5

The Commonwealth

The pandemic has laid bare a generation’s worth of poor choices and accelerated the consequences. The song remains the same: the rich get richer. The cost of a few garnering most of the gains is not just economic, it attacks the ballast of the U.S., our middle class.

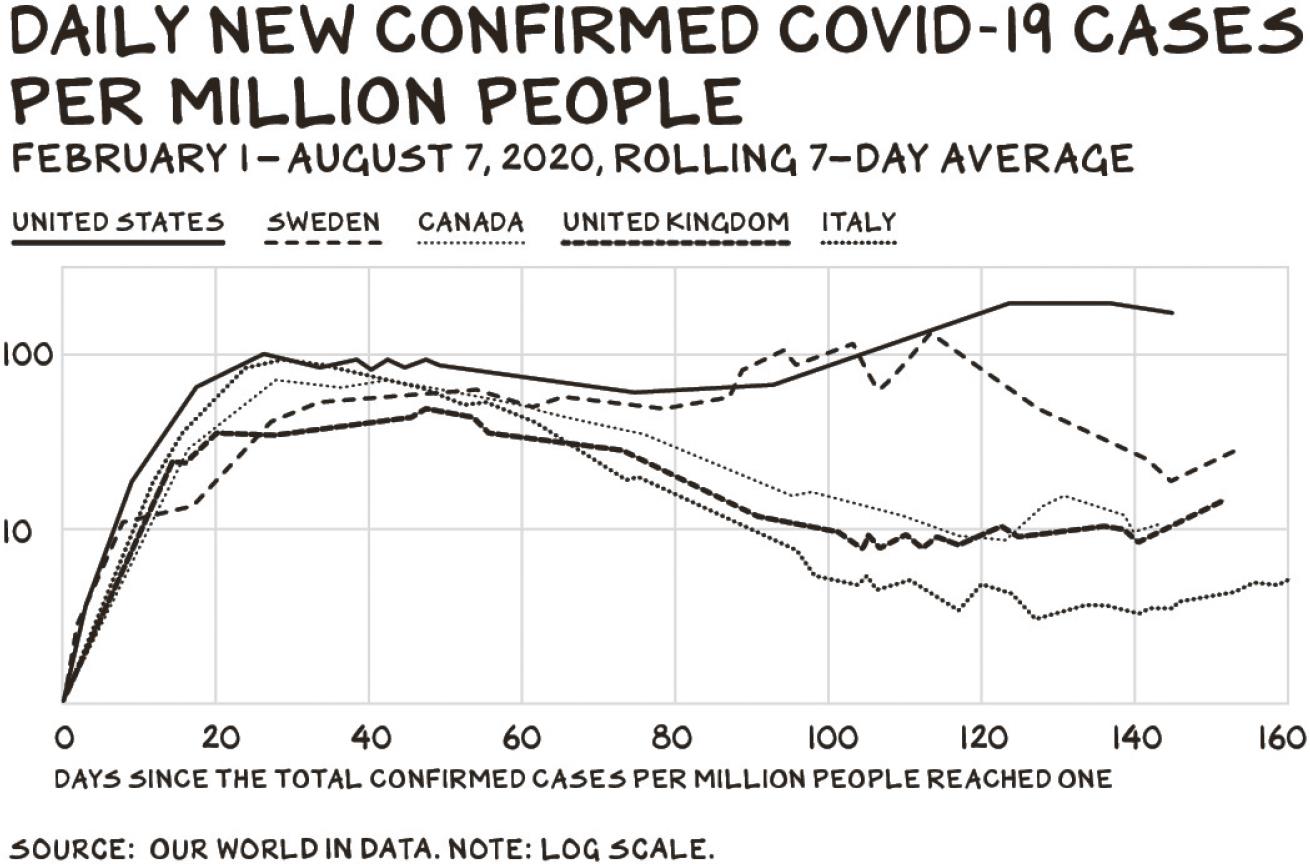

For forty years, we have engaged in a gross idolatry of private enterprise and the wealth it creates, while hollowing out government institutions and denigrating public servants. When the virus hit our shores, it found a society optimized for spread. Relative to our wealth and power, America’s handling of the challenge of this generation has been the worst in the world. In truth, we were sick already, riddled with comorbidities. Government agencies were weakened and science discredited. Individualism had become prized above all, resulting in a false conflation of freedom with a lack of civic duty and a refusal to bear minor inconvenience. Our muscles of collective sacrifice had atrophied so as to become feeble.

The prescription for the pandemic is the same as the prescription for our broader illness—a wholesale renewal of our sense of community. We must wrest our government from the hands of the shareholder class, which has co-opted it, and end the cronyism they have instituted to protect their wealth. We must set aside our idolatry of innovators and look unflinchingly at the exploitation it promotes. In short, we need to take government seriously—as a respectable, necessary, and noble institution—so that we can return to taking capitalism seriously, as a vibrant, sometimes harsh, but productive system that betters lives.

Capitalism, Our Comorbidities, and the Coronavirus

Capitalism has no equal as a system for economic productivity. It yokes our natural self-interest to the profit incentive, directing our creativity and our discipline toward maximizing economic return. It puts us in competition with one another to (remarkably) generate more choice and opportunity for each of us. The market near my house offers two dozen kinds of blue cheese, fifty craft beers, and three hundred varieties of wine. Ten times that is available on my phone. From my local airport, I can take a trip to the mountains of Colorado, the museums of Paris, or the beaches of Brazil, and be home in time to go back to work on Monday. My father in San Diego can video chat with his grandsons in Florida with the phone in his pocket (he doesn’t), and then pull up every novel ever written and every film ever made on that same phone. There’s even a pill to stop hair loss—little late. It’s an incredible life, and the spoils of success are worth working hard for. And that hard work stokes increased competition, generating more spoils, then more competition, and so on, and so on.

The chance to participate in a system that rewards smarts and hard work is a beacon for industrious and ambitious people globally. In Depression-era Scotland, my dad was physically abused by his father. His mother spent the money he sent home from the Royal Navy on whiskey and cigarettes. So, my father took a huge risk and came to America. My mom took a similar risk, leaving her two youngest siblings in an orphanage (her parents died in their fifties), and bought a ticket on a steamship. She had a small suitcase and 110 quid that she hid in both socks. Why? Because they wanted to work their asses off and apply that work to the greatest platform in history, America. They adopted American norms (hard work, risk taking, consumption, and divorce) and provided their son with the opportunity to teach 4,700 young adults, pay tens of millions in taxes, and create hundreds of jobs (#boasting).

That’s the trick of capitalism. By directing our ambition and our energy toward productive labor, it turns selfishness into wealth and stakeholder value. And ultimately, the wealth it creates becomes the spoils needed for productive altruism. On airplanes, we are told to put our own oxygen mask on before we assist someone else with theirs. That captures capitalism—get your own first, and put yourself in a position to help others. It’s selfishness that ultimately benefits others as well.

Capitalism leverages our species’ superpower: cooperation. In Sapiens, Yuval Noah Harari explains that unlike other species who can also cooperate (bees, apes, wolves), homo sapiens can cooperate at scale, “in extremely flexible ways with countless numbers of strangers. That’s why sapiens rule the world.”1 Though our motivations may be selfish, the bounties of capitalism are the product of coordinated effort across time and space by thousands, even millions of people. In early capitalist societies, machines and factories allowed dozens, then hundreds of people to combine their efforts into one unified force. Wealth creation accelerated to rates unknown in human history.

Today, we have the corporation. Unlike a factory, the corporation is an intangible, something that exists only in our minds and a Delaware court. Yet it has extraordinary power. It combines the physical labor of thousands of people with their organizational skill, insights, and ideas. When people coordinate efforts, the whole is vastly greater than the sum of the parts. The capitalist U.S. corporation is the most productive generator of economic wealth in history.

SOUNDS GREAT, BUT …

There are costs and risks to a system built on selfishness. Capitalism, despite what we have been told since the Reagan years, is not a self-regulating system. It doesn’t make people virtuous, or necessarily reward virtue. Professor Harari tempers his observation that cooperation permits sapiens to “rule the world” with the recognition that our next-of-kin chimps, also capable of cooperation, but not at mass scale, “are locked up in zoos and research laboratories.”

Capitalism in itself has no moral compass. The problems of unfettered capitalism are all around us. There are externalities: costs (or benefits) of activity that are not borne by an actor. Pollution is the paradigmatic externality. Acting purely for its profit-seeking self-interest, General Motors would pour the toxic waste it creates into the river behind the factory. That would mean less-expensive cars, but dire consequences for those who live and work downriver. That’s not to demonize GM. If it doesn’t get rid of waste in the cheapest possible way, its competition will, putting GM out of business with cheaper cars. Marx called this “the coercive law of competition,” and it has no exceptions for Good Samaritans.

And there are the problems of inequality. Employers, landowners, the wealthy, the monopolist all have substantial advantages over those they employ or compete with. That’s a natural and necessary aspect of capitalism, whose basic premise is that winners are rewarded and losers punished. Allowed to extend too far, however, those advantages lead to exploitation, dynasties, and the suppression of competition. Inequality is not in itself immoral, but persistent inequality is.

