CHAPTER 10

Eastwood and the American Western

“High Plains Drifter,” “The Outlaw Josey Wales,” and “Unforgiven”

I've never pictured myself as the guy on the white horse…. I've always liked heroes that've had some sort of weakness or problems to overcome besides the problem of the immediate script. That always keeps it much more interesting than doing it the conventional way. John Wayne once wrote me a letter telling me he didn't like High Plains Drifter. He said it wasn't about the people who really pioneered the West. I realized that there's two different generations, and he wouldn't understand what I was doing. High Plains Drifter was meant to be a fable; it wasn't meant to show the hours of pioneering drudgery. It wasn't supposed to be anything about settling the West.

—Clint Eastwood, interview with Kenneth Turan

Clint Eastwood's diverse acting performances and directing accomplishments in Western films have earned him a solid place high in the pantheon of such genre artists as Ford, Hawks, Wayne, Cooper, Fonda, and Stewart. The action-oriented audience long ago fell in love with the icy but tongue-in-cheek style of Eastwood's grizzled, cigar-chomping antihero in Sergio Leone's “Dollars” trilogy of the 1960s (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly). And many fans appreciated the return of such a character in Eastwood's own High Plains Drifter (1973) and Pale Rider (1985). In many ways this actor's most popular and influential role as urban cop Dirty Harry is a natural outgrowth of that earlier gunslinger who faces danger with the same cool determination and instinctual spontaneity as, say, an expert jazz musician.1

If there are three films that alone would put Eastwood on the map of artists who have excelled in this genre, they are High Plains Drifter, The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), and Unforgiven (1992). With these works we see an actor-director who has fused his talents in the service of extending and amplifying, as well as subverting, the essential traditions of the cinematic Western. There are intriguing parallels among these films, and there are also clear differences between Eastwood's more character-oriented, narrative-driven Westerns and the more stylized Westerns in which he plays the anonymous figure emerging inexplicably from the horizon and returning there, leaving dead bodies along the trail. When one considers his Westerns as a whole, especially those that he also directed, we see that his oeuvre provides a fitting consummation of the genre and intriguingly integrates both classical and postclassical elements of the Western's long and varied history.2

CAREER OVERVIEW

Eastwood's association with the genre goes back to a point before his work with Leone. After some bit parts in B-films, he kick-started his career by playing cattle drover Rowdy Yates in the long-running television series Rawhide, beginning in 1959 and continuing through 1966. While on a brief hiatus from that role, Eastwood moved on to international fame as the “Man with No Name” in Leone's trilogy, beginning with A Fistful of Dollars (Per un pugno di dollari, 1964).3 Shortly before becoming a genuine Hollywood superstar in his role as Harry Callahan—beginning with Don Siegel's Dirty Harry (1971)—this actor furthered his growing iconic status as a westerner. He performed in such films as Hang ‘Em High of 1968 (directed by Ted Post, who had worked on the earlier Rawhide series) and Siegel's action-comedy Two Mules for Sister Sara of 1970, with Shirley MacLaine.

The pre-Dirty Harry Eastwood also starred in a few quasi Westerns that played off the genre in which he had already left a deep boot print. In Siegel's Coogan's Bluff (1968), Eastwood plays an Arizona lawman with a very Western way of doing things, sent to New York City to collect a prisoner and to grapple with big-city crime and an urban police system.4 In Paint Your Wagon (1969), directed by Joshua Logan and adapted by Paddy Chayefsky from Alan Jay Lerner's Broadway musical, Clint undertook what was, in some ways, his most daring role to date: he croons alongside fellow nonsinger Lee Marvin as they play rollicking gold-mining pals in the Old West who share comic adventures as well as a wife. In one of his most intriguing roles, Eastwood starred as John McBurney, a Union soldier recovering from his injuries in an all-female boarding school in the Deep South, in Don Siegel's Civil War-era drama The Beguiled (1971).5

A year after starring in Dirty Harry as a kind of “urban westerner,” Eastwood portrayed the title character in Joe Kidd (1972), based on an Elmore Leonard-penned script and directed by the reliable John Sturges (Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape, Bad Day at Black Rock). Here Eastwood plays a hired gun who joins temporarily with a posse formed by greedy landowner Frank Harlan (Robert Duvall) to eliminate the Mexican revolutionary leader Luis Chama (John Saxon). Eastwood's character in Joe Kidd is as enigmatic at certain points as his previous role in the Leone trilogy, wandering a no-man's-land between various parties in different conflicts. And yet, interestingly, he is given an actual name here and, furthermore, one that helps to form the very title of the movie, as with Coogan's Bluff and Dirty Harry. So is this the story of a specific individual with a specific name and a given history, or is this the tale of an archetypal stranger, some mythical “good bad man”? Joe Kidd wanders somewhere in between. The question, however, evokes a contrast between two very different conceptions of the westerner: the mysterious, usually unnamed gunslinger who passes through communities like some nomadic spirit, on the one hand, and an identifiable individual who struggles to overcome some concrete life situation, on the other. A tension between these two different kinds of westerner reverberates throughout Eastwood's body of work in the genre.

With the subsequent High Plains Drifter, Eastwood began to direct many of the movies in which he starred. He had already directed one non-Western film, the psychological thriller Play Misty for Me (1971).6 In Drifter he plays “the Stranger,” an almost ethereal gunslinger appearing suddenly in the lakeside town of Lago as an agent of retribution and destruction. Eastwood's character reminds us of Leone's Man with No Name because of his anonymity, seeming amorality, and ruthlessness. The Stranger punishes a corrupt and cowardly town for its faults by demanding that the townspeople turn their community into a symbolic Hades of sorts, and the story's fiery climax echoes the apocalyptic ending of Hart's silent Western Hell's Hinges (see chapter 1). Eastwood, in fact, exhibits the same stoic, rough-edged acting style that Hart made famous.

Eastwood then directed and acted in one of his very best Western films, The Outlaw Josey Wales, a Civil War-era portrait of a man driven to obsessive vengeance after the murder of his family. The main character departs substantially from Eastwood's earlier incarnations of the no-named stranger, as well as from the title character of his later Pale Rider. The latter characters are westerners who nearly transcend the human realm altogether, emerging from and disappearing into a mist of myth and archetype. But Wales is someone who has a definite biography: he is originally a family man, and we know (as with his character in the earlier Hang ‘Em High) the precise reasons for his current vengefulness. We follow Josey after he has been transformed into an almost robotic creature, driven by a desire for retribution, and witness his eventual restoration as a genuine person who falls in love and who cares for his acquired “family.” Wales gradually reclaims his own essential humanity in response to the influence of the small community of outcasts he has adopted during his odyssey.

The Outlaw Josey Wales is a kind of precursor to Eastwood's 1992 masterpiece Unforgiven in that both films center on rifle-wielding killers who are presented, not in terms of mystery and anonymity, but rather in terms of their character development and ethical motivation. Given such a contrast between the different types of westerner that Eastwood has played, and because the film is an intriguing fusion of classical and post-classical aspects of the Western, it is not surprising that he dedicated (in the final credits) the Oscar-winning Unforgiven to both Siegel and Leone, whose cinematic styles and story choices are dissimilar.7 Siegel tended to favor stories that depict real-life individuals in real-life situations, done in a straightforward nononsense manner, while Leone gravitated toward archetype, myth, and stylistic grandeur.

