CHAPTER 1

Diverse Perspectives in Silent Westerns

Landscape, Morality, and the Native American

The movie “oater” was born during the last decade of the nineteenth century, as the world of cinema was first emerging and around the time that the American West was closing its final frontiers. In the decades between the Civil War and World War I, by which time the territories of Arizona and New Mexico had been granted statehood, the nation could savor a nostalgia for a fading frontier while hearing news of the actual dangers of its concluding scenes. One could traverse the continent on the Southern Pacific in the 1880s, riding through territory not far from where the escaped Apache leader Geronimo was holed up in the Chiricahua Mountains. Or one could read of daring journeys, thanks to the new publication venture of inexpensive paperbacks known as dime novels, which had appeared as early as the 1860s in a series brought out by Erastus Beadle, appealing to a mass audience eager to enjoy adventures of outlaws and cowboys. Edward Judson, who wrote under the pen name Ned Buntline, was the best-known dime novelist. On the stage, a national celebration of the taming of the wilderness was initiated in the 1880s, in typical American style, as a form of highly successful commercial exploitation by some of those who had played key roles at historic moments. William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, a former chief scout for the U.S. Cavalry, famously launched the story of the Wild West as a form of live spectacle that included representations of Custer's Last Stand and appearances by Sitting Bull.

Live spectacle soon became filmed spectacle. American history and the American cinema were inevitably fused, especially when it came to depictions of the post-Civil War Old West. Among early film documentaries were Edison's 1894 recordings of reenacted scenes from Buffalo Bill's Wild West show, including quick glimpses of a Native American buffalo dance, a sharpshooting demonstration by Annie Oakley, and in the case of Bucking Broncho, a cowboy's horse-riding demonstration before a group of entertained spectators. In 1902 the popularity of the Western surged with a novel about a lonesome cowboy, The Virginian, by Owen Wister. It became an instant best seller, and this was followed in 1903 by Edwin S. Porter's movie The Great Train Robbery. Shot at Edison's New York studio and in New Jersey along the Lackawanna Railway, the eleven-minute-film created an illusion of reality. A violent robbery takes place aboard a seemingly moving train, an effect created by intercutting studio shots with matte shots of the passing landscape, the exteriors of the moving train, and later the escape and chase of the robbers. The shot of a gunman firing directly at the audience, the bright colors tinting the puffs of gun smoke, and the strongbox's explosion all added to the film's broad appeal.

The year 1904 witnessed the release of Biograph's Cowboy Justice, along with Edison shorts such as Brush between Cowboys and Indians, Western Stage Coach Hold Up, and The Little Train Robbery, a follow-up parody of the film company's earlier success. These early silent productions contained many of the elements that would be repeated throughout Western movies for decades to come: bold adventure, broad humor, impressive horse riding, outdoor-location shooting, and violent conflicts.1 By 1909, the genre had come to dominate the American film market, and Western films were being produced in great numbers to satisfy public demand. In his informative book Shooting Cowboys and Indians: Silent Western Films, American Culture, and the Birth of Hollywood, Andrew Brodie Smith details the process by which early Western movie production in the silent era helped to establish cinema's white male hero, contributed strongly to the development of the American film industry, and led to the founding of that industry's future “headquarters” in Los Angeles2

With increasing advances in film technology came new creative possibilities in depicting more complex storylines. Movie companies such as Biograph, Pathé, Essanay, Kalem, Bison, and Selig produced many of the genre's pioneering one-reelers and multireelers in the first two decades of the twentieth century. The best of these motion pictures, and most especially those made by D. W. Griffith for Biograph between 1908 and 1913, helped to establish the Western film as a specific form of visual and narrative art, at least for those who could see beyond the “mere” value of these films as recurring vehicles of public entertainment. Griffith regularly utilized cinematic techniques—such as dramatic camera angles and crosscutting between parallel scenes for purposes of suspense-building—that helped to advance the new art form.

Griffith's early Westerns, made between 1908 and 1909, were shot chiefly in New York and New Jersey and used the wooded river and lake country of the East Coast as a substitute for Western landscapes. The lush eastern countryside offered serene settings, in which the Native American is presented positively and not merely as some antagonistic “savage.” As Scott Simmon has suggested in his book The Invention of the Western Film, the idyllic presentation of the landscape in these films echoes an appreciation of the Native Americans, who were connected more intimately to the natural world than the white settlers were. The presentation of a tranquil landscape echoes symbolically the idea of a general “natural harmony” that exists (or should exist) between humans and nature, as well as between various human beings, whether “red” or “white.”3

The Biograph Company produced enough early movies about Native American life that their own promotional reviews and plot summaries, called Biograph Bulletins, began to refer to the narrative subject matter as a well-established category of film. The bulletin for Griffith's “East Coast Western” The Mended Lute (1909) leads off with the following statement: “Moving Picture Stories based on the life and customs of the American aboriginals have ever been attractive, and we conscientiously doubt if there has ever been a more intensely interesting subject matter presented than this Biograph production.”4 The bulletin for Griffith's The Redman's View (1909) begins with this declaration: “The subject of the Redman's persecution has been so often the theme of story that it would appear an extreme exposition of egotism to say that this production is unique and novel, but such is the case, for there was never before presented a more beautiful depiction of the trials of the early Indians than this.”5

The Mended Lute focuses on the rituals and values of Native American life, with its plot centered on the rivalry between Standing Rock and Little Bear for the hand of Rising Moon. Standing Rock, Rising Moon's “rich” suitor, is favored by her father because of his potential dowry. The film ends with a ritual test of courage involving torture, in which Standing Rock binds Little Bear and slices his chest with a knife. Little Bear passes the test and earns the respect of Standing Rock, allowing Little Bear and Rising Moon to run off to a “land of happiness” (as the final title card reads). There is also effective use made of the natural landscape, particularly the impressive shots of canoes gliding down streams and rivers. The movie, subtitled A Stirring Romance of the Dakotas, was deemed a “master-piece” by the Biograph Bulletin, which also called the film a “combination of poetical romance and dramatic intensity.”6

Griffith's The Redman's View shows a similar though predictably limited appreciation of indigenous life, expressed primitively by the very title of the movie. Here we are introduced to a young Indian couple in love, but when the white men (called “the Conquerors” in the title card) invade their lives, the young man is forced to make a choice between, on the one hand, staying with his beloved and protecting her and, on the other, caring for his father on their long trek after they have been banished from their home by the whites. Eventually the father dies and his body is placed on a pyre in ritual fashion. The young man returns to reclaim his girl from the white men who had taken her captive. Here the white men, not the “Injuns,” are the disruptive savages.