We don’t have to imagine this—the evidence is embedded in our society. Two hundred years ago we built an economy on Black slave labor. Today Black families have on average one tenth the wealth of white families.2 As we’ve noted, at many of our elite schools—passports to a better life—more students come from the top 1% of income families than from the bottom 60%.3 Research suggests that the most important factor determining an American’s life expectancy is the zip code they are born into.4

THE ROLE OF GOVERNMENT

As a society, we recognize that the long-term effects of these behaviors will impoverish all of us. Dead rivers eliminate fisheries, ruin farms, and poison our bodies. Class barriers prevent the best and the brightest from each generation rising to its fullest potential, thus denying all of us of the fruits of their labor. So we cooperate (we use our superpower) and create counterweights to an unchecked market: government.

Government’s charge is to stop GM from pouring toxic waste into the river. Indeed, by outlawing the wanton disposal of toxic waste, we allow GM to process waste in a more enlightened fashion, because we remove the threat that its competitor will take the cheaper route. We encourage GM to think critically about how it could redesign its processes to produce less waste. And we encourage entrepreneurs to start waste-processing companies, to develop new waste reduction and processing businesses. And we get cleaner, safer water, the benefits of which enrich everyone, including GM’s customers.

Likewise, it’s through government that we ensure the winners don’t rig the system in their favor. We regulate monopolies, or break them up, so that competition can flourish. We tax the winners to invest in the common good (education, transportation, pure research) and to defend against common threats (police and fire, military, natural disasters, disease). We build out a social safety net so that when corporations fail—a necessary part of the system—the mothers and fathers who worked for them can feed their families.

The libertarian argument, which is popular in tech today, is that this form of regulation and redistribution is inefficient, that left to its own devices the market will regulate itself. If people value clean rivers, the argument goes, they won’t buy cars from companies that pollute. But history and human nature show that this does not work. On a case-by-case basis, people will almost always take the cheaper alternative. Nobody wants to see children working eighteen hours a day in a clothing factory, but at the H&M outlet, the $10 T-shirt is an unmissable bargain. Consumer purchases are purposefully difficult to reverse engineer to bad actors. Nobody wants to die in a hotel fire, but after a long day of meetings, we aren’t going to inspect the sprinkler system before checking in.

As a species, we are not very good at attribution—connecting our individual actions with the broader world or thinking long term. As consumers, we use our fast thinking.5 So, we need government to slow our thinking, consider the long term, and register moral and principled concerns. Keeping these forces in balance—the productive energy of capitalism and the communal concerns of government—is key to long-term prosperity.

COMORBIDITIES

In January 2020, that balance was put to an unexpected but entirely predictable test. That we failed the test so spectacularly may have been unexpected, but it too was entirely predictable. Like the virus itself, the pandemic hit hardest where its victims have comorbidities. The pandemic has laid bare and accelerated the myriad mistakes we’ve been making for a generation.

In the name of cutting taxes, we have defunded government’s ability to serve the community. Disease kills far more people than war—we spend over $3 trillion treating people with chronic disease every year.6 Yet in 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s budget was just over $7 billion.7 That’s less than we spend on the military in four days. In January 2020, the neutered government agency that is supposed to protect us from global pandemics couldn’t develop an accurate coronavirus test.

ABANDONED

In a perverted expression of our exceptionalism, we’ve abandoned international cooperation and institutions. When the coronavirus first broke out in China, neither the WHO nor the CDC had sufficient staff on the ground to investigate the outbreak or coordinate with Chinese authorities. When it broke containment and spread to Europe, we shut down our borders and looked for scapegoats, even though the virus was already burning through the homeland, undetected by insufficient testing.

In the name of capitalism, we have allowed the wealthiest to enjoy returns on their capital that go untaxed, and have insulated those winnings from risk. As the pandemic tore through our economy, we poured money by the hundreds of billions into the coffers of big and small corporations, where it quickly found its way not onto the dinner table of those without work or sick from the virus, but into the bank accounts of the shareholder class. The result has been staggering unemployment, business closures, and economic instability the true cost of which will take years to play out. Meanwhile, the dirty secret of this pandemic, what we aren’t supposed to say out loud, is that the top 10% are living their best lives. Just by virtue of stock ownership, the wealthy are making trillions off the pandemic as the market touches all-time highs. The market reflects our belief that, post corona, the biggest, most successful firms (publicly traded firms) will survive, consolidate the market, and emerge stronger.

In the name of individualism, many Americans have refused to follow the call for sacrifice, from serious actions like canceling events and closing businesses, to the most trivial, including wearing a mask. If you want a symbol for how broken our conception of community and patriotism has become, it is in the politicization of masks. In the name of patriotism—a value rooted in shared sacrifice—millions of Americans have refused to engage in even this minor personal inconvenience. Refusing because it comes at the request of government, which we perceive not as the embodiment of our better instincts and the guardian of our future, but as an impediment to our desires, an oppressive force to be scorned and treated as fodder for our entertainment.

For years, we built up a notion of American exceptionalism that asserts that we don’t need a functioning government, that we don’t need to make sacrifices, that we don’t need to invest in our communities or in our future, that we don’t need to cooperate with other nations, and we are somehow immune from the threats that fell upon the rest of the world. By January 2020, we had built a society, America, perfectly designed for the spread and acceleration of a pandemic—the manifestation of our exceptionalism was no longer a robust and nimble government, but a belief that our exceptionalism itself would be an immunity.

How did we get here? How did we become so arrogant?

Capitalism on the Way Up, Socialism on the Way Down = Cronyism

The logical alternative to capitalism is socialism, and on its face, there is a lot to like. Socialism is rooted in altruism and humanism; it seeks to build up community rather than the atomized individual. These are noble goals. But the sacrifice in productivity is immense, especially with the compounding effects of time. Capitalism creates dramatically many more spoils, so any empathy has more to work with.

The toxic cocktail, however, is to combine the worst of both systems. For the last forty years, we’ve been doing this in the United States. We have capitalism on the way up. If you can create value in this country, you can be rewarded with spoils vastly beyond anything comparable in history. If you can’t create value, if you’re born into the wrong family or you catch a bad break—you’ll likely live on the edge and pay dearly for your mistakes. A Hunger Games economy.

Should you reach the heights of wealth (or more likely, be born into them), circumstances change. Despite our rhetoric about personal responsibility and freedom, we’ve embraced socialism—at the top and on the way down. We don’t tolerate failure here in our socialist paradise. Rather than let companies fail—a defining and essential feature of capitalism—we have bailouts. But bailouts are hate crimes against future generations, sticking our children and grandchildren with the resulting debt.

Crisis after crisis, our rationales vary: After 9/11 it was national security. In 2008 it was liquidity, and in 2020 it was protecting the vulnerable. But our response is always the same. Protect the shareholder class, protect the executive class. Keep these firms on life support so their owners and managers don’t suffer. Pay for it with debt, a burden to be borne by middle-class taxpayers and, ultimately, by our children. However, history tells us, nearly every bailout, whether it’s Chrysler or Long-Term Capital Management, only creates moral hazard that results in a bigger failure and a more costly bailout. Our $1.5 billion bailout of Chrysler in 1979 graduated to a $12.5 billion bailout, bankruptcy, and a sale to Fiat in 2009. The Federal Reserve’s 1998 intervention in the LTCM debacle gave Wall Street banks the confidence to take on even riskier strategies, with far greater consequences that would emerge a decade later. Every time, we’re told “this is different, historic … and requires intervention” and that taxpayers should bail out shareholders.

But so too is an 11-year bull market a historical event. That was the unique event that accrued unprecedented wealth to a fraction of the population. And the corporations that benefited didn’t save for a rainy day (which always comes), or pay it out to their workers so they could build up a protective cushion of wealth, or invest in capital projects that would grow the economy. Instead they poured it into dividends and stock buybacks, juicing executive compensation (from 2017 to 2019 the CEOs of Delta, American, United, and Carnival Cruises earned over $150 million in total compensation) and shareholder returns. Since 2000, U.S. airlines have declared bankruptcy 66 times. Despite the obvious vulnerability of the sector, boards and CEOs of the six largest airlines have spent 96% of their free cash flow on share buybacks. That bolstered the share price and compensation of management, but left these companies dangerously exposed to a crisis.

Now that the crisis is upon us, this small population of rich people has found socialism, and they have their hand out. That hand should go back in their damn pocket.

THE VIRTUES OF FAILURE

Failure, and its consequences, is a necessary part of the system. Economic dislocation and crises have real costs, but they are also opportunities for renewal. Old relationships are severed, assets are freed up, and innovation demanded. A forest fire brings life as it destroys—so too, economic upheavals create light and air for innovation to flourish. The 1918 influenza epidemic was devastating, but it was followed by the Roaring Twenties. The strongest businesses are those that are started in lean times. Wages rise after disruptions like pandemics—if the natural cycles of disruption and renewal are allowed to function.

We’ve let ourselves confuse corporations with the things they own and the people they employ. Corporations are simply abstractions. They feed nobody, house nobody, educate nobody. When a corporation fails, those who have risked their capital to support it lose their investment, but the workers are still capable of work, the assets remain available, and whatever need the corporation was filling remains.

As long as we keep making old people and younger people want to take their kids to Disney’s Galaxy’s Edge, there will be cruise lines and airlines. Let Carnival and Delta go into Chapter 11, and ships and planes will continue to float and fly, and there will still be a steel tube with recirculated air waiting for you post molestation by Roy from TSA.

Letting firms fail and share prices fall to their market level also provides younger generations with the same opportunities we, Gen X and boomers, were given: a chance to buy Amazon at 50 (vs. 100) times earnings and Brooklyn real estate at $300 (vs. $1,500) per square foot. As Thomas Piketty has pointed out, the high growth recoveries that follow economic shocks are periods of real wage growth, whereas slow and steady growth tends to favor the wealthy.

