|

2

Examining the Project Life Cycle and the Organization

|

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

Project management, the ability to get things done, must support the higher vision

of the organization in which the project management activities are occurring. Projects

must be in alignment with the organization’s vision, strategy, tactics, and goals.

Projects that are not in alignment with the higher vision of the organization won’t

be around long—or, at best, they are doomed to fail.

Project managers must realize and accept that their projects should be components

that support the vision of the organization where the project is being completed.

It occasionally happens that projects are chartered and initiated and are not in alignment

with the company strategy. Unless the company strategy changes, these projects can

face political and organizational cultural challenges.

At the launch of a project, the project manager must have inherited the vision of

the project. This person must understand why the project is being created and what

its purpose is in the organization. It’s also beneficial to know the priority of the

project and its effect on the organization. A project to install pencil sharpeners

throughout the company’s shop floor may be important, but it’s not as significant

as the project to install new manufacturing equipment on the shop floor.

In this chapter, we’ll cover how the life of a project, the interest of stakeholders,

and the organization’s environment influence the success and completion of projects.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 2.01

Identifying Organizational Models and Attributes

Projects are not islands. They are components of larger entities that work to create

a unique product or service. The larger entities, organizations, companies, or communities

will have direct influence over the project itself. Consider the values, maturity,

business model, culture, and traditions at work in any organization. All of these

variables can influence the progress and outcome of the project.

Project managers must also consider the legal requirements and influences over their

projects. In the United States, this includes laws and regulations such as Sarbanes-Oxley,

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), Occupational Safety and

Health Act (OSHA), and others. Projects can also be influenced by communities, other

companies (when joint ventures exist), and professional associations. As a rule, the

larger the project scope, the more influencers the project manager can expect.

Project managers must recognize the role of the project as a component within an organization.

The role of the project, as a component, is to support the business model of the organization

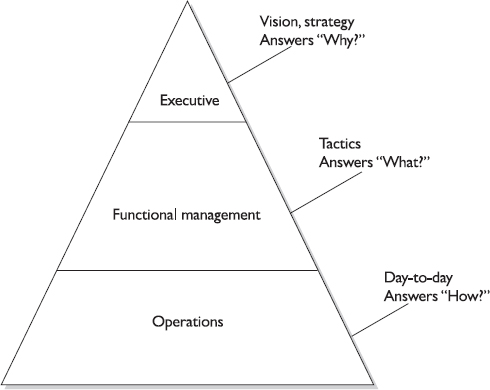

as a whole—not replace it. You can see in Figure 2-1 the major layers and purpose of the components within most organizations. Notice

that each layer of the pyramid answers a specific question in relation to the project.

FIGURE 2-1 Each layer of an organization supports the layer above it.

The Executive Layer sets the vision and strategy of the organization. The Business

Layer asks, “Why is the project important to our organization? Our vision? Our strategy?”

The Executive Layer sets the vision and strategy of the organization. The Business

Layer asks, “Why is the project important to our organization? Our vision? Our strategy?” The Functional Management Layer of the pyramid must support the Executive Layer’s

objectives. Specifically, the Functional Management Layer is concerned with tactics

to accomplish the vision and strategy as established by upper management. The Functional

Management Layer asks, “What is the project purpose? What business processes are affected?”

The Functional Management Layer of the pyramid must support the Executive Layer’s

objectives. Specifically, the Functional Management Layer is concerned with tactics

to accomplish the vision and strategy as established by upper management. The Functional

Management Layer asks, “What is the project purpose? What business processes are affected?” The Operational Layer of the pyramid supports the Executive and Functional Management

Layers. This layer is concerned with the specifics of getting the work done. The Operational

Layer asks, “How can the work be accomplished? How can we reach the desired future

state with these requirements?”

The Operational Layer of the pyramid supports the Executive and Functional Management

Layers. This layer is concerned with the specifics of getting the work done. The Operational

Layer asks, “How can the work be accomplished? How can we reach the desired future

state with these requirements?”Considering Organizational Systems

What kind of an organization are you in? Does your organization complete projects

for other entities? Does your organization treat every process of an operation as

an operation? Or does your organization not know what to do with people like you:

project managers?

When it comes to project management, organizations fall into one of three models:

Completing projects for others These entities swoop into other organizations and complete the project work based

on specifications, details, and specification documents. Classical examples of these

types of organizations include consultants, architectural firms, technology integration

companies, and advertising agencies.

Completing projects for others These entities swoop into other organizations and complete the project work based

on specifications, details, and specification documents. Classical examples of these

types of organizations include consultants, architectural firms, technology integration

companies, and advertising agencies. Completing projects internally through a system These entities have adopted Management by Projects (discussed in Chapter 1). Recall that organizations using Management by Projects have accounting, time, and

management systems in place to account for the cost, time, and worth of each project.

Completing projects internally through a system These entities have adopted Management by Projects (discussed in Chapter 1). Recall that organizations using Management by Projects have accounting, time, and

management systems in place to account for the cost, time, and worth of each project. Completing projects as needed These non-project–centric entities can complete projects successfully but may not

have the project systems in place to support projects efficiently. The lack of a project

support system can cause the project to succumb to additional risks, lack of organization,

and reporting difficulties. Some organizations may have special internal business

units to support the projects in motion that are separate from the accounting, time,

and management systems used by the rest of the organization.

Completing projects as needed These non-project–centric entities can complete projects successfully but may not

have the project systems in place to support projects efficiently. The lack of a project

support system can cause the project to succumb to additional risks, lack of organization,

and reporting difficulties. Some organizations may have special internal business

units to support the projects in motion that are separate from the accounting, time,

and management systems used by the rest of the organization.

Know that customers can be internal or external, but they all have the same theme:

Customers pay for or use the product deliverables. In some instances, they’ll pay

for and use the deliverables. When an organization partners with another entity to

complete a project, the organizational influence becomes more cumbersome. The two

entities can both affect how the project is managed.

Considering Organizational Culture

Imagine what it would be like to work as a project manager within a bank in downtown

London versus working as a project manager in a web development company in Las Vegas.

Can you picture a clear difference in the expected cultures within these two entities?

The organizational culture of an entity will have a direct influence on the success

of a project. Organizational culture includes the following:

Policies and procedures for managing projects in the organization

Policies and procedures for managing projects in the organization Industry regulations, policies, rules, and methods for doing the work

Industry regulations, policies, rules, and methods for doing the work Values, beliefs, and expectations

Values, beliefs, and expectations Views of authority, management, labor, and workers

Views of authority, management, labor, and workers Work ethic

Work ethic Expectations on hours worked and contributions made

Expectations on hours worked and contributions made Views toward organizational leadership

Views toward organizational leadershipAs you can imagine, projects with more risk (and expected reward) may be welcome in

an organization that readily accepts entrepreneurial ventures rather than in an organization

that is less willing to accept chance and risk. Project formality is typically in

alignment with the culture of an organization.

Another influence on the progress of a project is the management style of an organization.

