13

Away From It All

When Chaplin left Hollywood on 31 January 1931 – the day following the première of City Lights – neither he nor any of his entourage and friends could have guessed that it would be a year and four months before he would return. His immediate plans were to attend the New York and London premières of the film, and thereafter to take a brief European holiday, perhaps of the duration of the 1921 trip. Chaplin explained: ‘The disillusion of love, fame and fortune left me somewhat apathetic … I needed emotional stimulus … like all egocentrics I turn to myself. I want to live in my youth again.’1

After two disastrous marriages and a succession of inconclusive love affairs, he was without doubt emotionally unsettled. Some of those nearest to him suspected that he was at this time eager to evade the perilous affections of Marion Davies, who by 1931 was a great deal more interested in Chaplin than Chaplin was in her. Certainly he felt disoriented professionally. Four years after the irreversible establishment of talking pictures, he had got away with making what was virtually a silent film; but could he do it again? ‘I was obsessed by a depressing fear of being old-fashioned,’ he later admitted.

No doubt the holiday was a case of playing for time as well as a search for new roles in his private life. ‘He is,’ wrote Thomas Burke, the London writer whom Chaplin had first met in 1921 and who by intuition probably knew him better than anyone else,

first and last an actor, possessed by this, that or the other. He lives only in a role, and without it he is lost … He can be anything you expect him to be, and anything you don’t expect him to be, and he can maintain the role for weeks …

From time to time this imagined life changes. When he was in England ten years ago, he was with every conviction the sad, remote Byronic figure – the friend of unseen millions and the loneliest man in the world. That period has passed. On his last visit to England [i.e. in 1931] his role was that of the playboy, the Tyl Eulenspiegel of today.2

In New York Chaplin was met by the usual crowd of reporters. He regretted undertaking the ordeal of an interview by transatlantic telephone to London, and resolutely refused to do the same for an Australian newspaper. At this time too he refused an offer of $670,000 for twenty-six weekly radio broadcasts – which would have been the highest fee paid to any broadcaster up to that time. Otherwise, apart from the première, his brief time in New York was taken up with social engagements on Fifth or Park Avenue, arrangements for the independent exhibition of City Lights, and a visit to Sing Sing, where he showed his new film to an audience of inmates, and was deeply touched by their enthusiasm. Carlyle Robinson had received a tip-off which made him fear an impending kidnap attempt during the New York stay, and he and Arthur Kelly arranged for Chaplin to be shadowed by two hefty detectives.

Robinson and Kono were to accompany Chaplin to Europe, and Robinson was as usual entrusted with the arrangements. Unfortunately, Chaplin had begun to conceive a dislike of Robinson, and this was to come to a head during the trip, and to result in Robinson’s dismissal after fourteen years’ service. The explanation may have been that Robinson had by this time become more opinionated than Chaplin liked the people around him to be. Robinson frequently joked that his job was less often that of ‘press agent’ than of ‘sup-press agent’; and his constant anxiety to forestall or cover up any indiscretions, faux pas or unintentional discourtesies by his boss cast him in a nannyish role which cannot have made relations with his boss especially easy.

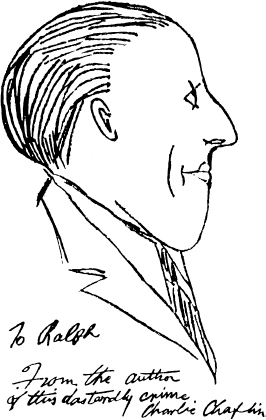

It may have been partly to avoid too much of Robinson’s companionship that Chaplin recruited an extra member of the party at the last moment. This was his friend Ralph Barton, a well-known cartoonist and illustrator, whom Chaplin invited along in the hope that it might allay the acute depression which had already resulted in Barton attempting suicide. Eccentric and hypersensitive, Barton was in deep despair after being deserted by the actress Carlotta Monterey, who had left him to live with the playwright Eugene O’Neill. O’Neill was to become, a dozen years later, Chaplin’s unwilling father-in-law. Coincidence always played a large role in Chaplin’s life.

This last-minute change of plan caused Robinson some embarrassment. Having already negotiated special rates for three berths on the Mauretania,4 less than an hour before sailing he was now obliged to plead for an extra place on the ship, which was in theory fully booked. The problem was solved only by a shipping line official agreeing to share his cabin with Robinson, so that Barton could take Robinson’s place in Chaplin’s personal suite. During the voyage Chaplin finally yielded to the inevitable exhaustion that followed years of work on City Lights. He rarely left his cabin, except for midnight walks on deck with Barton. Out of the mass of radiograms conveying good wishes and pressing invitations, he responded to only three: from Lady Astor, Sir Philip Sassoon and Alistair MacDonald, son of the Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald.

The Mauretania docked at Plymouth and Chaplin was delighted to find a private coach had been provided for the journey to Paddington. The rest of the train was full of journalists, but Chaplin, pleading tiredness, left Robinson to deal with them. Robinson was surprised therefore when the train made an unscheduled stop at a wayside station, and Chaplin enthusiastically set about signing autographs for the large crowd of locals who had assembled merely in the hope of seeing his train pass by. ‘Weren’t they nice people!’ he murmured placidly as the train drew away again. At Paddington the crowds were as vast and excited as they had been at Waterloo ten years before, but the police were better prepared to deal with them; Chaplin obligingly mounted the roof of his car and waved his hat and stick, to general delight.

An enormous suite had been reserved at the Carlton to accommodate Chaplin, Barton, Robinson and Kono; even Chaplin was impressed with its splendour. ‘The saddest thing I can imagine is to get used to luxury. Each day I stepped into the Carlton was like entering a golden paradise. Being rich in London made life an exciting adventure every moment. The world was an entertainment. The performance started first thing in the morning.’3

The ‘performance’ involved a heady social whirl among the intellectual and political elite of London, mainly organized for him by Philip Sassoon, Lady Astor and his old friend Edward Knoblock. At lunch at Lady Astor’s he had a lively debate on the world economy with Maynard Keynes, and met Bernard Shaw for the first time. Initially somewhat intimidated by Shaw, Chaplin decided after an argument or two on the nature of art that he was ‘just a benign old gentleman with a great mind who uses his piercing intellect to hide his Irish sentiment’. He frequently met H. G. Wells, who was now an established friend. He was invited to Chartwell for the weekend by Winston Churchill, whom he was to continue to admire deeply despite their apparent political polarity. (Paradoxical and unpredictable as he was in this respect, Chaplin even took the platform at one of Lady Astor’s meetings at the October 1931 election, though he had some difficulty in explaining both to himself and the audience this support for a Tory candidate.) As guest of honour at a dinner party at Lady Astor’s home at Cliveden, Chaplin startled the guests – carefully chosen from across the political spectrum, including Lloyd George – with an after-dinner speech in which he launched into a diatribe against complacency in face of the menace of the machine age. His audience could hardly have known that they were witnesses to the genesis of Modern Times.

