CHAPTER 6

Howard Hawks and John Wayne

“Red River” and “El Dorado”

RED RIVER

Howard Hawks's greatest contribution to the art of the Western is Red River, which he produced and directed in a protracted period from 1946 through 1948. His three other major contributions to the genre are The Big Sky (1952), Rio Bravo (1959), and El Dorado (1967). Hawks had told stories about real heroes before, as in Viva Villa! (1934), Sergeant York (1941), The Dawn Patrol (1930), Air Force (1943), and Only Angels Have Wings (1939). But Red River was a major departure for Hawks as a storyteller of American culture. This time he focused on the expansion of the frontier, if not of the Western genre itself. In many ways it is his most ambitious film, certainly since His Girl Friday (1940). Red River was hugely successful at the box office, ranking number one when it was finally released in 1948 after many difficulties.

Hawks's first completed Western accompanied a number of visually and psychologically expressive Westerns released during the second half of the 1940s and in 1950: My Darling Clementine (Ford), Canyon Passage (Jacques Tourneur), and Duel in the Sun (King Vidor), all in 1946; Ramrod (André de Toth) and Pursued (Raoul Walsh) in 1947; Fort Apache and 3 Godfathers (both Ford) and Yellow Sky (Wellman) in 1948; She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (Ford) and I Shot Jesse James (Sam Fuller) in 1949; and in 1950, Broken Arrow (Delmer Daves), Rio Grande and Wagon Master (both Ford), The Gunfighter (Henry King), and The Furies and Winchester '73 (both Anthony Mann). These were the kinds of Westerns that tend to yield more thoughtful reflection by the viewer because they posit a more complex morality in which the good bad men (or bad good men) do not achieve easy resolutions, and in which the narratives avoid the clichés of stock villains and fierce Indians. (See chapter 7 for further exploration of the post-World War II Western.)

Red River is Hawks's first complete sound Western after Viva Villa! (1934) and The Outlaw (1943), neither of which he finished. Red River begins and ends outdoors; there are but half a dozen interior scenes in the entire movie.1 Most of Red River is set in and shaped by the vast open landscape of the trail. It is the story of Tom Dunson (John Wayne), Matthew Garth (Montgomery Clift), and their cattle drive from Texas to Kansas through tough terrain and inclement weather. As is usual in a Hawks film, where the director is as interested in the overall subject matter as in the interrelationships of the characters, much of the film is given over to depicting the process of the cattle drive. The script was adapted from the Borden Chase novel The Chisholm Trail, an epic story of a cattle empire's role in the expansion of the west. Chase's novel was serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in December 1946 and January 1947. Dunson's drive eventually takes the trail established in 1867 by Jesse Chisholm, which provided a shorter, more direct route north from Texas to the railroad that reaches as far west as Abilene, Kansas. The cowmen do not know this when the drive begins; they think they are going on a long trek to Missouri. But the choice of routes becomes the heart of the story and triggers the dramatic twist that takes the film along its darker, deeper narrative.

What makes Red River one of the most enduring of Westerns is the director's and his collaborators' achievement in balancing a story full of historical sweep. The narrative, replete with tensions between individualism and expansionism, concentrates all elements of the film within a broad, unending landscape. Red River does not actually follow the Chisholm Trail, nor was it even filmed in Texas and Kansas. Location shooting took place entirely in southern Arizona, not far from the Mexican border, on ranch land owned by C. H. Symington. The terrain, including the Whetstone Mountains and Apache Peak, offered a variety of landscapes, enabling the cast, crew, and fifteen hundred cows to work close to camp. The only set built was that of the streets of Abilene, while all the night and interior scenes were shot on Goldwyn Studio stages when the cast and crew returned to Hollywood.2 Even the dialogue between Dunson and his first love, Fen (Coleen Gray), was shot at the studio against a rear-projection screen. Todd McCarthy, in his biography Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood, notes that the “entire film is marked by this technique [of combining studio-created and on-location shots], something numerous other pictures, such as The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, were guilty of during this transitional period from traditional studio work to vastly increased location shooting.”3 Chris Nyby was brought in as editor, fresh from cutting Pursued for Walsh, to give shape to the episodes and to shorten the total footage. Dimitri Tiomkin, who had scored Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings, again composed a lush score, this time incorporating themes of Western and cowboy songs.

Among the choices made by directors of Western films at this time was the decision to shoot in color or black and white. Red River was shot in black and white, and McCarthy reports that “Hawks debated at length whether or not to shoot in color, as Selznick had done with his giant Western Duel in the Sun, but he felt that color film at that time still looked ‘garish' and was not as conducive to evoking a period look as black and white.”4 Hawks hired Russell Harlan as cinematographer; Harlan had shot black-and-white B-Westerns in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as Ramrod for André de Toth. He would later film Rio Bravo and El Dorado, both in color, for Hawks. Hawks may have preferred black and white to give consistency to the nighttime scenes—which start with a Comanche raid and include meals at camp around the chuck wagon—as well as to provide consistency with the indoor scenes, shot on a studio stage in contrast with the expansive scenes on the trail.

Once again the key chapters of a Western epic take place immediately after the Civil War. The Confederacy's defeat is acutely felt by Texans, and Dunson tells Garth, newly returned from the war, that the market for beef in the territory has collapsed. “The war took all the money out of the South,” says Dunson's longtime companion Groot (Walter Brennan). So after building the biggest cattle ranch in Texas, Dunson is now broke, and that is why he must take his (and any neighbor's) cattle a thousand miles to Missouri. Garth, the boy Dunson found fourteen years earlier and raised as his son, has spent the past four years fighting on the Southern side, where he polished his skill with a gun.

In Red River we have not one but two classic westerners: a good man gone wrong in Dunson, and a young good-hearted southerner in Garth. Dunson and Garth are natural leaders, respected and, in Dunson's case, increasingly feared. Garth is perceived as “soft,” with affectionate regard for Dunson and then Tess Millay (Joanne Dru); he must prove he has guts when it becomes clear he cannot run from the fight. Dunson is the most complex character in Red River and is splendidly realized by Wayne. Here Wayne plays Dunson at two ages, a man of his own years (at the start of production Wayne was thirty-nine) and a gray-haired man of middle age, fourteen years later, full of aches and pains after long days in the saddle. Equally successfully in 1949, Wayne starred as an army officer old enough to retire in Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon. Like other Hawksian heroes, including Cary Grant's Jeff Carter in Only Angels Have Wings (1939) and Humphrey Bogart's Steve Morgan in To Have and Have Not (1944), Dunson has a hard time expressing love, in this case for Garth. But we are never in doubt about this love, and this makes the film's climax somewhat puzzling, as we will see.

