11

The Circus

California and the house on Cove Way now held little attraction, and Chaplin remained more than two months in New York after the première of The Gold Rush. The principal attraction which kept him there was an eighteen-year-old dancer in the 1925 edition of Ziegfeld Follies at the New Amsterdam Theatre, Louise Brooks. Her own film career was still to be fulfilled, but her sharp intelligence and astonishing looks – the sculpted, classical features and distinctive helmet bob – had already made their mark. She seems to have been introduced to Chaplin soon after the Gold Rush première by Walter Wanger, who was one of her current lovers. Soon she had moved into Chaplin’s suite at the Ambassador Hotel, where they appear to have shared their time and fun with another couple, Louise’s Follies friend Peggy Fears and the cinema mogul A. C. Blumenthal, who had a penthouse at the Ambassador. Louise later remembered how Chaplin would amuse them by acting out scenes from films and doing imitations of Isadora Duncan, John Barrymore and Louise herself:

A Follies girl swished across the room; and I began to cry while Charlie denied absolutely that he was imitating me. Nevertheless, as he patted my hand, I determined to abandon that silly walk forthwith.1

Their affair lasted two months.

The day after he left town I got a nice check in the mail signed ‘Charlie’. And then I didn’t even write him a thank-you note. Damn me.2

Chaplin eventually returned to California on 15 October 1925, and was very soon at work on his next project, The Circus. It was to be a production dogged by persistent misfortune. The most surprising aspect of the film is not that it is as good as it is, but that it was ever completed at all.

After The Gold Rush, Chaplin had considered a version of Stevenson’s The Suicide Club. He was always toying with an idea for a Napoleon film. In March, Sydney had cabled him from New York:

SHERWOOD OF LIFE WRITTEN MOVIE STORY CALLED SKY-SCRAPER FOR BUSTER KEATON STOP KEATON CONSIDERS STORY GOOD BUT HAS NOT AS YET DEFINITELY PURCHASED IT STOP HAVE READ IT AND THINK IT OKAY SHERWOOD WRITING ANOTHER ONE SUITABLE FOR YOU STOP WIRE ME IF YOU WANT ME TO TRY AND CLOSE THE DEAL FOR YOU.

Sherwood was one of Chaplin’s most appreciative critics, but Chaplin seems not to have responded to the proposition. Henry Bergman, a modest man who recorded few impressions of his many years with Chaplin, described the genesis of the new film:

Before he had made The Circus he said to me one night, ‘Henry, I have an idea I would like to do: a gag placing me in a position I can’t get away from for some reason. I’m on a high place troubled by something else, monkeys or things that come to me and I can’t get away from them.’ He was mulling around in his head a vaudeville story. I said to him, ‘Charlie, you can’t do anything like that on a stage. The audience would be uncomfortable craning their necks to watch a vaudeville actor. It would be unnatural. Why not develop your idea in a circus tent on a tightrope. I’ll teach you to walk a rope.’3

Clearly there were other arguments against setting a film in a vaudeville theatre so soon after E. A. Dupont’s German production Variety (1925), which was currently the talk of the film world.

‘Many of his ideas are built on one gag,’ Bergman added. Nightmare has often been the essence of comedy. Harold Lloyd’s most famous film, Safety Last, is centred on his perils high on the side of a skyscraper. James Agee described a sequence in a Laurel and Hardy film as ‘simple and real … as a nightmare. Laurel and Hardy are trying to move a piano across a narrow suspension bridge. The bridge is slung over a sickening chasm, between a couple of Alps. Midway they meet a gorilla.’4

The nightmare that Chaplin invented – to what extent might it have been an unconscious metaphor for his troubles? – was to place himself on a tightrope, high above the ring of a circus. He has no net. His safety harness comes loose. He is attacked by monkeys. They rip off his trousers. He has forgotten to put on his tights.

The story which eventually grew around this climactic incident of farcical horror is a neat comic-romantic melodrama. Charlie the Tramp chances upon a travelling circus which is doing bad business. He is chased into the ring by police, and his accidents there prove a tremendous hit with the audience. He is consequently taken on as a clown: the problem is that he is funny only when he does not intend to be. He falls in love with the daughter of the proprietor, and defends her from her father’s cruelties. The idyll ends when a new star, Rex the High Wire Walker, arrives in the show and steals the girl’s heart. It is in consequence of his efforts to emulate his rival that he finds himself in the disastrous predicament on the tightrope. He finally faces defeat, helps the couple to elope, and at the end is left alone in the ring of trodden grass which is all that remains of the circus.

Chaplin had a new assistant, who was also eventually to be chosen to play the part of Rex. Harry Crocker was a new favourite in the San Simeon set, and it was through Hearst and Marion Davies that Chaplin first met him. Crocker at this time was thirty years old, slightly over six feet tall and conventionally handsome. He came from a prominent San Francisco banking family, had been through Yale and had started his working life in the brokerage business. Yearning for something more glamorous, he had thrown up brokerage in the autumn of 1924 to come to Hollywood, where his good looks and taste for practical jokes attracted Marion Davies. Having acted with the Los Angeles Playhouse Company and done a bit part as a soldier in The Big Parade, he was given a leading role by Marion in her film, Tillie the Toiler. After that he had landed three other film roles, and when Chaplin suggested he might work with him had just begun work as an extra in King Vidor’s La Bohème. Chaplin told Crocker to make the necessary arrangements with Alf Reeves; but when Crocker reported to Reeves’s office, the latter knew nothing about it. ‘Don’t let that bother you,’ he said. ‘He is very vague.’5 When Eddie Sutherland heard that Crocker had joined Chaplin in his own former capacity as assistant director, he advised him:

If you’re smart you enter Chaplin on your books as a son-of-a-bitch. He isn’t always one, but he can be one on occasion. I thought it better to start off with that appellation of him in mind, then when he behaves badly it doesn’t come as quite the shock it might otherwise be, and all his good behaviour comes as quite a pleasant surprise.6

Another former Chaplin assistant, Henri d’Abbadie d’Arrast, also warned him, ‘Charlie has a sadistic streak in him. Even if he’s very fond of you he’ll try and lick you mentally, to cow you, to get your goat. He can’t help it. You’ll be surprised how many friends he’s alienated through that one trait.’ Crocker’s experiences of Chaplin were happier, however, and their association lasted through the years, even though on occasion their fights could be bitter, and a disagreement led to his departure from City Lights. On The Circus he found he had been engaged as assistant, writer-actor and companion. His first job was to work with Chaplin on story ideas, which essentially meant acting as sounding board and stenographer. Chaplin and Crocker took off for ten days (9–18 November 1925) to Del Monte to work on the story, leaving the studio staff, under the supervision of Danny Hall, the production designer, to start building a circus tent and menagerie on the studio lot. The trip provided a further escape from the household at Cove Way. It was also necessary to get away from the now regular distractions of evenings in the company of Hearst and Marion Davies.

