CHAPTER 5

Indian-Fighting, Nation-Building, and Homesteading in the A-Western

“Northwest Passage” and “The Westerner”

Some students of Western cinema have argued that the sudden rise in the number of high-quality big-budget Westerns between the years 1939 and 1942—what has been labeled as “the A-Western Renaissance” and described in chapter 4—had much to do with a growing recognition on the part of studios and filmmakers that the Western was able to reflect a contemporary culture caught in a process of intense transition and self-definition. The Western could represent in a dual fashion both the new seeds of optimism in the late 1930s, given that the Great Depression was coming to a close, and the collective memory of hardship and struggle that had been experienced by the average moviegoer throughout that decade. The surge in A-Western production might be related to the complex spirit of its times by encompassing both prospective and retrospective feelings about the recent social, political, and economic situation.

Rather than dealing directly with the problems of the Depression and the collective project of national renewal in the Roosevelt years, many of the A-Westerns of this period offered a vicarious way of reflecting on hard times, mainly because a good number of Westerns were set in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era. In such an era, those who had been most negatively affected by the destructive effects of the war—mainly southerners, who were coping with a great sense of loss—had fled to the frontier in order to rebuild their lives and even to seek fortune. At the same time, an entire nation was attempting to mend its wounds after such a devastating conflict. And the Western film was especially apt for expressing such conflicts and reconciliations. Film scholar and theoretician André Bazin has commented on the rise of the A-Western from 1937 to 1940 and the return, to the Western form, of established directors who had started their careers in this genre. “This phenomenon,” he says, “can be explained by the widespread publicity given westerns between 1937 and 1940. Perhaps the sense of national awareness which preceded the war in the Roosevelt era contributed to this. We are disposed to think so, insofar as the western is rooted in the history of the American nation which it exalts directly or indirectly.”1

At the surface level, Western films provided simple escape from the everyday worries of those coping with the effects of a national economic disaster: better to let the mind occasionally escape to golden sands and the mythical realm of cowboy heroes rather than to face reality on a strictly full-time basis. At the same time, while providing escapist fare on one level and reflections of a difficult existence on another level, the Western was also capable of providing a feeling of hope for optimistic resolution and closure. In most cases it was the “good guy” who prevailed, and certainly not the crooked banker or corporate landgrabber or the gunslinger hired by him. Since many A-Westerns took the form of trail-blazing and community-building frontier epics, reminding their audiences that a great nation had arisen eventually and successfully from a savage wilderness and a constant struggle against adversity, these films also provided a sense of idealistic faith for viewers who had wearied of economic devastation.

It is not surprising, when one considers the evidence, that A-Westerns of the immediate pre-World War II period offered their audiences as much cultural self-reflection as escapist entertainment. One needs only to consider here that Ford's Stagecoach of 1939—the film that in many ways helped the most to revive the genre, despite its occasional reliance on certain B-Western conventions—had as much to do with themes of social prejudice and class distinction as it did with Geronimo and revenge (see chapter 4). Henry King's popular Jesse James of that same year—starring Tyrone Power as the title character and Henry Fonda as his brother Frank—explained the legendary outlaw's initial motives in terms of an act of revenge against banks and railroad companies who had hired thugs to harass the James brothers' poor mother (played by the ever maternal Jane Darwell) in order to acquire her property. And in Wyler's The Westerner of 1940, a portrait of the ruthless Judge Roy Bean is set within the wider context of a feud, with ranchers and cattlemen set against farmers and homesteaders. This context would resonate with movie viewers who had recently witnessed a nation's struggle for economic survival and who had found themselves on the threshold of another battle between good and evil, that of World War II.

The B-Western was indeed alive throughout the 1930s, and hundreds of these lower-budget movies had been churned out. Often these B-Westerns reflected Depression-era realities by dealing with the land ownership problems of struggling individuals, especially those who faced the threat of greedy capitalists out to acquire their land.2 The large number of A-Westerns produced during the first few years of World War II can be explained, at least partially, by the long-running success of the B-Westerns, as well as by the A-Westerns' occasional suggestion of the wider political and economic realities that America had been facing. A-Westerns such as Jesse James and Destry Rides Again deal explicitly with cheating land-grabbers who attempt to swindle innocent families out of their property (Brian Donlevy plays the greedy heavy in both of those movies). And certain non-Western classics of this era—Fleming's Gone with the Wind (1939) and Ford's The Grapes of Wrath (1940), in particular—also express a similar theme of survival amid great economic despair. Many of the A-Westerns and B-Westerns of the mid- to late 1930s also helped to restore, for those Depression-era folk who had recently migrated to the cities, a nostalgic sense of authentic origins. The rural Old West became a symbolic substitute for rural America in general.3

From an even broader perspective, and as history has taught us, hard times and crisis situations can bring about serious reflection on the virtues, vices, and variables of human nature itself. Most Western films appear, on the surface, as simplistic stories about fights between cowboys and “Injuns” or between heroic and villainous gunslingers. But the majority of A-Westerns produced by the major Hollywood studios have had something deeper to say about the human condition, usually because of thoughtful screenplays, and they have done so despite their primary commitment to action-packed narratives meant to thrill as well as to enlighten their audiences. In reflecting upon recent trials and tribulations—as well as upon our acts of overcoming such obstacles—we are often led to broader ruminations about what it means to be a human individual caught within time and history. The Great Depression and its aftermath cried out for such reflection.

Two underappreciated A-production Westerns that were released in 1940 and that exemplify the national optimism and cultural retrospection of the time are Vidor's Northwest Passage and Wyler's The Westerner. They are two very different types of Western featuring two very distinct kinds of Western hero, thus revealing the richness and diversity of the genre at this crucial stage in Hollywood's classical Golden Age. Vidor's film is an epic frontier saga centered on themes of Indian-fighting and wilderness survival; its protagonist is a military hero who provides a model of strength and perseverance amid the greatest adversity. Wyler's movie portrays a humble westerner who knows how to use a pistol but does so only when absolutely necessary, and who enters into a range war between homesteaders and the villainous Judge Roy Bean, the defender of cattlemen's interests. Both Westerns are as impressive for their dialogue as for their action, and both represent the highest qualities of the A-Western Renaissance.

