CHAPTER 8

John Ford's Later Masterpieces

“The Searchers” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance”

THE SEARCHERS

The great master of the American Western film, John Ford, played a key role in the transformation of the genre that took place between the end of World War II and the mid-1960s. Ford's postwar cavalry films, as discussed in chapter 7, introduced narrative-related elements of revisionism that included critical views of expansionist idealism, Western heroism, and the confrontation with Native Americans. His classic My Darling Clementine is noirlike in certain aspects of its visual scheme and most especially in its focus on the morally and psychologically complex character of Doc Holliday. It should not be surprising, therefore, that Ford deepened this kind of exploration in two later masterpieces, The Searchers (1956) and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

The Searchers features Monument Valley and John Wayne in equal and glorious measure. Frank Nugent, in his collaboration with director Ford, crafted a brilliant screenplay that was based on a novel by Alan Le May. The landscape and the reluctant hero are inseparable; in the relentless sun of the desert valley, the toughness and intractability of the one infuse the other. Ethan Edwards (Wayne) had left this land to fight in the Civil War. His current and constant roaming among the majestic rocks, in a tireless search for his captured niece, is in furious response to all that he has lost. His quest becomes a search for his lost soul. The movie is more complex in moral structure than Ford's earlier Westerns, specifically in regard to its pair of male protagonists: one is white and racist, the other mostly white but “one-eighth part Cherokee.” The taint of Indian blood lends tension to their desperate efforts to protect and defend two white girls from death or, worse, defilement by “savages.” And while some, like director and film scholar Lindsay Anderson, have criticized the way in which Ford heavy-handedly juxtaposes intense drama and broad humor in certain sequences of The Searchers, the film in fact draws even more attention to its sense of tragic loss by contrast with the scenes of comic relief.1

The movie gained mixed reviews upon its release but has grown exponentially in stature over the years; it is now rated widely as one of the great American films. As Edward Buscombe has stated in his book on The Searchers, summarizing general reasons for the greatness of the film: “At the dawn of the second century of cinema The Searchers stands, by general assent, as a monument no less conspicuous than the towers of stone which dominate its landscapes. The strength yet delicacy of its mise en scène, the splendour of its vistas, the true timbre of its emotions, make it a touchstone of American cinema. The Searchers is one of those films by which Hollywood may be measured.”2

Prior to The Searchers, Ford had filmed five Westerns (entirely or in large part) in Monument Valley, which belongs to the Navajo Tribal Park. So attached were Ford and the Navajo people to each other that Ford was given an honorary nickname by the tribe: “Natani Nez” or “Tall Soldier.” Wayne was nearly as familiar with the valley, having starred in four of these films. Aside from two other superb Ford Westerns of the mid-twentieth century that were mostly shot in other locations (3 Godfathers and Wagon Master), these five films—Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and Rio Grande—constitute as fine and as accomplished a body of work as any Hollywood director's career Westerns (those of Hawks, Mann, Boetticher, and Peckinpah included). Yet these movies precede Ford's two most meaningful Westerns and cannot fully prepare us for the awesome scale, scope, beauty, harshness, terror, and cruelty of The Searchers.3

In the later phase of his career, Ford brought a more critical approach, not only to his depiction of the westerner, but also to the overall story of the evolution of the Old West. Ford had already hinted at this deromanticizing turn, in Fort Apache, in which the conflict between heroic ideal and flawed reality is emphasized, and in Yellow Ribbon, where the military hero meets with repeated failure before retirement (see chapter 7). The Searchers, Sergeant Rutledge (1960), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and Cheyenne Autumn (1964) were the results of Ford's later desire to complicate and demythologize such a story. Sergeant Rutledge explores issues of racism and injustice in the western cavalry, and Cheyenne Autumn empathizes with the perspective of the suffering Indians who attempt to journey homeward after being confined and dehumanized.4 But The Searchers and Liberty Valance are the true masterpieces within Ford's later project of disclosing the dark underbelly of the American West's progress from wilderness to civilization.

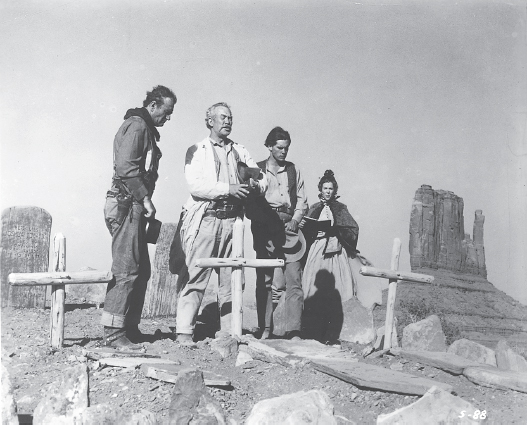

FIGURE 38. The funeral rites for the Edwards family are about to be interrupted by a westerner's angry impatience in John Ford's classic Western The Searchers (1956). From left to right: Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), the Reverend Captain Samuel Clayton (Ward Bond), Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), and an unidentified woman. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Despite the losses, sacrifices, and obstacles that the Western hero must overcome, and along with an acute awareness of the morally questionable side of the westerner's personality, Ford almost always offers us an overall sense of optimism about the social and political advances that the Western communities depicted in his films are undertaking in their quest for a more rational order of existence. For example, even though The Searchers presents us with a clear portrait of the horrors and struggles that the settlers and ranchers in the West often had to face, there is a notable expression of forward-looking determination given by Mrs. Jorgensen (Olive Carey, the real-life wife of early Western star Harry Carey Sr.) to her husband (John Qualen) and guest Ethan Edwards. Despite the deaths of her son and of the Edwards family at the hands of the Comanche, and in spite of the fact that they must now endure the ongoing brutality of such a hard land, Mrs. Jorgensen predicts better things to come if they stay the course: “It just happens we be Texicans. ‘Texican’ is nothing but a human way out on a limb, this year and next…maybe for a hundred more. I don't think it'll be forever. Someday this country is going to be a fine good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

The Searchers is hardly a nihilistic movie, especially if we take as our guidelines Mrs. Jorgensen's prediction and Ethan's act of self-redemption at the end of the film. It is a film about heroic sacrifice and retribution, with an underlying lesson about the need to hope for better days to come. But as much as this film teaches us about the beauties and triumphs of the human spirit, it does not shy away from the specter of death and destruction. Beyond the borders of family and community reside the emptiness and danger of the desert and mountains. The film continually reminds us of the abyss of nothingness that always lies on the other side of our desire to persevere. With such a realistic and pragmatic lesson in mind, we learn a newfound respect for those larger-than-life figures, like Ethan Edwards of The Searchers and Tom Doniphon of Liberty Valance, who have helped to clear a path in the wilderness so as to make way for a more ordered and civilized world.

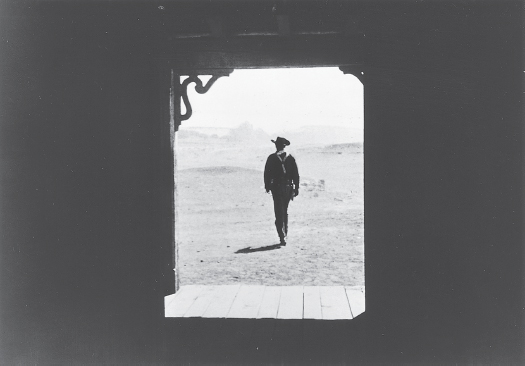

It is 1868 when Ethan, an ex-Confederate soldier, returns to the Texas home of his brother Aaron (Walter Coy), his sister-in-law Martha (Dorothy Jordan), and their three children. He appears out of the desert suddenly and inexplicably, first glimpsed by Martha as she exits her front door in the opening shot to get a better view of the approaching “stranger.” We view her as she moves from pitch-black interior to gloriously sunlit exterior, a rectangular-framed ode to the beauty of Monument Valley and presented in a manner (a frame-within-a-frame) that implicitly emphasizes the way in which theater audiences will experience the landscape of this film through a similar rectangular “window” onto the world (i.e., via the movie screen in a darkened cinema). The film's recurring use of doorways and cave or tepee entrances as framing devices invites multiple interpretive possibilities, ranging from a straightforward contrast between home and wilderness to the more intriguing suggestion of the interior as a kind of “womb” from which Edwards (and other solitary, celibate westerners like him) are typically excluded.