A project manager who is autocratic in nature will face challenges and opposition

in organizations that allow and encourage self-led teams. A project manager must take

cues from management as to how the management style of a project should operate. In

other words, a project manager emulates the management style of the operating organization.

The unique style and culture within each organization is called the “cultural norm.”

It’s just a way to describe the expectations of behavior within an organization. You

won’t find the same cultural norm in my company, a small and limber management consulting

and training firm, as you would in a Wall Street-based international investment firm.

You should also know that the cultural norm in an organization is also an enterprise

environmental factor for the project manager.

As a general rule, the larger the project, the more people will be involved. More

people, as you might anticipate, means you’ve more communications work to do as the

project manager. Projects that span across the globe have additional challenges for

communications: languages, time zones, technological barriers, and cultural differences.

We’ll talk more about communications management in Chapter 10, but for now you’ll need to be aware that expectations for communications, available

technologies to communicate, and the cultural of the people involved in the communications

are all part of the organization’s influence on the project’s success.

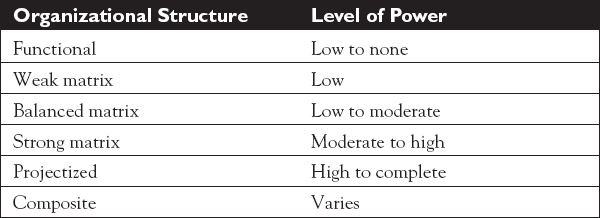

Completing Projects in Different Organizational Structures

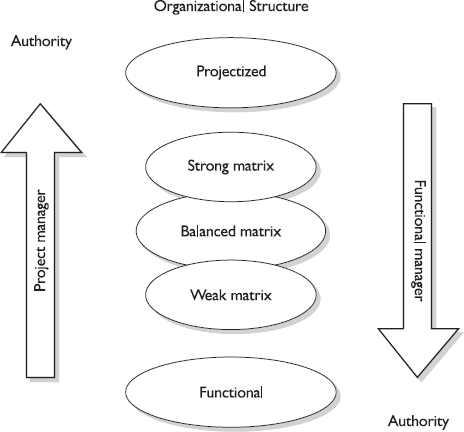

Organizations are structured into one of six models, the organizational structure

of which will affect the project in some aspect. In particular, the organizational

structure will set the level of authority, the level of autonomy, and the reporting

structure that the project manager can expect to have within the project. Figure 2-2 shows the level of authority in each of the organizational structures for the project

manager and the functional manager.

FIGURE 2-2 The organizational structure affects the project manager’s authority.

We’ll discuss the following organizational structures:

Functional

Functional Weak matrix

Weak matrix Balanced matrix

Balanced matrix Strong matrix

Strong matrix Projectized

Projectized Composite

Composite Being able to recognize your organizational structure with regard to project management

will allow you to leverage and position your role effectively as a project manager.

Being able to recognize your organizational structure with regard to project management

will allow you to leverage and position your role effectively as a project manager.Functional Organizations

Functional organizations are entities that have a clear division regarding business

units and their associated responsibilities. For example, a functional organization

may have an accounting department, a manufacturing department, a research and development

department, a marketing department, and so on. Each department works as a separate

entity within the organization, and each employee works in a separate department.

In these classical organizations, there is a clear distinction between an employee

and a specific functional manager.

Functional organizations do complete projects, but these projects are specific to

the function of the department the project falls into. For example, the IT department

could implement new software for the finance department. The role of the IT department

is separate from the role of the finance department, but the coordination between

the two functional departments would be evident. Communication between departments

flows through functional managers down to the project team. Figure 2-3 depicts the relationships between business departments and the flow of communication

between projects and departments.

FIGURE 2-3 Projects in functional organizations route communications through the functional

managers.

Project managers in functional organizations have the following attributes:

Little power

Little power Little autonomy

Little autonomy Report directly to a functional manager

Report directly to a functional manager May be known as project coordinators or team leaders

May be known as project coordinators or team leaders Have a part-time role (the project team will also be part-time as a result)

Have a part-time role (the project team will also be part-time as a result) May have little or no administrative staff to expedite the project management activities

May have little or no administrative staff to expedite the project management activitiesMatrix Structures

Matrix structures are organizations that utilize employees that perform a blend of

departmental and project duties. This type of structure allows for project team members

to be from multiple departments, yet all work toward the project completion. In these

instances, the project team members have more than one boss. Depending on the number

of projects a team member is participating in, he may have to report to multiple project

managers as well as to his functional manager.

Weak Matrix

Weak matrix structures map closely to a functional organization. The project team

may come from different departments, but the project manager reports directly to a

specific functional manager. In weak matrix organizations, the project manager has

the following attributes:

Limited authority

Limited authority Management of a part-time project team

Management of a part-time project team Project manager’s role is part-time

Project manager’s role is part-time May be known as a project coordinator or team leader

May be known as a project coordinator or team leader May have part-time administrative staff to help expedite the project

May have part-time administrative staff to help expedite the projectBalanced Matrix

A balanced matrix structure has many of the same attributes as a weak matrix, but

the project manager has more time and power regarding the project. A balanced matrix

still has time-accountability issues for all of the project team members, since their

functional managers will want reports on their time spent on the project. Attributes

of a project manager in a balanced matrix include the following:

Reasonable authority

Reasonable authority Management of a part-time project team

Management of a part-time project team Full-time role as a project manager

Full-time role as a project manager May have part-time administrative staff to help expedite the project

May have part-time administrative staff to help expedite the projectStrong Matrix

A strong matrix equates to a strong project manager. In a strong matrix organization,

many of the same attributes for the project team exist, but the project manager gains

power and time when it comes to project work. The project team may also have more

time available for the project even though they may come from multiple departments

within the organization. Attributes of a project manager in a strong matrix include

the following:

A reasonable to high level of power

A reasonable to high level of power Management of a part-time to nearly full-time project team

Management of a part-time to nearly full-time project team A full-time role as a project manager

A full-time role as a project manager A full-time administrative staff to help expedite the project

A full-time administrative staff to help expedite the projectProjectized Structure

At the pinnacle of project management structures is the projectized structure. These

organizational types group employees, collocated or not, by activities on a particular

project. The project manager in a projectized structure may have complete, or very

close to complete, power over the project team. Project managers in a projectized

structure enjoy a high level of autonomy over their projects, but they also have a

higher level of responsibility regarding the project’s success.

Project managers in a projectized structure have the following attributes:

High to complete authority over the project team

High to complete authority over the project team Work full-time on the project with their team (though there may be some slight variation)

Work full-time on the project with their team (though there may be some slight variation) A full-time administrative staff to help expedite the project

A full-time administrative staff to help expedite the projectComposite Organizations

On paper, all of these organizational structures look great. In reality, there are

very few companies that map only to one of these structures all of the time. For example,

a company using the functional model may create a special project consisting of talent

from many different departments. Such project teams report directly to a project manager

and will work on a high-priority project for its duration. These entities are called

composite organizations, in that they may be a blend of multiple organizational types.