Chaplin’s chauffeur, Frank Kawa, drove them in the black Locomobile, with Kono following in his own car. Crocker later recalled his bewilderment at the variety of Chaplin’s conversation on the leisurely journey. He outlined a scheme for taxing industry by a kind of 25 per cent tithe on its products; he talked of his horror at working conditions in factories, and at the pressure to succeed exerted upon employees by American business; about customs of breakfast-time gastronomy; about time and space and light.

A lot of their thinking was done in the course of long walks around Del Monte. Crocker recalled how one day, oblivious of the surrounding traffic, Chaplin suddenly acted out a set-piece he had just thought up. The barker in front of a sideshow would point at the banners advertising a giant and a midget. Charlie would pause on his way out of the door of the tent, reach up to shake hands with the unseen giant, then turn to the other side and stoop to say goodbye to the midget.

When these creative sessions had gone well, Chaplin would sing music hall songs on the way back to Pearl Lodge, where they stayed, or launch into discussions of international finance or the transmigration of souls. Then he might suddenly propose games of betting on the length of each straight stretch of road to the next curve. One night in the Lodge, Crocker recalled, they competed to make bad puns, after which Chaplin performed all the parts in a performance of the third and fourth acts of Sherlock Holmes.

The notes which they brought back from their scenario trip still exist and illustrate vividly Chaplin’s method of starting the construction of a film by assembling a disparate stack of potential gags, scenes or hazy notions. He collected together a mass of fabrics; only later did he settle upon the pattern of the material and cut of the garment. At this time Chaplin was still undecided as to whether to call the film The Circus or The Traveller. The notes are presented as a series of ‘suggestions’; some are for whole sequences:

Suggestion: Charlie notices the dog trainer is ill-treating animals – one dog especially. He takes trainer to task and fight ensues. As the 2 men are struggling, the dog that Charlie has tried to save comes into the fight and bites Charlie. Charlie finally flees. He is angered at dog, but dog sits up and begs. Charlie forgives him and goes to pat him and dog almost bites his hand off.

This is a parable of ingratitude worthy of Luis Buñuel. Chaplin had a characteristic afterthought:

Suggestion: At end of episode with cruel trainer, have Charlie present him with whip to replace one he has broken.

This sequence, like innumerable others, was to be rejected. Other ‘suggestions’ remained intact in the eventual scenario:

Suggestion: Charlie mistaken for pickpocket. Cop chases him through funhouse. Charlie takes place on outside of fun house beside dummies, imitating their wooden action. Maybe introduce crook – also in fight with police – hiding as dummy when Charlie socks him as part of act – crook being forced to take it as cop is watching.

Some ‘suggestions’ are for individual gags:

Suggestion: Charlie is standing near camel. Tactlessly he asks fellow workman for a ‘Lucky Strike’ and the incensed camel bites him. [‘Lucky Strike’ and ‘Camel’ were rival brands of cigarette.]

Suggestion: Charlie at work with hose, accidentally hits boss, blames it on elephant and spanks elephant’s trunk. Tells elephant ‘Put that away.’

Often in this kind of preliminary work on a film we find Chaplin reverting to ideas which seem almost an obsession with him, but then – perhaps recognizing a too persistent preoccupation – rejecting them. The lurking fear of the audience – particularly an audience in a live theatre – which was to be most completely expressed in Limelight is ever present:

Suggestion: During the efforts of Charlie to be funny as clown, there is a tough guy in the audience who fails to appreciate his efforts, making it exceedingly difficult for Charlie to work.

One gag idea echoes, whether consciously or not, Chaplin’s current efforts to keep his domestic worries from a suspicious and prying press:

Suggestion: An acrobat fights violently with wife or partner off-stage and is very suave and loving on.

Chaplin’s first idea for the beginning was never used: his eventual solution was certainly much neater. It nevertheless showed his reluctance to waste a good idea, for here once more was material from the abandoned film, The Professor:

Suggestion for opening: Under the archway of a bridge is a jungle of hoboes. Some asleep – some sitting around – one stirring food in a can over the fire. Charlie comes into camp. He looks around fastidiously – takes out a handkerchief – dusts off a rock and sits down. One bum looks up and inquires: ‘What’s your line?’ Charlie answers: ‘I am a circus man.’ Bum looks at him incredulously. He notices look and takes from under his arm a small box labelled ‘Flea Circus’. Business ad lib with fleas.

In putting fleas away for night, Charlie discovers one gone – goes over to bum with long beard – picks up flea from beard, regards it and puts it back. It is evidently not one of the circus.

All asleep. In movements in sleep, flea circus is overturned and fleas escape. Scratching commences among bums but fleas concentrate on dog. Dog finally gets up in agony and whines, waking Charlie. He notices overturned flea circus – watches dog and jumps at the right conclusion. Pursuit of dog which goes into the lake, drowning circus. Charlie in despair.

The surviving sequence of The Professor also ends with the Professor giving chase to the dog. The tragic finale indicated in this ‘suggestion’ perhaps tells us how the sequence might have ended in the earlier film. The idea for the opening of The Circus continues with a wonderful gag which was unfortunately never used – by Chaplin or any other comedian:

Next morning bums prepare to board train. They will ride brakebeams. Charlie spies mail-sack in brackets – removes same and stands in brackets – is caught in arm of mail-car. Mail clerk is asleep. Charlie rides at ease, enjoying view, while bums gaze enviously from underneath car. Passenger in car in front of Charlie throws cigarette out of window. Charlie catches same and smokes it – dropping butt with gesture to one of the bums underneath car. Arrives in town to discover circus in progress.

Although much would be changed in the course of the lengthy production of The Circus there was plenty for the unit to work on when Chaplin and Crocker returned from Del Monte on 18 November.

Henry Bergman fulfilled his promise to teach Chaplin to walk the tightrope, though it is not clear at what point in his career this man of so many parts had learned a skill not evidently suited to a person of his large girth. ‘I taught Charlie to walk a rope in one week … We stretched the rope this high from the floor [he indicated a foot high to the interviewer] then raised it as high as the ceiling with a net under it, but Charlie never fell. He walked it all day long. You didn’t see anything in the picture of what he did on that rope.’ Crocker, for the role of Rex, also had to learn to walk the rope convincingly, and day after day, right up to Christmas, he and Chaplin practised for hours while below and around them the sets were decorated and the costumes prepared. They were only briefly interrupted by the first of the catastrophes which hit the production. The tent was almost ready when, on Sunday, 6 December, an exceptionally rough storm of wind and rain badly damaged it.

The use of the name ‘Georgia’ for the heroine in the story suggestions shows that Georgia Hale was expected to be Chaplin’s leading lady once more. Yet her contract came to an end on 31 December, and it is not certain why it was not renewed. Her work in The Gold Rush had been good and Chaplin seemed to have become genuinely fond of her; their friendship continued intermittently for years after the film. Perhaps Georgia was impatient for a faster-moving career. As it was, she had appeared in five films after completing The Gold Rush and before The Circus eventually emerged. She made half a dozen more films by 1928 and then retired from the screen: her voice and diction were not as pleasing as her looks and her career was doomed by the onset of talking pictures. Her most memorable performances were those in The Salvation Hunters, The Gold Rush and The Last Moment, directed by the gifted Paul Fejös – apparently confirming Josef von Sternberg’s view that Georgia Hale was an actress whose onscreen qualities depended to a great extent upon the gifts of her directors.