The Redman's View expresses a tension between the initially idyllic, seemingly authentic view of native life and the subsequent threats against that life in the form of white civilization. As Armando José Prats observes in his book Invisible Natives: Myth and Identity in the American Western, it would appear that Griffith offers us an explicit contrast between two perspectives, each of which seems to possess its own independent integrity and historical truth: the opening scenes of Indian life, soon followed by a depiction of that existence as endangered and embattled by another culture. In reality, according to Prats, both views are actually subsumed under the “myth of conquest,” so that any appearance of a distinct portrait and honest appreciation of the Native Americans, even by way of contrast, is mere illusion. As he tells us in reference to Griffith's film and its opening sequence:

When The Redman's View produces its first shot of the conquerors, it transforms the significance of the opening scenes (the Indian idyll) to produce something like Parkman's image of an unsuspecting culture about to be crushed by empire's relentless march. Thus “the red man's view” designates not a scene from a culturally independent way of life but a dialectical response to history's intrusion in the ahistorical scene. The camera, it turns out, though it witnessed the opening idyll, never gave us the Indian's “view” but rather the view of the Indian, and its presence in the village initiated the dialectical process whereby Conquest could be introduced only so that it might be thereafter condemned.7

The “redman's view” in the film's opening sequences is, in other words, defined by the overall narrative and its implicit ideology, one typical of the Western genre and its underlying mythos. The Indians, even when shown in their native setting before any signs of conflict arise, are inevitably the waiting victims of American expansionism and must confront enemies who are the necessary vehicles of Manifest Destiny. Any such perspective that pretends to depict native existence apart from the story of their gradual conquest is a false or at least derivative viewpoint, according to Prats's interpretation. And so the depiction of the Native American in certain scenes of these early silent films, especially those made by Griffith in his East Coast productions, is ultimately anti-idyllic in its overall framing of a people on the verge of conflict and eventual genocide—particularly in light of our retrospective historical knowledge and, of course, given the unfolding of the overall narrative.

The plots of some of Griffith's early silent Westerns present the relationship between the white man and the Native American in terms of this kind of tension and so with a degree of moral ambivalence. To take another example, in The Broken Doll (1910), the whites are presented as both kind and cruel to the natives, though in very different contexts. On the one hand, a white girl, at the suggestion of her mother, gives her beloved doll to a young Indian child who admires it, and the two girls hug and kiss. On the other hand, a small group of Indian men visits town, and one of them accidentally bumps into a drunken white man who has just stood up after sitting in front of the saloon. The white man shoots him dead on the main street, and the Indian's shocked friends bring his corpse back to their village of tents. Subsequently, they go on the warpath to avenge the man's unjust death. Meanwhile, the chief discovers his daughter's new doll and throws it away. The daughter runs to get the doll, finds its head broken off, and decides to give the doll a proper burial. She subsequently becomes aware of the impending attack by her tribe and runs off to warn her new friend and her family. The Indians travel to town to wage destruction, while the white girl's father goes to town ahead of them and warns the townspeople of the impending “invasion.” They manage to scare off the Indians, later praising the young Indian girl for her warning once they have learned of her action. But when the white men fire on the attackers, the girl is accidentally shot. She tries to stumble back home, but in a tragic and sympathetic ending, she dies near the doll that she had previously “put to rest.”

This type of ambivalence in presenting the white man's relationship with the Native American is echoed in later multireel silent Westerns such as The Invaders (1912) and The Covered Wagon (1923). The former movie, produced by Thomas Ince, is a three-reel film that uses genuine Native American actors, a casting idea that was too seldom revisited in later Hollywood Westerns. The film depicts the battle between the United States Cavalry on one side and Sioux and Cheyenne warriors on the other, devoting substantial attention to details about the everyday lives of the Indians and not solely focusing on action fights or glimpses of cavalry existence. Francis Ford, older brother of director John Ford and a pioneering filmmaker in his own right, portrays the leading officer of the cavalry. It is more than probable that Ford, as with other Ince productions in which he acted, took a hand in the directing of the movie under Ince's supervision.

In the opening scene of The Invaders, Ford's character oversees the signing of a peace treaty between the government and the Sioux. The treaty expectedly turns out to be a temporary agreement of convenience for the expansionist whites, especially considering their plans to extend the railroad through the Indian territories, land that is supposed to remain off limits by virtue of the treaty. The initial scene presents a peaceful gathering of former enemies, a gathering that ends with an apparently happy handshake. And given the fact that the film presents the perspective of the Native American, focuses sympathetically on the heroic daughter of the Sioux chief and her love for a white man, and emphasizes the violent consequences of the railroad surveyors' treaty-breaking, the viewer is led to realize that it is the white “conquerors,” not the “noble savages,” who are the invaders of the film's title.8

Both sides of the conflict between red and white, even if subsumed by the wider myth of conquest, are also considered in James Cruze's The Covered Wagon (1923). This movie was wildly popular, making possible John Ford's production of his saga about building the transcontinental railroad, The Iron Horse, a year later, since it was now demonstrated that an historical epic about the labors and trials of American expansionism could win over audiences. Cruze's film ambitiously reconstructs the experience of a great migration of pioneers from the Missouri River to Oregon and anticipates later wagon train movies like Walsh's The Big Trail (1930) and Ford's Wagon Master (1950). Driving the story is the conflict between the settlers and the gold-seekers, for this tale is set in 1848, when gold was discovered in California. The travelers are split between their greed for land—in their Jeffersonian aim to establish an agriculturally self-sustaining territory—and their greed for the gold that would enable the creation of a potential urban environment based on trade and industry.

The treatment of Indians in The Covered Wagon is ambivalent, and the native perspective, as Prats has observed about such films, is defined by, dependent on, and thereby at least partially distorted by the overall story of American expansionism. An intertitle gives the Indian's point of view regarding the white man's plow: “With him he brings this monster that will bury the buffalo, uproot the forest and level the mountain.” The natives are initially shown trying to earn money by helping to bring the wagon train, at ten dollars a wagon, across the river, but the pioneers refuse as they think the cost is too high. Once they have crossed the water, the villain of the film, Sam Woodhull (Alan Hale), confronts an Indian, calls him a “thieving savage,” and shoots him dead. We find out a short time later from Woodhull, who barely survives an attack by the Pawnees, that the Indians have killed his own party. But then other men from the wagon train learn that this attack was an act of retribution provoked by Woodhull's earlier killing. One of the men reports that Woodhull must have done something “tricky” to provoke the attack, since the Indians had appeared harmless. So here we see the Indians as fierce aggressors, but only after being provoked by a villainous white troublemaker.

This kind of dual-edged appreciation for the perspective of the Native American is undercut to some degree by the overall sense of progress and historical necessity that is central to the underlying myth of civilization-building. However limited such an appreciation of Indian life may be, it is echoed by a few later silent Westerns of the 1920s. These include The Vanishing American (1925), directed by George B. Seitz and based on a novel by Zane Grey, and Redskin (1929), directed by Victor Schertzinger. Both movies starred Richard Dix, an athletic white actor whose rugged physical appearance and stoic facial expressions made him halfway credible (in the eyes of producers and audiences) in portraying an Indian. The Vanishing American depicts injustices suffered by Indians at the hands of a sadistic reservation agent. Dix's character eventually escapes from the cruel life of the reservation and later evolves into a hero on the battlefield in World War I. The film also starts off with a broad-ranging historical prologue that traces the history of past injustices suffered by “weaker” races and peoples. But this prologue winds up espousing a principle of Darwinist determinism—and so “the weak” must accept that they will simply perish in the end, a principle that undercuts the otherwise sympathetic subject matter.9 In Redskin, Dix plays Wing Foot, who is taken away from his community as a young boy and forcibly educated in a government-run school for young Indians. He eventually comes to recognize that he will never really belong in the white community, and he returns to his reservation, only to face severe criticism from his father, among others. The movie is unique for being a late silent Western that focuses on Wing Foot's perspective throughout, but it ultimately advocates the idea that different peoples should remain separate. Moral ambivalence once again saturates the narrative.