Figure 2-4 shows a sample of a composite structure. Although the AQQ Organization in the figure

operates as a traditional functional structure, they’ve created a special projectized

project where each department has contributed resources to the project team.

FIGURE 2-4 Composite structures are a blend of traditional organizational structures.

The functional manager controls the project’s budget in the functional, weak matrix,

and to some extent in the balanced matrix. The project manager gains budget control

in the strong matrix and projectized organizations.

Table 2-1 outlines the benefits and drawbacks of various organizational types.

TABLE 2-1 Benefits and Drawbacks of Various Organizational Types

Relying on Organizational Process Assets

“Organizational process assets” is a nice way of referring to all of the resources

within an organization that can be used, leveraged, researched, or interviewed to

make a project successful. This means past projects, risk databases, procedures, plans,

processes, and methods of operations. Of course, organizational assets will vary from

industry to industry, but for the PMP exam, consider all of the following:

Standards, policies, and organizational procedures

Standards, policies, and organizational procedures Standardized guidelines and performance measurements

Standardized guidelines and performance measurements Templates for project documents such as contracts, work breakdown structures, project

network diagrams, and status reports

Templates for project documents such as contracts, work breakdown structures, project

network diagrams, and status reports Guidelines for adapting project management processes to the current project—remember,

not every process needs to be completed on every project

Guidelines for adapting project management processes to the current project—remember,

not every process needs to be completed on every project Financial controls for purchasing, accounting codes, and procurement processes

Financial controls for purchasing, accounting codes, and procurement processes Communication requirements within your organization, such as standard forms, procedures,

and reports that you must use as a project manager in your organization

Communication requirements within your organization, such as standard forms, procedures,

and reports that you must use as a project manager in your organization Processes for project activities, such as change control, closing, communications,

financial controls, and risk control procedures

Processes for project activities, such as change control, closing, communications,

financial controls, and risk control procedures Project closing procedures for acceptance, product validation, and evaluations

Project closing procedures for acceptance, product validation, and evaluationsIdeally, your organization has a method to catalog, archive, and retrieve information

from past projects and work. The PMBOK calls this the “corporate knowledge base.”

This can be a fancy electronic data storage and retrieval system, or it might just

be a hallway closet full of past project files. Things the corporate knowledge base

should provide include the following:

Process measurement for project performance

Process measurement for project performance Project files

Project files Historical information from past projects

Historical information from past projects Issue and defect databases

Issue and defect databases Configuration management databases

Configuration management databases Financial databases

Financial databases

The corporate knowledge base is part of organizational process assets. This includes

information from past projects, organizational standards for costs and labor based

on the work in the project, central issue and defect management databases, process

measurement databases, and organizational standards.

Throughout this book, you’ll see the term “organizational process assets” used for

different processes and inputs for processes. It simply means that you’ll rely on

information that has been created to help you, the project manager, complete your

current job. Organizational process assets are templates, software, and historical

information that you can use on your current project. A template, by the way, doesn’t

always mean a shell of a document, as you might use in Microsoft Word. Templates in

project management can be past project plans, scope statements, and just about any

other document that you adapt for your current project. There is no reason to reinvent

the wheel—project management is tedious enough.

Utilizing Enterprise Environmental Factors

Enterprise environmental factors are the elements that directly influence the management

of the project, but the project manager has no direct control over the elements. For

example, your organization may have particular rules for bringing a project team member

onto your project. This rule is outside of your control, but you have to abide by

it. This rule might sometimes hinder you from zipping along in project execution,

but it also helps bring order and control to the projects within the organization.

Just as organizational process assets are inputs to many project management processes,

so, too, are enterprise environmental factors.

Here are some common enterprise environmental factors:

The organization’s structure, defined processes and rules, and the structure (functional,

matrix, projectized, or composite)

The organization’s structure, defined processes and rules, and the structure (functional,

matrix, projectized, or composite) Government regulations and your industry standards

Government regulations and your industry standards Organizational workflow, equipment, capabilities, facilities, and infrastructure

Organizational workflow, equipment, capabilities, facilities, and infrastructure Marketplace conditions

Marketplace conditions The organization’s tolerance for risk

The organization’s tolerance for risk Stakeholder risk tolerances

Stakeholder risk tolerances Political climate

Political climate Marketplace conditions

Marketplace conditions Requirements for project management (communication channels, reporting requirements,

project management information systems, and staffing)

Requirements for project management (communication channels, reporting requirements,

project management information systems, and staffing) Project management information system (PMIS), such as a software program, that helps

the project manager manage the project

Project management information system (PMIS), such as a software program, that helps

the project manager manage the projectEnterprise environmental factors are the things you’re required to do by your organization

and industry as a project manager. These are rules and policies you’re required to

follow as you manage a project. Enterprise environmental factors define boundaries,

set expectations, and provide a level of governance for the project. Although it’s

tempting to see enterprise environmental factors as a hindrance to the project, they

can also help guide the project manager through expectations.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 2.02

Defining Key General Management Skills

There is more to project management than just getting the work done. Inherent to the

process of project management are general management skills that allow the project

manager to complete the project with some level of efficiency and control. In some

respects, managing a project is similar to running a business: There are risks and

rewards, finance and accounting activities, human resource issues, time management,

stress management, and a purpose for the project to exist.

The effective project manager will have experience, or guidance, in the general management

skills we’ll discuss in this section. These general management skills are needed in

just about every project type—from architectural design to manufacturing. Other management

skills are more specialized in nature, such as OSHA conformance in a manufacturing

environment, and aren’t needed in every project.

Leading the Project Team

Project managers manage things but lead people. What’s the difference? Management

is the process of getting the results that are expected by project stakeholders. Leadership

is the ability to motivate and inspire individuals to work toward those expected results.

Ever work for a project manager who wasn’t motivating or inspiring? A good project

manager can motivate and inspire the project team to see the vision and value of the

project. The project manager as a leader can inspire the project team to find a solution

to overcome the perceived obstacles to get the work done. Motivation is a constant

process and the project manager must be able to motivate the team to move toward completion—with

passion and a profound reason to complete the work. Finally, motivation and inspiration

must be real; the project manager must have a personal relationship with the project

team to help them achieve their goals.

Leadership and management are interrelated. You won’t have effective leadership without

management, and vice versa. Know that leadership can also come from project team members,

not just from the project manager.

Communicating Project Information

Project communication can be summed up as “who needs what information and when.” Project

managers spend the bulk of their time communicating information—not doing other activities.

Therefore, they must be good communicators, promoting a clear, unambiguous exchange

of information. Communication is a two-way street; it requires a sender and a receiver.

A key part of communication is active listening. This is the process by which the receiver restates what the sender has said to clarify

and confirm the message. For example, a project team member tells the project manager

that a work package will be done in seven days. The project manager clarifies and

confirms by stating the work package will be done a week from today. This gives the

project team member the opportunity to clarify that the work package will actually

be done nine days from today because of the upcoming weekend.