Chaplin’s new leading lady was Merna Kennedy, the childhood friend of Lita Grey who had accompanied her to the studio on the day she secured her test for The Gold Rush. The studio publicity for the release of the film related how Merna got the part:

… Charlie was about to make The Circus. He was to walk a tightrope and frolic about in the sideshows and seek to win the fluff-skirted girl who rides the circling white Arabian in the middle ring. Who was to be the girl?

‘Merna Kennedy is playing in a musical show at the Mason Opera House here in Los Angeles.’

‘Let’s look at her tonight,’ was the answer.

So Charlie Chaplin went to the Mason and saw the musical show All For You.

Merna Kennedy was picked. Screen tests followed, of course, and the vivaciousness and charm of the red-haired lady with the green eyes registered with Charlie. He chose a leading lady whom none knew, whom none had seen on the screen.7

Merna Kennedy had in fact been suggested for the role by Lita, who had met her again after more than a year while Chaplin was in New York. Chaplin appears initially to have been less enthusiastic about the suggestion than the press story suggests, but he was persuaded. Lita came to regret her initiative: she had already been jealous of Georgia Hale: subsequently she realized that her husband had in turn developed a romantic interest in his new leading lady, Merna. She tumbled to the fact that Chaplin was having an affair with Merna when she discovered that he had given her a diamond bracelet and suggested she might play Josephine to his Napoleon – a compliment he had paid Lita herself in their euphoric early days.

Merna Kennedy’s contract was drawn up to commence on 2 January 1926. There was little other casting to be done. Chaplin wanted Henry Bergman to be Merna’s stepfather, the mean circus proprietor, ‘but I said, “No, Charlie, I’m a roly-poly kind-faced man, not the dirty heavy who would beat a girl.” So I was cast as the fat old clown.’ Instead, Allan Garcia, making his first appearance in a major role, was put under contract to play the part.

Shooting began on Monday, 11 January. The first two weeks were spent on the scenes on the tightrope. This was contrary to Chaplin’s usual method of shooting in story sequence, but he was in training, and in any case this was the one scene of the film which was so far fully worked out in his head. On 17 January – a Sunday, which showed that Chaplin was particularly engrossed in the scene – he began work with the monkeys. On 27 January he steeled himself to shooting material of the audience in the circus tent. He was never happy with crowd scenes, and the cost – even in 1926 – was worrying if crowd shooting went on too long. For the circus audience the studio hired 185 extras at $5 for the day, 114 at $7.50, 77 at $10, and one at $15. Chaplin made eighteen lengthy takes with the crowd that could subsequently be cut up for inserts, ensuring that the crowd shots could be wrapped up in a day. Three days later there was a more costly extra on the lot – an elephant whose day’s hire was $150, with $15 for its trainer.

In the first week of February, no doubt somewhat depressed by a bad cold, Chaplin edited the scenes already shot on the tightrope and decided he wanted to retake them, which took up the rest of the week. The following week, he and Crocker shot the scenes in which they rode the bicycle on the tightrope, with Charlie making his ‘ride for life’. Thereupon catastrophe struck again. The unit discovered that the rushes they had seen so far were marred by scratches. Faults or errors were discovered in the studio laboratory. There is no record of precisely what happened, but it is not hard to guess Chaplin’s reaction. The laboratory staff was changed, but Chaplin had to face the fact that all the work of the past month would have to be redone. Throughout the week of 16 February he was back on the tightrope. By the time he had finished, he had done more than 700 takes on the wire. It is hardly surprising that he was, as Crocker remembered, often exhausted. ‘Nobody has ever noticed that my legs doubled for Charlie’s when he needed a rest.’ The retakes were completed by the end of February, and the first week in March Merna Kennedy was put to work. She apparently worked well under Chaplin’s direction: the daily shooting records indicate few problems or delays with her scenes.

Work on the film was a welcome distraction from the continuing miseries of Cove Way. In the autumn of 1925 Lita discovered that she was again pregnant. Chaplin was furious to find he had created yet another snare for himself (or so he felt) and the pregnancy led to further deterioration of relations between the couple. Lita found it impossible to please her husband and was wretchedly jealous of his attentions to Marion Davies, Merna Kennedy and Georgia Hale. Chaplin, for his part, was tormented by the situation. When their first child was born he had begun to suffer from acute insomnia and would prowl the house at night with a shotgun, fearing intruders, and bathe or shower a dozen times a day. Now he had the studio electricians fix bugging devices in Lita’s room, but there was nothing to hear and the equipment was in any case technically inadequate. Even efforts at conciliation went wrong. Chaplin acceded to Lita’s pleas to meet people of her own age and paid for her to give a party for eight of her young friends in a restaurant. Rashly, Lita took them home to Cove Way afterwards. When Chaplin returned unexpectedly he flew into a rage and threw the guests out of the house. The incident was to be cited by both parties in the subsequent divorce action. In this fraught atmosphere Lita’s second child, Sydney Earl Chaplin, was born five weeks prematurely, on 30 March 1926. Lita’s single consolation was that the birth, unlike that of her first son, was easy. Certainly the new child did nothing to improve the unhappy marriage.

Again the choice of name was a matter of dispute but Lita agreed to name the boy after her brother-in-law. For several years after the break-up of the marriage, Lita called the boy ‘Tommy’. (In her 1998 memoir Lita said that her distaste for the name ‘Sydney’ was partly because Chaplin’s half-brother had made a pass at her shortly after the marriage.) There was disagreement over baptism: Chaplin always believed that children should be allowed to choose their own religion when they reached a sufficiently mature age.

But home life was merely a distraction, as work on The Circus resumed at full tilt. The day after the birth Chaplin was rehearsing the mirror maze, which required some ingenious camera placement by Totheroh. The exteriors of the carnival were shot at Venice Beach, not far from the spot where Kid’s Auto Races had been filmed. The location scenes, which involved up to thirty extras and a bus to take them to the shooting, were shot in the mornings, before the regular crowds arrived. Among the scenes filmed in the studio in the afternoons was that in which the hungry Charlie eats a hot dog clutched by a babe in arms, solicitously wiping the child’s mouth when its father turns around. The incident was perhaps suggested by a favourite yarn of Fred Karno, who related how he and some young friends from the circus stole jam sandwiches from school children when they had no money to buy breakfast.

Throughout the succeeding five months work continued steadily. There was a brief but notable interruption on 16 June when Raquel Meller visited the set. Chaplin had conceived great enthusiasm for the petite and colourful Spanish actress and chanteuse. For a while he felt that he had at last found the ideal Josephine for the Napoleon film that continued to obsess him. On 7 September the studio was closed for the day to mark the funeral of Rudolph Valentino. Chaplin, who was one of the great screen lover’s pall-bearers, said graciously that his death was ‘one of the greatest tragedies that has occurred in the history of the motion picture industry’.

