CHAPTER 2

Not at Home on the Range

Women against the Frontier in “The Wind”

Nature appears in most Western films as a setting, obstacle, metaphor, or source of inspiration, or as a combination of the above. In The Wind (1928), nature is manifested chiefly as a threatening, sinister, destructive power that transforms as well as tests the psychology and character of its human protagonist. At the symbolic level, the desert winds of the early frontier become a supernatural, erotic force that drives Letty Mason (Lillian Gish) to the brink of madness. Tautly directed by Victor Sjöström (known in Hollywood as Victor Seastrom), the film is marked by persuasive terror and sexuality, which were shaped by three extraordinary, and at that time highly successful, female talents: Gish, novelist Dorothy Scarborough, and screenwriter Frances Marion. Together they created a film that is one of the most intriguing of Westerns, especially in terms of the relationship between humans and their natural environment.1

The Wind remains unique among landscape Westerns in creating a female protagonist who battles hostile forces of wicked men and evil nature alone, without a hero to come to her rescue.2 Letty does not manipulate men to destroy one another, nor does she entice them to sacrifice their lives for her. Letty has no greed to make her evil; she is not a “good bad woman.” Even the virtuous heroine Jane Withersteen in Riders of the Purple Sage, one of the most popular early Western novels to portray a woman as an equally central character, relies upon her rescuer and principal lover, Lassiter, to stop their pursuers. And what also distinguishes both novels among Westerns—Riders of the Purple Sage, which was written in 1912, and The Wind of 1925—is the latter's metaphorical presentation of the landscape as the heroine's other lover, a demonic “stalker” of limitless psychological and physical power, a sexual tormentor eager to destroy. Riders of the Purple Sage, which must have been well known to Scarborough, concludes with the anticipated climactic fall of Balancing Rock, destroying the villains and bringing together Lassiter and Jane forever as the rock seals them in the hidden valley beyond Deception Pass.3 In Riders, nature assists human love rather than conquering or replacing it by means of its own sensual power.

Character and community in the frontier landscape can be understood, and intriguingly so, through this focus on sexual passion. James Folsom analyzed the symbolic parallel between civilization and eros that emerges in The Wind:

The novel's real strength lies in its carefully thought-out and generally skillfully developed symbolic structure, for The Wind is a study in symbolic opposites.…The wind becomes a symbol for the frontier life before the advent of civilization, and its symbolic values of wildness and freedom are emphasized by the wild black stallion to which it is often specifically compared.…The metaphorical opposites of Letty and the wind become symbols for the process of colonization…[and] the bringing of land under the plow becomes an emblem for the replacement of “Texas” by “Virginia.”4

Folsom goes on to say that this dialectic is expressed through “the omnipresent sexual symbolism which fills the book[:]…the more elemental purely sexual metaphor of the wind, seen first as a great black stallion, an obvious symbol of sexual power; later, more explicitly, Letty hears the wind ‘wailing’ about her house ‘like a lost soul, like a banshee, like a demon lover,’ images which constantly reappear.”5 Letty's ultimate seducer is not a man but the North Wind, which takes the form of a ghost horse that lives in the clouds; in the novel it is a black stallion, in the film a white steed, the better to prance before dark clouds in Letty's nightmare vision. Black or white, its symbolism is clear: the wind is a powerful threat, beautiful and dangerous because forever chaotic and untamable. The wind, like the horse, is active and destructive, resisting the very civilization that women were to bring to the frontier. Scarborough's novel makes this clear:

But long ago it was different. The winds were wild and free, and they were more powerful than human beings.…In the old days, the winds were the enemies of women. Did they hate them because they saw in them the symbols of that civilization which might gradually lessen their own power? Because it was for women that men would build houses as once they made dugouts?—would increase their herds, would turn the unfenced pastures into farms, furrowing the land that had never known touch of plow since time began?—stealing the sand from the winds?6

Such was Scarborough's premise underlying the tragedy of a woman who fails to civilize the frontier. The Western is typically preoccupied with notions of masculinity, marked by chivalrous deeds and noble daring, and the classic westerner is traditionally male. But of course there is an occasional focus on the women of the West, and the role of Letty Mason, played by Lillian Gish, in The Wind is a prime example of such a focus, anticipating such characters (among countless others) as Barbara Stanwyck's Vance Jeffords in Anthony Mann's The Furies (1950), Joan Crawford's Vienna in Nicholas Ray's Johnny Guitar (1954), Vera Miles's Hallie in John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), and Claudia Cardinale's Jill McBain in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). The Wind is an effective counterexample to scholars like Brett Westbrook, who, even with certain qualifications, view the American Western as defined almost solely by the authoritative presence of the male/masculine. Westbrook has stated in an article on the predominance of the masculine in the films of Clint Eastwood:

Despite their presence on the historical frontier, women seem to have no place on Hollywood's frontier. Given the generic requirements of unencumbered “freedom” to ride away into the sunset and the absolute necessity of participation in violence, women are not, as many feminist critics have argued, “erased” from the classic Western; there is literally no room for them in the first place. They cannot be erased because they were never there to begin with. Westerns require a landscape in which women cannot move with any liberty; Westerns require a constantly confrontational stance vis-à-vis nature and Indians that women, by virtue of their exclusion from instigating violence (as opposed to being the objects of violence), cannot take.…Ironically, Westerns actually need women.7

Scarborough's story of Letty's transformative encounter with the Western wilderness was tailor-made for the silver screen, particularly in the hands of Sjöström and Marion, and more especially as a vehicle for the talents of Gish. The theme of the struggle to establish community—to bring women from a supposedly civilized (or, alternatively, a decadent) eastern America to the raw but pure frontier—offered the actress abundant material for rich character portrayals in Westerns ranging from Griffith's The Battle of Elderbush Gulch (1913) to John Huston's The Unforgiven (1960). At the time of The Wind, Gish was still one of MGM's most beloved stars, although she would leave the studio in 1927, prior to the film's release in November 1928. Years later, she said that when she signed a contract with MGM in 1925, the studio had no stories for her. Having portrayed heroines of various historical periods—first for Griffith in The Birth of a Nation (1915), Broken Blossoms (1919), Way Down East (1920), and Orphans of the Storm (1922)—Gish brought to MGM the stories of Romola (1924, directed by Henry King), La Bohème (1925, directed by King Vidor); and The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (both directed by Sjöström).

The Wind reunited Gish and costar Lars Hanson, director Sjöström, and screenwriter Marion, following their previous work together on The Scarlet Letter. Nathaniel Hawthorne's 1850 novel interpreted an earlier American frontier bordering on the New England wilderness of the seventeenth century. In the Puritan community, order was severely imposed through strict adherence to law and through suppression of the freedom of expression. The story's publicly humiliated victim, Hester Prynne (Gish), is seduced by the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale (Hanson), has his child, and is punished by the community. In The Wind, nature is expressed almost solely in a negative and destructive manner. But in The Scarlet Letter, Hester regards the wilderness as a refuge or escape, its thick woods offering a glimpse of alluring freedom, since the community does not nurture or protect Hester but rather makes her an outcast from it.

Hawthorne was writing at mid-nineteenth century, long after the frontier had shifted from New England to the trans-Mississippi West, beyond the Rocky Mountains to California and Oregon, and from Virginia to Texas and the vast Southwest. The frontier was formed by rugged landscapes that became defined by the white man's continued imposition of law and settlement. In novels and stories derived from this new frontier community, women were meant to bring virtue and civilization to the wilderness and were punished if they failed. By the early twentieth century, Molly Stark in Owen Wister's The Virginian and Jane Withersteen in Zane Grey's Riders of the Purple Sage had to accept their heroes and frontier lives as they were. The rough terrain enticed brutal men to be as evil as the natural forces surrounding them, to indulge their greed for cattle, land, and women. This recurring theme of the conflict or tension between civilization and wilderness would be most powerfully imagined by Scarborough in The Wind. The novel depicts the landscape metaphorically as the heroine's true love, but it is a powerful and demonic seducer, determined to destroy her and, in so doing, drive away forever the feminine forces that have come to civilize the newly occupied territory.8

Gish thought The Wind would make a perfect motion picture: it was “pure motion,” she said.9 Her MGM contract stipulated that Gish would be consulted on script, director, and cast. Rights were secured, as was approval from the studio's production chief, Irving Thalberg. Gish wrote a four-page outline that she gave to Frances Marion, who developed it into a screenplay, and it was agreed that Sjöström would direct. The seamless melding of naturalism and tragic grandeur apparent in The Wind had also been evident in the previous collaboration of Gish and Sjöström as they worked from Marion's sensitive scripting of the Hawthorne novel. The theme of sexual entrapment, played out within the American frontier landscape, dominated The Scarlet Letter and The Wind. In both films Gish's character is an outcast: first as Hester, an adultress who raises her child in a Puritan community, and then as Letty Mason, a “useless” wife who is raped and who commits murder on the desert plains.