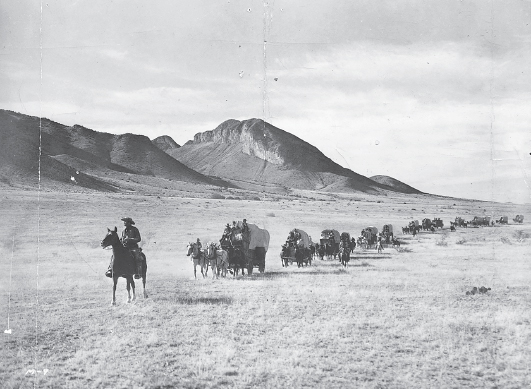

FIGURE 25. A procession of covered wagons is dwarfed by the vast landscape in Howard Hawks's Red River (1948). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Stubborn and willful, Dunson loses his first great love, Fen, in the film's opening scene on the trail. Because he doubts that she is strong enough to ride with him and then to help build his ranch, he rejects her desperate plea to go with him, and she stays with the wagon train that is massacred by Comanche just hours later. She seems capable enough to us, as well as beautiful and passionate, which makes her loss the more deeply felt. “That's too bad,” Groot says when he and Dunson see the far-off smoke of the burning wagons. That night they prepare for an attack by the same Comanche, whom they dispatch easily with knife and gun. Dunson finds on a brave's wrist his mother's bracelet, which he had given Fen in parting and which confirms her death; he in turn will give it to young Garth, who fourteen years later will put it on the arm of Tess Millay. Tess is strikingly similar to Fen in beauty and outspokenness.

The dialogue between Fen and Dunson at the outset establishes their characters in the straightforward but suggestive manner we expect from Hawks. Fen is tender and more sexually alive than Tess is in the latter's later exchanges with Garth. Dunson has just told the leader of the wagon train that he is going his own way, and he turns to embrace Fen, making his departure from her certain, despite her protests. Red River thus opens with the protagonist's mistake, the biggest of his life. Like Fen, Garth and Groot love Tom but must tell him when he is wrong.

Dunson is not a typical good bad man like Hart's Blaze Tracy (Hell's Hinges), Santschi's Bull Stanley (3 Bad Men), or Wayne's Ringo Kid (Stagecoach)—men on the other side of the law who are redeemed by their love for, and subsequent devotion to, women of strength and character (see chapters 1 and 4). By contrast, Dunson, in his determination to be a successful rancher at any cost whatsoever, becomes a tyrannical “bad” man. As Hawks once noted, Dunson's rejection of the woman who could have softened and civilized him “would make him all the more anxious to go through with his plans. Because a man who has made a great mistake to get somewhere is not going to stop at small things.”5 Dunson hates weakness, complaining to Garth later in the film: “You're soft, Matt.” Yet Dunson raised Garth as his son. This is the contradiction of character essential to the Western, as the film narrative retains the men's love for one another despite Dunson's later fury. In the novel as well as the film, Dunson's affection for Garth dissolves into hatred and then into an attempt to kill the son who took away his cattle and his pride.

In his essay “Beyond the River: Women and the Role of the Feminine in Howard Hawks's Red River,” John Parris Springer analyzes the characters of Dunson and Garth in terms of gender—specifically the masculine and feminine qualities that play a role in their respective personalities—and the underlying “homoerotic subtext” occasioned by the deep love that the two men share. Springer argues that, despite the strength and determination shown by the characters of Fen and Tess, Hawks focuses almost entirely on the men's “love story,” especially in terms of each man's need to develop the psychological characteristics that are dominant in the other man. According to this interpretation, Dunson and Garth come to recognize through each other the traits that each lacks. As Springer tells us:

The homoerotic subtext is quite strong in many of Hawks's films, which often deal openly with what Hawks himself called “a love story between two men.” Here the devotion to profession and loyalty to an elite group of male comrades who practice a way of life defined by constant danger and the threat of death create a strong, often physical bond between the characters that can be seen either as a heroic, existential link between men or as macho posturing of the rankest sort. But in Red River Matt Garth functions as an alternative to Tom Dunson's stern masculine ethos, and he becomes the embodiment of “feminine” characteristics and values that are most apparent in his more compassionate and humane treatment of the men on the cattle drive.6

Garth comes into the story the morning after the Comanche attack. Dunson and Groot hear the mutterings of a young boy who is out of his senses from witnessing the horrors of the massacre. He stumbles along leading a cow until Dunson slaps the youngster to bring him about and takes his cow and gun. “But don't ever try to take it [the pistol] away from me again,” the boys warns. Dunson turns to Groot: “He'll do.” Later, after crossing the Red River into Texas, Dunson decides that he has found the land he has been seeking. With everything a man could want—plenty of good water and grass—he will establish the greatest ranching empire in all of Texas. He draws a brand in the soil: two lines like the banks of a river along with the letter D.

As they start to brand his bull and Garth's cow—“I'll put an M on it when you earn it,” Dunson tells him—two Spanish riders come along, attracted by the smoke of the fire. The land is Don Diego's, they say, and reaches far south some four hundred miles, beyond the Rio Grande. Dunson declares that the land is his and orders them to tell Don Diego that all the land north of the Rio Grande belongs to Dunson, especially since Don Diego probably took it away from someone else. One of the riders is unwise enough to go for his gun and is shot dead by Dunson. “He went for his gun first,” says Garth, as if to reassure himself as well as the viewer, but it is a questionable moment that never leaves us feeling quite comfortable about Dunson's later worries over being broke and stuck with too many cattle. Dunson tells the surviving rider to bury the dead Spaniard and he will “read over him” from the Bible. This happens each time Dunson kills somebody, until his employee Simms (Hank Worden) later points out to us the irony of this ritual, in case we might not get it: “Plantin' and readin', plantin' and readin'. Fill a man full o' lead, stick him in the ground, and then read words over him. Why, when you killed a man, why try to read the Lord in as a partner on the job?”

Red River's dialogue usually clues us in just before or just after a twist or turn so that we will not be left behind. Surprisingly for such a visually engaging, expressive landscape film, Red River relies on verbal explanation almost as a silent movie typically depends on intertitles. Two versions of the film were released: one with text, the other with voice-over narration. In the “book,” or diary, version, the film cuts all too often to pages of a handwritten text that tell us what is going on every ten days or so on the drive, particularly noting the changes in Dunson's demeanor as he becomes a tyrant. We know he can kill easily, and he does, punishing without compunction anyone who stands in his way. And, guided by the text, we know he will go too far one day, the day of his undoing. No doubt the explanatory passages of the text were thought to be necessary to bind together the episodic wanderings of the story. Curiously, the early editing and postproduction of the two versions of Red River were completed with little input or supervision from the director. The earlier “book” version is longer than the other version, which has, instead of the text, a voice-over narration by Groot along with a briefer conclusion.7

In terms of dialogue, Hawks's characters frequently antagonize each other with humorous jabs to disguise their mutual attraction. The relief of these exchanges in Red River and Hawks's other adventure films differs importantly from the humor of his screwball and later comedies. From Twentieth Century (1934) through Bringing Up Baby (1938), His Girl Friday, and I Was a Male War Bride (1949), Hawks pits one sex against the other. The plots consist of attempts to humiliate and frustrate the objects of desire, to hilarious effect; the rapport and sexual gratification come with the clinch, at the end. Only Angels Have Wings, To Have and Have Not, and Red River are as much about affectionate relationships between male comrades as they are about romances between male and female protagonists. This is especially true of the three finest films of his later career, in the 1950s and 1960s, and all are Westerns: The Big Sky, Rio Bravo, and El Dorado. The camaraderie is there from the start or develops quickly, for it is a necessary point of departure for Hawks. The broad comedy in these films deepens and strengthens the depiction of courage and the stoic endurance of hardships. In the earlier struggles of Red River, such comedy serves to offset, in a compensatory way, the growing anger and fear, the enmity forming between the boss and his crew.