FIGURE 39. The iconic closing shot of The Searchers: Ethan Edwards departs once again into the desert, framed by the doorway of the Jorgensen home. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Some avid students of The Searchers, and Peter Lehman most notably, have proposed various ways in which the opening shot of the film, with its obvious contrast between interior and exterior, should be understood symbolically—especially given the recurrence of this kind of contrast in other framing choices throughout the movie, including the famous closing shot that parallels the opening of the film.5 However, in his persuasive article “Ways of Knowing: Peter Lehman and The Searchers,” Tom Paulus argues that Ford's use of the aperture shot in such scenes might be more convincingly understood as a pragmatic way of dealing with the widescreen Vista Vision process used for this movie, a process that welcomes strategies for dividing up the screen and focusing the audience's attention—and possibly also as a tribute to Ford's own similar use of such framed shots (for practical filmmaking purposes) in his earlier silent Westerns.6 Either way, Ford's recurring use of such a framing method makes for magical images that allow the viewer to sometimes feel as if she were viewing, or even being drawn into, a Romantic landscape painting.

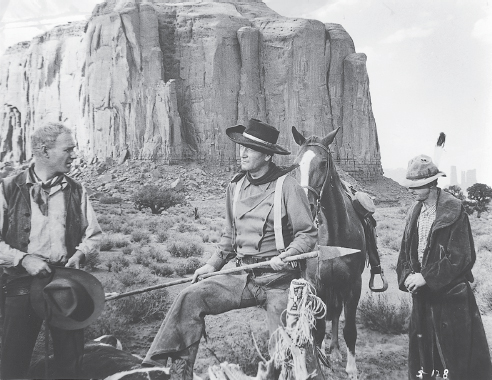

FIGURE 40. “The searchers” confer over a recently discovered Comanche spear, framed against the Monument Valley landscape. From left to right: Brad Jorgensen (Harry Carey Jr.), Ethan Edwards, and Mose Harper (Hank Worden). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Ethan's arrival is a moving homecoming as the family wonders where he has been for the three years that have passed since the Civil War ended. He is uneasily welcomed back into the family structure, and he awkwardly recognizes Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), the part-Cherokee youth who was adopted by the Edwards family when his parents were massacred. In the few brief opening scenes, Ethan is revealed as the classic westerner: a southerner who fought in the Civil War on the losing side and who has no choice but to become a westerner. He is the epitome of the gunslinging hero who is a “good bad man”—a person who has been on the wrong side of the law for a while (presumably as a gunfighter)—as well as an outsider, a loner with no lover, partner, or best friend to need or guide him.

In a conversation with Peter Bogdanovich, the irascible Ford made it clear that Ethan's true love had been Martha, now his brother's wife: “Well, I thought it was pretty obvious—that his brother's wife was in love with Wayne; you couldn't hit it on the nose, but I think it's very plain to anyone with any intelligence. You could tell from the way she picked up his cape.” This explains the degree of awkwardness in the homecoming and suggests one of the possible reasons for Ethan's reluctance to return to his brother's home for so long after the end of the war. Ford also indicated in his interview how we might imagine Ethan's background in the years following the war: “He's the man who came back from the Civil War, probably went over into Mexico, became a bandit, probably fought for Juarez or Maximilian…. He was just a plain loner—could never really be a part of the family.”7

The viewer is nevertheless left with an intentional mystery concerning Ethan's past, and most especially what he has experienced during and just after the war. And unlike other 1950s Westerns such as Jubal and The Naked Spur, discussed in the previous chapter, The Searchers does not provide us with any character-revealing secrets about the main character's recent past, other than the fact that he fought in the war and returned home with a suspicious stash of newly minted gold coins. Ethan's psychological complexity is demonstrated through his present words and actions; and the movie's “strategic opacity” about Ethan's biography (other than his past love for Martha and his ingrained familiarity with the landscape and with his Indian enemies) makes that complexity even more pronounced.8

Ethan is the knowing westerner who grew up in the wilderness of the southwestern Texas desert and profoundly understands the terrain, its dangers, and its inhabitants. He is an expert on the Comanche, especially their tricks and their murderous methods; equally well does he recognize and mistrust the white man who will kill for gold. He is a descendant of Lassiter, Zane Grey's rider of the purple sage who was also a gunfighter preoccupied with finding his niece. Like Lassiter, Ethan is at one with the landscape; he is ever impatient to be in it, on the move to somewhere. He, too, is a man of violence, who lives by the use of his gun.

Ethan cannot stay indoors, whether during his initial homecoming, when he goes out on the porch as the family retires to bed, throughout his years of wanderings, or at his final homecoming, when he stands outside the sheltering doorway and turns away, stepping off the porch into the desert, alone. Ethan is in the landscape, and he is of it as much as the Comanche he despises; but he is the more skilled survivor, facing death at the Indians' hands again and again, seemingly without fear. He was an experienced rebel soldier, after all, and perhaps also was a gun-fighter in Mexico, as Ford had suggested to Bogdanovich. We are fearful for him, though this extrasized hero replies calmly and comically to such threats—“That'll be the day”—just as he does to Martin Pawley's anguished attempts to be a grown-up. So fearless is Ethan that he never hesitates in his pursuit. He is cunning and cruel, and the pursuer becomes as frightening as the pursued, and just as vengeful.

Lassiter and Ethan belong to different eras of American culture and are products of different perceptions of the West. Lassiter is taught forgiveness by Jane Withersteen. A wealthy rancher, Jane is a kindhearted, generous, and gentle heroine who naively opposes vengeance and retribution until her love for Lassiter conquers her better self. Redemption for Lassiter and Jane is achieved by Lassiter's rolling of a very large stone, Balancing Rock, which murders the villains and locks the lovers forever in the hidden valley beyond Deception Pass. Ethan has no such redeemer. His story is the tragedy of a loner, told at mid-twentieth century—and consequently more pessimistic, perhaps, because its absolutes are shaded in modernist colors. For Edwards is an angry man, angry in every muscle of his towering body and grim face. His gestures are big: his arms swoop to quickly fire his rifle or six-gun or to indicate another meaning of Comanche strategy. He seems immensely powerful, yet he is also swift and graceful as both gunfighter and rider. He speaks in clipped sarcastic phrases, punching out words to emphasize his bleak perception of people and their frailties.

Ethan is, in a name, John Wayne. We cannot imagine another Ethan Edwards; like landscape and character in The Searchers, Wayne and Edwards are one. Not since Red River has Wayne played a character so driven by anger, pain, and the sheer will to survive the challenges of a harsh Old West. In Red River, Wayne's Tom Dunson loses his true love early in the narrative; he is saved, in part, by a young girl, Tess, who carries on the spirit and beauty of his lost Fen, and he ultimately forgives the young Garth, his adopted son, because of Tess (see chapter 6). In The Searchers, Ethan's love, Martha, was lost to him, first through her marriage to his brother, then by the brutality of the Comanche. Ethan has little to sustain him throughout his wanderings to find Martha's two daughters—no gal of his own to write to as Martin Pawley has in Laurie Jorgensen (Vera Miles), though Martin sends her but one letter in five years.

