11

VAL DI MAZARA

Val di Mazara is the largest of the three historic regions of Sicily. It includes Palermo, the capital city of the Norman Kingdom of Sicily in the twelfth century and of modern-day Sicily. Val di Mazara extends from the intensively cultivated vineyards of western Sicily to the island's interior, home to little more than vast tracts of high plains and steep hills that are blanketed by wheat fields and punctuated with isolated vineyards. In contrast with Val di Noto and Val Demone to its east, Val di Mazara historically was more influenced by the cultures of the Phoenicians and the Muslims than the Greeks. The vast landholdings known as latifondi also dominated it to a greater extent, from the Roman era through the nineteenth century. The two principal wine areas in the region are Val di Mazara—West, which comprises the island of Pantelleria, Marsala, and Western Sicily, and Val di Mazara—East, which includes the Palermo Highlands, Terre Sicane, Sicily-Center, and the Agrigento-Caltanissetta Highlands.

VAL DI MAZARA—WEST

PANTELLERIA

Legend has it that the Phoenician lunar goddess, Tanit, enamored of Apollo, attracted his attention by pouring Pantelleria wine instead of ambrosia into his goblet. Giacomo Casanova, the eighteenth-century adventurer, is said to have offered Pantelleria to his lovers. One sip of a modern-day Passito di Pantelleria convinces me that such tales are not far-fetched. The sweet wine of Pantelleria is Italy's most extravagant dessert wine.

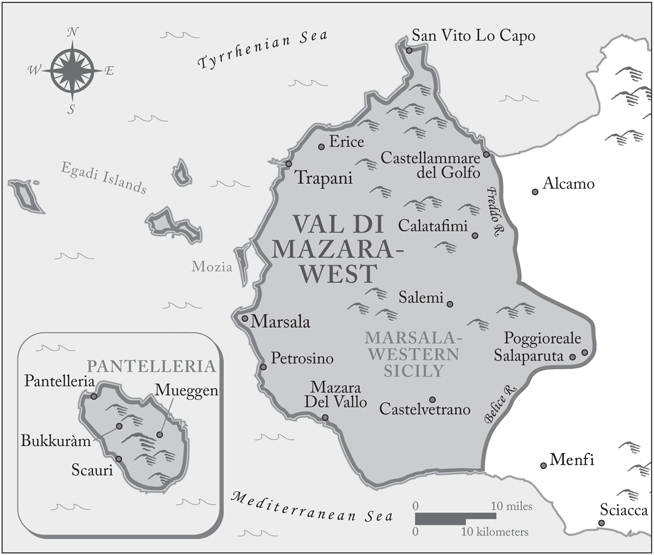

MAP 2.

Val di Mazara—West

Though Pantelleria may seem to be off the beaten path, its strategic position in the Strait of Sicily was not overlooked by Benito Mussolini, who saw it as Italy's unsinkable aircraft carrier in the center of the Mediterranean Sea. He armed it to the gunnels, built an airport, ringed the island with roads, and refurbished the principal port at the town of Pantelleria. Unfortunately this attracted the Allies, who bombed it ferociously, leveling the town of Pantelleria and forcing the island's inhabitants to leave and take cover on Sicily and elsewhere in Italy. The Panteschi (the plural of Pantesco), as the Pantel-lerians are called, have seen more or less the same parade of occupiers as Sicilians on the main island. The Muslims left the most visible footprints: the white-domed stone houses called dammusi, the circular stone giardini arabi ("Arab gardens") that are built to shelter citrus trees from the relentless winds, and Arabic-sounding and -looking names such as that of the contrada Bukkuràm, meaning “rich in vines.”

Pantelleria is closer to Africa than to Europe, being sixty kilometers (thirty-seven miles) northeast of the Tunisian coast and one hundred kilometers (sixty-two miles) southwest of Sicily. With eighty-three square kilometers (fifty-two square miles) of surface, it is the largest of Sicily's offshore islands. Geologically speaking, Pantelleria is an infant. Not more than two hundred thousand years ago, successive eruptions pushed lava rock two thousand feet up from an undersea plain to create the jagged and craggy rock formations that characterize the island today. Its baroque shape and black-green volcanic rocks glistening in the azure Mediterranean waters suggest its epithet, the Black Pearl. The Panteschi, some seven thousand strong, impress even Sicily dwellers with their individualism. The winegrower Fabrizio Basile crowed to me that he does not feel Sicilian at all. But although Sicilians have difficulty uniting under a common cause, when Panteschi get together the results can be explosive.

Pantelleria's name evolved as its occupiers came and went, from the Punic-Phoenician Yrnm to the Greek Kòsuros or Kòssoura and to the Latin Cossura or Cossyra. The Muslims called it Qawsarah, phonetically related to Cossura. A Byzantine monastery dating from the sixth century A.D., Patelarèas or Patalarèas, is believed to be the origin of the modern name. Another theory is that Pantelleria derives from the Latin word tentorium ("tent"). It is no coincidence that on the island, the name of the walled area where grapes are laid out to raisin under an awning or sunshade is called a stenditoio con le tende ("drying area with awnings"). Beyond the mysteries of etymology, there can be no question that the drying of grapes into raisins (uve passe, the plural of uva passa) and the production of passito wines (made from dried grapes; from the verb appassire, meaning “to wither") have an ancient history here.

The passito wines of Pantelleria entered commerce in the late nineteenth century. They were even exported to England and the United States. In the early twentieth century Italian merchants sought out Pantelleria's fine raisins and sweet wines. To serve their needs, the Panteschi planted more vineyards. Vineyard surface reached its zenith in the 1920s, with more than fifty-eight hundred hectares (14,332 acres). More than three-quarters of the vines planted were Zibibbo.

Phylloxera arrived in 1928 and devastated vineyards throughout the next decade. Replanting on rootstocks began five years later, but World War II derailed progress. During and after the war the emigration of numerous Panteschi decimated the agricultural labor force. In the 1950s, vineyard surface was half that of the 1920s. Improved technology increased yields per hectare, resulting in total yields for the island that nearly achieved the levels of the 1920s. A great demand for passito wine set off a boom from 1965 to 1970. But decline set in again during the 1970s. Markets turned to seedless grapes for both eating and baking. Countries such as Greece, Turkey, and Cyprus could supply raisins at lower cost. Merchants preferred to buy dried Zibibbo grapes from Pantelleria and vinify the wine in Marsala and other Sicilian production facilities or in northern Italy. Zibibbo is another name for the variety Moscato di Alessandria. Piedmont merchants, long familiar with another member of the Muscat family, Moscato Bianco, became major purchasers and vinifiers of Pantelleria Zibibbo. Panteschi sold their best grapes to the table grape market and their best raisins to the confectionery industry. They used their worst grapes and raisins in the wines they drank. These were called ambrati, named for the murky amber of the liquid. Flaws obscured the wines’ quality.

Consistent with Muslim inheritance custom, heirs have divided land on Pantelleria for centuries. This creates a highly fractionalized pattern of land ownership. The prevalence of small land parcels makes economies of scale impossible and adds to labor costs. The island's rugged terrain also requires time-consuming and expensive manual labor. Because manufactured goods—and even drinking water—have to be shipped or flown to the island, the cost of living is higher than on Sicily's main island. Irrigation is not feasible, because Pantelleria has virtually no water resources other than its thermal springs. For all these reasons, Pantelleria wine costs more than comparable Sicilian wine. Panteschi winegrowers needed to make wines with cachet so that sophisticated and wealthy consumers would be willing to pay more for them. Their moment arrived in the 1990s, when Italians became wealthier and began purchasing more expensive wine. Celebrities, among them the Italian fashion designer Giorgio Armani and the French actress Carole Bouquet, built vacation homes on the island, bringing more attention to it. They and a growing number of other affluent tourists increasingly visited the island—if not by yacht then by plane from Palermo or Trapani or by ferry from Palermo, Trapani, or Mazara del Vallo. For this breed of wine lover, the Italian wine market provided Super-Tuscans, Barolos, Angelo Gaja wines, and Brunello di Montalcinos, but no iconic “super” sweet wine.

What Marco De Bartoli failed to achieve for Marsala, he achieved, or almost achieved, for Pantelleria. In the early 1980s he saw the potential of the island's wines and began experimenting in Marsala with raisins that he bought from a grower on Pantelleria. His first vintage of Bukkuràm, a passito, was the 1984. With it and the others that followed, De Bartoli set new standards of quality and style for Passito di Pantelleria. The name Bukkuram and the design of its label evoked the island's Arabic past. The wine was golden and clear, infused with the exotic flavors of flowers and fruits commonly associated with Arabic gardens. Its texture was smooth and syrupy, and it had just enough sourness to make a clean exit. In the same year that De Bartoli came out with Bukkuram, the Pantesco winegrower Salvatore Murana made his first Martingana passito. Both wines bear the name of the contrada where their grapes were grown.