Once the government gets into the business of propping up the losers, you can predict who will be first in line for the handouts: the people with the most political power—corporations and rich people. It’s not just a matter of their lobbyists and their lawyers and their press flacks, though that’s a big leg up. There’s also something more insidious: cronyism.

MY DINNER WITH DARA

Why “cronyism”? I write about tech executives, but I mostly refuse to meet with them. In part because I’m an introvert and don’t enjoy meeting new people. But also because intimacy is a function of contact. Often when I meet someone, I like them as a person, feel empathy for them, and find it harder to be objective about their actions. Most senior people at successful companies are very smart, involved in interesting work, privy to inside baseball, and got where they are in part because they are good with people. I’m sure if I met more of them, I’d like them. That’s why I don’t meet with them. As Malcom Gladwell points out, the people who did not meet Hitler got him right. Easy to be charmed, even by someone so macabre, when meeting in person.

Not long ago I was invited to an “intimate” dinner with Dara Khosrowshahi, the CEO of Uber. His PR team was looking to spread Vaseline over the lens of exploitation that Uber levies daily on its 4 million “driver partners.” I turned it down. I met Dara once, years ago, when he was at Travelocity and I was pitching them on a company I’d started. He struck me as sharp and personable. I’m sure if I had gone to that dinner, I’d like him even more. And the more I got to know Dara, the more I’d like him, and the more I’d see Uber not as a legal fiction subject to the harsh law of the market, but as Dara’s company, imbued with Dara’s good traits.

I wish politicians would adopt a similar policy. It’s difficult for our elected leaders not to shape public policy around the concerns and priorities of the superwealthy when the wealthy few have much more access. It’s easiest to identify with those who are most like us and those we spend the most time with. It’s our tribal nature. But this sort of access is embedded in our system. And it goes well beyond orchestrated events like my dinner with Dara. The median wealth of Democratic senators is $946,000, Republican senators $1.4 million. They send their kids to expensive schools, they eat at expensive restaurants, they go on elite vacations. The people they see all around them are Uber executives, not Uber drivers. It’s only natural that they give Uber executives the benefit of the doubt, and have trouble focusing their attention on Uber drivers.

CRONIES GONNA CRONY

The federal government’s response to the pandemic has been true to form. Under the cloud cover of “protecting the most vulnerable,” we’ve handed trillions of dollars to the most powerful.

The $2-trillion relief package passed in March 2020 was a theft from future generations. Personal income was 7.3% higher in Q2 versus Q1 of 2020 because of stimulus payments and extra unemployment benefits. The personal savings rate hit a historic 33% in April, the highest by far since the department started tracking in the 1960s. The relief package included a $90 billion tax cut that benefited almost exclusively people making over $1 million per year.8 The richer you were, the more you gained. At the beginning of August, U.S. billionaires had increased their wealth a total of $637 billion.9 It appears, as has been the case for decades, that the only bipartisan action is reckless spending that benefits rich people while throwing some funds at the neediest for optics.

Not every dollar will be wasted. Maybe a third of it will go to the needy. A few local restaurants will be able to pay their employees and reopen when the pandemic recedes. A firm that provides airplane maintenance, a brand strategy firm, a locksmith—they could not have planned for the pandemic and will resume paying taxes and providing a service post corona. Those successes will be held up as evidence of the value of the bailout.

Except that the majority of the money we are asking our children to repay has done nothing but flatten the curve for rich people. Rich people have registered disproportionate benefit, their preexisting relationships with banks getting them to the front of the line. Look no further than the refusal of the administration to reveal who is getting the money—until after the election, of course.10

Instead of letting market failures play out, we propped up the shareholder class, using money stolen from the next generation. “We’re all in this together,” they tell us. Bullshit. The really ugly truth is this: for the wealthy, the pandemic means less commuting and emissions, more time with family, and more wealth (see above: markets at all-time highs).

Cronyism and Inequality

The obscene $2.2 trillion Covid relief package was just a symptom of our cronyism. The systemic flaw is that our government is no longer keeping capitalism’s winners in check. Instead, it’s a coconspirator in their entrenchment.

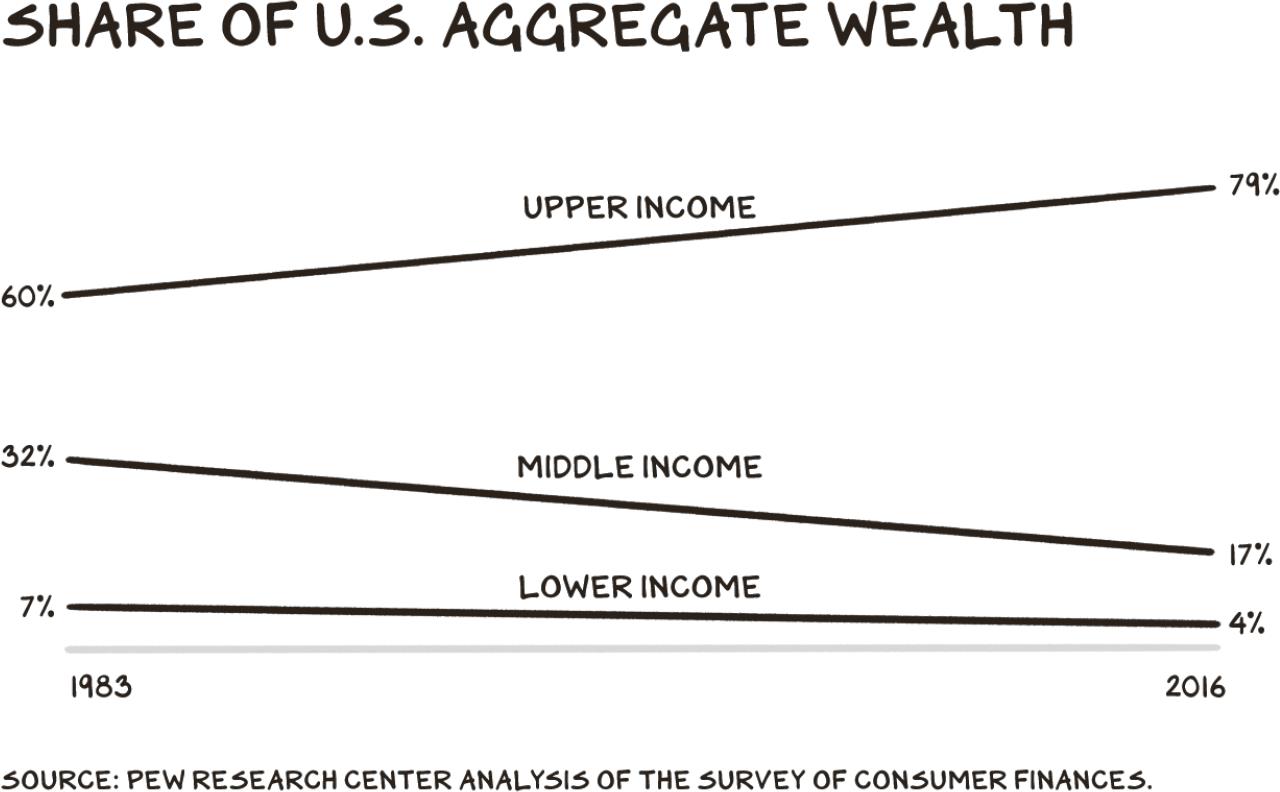

The wealthy have done well over the past few decades, in a supernova kind of way. A ton has been written on this, because the data is abundant. There is shocking data at the extremes: the top 0.1% now own more of the nation’s wealth than the bottom 80%.11 The three richest Americans hold more wealth than the bottom 50%. And there is bad news in broad strokes as well: since 1983, the share of national wealth owned by lower- and middle-income families has declined from 39% of the pie to 21%, while upper-income families have increased their share of national wealth from 60% to 79%.

For purposes of self-preservation, you’d think the rich would be concerned with this level of income inequality. At some point, the bottom half of the globe by income realizes they can double their wealth by taking the wealth of the richest 8 families, who have more money than 3.6 billion people. Here in the U.S. the bottom 25% of households (31 million families) have a median net worth of $200.12 Most recently, a group of protesters built a guillotine outside the Manhattan home of Jeff Bezos to commemorate his wealth passing $200 billion.

This trend is only getting worse. Once, we elected leaders who cut the tops of trees to ensure saplings get sunlight. Today there is less and less sunlight. A recent study of historical tax-return data concluded that the uber-wealthy paid a tax rate of 70% in the fifties, 47% in the eighties, and 23% at present—a lower tax rate than the middle class. Whereas poor and middle-class tax rates have largely stayed the same.

We’ve exploded the debt so rich people pay less tax. Money is the transfer of work and time, and we’ve decided our kids will need to work more in the future, and spend less time with their families, so wealthy people can pay lower taxes today.

My own experience provides a case study in how the wealthy lock in their gains. When I sold my last company, L2, in 2017, I paid an effective tax rate of 17–18%. I paid 22.8% federal, but the first $10 million were tax free, thanks to Section 1202 of the tax code. Section 1202 is a tax break for early shareholders, meant to encourage start-ups. Only it’s nothing but a transfer of wealth from other taxpayers to venture capitalists and founders. No entrepreneur starts, or doesn’t start, a business because of the tax code. It takes a special kind of crazy to start a company and a lot of talent, work, and luck to build it to be something you can sell for millions of dollars. The decision has nothing to do with the tax code. Tax breaks for the successful are just another way we deepen inequality.