In Sjöström's major films, he revealed a moral ambiguity in his characters' struggles to survive their hostile surroundings. And he approached the layered renderings of sexual passion in the narratives chosen by Gish as intensely and movingly as he had when directing his earlier silent films in Sweden and Norway. The struggle of man in his natural environment, a popular theme in Swedish drama and literature, was an essential theme in this period for Sjöström as well as for his partner, Mauritz Stiller.10 On the screen, the emotional and visual complexity of Sjöström's landscape narratives, shot on Scandinavian locations in richly rendered lights and shadows, reveals the psychological tensions and passions of the protagonists in nature. Personality and landscape influence each other in fundamental ways, as we also see throughout the history of Westerns: “Fate is character and landscape is fate.”11 The external natural world both conditions and metaphorically expresses an individual's interior reality and worldview. This is the core of Sjöström's brand of poetic tragedy, as these outdoor cinematic narratives blend human performance with the naturalism of the physical elements. Key to this structure is the broken or unsuccessful journey, so often endured by the westerner. Peter Cowie notes that “the idea of the journey is the catalyst of The Wind, as it is of most of Sjöström's films. His heroes and heroines can only learn the truth about themselves and their secret flaws by traveling; the way is difficult and strenuous.”12

Self-transforming odysseys are measured in psychological and moral terms but also by passage through space and time. A character's physical, geographical, and temporal passage is in turn defined by the individual's changing relationship to the earth itself. The external journey through time and across terrain conditions the individual's inner journey while also expressing that transformation symbolically. For example, Sjöström's 1917 masterwork Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru (known in the English-speaking world as The Outlaw and His Wife or You and I) is set in the sparse, mountainous landscape of eighteenth-century Iceland. Sjöström stars as Berg-Ejvind, a thief escaped from prison, to which he had been confined for stealing a sheep. He becomes the trusted foreman of the farm of a handsome widow, Halla, played by Edith Erastoff, Sjöström's soon-to-be wife. Halla's brother-in-law insists that they should be married, to unite their fortunes, and after she spurns him he plots his revenge and pursues the thief. Halla realizes her love for Berg-Ejvind and they flee to the mountains, where for sixteen years they live as husband and wife amid nature, joyfully fishing, swimming, and washing in the high waters and falls nearby. But the rock cliffs and flowing water are both paradise and hell. In the terrible battle with her brother-in-law and his men, Halla intentionally destroys her child. Years afterward she hallucinates about her daughter as the end arrives during a fierce snowstorm. She, like Letty, flees into the wind and storm; her lover finds her and dies embracing her.

These protagonists can conquer neither the past nor the brutal forces of an unforgiving nature, but still they love each other. Sjöström and his cameraman, J. Julius (Julius Jaenzon), heighten the expressiveness of the characters' eyes through the effective play of light, while shadows sharpen the dangers of the cold, night, and storm. The filmmakers bring out the texture and feel of the elements, of the thickness and flow of the water and the wind. We see in The Outlaw and His Wife what Sjöström would achieve most effectively and expressionistically in the mise-en-scène of The Wind: both a raging world of nature and the interior of the pathetic shack where Letty will go mad as her home sways and falls apart in the storm. With The Wind, Sjöström put onto the screen in visual terms what Frances Marion was able to put onto the pages of her screenplay in literary form: Scarborough's brilliant fusion of an animated symbolic wilderness, the power of erotic passion, and the specter of insanity for those who could not deal adequately with a brutal frontier existence.

FIGURE 6. Letty (Lillian Gish), Roddy (Montagu Love, center), and Lige (Lars Hanson) during the dance sequence in Victor Sjöström's The Wind (1928). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

In her book Off with Their Heads! Marion summarized the bleak fate of Letty, explaining that she had wanted to keep it bleak in the film.13 In Scarborough's novel the protagonist is the cyclonic wind that blows relentlessly across the vast cattle ranges in Texas. To that wind-tormented prairie comes a penniless and delicately reared southern girl seeking refuge with her cousin on his ranch. From that point on, the story slowly and inevitably reveals the trap that closes over this frightened girl: her cousin is dying of tuberculosis, she is led into marriage with Lige, a cowboy rancher, and she is forced to live the kind of life pioneer women accepted as their fate.

“It's pretty gloomy,” MGM studio boss Irving Thalberg remarked to Marion after reading the script, “but I think the public welcomes a strong melodrama now and then.”

“But no happy ending, Irving,” Frances Marion pleaded. “Please, not that!”

“I agree with you. No happy ending.”14

Marion's script and revision, filmed in the spring and summer of 1927, are spare and intelligent in the depiction of loneliness, as well as in the renderings of the sexual threat of the unrelenting Roddy (Montagu Love) and of the equally malevolent wind. The intertitles read as simple and direct frontier talk, revealing the characters to be, in turn, brutal and gentle. Marion alters various characters' personalities, backgrounds, and physical makeup so as to simplify motives made obvious by repetitive description in the novel and to concentrate the actions of wind, storm, restless cattle, and wild horses. The first half of the novel takes place largely at the ranch of Letty's male cousin, Beverly; she does not marry Lige and move into his shack until well after the midpoint of the novel. Scarborough evokes Letty's home back in Virginia through the lonely girl's remembrance of the sweetness of the changing seasons, in bitter contrast to the continual harshness and violence of the Texas plains. As Freedonia Paschall and Robert G. Weiner inform us in their essay “Nature Conquering or Nature Conquered in The Wind (1928)”:

The novel describes Letty as being “oppressed by the solitude of nature which was so different from the friendly countryside she had known at home—these vast, distressing stretches of treeless plains, with nothing to see but a few stunted mesquite bushes, and samples of cactus that would repel the touch. No friendly intimate wild animals such as she had always been used to seeing—gossipy squirrels grey or brown, chipmunks.” “In Virginia there were rivers, calm and life-giving…and lakes with water lilies, and alder-fringed banks; and little, talkative brooks…(and) birds that sang and nested.” Letty knew a world with servants and a carefree life where nature was something to be looked at and admired for its tranquility. The natural world of Virginia was not the world of West Texas that she saw as raw and uncivilized. Virginia was already refined and was not really the natural world, in Letty's mind. Throughout the novel she thinks of her former home.15

The novel sets the character of Letty, the delicate flower of the civilized South, against the magnificent beauty and strength of Cora, Beverly's wife, the ideal woman for the settlement of the Western frontier. The novel's parallel structure that is built around the contrast between these archetypal females is eliminated in the screen version, no doubt for reasons of story economy: Letty's struggles against frontier men and the frontier itself were obviously enough to fill a feature film. And so the “rivalry” between Letty and Cora is downplayed to some degree in the movie adaptation, and the plot's streamlined focus on Letty's journey into an almost otherworldly realm gives the film its special dramatic power and psychological intensity.

FIGURE 7. The delicate Letty (left) is confronted by the strong frontier wife Cora (Dorothy Cumming, right). Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The Wind gives us no wagon trains, gunslingers, or showdowns on the main street of town. There is also no role here for the Native American, neither in the novel nor in the film, since the chief antagonists are an overbearing white man and an overwhelming natural world. As Paschall and Weiner also tell us in their essay: “The film softens the novel's portrayal of Native Americans, referring to them as Injuns and describing their view that the wind was like a horse.…There is no reference in either version [novel or film] of The Wind to Native Americans as ‘noble savages.’ Indians are seen as a part of nature, which needed to be subdued.”16

The film's power derives instead from the focus and pace established early in the narrative and never relaxed: the tragic events succeed one another in a swift sequence to the beat of the wind. There is but a single story, with no sustained subplots and few comic asides. Characters are introduced and then gotten out of the way so as not to distract from the central theme, a woman seduced and threatened with madness. Unlike John Ford's Westerns, such as The Searchers, there is little pause for relief or reflection and few leisurely scenes of sentiment or broad comedy to ease the harshness and cruelty. And unlike Howard Hawks's Westerns, such as Red River, there is no camaraderie or mutual love between the principals of the same sex, who in The Wind are female. The other woman, Cora, is depicted briefly and more narrowly in the film as jealous, hateful, and full of spite. In both novel and film, Letty's husband, Lige, has a sidekick, Sourdough, but neither man has a role in the key scenes, for this is Letty's story. Lige, an honest and decent rancher, is physically strong and steady, but rough, and he lacks the capability, psychologically as well as financially, to make frontier life bearable for Letty, to educate her and rescue her from her enemies. She is attracted not to the good people, Lige and Sourdough, but only to her enemies, the sexually potent Roddy and the wind.

Sjöström and Marion instilled in The Wind the edginess of a psychological drama, its claustrophobic atmosphere frightening Letty and pushing her toward insanity and murder as the focus tightens on scenes of the ranch enveloped in the never ceasing wind and blowing sand. The Wind is not a classic Western of chase and rescue, for Letty must rescue herself. In Gish's major per formances for Griffith in the epics The Birth of a Nation, Way Down East, and Orphans of the Storm, the tension is built from shots of Gish in terrible danger intercut with shots of her savior's dash to her rescue. Broken Blossoms, arguably their finest work together, is atypical of the Gish-Griffith films, for there is no last-minute rescue. Instead, it is her father (Donald Crisp) who drives Gish's character to madness. In a drunken rage, he has locked her in a closet; as she listens to him, she realizes that he will murder her. We feel her claustrophobia and her dread in Broken Blossoms, just as we feel the sound and might of the norther when Gish listens, at first nervously and then fearfully, in The Wind. The suspense in both films is terrific, and we do not quite know what is going to happen.

Sjöström builds suspense from The Wind's opening scenes, establishing the opposition between Letty and the landscape. John Arnold's black-and-white cinematography masks the light as the wind stirs the sand to block the sun. We never see the horizon, for The Wind is a Western that hides its landscape visually while highlighting it thematically. It is the intensity of this filtered light that makes the terrain of prairie and hills so threatening and terrifying throughout the narrative. The initial intertitles deride mankind's settlement of the wilderness: “Man—puny, but irresistible—encroaching forever on Nature's vastness, gradually, very gradually, wresting away her strange secrets, subduing her fierce elements—conquers the earth! This is the story of a woman who came into the domain of the winds.”