Not unlike the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, Ethan is driven by a deep desire for revenge. He is hardly a kid, however, and he often exhibits questionable traits, such as intolerance and an absence of sympathy. Ethan gives in to his rage-filled impulses at certain moments and also reveals his inability to settle down, as is conspicuous in the famous final shot of the movie. Ethan is highly unpredictable, as when he shoots bullets into the eyes of a dead Indian so as to make his spirit wander forever. He is also quite willing to put others' lives at risk when the situation demands it, as when he uses Martin as a sitting (in this case, sleeping) duck, knowing that they will most likely be ambushed by the greedy Mr. Futterman (Peter Mamokos). Ethan does not seem to care whether using an unsuspecting Marty as a decoy might endanger the younger man, and Futterman does indeed get off a shot before Ethan kills him. Luckily, Futterman misses, and Marty quickly realizes that Ethan has callously imperiled his life.

The violence in the film—ranging from the Comanche massacre of the Edwards family and Ethan's discovery of Martha's ravaged corpse to Ethan's finding of Lucy's body and his later scalping of an already dead Scar—always takes place offscreen, leaving such horrific acts and scenes to the power of the viewer's imagination. This is a movie about violence that does not reveal its violence directly to the audience. As Buscombe correctly observes in his book on the movie: “The most heart-wrenching scenes in Ford are when the emotion is only half expressed. ‘Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/Are sweeter,' Keats wrote. Ford knew the same applied to moments of anguish. It's extraordinary how many moments of violence are suppressed.”9

Ethan is undoubtedly Ford's most complex and problematic hero. This has much to do with Ethan's commitment to avenging his loved ones' murders, and this desire for retribution is fueled most intensely by his hatred of “the red man” and, later on, by his fear that his niece Debbie (Natalie Wood) has been sexually defiled by Chief Scar (Henry Brandon). We would not regard Ethan as morally ambiguous, most likely, if he were simply a killer bent on revenge solely for justified purposes, but his thirst for vengeance is mixed with blatant racism. Ford (along with screenwriter Nugent) makes this clear throughout the film. Marty, for example, tells Laurie that he fears what Ethan might do to Debbie when he finds her, based on the way that Ethan looks when he even hears the word Comanche. And Ethan later confirms our worst fears when, pistol drawn, he orders Marty to “stand aside” so that he can get a clear shot at Debbie after she has run to rejoin them. While revenge against Scar for the murders of Ethan's loved ones may earn our sympathy, his urge to destroy his niece if she has been assimilated by the “Other” tends to raise major questions about his morality. Such questions lend psychological depth and complexity to the character of Ethan. The viewer already feels troubled, in fact, by the very possibility that a character played by John Wayne even contemplates such an action—just as some viewers may be disturbed, say, by the idea that Cary Grant plays a potential wife-killer in Hitchcock's Suspicion (1941).

Ford's camera zooms in on Ethan's face as he visits a fort where white females who have been rescued from captivity are being sheltered. Ethan voices his view that these women are now “Comanche”: he equates physical defilement with total assimilation. Ethan turns at one point and offers a sober glance back at one white woman who has visibly lost her mind after such horror and suffering. The woman plays with a doll, blank-eyed and insane, evoking a nightmarish analogy with Debbie, who had also clutched a doll when she was taken by Scar. The rapid zoom-in that allows us to focus on Ethan's disturbed reaction makes for a powerful shot, and Wayne's facial expression connotes what Ethan is really thinking, without the need for words—true to Ford's great talent for substituting images for dialogue.10 Ethan confirms for himself here that by killing Debbie—if she indeed still exists, and if he does finally find her—he would be doing her a favor after she has been, in his eyes, so dehumanized, so “scarred.” He now sees Debbie as little more than an inanimate object, symbolized perhaps by the doll clutched by the mad woman in the fort as well as the doll held by Debbie when she was a little girl.

Ford and The Searchers have often been charged with racism, given that the director along with his screenwriter mythologizes a violence-prone westerner who harbors such a deep hatred of his Indian enemy. The film appears, on the surface anyway, to justify Ethan's obsessive desire to destroy Scar and the Comanche, given the horror of what has happened to the Edwards family. That seeming justification is complicated, however, by the fact that Scar later claims to have massacred the white people in the area because his own sons were killed by the whites. And what truly amplifies the movie's emphasis on the portrait of Ethan as an avid racist is his eventual desire to destroy Debbie rather than to save her. The idea of her sexual defilement at the hands of Ethan's enemy, an enemy who has killed (and may also have raped) his beloved Martha, is too much for him to bear. He would rather see Debbie's “infected” body dead and her soul liberated than continue imagining her at the side of Scar. Ethan's concern with the possibility of Debbie's physical impurity and his implicit goal of saving her soul harkens back, in fact, to the start of the movie, when the Reverend Captain Samuel Johnston Clayton (Ward Bond) asks little Debbie (Lana Wood) whether she had been baptized. If Ethan is willing to kill his own niece, someone for whom he has searched for seven long years, chiefly because of her sexual union with a Comanche, then it is clear that he has come to view one's assimilation to another race as a defining property of that person.

Further, Ethan's attitude is doubly complicated because he and Scar seem to mirror one another as creatures of the wilderness. As Edward Buscombe states, “Scar, the Comanche chief whom Ethan pursues, is in some sense Ethan's unconscious, his id if you like. In raping Martha, Scar has acted out in brutal fashion the illicit sexual desire which Ethan harboured in his heart.”11 Jim Kitses similarly observes, “When the family is massacred and Debbie abducted by the Comanche, their leader, Scar, comes into focus as a distorted reflection of Ethan himself.”12 And as Tag Gallagher tells us, “For the white Ethan Edwards (John Wayne), the Comanche Scar is the ‘Other' that he can stare at but cannot see. Worse, he is Ethan's doppelganger, everything in himself that he despises…. Thus Ethan must kill Scar in order to destroy the complex of violence within himself.”13

Gallagher views Ford's film as filled with clearly intentional examples of racist distortions and demonizations of the “Other”—including Ford's very use of a white actor as Chief Scar—and yet maintains that the film is not itself racist. This is because The Searchers makes this theme prominent and invites the audience to reflect on such a theme, an invitation that is especially pronounced in terms of Ethan's own “mirroring” of Scar. This is a convincing reading of the movie, one that does justice to the complexities of the narrative. Such an interpretation is also supported by obvious tensions and contradictions in the movie—such as the fact that Ethan and Marty treat Marty's newly acquired “wife” (“Look”), the Indian woman whom he had unwittingly purchased, in a highly derogatory fashion, and yet they both show clear signs of mourning her death later in the film.

Ford and Nugent make us pause elsewhere at times when we are called on to judge the Comanche as pure savages who deserve their fate. Ethan is not the only racist in his community, since Laurie later tells Marty that if Debbie were indeed living with Scar, then she (along with Martha, were she still alive) would have also wanted her dead. Debbie, when Ethan finally finds her, appears as a serene and well-assimilated member of Scar's tribe, not having suffered the kind of mistreatment and cruelty that drove the rescued females at the fort to lose their minds. And perhaps the most puzzling examples of contradiction or peculiar juxtaposition in the movie are the radically sudden transformations in thinking that are undertaken by both Ethan and Debbie at the very end of the film. Debbie, who steadfastly told Marty that she did not want to leave her “people,” quickly changes her mind almost overnight; and of course Ethan decides in a split second to save Debbie rather than destroy her once he has elevated her in his arms.

