the farms in Lancaster County.25

And so in an ironic twist of fate, the Amish who had entered business because of dwindling acres were now able to buy more land with their newly earned dollars. But twenty new farms a year were hardly enough to turn the tide with 170 couples pledging wedding vows each fall. Nevertheless, Amish purchases helped the countywide effort to preserve farm land. Public officials are quick to point out that the Amish are a powerful force for farmland preservation because they rarely sell their land for development.

For new sources of income, this farmer began building storage sheds and rented land for a cellular telephone tower.

Two agencies in Lancaster County actively seek to preserve farmland: the Agricultural Preserve Board, a government agency; and Lancaster Farmland Trust, a private agency. Reluctant to accept government funds, the Amish have been more willing to cooperate with the Trust because of its private status. The first Amish farm was preserved in 1990, and by 2000, the Trust held easements protecting forty-seven Amish farms. Although skittish about receiving $2,100 per acre in government funds from the Agriculture Preserve Board, three Amish farmers stepped across the line and preserved their farms in 2000. Others were reportedly filing applications with the Agricultural Preserve Board, signaling a new openness among a few Amish to accept government funds to save their land.26 Thus, on top of their rising fortunes in business, the Amish are also holding a growing portion of Lancaster County soil.

When asked what you cannot buy these days from an Amish shop, an old sage wryly remarked: “About the only thing we don’t have is an undertaker.” While not quite true, his quip symbolizes the mushrooming infrastructure of Amish-owned services. The Amish own shops that sell shoes, dry goods, furniture, hardware, and wholesale foods. Amishmen work as masons, plumbers, painters, and self-trained accountants. The explosion of nonagricultural jobs has ushered in a new era of Amish history. Instead of depending on outsiders for the bulk of their services, they have developed their own capacity to supply many of the services and products needed within their community.27 A streak of modernity lies beneath this ethnic umbrella, for some functions that were previously done at home are now performed by a specialist, albeit an Amish one. This extensive web of shops built on networks of social capital provides jobs and financial revenues, and also creates a buffer zone with the larger culture.

Amish enterprises vary in size, location, and function. The three major types are small cottage industries, larger manufacturing establishments, and mobile work crews. Home-based operations, often located on farms, are housed in tobacco sheds, retrofitted farm buildings, or new facilities. Bakeshops, craft shops, machine shops, cabinet shops, hardware stores, health food shops, and flower shops are a few of the hundreds that are adjacent or annexed to a barn or house. Many home-based retail shops cater to tourists, Amish, and non-Amish neighbors alike. These shops, like the old mom-and-pop grocery stores of bygone America, are largely family operations. A sampler of the shops appears in Table 10.3.

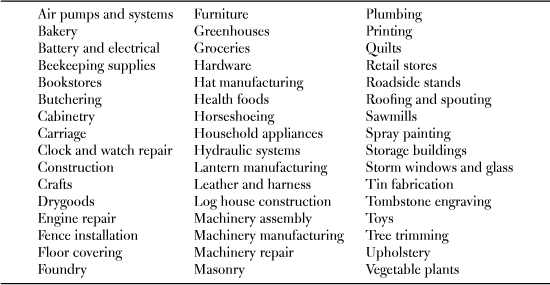

TABLE 10.3

A Sampler of Amish-operated Shops and Businesses

One young father, for example, operates a washing machine shop in an oversized garage on his farm. He buys used washing machines and replaces their electric motors with solid-state ignition gasoline engines from Japan. The refurbished washing machines are sold to Amish customers. A cabinet maker works with four of his sons making quality kitchen cabinets that are distributed out of the county. Several adults—an uncle, a cousin, or a sister—may assist the nuclear family as part- or full-time employees in the cottage industries. Children help or hinder the operation, as the case may be. These microenterprises, lodged at home, range in size from one to a half-dozen employees. One thing is certain: work in these settings is securely under the family’s control. “What we’re trying to do, really,” said one proprietor, “is keep the family together.”28

