The Evolving Roles of the Private Collector

WHAT HAS CHANGED?

Influential private collectors tend to be very wealthy. Many of them became wealthy by being very good at what they do. Captains of industry or simply very smart business people, they often compete, and clearly succeed, in cutthroat business arenas day in and day out. Many of them have traditionally invested in collecting art as a way to step outside of the daily pressures of their professional ambitions. I have frequently been told by collectors that visiting galleries and discussing art was an opportunity for them to slow down and think about something other than spreadsheets or corporate takeovers. Collecting was how they relaxed. Between 2008 and 2015, though, the relaxing atmosphere of collecting contemporary art began to change on many fronts. I am sure it remains more relaxing than many of the wealthy collectors’ day jobs, but I would argue that during this time there was a sea change in the culture of collecting contemporary art. This change emerged due to several factors, including increased access to information online; increased competition for bankable artists’ work; the “corporatization” of the contemporary art scene; the way art fairs accelerated the pace of collecting; and how much more money in the system grabbed the attention of new entrepreneurs hoping to get some of it.

To understand the specifics of this cultural change and how it affected the collector-dealer relationship, it perhaps makes sense first to discuss the role of private collectors within the overall context of the contemporary art world, and their relationships (or lack thereof) to the other players in that system whom dealers interact with and often need to accommodate. We often think of dealers as needing to please two sets of “clients”—artists and collectors—and that balancing those two sets of clients’ often mutually exclusive interests is one of the profession’s toughest challenges. In fact, dealers are attempting to please a wide range of other players, including curators, critics, museum directors, consultants, executors of estates, foundation directors, art fair selection committee members, and even the general public. To understand the evolving roles of the private collector fully, it makes sense to examine the changing relationship between collectors and some of these other players. Below we will examine how private collectors’ interactions with museums, art criticism, other collectors, and dealers have changed over the past several years. Throughout, we will also touch on how these changes have caused, or been brought about by, evolutions in the art market. Finally, we will discuss strategies for managing the impact these changes are having on dealers’ relationships with collectors.

Museums

Historically, the active role of private collectors within the contemporary art scene, beyond being merely buyers, has often been that of patron, most publicly identifiable as such by serving as trustees for museums and nonprofit institutions, where they are asked to provide guidance in how to meet the organization’s mission; to help with fund-raising (either by encouraging others to donate money or by doing so themselves); and possibly to gift prized pieces from their collections to the institution. How well informed a private collector was about contemporary art or their personal capacity for connoisseurship may have made them a more effective patron, and how influential their collection was may have made them a taste-maker within certain spheres, but generally the conventional wisdom was that directors and especially curators were the “authorities” on the newest art coming out of living artists’ studios, and that trustees looked to them for guidance on it, which often subsequently influenced their private purchase decisions. While it may be difficult to separate the sour-grapes-style feedback from more meaningful observations, between 2008 and 2015 insiders increasingly noted (one might say “complained about”) how many collectors, even brand-new ones, no longer felt the need to seek out such guidance.

Beyond just making their own purchasing decisions, however, private collectors also increasingly began openly to exert authority throughout the entire museum system in unprecedented and sometimes controversial ways. Most alarming perhaps, some would argue, was how this exerted authority contributed directly to a more blatant blurring of the line between the commercial and noncommercial sectors of the contemporary art world. A good example of such alarm over this blurring was “Skin Fruit,” the 2010 exhibition at New York’s New Museum of artworks from the private collection of Dakis Joannou, a Greek collector who was not only a trustee of the museum, but who had the artist Jeff Koons (who is a close friend of his and whose work is well represented in the collection) serve as the exhibition’s curator.

New Museum director Lisa Phillips dismissed the objections over this planned exhibition, which began long before it opened, by saying “We’re not the first to do an exhibition of a private collection, and we won’t be the last.”1 But in covering the controversy, the New York Times noted how this exhibition was pushing the boundaries of what was considered the acceptable risks of “renting out the reputation” of the museum. More specifically, in the Times article, Erik Ledbetter, director of international programs and ethics at the American Association of Museums, discussed his association’s guidelines for borrowing and exhibiting artwork from a collector, and “Skin Fruit” appeared to violate them significantly:

The guidelines stress the potential for conflicts if board members become lenders, Mr. Ledbetter said. He offered these “cautionary flags”: a show devoted to one collector; a show in which the collector is a board member, donor or underwriter; a show in which the museum gives away or pools curatorial judgment with the collector.

“Any one of those things can be managed,” he said, “but when you layer them on top of each other, it’s more complicated.”

The New Museum show raises all the association’s cautionary flags except one: Mr. Joannou is not underwriting the exhibition.1

The outcry over this exhibition was considerable. Journalist Tyler Green was among the exhibition’s most indomitable critics, writing that it was turning one of New York’s most respected and traditionally experimental museums into “the trading floor’s go-to place for shopping list validation.”2 Artist William Powhida’s satirical drawing on the exhibition, “How the New Museum Committed Suicide with Banality,” made the cover of the arts publication The Brooklyn Rail and helped raise the controversy to nearly epic status in New York’s museum history. His drawing, which featured cartoon heads of the various players involved in the controversy, included a caricature of Joannou saying, “The Miami model? Why build my own space in New York when I have already funded the New Museum. You’re funny” (www.williampowhida.com). By “the Miami model,” Powhida was referring to private collections in the Florida city that have been opened up to the public, such as those owned by the Rubell family, the De la Cruz family, and the Margulies family. (That model is frequently held up as an example of patronage par excellence in the contemporary art world.)