NORTHWEST PASSAGE

An especially intriguing example of a high-quality, landscape-oriented A-Western of the World War II era is King Vidor's Northwest Passage (1940), a colorful and visually rich portrait of frontier survival. The film was based on Kenneth Roberts's epic novel (published in 1937, but first serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1936) that deals with the real-life trail-blazing adventures of a band of men known as Rogers' Rangers. While the exploits depicted in the novel and film were undertaken in northern New England and the Saint Lawrence River region, the filming was done chiefly around Payette Lake in Idaho and in the forested mountains of Oregon.4 The movie exhibits the kind of appreciation for the natural world that reminds us once again of the influences of nineteenth-century landscape photography and landscape painting. But it also revolves around the kind of optimism and faith that was required in the early part of the struggle to build a nation and that might have resonated with viewers who had recently experienced a decade of countrywide economic depression and who were now pondering the possibility of America's involvement in an ever spreading battle between good and evil in Europe.

Above all, Northwest Passage depicts in a graphic way the suffering and struggle of colonial soldiers undertaking frontier battles during the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American extension of the war between Britain and France (eventually known as the “Seven Years' War”). The story's hero, Major Robert Rogers (Spencer Tracy), commands a band of rugged colonists who fight for the British against the French and their native allies. Rogers is the epitome of the stoic military leader who must mask his own sympathies and weaknesses in order to inspire his men to greatness, always with the goal of victory in mind. The titles of the novel and film reflect the later life of the historical Rogers (1731–1795), after his active military career, when he was appointed by King George III as a royal governor in a fur-trading area of Michigan. One of his primary missions was the organization of expeditions to discover and chart the legendary “Northwest Passage” that would provide a trading route across the continent.5

Susan Paterson Glover observes in her essay “East Goes West: The Technicolor Environment of Northwest Passage (1940),” in reference to the vision of Rogers that was expressed in his own writings: “Rogers's account of the colonies in his Concise Account of North America had prophesied for the northwestern frontier the possibility of ‘a rich and great kingdom, exceeding in extent of territory most of the kingdoms in Europe, and exceeded by few, if any, in the fertility of its soil, or the salubrity of its air, and in its present uncultivated state, abounding with many of the necessaries and conveniences of life.’”6 The combination of Rogers's earlier military accomplishments and his later involvement in frontier exploration, plus his writings about such events and deeds, makes him an apt symbol of America's early efforts in realizing its idealist project of nation-building—even if Rogers sometimes sympathized more with the British than with the colonists, especially during the course of the American Revolution. While he had been convicted by the British of being a traitor (though he was later pardoned), been suspected by American leaders of being a spy for the British, and died as a broken alcoholic in debt, Rogers lives on in Roberts's novel and in Vidor's film as a man filled with strong faith in the idea of an expansionist America.

The movie is both historical Western saga and heroic odyssey. A sequel had been planned but was never realized; it was to continue the story of Rogers by detailing his attempt to discover the fabled passage to the Pacific, a route that had been sought by explorers for centuries. With the continuation of the story in mind, MGM had subtitled Vidor's film “Book I—Rogers' Rangers.” One of the apparent reasons why the studio canceled plans to undertake a sequel had to do with lower box office returns than expected and high cost overruns, especially as a result of the many physical and logistical obstacles encountered in the production of the first film.

The movie's use of Technicolor impresses the viewer (and must have certainly impressed its audiences in 1940) with its rich palette and deep hues. Certain scenes of men paddling canoes down sapphire-blue rivers and against forest-green backdrops remind one of landscape paintings by Bierstadt and color-soaked illustrations by N. C. Wyeth (as in the latter's contributions to an edition of Cooper's The Last of the Mohicans).7 The choice of Technicolor adds to the movie's magic but gave Vidor and the studio more than a few headaches when the enchanting colors of his on-site settings did not always translate into film as intended, especially when the first rushes were seen. As Glover tells us, “All color processes to that point that been unable to accurately reproduce hues of green, and considerable work went into finding a dye for the green Ranger uniforms that, on film, would blend in to the green of the natural surroundings. In his autobiography Vidor recalls the early production tests, when the dull green of the Rangers' uniforms appeared on the film as a ‘brilliant Kelly green.’”8

Vidor honed his talents as a director during the silent film era; his two masterworks of this period are The Big Parade (1925) and The Crowd (1928). The latter was an authentic portrait of the American common man, a film that depicted the shining dreams and gritty hardships of the Roaring Twenties with the same tension between realism and romanticism that Vidor brought to the story of frontier struggles in Northwest Passage. Later sound films by Vidor include The Champ (1931), Stella Dallas (1937), The Fountainhead (1949), Ruby Gentry (1952), and War and Peace (1956). His other Westerns include Billy the Kid (1930), The Texas Rangers (1936), Duel in the Sun (1946), and Man without a Star (1955). Vidor concluded his long career as director in 1980 with a brief documentary titled The Metaphor, which features painter Andrew Wyeth. It was perhaps only natural that Vidor, another “painterly” director in the vein of Ford and Walsh, returned to filmmaking in his final years to discuss painting.9

Northwest Passage is not a typical Western, by any means, in that it is set much farther east than most Westerns, starting off in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and then bringing its viewer to an early version of the “Western” frontier—that of the northern New England region surrounding Lake Champlain and extending upward into the terrain around the Saint Lawrence River in Quebec. And rather than being set in the familiar post-Civil War era that historically frames many Westerns, the story here takes place during the French and Indian War of the 1700s. Like John Ford's Drums along the Mohawk (which was released a year before Northwest Passage, in 1939, the same year as Stagecoach), Vidor's film was shot in strikingly brilliant Technicolor, constitutes an “eastern” Western of sorts, and is one of the few successful and well-crafted movies to be set in the colonial period of American history. Also much like Ford's film, Northwest Passage is the story of those individuals, whether militia-forming settlers (Drums) or frontier warriors (Northwest), who must confront savage enemies and overcome natural obstacles while protecting their families and fellow fighters at all costs. Northwest Passage and Drums along the Mohawk fall within the broad parameters of the Western genre because they revolve around themes of wilderness conquering, Indian-fighting, and frontier settling. If the Western is primarily the story of American expansionism and the struggle against primal adversity, then movies like Northwest Passage and Drums belong fittingly to the genre, despite the qualms of any genre guardians concerning geography and historical setting.

Above all, these are films in which, like many of the great A-Westerns, the landscape plays a dual role as both inspiration and obstacle. This is especially true of Vidor's movie, where the brave crew of Indian-fighters must travel vast distances through dangerous territory, haul their boats over hilltops, trudge through swamps, ford raging rivers, and above all, seek to survive in a rugged terrain where food is scarce. There are other Westerns, of course, whose primary theme is survival in the face of extreme hunger, thirst, and the threat of a hostile enemy. But Northwest Passage depicts the rigors and dangers of the wilderness more explicitly than most other Hollywood Westerns of this era. Here, Vidor reveals the great beauty of the terrain, but also the ways in which the suffering involved in the attempt to trek through that land leads at times to possible madness and death.