The cinematic portrayal of the Native American changed over the years since Griffith's earliest Westerns, but so did the portrayal of the Western landscape, even within Griffith's own oeuvre. In early 1910, Griffith and his Biograph team, including chief cameraman G. W. “Billy” Bitzer, began wintering out West so as to shoot in sunnier climes when the weather hampered production back East. At that time the natural landscape depicted in these post-1910 films became more authentically Western, with vast empty desert places replacing northeastern lakes and forests. The move to capture a new type of setting that was closer to the reality of the American West may have also been, as Simmon suggests in The Invention of the Western Film, a response to the criticisms of some movie reviewers that the traditional silent Western film up until 1910 had become little more than an overworked cliché, with minimal innovation in terms of both narrative and setting. The move may have also been a reaction by American film companies to stiff competition with European movie companies who were making their own outdoor adventure movies. The American filmmakers may have sought a more indigenous setting that could not be easily imitated by the Europeans.10 As Western film expert Edward Buscombe has observed:

From the early days of the last century, Westerns have used landscape to ensure authenticity. Indeed, in the period before World War I, when American cinema was faced, for the only time in its history, with fierce foreign competition in its domestic market, the Rocky Mountains and the deserts of the southwest gave the American Western film a “unique selling point” as compared to the Westerns being made in Europe and the eastern United States by the French Pathé company.…Deserts particularly were favoured. Europe too had mountains (and would use them to considerable effect in the Westerns produced in both West and East Germany during the 1960s), but it had no deserts and canyons to rival the spectacular sights of Arizona and Utah (even though Sergio Leone shot his Dollars trilogy in the arid country around Almeria in Spain).11

Simmon proposes convincingly that the move to a more authentic Western setting also presented creative challenges to silent filmmakers such as Griffith. The primary challenge was to “fill” or “master” the bleak empty desert places that had replaced lakesides and forest-framed clearings. The natural choice was to shape this kind of cinematic space, otherwise unpopulated, around highly charged action and dramatic conflict.12 Action and conflict could easily be drawn from the actual history of the American West as presented by writers such as Francis Parkman (France and England in North America) and Theodore Roosevelt (The Winning of the West).13 And so these kinds of scenes engendered a new narrative focus, one that was unlike the “East Coast Westerns” that Griffith and others made before 1911. The newer Westerns emphasized battles between cowboys and “Injuns” and, within white society, between heroes and villains. Such battles were typically waged over unclaimed land that was waiting to be conquered and controlled and cultivated, precisely the type of empty landscape that was the backdrop of these more action-packed Westerns shot in the Southwest, chiefly in California.

Griffith's Westerns subsequently adopted the view of the Indian as a figure of fierce savagery, the primitive enemy of white civilization and the chief obstacle (aside from nature itself) to American expansionism, as evident in his final Western for Biograph, The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (also known by the title The Battle at Elderbush Gulch;1913). Its Biograph Bulletin states that this film is “unquestionably the greatest two reel picture ever produced,”14 and it features such silent-era luminaries as Mae Marsh, Lillian Gish, Lionel Barrymore, Henry Walthall, and Harry Carey Sr. The film has plenty of action, including a rousing fight between Indians and townspeople, plus a good deal of engaging sentimentality. As Prats tells us, “Aside from its formal accomplishments and from whatever importance it may have had in the development of D. W. Griffith's career, The Battle at Elderbush Gulch merits close attention for the way in which it charts the direction of the Indian Western. Perhaps more than any other single silent short, it determines and develops the dominant perspective of the Myth of Conquest.”15

Two young orphan girls are brought to live with their uncle at his ranch, but the ranch boss tells them that they cannot keep their two little puppy dogs. The older girl must retrieve the dogs, but she soon discovers that the animals have run away and are now in the possession of two Indians who are returning to their village to enjoy, of all things, a dog-eating feast. Their uncle goes out in search of his niece and, seeing her in the presence of the Indians, shoots at them, killing the chieftain's son and prompting an Indian attack. In one suspenseful sequence, the older girl sneaks out a small trapdoor of the cabin during the violent fighting to rescue a baby who has been crying outside. She saves the baby and deposits it in the trunk below her bed. An endearing subsequent shot shows the two girls, the baby, and the two puppies all peering out of the trunk once the fighting has stopped. Gish's character is overjoyed to find that her baby has been saved.

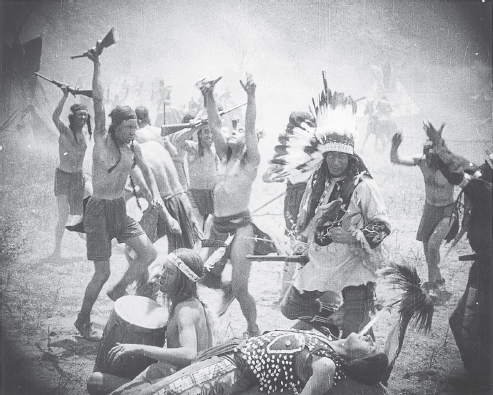

FIGURE 1. Indians angrily mourn their murdered comrade in D. W. Griffith's The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (1913). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

In its demonization of the Native American and its focus on the violent conflict between the “savage” and the “civilized,” The Battle of Elderbush Gulch echoes Thomas Ince's production Custer's Last Fight (1912) starring Francis Ford. The film shows us the Sioux and Cheyenne making hostile attacks in response to an encroaching white civilization. Custer's Last Fight makes clear that the Indians are to blame for the ensuing violence. Rain-in-the-Face seeks to ensure his reputation as a Sioux warrior by attacking the whites. He boasts of killing two civilians, and as we soon learn, this inspires the Native Americans in the region to draw into “nations” to attack the whites. The leader of the Standing Rock Indian agency sends for someone to arrest Rain-in-the-Face, and orders are sent to Fort Abraham Lincoln, where George Armstrong Custer (Ford) is stationed. An order arrives from Washington for Sitting Bull, the leader of this region's Indian nations, to surrender to an escort. Sitting Bull defies this order, and so Custer and the Seventh Cavalry are ordered to join General Terry's army in defeating Sitting Bull. While the Indians attack in response to the encroachment of white civilization, we learn that it is Rain-in-the-Face's need to boast of killing whites that prompts the Indian attacks and the ensuing battle.

FIGURE 2. Lillian Gish's character (center) rejoices at the rescue of her child after a battle with Indians in The Battle of Elderbush Gulch. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Moral complexity or ambivalence becomes inevitable in depicting a historical period in which violence against the enemy was sometimes initiated by an ever expanding white civilization, often in the name of Manifest Destiny, and sometimes initiated by the increasingly frustrated and decimated victims of that expansionism. The continent was not big enough, seemingly, for the whites to tolerate the existence of Indian peoples, nor was it large enough for the latter to tolerate a fast-growing nation. The only solution, as we can learn from the story of the Old West, lay in bloodshed and massacre. But a civilization or culture that is willing to vanquish and eliminate other peoples in acts of genocide undertaken for the sake of territorial expansion is never devoid of its own internal moral conflicts. And the Western genre has been dominated as much by tales of white frontiersmen warring against one another in the name of “good” and “evil” (usually in the form of gunslinging showdowns) as by confrontations with the “savage” warrior who is already native to the land.

