The Play House: Carroll at the Theatre in London

‘Aedes Christi’ – ‘House of God’: ‘the House’

The auditorium of a theatre: ‘the House’

WHILE THE TRAIN FACILITATED such one-off trips for photography to the Isle of Wight and Devon, it also enabled Carroll to travel regularly from Christ Church to London to attend exhibitions, to buy photographs and photographic supplies. On 31 July 1863, for example, he ordered chemicals at Thomas’s and left negatives for printing at Cundall’s (IV, 229) while, on 6 April 1866, he recorded ‘looking over’ and buying ‘a few’ of ‘Rejlander’s photographs from De La Rue’s’ (V, 137). In June 1866 he even made enquiries, ‘without success’, about renting a photographic studio in the capital (V, 162). Going up to town was as much a part of Carroll’s life as attending events in Oxford. But it was especially the theatre – and many kinds of theatrical performance – that prompted him to take the train to the capital either for the day or, when his university duties allowed, for several days at a time.

Focusing upon theatrical events and performers from the 1860s and ’70s, this chapter explores the emergent and increasingly significant closeness for Carroll between photography and theatre in its myriad forms. It is framed by two performances: the first in 1867 by the Living Miniatures and the other in 1871 by the celebrated acrobat Lulu. Both were significant for Carroll in their relationship to photography. In visual terms, he prized the miniature performer’s costumed body and, in so doing, as Carolyn Steedman’s Strange Dislocations has demonstrated, he was not alone in the period.1 In her study of Mignon, the ‘strange, deformed and piercingly beautiful child acrobat’ from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, Steedman explores ways in which, from the eighteenth century onwards, the figure of the child acrobat was constantly rewritten and reshaped as an ‘idea or concept of the self’ and an irretrievable past.2 Intrinsic to the acrobat figure is an idea of ‘littleness’ and, as Steedman points out, for Goethe’s Wilhelm ‘what had delighted the child-in-memory’ was the diminutive size of the puppet figures he had played with.3 For Carroll, whether she was a fairy, an equestrian entertainer, or an acrobat, the small performer he enjoyed watching became changed both actually and conceptually into a photograph. Yet, while photography was the miniaturizing technology par excellence, the process of metamorphosis from stage to photographic plate was a complex one in which the inanimate figures of dolls and marionettes played an intermediate role. By fusing London theatre with other kinds of spectacle, real-life performers with toys, Carroll inhabits a space anticipating that which Henri Bergson in his study of laughter calls a ‘zone of artifice, midway between nature and art’.4

Carroll’s passion for the stage had begun in childhood when he masterminded ingenious amusements for his siblings. At the Old Rectory at Croft-on-Tees, he had invented puzzles, magic tricks, along with humorous copy for domestic magazines. In addition, he choreographed charades and dramatic productions for the marionette theatre he constructed with the help of a carpenter from the village (I, 19). With seven sisters and three brothers – eight of them younger – Carroll was rarely short of actors in his scenarios. Yet the matter of attending a public theatre was never straightforward since he had to negotiate his passion for such entertainment in relation to the absolute injunction, upheld by his father and his good friend Henry Parry Liddon, against attending the theatre. Archdeacon Dodgson’s prohibition, however, did not prevent Carroll from enjoying performances whenever the opportunity arose, but it may explain the fact that, as Richard Foulkes indicates, Carroll attended few theatrical productions in Oxford.5 There his presence in an auditorium would have been conspicuous.

Since theatre visits to London meant mixing with people from all social classes, they demonstrate the limitations of portraying Carroll as a cleric divorced from contemporary nineteenth-century social concerns. Indeed, theatre and pornography, historically sharing the same districts in the capital, remained closely linked in the Victorian period and, given the location of some of the theatres, Carroll sometimes stayed at hotels in areas known for prostitution. As Donald Thomas points out, Carroll’s visits to the Olympic Theatre in Wych Street brought him within the vicinity of three shops dealing in pornographic prints, while the neighbouring Holywell Street was a notorious location of ‘the mid-Victorian trade in pornography’.6 From exposure to this location alone, Carroll could not ‘have been unaware of the less agreeable uses of the camera, even before the 1870s’, and his personal library indicates ‘he had read up on London “vice”, and was fully aware of those locations in which one was most likely to encounter it and the specific forms it might take’.7

It is in this context that Carroll’s life-long interest in the theatre has led biographers to conclude that his eventual decision not to proceed to full ordination was in part owing to his unwillingness to give it up.8 Certainly, the timing in 1862 of his choice not to take full Holy Orders makes it difficult not to connect his theatre-going, and his accompanying passion for photography, with expressions of guilt attached to time wasting especially fulsomely expressed in his diaries of the period.9 In spite of such self-reproach, however, during the 1860s and ’70s, frequenting the London homes of literary and artistic families such as George and Louisa MacDonald, Benjamin and Sarah Terry, John Everett and Effie Millais, Carroll divided his time between photographing and attending the theatre.10 Since the MacDonalds, and especially the Terrys, were theatrical families, his friendship with them gave him regular access to productions and opportunities to photograph actors. However, theatre and photography did not simply dovetail in practical ways. Photography was ‘theatre’ for Carroll in the sense that he increasingly came to conceive it. In formal terms, through the miraculous capture of costumes, gestures and effects, a photograph had the potential to arrest character, as put on. Most obviously in the mechanically reproducible form of photographs, viewers might experience over and again the stilled scenarios of theatrical tableaux.

At the same time, the increasing availability in the 1860s of cartes de visite of contemporary actors resulted in a new cult of celebrity. It is at the expense of the more conceptual relationship of photography to performance, though, that critics have tended to focus on the place in commodity culture of such commercial photographs of actors. They have barely begun to address more subtle ways in which Carroll’s interest in photographs was bound to his attachment to the stage. Courting conceptual complexities of all kinds, he was drawn to the fundamental difference between the medium of photography as a silent and two-dimensional form and theatre as an animated three-dimensional spectacle. This is not to say that he did not relish buying cartes of actors (he clearly did and prized them as additions to his albums), or that he failed to delight in humdrum entertainments. Indeed, he made few bones about doing so. Yet in habitually wanting to attend performances, often the same ones more than once, Carroll enjoyed theatre in ways similar to those in which he enjoyed repetition of a photographic take. At a formal level the proscenium arch and the camera lens contained visually immediate scenes. And Carroll enjoyed the immediacy of theatre just as he enjoyed the direct imprint of a photographic image. In both cases, however, he also took particular pleasure in knowing that such immediacy came to him in a mediated form.

Especially fond of drama aimed at juveniles, Carroll never lost his taste for pantomime and burlesque. But he was not unique among adults in the period in frequenting productions acted by, and aimed at, children. Indeed, for many in Victorian Britain, the annual pantomime that began on Boxing Day and ran for several months was a seasonal draw. With its carnivalesque humour, its mixture of wordplay and inversion, together with visual splendour and audience participation, pantomime embodied all the things Carroll had loved as a child and continued to prize as an adult. Writing, thereby, on 11 February 1877 to thirteen-year-old Gertrude Chataway enquiring: ‘I wonder if you have ever seen a Pantomime at all?’, he was not being entirely facetious in claiming, ‘if not, your education is quite incomplete’.11 But not only did Carroll delight in watching child actors perform, he enjoyed being among audiences comprising children, sharing their spontaneous responses to theatre of different types. His fondness for attending the same production several times – in the case of Edward Blanchard’s Robin Hood and his Merry Little Men at the Adelphi a total of six – migrated to his photographic practice in which he liked to take different children in the same costume. By repeating fundamental elements of staging and set up, he utilized photographic repetition in a way that echoed the experience of multiple performances of the same theatrical production.