In the end, a sense of spiritual faith is the only thing left to give the Rangers (or at least most of them) a vestige of hope. Many are on the verge of complete mental and physical collapse and a few have already crossed that threshold. Up to this point, it is their sense of duty, dreams of an expanded civilization, and hatred of a common enemy that keep Rogers's men going. The story of American territorial expansionism has its dark underbelly, and Vidor's film (as well as Roberts's novel on which it is based) does not shy away from describing that side of the tale, showing both the romantic power of the mythic ideal and the deadly costs and sacrifices in pursuing that ideal.

As with the rigors and challenges of shooting The Big Trail (see chapter 4), the production of Northwest Passage involved countless hurdles that sometimes echoed the ordeals faced by Rogers's frontiersmen. Shooting began in Idaho in June 1938, but filming ceased soon after and was postponed until the following spring, mainly because of “logistical and management problems.” Technicolor technology had been enhanced during the months in between the two shoots, and so the footage from the previous summer (under the direction of W. S. Van Dyke) was not used and Vidor took over as director when filming recommenced in the spring.10 Other production obstacles ranged from the need to inoculate the entire cast and crew against tick fever to the necessity of reshooting scenes because of changes in the physical environment, such as fluctuating foliage colors and water levels.11 As yet another example of the obstacles that occurred, part of the on-site filming in the summer of 1938 involved the initial shooting of the thrilling scene in which the Rangers create a human chain across perilous river rapids. The filming had been started at the Yellowstone River, but the task proved too dangerous for cast and crew and the rest of the scene was shot on the MGM studio lot using a massive water tank.12

Northwest Passage begins with an emphasis on geography, giving a “lay of the land” in the most literal sense: a series of maps of colonial North America during the time of conflicts among the British, the French, and their Indian allies. Maps and mapmaking, in fact, figure prominently in the plotline of the film and remind us of an essential expansionist theme: the American drive to conquer and organize natural spaces. The narrative officially begins in colonial Portsmouth in 1759, and one may recall the opening of Ford's Drums along the Mohawk, which starts with the wedding of Gil (Henry Fonda) and Lana (Claudette Colbert) at Lana's elegant European-style family home in Albany. Here a clear contrast is drawn between the cultured, commercial, colonial East, on the one hand, and the raw frontier wilderness, on the other.

We see men on the Portsmouth waterfront, preparing the rigging of a ship and laboring at other tasks. One worker who sits on a crossbeam spots the Boston stagecoach arriving. We now see that it carries young Langdon Towne (Robert Young), who has returned home from Harvard after going there at his family's behest to study for the clergy. We learn right away that Langdon is an aspiring artist who wishes to practice his vocation at all costs. Above all, he desires to develop his craft as an “American” painter by portraying, not the civilized colonist, but the Indian as he exists in his natural setting.

After arriving back in Portsmouth, Langdon runs into Hunk Marriner (Walter Brennan), who has been put into stocks for, as the accompanying sign states, “Disloyal Conversation.” Given Langdon's report about his expulsion from Harvard for having published a politically controversial caricature, there is a parallel to be drawn here: both men are not afraid to flout authority in their desire to speak their minds. They are especially apt exemplars of the archetypal easterner who becomes a westerner, particularly since they are men who feel constrained and frustrated by the conventions and restrictions of a rigid Puritan lifestyle in old New England. Langdon and Hunk yearn for freedom, yet they unfortunately wind up in a regimented existence amid a savage wilderness and a brutal war.

FIGURE 19. Spencer Tracy as Major Rogers (second from right) converses with new recruits Langdon Towne (Robert Young, center) and Hunk Marriner (Walter Brennan, left) in King Vidor's Northwest Passage (1940). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

It does not take long before our protagonist lands in serious trouble yet again after he insults a representative of the Crown while highly inebriated at a local tavern. Langdon and Hunk (who has come to his friend's rescue) escape, even though Langdon must leave his beloved Elizabeth (Ruth Hussey) behind. They make their way by canoe to a small outpost on the frontier, Fort Flintlock, where they meet up with Major Rogers and help him sober up a besotted Indian guide. Langdon soon tells Roberts that he has drawn maps of western territories because he wants to go there to paint Indians “as they really are”—saying this even as the viewer is treated to a wholly negative and stereotypical portrait of an Indian. Langdon appears initially to be someone who is sympathetic with “the red man.” He and his sidekick, Hunk, are, at this point in the film, heading to Albany—supposedly where “the West” begins—so that he can travel with traders and thereby fulfill his dream of seeing and painting the “real” West.

Rogers wants Langdon to join his company because he desperately needs a man who is good at drawing to be the mapmaker for his next expedition. He tells Langdon that he may be a bit too educated for the rough woodsmen who make up the Rangers, but Hunk retorts, “He's not that educated.” Langdon scoffs at Rogers's invitation: “I want to paint live Indians, not dead ones.” Rogers then explains why Langdon may someday need to kill the native he may be painting, because of the real threat involved, telling him that his aspiration is merely some romanticized dream. As we will soon see, Langdon proves Rogers right and the artist winds up killing Indians rather than painting them.

As Armando Prats points out in his book Invisible Natives: Myth and Identity in the American Western, Langdon's initial artistic goal and his subsequent forsaking of that goal during his Indian-fighting adventure are especially symbolic of the ways in which the Native American is referenced in Hollywood Western narratives. They are referenced, but only to be vanquished, forgotten, and erased via these movies' various forms of “cultural appropriation.”13 Prats, in fact, uses Northwest Passage as his chief cinematic example in introducing and outlining his book's overall argument about the treatment of the Indian in American Western films.14 As revealed by his sketchbook when shown to Major Rogers, Langdon has been content to render drawings of his beloved Elizabeth and of Rogers and selected other Rangers. But the Indians against whom he is fighting are never depicted, dead or alive.15 Langdon gradually comes to view the natives through Rogers's eyes: as savage enemies, as possibly deceitful scouts, or as hopeless drunks who, like Rogers's inebriated and inarticulate guide, Konapot, have been partially assimilated to white society.16