There are several communication avenues:

Listening and speaking

Listening and speaking Written and oral

Written and oral Internal to the project, such as project team member to team member

Internal to the project, such as project team member to team member External to the project, such as the project manager to an external customer

External to the project, such as the project manager to an external customer Formal communications, such as reports and presentations

Formal communications, such as reports and presentations Informal communications, such as e-mails and “hallway” meetings

Informal communications, such as e-mails and “hallway” meetings Vertical communications, which follow the organizational flow chart

Vertical communications, which follow the organizational flow chart Horizontal communications, such as director to director within the organizational

flow chart

Horizontal communications, such as director to director within the organizational

flow chartWithin management communication skills are also variables and elements unique to the

flow of communication. Although we’ll discuss communications in full in Chapter 10, here are some key facts for now:

Sender-receiver models Communication requires a sender and a receiver. Within this model may be multiple

avenues to complete the flow of communication, but barriers to effective communication

may be present as well. Other variables within this model include recipient feedback,

surveys, checklists, and confirmation of the sent message.

Sender-receiver models Communication requires a sender and a receiver. Within this model may be multiple

avenues to complete the flow of communication, but barriers to effective communication

may be present as well. Other variables within this model include recipient feedback,

surveys, checklists, and confirmation of the sent message. Media selection There are multiple choices when it comes to sending a message. Which one is appropriate?

Based on the audience and the message being sent, the media should be in alignment.

In other words, an ad-hoc hallway meeting is probably not the best communication avenue

to explain a large variance in the project schedule.

Media selection There are multiple choices when it comes to sending a message. Which one is appropriate?

Based on the audience and the message being sent, the media should be in alignment.

In other words, an ad-hoc hallway meeting is probably not the best communication avenue

to explain a large variance in the project schedule. Style The tone, structure, and formality of the message being sent should be in alignment

with the audience and the content of the message.

Style The tone, structure, and formality of the message being sent should be in alignment

with the audience and the content of the message. Presentation When it comes to formal presentations, the presenter’s oral and body language,

visual aids, and handouts all influence the message being delivered.

Presentation When it comes to formal presentations, the presenter’s oral and body language,

visual aids, and handouts all influence the message being delivered. Meeting management Meetings are forms of communication. How the meeting is led, managed, and controlled

all influence the message being delivered. Agendas, minutes, and order are mandatory

for effective communications within a meeting.

Meeting management Meetings are forms of communication. How the meeting is led, managed, and controlled

all influence the message being delivered. Agendas, minutes, and order are mandatory

for effective communications within a meeting.Negotiating Project Terms and Conditions

Project managers must negotiate for the good of the project. In any project, the project

manager, the project sponsor, and the project team will have to negotiate with stakeholders,

vendors, and customers to reach a level of agreement acceptable to all parties involved

in the negotiation process. In some instances, typically in less-than-pleasant circumstances,

negotiations may have to proceed with assistance. Specifically, mediation and arbitration

are examples of assisted negotiations. Negotiation proceedings typically center on

the following:

Priorities

Priorities Technical approach

Technical approach Project scope

Project scope Schedule

Schedule Cost

Cost Changes to the project scope, schedule, or budget

Changes to the project scope, schedule, or budget Vendor terms and conditions

Vendor terms and conditions Project team member assignments and schedules

Project team member assignments and schedules Resource constraints, such as facilities, travel issues, and team members with highly

specialized skills

Resource constraints, such as facilities, travel issues, and team members with highly

specialized skills

The purpose of negotiations is to reach a fair agreement among all parties.

Active Problem Solving

Like riddles, puzzles, and cryptology? If so, you’ll love this area of project management.

Problem solving is the ability to understand the heart of a problem, look for a viable

solution, and then make a decision to implement that solution. In any project, countless

problems require viable solutions. And like any good puzzle, the solution to one portion

of the problem may create more problems elsewhere.

The premise for problem solving is problem definition. Problem definition is the ability

to discern between the cause and effect of the problem. This centers on root-cause

analysis. If a project manager treats only the symptoms of a problem rather than its

cause, the symptoms will perpetuate and continue throughout the project’s life. Root-cause

analysis looks beyond the immediate symptoms to the cause of the symptoms—which then

affords opportunities for solutions.

Completing the PMP exam is an example of having problem-solving skills. Even though

you may argue that things described in this book don’t work this way in your environment,

know that the exam is not based on your environment. Learn the Project Management

Institute (PMI) method for passing the exam and allow that to influence your “real-world”

implementations.

Once the root of a problem has been identified, the project manager must make a decision

to address the problem effectively. Solutions can be presented from vendors, the project

team, the project manager, or various stakeholders. A viable solution focuses on more

than just the problem. It looks at the cause and effect of the solution itself. In

addition, a timely decision is needed, or the window of opportunity may pass and then

a new decision will be needed to address the problem. As in most cases, the worst

thing you can do is nothing.

Influencing the Organization

Project management is about getting things done. Every organization is different in

its policies, modes of operations, and underlying culture. There are political alliances,

differing motivations, conflicting interests, and power struggles within every organization.

So where does project management fit into this rowdy scheme? Right smack in the middle.

A project manager must understand all of the unspoken influences at work within an

organization—as well as the formal channels that exist. A balance between the implied

and the explicit will allow the project manager to take the project from launch to

completion. We all reference politics in organizations with disdain. However, politics

aren’t always a bad thing. Politics can be used as leverage to align and direct people

to accomplish activities—with motivation and purpose.

These exam questions are shallow. Don’t read too much into the questions as far as

political aspirations and influences go. Take each question at face value and assume

all of the information given in the question is correct.

Managing Social, Economic, and Environmental Project Influences

Social, economic, and environmental influences can cause a project to falter, stall,

or fail completely. Awareness of potential influences outside of traditional management

practices will help complete the project. The acknowledgement of such influences,

from internal or external sources, allows the project manager and the project team

to plan how to react to these influences in order for the project to succeed.

For example, consider a construction project that may reduce traffic flow to one lane

over a bridge. Obviously, stakeholders in this instance are the commuters who travel

over the bridge. Social influences are the people who are frustrated by the construction

project, the people who live in the vicinity of the project, and even individuals

or groups that believe their need for road repairs is more pressing than the need

to repair the bridge. These issues must all be addressed, on some level, for the project

team to complete the project work quickly and efficiently.

The economic conditions in any organization are always present. The cost of a project

must be weighed against the project’s benefits and perceived worth. Projects may succumb

to budget cuts, project priority, or their own failure based on the performance to

date. Economic factors inside the organization may also hinder a project from moving

forward. In other words, if the company sponsoring the project is not making money,

projects may get axed in an effort to curb costs.

Finally, environmental influence on, and created by, the project must be considered.

Let’s revisit the construction project on the bridge. The project must consider the

river below the bridge and how construction may affect the water and wildlife. Consideration

must be given not only to short-term effects that arise during the bridge’s construction

but also to long-term effects that the construction may have on the environment.

In most projects, the social, economic, and environmental concerns must be evaluated,

documented, and addressed within the project plan. Project managers can’t have a come-what-may

approach to these issues and expect to be successful.