The variety of shows Carroll enjoyed is nowhere more evident than in the following reminiscence of Greville MacDonald, the son of Carroll’s good friends the novelist George MacDonald and his wife, Louisa:

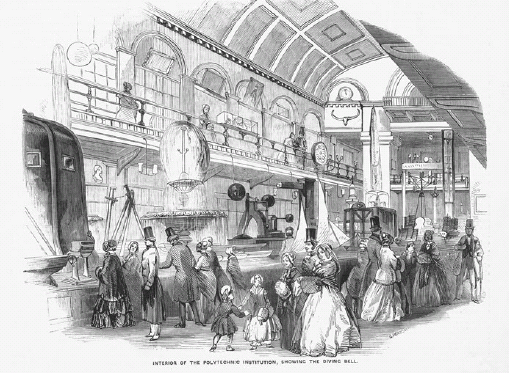

Our annual treat was Uncle Dodgson’s taking us to the Polytechnic for the entrancing ‘dissolving views’ of fairy tales, or to go down in the diving bell, or watch the mechanical athlete Leotard. There was also the Coliseum in Albany Street, with its storms by land and sea on a wonderful stage, and its great panorama of London. And there was Cremer’s toyshop in Regent Street . . . all associated in my memory with the adorable writer of Alice.12

35 Interior of the Polytechnic Institute with diving bell, 1850, engraving.

For Greville MacDonald the peculiar pleasures of Carroll’s company bring to mind a range of engaging spectacles in addition to plays and pantomimes. To remember the optical intrigue of a ‘dissolving view’ is to throw into heightened relief the subterranean mystery of a ride in the diving bell at the Polytechnic Institute in Regent Street (illus. 35). That attraction, in turn, conjures the ingenious toy, the mechanical Leotard manufactured in the 1860s, which, by a process of shifting sand, activated a model of the celebrated French trapeze artist. Equally, Greville MacDonald’s indelible memory of ‘Cremer’s toyshop’ emerges alongside the monumental context of the panorama. Promising more than simply ‘toys’, W. H. Cremer’s saloon of magic at 210 Regent Street13 specialized in ‘Illusions, Magic, Optics’ and had ‘a platform like a small stage one end where tricks were demonstrated by a resident magician’.14 It was a place of performance just as powerful in its own way as those grander illusionistic spaces of London theatres. In bringing together such variously miraculous spectacles, Greville MacDonald’s vivid memoir provides a reminder that Carroll’s fondness for theatre was throughout his life bound up with other kinds of attachment: to magic, and illusionism, to acrobatics, toys, and newfangled gadgets of all kinds. London provided a wealth of all of these.

THE LIVING MINIATURES

THE LIVING MINIATURES

On 24 January 1867 Carroll took two of the MacDonald children to the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, to see the Living Miniatures, a troupe of 27 exclusively child actors, in an anonymous extravaganza, Littletop’s Christmas Party, and an alliteratively titled burlesque by Reginald Moore, Sylvius, or The Peril, the Pelf and the Pearl (illus. 36). The performers, ranging in height from thirty to fifty inches, were managed by Thomas Coe, Stage Director at the Haymarket, actor and acting teacher.15 In his diary for that date Carroll notes: ‘the whole performance was far beyond anything I have yet seen done by children’ (V, 193). Reviews in the popular press of the time confirmed Carroll’s high opinion of the Living Miniatures. A reviewer in The Era, for example, described the company as a troupe of 27 juveniles ‘accomplished in a triple sense . . . as actors and actresses, singers, and dancers’, claiming that most child actors ‘have not a tithe of the talent shown by this Lilliputian company’.16 The Sporting Gazette similarly noted: ‘Altogether the juvenile troupe go through their parts with much spirit, and in some of them considerable cleverness is shown.’17

36 Alfred Concanen, The Living Miniatures, 1867, colour lithograph.

On 2 March 1867 Carroll went a second time to see the Living Miniatures. On this occasion, he wrote a long and detailed account of the event in his diary. Unique to this visit was an opportunity to venture behind the scenes, to experience the workings of a theatre and to meet a cast made up entirely of children. Afforded privileged access to the staging, Carroll appreciated observing the child actors as they interacted both with their peers and with adult directors. And in documenting the experience he remarks upon the relative degrees of the children’s beauty as witnessed from the auditorium and close to:

I was agreeably surprised to see how pretty some of them were, even with all the disadvantage of daylight and rouge . . . The one of the actresses whom I had thought prettiest on the last occasion, is not so pretty when seen close – J. Henri: she is consumptive, Mr Coe tells me, and looks almost too delicate for the work – Mrs Coe soon joined me in the prompter’s box, carrying with her the dear little Annette, who seemed to be a general pet, and also throughout the performance was trotting about just where she liked, as were all of the children, but without ever being in any one’s way, or out of the way when wanted (V, 202–3).

While ‘the disadvantage of daylight and rouge’ does not mar the appearance of many of the children it does mean that ‘the prettiest’, ‘J. Henri’, is not so when seen close up. Moreover, when Carroll discovers this particular child is consumptive, he registers, albeit in passing, a question of the appropriateness of the profession for a sick child.

Such concern for the physical well-being and working conditions of child performers would become increasingly a matter of public discussion, culminating in 1889 in legislation in the form of the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act.18 Consistent with his interest during the 1880s in age of consent legislation, Carroll was fully involved in this debate. Yet, while later political discussion would focus on definitions of ‘labour’ and working conditions of child performers, what he witnessed in the 1860s of the backstage circumstances of the Living Miniatures confirmed for him their appropriateness for child actors. From a backstage perspective Carroll was taken with a sense that performing ‘did not seem to be work to any of the children: they evidently enjoyed it thoroughly’ (V, 203). Reassured that the Living Miniatures were not being coerced into their labour, Carroll goes on to equate acting with ‘play’ as a legitimate activity of childhood. At the same time, in remarking upon the children’s maturity, organization and resourcefulness in remembering their cues without adult intervention, he is also struck by their ‘clock-work’ regularity (V, 203). The metaphor is telling, for, in the form of the mechanism that animates it, he connects the miniature actor, her uniformity and guarantee of repetition, to the child’s toy. These were qualities Carroll celebrated not only in this troupe of child actors but in child performers more generally.