This pattern, according to Prats, follows the general trajectory of the overall myth of conquest, the master narrative that underlies much of the genre from the silent era (see chapter 1) up until today. This myth is part of a wider one that Richard Slotkin has called “the myth of America” and “the Myth of the Frontier.”17 The shaping of the very idea of America as a cultural entity, argues Prats, depends on such an appropriating, distorting myth, along with its implicit principle that the Indian must be made “present” in a given Western narrative—but presented always as the Other, an Other who must inevitably be made “absent.” The making-absent of the Indian echoes, of course, the historical genocide against the native. But Prats is chiefly concerned with the specific ways in which the evolution of American cultural identity depends on those dialectical tensions (same/Other, presence/absence) that help to constitute the Western mythos and the story of its expansionist consequences—most especially in terms of how that story is articulated through the cinema's treatment of is victims. According to this interpretation, it is in its very act of representing the Indian that the traditional Western movie relegates the native to a realm of absence and alterity. As Prats tells us, “If the opposition [to the Indian Other] is essential to the national self, so too is the elimination of it. Perhaps the ambiguity explains why the Indian is the Western's everlasting revenant: the Western had to save the Indian so that it could destroy him.”18

Langdon's ignoring of his original artistic goal and his adoption of Rogers's vision of the Indian is one of many ways in which this kind of narrative pattern is manifested, according to Prats. The native can never be rendered “as he is” as long as his depiction is subsumed under the broader myth of expansionism and conquest, a myth that has been central to the story of America. Another example of this pattern occurs when the Western narrative defines the Indian through the words of the white frontiersman, the man who knows the native well enough to interpret the latter's motives, actions, and very existence.19 The apparent expert, a “provisional savage” of sorts, is usually put into the position of needing to explain the ways of the Indian to a naive counterpart. Here again, the Other is referenced or made present, as is necessary in the dialectic of conquest, but he is simultaneously made absent by a distorting form of mediation, by the very act of being represented by his knowing enemy.20 In Northwest Passage, it is Major Roberts who acts as this type of substitute, instructing Langdon about the kind of people these natives really are and the types of bloody deeds that they have enacted. We might also think here of Ethan Edwards in Ford's The Searchers, who knows enough about his Comanche enemies to speak their language, guess their strategies, understand their spiritual beliefs, and mirror to some degree the dreaded Chief Scar (see chapter 8).

Lured into the company of the Rangers after the oblivion of a drunken night, Langdon and Hunk soon become accepted to some degree by the rough-hewn Rangers. They soon venture as new soldiers through a wild but majestic terrain that poses danger as much as it affords beauty. The idea of the landscape as an obstacle to be conquered emerges specifically when we witness the Rangers toiling to transport their boats over a hillside so as to avoid being spotted by the French and their Indian allies. These enemies are camped just down the shoreline, obstructing their voyage, and the men groan and sweat as they lift their boats with a massive rope. Vidor shows us each step of this burdensome task, including the eventual lowering of the wooden vessels down the hillside and the boats finally sliding into the river, now beyond the place where the French ships are waiting. Rogers has outwitted the enemy with his trademark determination and his expert coordination of collective labor.

FIGURE 20. “All for one and one for all” in the exciting river-fording scene from the frontier epic Northwest Passage. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Soon after, Rogers tells his men what their mission really is, using a map painted on the stone face of a hillside. They have been assigned by their British superiors to destroy the Abenaki village of Saint Francis in Quebec, given the destruction wrought by the Abenakis' past raids on the whites. Rogers clearly explains why they need to go after the Indians, calling upon one of the Rangers who describes in brutal detail how the Abenakis had torn his brother's skin upwards from his belly and then hanged him from it while he was still alive. This description of torture cements in the men's minds the fact that the Indians are animal-like savages who must be destroyed. Ruthless revenge becomes a duty and a matter of justice.

It would appear on the surface that the attack on the Abenakis is justified from what Rogers and his Ranger have to say about the bloodthirsty deeds of their Indian enemies. It is this surface-level view that undoubtedly led Western experts George Fenin and William Everson to point out that this film holds a special place in the genre because of its unrelentingly negative depiction of the Indian enemy: “Northwest Passage has a place in the general history of the Western for being one of the most viciously anti-Indian films ever made…. The Indian's side of the question is never presented.”21 Or, as Prats has argued, the Indian perspective is presented here, but through the words of Rogers and his men—and so presented only through a distorting, appropriative, and deeply biased interpretation that renders the native's “genuine” viewpoint completely absent.

However, as Susan Glover argues, things are not quite so simple as they would at first appear. That is because, while we hear about the Abenakis' brutality, the movie actually shows us the brutality of the Rangers. The scene of the massacre of the Abenaki village is graphic enough to make the viewer wince at the fierce violence waged by Rogers's men. While the film concentrates on the military goal of the Rangers in the face of an Indian enemy, it also chooses to communicate the savagery of the enemy in words—a clear distancing device—while demonstrating the vengeance of the hero and his men in direct, violent images. While Prats may emphasize the ways in which the film's “white” mediation of the native's perspective inevitably displaces and even “erases” the native himself, what the viewer ultimately experiences is a narrative in which Indian violence is presented in a deliberately detached manner and the Rangers' acts of violence are conveyed in immediate, horrifying imagery. Such an observation certainly qualifies, at least to some degree, the criticism that Northwest Passage is purely “anti-Indian.” At the very least, there is an implicit dialectic in place here between the different modes of presenting these opposing perspectives, one that complicates the film's presentation of its basic subject matter.22

Vidor proceeds to provide regular glimpses of the landscape as the Rangers then journey to Saint Francis and avoid detection by the French and Indians. After the massacre of the Abenakis at Saint Francis, Rogers's men journey homeward and suffer from extreme hunger. There were no substantial provisions to be found at the village they just destroyed, and they have only a few kernels of corn to sustain each man. We then experience a highly morbid element of the film's narrative that points to the harshness of the Rangers' lives and the extreme personal costs of conquering a land for the sake of building a nation.

At one point during the battle at Saint Francis, a Ranger named Crofton (Addison Richards) had begun to show signs of having suffered severe psychological effects from such a brutal existence. He was about to kill a native child, but another Ranger prevented him, saying the child is “too young” and must simply be taken prisoner. As if to channel his rage, Crofton savagely attacks an already dead adult Indian with a hatchet. After the battle, the increasingly deranged Ranger soon shows himself to be more than disturbed, mocking the hunger of his comrades and carrying a mysterious bundle around with him as if it were a sack of treasure. Not long thereafter, the demented Ranger steals away to feed off the contents of his treasured sack: the head of the Indian whom he had viciously massacred. We are not shown this gruesome event, of course, but the horror of this scene is increased by the fact that Vidor leaves the act of cannibalism to the power of the viewer's imagination. Eventually Crofton leaps off a cliff in a suicidal frenzy, leaving a stunned Rogers to offer a eulogizing salute to a formerly loyal member of his band.