And so we meet this woman who ventures into the wilderness far from her home back East—a wilderness that, while eventually conquered and subdued by human hands, fights back at times with ferocious power. Letty Mason is traveling by train through the Western prairies to live with her cousin Beverly, his wife, Cora, and their children at their ranch in Sweet Water. Wirt Roddy befriends her on the train, and she is grateful for his company. Alarmed by the wind blowing against the train windows, Letty is warned by Roddy that she will not take to life out West as the wind will get to her: “Injuns call this the ‘land o’ the winds'—it never stops blowing here—day in, day out, whistlin' and howlin'—makes folks go crazy—especially women!” The train arrives at night, in a fierce wind, and Letty endures a long buggy ride through the wind and sand, driven by Lige (Lars Hanson) and his buddy Sourdough (William Orlamond), friends of her cousin. Lige tells her: “Mighty queer—Injuns think the North Wind is a ghost horse that lives in the clouds.” And as the buggy passes a herd of wild horses, there appears the stunning symbol of a white stallion leaping through the sky amid dark billowing clouds.

There is no mention in the intertitles that Sweet Water is in Texas. The Wind's production was headquartered in Bakersfield, California, in the Mojave Desert, and airplane propellers were used to stir the wind and sand to create the terrible storm. Not only were the demands of the role hard on Gish but so were the ever present sand and sawdust blown by the propellers, and the 120-degree temperature of the location in the Mojave Desert, not to mention the smoking sulfur pots that were used in the studio for visual effects during the filming of the storm.17 The Wind's landscape is whirling sand, a mise-en-scène as claustrophobic as those of Red River and The Searchers are broad and deep. Rarely do we see a vista of ranch lands and mountains, for the constant swirl of sand and then storm blot out the sun and sky. Ultimately we do not much notice or care whether this vague, nearly abstract setting is Texas or California. The claustrophobia is relentless as the constant wash of dust turns day into night, keeping the focus on the desolate horror of the earth.

Parallel to this earthly hell are the heavens of roiling clouds, through which the symbolic white stallion gallops furiously, presenting an Olympian atmosphere of an angry and capricious god that controls nature. In this way the landscape of The Wind serves to break the passage or journey of its heroine; it will entrap, surround, and torment her as much as any villain would do, its goal to seduce and destroy. The Wind may be the ultimate landscape Western, in which the forces of nature—an evil, resisting nature—are so great that the battle to obliterate light, air, and water makes it impossible for the “invaders,” the new settlers and ranchers, to survive in it. Most will surrender and leave.

FIGURE 8. Letty envisions a white stallion galloping in the sky over a desert landscape. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Both Roddy and Lige have proposed marriage to Letty. She goes to see Roddy, who confesses that he already has a wife but wants to take Letty where the wind can never follow her. Not having another choice, and although she thinks Lige's proposal a joke, she accepts Lige, only to find out on their wedding night that as a lover he is oafish and coarse. Letty does not want to live with him; Lige pledges not to touch her again and promises to find the money to send her back East. Letty hates being left alone in their rough shack of a home, where she is always sweeping away the sand. Lige agrees to take her to a meeting with other ranchers to discuss how best to save the cattle from the terrible drought, but her horse runs away with her in the wind, and after Lige rescues her she falls from his horse. Letty cannot stay out in the wind; she has to return to their ranch with Sourdough, who makes a few jokes before the men bring in Roddy, supposedly hurt. While Letty washes dishes with sand, Roddy asks why she is afraid of Lige leaving them alone together, and as the wind worsens he tries to seduce her. But Lige soon returns.

FIGURE 9. A distraught Letty cannot close her cabin door because of the windblown sand that has entered her abode. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

The wild horses are coming down the mountain by the thousands, and every man is needed to round them up. Lige says he is helping in order to get money for Letty, and Roddy leaves with him. But Roddy eventually drops behind and returns to the homestead as Letty shuts the door against the howling wind. The norther is coming: cattle break out of the corral, while inside the house objects are blown about and the lantern sways, casting shafts of moving light. Letty cowers in her bed, her eyes following the swaying of the light; she paces, the dog barks, objects bang, a window bursts, and the lamp is knocked over and causes a fire. Letty puts out the flames, stuffs the window with a blanket, and exhaustedly stares at the swaying lantern as everything seems to go back and forth. She sways too and is about to lose her senses when she hears a knock. Thinking it is Lige, she runs to open the door, and a smack of the wind blows Letty to the floor. Roddy enters, picks her up, and tries to make love to her. Letty runs out into the wind but is blown back again: she cannot escape, and when she sees the white stallion racing toward her, she falls into Roddy's arms and faints. He puts her on the bed and then bars the door as the white stallion, symbol of passion, gallops about in the clouds. His rape of Letty occurs offscreen.