Of the two shows he saw by the Living Miniatures, Carroll notes ‘the burlesque was much prettier to see from behind than the comedy, as the children looked so much prettier in burlesque dresses – especially J. Henri as “Sylvius”, Lillie Lee, and two little fairies, twins, of the name of Lacy’ (v, 203). Costumes, always a draw for Carroll, were heightened by such a backstage view. Tracy Davis has explored ways in which in adult burlesque, as in ‘opera bouffe, pantomime, music hall, musical comedy, ballet and extravaganza, conventions of costume, gesture, and theatrical mis-en-scène ensured that the most banal material was infused with sensuality’ and ‘deliberately manipulated to result in the erotic arousal of male spectators’.19 In this context, the behind-the-scenes encounter was important in exposing what was ‘normally hidden’.20 While it would be simplifying Carroll’s response to read it exclusively in this regard, it is important to consider ways in which such theatrically encoded erotic effects, for Davis ‘invisible and unintelligible to many spectators’, might be differently inflected in the context of child performers.21 Carroll’s visit to the Living Miniatures raises issues of voyeurism as sanctioned by different strands of Victorian theatre. But, in addition to a chance to see things usually hidden, his behind-the-scenes encounter offered an attractive physical inversion. Akin to a ‘looking-glass’ perspective, it gave a sense of peering back from the depths of the mirror. As his diary entry of 12 January 1869 reveals, Carroll’s first title for Through the Looking-Glass was ‘Behind the Looking-Glass, and what Alice saw there’ (vi, 76), thereby designating not simply a world previously invisible on the other side of the fireplace, but a position ‘behind’ the glass from which to look back to the familiar side. The French translation of Through the Looking-Glass – L’Autre côté du mirroir – retains this important dimension of the experience.22 In a letter to his brother Edwin regarding the Living Miniatures, Carroll mentions in particular a ‘snow-storm’ enhanced by an inverted vantage point from which he was able to watch: ‘cut paper being showered down by a man on the top of a pair of steps’.23

An additional attraction of viewing the Living Miniatures from behind was in occupying the position of a child performer looking out from the stage into the auditorium. From backstage, Carroll enjoys a dual movement in which he may look at children without being noticed while at the same time identifying with their skills in performing to an audience. Identifying also with what he reads as the ‘pleasure’ of child performers, he is drawn to the linguistic accomplishment of child actors – their enunciation, sharp diction and timing in delivery of their lines and their capacity to learn long and often sophisticated scripts. These were qualities with which he was perpetually concerned in his experience of speech as difficult and hesitant, and his longing to correct it. As chapter Five will demonstrate, Carroll’s enduring interest in the speech of children was not unrelated to his stammer and, in theatrical contexts, comedy in the form of wordplay and puns celebrated – sanctioned even – forms of irregular speech.

Acknowledging that Victorian adult spectators, male and female alike, were fascinated by the ability of child actors to deliver their lines with impeccable fluency, recent work has taken up the ‘precocity’ of stage children to correct what it regards as an overemphasis on voyeurism on the part of adult male viewers including ‘child lovers’ such as Carroll and Ernest Dowson.24 Marah Gubar challenges seminal texts such as Jacqueline Rose’s The Case of Peter Pan, which focus upon the voyeuristic nature of the Victorians’ interest in the child’s body, claiming Victorian stage children successfully ‘blur[red] the line between innocence and experience’. In contending that ‘precocious competence’ was a key draw for audiences, she calls for readers ‘to reconsider whether the cult of the child was really about freezing the child in place as the embodiment of artless innocence’.25

Yet, while Victorian audiences undoubtedly relished seeing clever children perform with the facility and poise of adults, a question arises as to the extent to which a concept of precocity shifts emphasis, as Guber intends, from a child’s body to her acting abilities. The term ‘precocious’, from the Latin meaning ‘prematurely ripe’, precisely confirms the proximity of a concept of ‘cleverness’ to questions of the child’s physicality. Implying sexual readiness in advance of its time, and a potential to go to waste, the word ‘precocity’ retains a sexual connotation of ‘ripeness’. Thus, while Gubar calls for ‘a more balanced view on stage children’,26 when, in the period, adult audiences enjoyed watching minors performing in advance the feats that generally belonged to majors, they did not celebrate exclusively linguistic or cognitive prematurity, for those feats of linguistic virtuosity emerged from immature bodies. Victorian adults precisely enjoyed watching childish frames transformed by adult potentialities. In praising child actors, Carroll and some of his contemporaries appeared to respond to a capacity for metamorphosis, or physical transformation, of a child’s body as she performed in such a way. It was a quality that photography came close to capturing.

Costumes and staging were at the heart of such transformation and key to Carroll’s attraction to the Living Miniatures. What becomes apparent in the lengthy record of his visit to Coe’s company is that it is not the children per se, devoid of costume and props, in which he is most interested, but the children in costume. As he further notes: ‘If I take my camera to town this summer, I shall certainly get some of the children to photograph – though there is little chance of the costumes then being in existence.’ Out of costume, the miniature performers are simply not as attractive to him for photography. While one might reduce his comment to a wish to photograph children’s bodies in the most revealing clothing of their stage roles, it would be grossly oversimplifying his response to assume that this would be the case. Clothing clearly functions in the capacity of fetish here, as it did for others. However, both as material objects, and preserved in photographs of children wearing them, costumes in complex ways come to stand in the larger whole of a theatrical event.

In Romantic Imprisonment: Women and Other Classified Outcasts Nina Auerbach identifies a key connection between the child performer and photography that remains important to an understanding of Carroll’s longing to marry the two: ‘To elicit the essence of his sitters Carroll seems to have encouraged them to act, thus releasing the metaphoric potential he saw coiled within little girls: the hallmarks of his photographs is the use of costumes, props, and the imaginative intensity of an improvised scene caught at midpoint.’27 While he did not so much encourage them to ‘act’ as dress them up to resemble actors, a quality of improvisation was key to Carroll’s photographic practice. For Auerbach, a sense of captured animation in ‘an improvised scene caught at midpoint’ connects Carroll’s photographs with theatre. But, while the camera petrifies what it represents, part of its perpetual magic lies also in its capacity to suggest innate movement within that stilled form of the photographic image. As ‘stills’, as it were, related to previously moving spectacles, photographs of child performers in particular provided a repository of the imaginative intensity of such scenes.

In the case of the Living Miniatures, such intensity is evident in their willingness to ‘play’ beyond the requirements of their role that recalls Charles Baudelaire’s understanding of child’s play as indicative of children’s ‘great capacity for abstraction and their high imaginative power’.28 Referring, in his ‘Morale du joujou’ (‘Philosophy of Toys’, 1853), to a child’s ability to turn a mundane object into a grand or unlikely one, Baudelaire remarks upon what he calls the ‘the eternal drama of the diligence played with chairs!’29 He is drawn, in particular, to a child’s transformation of a static object into a moving one, a horse or a carriage, to produce a quality of ‘scorching speed’ by which to ‘devour’ what he calls the ‘fictive spaces’ of a room.30 While Carroll similarly savours childish invention as revealed through games, on occasion in photographing children he contrived their metamorphosis into playthings. That is to say, picturing a child’s resemblance to a doll or a marionette, the camera facilitated visual transformation in a manner resembling live performance.