HELL'S HINGES AND CONFLICTS BETWEEN WHITE WESTERNERS

Examples of early Griffith Westerns that were shot out West and that deal mainly with the morality of “white culture,” with little or no reference to Native Americans, include In the Days of' 49 (1911) and Under Burning Skies (1912). In the first of these, subtitled An Episode in the Times of Gold Fever, a man named Bill (George Nichols) strikes gold and sends a message back home for his wife, Edith (Claire McDowell), to join him. Traveling by stagecoach, Edith meets a gambler called Handsome Jack (Dell Henderson), and they find themselves mutually attracted. But Jack discovers that she is married. Meanwhile, Bill awaits his wife's arrival. After meeting up with her husband again, Edith seems disappointed with Bill now that she has met Jack, who meets with her privately and tells her to join him soon so he can take her away. Bill soon realizes (as announced by title card): “My wife doesn't love me.” The theme of conscience soon emerges, as it does in many of these early Western morality tales that focus almost solely on the internal tensions between members of frontier society. An intertitle proclaims: “Jack realizes the great wrong he is working.” Jack eventually departs, having undergone a dramatic transformation of character, and he writes a letter to Edith telling her not to be a fool, to appreciate what she has, and to return to her husband.

In Under Burning Skies, a problematic romance and a sudden moral transformation once again become central themes. A rivalry breaks out over Emily (Blanche Sweet) between a sober good man (Christy Cabanne) and a drunken “bad guy” named Joe (Wilfred Lucas), both of whom desire her. Joe swears off alcohol and his immoral lifestyle for the sake of the girl, but only for a moment, since he quickly returns to his old ways. Griffith uses his trademark method of suspenseful cross-cutting as the men hunt for each other with their guns drawn. Emily is alerted to the impending gunfight, and she runs to put herself between the two men who have almost reached each other at the corner of a building. The good guy gets to marry the girl, and Joe goes to drown his sorrows in liquor. When Joe discovers that they have left town with their mule, he vows vengeance and follows them out into the desert, still inebriated. We then witness the couple dying of thirst, with Emily becoming faint and her new husband becoming delirious. Joe happens upon them, laughs vengefully, and taunts them with his canteen of water. He prepares to leave but ultimately changes his mind, revealing a lightning-quick reversal of character that borders on the ludicrous. But it is the type of personal metamorphosis that will later become a staple theme in the films of the Western actor and director William S. Hart, not to mention many later Westerns in general. The couple is saved and Joe (now “good”) stumbles off into the desert, the rapid flux of human life having been played out against a fairly static landscape.

The focus on white westerners and their moral transformations is amplified by Hell's Hinges (1916), produced by Thomas Ince but almost certainly directed for the most part by its star, Hart, with some nominal credit given to Charles Swickard.16 In many ways, the film revolves around the theme of passion and its capacity to change the character of an individual. Blaze Tracy (Hart) falls head over heels in love with Faith (Clara Williams), the devoted sister of the Reverend Bob Henley (Jack Standing). Blaze, at first presented as an antihero, “becomes good,” like many a “good bad man” in Westerns, in this case because of Faith's example and Tracy's love for her.

As the symbolic embodiment of passion as well as compassion, the traditional cowboy hero may be compared with the medieval knight who undertakes self-transforming journeys and adventures, adhering to some code of chivalry. In many cases each gains a sense of moral self-improvement through his love of a beautiful maiden whom he wants to serve. This theme is certainly a hallmark of many of Hart's Westerns, including Hell's Hinges. Viewed in a far broader perspective, it is a theme illustrated throughout the literature of the later medieval period, as well as in the symbolic fiction of Romanticism. This theme is represented most famously, perhaps, in Dante's La Vita Nuova. Dante's love of his beloved Beatrice gives him a higher sense of purpose and a feeling of fulfillment, and the hero of Hell's Hinges follows a similar self-enlightening pathway to a significant degree.17 As Charles Silver tells us in his book The Western Film: “William S. Hart was, more than anything, the reincarnation of the chivalrous spirit of the Middle Ages, and his films are visual hell-fire sermons, soul-saving morality plays.”18

But the film also presents us with the negative effects of passion, and so the lesson here about the possible intersection between passion and virtue is a qualified one. Faith's brother becomes a moral degenerate through his spirited lust for the ladies, and most especially when he is in the presence of prostitutes and dance-hall girls while full of liquor. One early intertitle announces with irony: “His [the Reverend Henley's] Imagination. A mission appealing to his sense of romance.” Here he has a brief daydream of beautiful women congregating around him while outside of a church, tempting his inner desires. After this dream, the corrupt pastor is then assigned to a mission on the prairie, as his superiors know that he is prone to fall for women in his parish and that he needs to be sent somewhere “safe” to redeem himself. The conjoined themes of temptation, sin, virtue, and spirituality emerge clearly.

The Reverend Henley and his sister, Faith, travel by stagecoach to his newly assigned township in the Old West. Shots of hillsides and barren countryside are interspersed with shots of Hell's Hinges, a violent town where men are shot in the street. The majority of townspeople are blatant sinners, but there are a handful of decent and religious people (“the petticoat league,” as they are labeled by the others) in this “sin-ridden town.” These believers await the arrival of their new preacher, and we witness the minister's first church meeting, which is held in a barn functioning as a church. The townies ride in to start trouble during the service, but Blaze Tracy, previously established as a fellow sinner who scoffs at morality and religion, rides to the rescue when he is told of what is going on. We recognize that he has seeds of virtue in his heart.

After we see the new minister's sister praying during the church service, the film cuts to the image of a large stone cross by the ocean, a symbol that (along with her name) expresses her deep spiritual conviction. Faith asks if there is anyone who will heed her call in the face of the ridiculing townspeople who are there to stir up trouble for the churchgoers and the new preacher. The corresponding intertitles are presented against a painted backdrop of radiant sunrays, with clouds and a tiny cross in the background. Blaze responds quickly to Faith's prayers, and we witness how her virtue and spirituality help to instill in Blaze a desire for the same, leading to his gradual transformation. The obvious connection between virtue and faith can also be related to such religious-themed Westerns as James Edward Grant's Angel and the Badman (1947), with John Wayne and Gail Russell, as well as John Ford's Wagon Master and 3 Godfathers (the latter based on a Peter Kyne story, whose other film versions include Ford's early silent Marked Men of 1919 and William Wyler's Hell's Heroes of 1930).