Gabriella Anca and Giacomo Rallo, the owners of the Donnafugata wine company on the main island of Sicily, needed dessert wines to complement their range of dry wines. In the late 1980s they rented a farm on Pantelleria with seven hectares (seventeen acres) and a winery. Based on their knowledge of what consumers wanted and on the advice of Sauternes and Tokay producers, they directed their enologists to craft fresher, fruitier, and tarter versions of Pantelleria wine. They launched a passito, Ben Rye, in 1989. Its freshness and higher acidity set it apart from the Passito di Pantellerias of other producers. Donnafugata enriches the base wine of its passito with dried grapes grown at some of the higher altitudes on the island, where the harvests are later. These give higher acidity to the wine. Kabir, a Moscato di Pantelleria, came later. It is a sweet late-harvest wine made from grapes dried on the vine after fully ripening. The 2010 Kabir was about 11.6 percent alcohol, reducing its weight but enhancing its freshness. Donnafugata owns the most vineyard surface on the island. As of 2008, the company sources grapes from some sixty-eight hectares (168 acres). It also buys grapes. All told it is the second-largest producer on the island, after Pellegrino.

Before building its winery in Marsala in 1992, the Pellegrino Marsala house consulted the Sauternes expert Denis Dubourdieu about how to improve Pantelleria wine. Based on his experience with similar French products, such as Muscat de Frontignan and Muscat de Beaumes de Venise, he helped Pellegrino achieve a style of Zibibbo passito that emphasized lightness and purity. Pellegrino's Passito di Pantelleria Nes, which it sells under the Duca di Castelmonte brand, expresses this more natural style. It has hints of orange and cedar in the nose and is more viscous than sweet on the palate.

I attended a wine conference on the island in 1995. Pantelleria then seemed on the edge of fame. At the meeting, tempers flared when the discussion came to what methods should be allowed for drying grapes. Traditionally grapes dried in the open air in the sun. The DOC regulations specify this method and allow for exceptional protection of drying grapes during inclement weather. Since 1951, however, drying machines had also been in use on the island. Essentially, these are fans that blow humidity away from the harvested grapes. This is particularly important in the first few days of drying because a great deal of water evaporates from the stems then. The resulting humidity provides an ideal environment for rapid mold growth. Over the years, many drying machines with a variety of systems for controlling ambient humidity have been used. Tubular polyethylene tents (serre, the plural of serra) were introduced in the mid-1980s for all types of fruit production in Sicily. They not only sped up the rate of desiccation but also protected the grapes from inclement weather. While the drying machines were used in open air and reduced the temperature around the grapes, the tunnels increased the temperature during the drying process. At the 1995 conference, De Bartoli, then the president of the Istituto Regionale della Vite e del Vino (IRVV, “Regional Institute of Vine and Wine"), argued that the law should be changed to allow methods that were not traditional but still respected grape quality. Panteschi winemakers, however, suspected that merchants wanted this flexibility so they could industrialize production. I learned at that meeting how argumentative Panteschi can be. The current law bans drying machines but allows drying in polyethylene tunnels when weather threatens the drying process. Since there are no specific regulations determining what is and is not threatening weather, drying in tunnels is commonplace. Furthermore, the law allows tubular tents for general use as long as they have openings along the sides to let air flow through. The fractious chatter that I heard in 1995 about who was really drying grapes under the sun and who was taking quasi-legal shortcuts still occurs today.

Moscato di Pantelleria DOC and Passito di Pantelleria DOC are the vinous crown jewels of the island. The regulations governing them are similar. Both must be made from late-harvest Zibibbo dried in the sun while still attached to the vine, with some additional grapes dried off the vine. In practice, Moscato di Pantelleria is lighter and less sweet than Passito di Pantelleria. To get the extra sweetness and concentration for Passito di Pantelleria, producers add more grapes that have been dried off the vine. These contain less water, so their sugar content is higher and the compounds in their skin and pulp are more concentrated. Beyond Moscato di Pantelleria DOC and Passito di Pantelleria DOC, there is a more expansive appellation, Pantelleria DOC, which includes six wine types, from sparkling (spumante) to fortified (liquoroso). DOC regulations for all of these require bottling in Sicily. There is a long history, however, of Marsala houses in Trapani and merchants from northern Italy, particularly Piedmont, buying Pantelleria grapes and raisins and making wine according to their own specifications and needs. Well into the 1990s Panteschi winegrowers were suspicious that extra-Sicily bottling was occurring and that wines illegally labeled as Moscato di Pantelleria DOC and Passito di Pantelleria DOC were infiltrating commercial networks. They also suspected that Marsala houses were making Pantelleria wines of all types with grapes from other sources. Rumors continue. Some Panteschi have lobbied for a law that would make it obligatory to bottle all Pantelleria wines on their island. This would help ensure that such wines were made with 100 percent Pantelleria grapes. It would also encourage people to associate these wines with Pantelleria and its wine community rather than Marsala and its wine community. Current law requires all DOC wines to be vinified on Pantelleria. Producers must bottle Moscato and Passito di Pantelleria DOC wines on Pantelleria, except that certain grandfathered producers may bottle them elsewhere in Sicily. If producers wanted to change the appellation status for both Moscato di Pantelleria and Passito di Pantelleria or only the latter from DOC to DOCG, the issue of obligatory vinification and bottling on Pantelleria would become even more contentious. DOCG regulations generally obligate bottling within the boundaries of the appellation.

On the other hand, many Panteschi do not want to lose the business of Marsala merchants. The house of Pellegrino alone processes more than half the wine grapes from the island. Marsala merchants do not see how quality would increase by bottling Moscato di Pantelleria and Passito di Pantelleria on Pantelleria. It would certainly increase their production costs. They would be forced to duplicate facilities and forgo economies of scale. Plus, shipping wine in bulk is less expensive than shipping it in bottle. For these reasons, the movement among some producers to require on-island bottling has not gone far. On the other hand, Pantelleria wine law requires that the addition of distillates to liquoroso versions of Moscato di Pantelleria DOC and Passito di Pantelleria DOC occur on the island. Pellegrino, a large producer of these versions, built a vinification facility on Pantelleria in 1992 expressly to conduct this fortification. It has also continued to bottle off-island. De Bartoli and Murana too have built wineries and bottle their wine on the island. In 2006 Donnafugata built a winery inside a Pantelleria dammusi, but it had no room for a bottling line. A Sicilian company with a sizable presence on the island, Miceli, has its bottling facility off-island, in the township of Sciacca. In fact, most Pantelleria wine is bottled off-island. Notwithstanding the requirement that Moscato and Passito di Pantelleria DOC wines be bottled on Pantelleria, the law exempts those producers that had bottled such wines for at least one year in Sicily prior to its enactment to bottle such wines off-island. During our visit to Pantelleria, ex-agricultural minister Calogero Mannino, owner of Abraxas, expressed frustration with this loophole that allows off-island bottling of its two crown jewels: “La deroga è piu grande della regola!” ("The exception is greater than the rule!"). As an on-island bottler—and an architect of Italy's Wine Law 164—he knows that bottling on Pantelleria cements the identity of these wines to that of the island.

Another issue that has both history and currency is the way in which fortified Pantelleria wine negatively impacts the market for Moscato and Passito di Pantelleria. For centuries merchants have fortified wines to make them seaworthy. In 1992 Pellegrino began producing a fortified Moscato di Pantelleria. Now it produces a Pantelleria Moscato Liquoroso and a Pantelleria Passito Liquoroso under the Duca di Castelmonte brand. Miceli also produces liquoroso wine, as do several other merchants, mostly in Marsala. The production costs of fortified versions of Pantelleria Moscato and Passito DOC are much lower than those of unfortified versions. Retail prices show the difference. Sweetness levels mirror those of unfortified versions. The alcohol levels of Pantelleria Passito Liquoroso and Passito di Pantelleria are close, 15 and 14.5 percent respectively. In general, fortified and unfortified wines taste very similar. Producers of unfortified Moscato and Passito di Pantelleria are concerned that consumers cannot easily recognize the difference, though labels state liquoroso when applicable, along with the higher alcohol percentage. Pantelleria wine producers not making the liquoroso versions, among them many Panteschi, also claim that the cheaper versions are trading on the reputations of their “natural” counterparts.

At the 1995 conference, Murana and other local producers expressed hope that Panteschi could achieve something special in the wine world. This quickly erupted into heated arguments among Panteschi and between Panteschi and non-Panteschi. On the heels of that conference, some producers accused others of illegal wine sophistication. In 2004 a Pantesco winegrower made allegations to authorities against several other producers that resulted in court cases. At the beginning of 2009, eleven out of the seventeen accused were absolved. The resolution of the accusations against the other six was postponed. Not only are the island's vineyards fractionalized, but so are its inhabitants. Few Pantesco restaurants feature local wine. This demonstrates the lack of island self-determination. It is easier to make money from tourism than from agriculture or wine production. The average age of those who work in the vineyards is more than sixty years. There awaits no next generation of Panteschi winegrowers. At a meeting in 2010, Murana told me that all the hopes he had nurtured during the 1980s and early 1990s have evaporated.