Despite the splendor of the natural scenery around them, the Rangers have suffered greatly, even been driven to madness, by their lack of food and their expenditure of energy in conquering a hostile foe. They would gladly trade the beauty of their surroundings for a bit of sustenance. Fort Wentworth, their long-desired destination, winds up being a deserted outpost. Rogers rushes ahead to investigate the fort, finds it empty just before the men arrive, and for once expresses signs of weakness, breaking into a momentary crying jag before he hears his men approaching. An exemplar of stoic dignity, Rogers quickly regains his composure and then demands that the men march into camp. They are starved and exhausted, at the threshold of death's door, with the dream of food having kept them going until this point. Rogers then refers to the Biblical example of Moses, who allegedly went hungry for forty days without food and water, and he cites a few verses from scripture (a paraphrased amalgam of Isaiah 40:3 and Isaiah 43:19–20): “The voice of Him that cryeth in the wilderness. Prepare ye the way of the Lord. Make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Behold, I will do a new thing. Shall ye not know it? I will make a way in the wilderness and rivers in the desert. And the highway shall be there, and a way. And wayfaring men, though fools, shall not go astray therein.”

FIGURE 21. Langdon Towne (left) has transformed himself into a determined Indian fighter in Northwest Passage. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

In the end, of course, hope is answered and British soldiers appear in boats, arriving to help the ragged Rangers after Rogers had earlier sent a few of his men back to their starting point to seek help. Rogers tells his men in their dilapidated attire to stand proud and straight with eyes front. We suddenly transition to the near future: the surviving Rangers march into town to great fanfare, with the citizens out in the streets to greet them upon their homecoming. The British commander wastes no time in giving Rogers his new orders—to find the fabled Northwest Passage. Langdon and Hunk, however, have decided that they will not join the men on their next adventure. Langdon tells his sweetheart, Elizabeth, who had been patiently waiting for him, that Rogers and his men are now marching off to make history. When she asks Rogers if there really is a Northwest Passage, he tells her: “There's bound to be.” And Rogers promises Langdon, before departing: “I'll see you at sundown, Harvard.” Langdon looks on as Rogers and his men march off, and he proclaims to Elizabeth, “That man will never die.”

The film concludes with a shot of Rogers silhouetted against the sky at the end of a dark road—not unlike the concluding iconic shot in Ford's Young Mr. Lincoln (1939). The chiaroscuro image reminds us that the road ahead will be a mixture of darkness and light. But as long as the light exists, there will be a mission to fulfill and a nation to build. Once again, the memory of suffering and sacrifice is combined with a sense of optimistic faith and historical destiny in order to do justice to the story of American expansionism. And yet the film clearly shows us—even if it does not say so—that the story of America and its ideal of Manifest Destiny are inevitably intertwined with death and loss, with racism and conflict. We may want to cheer Rogers on at the end of the film as he embarks on his new mission, but we also witness the refusal of Langdon and Hunk to join in, as they opt instead for a settled and civilized existence.

THE WESTERNER

There are epic A-Westerns in the World War II era—those like Union Pacific (1939) and Northwest Passage (1940)—that deal with the expansion and unification of an entire country. There are other A-Westerns of this period that emphasize the more intimate and local building blocks of nationhood: the theme of building a permanent home and starting a family, even against great odds. This theme is suggested by the struggles of Gil Martin (Henry Fonda) and his wife, Lana (Claudette Colbert), in building a frontier home in Ford's Drums along the Mohawk (1939). Home and family are the seeds of civilization-building. However, as Patrick McGee points out in his From Shane to Kill Bill: Re-thinking the Western, while the family is often viewed as the most basic social and economic unit that nurtures individualism, it also engenders “the contradiction between individual desire and social conformity, to which the Western frequently offers an imaginary resolution.”23

In many stories of the settling of the Old West, homesteading and home-building lead to the establishment of a stable form of agrarian existence. A tranquil farming life is the reward for the toil and tribulation of journeying from the civilized East to the wilderness of the West. This is especially evident in Wyler's The Westerner, in which saddle tramp Cole Harden (Gary Cooper) comes to ally himself with a community of farmers and finally triumphs over the ruthless Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan). Harden seeks to bring peace to the homesteaders after they have been terrorized by the cattle ranchers and their hired guns, those who want to keep the land as free range for grazing. The conflict between settlers and ranchers is a recurring theme in Western cinema and emerges as early as Ford's silent Western Straight Shooting of 1917 (see chapter 1). It is the central conflict in George Stevens's Shane (1953), and the battle with wealthy ranchers also frames the plots of later Westerns such as Arthur Penn's The Missouri Breaks (1976), Michael Cimino's Heaven's Gate (1980), and Kevin Costner's Open Range (2003).

In Wyler's film there is an explicit discussion of the virtues of having a permanent home, something that Harden does not readily concede, as he is a man of the open range. He is accustomed to making his “home” beneath sun and stars, as he proudly states. But by the end of the film, Harden has settled down with his beloved Jane Ellen Matthews (Doris Davenport), a young woman who had always dreamed of a stable house to call her home. Harden has finally been domesticated willingly, much like Ringo at the end of Stagecoach (see chapter 4). As Cole and Jane Ellen stare out the window of their new home in the concluding scene, they see a procession of familiar homesteaders returning to the area, those who had departed after Bean's men destroyed their corn crops. Harden proclaims quietly but firmly, “Yep, the promised land.” There are biblical connotations here, of course, but also the idea of Manifest Destiny, a near-religious ideal in the name of which empty land became eligible for claiming and for building a community, all for the purpose of expanding a nation to the very limits of its continent. Ultimately, it is the dream of a future home and the labor of creating it that is the real engine of progress, helping to ensure that this collective ideal becomes a reality.

Harden is no Ethan Edwards, who at the end of Ford's The Searchers must remain excluded from family and home, banishing himself once again to solitude amid the wilderness (see chapter 8). Since Harden is a man who actually surrenders his role as a lone westerner, he may be compared with William Munny (Clint Eastwood) at the start of Eastwood's Unforgiven, a man who has hung up his rifle (for a stretch of time, anyway) to start a family and care for his children (see chapter 10). Harden is also similar to Tom Doniphon (Wayne again) in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a gunslinging rancher who desires above all else to marry his beloved Hallie (Vera Miles) and settle into a happy, comfortable existence (see chapter 8). Edwards, on the other hand, never hangs up his gun or his role as westerner, even if at times he may desire strongly to do so. He saunters away, reluctantly but inevitably, in the famous closing shot of the movie, back to the desert from whence he came.