In Powhida’s drawing, unlike the imagined quote from Jannou, the speech bubble by Lisa Phillips’s caricature contains something she actually said in an interview with Tyler Green before the exhibition opened:

I’ve talked to a number of collectors and that’s the primary appeal of working with a museum, that there would be research and scholarship that would be done on their collections. . . . I guess I just have to repeat myself and say a redefinition of public-private partnerships has to be explored. Museums often can’t compete in the marketplace very effectively and there are tremendous expenses. . . . 3

Phillips seemed a bit exasperated about having to defend the museum’s decision in that second part, but her explanation is actually at the heart of this sense that collectors no longer play by the old patronage rules and that the new ways of thinking about the “public-private partnership” must be explored for museums to continue to fulfill their missions. The other pertinent part of her quote here is how museums “can’t compete in the marketplace,” an acknowledgement that many contemporary art museums are priced out of acquiring the contemporary art they might have purchased or commissioned before the market got so hot and collectors snapped it up so quickly. It is only by showing the work already in private collections that they can contextualize it for the public the way they exist to do. That does not entirely answer why the work in the exhibition had to come from only one private collection, but it does seem to be a key part of this shifting reality.

The strong reaction against the New Museum show also included resentment about the message it was sending about the role, or authority, of the museum curator of contemporary art. As Ledbetter had noted, giving away or pooling curatorial judgment with the collector (or his selected proxy) is a cautionary flag that there might be a conflict. More than just that, though, the New Museum has some of the best curatorial minds in all of New York. Why an outsider, and an artist with much more limited experience curating, would be considered a better choice to work on the “research and scholarship” aspect of presenting this collection ruffled many a feather and ultimately left many unimpressed. New York Times art critic Roberta Smith called it “blatantly unmagical curatorial thinking,”4 and New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz wrote, “What especially irks me is that the curating tells us more about Koons than it does about contemporary art, and he says it better in his own work.”5

As far back as 2008, rumblings about a rising “interference” by museum trustees were making the news. Former editor and publisher of ArtNEWS magazine Milton Esterow published a long list of complaints that museum directors were anonymously sharing with him about trustees pushing museums to “adopt a more corporate mindset.” Indeed, the way business norms were increasingly influencing museum choices was high on their list. In effect, the formerly genteel world many collectors were used to escaping to through their interest in art was giving way as a new type of collector entered this realm:

The arrival of hedge fund managers on boards has not always been welcomed. “They say there has to be a reciprocity of benefits,” said a museum director. “If they’re giving money and time, they think they deserve something. It might be advice on the art market or advance word on exhibitions where artists’ reputations are catapulted. It’s a climate that borders on self-dealing in a way Wall Street insiders would understand. It’s a subtle minuet played out with squeezes around the arm rather than around the throat.”6

Esterow also provided a list of “strings” that museums directors said were being increasingly attached to the financial aid or time their trustees were traditionally expected to provide freely in their role as patrons. The list included:

• “I’ll give this if you do this.”

• “Looking over the director’s shoulder.”

• “They interfere with everything from how work is installed to marketing.”

• “They try to get curatorial control.”

• “Making decisions over exhibitions.”

• “Wanting to come to staff meetings.”

• “Allowing an artist’s dealer to pay for part of a museum exhibition, which can—but not always—be a conflict of interest.”

• “Insisting that the donated works have to be all together.”

• “Pressure to exhibit artists whose works they collect.”6

Private conversations I have had with museum curators confirm that they feel tremendous pressure to act on trustees’ opinions, even when they disagree strongly with them, in much of the work they do. Nearly all of them will share anecdotes of certain trustees whose confidence in their opinions far outweighed their knowledge of contemporary art as well. Again, some of this may be sour grapes or simply the venting anyone in a stressful job needs to do from time to time. The ArtNEWS piece ends on a note similar to Lisa Phillips’s acknowledgement that museums simply need to adapt to this new financial and patronage reality. In his article, Esterow quoted Peter Marzio, the long-standing and respected director of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts (until his death in 2010), who seemed to embrace such developments in his relationships with collectors with a spirit of appreciation and good cheer, or at least a grain of salt:

There isn’t a major museum that wasn’t built by collectors. If you’re fortunate, they are your trustees. They have a point of view and it may not agree with yours, and that’s what’s fun. As to complaints, all of that may be true in individual cases. But this is the real world. What makes a great director, compared to an also-ran, is how you balance all those interests.6

More succinctly perhaps, museums who want private collectors’ support must adapt to what this generation of private collectors wants in return. Seemingly gone are the days that collector-trustees were happy to play a more passive role in the curatorial aspects of “guiding” the museum to success. A confidence in their opinions, often over that of the museums’ trained curators, has created tensions in the museums as they resolve this new dynamic. Dealers (who, again, need to please both curators and collectors) may lose favor by choosing sides in this turf battle, so it is perhaps best to stay on the sidelines.