FIGURE 3. Hell's Hinges (1916): Blaze Tracy (William S. Hart, right) reacts to Faith Henley (Clara Williams, center, with hand outstretched) while her brother, the Reverend Bob Henley (Jack Standing, to left of his sister), and other townspeople look on. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The members of the oppressed congregation go about building a real church. Meanwhile, villainous saloon owner Silk Miller (Alfred Hollingsworth), Blaze's former friend and someone who wants to make sure that religion and law never come to Hell's Hinges (as one intertitle informs us), asks one of the dance-hall girls to get the minister drunk and to sleep with him so that the townspeople will witness his sinfulness and lose faith in him. When a gathered crowd discovers Henley sleeping off his hangover the next morning with the dance-hall girl on his bunk, Silk tells his old friend: “He's like all the rest of ’em, Blaze; a low down hypocrite and liar. There ain't no such thing as real religion.” Blaze then compares the morally weak preacher with a steer that you cannot depend on if it breaks free and goes wild. The film thus draws a sharp distinction between “real religion”—that of Faith and the other churchgoers—and “false religion”—that of the Reverend Henley, who merely mouths the words but does not truly believe in them.

Soon the minister revels in his degeneracy, shoving a woman and drinking with the saloon patrons, part of the wild crowd. One of the saloon drinkers shouts, “To hell with the church! Let's burn her down!” They choose the parson, now intoxicated again, to strike the first match. The churchgoers fight to save their house of worship, the Reverend Henley is shot in the melee, and the barn is shown burning along with a wooden cross on the roof. Blaze sees the flames and smoke in the distance and rides to save Faith, who now holds her dead brother in her arms. Blaze goes to the saloon and shoots his pistol at the closed door where, in a fairly ridiculous cut, the door is instantly broken off its hinges by the bullet and the many saloon patrons exit with their hands up in surrender. Blaze shoots a ceiling lantern to the floor, and as the building begins to burn down, he allows the saloon patrons to leave. If the church is to be destroyed, this house of sin will be, too. We now witness a series of apocalyptic images of the town in flames and smoke, a symbol of the negative effects of fiery passion, while Blaze returns to fetch Faith. They depart, carrying away Henley's body.

There are remarkable landscape shots at the end—including a fiery sunrise and a majestic canyon—and these images symbolize the positive power of passion, that of genuine love conjoined with virtue. Blaze and Faith are shown at the grave of the minister with a primitive wooden cross visible on a nearby hillside. Blaze embraces his girl against a misty ravine and he tells her: “Over yonder hills is the future—both yours and mine. It's callin', and I reckon we'd better go.” The final intertitle reads: “Whatever the future, theirs to share together.” Like many a later Western film, Hell's Hinges demonstrates that the Western myth is often founded on a dialectical tension between tragic loss and optimistic faith.

The authentic look of Hart's Westerns, and the ethical awakening of his protagonists, set the stage for such Western classics as Hawks's Red River, Ford's The Searchers, and Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales. While Hart did not share the folksy charm of silent Western star Harry Carey Sr., his quiet dignity and tight-lipped stoicism paved the road for Western actors such as Henry Fonda, Randolph Scott, and Eastwood. And Hart's appreciation of the variability of human nature, and of our opportunities for moral self-transformation, emphasizes one of the primary themes at the heart of the genre: the transience of life as played out against the seemingly eternal world of nature that lies beyond us.

FORD'S STRAIGHT SHOOTING

As the preeminent director of Western films in the twentieth century, John Ford had been influenced by the personal styles of William S. Hart and Harry Carey Sr. But his early artistry had been shaped most of all by D. W. Griffith and Ford's older brother Francis. When asked by Peter Bogdanovich, “Who were your early influences?” Ford replied:

Well, my brother Frank [Francis]. He was a great cameraman—there's nothing they're doing today—all these things that are supposed to be so new—that he hadn't done; he was really a good artist.…Oh, D. W. Griffith influenced all of us. If it weren't for Griffith, we'd probably still be in the infantile phase of motion pictures. He started it all—he invented the close-up and a lot of things nobody had thought of doing before. Griffith was the one who made it an art—if you can call it an art—but at least he made it something worthwhile.19

John Ford's Western oeuvre illustrates through its unity-amid-diversity the three major strands of storytelling we have explored so far: the violent conflicts between reds and whites (Stagecoach, Fort Apache, and The Searchers, for example), the conflicts within white culture in the Old West (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, Wagon Master, and Sergeant Rutledge, for instance), and even the sympathetic portrayal of the Native American perspective in the face of an expansionist United States government (Cheyenne Autumn).

Ford directed Straight Shooting in 1917. An adventure comedy, the film reveals the young Ford's already mature sense of visual style and narrative drive, his skill at connecting to his audience both intimately and on a rousing grand scale, his rhythmic intertwining of comedy and sorrow, and, in close collaboration with Harry Carey Sr., his creation of a strong, independent, lonesome cowboy. Its assured rhythms and narrative pace, developed characters, depth of emotion, and superior location-shooting reveal a strong sensibility for and accomplished handling of the genre.

John Ford came to California in 1914, and he later claimed to have played a clansman in Griffith's The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Francis had been directing two-reelers and serials at Universal, and “Jack” (as he was then known) became his brother's chief assistant and occasional cameraman, actor, writer, and even stuntman. He subsequently directed nine films on his own between March and December of 1917. All but the first, The Tornado, were Westerns. With The Soul Herder, Ford teamed with Harry Carey Sr. and Hoot Gibson, and in August he directed his first feature-length Western, Straight Shooting, the third of twenty-five films he would make with Carey. Ford was then twenty-three years old.

Straight Shooting is a standard struggle between ranchers and farmers for control of water. By 1915, when Francis Ford made Three Bad Men and a Girl, Universal was turning out more than half a dozen Westerns each week. Carey was an experienced movie actor, first at Biograph where he often played a villain or decent-hearted outlaw, then at Universal starting in 1915. His career had stalled, as John Ford recalled to Bogdanovich:

They needed somebody to direct a cheap picture of no consequence with Harry Carey, whose contract was running out.…I knew Harry very well and admired him; I told him this idea I had and he said, “That's good, let's make it.” I said, “Well, we haven't a typewriter,” and he said, “Oh, hell, we don't need that, we can make it up as we go along.” These early Westerns weren't shoot-'em-ups, they were character stories. Carey was a great actor, and we didn't dress him up like the cowboys you see on TV—all dolled up. There were numerous Western stars around that time—Mix and Hart and Buck Jones—and they had several actors at Universal they were grooming to be Western leading men; now we knew we were going to be through anyway in a couple of weeks, and so we decided to kid them a little—not kid the Western—but the leading men—and make Carey sort of a bum, a saddle tramp, instead of a great bold gun-fighting hero. All this was fifty percent Carey and fifty percent me.20

John Ford and Carey usually coimagined their own stories and scripts for two-reelers shot quickly on location. With Straight Shooting they expanded the story to five reels, and despite some opposition at Universal, the picture was released complete.21 Cheyenne Harry (Carey), as the Prairie Kid, agrees to do a hatchet job for the ranchers, until he sees the error of his ways and transforms himself, echoing Hart's character of Blaze Tracy in Hell's Hinges. Harry is the prototype of Ford's reluctant hero who is not afraid to kill when necessary, but who “wouldn't plug someone in the back.” As developed by Ford and Carey, Cheyenne Harry reinvents the westerner, originally conceived in earlier literature such as Wister's The Virginian (1902), drawing on a similar ambiguity about who is right and who is wrong in settling the West. He is a gun for hire, leading an uncomplicated life and liking nothing better than to get drunk with his pals in the saloon.