Putting the problems of the Panteschi aside, their island is an exciting location for viticulture. More than fifty volcanic vents, now extinct, have formed conical hills of volcanic debris. These geologic formations are called kuddie (the plural of kuddia) or cuddie (the plural of cuddia). Their names, mostly Arabic in origin, identify the localities that surround them. Wine producers also name their wines after kuddie. In doing so, they identify the location of production. The island's many thermal springs, some of whose temperatures reach 100°C (212°F), evidence volcanic activity, which is diminishing. Its highest point, Montagna Grande, reaches 836 meters (2,743 feet) above sea level. The sharp inclines of jagged-edged volcanic rocks have forced humans over the centuries to build terraces to create cultivatable patches of soil.

The greenish black rocks that dominate and characterize the island are made of pantellerite. They have a low pH and are rich in sodium. The rocks erode into porous sandy soils. The pumice in these soils is filled with tiny cavities that absorb dew at night. Because these soils are light and soft and drain well, contact with them rarely damages low-lying vine vegetation. They are also very fertile.

Pantelleria's climate is maritime-Mediterranean, with hot summers and mild winters. The average annual temperature is 19°C (66°F). Temperatures average 11°C (52°F) in the winter and 25°C (77°F) in the summer. The island gets about three hundred millimeters (twelve inches) of rain per year spread over fewer than fifty days, mostly between November and February. July is a parched month, with an average of two and a half millimeters (0.09 inches) of rain. The island has few streams, but dry stone and gravel beds become torrents during the winter. One important factor is the wind, which blows at an average of twenty kilometers (twelve miles) per hour more than 320 days per year. Different exposures on the island are subject to winds from different directions. Winds can be very strong from mid-May to June, knocking off tender shoots and impairing flowering. The vines are dug into holes and trained low to the ground to get cover. The scirocco is feared most. Along with its winds, it can bring so much heat that the vines become comatose and the grapes wither on the vine. At Scauri, a port on the southwest coastline, Donnafugata loses one harvest in three because of the scirocco.

Zibibbo became increasingly popular from the beginning of the twentieth century. Its triple use—for table grapes, raisins, and wine—strengthened market demand. Zibibbo accounts for 90 percent of the vines planted on the island. The white grape varieties Catarratto and Inzolia and the red grape varieties Perricone and Alicante (Grenache Noir) make up most of the balance. Alberello pantesco is the training system of tradition and choice. On the wind-shielded plains of Ghirlanda and Monastero, some row training on wires is employed.

The normal harvest begins during the second decade of July and ends during the last decade of September. There is a small second harvest in October, of buds on secondary shoots (femminelle, the plural of femminella). The small bunches (about ten grapes each) of tart, low-alcohol grapes (racemi, the plural of racemo) yield a refreshing table wine consumed locally. The earliest-harvested grapes are reputed to make the best passito wines. They come from the warmest areas, at low elevations and close to the sea. These grapes have higher sugar and are in perfect condition. The weather remains sunny, hot, and dry for the drying period, from the first harvest in early August to the end of September. The yields at such sites, however, are low, about forty-five quintals per hectare (4,015 pounds per acre). Higher and cooler sites make better dry table wine. The highest vineyards on the island are at about four hundred meters (1,312 feet) for white grapes and three hundred meters (984 feet) for red grapes.

If it takes the same amount of grapes to make five bottles of normal dry wine as one bottle of Passito di Pantelleria, where does that missing volume go? Water vapor escapes through the drying grape skins, concentrating all the other grape constituents. Traditionally winegrowers laid out the grapes on mats or nets in an area (stenditoio) enclosed by walls. The walls collect heat, raising the ambient temperature by about 10°C (18°F). The drying process is faster at higher temperatures. The faster it is done, the less chance there is that the insects, weather, mold, or other factors will compromise the raisins. Many producers cover their grapes at night to protect them from nighttime humidity and dew. An awning or other covering at the ready also serves to protect the grapes from inclement weather. Drying grapes have to be monitored carefully. Just as a chef flips an egg in a frying pan, a winegrower must turn over each bunch regularly, to ensure even drying and to check for fungus. During the drying period a stenditoio smells like hot apple pie.

There are two degrees of drying, passolata and passa Malaga. Passolata grapes are semidried, spending one to two weeks under the sun. Twenty-five to 40 percent of their juice is sugar. The little juice still inside the berry is just enough to macerate the skins in and to vinify the skins and juice. Passolata grapes look as wizened as Amarone grapes. The processes for drying them are similar to those used in the Veneto region for Amarone production. After three to four weeks of drying, fresh grapes become fully dried raisins, called uva passa Malaga. Though they are soft and pliable, they do not contain enough liquid but must instead be either soaked in juice or wine or tossed into a fermenting must for maceration. Aromatic compounds are at peak concentration at this point. Further drying decreases the aromas. Grapes can be dried for as long as three to four weeks, at which point 55 percent of their syrup becomes sugar. After such extreme drying, grapes are one-quarter of their original weight. During the drying process, aromas transition from orange and muscat to dried figs and dates.

Though the Pantelleria climate is rather steady, there are still occurrences that can alter the quantity and quality of the harvest and drying periods. Excessive drought in 1982, 1988, and 2003 reduced yields. In 1996 and 2007 downy mildew decimated yields. It can occasionally rain during the drying period. Francesca Minardi of Azienda Vinicola Minardi told me that rain during the drying period in 2004 forced her to vinify her drying grapes sooner than planned.

Using serre reduces the drying time dramatically. These enclosures intensify the heat. Three to four days is sufficient for passolata and seven to eight days for passa Malaga. By law, producers may use serre with air vents, whose drying period is longer than that of unvented tents but shorter than drying in open air. It is easy to understand why many producers use these enclosures. Another way to speed up the process is to first immerse grapes in hot water mixed with caustic soda. The bath removes their bloom, thus speeding up the evaporation of the juice. However, this also reduces aromatic compounds. The skins of grapes treated this way appear paler, hence their name uva passa bionda, meaning “blond dried grape.” The DOC does not allow this use of caustic soda.

Though machines can destem the harvested grapes, this grows increasingly difficult as they become more raisined. Traditionally women destemmed raisined grapes while sitting around a large table. By hand is still the commonest way to destem uva passa Malaga.

The traditional method of making Passito di Pantelleria is to add uva passa Malaga to fresh Zibibbo grapes in fermentation. This is very similar to how Hungary's sweet Tokaji Aszú wines are made. The raisins add flavor and sugar. When fermentation reaches the desired residual sugar and alcohol levels, the wine is drained and the skins pressed. There are, however, many different options that Pantelleria winegrowers can use to alter the process and the end result. Passolata grapes can be used. Some producers cold-macerate harvested grapes for up to three weeks. Some winegrowers rehydrate the paste of the fermented skins in wine and then press it to extract more fruit sugar, which they add back to the fermenting must or wine.

After fermentation the sweet wines are clarified and stabilized using static cold sedimentation aided by fining agents. Before bottling they are usually sent through diatomaceous earth filters. During these processes, concrete, stainless steel, fiberglass, or oak barrels are used as containers. Concrete vats exist in older wineries. If they have no cracks, they can be excellent containers. Stainless steel tanks are easiest to clean, and micro-oxygenation can reduce their tendency to give wines pungent, vegetal smells. Fiberglass tanks are more common on Pantelleria than in other wine-producing zones. Concern about styrene, a hazardous chemical, is reducing their use. Large oak barrels generally have been phased out. They are too difficult to keep clean. Some producers use a percentage of new, small-format barrels in their mix of maturation vessels. These give flavor and oxygenate the wines somewhat. Most producers do not mature their sweet wines for long periods after fermentation. De Bartoli, on the other hand, matures Bukkuram in used barriques for two years before bottling.

Because Moscato di Pantelleria and Passito di Pantelleria are not only the island's most prestigious categories but also its most widely recognized throughout the world, I have focused this discussion on them. The Passito is darker, golden amber, with a strong scent of raisins, dates, and dried apricots. The Moscato is more golden and has some fresh apricot aroma mixed in with the dried. It also has some floral scents. The Passito is more viscous, sweet, and alcoholic than the Moscato. Moscato Liquoroso and Passito Liquoroso lack the concentration of the unfortified versions. They are available in many markets, and consumers interested in understanding Pantelleria wines should be aware of the difference.