Once people make the jump to light speed, advantages like this let them pull away. Access to more resources, investment opportunities, lower taxes, tax specialists, political contacts, friends who can help your kid get into school, and the wheel spins. It’s never been easier to become a billionaire, or harder to become a millionaire.

ECONOMIC ANXIETY

Proponents of unfettered capitalism shrug off the ever-increasing advantages of the wealthy and trust a rising tide lifts all boats. They rest easy knowing that working-class Americans may not have secured the same portion of our recent prosperity, but their lives are nonetheless better than they were a decade, a generation, or a century ago. This profoundly misunderstands the nature of economic security.

In 2018, 106 million Americans lived below twice the federal poverty line, which is not as nice as it sounds. Twice the poverty level for a family of four is a household income of $51,583.13 That population has increased at twice the rate of the population as a whole since 2000. Most of them spend more than one third of their income on rent. A third do not have health insurance, despite being disproportionately sick or disabled.14 Many carry the burden of unmanageable debt, which can lead to deaths of despair. People who take their own life are eight times more likely than average to be in debt.15 For every 100 points your credit score increases, your risk of dying in the next three months declines by 4.4%.16 In the U.S., money is literally life.

Economic anxiety was the sound track of my childhood—a static noise in the background. We were never well off, and after my parents’ divorce, economic stress turned to economic anxiety. It gnawed at my mom and me, whispering in our ears that we weren’t worthy, that we’d failed. Our household income was $800 a month when my parents split. My mom, a secretary, was smart and hardworking. Soon, our income increased to $900 a month, as she got not one but two raises—the munitions in the battle of me and her against the world. I told my mom, at the age of nine, that I didn’t need a babysitter, as I knew we could use the additional $8 a week. Also my sitter was a religious freak who, when the ice-cream truck came by, gave each of her kids 30 cents and me 15.

The winter of my ninth year, I had no suitable jacket, so off to Sears we went. The jacket cost $33, nearly a day’s pay for my mom, I knew. We bought a size too big, as my mom figured I could go two, maybe three years with this jacket. What she hadn’t counted on was that her son loses things. All the time.

Two weeks later, I left the jacket at my Boy Scouts meeting, but I assured my mom we’d get it back at the next meeting. We didn’t. So, off to JCPenney to get another jacket. This time my mom told me the jacket was my Christmas present, as we couldn’t afford gifts after buying another jacket. I don’t know if this was true or if she was trying to teach me a lesson. Likely both. Regardless, I tried to feign excitement at my early Christmas present. A few weeks later, though, I … lost the jacket.

That day, I sat at home after school, waiting for my mom to come home, feeling the body blow I had delivered to our economically distressed household. Yes, it was just a lost jacket, but I was nine. And the point is not that I had a hard life—I didn’t, by any reasonable measure. The point is that it was just a jacket. But my sense of economic anxiety was already so finely tuned that the loss of a jacket was chilling. I will never forget that feeling of dread and self-loathing I felt that day.

“I lost the jacket,” I told her. “It’s okay, I don’t need one … I swear.” I felt like crying, bawling really. However, something worse happened. My mom began to cry, composed herself, walked over to me, made a fist and pounded on my thigh several times. As if she were in a boardroom trying to make a point, and my thigh was the table she was slamming her fist on. I don’t know if it was more upsetting or awkward. She then went upstairs to her room, came down an hour later, and we never spoke of it again.

I still lose things. Sunglasses, credit cards, hotel room keys. I don’t even carry house keys, why bother? The difference is that, now, it’s an inconvenience, quickly addressed. Wealth cushions the small blows—lost jacket, an overlooked electric bill, a flat tire—while insecurity magnifies them. Economic anxiety is similar to high blood pressure. Always there, waiting to turn a minor ailment into a life-threatening disease. Indeed, it’s literally high blood pressure: kids who live in low-income households have higher resting blood pressure than kids who live in wealthy households.17

The New Caste System

It’s not novel to point out that it’s good to be rich, or that it’s bad to be poor. Perhaps the ambition and drive that powers capitalism needs the spur of poverty to keep it moving. But the fundamental promise of America, of any just society, is that with hard work and talent, anyone can lift themselves up, up out of poverty, up into prosperity. And that promise has been broken.

Study after study has found that in today’s America, the biggest determinant of an individual’s economic success is not talent, it’s not hard work, and it’s not even luck. It’s how much money their parents have. The expected family income of children raised in families at the 90th income percentile is three times that of children raised at the 10th.18 Economic mobility in the United States, on a range of measures, is worse, in many cases much worse, than in Europe and elsewhere.19 Want to live the American dream? Move to Denmark.20

This isn’t just a story about the poor or billionaires. At every level, it’s getting harder and harder to move up. My first house in the Potrero Hill neighborhood of San Francisco was $280,000. Divide that by the $100,000 average starting salary out of business school in 1992 and you end up with a ratio of 2.8 for the price of housing compared to average salary. Now the average salary is $140,000. That’s a lot of money. But the average home in the Bay Area now costs $1.4 million. So, we’ve gone from a ratio of 2.8 to a ratio of 10. This is for the nominal winners, the people who thought they were joining the elite. It’s harder now.

The result is a society in which there is tremendous prosperity, but little progress. The Declaration of Independence promises us “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Yet study after study finds that Americans live shorter lives,21 are less free,22 and less successful in our pursuit of happiness23 than our European counterparts.

PRIVATE DISNEYLAND

These inequalities are rooted in the tax code, our education system, and our woeful social services. Now they are embedding themselves in our culture.

When I went to Disneyland when I was a kid, there were rich kids, middle-income kids, and lower-income kids. My best friend was a Mormon kid going to Stanford. My other friend, from a wealthy family, was going to Brown. And my other friend, a Black kid from the inner city who had no money, was trying to go to a mediocre college in Oregon on a football scholarship. And we all experienced the same Disneyland. We all paid $9.50 for our ticket books. We all hoarded our “E” tickets and waited 45 minutes in line for the Pirates of the Caribbean. We all had a similar experience at Disney.

Now Disney says, for those of you who don’t have a lot of money, it’s $119. You eat mediocre food, and you wait in line. For those of you who are a little wealthier, you can pay $170 and get something called a FastPass. And instead of waiting an hour for the Pirates of the Caribbean, you only wait ten minutes. And for those of you in the 1%, you can do a VIP tour. For $5,000 you and six friends get a tour guide, lunch in a special dining room served by costumed characters, backstage access, and not only do you get to cut the line, you go through an employee entrance.

ON EDUCATION, AGAIN

Okay, but Disneyland was never supposed to be a communist utopia. It’s free enterprise, right? Perhaps, although I’d argue that making rich kids wait in line at Disneyland probably had some salutary effects on their altruism, sense of empathy, and ability to handle irritations. But if Disneyland adopting a caste system doesn’t bother you, consider this. Read that passage again, only replace every mention of “Disneyland” with “college.” It’s the same. Higher education was supposed to be the great uplifter, the antidote to capitalism’s tendency toward classism. But higher education in the U.S. has morphed from the lubricant of upward mobility to the enforcer of our caste system.

What changed my circumstances from crying over a lost jacket, to laughing when my son loses his (“just like your dad”), was the University of California. When I graduated high school (with a 3.2 GPA), the acceptance rate at UCLA was over 60%. I still didn’t get in on my first try, but an empowered admissions official took pity on my appeal. That moment of grace, and the generosity of California taxpayers that made it possible, has been the foundation of my success. From UCLA I secured a job on Wall Street, and then admission to UC Berkeley’s business school. I met my first wife at UCLA (still friends), and it was her income that gave me the flexibility to cofound Prophet and Red Envelope. I met my business partner at Berkeley, and without him neither of those companies would have made it out of my head. One of my professors at Berkeley, David Aaker, became a mentor, and his association with Prophet opened the early doors that enabled our early success.

More than any other single factor, it’s access to higher education that has been the secret to my success. The firms we’ve started have generated over a quarter of a billion dollars for investors, employees, and the founders. These firms employ hundreds of people—and neither of my parents went to college, but America wanted their kid to attend. Yet as I detailed in chapter 4, that path out of economic anxiety is getting steeper and narrower. In 2019, the acceptance rate at UCLA was 12%. Put another way, it’s five times as difficult to access the upward mobility that was within reach three decades ago. A rich society should make it easier for the next generation to get ahead, not harder. A privileged few are riding the Pirates of the Caribbean over and over, while the masses are standing outside in the sun waiting for a turn that may never come.

WEALTH PRIVILEGE

We don’t see the depth of our dilemma because we’ve bought into myths about America, meritocracy, and success. We’ve put billionaires on a pedestal and made wealth the signifier of worth—and it’s to be rewarded with … more wealth.

Don’t look to the wealthy to arrest this trend. We love being told our success is the product of our own genius. After serving on seven consumer, media, and technology public company boards, my experience is that if you tell a thirty- or fortysomething person who wears black turtlenecks that they are Steve Jobs, they are inclined to believe you.

CARTOON

There is a cartoon that very wealthy people are generally assholes. They are not. My experience is that most very successful people have a few things in common: grit, luck, talent, and a tolerance for risk. Sure, there are rich kids, but in general this cohort may be the hardest-working cohort of any segment. They receive more return (economic and non-economic), so there are greater incentives, but there’s no escaping it—if you’re planning on being a billionaire (and don’t have billionaire parents), you should plan on working for the next 30 years … and not much else. I’m not pushing hustle porn—the jobs that create multimillionaires are just extremely demanding. I’ve also found that most of the superwealthy are patriotic, generous, and genuinely concerned about the commonwealth. That makes sense, as to reach the pinnacle of success, it helps to have people pulling for you.