As Fenin and Everson point out in their survey The Western: From Silents to the Seventies, Wyler was one of the more intriguing and talented directors of Westerns to emerge from the silent movie period. While Wyler made only two sound-era Westerns aside from The Westerner—Hell's Heroes (1930, at the advent of talkies) and The Big Country (1958)—he directed a good number of silent Westerns and knew the fundamentals of the genre quite well. In 1925, Wyler's first two-reeler for Universal, Crook Buster, was released, and he directed twenty of these Universal Western shorts (which were called “Mustangs”) in all. He also contributed to the script for another Western, Ridin' for Love (1926), which was the only time he ever accepted script credit. Film reviewers at the time rated Wyler's The Ore Raiders (1927) as one of his “best and most action-packed films.”24 In addition, Wyler directed five of Universal's “Blue Streak” Westerns (typically five-reelers), including Lazy Lightning (1926), and he later made several other feature Westerns for Universal as part of the studio's new “Adventure Series.”25

Wyler directed The Westerner for producer Sam Goldwyn amid an impressive run of filmmaking that included such other masterworks as Jezebel (1938), Wuthering Heights (1939), The Letter (1940), The Little Foxes (1941), and Mrs. Miniver (1942). The many merits of the film include Wyler's superb direction, Gregg Toland's memorable cinematography, the accomplished performances of Brennan and Cooper, and expert dialogue by Niven Busch.26 This Western (like others, ranging from Stagecoach to Unforgiven) deglamorizes the West and shows the hard struggle involved in forging a civilized community amid barren desert and villainous gunslingers. The Westerner blends gritty action, visual poetry, and occasional comedy in the way that the best A-Westerns have always managed to achieve.

There are no Indians to be battled here, since the unjust ranchers led by Judge Bean give the homesteaders enough to worry about. The plot of The Westerner also includes heartfelt scenes of romance and mourning, along with the decisions of a hero who (shades of Destry Rides Again) seeks rational negotiation before resorting to his gun. Busch—who authored the novels Duel in the Sun and The Furies, the bases of two later “psychological” Western films (see chapter 7)—rooted his script in a story by Stuart N. Lake. Lake had authored the novel Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, which was the foundation of two different movie adaptations titled Frontier Marshal (1934, 1939) as well as the basis of Ford's My Darling Clementine (1946), which also starred Brennan as a villain. In addition, Lake penned the story for the later Western classic Winchester ‘73 (1950), directed by Anthony Mann.

In The Westerner Cooper wears his familiar persona of the quiet but charismatic hero. Brennan won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his mesmerizing performance as the tyrannical Bean (it was his record-breaking third Oscar win). The characters are broadly drawn, almost caricatured at times, but the director and his actors add unexpected nuances at just the right moments, particularly in shaping the peculiar relationship formed between Harden and Bean. There are several spellbinding face-to-face confrontations between the two men, with each representing, respectively, the good and evil sides of the archetypal Western gunslinger.

Bean is a continual and unpredictable threat. But at the same time, the hard-drinking judge seeks to form a friendship with Harden, and his heart turns to mush every time he glances at a picture of his beloved, the music hall actress Lily Langtry (Lilian Bond), after whom he decides to name his town. One might mistake Bean's occasional friendliness toward Harden and his love for “Miss Lily”—not to mention his gruff charm—as evidence of this character's moral ambiguity. But though Bean is not a simple man, he is always a ruthless and self-centered one, even to the bitter end, and his signs of sociability or dependency point more to his need for selfish marriages of convenience than to any inherent humanity. It is yet another lesson that wolfish tyrants can be beguiling at times, especially when they are the makers of their own rules and laws.

In fact, of the many memorable actors who played villains in the history of Western cinema—Tyrone Power Sr. in The Big Trail (1930), Brian Donlevy in Destry Rides Again, Union Pacific, and Jesse James (all 1939), Jack Palance in Shane (1953), Robert Ryan in The Naked Spur (1953), Henry Brandon in The Searchers (1956), Lee Marvin in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), and Henry Fonda in Once upon a Time in the West (1968), to name but several—Brennan gave two of the very best performances in this category, including his role as the coldhearted Pa Clanton in Clementine. As Roy Bean, Brennan portrays one of the most snakelike of all Western villains—one who is later echoed by Karl Malden, with his venom-soaked charm as Dad Longworth in Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks (1961), and Gene Hackman as Little Bill Daggett in Eastwood's Unforgiven. Despite his moments of displaying humor, affection, and folksy charisma, making it difficult for the viewer to despise him outright, Bean is rotten to the core, and anyone who forgets that basic fact is liable to suffer his wrath at some point.

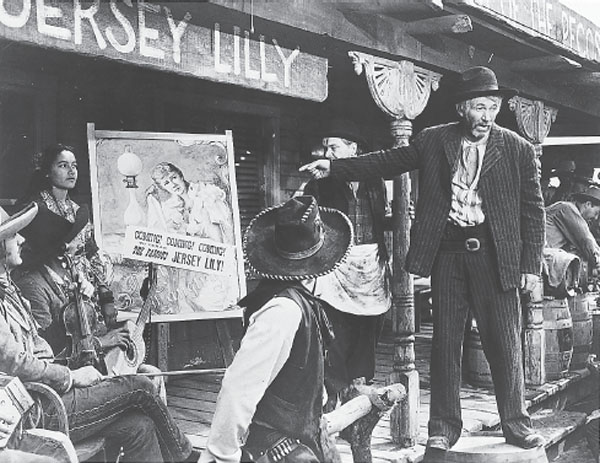

FIGURE 22. Walter Brennan as the ruthless Judge Roy Bean (standing) points to a poster advertising the arrival of his beloved Lily Langtry (“The Jersey Lilly”) in William Wyler's The Westerner (1940). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

But The Westerner is not solely a portrait of Judge Roy Bean. It is, in many ways, a depiction of the primitive politics of the Old West. In his essay “Country Music and the 1939 Western: From Hillbillies to Cowboys,” Peter Stanfield points out that The Westerner is one example of the way in which “the Western was able to negotiate the contradictions and conflicts of what it meant to be an American,” most especially as a reflection of the post-Depression, pre-World War II period in which the movie was made. This is clear, for example, in the overall theme of the conflict between homesteaders, who are dedicated to their agrarian livelihood, and the cattlemen (defended by Bean), who view these migrants and their pursuit of property as a threat to the free ranges on which the cattle can roam and feed. As Stanfield tells us of The Westerner and its place within this wider context:

The Westerner…is not so much concerned with the frontier, as with the establishment and defence of a Jeffersonian pastoral idyll. Gregg Toland's photography manages powerfully to evoke the destruction of homes, families, crops and the ever-present threat to the land, as Judge Roy Bean…does all he can to drive out the homesteaders…. The sense of loss in The Westerner is palpable and the heroine's determination not to give up is every bit as convincing as Scarlett O'Hara's. After the crops and homes have been devastated, we witness a long procession of wagons leaving the territory.27

The economic theme of struggle amid hardship is central in The Westerner, as is the battle between good and evil, themes that would resonate with audience members, who, at the time of the film's release, might have been thinking of the growing war in Europe and the possible external threats to America. The movie is clearly history-minded, with some loose allusions to Wyoming's Johnson County range war of 1892; and Toland's documentary-like shots of homesteaders and cornfields remind one of Depression-era photographs of rural devastation in the Mid-west.28 Yet the film is also laced with mythical moments, both visually and narratively.