Dealing with Standards and Regulations

Standards and regulations within any industry can affect a project’s success. But

what’s the difference between a standard and a regulation? Standards are accepted

practices that are not necessarily mandatory, while regulations are rules that must

be followed—otherwise, fines, penalties, or even criminal charges may result.

For example, within the information technology industry are standard sizes for CDs,

DVDs, and USB storage drives. Manufacturers generally map to these sizes for usability

purposes. However, manufacturers can, and have, created other media that are slightly

different in size and function from the standard. Consider the USB drives that companies

give away at trade shows and all of the different shapes and sizes of these drives.

Such products aren’t exactly standard regarding format, but they don’t break any regulations

either. After a time, though, standards can indeed become de facto regulations. They

may begin as guidelines and then, due to marketplace circumstances, grow into an informal

regulation.

An example of a regulation is a set rule or law. For example, in the food packaging

industry, particular regulations relate to the packaging and delivery of food items.

Violations of the regulations will result in fines or even more severe punishment.

Regulations are more than suggestions—they are project requirements.

Every industry has some standards and regulations. Knowing which ones affect your

project before you begin your work will not only help the project to unfold smoothly,

but will allow for effective risk analysis. In some instances, the requirements of

regulations can afford the project manager additional time and monies to complete

a project.

Every industry has some standards and regulations. Knowing which ones affect your

project before you begin your work will not only help the project to unfold smoothly,

but will allow for effective risk analysis. In some instances, the requirements of

regulations can afford the project manager additional time and monies to complete

a project.Considering International Influences

If a project spans the globe, how will the project manager effectively manage and

lead the project team? How will teams in Paris communicate with teams in Sydney? What

about the language barriers, time zone differences, currency differences, regulations,

laws, and social influences? All of these concerns must be considered early in the

project. Tools can include teleconferences, travel, face-to-face meetings, team leaders,

and subprojects.

As companies and projects span the globe to offer goods and services, the completion

of those projects will rely more and more on individuals from varying educational

backgrounds, social influences, and values. The project manager must create a plan

that takes these issues into account.

Cultural Influences

Project plans must deal with many cultural influences: geographical, political, organizational,

even relationships between individual team members. Projects in Dallas, Texas, have

different cultural influences than projects taking place in Dublin, Ireland. Culture

consists of the values, beliefs, political ties, religion, art, aspirations, and purpose

of being. A project manager must take into consideration these various cultural influences

and how they may affect the project’s completion, schedule, scope, and cost.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 2.03

Meeting the Project Stakeholders

Stakeholders are those fine folks and organizations who are actively involved in the

project or who will be affected by its outcome—in other words, people, groups, businesses,

customers, and communities that have a vested interest in the project.

Stakeholders may like, love, or hate your project. Consider an organization that is

hosting a project to move all their workers to a common word-processing application.

Everyone within this organization must now use the same word-processing application.

Your job, as the project manager, is to see that this happens.

Within your project, you’ll find three types of stakeholders. Positive stakeholders

are in love with your project and the benefits it will bring. They are advocates of

your project and want you to succeed. Negative stakeholders don’t want your project

to succeed and they are opposed to the changes the project will create. Neutral stakeholders,

such as the people in the purchasing department, are neither for nor against your

project, but they still must interact with you and your project. You’ll have to manage

all of these stakeholders to get your project to a successful closure.

In high-profile projects, where stakeholders will be in conflict over the project

purpose, deliverables, cost, and schedule, the project manager may want to use the

Delphi Technique to gain anonymous consensus among stakeholders. The Delphi Technique

allows stakeholders to offer opinions and input without fear of retribution from management.

More on this in Chapter 11.

In high-profile projects, where stakeholders will be in conflict over the project

purpose, deliverables, cost, and schedule, the project manager may want to use the

Delphi Technique to gain anonymous consensus among stakeholders. The Delphi Technique

allows stakeholders to offer opinions and input without fear of retribution from management.

More on this in Chapter 11.

INSIDE THE EXAM

Projects don’t last forever. Though projects may sometimes seem to last forever, they

fortunately do not. Operations, however, go on and on. Projects pass through logical

phases to reach their completion, while operations may be influenced, or even created,

by the outcome of a project.

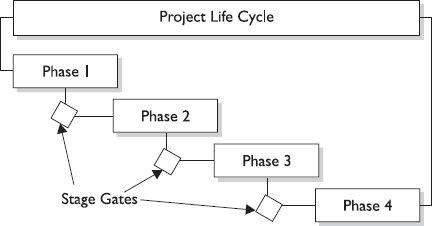

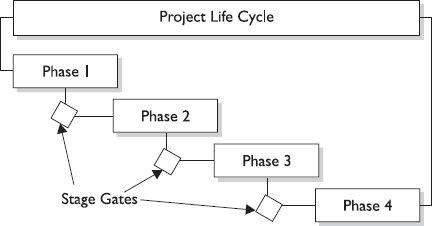

The phases within a project create deliverables. The deliverables typically allow

the project to move forward to the next phase—or allow the project to be terminated

based on the quality, outcome, or condition of the phase deliverable. Some projects

may use stage gates. Recall that stage gates allow a project to continue (after performance

and deliverable review) against a set of predefined metrics. Other projects may use

kill points. Kill points, like phase gates, are preset times placed in the project

when it may, based on conditions and discovery within the phase, be “killed.”

The project life cycle is different from the project management life cycle. The project

management life cycle comprises the five project management processes (initiation,

planning, execution, control, and closure). The project life cycle, meanwhile, comprises

the logical phases within the project itself.

The project life cycle is affected by the project stakeholders. Project stakeholders

have a vested interest in the outcome of the project. Stakeholders include the project

manager, project team, management, customers, communities, and anyone affected by

the project outcome. Project managers should scan the project outcome to identify

all of the stakeholders and collect and record their expectations, concerns, and input

regarding the project processes.

The project manager’s power is relative to the organization structure he is operating

within. A project manager in a functional organization will have relatively low authority.

A project manager in a matrix environment can have low, balanced, or high authority

over the project. A project manager in a projectized organization, on the other hand,

will have a high level of authority on the project. Essentially, the project manager’s

authority is typically inverse to the authority of the functional manager.

Stakeholders, especially negative stakeholders, may try to influence the project itself.

This can be attempted in many ways, such as through the following:

Political capital leveraged to change the project deliverable

Political capital leveraged to change the project deliverable Change requests to alter the project deliverable

Change requests to alter the project deliverable Scope addendums to add to the project deliverable

Scope addendums to add to the project deliverable Adding overhead, including multiple reviews to slow progress, and even attempting

to cut resources

Adding overhead, including multiple reviews to slow progress, and even attempting

to cut resources Sabotage, through physical acts or rumors, gossip, and negative influence

Sabotage, through physical acts or rumors, gossip, and negative influenceYour role as the project manager is to identify, align, and ascertain stakeholders

and their expectations of the project. Stakeholder identification is not always as

clear-cut as in the preceding example. Because stakeholders are identified as people

that are affected by the outcome of your project, external customers may be stakeholders

in your project, too.

