|

7

Introducing Project Cost Management

|

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVES

Projects cost money. Ever worked with a client who had a huge vision for a project

but little capital to invest in that vision? Or worked with a client who gasped when

you revealed how much it would cost to complete her desired scope of work? Or have

you been fortunate with customers who accepted the costs for the project at face value,

made certain that funds were available, and sent you on your way to complete the work?

As a general rule, management and customers are always concerned with how much a project

is going to cost in relation to how much a project is going to earn.

Most likely, there is more need for negotiating, questioning, and evaluating for larger

projects than for smaller ones. The relationship between the project cost and the

project scope should be direct: You get what you pay for. Think it’s possible to buy

a mansion at ranch home prices? Not likely. Think it’s possible to run a worldwide

marketing campaign at the cost of a postcard mailer? Not likely. A realistic expectation

of what a project will cost will give great weight to the project’s scope.

As the business need undergoes analysis, progressive elaboration and estimates are

completed based on varying levels of detail, and eventually the cost of the project

emerges. Often, however, predicted costs and actual costs vary. Poor planning, skewed

assumptions, and overly optimistic estimates all contribute to this. A successful

project manager must be able to plan, predict, budget, and control the costs of a

project.

Costs associated with projects are not just the costs of goods procured to complete

the project. The cost of the labor may be one of the biggest expenses of a project.

The project manager must rely on time estimates to predict the cost of the labor to

complete the project work. In addition, the cost of the equipment and materials needed

to complete the project work must be factored into the project expenses. This chapter

examines the management of project costs, how to predict them, account for them, and

then, with plan in hand, to control them. We’ll examine exactly how costs are planned

for and taken into consideration by the performing organization and how the size of

the project affects the cost estimating process.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.01

Planning the Project Costs

You need a plan on how you’ll manage the costs of the project. This direct-forward

cost management process is part of the project’s planning process group and defines

how you, the project manager, will manage the costs of the project. Like most of the

subsidiary project management plans, this plan directs the other processes in the

process group, while not actually doing the processes. It serves as a guidebook for

how the process groups should operate within your organization.

If you’re thinking that this cost management plan could be standardized for your organization,

you’re on the right track. Most organizations could create a standard project cost

management plan that serves as a template for all projects. You’d then adapt that

template to all future projects. That’s something important to remember for your PMI:

you don’t have to start from scratch when creating a subsidiary plan, cost management

plan, or others; just take what’s been created in the past and adapt it to the present.

That’s part of utilizing your organizational process assets to make your life easier,

but it also keeps the projects consistent by using what has worked in the past.

You might be wondering whether you need to create a cost management plan for every

project that you’re managing. Let me answer that for you: No, you don’t. Remember

that these processes are not required, but available. You might have a small project,

a project that’s based on previous work, or project for which all of the funds are

controlled and managed by functional management. There’s no need, probably, to create

an in-depth cost management plan in these instances.

You might be wondering whether you need to create a cost management plan for every

project that you’re managing. Let me answer that for you: No, you don’t. Remember

that these processes are not required, but available. You might have a small project,

a project that’s based on previous work, or project for which all of the funds are

controlled and managed by functional management. There’s no need, probably, to create

an in-depth cost management plan in these instances.Considering the Cost Planning Inputs

If you’re tasked with creating the cost management plan, you’ll need several components

to help you do the planning. Bear in mind that this is a planning process, so you

may be returning to this process many times throughout the project. Chances are you

want to have in-depth information for the entire project when you start planning costs,

so you’ll have to revisit the process to complete the planning. Yes, that can be a

pain, but the cyclic nature of project management planning helps you create more accurate

project plans and provide better insight and control to the project’s cost performance.

Here are the four inputs you’ll use for cost management planning:

Project charter The project charter provides a high-level summary budget that can help guide the

cost planning process.

Project charter The project charter provides a high-level summary budget that can help guide the

cost planning process. Project management plan In particular, you’ll need the scope baseline and schedule baseline, and you’ll

need to reference the project plan for other information such as procurement, scope,

and risk.

Project management plan In particular, you’ll need the scope baseline and schedule baseline, and you’ll

need to reference the project plan for other information such as procurement, scope,

and risk. Enterprise environmental factors Your organization may have rules and structure that affect how you manage costs.

Enterprise environmental factors also includes things like the market conditions,

exchange rates for international projects, and resource cost rates.

Enterprise environmental factors Your organization may have rules and structure that affect how you manage costs.

Enterprise environmental factors also includes things like the market conditions,

exchange rates for international projects, and resource cost rates. Organizational process assets Historical information, templates, financial controls, and formal and informal

cost management policies can also serve as an input to cost management planning.

Organizational process assets Historical information, templates, financial controls, and formal and informal

cost management policies can also serve as an input to cost management planning.Creating the Cost Management Plan

After considering expert judgment, undergoing analysis, and attending lots of meetings,

you and the project team will create the cost management plan. This project management

process is part of the project planning process group. The cost management plan defines

how the project costs will be estimated, how the budget will be created, and how you’ll

control the costs within the project. The plan also defines any analytical tools you’ll

use for performance of the project costs, such as earned value management (EVM).

The cost management plan accomplishes many things for the project manager, but chief

among them is that it defines how costs will be planned, managed, and controlled.

Here are the contents of the cost management plan you’ll create:

Units of measure Currency, staffing time, quantity metrics, and resource utilization costs

Units of measure Currency, staffing time, quantity metrics, and resource utilization costs Level of precision How precise your measurements need to be: for example, you may be required to list

costs down to two decimal places, or you may round cents to the nearest dollar

Level of precision How precise your measurements need to be: for example, you may be required to list

costs down to two decimal places, or you may round cents to the nearest dollar Level of accuracy The acceptable range of variance for project costs, such as +/− 10 percent or a

dollar amount

Level of accuracy The acceptable range of variance for project costs, such as +/− 10 percent or a

dollar amount Control thresholds The amount of variance that is allowed before an action must be taken, such as

a variance report or predefined cuts in the project scope to maintain overall costs

Control thresholds The amount of variance that is allowed before an action must be taken, such as

a variance report or predefined cuts in the project scope to maintain overall costs Rules of performance measurement The method you’ll use to measure project performance; for your PMP examination

you’ll want to reference earned value management later in this chapter

Rules of performance measurement The method you’ll use to measure project performance; for your PMP examination

you’ll want to reference earned value management later in this chapter Organizational procedure links How the project’s costs will be linked to the deliverables in the WBS; the mid-level

components of the WBS that have a dollar amount associated with the deliverables are

called the control account

Organizational procedure links How the project’s costs will be linked to the deliverables in the WBS; the mid-level

components of the WBS that have a dollar amount associated with the deliverables are

called the control account Reporting formats The expected modality for financial reports and communication

Reporting formats The expected modality for financial reports and communication Process descriptions The definition of the cost management processes selected and how they’ll be executed

and controlled throughout the project

Process descriptions The definition of the cost management processes selected and how they’ll be executed

and controlled throughout the project Additional planning details Funding information for the project, cash flow expectations, fluctuations in currency

exchanges, inflation, and overall cost recording

Additional planning details Funding information for the project, cash flow expectations, fluctuations in currency

exchanges, inflation, and overall cost recordingCERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.02

Estimating the Project Costs

Cost estimating is the process of calculating the costs of the identified resources

required to complete the project work. The person or group doing the estimating must

consider the possible fluctuations, conditions, and other causes of variances that

could affect the total cost of the estimate.