There is therefore good evidence from the intricacies and complexities of the film that Ford, who had played upon and against stereotypical characters throughout his long career, created a movie that is not itself a racist “object” but rather is one in which racism is made a thematic subject of consciousness-raising, evoking questions rather than delivering absolute value judgments. Kitses also follows this approach in his analysis of the movie, though he wisely qualifies this interpretation by emphasizing that the movie provides a highly “unequal treatment of white and Indian worlds,” given the focus throughout the film on the perspectives of those assaulted by or pursuing the Comanche.14 As Kitses puts it, “Ford's design is to force the audience to confront its own racist inclinations as Ethan's extreme state becomes clearer…. Any claim that the film embraces racism and demonises the Comanche must account for Debbie's assimilation and the film's dark portrait of its hero.”15

The character of Ethan reminds the viewer that the path to civilization begins in the heart of the wilderness, and that the establishment of what is “reasonable” and “good” sometimes demands acts and methods that might be deemed “irrational” or “evil” according to society's conventions. The instincts that lead to necessary or praiseworthy actions may also result in the eruption of chaotic, dangerous impulses at times: they emerge from the same subconscious wellspring of emotion. For instance, in one notable scene where winter snows have fallen and the searchers' hunger has become intense, Ethan shoots at a herd of buffalo with the need of sustenance clearly in mind. Yet Ethan continues firing wildly at the herd even after the animals have scattered. Marty, shocked by Ethan's sudden release of irrational energy, recognizes that this act of useless shooting makes no sense. He attempts to knock Ethan's rifle to the ground and the older man, half-crazed and eyes blazing, strikes Marty to the earth and grabs another rifle so as to continue the frenzied firing. Ethan expresses his desire to keep the Comanche from feeding on these same buffalo by destroying the herd, a visibly futile task, and his demeanor is no longer that of a rational man.

FIGURE 41. Ethan Edwards returns to the Jorgensen home with the rescued Debbie (Natalie Wood). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

We witness Ethan's fury unleashed, but it is this type of anger that drives him continuously toward his goal of finding Debbie and killing Scar. It is also the kind of passion and determination, no matter how excessive it may become, that was sometimes required in eliminating a threat from a savage land and in clearing a way for the arrival of civilization. In conquering a wilderness and building a nation, the power of ideals is inherently limited, even fragile, given the resistance of reality. And brutal violence is often required in removing obstacles to progress, or so the Western myth often tells us. Ford's later The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance makes this point even more emphatically.

After his Comanche enemies have been eliminated, Ethan brings Debbie home; he does not, as Martin fears, kill her. It is as if the physical act of picking up Debbie in his arms once again, as he did during his homecoming when she was a little girl, is enough to convince Ethan that he has been wrong in wanting “Debbie” (i.e., her defiled body) dead.16 According to such an interpretation, this is a moral awakening triggered by a nostalgic remembrance that is in turn occasioned by the physical embrace of a specific individual. Ideologies and stereotypes do not matter here as much as direct human contact and the value of a unique person, especially if she is the daughter of a loved one. And Ethan and Marty are, at the end of their long journey together, reconciled.

The final return of Ethan, Martin, and Debbie to a safe homestead must be in memory of Martha. Though hearth and happiness are unattainable by Ethan, he has overcome his hatred, and he acts, finally, out of love. In this sense, Wayne completes the portrait of the classic westerner that was conceived by Harry Carey Sr. and William S. Hart: the “good bad man” who responds to a woman in a way that reforms his character and makes him do what is right, even if it means riding off alone at the end. In the final shot, Ethan turns away from the house, grasping his arm as he steps off the porch—most probably in tribute to silent Western star Harry Carey, who made such a gesture his trademark.17 Ethan turns away from the present into his memories of the past, and most especially his memory of Martha. It is a moment he must hold alone; it cannot be shared. Such reflection covers the deepest emotion, and it almost overpowers Ethan as it does us, for here we have reached the deepest layer of the Western, the sense of what has been lost in the struggle. The search may have helped Ethan find some part of his soul, but he will never recover from all that he has lost as soldier, brother, and lover.

THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE

No longer mourn for me when I am dead…

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse,

But let your love even with my life decay,

Lest the wise world should look into your moan

And mock you with me after I am gone.

—William Shakespeare, Sonnet 71

Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance is perhaps the most meaningful, the most tragic, and the most emotionally powerful of all Western films. It takes on the notions of myth and legend and the theme of nation-building, with all the complexities and contradictions that come with imposing new law on an older and more primitive order. The movie is full of ambivalence and sorrow but leavened with comic villainy and journalistic wit. With Liberty Valance, Ford brought Shakespeare to the screen, as he had begun to do with My Darling Clementine. But unlike many other Ford Westerns, this one is not as visually striking and hardly makes use of any on-location shooting in authentic Western terrain. Most likely Ford meant for us to focus exclusively on the tragedy and its characters and ideas. The action is shot in black and white and set on a small stage, tight and compressed so its protagonists cannot escape into the depth of the landscape.

In creating a dialogue between truth and myth, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance sets a tone of intense nostalgia and loss. The code of the Old West must be superseded by a system of law and order based on the ideas of state and federation; the knight with a gun gives way to the scrivener of law. Overriding all else is the notion that the new is possible only through the sacrifice of the old. The irony is unmistakable: true nobility is shown by the gunfighter who kills the outlaw but lets the credit go to the lawyer, the man who literally cannot shoot straight. Liberty Valance, which presents the late-nineteenth-century phase of the settlement of the West through the imposition of law and the growth of an ordered society, nonetheless mourns the loss of a heroic past and questions the results for modern times. It is a revisionist film, growing out of the transformation of the genre that began in the immediate post-World War II era and that was developed through the works of directors such as Mann, Daves, and Boetticher (see chapter 7). And while the movie is visually stylized in the manner of one of Ford's early silent Westerns, it is revisionist in terms of its narrative trajectory—particularly given its critical questioning of the Western mythos and its eventual “deflation” of the two men who otherwise would have been its heroic exemplars. As Jim Kitses remarks, “If Liberty Valance appears to be Ford's ultimate personal statement, it is because the film evidences a post-modern complexity, at once nostalgic and critical, a celebration of myth and its deconstruction, a radical recycling, the director's dual vision brought here into its sharpest focus.”18

As we have seen earlier in this chapter, The Searchers is obsessed with loss, but there is a kind of rebirth or redemption through mutual forgiveness. Edwards has survived, though he must go on alone. Hawks's Red River also concludes with forgiveness, or at least understanding, among Tom Dunson, Matthew Garth, and Tess Millay, through a final scene twisted into a comic mode (see chapter 6). Liberty Valance offers no such comfort: its opening and closing scenes are the Western's most melancholic. At the start we see that symbol of modern civilization, a train, bringing Senator Stoddard (James Stewart) and his wife, Hallie (Vera Miles), from the East to Shinbone in their home state to attend a private funeral; the time is the early twentieth century. Later that same day, after their visit and the senator's telling of the “true” history of their lives, another train takes them away again. As the locomotive pulls its passenger cars out of town, we see the politically important man and his wife seated together, aged and tired, not at all heroic but rather deeply, sorrowfully aware of what has been lost.

The central narrative is tightly enclosed between the arrival and departure of this elderly couple. Their mourning, and ours, can only be understood once we have learned of their earlier years in Shinbone, for this is a mystery story as much as it is a Western. The true hero (John Wayne as Tom Doniphon) has died before the film begins, and his story is unfolded in flashbacks during the wake for this forgotten man. Introduced by Stoddard, the principal and extended flashback begins with the robbery of a stagecoach. The holdup is brutally carried out by the archetypal outlaw, the man with no morals known as Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin), who rampages throughout the territory, unchecked by local law. Stoddard, a young lawyer brimming with moral idealism, is whipped and his law books are torn apart. Out of this humiliating start he will become a hero, considerably helped along by Doniphon, who is another kind of gunfighter, thoroughly unlike Valance.