Consider a company that is implementing a frequent customer discount project. External

customers will use a card that tracks their purchases and gives them discounts on

certain items they may buy. Is the customer in this instance a stakeholder? What if

the customer doesn’t want to use the card? Is she still a stakeholder?

Mystery Stakeholders

Stakeholders can go by many different names: internal and external customers, project

owners, financiers, contractors, family members, government regulatory agencies, communities,

cities, citizens, and more. The classification of stakeholders into categories is

not as important as realizing and understanding their concerns and expectations. The

identification and classification of stakeholders, however, does allow the project

manager to deliver effective and timely communications to the appropriate stakeholders.

Project managers must scan the project for hidden stakeholders. The project manager

should investigate all parties affected by the project to identify all of the stakeholders—not

just the obvious ones. Hidden stakeholders can influence the outcome of the project.

They can also add cost, scheduling requirements, or risk to a project.

Key Project Stakeholders

Beyond those stakeholders affected by the project deliverable, there are key stakeholders

on every project. Let’s meet them.

Project manager The project manager is the person—ahem, you—who is accountable for managing the

project. She guides the team through the project phases to completion.

Project manager The project manager is the person—ahem, you—who is accountable for managing the

project. She guides the team through the project phases to completion. Program manager The program manager coordinates the efforts of multiple projects working together

in the program. Programs are made up of projects, so it makes sense that the program

manager would be a stakeholder in each of the projects within the program, right?

Program manager The program manager coordinates the efforts of multiple projects working together

in the program. Programs are made up of projects, so it makes sense that the program

manager would be a stakeholder in each of the projects within the program, right? Portfolio management review board Organizations have only so much capital to invest in projects. The portfolio management

review board is a collection of the decision-makers, usually executives, who will

review proposed projects and programs for their value and return on investment for

the organization.

Portfolio management review board Organizations have only so much capital to invest in projects. The portfolio management

review board is a collection of the decision-makers, usually executives, who will

review proposed projects and programs for their value and return on investment for

the organization. Functional managers Most organizations are chopped up by functions or disciplines, such as information

technology, sales, marketing, and finance. Functional managers are the managers of

the permanent staff in each of these functions. Project managers and functional managers

interact on project decisions that affect functions, projects, and operations.

Functional managers Most organizations are chopped up by functions or disciplines, such as information

technology, sales, marketing, and finance. Functional managers are the managers of

the permanent staff in each of these functions. Project managers and functional managers

interact on project decisions that affect functions, projects, and operations. Project customer The customer is the person or group that will use the project deliverable. In some

instances, a project may have many different customers. Consider a company that creates

software for the financial industry. The company creates the software. Resellers sell

the software. End users utilize the software. Within each of these groups are different

stakeholders that have varying objectives for the software and how they’ll interact

with the organization and its project teams.

Project customer The customer is the person or group that will use the project deliverable. In some

instances, a project may have many different customers. Consider a company that creates

software for the financial industry. The company creates the software. Resellers sell

the software. End users utilize the software. Within each of these groups are different

stakeholders that have varying objectives for the software and how they’ll interact

with the organization and its project teams. Operations managers The core business of an organization is supported primarily by operations management.

Operations managers deal directly with the income-generating products or services

the company provides. Projects often affect the core business, so these managers are

stakeholders in the project. Project deliverables that affect the core business usually

include an operational transfer plan that defines support, training, and maintenance

on the project deliverables.

Operations managers The core business of an organization is supported primarily by operations management.

Operations managers deal directly with the income-generating products or services

the company provides. Projects often affect the core business, so these managers are

stakeholders in the project. Project deliverables that affect the core business usually

include an operational transfer plan that defines support, training, and maintenance

on the project deliverables. Organizational groups The departments and groups within an organization that are affected by the project

or can affect a project are stakeholders. For example, a project to upgrade the sales

software directly affects the sales department, but the manufacturing department can

influence how the software is configured, so manufacturing is also a stakeholder in

the project.

Organizational groups The departments and groups within an organization that are affected by the project

or can affect a project are stakeholders. For example, a project to upgrade the sales

software directly affects the sales department, but the manufacturing department can

influence how the software is configured, so manufacturing is also a stakeholder in

the project. Project team The project team is the collection of individuals who will, hopefully, work together

to ensure the success of the project. The project manager works with the project team

to guide, schedule, and oversee the project work. The project team completes the project

work.

Project team The project team is the collection of individuals who will, hopefully, work together

to ensure the success of the project. The project manager works with the project team

to guide, schedule, and oversee the project work. The project team completes the project

work. Project management team These are the folks on the project team who are involved with managing the project.

Project management team These are the folks on the project team who are involved with managing the project. Project sponsor The sponsor authorizes the project. This person or group ensures that the project

manager has the necessary resources, including monies, to get the work done. The project

sponsor is someone within the performing organization who has the power to authorize

and sanction the project work and is ultimately accountable for the project’s success.

Project sponsor The sponsor authorizes the project. This person or group ensures that the project

manager has the necessary resources, including monies, to get the work done. The project

sponsor is someone within the performing organization who has the power to authorize

and sanction the project work and is ultimately accountable for the project’s success. Sellers and business partners Organizations often rely on vendors, contractors, and business partners to help

projects achieve their objectives. These business partners can affect the project’s

success, and they are considered stakeholders in the project.

Sellers and business partners Organizations often rely on vendors, contractors, and business partners to help

projects achieve their objectives. These business partners can affect the project’s

success, and they are considered stakeholders in the project. The project management office If a PMO exists for the organization, it’s considered a stakeholder of the project

because it supports the project managers and is responsible for the project’s success.

PMOs typically provide administrative support, training for the project managers,

resource management for the project team and project staffing, and centralized communication.

The project management office If a PMO exists for the organization, it’s considered a stakeholder of the project

because it supports the project managers and is responsible for the project’s success.

PMOs typically provide administrative support, training for the project managers,

resource management for the project team and project staffing, and centralized communication. You’ll need to know loads of terms and special vocabulary for this exam. Don’t let

the terms scare you—you can do this! Do yourself a favor and grab a stack of index

cards. As you go through this fascinating material, jot down every term that’s new

or interesting to you. Once you’ve read the chapter, you can create some fast flashcards.

If you start now, you’ll have a nice stack of cards by the time you reach the end

of the book. Keep going—we have confidence in you.

You’ll need to know loads of terms and special vocabulary for this exam. Don’t let

the terms scare you—you can do this! Do yourself a favor and grab a stack of index

cards. As you go through this fascinating material, jot down every term that’s new

or interesting to you. Once you’ve read the chapter, you can create some fast flashcards.

If you start now, you’ll have a nice stack of cards by the time you reach the end

of the book. Keep going—we have confidence in you.

When it comes to stakeholder expectations, nothing beats documentation! Get stakeholder

expectations in writing as soon as possible.