Murana, the island's most famous native wine producer, makes an aromatic dry wine, Gadì, from Zibibbo racemi that he collects in October from several sites. His farm center is at Mueggen, which he calls “an island within an island.” It is an isolated plateau in the interior at an altitude of four hundred meters (1,312 feet). Here Zibibbo is harvested in mid-September, several weeks later than at his other sources. These grapes are used in Turbè, a light Moscato di Pantelleria whose sweetness is balanced by its 13 percent alcohol. Mueggen and Khamma are both Passito di Pantellerias that move the alcohol and the sweetness up a degree. Martingana is a single-vineyard wine from the southeastern coast. The vineyard was planted in 1932. The old vines there can ripen their grapes in the area's extreme warmth of August. Murana selects the best grapes from this vineyard and dries them outdoors for thirty to forty days.

Three artisanal producers, Salvatore Ferrandes, Fabrizio Basile, and Salvino Gorgone, each farm several hectares and make tiny quantities of wines. Ferrandes, whose father also grew grapes and made wine, is building his own winery and will be installing a bottling line. His wines are concentrated, very sweet and viscous, and loaded with the smell of honey and dates. He was proud to tell me that they contain 170 grams per liter (twenty-three ounces per gallon) of sugar; the minimum by law is 110 grams (fifteen ounces per gallon). He says that for every Passito di Pantelleria he makes, he could make five bottles of dry wine. To help fund his passito production, Ferrandes grows, harvests, and sells the island's prized capers. During my visit, his teenage son Adrian accompanied him and demonstrated a genuine appreciation for the fruit that his father grows. Time will tell if he will be in the next generation of this vanishing breed. Basile is also the son of winegrowers. His grandfather too was a grape grower. His father helped Basile set up his winery, where he also intends to create a small restaurant. His Shamira Passito di Pantelleria 2007 is delicate and light. Gorgone, like many Panteschi winegrowers, has another job that helps support him, one that serves the brisk tourist trade. He is a builder. He farms only three hectares (seven acres). His wines have a pure, fresh, and lively taste, the hallmarks of the modern style. He has a brand-new winery, Dietro L'Isola, but uses another facility on the island for bottling.

Abraxas espouses a style somewhere between those of Donnafugata and Murana. Its Passito di Pantelleria is very spicy. Scirafi, the Abraxas second-tier Passito di Pantelleria, is based on first pressings, rather than the tarter, more delicate free-run juice, and on the addition of less-dried grapes during vinification. The former Italian agricultural minister Calogero Mannino, famous for his advocacy of the Italian (and Sicilian) wine industry, established Abraxas in 1999 as an oasis where he could escape the intrigues of the political world. Abraxas has twenty-six hectares (sixty-four acres) of land, making it one of the largest growers on the island. Four hectares (ten acres) are in the contradas of Bukkuràm and Scirafi at 125 meters (410 feet), a warm site ideal for making Passito di Pantelleria. Twenty-two hectares (fifty-four acres) straddle the Mueggen and Randazzo contradas. These vineyards are at three to four hundred meters (984 to 1,312 feet) in one of the coolest sites for viticulture on the island. The vineyards here are sizable and flat, allowing for wire training and some mechanization. Beyond its Passito di Pantellerias, Abraxas makes a dry white wine and several red wines. The white is Kuddia del Gallo, a 70 percent Zibibbo, 30 percent Viognier blend. It combines the exotic smells and fat, rich, slightly bitter tastes of both vine varieties. Abraxas is the island's red wine leader in quantity and quality. My favorite is Kuddia di Zè, a blend of 50 percent Syrah, 30 percent Grenache, and 20 percent Carignan.

Due to the high cost of production and the paucity of land suitable for still dry wine production on Pantelleria, it is unlikely that we will see many dry wines from there on the international market. The first such was De Bartoli's Pietranera, first released in 1990. This dry, cold-fermented Zibibbo remains the reference point for varietal Zibibbo. Giacomo Tachis believed that Pantelleria could produce top-quality red wines. At the 1995 conference, he told me that while the north of Italy made tart and hard-textured wines that needed long aging in barrique to soften, the Pantelleria climate could achieve suppleness without barriques. He pointed to the sunny sky: “That is Pantelleria's barricaia [a maturation room containing barriques].” Tachis thought that the ultimate skin ripeness achievable in Pantelleria's cooler zones could naturally produce deeply colored, rich, supple red wines. He suggested the use of Carignan, based on his experience with the variety in the similar growing environment of Sardinia. Varieties introduced into Tunisia during its French colonial period could be a source of vine wood for producers interested in making Rhone-style wines, which the Italian wine industry has not mastered. I hope that Abraxas's red wines move in this direction. Its high-altitude site, its state-of-the art boutique winery, built in an isolated Italian army barrack from World War II, and the combined expertise of its consultant Nicola Centonze and full-time enologist Michele Augugliaro are assets that can help it achieve this feat.

On Pantelleria we find both winegrowers and entrepreneurs. Will there be a next generation of native winegrowers? What is likely is that outside wealth will create boutique estates that present the mystique and the image but not the reality of the Pantesco winegrower. That wealth, though it may preserve the wine, will not represent its spirit. Murana told me that Pantelleria wine production is becoming “a sport of the rich for the rich.”

Other recommended producers and their wines:

Cantine Rallo Passito di Pantelleria

Carole Bouquet Sangue d'Oro Passito di Pantelleria

Case di Pietra Niká Passito di Pantelleria

D'Ancona e Figli Cimillýa Passito di Pantelleria

Miceli Entellechia Passito di Pantelleria

Miceli Yanir Passito di Pantelleria

Serragghia di Giotto Bini Moscato di Pantelleria

Solidea Passito di Pantelleria

MARSALA

A century troubled by two world wars and one Great Depression did little to support Marsala, a product that depends on international trade and economic stability. After World War II, Marsala producers increasingly combined their wine with the flavors of nuts, fruits, spices, and eggs to attract more customers with different tastes. Food industries and consumers purchased these “Marsala"s for culinary preparations and for the enhancement and preservation of various foods. The popularity of the so-called Marsala Speciali caused the image of Marsala to transition from sophisticated beverage to commodity product indirectly consumed as an ingredient. The most challenging problem that Marsala—like Sherry and Madeira, its two prototypes—has faced has been the shift in consumer tastes from oxidized fortified wines to fruity table wines.

The market deterioration has been dramatic. As of 1921 there were about fifty enological companies in Marsala. After World War II there was a proliferation of Marsala companies, mostly small, that capitalized on commercializing the wine and priced it so as to undercut the established Marsala houses. By 1950 there were 226 such operations. By 1970 about a hundred Marsala producers remained. There were only fifteen in 2010, when a bottle of Fine Marsala could be purchased for as little as one and a half euro. The final slap was the “Is Marsala a bluff?” debate that took place on a Sicilian wine blog, “Cronache di Gusto,” from April to June 2010. Will Marsala survive?

Though John Woodhouse modeled Marsala after Madeira, Benjamin Ingham moved its style more toward that of Sherry. He incorporated Sherry techniques such as maturation by solera, a system that homogenizes wine quality and style by systematically blending younger with older wine. As with Sherry, in Marsala production, grape spirit is added to a fully fermented dry white wine. Though red grapes were used to make ruby Marsalas during the nineteenth century, and though the 1984 revision of the Marsala production disciplinary reinstated a ruby version, rubino, made mostly with red grapes, Marsala is largely a fortified white wine. Before the mid-nineteenth century the triad of Catarratto, Inzolia, and Grillo dominated Sicilian vineyards. Inzolia proved to be too vulnerable to powdery mildew, which attacked in the mid-nineteenth century. Grillo largely took its place until the end of the nineteenth century. Grown in alberello, Grillo grapes are harvested when their sugar is high and can be naturally vinified into 14 to 17 percent alcohol wines. From 1900 to 1920, when phylloxera necessitated the replanting of vineyards, farmers opted to plant the higher-yielding Catarratto instead of Grillo. Catarratto produces lower-alcohol wines than Grillo. Rectified concentrated grape juice can be added to Catarratto musts to increase the base wine alcohol degree. More grape spirit can to be added to fortify the wine. Purists perceive this greater reliance on added grape sugar and spirit as a move away from connection to place and toward a concocted industrial product. Catarratto wine tends to oxidize rapidly, darkening as it does so, but this is just what Marsala producers want, particularly for the styles identified by the word ambra ("amber"). To encourage oxidation even more, they splash the base wines in open air during the racking process. After World War II, the quality of Marsala's base wines deteriorated. Since 1984 the white variety Damaschino has been allowed in Marsala production. Its high yields and low-alcohol wine do not endear it to purists.