Art Criticism

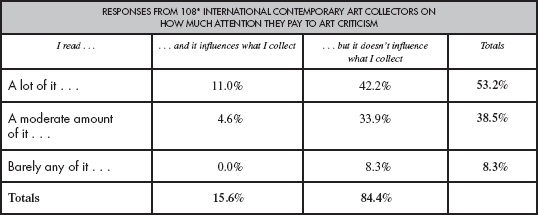

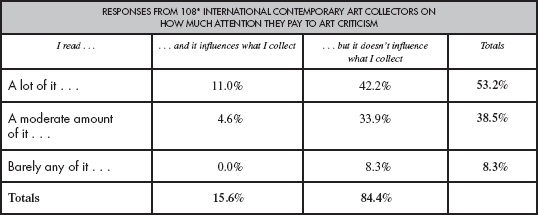

In a 2014 survey for this book that I posted online, 108 international self-declared “contemporary art collectors” answered the question “How much attention do you pay to art criticism (in newspapers, magazines, or online)?” as follows:

*Admittedly a small sample size, but via behind-the-scenes emails I know a fair number of them were among the top 200 collectors in the world or very active collectors.

The good news for art critics seems to be that a majority of these collectors read “a lot” or “a moderate amount” of art criticism. The bad news, perhaps, seems to be that it influences what they collect very little. This corresponds with what New York collectors Joel and Zoë Dictrow (who were ranked in the top 200 collectors in the world by Artnet News magazine in 2015 and who have been actively visiting galleries and buying contemporary art around the world for over 30 years) said in an interview for this book:

We are always interested in the opinions of critics, collectors, and certain dealers that we respect. Most criticism is not very interesting to us. Some of it is too academic for us, especially in art magazines. We listen but don’t rely on the opinions of others for acquiring emerging art. Our own eyes, hearts, and minds are our guide.

Similarly, the New York collector Glenn Fuhrman (who, with his wife Amanda, is among the top 200 collectors), confirmed this position in a separate interview for this book, while shedding additional light on the issue described above about museum curators:

Honestly, I’ve never really paid a lot of attention to art criticism. I don’t mean it from a perspective of hubris or arrogance, it’s more just that I’ve always relied on my own eye and my own heart and things that move me or I really like. Ultimately, we are buying things we love and want to live with. My personal experience has been, with no disrespect to professionals in this space, that critics and curators as well sometimes come around later, especially when it comes to contemporary art , and the few times I’ve heard curators talk about very contemporary art, it hasn’t necessarily been a compelling argument or one that resonated with me. Thankfully, I’ve never really relied on it.

This lack of interest in art criticism in the survey confuses me a bit, actually. It used to be that after our gallery received a positive review in the New York Times or a similarly prestigious publication, we would see an influx of collectors, new to us but often well informed with deep collections, come into the gallery carrying a clipping of the review or call to inquire about this work they had read was worth seeing. It also used to be that we could count on a nice uptick in sales after such reviews for most exhibitions. Between 2008 and 2015, though, that kind of commercial boost from art criticism definitely became much less reliable in my experience.

Indeed, in an interview about why he chose to switch his respected Brooklyn-based commercial art gallery, Interstate Projects, to a not-for-profit space, executive director Tom Weinrich cited this shift as part of his rationale:

As for the critical attention his gallery’s exhibitions have garnered, Weinrich stated that the relationship between praise and sales is “completely disconnected at this point.” He added: “I don’t know how that happened or when that happened, but it feels like that has happened recently. A New York Times review or an Artforum review doesn’t necessarily portend selling any work, the selling of the work just seems like it comes from back channels in a weird way, that’s the way it’s gone.”7

Of course, many art critics would argue that this is irrelevant to what they do. Theirs is not a profession involved in increasing the sales of the art they review. However, theirs is a profession involved in providing insights into the value of art, and the less attention the only people who can afford to buy the art that will eventually be gifted to the museums pay to their opinions, the less influence they exert in ensuring that the value of the legacy this generation collectively chooses to preserve is as high as it can be. Indeed, despite it obviously being something they would rather not discuss, most of the top art critics cannot help but get dragged into the inescapable art story of this era: the historically booming contemporary art market. In a 2014 article in the Washington Post about yet another record auction, Philip Kennicott wrote:

And the critics, once again, bristled at writing yet another story about yet another epic sale. Jed Perl of the New Republic wrote: “At Christie’s and Sotheby’s some of the wealthiest members of society, the people who can’t believe in anything until it’s been monetized, are trashing one of our last hopes for transcendence.” Peter Schjeldahl of the New Yorker said that for a critic to argue about the insane prices being paid today for art would be to “don a clown costume and to join the circus,” but he put on the costume long enough to note that, “the present art market plainly won’t quit until it hits the end of the line,” which he defined as “psychosis” and “ruinous passion.”8

It is clear they care about the market, if only in how it is drowning out their efforts to sway public opinion about particular artworks’ value.

Dealers used to view a positive review for their exhibitions as a win-win. It made the artist happy, and it often brought new collectors into the gallery. Toward that end, younger dealers in particular would court the favor of art critics any way they could. Reviews were selling tools for one set of clients, and prizes you helped secure for another set of clients, rolled up in one. If art criticism now only pleases or influences one set of clients, though, how much of a dealer’s increasingly limited time and effort does it make sense to devote to soliciting critics’ attention? That may depend primarily on how important reviews are to your artists or the role you feel they play in validating the historical importance of what you are doing in your gallery.