Despite their differences, one similarity between Siegel and Leone is their tendency to veer into dark comedy at times. Eastwood's films are certainly not devoid of levity, and his use of occasional humor recalls the fact that Westerns and comedies have often intersected (see chapter 3). Eastwood's attempts at sporadic comedy in his Westerns often succeed because he is willing to exaggerate or even parody his famously macho persona. For instance, there is a fair degree of cynical wit, helping to balance out the heavy doses of violence, in Leone's “Dollars” trilogy, as when Eastwood's ultracool Blondie plays straight man to Eli Wallach's hysterical Tuco in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966). In Josey Wales, Eastwood infuses the movie with subtle humor at times, despite the highly serious theme of revenge and the episodes of brutal warfare. Several of his scenes with Chief Dan George are intentionally comical; Chief Dan's deadpan responses border on the Keatonesque. And despite the movie's frequent funereal somberness, there are also dashes of dark humor in Unforgiven, whether in the interplay between Sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman) and Old West-mythologizer W. W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek) or in the farewell shot of English Bob (Richard Harris) scolding the entire town of Big Whiskey for being a bunch of “bloody savages.”

FIGURE 47. Clint Eastwood stars as retired gunfighter and current hog farmer William Munny in Eastwood's Oscar-winning Unforgiven (1992). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

In terms of outright Western comedy, Eastwood directed and starred in the highly entertaining Bronco Billy (1980). This film is a gentle comedy of cowboy manners, playing off the idea of the westerner as a legendary hero for children to admire and enjoy. The title character, a kind of tragicomic descendant of Buffalo Bill Cody, struggles to keep his traveling Wild West show afloat financially while also dealing with humiliation, frustration, friendship, and possible romance. In various ways Eastwood has constructed and deconstructed ideas of the westerner over the decades, sometimes revealing the stark reality behind the legend. In Bronco Billy he depicts a small-time businessman attempting to keep the legend alive, despite having a difficult time doing so. Here Eastwood again reveals the vulnerable human being behind his tight-jawed tough-guy image, and the film manages to poke fun at the genre by highlighting its show business side and the artifice of Western mythmaking in the contemporary world.

HIGH PLAINS DRIFTER

The persona of the anonymous, ruthless gunfighter that Eastwood had adopted in his earlier “spaghetti” Westerns is amplified in High Plains Drifter, the first Western that Eastwood also directed. In his role as tough cop Harry Callahan, he had fashioned a screen image stretching across different films and exemplifying the type of challenge to traditional movie heroism that had blossomed with the more psychological and existentialist Westerns of the 1950s (see chapter 7). However, Eastwood's shaping of his screen persona over the second half of the 1960s and first half of the 1970s did not include the types of hero-deflation or psychologizing that could be found in some of these earlier examples of genre revisionism. Eastwood was still very much the confident gunslinger transcending the boundaries and conventions of “ordinary” society, and the inner lives of his characters were hidden behind a glacial facade. But he was not a hero in the traditional sense, as the actor admitted in more than one interview (see the quote at the beginning of this chapter). Unlike John Wayne and his typical association with America's dominant ideas and values, Eastwood tended toward characters who were antiheroes, driven toward revenge and killing for reasons that had little to do with building or defending a growing civilization. And given the cultural climate of the Vietnam and Watergate era, this tendency toward antiheroism fit with Hollywood's growing patterns of cultural critique and tradition-shattering. William Beard nicely summarizes this in his Persistence of Double Vision: Essays on Clint Eastwood:

Eastwood arrived in Hollywood during this wholesale dismantling of prosocial heroism, armed with the knowledge (gained with Leone) of how to present heroic power in the total absence of any kind of social project. Leone's decadent European skepticism totally incinerates all idealist social beliefs and leaves the gunfighting hero—whose constitutional function hitherto has been to enable the good community—stranded in a literal and figurative wasteland with no interest to uphold but his own. The hero's mastery, no longer connected with a grand ideological project and denuded of classical camouflage, instead takes the form of a mysterious transcendent power…. It has been a central feature of Eastwood's persona (and this has surely been important in his cinematic survival through the various culture upheavals over the years of his career) that the project of its heroism has always been accompanied by markers of the implausibility, unnaturalness, and indeed impossibility of its own existence.8

High Plains Drifter was released in 1973 and appeared on the crest of a wave of genre-revising Westerns, as discussed in the last section of the previous chapter. Eastwood's movie was a paradigm of the antitraditional Western, with some of the raw violence of Peckinpah, the antiheroism of Altman and Penn, and the nihilism of Leone. Eastwood's more Leone-esque movies, such as High Plains Drifter, tend to be highly stylized, where the visual and musical effects, as well as the creative presentations of violence, often trump characterization and dialogue.9 In his later Pale Rider, another avenging angel/demon story that echoes George Stevens's Shane (1953), Eastwood plays a mysterious preacher-gunslinger who, as in his earlier Drifter, appears when needed and rides away into the desert and mountains when he has completed his task. Such films are, like Leone's, “antipsychological” in the sense that their main characters veer toward archetype, caricature, and even abstraction—and so contrary to the kinds of Westerns made by directors such as Mann and Daves (see chapter 7). In Drifter and Pale Rider, Eastwood gives us gunslingers who are creatures of enigma and action rather than practitioners of situated introspection.

As seen in previous discussions of films such as Hawks's Red River and Ford's The Searchers, the style of a Western film includes as one of its integral components the aesthetic relationship between characters and their immediate settings. Eastwood's appreciation for the importance of landscape is certainly on display in Drifter, and particularly in his use of the almost surreal terrain around Mono Lake near Yosemite National Park and the California Sierra.10 The movie takes place in the fictional lakeside township of Lago. The silver-blue expanse of water in the background of many shots may remind one of Brando's similar and original use of a shoreline setting in his One-Eyed Jacks, the only film that Brando ever directed. In fact, if one does not look carefully, the viewer may easily think that the body of water behind the town of Lago is a part of the ocean rather than a landlocked lake, and even the production notes on the DVD version of Drifter mistakenly refer to its “seaside” setting. Precious few Westerns have this kind of backdrop. As director Anthony Mann once observed, it is odd that so many of the classic Westerns are set predominantly in desert regions like Monument Valley, since the West has such a variegated landscape, including the forested and mountainous regions for which Mann had an affinity.11 Eastwood, like Mann, diversifies the audience's experiences and expectations of Western terrain.