Once they have made and blended the base wines, Marsala producers add grape spirit to make Vergine. This, the purest type of Marsala, has no other additions. To the Fine and Superiore styles, producers can add coloring and flavoring products. Fine and Superiore evolved when early Marsala producers needed to adjust the appearance, smell, and taste of immature Vergine to suit the preferences of a buyer. Brand names originally devised for particular markets became the internationally recognized names for styles of Marsala, for example Italy Particular (IP), Superior Old Marsala (SOM), London Particular (LP), and Garibaldi Dolce (GD). Each producer has its own recipes for styles and brands, and every one must satisfy the Marsala DOC regulations. Each recipe, called a concia, prescribes additions of grape spirit, sifone ("sweet fortified wine"), mosto cotto ("cooked must"), and rectified concentrated grape juice. Before a producer blends in these additions, he must declare to regulatory authorities which lots will become what regulated types of Marsala. Changes to this declaration cannot be made. Hence a wine declared as a Fine must remain a Fine even if it matures for many years in barrel without additions, like a Vergine. When they add grape spirit, producers must take into account the concentration or dilution that other additions and evaporative rates during maturation will cause. Before bottling they can make a final spirit addition to meet the 17 percent alcohol by volume minimum required for Fine and the 18 percent minimum for other styles.

Understanding the various ingredients of the concia is essential to understanding what makes Marsala. To make sifone, also called mistella, spirit from late-harvested grapes is added to fermenting grape juice, cutting its fermentation short. Sifone provides sweetness and a syrupy texture. During Marsala maturation, it also enhances the development of specific aromas. In Marsala Superiore, the percentage of sifone in the concia is greater than that of the dry base wine, perhaps even double it. Sifone accounts for the greatest percentage of constituents in the dolce version of Superiore, particularly the type labeled oro ("golden"). Mosto cotto provides another range of aromas, similar to burned sugar or caramel. Its principal function, which purists look down on, is to tint Marsala dark brown, a hue that could otherwise be achieved by long maturation in barrel. Mosto cotto is principally used in Marsala labeled ambra. Rectified concentrated grape juice can be added to fine-tune the sweetness and viscosity of Marsala. Purists frown upon it too. By law, sifone, mosto cotto, and spirit used in Marsala must be derived from grapes grown in the Marsala DOC.

The difference between Fine and Superiore is maturation time. A Fine needs to mature one year, the first four months of which may be in a nonwooden container. For the eight remaining months, the container must be wooden. The Superiore must age at least two years in wood. There is a longer-matured category of Superiore, Superiore Riserva. It must mature in a wooden container at least four years before being bottled. For all Marsala styles, oak and cherry are the two wood types allowed. The barrels are never entirely filled. This allows a steady oxidation of the wine. A cool, somewhat humid, and dark environment is best for maturation. Fine, Superiore, and Superiore Riserva can also be labeled to indicate color: oro for golden, ambra for amber, and rubino for ruby. The labels for residual sweetness level are secco (dry, less than forty grams per liter [five ounces per gallon]), semisecco (semidry, between forty and one hundred grams per liter), and dolce (sweet, more than one hundred grams per liter [thirteen ounces per gallon]). Fine and Superiore labeled ambra must contain at least 1 percent mosto cotto. Fine and Superiore rubinos must have at least 70 percent Pignatello (a variety called Perricone in the Palermo area), as well as Nero d'Avola or Nerello Mascalese.

If the producer were to add only grape spirits to the base wine and then age it for at least five years, he could release it as a Vergine. After five more years he could release it as a Vergine Riserva or Vergine Stravecchio. If producers use the solera maturation system, then they can print Vergine Soleras or simply Soleras on the label. In a solera system, younger wine systematically replaces older wine that has been removed from barrels for bottling or further blending. Thus Soleras do not carry a vintage year, whereas some Vergines do.

Marsala Vergine should be pale gold, with an intense nutty nose accented with citrus. In the mouth, it should be soft and savory. Dry Oloroso Sherry has a bitter finish that Marsala Vergine does not. Unfortunately, a minuscule amount of Vergine is produced. As of 2010, Marsala Vergine accounts for only 0.7 percent of production, while Marsala Superiore represents 18.6 percent, and Marsala Fine has the largest share, 80.7 percent.1 Vergine wines can be splendid. Some develop a rancio or leathery smell with age. Some tasters like this smell. Some do not, me included. The clean smell I prefer may be less exotic than one with a rancio character, but for me it is more pure. In general, the more Grillo in the blend of a Vergine, the paler the color, the spicier and nuttier the smell, and the more viscous and finely astringent the texture.

If a specific year appears on a wine that says Soleras on the front or back label, it must refer to something other than the age of the wine. Some houses use their founding year as part of the branding on the front label. Examples are Pellegrino 1880 and Intorcia 1930. If aging in barrel exceeds the minimum amount required by law, producers sometimes specify so on the label. Ten years is the minimum aging period for the Vergine Riserva category. A wine labeled Vergine Riserva 20 anni has had an additional ten years of maturation.

The government revised the Marsala wine production regulations and labeling in 1984. The new law, referred to as 851, attempted to restore tradition to Marsala. After World War II, Marsala merchants sourced grapes from beyond the borders of the province of Trapani, in the provinces of Palermo and Agrigento. The new law restricted such sourcing to the province of Trapani, excluding the township of Alcamo, Favignana (one of the Egadì Islands), and Pantelleria, all in the province. In addition, Marsala wine had to be produced and bottled within the new boundaries. The law also restricted the use of cooked must and, most important, banned Marsala Speciale, the Marsala flavored by spices, fruits, and so forth that had gained popularity after World War II. One popular egg, or zabaglione, style that used to be known as Marsala all'Uovo had its supporters even among expert tasters. It was left in the disciplinare as cremovo zabaione vino aromatizzato or cremovo vino aromatizzato, with a requirement of at least 80 percent Marsala. The word Cremovo, not Marsala, dominates the front label of such wines. Products with 60 percent or more Marsala may have the phrase Preparato con l'impiego di vino Marsala ("Prepared with the use of Marsala wine") on their label. If made with less than 60 percent Marsala, the product may still list the wine among the ingredients. These and other changes helped put Marsala back on a more traditional track.

Periodically wine journalists criticize the Marsala houses for the low quality of Marsala wine and the continually worsening image of the industry. Many have been the remedies proposed to restore the industry to good health. Some suggest decreasing the legal yield limits (presently one hundred quintals per hectare [8,919 pounds per acre] for whites and ninety quintals per hectare [8,028 pounds per acre] for reds), raising the minimum alcohol levels allowed for base wines, and banning the use of cooked and concentrated must. Some say producers have chased the low-cost Fine market at the expense of developing the traditional and quality side of the industry. Most Fine is sold to the food industry expressly for flavor enhancement and preservation. But if quality were higher across the board, would more Marsala be sold? Unfortunately, current consumer flavor preferences limit any possible improvement in the market. Marsala was conceived for a world without refrigeration, in which the need for asepsis was not widely understood and transportation challenged the stability of what was purchased. The world has changed. Although most of the fruits and vegetables in our supermarkets now come from thousands of miles away, they are still fresh when we buy them. Modern consumers regularly appreciate the flavors of fresh fruit. They prefer fruity to oxidized wines.

The Marsala industry as a whole should not try to remake its image. Unless the world drastically changes, a remake will not succeed. The core identity of Marsala must be preserved, just like our finest art and historical monuments. That core identity comes from the Marsala of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, when Vergine was its defining style.

Though Woodhouse fortified his Marsala and subsequent wine law has obligated fortification, there is no reason why it should not be optional. Pre-1960s wine producers in Sicily regularly produced wines with between 14 and 17 percent alcohol. The crucial factors that made and still make this possible are Grillo, alberello, and Marsala's warm, dry, and windy climate. Cellar maturation in dry conditions raises the alcohol content even higher. The minimum alcohol percentage at bottling for Marsala Vergine should be set lower, at 16 percent, to allow for unfortified versions bearing a new Marsala Vergine DOCG label. Producers of the Marsala Vergine DOCG would be required to state whether the wine was fortified or not. If fortification were an option, not a rule, those producers who wanted to challenge themselves by forgoing fortification could point the way toward a Marsala that more truly represented and featured the wine of origin. Unfortified Marsala Vergine would bring Marsala back to its pre-Woodhouse, genuinely Sicilian roots.

Casano (founded 1940).This small family-run house has vineyards that supply 50 percent of the grapes needed for its Marsala and three table wines. Third-generation siblings Francesca and Francesco Intorcia are breathing new life into the company. The smart design of its website demonstrates how Marsala could better present itself to the world.

Florio (founded 1833).The ILLVA di Saronno drinks group, which has owned Florio since 1998, purchased the Duca di Salaparuta winery in 2001. ILLVA consolidated both companies into Duca di Salaparuta, retaining the facilities and brands of each. Florio is now an umbrella brand for Marsala made by the Duca di Salaparuta company. The labels use the branding Cantine Florio 1833. These wines mature at the Florio baglio, seaside at Marsala. The quality of Florio Marsala has remained stable through these transitions. Florio, like other Marsala producers, has a range of branded products, including Marsala, fortified wines, and wines from the islands of Pantelleria and Salina. It sources the grapes for its Marsalas from along the coast, just like the early Marsala industry. Moreover, Florio bases the blends for its Marsala Superiore Riservas and Vergines on Grillo grown in alberello. They age for eight years in oak barrel. Their pale golden color, clean nutty bouquet, and rich, savory palate are characteristics of the pure style that I appreciate most. These Marsalas are pure, solid, and elegant. Florio makes two excellent Vergines, Terre Arse and Baglio Florio. The Donna Franca Marsala Superiore Semisecco Ambra, matured for fifteen years, blunts the spice and power of the Vergines with an edge of sweetness.