Managing Stakeholder Expectations

Ever had an experience that didn’t live up to your expectations? Not much fun, is

it? With project management and a large number of stakeholders, it’s easy to see how

some stakeholders’ expectations won’t be realistic due to cost, schedule, or feasibility.

A project manager must find solutions to create win-win scenarios between stakeholders.

Managing Expectations in Action

Consider a project to implement new customer relationship management software. In

this project, there are three primary stakeholders with differing expectations:

The sales director wants a technical solution that will ensure fast output of order

placements, proposals, and customer contact information—regardless of the cost.

The sales director wants a technical solution that will ensure fast output of order

placements, proposals, and customer contact information—regardless of the cost. The marketing director wants a technical solution that can track call volume, customer

sales history, and trends with the least cost to implement.

The marketing director wants a technical solution that can track call volume, customer

sales history, and trends with the least cost to implement. The IT director wants a technical solution that will fan into the existing network

topology and have considerable ease of use and reliability—without costing more than

20 percent of his budget for ongoing support.

The IT director wants a technical solution that will fan into the existing network

topology and have considerable ease of use and reliability—without costing more than

20 percent of his budget for ongoing support.In this scenario, the project manager will have to work with each of the stakeholders

to determine a winning solution that satisfies all of the project requirements while

appeasing the stakeholders’ demands. Specifically, the solution for the conflict of

stakeholders is to satisfy the needs of the customer first. Customer needs, or the

business need of why the project was initiated, should guide the project through the

project life cycle. Once the project scope is aligned with the customer’s needs, the

project manager may work to satisfy the differing expectations of the stakeholders.

Enforcing Project Governance

Project governance is a set of rules to ensure that the project manager, the project

sponsor, the project team, and the key stakeholders all follow defined practices for

the project success. It is the assurance that the project is aligned to the organization’s

strategy and business objectives. Project governance creates a model or framework

for all projects within an organization to follow and sets expectations for how projects

should operate for all project stakeholders. Project governance includes the following

elements:

Documented policies for the project’s processes and procedures

Documented policies for the project’s processes and procedures Definition of project success

Definition of project success Project chart of roles and responsibilities

Project chart of roles and responsibilities Communication expectations and definitions

Communication expectations and definitions Definition of decision-making process and escalation process

Definition of decision-making process and escalation process Project life cycle approach

Project life cycle approach Stage gates and reviews for project phase completions

Stage gates and reviews for project phase completions Change control processes for scope, schedule, costs, and contracts

Change control processes for scope, schedule, costs, and contractsProject governance is created at a level in the organization that’s usually above

the project manager. The PMO—or, if the project is part of a program, the program

manager—will define the project governance. The governance really creates the project

framework—how the project is to operate within the organization. The project governance

should be clearly communicated to the project team and other stakeholders so that

everyone understands the boundaries, options, and procedures the project manager will

follow and enforce within the project. Like most things in a project, communication

is crucial.

The project manager, the project sponsor, the organization’s management, and, depending

on the project, other stakeholders all want the project to be successful. Success,

however, is an esoteric concept that means different things to different people. Success

for the project should be defined as early as possible in the project timeline. Success

is often based on the constraints of schedule, costs, quality, resources, risks, and

the project scope. The project manager is the person responsible for determining the

boundaries of success. The baselines for project scope, schedule, and costs will be

defined and documented during project planning.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 2.04

Working with the Project Team

Projects are rarely a solo act, although they could be. In most projects, you, the

project manager, will rely on the expertise, labor, and input from your project team

members. The project team may include people from all parts of your organization and

even people that are outside of your organization—such as vendors and contracted help.

As the project manager, you’ll work to welcome the project team members, coach them

on the project rules and governance, and lead them through the project work they’ll

be executing according to the project plan. Early in the project, even during the

project kickoff meeting, the project manager must set expectations for the project

team.

Recall that the organizational structure will directly affect how you manage the project

team and how much the project team will interact with your project. For example, in

a functional structure, your project team may look to the project manager as a coordinator

of the project and someone with not much authority. Over in a strong matrix structure,

however, the project team may see the project manager as the person with the authority,

the insight, and the decision-making power for the project. In any structure, the

project manager must establish the rules and expectations of the project, provide

leadership, and serve as a hub for project communications.

The project manager communicates the project ground rules for the entire project team.

Once ground rules have been created it is the responsibility of the project team to

enforce the rules.

Identifying Project Team Roles

Although most of the project team members are likely working on project execution,

some of your project team members may serve in a more consultative role for decisions.

The PMBOK Guide will often refer to this consultative role as “expert judgment.” A role describes

the actions a person will take. For example, a software development project may have

roles such as developer, designer, tester, and database administrator. Roles are generic

descriptions and usually don’t identify specific people in the roles, such as Pat

the Designer—instead, it’s just designer. For your PMP examination you’ll need to

know some typical project team roles:

Project manager The person who leads, directs, and manages the project initiation, planning, execution,

monitoring and controlling, and closing of the project.

Project manager The person who leads, directs, and manages the project initiation, planning, execution,

monitoring and controlling, and closing of the project. Project management staff People who perform some of the project management activities such as scheduling,

managing risks, quality assurance, and procurement. A PMO may serve as this role.

Project management staff People who perform some of the project management activities such as scheduling,

managing risks, quality assurance, and procurement. A PMO may serve as this role. Supporting experts Often people on the project team will help plan the project work in addition to

executing the project work. Supporting experts are the individuals who advise the

project manager how the work should occur in the project and help build the project

plan and/or perform the project execution.

Supporting experts Often people on the project team will help plan the project work in addition to

executing the project work. Supporting experts are the individuals who advise the

project manager how the work should occur in the project and help build the project

plan and/or perform the project execution. Users and customers The recipients of the project deliverables contribute to the project requirements,

verify the project scope, and may serve as liaisons for groups of stakeholders they

represent.

Users and customers The recipients of the project deliverables contribute to the project requirements,

verify the project scope, and may serve as liaisons for groups of stakeholders they

represent. Sellers and business partners Sellers provide the resources and materials a project needs to be successful. In

some projects, the sellers may be completing a significant portion of the project

work, so the project manager considers the seller part of the project team. Business

partners are the entities that provide contracted help, such as experts, to work as

part of the project team to ensure the project’s success.

Sellers and business partners Sellers provide the resources and materials a project needs to be successful. In

some projects, the sellers may be completing a significant portion of the project

work, so the project manager considers the seller part of the project team. Business

partners are the entities that provide contracted help, such as experts, to work as

part of the project team to ensure the project’s success.Building the Project Team

The organizational structure will determine how much authority the project manager

has over the project team, but it may also determine who’ll be on the project team

and how much time they’ll spend on the team. In other words, you might be in charge

and leading the project team, but you may not get to determine who’ll be part of the

team and when they’ll do the work you need them to do. The culture of an organization

also affects the perceived power the project manager has over the project team and

the respect they garner. Of course, there’s also an expectation for the project manager

to be likeable, professional, fair, and void of politics and favorites.