Despite efforts to keep it from the press, Chaplin’s visit to Chequers was much publicized. He seems to have been a little disappointed in the dour Labour premier, Ramsay MacDonald. A private meeting with Lloyd George, arranged by Sassoon, who had served Lloyd George as secretary during his premiership, at least appears to have been more lively, with Chaplin enthusiastically elaborating a scheme for clearance of the London slums.

This time, Chaplin steeled himself to something he had not dared to do in 1921: he visited the Hanwell Schools, where he had spent the loneliest months of his boyhood. Carlyle Robinson believed that he took Ralph Barton with him, but contemporary news reports suggest that he arrived alone and unannounced. As soon as his arrival was known, however, the excitement in the school was intense.

1931 – Form of acknowledgement sent to correspondents during Chaplin’s stay in London.

He entered the dining hall, where four hundred boys and girls cheered their heads off at the sight of him – and he entered in style.

He made to raise his hat, and it jumped magically into the air! He swung his cane and hit himself in the leg! He turned out his feet and hopped along inimitably. It was Charlie! Yells! Shrieks of joy! More yells!

And he was enjoying himself as much as the children.

He mounted the dais and announced solemnly that he would give an imitation of an old man inspecting some pictures. He turned his back and moved along, peering at the wall. Marvel of marvels – as he moved the old man grew visibly! A foot, two feet! A giant of an old man!

The secret was plain if you faced him. His arms were stretched above his head; his overcoat was supported on his fingertips; his hat was balanced on the coat-collar.

He saw the ‘babies’ bathed and in their night attire, sitting for a final warming round the fire, and the babies gave him another ovation, and he laughed like a baby.

The children will never forget his visit.5

The experience seems to have made a great impression on Chaplin. Robinson alleged that he wept when he returned to the Carlton. A day or so later, Chaplin told Thomas Burke that it had been

the greatest emotional experience of his life … He said excitedly that it had been fearful, but that he liked being hurt, and I realized that his cold-blooded nature was interested in the throbbing of the neuralgia and the effects of the throbbing. He loves studying himself.6

Chaplin told Burke,

I wouldn’t have missed it for all I possess. It’s what I’ve been wanting. God, you feel like the dead returning to earth. To smell the smell of the dining hall, and to remember that was where you sat, and that scratch on the pillar was made by you. Only it wasn’t you. It was you in another life – your soul-mate – something you were and something you aren’t now. Like a snake that sheds its skin every now and then. It’s one of the skins you’ve shed, but it’s still got your odour about it. O-o-oh, it was wonderful. When I got there, I knew it was what I’d been wanting for years. Everything had been leading up to it, and I was ripe for it. My return to London in 1921, and my return this year, were wonderful enough, but they were nothing to that. Being among those buildings and connecting with everything – with the misery and something that wasn’t misery … The shock of it, too. You see, I never really believed that it’d be there. It was thirty years ago when I was there, and thirty years – why, nothing in America lasts that long. I wanted it to be. Oh God, how I wanted it to be, but I felt it couldn’t be.

Well, I got a taxi, and told him the direction, and we started out for it. And when we got near the place it was all streets – and shops – and houses. And I guessed it was gone. I don’t know what I’d have done if it was gone. I reckon I’d have gone right back to Hollywood. Because it was what I’d come for. I told the driver to go on, though I didn’t think it was any good, because I’d always remembered that the place was in the country, with fields all round it. And then the taxi stopped … and then turned off the main road into something that looked like country fields and bushes. And then, all of a sudden, th-ere it was. O-o-oh, it was there – just as I’d left it. I’ve never had a moment like that in my life. I was almost physically sick with emotion.7

Burke chided him for his sentimentality in trying to recapture the past he had left behind forever.

‘But one can pick it up and look at it,’ he replied. ‘One can think that one was happy once, or intensely miserable – perhaps it’s the same thing as long as it’s intense – and one can get something by looking at the setting where it happened … And anyway,’ he added, ‘I like being morbid. It does me good, I thrive on it.’8

Moved as he was by their excitement, Chaplin promised the children that he would come back and see them, and bring them a cinema projector as a gift. Robinson was instructed to procure, with the help of United Artists, the most suitable equipment. For each child a present was prepared, consisting of a bag of sweets, an orange and a new shilling in an envelope inscribed ‘A Present from Charlie Chaplin’.

On the day planned for his visit, however, Chaplin decided to lunch with Lady Astor instead. Either the emotional effect of the first visit had proved too powerful, or it had worn off; in either event, no pleas from Robinson could persuade Chaplin to abandon the luncheon. Robinson and Kono were obliged to deliver the gifts, greatly embarrassed to find themselves driving in a limousine through huge crowds who had gathered for a glimpse of their idol. The press, who had also turned out in numbers, did not fail to point out the echoes of The Gold Rush in the tea table set out in the school dining hall for the guest who did not arrive.

The incident attracted the first less than favourable publicity which Chaplin had received since his arrival in England, but for the moment he was too busy with arrangements for the London première of City Lights to worry. The show took place at the Dominion, Tottenham Court Road, on 27 February. The vast crowds who assembled outside the theatre in pouring rain, hoping for a sight of the star, were disappointed: Chaplin and Robinson were smuggled into the theatre during the afternoon before the show. There had been fierce competition for seats near Chaplin. In the event he was flanked by Lady Astor and Bernard Shaw, and was nervous how Shaw would react. But Shaw laughed and cried with the rest. Later a reporter asked him what he thought of the idea of Chaplin playing Hamlet. ‘Why not?’ he replied. ‘Long before Mr Chaplin became famous, and had got no further than throwing bricks or having them thrown at him, I was struck with his haunting, tragic expression, remarkably like Henry Irving’s, and Irving made a tremendous success as Hamlet – or rather of an invention of his own which he called Hamlet.’