Marco De Bartoli (founded 1978).Born into the elite Marsala merchant world, the mercurial Marco De Bartoli raced cars during the 1970s while working at the Pellegrino and Mirabella Marsala houses. Warned by scrapes with disaster on the roads and disillusioned with how the Marsala industry chased profits rather than quality and identity, he retired to take the reins of his family's farm at Samperi. While Marsala houses were going out of business in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he was buying up the finest reserves, creating a collection that would give his Marsala that je ne sais quoi of character. He was the most outspoken supporter of the Grillo variety. His most controversial wine (there were many controversies that swirled around him) was Vecchio Samperi Ventennale 20 anni. It was 100 percent Grillo. He kept his yields so low (twenty hectoliters per hectare [214 gallons per acre]) that his base wines naturally reached about 16.5 percent alcohol. After twenty years in a solera system, which raised the alcohol level through the evaporation of water from the wine, the wine was bottled at roughly 17.5 percent alcohol without the addition of grape spirits. Because the alcohol percentage was less than the legal minimum of 18 percent, De Bartoli was not allowed to label this wine as a Marsala but as a vino liquoroso (which was not true, since it was never fortified). Because Vecchio Samperi was 100 percent wine, it represented the terroir more truthfully than any Marsala could. It also was closer to the type of wine, vino perpetuo, that the inhabitants of Marsala made before the arrival of John Woodhouse in 1773. In the summer of 2010 De Bartoli told me, “A good wine must have an alcohol grade high enough to age well. There need to be good vineyards. But since 1963 the law permits the possibility of making Marsala from grapes that would make a wine of about 8 percent alcohol. This makes shit, big shit. It cannot age. In 1980 I first released Vecchio Samperi. This was a real Marsala, but I was not allowed by law to identify it as Marsala on the label. The wines were very well received. Despite the great reputation of Vecchio Samperi, it was not easy to sell. I sold very little because of the reputation of Sicily, of Marsala, and of Pantelleria. However, I am not of Sicily, Marsala, or Pantelleria. I am De Bartoli, who makes Samperi and Bukkuram. This is the moral of the fable. I am a producer of quality wine, not Sicilian wine. I went outside and they treated me as if I were an outlaw. I had a sack of problems and they made a party out of it. But it does not bother me. To live in Sicily is not easy.” In March 2011, De Bartoli died at the age of sixty-six years. He was an artist working in the world of business and politics. His two sons, Renato and Sebastiano, and his daughter, Josephine, are now in charge of the family business.

Martinez (founded 1866).Fifty percent of the production of this small, family-owned house is Marsala. The other half is other types of fortified wines. The company owns no vineyards, preferring to buy base wine. Its Marsala wines emphasize purity and delicacy. The Vergine Riserva “Vintage 1995” is pale, with a delicate nose of dried fruits and orange rind and a delicate though persistent finish. Paler still and so complex in the nose (strong toasted hazelnut smells) that it seems to be sweet when it is in fact dry is the Exito, Vergine Riserva 1982.

Pellegrino (founded 1880).The house of Pellegrino, officially Carlo Pellegrino & C., experienced great growth in the 1930s. It adapted to the difficult Marsala market of the 1980s by establishing a line of table wines. It is a big and dynamic family-owned operation. About 40 percent of the wines it releases are Marsala, an enormous commitment considering the market. The Marsala wines are labeled Cantine Pellegrino 1880. About one hundred of its three hundred hectares (247 of 741 acres) of vineyards are dedicated to Marsala production. The balance principally supplies its Duca di Castelmonte line of unfortified wines. The Riserva del Centenario 1980 that I tasted in 2010 was an exotic Vergine, amber-red, with smells of dried fruits, nuts, and cedar and a rich, full palate. The Superiore Riserva Grillo had a pure nutty, caramel taste. Pellegrino makes a dependable line of Superiores.

Other recommended producers and their wines:

Cantine Buffa Marsala Superiore Riserva Ora Dolce

Cantine Buffa Marsala Vergine

Cantine Intorcia Marsala Vergine Soleras

Cantine Rallo Marsala Soleras Vergine 20 anni

WESTERN SICILY

I have defined this wine zone so that it roughly corresponds to the one authorized to make Marsala. In the western coastal lowlands running from the town of Trapani to Sciacca, the climate is hot and arid, with winds blowing off the Mediterranean Sea. Along the coastline the breezes are cooling and provide humidity to the soil and vines. It is sunny for an average of 250 days a year here. During all but the winter months, there is very little rainfall along the coast. In many spots this plain is densely planted to vineyards. Woodhouse most likely sampled wines from the Birgi Vecchi and San Leonardo contradas along the coast just to the north of Marsala. He later sourced most of his grapes from the township of Petrosino, halfway between Marsala and Mazara del Vallo. Locals connect Petrosino's potential for great Grillo with its unusual subsoil, sciasciacu, in which marine fossils are embedded in calcareous detritus. In particular, the contrada Triglia Scaletta has a reputation for fine Grillo. The best soils for Grillo are loose, porous, and low in fertility, with a moist calcareous crust, rich in mineral salts, underneath. Coastal areas are also ideal for Grillo because it thrives in the sun and heat. The salt in the air and the subsoil gives Grillo wine a sapid taste. Many of the best vineyards along the coast have terra rossa topsoils. Patches of this red soil blanket the comunes of Castellammare del Golfo, Marsala, Petrosino, Mazara del Vallo, and Campobello di Mazara.

To the east the elevation of rolling hills increases steadily up to the highlands that extend from Mount Erice in the north to Castelvetrano, northwest of Menfi, in the south. Mount Erice, rising to 750 meters (2,461 feet), condenses much of the humidity borne on winds coming off the Tyrrhenian Sea. Its hillsides have the highest rainfall in Western Sicily. Lower elevations are very dry. Thankfully there is subterranean water available for irrigation. To the immediate northwest of the centrally located town of Salemi, vineyard altitudes range from four to six hundred meters (1,312 to 1,969 feet). In the vicinity of Salemi, the soil tends to be calcareous clay, rich in potassium but poor in nitrogen and available phosphorus. The deficiency of nitrogen and phosphorus slows growth, leading to low-alcohol wines. Interior hilly areas in the comunes of Buseto Palizzolo, Calatafimi, Fulgatore, Gibellina, and Partanna have similar soils. Clay soils become hard during dry spells and crack open. The surface they form needs to be constantly broken up. Easier to farm are the loose and fertile terre brune, "brown soils,” in the comunes of Balata di Baida, Buseto Palizzolo, Fulgatore, Poggioreale, and Salaparuta (not to be confused with the firm Duca di Salaparuta).2 At the higher elevations common in the interior hills, rainfall is higher and the clayey soils absorb water, making them cool and moist throughout the summer. In addition, winds rising up the hills release their moisture to vines as morning dew. The principal variety planted here is Catarratto, which produces a high-acid, moderate-to-low-alcohol wine. Chardonnay grown here has given good results. Fessina, an estate based at Rovittello on the north face of Etna, sources Chardonnay grapes from a vineyard it owns at Segesta, about twenty kilometers (twelve miles) north of Salemi. This vineyard faces northwest and is at six hundred meters (1,969 feet) on rocky, calcareous clay soil. The wine Nakone, one of the finest Chardonnays made in Sicily, matures on its lees for five or six months with no new-oak contact. Franco Giacosa sourced Inzolia from Salemi for the Duca di Salaparuta wines of the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Duca di Salaparuta continues to source Inzolia from this area and has purchased an estate here, Risignolo, as a source for Kados, its 100 percent Grillo wine. The eastern edge of the Western Sicily zone is near the comunes of Poggioreale, Gibellina, and Salaparuta. These townships lie between the Freddo and Belice Rivers in the upper Belice Valley.

Catarratto Comune accounts for about 40 percent of the vines, of both red and white varieties, in the province of Trapani. The other white varieties, in order of most to least planted, are Grillo, Grecanico, Inzolia, Catarratto Lucido and Extralucido, Trebbiano Toscano, Chardonnay, Zibibbo, Pinot Grigio, Viognier, Damaschino, Malvasia Bianca, and Sauvignon Blanc. In the 1930s, Grillo occupied about 60 percent of the vineyards near the coastline. Now it is rare, particularly inland. Catarratto Extralucido is found more in the interior, particularly in the Alcamo area. Its high acidity results in a very tart white wine. The red varieties, from most to least planted, are Nero d'Avola (more than 7 percent of the vineyard area), Syrah, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Frappato, Nerello Mascalese, Petit Verdot, Alicante Bouschet, and Perricone. Most of the Nero d'Avola was planted in the 1990s. No one red variety has excelled in Western Sicily. Historically Perricone was the most important red variety in the zone, but it has become rare. Together with Carignan, also very rare, if existent at all, in Trapani now, it was the base of the red blend for vini da taglio, red wines, and rosatos.