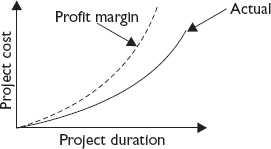

There is a distinct difference between cost estimating and pricing. A cost estimate

is the cost of the resources required to complete the project work. Pricing, however,

includes a profit margin. In other words, a company performing projects for other

organizations may do a cost estimate to see how much the project is going to cost

to complete. Then, with this cost information, they’ll factor a profit into the project

work, as shown next.

More and more companies are requiring that the project manager calculate the project

costs and then factor the ROI and other benefit models into the project product. The

goal is to see the value of the project once its deliverables are in operation.

More and more companies are requiring that the project manager calculate the project

costs and then factor the ROI and other benefit models into the project product. The

goal is to see the value of the project once its deliverables are in operation.Considering the Cost Estimating Inputs

Cost estimating relies on several project components from the initiation and planning

process groups. This process also relies on enterprise environmental factors, the

processes and procedures unique to your organization, and the organizational process

assets, such as historical information and forms and templates.

Referencing the Cost Management Plan

The primary input to creating the cost estimates is the cost management plan. Recall

that this plan defines the acceptable approach for cost estimating in your organization

and for the project. The cost management plan is based on your company’s enterprise

environmental factors—specifically the rules and procedures for how you may estimate

costs. If you’re doing a project that’s internal to your company, you may have a looser

approach to cost estimating than if you’re doing a project for a client of your company.

The project for your client has a profit margin and cash inflows, while the internal

project, while still important, is funded by existing funds rather than incoming funds.

Referencing the Human Resource Plan

The estimator must know how much each resource costs, and the human resource plan

may include this information, depending on the organizational policies, application

area, and the type of project being completed. The cost should be in some unit of

time or measure—such as cost per hour, cost per metric ton, or cost per use. If the

rates of the resources are not known, the rates themselves may also have to be estimated.

Of course, skewed rates on the estimates will result in a skewed estimate for the

project. There are four categories of cost:

Direct costs These costs are attributed directly to the project work and cannot be shared among

projects (airfare, hotels, long distance phone charges, and so on).

Direct costs These costs are attributed directly to the project work and cannot be shared among

projects (airfare, hotels, long distance phone charges, and so on). Indirect costs These costs are representative of more than one project (utilities for the performing

organization, access to a training room, project management software license, and

so on).

Indirect costs These costs are representative of more than one project (utilities for the performing

organization, access to a training room, project management software license, and

so on). Variable costs These costs vary, depending on the conditions applied in the project (the number

of meeting participants, the supply and demand of materials, and so on).

Variable costs These costs vary, depending on the conditions applied in the project (the number

of meeting participants, the supply and demand of materials, and so on). Fixed costs These costs remain constant throughout the project (the cost of a piece of rented

equipment for the project, the cost of a consultant brought onto the project, and

so on).

Fixed costs These costs remain constant throughout the project (the cost of a piece of rented

equipment for the project, the cost of a consultant brought onto the project, and

so on).

Value engineering is a systematic approach to finding less costly ways to complete

the same work. Project managers do this all the time: choosing the best resource to

complete the work the fastest, with the highest quality, or with the appropriate materials

while still keeping the overall project costs in check.

Using the Scope Baseline

You’ll need the scope baseline, as the goal of the project team and the stakeholders

is to create all of the elements in the project scope to satisfy the requirements

of the project. The project scope statement is with the project manager throughout

the entire project, and it’s useful to ensure that all of the requirements are being

met.

At a deeper level, however, you’ll want to rely on the work breakdown structure (WBS).

Of course, the WBS is included—it’s an input to seven major planning processes, all

of which deal with costs:

Developing the project management plan This is the overarching project management plan that includes not only the cost

management plan but also the information about how the project may be financed and

contracted, and what the expectations in the organization are for cost management.

Developing the project management plan This is the overarching project management plan that includes not only the cost

management plan but also the information about how the project may be financed and

contracted, and what the expectations in the organization are for cost management. Defining the project activities In some, but not all, projects, the project includes the cost of labor as part

of its project expenses. Any resources, such as equipment and material, will need

to be paid for as part of the project budget.

Defining the project activities In some, but not all, projects, the project includes the cost of labor as part

of its project expenses. Any resources, such as equipment and material, will need

to be paid for as part of the project budget. Estimating the project costs You’ll use the WBS to help you identify how much each work package will cost, and

this can help you create a definitive estimate (details coming up).

Estimating the project costs You’ll use the WBS to help you identify how much each work package will cost, and

this can help you create a definitive estimate (details coming up). Determining the project budget You can estimate all you want, but you never know how much a project costs until

it’s done. The project budget is the cost aggregation and cost reconciliation for

each thing, service, and expense the project needs.

Determining the project budget You can estimate all you want, but you never know how much a project costs until

it’s done. The project budget is the cost aggregation and cost reconciliation for

each thing, service, and expense the project needs. Planning the project quality A cost is associated with achieving the expected quality in a project. We’ll discuss

that more in Chapter 8.

Planning the project quality A cost is associated with achieving the expected quality in a project. We’ll discuss

that more in Chapter 8. Identifying the project risks Risks often have a cost element associated with them, and the project manager and

organization may create a contingency reserve to offset the risk exposure.

Identifying the project risks Risks often have a cost element associated with them, and the project manager and

organization may create a contingency reserve to offset the risk exposure. Planning the project procurement When the project needs to procure materials, labor, or services, the project manager

must follow a cost element and purchasing process.

Planning the project procurement When the project needs to procure materials, labor, or services, the project manager

must follow a cost element and purchasing process.Along with the WBS, you’ll rely on the WBS dictionary as the third element of the

scope baseline. The WBS dictionary provides information on each deliverable and the

associated work needed to create the WBS component. In addition, the WBS may be referenced

to an organization’s code of accounts. The code of accounts is a coding system used

by the performing organization’s accounting system to account for the project work.

Estimates within the project must be mapped to the correct code of accounts so that

the organization’s ledger reflects the actual work performed, the cost of the work

performed, and any billing (internal or external) that was charged to the customer

for the completed work.

Referencing the Project Schedule

Resources are more than just people—though people are a primary expense on most projects.

The schedule management plan identifies what resources are needed, when they’re needed,

and the frequency at which they’re needed. Essentially, the schedule management plan

allows the project manager and the project team to estimate how much the resources

will cost the project, when the funds will be used to employ or consume the resources,

and the cost impact should the identified resources miss deadlines within the project.

Estimates of the duration of the activities, which predict the length of the project,

are required for decisions on financing the project. The length of the activities

will help the performing organization calculate what the total cost of the project

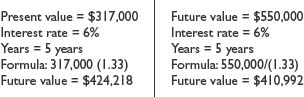

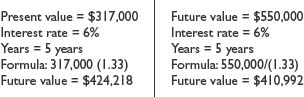

will be, including the finance charges. Recall the formula for present value? It’s

PV = FV / (1 + i)n; PV is the present value, FV is the future value, i is the interest rate, and n is the number of time periods. The future value of the monies the project will earn

may need to be measured against the present value to determine whether the project

is worth financing, as shown next.

Calculations of the duration of activities are needed to extrapolate the total cost

of the work packages. For example, if an activity is estimated to last 14 hours and

Suzanne’s cost per hour is $80, then the cost of the work package is $1120 (14 × $80).

The duration shows management how long the project is expected to last and which activities

will cost the most. It also provides the opportunity to re-sequence activities to

shorten the project duration—which consequently shortens the finance period for the

project.