The next morning Letty sits at the table as if in a trance, wrapped in her shawl, staring at a gun in its holster. Roddy cannot shut the door against the sand so he props it closed with a shovel, puts on his gun belt and tells her to pack, to go away with him before Lige comes back. When she refuses, he replies that Lige will kill them both, and she declares her hope that he will. As they scuffle and the dog barks, her shawl falls off; she is thrown against the table, picks up the gun, and aims it at him with both hands. Roddy smiles in condescension, moves toward her, then puts his hand on the gun to turn it away. She shoots, and looks at the gun in astonishment as Roddy falls dead. She then panics, grabs the shovel, and runs out to dig a hole in the sand so as to bury his corpse, pushing her shovel against the driving wind.

The films then cuts to Letty in the shack as she paces once more and looks out the window to see the sand blown away from the grave, revealing Roddy's head and his hands. As someone tries to enter, she picks up the gun and throws herself onto the bed in total fear. When Lige turns her over, he sees a madwoman. She confesses that she killed Roddy and points outside, but Lige sees nothing out there, nothing but sand. While Letty stands with her hair falling about her shoulders, Lige assures her that “if you kill a man in justice—it allers covers him up!” He holds her tenderly and promises that she will soon be far away from all this. Letty begs him not to hate her, not to send her away, crying out, “Can't you see I love you?” They kiss; the door blows open and lets in the blowing sand. Lige asks her if she will always be afraid. She exclaims, “I'm not afraid of the wind—I'm not afraid of anything now!—because I'm your wife—to work with you—to love you!” As in earlier silent Westerns such as Ford's Straight Shooting and 3 Bad Men, as well as Hart's Hell's Hinges, a moment of sudden (perhaps too sudden) self-transformation has occurred (see chapter 1).

FIGURE 10. Letty, fearful but determined, points a pistol to defend herself. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Gish's characters had endured seductions by unworthy lovers in Way Down East and The Scarlet Letter, not to mention her roles in which she was murdered by her father (in Broken Blossoms), imprisoned in the Bastille (in Orphans of the Storm), and subjected to a fatal disease (in La Bohème). Few actresses had perished or been rescued more dramatically. With The Wind, the movie business decided that Gish's character must save herself, and so it would be a few years before the desert enticed a character played by a major actress to plunge fatally into its vastness: Marlene Dietrich, starring in Morocco (1930). The studio's choice of a happy ending made Western movie sense at the time, at least to the bosses of MGM, even as it deprived the public of a thrilling if pessimistic climax that would have brought the melding of naturalism and melodrama to a brilliant completion. The insistence on a superficially happy ending kept the genre on hold during the transition to sound motion pictures. However unfortunate this may have been for the filmmakers, as for audiences then and now, the decision indicated it was not yet the moment for a more complex denouement that might take the Western tradition in new directions.

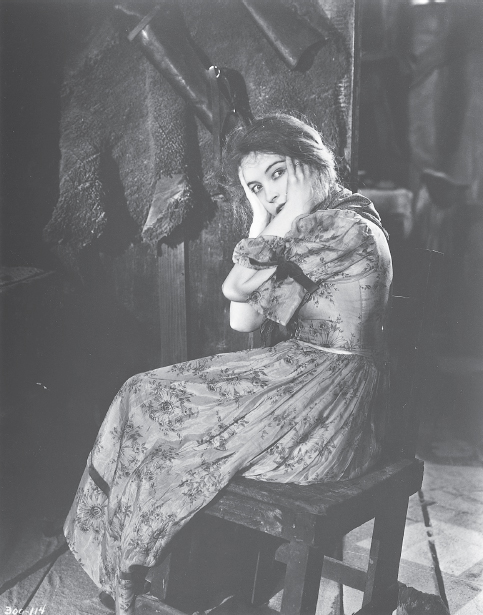

FIGURE 11. Letty cowers in fear at the verge of madness as she succumbs to the psychological effects of the ever-present desert winds. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art.

Letty, no less than the gunfighters later played by John Wayne in various roles or by Gary Cooper in The Virginian (1929), is a classic westerner: a survivor, exiled from her beloved South, moved to kill but exhausted by her ordeal, which she endures alone. She is preoccupied with all that she has lost and, by the end, faces the “reality” of a partnership with her husband in their desolate frontier home. Her giddy relief when Lige hears her confession of murder, and his unquestioning acceptance of her love—no matter that Letty is now damaged goods—are no more overly optimistic than are responses that Gish's characters are forced to make in numerous other films where an about-face in the final scenes is demanded. Letty is reconciled, by Hollywood standards. There being no production code of ethics at the time to dictate her punishment for murdering Roddy, rape appears to be sufficient justification, and Letty is easily forgiven. We cannot but wonder, nonetheless, at Letty's fate. She may have been through the worst, yet the wind will not fade and we cannot imagine that frontier life will improve anytime soon.