After the holdup and beating, Doniphon finds Stoddard and brings him to Shinbone. Later he will rescue Stoddard at the moment of crisis, the inevitable showdown. Since it is Wayne who portrays this enigmatic savior, he should be the true hero of our story, even if a reluctant one. But since Jimmy Stewart plays the lawyer, he must also be the hero, though his self-righteously angry character makes us occasionally squirm (as do Stewart's expert portrayals in Hitchcock's thrillers and Mann's Westerns, expressing what David Thomson aptly calls “his suppressed malevolence as an adventurer hero”).19 Here is a struggle of mythical dimensions. The gods' favorite heroes have strength and power but are flawed; egocentric and jealous, their ultimate duel is with each other. But the struggle takes a surprising direction when love comes up against reason, and he who loves the most makes the necessary sacrifice.

Doniphon's love is the old-fashioned kind, a seemingly selfish and possessive love for Hallie, a pretty but uneducated woman. He intends for her to work hard at his side to build a ranch and raise a family. Stoddard's love is that of the teacher, who gives his heroine a new life by instructing her to read and write. Hallie will be his helpmate in his future career as a major figure in the nation's government. But there is no doubt where Hallie's heart lies, both at the beginning and the end of Liberty Valance, and her tears are ours as we come to understand her personal loss. The new civilization, of which our lawyer-hero is a leader, has taken Hallie far from the land and the people she loves. She is the wife of the first governor of the state, who subsequently becomes its senator and is viewed as a future vice president. But life in Washington has offered Hallie no cactus roses.

We see the rose in bloom but not its color, since this is a black-and-white film. Liberty Valance opens on a brief shot of the landscape, intimate and contained—pretty enough to be Ford's landscape of memory, his beloved Ireland, but for the sagebrush. We watch as that great instrument of Western progress, the train, comes round the bend carrying easterners in comfort and security to a newer, safer, more modern society. Interestingly, in this Western we are not told the date or which state this is (although the short story that is the source of the film declares the date of the funeral as 1910).20 A couple arrives quietly in Shinbone: too quietly for the press, who will demand an explanation, on our behalf as much as their own. But we already know, because of the sorrowful stillness surrounding this pair and the silent anguish of the woman clutching a large hatbox, that this is a journey into the past. This film wrenches the heart at its beginning, in its deceptive simplicity, its economy of dialogue, and its deliberate pace that is enhanced by the whistle of the train. There is no major musical theme to clue us in; the opening scenes are all the more powerful for their strong contrast to the Cyril Mockridge score played heartily through the credits. There is no preamble of jolly, bustling town folk tipping hats, no “Howdy, Ma'am” outside the general store, no kids playing with dogs, no happy ranchers driving up in their wagons.

Liberty Valance is all business—and a sorrowful, bitter one it is indeed. An old man, Link Appleyard (Andy Devine), greets Senator and Mrs. Stoddard at the station, and she is achingly glad to see him, moving along to his buckboard wagon and holding her hatbox tightly. A youthful reporter excitedly telephones his boss about the senator's arrival and then begs Stoddard for an interview. It does not take much to distract the senator from the purpose of his visit. When the editor of the Shinbone Star adds his request, the senator becomes the pompous glad-hander and tells Hallie that he is “back in business again—politics.” He asks Link to take his wife for a drive while he mends “a few political fences.”

Hallie sits in the buckboard, her steady gaze quietly registering her sorrow, not bothering to respond to her husband's change of plan. As a politician's wife she must be used to it, yet it cannot matter to her, wrapped as she is in her solitude, nearly overcome with her remembrance of the past. Hallie talks to Link of the changes in Shinbone, and with a catch in her voice she observes its “churches, high school, shops.”

Without even looking at each other, the old friends exchange thoughts and decide to ride out “desert way” to have a look around. As Link and Hallie arrive at a burned-out ranch, music slowly rises with the mournful air “Ann Rutledge,” the haunting theme from Ford's earlier film Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) and a song that therefore symbolizes (for Ford fans, anyway) the death of a loved one. Hallie points to the cactus roses and looks at Link. He knows, without any words spoken, that she would like for him to retrieve one of the roses so she can put it on Tom's coffin.

The metaphor of the garden will play an essential role throughout the film, especially when contrasted with the idea of the wilderness, that primitive chaos from which a cultivated civilization (“the garden”) will, one may hope, emerge. It is true that the town of Shinbone, back in the early days when Valance still threatens the townspeople and statehood is yet a distant dream, should certainly not be confused with some Hobbesian “state of nature,” a completely lawless condition in which humans are always on the verge of potential warfare with one another as a result of ego-driven competition for limited resources. There are many good-hearted people in Shinbone who, while not fully capable of defending themselves against Liberty Valance, have already entered into an unwritten agreement (what English political philosophers John Locke and Thomas Hobbes would call a “social contract”) to get along and live together within an ordered community. There is also a sense of basic law, even if the enforcer of that law, Link Appleyard, is a coward. Nonetheless, with Valance on the prowl and the sheriff a lazy oaf, the town is caught in a limbo between wilderness and garden, between lawlessness and law-governed civilization.

This is precisely the type of tension-between-opposites that the entire film revolves around, particularly when it comes to the Old West's difficult transition to a modern democracy as an ordered system of rights and liberties. As Robert Pippin has demonstrated in his enlightening study Hollywood Westerns and American Myth: The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy, there is much that we can learn here from Liberty Valance (and others like it, such as The Searchers and Red River). These movies instruct us in the nature of legal authority, the significance of passions and desires in individuals' public lives, the idea of the state's legitimate exercise of violence in maintaining justice, the roles of heroism and mythmaking in a democratic society, and the ways in which human beings are either suited or not suited to the political structures that help to govern their lives.21 Above all, Liberty Valance presents an implicit argument that public and private happiness cannot be easily divorced, and that the old order of primitive justice, despite being transcended in large part by the new order of a rights-based democratic republic, is nonetheless retained to some degree in modern society's continuing need to satisfy personal vengeance in terms of state-sanctioned violence.

Stoddard has talked to the newspapermen for some time but cuts off his visit to join Hallie and Link on their return. The Stoddards walk slowly through a back alley to the undertaker's, Link tenderly carrying the hatbox as he limps along after them. Through a carpentry shop, past a dusty stagecoach inside it, they reach a tiny room filled with a plain wooden coffin. There is barely enough space for a bench, and on it sits the stooped, white-haired Pompey (Woody Strode), friend and servant of the deceased, who sheds tears when Hallie takes his hand. We are trembling now with the desire to know who lies in the pine box, but we are not about to see him. We will find out soon enough. The senator looks into the coffin and is shocked to find that there are no boots, spurs, or gun belt on Doniphon's corpse. Link explains that Tom had not carried a handgun for years. Here movie mythology takes over, for this is not a role in a play or an opera that could be performed by any number of well-known artists: we are talking about John Wayne. For Wayne's westerner to be lying in a coffin at the start of the film is so unexpected that we are reluctant to believe it.

The gentlemen of the Shinbone Star are wondering the same thing: Who is Tom Doniphon? Why did the senator and his wife come all this way for the funeral of a man completely unknown to them, nowhere mentioned in their newspaper records? The editor refuses to leave them alone, claiming that the readers of his statewide circulation have a right to know and that he has a right to have the story. Here, the editor defends a right to public knowledge, and the movie is in many ways about the rights of individuals and the liberties to which those rights lay claim, the same rights that are at the core of the development of democracy and civilization in the Old West. Stoddard looks to his wife for permission and she nods. Stoddard and the newsmen retreat to the carpentry shop where they will talk in front of the stagecoach, an old relic that has been stored there. A quick cut to a tearful Hallie shows her taking the hatbox, which contains the cactus rose that Link had retrieved for her, and starting to open it. This is the last we will see of the little room with its coffin for some time. The flashback, the narrative heart of the film, is about to begin. Assuming a senatorial posture in the carpentry shop, Stoddard says that the story concerns not only him but also Pompey and Link. He wipes the dust off the stagecoach and claims it is most likely the same one that brought him to Shinbone. He sets the tone for the flashback as he claps the dust off his hands. The flashback opens on the robbery of the stage with a terse request from Liberty Valance: “Stand and deliver!”