Chaplin had planned a small private supper party after the show, but the invitation list rapidly expanded to more than 200, and the affair became the social event of the season. Thomas Burke – who, like H. G. Wells and J. M. Barrie, cautiously declined to attend – remarked that ‘Tyl Eulenspiegel himself never achieved so superb a prank as Charles did when he set the whole Mayfair mob struggling for invitations to his City Lights supper party, and made them give him all the amusement that his films gave them.’9 Titles and talent, the great, the good, and the gifted of London convened, and Chaplin broke the ice with an endearing faux pas when he referred to Churchill in the course of his speech as ‘the late Chancellor of the Exchequer’.

From this evening on, Chaplin threw himself energetically into the role of playboy, which was to amuse him for the next year or so. As if in reaction to the lonely years of work on City Lights, from the moment that the film was launched he embarked with almost adolescent enthusiasm on a series of flirtations and adventures. Contrary to his usual distaste for personal publicity, he appeared to relish the attention as the world’s press delightedly photographed him in the company of a succession of beautiful women, and speculated recklessly on future marriages and leading ladies. The first of the series was Sari Maritsa, who with her friend Vivian Gaye (later Mrs Ernst Lubitsch) had gone to the première and party as guests of Carlyle Robinson. Chaplin intimated his interest, was delighted to find that Miss Maritsa was an accomplished dancer, and thrilled his guests by performing a stylish tango with her. During the rest of this British visit, Sari (whose real name seems to have been Patricia Deterring, and who was later to have a brief Hollywood career) was constantly in Chaplin’s company. Robinson, in his role of ‘sup-press agent’, attempted to put reporters off the track by claiming that Sari was in fact his own girlfriend; but it did not prevent the British newspapers speculating that she would be the star of Chaplin’s next film.

Both in Britain and abroad the press now began to assert confidently that Ramsay MacDonald had recommended Chaplin for a knighthood. Several papers published cartoons celebrating the forthcoming honour; a headline in the Boise (Idaho) Statesman trumpeted inelegantly, ‘Charlie will get Cracked on Dome with King’s Sword’. Suddenly, however, the press declared that the honour would not after all be accorded. The general opinion, openly published, was that the knighthood had been vetoed by the personal intervention of Queen Mary herself, who felt that the Royal Family would be party to some kind of publicity stunt in honouring a motion picture comedian.

More than forty years later, when Chaplin finally received his knighthood from the granddaughter of George V and Queen Mary, a press leak from the Prime Minister’s office revealed that the only explanation recorded for withholding the honour in 1931 was the unfavourable publicity generated by the Northcliffe press during the First World War. The Prime Minister, Ramsay MacDonald, may not have been encouraged by Chaplin’s response when he arranged a dinner in his honour at the House of Commons, to meet a select party of MPs. Chaplin, who had clearly not taken to MacDonald, became less and less enthusiastic about the idea and finally decided that it was imperative that he travel to Berlin the day before the appointment. The premier’s son Alistair MacDonald and Chaplin’s own party were additionally compromised by Chaplin’s refusal to telephone his apologies. He would prefer to write, he said; and then, predictably, did not write either. Finally Sir Philip Sassoon was obliged to follow the Chaplin party to Europe and draft a suitable letter to extricate all concerned from grave embarrassment. The embarrassment was indeed almost compounded at the very moment of Chaplin’s departure, when Sari endeavoured to persuade him to stay in London rather than face the rigours of a stormy Channel crossing. Realizing the affront to the Prime Minister if Chaplin remained in London after having declined the dinner invitation, his friends hurried him, protesting, off to Liverpool Street, where they had taken the precaution of arranging for the train to be delayed for fifteen minutes.

Barton had meanwhile left the group. Despite arriving in seeming high spirits, he had once more declined into acute depression. After the first week or so he could not be persuaded to leave the hotel, but wandered about the suite and the public corridors. On one occasion Robinson found him fingering a revolver and was terrified that he might take Chaplin’s life along with his own. Chaplin was alarmed and irritated to discover that Barton had cut the wires on the electric clocks, for reasons known only to himself. The party at the Carlton were positively relieved when Barton announced his intention to return home. Robinson booked him a passage on the Europa to New York and Chaplin gave him £25 for his expenses, since he was by this time penniless. Two or three weeks after his return to America, Ralph Barton shot himself in the head in his New York apartment.

1931 – Ralph Barton, caricatured by Chaplin.

In the decade since his last visit, Chaplin’s fame had become as great in Germany as in the rest of the world, and the usual dense crowds lined the route from the railway station – where he was met by Marlene Dietrich – to the Hotel Adlon. He was entertained by members of the Reichstag and given a guided tour of Potsdam (which he did not like – but he never approved of palaces) by Prince Henry of Prussia. He visited the Einsteins and was much impressed by the modesty of their apartment and thrilled when Einstein concluded a lively debate on world economics with the compliment, ‘You are not a comedian, Charlie, but an economist.’

By 1931 the political atmosphere in Germany was already ominous. The Nazi press railed against the Berlin populace for losing its head over a ‘Jewish’ comedian from America. Then, on a day when Chaplin had an audience with Chancellor Wirth, ten men claiming to represent unemployed cinema workers arrived at the Adlon, demanding an interview. Robinson said that it was useless for them to try to see him, but they threatened a 10,000-strong demonstration outside the hotel if they did not. Finally three of them were admitted, and Chaplin told them that he was very sorry for their plight but that there were 75,000 unemployed in Hollywood also. An hour later, the Berlin Communist daily newspaper was out with a report that Chaplin had received a delegation of its editors and had expressed deep sympathy with the young Communist cause. The incident clearly annoyed and embarrassed Wirth at the subsequent audience.

Chaplin had the consolation of further romantic encounters, however, with the Viennese dancer La Jana and the American-born actress Betty Amann. Delightful as these flesh-and-blood acquaintances were, he was more permanently impressed by his first sight of Nefertiti in the Pergamon Museum. He at once ordered a facsimile of the bust by the artist who had made a copy for the museum at Munich, and it was to retain a permanent place of honour in his successive homes.