Other Collectors

During these years, well-established collectors also began sounding off about how the previous order of things in the contemporary art world was being upset by brash behaviors among new private collectors. In mid-2011, New York- and Miami-based collector Mickey Cartin raised a good number of eyebrows by writing an op-ed for Artnet magazine that blamed an “indiscriminate demand for production” for a dispiriting increase in the “mediocre material” in the Chelsea galleries he visited. He even drew a distinction between “collectors” and “consumers” of contemporary art:

For some reason, there are many wealthy people who are driven to pay very large sums of money for things that are of so little value. If it is not so apparent in the galleries, just go to an art auction and watch how consumers behave. . . . The consumer does not realize that the true value of a work of art has nothing to do with its price. They do not understand that art is valuable because it challenges, inspires, and enables us to see ourselves in much more interesting ways. I am one of those ideologues who believe without hesitation, but not blindly, that art makes the world a much more fascinating place. Consumers could care less.9

Near the end of 2011, British super-collector Charles Saatchi penned a scathing diatribe for the UK’s Guardian newspaper titled “The Hideousness of the Art World” in which he railed against the “Eurotrashy, Hedge-fundy, Hamptonites; . . . trendy oligarchs and oiligarchs; and . . . art dealers with masturbatory levels of self-regard” who were ruining the joy of collecting contemporary art for everyone else:

Do any of these people actually enjoy looking at art? Or do they simply enjoy having easily recognised, big-brand name pictures, bought ostentatiously in auction rooms at eye-catching prices, to decorate their several homes, floating and otherwise, in an instant demonstration of drop-dead coolth and wealth. Their pleasure is to be found in having their lovely friends measuring the weight of their baubles, and being awestruck.10

And New York collector Adam Lindmann, who by 2012 had opened his own gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, had seen enough from the both sides of the art market by early 2015 to note in a New York Observer column that

What’s missing today is connoisseurship, and original thinking. People can’t be bothered. They don’t have time for it or they simply don’t care. No one has patience for listening and learning; high stakes art selling relies on creating the feeding frenzy that triggers an irrational impulse buy. The market is fueled by pure hustle; the most successful dealers are the ones who are best at selling the sizzle, because no one gives a damn about the steak.11

In the cases of Saatchi and Lindmann, plenty of people behind the scenes (and a few openly) criticized them for throwing stones in glass houses. Saatchi had been criticized in an article in the same newspaper five years earlier, during the previous boom, for a track record of “buy[ing] up an artist’s works wholesale and then dump[ing] them, thereby ruining a career.”12 Similarly Lindmann was roasted in the press back in 2011 (before he opened his gallery) for announcing in a New York Observer column that he was boycotting Art Basel in Miami Beach that year to avoid being “seen rubbing elbows with all those phonies and scenesters, people who don’t even pretend they are remotely interested in art?”13 (only to later be spotted at that very fair). One of the most critical—some said overly personal—responses to Lindmann’s column came from New York magazine art critic Jerry Saltz:

His column is larded with that us-and-them attitude. He keeps mentioning the parties he’s been invited to but won’t be attending (“What’s the fun of being invited to so many things?” he sighs). He then pines for the days when “comparing values and tastes was made easy [for collectors] since you could value-shop different galleries and end up comparing a million-dollar Neo Rauch in one booth with a million-dollar Mark Tansey in another.” Finally, here, he’s tipped his hand, absolutely equating art with capital rather than with deep looking. 14

All in all, the tone of the collecting world has clearly changed. What had been a refined refuge from the daily pressures of their professions has evolved for many into an equally stressful combat zone. The artificially frenzied context of the art fairs has most likely been a leading factor in this, as has the heightened awareness everyone has of what everyone else is doing that the Internet has fostered. While one obvious antidote here would be a widespread return to the practice of collecting art primarily by visiting galleries, as we’ll see below, that will not be an easy modification to the way things are heading.

Dealers

Meeting and establishing a strong personal relationship with important collectors is the quintessential metric of success for so many of the activities that dealers spend a great deal of time and money on, from pricey networking opportunities to expensive promotions like art fairs. Getting important collectors to know and trust you is a long-term strategic advantage over other dealers. Of course, establishing a personal relationship and conveying your own value as a dealer is often much easier face to face, and particularly on your own turf, where you can direct the conversation toward the art on your gallery walls or in your inventory, where you can control the environment in which the art is viewed, or where you can simply relax and be yourself. Encouraging important collectors to actually visit their gallery, therefore, is an important goal for nearly any art dealer. Sure, each time one walks through the door represents another opportunity to make a sale, but the farsighted dealer also sees it as a good opportunity simply to strengthen their relationship.

In that same vein, ambitious collectors have long understood that it was in their best interest to develop close relationships with the most powerful art dealers, who decide which collectors hear first about available artworks on many collectors’ wish lists. Because at least a few of the younger dealers opening spaces will grow into the most powerful dealers of their generation, many top collectors have often cast a net as wide as they can in this endeavor. As one collector I know put it, he realized early on that to build the collection he wanted he needed to become a “collector of art dealers.” Indeed, exclusive control over information that could be found nowhere else has not only customarily made art dealers lots and lots of friends—at the higher levels of the art market it has given some the kind of social power that heads of state would be jealous of:

Private dealer Richard Polsky says that in many cases, when collectors buy from Mr. [Larry] Gagosian, what they’re really buying is Mr. Gagosian’s cachet: “You cannot underestimate the egos of the people who buy from Gagosian. Most would rather overpay to be part of his world, and he counts on that mystique to draw clients to him.”15

Back down on earth, though, many dealers who have closed their galleries since the recession have cited “a lack of foot traffic” as one of their main reasons (just Google “foot traffic in art galleries” and you’ll see the numbers are roughly eight to one in favor of reports of too little over a sufficient amount of foot traffic).