Red River has been called a Western version of Mutiny on the Bounty, in which the men of the former are bound to the desert and plains as much as sailors are confined on a ship, and their leader is as single-minded and ruthless as Captain Bligh. Mutiny is inevitable. But the comparison is not entirely apt: Red River's concerns are not cruelty and punishment and isolation, but rather hard work and maturity and accomplishment. Dunson does not start the drive as a man removed, aloof, rigid—qualities that earned Bligh high marks by the Royal Navy—but rather as a man facing his last chance, desperate to survive. Dunson is ruthless, and we witness the manner in which he claims his land. But this is smoothed over as he brands his bull and Garth's cow to start the herd, telling the young Garth about his dream—an idealistic, quintessentially American dream, one that any corporate leader would admire: “Ten years and I'll have the ‘Red River D' on more cattle than you've looked at anywhere. I'll have that brand on enough beef to feed the whole country—good beef, for hungry people, beef to make ‘em strong, to make ‘em grow. But it takes work, it takes sweat, it takes time, lots of time, it takes years.”

As Dunson conveys his dream of establishing a cattle empire, we see a vision of the ranch and the vast herds. Then we cut to fourteen years later and a gray-haired Dunson explains to a grown-up Garth what happened while Garth was off fighting in the war. As Dunson organizes the drive, it is clear that he is a boss who is admired and respected by his men and his fellow ranchers. And although Dunson subsequently loses the respect of his men and becomes feared for punishing them excessively during the long drive, Garth never ceases to love him, and it is his love that enables them both to survive.

While the relationship between the two men is certainly the emotional axis of the movie, Dunson's obsessive desire to establish an empire gives the narrative its metapersonal backdrop and ties it to the expansionist ideal that is central to the story of America. As Springer observes, “From the very beginning of Red River, with its framing device of the expository titles and the manuscript called ‘Early Tales of Texas,’ Hawks announces a much larger historical and cultural frame for this film than is typical of his work…. Clearly, this is a theme with social and political implications.”8 And in his book Cowboys as Cold Warriors: The Western and U.S. History, Stanley Corkin argues that Red River, like Ford's My Darling Clementine, should be understood not merely in terms of the wider context of empire-building in the nineteenth-century Old West but also in terms of the parallel context of America's Cold War ideology—especially given that these Westerns were released right after the start of this period in U.S. foreign policy. Beginning right after the Allied victory in World War II, the anti-Communist agenda was anchored by a deep conviction in “American exceptionalism” and by a firm opposition to any possible threats to our democratic and capitalist system. One can indeed make the case that certain Cold-War-era Westerns express the prodemocratic ideals and procapitalist values that are central to the evolving view of America as a “shining city” or “city on a hill.”9 Corkin summarizes his interpretation:

In Red River and My Darling Clementine, we view the economic outcomes that should emerge from the effective assertion and visceral acceptance of the core terms of national identity. In Red River, heroes emerge and perform their morally desirable actions, and, as a result, the cattle industry is born; in My Darling Clementine, Tombstone becomes a place where an entrepreneur need not fear the forces of chaos…. These economic goals are mystified by their association with character traits that resonate within the national mythos. At their most explicit level, both films are character driven and focus on the power of the (male) individual to bend conditions to his will by exercising the prerogatives of freedom; thus, we can boil down much of the ideological thrust of these presentations to the powerful terms ‘freedom’ and ‘individualism,’ which, not coincidentally, are the focal terms of [Frederick Jackson] Turner's essay [“The Significance of the Frontier in American History”].10

It is natural, at first glance, to think of Red River as a movie that expresses core principles of American ideology and idealism—not merely because of its themes of empire, frontier, and individual ambition, but also given the fact that this is a John Wayne film. As William Beard reminds us, Wayne's iconic screen persona has been associated with the ideas of American exceptionalism and individualism in the minds of many viewers over the course of his career, and most especially in his war and Western movies: “Wayne's power sustains the dominant ideology but is also derived from it.”11 And as Corkin further tells us, “In ways that are fairly typical of the genre, My Darling Clementine and Red River present the annexation of western lands as a matter of inevitability. Specifically, the question they present is how parts of Arizona and Texas will be integrated into the national fabric, not whether they will be or whether they should be.”12

Yet despite Corkin's illuminating comparisons between nineteenth-and twentieth-century forms of American idealism and expansionism, there are certain limits that must be drawn here. This is especially the case with Hawks's film, in which Dunson's obsessive determination and excessive ruthlessness in his pursuit of empire-building brings about the near-collapse of his cattle drive team, a severed relationship with his own “son” (Garth), and his own subsequent exile from and revenge against those who had once served him so faithfully. One chief problem is that, while Dunson clearly embodies the ideals and values around which Corkin's analysis revolves, he is also a seriously flawed and narrow-minded figure, as the movie demonstrates. If anything, Dunson's unquestioning dedication to his mission makes him less democratic, in that he rarely listens to his men (even Garth and Groot are typically ignored). It is Garth who elicits the opinions of his fellow drovers and who relies on consensus in pushing the team ahead. Once Dunson, however, has garnered sworn oaths from his men, oaths to complete the cattle drive no matter what obstacles may lie ahead, he becomes purely autocratic.

If there is a lesson to be drawn from the film, it is that blind adherence to such a mission is personally destructive, and that humane values should never be forsaken—values that are expressed by Garth, not Dunson. At the end of the day, Dunson's individuality and the freedom that he needs to forge his empire are not shown to be intrinsically preferable to the collective interests of his men. Red River is not so much the expression of a prodemocratic, procapitalist ideology as it is a warning signal about the dangers involved for those who do not recognize the limits of such an ideology. The movie emphasizes the consequences of an idealistic ambition that forsakes its roots in a common humanity.