Straight-line depreciation allows the organization to write off the same amount each

year. The formula for straight-line depreciation is

Straight-line depreciation allows the organization to write off the same amount each

year. The formula for straight-line depreciation is(purchase value – salvage value) / number of years in use

For example, if the purchase price of a photocopier is $7000 and the salvage value

of the photocopier in five years is $2000, the formula would read ($7000 – $2000)

/ 5 = $1000.

Resources can also cost the project if they miss deadlines with penalties, such as

a schedule change in a union’s contract, the cost of materials based on seasonal demand,

and fines and penalties for failing to adhere to scheduled regulations.

Using the Risk Register

We’ve not said much about the risk register in the project, and it’s discussed in

detail in Chapter 11 on project risk management. However, due to the integrated nature of projects, this

is one of those examples where we’ll need to jump ahead just a bit. Risks, as you

probably know from your project management experience, can have a positive or negative

effect on the outcome of a project. All identified risks, their characteristics, status,

and relevant notes are recorded in the risk register.

Most risks, especially the probable, high-impact, negative ones, need to pass through

quantitative analysis to determine how much the risk may cost the project in time

and money. Based on risk analysis, the project manager creates a special budget just

for the impact of project risks: this is called the risk contingency reserve. You

need the risk register here in cost estimating to determine how much cash you’ll need

to offset the risk events as part of your cost estimates.

Contingency reserves can also be created to deal with those pesky “unknown unknowns”

that practically every project has to deal with. The “unknown unknowns” are essentially

risks that are lurking within the project but that haven’t been specifically identified

by name, source, or probability.

Contingency reserves can be managed in a number of different ways. The most common

is to set aside an allotment of funds for the identified risks within the project.

Another approach is to create a slush fund for the entire project for identified risks

and “known unknowns.” The final approach is an allotment of funds for categories of

components based on the WBS and the project schedule. You’ll see this again in much

more detail later in this book. (We hope you’ll be able to sleep between now and Chapter 11.)

Referencing Enterprise Environmental Factors

Enterprise environmental factors are an input to the cost estimating process because

these are the processes and rules regarding how the project manager will estimate

the costs within the organization. Enterprise environmental factors also include the

market conditions that can affect the procurement process and the costs vendors provide.

You’ll also want to consider any commercially available databases for pricing information.

Commercial databases for pricing include industry-standard rates for different types

of labor, cost per unit of materials, average costs based on geographical conditions,

and other factors depending on the industry.

All of the inputs mentioned for estimating the project costs are logical; however,

your company may have its own approach to cost estimating. That’s fine—the enterprise

environmental factors are also an input to cost estimating. Enterprise environmental

factors describe the processes and rules that are unique to your organization that

you are required to follow.

Using Organizational Process Assets

One of the preferred organizational process assets is historical information. After

all, if the project’s been done before, why reinvent the wheel? Historical information

is proven information and can come from several places:

Project files Past projects within the performing organization can be used as a reference to

predict current costs and time. Ensure that the records referenced are accurate, somewhat

current, and reflective of what was actually experienced in the historical project.

Project files Past projects within the performing organization can be used as a reference to

predict current costs and time. Ensure that the records referenced are accurate, somewhat

current, and reflective of what was actually experienced in the historical project. Commercial cost-estimating databases These databases provide estimates of what the project should cost based on the

variables of the project, resources, and other conditions.

Commercial cost-estimating databases These databases provide estimates of what the project should cost based on the

variables of the project, resources, and other conditions.

The project team members’ recollections of what things cost should not be trusted

as fact, but as advice and input. Documented information is always better.

Team members Team members may have specific experience with the project costs or estimates.

Recollections may be useful but are highly unreliable when compared to documented

results.

Team members Team members may have specific experience with the project costs or estimates.

Recollections may be useful but are highly unreliable when compared to documented

results. Lessons learned Lessons-learned documentation can help the project team estimate the current project

if the lessons are from a project with a similar scope.

Lessons learned Lessons-learned documentation can help the project team estimate the current project

if the lessons are from a project with a similar scope.There are commercial estimating publications for different industries. These references

can help the project estimator confirm and predict the accuracy of estimates. If a

project manager elects to use one of these commercial databases, the estimate should

include a pointer to this database for future reference and verification.

Estimating Project Costs

Management, customers, and certain stakeholders are all going to be interested in

what the project is going to cost to complete. Several approaches to cost estimating

exist, which we’ll discuss in a moment. First, however, understand that cost estimates

have a way of following the project manager around—especially the lowest initial cost

estimate.

The estimates you’ll want to know for the PMP exam, and for your career, are reflective

of the accuracy of the information the estimate is based upon. The more accurate the

information, the better the cost estimate will be. If you’re steeped in experience

in a particular industry, you’ll probably have a good idea of what a project should

cost based on your experience. Sometimes you may hire a consultant or rely on experts

within your organization to help you predict the cost of a project. That’s great!

That’s an example of expert judgment.

Using Analogous Estimating

Analogous estimating relies on historical information to predict the cost of the current

project. It is also known as top-down estimating. The analogous estimating process

considers the actual cost of a historical project as a basis for the current project.

The cost of the historical project is applied to the cost of the current project,

taking into account the scope and size of the current project as well as other known

variables.

Analogous estimating is a form of expert judgment. This estimating approach takes

less time to complete than other estimating models, but it is also less accurate.

This top-down approach is good for fast estimates to get a general idea of what the

project may cost.

The following is an example of analogous estimating: The Carlton Park Project was

to grade and pave a sidewalk around a pond in the community park. The sidewalk of

Carlton Park was 1048 feet-by-6 feet, had a textured surface, had some curves around

trees, and cost $25,287 to complete. The current project, King Park, will have a similar

surface and will cover 4500 feet-by-6 feet. The analogous estimate for this project,

based on the work in Carlton Park, is $108,500. This is based on the price per foot

of material at $4.02.

As part of the planning process, the project manager must determine what resources

are needed to complete the project. Resources include the people, equipment, and materials

that will be utilized to complete the work. In addition, the project manager must

identify the quantity of the needed resources and when the resources are needed for

the project. The identification of the resources, the needed quantity, and the schedule

of the resources are directly linked to the expected cost of the project work.

As part of the planning process, the project manager must determine what resources

are needed to complete the project. Resources include the people, equipment, and materials

that will be utilized to complete the work. In addition, the project manager must

identify the quantity of the needed resources and when the resources are needed for

the project. The identification of the resources, the needed quantity, and the schedule

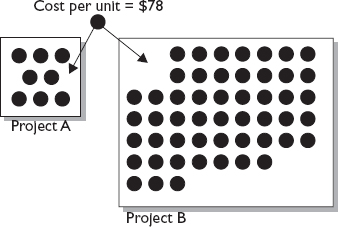

of the resources are directly linked to the expected cost of the project work.Using Parametric Estimating

Parametric modeling uses a mathematical model based on known parameters to predict

the cost of a project. The parameters in the model can vary based on the type of work

being completed and can be measured by cost per cubic yard, cost per unit, and so

on. A complex parameter can be cost per unit, with adjustment factors based on the

conditions of the project. The adjustment factors may have additional modifying factors,

depending on additional conditions. For example, parametric estimating could say that

the cost per square foot of construction is $28 using standard materials, and could

then charge additional fees if the client varies the materials.

To use parametric modeling, the factors upon which the model is based must be accurate.

The factors within the model are quantifiable and don’t vary much based on the effort

applied to the activity. And, finally, the model must be scalable between project

sizes. The parametric model using a scalable cost-per-unit approach is depicted next.

There are two types of parametric estimating:

Regression analysis This statistical approach predicts what future values may be, based on historical

values. Regression analysis creates quantitative predictions based on variables within

one value to predict variables in another. This form of estimating relies solely on

pure statistical math to reveal relationships between variables and predict future

values.