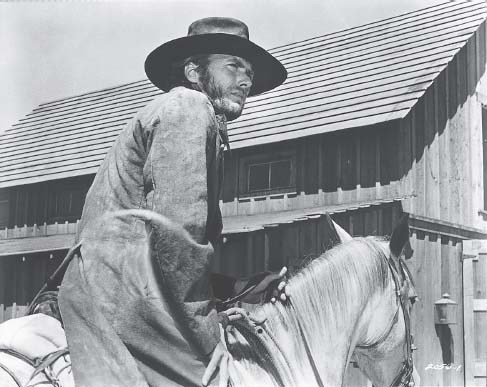

FIGURE 48. Clint Eastwood as the anonymous stranger who arrives in the lakeside town of Lago in Eastwood's High Plains Drifter (1973). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Much of Drifter takes place within the confines of Lago, though the surrounding lake and hills are almost always visible, framed between buildings or by the windows of the local hotel, barbershop, and mercantile. Eastwood's emphasis on the natural world that, in the Old West, lies always just beyond the main street of town is even evident in the landscape paintings that hang in the hotel where his nameless character takes a room. And with so many scenes that have as their backdrop shimmering lake-water or olive-green hillside or cloud-spotted sky, the movie does more than merely take advantage of the scenic opportunities of on-location shooting, in the best tradition of the action-filled Western film. The film also gives its audience a sense that the self-centered and morally passive townspeople of Lago have forgotten the world of rugged beauty that lies beyond their small world of material comfort. The landscape here is intriguing, and since this is a fairly dreamlike Western with hints of the supernatural mixed in, it is fitting that the natural scenery appears almost otherworldly. Eastwood once said in an interview about his choice of setting for the film: “I wanted to get an offbeat look to [the film] rather than a conventional Western look. Mono Lake has a weird look to it, a lot of strange colors—never looks the same way twice during the day.”12

The physical town of Lago, in terms of its buildings and layout, is something akin to a character in the film, as is the case with many other artificially constructed towns in classic Westerns: for example, Lordsburg (Stagecoach), Dodge City (Dodge City), Tombstone (My Darling Clementine), Shinbone (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance), and El Dorado (El Dorado). Townships in movies such as Drifter play as significant a role as the natural landscape does in other Westerns in shaping the atmosphere in which the characters move and act. And when it comes to the selection and creation of proper settings for his films, Eastwood typically chooses to work with the very best. The town in High Plains Drifter was constructed under the experienced art director and set designer Henry Bumstead, who had also worked on Joe Kidd, as well as on Mann's 1950 psychological Western The Furies, among countless other films.13 In his biography of Eastwood, Richard Schickel discusses how Bumstead's work for Drifter helped to realize Eastwood's intentions: “Bumstead built the village in twenty-eight days, complete with interior sets, and in its rawness, its suggestion of impermanence, it is something of a masterpiece. Reminiscent of silent-film western towns (one thinks of Hell's Hinges, the William S. Hart film), its primitiveness says something about the heedless greed of its residents, their lack of rootedness and their lack of interest in building for the future. It—and they—parody the western town in most movies, where neat churches and schools bespeak hopes for more civilized times to come.”14

But after having exposed us to so much of the memorable landscape around his constructed community of Lago, Eastwood then erases it, so to speak, in the final nighttime sequence. Here the Stranger eliminates the three villains who have come back to town to satisfy their own desire for justice, having been “betrayed” by the townspeople whom they had once guarded. We see only the darkened town itself, painted entirely red and renamed “Hell” at the command of the Stranger. This scene anticipates the rain-soaked, nocturnal finale of Unforgiven, where Munny enacts rage-driven vengeance against Sheriff Daggett. In that scene too we have only meager glimpses of the town itself, without any indication of a surrounding natural world.

Just as Drifter's town and its adjacent lake possess an enigmatic aura, so too does Eastwood's anonymous character. What makes the Stranger most mysterious is the fact that he seems to be connected, without clear explanation, to the former Marshal Jim Duncan of Lago, a man who was whipped to death on the main street while most of the townspeople simply looked on without doing a thing. Even by the end, when the drifter rides out of town past Duncan's visible gravestone, we wonder just who this man is, the very question that forms one of the concluding lines of the film. He is either the ghost of the murdered sheriff, come back to haunt the town that had turned on him—in which case the movie rises to a supernatural level that is echoed by Eastwood's later role as the mystical preacher-gunfighter in Pale Rider—or he is the sheriff's brother or friend, also bent on revenge.

Marshal Duncan, as the plot later indicates, was an honest man who had planned to divulge the fact, held secret by the townspeople out of their own economic interest, that the mine on which they depend is located on federal property. The citizens, fearing governmental interference in their profit making, paid three criminals to help enforce the secrecy of this information by punishing, and eventually killing, Marshal Duncan. But unfortunately for the residents of Lago, these hired assassins then lorded it over the town in a tyrannical manner after having murdered the lawman. The citizens responded to this egregious behavior by alerting the regional legal authorities to the trio's crime.

Through its eventual focus on the story of a sheriff who must contend with his own community, Drifter makes clear thematic reference to High Noon (directed by Fred Zinnemann, 1952) in the same way that the later Pale Rider plays off Shane.15 Eastwood has stated in an interview: “The starting point [of Drifter] was: ‘What would have happened if the sheriff of High Noon had been killed? What would have happened afterwards?’”16 As in High Noon, three villainous gunslingers are finally released from jail and seek vengeance while a town tensely awaits their arrival. Also as in High Noon, the townspeople prefer to depend on the strength and courage of a single man to save them. On the other hand, quite unlike High Noon, the citizens' new “savior” is no hero, but just the opposite, a man who would rather see the town destroyed than saved. If anything, he arranges them like targets in a shooting gallery when he advises them to hide in seemingly strategic locations and shoot at the three desperados as they approach town. He knows that they will be little more than sitting ducks. Also unlike Zinnemann's classic, where the townspeople did nothing to help their brave sheriff (Gary Cooper), the residents of Lago are forced by the Stranger to prepare for their own self-defense, even if he will finally be the one to flick the whip and pull the trigger.

With Drifter we are reminded also of Kurosawa's samurai classic The Seven Samurai (1954), as well as his later revisionist samurai film Yojimbo (1961). The latter film, in fact, served as the clear basis of Eastwood's first Leone-directed western, A Fistful of Dollars.17 In The Seven Samurai, townspeople hire a group of warriors to protect the town from marauding bandits, much as Lago depends on the Stranger in Drifter. In Yojimbo we see the need for a protective samurai, and the hired warrior (Toshiro Mifune) is, like Eastwood's drifter, a wandering man without a known past—and one who remains cynically neutral even when faced with a conflict that threatens to destroy a community. It is true that the Stranger in Drifter does not care for financial gain and even denies at one point that he is a gunfighter, meaning that he does not hire himself out for such purposes. But like Mifune's character in Yojimbo, he is apathetic to the welfare of those he is supposed to defend. If anything, the drifter seeks his own revenge against all concerned, but in a mysteriously slow and playful fashion.

The reason why the Stranger undertakes a methodical form of vengeance has to do with Marshal Duncan. The supernatural possibility of the drifter being the ghost of the murdered lawman is made all the more probable when he dreams of Marshal Duncan's whipping, an event that only Duncan himself (or those who watched his slaying) could have experienced. As Schickel informs us, it was the director's wish to leave this mystery intact to engage the viewer, though Eastwood “now says the script definitely identified the drifter as the murdered sheriff's sibling.”18 The director's decision to leave the Stranger's identity indeterminate adds effectively to the overall feeling of mystery and ambiguity inherent in the style and landscape of the movie as a whole.19

In an intriguing footnote in the history of Hollywood Westerns, John Wayne, who had encouraged Eastwood early on, suggested that the two stars should work together at some point. But Wayne wound up declining when, in the mid-1970s, Eastwood sent Wayne a script that allegedly required more revision. The elder actor used his letter to his younger counterpart as an opportunity to criticize High Plains Drifter because its “townspeople…did not represent the true spirit of the American pioneer, the spirit that had made America great.”20 Eastwood later reflected on Wayne's letter in an interview and concluded: “I was never John Wayne's heir.”21 He pointed out that Wayne was the westerner who typically played by the rules and lived according to a code of honor, always for the sake of a just cause. Eastwood admitted that his own westerners often did not: “I think the era of standing there going ‘You draw first' is over. You don't have much of a chance if you wait for the other guy to draw. You have to try for realism. So, yeah, I used to shoot them in the back all the time.”22