Patrick McGee, in his book From Shane to Kill Bill: Re-thinking the Western, critiques Corkin's interpretation for precisely these reasons. According to McGee, Red River demonstrates the contradictions that can emerge when democracy and capitalism do not easily blend—and this is shown especially in terms of the conflict between Dunson and Garth. The film is not simply a cinematic embodiment of American ideals, as Corkin might have us believe, but is rather a dramatized lesson about the possible consequences when our adherence to these ideals are pushed to the extreme. In fact, when relating the film to the anti-Communist efforts taking place in Hollywood around the time of its release—efforts involving the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, of which John Wayne served as president, succeeding Ward Bond—McGee suggests that Red River, the movie that “almost single-handedly invented the myth of John Wayne,” also put into question the kind of oppressive ideology and patriarchal authoritarianism that Wayne willingly represented in his political life around that time.13 The film does so, not merely by pointing to Dunson's increasing tyranny over his men, but by showing that Dunson has very little regard for private property (as when he takes Don Diego's land and seizes others' cattle by force) and that he has grown his cattle herd beyond the demands of his local market, thus producing an “economic crisis” for himself.14

As McGee states in regard to the problems and limits of Corkin's interpretation, particularly when one looks beyond Dunson's determined empire-building: “Corkin argues that the conflict between Dunson and Garth is ultimately nothing more than a clash over ‘management theory.’…Though this thesis has a good deal of merit…there is a tendency toward reduction in Corkin's reading of these Westerns [like Red River] that ignores or downplays those elements that point toward contradiction rather than the pure expression of nationalist ideology.”15

To take but one example of the tension that grows along the drive, there is the stunning scene of the cattle stampede. On a night when the cattle are especially restless, a cowhand (Buck Kenneally) tries to steal sugar from the chuck wagon and knocks over pots and pans, triggering a stampede. There follows an exciting sequence, terrifying in the sweep and swiftness of the panicked herd. We see the faces of the cowboys, just as we did at the start of the drive, as they grab their saddles and race to do their jobs. This sequence was the work of the assistant director, Arthur Rosson, who supervised most of the film's action sequences with the herds.16 The stampede takes place at night, with a stream of cattle flowing through the camp, across the grassland, up and over a rise, and down into a draw, all below a cloud-streaked sky. At times the camera is set low, at the level of the stampeding cattle or even in a hole in the ground to catch the steers running overhead. Medium shots bring us close to the riders and the herd. The stampede follows its course, in tracking shots that keep pace with the movement of the herd. Then the camera is placed on a rise, front and center, to film the steers racing below and up toward us, passing by to the right. We are never far from the stampede: we see it up close, almost as close as the cowboy stunt men, and we feel intimately involved with it. The sequence is marred only by the artificial-looking process shots showing the stampede in rear projection behind Garth and Dunson.

The young and sympathetic Dan Latimer (Harry Carey Jr.) is killed during the stampede. “We'll bury him, and I'll read over him in the morning,” Dunson declares, instructing Garth to pay Latimer's widow his wages for the entire drive. Again we hear the familiar words from the Bible, delivered always beside a grave set back on a rise or slope, at a respectful distance from us. Dunson then grabs a whip to punish the sugar-stealing cowboy, and Garth quickly intervenes. By now we know that whenever Garth tries to treat the men decently, he must confront Dun-son. Dunson soon goes for his pistol but Garth outdraws him, wounding the cowhand so as to keep him from being killed outright, and says to Dunson: “You would have shot him right between the eyes.” “Just as sure as you're standing there,” Dunson confirms, and then barks to Groot: “Go ahead, say it.” Groot replies firmly and predictably: “You was wrong, Mr. Dunson.”

As Groot, Walter Brennan joined Hawks's cast for the fourth time, following Barbary Coast (1935), Sergeant York (1941), and To Have and Have Not (1944). A veteran of Westerns, he had acted in dozens of oaters before receiving an Academy Award as Best Supporting Actor for his interpretation of Judge Roy Bean in Wyler's The Westerner (see chapter 5), and he was notable as Pa Clanton in Ford's My Darling Clementine (see chapter 7). Brennan's first Western for Hawks was Red River; his second and last would be Rio Bravo in 1959. His performance as the physically impaired and loyal but critical older friend of Dunson is key to the Hawksian comic tone. In Red River he sets this tone in the opening scene when he explains why he is quitting the wagon train to accompany his friend: “Me and Dunson—well, it's me and Dunson.” No other explanation is necessary. Groot loses his “store-bought teeth” to Quo (Chief Yowlatchie) in a poker game the night before the start of the drive; his Cherokee friend, having won a half-interest in them, decides to give Groot his teeth only at mealtimes. The joke is carried throughout the film; Groot's mumbling caused by his lack of teeth irritates Dunson, who makes him repeat, slowly and defiantly, his opinions and criticisms. Groot talks to himself about the problem of keeping dust out of his toothless mouth: “Bet I et ten pounds in the last sixteen days. ‘Fore this shenanigan's over I'll probably et enough land to incorporate me into the union, the state of Groot.”

The Texas landscape is unforgiving: it goes on and on, and the drive lasts month after month, before the men and cattle reach the Red River, the northern border of Texas that Dunson and Garth crossed fourteen years earlier. The trail is dry and full of dust, or the rain is hard, and the men are exhausted. A cowboy rides into camp, having barely survived a Missouri border raid. He reports that his outfit should have turned north at the Big Red because an Indian trader, Jess Chisholm, told him that he blazed a trail clear to Kansas. He even reports that there was a railroad there, at Abilene. He has not seen it himself, though, and Dunson will not risk diverting to a possibly shorter trail on hearsay alone. Three cowhands then tell Dunson that they have had enough, and they are soon dead. They were quitters: “not good enough,” says Dunson, who will tolerate no more disobedience or opposition. He reminds the other men that, since they signed on, they have to finish the drive. But he is jumpy, and the men see it.

FIGURE 26. Cattle drive meets “iron horse” in Red River. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Dunson is now alone, and as the men turn from him, there is a subtle shift: we become slightly and problematically sympathetic for the hardships he has endured. Although we are supposed to feel the men's fear of Dunson, it is not easy to dismiss their nervous and vulnerable leader without empathy. That night, three more cowboys rebel and leave the drive. Dunson sends Cherry Valance (John Ireland) to bring them back and the mood shifts again, with the herd moving slowly along toward us and away from low hills. Under a magnificent Western sky and to the rhythm of the Tiomkin score, the Red River is reached at last. As the cows sweep down to the river, the theme of the cowboy song “My Rifle, My Pony, and Me” mixes with the principal music theme (and will be sung to great effect by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson in Hawks's later Rio Bravo). During a pause at the riverbank, Garth and Dunson share their last peaceful moment together; he says that the crossing will keep the men worn out (and therefore less likely to rebel against him) until Cherry gets back. The movement of the herd through the river is depicted with Hawksian calmness, the narrative drama pausing to let us watch and enjoy at a leisurely pace, providing the feeling of a lengthy and mighty task. Like the stampede, the men ably handle the crossing under Dunson's increasingly oppressive leadership; they still obey their trail boss.