Larger shops or manufacturing concerns are established in newly erected buildings on the edge of a farm or on a plot with a house. Some manufacturing plants are beginning to locate in small industrial parks to avoid zoning hassles. This trend will likely lead work farther away from home. The sizeable shops, with a dozen or so employees, function as established entities in the larger business community. On the other hand, blacksmith shops and welding shops that manufacture horse-drawn equipment cater primarily to the Amish. But the bulk of the new businesses, such as cabinet shops and hydraulic shops, serve both Amish and non-Amish customers alike. Many retail outlets—hardware, paint, furniture, and food stores—also sell to both groups. Woodworking shops produce fine furniture as well as portable storage barns, doghouses, lawn furniture, and mailboxes, all of which are sold across the eastern seaboard to non-Amish customers. Some businesses sell their products to large national chains such as Wal-Mart and K-Mart.

An Amishwoman owns and operates this shop. She makes dried flower arrangements that are shipped out of state. A horse barn is on the left. Her adjacent home is not shown.

The larger manufacturing shops are efficient and modern. At first glance, hanging gas lanterns provide the only clue to their Amish ownership. Air and hydraulic power operate modern machinery. Diesel engines power the air and hydraulic pumps. Even burglar alarms are powered by air. One Amishman argued that air pressure is superior to electricity and that “some shops have electric systems beat hand over fist. That’s all there is to it. They even have their doors rigged up to an alarm. You know, if someone breaks in at night, they have air alarms all over the place that will blow a horn loud enough to scare a thief half to death.”

Mobile work crews are the third type of Amish enterprise. Amish construction crews travel to building sites in Lancaster County and other counties as well. Carpentry and construction work have always been acceptable alternatives to farming. Today, woodworking of one sort or another scores second only to farming as the most preferred occupation. Amish construction crews, using the latest power tools operated by portable electric generators or onsite electricity, engage in subcontract and general construction of both residential and commercial buildings. Trucks and vans provided by employees or regularly hired drivers transport Amish work crews on a daily basis. Amish cabinet shops produce high-quality furniture, which is distributed out of state.

As the Amish have struggled to keep their work at home and their families together, they have encountered another modern obstacle: zoning. Ironically, the zoning laws that once protected their farms from outside developers now prevent some of them from building shops on their own farms. The proliferation of cottage industries and small manufacturing operations, often built in agricultural zones, have caused some tension with public officials. In the 1980s and 1990s several townships negotiated with the Amish, hoping to adapt zoning codes that would control the size of on-farm businesses in rural areas. Under pressure from the Amish, one township amended its agricultural zoning ordinance to permit home industries that did not exceed 2,500 square feet or employ more than four workers, including the owner. Another township has a limit of two nonfamily employees.29 It was an interesting twist, because modern law and government were being used to enforce Amish values of small-scale operations and family involvement. Because of zoning restrictions and their booming size, some businesses are moving into industrial parks.

Hundreds of gazebos are made by this and other woodworking shops. They are shipped out of state by tractor trailer trucks. The panels near the roof lines help to illuminate the interior of the shop, which has no electric lights.

Amish industries bear the imprint of Amish culture in several ways. They are typically small. Although there is not an exact cap on size, it is rare for them to have more than fifteen employees. Church leaders caution owners about the dangers that accompany large-scale operations—pride, worldliness, excessive power, publicity, and status. Many Amish industries have annual sales exceeding $1 million; the largest ones likely reach $8–$12 million. Discreet expansion is more acceptable than a large complex of buildings, which gives the appearance of too much success. Installing cabinets or building silos around the county is less conspicuous and thus more palatable than operating a large manufacturing complex on one site with a hundred employees. Stories are told of Amish business owners who, refusing to bend to the limits of size, became proud and eventually left the church or were excommunicated. Describing one of these casualties, a businessman said: “You just have to be careful not to get proud wings and spread them like Ike Smoker did. That just won’t fit. You need to keep your humility and keep your head down under the covers.”