Regression analysis This statistical approach predicts what future values may be, based on historical

values. Regression analysis creates quantitative predictions based on variables within

one value to predict variables in another. This form of estimating relies solely on

pure statistical math to reveal relationships between variables and predict future

values. Learning curve This approach is simple: The cost per unit decreases the more units workers complete,

because workers learn as they complete the required work and perform the tasks more

quickly and efficiently. The estimate is considered parametric, since the formula

is based on repetitive activities, such as wiring telephone jacks, painting hotel

rooms, or performing other activities that are completed over and over within a project.

The cost per unit decreases as the experience increases, because the time to complete

the work becomes shorter. Of course, there will always be some cost associated with

the work, but there is a reduction in costs as the workers become more experienced

in completing the activities.

Learning curve This approach is simple: The cost per unit decreases the more units workers complete,

because workers learn as they complete the required work and perform the tasks more

quickly and efficiently. The estimate is considered parametric, since the formula

is based on repetitive activities, such as wiring telephone jacks, painting hotel

rooms, or performing other activities that are completed over and over within a project.

The cost per unit decreases as the experience increases, because the time to complete

the work becomes shorter. Of course, there will always be some cost associated with

the work, but there is a reduction in costs as the workers become more experienced

in completing the activities.

Don’t worry too much about regression analysis for the exam. You’re more likely to

have questions on the learning curve topic.

Using Bottom-Up Estimating

Bottom-up estimating starts from zero, accounts for each component of the WBS, and

arrives at a sum for the project. It is completed with the project team and can be

one of the most time-consuming methods used to predict project costs. Although this

method is more expensive because of the time invested to create the estimate, it is

also one of the most accurate methods. A fringe benefit of completing a bottom-up

estimate is that the project team may buy into the project work since they see the

cost and value of each cost within the project.

Creating a Three-Point Cost Estimate

It’s sometimes risky to use just one cost estimate for a project’s activity, especially

when the work hasn’t been completed before. And like any project work, you don’t know

how much it’s really going to cost until you pay for it. Issues, errors, delays, and

unknown risks can affect the project cost. Three-point estimates are also known as

simple averaging estimates. A three-point cost estimate attempts to find the average

of the cost of an activity using three factors:

Optimistic cost estimate

Optimistic cost estimate Most likely cost estimate

Most likely cost estimate Pessimistic cost estimate

Pessimistic cost estimateYou can then simply sum up the three cost estimate values and divide by 3. Or you

can use the program evaluation and review technique (PERT) approach, which is slightly

different. PERT is a weighted average to the most likely cost estimate value. The

PERT formula is

(optimistic cost estimate + (4 × most likely cost estimate) + pessimistic cost estimate) / 6

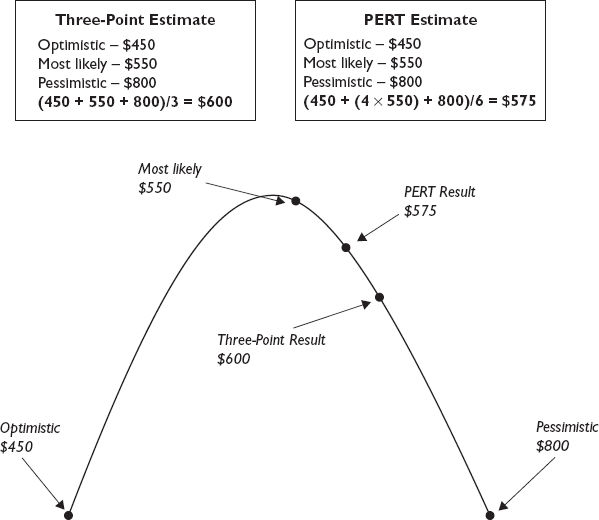

Figure 7-1 shows the slight difference between a true average of the costs and the PERT approach.

FIGURE 7-1 Costs can be averaged with PERT or three-point estimates.

In either approach, simple averaging or PERT, you have to create three cost estimates

for each activity. This can get tiresome and overwhelming, especially on a larger

project. And if you elect to use an average estimate, be certain to document the approach

you took and record the actual costs of the project activities for future historical

information.

Both the three-point estimate and PERT expressed expected costs as cE. You might also

see cM, cO, and cP to represent most-likely costs, optimistic costs, and pessimistic

costs, respectively. Triangular distribution means it’s a three-point estimate, while

a beta distribution means it’s the traditional PERT formula.

Using Computer Software

Although the PMP examination is vendor-neutral, having a general knowledge of how

computer software can assist the project manager is necessary. Several computer programs

are available that can streamline project work estimates and increase their accuracy.

These tools can include project management software, spreadsheet programs, and simulations.

Analyzing Vendor Bids

Sometimes it’s just more cost-effective to hire someone else to do the work. Other

times, the project manager has no choice because no one within the organization has

the required skill set. In either condition, the vendors’ bids need to be analyzed

to determine which vendor should be selected based on their ability to satisfy the

project scope, the expected quality, and the cost of their services. We’ll talk all

about procurement in Chapter 12.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.03

Analyzing Cost Estimating Results

The output of cost estimating is the actual cost estimates of the resources required

to complete the project work. The estimate is typically quantitative and can be presented

in detail against the WBS components or summarized in terms of a grand total according

to various phases of the project or its major deliverables. Each resource in the project

must be accounted for and assigned to a cost category. Categories include the following:

Labor costs

Labor costs Material costs

Material costs Travel costs

Travel costs Supplies costs

Supplies costs Hardware costs

Hardware costs Software costs

Software costs Special categories (inflation, cost reserve, and so on)

Special categories (inflation, cost reserve, and so on)The cost of the project is expressed in monetary terms, such as dollars, euros, or

yen, so management can compare projects based on costs. It may be acceptable, depending

on the demands of the performing organization, to provide estimates in staffing hours

or days of work to complete the project along with the estimated costs.

As projects have risks, the cost of the risks should be identified along with the

cost of the risk responses. The project manager should list the risks, their expected

risk event value, and the response to the risk should it come into play. We’ll cover

risk management in detail in Chapter 11.

The project manager also has to consider changes to the project scope. Chances are

that if the project scope increases in size, the project budget should reflect these

changes. A failure to offset approved changes with an appropriate dollar amount will

skew the project’s cost baselines and show a false variance.

Refining the Cost Estimates

Cost estimates can also pass through progressive elaboration. As more details are

acquired as the project progresses, the estimates are refined. Industry guidelines

and organizational policies may define how the estimates are refined, but there are

three generally accepted categories of estimating accuracy:

Rough order of magnitude This estimate is “rough” and is used during the initiating processes and in top-down

estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –25 percent to +75 percent.

Rough order of magnitude This estimate is “rough” and is used during the initiating processes and in top-down

estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from –25 percent to +75 percent. Budget estimate This estimate is also somewhat broad and is used early in the planning processes

and also in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from

–10 percent to +25 percent.

Budget estimate This estimate is also somewhat broad and is used early in the planning processes

and also in top-down estimates. The range of variance for the estimate can be from

–10 percent to +25 percent. Definitive estimates This estimate type is one of the most accurate. It’s used late in the planning

processes and is associated with bottom-up estimating. The range of variance for the

estimate can be from –5 percent to +10 percent.

Definitive estimates This estimate type is one of the most accurate. It’s used late in the planning

processes and is associated with bottom-up estimating. The range of variance for the

estimate can be from –5 percent to +10 percent.Considering the Supporting Detail

Once the estimates have been completed, the basis of the estimates must be organized

and documented to show how they were created. This material, even the notes that contributed

to the estimates, may provide valuable information later in the project. Specifically,

the supporting detail includes the following:

Information on the project scope work This may be provided by referencing the WBS.