When theatricality and photography came together for Carroll the result was compelling. A child’s simulation of action through static objects is at the heart of Carroll’s photograph of St George and the Dragon, 1875 (illus. 37). In the staged tableau blatantly fictional props testify to the inventive capacity of child’s play. But those props also signal a photographer’s recreation of the blandness to an adult eye of that mundane adult space that in Baudelaire’s terms is only ‘fictive’ to the child. St George and the Dragon is one of a small number of photographs in which Carroll tells a story with ‘actors’.31 Xie Kitchin, along with her three brothers, poses in a mythological tableau. Brooke Taylor as St George rides the large rocking horse; George Herbert in a heap on the floor represents the defeated knight, while Hugh Bridges plays the Dragon. But what is striking about this photograph is the way in which it does not simply reveal its artifice, but also revels in doing so. The leopard skin barely covers the child’s crouching body and the sword, shields and other props are half-heartedly deployed. However, this is precisely the point. For Carroll exposes the dissembling that produces the event. He seeks to fix it in order to be able to revisit it, when displayed in an album, in such terms of visible imperfection.

37 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), St George and the Dragon, 1875, albumen print.

Contriving a form of illusionism uniquely credible to a child, St George and the Dragon is on a par with the fabrication of snow from shredded paper that Carroll had earlier enjoyed in the performance of the Living Miniatures. In the photograph Carroll concocts a faulty theatrical spectacle in which anomalies of scale – the large sword and child-size armour – register the visual imperfection he wishes to celebrate. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the drama leaves untouched the princess, Xie, in her nightdress and foil crown. Positioned on the edge of the composition, uninvolved in the spectacle, she directs her gaze straight at the camera. In this fictional scenario that resembles a dreamscape, Xie is the dreamer and stand-in for Carroll, who observes himself in the detached figure of the little girl who ‘acts’.

THE MINIATURE AND TOYS

THE MINIATURE AND TOYS

In stressing the artifice of children adopting roles in theatrical tableaux, Carroll also defamiliarizes the child, visually demonstrating his, but more usually ‘her’, resemblance to the doll. But he does not simply connect the photographed child with the toy by a process of miniaturization, but also by one of arrested motion and its perpetual promise in the form of clockwork. Like a dependable actor, a mechanical toy guarantees repetition of the same performance: it appears to deliver its virtuosity ad infinitum. According to Susan Stewart in On Longing, ‘the inanimate toy repeats the still life’s theme of arrested life’. However, once the toy springs into action, ‘it initiates another world, the world of the daydream’.32 While Stewart’s account does not deal with photography, her explanation of the fluctuation between arrested life and the world of ‘fantasy’33 articulates what was for Carroll played out in a three-way connection between the toy, the child and the photograph. Indeed, part of the allure for him of a photograph was that, rather like the mechanism of the animated toy, it held the capacity to unlock ‘an interior world, lending itself to fantasy and privacy’.34 As Stewart explains, the ‘narrative time’ of the wind-up toy does not extend daily life. Instead, it unlocks a ‘world parallel to (and hence never intersecting) the world of everyday reality’.35 For Carroll, a photograph of a miniature performer offered access to this otherworldly realm. Like the mechanism of a toy, via photography the life of the performer may be interrupted, restarted and stopped again. In practice, however, a clockwork toy relies on a mechanism that must eventually wear down.

Carroll was fascinated by the potential for the inanimate form to be wound into life as evident in his passion for clockwork toys and musical boxes. It is well known from the reminiscence of his ‘child friend’ Ethel Arnold that his cupboards at Christ Church held ‘wondrous treasures’ in the forms of ‘mechanical bears, dancing-dolls, toys and puzzles of every description’.36 Moreover, sometimes Carroll ‘liked to play his musical boxes backwards for relaxation’,37 anticipating aspects of the mechanical toy that Stewart explores:

On the one hand, we have the mechanical toy speaking a repetition and closure that the everyday world finds impossible. The mechanical toy threatens an infinite pleasure; it does not tire or feel, it simply works or doesn’t work. On the other hand, we have the actual place of toys in the world of the dead. As part of the general inversions which the world presents, the inanimate comes to life. But more than this, just as the world of objects is always a kind of ‘dead among us’, the toy ensures the continuation, in miniature, of the world of life ‘on the other side’.38

Entertained by repetitive action, as Baudelaire has noted, it is not unusual from time to time for a child to make a toy ‘restart its mechanical motions, sometimes in the opposite direction’, such that ‘its marvellous life comes to a stop’.

In this realm of stop motion, the conspicuous adjective ‘living’ in the name ‘the Living Miniatures’ clearly appealed to Carroll’s larger fascination for miniature life. That fascination found a number of other outlets. A striking and seemingly anachronistic one begins to make sense in the context of the small theatre troupe, namely Carroll’s scheme in 1872, five years after seeing the Living Miniatures, to secure a child-sized mannequin with the dimensions of the eight-year-old Julia Arnold (4 feet 3 inches) in order to clothe and photograph it. I have previously considered the significance of this plan in relation to the function of height more generally in Carroll’s photographic aesthetic.39 But, in addition to preserving in a lay figure the measurements of the child, he wishes to capture her resemblance to a toy. In the event, Carroll’s plan to create a sort of theatrical trick with photography was thwarted by the fact that, as his diary entry for 2 April 1872 indicates, all affordable models were of adult proportions:

Then to Lechertier, Barbe and Co. (60 Regent St.) to see lay figures. I came to the conclusion that stuffed would be the only kind of any use to me, but the price is too high to venture on. (Wooden would be about £4, but they are all adult proportions, Papier-mâché would be £6 or so, but there are none the size I want. While stuffed would be £30!) (VI, 206).

38 Charles Roberson & Co., ‘Child No. 98’, artist’s lay figure, ‘Parisian stuffed’, 19th century.

The lay figure, as Carroll’s diary entry reveals, is a curious object. In the period there existed small-scale beech-wood figures with ball-jointed bodies, but also extremely elaborate life-size stuffed ones with canvas bodies (illus. 38). Some of them came with papier mâché faces and suits of clothes making them distinct from the familiar jointed wooden and faceless figures. Weighing up the various materials and prices of those lay figures available, he decides against ‘stuffed’ on account of the price while realizing that the inferior alternatives are not the right size. On his death, however, two artist’s lay figures were listed in his personal effects.40 What was Carroll aspiring to in this strangely conceived scheme? In one sense, he wishes to produce a life-sized replica of Julia Arnold to be looked at as actors are. Inanimate, the desired duplicate would resemble a toy – a doll – and in this capacity would provide a connection to childhood passions and forms of attachment. But, in another sense, photographed, the inanimate costumed mannequin of Julia Arnold would paradoxically suggest concealed life or motion. A photograph of an actual child, by comparison, in arresting movement, may evoke the stopped motion of a wind-up toy. At a conceptual level, then, Carroll invites a connection between the stop/start mechanism of a clockwork toy and the miraculous movement latent in a static photograph. Fascinated by the paradox of arrested life, he is drawn to the idea that an inanimate form, such as a lay figure or a doll, may be made to live in a photograph.

PHOTOGRAPHS AS TOYS

PHOTOGRAPHS AS TOYS

Lechertier Barbe & Co., the artists’ colourmen and supplier of lay figures, crops up in a related fashion in the second of the four chapters that form the journalist George Sala’s ‘Travels in Regent Street’, where as a child an ‘effigy’ he had regularly seen in the shop window fixed itself upon his mind like a toy on display.41 Reflecting back from 1894 upon the constants of Regent Street, Sala acknowledges that he remembers the figure, in part, because it is grotesque. He attributes the brilliance of his mental image, however, to the frequency with which he passed it as a child displayed among the mysterious ‘lay’ figures at ‘Barbe’s’, those lifelike, in some cases life-sized, figures somewhere between humans and automata.