Even the largest businesses employ primarily fellow Amish. The non-Amish employees are frequently members of other Plain churches with similar cultural values. Sometimes outsiders are hired for the use of their vehicles or for particular technical skills. One businessman regretted hiring a non-Amish employee who created problems with his Amish employees, and since then he has hired within the fold.

Table 10.3 lists typical Amish businesses. Products ranging from mushrooms to plastic toys can be bought in Amish stores. Hundreds of Amish-made products—from finely sculptured cornhusk dolls to clumsy manure spreaders—are available for sale. In general, the products and services fit with Amish values. Selling and repairing radios, for instance, would be off limits, as would car, computer, or video sales. Selling new chain saws and barbecue grills is acceptable because these are used by the Amish themselves. Farm equipment is sometimes manufactured by Amish shops in two versions—a steel-wheeled edition for the Amish and a rubber-tired one for their neighbors. The taboo on electricity makes it difficult to sell refrigerated or frozen food products. Various trades, crafts, woodworking, construction, and manufacturing jobs as well as retailing provide the majority of nonfarm jobs. Few Amish work in service or information roles that require formal education and extensive interaction with the outside world.

An inventive streak runs through Amish culture. A tinkering attitude, the taboo on electricity, and a bent for self-sufficiency have stimulated dozens of inventions. For example, a manufacturer developed a hay turner that flips hay upside down and speeds its drying time in the field.30 Other inventions include a horse-drawn plow with a wheel-driven hydraulic pump that presses the blade into the soil; a frost-free outdoor watering trough for cattle that uses the earth’s natural heat to prevent freezing in the winter; a high-pressure sprayer to clean buildings; a golf course cupper to drill holes on the green; and a machine that wraps large hay bales in plastic. An Amish shop developed and manufactures its own 12-volt Pequea battery. The list goes on and on.

One thing is clear: the feeble repair shops of yesteryear have been superseded by manufacturing facilities that enable the Amish to manufacture most of their horse-drawn equipment and to supply other products to non-Amish around the world. One snag worries a leading manufacturer. He fears that newer manufacturing equipment, increasingly dependent on computerized controls, may be difficult to convert to air and hydraulic power and thus may limit Amish productivity.

The bishops, who had stubbornly insisted on horse-drawn equipment in the early 1960s, inadvertently seeded a host of new jobs in the Amish shops that build and refabricate farm machinery. In the same manner, Amish clothing, horse and buggy transportation, and the rejection of electricity have fostered innumerable jobs that serve the special needs of Amish society. These new jobs have diminished the lure of working in modern factories. The technological riddles that baffle outsiders not only defer to tradition but also create a panoply of jobs for Amish families. Although many nonfarm jobs produce products for the larger society, agricultural support and ethnic specialty jobs still undergird the economy of Amish society.

A remarkable thing had happened by the turn of the twenty-first century: barefoot Amish farmers had become successful businessmen. Even more astonishing, they had done it in one generation without the help of high school, let alone college, and without computers, electricity, or courses in accounting, marketing, and management. Moreover, their failure rate for new business starts was less than 5 percent compared to a national rate of 60 percent. How did these backwoods farmers manage to turn their plows into profits?

Within one generation Lancaster County had witnessed, in the words of one observer, “a mini-industrial revolution.” The Amish were no longer selling homemade root beer, brooms, and dolls in roadside stands. The fledgling shops of the 1970s had abruptly come of age. One Amishman compared the old with the new this way: “[The old cabinet makers] would start with a pile of 1 × 12 white pine boards, a small gas powered table saw, a box of cigars and lots of muscle. Nowadays over twenty large shops produce 800 storage sheds and thirty gazebos a week.”31 This yields some 40,000 items a year in only one of many product lines. About fifty Amish cabinet shops each produce fifteen to a hundred new kitchens every year. No longer restricted to the corner of an old tobacco shed, the larger businesses occupy 20,000- to 30,000-square-foot areas in spanking new facilities.