The movie begins with majestic shots of a cloud-covered desert appearing beneath the title credits, and in one of these initial shots a silhouetted horseman suddenly appears under Gary Cooper's name. We know right away that this will be the story of an archetypal personality, the type of individual who bravely helped to make the Old West what it was. The solitary figure is “the westerner,” the hero of our tale, and the very title of the film summons us to ponder this type of character. After the credits we turn to the image of a covered-wagon train making its way past the camera. We know from this symbolic shot that the story about to unfold will be set within a larger social situation, in this case that of traveling homesteaders who have braved the threats of the wilderness and of the free-range-protecting cattlemen, all in order to reach their goal of establishing permanent homes at the edge of a constantly shifting frontier.

Words begin to roll down the screen, establishing the historical and biographical contexts that are fused within the wider narrative of the film. After the end of this literary prologue, there emerges a black-and-white map of Texas. The camera zooms in, with the name Pecos clearly visible, and we switch to a shot of cattle being herded. Obstructing the cows are barbed-wire fences that have been erected by the farmers to protect their claimed property. We then see cattlemen cutting the fence wires, and a gun battle erupts between the homesteaders and cattlemen. One farmer runs through the fields, trying to escape a cattleman who has ridden after him. He is captured and taken to meet his punishment; the stage for conflict is set.

We soon find ourselves at the scene of an unfair lynching of the fleeing homesteader. The homesteader who is to be hanged is convicted of “the most serious crime west of the Pecos, to wit, shooting a steer,” and he protests that he had been trying to shoot a man in self-defense and had simply missed. Roy Bean, the presiding judge, responds by blaming the man for being a typical “sodbuster” in that he does not know how to “shoot straight.” The judge then kicks the horse out from under the poor man, who has a noose around his neck. Immediately thereafter Cole Harden is brought into the saloon with his hands tied, accused of stealing one of Bean's men's horses, just before Jane Ellen Matthews arrives to ask after her friend Shad Wilkins (Trevor Bardette), the man who was lynched unjustly. The judge tells Miss Matthews that Wilkins had broken the law: “It's agin' the law to build fences hereabouts.” But she challenges him fearlessly: “What law? Whose law?…You're no more judge than I am. [You] just call yourself a judge.”

Bean is now irritated and orders Miss Matthews to sit down. He then returns to trying Harden and asks that the allegedly stolen horse be brought into the saloon to stand witness to prove if Harden really stole him or not. We now have a real sense of Bean's psychotic parody of a justice system. And yet while one of his men goes outside to retrieve the horse, Bean does express some attempt at “reasonable” discourse when he turns back to Jane Ellen and explains some basic practical logic: homesteaders will not be allowed to build fences and thus hold private property because cattle die when they cannot make it to water. Jane Ellen retorts that there are miles of river on each side of the homesteaders' property and Bean snarls that the land had always been quality free range for cattle grazing: “This country's unfenced range land. Always was and always will be.” Later in the film, after explaining to Harden why he had his men burn the farmers' crops, Bean repeats the argument that the homesteaders must go because the grass needed for the cattle has been ruined. While the movie does not shy away from depicting Bean as a vicious tyrant and his men as obsequious simpletons, the story also makes clear that there are arguments on both sides of the conflict.

After hearing Bean's case for the ranchers, a spirited Jane Ellen then gives a fiery response, proclaiming that no matter what Bean does to the homesteaders, they will keep fighting for what is theirs and what is right. It is the kind of speech in defense of justice that one might expect of Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath. She tells him, “You thought you'd starve the homesteaders out but you didn't. You can pester us and rob us and kill us, but you can't stop us. ’Cause there'll always be more coming, more and more. And we'll stay on our farms in spite of you and your courtrooms and your killers.”

Soon thereafter Harden takes note of Bean's deference to Lily Langtry and the many images of her hanging on the wall behind the bar. Harden deceives Bean by telling him that he has met Lily many times and immediately wins Bean's attention, respect, and curiosity. Harden refers to her as an “angel” and then says that he will never forget the night they met, knowing that he may well satisfy Bean's thirst for more intimate knowledge while not saying so much that he will raise his jealous ire. Bean is enraptured by the story, and Harden adds that he possesses a locket of Lily's hair, knowing how much this will entice Bean. The dazzled judge suggests that Harden could ride to El Paso, where Harden claims to have left the locket, even if it might take weeks for the locket to arrive back to Bean by mail coach. Bean seems to have forgotten that he has already convicted this alleged horse thief, even though his “jury” is still “deliberating” (i.e., drinking and playing cards in the back room). When Bean's men return and deliver the expected verdict of guilty, Bean concurs but states that the sentence shall be suspended for a few weeks until he has time to weigh the evidence further. This puzzles and angers his men, but Bean holds sway and Harden is obviously let off the hook for the time being, his ruse having proved successful.

Toland's genius for cinematography and Daniel Mandell's effective editing are on display when we witness Bean, still suffering a debilitating hangover after drinking heavily all night with Harden, eventually chasing after Harden on horseback. There is rapid crosscutting between shots of the galloping horsemen in order to build a brief burst of suspense. The landscape is prominent throughout the scene, with luminous white and gray clouds towering above a tree-dotted prairie. Elegant bands of darkness and light play off each other as Bean gallops wildly after Harden. In each shot the camera is positioned and pans effectively, sometimes slightly above the rider and sometimes slightly below, creating a quick-moving and almost musical rhythm of visual information. The scene culminates with a crescendo-like convergence of the two men out in the wilderness, beyond the borders of town. But rather than a conventional duel in the sun, we get a conversation—a momentary lull after this heart-pounding chase, in which Harden outwits Bean once again, steals his pistol, and then gallops away.