I tend to think this is a much more complex complaint for dealers than it would be for storefronts where any visitor might be expected to make a purchase. Indeed, by “foot traffic” dealers mostly mean informed visitors, existing collectors, or visitors open to becoming collectors. A reality in the major art centers, where new galleries open up all the time, is that the longer a gallery has been around, a decrease in foot traffic is likely very normal, unless they break into that “must see” category or consistently get great press. Short of that, hope for an increase or even a steady flow in foot traffic likely depends on locational factors, like other galleries opening nearby, or tourists who may or may not be informed in the way that would realistically result in sales. Much of the informed traffic a gallery will get when it first opens comes from those curious to learn about the new space and its program. As no program can be all things to all people, many originally curious visitors will decide that this or that gallery is simply not for them and hence not return frequently. To put it even more bluntly, the collective art world often concludes that they can live without visiting certain galleries on a regular basis, either because they have not liked what they have seen there or the gallery has not achieved the prestige that other galleries have. Galleries tend to retain a devoted core audience and, again, reach beyond it only via great reviews or other locational factors. As noted above, though, even great press seems to have a decreasing impact on sales.

Furthermore, much of the foot traffic most commercial art galleries have always had (and the form that continues more than the form lamented) comes from visitors who cannot afford or who have no intention of buying the art on view. They are there to view the art. Therefore, an increase in foot traffic, per se, is not actually what would save a gallery from closing. Although there are “encouragement” aspects to steady streams of visitors (that is, good attendance can enliven the mood in a gallery and make the odd collector who does come by feel that much more impressed or engaged), when most dealers think of “foot traffic,” they are thinking primarily of people who might actually purchase something, specifically buyers who are perhaps new to them and will hopefully become long-term clients.

How much busier everyone seems to be today is one explanation you will hear for decreased foot traffic of this form in galleries. My sense of it, though, is that it is more the result of two other developments. First is the historic number of galleries that exist, not only therefore dispersing the die-hards who pride themselves on keeping up with the contemporary art gallery scene, but possibly discouraging those in many arts centers, who feel overwhelmed by the swelling volume of spaces, from subjecting themselves to a seemingly endless task. More than all of these, though, it is the Internet and social media in particular.

During a panel discussion16 at the Art Los Angeles Contemporary fair in 2015 with Jonathan T. D. Neil, director of the Sotheby’s Institute of Art, Los Angeles, the sometimes polarizing art collector/dealer Stefan Simchowitz compared collectors’ increased direct access to information about artists’ work through social media to the central theory behind Martin Luther’s reformation of the Christian religion (which, you will note, did not spell the end of the Roman Catholic Church, even as it significantly cut into its adherents). In response to Neil suggesting that “someone has to adjudicate the [online] opinions . . . someone has to sift through them and decide that some are worth paying attention to and others aren’t worth paying attention to,” Simchowitz said:

The audience adjudicates . . . it’s a form of cultural Lutherism. Martin Luther basically comes out. He says you can have a one-to-one relationship with God. I can sit in the field and pray. I don’t need to walk into the cathedral that they spent a million dollars on to build and make a tithe to the priest, the bishop, or the cardinal. I can go to the field. I can get a cup of coffee, and I can be with God. . . . That’s what’s happening with social media.

Again, Simchowitz has voiced some very polarizing opinions about the contemporary art market, but on this point I suspect he is at least partially correct. What dealers have relied on to sell art for hundreds of years is the perception that they are an “authority” on what is important, on what collectors would be prudent to buy now or not buy at all. They controlled exclusive access to the information collectors could not find elsewhere. Dealers have been, in Simchowitz’s terms, the priest or the cardinal in their cathedrals, and only through them could collectors get the information or art they sought. Collectors often still need to curry favor with dealers to gain access to works by highly sought-after artists, of course, but among the factors slowly pulling apart that monopoly, none has accelerated change like Instagram and other social media, progressively putting artists in direct contact with new collectors, thereby giving both of them leverage in their relationship with dealers; or, as some people are speculating, accelerating their facility to forgo any relationship with dealers. There are several reasons that does not seem imminent at all, but that does not mean dealers can take those relationships for granted.

Other Factors

There are several other factors bringing about changes in the dealer-collector relationship I should mention again in this context. In Chapter 3 we discussed how a shift in collector loyalties from galleries to art fairs has made those expensive promotional events less useful in cementing close relationships with collectors. The globalization of the art market discussed in Chapter 1 has increased how far away your best new collectors may live, thereby increasing your costs in going to visit them, something often essential in staying close with them. As we saw in Chapter 2, the consolidation of art market power by a handful of mega-galleries, as well as the consolidation of top artists under fewer and fewer rosters, has contributed to a growing sense that “collecting dealers” need not include as wide an array of them as it previously might have. Combined with how collectors’ roles and interactions with the wider spectrum of art world players are evolving, these factors all contribute to my sense that dealers might want to explore new strategies for developing or maintaining strong relationships with collectors.