From Cheyenne Harry's vantage point as an amused observer, he finds it as easy to keep on good terms with greedy ranchers and tough outlaws as to do so with young farmhands. He is not looking to settle down; he cherishes his freedom to sit by the river, hone his limited skills, and avoid getting caught. Too much involvement could lead to permanence, and he prefers to pass by. He is a loner and an outsider to the farmers' way of life, not unlike Gary Cooper's drifter Cole Harden in the first half of William Wyler's The Westerner (see chapter 5) and John Wayne's outlaw Quirt Evans at the outset of James Edward Grant's Angel and the Badman. And as Cheyenne Harry, exiting a cabin door, turns to look back and is shaded and enclosed within the frame of the door, we anticipate Ethan Edwards (John Wayne) in the famous final shot of Ford's The Searchers (see chapter 8).

Cheyenne Harry never seems in a hurry; he likes to pause and look about him, though he can ride fast when the plot calls on him to act decisively. It is this rhythm of stasis and action, of quietly touching or leisurely comic moments between sequences of hard riding and shooting, that makes Straight Shooting a signature Western for Ford, and that will distinguish his later films. The hard riding and gunplay climax in an exciting range war: men and horses race atop canyon cliffs, across rivers, and down hillsides at center screen and often straight at the camera. There is also much hard drinking in a comic sequence in the saloon, offset by moments of mourning, of realizing the price paid to tame the West.

Straight Shooting takes place in a once-endless cattle-grazing territory now divided by farmers' fences. Little sky appears above the high horizon as the hillsides fill the screen: we see riders on horseback in the foreground, the landscape dipping away from us in middle ground, then rising to a high horizon from which cattle and cowboys and outlaws can race down and toward each other (and us). Rather than relying solely on repeated cuts of men and horses racing left to right, chasing one another, Ford contains much of the action in the depth of the landscape, compressing movement in the frame. Thrilling and beautiful, it makes us relax and enjoy the excitement, for we are looking through space, into the landscape, not at a flat plane or backdrop supporting horizontal or diagonal movement.

Ford develops this sensibility for a contained, framed landscape as he experiments with location shooting in his three Westerns of the 1920s and 1930s: The Iron Horse, 3 Bad Men, and Stagecoach. Panoramic vistas were popular in the films of Hart, Fairbanks, and others in the second decade of the twentieth century as well as in James Cruze's The Covered Wagon of 1923, particularly in films where the story takes place in more than one territory. Ford, too, combines various locations to create his landscapes of the imagination, such as the fusion of hills and valleys and flat riverbed in Straight Shooting, but here he plays with depth rather than horizontality. In Straight Shooting we most often look down into the landscape, be it grazing land or the wooded riverside. In certain shots the landscape fills the screen entirely, as the men barely visible at the top ride down to the bottom and center of the screen. Black-Eyed Pete and his outlaw gang split their loot in the hidden Devil's Valley: his men ride single file through a narrow slit in rock walls that rise high before us, then down a steep dusty trail in the hillside, a swirling mass of men and horses, quickly ordered at bottom into a line as neat as a regiment.

We cut to the village of Smithfield, where Cheyenne Harry leaves his horse to get soaked in the rain so he can go and get soaked in liquor in the saloon. The ensuing scenes establish the characters of Harry, a good-time cowboy who can be bought by corrupt pals, of the cowardly sheriff who represents the occasional hypocrisy of Ford's law-and-order enforcers, and of the naive and kindhearted young kid, Sam Turner (Hoot Gibson), a type later represented in Ford's Westerns by Harry Carey Jr. and Ben Johnson (as in Rio Grande and Wagon Master). Cheyenne Harry signs on for a job not knowing precisely how evil the ranchers are; he is not thinking clearly, and he has yet to meet the heroine. The sequence in the saloon typifies what would become another Ford tradition, a change of pace by switching from action to satirical dialogue and gesture, a move that gives individuality to the characters while indulging the director's bent for broad comedy. Drinking is funny in Straight Shooting, 3 Bad Men, and Stagecoach: it endears the imbibers to us in that they are all “good bad men” who will perform heroically if not chivalrously to save a woman.

The death of a loved one often drives the plot of the early Western, and in Straight Shooting it is the murder of the heroine's brother, Ted, the only son of farmer Sweet Water Sims. Ted is shot while drawing water from the spring. Harry rides across the creek and comes upon the boy's burial. He witnesses the father's collapse and convincingly states his innocence: “I've done dirty things in my life—but I wouldn't plug someone in the back.” He takes Sims home, entering through the doorway (a typical Fordian framing device) and shaking hands with Joan Sims (Molly Malone) as he thanks her for opening his eyes to the ranchers' evil nature. He then walks out the door, away from us, remaining engrossed in thought as he rides across the creek, the sun dappling the trees. He rides away as he had come.

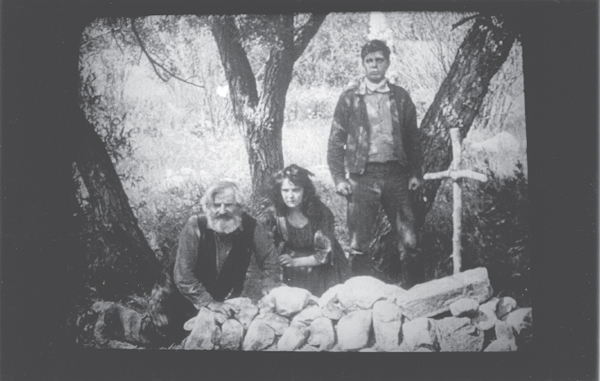

FIGURE 4. In John Ford's Straight Shooting (1917), Sweet Water Sims (George Berrell, left), his daughter, Joan (Molly Malone, center), and Sam Turner (Hoot Gibson, standing) mourn over the grave of Ted Sims. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Subtly handled, too, is Ford's tenderness toward the heroine, especially in a scene that presages women's moments of reflection in his later films. Joan's sorrow and sense of loss are quietly revealed when, alone in the cabin, she removes Ted's plate from the table and holds it close to her as she recalls all that just happened—just as Martha, in Ford's The Searchers, will caress her beloved Ethan's coat before he leaves home once again after having only recently returned (see chapter 8). We may also recall that beautifully touching moment in Ford's The Grapes of Wrath (1940) when Ma Joad (Jane Darwell) holds a pair of treasured earrings to her ears in front of a broken mirror before discarding them along with other “unnecessary” items as she is about to embark on her family's grueling odyssey to California.

Once the villainous rancher Thunder Flint (Duke Lee) learns that Harry will no longer side with him against the farmers, he wants him killed straightaway and assigns the dirty work to Placer Fremont (Vester Pegg), who had done in the Sims boy. Sam Turner overhears and rides off and across the creek (in stunningly photographed shots) to warn Harry. During the prolonged shootout sequence, Harry walks with care, his long legs in cuffed jeans, swaying slightly from side to side as he glides along ever so slightly pigeon-toed. John Wayne, who acted with Carey in Angel and the Badman and Red River, would later adapt the older star's outfit and walk—so unlike Carey's contemporaries Hart and Tom Mix. Carey's outfit, like his character, seems simpler and more authentic in its understatement.