THE OUTLAW JOSEY WALES

Eastwood's more Siegelesque films, such as The Outlaw Josey Wales and Unforgiven, are in the Fordian and Hawksian (i.e., classical) mode of stylistic economy, where choices of mise-en-scène and montage become more or less invisible—that is, not pronounced in an exaggerated or self-reflexive manner. The cinematic form here is dictated by the demands of character development and story-governed logic, and this is also true of more recent Eastwood-directed films, such as Mystic River (2003), Million Dollar Baby (2004), Flags of Our Fathers (2006), Letters from Iwo Jima (2006), Changeling (2008), and Gran Torino (2008). Don Siegel's own later Western The Shootist (1976), starring John Wayne in his superb career-culminating performance as a semiretired gunslinger dying of cancer, anticipates Unforgiven to some degree not merely because of its narrative-driven style but also because of its theme, which is that of a retired killer who must return one last time to his violent ways.23

The Outlaw Josey Wales is two hours and fifteen minutes long and moves at a pace accommodating the riders, who wander through forest and canyon, from the Indian territory to the wide open spaces just north of Mexico. Eastwood mocks the very persona that he also partially mythologizes in this visually stunning film, which has the rhythmic patterns of Ford's Westerns, with alternating sequences of action and reflective stasis. Josey Wales is one of the finest of Westerns in its thematic and visual use of landscape to illuminate mood, character, and climax.

The film also suggests the oppositions and contradictions within human nature that inform the genre at its most meaningful levels. On the one hand it is a remarkable portrayal of a killer, with its protagonist quick to outdraw and shoot to death a large number of people, either out of spirited vengeance or in cool self-defense. A simple Missouri plowman, Josey Wales becomes a dedicated avenger after he sees his wife and son murdered and his house burned to the ground by marauding Redlegs (Union guerillas). The character of Josey Wales may therefore be compared broadly with revenge-motivated westerners such as the Ringo Kid (John Wayne) in Stagecoach, Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) in My Darling Clementine, Will Lockhart (James Stewart) in The Man from Laramie, Ethan Edwards (Wayne again) in The Searchers, and Rio (Marlon Brando) in One-Eyed Jacks. In addition, Josey can be compared with the William Hart-type hero, stoic and laconic—except for a meaningful dialogue with Ten Bears (Will Sampson), his Indian counterpart—and his humor lean and dry. As Wales moves west, he is seen to be kind and patient while caring for the strays who attach themselves to him: a young mortally wounded rebel, a wise old Cherokee, an experienced squaw, a scrawny dog, and a Kansas mother and her pensive daughter. Most everyone whom Wales eliminates deserves to die for having gone after his family or his fellow rebels or his merry band. The only adversaries as smart as Wales—former rebel Fletcher (John Vernon) and chief warrior Ten Bears—are also the only ones to understand and forgive his actions.

In the first scene of the film, we witness the murder of Josey's wife and son by the Redlegs while he is out plowing his field. He hears horses galloping by and sees black smoke rising above the forest from the direction of his home. He runs to find his house on fire and his wife being assaulted by men on horseback; but before he can react, Josey is struck to the ground and hears his son cry out. One of the Redlegs strikes Wales across the face, leaving a bleeding scar, and the attack is over as suddenly as it began. We then cut to the next day and watch Josey as he buries his wife and child. His son's little arm falls out from under a blanket as Josey drags the corpse to be buried. Grief-stricken, he pushes a wooden cross down into the simple gravesite. We may recall here Ethan Edwards's horror and deep sorrow in The Searchers when he returns to his family's destroyed ranch and discovers his beloved Martha's ravaged corpse. Like Wales, Edwards does not waste time in sublimating his sorrow into obsessive revenge, and this is emphasized by his angry interruption of the family's funeral in the hope of catching up with the Comanche as quickly as possible: “Put an amen to it!” (See chapter 8.) We might also remember here Wyatt Earp's similar transformation from grief-stricken mourner to calculated revenge-seeker in Ford's My Darling Clementine, though Earp goes about his vengeance in a much quieter, law-abiding way (see chapter 7).

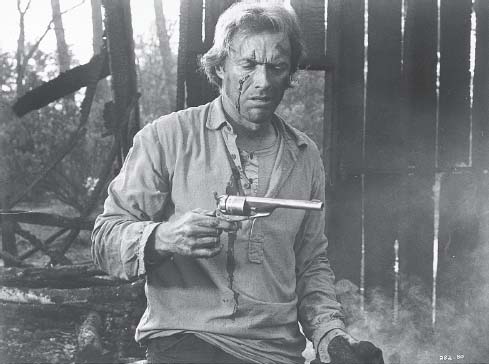

FIGURE 49. In Clint Eastwood's Civil War-era Western The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), the title character, whose wife and son have been brutally killed by Union guerilla fighters, is about to embark on his new life as a gunslinging revenge-seeker. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Josey begins practicing with a pistol while preparing for a career of retribution, and he is soon approached by a band of Confederates, including their leader, Fletcher. They say that the Redlegs who committed these killings must be up in Kansas with the Union; Fletcher's own men are going up there to “set things right.” Josey agrees to accompany them, and as the credits begin to roll with trumpets blaring and drums beating, we see Josey and the band of men ride quickly through forests and across prairie land, killing Union soldiers along their way. The montage here is rapid and soon fades into gray-and-blue-tinted shots of battle action. The Civil War-era setting reminds us of earlier Westerns such as Raoul Walsh's Dark Command (1940), based loosely on the story of Confederate guerilla leader William Quantrill, and Ford's The Horse Soldiers (1959), the tale of a Union cavalry unit sent to fight behind enemy lines.

Fletcher eventually tries to persuade the men to surrender to the Union forces so that they can then go home. He tells them that they are the “last of the holdouts,” that everyone else has given up, and that he is going to surrender since he has had enough. He manages to convince everyone except Josey, and when Fletcher tells him that there is nowhere left to run, Josey replies that he “reckons that's true.” Fletcher wishes him luck: he recognizes Josey's unconditional determination to seek retribution and see personal justice served. We catch a glimmer of admiration in Fletcher's eyes as he bids Josey farewell.

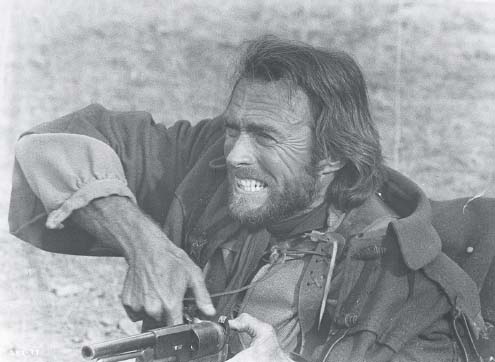

FIGURE 50. Josey Wales prepares to do battle in his role as revenge-seeker. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

We then witness Fletcher's men gunned down by Union soldiers after they have been deceptively asked to stand in a row at their surrender and swear a pledge to the United States. Fletcher, standing alongside the Union officers who commanded this, is shocked because he was told that proper Union authorities were supposed to be the ones handling the surrender. It is, however, the Redlegs commander Terrill (Bill McKinney) who coordinates this mass execution, and Fletcher angrily calls him a “butcher.” Now that the soldiers have been eliminated, the commanding Union officer, “the Senator” (Frank Schofield), orders Terrill to go after Wales with everything he has got—but Fletcher laughs and sarcastically wishes him luck in catching Wales. Fletcher is offered money to help in hunting down Wales, but the former rebel leader tells the Senator that he has had enough of his money already. We now know that Fletcher had been previously paid by the Union troops to persuade his men to surrender. And so begins a classic tale of revenge and justice in the post—Civil War West, though with several elements that revise the genre in intriguing ways.