For Sala, as for Carroll, the London arcades, especially the toys in the famous Lowther’s Arcade in the Strand, were a particular draw. As Leslie Daiken points out, Lowther’s ‘was regarded as one of the sights of London, [and] was continually thronged with children and their attendants buying toys’.42 Practically 200 feet in length, the Arcade contained a wide variety of toys from Switzerland, Germany and France together with some from China and Japan.43 In particular, it held the miniature forms of dolls’ houses and tea-sets, along with ‘red-handled carpenters’ tools’44 resembling the child-size set of tools Carroll made for his sister Elizabeth in 1846. Such shops, along with the spectacle of their windows, as Colin Campbell has pointed out, contributed to the increasing use of ‘cultural artefacts as the material for daydreams, a form of projected illusory enjoyment’.45 The sight of such objects that often gave greater pleasure than ‘ownership’ of them might be ‘brought to mind in the future, and repeatedly re-used and adapted’ in the creation of ‘personal fantasies’.46

For Baudelaire, it is his childhood experience of the incomparable plenitude of the toyshop that he remembers. At the beginning of ‘A Philosophy of Toys’, he harks back to the occasion when, on a visit with his mother to Madame Panckoucke – who held a literary salon in Paris – he was invited to choose a toy from a ‘truly fairylike spectacle of offerings’. Presented with ‘a whole world of toys of all kinds, from the most costly to the most trifling, from the simplest to the most complicated’,47 Baudelaire explains how he selected the most lavish and expensive toy in the woman’s collection. However, deterred by his mother from taking it, he has to settle instead for a compromise, a toy somewhere in the middle and plainly disappointing. Baudelaire attributes to this formative occasion his inability in later life to pass by the spectacle of the window of a toyshop without staring into it. That fascination derives from the glut of miniature riches that produce a world ‘far more highly coloured, sparkling and polished than real life’.48 As he goes on to explain, since ‘All children talk to their toys they become actors in the great drama of life, reduced in size by the camera obscura of their little brains.’49 In so doing, toys make an indelible imprint upon the aesthetic sensibility of the child. But while Baudelaire claims ‘the toy is the child’s earliest initiation to art’, he concludes that with maturity ‘perfected examples will not give his mind the same feelings of warmth, nor the same enthusiasms, nor the same sense of conviction’.50 Most importantly, for my purposes, what Baudelaire identifies as lost in the setting aside for art of childish playthings captures, in effect, Carroll’s lifelong attachment to toys of all kinds and especially mechanical ones. Indeed, Baudelaire might have been thinking of Carroll when, in the same essay, he also notes that toys sometimes ‘dominate’ children: ‘It would hardly be surprising if a child of that kind, to whom his parents chiefly gave toy-theatres so that he could continue by himself the pleasure that he had had from stage-shows and marionettes, should grow used to regarding the theatre as the most delicious form of Beauty.’51

For Carroll a love of theatre had its origins in his childhood marionette puppets activated by strings and he regularly staged productions suitable both for marionettes and children. With his marionettes, Carroll sought to depict realistic spectacles and his reference to ‘about 20 figures’ – twelve was the standard – indicates he was staging quite elaborate shows.52 Since, in the period, marionette plays were often interchangeable with those for human adult actors, they aimed for comparable realism in costumes and props. Furthermore, unlike the ‘patent unreality of the glove puppet’, the attempt at verisimilitude in the case of marionettes lent to them ‘an extraordinary degree of ambivalence’.53 In popular Victorian fairground shows, marionettes had a close relationship to waxworks, ‘rope-dancing and acrobatics, performing monkeys and bears, conjuring tricks and peep-shows’ (illus. 39).54 But some marionette shows ‘occupied a middle ground between automata and waxworks’, sometimes introducing clockwork mechanisms to give a further ‘semblance of life’.55

39 Tiller Family Marionette Co., wire walker marionette, Lincolnshire, 1870–1900.

In his passion for staging marionette performances in which children might substitute for puppets, Carroll also establishes an early connection to photographic sittings. That connection comes about through small dimensions and qualities of grace, both attributes of Carroll’s ideal performer and his ideal photographic model. But as well as celebrating performativity as manifest in the puppet, Carroll recognized the important function of the toy more generally as an object of attachment for a child, one that might hold significance as what would later come to be known as a transitional object. In this regard, Carroll’s legendary toy cupboards at Christ Church may not have simply functioned to amuse his child visitors. They may have served to delight and comfort him.

A DOLL CALLED ‘TIM’

A DOLL CALLED ‘TIM’

In attaching in peculiar ways to those objects they represent, photographs offer nostalgic connection to the past and triggers for fantasy. In so doing, photographs, like toys, may function as transitional objects. We find a relic of Carroll’s childhood attachment to toys immortalized in a photograph of his ‘family’ doll (illus. 40) taken in 1858. Although the image is simply identified in Carroll’s hand as Tim, the ivy-clad background, closely resembling that in his well-known photograph Agnes Grace Weld as ‘Little Red Riding Hood’, taken the year before, suggests the same location: his home at Croft Rectory. Immediately striking is the difficulty of estimating the size of the doll in the photograph, for the picture of ‘Tim’, seated on an appropriately sized polished wooden chair, raises a question of whether the chair is Lilliputian or the doll life-size. In a conceit anticipating anomalies of scale that would come to characterize the Alice books, this seemingly innocuous and delightfully commonplace photograph is, for a budding amateur photographer, rather curious. Situated in front of the lens, ‘Tim’ the doll occupies the place that figures of children will increasingly come to occupy in Carroll’s work. Retrospectively, sat before the camera, ‘Tim’ the doll anticipates the child as photographic model. In so doing the image raises the question of what difference it would make to pose a doll in place of a child.

Tim appears to be made of wood with a papier mâché face and painted eyes. The soles of the doll’s shoes indicate the relatively low angle from which Carroll took the photograph. While the name ‘Tim’ suggests a male doll, ‘his’ clothing is somewhat androgynous. Moreover, the image is not without a hint of humour as the hat lends the figure resemblance to a scarecrow. In spite of its oddity, however, critics have largely dismissed the photograph. To be sure, it is very different from those more predictable photographs Carroll took of girls holding dolls. Edward Wakeling claims that nothing is known about the doll ‘Tim’ and that the photograph was taken when most of Carroll’s siblings would no longer have played with it as children. Yet this claim simply adds to, rather than dismisses, the curiosity of the picture. To justify a photographic ‘sitting’ in 1858 ‘Tim’ must have remained significant to Carroll. That significance is commemorated in the capacity of the medium to capture, in miniature, an object of attachment to home as a space of sanctioned play and invention. But, as Tim also anticipates Carroll’s photographic fascination with dressed-up girls seated on chairs, his miniaturized plaid clothes and knitted jacket resemble larger ones worn by Sarah Hobson in Carroll’s photograph of her taken around the same time. The connection appears more than accidental. The doll, though inanimate, is captured by photography, a medium able to suggest life in a ‘dead’ subject. Just as a photograph may restore to life a dead loved one, it may make a doll ‘live’.