It becomes clear, however, that Dunson intends to kill the men who ran away, and when Cherry brings back two of the three men, the most horrifying of Dunson's brutal moves is declared: he will not shoot but rather hang the deserters. For Garth, this is the limit; he cannot accept Dunson's judgment or carry out the punishment. He is the true rebel: he takes over the drive from Dunson, and he does it without firing a shot. Instead, Cherry shoots Dunson in the hand. This is the point of passage in the film: the emergence of Garth into manhood. The “son” has humiliated the “father” in front of the others, and so quickly is it done that Hawks must provide a moment to reflect on the loss of camaraderie and the severing of every bond. There is no turning back. Dunson stands by his horse, about to be left behind, and his fury is coldly put: “Every time you turn around, expect to see me, 'cause one time you'll turn around I'll be there. I'll kill you, Matt.”

This declaration by the trail boss who has become too brutal, too exhausted by his efforts, is calmly delivered by Wayne, surprisingly subtle in his ferocity. And it scares the hell out of Garth, quietly registered in Clift's expressive eyes and slight grimace. Dunson watches as his cattle and men leave, the sequence ending with a shot of the landscape. To the right is Dunson, his back to us, unable to stand erect, a wounded man left alone. It is an exceptionally beautiful moment and we hold on to it, for it is in this pause that we sense everything that this westerner has lost. Dunson is a man defeated, and his stance, his sagging physicality, conveys his tragedy, his second great loss after Fen. This time it is his friend (Groot), “son” (Garth), and cattle: all he possesses.

A big sunny sky sits over the cowboys and cattle for much of the rest of the drive. Flat-bottomed clouds familiar to the Western mountains and southwestern desert fill the screen above a low horizon. The cinematography of the landscape of the Red River and the country to the north, while actually the same Arizona terrain throughout the film, seems deeper and more tranquil as they approach Kansas. Garth can now make his own decisions, capably taking charge as his “father” has failed. He commits the drive to the shorter route to Abilene although he has no proof that the railroad has reached that far west; it is still only hearsay. But for the sake of his men, Garth is willing to take the risk, unlike Dunson. Along the way, the men dash into an Indian raid to save a wagon train (and there are a few dreadful moments, cinematically speaking, when we see the cowboys up close, riding their mechanical studio horses). Garth meets Tess Millay, who is hit by an arrow, and by the time Garth has pulled out the shaft and has sucked the poison from her shoulder, she seems to be in love with him. That foggy night she learns the story of Garth and Dunson from Cherry and Groot. When she finds Garth and snuggles with him for a spell, she tells him that she knows he loves Dunson.

A week later, Garth having now departed, Millay meets Dunson, gives him dinner and a couple of drinks, and asks about the woman he left behind. Dru is not a bad match for Wayne. She is given the mannerisms Hawks likes his women to use: a kind of loose sexiness in the movement of their arms, their hands clasping the tiny waists of their period costumes, their posture daring the men to try something. Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not, Angie Dickinson in Rio Bravo, and Charlene Holt in El Dorado are similarly provocative. Tess gets right to the point, startling Dunson in his remembrance of Fen as she talks of wanting Garth so much. Dunson has seen the bracelet on her wrist, the one he gave Fen fourteen years earlier. He lost the only woman he ever wanted, and all he desires now is a son. “I thought I had a son,” he complains. Then he offers her half of all he has if she will bear him a son, especially in looking ahead to the future of his planned empire, and also undoubtedly out of spite. She tells him she will do so, most likely as a ruse, if he promises to stop now, turn around, and go back. She begs him to take her along to Abilene. “Nothing you can say or do…,” he begins—but then he consents, no doubt remembering Fen, the woman he once left behind in a similar situation.

Gradually, during this last phase of the drive, we become less convinced of Dunson's threat, even as Garth and his men jump at every noise and calculate how many days it will be before Dunson catches up with them. The threat seems contrived if we listen carefully to the intimacy of the conversation between Millay and Dunson, and we cannot believe that either Clift, in his first starring role, or Wayne, forceful as ever, will die at the end of this tale. In fact, according to McCarthy's biography of Hawks, the climax had not been decided when production began. In Chase's novel, Dunson is wounded by Cherry Valance, whom he then kills, and Dunson is too weak to hold his aim on Garth. Chase concludes his novel with an epilogue in which Garth and Millay take Dunson home in a wagon, and when they cross the Red River he dies on Texan soil. Charles Schnee was brought in to revise Chase's narrative, and he made important changes and improvements, such as the introduction of Fen. It was Hawks, however, who no longer wanted to kill off sympathetic characters, as he did to Thomas Mitchell's Kid Dabb in Only Angels Have Wings.17

It would also seem odd, by Hollywood standards of the time, to allow a hero such as Garth to fall in love at this stage in the film and kill him off a few scenes later. The introduction of the romantic interest serves another purpose: it clues us into a change in mood and temper, a shifting away from violence and tragedy and an emergence of the Western's traditional view of the woman as an agent of civilization. Whether for a bad man trying to reform, like a Hart character, or a good man gone bad, like Dunson, it is never too late for a westerner to listen to a wise woman. Tess is not a new type of Hawksian heroine, but she sets the character mold (for Rio Bravo and El Dorado) of the card sharp who is very much a caring woman: strong-willed, talkative, and ready to fall in love at first sight. Like Bonnie Lee (Jean Arthur) in Only Angels Have Wings and Slim (Lauren Bacall) in To Have and Have Not, Tess does not hesitate to speak her mind and she is a forceful participant. The Hawksian woman is intelligent enough to figure out the man she loves pretty quickly and to tell him so in her own determined, sexy way. A critic of the stubbornness and wrongheadedness of the principal male character, she centers the film morally and acts as a civilizing influence. In early Westerns the female character tended to be a schoolmarm (even as recently as Ford's My Darling Clementine), and, in becoming a gambler, as Tess is, she has come a long way. In Chase's original story and in the script, Tess and her wagon train companions were prostitutes. The change from prostitute to gambler imposed by Joseph Breen's Production Code Office (along with numerous other script changes) seems absurd in the mid-1940s, since Claire Trevor was clearly a woman of the night in Stagecoach and Marlene Dietrich was a brash saloon singer in Destry Rides Again (both 1939).18

The drive, the first to take the Chisholm Trail, arrives in Abilene on August 14, 1865, and Garth quickly sells the herd to Melville (Harry Carey Sr. in one of his final performances), who represents the Greenwood Trading Company of Illinois. And so we come to the end of the four principal sequences depicting the movement of the cattle, scenes that mark the film's rhythm like the opening and closing of acts in a play. First, the launch of the cattle drive is joyous, sweeping us along in the excitement and anticipation of the cowboys. The stampede is the second sequence that calls on the cowboys' professional expertise; their skill, daring, and swift action, no matter how weary they are, prove the effectiveness of Dunson's leadership. The drive of the herd across the Red River is the next meaningful passage, not only marking the physical departure from Texas and Dunson's lands, but also psychologically reinforcing his relentlessness. Though men and cattle have passed into new territory, the trip is far from over. The final extended phase of the cattle drive, as the steers move slowly into Abilene, is relaxed and leisurely, the music track revving up the now familiar theme of this huge effort, accompanying the men on their last ride of the long trail and bringing the drive itself to its successful conclusion. The sequence would be a coda to the main theme, were it not for the cowboys' worry about Dunson showing up.