FIGURE 51. Josey Wales (far right, holding pistols) squares off against the brutal Redlegs commander, Terrill (Bill McKinney, center). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Wales's moral character is clear: he is a good man driven to retribution by the evil of others, even if that evil is qualified to some degree by the wartime and postwar situation. Fletcher's morality, however, is questionable, since he has positioned himself between an alliance with the Union officers and feelings of empathy toward Josey. He rejects the Senator's money and expresses anger that he was double-crossed; but we then see him working with the Union men in hunting Wales, having been offered a special commission. Fletcher consents to the assignment, but he prophesizes nonetheless that Josey will be waiting in hell for them. He appears to have eventually surrendered to his doomed mission (and any of the accompanying monetary rewards) after having acquiesced to the Union forces and accepted, however regretfully, the consequences of that decision.

On the other hand, we recognize Josey as heroic from the moment he bravely rides into the Union camp to try to save his fellow Confederates while enacting revenge. Unfortunately he is too late: the Union soldiers have already begun firing on the surrendering Confederates, and Josey escapes, barely, with one man who has survived the massacre: a young soldier named Jamie (Sam Bottoms). His bond with the boy foreshadows our protagonist's eventual rehumanization. From this point on in the movie, Eastwood introduces minor characters in a “vignette” style that echoes Ford's talent for presenting stereotypical characters in a way that makes us think we have seen them before, even if we have not.24

This is the case when Josey and the boy eventually reach a river and find the ferryman chattering away with a dubious-looking elixir salesman. An old woman in a nearby cabin figures out who Josey is and warns him that Union men had recently stopped by looking for him. After then dealing with two hillbilly bounty hunters, Wales and his young protégé journey on in heavy rain and eventually build a small shelter. Josey goes out to have a look and sees the cavalry camped out by the river; when he returns, he discovers that the boy has died from his wounds. Josey closes Jamie's eyes, puts his body on a horse, and says an overly brief eulogy for him, despite his aversion to burials and blessings after having had to commit his wife and son to the earth not long before. Josey fires a shot and the horse takes off for the cavalry camp, the body of Jamie strapped to the animal. Josey reassures himself that the “blue bellies” will give a better burial than he can. As the Union men go after the horse that has run wildly through camp, Josey passes by unnoticed, journeying deeper into the woods.

Eastwood's film does not shy away from the theme of death, and in anticipation of his Unforgiven, it depicts the ugly consequences of violence. This is especially clear given the wartime setting and Josey's persistence in avenging the deaths of his wife and son. The characters' awareness of fate reverberates throughout the film, along with their ever present need for justice and retribution. And perhaps most of all, Josey Wales is pervaded by the same sense of tragic loss that informs the greatest of Western stories, ranging from The Wind (see chapter 2) and Red River (see chapter 6) to The Searchers and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (see chapter 8). It is this sense of loss that typically motivates the hero to act in ways beyond the ordinary, even while making the hero more human by the end, given the lessons learned.

This is a Western that also takes great care in showing us the humanity and nobility behind its Native American faces. In this regard, Josey Wales echoes anomalous silent Westerns like Griffith's early “East Coast” Indian stories, as well as The Vanishing American and Redskin (see chapter 1), and later “Indian-friendly” Westerns such as Delmer Daves's Broken Arrow and Ford's Cheyenne Autumn. Wales enters the Indian territory and meets up with Lone Watie, who tells Josey that he has heard of him, and that the white man has been sneaking up on his people (the Cherokee) for years. He tells of how the government broke their promises and treaties and sent the Indians into “the nations.” The white man has killed his wife and family, he declares sadly, and we immediately recognize a parallel between the two outcasts. Josey replies that it looks as if they cannot trust the white man, and there is an instant bond established, embodied by a clear chemistry between the two actors. Their rapport is wry and solid, and their responses to each other are immediate and comfortable. Lone Watie explains that the whites tried to make his people look “civilized” and told them to “endeavor to persevere.” He says that, when the Indians had thought about it long enough, they decided to declare war on the Union. And so there is another parallel suggested here, one between the tribes and the Confederates, both feeling a need to battle the government and its policies. But Josey is now snoring, a comic conclusion to an otherwise somber and moving scene.

The focus on themes of death and loss is echoed by Eastwood's use of natural settings. The narrative plays out carefully against the brilliant landscape, and most of the film is autumnal in mood and in fact. The leaves are turning red in Missouri and blazing yellow as Josey moves west. Nature appears as more or less lifeless, most scenes unfold in daylight, and except for a couple of saloon scenes, all scenes take place outdoors. We also notice that the landscape gets ever more severe as Wales escapes from Missouri into the heat and sun of the southwest. The landscape has a look and feel not unlike certain passages in John Sturges's Westerns: seductively beautiful in places but always rife with danger. It is difficult to see in this landscape, and Wales frequently squints, though his aim is perfect and his quickness on the draw is certain. As John Gourlie and Leonard Engel observe in the introduction to their essay collection Clint Eastwood, Actor and Director: New Perspectives: “Wales is a character of greater emotional depth than Eastwood's ‘stranger.' The landscape helps portray these depths, for it changes as Wales changes, reflecting his inner states. The film begins with an idyllic, pastoral setting of farmland, then moves to fields filled with blood and killing, then to rain-sodden swamps and lowland, from there to a dry and empty desert, and finally to an Edenic valley, evoking the harmonious landscape of Wales's farm at the beginning of the film.”25

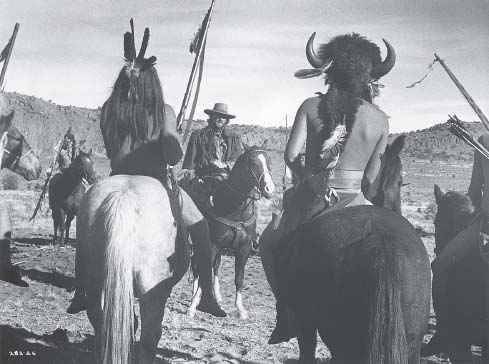

FIGURE 52. Josey Wales (center, facing camera) converses with a Comanche tribe and their leader, Chief Ten Bears (Will Sampson). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Wales, once the avenger, eventually becomes a reluctant killer who wants to be left alone, but who cannot escape his many pursuers and opponents. The Union army soldiers are smug and vengeful, self-righteously eager to betray him; the Redlegs are unscrupulous killers, disguised as soldiers for hire; and the rapists and bounty hunters are particularly bloodthirsty in their ugliness and filth. Like other westerners, such as Ethan Edwards, Wales distrusts authority, opting to follow his instincts and act on his own. As the story moves west, however, it is the adopted strays who repeatedly save him. As he leads them to their new homestead, he watches a line of Comanche following alongside him, but the Indians are the only set of men who do not attack. This tribe and its leader, Ten Bears, are (like the Cherokee) more thoughtful than the white men ruling the West after the war. They desire only to live on their land as they always have.