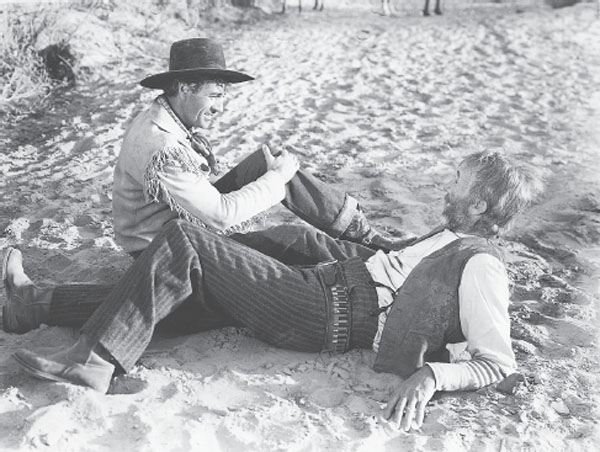

FIGURE 23. Cole Harden (Gary Cooper, left) continues to outwit the villainous Judge Roy Bean after a rousing horse back chase. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

We then cut to a scene of some of the homesteaders in the kitchen of the Matthews's farmhouse. (The actors who play these homesteaders include the young Dana Andrews.) Very few of the men want to fight a war against Bean and his gang, for understandable reasons. Harden soon enters the room, in which he finds Jane Ellen with her dad, Caliphet Matthews (Fred Stone). It is nighttime, and Harden, after appearing suddenly at the kitchen window, enters the kitchen to tell them that he has come to thank Jane Ellen for her assistance in defending him. Harden informs them that he is on his way to California, and they invite him to have dinner with them. As Mr. Matthews says a blessing over the meal, we notice that Harden appears to be out of place, not accustomed to a religious invocation or even to sitting at a dining room table. He is the consummate westerner here, a benevolent outsider who wishes to help innocent community-builders, but who, initially at least, cannot feel at home in such a community and must soon move on.

Harden joins Jane Ellen again in the kitchen after dinner as she washes the dishes. The dialogue here concerns their divergent views on the idea of home, one of the central themes of the movie. She asks him whether he would not prefer to spend more time in some places rather than wandering all the time, and he answers: “It's much like the turtle: carry their houses with ’em. If I had to build a house, I'd have it on wheels.” She responds firmly, “Not me. I'd want my house so that nothing could ever move it, so down deep that an earthquake couldn't shake it and…a cyclone would be just another wind goin' by.”

FIGURE 24. Cole Harden and Jane Ellen Matthews (Doris Davenport) ponder the landscape and a future together in a romantic scene from The Westerner. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Our protagonist decides against leaving and becomes committed to the cause of helping the homesteaders in their fight against Bean. A bit later on, Cole and Jane Ellen continue their discussion about the importance of a permanent home, just after the homesteaders are shown kneeling in front of the vast field of cornstalks and giving their benediction and thanksgiving. Jane Ellen follows in the footsteps of such strong-willed Western women as Letty Mason in The Wind (see chapter 2) and Dallas in Stagecoach (see chapter 4); for all three characters, a stable home and family life amid the frontier wilderness is their light at the end of the tunnel. In his book From Shane to Kill Bill: Re-thinking the Western, Patrick McGee compares Jane Ellen with Dallas, as well as with the spirited Frenchy (Marlene Dietrich) of Destry Rides Again. According to McGee, while Jane Ellen may be more traditional and less charismatic than the other two female westerners, she is the perfect heroine for post-Depression era audience members who had also recently been forced to realize, more than ever, the value of a secure home and income, not to mention the value of a strong female presence.29

A celebration with music and dancing follows the blessing of the crops, reminding us of similar communal celebrations in Ford's The Grapes of Wrath, My Darling Clementine, and Wagon Master. Close-ups and long shots of people and cornstalks are alternated with images of a cloud-filled sky stretched above them as a visual manifestation of the deity to whom they pray. It is a scene that stresses the centrality of land and community in the overall narrative of the settling of the Old West. As the music of the thanksgiving celebration begins, Cole and Jane Ellen stroll beyond the outskirts of the cornfields. She points out a stretch of land below their hilltop perch and declares: “Look, Cole—the best piece of homestead land in all the country. It used to belong to one of the hired men that left us and now it's anybody's. You just claim it.” She glances at him in a way that suggests she is drawing an intentional parallel between herself and the land, indicating that he can “claim” her if he would like to do so.

She asks whether he knows how to “build a home,” and he does not disappoint her, moving to sit on a nearby log and then describing the design of his imaginary house. Predictably, they kiss passionately. But then, in the film's sudden turn from optimistic romance to destructive tragedy, Cole notices that the crops in the distance behind them are on fire. We see Bean's men dragging piles of burning brush along the perimeter of the cornfields as the homesteaders quickly notice the flames in the distance and scramble to respond. Harden now feels that he must eventually confront Bean in a showdown: any chance for rational negotiation has proven futile.

The crop-burning scene is a suspenseful fusion of rapid-fire crosscutting, masterful camera framing, and memorable visual effects—the latter involving the work of Archie Stout, who would demonstrate his own highly nuanced cinematography in Ford's Fort Apache (1948). In the background we see flames reach for the heavens as homesteaders in the foreground are interrupted from their celebration and turn to face the sudden horror. We witness Bean's men on horseback, trampling over Jane Ellen's father, who had just stepped before them with his arms raised in utter rage at the evil that is being enacted. We see Harden riding frantically and calling out after his beloved, but he pauses momentarily to watch as homesteaders run desperately for safety while buildings burn to the ground. There are echoes here of the fiery ending of William Hart's Hell's Hinges (see chapter 1). Peter Stanfield remarks on this scene when contrasting the movie's way of presenting the conflict between settlers and ranchers with that of George Stevens's later classic Shane: “Shane, in its highly affected self-reflexivity, doesn't give the same weight to the issue of farming and land that The Westerner does, instead displacing the audience's attention more firmly onto the hero. And the scenes of destruction wrought by the cattlemen on the land are nothing compared to the apocalyptic vision that Gregg Toland's camera creates.”30

Harden knows that he must eventually kill Bean in order to obtain the settled life that he now desires. He is a man who realizes what it takes to live in a better world, one in which reliance on another person is necessary, and he is willing to use bullets rather than bluster only when words will no longer persuade. Anticipating Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, released twenty-two years after The Westerner, Wyler's film gives us in Harden a unique precursor to Ransom Stoddard, the idealistic lawyer who seeks to overcome violence diplomatically but who eventually learns that justice must be backed with the threat of bullets (see chapter 8). Harden embodies the necessary transition, one spelled out so clearly in Ford's later film, between wilderness and garden.