But wealthy people are not going to disarm unilaterally. Like anyone else, the 0.1% will use their skills and resources to ensure their firm has an advantage over others, that their children have an advantage over others, even if that means turning a blind eye to externalities (environmental standards, monopoly abuse, tax avoidance, teen depression). We all want the best for our kids, and our system gives us the option to buy a better education, to pay for better cultural development, and to provide more opportunity for our offspring. Most everyone cares about the long-term health of our society, but first we focus on ourselves and our own.

Conflating luck and talent is dangerous. The Pareto principle posits that even if competence is evenly distributed, 80% of effects stem from 20% of the causes. As I get older, I’m struck by how big a part luck played in my life—being born in the right place at the right time—and how much I mistook it for skill. Coming of professional age as a white male in the 1990s was the greatest economic arbitrage in history. Today’s 54-to-70-year-olds saw the Dow Jones increase an average of 445% from 25–40, their prime working years. For other ages, it doubles at most.

That growth meant more opportunities—opportunities that were sequestered to a specific demographic (see above: white males). In 1990s San Francisco, between the age of 34 and 44, I raised over $1 billion for my start-ups and activist campaigns. I didn’t know a single woman, or person of color, under 40 who raised more than $10 million.

And it seemed normal. Even today, white men hold 65% of elected offices despite being 31% of the population.24 Eighty percent of venture capitalists—the gatekeepers of the entrepreneurial economy—are men, and most of them are white. Is it any wonder that founder-CEOs, from Bill and Steve to Bezos and Zuck, are overwhelmingly white men too?

The difficult thing about a meritocracy—or what we think is a meritocracy—is that we believe billionaires deserve it and that we should idolize them. Our idolatry of innovators blinds the winners to the structural advantages and luck they benefited from. And it fools us into thinking we are just a few lucky breaks from joining them. Sixty percent of Americans believe the economic system unfairly favors the wealthy25—but, as John Oliver points out, we tolerate this, because we think, “I can clearly see this game is rigged, which is what will make it so sweet when I win this thing.”26 Then we wonder why veterans are urinating on Market Street and why 18% of children live in households that are food insecure.27

The greater our differences economically, the more we come to believe we are different in more fundamental ways. Altruistic behavior decreases in times of greater income inequality. The rich are more generous in times of lesser inequality and less generous when inequality grows more extreme. Michael Lewis writes, “The problem is caused by the inequality itself: it triggers a chemical reaction in the privileged few. It tilts their brains. It causes them to be less likely to care about anyone but themselves or to experience the moral sentiments needed to be a decent citizen.”28 Privilege looks in the mirror and sees nobility. Financially successful people come to believe that someone who is delivering groceries at $14 an hour or cleaning the subway car deserves their economic fate. They’re not as smart, they’re not as good, they’re not as worthy as the rest of us.

Worse, those not blessed by circumstance and luck hear the message loud and clear. Lack of economic success is their fault. This is the land of opportunity, where anyone can make it big, right? So what does that say about those who don’t?

When we put the 0.1% on a pedestal, we crowd out teachers, social workers, bus drivers, and farmworkers from the respect that is due to them. We tell them they are less, that they have failed. That any economic disadvantages they face are their fault, their birthright even. That’s not capitalism, that’s a caste system—and the inevitable result of cronyism, which requires these myths to entrench the power of the 0.1%.

This is why we need a strong government, to counter human nature, to balance fast thinking and selfishness with slow thinking and community. We don’t need to make idols of the wealthy to inspire achievement. Wealth and success are motivation enough. We are not dressing billionaires up as heroes because they need better marketing. We are dressing them to obscure the truth—that while innovation still happens, and hard work still exists, an ever-increasing share of the spoils are not going to the innovators but to the owners.

CORPORATIONS ARE (RICH) PEOPLE TOO

What’s happening at the individual level is also happening at the corporate level. Just as we have tilted the tax code toward the shareholder class, large corporations have co-opted the government agencies that are supposed to constrain their power.

Why does this matter? It kills innovation and job growth. Nearly twice as many new companies were formed each day during the Carter administration as are formed now.29 That tax-free $10 million hasn’t birthed new companies, it’s destroyed them. In markets dominated by one of the Four, early-stage venture investors are increasingly uninterested in funding an insect to splat into the windshield of a monopoly.

Unthreatened by meaningful competition, supplied with near-infinite cheap capital, and enjoying the power of a flywheel to gain advantage in any industry they enter, big tech is no longer motivated to innovate. They have a much more lucrative profit opportunity: exploitation.

The Exploitation Economy

In the past decade, we have transitioned from an innovation economy to an exploitation economy. Innovation is dangerous and unpredictable. It changes market dynamics and creates opportunities for nimble new players to steal share from established players. None of that is attractive to an entrenched market leader. Why should Apple “Think Different” when the way it’s currently thinking has made its shareholders over $1 trillion dollars in the past 12 months (ending August 2020)?

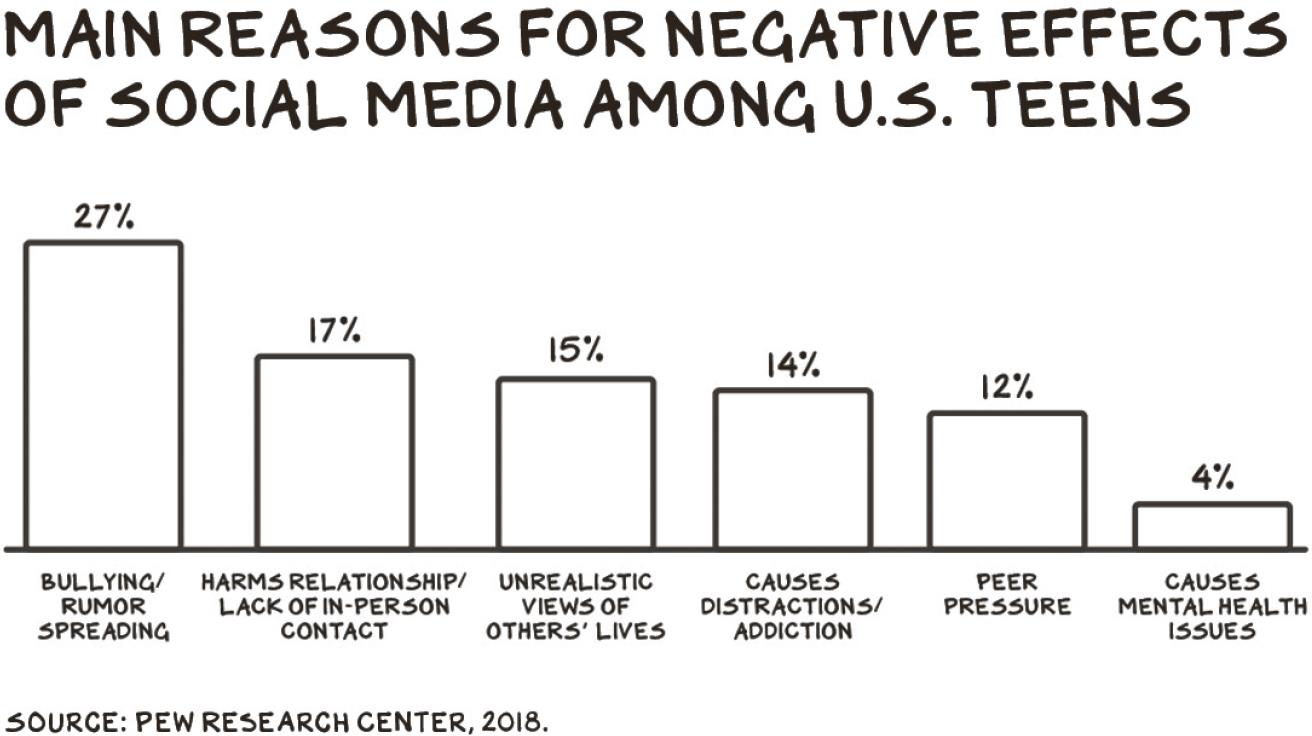

The firms that have grown shareholder value by hundreds of billions in a short time have arbitraged the inability of our government, and our instincts, to keep pace with technology. On the other side of the billions of shareholder value captured by increasingly few from social media, trading, or ride-hailing apps are millions of depressed teens, election interference, and a decrease in the dignity of work (no health insurance, sub-minimum-wage compensation).

Dominant firms exploit everything they touch, starting with their own workers. The pandemic revealed Amazon’s attitude toward its “essential” warehouse workers. Workers walked out, started petition drives, and made internal complaints about Covid risks and unsafe conditions. In response, Amazon … fired the fulfillment center worker who organized a walkout.30

Uber has figured out how to run a massively asset-intensive business without assets. Instead it puts the responsibility of buying and maintaining its assets on driver partners that it fights tooth and nail to avoid classifying as employees, so that it doesn’t have to provide health insurance or pay minimum wage. California Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) extends employee classification status to gig workers because, well, they are employees. In response, the gig industry put together Proposition 22 for voters to decide on this November. The bill, as you might suspect, suspends AB5 and creates a new, less costly classification. The “No on 22” campaign raised $811,000, mostly from labor groups. “Yes on 22” has raised … $110 million.31

Uber’s model is brilliant, and absurd. Imagine if United Airlines told flight crews that if they wanted to make that day’s JFK to LAX run, they would need to finance the airplane, fuel it up, and stock it with in-flight snacks, and then get a revenue split. One might argue it’s simply the franchise model. Most franchises pay 4–8% to the parent—Uber takes 20%.