The Outlaw Josey Wales is long like a Howard Hawks Western, and for similar reasons, as the film is concerned more with character development than with action for the sake of action. The various side trips into Indian lands, hostile towns, and canyons help to fill out the portrait of a man in search of regeneration. It is an engaging and often amusing depiction of an emerging community, of hard-luck strangers coming together to start their lives over again: the Cherokee who has lost his homeland, the mother who has lost her son, and even the briefly encountered saloon sitters who lost their town when their nearby mine (along with the liquor and beer) ran out. But it is difficult for Wales, who lost his family and his home, to stop running and killing and stay in one place.

The last scene is bittersweet as he heads back to his strays, riding into the sun, weary and wounded. It is an exceptionally beautiful ending, and quite moving, for Wales is much more than some Dirty Harry on horseback. He is about to cease being a loner and a rebel, unlike Edwards at the end of The Searchers (see chapter 8), and more akin to Cole Harden at the end of The Westerner (see chapter 5). He wants not only to protect but also to participate in the community he put together. He is another southerner turned westerner, no longer seeking vengeance but instead seeking freedom from his constant task of evading pursuers. And though it is not made absolutely clear in the final shot that Josey is on his way back to his “family” of friendly outcasts, the director certainly intended his audience to hope for such an ending. As Eastwood stated in an interview in regard to a debate with his editor, Ferris Webster: “He [Webster] felt that I should literally show him [Wales] returning to the girl and the group after he has that final talk with the chief. And I said, ‘No, you don't need to show him going back. You see him riding off at sunrise and that's enough.’”26

UNFORGIVEN

Unforgiven is a movie about violence in the Old West, but it also expresses Eastwood's accumulated appreciation of the natural landscape, an appreciation that he undoubtedly acquired from his personal travels over the years, from his frequent on-location work in Westerns and other films, and from his intimate familiarity with the genre's regular emphasis on the intersections between character and environment. It is likely that Eastwood's reverential use of natural settings has its deepest origins in the many Westerns he watched while growing up. Eastwood made clear the influence of these early viewings in an interview with Kenneth Turan in 1992, around the time of Unforgiven's release:

When I was a kid there was no television, but you had Westerns on the second half of the bill in theaters a lot. I grew up watching all the John Ford and Anthony Mann Westerns that came out in the 1940s and 50s, John Wayne in all those cavalry kind of Westerns and Jimmy Stewart. The B-Westerns too, the ones with Randolph Scott. Some of them were good, some were not so good, but we enjoyed them just for the adventure of it all. I grew up through a whole era of them.27

Directly following this excerpt in the same interview, Eastwood expresses his interest in another kind of Western, one that has a social conscience but which may be less visually striking in terms of landscape-oriented shots. Such a Western prioritizes its concern with questions of justice and morality. The director told Turan, “One of my favorite films when I was growing up was The Ox-Bow Incident, which analyzed mob violence and the power of the mob getting out of control. I saw it again recently and it holds up really well. I don't know how the public feels about those kinds of films, but I just felt it was time to do one again.”28 The Ox-Bow Incident (1943), directed by William Wellman, is a morality tale about justice and conscience, but it also revolves around personal awakenings and transformations of character, themes that echo those of certain silent Westerns by Griffith, Hart, and Ford (see chapter 1).

With this in mind, it is easy to see why Eastwood was enthusiastic about David Webb Peoples's script for Unforgiven after he read it, since the story is a perfect fusion of Eastwood's long-running interests in the Western film since his earliest experiences of the genre. Just as one cannot appreciate the Westerns of Ford and Mann without absorbing, even if subconsciously, their striking use of the natural landscape, one would be unlikely to choose The Ox-Bow Incident as a favorite without some deep interest in how a good story can provoke reflection on the concepts of justice and human nature. William Beard views Unforgiven as a later instance of a morally and psychologically complex Western like the ones developed by Anthony Mann in the 1950s, which were echoed and amplified by Ford's revisionist Westerns. According to Beard, these Westerns constitute the “last historical outpost of the antinomic moral and social dualities that organized the genre before the onset of complete alienation, pastiche, and open deconstruction.” He concludes that Unforgiven is a significant vestige of this earlier phase of the Western, describing the movie “as a peculiar late flowering of the kind of complex western that arose as the famous ‘moral clarity' of the genre began to be cast into doubt and the entire system to be undermined.”29

Unforgiven's screenplay was written by Peoples in 1976 and had been kicking around Hollywood for a good long while. Francis Ford Coppola had briefly owned the rights to produce the script but had given up on the idea of making the film. Eastwood purchased the screenplay shortly after Coppola dropped it, but he sat on the script for some years. He did this not because his interest faded but because his passion for the story was so strong that he needed ample time to prepare for the film, and perhaps also because he wanted to play the character of Munny when he felt he was the right age to do so.30 The story concerns a weathered farmer and widower who leaves his children temporarily and goes off to earn a financial reward by avenging a sadistic assault on an innocent young prostitute in the town of Big Whiskey.

FIGURE 53. Ex-gunfighter William Munny prepares to come out of retirement, in Eastwood's Unforgiven (1992). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Eastwood's emphasis on natural scenery is especially pronounced in the establishing shots in which the town of Big Whiskey is dwarfed by the towering mountains of Alberta, Canada, where most of the movie was made. It is also evident in shots, like the opening one, in which Munny's cabin is silhouetted, along with a tree-crowned hillside, against a gorgeously lit sky. And it is evident in scenes where Munny, his friend and former partner in crime, Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman), and their young new “partner,” called the “Schofield Kid” (Jaimz Woolvett), make their way through the sagebrush-spotted wilderness to Big Whiskey, where they will perform the killing and, they hope, collect the resulting financial reward. Edward Buscombe describes the sequence this way: “Ned gives a final look at his wife before riding off. A slow track-in shows her standing impassive as the music swells up. She will never see him again. There follows a lyrical passage, a montage of shots of Will and Ned riding through a field of whispering, golden barley, then across a sunset skyline, a sequence mirrored once Ned and Will have caught up with the Schofield Kid; the beauty of nature appears in contrast to the ugly human acts which are to follow.”31

Eastwood also uses selective shots of nature, visually elegant and each lasting only a few moments, as scene dividers. These quiet and poetic moments strike the viewer as a fitting contrast to the human-centered scenes of anger and violence that dominate the narrative. They appear at first as gentle grace notes, visual ornaments that add to the aesthetic world of the film beyond the immediate dictates of the narrative.32 But rather than remaining as merely decorative, such moments are, as Buscombe suggests, ultimately symbolic of a more natural and harmonious world beyond the brutality and artifice of self-centered human beings.