The deaths of young Sims and his killer, Fremont, are the prelude to Flint's launch of the range war between farmers and ranchers, the type of conflict that will be echoed by such Westerns as Wyler's The Westerner (see chapter 5), Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (see chapter 8), and Kevin Costner's Open Range (2003). Farmers assemble at the Sims home, and excitement grows as both sides gather support. Flint's men take off through the trees and cut through a landscape that fills the screen as they ride down and around the Sims farm. Harry, whose morals are eccentric but effective, rides to the entrance of Devil's Valley. Encountering men standing guard, Harry is escorted through the rock slit to Black-Eyed Pete's hideout, where he asks for help in defending the farmers. The outlaws swarm and descend from the hillsides, racing to reach the farm that has been surrounded by ranchers, who quickly scatter in fear. The scenes are fast and exciting; the few extended moments of tension are subordinated to straightforward, cleverly edited sequences of rout and escape. Very little is repetitious and, by 1917, filmmakers like Ford relied on Griffith's parallel editing of climactic scenes in order to build suspense. Here shots of ranchers who surround and shoot at the cabin are intercut with shots of the farmers firing back while the outlaws ride to the rescue. This is reminiscent of the siege of the cabin in Griffith's The Battle of Elderbush Gulch.

Harry pledges to go straight and tells Black-Eyed Pete that it is time to say good-bye. Harry rolls a cigarette while looking out the door; he cannot decide what to do: “Me, a farmer? I belong on the range.” He says he needs a day to think it over, goes to the woods, sits quietly, and seems to pray. When Sam comes along, Harry says that he is leaving Joan to Sam and bids him farewell. At sunset, his decision made, Joan finds Harry and he gives her his answer: it seems he will stay. According to Tag Gallagher in his book John Ford: The Man and His Films, the film originally ended with Harry sending Joan back to Sam, and he is “left facing the sun alone”; but the present happy ending was added on to the reissue of 1925.22

Straight Shooting, similar to Ford's later Westerns and most especially My Darling Clementine, never veers into action for the sake of action. It is leisurely and steadily paced and accented by pauses and reflections, yet also proves exciting in the climax of the range war. Ford learned much from his brother Francis and from Griffith, and he developed his own handling of a simple story, depiction of character, and cinematography in a spirit that was closer to the earlier Biograph films than to Griffith's contemporaneous epics Intolerance (1916) and Hearts of the World (1918). The early style of John Ford is distinct, however, and Gallagher suggests that “in place of Griffith's dramatic shaping, all events in Straight Shooting have equal value, and thus ignite a more active symbolism into land, light, water, and foliage.”23

Ford demonstrates a grasp of rhythm and space that enables him to keep a steady beat, occasioning the viewer's observation of place and detail in order to imbue themes and character with varied meanings. Here an evocation of quiet intimacy receives equal screen time with, and has the same presence as, a shoot-'em-up range war. Other directors will observe the changing natural world in lyrically intimate ways: Satyajit Ray, Jean Renoir, Yasujiro Ozu, and Akira Kurosawa situate their characters in an inseparable relation with their landscapes. Ford uses outdoor space not merely for action settings but also to let his characters pause to feel, reflect, or remember, which Cheyenne Harry does best in sun-spangled woods by the river. Ford shows in Straight Shooting how well he understands the situating of the westerner in his particular space so as to give definition to issues of community, conflict, alienation, passage, and redemption. His pacing allows, too, for the depiction of the duality of human nature: for characters to be both wise and stubborn, both funny and brutal, both selfish and self-sacrificing—as we will also see in later Ford Westerns starring Henry Fonda, James Stewart, and John Wayne.

FORD'S FINAL SILENT WESTERN: 3 BAD MEN

In the Western as epic, westerners are less interesting as individual personalities, serving instead as the supporting cast in stories of expansionism enacted by mid-nineteenth-century settlers in a tremendous, beauteous terrain. The frontier eventually reached the Pacific, having been pushed back by overland wagons, gold rushes, and land grants, as well as by the successful linking of nationwide telegraph and railroad systems. All of these stepping-stones in frontier development were prime subjects of Western epics in the second and third decades of the twentieth century. These films popularized, with sincerity and some historical accuracy, the advancement of the white man's culture and economy.

The success of The Covered Wagon spurred production throughout the 1920s of large-scale, costly adventures filmed in glorious locations. John Ford filmed a pair of these patriotic epics about nation-building. The first was The Iron Horse of 1924, which focused on the successful completion of the northern intercontinental railroad in the 1860s, culminating in a cinematic recreation of the hammering of the last spike at Promontory Point, Utah, on May 10, 1869, by Leland Stanford. Progress comes at a cost, and Ford is sympathetic to the hardships and deaths of settlers and native people; his deep sense of loss, key to his later Westerns, is already apparent. Ford's second epic Western was 3 Bad Men of 1926, which tells the story of the Dakota Land Rush of 1876, when a vast territory was opened up to settlers.

Despite its initial blustery justification of westward expansion into the Dakota territory, its essential lack of sympathy for the displaced Sioux, and its lapse into melodrama, 3 Bad Men is Ford's most meaningful Western of the 1920s. The film reveals greater complexity and grayer shades of meaning than The Iron Horse. The leisurely unfolding of the plot prior to the land rush allows Ford to establish character and the moral duality of the white man: his greed and his desire to build a community. By situating the wagon camp in the valley below the Grand Tetons, Ford creates a backdrop that is often more visually compelling than the staged drama played out before it. The three bad men emerge from this landscape: it is their world, and Ford gives them his time and attention.

Like the reluctant Western heroes of the second decade of the twentieth century portrayed by Hart and Carey, Tom Santschi's Bull Stanley is a big, rough, but understated man of greater strength of character and more subtle intelligence than we would initially expect. He listens and learns, though it is his deep response to the vulnerability and decency of a beautiful young southerner that makes him reset his course. His love for her is clear, as is his conviction that he could never marry her, for he is an outsider, an outlaw, and a man with a past. Having thought it through, Stanley makes his choice, not just for himself but for the three bad men: he and his pals will help and protect her, find her a husband, and defend her from evil even if they must sacrifice their own lives to do so.

At the opening of 3 Bad Men, it is made apparent that there is gold in the Dakota hills. It is 1876, and President Grant has issued a proclamation that will open the lands of the Sioux to the overflow of emigrants. 3 Bad Men begins with a civics lesson of sorts, its numerous introductory titles setting down the reason, or excuse, for the great land rush. And so the film shifts from the grandiose to the specific, introducing the handsome young fortune-seeker Dan O'Malley (George O'Brien), who rides casually along playing his harmonica while wagon after wagon arrives at the foot of bold, sharp-peaked mountains. Dan meets Lee Carleton (Olive Borden) and her father, who are bringing their thoroughbred horses from the South to participate in the land rush. Then three scruffily outfitted outlaws ride up, brilliantly lit by the sun and framed against the mountains, to observe the long line of wagons and cattle following the ridge above the river. Bull Stanley tells his pals, Mike Costigan (J. Farrell MacDonald) and Spade Allen (Frank Campeau), “It ain't gold I'm looking for, but it's a man just as yeller.” The cast is complete as we encounter the man whom Bull is ultimately seeking: local sheriff Layne Hunter (Lou Tellegen), slick in his fancy duds and a wide-brimmed white hat.