The number of establishments offers another measure of success. On average there are about twelve businesses in each church district, totaling some 1,600 enterprises across the settlement.32 Indeed, one in five adults (aged 25–65) owns a business. With more and more youth entering business, the number rises every year. In addition to their negligible failure rate, all signals suggest financial success. A bank official, knowledgeable of Amish finances, said, “The huge wealth created by Amish businesses in recent years is simply staggering.” A credit officer concurred: “The wealth generated in the Amish community in the last ten years is just fantastic, it’s phenomenal.” According to one financial observer, the top ten Amish businesses likely have annual sales of $8–$12 million and most of those net 10 percent, or about $1 million in profit.33 The bulk of Amish enterprises have lower annual sales, but gross receipts of a million are not unusual.

The credit record of the Amish in the local financial community is enviable. An attorney who works closely with them knows of no suits against them for bad debts. A credit officer who loans millions of dollars annually to the Amish has “never had to foreclose on a bad loan.” Another banker said, “I never lost a dime lending to the Amish” in over fifteen years with a loan portfolio averaging $30 million.

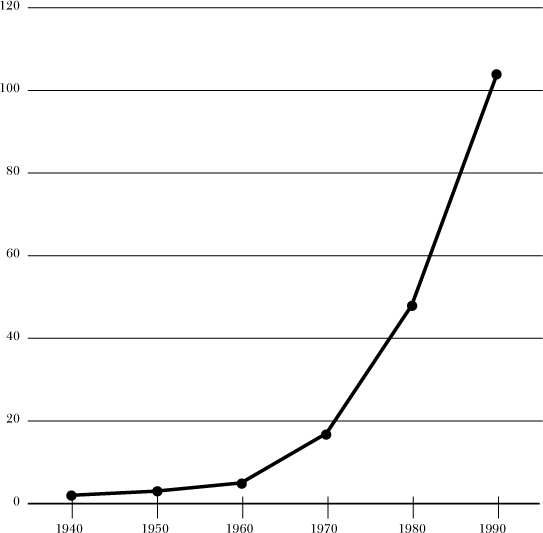

FIGURE 10.2 The Rise of Amish Businesses in Thirteen Church Districts, 1940–1990. Source: Amish Enterprise Profile (Appendix A).

What are the sources of the surprising success of these shops with humble beginnings that eschew electric power, computers, and trucks? The roots of success are both external and internal to Amish society.34 External factors include a strong regional economy, positive public perceptions of Amish products, a sizeable tourist market, and cooperative public officials, as well as payroll exemptions for Social Security and Worker’s Compensation.

Internal factors propelling the success include the pool of cultural and social capital in Amish society—a rural heritage of entrepreneurial values, a strong work ethic, religious values of austerity and simplicity, cultural taboos on education and certain forms of technology, family involvement, ethnic networks, small-scale operations, product uniqueness and quality, as well as an effective system of apprenticeship. All of these factors both within and beyond Amish society have bolstered their entrepreneurial success. Ample social capital was an important resource that enabled them to develop economic capital and achieve financial success.

The success has been aided by a supportive infrastructure both within and beyond the community. Within the community, a growing specialization of skills and shops provides the expertise to develop and operate sizeable enterprises. Numerous shops, for example, specialize in adapting modern equipment to hydraulic or air power. Beyond the local skill base, an infrastructure of external suppliers and dealers brings raw materials to Amish shops and distributes finished products across the country. Some of the national lumber companies send their best sales people and finest lumber to Amish country. Likewise a network of non-Amish dealers distribute products far and wide. An annual trade market brings hundreds of wholesale buyers from across the country to inspect hundreds of Amish products in one location. In reverse fashion, outside vendors bring samples of their latest equipment to the same site for Amish shop owners to inspect. The growing infrastructure has provided an important base for the booming growth of Amish business.