STRATEGIES FOR NAVIGATING THIS CHANGE

Dealers socialize with collectors in a variety of contemporary art world settings including, but by no means limited to, the arenas of the art market. Understanding how collectors’ roles across the contemporary art world have evolved can help dealers avoid landmines and perhaps adapt their relationships with collectors to these changes. Below we will look at strategies for thinking about this from two vantage points: (1) influencing without authority and (2) presenting the gallerist value proposition more compellingly.

Influencing without Authority

In highly structured corporations, many mid-level managers can simply dictate to the people who report to them what they want them to do. To become really successful and climb the company ladder, though, they must develop persuasive skills and other strategies for eliciting buy-in from colleagues who do not report to them. This set of skills and strategies is typically called “influencing without authority.” In the context of the evolving dealer-collector relationship, the concepts behind some of these same strategies may help dealers influence collectors, who may see a host of reasons to buy art outside the gallery system or who are less and less compelled by the “authority” argument to develop close relationships with dealers, to reconsider those decisions. Again, a strong personal relationship with collectors is a proven strategic advantage over other dealers.

You can find countless approaches to influencing without authority in the business press, but most of them concentrate on how best to structure your PowerPoint presentation or better understand why people are resistant to change, concepts not particularly useful here. The perspective I have found that strikes me as best suited to the contemporary art dealer’s current circumstance is that of Jo Miller, CEO of Women’s Leadership Coaching, Inc., who focuses instead on the main sources of influence in any context and explains how these are best used, or dismissed, when no recognized authority is backing you up. In her essay “Influencing Without Authority—Using Your Six Sources of Influence,”17 Miller examines the following sources, which we will briefly discuss in the art market context below:

1. Positional influence

2. Expertise influence

3. Resources influence

4. Informational influence

5. Direct influence

6. Relationships influence

Positional influence is what the mid-level manager has over the people who report to him; it comes with the job title. Miller calls this source of influence “over-rated” because people waste years waiting to have it officially bestowed on them, “when they could be influencing in other, more immediate ways.” Waiting is the deadly decision here. In Chapter 2 on mega-galleries, there is a discussion on “seizing the microphone,” which essentially asserts that you do not need to wait to be crowned as an industry leader to speak up and share your ideas. As someone who has now received many formal invitations to share my ideas, all traceable back to someone finding my blog in a search result, I can attest that had I waited for someone to bestow the authority to speak up on me, I would still be waiting. (I will note that I have met great collectors through my blog as well.) This is not to advise any other dealer to launch a competing blog, mind you, as much as to second Miller’s point that a lack of positional influence should not stop you from asserting the value of your ideas, your program, or your value as a market intermediary in as public and far-reaching a forum as possible.

Miller describes expertise influence as the kind that “comes with your background, experience, qualifications and career accomplishments.” She notes that the ultimate power from this source comes not merely from having it, but from people knowing that you have it. Most dealers are good at advertising their professional associations or highlighting good press for their gallery on their websites or social media, but surprisingly few include their personal bios on their websites. You know who does, though? Look in the bottom of any page on gagosian.com and you will see a link titled “About Larry Gagosian,” which is completely separate from the link “About the Gallery.” The bio you will find following that link includes a very nice, large photo (so you won’t mistake anyone else in the gallery for the owner) and lists his major career accomplishments, awards, and philanthropic interests. Most people in the art world might assume everybody knows who Larry Gagosian is and what he has done. Larry doesn’t assume that, which is part of what makes him who he is.

The key to understanding the strategic potential of resource influence, which Miller explains is “the ability to attract and deploy the resources you require to get your job done,” is how negotiating for and effectively using resources tends to lead others to entrust you with ever more resources. An example here might be the collector who casually asks if you could help them acquire a work by the hottest artist in the Western hemisphere, or resell a work from their collection for the maximum price the market will bear. Many younger dealers will give up after several failed, frustrating attempts at developing their skills or the right contacts in this competitive sideline of the business, but as we will discuss a bit more in the following section on the dealer “value proposition,” pulling it off once will not only ensure similar requests will pour in but will also strengthen your overall reputation in the market, which helps sell your own artists in the primary market.

In the contemporary art market, informational influence is very similar to resource influence. Information is, after all, the market’s most prized resource. Miller notes that the under-appreciated value of keeping tabs on the endless minor details of your industry is how it increases others’ reliance on your decision-making abilities. Fresh museum trustees may be confused by curatorial decisions that do not seem to jibe with the understanding of contemporary art they developed blending the values of their profession with the information they assembled touring a number of art fairs, but demonstrating that they can trust your decision-making abilities can make you a hero in two of the domains where you, at least, need to please others.

Dealers are more likely to need direct influence with their staff (or, sometimes, artists) more than with collectors. As opposed to positional influence, which essentially boils down to ordering people to do things, Miller explains that direct influence is being “firm, fair, direct, and confidential” in addressing someone’s inappropriate behavior. In addition to changing such behavior, when done well the respectful use of direct influence can gain dealers a great deal of respect in return, which collectors will pick up on in dealing with your staff. That, in turn, will influence their opinion of your trustworthiness and professionalism as well.

Finally, and particularly pertinent to our objective here, Miller describes relationships influence as the opposite of trying to be a “lone influencer.” Customized for the art market, her main message is:

When you take time to build great relationships across the human fabric of your [industry], you are less likely to need to resort to cajoling or persuading others to get things done. Instead of being the sole driver of an idea you can achieve a lot more by collaborating with people who know you and trust you.