Next the party moved on to Vienna, where the crowds which greeted his arrival were perhaps the most astounding of either of his European trips. Fortunately news film of the event still survives, showing Chaplin being carried over the heads of the multitude, as he was borne all the way from the railway station to the Hotel Imperial. On this occasion, too, Chaplin spoke his first words before a sound film camera, five years before Modern Times. They consisted only of ‘Gute tag! Gute tag!’ repeated rather nervously as he clung tightly to his hat and cane lest they be lost in the sea of faces on which he floated. The romantic encounters of Berlin were forgotten as he discovered shared artistic enthusiasms with the pianist Jennie Rothenstein. The ebullience of the beautiful operetta star Irene Palasthy proved too much for him, however, and he decided not to travel on to Budapest, fearing that the city’s much vaunted female beauties might all prove as demonstrative.

Instead Chaplin and his party travelled to Venice, which made a deep impression upon him although he found it too melancholy to spend more than a couple of days sightseeing. He arrived somewhat fearful that Marion Davies might have landed there on one of her European tours. In fact she arrived a couple of months later, when Chaplin was elsewhere in Europe and thankfully able to decline an invitation to a sumptuous party at her palazzo.

From Venice, Chaplin travelled by train to Paris, where he was to lunch with French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand, and to be decorated with the Légion d’Honneur. Unknown to Chaplin, the decision to make the award was the outcome of representations by a group of his French admirers, led by his first and most faithful Parisian friend, the cartoonist Cami. Cami had in fact come to London during Chaplin’s stay at the Carlton, but Chaplin had been too busy to do more than shake his hand hurriedly as he left the hotel for Liverpool Street on the final night of his stay.

As the train approached Paris the French police came aboard to warn Chaplin that because of the huge crowds he would be advised to leave the train before it arrived at the terminus. They had taken it upon themselves to change his hotel reservation to the Crillon in order to avoid the worst of the mob. Chaplin was irritated by this interference with his plans and refused to leave the train before the terminus, though he agreed to the change of hotel. Despite the crowds and the twelve-strong police guard put around Chaplin, Cami somehow managed to reach his side. However, this irritated rather than pleased Chaplin, who became positively furious when he suspected that Cami was involved in a plot to make him speak into a microphone that was thrust before him. (Cami had been guilty only of yelling in his ear that it would please the mob if he said something like ‘Bonjour, Paris’.) Cami accompanied the Chaplin party to the Crillon, but Chaplin, still angry, insisted on his being ejected. This was, so far as can be discovered, the last time the two men met, although the sentimental Cami never wavered in adoration of his youthful idol.

Apart from the Briand lunch, there were two memorable social occasions in France. For a rather uneasy audience with King Albert of the Belgians, Chaplin was seated on a very low chair while the tall king occupied a much higher one. The incident later gave Chaplin the idea for the meeting of the rival heads of state in The Great Dictator.

On the train to Venice, Chaplin had met the Duke and Duchess of Westminster and unwisely accepted their invitation to a boar hunt at their estate at Saint-Saëns in Normandy. The rigours of the sport left him in need of days of massage. Moreover, ordinarily so careful of his appearance, Chaplin was chagrined to be photographed by press men while wearing an unbecoming hunting outfit made up of items borrowed from the Duke and various guests of assorted sizes. There was to be an echo of this, too, in the ‘animal trainer’ costume in Limelight.

It was now the end of March, and Chaplin decided to move on to the South of France. Sydney had already been settled in Nice for six months: when a variety of factors, both financial and personal, frustrated his plans to set up production in England, he decided that he was sufficiently well off to retire to a life of leisure. Sydney’s apartment was too small for guests, so Chaplin gratefully accepted the invitation of the American millionaire Frank Jay Gould to stay at the Majestic Hotel in Nice, which he owned along with the Casino. Gould had formerly been married to Edith Kelly, sister of Hetty and of Arthur Kelly, who had arranged the invitation.

Chaplin quickly realized that Gould’s eagerness to have him as a guest was not entirely disinterested. Chaplin’s presence at the Majestic and Gould’s other Nice hotel, the Palais de la Mediterranée, was a big draw to the rich and curious local clientele. On the evening of Chaplin’s arrival Gould gave a dinner party in his honour at the Palais, and introduced an admission charge of five francs to the terrasse, from which guests could have a view of Chaplin. The charm of the latest Mrs Gould (there was even talk of Chaplin making her into an actress) diffused Chaplin’s anger, but a number of social activities which Gould had optimistically planned for him were promptly cancelled. However, both Charles and Sydney seem to have been intrigued by Gould’s busy press agent, an engaging, mischievous White Russian called Boris Evelinoff, who combined his work for Gould with a job as correspondent for Le Soir. Evelinoff became a regular member of the Chaplin Riviera circle, and after Chaplin’s return to America was for a while his official representative in Paris – until it became evident that the size of his expense accounts somewhat outweighed the value of his services. Apart from the Goulds, Chaplin mingled with the Riviera set, from the Scottish-American prima donna Mary Garden to the Duke of Connaught. He was especially delighted to meet Emil Ludwig, the biographer of Napoleon, in whom Chaplin always saw an ideal part for himself.

The most significant Riviera encounter was with May Reeves, alias Mizzi Muller, who was to remain for eleven months the exclusive romantic involvement in Chaplin’s life and, more lastingly, was to provide much of the inspiration for the character of Natascha in the script Stowaway, eventually to become A Countess from Hong Kong. May’s past was somewhat mysterious. She appears to have been Czech, and had won prizes in national beauty contests in Czechoslovakia. Arriving on the Riviera she had won a dancing contest, and had made the acquaintance of Sydney.