Meanwhile, the work with the lions caused concern. Two animals were hired (at a cost of $150 a day, including the trainer): one was docile, but the other was a spirited creature. In at least one scene that appears in the finished film, as Chaplin would unashamedly point out in later years, the fear on his face was not pretence. Despite the risk, Chaplin went back into the cage day after day. By the time the sequence was completed he had made more than 200 takes with the lions.

One of the inconveniences of working with the lions was that the unit had to fit in with their meal hours, and the lions preferred to eat around three in the afternoon. As a result of the nervous strain and the change of routine, Chaplin was suffering from indigestion, and the doctor prescribed Epsom salts taken in regular small doses in hot water for two or three days. Crocker recalled how he would pace the floor in story conferences, interspersing his oratory with belches, each of which would be followed by a relieved sigh of ‘Ah! That’s better.’ Crocker remembered a typical example: ‘Now, what I want in this story is not only love and romance, but magic. There must be magic. The audience must be enthralled – burp – ah, that’s better!’

Apart from this minor irritation, all seemed to be going well for the moment. Then, on 28 September, a fire suddenly broke out, sweeping through the closed stage. Before it could be brought under control, the set had been completely destroyed; props and equipment were damaged by fire and water; thousands of panes of glass in the roof and walls were broken; the electrical equipment was put out of action. The stills photographer captured a few shots of Chaplin, still in his costume, gazing in dismay at the wreckage. These unposed shots are some of the most poignant images of the Tramp. The resourceful Totheroh filmed 250 feet of the catastrophe and his bemused boss. It was slight compensation that this piece of impromptu film could be exploited as pre-publicity for The Circus.

The studio was rapidly put back into partial operation; and in only ten working days, between 3 and 14 October, Chaplin had completed a lengthy and complicated sequence in the café set. For reasons known only to himself, he was not to use the sequence in the film, though it is a faultlessly constructed and self-contained comic sketch. Charlie, his nose much out of joint, reluctantly accompanies Rex and Merna to the café. At a neighbouring table sit two prize fighters, twin brothers. (Both ‘twins’ are played by the same actor, ‘Doc’ Stone: Totheroh and his fellow cameramen performed the magic with double exposure.) One of the two brothers amuses himself by insulting and annoying Charlie. This gives Charlie an idea for winning back Merna’s admiration. He takes the fighter aside, and pays him $5 to pretend to be beaten in a fight. The ruse works successfully, and Rex and Merna see Charlie with fresh eyes, until the fighter’s twin, who had earlier left the restaurant, returns to take his brother’s place. Charlie, expecting to repeat his earlier performance, attacks him, but is dismayed when the fighter starts hitting back. A series of happy accidents save the day, and Rex knocks out Charlie’s opponent. As the party departs from the restaurant, Charlie leaves Rex and Merna for a moment to retrieve $5 from the pocket of the opponent whom he believes to have reneged on their contract.

In early November Chaplin shot an amusing sequence to lead in to this café episode. It was filmed on Sunset Boulevard, which still retained a pleasantly rural look. Charlie is proudly walking Merna out, despite the tiresome attentions of a stray dog which snaps about his ankles. To his chagrin, they meet Rex, who joins them in their walk. Merna is touched by Rex’s gallantry when he picks up the purse a lady has dropped. Charlie determines to show himself as gallant too, but unhappily the distressed damsel who falls to his lot is a stalwart woman laden with inadequately wrapped parcels of fish. Charlie attempts to pick up a single fish she has dropped but his efforts only result in an endless scaly avalanche, as he struggles desperately to rewrap them. The lady becomes more and more angry and Charlie more and more helpless until he retreats with the embarrassed hint of a shrug.

At the end of November, while Chaplin was rehearsing a new roller-skating routine, Lita walked out of the house on Cove Way, taking their two children with her. Life had been no easier for the unwelcome child bride than for her exasperated husband. She was intellectually cowed when Chaplin entertained guests of the stature of Albert Einstein: ‘Of course I had nothing to contribute. As I look back on those days with Charlie, I realize how much of a dullard I must have been.’8 She was jealous and fearful of the more sophisticated, beautiful and intelligent women who, she felt, exerted a much more powerful attraction than she herself could ever do. Chaplin made no effort to conceal his infidelities from her. She must have understood, however, that the single rival with which she could never compete was Chaplin’s work.

Chaplin also knew that this was where he was most vulnerable. He remembered the adventures involved in spiriting The Kid to safety, a mere five years ago. As soon as Lita’s lawyers began to gather (her lawyer uncle, Edwin MacMurray, moved from San Francisco to an office in Los Angeles so that he could be near his niece), Chaplin took action to protect The Circus in the event of trouble. On 3 December stock was taken of the film already shot; nine reels of cut positive and thirteen reels of essential uncut scenes were carefully packed into two boxes ready for removal to safety. On Sunday, 5 December notice was posted that studio operations were temporarily suspended. The studio staff was cut down to the minimum. All the actors were laid off, with the exception of Merna Kennedy, Henry Bergman, Harry Crocker and Allan Garcia. As if all this were not enough, the US Government chose this moment to decide that Chaplin’s income tax for the preceding years was underpaid by $1,113,000.

It was at about this time that Robert Florey, a French idolater of Chaplin who was later to become a director in his own right and was to be Chaplin’s assistant on Monsieur Verdoux, wrote a haunting pen portrait of his hero:

Often in the evening, around eleven, when I go to Henry’s, the actors’ restaurant in Hollywood run by the excellent Henry Bergman (whom you have seen in all Chaplin’s films), I meet, walking alone or sometimes with his devoted assistant Harry Crocker, the popular Charlie, the great Charles Spencer Chaplin, unrecognizable beneath his big, shapeless felt hat. To protect himself against the evening mists – the night can be perilous in California – he wraps himself in a big grey overcoat, and his trousers, quite wide, according to the current fashion, hide his tiny feet, shod in buttoned boots with beige cloth tops. So it was that one night last December, coming out of Grauman’s Egyptian, I was striding the short distance between the theatre and our favourite restaurant when I recognized, a few steps ahead of me, the familiar outline of Charlie. Instinctively I slowed my pace, and I cannot express what melancholy overwhelmed me in recognizing the total solitude of the most popular man in the world. He was walking slowly, close to the darkened shop windows; the fog was thick, and Charlie, his hands in the pockets of his raglan, was making a slight, regular movement of his elbows. His footsteps made no sound; his collar was turned up, and he was so slight in his big coat that he might have been taken for a child dressed up in his father’s clothes. This man whose cinematic masterpieces had been shown that very night on screens all across the world, this man who had made people laugh that night in all the continents, was there, walking in front of me in the fog. There was infinite sadness in the spectacle of Charlie, alone in the night. A man whom the smartest salons in the world would have fought to entertain, was quietly walking, alone in the shadows, his hands in his pockets and the brim of his hat pulled down over his eyes. It is true that the life of artists in Hollywood, especially in the evening, when the day’s work is finished, cannot be compared to existence in Paris or London, but to see Charlie Chaplin, alone on the boulevard, like some little extra without a job or a place to live, wrung my heart.