Unforgiven, much like High Plains Drifter, winds its way to an ending where the landscape is, in fact, conspicuously absent. Munny's concluding acts of vengeance take place in a night-shrouded, rain-pelted townscape where nothing beyond parts of the main street and the saloon are visible. It is in these scenes that the truly dark side of Munny's character becomes visible, the aspect of his psyche that has been long repressed and that once took the form of a bloodthirsty, and frequently drunken, killer of the guilty and innocent alike (including women and children, as he admits). In these bullet-ridden final scenes, we are thrown into the central message of the movie, a lesson about the terrifying repercussions of violence, even when such acts seem absolutely necessary—whether in self-defense, in the building of civilization, or for the sake of justified retribution. Nature is absent in these shots because we are now summoned to think solely about the negative consequences of our own self-absorbed humanity. In terms of lighting and color, the entire film is consistently muted and drab in tone. But the final sequence depicting Munny's revenge-taking is so soaked in darkness that it may as well have been shot in black and white. Eastwood has remarked about his choice of colors and tones in making Unforgiven:

I remember those high-gloss Technicolor Westerns, those “three-stripers,” I saw as a kid…. All that light and those saturated colors. I never liked it. Some of them are called “classics,” but they were too artificial and unreal. You had to light things differently in those days, with the “brutes” and everything. [Cinematographer] Jack Green has helped me change that…. We asked ourselves, how do you make things look coal-lit and at the same time provide enough light that we can see what's going on? I figured, let's forget that we're shooting in color and think of it in black-and-white terms. We informed the costume designers and the production designers that we wanted muted tones and a “black-and-white” look.33

We might also think here of such Westerns as High Noon and Rio Bravo, where the natural landscape is mostly absent, and especially of Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, which concentrates most of its concluding scenes in the confines of saloons, newspaper offices, political rally halls, and cramped sections of a main street. Just as it was no doubt the desire of Zinnemann, Ford, and Hawks to narrow the focus of these films to lessons concerning the human condition and the sacrifices that civilization sometimes requires, so it is Eastwood's desire to make primary, in his conclusion of Unforgiven, the lessons that humans must learn about themselves. This is why the landscape simply disappears behind rainfall and pitch darkness.

Nonetheless, both Unforgiven and Valance bid similar farewells to their audiences by returning us ever so briefly to shots of the natural landscape in which the given communities in the narratives have arisen. Valance concludes with the shot of a train, a symbol of civilization and progress, taking Ransom and Hallie back East. The train chugs away from us through a wide valley surrounded by hills, the same landscape that we saw at the outset of the movie. Unforgiven concludes with a static shot of Munny's tiny cabin silhouetted against a barren hillside and sunlit sky, similar to that of the movie's opening shot, with text emblazoned over the image to suggest that Munny and his children may have finally made it to a life of civilization where, we can hope, the need for violence has been left far behind. And so, after leaving us with messages about the contingencies and dangers that are inherent in the human condition, both films pull us back, so to speak, in order to view the larger natural world that has always been there awaiting us.

Munny is a character who finds himself not only within the actual physical landscape but also within the psychological and moral landscape of his own troubled memories and sense of loss. With his gruff, stoic exterior, he appears as hard as the land itself, but we can see that he is a fragile, aging man who dearly misses his deceased wife and who is not sure how he and his children will sustain themselves. The audience is caught in the strange situation of rooting for Munny, despite our concerns about his morally ambiguous character. There are, of course, the stories about his bloody past, and his mission in Big Whiskey is clearly not a morally redemptive one.34 And yet we still feel empathy for him, not merely because of our growing dislike of the sadistic sheriff who winds up being his enemy, but also because it is difficult to escape our habituated affinity for Eastwood's many heroic protagonists, no matter how violent they may get.

Munny returns to his old ways purely for the sake of the offered reward. He needs the money to provide a proper life for his children, since his attempts at farming and raising hogs are failing because of his lack of experience, and because of a fever spreading among the animals. He returns to his old ways in order to attain a life beyond the need for violence. Munny's heart is not really in the job of killing the man who attacked and mutilated the prostitute, nor, we might guess, was his heart in many of his past killings. He blames most of those earlier murders on having been drunk out of his mind on a regular basis in those days. But Munny is dedicated wholeheartedly to the sober job of killing Sheriff Daggett as retribution for the latter's torture and murder of Ned, and Munny even exhibits visible conviction in killing the saloon and brothel owner for having offered his front porch for the grisly display of Ned's corpse.

There is a parallel here between Munny and Josey Wales, since Josey too had been driven to heartless killing in order to avenge the deaths of loved ones. And before heading to Big Whiskey, Munny recently tried to live the kind of stable farming life that Josey had enjoyed up until the time that his family was slaughtered by the Redlegs. Like Wales, Munny must delve into a dehumanized state of being, at least temporarily, in order to do what he deems necessary, whether for the sake of his children or for revenge. But we get the feeling at the very end of the film that Munny will leave this mode of existence behind since he knows the evils and horrors of such a life.

Unforgiven also prompts reflection on the morality of Little Bill Daggett, a small-town tyrant who acts in the name of “the law” (primitive though this law may be). He appears to believe that he is enacting justice, but he executes his decisions in a slimy and sadistic manner. Eastwood said of the character in an interview, “I think he's a good sort, at least in appearance. He has a certain charm…. I believe he thinks he's doing the right thing, just a man who's doing his job.”35 He has also remarked about the character, going beyond the issue of mere appearance: “Little Bill is a sheriff, but he is not really a good guy; he is really just a killer who happens to have the law on his side. At the same token, Will Munny is also a killer. The only difference between him and Bill is that Little Bill has the rationale of having law enforcement on his side.”36 Actor Gene Hackman has commented about his portrayal of Little Bill: “I tried to make him human and monster at the same time.”37

FIGURE 54. William Munny and his friend Ned Logan (Morgan Freeman, right) confer about their bounty-hunting expedition. Courtesy of Malpaso Productions/Warner Brothers.

Little Bill echoes such villainous but charismatic characters as Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan) in Wyler's The Westerner and Dad Longworth (Karl Malden) in Brando's One-Eyed Jacks.38 On the one hand, we might simply view Daggett as a killer-turned-sheriff who has risen above the errors of his earlier ways. He now upholds the law, though he enforces it in an excessively violent way to make his point clear to potential lawbreakers. But whatever the code of law in Big Whiskey may be, Daggett's twisted morality is evident in the fact that he barely punishes the men involved in the mutilation of the prostitute. He merely asks that they give several of their horses to the brothel owner (and not right away, at that) in return for his “damaged property”: a maimed harlot who has lost her ability to make money because of her permanent scars. Little Bill does not even whip the men, his usual mode of punishment, and Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), the brothel's madame, rightly protests against this gross injustice. Little Bill will not listen to her, since in his view the men are hardworking fools who simply got “a little carried away.” They are not “wicked” in a consistent fashion—not “like whores.”

FIGURE 55. Sheriff Little Bill Daggett (Gene Hackman, left) instructs bounty hunter William Munny on the ways of frontier law. Courtesy of Malpaso Productions/Warner Brothers.

By the conclusion of Unforgiven, Munny has unleashed his vengeance against Daggett for what the latter has done to Ned. His acts of retribution are as raw and primitive as Clytemnestra's murder of her own husband in Aeschylus's The Oresteia. Munny's revenge is mechanical, nearly inhuman. Eastwood has stated about this scene, referring to his character's relapse into sheer emotion of a demonic nature:

[Munny has] thrown a switch or something and now a kind of machinery was back in action, a “machinery of violence,” I guess you could say. No, it wasn't glamorous. He's back in his mode of mayhem. And he doesn't care. He's his old self again, at least for the moment. He doesn't miss a beat while he loads his rifle and talks to the journalist. Before, he's been very rusty, having trouble getting on his horse, he wasn't shooting very well. He wasn't nailing people with the very first shot (like I would do in my earlier films!). Now, when he goes on this suicidal mission, he's all machine. He not only coldly murders Daggett at point-blank range but shoots some bystanders with no more compunction than someone swatting a fly. Munny has been protesting all the time that he's changed, but maybe he's been protesting too much.39

At the end of the film, we learn that Munny may have wound up in the dry goods business in San Francisco, presumably with his children in tow. It is only mentioned as a possibility, but we would like to believe it is true, just as we want Josey Wales to return to his “family” at the end of The Outlaw Josey Wales. In both films, violence has been required to end violence and to set things right, which is a theme of many traditional Westerns, ranging from Hell's Hinges to The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

FIGURE 56. Gunfighter William Munny prepares to settle accounts at the conclusion of Unforgiven. Courtesy of Malpaso Productions/Warner Brothers.