Following the arrival of the party in the South of France, Robinson had been overwhelmed by the quantity of Chaplin’s correspondence, a large part of it in languages he could not read. He asked Sydney if he could help him find a multilingual secretary and one evening at the Casino Sydney presented May as the ideal candidate for the job, since she spoke six languages fluently. Elegant and beautiful, with the aura of a sophisticated adventuress, May hardly looked the perfect secretary that night. Robinson was pleasantly surprised, however, when she arrived on the stroke of nine the following morning and set about sorting the letters and annotating them with neat little précis translations. Needless to say, he enjoyed the perfect secretary for a mere three hours. May’s charm and beauty won Chaplin the moment he set eyes on her. The same night she was invited to dinner along with Sydney and Robinson, and from that moment became Chaplin’s inseparable companion. He appeared positively stimulated by the intense disapproval of the liaison evinced by everyone around him apart from Kono, who took warmly to the young woman, particularly after she capably nursed him through a severe bout of ptomaine poisoning. The Goulds were outraged that Chaplin should be seen in their establishment with a person so socially dubious; Sydney and Minnie were apprehensive of a new Lita Grey situation; Robinson gritted his teeth in his role of ‘sup-press’ agent.

Chaplin and his hosts both realized that it was time they parted company, but neither found it easy to make the first move. Mrs Gould found the most courteous way out of the impasse: one morning she arrived at Chaplin’s suite, presented him with an exquisite pair of platinum cufflinks, and said graciously how lovely it had been having him there. Chaplin blithely announced that the party, including May and Sydney, would travel to Algeria. He was persuaded with difficulty that it would be better if May travelled on a different boat.

Such ruses did not entirely put the press off the scent, and journalists continued to speculate about Chaplin and ‘the mysterious Mary’, as May was for some reason generally identified. Back at the studios, Alf Reeves did his best to keep the Californian press happy. He told Kathlyn Hayden, whom the studio trusted slightly more than most Hollywood columnists:

Charlie has fallen madly in love … but it’s not what you think! He managed to withstand the charms of all the beautiful ladies of London, Berlin, Paris and Vienna – only to succumb to the allure of – Algiers. And Algiers it is which will be Charlie’s habitat for the next two or three years – or however long it may take him to complete his next film, which will be made entirely in that country.

I understand that reports have been circulated in English and European newspapers to the effect that Charlie’s next film will be made either in London, Paris or Berlin – but the truth is that every scene in the new picture will be shot in Algiers.

Charlie is now at work developing the story. From the sketchy outline which he has cabled me I gather that he will repeat a trick which made a great hit in two of his earlier films – completely altering his appearance at some stage in the story for purposes of disguise. In The Pilgrim old-timers will remember that he dressed up as a clergyman, and in a still earlier film he donned a wig and woman’s clothes. Of course, in the new film, he will be the same little tramp that he always has been, but at some stage of the action circumstances will compel him to disguise himself in the flowing robes of a sheik!10

Nothing more was ever heard of Chaplin’s sheik film. No doubt one of the Chaplin brothers had given this information to Reeves, who was notoriously cautious in statements to the press. To squash other rumours that had filtered back from Europe, Reeves emphasized to Miss Hayden:

Charlie’s leading lady in the new film will most assuredly not be any of the fair ones of London, Berlin and Paris whose names have been mentioned in this connection. She will definitely come from Hollywood.11

Bored with inactivity, Sydney renewed his interest in his brother’s business affairs and succeeded in convincing Chaplin that distribution arrangements both in America and France should be more closely over-seen. This gave Chaplin an excuse to rid himself temporarily of the irksome Robinson, who was despatched to New York with a list of embarrassing matters to investigate. On Robinson’s return to Europe, he and Sydney went together to Paris to look into the distribution arrangements of City Lights in France. No sooner had they arrived than they began to receive a stream of letters from Minnie Chaplin in Nice, gravely alarmed by the growing publicity attracted by the May Reeves affair. Sydney despatched Robinson back to the South of France with unequivocal instructions to put an end the affair, even if it meant telling Chaplin that Sydney had had an affair with the girl himself – he was acutely aware of his brother’s need for monopoly in matters of the heart.

Apprehensive but dutiful, Robinson carried out his commission. He arrived in Marseilles in time to meet the boat bringing Chaplin and May back from Algiers. Racing onto the vessel ahead of the reporters, he managed to persuade the couple to disembark separately, and escorted May himself, so that there were no compromising newspaper pictures. The results of his subsequent efforts to disillusion Chaplin with May were predictable. The relationship of the couple was no doubt impaired, but Robinson’s relationship with Chaplin was terminated – permanently and bitterly. Already irritated by Robinson’s constant presence, Chaplin became furious over the wretched part he was now playing. So, in his turn, did Sydney when he discovered that Robinson had taken him at his word about disclosing his own relationship with May.

Robinson was despatched to New York, where he was appointed the studio’s East Coast representative. At the end of the year he received a letter from Alf Reeves explaining that his services would no longer be required since work on City Lights contracts had more or less finished and Chaplin’s future production plans remained vague. He was given a fortnight’s notice. Robinson was subsequently to publish an embittered but verifiable account of his fifteen years as a Chaplin employee.

Robinson left France at the end of May 1931. Despite some periods of separation, May remained close to Chaplin for the next ten months. She had fallen deeply in love with him. It is impossible to know what were his feelings for her after the initial infatuation had worn off, but there seems no doubt that she was a jolly, affectionate, undemanding holiday companion. From Nice they moved on to the highly fashionable Juan-les-Pins. It was there that Kono had his bout of ptomaine poisoning, to the great alarm of Chaplin, who was sure that his indispensable attendant was about to die. Henri d’Abbadie d’Arrast, the former assistant on A Woman of Paris, devised motor trips to Paris and to his own family home. On one of the trips they were involved in an accident, but Chaplin was unharmed. D’Arrast next persuaded Chaplin to move to Biarritz, where he was entertained at lunch by Winston Churchill. In Biarritz, too, he first met Edward, Prince of Wales, through the introduction of Lady Furness, the former Thelma Morgan Converse. Lady Furness (who had done service as chaperone in the early Lita Grey days) was evidently important in arranging the Prince’s social affairs: it was she who first introduced him to Mrs Wallis Simpson. From Biarritz it was a short trip to Spain, where Chaplin watched a bullfight. He was observed to flinch when the bull attacked the horse. Asked afterwards if he had enjoyed the fight he answered cautiously, ‘I would rather not say anything.’ In later years, following the rise of Franco, Chaplin was adamant in his refusal to return to Spain, even though his daughter Geraldine made her home there.