How will growing Amish businesses cope with the traditional limit on size and the restriction on using computers? One outside financial observer predicted that sizeable businesses may be sold off to outside buyers. Indeed, several large businesses have already been sold to outsiders. One successful owner reportedly sold his business for “millions” and bought a thousand acres of farmland in Indiana. He then sold some of the land back to other Amish families. In other cases, profits from selling off a business are invested in new enterprises within the community.

Two restraints imposed by Amish culture ironically play an important role as well. The taboo on higher education gives Amish men only two possible career tracks: farming or business. With professional careers off the screen, many of the brightest and best head into business. The would-be surgeons, lawyers, pilots, professors, and computer gurus end up creating their own businesses with enormous energy and ingenuity. Moreover, the Amish insistence on small-scale operations keeps businesses small and spreads entrepreneurship far and wide across the settlement. Instead of a few large factories, hundreds of people run businesses and enjoy the delights of entrepreneurship. And for those employees who are not at the throttle of the business, they are nevertheless close to the action and part of a small team effort. In different ways all of these factors have contributed to the profitability of Amish business.

The occupational transformation underway in the Lancaster settlement is the most profound and consequential change since the arrival of the Amish in North America. Its long-term consequences will fundamentally alter a way of life that for more than two and a half centuries has been anchored in a rural, separatist culture. One social scientist has called the small cottage industries—not to mention the larger ones—a Trojan horse in Amish society.35

Human groups are resilient and dynamic, making it impossible to predict the long-term impact of this occupation swing. The Amish in particular are adept at creating new symbolic boundaries to protect their identity. How they will fare over the generations and what form their identity will take in the coming years is unclear, but one thing is certain: the transformation of work will change every aspect of their life. It is one thing for first-generation farmers to start successful businesses and abide by traditional cultural values; but it is quite something else to pass separatist values over several generations of entrepreneurs.

In some ways, nonfarm jobs have enhanced the vitality of community life. For example, they have increased the Amish population density. Single-dwelling houses on small lots have greatly reduced the geographical size of some church districts, which enhances face-to-face interaction. This reinforces the oral base and social ties of Amish culture as well as the practicality of horse-and-buggy travel because family and friends are nearby. With fellow Amish closer together, the dialect constantly reaffirms the sectarian worldview and provides a buffer against modern ways. In these ways the occupational changes have embellished community solidarity, replenished social capital, and fortified Amish identity.

Moreover, small-scale businesses and family-operated industries provide flexible work schedules that accommodate the community’s predictable and unexpected needs. Requests to attend a half-dozen all-day weddings in November, welcomed with delight by an Amish proprietor, might annoy the human resource department of a mainstream corporation. Although they may seem numerous, the “community days” taken by Amish employees hardly exceed the sick days, personal days, and holiday time used by modern employees. Small Amish industries can more easily respond to community needs for volunteer help at frolics, barn raisings, or disasters than large corporate industries. Employees in Amish businesses forgo the perks of hospitalization and retirement benefits, which increases their dependence on the ethnic community.

In all of these ways, the new industries are truly Amish in character—designed to serve the needs of the community rather than those of the individual. And yet, paradoxically, the individual is also served rather well—with high levels of job satisfaction, a humane work environment, a high degree of control over production, and ethnic pride in the product. Alienation between employee and employer, typical of some contemporary work, is largely absent in the smaller shops.

Although the rise of Amish shops has stalled the lunchpail threat, the long-term consequences of this shift in the structure of Amish life are unknown. Small, home-based cottage industries promise few disruptions to traditional Amish values, even in the long run. However, the ramifications of the retailing and manufacturing businesses that exceed a half-dozen employees and boast multimillion-dollar sales are a different story. Amish leaders, including some proprietors, are uneasy about the debilitating social effects of these ventures. Dependence on daily wages and the press of production schedules in Amish factories may eventually create complications with community activities, even with sympathetic managers. An employee whose household budget depends on daily wages may find it difficult to forgo a whole day’s wage to attend a wedding or frolic. Even Amish businessmen, under the stress of tight production schedules, may become reluctant to release employees for barn raisings or family reunions.