The distinction between truth and legend becomes the subject of this return into the past. Ford and his screenwriters, James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck, concentrate our attention on the ironies that accompany such broad progress, on such a passage from frontier wilderness to justice and order through the imposition of law. We see little wandering through the Western landscape, for the flashback is a journey through time alone, within a precise, fixed space, rather than through time and space as in The Searchers. In that earlier film, the Southwest, central to Ford's other Westerns set in Monument Valley, was only one of the locations Ford used to create the long journey of Ethan Edwards. We see less freedom for the protagonists in Liberty Valance; their interweaving conflicts are confined within a small moral universe, their destinies determined amid the cramped or tightly framed spaces of the under-dressed sets.

Liberty Valance is a Western without a regular glimpse of the landscape, unlike many of the classic Westerns, including Ford's The Searchers and Peckinpah's Ride the High Country, the other great American Western released in 1962. The only examples of natural beauty we see in the flashback are the cactus rose, a symbol of the wilderness before it becomes a garden, and the plain ranch of Tom Doniphon. There is no escape and chase through canyon and desert. Since many of the scenes occur indoors, Liberty Valance emerges as a Western drama acted as if on a stage—part mystery, part Shakespearean tragedy, part morality play, characterized by rich dialogue and reflective silence, without the robust physical activity we have come to expect of the genre. Neither the landscape nor extended fights with fists or guns will distract us from the encircling, mournful contemplation of perception and truth. Liberty Valance has been accused of being studio-bound, claustrophobic, and visually dull or downright ugly. Nothing seems more deliberate about the film, however, than Ford's choice to shoot in black and white, at the Paramount studio.

The film has the look of Ford's earliest Westerns of the second decade of the twentieth century, such as Straight Shooting, which was Ford's original intention.22 And even from the late 1930s forward— when color cinematography was first thought preferable, and the camerawork in Ford's productions would be equally stunning in color or black and white—he filmed some of his most meaningful Westerns in black and white: Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, Fort Apache, Rio Grande, and Wagon Master.23 Budgetary constraints, including the producers' possible refusal to spend money on Technicolor, may have influenced or dictated the decision to shoot in black and white. But Ford also explained that the scene of Liberty Valance's death, featuring the showdown between Stoddard and Valance in the shadowy confines of Shinbone's main street, would have never worked in color. In addition, Ford later claimed a personal aesthetic preference. He told Peter Bogdanovich, “Black and white is pretty tough—you've got to know your job and be very careful to lay your shadows properly and get the perspective right…. For a good dramatic story, though, I much prefer to work in black and white; you'll probably say I'm old-fashioned, but black and white is real photography.”24

We are not prepared for a Rashomon-like structure, and we do not anticipate that we will see and hear another flashback within the principal flashback. But the closeness and crowdedness of the scenes keep us uncomfortable as the film edges us toward each protagonist's reversal of fortune. Nothing is going to turn out the way we might hope from seeing the flashback's key early scenes in the kitchen of Peter's Place, the town's leading restaurant. The personalities of the four protagonists are sharply drawn: Valance is the most-feared gunslinger of the territory; Doniphon is one of its best-fiked and most-respected ranchers; Stoddard is a naive, stubborn idealist, “duly licensed by the territory” to practice law; and Hallie is lovely but unsure of herself and her admirers. Stoddard's character is pegged instantly by the two westerners: Valance calls him “Dude” when he encounters Stoddard's resistance during the robbery, and Doniphon later dubs him “Pilgrim.” Dude refers to a person from an urban environment, an easterner who has arrived in the West and is presumed to be inexperienced. Pilgrim indicates a person who journeys in an alien land, a wayfarer who travels to a given destination, often a shrine or holy place; it can also denote a stray steer, as well as a newcomer to a given region.

Early on, Tom Doniphon shifts from the foreground to the side, and back to stage front again when he wants Hallie's attention. After bringing Stoddard to Peter's Place, where Hallie works as a waitress, Doniphon notices her sympathy for the badly wounded man, who would have died had Doniphon not found him and brought him into town. Tom tells Stoddard that he can use Doniphon's credit at the restaurant until he gets back on his feet. But Stoddard wants to arrest Valance, put him in jail, and Doniphon replies that if that is what he has to do, he had better start carrying a gun. Tom follows this up with his succinct encapsulation of the code of the West: “I know those law books mean a lot to you, but not out here. Out here a man settles his own problems.” Ranse is appalled and compares Doniphon to Valance, asking what kind of a community he has come to if law and order do not prevail. We might recall here Wyatt Earp's similar question, early in Ford's My Darling Clementine, after he arrives in a wild Tombstone: “What kind of town is this?” Ranse tries to continue but collapses, and Hallie angrily declares that a little law and order would not hurt the town. We then witness the arrival of “Mr. Law and Order himself,” Link Appleyard, the clownish marshal who enters the kitchen for breakfast, only to learn from Ranse that he should put Valance in jail. Doniphon begins to mock them and to tease Hallie, drinking his coffee and smoking a cigarette, genuinely enjoying himself and his role as a passive observer. Tom calls Stoddard a “tenderfoot,” declaring that Valance is the “toughest man south of the Picketwire, next to [him].”25

FIGURE 42. John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962): Hallie (Vera Miles, center) assists the wounded Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart, lying), as Pompey (Woody Strode, far left) and Tom Doniphon (John Wayne, second to left) look on. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Next comes one of the great confrontation scenes in all of Western cinema. We have been waiting for the moment when Doniphon and Valance will face off, and Ford certainly delivers the goods but denies us an actual gunfight. Intriguingly, this memorable confrontation between our two gunslingers occurs in one of the most domestic of places: Pete's Place. Westerners have large appetites, and the restaurant is already mobbed on Saturday night before the town drunks come to dine. Enter the Shinbone Star's founding editor, Dutton Peabody (Edmond O'Brien), the intellectual drunkard who lectures Hallie about the proprieties concerning the cutlery. Peabody is the quintessential Fordian philosopher, the educated man who, despite his weakness for the bottle, is at the moral center of the story; he may fail or he may succeed, but alcohol never dims his intelligence. Such a character was incarnated as Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) in Stagecoach and, in part, as Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) in My Darling Clementine.

In the kitchen, Stoddard concentrates more on his law book than on washing the dishes, a chore that he does in exchange for his meals. His wet hands cause him to ask Hallie to read the passage he discovered that will put Valance exactly where he needs him (legally speaking, that is). Reluctantly, Hallie admits that she cannot read or write and cries in frustration. He apologizes and offers to teach her, but she asks him what reading and writing has done for him, since he stands there looking foolish in an apron. But Hallie then smiles at Stoddard's reassurance that she can learn quickly: it is her first moment of real happiness in the film.

Doniphon suddenly enters the kitchen, spruced up and ready to go a-courtin'. He has brought Hallie a cutting from the cactus rose bush in bloom at his ranch, and she thanks him, a bit flustered. While Pompey plants it for her in the backyard behind the restaurant's kitchen, Doniphon spots Stoddard's shingle hanging near the door: “Ransom Stoddard, Attorney at Law.” He advises Ranse that if he posts such a sign in public he will have to “defend it with a gun.” We begin to wonder not merely whether Ransom should stick to his law books or pick up a gun, but also whether an ordered system of rights and liberties requires violence (or at least the threat of violence) to maintain and protect it from external challenges. Doniphon leaves the kitchen and enters the crowded dining room. He stops at Peabody's table, and in response to Peabody's inquiry about the seemingly impending engagement of Tom and Hallie, he tells the editor not to rush him. Tom's delay in asking Hallie is his biggest mistake, but he does not see it. As observant as Doniphon is about Stoddard, he is stubbornly obtuse about declaring himself to Hallie, preferring to court at a slow pace.