At the end of August Chaplin returned through Paris to spend the autumn in London. He was both relieved and disturbed to find his reception cooler than the previous winter. It was partly a case of novelty wearing off, but without the protection of a press agent Chaplin had begun to attract some unfriendly notice in the English newspapers. A lady called May Shepherd, who had been hired by Robinson to deal with the continuing avalanche of correspondence arriving in London, demanded an increase of the weekly £5 to which she had originally agreed, since the job had proved much more onerous than anticipated. United Artists and Chaplin’s immediate friends and advisers urged him to agree to her request but he stood firm, regarding it as a matter of principle to hold her to the original agreement. Only after weeks of anxiety for everyone, considerable legal expenses and a good deal of press furore, did Chaplin abruptly agree to settle with Miss Shepherd in full.

The newspapers took more malicious delight in the Royal Variety Performance fracas. While Chaplin was in Juan-les-Pins, he received a telegram from George Black, inviting him to take part in the Royal Variety Performance the following month. There are two different versions of what happened next. One is that, lacking a secretary to deal with his correspondence, Chaplin simply overlooked the invitation. Most papers, however, reported that he had declined to appear, saying that he never appeared on the stage. (In one interview he said that it would be ‘bad taste’ for him to do so.) Instead he sent a donation of $1000 with the rather acid comment that this represented his earnings in his last two years of residence in England.

The popular press, perversely ignoring the fact that the Variety Performance is a Royal, but not a Royal Command performance, represented Chaplin’s refusal as an insult to the King. Chaplin was, quite reasonably, incensed. Unfortunately he compounded his problems by pouring out his indignation to a young man he met on the tennis court in Juan, without being aware that he was a reporter (he was missing his ‘sup-press’ agent):

They say I have a duty to England. I wonder just what that duty is. No one wanted me or cared for me in England seventeen years ago. I had to go to America for my chance and I got it there.

… Then down here [at Juan-les-Pins] I sat one night patiently waiting for the Prince of Monaco, and it appears that I was insulting the Duke of Connaught.

Why are people bothering their heads about me? I am only a movie comedian and they have made a politician out of me.

He went on to express some forthright opinions on the subject of nationalism, which he called ‘patriotism’:

Patriotism is the greatest insanity the world has ever suffered. I have been all over Europe in the past few months. Patriotism is rampant everywhere, and the result is going to be another war. I hope they send the old men to the front the next time, for it is the old men who are the real criminals in Europe today.

More than thirty years afterwards Chaplin had found no reason to modify his views: ‘How can one tolerate patriotism, when six million Jews were murdered in its name?’ Prescient as his opinion was, however, it was far from fashionable in the England of 1931, and was widely criticized.

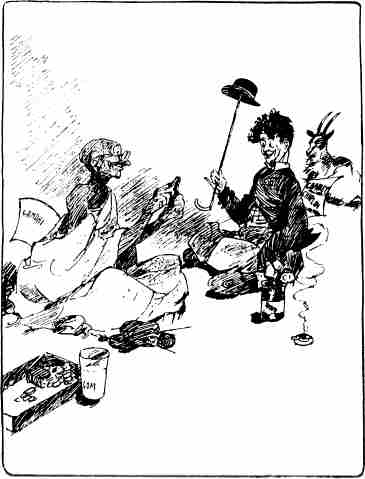

The fickleness of the press had no effect upon Chaplin’s social life in England. He saw the Prince of Wales several times and was invited to Fort Belvedere, the Prince’s residence near Virginia Water, for the weekend. This opened up to him a good many more doors than he cared to enter. Among the celebrated London hostesses who entertained him were Margot Asquith, Lady Oxford, Sibyl Lady Colefax and Lady Cunard. Late in September there was a much publicized meeting with Gandhi, who was then visiting England and lodging in a modest house in East India Dock Road. The interview had a special piquancy since Gandhi was one of the very small handful of people in the world who did not know who Charlie Chaplin was, and had certainly never seen one of his films. The Mahatma was affable and gracious, however, and politely exchanged economic ideas with his guest before inviting him to stay and watch him at prayers. Chaplin left with the impression of ‘a realistic, virile-minded visionary with a will of iron’.

1931 – Caricaturist’s view of the encounter between Chaplin and Gandhi.

Chaplin also observed the autumn election, which resulted in a victory for the National government, and accompanied some of his politician friends to election meetings. He made a sentimental journey to Lancashire in search of scenes he remembered from days on tour with Sherlock Holmes and in variety. He found Manchester on a Sunday ‘cataleptic’ and so drove on to Blackburn, which had been one of his favourite towns on tour. He found the pub where he used to lodge for fourteen shillings a week and had a drink in the bar, unrecognized.

He was now ready to return to the United States, but the holiday was to be extended. Douglas Fairbanks invited him to St Moritz for the ski season. Chaplin went there in company with Lady Cholmondeley and subsequently they were joined by May Reeves and Sydney. Having hitherto always expressed an aversion to mountains in general and Switzerland in particular, Chaplin stayed on throughout January and February, until the season was coming to an end and Sydney, Douglas and Lady Cholmondeley had all returned home.

On the way to St Moritz in December 1931 Chaplin seems to have passed briefly through Vienna. Sadly, an intended meeting with Sigmund Freud did not take place, but Freud happily recorded a brisk analysis of the links between Chaplin’s work and psychology:

You know, for instance, in the last few days Charlie Chaplin has been in Vienna. I, too, almost got to see him, but it was too cold for him here and he left again quickly. He is, undoubtedly, a great artist; certainly he always portrays one and the same figure: only the weakly, poor, helpless, clumsy youngster for whom, however, things turn out well in the end. Now do you think that for this role he has forgotten about his own ego? On the contrary, he always plays only himself as he was in his early dismal youth. He cannot get away from those impressions and to this day he obtains for himself the compensation for the frustrations and humiliations of that past period of his life. He is, so to speak, an exceptional simple and transparent case. The idea that the achievements of artists are intimately bound up with their childhood memories, impressions, repressions and disappointments, has already brought us much enlightenment and has, for that reason, become very precious to us.12

Chaplin now decided to prolong his holiday still further with a visit to Japan, a country in which his interest had been excited two years earlier with the visit of the Japanese Kengeki theatre to California. He wired an invitation to Sydney in Nice and it was arranged that they would meet in Naples. Chaplin, Kono and May travelled through Italy via Milan and Rome, where a planned audience with Mussolini failed to take place. On the quayside at Naples Chaplin bade his final farewell to the devoted May. His last sight of her as the ship pulled out was on the dock, bravely attempting to smile and doing an imitation of his tramp walk.