Amish manufacturing establishments and construction firms follow typical business routines with fixed hours and policies. Traditional farm work often requires sixteen-hour workdays during planting and harvest. Church leaders worry that the spare time afforded by an eight-hour workday will lead employees, especially youth, into questionable recreation. A major Amish retailer voiced his anxiety: “The thing that scares me the most is the seven-to-five syndrome with evenings free. Our people, not just the young ones, have too much leisure time, and money in their pockets. In the past we were always more or less tied within a small radius of home because there were always chores. I even thought that Pop raised some weeds for us to pull.” Traditional Amish attitudes toward work and leisure will certainly change as the exodus from the farm continues.

Family size typically declines during industrialization because children, no longer needed for farm work, become an economic liability. A decline in family size would certainly temper Amish population growth. Although Amish families have shrunk a bit from their mid-twentieth-century size, they still average six or seven children. Children currently are involved in home-based industries, but all that could change over time.

Furthermore, even though young fathers are working within a mile of their families, they are nevertheless away from home. Despite a supportive ethnic system, some leaders worry that this will have a detrimental effect on child rearing. Children will no longer work with, or learn occupational skills from, their fathers; and mothers will carry a greater burden for child supervision. In a word, business involvements will surely change child-rearing practices.

Gender relations are under flux as well. As noted before, women own about 17 percent of the Amish businesses. In a patriarchal society this will induce some changes as women have more access to money, other resources, and the outside world. Women, in short, are gaining more power, and this will likely impact their broader influence within the community as well. Although some couples work together in their business ventures, many do not. In modern fashion, this eliminates the preindustrial type of partnerships that many Amish couples enjoyed on the farm. As more and more work leaves the home, work-based marital partnerships will dissolve. Women, for example, typically had joint legal ownership of farmland; but if a husband owns a business, his wife is rarely a joint owner.

The Pennsylvania German dialect will face greater contamination and decline as business involvements grow. Many business owners use English throughout the day as they interact with suppliers, consultants, sales people, dealers, and customers. More and more technical English words are seeping into the dialect. Children of business owners tend to learn English at an earlier age because of exposure to outsiders. Greater interaction with English speakers will obviously dilute the dialect over time and may shrink it to a sacred language, retained only for services on Sunday.

Sometimes called “The Wal-Mart” of Amish stores, this large retail store at three locations sells food in large sizes and damaged containers. Solar panels in the roof help to illuminate the interior.

The COME IN, WE’RE OPEN signs on doors of Amish stores, the growing advertising used by some enterprises, and the daily contact with customers signal an openness and involvement with the outside world that is unprecedented in Amish history. Indeed Olshan notes that it is hard to imagine a more graphic denial of the claim to separation than the come in, we’re open signs.36 Never before have the Amish interacted so freely and so willingly with the larger society. Moreover, the commercial involvements are creating an economic dependence on outside markets that challenge longstanding principles of separation from the world. Will it be possible in the long run to have growing economic integration and still retain a semblance of social separation?

The greater interaction with the outside world will bring greater temptations related to technology. The Amish have carefully screened technology for its debilitating effects on community, but easy interaction with the larger world will make it more tempting to accept communicative technology—telephone, radio, television. As global commerce becomes increasingly dependent on the Internet, the use of computers will be a growing temptation. All of these factors will stretch, if not snap, traditional “understandings” of the Ordnung.