If there was any doubt that Uber’s business is untenable in a world where its drivers make minimum wage, it vanished in August when the company admitted that it would have to limit its business to denser urban areas if it were required to classify its “driver partners” for what they are: employees.32

The biggest companies are increasingly getting their profits from exploiting another fertile target—their own consumers. There’s no such thing as a free social network app. Instead, companies are increasingly using algorithms to leverage our weaknesses as a species. Most disease and hardship for our species has been a function of scarcity—too little salt, sugar, fat, approval, safety, opportunities to mate. As a result, when we find these things, our brain produces the ultimate reward, the pleasure hormone dopamine. And it makes sense: Nature rewards behaviors that ensure the survival and propagation of the species.

SUPERABUNDANCE

The assembly line, processing power, and Amazon Prime have not only met the minimum thresholds for survival but created a new threat to our species: superabundance. Diabetes, income inequality, and fake news—all are a function of our belief that more is better.

Survival, propagation, and consumption should result in a next generation that’s smarter, faster, and stronger. Where things have come off the rails is a function of our innovation economy moving faster than our instincts. Historically, humans have engaged in activities that have natural stopping cues—no more apples on the tree, no more ale in the barrel, the end of a chapter, the end credits. Platforms including Facebook, Instagram, and Netflix have systematically eradicated stopping cues—similar to casinos, which deliberately have no hard angles, only one continuous space to keep you moving through it, on to the next wager. Netflix has become an endless show; TikTok, an endless video.

Technological progress lapping the calibration of our instincts culminates in endless scroll. We’re unable to find the off switch. Unlike our parents and grandparents, for us dopamine release no longer depends on sacrifice, engagement, or grit, but on sitting still, as in 4, 3, 2 seconds episode 5 of Killing Eve will begin. There are more filtered photos, more porn, more equities, more margin, more dopa … more time without the nuisance of needing to engage in … life.

Taking away barriers is just the beginning. Adding artificial incentives, known as gamification, is what’s next. The latest industry to discover this particular form of digital crack are online trading platforms (OTPs). What does endless scroll look like on a trading platform? Download Robinhood (at your own risk):

- Confetti falls to celebrate transactions

- Colorful candy crush interface

- Gamification: users can tap up to 1000 times per day to improve their position on the waitlist for Robinhood’s cash management feature (essentially a high-yield checking account on the app)33

This discrepancy in modulation has exploded our levels of teen depression and social chaos.34 We are in a Supermarine Spitfire, accelerating every day, hoping the fuselage holds together as we approach the sound barrier—streaming 31 seasons of The Simpsons, lifelike video games, ubiquitous porn of increasing extremes, high-def documentation in real time of the party your 15-year-old daughter wasn’t invited to, social media algorithms fueled on outrage vs. veracity, and immediate approval of margin for a “bull put spread.”

We saw the ultimate cost of this manipulation in June 2020 with the suicide of a 20-year-old from Naperville, Illinois, named Alex Kearns. Alex was interested in the markets and began trading stocks on Robinhood. Then, no doubt encouraged by how easy Robinhood made it, he started trading options. Then, not understanding the complex rules of this particular crack deal, he thought he was down $730,000. Seeing no way out, Alex took his own life.

Robinhood users skew young (32% of visitors are 25–34 years old). The firm reported 3 million new accounts in Q1 2020. Half were first-time traders.35 In addition, with Vegas and sports wagering all but shut down in the early months of the pandemic, OTPs have become the place where emerging gambling addiction can take root—a rehab facility where your sponsor is a dealer. How many of those $1,200 stimulus checks were levered up and went straight to OTPs?

The bulk of the pressure to protect kids from device addiction falls on parents—limiting use (severely) and getting other parents at school to limit use as well, so kids don’t feel cized. It’s difficult, and needs to be done. An “electronics fast,” perhaps for the whole family, can allow the nervous system to reset. Lowering your dopamine threshold allows a smaller amount of pleasure to be satisfying.

The threat of addiction has been slowing our household down. One of our sons demonstrates behavior consistent with device addiction. It’s terrifying. Everything he does, says, and works toward is in pursuit of the dopa hit waiting on his iPad. His mom and I are doing what most parents would do—reading, seeking outside help, limiting use. But more than anything, we’re trying to slow things down. Time with him, especially outdoors or with books. Time in bed with him telling him stories about his grandfather becoming a frogman in the Royal Navy. Slowing everything down. It appears to be working.

I see Alex Kearns, and I see my oldest son. A nerd with a big smile, fascinated by the markets and seeking dopa hits. I can’t imagine the pain of that family. I can’t imagine how we’ve lost the script, letting the meaningful, innovation and money, trump the profound, our kids. The youth suicide rate has increased 56% in a decade.36 Girls between 10 and 14 had a tripling of self-harm episodes between 2009 and 2015.37 Teens who are on social media for 5+ hours a day are twice more likely to be depressed than those who are on for less than an hour.38

Is it any wonder Tim Cook doesn’t want his nephew on social media? If he wasn’t Tim Cook, would he also say, I don’t want him to have an iPad either?

Take Government Seriously

I have benefited a great deal from the private markets. The freedom to follow optimism, some native talent mixed with a lot of luck, and hard work have yielded a set of professional experiences and economic security my parents wonder at, but can’t fathom. At the same time, the government has given me more. The University of California was essential, as were my public primary and secondary schools. So was the rule of law that kept our businesses safe and contracts enforceable. So was the government-funded physical and digital infrastructure those businesses were built on.

Government—like private enterprise—can be inefficient and ineffective. But as Yale Law professor Daniel Markovits, author of The Meritocracy Trap, points out, government can also be incredibly efficient. A family with $60,000 annual income pays about $10,000 per year in taxes. In exchange, that family gets roads, public schools, environmental protection, national security, fire, and police—try assembling that as a package of private services and see what it costs you. That same family probably pays $3,000 a year to the Comcast Corporation for cable, internet, and mobile. Cable sucks, and the internet speeds in the U.S. are inferior to other advanced nations. In other words, government can be very efficient when we work together.39

Yet over the course of my lifetime, it has become fashionable to denigrate government, to deny its contributions to the commonwealth. At first, during the Reagan revolution, it was an enemy, a repressive force to be beaten. Then we stopped giving it even the respect of a worthy adversary. In 2016, the election of a reality television star as president was the fulfillment of a long-term trend. We equate government to an entertainment product. Like the NFL, but more dangerous, and year-round. We join either Team Red or Team Blue, and then we watch our teams give each other Parkinson’s.

Our contempt for the government has become an investor relations strategy. On August 20, software firm Palantir sent financial documents to its investors in advance of its planned IPO. In the filing, the firm states its strong ties to government contractors were an opportunity, citing the “systemic failures of government institutions to provide for the public.”40

“We believe that the underperformance and loss of legitimacy of many of these institutions will only increase the speed with which they are required to change,” said the firm … backed by Peter Thiel, the guy who backed Facebook, the firm that has done more than any other to contribute to that “loss of legitimacy.”

Think about this. Only big tech is arrogant enough to assure investors its biggest customer will buy more because it’s just so damn incompetent. Imagine Accenture telling investors it sees increased demand for its services because corporate America is just plain stupid. It’s true the federal government has not demonstrated fiscal competence. In 2020, the U.S. will spend a third more than it collects ($4.8 trillion vs. $3.7 trillion).41 However, according to its investor documents, Palantir registered losses of $580 million on $743 million in revenues, meaning it spent $1.32 billion, or two thirds more than it took in.

Perhaps Uncle Sam should be advising Palantir.

YOU GET WHAT YOU PAY FOR

Our disrespect translates to our fiscal priorities, and renders our dismissal of government a self-fulfilling prophecy. We don’t pay teachers enough, our schools suffer, and we lose respect for public schools. We don’t pay government scientists and researchers enough (and we don’t listen to the ones we do hire), and the best and the brightest go instead to Google or Amazon. Then we ask the DOJ and the FTC to restrain these corporate titans, but we tie their hands, allocating a fraction of the resources private companies deploy. Amazon has more full-time lobbyists in DC than there are sitting U.S. senators.

TEST KITS

The pandemic has feasted on our disrespect. The wealthiest country in history, and we couldn’t produce a working coronavirus test kit for months. Government scientists were sidelined, and partisanship swamped sense. Team Blue hates Team Red because they are putting grandparents in danger by not wearing masks. Team Red hates Team Blue because they are infringing on liberty and threatening the economy over something that hasn’t impacted anyone they know. Then, once the virus overwhelmed us, we concocted a flawed economic bailout program. Red-state governors and blue university chancellors opted for politics and money over the health of the country and reopened prematurely.

ON THE KINDNESS OF BILLIONAIRES

If we want a better government, we should stop sending eighth graders into the NFL. Our idolatry of the rich convinces us that we need a “businessperson” to “straighten out” Washington. But running a business is not serving in political office, and our best presidents have been, not surprisingly, politicians. Followed by military leaders. Presidents whose primary pre–White House careers were in business (Harding, Coolidge, Trump) have been markedly less successful.

There are many reasons for this. One is that business teaches us to always look for the advantage, not to give anything away without getting more in return. That’s the antithesis of government (and government service), whose purpose is to contribute to the commonwealth without recompense.