Unforgiven reminds us of Henry King's The Gunfighter (1950) and Siegel's The Shootist because it is a story of a man who desires to hang up his gun for good, but not before one final act of violence becomes necessary. Like these other films, Unforgiven has much to say about the reputation that a gunslinger earns and how that man must live, often regrettably, with the consequences of that reputation. Eastwood's film, then, provides another profound lesson about mythmaking and the falsehoods that lie behind the stories that both glorify and haunt men with violent pasts. Its lessons about the deceptions involved in Old West mythologizing, and about the horrifying violence that permeated the reality of the Old West, make Unforgiven an exemplar of genre revisionism, even with its classical form of montage and visual stylization. In his biography of Eastwood, Schickel nicely summarizes how this film helps tear down the familiar patterns of the genre:

Unforgiven cuts a narrower, deeper path through the form's conventions. None of its bodies are nameless. All its deaths count for something…. On its way to that conclusion, it casually, almost incidentally, subverts our comfortable expectation of stock western types and situations. This is a movie in which whores turn out not to be golden-hearted, but angry and vengeful; a movie in which a seemingly reasonable lawman turns out to be an ugly sadist who, unlike the reassuring peacekeeper of western lore, is not the source of the community's stability, but of its chaos; a movie in which the celebrity gunfighter, before whose reputation all are supposed to tremble, is revealed to be an empty blowhard, and the seemingly psychotic adolescent, who aspires to similar fame, turns to mush when he actually kills someone. It is finally a movie in which the presumptive hero, lured out of retirement to right a wrong, does not find moral satisfaction in the act, but despair, rage and something very close to madness.40

Unforgiven deals in a melancholy manner with the relationship between truth and myth in the ways that Schickel outlines. But rather than arguing for the persistence of legend even while showing us the truth, as we might find in certain Westerns by Ford (Fort Apache and Liberty Valance, primarily), Eastwood's film reveals the ugly reality behind the mythology of the Old West and leaves it at that. It is Munny's harsh reputation that sends the Schofield Kid looking for him, and that, after twists and turns, eventually gets Ned killed for no good reason. In Unforgiven we are not presented with some argument that violence is ultimately necessary in the pioneering and building of a nation. We are instead presented with the brute reality of the violent act and all of its repulsive consequences, with violence begetting more violence. Schickel highlights a crucial exchange between Munny and his young partner:

“It's a hell of a thing, killing a man,” proclaims Munny in one of the film's most profound and reflective scenes. “You take away everything he's got and everything he's ever gonna have.”

“Will, I guess they had it comin',” replies the Schofield Kid.

Munny: “We've all got it comin', Kid.”41

Or, as Munny tells the dying Little Bill at the conclusion of the film, right after the sheriff has declared that he does not deserve this particular type of death: “‘Deserves' has got nothin’ to do with it.”

The intersection between the desire for violence and the innate human need for justice, typically in the form of some type of retribution, lies at the heart of the film, but problematically so. The movie relies on certain expectations on the part of its audience, and the viewer's participation in Munny's transformation is at best an uneasy one. Eastwood has said about his intentions in drawing attention to such an intersection, with due reference to audience expectations: “I've done as much as the next person as far as creating mayhem in Westerns, but what I like about Unforgiven is that every killing has a repercussion…. An incident will trigger decisions, maybe the wrong decisions or the wrong reactions by people, and then there's really no way to stop things. But the public may say, ‘Yeah, I get the morality of it, but I like it better when you're just blowing people away.’”42

Screenwriter David Webb Peoples is a tad more reluctant about declaring that the film's message is one of antiviolence, preferring instead to say simply that the movie emphasizes the theme of violence, and that violence is indeed “frightening.”43 However, Jim Kitses argues in his analysis of Unforgiven that Eastwood's intended critique of violence does not completely succeed in the end, mainly because he strategically appeals to his audience's expected desire to see Munny unleash his final, bloody vengeance against Daggett. If Eastwood in his final sequence depends on a traditional use of violence to satisfy the audience's thirst for the villain's death, then the overall message of the film has been corrupted, according to this interpretation. As Kitses argues:

It is difficult to understand how the director can hold such views [about the film's treatment of the consequences of violence], given the film he has made. The massacre executed by a Munny of mythic proportions is vastly fulfilling and entertaining, a spectacle that is both “source of humor” and “attraction,” effectively blurring the film's argument that violence is the property of an unhinged masculinity. Having Munny become the tool of a lethal and transcendent retribution that culminates the film's action and supposedly resolves its issues in fact implicates the film in the violence it is critiquing…. No Brechtian, his [Eastwood's] aesthetic requires the audience to identify with and invest in the action…. Ambitious, compelling, but finally flawed, Eastwood's critique of the Western as a genre sustained by masculine codes of violence is itself all too satisfyingly sustained by that same violence.44

This criticism of the film is initially persuasive, given the expectation that most viewers will find Munny's brutal vengeance against Daggett satisfying, and that the narrative structure of the movie plays to this expectation. However, upon further reflection, one might ask whether the viewer's patient anticipation of Munny's act of retribution may be the result of her familiarity with the Eastwood persona. If we pay close attention to the final scene, we notice that Munny allows Daggett's men (the ones who do not want to wind up dead) to leave the killing scene, and he shoots an unarmed man (the saloon/brothel owner). He finishes off Daggett, who is lying wounded on the floor, and responds almost mechanically to Beauchamp's questions, as if trivializing the act that has just occurred. Munny then wanders off into the rainy blackness, having regressed into a brutal primitivism that he had once struggled to transcend. It is hardly a scene that glamorizes or celebrates violence, let alone satisfies a viewer's desire for the type of classic Western showdown that resolves issues of justice and retribution. Eastwood concludes his film not with such a showdown but with a pathetic last stand by a man who has lost a beloved friend, and whose only course of action is his return to a way of life that he had sought so desperately to leave behind.

Granted, the typical viewer will find satisfaction in the elimination of Daggett, particularly after the horrible cruelty that Daggett unleashed against an undeserving Ned, and in this Kitses is correct. Unforgiven does deliver when it comes to the anticipated extermination of this sadistic sheriff. But it does not deliver “the goods” because of the specific ways Eastwood and his screenwriter have presented this act of primitive justice. Munny is a pitiful figure, not a heroic one, most especially since he has undertaken a morally questionable venture that got his best friend killed—and left his vulnerable children behind, to boot. If we find any genuine heroism in Munny's violent killing of Daggett, given the way this killing is presented, then it is probably we who should become the object of criticism, not Eastwood or his film.

With Munny's sweeping and nihilistic declaration that the principle of desert “has got nothin' to do with it,” the film ultimately evokes a final question about the concept of justice and the relationship between morality and the law, a question as old as Hammurabi's code and as recent as today's newspaper headlines. The same question emerges in many conscience-themed Westerns. But what lies at the heart of Unforgiven, expressed in the very title of the film and throughout its narrative, is the basic truth that, no matter whose justice and whose morality, violence is an ugly thing and gets even uglier. Unless it is somehow transcended, which it all too rarely is.