40 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Tim, 1858, albumen print.

41 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Ella Chlora Monier-Williams and a Younger Brother, 1866, albumen print.

While ‘Tim’ is unusual in being pictured without an owner, Carroll also took a number of photographs in which children pose with their dolls. In his 1866 photograph of Ella Chlora Monier-Williams and a Younger Brother (illus. 41), for example, taken at his rented studio in Badcock’s Yard, the two children are pictured nestled together on a sofa looking down at the dolls they hold. While Ella Monier-Williams slouches against the arm of the sofa with her head against the cushion, her brother perches above her on his knees – his temple and cheek against her hair – resting his doll against hers. The alertness of his body, appearing to have suddenly come to rest in its pose, is silently confirmed by the way his knee catches the hem of his sister’s dress; the scuff on the toe of his left boot suggests he has arrived from more active play to fleetingly join her more settled position. Carroll captures intimacy between the siblings through their physical closeness but also by their shared concentration upon the toys they hold. A viewer is drawn firstly to the faces of the children and then to the centre of the image in which their hands and the fabric of the dolls’ and their own clothing form a kind of nest.

42 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Lorina Liddell [holding a black doll], 1858, albumen print.

Here Carroll achieves his wish to capture a natural positioning of hands in a photograph as outlined in a note he made to himself after visiting the Exhibition of British Artists in London in 1857.56 Taken from above, the photograph sacrifices some of the detail of the boy’s jacket to the intermediate tones of his and his sister’s face and hands, and of the dolls themselves, contrasted against the darker embossed floral motif of the sofa. It is a poignant image not least because the affection the children appear to be showing to the toys they hold would not be lost on an animate presence; substitute a creature such as a dove or, as in Carroll’s photograph of Bessie Slatter (1862), a pet guinea pig, and the sentiment portrayed would remain the same.

Comparing Ella Chlora Monier-Williams and a Younger Brother with Carroll’s earlier photograph Lorina Liddell [holding a black doll] (illus. 42), taken in the Deanery garden in 1858, reveals a more conventionally posed image of a girl in a maternal role with her toy. Yet the photograph again signals both the child’s distance from, and closeness to, the doll she holds. Seated upon the same chair on which her younger sister Alice sat for what has become a familiar picture of her in profile, Lorina Liddell cradles the doll upon her lap. But rather than looking at it she looks off to her left as if lost in thought. The presence of a black doll in a photograph is unusual in the period. Such dolls were by no means common in Britain in the 1850s. German and French companies dominated the market in doll manufacturing in the period but some wealthy children would have had black dolls. As Robin Bernstein indicates, since ‘many European black dolls were made from the same molds as white dolls’ they therefore ‘shared the same features’.57 Correcting to some extent the homogenization of features, the monochrome of photography here stresses the blackness of the doll and thereby its ethnic difference from its owner.

In a letter dated 13 November 1873 to Beatrice Hatch, Carroll brings a doll to life. He relates his extraordinary meeting with one he had given to the child as a present. Beatrice Hatch recalls the wax doll, named ‘Alice’, ‘had fair hair brushed back from its forehead . . . and when pinched would emit plaintive cries of “Pappa” and “Mamma”’.58 In Carroll’s comic account, ‘Alice’ the doll, abandoned by her owner, turns up ‘just outside Tom Gate’ at Christ Church with ‘two waxy tears . . . running down her cheeks’ and he takes her to his College rooms to comfort her where amusing scenarios ensue.59 Here, a doll is again interchangeable with a child. Indeed, the treatment she receives in Carroll’s Christ Church rooms is precisely that enjoyed by her owner Beatrice Hatch.

Carroll found further photographic interest in the theme of an abandoned doll. His photographs move from that of his doll ‘Tim’, through various depictions of girls holding dolls, to the figure of a child photographed as a doll. On 5 July 1870, in the studio he rented at Badcock’s Yard, Carroll took Xie Kitchin in a photograph entitled The Prettiest Doll in the World (illus. 43). It was based on the poem ‘The Lost Doll’, sung to Tom and other water babies by Mrs Doasyouwouldbedoneby in chapter Five of Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies (1863):

I once had a sweet little doll, dears,

The prettiest doll in the world;

Her cheeks were so red and white, dears,

And her hair was so charmingly curled.

But I lost my poor little doll, dears,

As I played in the heath one day;

And I cried for her more than a week, dears,

But I never could find where she lay.

I found my poor little doll, dears,

As I played in the heath one day;

Folks say she is terribly changed, dears,

For her paint is all washed away,

And her arms trodden off by the cows, dears,

And her hair not the least bit curled.

Yet for old sakes’ sake, she is still, dears,

The prettiest doll in the world.

43 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), The Prettiest Doll in the World, 5 July 1870, albumen print.

Kingsley’s child chimney-sweep Tom declares ‘what a silly song for a fairy to sing!’, but the verse clearly appealed to Carroll for its speaker’s memory of attachment to a lost and ruined doll. In his photograph Xie Kitchin appears in a dark ragged dress, with bare legs and arms. She is posed in an active attitude, looking off to her left, as if the movement of her body has been suddenly arrested. Damage to the negative gives the impression of perceiving the child through a peephole. This sensation further connects her with the doll she emulates, adding to the miniaturizing effect of the photographic medium.

Carroll makes a nostalgic gesture in naming a photograph of Xie Kitchin after Kingsley’s fictional doll from a verse in The Water Babies. In so doing he also voices, as he often does in quotations or captions accompanying photographs, complex forms of attachment as facilitated by the medium of photography: Kingsley’s doll is not only a ‘lost’ object, she loses her beauty. Stripped of all attractive artifice, almost unrecognizable but resistant to destruction, she remains for her owner for ‘old sakes’ sake’ a profound object of affinity. Commemorating Kingsley’s doll in a photograph Carroll dramatizes, here as elsewhere, photography as an apt medium by which to focus such loss. More generally, in repeatedly photographing little girls in fictional roles Carroll rehearses the loss that every photograph potentially embodies, which is also an eventual return of the subject via the image itself. In this sense, Carroll’s photograph The Prettiest Doll in the World exemplifies that more fundamental process of ‘lost’ and ‘found’ that photography ingeniously facilitates.

In his essay Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic (1911) Henri Bergson, in claiming that ‘we are too apt to ignore the childish element . . . located in our most joyful emotions’,60 makes direct connection to a child’s fascination for dolls and puppets:

one thing is certain: there can be no break in continuum between the child’s delight in games and that of the grown-up person. Now, comedy is a game, a game that imitates life. And since, in the games of the child when working its dolls and puppets, many of the movements are produced by strings, ought we not to find these same strings, somewhat frayed by wear, reappearing as the threads that knot together the situations in a comedy? Let us, then, start with the games of a child, and follow the imperceptible process by which, as he grows himself, he makes his puppets grow, inspires them with life, and finally brings them to an ambiguous state in which, without ceasing to be puppets, they have yet become human beings.61

In thus showing the genesis in children’s toys of certain comic types, Bergson concludes that ‘any arrangement of acts and events is comic which gives us, in a single combination, the illusion of life and the distinct impression of a mechanical arrangement.’62 For Carroll, photography highlights such a juxtaposition of lifelikeness and the mechanical. The photograph preserves the child as both natural and artificially animate.