In the ensuing sequence Doniphon segues from commentator and insecure lover to heroic activist, reassuring us by taking charge during Valance's sudden appearance at the restaurant. He confronts Valance and protects Stoddard after Valance has tripped the “new waitress” (Stoddard), causing Tom's steak to fall to the floor. Tom demands that Valance pick up the steak and the long-awaited confrontation, thick with tension, ensues. Doniphon challenges Valance with his usual sardonic humor and restores order, with the help of the nearby Pompey and his rifle, so that the customers can get on with their meals. The film then takes an abrupt turn at this point, as if suddenly bringing to an end the first act of a play, for Ransom becomes enraged, berating Tom for always resorting to violence in resolving a dangerous situation.

Stoddard decides to stay in Shinbone without purchasing a pistol—at least for the time being. For the moment he opts to be a man of principle, even if it may eventually cost him his life. And thus the first act closes. We have reached a point of crisis in the impending tragedy, one that is at the core of the expansion of the West. Stoddard is convinced that he can bring the civilized East to the West if everyone will just do what he says. He believes that he will transform the West with his law books and his schooling of Shinbone's citizens, young and old. Anyone with a sense of film history realizes that James Stewart was the perfect choice to play this role of a man caught between his dedication to civic justice and his possible need to resort to violence, since we remember him not only as the gun-wary lawman of Destry Rides Again and as the idealistic senator in Capra's Mr. Smith Goes to Washington but also as the psychologically and morally complex protagonists in Mann's Westerns (e.g., Bend of the River, The Naked Spur, The Man From Laramie) and in Hitchcock's thrillers (e.g., Rear Window, Vertigo).

As the second act of the film opens, Stoddard pursues his new role as civilization builder, as a lawyer trying to drum up business. Working out of Peabody's office, he supports the editor's defense of homesteaders who want statehood. From this point on, Liberty Valance interweaves the larger political story of the settlement of the West with the narrative of the restless trio of Doniphon, Stoddard, and Valance. They are headed toward a showdown of their own desires and grievances. Shinbone is a growing community in a territory that seeks statehood and thereby civilization, but Doniphon wants no part of it. Ever the individual, he cares about his ranch and about finishing the new room in his house so that Hallie and he can marry and start a family. He stays to the side, but he is watching every move, and we begin to feel that he is the only one who understands the truth, the reality of the way it is. His methods, however, are clumsy and brutal, at least to Hallie. When he takes Pompey away from the school Stoddard has set up, his blunt talk of the dangers of Valance frightens Stoddard into shutting the school. Furious with Tom, Hallie turns away from him—forever, as we will learn. And Stoddard, as we soon realize, begins to wonder whether Tom may not be right after all.

Westerns may be ambivalent in siding with ranchers or homesteaders, for they often deal with the settling of the Great Plains by cattlemen who prepare the way for the farmers and, eventually, towns and cities. Not all ranchers are land-grabbing villains, as Tom demonstrates, and the heroic progress they make is integral to the settlement of the West. Ford, whose Westerns typically embrace the inevitability of progress, likes to take a populist perspective and to defend “the little people.” Statehood will do the most good for the largest number of people, and Stoddard, the lawyer from back East, will be the most effective advocate for change. And so we soon witness a mass meeting for elections that is held at Hank's Saloon, and all is in disorder.

Doniphon bangs the meeting to order and proposes that Stoddard should run the meeting. As Stoddard explains, they are to elect two delegates who will represent them in the territorial convention for statehood. Ranse nominates Tom, but after the rousing applause dies down, Doniphon refuses the nomination—because he has other plans, personal plans.26 Valance enters at this point, and he sees the news report of his killings. He shoves people out of the way and asks the “hash-slinger” (Stoddard) why he is standing there looking so “high and mighty.” Doniphon, immediately assuming his role as protector, proclaims that Stoddard is running the meeting. Ransom is then nominated and Tom seconds it; Ranse accepts hesitatingly, a reluctant candidate.

Here again, Doniphon is required as the necessary “good bad man” who exists amid historical and political transition—as the threat of violence that is needed to secure the establishment of a democratic system of ordered freedom. Valance insists that he aims to be “the delegate from south of the Picketwire,” and his sidekick, Floyd, nominates him and moves that the nominations be closed. Doniphon restores order, saying they need two honest men, one of them being Stoddard. Valance's name is put down anyway, and then Peabody is nominated. Peabody comically protests, saying that he is a newspaperman and champion of the free press, not a politician. Stoddard and Peabody are elected, Valance is not, and Valance tells Stoddard that he has been hiding behind Doniphon for too long: “You got a choice, dishwasher: either you get out of town, or tonight you be out on that street alone. You be there, and don't make us come and get you.” Tom tells Ransom that come dark, Pompey will be there with a buckboard so that he can escape.

FIGURE 43. Tom Doniphon (center) calls a town meeting to order while newspaper editor Dutton Peabody (Edmond O'Brien, sitting to Doniphon's left) and lawyer Ransom Stoddard (standing to Doniphon's immediate right) look on. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

That night, a drunken, frightened Peabody—who earlier informed the surprised Hallie that Ranse had begun practicing with a borrowed pistol out in the countryside—notices a typographical error in his newspaper and, before trying to fix it, goes to the Mexican saloon to fill his jug. Back in Peabody's office, Valance and his men are waiting. The editor drunkenly returns and is forced to eat a copy of his own newspaper; he is also beaten with Liberty's trademark silver whip, and his files and type are destroyed. Leaving him for dead, Valance puts a newspaper over his face and then smashes the windows. After hearing the bullets, Stoddard rushes across the street from the restaurant to find Peabody brutally beaten but still alive.

Stoddard has been delaying his departure but now he decides to face Valance, looking genuinely heroic for the first time in the film. After seeing Peabody in such a pathetic state, he returns to the restaurant and retrieves his recently acquired gun from a carpetbag under his bed. Hallie runs to Pompey, who is waiting nearby, and tells him to get Doniphon. Stoddard walks out into the street, holding his gun, looks into the newspaper office and moves along in the shadows, waiting. Valance then exits the saloon, yelling, “Hash-slinger, you out here?” Stoddard and Valance walk toward each other, and Valance tells him to come closer where he can see him. Valance fires at a jug hanging by a hook, splattering its liquid on Stoddard, and then shoots the lawyer in his arm. Ranse's gun falls, and we watch Stoddard grab his bloody elbow and begin to move back to pick up his gun. Valance shoots at the gun and allows Stoddard to pick it up with his left hand: “All right, Dude, this time, right between the eyes.” Liberty aims his gun while the men are not far apart: each fires, but it is Valance who falls in the street, dead. Stoddard walks back into the kitchen, holding his arm, and collapses on the bed just as he did after the beating, dropping the gun before Hallie and her parents treat him tenderly.

Hallie looks at Stoddard and wraps his wound while crying; he looks back at her, knowing she is in love with him. The camera cuts to Doniphon in the doorway, who has seen and heard all, knowing now that he has lost his girl to Ranse. Tom tells Hallie indignantly that he will “be around” and slams the door on his way out. He lights a cigarette, walks past the saloon and Valance's body being taken away in a buckboard, and then begins drinking quickly at the bar. Valance's men, also in the saloon, talk of hanging Stoddard, and Doniphon easily subdues both of them. Pompey comes to take Tom home. “Home,” Tom says drunkenly. “Home sweet home. You're right, Pompey, we got plenty to do at home.” He drives home, yelling, and staggers from the buckboard, still drinking. He then runs into the house and lights a lamp, taking it into the new room he was building for Hallie and then smashing it. As the fire takes hold, he sits in a chair and Pompey rushes in, carrying him outside as the house and tree burn. This is the end of act 2.