Typical of many Westerns, Red River's final scene takes place in the sunshine, on the main street of Abilene. But the crowding of the cattle onto the stage gives it a comic edge. The steers are carefully left in the streets the night before, since there are no pens large enough to hold even half as many. So there is an unusual moment of densely occupied landscape to enhance the effect of the ending. They are a tired bunch of steers after their long trek, and they are not about to be agitated by Dunson or a gunfight. The happy conclusion of the drive is undercut by the anticipated fight with Dunson, who is on his way with men and ammunition. Although Dunson reaches Abilene on the same night that Garth signs the contract, just a few hours after the cattle are brought into the town, the denouement is instead set in the early morning of the following day. Dun-son bursts forth in an extraordinary, purely Hawksian lead-in to the final scene: he rides into the herd, dismounts fast, and shoves the cattle aside as he strides purposely toward Matt. Nothing can stop him now. It may be the most thrilling sequence of strutting in the cinema: Wayne at his most physically imposing and the music enhancing the tension.

Wearing his black hat, Dunson makes his pigeon-toed strut through the herd and across the railroad track and starts shooting around and past Garth, who will not fire back. The crosscutting between increasing close-ups of their faces builds to a crescendo as Dunson strikes Garth with his fist. “You're soft,” he tells Garth. “Won't anything make a man out of you?” As the long-awaited fight begins, we look patiently for Garth to respond, which he soon does satisfactorily, despite being much smaller than Dunson. Dunson is knocked down by Garth's punch, to his surprise, and Groot gleefully tells Millay, “It's all right. For fourteen years I've been skeered, but it's gonna be all right.” And we know it, too. Then, after shooting a couple of bullets past Dunson and Garth, Tess keeps their attention with an angry speech about how killing each other is the last thing they would do; anyone would know the two love each other, she proclaims. Once again Hawks has a character explain more than is necessary. Millay nonetheless makes emphatic a happy ending: by surprising them, she provokes Dunson to say, “You'd better marry that girl, Matt.” Dunson soon draws the design of a cattle brand that will symbolize their new partnership. “You've earned it,” he adds affectionately.

Sudden moral transformations are typical of the genre, dating back to Griffith's Biograph oaters (see chapter 1), and we may accept Dun-son as a psychotic tyrant temporarily gone mad, eager to kill his men. Yet there are a few clues to his essential humanity. He is a man who has forged his way through the frontier and forced the landscape to bend to his will. When the land fought back, through drought and obstacles all along the drive, it cost him his strength and his sanity, not unlike what happened to Letty Mason in The Wind. But Dunson never quits, for Hawks created this Western as an illustration of movement forward, as the broken journey that must be completed.

Dunson's concluding shift in mood—his lightning-quick switch from ferocious avenger to affectionate father figure—is indeed jarring and does not seem to fit well with the foregoing. Tess's sudden act of mediating between the two “enemies” is supposed to help transition the viewer, even if overly quickly, from tragic to comic mode. As Springer observes about the peculiar emotional dynamic involved in the odd conclusion of the film: “It should be observed at this point that Millay's intervention in the conflict between Dunson and Matt and the comedic resolution that makes it possible (the film's ending in the promise of marriage) are clearly inappropriate in terms of the conventions of the Western genre, according to which one of the two men should be killed. Nor is this ending in any way commensurate with the depth of the conflict established between the two characters over the course of the film.”19

In looking back at the film, Hawks admitted that the ending was “rather corny”: “If we overdid it a little bit or went too far, well…I didn't know any other way to end it.”20 But Hawks, who with Red River had become thoroughly engaged in the Western genre, was not so much interested in a happy ending as he was in broadening and deepening his own humanistic approach, merging comedy and drama in new and more profound ways. The problems of the lengthy production, Hawks's first and last independent production, make it difficult to discern this shift, for many collaborators were involved here in script development, deletions and changes were imposed by the censorship office, the initial running time (which was considered too long, and the film required extensive editing) needed to be reduced, and the issue of two versions (the book and the voice-over narrative) had to be resolved. Hawks's efforts to mold the genre to his style and intent are nonetheless consistent within the body of his work.

Prior to Red River, Air Force and To Have and Have Not show the beginnings of a new direction for Hawks's films of action and adventure after the taut brilliance of Only Angels Have Wings. Until the end of his career he continued as a master of comedies, directing I Was a Male War Bride two years after Red River. But his great Westerns of the next two decades—The Big Sky, Rio Bravo, and El Dorado—are very much of a piece with various notions surfacing in Red River. (Rio Lobo of 1970, his last Western, is something of a disappointment when compared with these other films.) In these Westerns, as in Red River, the portraits of stubborn, strong men and women who are hard on each other because they love each other are enriched by acerbic, sympathetic commentary from friends and sidekicks. The secondary leads are, like Garth, pushed to their limits so that they will become the men the westerner wants them to be. Rich humor infuses the three later films, more so than in Red River, and the comedy is expressed directly and unsubtly. These later Westerns become not satires but comedies of the human spirit in which men have to make choices and often fail.

Hawks eases up on the killings and moves away from the slaughters that will mark a number of other Western films from the 1950s forward. No comic-book adventure stories for this director: his Westerns are character studies and we never tire of them. A good part of their appeal comes from observation and commentary by both sexes, whose rapport and affectionate jibes are more engaging than the plots. And in both Rio Bravo and El Dorado, Wayne plays a unique double role: sometimes the activist or gunfighter-turned-lawman who leads the group and makes most of the decisions, and at other times, the passive observer who looks over his friends with affection, amusement, and concern. In the latter role, Wayne enjoys some of his most laid back and contented moments on the screen.

EL DORADO

Inseparable from Rio Bravo and directed by Hawks a decade later, El Dorado is generally regarded as the weaker of the two films, derivative, and possessing less of the warmth and camaraderie that is found among Rio Bravo's brilliantly eccentric cast: Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Angie Dickinson, John Wayne, and Walter Brennan. El Dorado seems cooler, more detached, more amusing. The characters suffer and endure their hardship in calm, rueful awareness. Wayne as Cole Thorton and Robert Mitchum as J. P. Harrah fill their roles as middle-aged, drunken westerners, one a gunfighter and the other a lawman. They are smoothly comic, building our sympathy and our laughter by twisting their big frames into knots of hangovers and stomach pains, their thick bodies and rugged faces expressing their irritation at the fixes into which they get themselves.