Among the tools useful in getting collectors to want to get to know you, there are few better calling cards than another dealer’s recommendation. We all have opinions about each other’s programs, but I can always find plenty of good things to say about other dealers who have been generous or helpful to us. Don’t mistake this for sentimental, warm-and-fuzzy blather. In a machine greased by social interaction, it’s strategy. Everyone wants to know the person that everyone else likes.

Presenting the Gallerist Value Proposition More Compellingly

It makes no difference which mega-gallery wins the twenty-first century contemporary art market death match if—while we are all distracted by the repercussions of their bludgeoning ways—new intermediaries step in with innovations or services that enable them to take the business away from gallery owners entirely. Not only are social media and online channels nipping at gallerists’ heels, and auction houses making audacious incursions into the primary market, but with as much money at stake as there now is in the contemporary art market, unimagined challengers are sure to be right behind them. The white cube gallery model most gallerists fell in love with and adopted is less than 100 years old. It is silly to imagine it’s the only model that can serve artists well (which I know is hard to stay focused on at times, but truly is the fundamental purpose of the business we’re in). To maintain the gallerist model’s relevance, to both artists and collectors, may require messaging the gallerist value proposition more effectively.

Conversion strategy expert Peep Laja has one of the best explanations of what a “value proposition” is on his website Conversionxl.com:

A value proposition is a promise of value to be delivered. It’s the primary reason a prospect should buy from you.

In a nutshell, value proposition is a clear statement that explains how your product solves customers’ problems or improves their situation (relevancy), delivers specific benefits (quantified value), tells the ideal customer why they should buy from you and not from the competition (unique differentiation).18

Each gallerist should ruminate and develop their value proposition for their own business, of course, but if collectors in particular are opting out of the gallery experience, perhaps the entire industry needs to update how we explain why they should buy from us. The mechanics of writing a value proposition serve as a good clarification of what is meant by all this, as Laja’s recommendations demonstrate:

There is no one right way to go about it, but I suggest you start with the following formula:

• Headline. What is the end-benefit you’re offering, in one short sentence. Can mention the product and/or the customer. Attention grabber.

• Sub-headline or a two-or-three sentence paragraph. A specific explanation of what you do/offer, for whom and why is it useful.

• Three bullet points. List the key benefits or features.

• Visual. Images communicate much faster than words. Show the product, the hero shot or an image reinforcing your main message.

Evaluate your current value proposition by checking whether it answers the questions below:

• What product or service is your company selling?

• What is the end-benefit of using it?

• Who is your target customer for this product or service?

• What makes your offering unique and different?

Use the headline-paragraph-bullets-visual formula to structure the answers.

Laja offers other specifics, but notes that the “key role for the value proposition is to set you apart from the competition.” Why should a collector buy from a gallerist rather than directly from an artist or via an online website or at auction? We know what we do adds value to the transaction. We know the things we do to make collectors’ and artists’ lives easier. But because of how quickly things are changing in the contemporary art market, many dealers are perhaps less compelling when they discuss what sets them apart from many of the newcomers. It is hard to discuss what you don’t really know.

This is an issue. In an article published on Inc., Karl Stark and Bill Stewart, co-founders of Avondale, a strategic advisory firm, argued that to “create a compelling value proposition, you have to know your three C’s: competencies, customers, and competitors.”19 Again, we know how we add value (our competencies); we know what artists and collectors need (our customers); but, understandably, we grow more and more fuzzy when it comes to the explosion of new competitors. We will examine online art selling channels (which can be partners as well as competitors) in depth in Chapter 6, but here let’s look at what amounts to a value proposition for the profession on the website of the Art Dealers Association of America (ADAA):

• ADAA Membership

Membership in ADAA is by invitation of the Board of Directors. In order to qualify for membership, a dealer must have an established reputation for honesty, integrity and professionalism among their peers, and must make a substantial contribution to the cultural life of the community by offering works of high aesthetic quality, presenting worthwhile exhibitions and publishing scholarly catalogues. ADAA is dedicated to promoting the highest standards of connoisseurship, scholarship and ethical practice within the profession, and to increasing public awareness of the role and responsibilities of reputable art dealers.

• What Do ADAA Galleries Do?

ADAA’s members function as an important component of the U.S. art community, providing the means by which artists reach their public and collectors gain access to works of art. Exhibitions by ADAA members provide the first view of new works by both young and established artists and present works by previously neglected artists as well as works by acknowledged masters. (www.artdealers.org/about/mission)

This includes competencies (“must have an established reputation for honesty, integrity, and professionalism . . . and make a substantial contribution to the cultural life of the community”) and identifies its customers (“providing the means by which artists reach their public and collectors”); but there is no mention of competitors. Of course, this was not written to be a value proposition exactly, but I suspect the lack of any mention of “competitors” results from the long-standing fact that, until recently, its members’ only true competitors were each other.

Stark and Stewart advise: “Know your competition, their strengths and weaknesses, and develop a value proposition that meets the needs they are unable or choose not to address.” For galleries’ artists (one set of “customers”), the range of their needs most competitors cannot address as well is wide, including regular exhibitions of their actual artwork; a focused context defined by the reputation of the dealer and the other artists in the program; a presentation/installation design they can weigh in on or entirely control; a publicized period of time the actual work is available for viewing, with regular business hours; a context in which art critics can view the actual work and possibly write about it, etc. You may notice that “actual” appears repeatedly in that list, illustrating that one of the key things that sets galleries apart from any online competitor is that we provide a context where neither the viewer nor the art is virtual. It would be nice if that in and of itself were a compelling distinction, but increasingly it matters only in specific instances. Many longtime collectors report growing ever more comfortable making buying decisions from emailed JPEGs if they have seen the artist’s work in person before; at certain price points, not even that really stops them. Online representations undoubtedly offer very convenient means of sending and acquiring information, and it is understandable how that information is helpful in making certain decisions. But let’s not confuse any of that with the experience of seeing an artwork in person. One is about business; the other can be so much more.