Sydney, fiercely protective of his brother and constitutionally suspicious of the rest of the world, continued to worry that there would be some bad aftermath to the affair. His fears came to a head a year later, when Boris Evelinoff’s engagement as Paris representative was terminated. Sydney confided to Alf Reeves his fears that Evelinoff might have entered into some sort of league with May:

I would not be surprised if a story broke in the Paris Midi relating the whole history of that affair, although Robinson has taken the edge off. The reason I mention this is because Evelinoff came to Cannes and hit upon a story of a girl who had been the mistress of a certain Balkan king. I met the girl and heard the proposition made to her to spew up all she knows. The king having given her up, she agreed to do so, and now the story is appearing in the Paris Midi under the glaring headlines ‘From the Folies Bergère to the Throne’. At the time Evelinoff was arranging this, May was living in the same hotel as Boris at exceptionally low terms arranged by him. She left Cannes about the same time as he did. The other day in Paris Minnie phoned Boris at his house, the secretary answered, and Minnie feels sure it was May’s voice, so perhaps she is also writing her life story.13

It must have seemed to Sydney that his nightmares were to become reality when, in 1935, May actually published her recollections of those eventful months in book form, as Charlie Chaplin intime, edited by Claire Goll. But his fears were unfounded. May’s memoirs proved that she was no sophisticated and scheming adventuress but the cheerful, somewhat naive young woman who had provided Chaplin with the ideal Riviera playmate. Her book was a touching, tedious declaration of affection, forgiveness and regret.

Chaplin and Sydney embarked on the Suwa Maru on 12 March 1932. In Singapore the journey was delayed when Charlie contracted a fever. When he recovered they moved on to Bali, whose people and culture thrilled and astonished Chaplin. The brothers shot some 400 metres of film on the island, and were rather proud of it: unfortunately the best parts were lost through some rather dubious activity on the part of a Dutch cameraman, Hank Alsern, whom they entrusted with the editing.

In the second week of May they arrived in Tokyo to huge crowds and a welcome as spectacular as Chaplin was accustomed to encounter in Europe. He responded with genuine enthusiasm and excitement to every aspect of Japanese culture – the geishas, the tea ceremony, wood-block prints and the drama. However, the visit was overshadowed by a series of sinister events connected with the activities of an ultra-rightist group, the Black Dragon Society, which temporarily considered Chaplin as a likely assassination target. There were vague and not so vague menaces, of which Kono, as interpreter, bore the brunt. Then one night, while the party was in the company of the young son of the Premier, Tsuyoshi Inugai, the Premier himself was murdered by six extremists.

Finally, on 2 June 1932, Chaplin set sail with Kono on the Hikawa Maru from Yokohama to Seattle. The day before they sailed, Sydney, who was to make his separate way to Nice, wrote to Alf Reeves:

Charlie is returning home with the solution to the world’s problems, which he hopes to have put before the League of Nations. He has been working very hard on this solution and I must say that he has hit upon an exceptionally good idea.14

During the homeward voyage Chaplin continued to work on his economic theory as well as on some preliminary notes for Modern Times. Perhaps this contemplation of the world’s problems provided a distraction from the problems of his own studio, which he had now to face. Since the completion of City Lights, the establishment on La Brea and Sunset had suffered its share of the effects of the general depression in the film industry. Knowing Chaplin’s lifelong habit of delegating to others any unpleasant or graceless duties, it is possible that one factor for his prolonged absence was the desire not to witness, or to be seen as responsible for, the current situation at the studio. On 23 April 1931, Alf Reeves had reported to Carlyle Robinson, who was then in Paris:

You can tell the Chief the staff here is reduced to the minimum. Rollie, Mark, Morgan, Ted Miner, Anderson and Val Lane are all gone. I have retained Jack Wilson as a librarian and laboratory man. The carpenters, electric and paint shops are closed. The small staff we have here is very busy, and we have plenty to do. Most of the people who have left are out and things look pretty bad. The stock market is all to pieces but we are hoping for the best.

P.S. General conditions are still bad here. The picture business is going down generally.15

Henry Bergman seems to have been kept on a retainer, because in August 1932, it was widely reported in the press that he had declined to accept his weekly salary of $75 any longer, unless the studio was in active production. Bergman at that time had an income from his restaurant. For the others laid off, life would have been difficult. Rollie Totheroh’s son Jack remembers having to take along food and other necessities for his father; Rollie himself published a couple of cartoons urging Chaplin to get back to work so that the studio might reopen.

These were hard times for everyone. Since leaving the studio, Edna had resolutely refrained from asking for any help from Chaplin apart from the monthly retainer she was paid, and remained anxious not to impinge in any way upon his life. During the period of his holiday, however, things had become so difficult for her that she was finally forced to seek assistance, in a poignant letter:

Dear Charlie,

Fearing I might bother you and trouble you, I have hesitated writing, but finding it absolutely necessary I am doing so, hoping you will not be angry and misconstrue my real thoughts toward you, as they are constantly for you and with you on your so long and interesting travels. However you said many years ago (perhaps you have forgotten) what you were going to do, have been doing and are doing, and though you may not know I have been [watching] very silently and with the greatest pride your most every act.

Am just recuperating from severe illness, which almost terminated with the final rest. But to my great joy and gladness am feeling better than ever before in my life. On [illegible] 29 I was stricken with a perforated ulcer … which caused haemorrhage in my stomach and was rushed to hospital. The first day four doctors worked constantly on me with the result of no result what-so-ever. Being unconscious but with apparently subconscious determination I rallied with the aid of every known heart stimulant and one good doctor. Saline was administered into the blood stream for one week as I was unable to take any other form of nourishment. I was in a run down condition to begin with from a bad cold. So to add to all I almost had pneumonia. All told it was a battle …

The same night I was stricken, my father died, but I was too ill to be told of it. He was 84 years old, and of course not able to support himself for years. I have been sending him a small check every month to live on. So when friends notified us of his death, they wanted me to send the money for burial expenses. My mother in desperation went to see Alf Reeves and asked if he could lend the financial aid needed, as I only had about $300 in cash in the bank at the time, and money was needed every day at the hospital, so she knew we could not send that for burial purposes. I like others lost $2,300 in the Fidelity Loan and Trust Co. So perhaps you can see why I was and am short of money. Mother again appealed to Alf, and he kindly let her have $750.00 – $350 for burial of my father and the rest for hospital and nurses. On top of this my Drs bill is $700 and $50 for heart specialist. So all in all I am in a most difficult and needy situation.