At the corner of Cherokee Street an important event occurred – important for Charlie at least … he met a dog. A fat, common, mongrel who was sitting waiting for who knew what. And Charlie stopped, abruptly. He had found someone to talk to. And he started to question the dog, who probably recognized in him a comrade, because it offered him its paw. I couldn’t hear Charlie’s words, but as I caught up with him he said to me: ‘Are you going to Henry’s? Let’s go together.’ Two minutes later we arrived at the café-restaurant. But instead of entering the front door on Hollywood Boulevard, he went through the kitchen, because Charlie had a guest with him – the fat dog, who had followed him. Charlie ordered a copious dinner for his friend from the Filipino cook, and the dog once more offered his paw to be shaken. We left the kitchen, and as we were going into the restaurant Charlie said, ‘That dog knows me. He often waits on the corner of Cherokee, and I realized tonight that he hadn’t eaten again … so you see I couldn’t do anything else but invite him!’ And that sweet, large-hearted little man talked of other things.9

On 10 January 1927, a day after Chaplin had left for New York, Lita’s lawyers filed the divorce complaint. It was an exceptional document of its kind. In the first place Chaplin was joined as defendant with his studio, his company, Kono, Reeves, the National Bank of Los Angeles, the Bank of Italy, and various other banks and corporations. Again, it was unprecedented among divorce complaints for its length. Normally such complaints run to three or four pages: this one had forty-two. For the most part it was the awful tittle-tattle of who said and did what, a wretched reprise of the abuses and recriminations of a marriage fast repented. Then there was an innuendo of infidelity with ‘a certain prominent film actress’. The lawyers’ biggest gun, though, was their demonstration that things which are done in the dark privacy of the bedroom take on a lurid and shocking aspect in the light of print and the spotlight of the courtroom. They had, moreover, discovered an obscure corner of the Californian Statute Book – a certain section 288a – which whimsically forbade oral sex. The style of the complaint made clear its dual purpose. The joining of Chaplin’s business associates and interests indicated the lawyers’ intention of securing as large a proportion of his material goods as possible. The grubbing detail of the rest was intended, quite simply, to destroy his reputation in the eyes of the public. The Roscoe Arbuckle and William Desmond Taylor scandals were still recent in the public memory.10 Arbuckle had been acquitted of the manslaughter of Virginia Rappe, but the associations of the trials were enough to ruin him and end his career. The lawyers must have been confident that so much innuendo would ensure Chaplin’s fall.

The document was demeaning and humiliating to everyone concerned. The pain it must have caused to a man who so prized his privacy and public dignity can hardly be imagined. Chaplin was reported to be in a state of nervous breakdown in New York, where he was with his lawyer, Nathan Burkan. Meanwhile pirated copies of the divorce complaint became bestsellers in the shadier areas of the book trade: the paperback was entitled The Complaint of Lita. The reporters were insatiable and the Chaplin case became the top newspaper story of the day.

Chaplin’s foresight in removing The Circus to safety was swiftly vindicated. Lita’s lawyers asked for, and were granted, the exceptional remedy of a temporary restraining order to secure not only the community property but also his personal assets, pending litigation. On 12 January the receivers put the studio under guard: in charge of the operation were an attorney, W. I. Gilbert, and a real-estate agent, Herman Spitzel. Alfred Reeves had conveniently taken leave of absence, taking the keys with him, but on 18 January, for no very evident purpose, the receivers opened up the safe and vault. Chaplin talked vaguely of continuing work on The Circus in New York but even he must have had fears that it would never be completed.

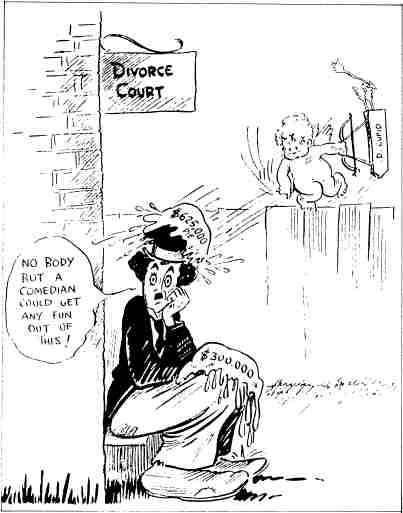

1927 – A cartoonist’s view of the Chaplin–Grey divorce.

Almost more degrading than the complaint was the wrangling over money that now began. The court awarded Lita temporary occupation of the house and provisional alimony of $3000 a month. The house brought her little joy: the servants had left it; the cost of upkeep was enormous; and since the Federal Tax Authorities had placed a lien on Chaplin’s financial assets, the temporary alimony payments were not forthcoming.

Chaplin’s Californian lawyers, with a very poor sense of public relations, proposed a permanent settlement of $25 a week for Lita and the children. Uncle Edwin made nationwide propaganda with this: one women’s club started a milk fund for the Chaplin babies before the Chaplin lawyers agreed to the adjudicated temporary alimony.

Suddenly [Robert Florey recorded] Charlie disappeared … Overnight, Charlie’s house is empty.

The other day, when I was working with Douglas in his Beverly Hills drawing room, I was surprised to see the interpreter of Zorro stop abruptly in front of the window and gaze at something which, from where I sat, I could not see. I didn’t interrupt his meditation, thinking that he was working out some idea for his new film … but after a few moments of silence, Doug exclaimed:

‘Look at the house with the blind windows!’

And, in my turn, I looked and saw the sad spectacle of Charlie’s house, two hundred yards away, standing in the misty first light of the Californian December; Charlie had been gone two months and all that remained were thirty-eight big black eyes. The house was deserted, no light, no curtains at the windows; thirty-eight blind eyes which wept for the sentimental and lamentable existence of the greatest of screen comedians … And Douglas added: ‘How well that house reflects the existence of the great Chaplin.’

The house with thirty-eight blind windows was truly melancholy, surrounded by its pines and cypresses.11

Contrary to the expectations of Lita’s lawyers, the complaint did not ruin Chaplin; though it would have ruined almost any other man in America. Neither the lawyers nor anyone else could have conceived how deep was the public’s love for him, or that it would survive such smears. Some women’s clubs agitated for a boycott of Chaplin’s films, and in a few backwoods cities and states they succeeded. News of these boycotts produced a strong counter-reaction, which greatly heartened Chaplin, in the form of a protest signed by French intellectuals including Louis Aragon, René Clair, Germaine Dulac and (French by adoption) Man Ray. When Chaplin began to emerge from his seclusion, East Coast society, as if in demonstration, courted and entertained him. He was invited to the Old Timers’ Night of the New York Newspaper Club, and delighted them by performing a pantomime about an ill-fated toreador. It was no waste of effort to win over an influential section of the Eastern press in this way.