In projectized organizations and sometimes on larger projects, your project team may

be considered a dedicated project team. A dedicated project team is on your project full time. Dedicated project

teams are often, but not always, physically located in one geographical place for

ease of communications and team building, and to provide a concerted effort toward

completing the project work. This is the simplest project structure, because there’s

no competition for resources, no scheduling conflicts, and communication demands are

relatively low compared to other organizational structures.

In matrix and functional structures, the project team may be working on your project

on a part-time basis. The project team works on your project tasks, but they also

have their day-to-day operations and work on other projects to consider as well. Although

this structure isn’t ideal for the project manager, it’s not uncommon in organizations.

One of the advantages for the organization for a part-time project team is that the

team can perform multiple assignments for the company. The project team can work on

the core operations and also work on special work in the form of your project.

A primary disadvantage for this approach, however, is that team resources are spread

thin among your project assignments, their operational work, and assignments on other

projects. Project team members may not have the time, motivation, or energy to switch

efficiently between all of their tasks, which can cause delays in the project schedule

and an increase in communications, quality issues, and other problems within the project.

If an organization takes this part-time approach to the project team, there must be

reasonable expectations for the project schedule and communication demands for the

project manager.

In some instances, project managers may find themselves working in a partnership arrangement

or teaming agreement with another company. A partnership project team may be the result

of a contracted team comprising professionals from several different organizations

who work on the project. In a partnership structure, generally one company takes the

lead and provides the project manager and project management direction, while the

other companies serve as support and project team member roles. In this project team

structure, it’s mandatory for the project manager to communicate clearly the project

ground rules, communication expectations, and performance requirements for the entire

project team.

Virtual project teams aren’t collocated and they use technology such as web meeting

and collaboration software to communicate and work together. Virtual teams are project

teams that may not work side-by-side in the same physical space, but they do communicate

regularly and may even work together via web technologies. Although virtual teams

are a great approach to make use of talented resources around the globe, they do present

some drawbacks. The project manager must consider technology challenges, time zone

differences, language barriers, customs, holidays, and other factors that may hinder

the virtual project team from excelling.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 2.05

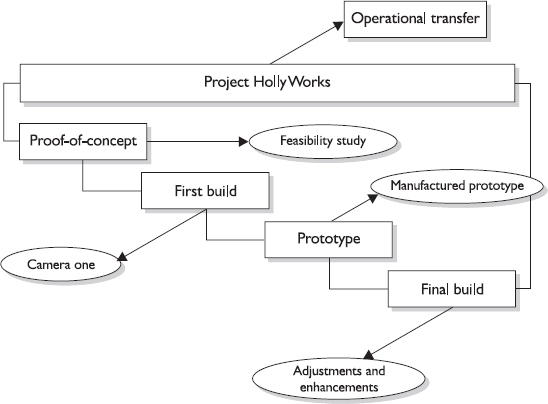

Revving Through Project Life Cycles

Consider any project, and you’ll also have to consider any phases within the project. Construction projects have definite phases. IT projects have

definite phases. Marketing, sales, and internal projects all have definite phases.

Projects—all projects—comprise phases. Phases make up the project life cycle, and

they are unique to each project. Furthermore, organizations, project managers, and

even third-party project frameworks (such as Agile or Scrum) can define phases within

a project life cycle. Just know this: The sum of a project’s phases equates to the

project’s life cycle.

In regard to the PMP exam, it’s rather tough for the PMI to ask questions about specific

project life cycles. Why? Because every organization may identify different phases

within all the different projects that exist. Bob may come from a construction background

and Susan from IT, each one being familiar with totally different disciplines and

totally different life cycles within their projects. However, all PMP candidates should

recognize that every project has a life cycle—and all life cycles comprise phases.

Phases are unique to each project. Phases are not the same as initiating, planning,

executing, monitoring and controlling, and closing. These are the process groups and

are universal to all projects.

Because every project life cycle is made up of phases, it’s safe to assume that each

phase has a specific type of work that allows the project to move toward the next

phase in the project. When we talk in high-level terms about a project, we might say

that a project is launched, planned, executed, and finally closed, but it’s the type

of work, the activities the project team is completing, that more clearly defines

the project phases. In a simple construction example, this is easy to see:

Phase 1: Planning and pre-build

Phase 1: Planning and pre-build Phase 2: Permits and filings

Phase 2: Permits and filings Phase 3: Prep and excavation

Phase 3: Prep and excavation Phase 4: Basement and foundation

Phase 4: Basement and foundation Phase 5: Framing

Phase 5: Framing Phase 6: Interior

Phase 6: Interior Phase 7: Exterior

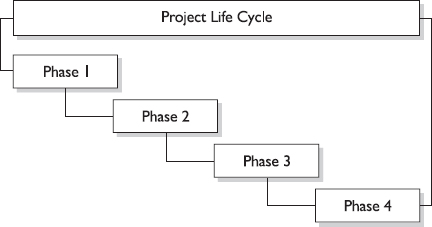

Phase 7: ExteriorTypically, one phase is completed before the next phase begins; this relationship

between phases is called a “sequential relationship.” The phases follow a sequence

to reach the project completion—one phase after another. Sometimes project managers

allow phases to overlap because of time constraints, cost savings, and smarter work.

When time’s an issue and a project manager allows one phase to begin before the last

phase is completed, it’s called an “overlapping relationship” because the phases overlap.

You might also know this approach as “fast tracking.” Fast tracking, as handy as it

is, increases the risk within a project.

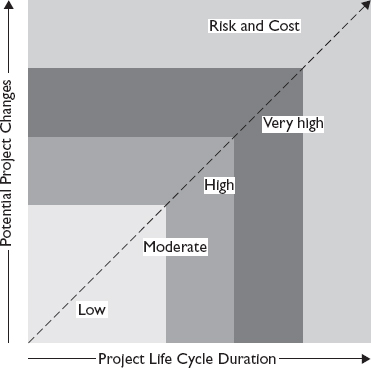

A project is an uncertain business—the larger the project, the more uncertainty. It’s

for this reason, among others, that projects are broken down into smaller, more manageable

phases. A project phase allows a project manager to see the project as a whole and

yet still focus on completing the project one phase at a time. You can also think

of the financial distribution and the effort required in the form of project life

cycles. Generally, labor and expenses are lowest at the start of the project, because

you’re planning and preparing for the work. You’ll spend the bulk of the project’s

budget on labor, materials, and resources during project execution, and then costs

will taper off as your project eases into its closing.

Working with Project Life Cycles

Projects are like snowflakes: No two are alike. Sure, sure, some may be similar, but

when you get down to it, each project has its own unique attributes, activities, and

requirements from stakeholders. One attribute that typically varies from project to

project is the project life cycle. As the name implies, the project life cycle determines

not only the start of the project, but also when the project should be completed.

All that stuff packed in between starting and ending? Those are the different phases

of the project.

In other words, the launch, a series of phases, and project completion make up the

project life cycle. Each project will have similar project management activities,