In quick order, Ford establishes an ironic moral structure that will sustain his most fully realized Western feature to date: the bad guys are not all that threatening, and the upholder of the law is clearly corrupt, a precursor to such villainous lawmen as Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan) in Wyler's The Westerner, Dad Longworth (Karl Maiden) in Brando's One-Eyed Jacks, and Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) in Eastwood's Unforgiven. The outlaw trio decides to steal the thoroughbreds, but Hunter's men beat them to the wagons. The three bad men ride swiftly to chase away Hunter's men who already have killed Lee's father. When Stanley tries to comfort Lee, she weeps on his chest. Positioned before peaks blazing in the sun beneath bright clouds, Stanley becomes suddenly noble and stops his pals from taking the horses, echoing once again the theme of moral awakening through love that was embodied by the earlier discussed characters of Blaze Tracy in Hell's Hinges and Cheyenne Harry in Straight Shooting. Meanwhile, down in the new town of Custer, pretty young Millie (Priscilla Bonner) tells Hunter that a minister has arrived and they now can wed. He scoffs at her, and she realizes that her seducer has no intention of marrying her.

FIGURE 5. Dan O'Malley (George O'Brien) plants a kiss on Lee Carleton (Olive Borden) in a romantic scene from John Ford's epic 3 Bad Men (1926). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The film 3 Bad Men can be viewed as a tragedy, with its comic scenes serving as cathartic interludes, for much of the film is concerned with loss, humiliation, unstoppable evil, and death. Its outlaw hero, Bull Stanley, is as melancholy as any classic gunfighter. The tragedy has not so much to do with the grander history of the land rush itself; the often uneasy melding of the fictional plot and the reality of history plagues many films and not only the Western. Sheriff Hunter is a cardboard villain, heavily made-up and literally dressed to kill, and his contempt for his girl and the townspeople is obvious. Whoever crosses him pays a heavy price. O'Brien, who had played the leading role in Ford's previous feature The Iron Horse, is handsome but stolid, nominally but secondarily the lead. The true heroes are Stanley and his sister, Millie, who is seduced by the real villain. The strengthening of Bull's character—the ways in which he expresses his love and his willing sacrifice, joined to his sorrowful realization that others will succeed in the new society of the West—reminds us of John Wayne's Tom Doniphon in Ford's later masterpiece The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (see chapter 8).

Stanley's reach for moral regeneration begins when he stops his pals from taking the horses. That night Lee Carleton hires these three bad men, who admit they are available, as business is not what it used to be. She cannot pay them wages, just yet, but Stanley says that they will work for free. “Then you'll be my men?” she asks, and they take off their hats in gallant reply. Stanley is in love with her. When he learns that Hunter, who has vowed to get even with them, also intends to seduce Lee, he knows he must defend her honor while seeking the man with whom his sister left home. He is thoughtful as he polishes the bullets he has saved for such a purpose. Meanwhile his pals have gotten drunk, and a disgusted Stanley decides: “What our gal needs is a husband. We'll find a marryin' man—if we have to shoot him.” His pals select a simpering, Chaplin-like dandy in the saloon, while Stanley finds the good-looking O'Malley, to whom Lee is already attracted.

The narrative shifts among scenes of the developing romance between Lee and O'Malley, the comic carousing of Stanley's pals, the villainous activities of Sheriff Hunter, the tragedy of the once innocent Millie, and the strengthening of Stanley's heroic attempts to protect Lee, find his sister, and defeat Hunter. The sheriff's viciousness knows no limits as he incites his men to send flaming wagons to crash into and burn the church full of women and children (shades of Hell's Hinges), and during the ensuing shootout Millie is fatally hit. The sheriff has told his men to sneak that night into the Dakota reservation, so as to be ahead when the rush begins. Stanley weeps over his dying sister and later carries her body at the head of a parade of settlers riding on horseback with torches.

Flames and smoke rise from the ruined church, and a burning cross stands vividly against the dark sky. The terror is palpable as Hunter incites the lawless, feckless townspeople, those who prefer the saloon to the arrival of religion and decency and who can be incited to commit destruction and murder. This sequence amplifies the evil of Hunter and his absolute rule over Custer. Nothing can stop the sheriff: he has caused the deaths of Lee's father, the old man Lucas, and Millie, not to mention his destruction of the church and attempt to murder the minister as well as the women and children trapped inside the building. And we are just halfway through the story!

Now dawns the day of the land rush, and we see people sweating, cursing, and fighting to get to the head of the line. Millie's brief funeral gives way to people hurrying about. Wagons move to their places amid clouds of dust, waiting for the dot of noon. The minister urges a family to keep their plow, for wealth is in the land. When the cannon is fired, the opening of the land rush is photographed in a high panning shot that gives full sweep to the broad scale of wagons and riders. Later we see the rush from under hoof, with horses leaping wildly over the cameras. Dust and chaos, carriages racing along, riders straining their horses, and a man riding a tall bicycle give way to wagons crashing in accident after accident.

The most fearful moments in Ford's films are often those involving children in danger, such as Bill's leap from the train in Just Pals (1920), the baby bounced around the desert in the arms of the 3 Godfathers, and the abduction of the sisters in The Searchers. Our greatest terror in 3 Bad Men is our fear for the forgotten baby who sits down-screen, having been left by its mother when the father fixed their wagon and then raced ahead. Helplessly we watch the thunderous approach of horses coming straight at the baby, and at us, until O'Malley leans from his horse to catch the child in the nick of time.

At the end of a hard day of riding, Hunter's men chase the group of protagonists as they seek escape through an enormous slit in the rocks. O'Malley and Lee are sent ahead, and the three bad men stay behind to stand against Hunter: they are “together for the last reunion.” What follows is an overly extended sequence depicting the bravery of fools, with each bad man trying to be more sarcastic or noble than the other: cutting cards to see who will stand first, say “Adios, amigo,” and atone for a lawless life. Hunter and his men successfully terrorize Lee Carleton and her protectors for some time. Every attempted standoff by the three bad men seems arbitrary and melodramatic, yet it is Ford's attempt to give each character an honorable exit. Though Hunter is killed, the price is high. The story concludes with the intertitle “As the years went on, the gold of grain grows,” implying that greed will be supplanted by the discovery of good earth. Thus the sacrifice was not in vain in promoting the settlement of the West, and the good will not be forgotten. In the last sequence, O'Malley and Lee are happily farming but then go into their cabin to see their child. The parents show their baby the hats of the “best 3 bad men who ever named a baby,” and the trio is then seen, in spirit, riding on horseback against the sky. The idea of using each of the three outlaws' names for the name of the baby will be repeated in Ford's later 3 Godfathers.

After 3 Bad Men, Ford suspended his exploration of the genre for more than a decade, not directing another Western until Stagecoach, in the autumn of 1938. Instead of filming in Jackson Hole, he went to Monument Valley and the Mojave Desert, locations that would give greater meaning, scope, and scale to his finest Westerns. And Ford found in John Wayne a physically imposing, psychologically compelling screen presence, the kind of actor who could reignite the slow-burning fire of both Carey and Santschi, Ford's earlier good bad men.