Among the innumerable letters of encouragement and support from friends and collaborators, one of the most touching was from the unnamed, plain-faced woman who had worked with him for a day on a scene with tumbling fish, just before the studio close-down:

All I can say is I think you are wonderful and don’t let them break your heart.

Even in the letter, she did not reveal her name, but signed herself simply: ‘Your Fishwoman’.

Sydney was in California and keeping an eye on the studio; careful about money as always, he was troubled to see that there were still ‘several people walking around the studio – such as publicity men etc., and I am wondering if you know they are still on salary and if you want to keep up this big expense as your future actions are so indefinite’. His letter to Chaplin is full of fraternal concern and anxiety:

Dear Charlie:

Because I have not written to you is not that I lack sympathy – you are continually in my thoughts. I hate to imagine how you must have felt when you were on that train, alone, and the news broke. It was like a bomb-shell to me. I did not believe that she could be so vindictive as to actually try to ruin you. She was cutting her own throat. I only just learned the result of the last conference Wright [Loyd Wright, Chaplin’s lawyer] had with her attorneys – I certainly would not pay her a million nor for that matter make any settlement until the government suit was out of the way. Certainly if worse comes to worse the government will take so much there will be nothing left for her any way. She would have a tough time collecting, especially if you go to England for your future work. The more I think of England the more I believe it will be the best thing.

It all seems to me that some one must have a personal grudge against you – I have heard from several people that there has been considerable talk about your socialist tendencies – and as this is a capitalistic government it does not help under the circumstances. I do hate to paint GLOOM but it does seem to me that we should be prepared to go to the other side if things do not shape themselves to our satisfaction … 12

Thoughts of England touchingly stirred old memories:

Do not get too despondent, Charlie, remember there is more in life than great wealth – as long as you know you are comfortably fixed for the future and your health is good it would help to maintain a philosophical attitude toward your troubles. When I am feeling sort of worried, myself, I always think of the great joy, happiness and elated feeling I had when I signed on the dotted line for Fred Karno – just think, the great sum of three pounds a week – why Iran all the way to Kennington Road to send you the glad news. So it seems, after all, that happiness is a matter of comparison and dependent upon our own viewpoint or way of thinking. So CHEER UP OLD KID it will be interesting reading in your biography.13

In this, Sydney was mistaken. Almost forty years afterwards, when Chaplin did finally write his memoirs, the recollection of these desolate times was still too painful to touch on beyond a bare mention: ‘For two years we were married and tried to make a go of it, but it was hopeless and ended in a great deal of bitterness.’

On 2 June Chaplin’s lawyers filed an answer to the complaint. In general this was simply a denial of the charges. It was admitted that the defendant had not visited the plaintiff on occasions when she had left home to holiday in Coronado, California, but that ‘the plaintiff well knew that, because of the fact that at that time the defendant had from two hundred to three hundred people actually working, it would be impossible for this defendant to leave his work and go to Coronado’.

One charge evokes special sympathy for Lita:

3(h) That on several occasions during the past year, defendant had said to plaintiff: ‘Go away some place for a while; I can’t work or create when you are here. You are ruining my career.’ That on one such occasion plaintiff replied to defendant: ‘Why, Charlie, I don’t understand how I interfere with your work. I never see you or annoy you.’ And he replied in a tone of exasperation; ‘That isn’t it. It is just the fact that you are here, and I am supposed to give the usual attention to a home and family. It annoys me, and irritates me, and I cannot work.’14

The answer specifically denied this charge, but added significantly in this connection:

this defendant alleges that during said time, the plaintiff well knew that the defendant was busily engaged in the work of his profession and she at all times well knew of the demands and requirements made upon this defendant, and of the necessity of his devoting his undivided attention to the work of his profession; that the plaintiff was aware that in order for this defendant successfully to produce a good picture, that it was necessary and important that he concentrate upon his work and devote his every attention to it. That during said time this defendant explained to the plaintiff that it was vitally important that he give his undivided attention to his motion picture production.15

One week after the answer was filed, the guards were removed from the studio and the receivers left. In August Lita’s lawyers decided to precipitate matters by announcing that they were ready to name, in addition to the ‘certain prominent moving picture actress’ (i.e. Marion Davies), ‘five prominent moving picture women’ with whom Chaplin had been intimate. These were, Lita later revealed, Merna Kennedy, Edna Purviance, Claire Windsor, Pola Negri and Peggy Hopkins Joyce. Rightly, they estimated that Chaplin was not the man to allow other people’s careers to be ruined as, in the prevailing climate, they certainly would be. To make quite sure, however, Lita herself went to Marion Davies to tell her that she was at the top of the list. Marion, fearful of the possible effect the incident would have upon Hearst, conveyed her terror to Chaplin. The Chaplin lawyers agreed on a cash settlement and the case was settled with a brief, anti-climactic court hearing on 22 August 1927. The judge declined to hear all the unseemly stuff of the complaint. Lita withdrew her charges and asked for an interlocutory decree on the single charge of cruelty. Judge Guerin’s judgement found in her favour, ‘upon the ground of defendant’s extreme cruelty’. She was awarded a settlement of $625,000, with a trust fund of $100,000 for each child, and Chaplin was granted access to his sons. It was the largest divorce settlement in American legal history to that time, and Chaplin’s legal costs amounted to almost one million dollars.

Lita was to find a generous portion of her settlement going to her lawyers, and the case they made for her would in the end ricochet harmfully on her own reputation. The last unsporting gesture of smearing the five women had not helped. Chaplin’s popularity, on the contrary, seemed almost unaffected. One of many similar leading articles in the daily press stated:

CHARLIE IS A REAL HERO

Charlie Chaplin, who has entertained millions on the screen, has never been as satisfying as when he declines to entertain the thrill seekers by refusing to fight the divorce suit of his ‘girl wife’. Charlie ‘stands and delivers’ to the tune of nearly a million dollars, thus depriving his public of another opportunity to determine whether where a film star lives is a home or a night club.

There have been enough lurid stories to last for a while … Whether Charlie was actuated by good taste or good business sense is beside the point His popularity, which is his capital, might seriously have been impaired had Lita been granted the opportunity to ‘tell all’ on the stand. The ‘unnamed actresses’ whom Lita was to have named are as well left in the obscurity of the screen as to the publicity of the printed page. We prefer to see them on the silver sheet showing high emotion by feverish undulation of the diaphragm, to placing them in the witness box to ‘deny the allegation’ with real tears.

It is also a coincidence that Fatty Arbuckle, trying a comeback from a scandal years old, is denied a hearing in Washington, which would have none of him even at this late date. There has been enough washing of movie dirty linen in public to have a depressing effect on more than one reputation which lost its earning capacity.

Whatever the reason, a rising vote of thanks to Charlie for sparing us the minute details of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness with the little woman.

The great comedian Will Rogers was as usual more succinct: ‘Good joke on me. I left Hollywood to keep from being named in the Chaplin trial and now they go and name nobody. Not a name was mentioned but Charlie’s bank. Charlie is not what I would call a devoted husband, but he certainly is worth marrying.’