There are several DOCs in this sizable zone. The operatic-sounding Delia Nivolelli is an appellation for various wine types using various vine varieties. Its basic rosso focuses on Nero d'Avola, Perricone, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, and Sangiovese. Its bianco has a more indigenous blend, featuring at least 65 percent Grecanico, Inzolia, and Grillo. Then there are varietal wines, which must meet the 85 percent variety minimum imposed by the DOC. The Delia Nivolelli DOC encompasses a large area, nearly surrounding the town of Marsala but not including it. In 2004 the Erice DOC superseded the Colli Ericini IGT. Some of this DOC's vineyard sites are on the slopes of Mount Erice close to the sea, but the appellation reaches well inland to the south, halfway down the island, overlapping the Delia Nivolelli DOC. In general, because of the high altitude of the vineyards in the appellation, between 250 and 500 meters (820 and 1,640 feet), Erice DOC wines tend to be lower in alcohol and higher in acidity than other western coastal wines. While Erice Bianco requires at least 60 percent Catarratto in its blend, Erice Rosso requires more than 60 percent Nero d'Avola. The DOC also features a wide range of indigenous and international varietal wines in a plethora of styles. The western edge of the Alcamo DOC creeps over the Freddo River. This appellation is described in the Palermo Highlands section below. The Salaparuta DOC lies in the upper Belice Valley at the eastern limit of the Western Sicily zone. At least 65 percent of its bianco must be Catarratto, while the same minimum of Nero d'Avola is prescribed for its rosso. Most of the wines in Western Sicily have been bottled and released to the market under the regionwide Sicilia IGT.

Tasca d'Almerita buys nearly all the grapes grown on Mozia, just north of Marsala in the lagoon along the coastline. This island is the site of an ancient Phoenician city and trading outpost. Shards of Phoenician pottery are so common in the vineyards that they make up part of the topsoil. The island is just offshore from Birgi Vecchi and San Leonardo. Tachis selected budwood from very old vines for these vineyards when they were replanted on rootstocks about a decade ago. Tasca d'Almerita buys its grapes from the Whitaker Foundation, which was established by Joseph Whitaker, a descendant of the nineteenth-century Marsala producer Ingham. The foundation administers the island and cares for its archeological treasures. Harvested grapes are loaded into small boats and transported to Sicily's shoreline. Trucks transfer them to Tasca's facility in Vallelunga for processing. The wine Mozia is 100 percent Grillo. It is light and soft with a salty finish. The vines need more age to produce more-concentrated wine. On the island of Favignana farther to the west, in the Egadì Islands, Firriato has a five hectare (twelve acre) experimental vineyard, in which it has planted Grillo, Catarratto, Perricone, and Nero d'Avola.

Across Western Sicily a high percentage of the grape crop is consigned to cooperatives. Along the west coast are the larger ones, particularly Colomba Bianca, Cantine Europa, and Cantina Sociale Birgi. Many retirees and elder professionals farm small plots of land and sell their grapes to cooperatives. The cooperatives principally sell juice and wine in bulk but are increasingly bottling it as they attempt to move away from the bulk market. Many of the other wine companies in the area are Marsala houses that have diversified into bottled unfortified wine. Merchant-owned and cooperative wineries have long dominated Western Sicily. Given the history of wine production and the great surface area dedicated to vineyards here, it is unfortunate that there are not more small and medium estate wine companies in the area to own vineyards, make wine, and commercialize it.

Barraco.Seven kilometers (four miles) from the sea in the township of Marsala, Nino Barraco makes fifteen thousand bottles of artisanal wine a year. One is a five-day skin contact Grillo white wine. Tasted at Vinitaly 2012, the 2010 smelled of almonds, hazelnuts, and diesel and had a salty tang in the finish. A thirteen-day skin contact dry Zibibbo was darker, with a strong floral and citrus nose and an astringent and bitter mouth. Barraco also makes a pale Pignatello (Perricone) that supports my experience throughout Sicily that there are at least two biotypes of Perricone used there: one for dark, astringent wines and another for paler, less-astringent ones. His best red wine was a 2010 Nero d'Avola. It was dark and had a strong bouquet of cherries, watermelon, and chocolate and a ripe, alcoholic, and astringent mouth. The 2006 Milocca is a passito Nero d'Avola. Its cedary cherry cough syrup nose leads into a sweet but astringent Port-like palate.

Caruso & Minini.Though the Caruso & Minini winery is in a renovated hundred-year-old baglio in the city of Marsala, its 120 hectares (297 acres) of vineyards are in a spot in the hills between Marsala and Salemi at about 350 meters (1,148 feet) in elevation. In 2004, Mario Minini combined his business expertise managing a winery in the north of Italy with Stefano Caruso's dream to give flavor to the grapes that his family had been growing and selling to merchants for more than one hundred years. Other Minini and Caruso family members help out. According to Stefano, the focus of the wines is purity of flavor. The texture of the 2011 Grillo Timpune that I tasted in April 2012 was round but tactile. It had fermented for ten days in five-hundred-liter (132-gallon) oak and acacia barrels and then been left on the lees. The 2011 Cusora, a Chardonnay and Viognier blend fermented in stainless steel, showed the success of those varieties in the rich, cool soils of the inland hills. It had tropical aromas and a soft body. With 13 percent alcohol, it was refreshing to drink. Typically Sicilian Chardonnay and Viognier wines have higher alcoholic content. Stefano Caruso is one of Perricone's most outspoken advocates. The variety has a long history in the Marsala-Salemi area. Growers used to call it Catarratto Rosso. Caruso ferments and matures it in stainless steel tanks to make Sachia. The 2009 vintage was deep reddish purple, with a mouth bursting with the smells of fresh cherries. A 2008 Syrah Riserva, Delia Nivolelli DOC, was opaque purple, with a balsamic nose and a round, soft mouth finished by lingering fine-textured astringency.

Marco De Bartoli.De Bartoli makes excellent Marsala-style wine and one of Sicily's best dry Grillo wines at the family farm, Samperi, outside the city of Marsala. The Grappolo del Grillo is barrel fermented, which gives it an aroma of grilled nuts. In 2010 De Bartoli told me that his 2008 “will be better in ten years.”

Fazio.Brothers Girolamo and Vincenzo Fazio asked Giacomo Ansaldi to help restructure what had been a cooperative winery. It now bears their family name. They brought Ansaldi on board as a partner and as the full-time enologist. He advised the brothers that the future of the industry would be tied to the English-speaking world. Hence the winery is officially named Fazio Wines. Vincenzo spearheaded efforts to register the Erice area, where the winery is located, as a DOC. The DOC began with the 2005 vintage. Most of the Fazio wines, however, are bottled under the Sicilia IGT designation. A Müller-Thurgau derived from grapes grown at 450 to 500 meters (1,476 to 1,640 feet) has garnered attention with a nose more scented with flowers and spices than German or Alsace examples. The alcohol level of 12.5 percent, lower than that of most other Sicilian wines, helps ensure its refreshing character. At the 2011 Vinitaly, Fazio introduced a sparkling version. My favorite varietal wine from Fazio is its Cabernet Sauvignon, which has the grape's dusty vegetal smells and characteristic fine astringency. The PietraSacra Nero d'Avola Erice DOC has tobacco scents and a fine astringent texture as well. The whites, always spicy, include two Inzolias, one bottled as an Erice DOC and the other as a Sicilia IGT, and Grillo and Catarratto Sicilia IGT wines.

Fina.Owner Bruno Fina worked as an IRVV enologist for ten years. This was during Tachis's consultancy. The two men developed a close working relationship. In 2005 Fina started a winery, Fina Vini, in the suburbs northeast of Marsala. His own vineyards supply 20 percent of the grapes he vinifies. His extensive knowledge of the terroirs of Western Sicily, combined with friendships and business contacts with many growers, enables him to carefully select the grapes he buys. The high quality of the fruit shows in the wine. He sources Fiano from high altitudes (four hundred meters [1,312 feet]) in the Contessa Entellina appellation near Menfi. The 2009 Fiano was very expressive, with lemon and peach scents. Its mouth is viscous yet tart. From the hills of the Calatifimi-Segesta area, Fina sources Viognier to make a spicy wine similar to the Fiano. When making Grillo, he blends the sea salt notes of grapes grown along the coast with the more aromatically fruited and sourer grapes from higher altitudes in the interior. Caro Maestro ("Dear Master"), a wine that he dedicates to Tachis, is a full-throttle blend of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Petit Verdot matured for two years in barrique and six months in bottle before release. The vintage that I tasted was opaque blue-black with mint and cinders in the nose. In the mouth, berry flavors enveloped a sheath of sourness and fine astringency. Fina's 2006 Syrah was one of the best Sicilian Syrahs that I have tasted. It was as dark as a moonless night. Slight smoke rose up with berry smells. The mouth was thick and wild with alcohol, bitterness, and astringency.