The rapid migration into business is not only transforming Amish values, but it is also creating a three-tiered society. The Amish have never advocated communitarian equality, and as one Amishman noted, “There have always been a few wealthy Amish.” Nevertheless, the traditional farm economy placed everyone on equal social footing. All of that has changed. The ventures into commerce are producing a three-class society based on a triad of occupations: traditional farmers, business owners, and day laborers. The farmers have collateral wealth in their land but often meager cash in their hand. Farm families in general tend to be more conservative, reflecting the Plainer more traditional values. Day laborers in shops and farms have a steady cash flow but do not have significant wealth. Shop workers may earn $30,000 or more a year and enjoy a comfortable standard of living within the confines of Amish economy. The major business owners represent a new commercial class that heretofore has been unknown in Amish society. They bring the greatest challenge to traditional ways.

Despite an eighth-grade education, the members of the emerging commercial class are bright, astute managers. Some have taken special training in technical areas, such as hydraulics or fiberglass. Through self-motivation and experience, they have, within one generation, become proficient managers. Their stunning success in many ways validates the merits of their eighth-grade education. They understand the larger social system and interact easily with suppliers, business colleagues, customers, attorneys, and credit officers. They have learned basic management procedures and how to develop marketing strategies and calculate profit ratios. They walk a delicate tightrope between the boundaries of traditional Amish culture and the need to operate their business in a profitable manner. Reflecting on the electricity taboo, the young owner of a retail store said: “There is a whole new group of young shop owners who think some of the old traditional distinctions are foolish!” In the heat of a legal transaction, one business owner muttered to his attorney, “Business is business, and religion is religion,” signaling a breech between the historical integration of faith and work in Amish life. Such thinking among this managerial class may destabilize Amish life in several ways.

First, managers, immersed in the daily logic of the business world, may become disenchanted with traditional Amish values. Will they, for instance, be satisfied on Sunday mornings with the slow cadence of Amish hymns and pleas for humility when their daily work intersects with the aggressive cut-throat world of commerce? How long will they pay polite deference to Ordnung rulings that obstruct rational planning and profits? One successful Amish entrepreneur was described by a banker as having “nine toes in the world and one toe in the church.”

Second, this emergent class represents a new, informal power structure in Amish society. The financial achievements of this class earns it both respect and envy within Amish ranks. In some cases business owners have greater freedom to modernize their operations than farmers, because they are less constrained by longstanding rulings.37 The fact that many ministers and some bishops are now business owners provides both understanding and leniency with business issues. Business knowledge and organizational savvy arm this new breed of Amish with a power base that, if organized, could pose a serious threat to the bishops’ traditional clout.

Third, business owners often feel caught in the cross fire of traditional values and economic pressures. They know that aggressive promotion will enhance profits, yet church leaders criticize and even excommunicate them if they expand too fast. Commenting on a rapidly growing business, a cynical entrepreneur said, “Wait till they start making money, then the church will throw the Ordnung at them.” One owner, under fire from church leaders for his booming business, voiced his frustration at being torn between business opportunity and small-scale values: “My own people look at my growth as a sign of greed—that I’m not satisfied to limit my volume. The volume bothers them. The Old Order Amish are supposed to be a people who do not engage in big business, and I’m right on the borderline right now. I’m a little over the line and maybe too large for Amish standards. My people think evil of me for being such a large businessman and I don’t need any more aggravation right now.” However, struggling with the delicate tensions, he continued: “Identity, having a people, is a very precious thing.”

Business owners also find themselves in fiscal quandaries that force them to use the law to protect their own interests—a traditional taboo in Amish culture. The Amish use lawyers to draw up farm deeds, wills, and articles of incorporation and to transfer real estate. However, filing lawsuits is cause for excommunication. Following the suffering Jesus, in the spirit of nonresistance, the Amish traditionally have suffered injustice rather than resort to legal force.

Such humility defies normal business practice and makes Amish owners vulnerable to exploitation. “You know,” said a businessman, “we are in a bind, being in business. When you deal with the business community you are at a distinct disadvantage, because there are those who would take advantage of you.” Already the victims of shrewd debtors, entrepreneurs are asking their attorneys to write threatening letters and using legal means to recover unpaid debts, but they usually stop short of filing lawsuits. One Amishman, bilked by an out-of-state dealer for several gazebos, sent one of his drivers to pick them up under the cover of darkness and bring them home. Whether business owners will be able to retain nonresistant values in the midst of cutthroat competition is unknown.