Information on the project scope work This may be provided by referencing the WBS. Information on the approach used in developing the cost estimates This can include how the estimate was accomplished and the parties involved with

creating the estimate.

Information on the approach used in developing the cost estimates This can include how the estimate was accomplished and the parties involved with

creating the estimate. Information on the assumptions and constraints made while developing the cost estimates Assumptions and constraints can be wrong and can change the entire cost estimate.

The project manager must list what assumptions and constraints were made during the

cost estimate in order to communicate with stakeholders how she arrived at the estimate.

Information on the assumptions and constraints made while developing the cost estimates Assumptions and constraints can be wrong and can change the entire cost estimate.

The project manager must list what assumptions and constraints were made during the

cost estimate in order to communicate with stakeholders how she arrived at the estimate. Information on the range of variance in the estimate For example, based on the estimating method used, the project cost may be $220,000

± $15,000. This project cost may be as low as $205,000 or as high as $235,000.

Information on the range of variance in the estimate For example, based on the estimating method used, the project cost may be $220,000

± $15,000. This project cost may be as low as $205,000 or as high as $235,000.CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.04

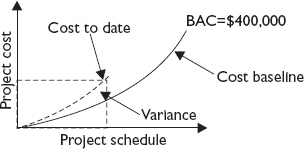

Creating a Project Budget

Cost budgeting is the process of assigning a cost to an individual work package. The

sum of the costs of the individual work packages contribute to the predicted cost

for the entire project. The goal of this process is to assign costs to the work in

the project so it can be measured for performance. This is the creation of the cost

baseline, as shown here:

Cost budgeting and cost estimates may go hand in hand, but estimating should be completed

before a budget is requested—or assigned. Cost budgeting applies the cost estimates

over time. This results in a time-phased estimate for cost, allowing an organization

to predict cash flow needs. Cost estimates show costs by category, whereas a cost

budget shows costs across time.

Developing the Project Budget

Many of the tools and techniques used to create the project cost estimates are also

used to create the project budget. The following is a quick listing of the tools you

can expect to see on the PMP exam:

Cost aggregation Costs are parallel to each WBS work package. The costs of each work package are

aggregated to their corresponding control accounts. Each control account is then aggregated

to the sum of the project costs.

Cost aggregation Costs are parallel to each WBS work package. The costs of each work package are

aggregated to their corresponding control accounts. Each control account is then aggregated

to the sum of the project costs. Reserve analysis You should be familiar with two reserves for your PMP exam. The first you’ve already

learned about: the risk contingency reserve. The second cost reserve is for management

reserve, and this chunk of cash is for unplanned changes to the project scope and

cost. It’s a buffer of cash for fluctuations for cost, errors, or other increases

in project cost. These reserves are not part of the cost baseline but are part of

the project budget. In other words, you don’t use these funds unless there’s a problem

in the project.

Reserve analysis You should be familiar with two reserves for your PMP exam. The first you’ve already

learned about: the risk contingency reserve. The second cost reserve is for management

reserve, and this chunk of cash is for unplanned changes to the project scope and

cost. It’s a buffer of cash for fluctuations for cost, errors, or other increases

in project cost. These reserves are not part of the cost baseline but are part of

the project budget. In other words, you don’t use these funds unless there’s a problem

in the project. Expert judgment Subject matter experts can be consultants, vendors, internal stakeholders, project

team members, and other stakeholders that can help budget the project work. You might

also rely on trade groups and other entities within your organization.

Expert judgment Subject matter experts can be consultants, vendors, internal stakeholders, project

team members, and other stakeholders that can help budget the project work. You might

also rely on trade groups and other entities within your organization. Historical relationships This approach uses a parametric model to extrapolate what costs will be for a project

(for example, cost per hour and cost per unit). It can include variables and points

based on conditions. This approach might also use a top-down estimate type based on

historical information. A top-down estimate is also known as an analogous estimate

type.

Historical relationships This approach uses a parametric model to extrapolate what costs will be for a project

(for example, cost per hour and cost per unit). It can include variables and points

based on conditions. This approach might also use a top-down estimate type based on

historical information. A top-down estimate is also known as an analogous estimate

type. Funding limit reconciliation Organizations have only so much cash to allot to projects—and no, you can’t have

all the monies right now. Funding limit reconciliation is an organization’s approach

to managing cash flow against the project deliverables based on a schedule, milestone

accomplishments, or data constraints. This helps an organization plan when monies

will be devoted to a project rather than using all of the funds available at the start

of a project. In other words, the monies for a project budget will become available

based on dates and/or deliverables. If the project doesn’t hit predetermined dates

and products that were set as milestones, the additional funding becomes questionable.

Funding limit reconciliation Organizations have only so much cash to allot to projects—and no, you can’t have

all the monies right now. Funding limit reconciliation is an organization’s approach

to managing cash flow against the project deliverables based on a schedule, milestone

accomplishments, or data constraints. This helps an organization plan when monies

will be devoted to a project rather than using all of the funds available at the start

of a project. In other words, the monies for a project budget will become available

based on dates and/or deliverables. If the project doesn’t hit predetermined dates

and products that were set as milestones, the additional funding becomes questionable.Creating the Cost Baseline

A project’s cost baseline measures performance and predicts the expenses over the

life of the project. It’s usually shown as an S-curve, as in Figure 7-2. The cost baseline allows the project manager and management to predict when the

project will be spending monies and over what time period. Any discrepancies early

on between the predicted baseline and the actual costs serve as a signal that the

project is slipping.

FIGURE 7-2 Cost baselines show predicted project and phase performance.

Large projects that have multiple deliverables may use multiple cost baselines to

illustrate the costs within each phase. In addition, larger projects may use cost

baselines to predict spending plans, cash flows of the project, and overall project

performance.

Establishing Project Funding Requirements

The project’s cost baseline can help the project manager and the organization determine

when the project will need cash infusions. Based on phases, milestones, and capital

expenses, the project funding requirements can be mapped to the project schedule and

the organization can plan accordingly. This is where the concept of project step funding

originates. The curve of the project’s timeline is funded in steps, where “step” is

an amount of funds allotted to the project to reach the next milestone in the project.

Recall from the project life cycle that milestones are usually tied to the completion

of project phases. Each phase creates a deliverable and usually allows the project

to move on to the next phase of project execution. The pause for review and determination

of additional funds for the project is called a phase gate.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.05

Implementing Cost Control

Cost control focuses on the ability of costs to change and on the ways of allowing

or preventing cost changes from happening. When a change does occur, the project manager

must document the change and the reason why the change occurred, and, if necessary,

she will create a variance report. Cost control is concerned with understanding why

the cost variances, both good and bad, have occurred. The “why” behind the variances

allows the project manager to make appropriate decisions on future project actions.

Ignoring the project cost variances may cause the project to suffer from budget shortages,

additional risks, or scheduling problems. When cost variances happen, they must be

examined, recorded, and investigated. Cost control allows the project manager to confront

the problem, find a solution, and then act accordingly. Specifically, cost control

focuses on the following activities:

Controlling causes of change to ensure the changes are actually needed

Controlling causes of change to ensure the changes are actually needed Controlling and documenting changes to the cost baseline as they happen

Controlling and documenting changes to the cost baseline as they happen Controlling changes in the project and their influence on cost

Controlling changes in the project and their influence on cost Performing cost monitoring to recognize and understand cost variances

Performing cost monitoring to recognize and understand cost variances Recording appropriate cost changes in the cost baseline

Recording appropriate cost changes in the cost baseline Preventing unauthorized changes to the cost baseline

Preventing unauthorized changes to the cost baseline Communicating the cost changes to the proper stakeholders

Communicating the cost changes to the proper stakeholders Working to bring and maintain costs within an acceptable range

Working to bring and maintain costs within an acceptable rangeConsidering Cost Control Inputs

To implement cost control, the project manager must rely on several documents and

processes.