James Caan is a self-assured sidekick, like Mitchum. He is conscious of the ways he can move and shift his large lean body in relation to the physical presence and force of Wayne's gunfighter, on or off his horse. Cheeky, as was Ricky Nelson, Caan plays Alan Bourdillion “Mississippi” Traherne to provide counterpoint and give rhythm to the careful maneuvers he carries out with Thornton. Together, they are the outsiders who come to El Dorado to back up the other male couple, Harrah and Bull (Arthur Hunnicutt), the town's lawmen who are urgently in need of help in defeating landowner Bart Jason (Ed Asner) and his hired gun, Nelse McCleod (Christopher George), in their fight against the MacDonald clan. In the Martin-Wayne pairing in Rio Bravo, Wayne's character chastises and prods Martin's “Dude,” the lesser man, toward regeneration. But Dude remains weak and humble when not self-loathing. In El Dorado, Harrah and Thornton are equals, both first-rate with a gun, and old friends from the Civil War years. They do not hesitate to exchange insults as only those men do who have affection and respect for each other.

In an atmosphere remarkably relaxed, given the seriousness of the hostilities (for this is a typical Western struggle for control of water rights), the narrative makes two points clear. The first is that Thornton is the observer, the much larger-than-life hero who can stand to the side and take real pleasure in watching and listening to others. While Thornton gives good advice and strong criticism at times, and goes into action if necessary, Wayne plays the lead character as if it were a supporting role. It is a unique kind of performance for so strong a screen actor; it is his gift to the motion picture. Wayne has brought to perfection here his long-running characterization of the relaxed and friendly (but ruthless when necessary) gunfighter. Harry Carey Sr., as Cheyenne Harry in some twenty-five early Ford silent Westerns, had sharpened a screen persona that helped to shape that of the young Wayne, and it is Carey's on-screen naturalism and openness to others that are also Wayne's hallmarks as an actor.21 And while he is forceful and dominant in many of his best remembered leading roles, Wayne played substantial supporting roles in films such as Ford's They Were Expendable (1945) and Fort Apache (1948). He could easily play characters who listened closely to others and gave them his support, even if reluctantly.

A second major point conveyed in El Dorado is that friendship and mutual support in the Old West are governed by certain unspoken rules. Harrah is the sheriff of El Dorado, and his position must be respected, even when he becomes a drunk. It is Harrah who makes the decisions, who controls or tries to control the actions of villains and victims. Thornton consistently turns to Harrah and asks him what he plans to do, though there is a low point when Harrah is too hungover to get his gun in his holster and Thornton leaves him behind. Harrah, however, catches up and behaves like a sheriff, even though a sick one. These two aging gunfighters, one a sheriff and one for hire, were once equally fast on the draw. They become equal again, as Thornton is weakened by a bullet lodged near his spine, the result of being shot by Joey MacDonald (Michele Carey) as an act of revenge against Thornton for having fatally wounded her brother. Increasingly, the bullet pressing on his spine causes sharp pain in Thornton's back, followed by moments of paralysis that make him vulnerable at key moments of the plot. He and Harrah are well matched: middle-aged, hurt, no longer invincible, needing their sidekicks and each other. By the end of the film, their friendship has survived and ripened. The final scene follows Thornton and Harrah on their evening patrol of El Dorado, each leaning on his crutch, with Harrah telling Thornton sarcastically: “We just don't need your kind around here.”

Despite the gunfire, El Dorado is partly a comedy about the difficulties of staying at the top of one's profession. Hawks rejected Leigh Brackett's initial script, a drama of guilt, justice, and sacrifice adapted from the novel The Stars in Their Courses by Harry Brown. Hawks had asked Brackett, to her dismay, to revise the original screenplay so as to create a character study of another kind: the aging gunfighter who can no longer go it alone.22 The movie's plot and its personalities are freely borrowed from Hawks's earlier Rio Bravo and The Big Sleep (1946).23 As we are never in doubt about the fate of the leading characters, Hawks indulges his comedic predilection to humiliate the heroes throughout the narrative, to challenge their wit and intelligence and humanity so that we can then watch them survive, if not triumph. We are reminded loosely of the series of comic humiliations that are experienced by different characters in McCarey's Ruggles of Red Gap (see chapter 3).

Wayne is not really funny except when he is the commentator and can punch out his one-liners. In El Dorado he addresses a hired gun as “Hey, fancy vest!” or complains, “They're no gud,” just as he repeatedly and amusingly exclaims, “That'll be the day,” in Ford's The Searchers. In Rio Bravo and El Dorado, Wayne is humbled not by his costars' characters but by the families fighting for control. Not even Angie Dickinson's love interest can really bring him down to size in Rio Bravo, and it frustrates her to tears. Red River is an exception, in which Garth humiliates Dunson almost beyond recovery. But Red River is hardly comedic, at least not until its last scene and except for a few moments of levity resulting from Walter Brennan's usual way of turning on his folksy wit, noted earlier in this chapter. Like Ford's later The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Red River brings out, indeed introduces, the ornery side of Wayne's screen persona: his stubborn wrongheadedness, his bitterness over the loss of love and youth, his thirst for revenge. Nearly twenty years later Hawks wanted, for El Dorado, more readily likable characters to enact his human comedy of repeated failures and occasional successes amid attempts at survival, self-recognition, and friendship.

If Red River and Hawks's later The Big Sky are landscape Westerns, frontier epics set in wide-open spaces, Rio Bravo and El Dorado are most meaningful at night. They are films shot predominantly on a studio set, emphasizing an intimacy, an easy humor, and a playful give and take, all within Hawks's straightforward mise-en-scène. El Dorado takes place in and around the town of the same name, deep in the Southwest and not far from the Sonora border: ranch country where water is gold. The film opens in the washroom of the Saloon and Lodging, where Thornton and Harrah meet again after their last adventures during the Civil War. Their friendship and mutual goodwill immediately transcend a misunderstanding, and Thornton agrees to turn down the job offered by Bart Jason, who seeks the MacDonalds' water rights. Standing with rifle in hand, pointed at Thornton, and with one foot on the bathtub, Harrah explains the way it is. Mitchum's posture and sleepily deep-voiced delivery set the comic tone that will dominate the film. Maudie (Charlene Holt) barges in and bursts out laughing at seeing her two former lovers at once; she and Harrah affectionately share their views of their loyal and supportive friend Cole.