The Circus was almost finished at the time of the suspension, and the material shot in the few weeks after work was resumed was mostly to fill out what had already been filmed. Further scenes were taken in the circus ring, again entailing bringing back extras – about 250 of them this time – for two days’ work. But fate had not quite done with The Circus. Months before, a location (a squat one-storeyed store on the corner of Lankershim and Hill, in Sawtelle) had been selected for the scene where Charlie is shot right out of the circus tent after his ‘ride for life’ on the tightrope. One day in early October the crew was loaded into seven cars and set out for the location to shoot retakes. Unfortunately Sawtelle was a mushrooming suburb. In the long months since the spot had been selected, the one-storey building had been replaced by an ornate new hotel. A witness of Chaplin’s reaction noted16: ‘A crowd of the curious surge about the big blue car and Charlie is somewhat embarrassed. The tramp atmosphere disappears as a soft English voice remonstrates: “You see, things like this are responsible for the delay.”’ The Lankershim and Hill scene, with its grocery store, then had to be faithfully reconstructed on the studio lot.

At the beginning of October, Chaplin and Crocker were searching Glendale for a suitably deserted and melancholy location for the final scenes of the film. The same reporter described the scene in the small hours of 10 October 1927:

Perspiring men rush about the Chaplin studio. Carpenters, painters, electricians, technical minds, laborers. Charlie must not be held up. A caravan of circus wagons are hitched on behind four huge motor trucks. They start for Cahuenga Pass. A long and hard pull to Glendale. The location is flooded with light. It comes from all directions. The dynamo wagon hums. So the men work through the night.

Daylight breaks. The morning is cold. Crackings echo from a dozen fires. It is an unusual Californian crispness. Cars begin to arrive. The roar of exhausts signals their coming. There is an extra-loud rumbling. The big blue limousine comes to a stop. The Circus must be finished. Everyone is on time. Cameras are set up. Now the sun is holding things up. Why doesn’t it hurry and come up over the mountains? It is long shadows the Tramp wants.

Six o’clock and half the morning wasted. The edge of the circus ring is too dark. It doesn’t look natural. The Tramp refuses to work artificially. Men start to perspire again. Thirty minutes later the soft voice speaks, ‘Fine! That’s fine! Let’s shoot!’ Cameras grind. Circus wagons move across the vast stretch of open space. There is a beautiful haze in the background. The horses and the wagon wheels cause clouds of dust. The picture is gorgeous. No artist would be believed should he paint it. Twenty times the scene is taken.

The cameras move in close to the ring. Carefully the operators measure the distance. From the lens to the Tramp. He is alone in the center of the ring.

He rehearses. Then action for camera. Eighty feet. The business is done again. And again! And again! Fifty persons are looking on. All members of the company. There are few eyes that are not moist. Most of them know the story. They knew the meaning of this final ‘shot’.

‘How was that?’ came inquiring from the Tramp. Fifty heads nodded in affirmation. ‘Then we’ll take it again; just once more,’ spoke the man in the baggy pants and derby hat and misfit coat and dreadnought shoes. The sun was getting high. The long shadows became shorter and shorter. ‘Call it a day,’ said the Tramp, ‘we’ll be here again tomorrow at four’.17

At three the following morning Chaplin was watching the day’s rushes:

The little fellow in the big black leather chair was no longer the Tramp. But he was watching him on the screen. Charlie Chaplin was passing judgement. ‘He should do that much better.’ ‘He doesn’t ring true.’ ‘He has his derby down too far over his eyes.’ ‘They have burned his face up with those silver reflectors.’ A severe critic, this Chaplin. The Tramp doesn’t please him. The stuff must be retaken. A leap from the leather chair. Speed, dust, location.18

Then followed the last of the misfortune dogging The Circus. In the night the wagons had disappeared. The sheriff had his deputies on the job, but there was to be no shooting that day: all that the company could do was to rehearse for retakes, should the wagons ever be recovered. They were, that night. They had been taken by some students who planned to burn them at their fire celebration. An entire freshman class was arrested, but Chaplin declined to prosecute: anything to avoid a further delay. The retakes were made on 14 October.

Even those who worked for years with Chaplin were often mystified by his constant retakes. He might rebuke Totheroh if he heard the camera crank a couple of turns after he had called ‘Cut’, but he would use hundreds of feet retaking some apparently insignificant scene. It was sometimes suggested by his colleagues that when he was stuck for an idea as to what to do next, he would just go on retaking the last thing to hide his indecision. Yet that could not explain the retakes of such a scene as this, taken at the end of a shooting session, when time and light were pressing. The answer must be sought elsewhere. Charlie Chaplin had a compulsion to seek perfection, and equally a conviction that he could never achieve it. He just went on trying.

So much of the film had been edited as the work went along that the final cutting and titling took barely a fortnight. On 28 October the working print of the film was previewed at the Alexandra Theatre, Glendale. (The audience must have been delighted to glimpse the Glendale courthouse used for the scene of the marriage of Rex and Merna.) It was well received, but the reactions suggested some cuts and retakes. For four days Chaplin and Crocker were back on the tightrope for retakes. The close-ups presented some difficulties when it came to matching shots made almost two years before. The anguish of the divorce had left its mark on Chaplin’s features. At the height of the troubles with Lita his hair had gone white overnight: Henry Bergman remembered the shock when the changed Chaplin arrived at the studio one morning. When he began the film his naturally black hair was touched with silver. Now it had to be dyed for the screen.

The revised print was previewed again at Bard & West Adams Theatre on West Adams and Crenshaw, and Miss Steele recorded in the daily studio reports that it ‘went over great’. Chaplin could at last relax. He went on a fishing trip with Harry Crocker.

In the 1920s, even in a small independent organization like Chaplin’s, all the work towards the release and exploitation of films was done within the studio. There were as yet no independent outside laboratories and publicity organizations to undertake the work. So the period between the completion and release of a film was one of the busiest for the staff. The cameramen under Totheroh had to cut two negatives, made on two cameras, for domestic and European release. The laboratory then had to make the release prints – fifteen copies of the film were required for the initial release of The Circus. The press department had to prepare press books, programmes and releases and to supervise the distribution of the stills that were printed in great numbers by the stills department. Meanwhile the last sets had to be struck and cleared, the costumes, properties and electrical equipment carefully renovated, and the studio made ready for the next production.

Chaplin had more than once declared his views on the importance of the musical accompaniment to films. The previews of The Circus had been accompanied by stock themes chosen ad hoc by the theatre’s musical arrangers. For the première performances, however, Arthur Kay was commissioned to compile a special score: Chaplin worked closely with Kay in the final stages.

The world première was held on 6 January 1928 at the Strand Theatre, New York: perhaps Chaplin felt that he owed that city a debt for the refuge it had provided during the troubles of the preceding year. The Los Angeles opening was three weeks later, on 27 January, at Grauman’s Chinese. Sid Grauman provided a spectacular showcase for his friend’s picture. Patrons were greeted on the forecourt of the theatre by a full-scale menagerie and sideshows including Alice from Dallas, the 503-pound fat girl, and Major Mite and Lady Ruth, respectively twenty-five inches tall and twenty-one pounds, and thirty-two inches tall and fifty-two pounds. On the stage a live Prologue starred Poodles Hannaford, the Ace of Riding Clowns, and his troupe, Pallenberg’s Performing Bears on their bicycles, a lion tamer, and Samaroff and Sona’s performing dogs.