Cost performance baseline The cost performance baseline is the expected cost the project will incur. This

time-phased budget reflects the amount that will be spent throughout the project.

Recall that the cost performance baseline is a tool used to measure project performance.

And, yes, it’s the same thing as the cost baseline.

Cost performance baseline The cost performance baseline is the expected cost the project will incur. This

time-phased budget reflects the amount that will be spent throughout the project.

Recall that the cost performance baseline is a tool used to measure project performance.

And, yes, it’s the same thing as the cost baseline. Cost management plan The cost management plan dictates how cost variances will be managed.

Cost management plan The cost management plan dictates how cost variances will be managed. Project funding requirements The funds for a project are not allotted all at once, but stair-stepped in alignment

with project deliverables. Thus, as the project moves toward completion, additional

funding is allotted. This allows for cash-flow forecasting. In other words, an organization

doesn’t need to have all of the project’s budget allotted at the start of the project,

but it can predict, based on expected income, that all of the project’s budget will

be available in incremental steps.

Project funding requirements The funds for a project are not allotted all at once, but stair-stepped in alignment

with project deliverables. Thus, as the project moves toward completion, additional

funding is allotted. This allows for cash-flow forecasting. In other words, an organization

doesn’t need to have all of the project’s budget allotted at the start of the project,

but it can predict, based on expected income, that all of the project’s budget will

be available in incremental steps. Work performance data Reports on project progress, status of project activities, status of project deliverables,

and information about the project costs and the cost of the balance of the project

work.

Work performance data Reports on project progress, status of project activities, status of project deliverables,

and information about the project costs and the cost of the balance of the project

work. Organizational process assets One category of inputs for cost control are the existing methods, forms, templates,

and guidelines in the organization’s organizational process assets.

Organizational process assets One category of inputs for cost control are the existing methods, forms, templates,

and guidelines in the organization’s organizational process assets.Creating a Cost Change Control System

Sometimes a project manager must add or remove costs from a project. The cost change

control system is part of the integrated change control system and documents the procedures

to request, approve, and incorporate changes to project costs.

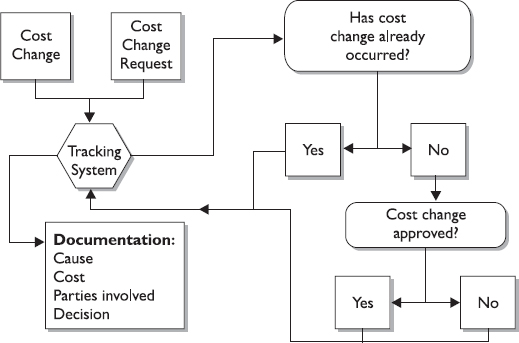

When a cost change enters the system, the project manager must create the appropriate

paperwork and follow a tracking system and procedures to obtain approval on the proposed

change. Figure 7-3 demonstrates a typical workflow for cost change approval. If a change gets approved,

the cost baseline is updated to reflect the approved changes. If a request gets denied,

the denial must be documented for future potential reference.

FIGURE 7-3 A cost change control system tracks and documents cost changes.

CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.06

Measuring Project Performance

Earned value management (EVM) is the process of measuring the performance of project

work against a plan to identify variances. It can also be useful in predicting future

variances and the final costs at completion. EVM is a system of mathematical formulas

that compares work performed against work planned and measures the actual cost of

the work performed. It’s an important part of cost control because it allows a project

manager to predict future variances from the expenses to date within the project.

See the video “Earned Value Management.”

See the video “Earned Value Management.”In regard to cost management, EVM is concerned with the relationships between three

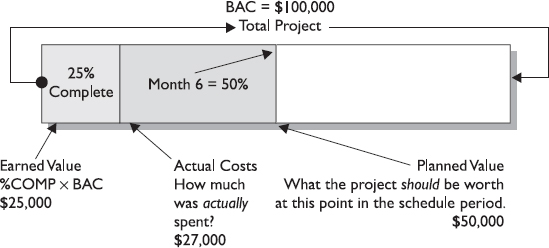

formulas that reflect project performance. Figure 7-4 demonstrates the connection between the following EVM values:

FIGURE 7-4 Earned value management measures project performance.

Planned value (PV) Planned value is the work scheduled and the budget authorized to accomplish that

work. For example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and month six represents

50 percent of the project work, the PV for month six is $50,000. The entire project’s

planned value—that is, what the project should be worth at completion—is known as

the budget at completion. You might also see the sum of the planned value called the

performance measurement baseline.

Planned value (PV) Planned value is the work scheduled and the budget authorized to accomplish that

work. For example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and month six represents

50 percent of the project work, the PV for month six is $50,000. The entire project’s

planned value—that is, what the project should be worth at completion—is known as

the budget at completion. You might also see the sum of the planned value called the

performance measurement baseline. Earned value (EV) Earned value is the physical work completed to date and the authorized budget for

that work. For example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and the work completed

to date represents 25 percent of the entire project work, its EV is $25,000.

Earned value (EV) Earned value is the physical work completed to date and the authorized budget for

that work. For example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and the work completed

to date represents 25 percent of the entire project work, its EV is $25,000. Actual cost (AC) Actual cost is the actual amount of monies the project has required to date. For

example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and $35,000 has been spent on the project

to date, the AC of the project would be $35,000.

Actual cost (AC) Actual cost is the actual amount of monies the project has required to date. For

example, if a project has a budget of $100,000 and $35,000 has been spent on the project

to date, the AC of the project would be $35,000.These three values offer key information about the worth of the project to date (EV),

the cost of the project work to date (AC), and the planned value of the work to date

(PV).

Finding the Variances

At the end of the project, will there be a budget variance (VAR)? Any variance at

the end of the project is calculated by subtracting the actual costs (ACs) of the

project work from the budget at completion (BAC). The term BAC refers to the estimated

budget at completion—what you and the project customer agree the project will likely

cost. Of course, you don’t actually know how much the project will cost until it’s

completely finished. So throughout the project, a variance is any result that is different

from what is planned or expected.

Cost Variances

The cost variance (CV) is the difference between the earned value and the actual costs

(AC). For example, for a project that has a budget of $200,000 and has earned or completed

10 percent of the project value, the EV is $20,000. However, due to some unforeseen

incidents, the project manager had to spend $25,000 to complete that $20,000 worth

of work. The AC of the project, at this point, is $25,000 and the cost variance is

–$5000. Thus, the equation for cost variance is CV = EV – AC.

Schedule Variances

A schedule variance (SV) is the value that represents the difference between where

the project was planned to be at a certain point in time and where the project actually

is. For example, consider a project with a budget of $200,000 that’s expected to last

two years. At the end of year one, the project team has planned that the project be

60-percent complete. Thus, the planned value (PV) for 60-percent completion equates

to $120,000—the expected worth of the project work at the end of year one. But let’s

say that at the end of year one the project is only 40-percent complete. The EV at

the end of year one is, therefore, $80,000. The difference between the PV and the

EV is the SV: –$40,000. The equation for schedule variance is SV = EV – PV.

When it comes to variances, don’t forget the negative signs.