We should not rely on billionaires to save us. When your house is on fire and the wealthy guy from down the block shows up with a better hose to put out your fire, that doesn’t mean we need more rich people on the block. It means we need to fund the fire department.

Philanthropy is less reliable and less accountable, and it doesn’t scale well. Yet in the pandemic we look to Bill Gates to tell us what to do, as Dr. Fauci has been diminished. We wait for Tim Cook to get us masks, Elon Musk to supply ventilators, and Jeff Bezos to vaccinate us, because FEMA and the CDC aren’t doing it. But predicating society on the unaccountable goodwill of billionaires is not a recipe for long-term prosperity. It’s asking Pablo Escobar to fund the police.

DEMOCRACY’S ONE WEIRD TRICK

How do we strengthen what we do control, our government?

What we’ve learned, through the Trump administration and especially during the pandemic, is that in a weak government, elected officials have more power than we realized, and institutions have less. Ironically, our national disregard for politicians has empowered them, because we’ve allowed them to hollow out the institutions meant to provide a long-term counterbalance. We’ve allowed them keep us in check.

People aren’t very good at planning years ahead, en masse. We want tax cuts, right now, over a cleaner environment for our children, decades from now. We surrender to our instincts for immediate gratification.42

Pure democracy is populism (dêmos is Ancient Greek for “ordinary citizens”). The innovation is institutions that slow democracy down and filter it through legislature, courts, and agencies. The media, too, is meant to have a countervailing effect—people with domain expertise who can say, “Let’s interrogate the issue before banning immigrants from certain countries, removing grizzlies off endangered species lists, adding a citizenship question to the census, or restricting access to birth control because people in power at that moment decide it’s a good idea.”

VOTE

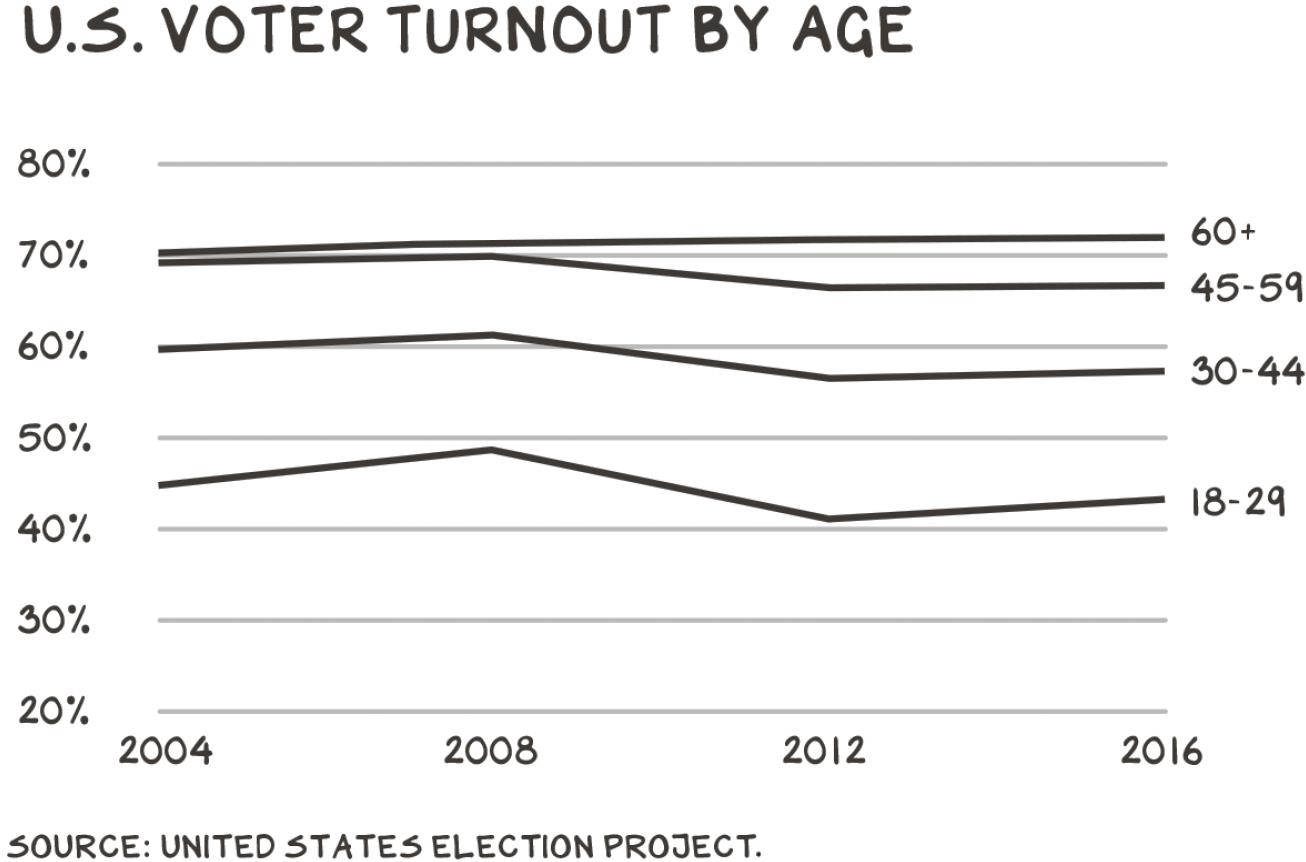

The most important thing we can do is also the easiest. Vote. Vote in off-year elections. Vote in local elections. Because elected officials are defining government right now, and they respond to the demographics of the voting population. It matters much less who you vote for, than that you vote at all. The point is to signal that you are worth a politician’s time. You want to know why we have a system that’s designed to transfer wealth from the young to the old? Because old people vote. Those over 65 are twice as likely to vote as people under 30. And the demo in democracy works … too well. Politicians are even more likely to cater to even the old people who didn’t vote for them. Because those are votes they can get. You know who politicians don’t care about? Everyone who doesn’t vote (or donate large amounts of money).

I think we should elect officials who believe in government, understand the threat of concentrated private power, and respect science. A broader electorate will mean that elected officials respond to the needs of a broader community.

Tragedy of the Commons

Government is charged with preventing tragedies of the commons, so to speak. As I write this in August 2020, the immediate responsibility of government is to steer us through and out of the pandemic. I doubt that mission will have changed by the time this book goes to press. The history of missteps and chances lost in this pandemic is depressingly long, but the blame game is for historians, not serious leaders. We are facing an economic catastrophe, and we’ve already wasted the better part of $3 trillion not fixing it.

We need to protect people, not companies. My choice would have been to follow the German model. Under their “Kurzarbeit” program, employers can furlough workers during the pandemic, while the government takes responsibility for two thirds of the worker’s salary. Workers stay technically employed, so they can easily return to their job once there is work to be done, but are under no pressure to work while it is unsafe. In effect, the government says, You don’t need to worry about food. You are in a position where you can distance safely without putting your family at risk. You don’t have to make bad decisions to feed your family. And there’s no fear.43 Happiness is not only a function of what you have, but what you don’t have. Specifically, an absence of fear. Absence from the fear that you won’t be able to feed your family or that serious illness might mean bankruptcy.

Other European countries have similar programs. In Spain, one worker told The New York Times that thanks to her country’s aid, “I was able to feel relaxed at home.” In Ireland, an event planner told the paper that since the government was paying his employees while they couldn’t work, “It oddly hasn’t been a stressful time.” One of his employees was even able to complete the purchase of a house, remaining eligible for a mortgage because she was still technically employed.44

If that sounds expensive, consider America is still convulsed by the pandemic, while life has largely returned to normal in most of Europe and Asia. Or so we’ve heard. We can’t see for ourselves, because EU countries will not let Americans in.

When you give money to poor and working-class people, you see an immediate multiplier effect in the economy—because they spend it. They buy food, they pay rent, they buy new shoes and fix their broken refrigerator. And consumers are the best arbiters of which companies should survive the crisis, not the government. If you believe in the power of markets, we should be putting money into the hands of consumers, not companies. The $1,200 checks the government sent out at the onset of the pandemic were a baby step in the right direction, but we are way past baby steps.

And I want to be clear: I’m not talking about unemployment insurance, though there is a role for that. We should take care of people who can’t work, and aid during periods of unexpected job loss is an essential part of the safety net. But conditioning assistance on unemployment is needlessly disruptive on both employers and employees. For most people, it means losing health insurance. It requires complex administration, which as we have seen, breaks down in the face of high demand. The goal is to create jobs that endure in a post-pandemic economy.

The bulk of our economic response to the pandemic should have come in the form of protecting the people it puts at risk. Where it makes sense, by all means take action that ensures they will have jobs when it ends. But start with the people and work up. Don’t start with shareholders and work down. Shareholders are supposed to lose, that’s how capitalism works. The priorities are these: Protect people, not jobs. Protect jobs, not corporations. Protect corporations, not shareholders. End of list.

CALLING THE CORONA CORPS

And we need to take the fight to the virus. Lockdowns are the nuclear option—social distancing and masking are necessary protections against an enemy on the march. Epidemics either burn themselves out (and this one would likely kill millions if we let it do that) or are defeated through aggressive containment measures. South Korea has even published a playbook.45 The proven formula for flattening the curve without putting the economy back in an induced coma is simple: testing, tracing, and isolation. That is, we need widespread testing followed by the swift identification and temporary isolation of everyone who has come in contact with infected people. In a country as large as ours, with the virus as widespread as it is, it would take an army to do that now. Estimates range, but we need something close to 180,000 contact tracers. Fortunately, we have an army waiting in the wings.