LULU AND PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRESENTATION

LULU AND PHOTOGRAPHIC REPRESENTATION

At the most extreme end of Carroll’s interest in animated miniatures, mechanical toys and London theatre of the period is his attraction to child acrobats. On 19 June 1871 Carroll attended the Holborn Royal Amphitheatre to see the celebrated acrobat Lulu perform. Originally known as El Niño Farini, ‘the boy’ and biologically male child had his first international recognition in the 1860s as the young ‘son’ of the showman William Hunt (the Great Farini). An orphan adopted by Hunt, the boy named Samuel Wasgatt (1855–1939) made his debut in 1866 as a male performer. However, in 1870 Farini re-branded his protégé as ‘Lulu’, a female acrobat. Intrigue attached to Lulu’s gender until 1876 when she was apparently outed as male. Carroll’s diary entry for 19 June 1871 reads:

Went to town to go with John T. Faussett to the Holborn Amphitheatre . . . The Holborn performance was very good, partly circus, partly the ‘spectacle’ of Cinderella, which was very prettily acted in dumb show by about 50 children. The acrobatic feats of ‘Lulu’ were most wonderful of all: her ‘bound’ (where she is shot 25 feet up by machinery) was quite extraordinary (vi, 156).

44 Unidentified photographer, Lulu, 1870, albumen print.

He was not alone in remarking upon Lulu’s phenomenal acrobatic feats; ‘she’ was marketed as ‘the Eighth Wonder of the World’ in the popular press.63

In different ways, the following two images stage Lulu’s transformation from an androgynous ten-year-old to an apparently female sixteen-year-old performer. In the carte de visite photograph from 1871 (illus. 44), she is suspended by two wires that blend quite convincingly into the draped backcloth. Lulu clasps her hands behind her waist, such that her elbows form a 90-degree angle to her body. Her feet, by distinction, are drawn together and pointed. With chin raised, head poised and turned in three-quarter profile, Lulu looks off to her right with her fair curls drawn away from her face. She wears an all-in-one costume combining shorts and a low-cut bodice characteristic of circus attire of the period. The tonal contrast of the photographic image reveals the satin fabric of her costume against which her pale legs glow in their flesh-coloured tights.

The colour lithographed playbill by Alfred Concanen (illus. 45), by contrast, depicts Lulu as if in flight, a full-length figure hovering in a sky that, with crescent moon and emerging stars, conveys twilight. The logo ‘LuLu’, with its compact symmetry, is picked out centrally in bright emerald green at the top of the playbill: the lower case ‘u’ suspended trapeze-like above the capital ‘L’ that supports it. These decorative features, along with the advertisement of the days and times of the shows that runs along each side of the border, testify to the pedigree of her performance as confirmed in the caption at the bottom: ‘As she appeared before Their Royal Highnesses, The Prince & Princess of Wales, Feby 20th 1871’.

But the image also readily offers up details, most essentially those of colour, lost to the monochromatic photograph. Lulu’s indelibly green outfit – trimmed with white ruche – together with her emerald slippers allow a viewer a glimpse of the polychromatic spectacle of the performance. In other words, the playbill supplements colour, alien to the photograph. At the same time, the undeniable match-up of costume in the lithograph and the photograph assures a viewer to some extent of the visual ‘authenticity’ of Lulu’s stage persona: the long curly hair, the curve of her breasts and line of her waist as emphasized by the frills on the bodice confirm the photograph must be ‘her’. Yet, in a bold lie by a camera reputedly incapable of subterfuge, the ‘her’ turns out to be a ‘him’. Such travesty, arguably easy to detect in the photograph, is not so in the lithograph.

45 Alfred Concanen, LuLu, playbill, 1871, lithograph.

In both the playbill and photograph Lulu appears suspended. Her feet do not touch the ground. Yet while the former conveys Lulu’s weightlessness, the latter emphasizes her body as subject to gravity. The lithographed playbill turns her into a weightless sylph. In the photograph, by comparison, with her body drawn in, Lulu appears to hang rather than to fly. Accentuating the strength of her cross-dressed form, her pose encodes her as an acrobat. Thus, while the lithograph emphasizes Lulu’s ethereal nature, the photograph makes no attempt to contextualize her presence.

Lulu’s fabled bound evokes the capacity of dreams to launch a subject into flight. In ‘The Dream-work’ in The Interpretation of Dreams, referring to ‘the second group of typical’, Freud focuses upon those commonplace dreams in which ‘the dreamer flies or floats in the air’.64 While he maintains that the meaning of such dreams is different in every instance, that ‘it is only the raw material of sensations contained in them which is derived from the same source’, Freud importantly finds that such dreams ‘reproduce impressions of childhood’. More specifically, ‘they relate, that is, to games involving movement, which are extraordinarily attractive to children’.65 In the following quotation it is tempting to read for ‘uncle’ the avuncular Lewis Carroll fond of the rough and tumble of child’s play:

There cannot be a single uncle who has not shown a child how to fly by rushing across a room with him in his outstretched arms, or who has not played at letting him fall by riding him on his knee and then suddenly stretching out his leg . . . Children are delighted by such experiences and never tire of asking to have them repeated, especially if there is something about them that causes a little fright or giddiness. In after years they repeat these experiences in dreams; but in the dreams they leave out the hands which held them up, so that they float or fall unsupported. The delight taken by young children in games of this kind (as well as in swings and see-saws) is well known; when they come to see acrobatic feats in a circus their memory of such games is revived.66

Photographs hold the capacity to represent the circumstances of such play, of acrobatic spectacle, for example, as reviving in the adult memory a child’s delight in flying or being floated into the air. In See-saw, Carroll’s 1860 photograph of Alice and Lorina Liddell (illus. 46), Alice is pictured elevated while her younger sister Edith, who appears to be providing the weighted end, has been cut by cropping to an oval format. Such photographic staging of children’s play cannot present the sensation of motion in the manner of a dream but the medium may, along with the adult’s experience of acrobatic feats, generate opportunities to ‘revive’ in memory such childish games. While a desire for pleasurable experiences of movement works itself out in repetition in dreams, Carroll’s and others’ marvel at Lulu’s brave feat of being catapulted high into the air is in part a response to unconscious triggers for such ‘play’.

46 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Lorina and Alice Liddell, ‘See-saw’, 1860, albumen print.

Yet Carroll was not simply fascinated by the spectacle of Lulu’s virtuosity. He was attracted to acrobats’ clothing for photography. Jennifer Forrest cites Yoram S. Carmels, who notes that ‘even when circus people are photographed or portrayed in their off-stage mode, they are still always on stage’.67 In acquiring photographs of acrobats, and in dressing up children in acrobats’ clothing to photograph, Carroll simulates ways in which such performers bring the stage with them. A photograph of Lulu, therefore, evokes not only her miraculous ‘bound’ but the supporting ‘dumb show’ of Cinderella and the audience’s long ‘wait’ for, and anticipation of, the main act. Photographs of acrobats arrest the memory of a compound spectacle.