Firriato.Firriato has grown quickly since it was established in the mid-1980s, becoming one of the largest wine producers in Sicily, owning 320 hectares (790 acres) of vineyards and making more than five million bottles of wine annually. Besides holdings in Trapani, the winery owns eleven hectares (twenty-seven acres) of vineyards on Etna. During the late 1990s it quickly built up its northern European markets. During this rapid growth phase, the owners Salvatore and Vinzia Novara Di Gaetano hired Australian and New Zealand enologists. Their wines began to display an international style. The wines have been driven by concepts rather than place of origin, though the Etna wines prove they can do otherwise, and their Favignana project could also yield place-specific results. Lately the company has turned to the Tuscan consulting enologist Stefano Chioccioli. Harmonium Nero d'Avola is deep purple-black, with burned oak and blackberry fruit, and is extremely soft and thick in the mouth. Camelot, a Cabernet Sauvignon-Merlot blend, has more astringency than the Harmonium. This gives it more structure. The Firriato winery is in Paceco just east of the city of Trapani, but it purchases its grapes from throughout Sicily.

Fondo Antico.Giuseppe Agostino Adragna, a personable commercial manager, and Lorenza Scianna, a young enologist who combines technical skill, enthusiasm, and energy, breathe professionalism and excitement into the Polizzotti family's winery, Fondo Antico. Sensing the shift from international to indigenous varieties, the company discontinued its international wines except for Syrah. Fondo Antico's calling card is Grillo, particularly its Grillo Parlante (50 percent of production, 150,000 bottles per year). Although the winery is in Birgi, a coastal area, its vineyard elevation ranges from fifty meters (164 feet) near the coast to 250 (820 feet) meters on inland hills. Grillo Parlante tastes fresh and lively without giving up the sapidity that characterizes coastal Grillo. Il Coro Grillo has the tactile edge of wood contact without an oak scent because the barrels used are made of acacia wood. Fondo Antico's Nero d'Avola comes from cool clay soils. The resulting red and rosato (Aprile) wines are fresh and lively. Unforgettable is a 2007 Memorie Clairette, made by pressing fresh Nero d'Avola grapes and fermenting the red-tinted must in barrique. It was both delicate and complex.

Gorghi Tondi.The Sicilian wine industry has been a man's world until the past twenty years. Two sisters, Annamaria and Clara Sala, manage the Tenuta Gorghi Tondi estate for their family. The company's thirty-five hectares (eighty-six acres) of vines, all in contrada San Nicola in Mazara del Vallo, are divided into vineyards that run up to the Mediterranean and several that lie adjacent to small saltwater lakes in a World Wildlife Fund nature reserve. Grillo dominates the varieties planted seaside in red sandy soils. Nero d'Avola and Chardonnay, two varieties strongly associated with calcium carbonate, are planted in vineyards that abut the lakes, which are karstic (that is, connected to one another and to the Mediterranean by underground streams and caverns set in limestone). At the 2012 Vinitaly, I tasted a citrusy-salty Grillo wine, the 2011 Kheirè, from the sandy-clay soils. The 2011 Rajàh, a dry Zibibbo, was more aromatic, with rich grapefruit and orange smells, and was also saline. The estate also makes a Chardonnay and a Nero d'Avola from the high–calcium carbonate, silt-dominant soils by the lakes. There is a one hectare (two and a half acre) Grillo vineyard planted next to one of the lakes in a spot protected from the offshore winds. Here the Botrytis cinerea fungus gradually attacks the overmature Grillo. Due to unusual local climatic conditions, this fungus, which most of the time destroys grape quality, here enhances it. The result is Grillo D'Oro Passito, Sicily's finest botrytis wine. There aren't many like it, due to the island's dry, windy climate. The 2008 had a nose of dried fig, caramel, and ripe grapefruit and was characteristically viscous in the mouth.

La Divina.At La Divina, a boutique winery in a renovated Florio baglio in view of the island of Mozia, Giacomo Ansaldi makes two dry wines—a white, Abbadessa, a blend of Grillo and Zibibbo, and Cipponeri, a blend of Nero d'Avola and Perricone. Both are ripe and extracted in style. The Abbadessa is deep golden yellow, with strong orange and tropical fruit smells, and viscous with a savory bitter edge. The Cipponeri is deep in color and has a lusty red fruit nose and a thick, rustic mouthful of textures. Ansaldi also makes one sweet, late-harvest wine, Aruta. It is amber and made from dried Zibbibo grapes vinified and aged in oak. All three wines are in very limited production and only available at his relais-restaurant, Donna Franca.

La Terzavia.Renato De Bartoli, Marco's son, has been developing his own brand, La Terzavia. He vinifies the wines at Samperi, the family estate southeast of Marsala, using Grillo from the hills there to make a nondosage metodo classico sparkling wine.

Other recommended producers and their wines:

Cantine Rallo Aquamadre

Cantine Rallo Bianco Maggiore

Cantine Rallo Perla Dell'Eremo Müller Thurgau

Duca di Salaparuta Bianca di Valguarnera

Duca di Salaparuta Calanica Inzolia-Chardonnay

Duca di Salaparuta Kados

VAL DI MAZARA—EAST

PALERMO HIGHLANDS

The Palermo Highlands had two periods of promising developments in its local wine industry. In the late eighteenth century, King Ferdinand III of Sicily from his throne in Naples sent the agricultural specialist Felice Lioy to help improve the production of wheat, oil, wine, and other products. Lioy visited farms in the towns around Palermo. He observed agricultural practices and offered advice to farmers. Unfortunately, his counsel was met with indifference and resentment. In 1799, with Napoleon Bonaparte threatening Naples, Ferdinand fled to Palermo. The following year, the Real Cantina Borbonica ("Royal Bourbon Winery") was built in the town of Partinico southwest of Palermo. It had a sophisticated design that allowed horse-drawn carts to drive up ramps and deliver their baskets of grapes at the top of stone vats. Once the grapes were unloaded into the vats, workers crushed them. While the fermenting must was still warm, it was drained into casks and regularly refilled with must that had been set aside. Today this process is called topping-up. Lioy was the enological force behind these innovations. In 1802, Giovanni Meli described closed fermentation tanks in use in Bagheria by the Prince of Butera and in Misilmeri by the Prince Cattolica, but this practice seems not to have spread.3 With Ferdinand's final return to Naples in 1815 and his death in 1825, the Real Cantina Borbonica fell into disuse. The local wine industry returned to its pre-Lioy practices.

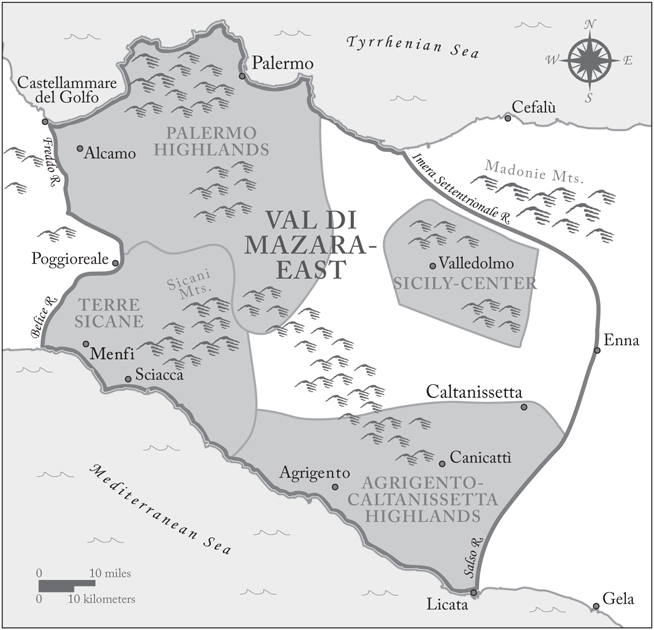

MAP 3.

Val di Mazara—East

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the hills to the southwest, south, and southeast of Palermo became the site of a nascent high-quality wine industry. A fertile plain called the Conca d'Oro ("Golden Shell") rings the city. The Conca d'Oro is about one hundred square kilometers (thirty-nine square miles) and lies between the mountains that encircle Palermo and the Tyrrhenian Sea off Sicily's north coast. Since the time of the Norman kings, the Conca d'Oro has been celebrated for its luxuriant gardens and citrus groves. It is where the wealthy noble families of Palermo built their lavish country villas and gardens in the nineteenth century. These families typically garnered an income from large agricultural holdings in various other parts of Sicily. They spent most of their time and money on the pleasures and pursuits of life in and around Palermo, returning to check on the operation of their rural farms perhaps a few times per year, or perhaps never at all.