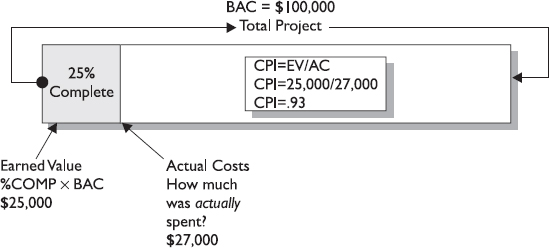

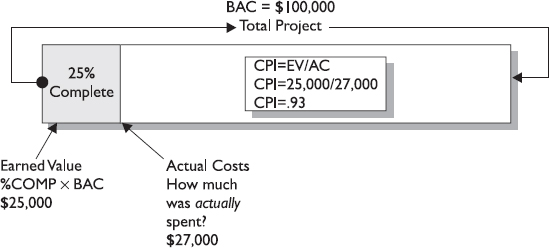

Calculating the Cost Performance Index

The cost performance index (CPI) shows the amount of work the project is completing

per dollar spent on the project. In other words, a CPI of 0.93 means it is costing

$1.00 for every 93 cents’ worth of work. Or you could say the project is losing 7

cents on every dollar spent on the project. Let’s say a project has an EV of $25,000

and an AC of $27,000. The CPI for this project is thus 0.93. The closer the number

is to 1, the better the project is doing. The equation for cost performance index

is CPI = EV / AC.

CPI is a value that shows how the project costs are performing to plan. It relates

the work you’ve accomplished to the amount you’ve spent to accomplish it. A CPI under

1.00 means the project is performing poorly against the plan. However, a CPI over

1.00 does not necessarily mean that the project is performing well. It could mean

that estimates were inflated or that an expenditure for equipment is late or sitting

in accounts payable and has not yet been entered into the project accounting cycle.

Finding the Schedule Performance Index

The schedule performance index (SPI) is similar to the CPI. The SPI, however, reveals

how closely the project is on schedule. Again, as with the CPI, the closer the quotient

is to 1, the better. The formula for schedule performance index is SPI = EV / PV.

In our example, the EV is $20,000, and let’s say the PV, where the project is supposed

to be, is calculated as $30,000. The SPI for this project is then 0.67—way off target!

Preparing for the Estimate at Completion

The estimate at completion (EAC) is a hypothesis of what the total cost of the project

will be. Before the project begins, the project manager completes an estimate for

the project deliverables based on the scope baseline. As the project progresses, in

most projects there will be some variances between the cost estimate and the actual

cost. The difference between these is the variance for the deliverable.

Know this formula for calculating the EAC: EAC = BAC / CPI. It’s the most common of

the formulas presented.

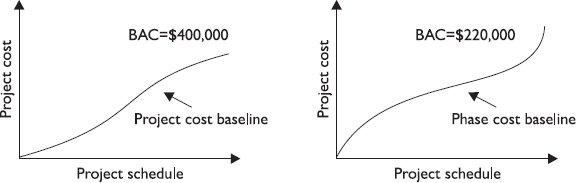

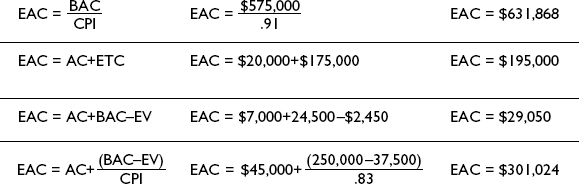

The EAC is based on experiences in the project so far. There are several different

formulas for calculating the EAC, as Figure 7-5 demonstrates. For now, and for the exam, here’s the EAC formula you’ll need to know:

EAC = BAC / CPI. In our project, the BAC is $200,000. The CPI was calculated to be

0.80. The EAC for this project, then, is $250,000.

FIGURE 7-5 There are many approaches to calculating the EAC.

Considering Project Performance

Another variation of the EAC is to consider the project performance beyond just the

CPI. This approach looks at the project performance, good or bad, and considers the

actual costs of the project to date, the budget at completion, and the project’s earned

value. This EAC formula is EAC = AC + BAC – EV.

For example, consider a project with a BAC of $350,000 that’s 45-percent complete,

though it’s supposed to be 60-percent complete at this point. The earned value for

this project is 45 percent of the $350,000, which is $157,500. In this scenario, the

project has actually spent $185,000—considerably more than what the project should

have spent. Let’s plug in this EAC formula. EAC = $185,000 + $350,000 – $157,500.

The EAC for this project using this formula would be $377,500.

Consider Project Variances

Sometimes a project may have some wild swings on the project cost variances and the

project schedule variances, and you want to take these variances into consideration

when predicting the project’s estimate at completion. Usually, it’s the project schedule

that’s affecting the project’s ability to meet its cost obligations because the planned

value continues to slip, which wrecks the SPI. Add to that the concept that the longer

a project takes to complete, the more likely that the project costs will increase.

Here’s this windy formula (get your slide rule out): EAC = AC + [(BAC – EV) / (CPI

× SPI)]. Let’s try this one using the same values as the last example. Consider a

project with a BAC of $350,000 that’s 45-percent complete, though it’s supposed to

be 60-percent complete. The earned value for this project is 45 percent of $350,000,

which is $157,500. In this scenario, the project has actually spent $185,000—considerably

more than what the project should have. Here are the parts of our formula:

Actual cost = $185,000

Planned value = $210,000

Budget at completion = $350,000

Earned value = $157,500

Cost performance index = 0.85

Schedule performance index = 0.75

Let’s plug these values into the formula EAC = AC + [(BAC – EV) / (CPI × SPI)]:

EAC = $185,000 + [($350,000 – $157,500) / (0.85 × 0.75)]

EAC = $185,000 + (192,500 / 0.64)

EAC = $185,000 + 300,781.25

EAC = $485,781.25

Finding the Estimate to Complete

The estimate to complete (ETC) shows how much more money will be needed to complete

the project. To calculate the ETC, you need to know another formula: the estimate

at completion (EAC). Remember that the EAC is what you predict the project will cost

based on current conditions. The EAC is a pretty straightforward formula: EAC – AC.

Let’s say our EAC was calculated to be $250,000 and that our AC is currently $25,000;

our ETC would then be $225,000.

Accounting for Flawed Estimates

Imagine a project to install a new operating system on 1000 workstations. One of the

assumptions the project team made was that each workstation had the correct hardware

to install the operating system automatically. As it turns out, this assumption was

wrong, and now the project team must change their approach to installing the system.

Because the assumption to install the operating system was flawed, a new estimate

to complete the project is needed. This is the most accurate approach in estimating

how much more the project will cost, but it’s the hardest to do. This new estimate

to complete the work is the ETC, which represents how much more money is needed to

complete the project work, and its formula is simply a revised estimate of how much

more the remaining work will cost to complete. Nothing tricky here.

Accounting for Anomalies

During a project, sometimes weird stuff happens. These anomalies, or weird stuff,

can cause project costs to be skewed. For example, consider a project with a $10,000

budget to construct a wooden fence around a property line. One of the project team

members makes a mistake while installing the wooden fence and reverses the face of

the fencing material. In other words, the material for the outside of the fence faces

the wrong direction.

The project now has to invest additional time to remove the fence material, correct

the problem, and replace any wood that may have been damaged in the incorrect installation.

The project, mistakes and all, is thus considered 20 percent done, so the earned value

is $2000. This anomaly likely won’t happen again, but it will add costs to the project.

For these instances, when events happen but the project manager doesn’t expect similar

events to happen again, the following ETC formula should be used: ETC = (BAC – EV).

Let’s try this out with our fencing project. The project’s EV is only $2000 since

the project has barely started. The formula would read ETC = $10,000 – $2,000.