There is no pause to introduce act 3, which explains the mystery and concludes the tragedy. Instead there is a quick cut to Capitol City and the convention. Major Cassius Starbuckle (John Carradine), a pompous blowhard, nominates a territorial representative to Congress, the right honorable Buck Langhorne, while Peabody nominates Stoddard. Pea-body's oratory is sharp and funny. He is fully a match for Starbuckle, eloquently and slyly talking of progress in the territory, beginning with the days of the “savage redskin,” people who were governed only by “the law of the tomahawk and the bow and arrow.” He speaks of “the westward march of our nation,” from the pioneers and buffalo hunters and greedy cattlemen to the railroads and the hardworking homesteaders and shopkeepers. He speaks of the need for someone to represent them in Congress, someone who can help them to build cities, dams, and roadways and to protect the rights of all. The editor nominates the “honorable” Ransom Stoddard, who has become known across the territory as “a great champion of law and order.”

FIGURE 44. The final showdown as depicted in a flashback-within-a-flashback: Doniphon (foreground left) has shot Valance (Lee Marvin, kneeling in background left) as Stoddard (background center) stands wounded. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The farmers cheer, the cattlemen boo, and Starbuckle takes his turn. While he carries on, claiming that Stoddard's only claim to fame is that he killed a man and now bears the mark of Cain, a dusty-jacketed Doniphon bursts through the swinging doors and sits on the lobby stairs, dirt-smudged and mean-looking, smoking and getting angry. When Stoddard leaves the hall in disgust at his own reputation as a killer, Doniphon follows him and asks him where he is going. Stoddard replies that he is going home, back East where he belongs, since he hardly wants to build a life on such a reputation. “You talk too much, think too much,” Doniphon proclaims as he strikes another match, and we see him in the light, with a scraggly beard and bleary eyes. “Besides, you didn't kill Liberty Valance…Think back, Pilgrim. Valance came out of the saloon. You were walking toward him when he fired his first shot. Remember?”

The entire movie thus far has indeed been a process of remembering, and here begins a flashback within a flashback. As the camera zooms in close and holds on Doniphon, he takes a deep drag from his cigarette and blows out smoke that elides the cut to the flashback within the flashback, the moment of truth. We have experienced the true climax of the film—not the shoot-out between Stoddard and Valance, but the “telling it true” by Doniphon. In a manner as blunt as his behavior throughout the film, and in pure Wayne-ese, Doniphon has let Stoddard have it. Doniphon killed Valance and Stoddard did not—he could not have done so, as he was not good enough with a gun, plus he was already wounded by Valance. Doniphon did it for Hallie, since she loved Ranse and wanted him alive. Tom sacrificed his own personal happiness for that of the woman he loved and kept his mouth shut about it. Stoddard could hardly be capable of such heroism himself.

As we watch, we feel much all at once. Doniphon's acknowledgment engages our sympathy for this twisted act of heroism. It is over for Tom, and we are devastated once again. We do not see Tom again. Unlike in the conclusion of The Searchers, there is no healing process, nor is there a last glimpse of Doniphon as there was of Bull Stanley in Ford's silent 3 Bad Men, riding with his pals in the sky: Liberty Valance offers no such flight of fancy. We learn from Pompey that Doniphon never used his gun again and from Link Appleyard that he never rebuilt his ranch. We know that he endured long, lonely years between his sacrifice and his death. It was Appleyard who wrote to the Stoddards to inform them of Doniphon's passing. Sadly there was no more contact between the Stoddards and Doniphon after the couple married and went to Washington.

The flashback over, Stoddard tells the newspapermen that they know the rest of the story. Shinbone's current newspaper editor (Carleton Young) tears up his notes. Stoddard asks him, “Well, you're not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?” The editor proclaims, in one of Hollywood's most famous lines: “No sir. This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.” This line is a crystallization of the Western's perennial tension between myth and reality, between realism and romanticism: a dialectic that underlies the genre as a whole. The train whistle blows and Stoddard looks at his watch, returning to the room with the coffin. He tells Hallie it is getting late and gives Pompey some spending money; as he leaves the little room, he turns to close the door and sees the cactus rose on top of the coffin. The camera closes in on the flowers, a recurring symbol of love and passion throughout Ford's oeuvre.27 Once we learn that Doniphon is the man who shot Liberty Valance, we understand that he is the subject of the film after all, its hero. After confessing his true story to the gentlemen of the press, Stoddard learns that they will not use it, and so Stoddard can safely return to Washington with his reputation intact.

We cannot safely return, however. In a coda, Liberty Valance quits us with meaningful realizations of the tragedy endured by these two aged people, who look back over their lives with such sorrow and reflect on the nation that the wilderness has become. During the train ride out of Shinbone, Ransom suggests that they return to the land Hallie so loves. As Ford scholar Joseph McBride has pointed out, the film and Ford pose the same question to their audience at this point: Are we proud of our American civilization and what has become of it?28 With such simplicity, Hallie lets Ranse know the truth, and he pauses before he asks her about the cactus rose on Tom's coffin, for he was too self-deluded to face the realization earlier. It is an awakening for him, a realization of what he has done to make the wilderness a garden—what he, and civilization, have done to the West, both positively and negatively—as well as what he has personally lost, or indeed never had.

The settlement of the West, for the American, has been the route in discovering a new destiny, replete with conflicts and contradictions. Ford was suspicious, too, of the new society of the Western frontier. From Stagecoach forward, Ford would deride the hypocrisy of the Law and Order League and the “blessings of civilization,” and he put populist views into the dialogue of his characters. Liberty Valance presents the uncertainties and ambiguities dear to Ford's own maturing interpretations of the West. That the new order is not necessarily better in all respects goes against the American grain, yet Ford's Westerns are distinguished by these partial regrets, which are themselves an amalgam of his and his screenwriters' reworking of fictional sources and expansionist history. These views characterized novels and stories on which Western films were based, as James Folsom tells us in his The American Western Novel: “The conflict in the Western novel, in its broadest terms, is an externalized debate which reflects the common American argument about the nature of, in modern parlance, the ‘good life.’…The American mental hesitation between the values of urban and rural life is mirrored in the Western novel; whether the coming of civilization is good or ill is the burden of Western fiction.”29

The “pilgrim” in Liberty Valance is on a mission, similar to the “errand into the wilderness” described by Perry Miller in the mid-1950s.30 If errand means “mission,” it also signifies wandering or losing one's way. Folsom points out: “Miller shows that quite early in the American experience both of these meanings come to inhere in the term. Whether in his errand into the wilderness the American has lost his way became the burden of Puritan sermons. It is the burden of much later American writing as well, not the least of which is the fictional writing about the West. For the West is unequivocally the wilderness, and it is there that the nature of the errand may best be seen.”31 The portrayal of the pilgrim as a wanderer is key to the Western film, as it is to Western literature, particularly in various Ford Westerns, from Straight Shooting through Fort Apache, from The Searchers to Liberty Valance. By focusing on the errand of Ransom Stoddard in Liberty Valance, we can grapple with the tragedy of Tom Doniphon in another way. He, too, was on an errand, and Hallie (as well as Ford) knows that both of her heroes have succeeded as much as both have wandered or lost their way. Doniphon is the greater hero because his loss was much the larger: he lost his one great love and, with it, the best part of his very soul.