Chaplin had no cause to be dissatisfied with his press: the reviews were hardly less enthusiastic than for The Gold Rush. Some critics indeed welcomed a film in which, they felt, the drama and pathos did not eclipse the slapstick element.

At Hollywood’s second Academy Awards ceremony, Chaplin received a special Oscar, inscribed with the citation, ‘To Charles Chaplin for versatility and genius in writing, acting, directing, and producing The Circus’. The Lita affair seemed all but forgotten, barely six months after. Only the journalist Alexander Woollcott touched on it with irony: the film, he said, was overdue

because it was interrupted in the making. I now only vaguely recall the circumstances, but I believe it was because thanks to the witless clumsiness of the machinery of our civilization, someone (a wife I think it was, or something like that) was actually permitted to have the law on Chaplin as though he were a mere person and not such a bearer of healing laughter as the world had never known.19

Woollcott’s uncritical devotion to Chaplin was a byword among his contemporaries, and this romantic move to place the artist above the law might well have invited scepticism. The thought, though, was kind.

It was while working on The Circus that Chaplin embarked for the first and last time on the adventure of producing a film by another director. The most likely reason for this venture was to launch Edna – for whom he evidently no longer saw a place in his own studio – on a new phase of her career, as a dramatic actress. He had been immoderately enthusiastic over Josef von Sternberg’s shoestring production The Salvation Hunters and even more enthusiastic about its star Georgia Hale. Now he invited von Sternberg to direct a film tentatively titled Sea Gulls. ‘This was quite a distinction,’ wrote von Sternberg forty years later in his autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry:

as he had never honored another director in this fashion, but it only resulted in an unpleasant experience for me.

The film was to revolve around Edna Purviance, a former star of his, with whom, among other notable films, he had made the impressive Woman of Paris. She was still charming, though she had not appeared in pictures for a number of years and had become unbelievably timid and unable to act in even the simplest scene without great difficulty. Aware of this, Mr Chaplin credited me with sufficient skill to overcome such handicaps, and in the completed film she actually seemed at ease.

The tentative title of the film was The Sea-Gull [sic] (no relation to the Anton Chekhov tragedy) and it was based on a story of mine about some fishermen on the Californian coast. When the filming had ended I showed it exactly once at one theatre, then titled A Woman of the Sea, and that was the end of that. The film was promptly returned to Mr Chaplin’s vaults and no one has ever seen it again. We spent many idle hours with each other, before, during, and after the making of this film, but not once was this work of mine discussed, nor have I ever broached the subject of its fate to him. He charged off its cost against his formidable income tax, and I charged it off to experience.

Though it did me a great deal of harm at the time, I bore Mr Chaplin no ill will for repressing my work. I have always been fond of him though for a few hours his arbitrary action placed a great strain on my affection.20

Chaplin did not even mention the film in his own autobiography, and the story of Sea Gulls has hitherto been shrouded in myth and mystery. Neither the film itself nor any scenario survives; but the daily shooting records and the title list still preserved in the Chaplin archive enable us to recreate something of its history.

There seems no foundation for the often repeated assertion that the story of the film was Chaplin’s: the credit titles clearly stated ‘written and directed by Josef von Sternberg’. It was in essence a commonplace melodrama about the two daughters of a fisherman: Edna played Joan, the good sister; Eve Southern was Magdalen, the bad one. Magdalen abandons Peter, her simple fisherman fiancé, to go off to the big city with a playboy novelist. Years later, when Joan and Peter are happily married, Magdalen returns to trifle once more with Peter’s affections and disrupt the marriage. Peter and Joan are finally reconciled, however, and the mischievous Magdalen gets her just deserts.

Work on the film began in January 1926, almost simultaneously with The Circus, and continued without break until the end of shooting on 2 June. Cutting was completed three weeks later. The story that Chaplin ordered some retakes is not borne out by the shooting records. Certainly there can be no truth in the frequent assertion that Chaplin himself shot some material on the film, since throughout the production period he was working full out every day on The Circus.

The production – part of which took place on location at Carmel and Monterey – may well have been fraught with difficulties. Von Sternberg seems frequently to have returned to scenes with which he was apparently dissatisfied. When work began, the photographer was Edward Gheller, who had filmed The Salvation Hunters, but on 26 April he was replaced by the twenty-five-year-old, Russian-born Paul Ivano (1901–84), who had previously co-directed Seven Years’ Bad Luck (1921) with Max Linder, acted as technical director on The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) and been one of the forty-two cameramen who shot the chariot race in Ben Hur (1926). Ivano was to be the credited cinematographer, though the bulk of the film was shot by Gheller.

Von Sternberg’s statements about Edna’s condition seem to be confirmed by the daily shooting records. For the most part he was shooting with considerable economy, generally printing the second or third take of a shot. Scenes which demanded work of the slightest complication from Edna, however, seem often to have required nine, ten or more takes. It was said that Sternberg endeavoured to assist her by having two kettle-drums on the set to establish a rhythm for the performance.

Speculation about Chaplin’s reasons for suppressing the film have included the notion – extremely unlikely, given Chaplin’s commercial sense – that he was jealous because von Sternberg had directed Edna so successfully; and, alternatively, that he was distressed by the quality of Edna’s performance. Privately, Chaplin himself said later that the film was simply not good enough to release. Von Sternberg was a man of strong opinions, and the mild tone of his protests might well be taken to imply his own sense of the film’s shortcomings.

John Grierson claimed to have seen the film, and as a seasoned journalist made a good story out of this exclusive privilege. But his rather misleading references to the narrative cast some doubt on the rest of his evidence:

The story was Chaplin’s, and humanist to a degree; with fishermen that toiled, and sweated, and lived and loved as proletarians do. Introspective as before, Sternberg could not see it like Chaplin. Instead, he played with the symbolism of the sea21 till the fishermen and the fish were forgotten. It would have meant something just as fine in its different way as Chaplin’s version, but he went on to doubt himself. He wanted to be a success, and here plainly and pessimistically was the one way to be unsuccessful. The film was as a result neither Chaplin’s nor Sternberg’s. It was a strangely beautiful and empty affair – possibly the most beautiful I have ever seen – of net patterns, sea patterns and hair in the wind. When a director dies he becomes a photographer.

One of the very few people who undoubtedly saw the film was Georgia Hale;22 she corroborated Chaplin’s view that the film was commercially unshowable. It was, she said, wonderfully beautiful to look at23 but the narrative was incomprehensible. Nor did she feel that von Sternberg had wholly overcome the problems of Edna’s nervous state. The eventual fate of Sea Gulls (sometimes known as A Woman of the Sea) is discussed in Chapter 14.