Following the release of the film and for years afterward, Gish and Marion complained about the forced “happy ending.” Gish said, “We all felt that it was morally unjust.” She blamed the exhibitors who insisted that the ending be changed after preview screenings of the film.18 Marion said that the eastern office had insisted on the picture having a happy ending, and she later recalled: “Lillian was sent for, the interior set was rebuilt, and the ‘happy, happy ending’ was photographed. Discouraged, Victor Seastrom and Lars Hanson returned to Sweden, and I made some genteel remark like, ‘oh, hell, what's the use?’”19

An analysis of Marion's numerous scripts for The Wind, however, refutes this claim. According to the existing scenarios of The Wind in the University of Southern California Warner Brothers Archives, there were six versions and a “New Ending Sequence.” The fifth and sixth versions, dated, by Marion, February 11 and February 14-27, 1927, include a prologue of scenes of Letty in Virginia with her grandfather, which depicts a countryside whose setting is “so beautiful that the memory of it will remain with us long after the scene is gone.” These scenes are not in the editing continuity list of October 22, 1927, in which the film begins with Letty's train ride west, when she meets Wirt Roddy and first encounters the eternal blowing of the wind. The drafts do have a happy ending, however, with Letty and Lige united by their love, and the “New Ending Sequence” of July 20 expands and alters earlier versions. Production ran from April 29 through June 24.

Thus we may conclude that the happy ending written in February was shot in the spring and revised in July. The ending was not simply created and “tacked on” at the last minute by studio directive. The editing continuity list includes the ending based on the July 20 sequence, and the final title list (of August 7, 1928) is identical to the continuity list of the previous October. The film was released in November of 1928, after further editing, and with an added sound track of music and effects, such as the wind and the barking of the dog, since MGM had begun to add music and effect tracks to films in 1928, in response to the success of the Vitaphone sound system introduced by Warner Brothers in 1926 and 1927.20

The film offers Letty no escape, only the choice of staying after conquering her fears. As we witness her sanity being diminished by the harshness of the Texas environment, we recall similar threats to the mental stability of such westerners as Tom Dunson in Red River and Ethan Edwards in The Searchers, both portrayed by John Wayne. In the former movie, Dunson's determination to cross Texas and reach a northern railroad town pushes him, a rancher leading a cattle drive, to become autocratic and excessive in carrying out his personal vision of frontier justice (see chapter 6). Edwards, wandering in the landscape for years, is obsessed with avenging the murder of his sister-in-law and destroying her daughter, his niece, who was taken by the Comanche warrior Scar as his woman (see chapter 8). Each of these westerners overcomes his lapse into madness but kills men along the way; each has his memories of the woman whom he once loved and who was murdered by Indians; each makes peace with a niece or adopted son; yet each is alone at the end.21

Letty, Dunson, and Edwards endure broken journeys and find, in their respective versions of a Hollywood resolution, that madness ends not with love but with reconciliation. Wayne's characters are allowed to struggle through long periods and endless terrain, driven by hatred and a determination to avenge.22 Dunson and Edwards can shoot and fight it out, their endurance is phenomenal, and their wounds only slow them down temporarily: their pursuit of revenge makes them strong. Letty, though she faints and is attacked by Roddy and the wind, finds similar strength to survive: she can shoot a gun, dig a grave, and bury a man single-handedly. But all has happened so fast. How is her psyche to cope, after months of isolation in a shack on the plains, with what has taken place in less than a day, with the terror of the storm, with rape and her vengeful response, with seeing the body revealed in the sand, all during the ceaseless howling of the wind? A natural reaction to such horror is a retreat into ruthless obsession and even madness. Like Dunson and Edwards, Gish's character survives her temporary insanity. After all, this is Lillian Gish and this is Hollywood. So the Letty of the film awaits her husband and a new chance for happiness, while we are cheated of perhaps Gish's greatest exit, her dash into the stormy desert, like the Letty of Scarborough's novel.

The Wind is classically Western in suggesting contradictions in Letty's character—her innocence and her sexual passion—that point to the fate she should have had. Throughout the narrative Letty is preoccupied by memory, fear, and desire. She has no impulse to take action, no urge to ride across the landscape to complete a cattle drive or a search while in pursuit of vengeance, as do Dunson or Edwards. Nor can she decide how to flee from evil pursuers, as do Jane and Bess in Riders or Lee Carleton in Ford's land-rush tale, 3 Bad Men. Instead, Letty is trapped in the wilderness, and all she can concentrate on is her desperate desire to be rescued from its evil hold over her and on her need of someone else to make possible her escape. Letty is passive, innocent, sensitive, and untrained for her duties as a frontier wife.