Monies that have been spent on a project are called sunk costs. In evaluating whether

a project should continue or not, the sunk costs should not be considered—they are

gone forever.

Accounting for Typical Variances

This last ETC formula is used when existing variances in the project are expected

to be typical of the remaining variances in the project. For example, a project manager

has overestimated the competence of the workers to complete the project work. Because

the project team is not performing at the level the project manager expected, work

is completed late and in a faulty manner. Rework has been a common theme for this

project.

The formula for these instances is ETC = (BAC – EV) / CPI. In our example, let’s say

the AC is $45,000, the BAC is $250,000, the EV is $37,500, and our CPI is calculated

to be 0.83. The ETC formula for this project is ETC = ($250,000 – $37,500) / 0.83.

The result of the formula (following the order of operations) is thus $256,024.

Calculating the To-Complete Performance Index

Imagine a formula that would tell you if the project can meet the budget at completion

based on current conditions. Or imagine a formula that can predict whether the project

can even achieve your new estimate at completion. Well, forget your imagination and

just use the to-complete performance index (TCPI). This formula can forecast the likelihood

of a project to achieve its goals based on what’s happening in the project right now.

There are two different flavors for the TCPI, depending on what you want to accomplish:

If you want to see if your project can meet the budget at completion, you’ll use

this formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV) / (BAC – AC).

If you want to see if your project can meet the budget at completion, you’ll use

this formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV) / (BAC – AC). If you want to see if your project can meet the newly created estimate at completion,

you’ll use this version of the formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV) / (EAC – AC).

If you want to see if your project can meet the newly created estimate at completion,

you’ll use this version of the formula: TCPI = (BAC – EV) / (EAC – AC).Any result greater than 1 in either formula means that you’ll have to be more efficient

than you planned to achieve the BAC or the EAC, depending on whichever formula you’ve

used. Basically, the greater the number is over 1, the less likely it is that you’ll

be able to meet your BAC or EAC. The lower the number is from 1, the more likely you

are to reach your BAC or EAC (again, depending on which formula you’ve used).

Finding the Variance at Completion

Whenever you talk about variances, it’s the difference between what was expected and

what was experienced. The formula for the variance at completion (VAC) is VAC = BAC

– EAC. In our example, the BAC was $200,000 and the EAC was $250,000, so the VAC is

predicted to be $50,000.

The Five EVM Formula Rules

For EVM formulas, the following five rules should be remembered:

1. Always start with EV.

2. Variance means subtraction.

3. Index means division.

4. Less than 1 is bad in an index.

5. Negative is bad in a variance.

The formulas for earned value analysis can be completed manually or through project

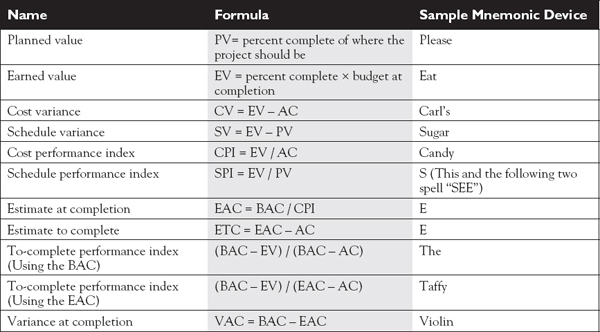

management software. For the exam, you’ll want to memorize these formulas. Table 7-1 shows a summary of all the formulas, as well as a sample, albeit goofy, mnemonic

device.

TABLE 7-1 A Summary of EVM Formulas

These aren’t much to memorize, I know, but you should. Although you won’t have an

overwhelming amount of EVM questions on your exam, these are free points if you know

the formulas and can do the math.

These aren’t much to memorize, I know, but you should. Although you won’t have an

overwhelming amount of EVM questions on your exam, these are free points if you know

the formulas and can do the math. I have a present for you. It’s a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet called “EV Worksheet.”

It has all of these formulas in action. I recommend you make up some numbers to test

your ability to complete these formulas and then plug your values into Excel to confirm

your math. Enjoy!

I have a present for you. It’s a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet called “EV Worksheet.”

It has all of these formulas in action. I recommend you make up some numbers to test

your ability to complete these formulas and then plug your values into Excel to confirm

your math. Enjoy!Additional Planning

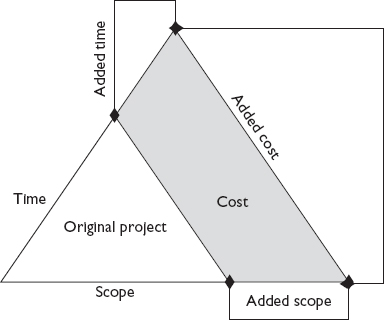

Planning is an iterative process. Throughout the project, there will be demands for

additional planning—and an output of cost control is one of those demands. Consider

a project that must complete by a given date and that also has a set budget. The balance

between the schedule and the cost must be maintained. The project manager can’t assign

a large crew to complete the project work if the budget won’t allow it. The project

manager must, through planning, get as creative as possible to figure out an approach

to accomplish the project without exceeding the budget.

The balance between cost and schedule is an ongoing battle. Although it’s usually

easier to get more time than money, this isn’t always the case. Consider, for example,

deadlines that can’t be moved; or perhaps the company faces fines and penalties; or

a deadline that centers on a tradeshow, an expo, or the start of the school year.

Using Computers

It’s hard to imagine a project, especially a large project, moving forward without

the use of computers. Project managers can rely on project management software and

spreadsheet programs to assist them in calculating actual costs, earned value, and

planned value.

It’s not difficult to create a spreadsheet with the appropriate earned value formulas.

After you’ve created the spreadsheet, you can save it as a template and use it on

multiple projects. If you want, and if your software allows it, you can tie in multiple

earned value spreadsheets to a master file to track all of your projects at a glance.

It’s not difficult to create a spreadsheet with the appropriate earned value formulas.

After you’ve created the spreadsheet, you can save it as a template and use it on

multiple projects. If you want, and if your software allows it, you can tie in multiple

earned value spreadsheets to a master file to track all of your projects at a glance.CERTIFICATION OBJECTIVE 7.07

Considering the Cost Control Results

Cost control is an ongoing process throughout the project. The project manager must

actively monitor the project for variances to costs. Specifically, the project manager

should always do the following:

Monitor cost variances and then understand why variances have occurred.

Monitor cost variances and then understand why variances have occurred. Update the cost baseline as needed based on approved changes.

Update the cost baseline as needed based on approved changes. Work with the conditions and stakeholders to prevent unnecessary changes to the

cost baseline.

Work with the conditions and stakeholders to prevent unnecessary changes to the

cost baseline. Communicate to the appropriate stakeholders cost changes as they occur.

Communicate to the appropriate stakeholders cost changes as they occur. Maintain costs within an acceptable and agreed-upon range.

Maintain costs within an acceptable and agreed-upon range.Revising the Cost Estimates

As the project progresses and more detail becomes available, there may be a need to

update the cost estimates. A revision to the cost estimates requires communication

with the key stakeholders to share why the costs were revised. A revision to the cost

estimates may have a ripple effect: Other parts of the project may need to be adjusted

to account for the changes in cost, the sequence of events may need to be reordered,

and resources may have to be changed. In some instances, the revision of the estimates

may be expected, as with phased-gate estimating in a lengthy project.

Updating the Budget

Updating the budget is slightly different from revising a cost estimate. Budget updates

allow the cost baseline to be changed. The cost baseline is the “before project snapshot”

of what the total project scope and the individual WBS components should cost. Should