Fourth, many of the new commercial class are doing well financially. “The old graybeards have no idea how much money is flowing around in this community,” one banker noted. The more successful entrepreneurs earn several hundred thousand dollars a year.38 One business owner paid $117,000 on personal taxes alone. In another example, a furniture shop owner earned $340,000 in profit in one year. Some construction foremen may make $65,000 a year, while their Amish boss makes upwards of $200,000. Meanwhile, however, many farmers and shop workers are only earning $35,000. Given modest Amish standards of living, such income levels generate considerable wealth.

Where does all the money go? Mostly into real estate, business expansion, community needs, loans within the community, mutual funds, and savings accounts.39 Some of the newly rich are building expensive homes by Amish standards that cost upwards of $250,000. Historically the Amish have not invested in individual stocks, but in recent years hundreds of them have invested in mutual funds. One mutual fund manager noted that some of the “bigger business owners leave mutual funds because they want to be more aggressive with their investments. They are greedy and so they go to stockbrokers.” However, not everyone is greedy. An employee of a very profitable Amish business said his boss would not build a new expensive house, “because he thinks it’s not right with so many poor people in the world.” However, the swelling wealth in a small circle may erode social equality over time.

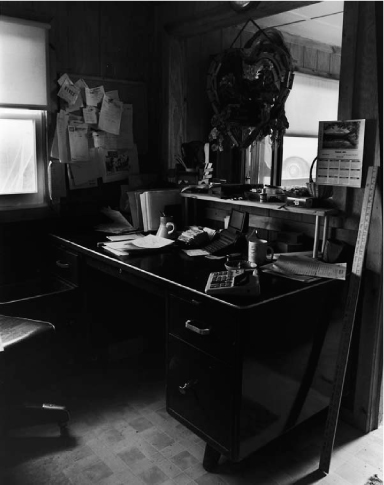

The office of a sizeable business. The word processor, calculator, and Rolodex symbolize the rational worldview of successful entrepreneurs.

Will Amish millionaires be content to drive horses and dress in Plain clothing over several generations? Inexperienced in coping with the inequalities of wealth, the church is uncertain how to respond to the new commercial class. In the past, modest profits from farming were reinvested in farming operations and used to help children establish their own farms. Revenues from Amish businesses were typically invested in real estate, used to buy new farms, or contributed to needs within the ethnic community, rather than invested in the stock market or devoured by conspicuous consumption. An Amishman in another settlement describes the Lancaster Amish as being “almost hyper about making money . . . some businesses are very successful and handling a lot of cash and are rich period. This affects the types of houses they build for themselves and for their children, where they travel, where they eat, and what they own.”

Using outside standards of success, Amish businesses appear to be doing quite well. But success is not a favorite word among the Amish. Indeed, some elders worry that the pursuit of profit may be an ugly worm inside the rosy apple of Amish success. Bishops and businessmen alike fear that in the long run prosperity could ruin the church. Some church leaders believe prosperity is as dangerous as persecution. “Pride and prosperity,” said one elder, “could do us in.” Will the church be able to motivate the wealthy commercial class to use their resources for community enhancement rather than for self-indulgence?

The occupational bargain that the Amish struck in the 1980s when they left their plows for cottage industries has served them well for a generation. It kept their work within their control and allowed it to flourish in the context of family and community. However, it remains uncertain whether this was a good compromise or a worm that will eat their soul from within over time. Will the transformation of work undermine community stability and erode Amish identity? Furthermore, many of the regulatory concessions that the modern world has made for the Amish—for instance, in schooling and Social Security—were based on the premise that they were self-employed farmers. As they become successful entrepreneurs, legislative tolerance and leniency may also wane.