Recent high school graduates face an unpalatable choice: the worst job market in modern history, or a $50,000 streaming video platform called College in the Time of Corona. We should put them to work in a Corona Corps, an organization in the long tradition of youth service, from Mormon missionaries to Teach for America to the Peace Corps, but one focused on the crisis at hand. A volunteer army of 18- to 24-year-olds, trained and equipped to fight the virus—and reshape the trajectory of their own lives.

The Corps’ main job would be contact tracing: interviewing infected people, evaluating the nature of their contacts and reaching out to those put at risk. The Corps would also staff testing centers across the country and work with people who are required to isolate, providing anything from food delivery to emotional support. The government-funded Corona Corps would pay their costs and a modest wage, say $2,500 a month. Those who serve at least six months would receive a credit toward educational costs or student debt.

Beyond the benefits that would accrue to those who serve, and the role they would play in defeating the virus, I believe the country would reap a larger dividend. A service program like this could help bridge partisan divides. Consider that between 1965 and 1975, more than two thirds of the members of Congress had served their country in uniform. The important legislative achievements of those years were shaped by leaders who shared that bond, larger than politics or party. Today, fewer than 20 percent have that bond. The Corps, and future national service programs, could reanimate our superpower, cooperation.

Service in the Corps would not be without risk. But we send young people to the front lines of wars not because they are immune from bullets, but because someone must go. And young adults appear to face much lower risk of serious side effects or death from Covid-19 than older people. Corps members would be regularly tested, and if they were infected, they have an overwhelming likelihood not just of recovering, but of developing antibodies.

A Corona Corps would not be cheap: 180,000 members at, I estimate, $60,000 each for compensation, training, and support would cost nearly $11 billion. The government could no doubt find a way to make it cost twice that. Yet that’s a rounding error on the sums allocated for stimulus and unemployment to date. Consider it a warranty against needing another multitrillion-dollar rescue package.

Moreover, the Corona Corps could be the nucleus of a permanent national service organization. An opportunity to mature a generation of Americans who might sit or stand shoulder to shoulder and see each other, first and foremost, as Americans instead of Democrats or Republicans. We need our young people grounded, again, in America.

MALEFACTORS OF GREAT WEALTH

Addressing the current crisis is just the beginning of government responsibilities, of course. Looking ahead, there are two priorities that should inform our policies: restraining private power, especially that held by big tech, and empowering individuals.

The first step to restraining private power is to get it out of government. Ideally we would substantially reduce the amount of money that flows from private wealth into political campaigns, though the Supreme Court has made that difficult. The least we can do, however, is enforce the bright-line rules against outright corruption. We’ve got to take conflict-of-interest rules seriously. When elected to national office, your assets should go in a blind trust. Permitting politicians to trade stock on information they obtain undermines faith in our institutions. A study of stock trades by senators in the 1990s found they beat the market by about 12% per year—twice the advantage enjoyed by corporate insiders.46 In May 2020, Senator Richard Burr had access to confidential information about the seriousness of the coronavirus, and then appears to have used that to time his stock trades. Future senators shouldn’t be tempted to engage in this type of corruption. Likewise, it’s lunacy that we don’t require presidential candidates to release their tax returns, or enforce the constitutional prohibition on presidents profiting from their office.

Beyond cleaning its own house, Congress and the Executive must reinvigorate our antitrust and regulatory limits, particularly on big tech. I’ve touched on this in chapter 2, so here I only want to emphasize the power of these remedies. Regulation can be freeing. I don’t think the managers at the GM plant want to pour mercury in the river. But why disarm unilaterally? Business is hard enough without making it a daily morality test. Environmental laws make it easier to do the right thing.

Likewise, we think of antitrust (breaking companies up) as a punishment. It isn’t, it’s oxygenation. When we broke up AT&T we birthed seven firms that in aggregate were worth more than the original. According to one analysis, an investment in AT&T on the eve of the breakup in 1983 returned an annual growth rate of 18.5% through 1995, while the broader market grew at around 10% over the same period. One of the divested companies, Southwestern Bell, was so successful that it bought AT&T itself in 2005. As for the rest of us not fortunate enough to have AT&T stock in 1983, compare the innovation during the twenty years pre breakup (touch-tone dialing and call waiting) to post breakup (cell phones, the consumer internet, and the then-longest bull market in history).

If you set aside the notion of antitrust enforcement as a moral judgment and consider the advantages, many of the problems posed by big tech—not all of them—would be addressed if these companies were broken up. If we split Google and YouTube into separate companies, we wouldn’t create competition directly. But at the first board meeting of the newly spun YouTube, new leadership would decide to get into text-based search. Across town at the first board meeting of the new Google, the firm likely decides to get into video-based search.

Competition creates options. As a monopoly, why would YouTube improve its kids’ content when there is no competing video platform with more effective guardrails? Someone at one of these board meetings will realize Procter & Gamble is more likely to advertise on their video platform if they commit to protecting young viewers. And that Unilever is more inclined to patronize a search engine that ensures when someone types in “overthrow the government,” the first result is a voter registration form and not instructions on how to build a dirty bomb.

Currently, there’s no incentive to do anything but create algorithms that inspire more clicks and more addiction, not giving a damn about the commonwealth. So, we break them up—not because they’re evil, not because they don’t pay their taxes, not because they destroy jobs—but because we’re capitalists, and we believe in competition and innovation. It’s not punishment, it’s overdue oxygenation of the marketplace that will unleash billions, maybe trillions, in shareholder value.

What We Must Do

I opened this book with some statistics about wars: World War II, a war of sacrifice, and the war against Covid, a battle of selfish behavior vs. a pathogen. And it appears we are losing this battle, and maybe the larger war. This microscopic foe has exploited flaws in our society. It kills a thousand of us each day—many times the death rate of past wars. We have mobilized, in a sense, but not well.

Once, we fought on multiple fronts—home and abroad, technological, industrial, and agricultural, political and personal. In WWII almost a third of vegetables were harvested from “victory gardens” planted in people’s yards. Eleanor Roosevelt planted one on the White House lawn.

Despite the formidable financial stress of wartime, households were asked to dig deeper and buy war bonds. The entire auto industry was retooled to build bombers and tanks—not a single new car was built for almost three years.47 Chrysler built a factory in the Detroit suburbs that manufactured more tanks than the entire Third Reich.48 And a generation of young men heeded the call to arms, 450,000 dying on the beaches of Normandy and the jungles of Luzon. Sure, we had plans for a silver bullet: 120,000 people worked on the Manhattan Project to find a vaccine for tyranny. But we didn’t stop planting victory gardens, building tanks, and sacrificing while we waited for Einstein and Oppenheimer to save us.

Not all of this was popular, and none of it was easy. Angry and desperate people counterfeited ration cards, evaded travel restrictions, and over 5,000 Americans were imprisoned for evading the draft.49 The government invested millions in enforcement—but also encouragement. From the White House to Hollywood, public figures called on patriotism and crafted a shared purpose to inspire widespread sacrifice.

Our patriotic sacrifices in WWII were not inevitable. We were called to them by leaders who knew what was required of us, and laid it out for us in honest terms. At every level, and in every field, voices were raised in support of the commonwealth, rather than in defense of personal property and a perverted sense of freedom.

Where is that shared purpose today? We are fighting an enemy three times as lethal to our population as the Axis powers, yet Americans don’t want to wear masks and expect the government to send them more money. Resistance to sacrifice and dismissal of community is framed as “liberty.”

Liberty is a founding American value, but it is not an individual guarantee, nor one divorced from the greater good. This is the central thesis of the Declaration of Independence: not merely that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are inalienable rights, but that “to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men.” The Founders, as imperfect as they were, saw clearly what we have forgotten. As Benjamin Franklin said when he signed the revolutionary document, “We must all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall hang separately.”

We didn’t need to be here, and we are not doomed to continue down this path. Indeed, the good news is that defeating the pandemic and moving from crisis to opportunity requires that we reawaken our national character. The opportunity presented by such a reawakening is immense.

A step backward, after making a wrong turn, is a step in the right direction.

—KURT VONNEGUT

Pandemics, wars, depressions—these shocks are painful, but the times that follow are often among the most productive in human history. The generations that endure and observe the pain are best prepared for the fight.

How will the rising generation shoulder the burdens of the post-corona world? There is reason to hope.

Might we be maturing a generation that will embrace our species’ superpower: cooperation? If the British, Russians, and Americans could partner to fight a common enemy 80 years ago, can’t we partner to eradicate an enemy that threatens all 7.7 billion of us?

Might this generation decide that if half our nation’s population cannot go 60 days without government assistance, then we must make more forward-leaning investments to save trillions in future emergency stimulus?

Might this generation inspire greater comity of man, more empathy for the disenfranchised, and a greater appreciation for what it means to be American? And finally, might we decide to reinvest in the greatest source of good in history—the U.S. government? Might we?

America’s history is not short on crises or missed opportunities. Its sins and failures are as historic as its virtues and successes. At its best, America exemplifies generosity, grit, innovation, and a willingness to sacrifice for one another and for future generations. When we lose sight of these, we wander into exploitation and crisis.

All of our history, as well as our future, is ours. Our commonwealth didn’t just happen, it was shaped. We chose this path—no trend is permanent and can’t be made worse or corrected.

America isn’t “what it is,” but what we make of it.