FIGURE 27. Cole Thornton (John Wayne) and Maudie (Charlene Holt) observe with amusement the bathing Sheriff J. P. Harrah (Robert Mitchum) in Hawks's El Dorado (1966). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The plot is given shape by Thornton's visits to two ranches: first to that of Jason, where he tells the rancher he will not be working for him after all, and then to the MacDonalds' spread, where he brings the body of the boy Luke (Johnny Crawford) whose death he accidentally caused along the way. Thornton is in control as he returns the pouch of his wages to Jason, yet wary when he leaves, making his horse step backward along the low buildings so he can keep an eye on Jason's men. At the MacDonalds' family compound, Thornton relates in simple spare sentences the shooting and subsequent suicide of Luke. In a few wrenching moments, Thornton speaks almost breathlessly. However difficult it may be for him, he handles the father's questions with grace and the sister's anger with terse dignity. It is a quiet, serious, beautifully realized scene, with Wayne once again revealing his heroic and stoic stature.

The latter scene had been in both the novel and initial screenplay, but the film narrative subsequently goes in another direction. Thornton's first visit to El Dorado ends with the death of Luke MacDonald and a send-off by friends, with a bit of bugling by his old army buddy Bull, for he decides to drift down Sonora way in search of another job. Wisely, his former gal knows he cannot stay in El Dorado until he can forget what happened to Luke. Some months later, his wanderings are cut short when he arrives at night in a town filled with cantinas. Here he learns that Harrah has become a drunk and Nelse McLeod has been hired as Jason's gunfighter.

Sitting quietly by is the young “Mississippi”: he has come to kill one of McLeod's men who is responsible for the death of Johnny Diamond, the man who had raised him. Mississippi encounters Thornton and the narrative segues into a leisurely ride, during which the experienced man and the maturing youth become partners. They ride through a desert of cholla and saguaro cactus, indicative of Arizona-Mexico territory. The setting may be Texas, but Old Tucson provided most of the filming locations.24 The ride reveals to Mississippi Thornton's disability, and the younger man is in turn shown to be inept with a gun. A friendship has begun, and the narrative reverts to the comic mode. As their horses trot through the desert in bright sun, Thornton attempts to educate Mississippi about the etiquette of gunplay, then listens to the younger man's recital of the first and last verses of Edgar Allan Poe's poem Eldorado, written in 1849 at the height of gold fever:

Gaily bedight,

A gallant knight,

In sunshine and in shadow,

Had journeyed long,

Singing a song,

In search of Eldorado…

Over the Mountains

Of the Moon,

Down the Valley of the Shadow,

“Ride, boldly ride,”

The shade replied,

“If you seek for Eldorado!”

The young knight is warned by his more experienced pilgrim shadow that the dreams of the soul are not to be found easily. Thornton's immediate response—“Ride, boldly ride? Well, it don't work out that way”—expresses not only his wise acceptance and understanding of the knight's, or gunfighter's, spurious quest, but it also startles us into grasping the theme of the film. It does not work out that way, at least not in one's lifetime in the Old West. Nothing goes quite as planned, certainly not for J. P. Harrah, Jason, or the MacDonalds, nor for Nelse McLeod, perhaps the most gallant knight of all because of his noble adherence to a code of honor, even among killers.

Beginning with the scene of the midnight arrival of Thornton and Mississippi in El Dorado, the film mixes location shooting and studio production to create the narrow streetscape running from jail to saloon. This setting dominates the rest of the story, serving to enhance the immediate dangers and absurdities of the plot. Like other Western communities, El Dorado is a tightly enclosed town: a locus of hostility, action, and romance, with its own hybrid culture of ranchers, Mexicans, gamblers, and troublemakers. Its small world is a cosmos unto itself, though you will not find it on a map. One reaches the town by riding over and around various sizable rocks, crossing a stream (the MacDonalds' water source) and riding by flat ranch land. El Dorado is both somewhere and nowhere. It is a town out of a dream, slyly constructed in the last fully realized film by the master storyteller Hawks, who himself was growing older (he was seventy at the time).

Except for the death of the youngest MacDonald, the subsequent shootings and killings have a darkly comic edge. Hawks injects surprise and eccentricity into the mix of his law-enforcing quartet's efforts to exterminate Jason and his hired killers. Bull's bugle, a holdover from his Civil War days, marks his individuality, as does his bow and arrow. So too do Mississippi's prowess with a knife and incompetence with a gun. Bull is an old pro whose talents are never in doubt, unlike those of Mississippi, who will never make it as lawman or gunfighter. Their talents must be seen and enjoyed close up, on the set and at night. The dangerous activity in town takes place after dark, when the streets are full of traps and the saloon is lit up with bad guys and tinny music. To enhance the after-dark ambiance, cinematographer Harold Rosson studied, at Hawks's request, Frederic Remington's paintings of nighttime saloons, where light escapes through doors and windows and spills onto the otherwise darkened street.25 A yellow light infuses the town, with the actors highlighted by a bright white light so as to stand out against the buildings.

FIGURE 28. Cole Thornton (right) prepares to deliver a sobering blow to his old friend Sheriff J. P. Harrah in a comic scene. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The threat of McLeod and his quick gun hand moves the story along, and the film reverts to the theme of the gallant knight. At the first encounter between McLeod and Thornton in the cantina, McLeod shows his respect for a colleague: “Call it professional courtesy.” When McLeod kidnaps Thornton to exchange him for Jason, he emphasizes his regret for Thornton's disability and offers his apology, saying that it is not his fault, for he would never do anything to hurt a fellow gunfighter except kill him in a draw. In contrast, during the final shoot-out, Thornton resorts to a trick, hiding his shotgun and then shooting McLeod, who is not prepared for it. Thornton thus reveals his occasional willingness to violate the gunfighter's code of honor, demonstrating his strength of will to survive to a potentially peaceful old age. McLeod was the professional knight who wanted to live and die by the code, and Thornton cheated him. Thornton had neither the wish nor the need to prove who was fastest.

FIGURE 29. Pardners again: old buddies Cole Thornton and Sheriff J. P. Harrah. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Such is the stuff of drama, and El Dorado is above all a rueful, amused depiction of self-knowledge. “I'm paid to risk my neck, and I'll decide where and when I'll do it,” Thornton tells Jason earlier in the film. And he does just that, turning down Jason at the start of the story because, he says, he does not want to go up against his old friend Harrah. Later, accepting the greater risk of going against McLeod out of friendship with Harrah, Thornton makes no unnecessary plays, instead figuring out a way to kill McLeod most unfairly.

McLeod certainly falls into the camp of “good bad men” who challenge us to distinguish the good from the bad in their personalities and conduct. The more complex Westerns mix traditional notions of good and bad, as we have already seen in discussing Wayne's Dunson in Red River, a man whom we come to love as well as hate in the very same film. Sam Peckinpah's superb Ride the High Country (1962), like El Dorado, is a tale of former partners who reunite but in quite different ways, and we root for both Joel McCrea's and Randolph Scott's respective characters, even when we find them morally opposed. In El Dorado, we know that Thornton has pulled a fast one on McLeod at the end, killing a man who adhered to the principle of a fair and honest fight. It does not seem like the type of thing that John Wayne is supposed to do, but as Hawks teaches us here, it is survival and friendship that really count in the end.