Jane Withersteen too suffers from her sincere goodness and from her naive trust in her fellow ranchers in Riders of the Purple Sage. Accordingly, the landscape might be viewed as punishing Jane by trapping Lassiter and Jane forever in an isolated valley. In the novel of The Wind, Cora is more complex and interesting as an archetype of the strong frontier wife, a beautiful and passionate woman as necessarily selfish as any man and just as devoted, like Jane, to her man's sexuality. The landscape cannot defeat her, for she is too domineering, too crude, and simply too forceful to be attractive to the elements. The wind and sand seem to prey instead on women who appear more vulnerable, and Cora likewise has no patience with those who are too weak, be they men or women—or so she proclaims in the novel.

The lesson to be gleaned from Cora's scorn is that women such as Letty should not leave their homes in “civilized” post-Civil War Virginia to endure frontier life in Texas until the land is settled. This is also Dunson's belief in Red River. He will not take his sweetheart, Fen, away from the wagon train to help him start his ranch, for he will not accept her statement that she is strong enough. She cannot persuade him, and his refusal is his biggest mistake: the wagon train is attacked soon after they part, and Fen is murdered (see chapter 6).

However, there are other eastern women who do go out West and overcome their obstacles and challenges. In The Virginian, the prototype of Western tradition for numerous later novels and films, Molly Stark, like Letty, crosses the country by train. She is heading to Medicine Bow to become the town's schoolmarm, and she then marries the hero. In Ford's Stagecoach, Mrs. Lucy Mallory (Louise Platt) travels from Virginia to Lordsburg to join her husband, a Union Army officer, because she is having a child and “won't be separated from him any longer.” Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs) heads out West in search of Doc Holliday (Victor Mature) and stays to civilize Tombstone as a schoolteacher in Ford's My Darling Clementine. And Olivia Dandridge (Joanne Dru), visiting from the East, decides to stay and marry a young cavalry officer in Ford's She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949).

It seems that the goal of Western expansion was to make Texas another Virginia, that symbolic heart of southern gentility where women were revered, cherished, and sheltered by their men. Sentimentally, if hardly historically, Virginia stood for a prewar, civilized America back East, while Texas was the raw frontier West. Texas had southern sympathies and, like Virginia, was a Confederate state during the Civil War. As the agrarian South used up its land in plantations of cotton and tobacco, Texas grass (before the discovery of oil) was grabbed for grazing by new generations of landowners, the cattle ranchers. But the attempt to transform Texas into another Virginia was, of course, a failed one, and The Wind has something to say at the metaphorical level about this failure. The drought and the norther in The Wind ruin the soil and decimate herds. And in the post-Civil War Texas of Red River, Dunson must drive cattle a thousand miles to the north because the war used up all the money in the South; the landscape alone can no longer sustain the economic way of life established by the ranchers, those who forcibly took the land from the Spaniards a couple of decades before the war. In The Searchers, Edwards's apology to Lars Jorgensen (John Qualen), the father of Brad (Harry Carey Jr.), who was killed by Indians, is cut short with the comment: “It wasn't your fault, it's this terrible country.” And near the end of the novel The Wind, Letty tells Roddy, “Oh, it wasn't Lige's fault! He's good. It's this country, this terrible country where it never rains, and no green things grow, and no birds sing!”23

Red River and The Searchers, both of which play out the notion that fate is character and landscape is fate, were made in the mid-1940s and mid-1950s, respectively, by which time audiences had become familiar with the Western narrative as a form of psychological epic. None of the Westerns produced before 1928 prepare us for The Wind's fierceness, its passion, and its unrelenting, swirling maelstrom of wind and sand. Gish lets us hear the wind through her gestures and expressions. We do not need orchestral cues to trigger our responses, to let us know that the wind is gathering force. In the thrilling scenes of Letty's panic during the storm, the film cuts rapidly to show us the dog barking, objects banging, and a window breaking. We sense the ferocity of the howling elements.

Tom Mix's 1925 film version of Riders of the Purple Sage does not approach the intensity of The Wind, but closer to the latter is Hart's Hell's Hinges, which provides a roaring climax of a town in flames (see chapter 1). Ford's Bad Men, like Riders' storyline, has two heroines pursued by an evil man, just as Letty is pursued by the malevolent Roddy. The narrative of Ford's film, however, is overloaded with a meandering melodramatic plot and underdeveloped romantic leads, emotionally engaging us primarily in the redemption of the three good bad men (see chapter 1). Perhaps only The Gold Rush, Charlie Chaplin's 1925 masterpiece and arguably a Western landscape film in some sense, pits its hero as excitingly against the elements and storms of the frontier, the Yukon snow country of 1898, as does The Wind. To be sure, The Gold Rush is a comedy, while The Wind veers toward the tragic throughout much of its running time. Sjöström's film is also the impressive precursor of such later “psychological Westerns” as Duel in the Sun, Pursued, The Furies, Jubal, The Naked Spur, and The Searchers—in addition to being the last great Western of the silent era.