As for collectors, as noted above, discussing their needs that galleries’ competitors cannot address as well is complicated by how collectors themselves are evolving. If they feel less and less need to rely on a dealer’s “authority” on contemporary art (other than those they view as consistently picking market “winners”) and become more and more ambivalent about the physical experience that gallery exhibitions offer, what competencies can dealers emphasize, or develop, that address their other needs enough to make a difference? There is a platitude in the business that most emerging and mid-level galleries have only a handful of actual collectors who truly support them. This is often discussed as a negative (or a warning to artists to consider the consequences for their careers if they work with that gallery), but what if this were framed instead, as they say in software, as a feature rather than a bug? What if dealers openly developed a roster of core collectors in the same way they do a roster of artists, offering them extended services (such as collection management, museum correspondence, exclusive newsletters with market analysis, or recommendations for other artists based on their tastes)? It could be a blending of art dealer and art consultancy services. In return, the collectors would quite literally commit to buy enough from the gallery to fairly compensate the dealer for such services.

Many of us do much of that in various ways already anyway. Perhaps standardizing it and, more importantly, describing it as a competency that adds value might convince more collectors to form close relationships with a dealer or more dealers. Nothing in this idea would stop them from buying from other galleries, but it could help bring collectors and dealers back into closer partnerships. It’s an idea, anyway. I toss it out as a means of hopefully sparking a dialogue on similar thinking, not because I am convinced it alone could solve all these issues. Along the same lines, another observation I would like to share came from Annette Schönholzer, former Director of New Initiatives at Art Basel, during a conversation about the state of the contemporary art market (in an interview for this book). Annette said:

If you go to Asia, if you go to China, if you talk to gallerists there, the gallery might run the gallery, a foundation, a freight handling company, a residency program, and maybe an interior design company. And in the West we go “this is crazy,” because only one of the five things this gallery is doing is actually being a gallerist. And this kind of diversification, of fluidity in doing business that is so foreign to us, is common all over Asia. And it works because they don’t have to rely on one single thing to cross-fund what it is they’re doing.

In Chapter 5 we will discuss a few other “complementary businesses” that art dealers have maintained to fund what it is they are doing, but across the board I feel the “value proposition” of the gallery may need to be more clearly articulated to collectors, and possibly to the entire art world as well.

Finally, I cannot leave this topic without adding that, as noted above, the sheer number of galleries that exist now exacerbates all this as well, and not only in numbers. It’s the Wild West out there, and so, unsurprisingly, business practices vary wildly, possibly dissuading collectors from trusting an industry that seems to have no standards. No one has the right to tell anyone else they should not open or should close their gallery (sales of my first book might plummet, and I’d be quite displeased about that), but as Annette also told me:

I don’t think that the gallery scene is very good at regulating itself. There’s no benchmark for how you get in or out. If you have enough money, you can put your space in a great location, make yourself more visible, all these kinds of things, but again, in the end . . . nobody really, openly points a finger at the other person.

I took this to be Annette’s polite way of saying some of the problems the gallery system is experiencing come from inexperienced (or experienced) dealers making mistakes (or committing crimes) that reflect poorly on the entire industry, and it behooves the industry to clearly condemn such behavior. From an established uptown gallery indicted for knowingly selling forgeries; to a mid-level gallery who faked certificates of authenticity to sell works from a foundation they then reported stolen; to a young dealer who, rather than make amends when they resold a collector’s painting they were holding, had someone create a very bad duplicate of it they tried to pass off as the original (all true stories); and countless others, a collector looking for evidence to support their suspicion that buying from a gallery was a risky venture would find plenty. In an age when transparency is increasingly being demanded by consumers, a compelling value proposition may also require explicating how dealers are systematically developing and adhering to ethical business practices. Many associations, art fairs, or other public-facing opportunities for promoting a gallery already decline to work with dealers who do not adhere to the “honesty, integrity and professionalism” standards that reflect poorly on us all when not followed. Although no individual wants to be that dealer who points fingers, there must be ways to distance the ethical dealers from the practices that weaken our collective value proposition.

SUMMARY

The size of the contemporary art market has grown to historic proportions partly via an influx of new private collectors with views on how the market and non-commercial institutions should operate that differ from those who defined the smaller circle of art patrons a generation before. Confident in their own judgment, the new collectors are notably ambivalent about the opinions that museum curators, critics, or other “authorities” hold, particularly when making purchase decisions for their own collections. For dealers who have traditionally traded in being an “authority,” this poses new challenges in developing close relationships with these collectors, a strategic advantage in building their gallery that has become all the more crucial as online channels, auction houses, and other players make new inroads as intermediaries in the primary market. Whether through development of new competencies that meet collectors’ and artists’ needs, diversification of the services that fund their gallery, or delivering a more compelling value proposition, gallerists clearly need to respond to the evolving role of the private collector in the contemporary art world.