Charlie I know it is bothersome and a dam nuisance to have to read of or listen to anyone’s troubles, and I feel that you know well enough I would not take up your time, not even for a second, unless I simply had to. Please forgive me.

Will be so happy to see you back here. But I wonder how long you will be interested enough to stay?

All my love,

EdnaApril 3 1932

P.S. Saw by the papers that Minnie was here – Am going to telephone her.16

There is no surviving evidence of Chaplin’s response to this appeal.

In 1932, Chaplin was nearing the mid-point of both his actual and his professional life. We are fortunate to possess from this time the most searching and perceptive portrait ever written of him. It is an essay entitled ‘A Comedian’ in Thomas Burke’s City of Encounters, published in 1933. Burke and Chaplin had first met in 1921 (Chaplin had been very excited by Burke’s book Nights in Town), maintained contact over the years, and met again during Chaplin’s 1931 holiday. Chaplin invited Burke to take the unhappy Barton’s place as his travelling companion on the trips to Berlin and Spain, but Burke refused: ‘I knew that a fortnight of proximity to that million-voltage battery would have left me a cinder.’

In his fifty-page essay, which is essential to the discovery of Chaplin, Burke compares his character to that of Dickens:

A man of querulous outlook, self-centred, moody, and vaguely dissatisfied with life. That is the kind of man he is.

Or nearly. For to get at him is not easy. It is impossible to see him straight. He dazzles everybody – the intellectual, the simple, the cunning, and even those who meet him every day. At no stage can one make a firm sketch and say: ‘This is Charles Chaplin.’ One can only say: ‘This is Charles Chaplin, wasn’t it?’ He’s like a brilliant, flashing now from this facet and now from that – blue, green, yellow, crimson by turns. A brilliant is the apt simile; he’s as hard and bright as that, and his lustre is as erratic. And if you split him you would find, as with the brilliant, and as with Charles Dickens, that there was no personal source of those changing lights; they were only the flashings of genius. It is almost impossible to locate him. I doubt if he can locate himself; genius seldom can … 17

Burke attempts it, nonetheless:

For the rest he is all this and that. He is often as kind and tender as any man could be, and often inconsiderate. He shrinks from the limelight, but misses it if it isn’t turned upon him. He is intensely shy, yet loves to be the centre of attention. A born solitary, he knows the fascination of the crowd. He is really and truly modest, but very much aware that there is nobody quite like Charles Chaplin. He expects to get his own way in everything, and usually gets it. Life hampers him; he wants wings. He wants to eat his cake and have it. He wants a peau de chagrin* for the granting of all his wishes, but the peau de chagrin must not diminish. He makes excessive demands upon life and upon people, and because these demands cannot always be answered he is perplexed and irritated. He commands the loyalty of friends while being casual himself. He takes their continuing friendship for granted. He likes to enjoy the best of the current social system, while at heart he is the reddest of Reds. Full of impulsive generosities, he is also capable of sudden changes to the opposite … He takes himself seriously, but he has a sharp sense of humour about himself and his doings. He has a genuine humility about the position he has won, but, like most other really humble artists, he doesn’t always like you to take the humility as justified. For two hours he will be the sweetest fellow you have ever sat with; then, without apparent cause, he will be all petulance and asperity. Like a child, his interest is quickly caught and he is quickly bored. In essence he is still a Cockney, but he is no longer English – if he ever was. In moments of excitement, and in all his work, the Cockney appears. At other times he is, in manners, speech and attitude, American. He is not at all in sympathy with the reserved English character, and he cares little for England and English things … He is by no means contemptuous of money, but the possession of a very large sum means little to him. It represents economic safety, nothing else. He likes plain bourgeois foods – on his visit to England he was babbling to me of kippers, bloaters, tripe, sheep’s heart – and, although he has a large wardrobe, he prefers old clothes and no fuss. Drink doesn’t interest him, and he smokes one or none to my twenty.

He is one of the most honest of men. If you ask his opinion on anything or anybody you get it straight and clear. Most of us have some touch of humbug about us, but Charles has none. You can accept anything he says for the truth as he sees it. A point of his honesty is his selfishness. Most of us are selfish, in one way or another, but are annoyed if people bring the accusation … Yet selfish people are usually the more agreeable. By pleasing themselves they maintain a cheerful demeanour to those about them. Charles lives as most of us would if we had the necessary nerve to face ourselves as we really are – however disturbing the ‘really’ might be to our self-esteem. He will only do what he wants to do. If any engagement is in opposition to his mood of the moment he breaks it, and if asked why he didn’t keep it he will blandly answer – Because he didn’t want to. In whatever company he may be, he is simple and spontaneous. He may be always living in a part, but he never poses; he has a hatred of sham …

His life at home, despite the Japanese valets and cooks and chauffeurs, is not the glamorous, crowded affair that some people imagine it to be. He told me that he leads almost as humdrum a life as a London clerk. He is not over-popular in that lunatic asylum – one could hardly expect Hollywood to know what to make of a poet – and they leave him pretty much to himself …

His mind is extraordinarily quick and receptive; retentive, too. He reads very little, but with a few elementary facts on a highly technical subject, his mind can so work upon them that he can talk with an expert on that subject in such a way as to make the expert think. He thus appears a very well-read and cultivated man when, in fact, his acquaintance with books is slight. With little interest in people, he yet has a swifter and acuter eye than any novelist I know for their oddities and their carefully hidden secrets. It is useless to pose before him; he can call your bluff in the moment of being introduced …

He is now [1931] forty-two in years, but he cannot live up to that age, and never will. His attitude and his interest are always towards youth and young things. He takes no concern in the historical past; his spiritual home is his own period. He is intensely a child of these times, and his mind finds nothing to engage it farther back than his own boyhood. ‘I always feel such a kid,’ he told me once, ‘among grown-ups …’18