Nevertheless, the sight of Lulu had a practical impact upon Carroll’s photography. No longer remaining simply content with capturing children in acrobats’ costumes in static poses, Carroll was prompted to attempt to capture their movement. Vitally important in this respect is his diary entry for 27 June 1871, made shortly after seeing Lulu: ‘Then I called on Faulkner, the photographer, and agreed to buy his machine for taking children quickly’ (vi, 161). Robert Faulkner & Co., photographer, had premises at 46 Kensington Gardens Square, Westbourne Grove, until the end of 1876 and then at 21 Baker Street, Portman Square, and is remembered for his portraits of young children. The spectacle of Lulu the previous week was directly responsible for Carroll’s wish to obtain such a camera. Furthermore, Carroll’s desire for a camera dedicated to capturing movement confirms his specific interest in the animation of the small weightless performer.

But Lulu’s graceful aerialist feats that miraculously defy gravity are also crucially bound to gender via cross-dressing. Transformed from androgynous boy to girl acrobat, Lulu incites the added thrill on the part of the spectator of seeing a ‘girl’ performing physically dangerous actions. As Jennifer Forrest points out: ‘Travesty is an old circus tradition, and the travesty of a male as a female occurs most often, perhaps for the purpose of enhancing the spectator’s gendered perception of the perils to which the acrobat exposes him/herself.’68 Yet, as Forrest further indicates, it tended to be customary for ‘most male travesties [to] eventually reveal their identities’, most commonly at the end of a performance, but:

Miss LuLu, who debuted in Paris in 1870, never did settle the question of her true sexuality. The degree of difficulty of her aerial feats – the saut en fusée (‘rocket jump’) at twenty three feet above the ground, and possibly even the triple saut périlleux, on the flying trapeze . . . – suggested she was a male acrobat.69

Indeed, ‘every contemporary critic who discussed Miss LuLu – and anyone who saw photographs of her, for that matter – remained convinced, however, that she was a man’.70 There existed, therefore, a kind of open secret about Lulu’s biological gender that photography was apparently able to reveal. It was a ‘truth’ easily disguised for the naked eye. Yet the ample evidence confirming the camera eye did not disclose details unavailable to a discerning unmediated eye, thus complicating a view that the camera possessed a capacity to see ‘through’ such dissembling.

A columnist in the Sporting Times, for example, takes liberty in exploiting to comic effect attempts to conceal Lulu’s gender: ‘if Lulu the Beautiful be not El Niño Farini, there is no more truth in manhood in me than a stewed prune’. He continues to relish the opportunity for innuendo:

It is no use to point out to me that – well – much development has taken place in various portions of the young person’s anatomy since he – or she – swung and bounded as a boy at the Alhambra. Age will do much. Wadding will do more. Rotundity and grace are new matters of art, to be bought like blushes or eyebrows; very soon, probably, to be let out like dress suits and rout chairs, for the evening . . . In the meantime I assert Lulu and El Niño to be one, whether she was a boy, or he was a girl, or – but these wild speculations are dangerous and not decorous.71

Given Lulu’s sensationalism as a source of comic speculation and sexual innuendo, it might appear odd that Carroll sought to go to see her. Lulu was so popular, commanding multiple classified advertisements, that it would have been impossible for him to overlook the fact that she approached the limit of what he regarded as respectable entertainment.

It is well known that acrobats’ costumes, in particular flesh-coloured tights that gave the appearance of naked legs, revealed their bodies in ways not normally available to public view.72 There was a fine line, therefore, between a spectacle such as Lulu’s at the Amphitheatre and those of ballet girls at the Alhambra with their offshoot photographs offered for sale at print sellers. Owing to its lowbrow entertainment, and the nature of its clientele, Carroll famously drew the line at the music hall, professing never to have entered one. However, in the context of his interest in Lulu, such a distinction is somewhat ironic since some individual acts of virtuosity originating in the theatre subsequently migrated to the music hall.

Yet, in further significant ways, the celebrated ‘Lulu’ highlights Carroll’s wider interest in acrobats and the cross-dressing of girls as boys, while reminding us that disguise of boys as girls is more easily undone than, in their burlesque garb of breeches, girls disguised as boys. Carroll’s interest in Lulu throws light onto his frequently cited remark of 5 August 1888 to Henry Savile Clarke that while he did not admire boys cross-dressed as girls – ‘boys must never be dressed as girls’ – ‘girls make charming boys’.73 Anne Varty cites the theatre reformer of the late century, Ellen Barlee, who she claims ‘thought that cross-dressing disguised neither sex nor gender, but emphasized both’.74 But if, in this context, Carroll’s reason for admiring cross-dressed girls was that male costume emphasized their biological gender, doesn’t the case of Lulu confirm that, provided he was unaware of the dissembling, a cross-dressed boy might work just as well?

‘MADEMOISELLE ELLA’ AND CONNIE GILCHRIST

‘MADEMOISELLE ELLA’ AND CONNIE GILCHRIST

Carroll’s astonishment at Lulu was not without precedent, for he had earlier enjoyed ‘Mademoiselle Ella’, an extraordinary female rider with The Grand Equestrian American Circus. Indeed on 1 July 1857 he notes having gone with his brother Skeffington to the circus at Drury Lane specifically ‘to see “the little Ella again”: She is no longer little, but as active and graceful as ever. We did not stay out the performance, which was only average in quality’ (iii, 76–7). In watching her perform, Carroll was among audiences thrilled by a combination of grace, bravery and physical virtuosity.

‘Mademoiselle Ella’ was later described by Edward Stirling as surprising spectators by ‘her marvellous evolutions on two, three, and four horses running at full speed round the ring. The leaps that fair equestrian took, clearing four horses at a time, astonished and attracted large audiences.’75 Anticipating the later Lulu, however, he goes on to elaborate: ‘It was whispered abroad that mademoiselle was not really a mademoiselle at all but a monsieur in disguise. Certainly few persons ever saw the lady’s features in the day: they were always closely veiled.’76 In the ‘monsieur’ masquerading as a ‘mademoiselle’, her biological gender links the performer ‘Little Ella’, as Carroll tellingly calls her, with the later ‘Lulu’. Anticipating the reinvention of El Niño as Lulu, the gender of ‘Little Ella’ is rumoured to be male.

Carroll enjoyed on other occasions the types of aerialist and equestrian feats performed by Lulu and Mademoiselle Ella; at a much later date he attended the somewhat unlikely extravaganza of Laura Saigeman’s swimming entertainments in Eastbourne. However, six years after seeing Lulu, in 1877, Carroll remarked upon his first sight of the child actress Connie Gilchrist (1865–1946) at the Adelphi on 13 January in the pantomime Goody Two-Shoes, enacted entirely by children: ‘the Harlequin was a little girl named Gilchrist, one of the most beautiful children, in face and figure, that I have ever seen, I must get an opportunity of photographing her’ (VII, 13–14). Connie Gilchrist became a well-known actress specializing in burlesque. In seeing her perform what became her fabled ‘skipping rope dance’, Carroll immediately documents a desire to photograph her. On 3 March he records: ‘Heard from Mrs Gilchrist, mother of the “Harlequin”, accepting my offer of Alice, and sending the name – “Constance MacDonald Gilchrist,” born Jan. 23 1865. I sent one with acrostic verses on “Constance” (VII, 22). As a preface to photographing the child, forever afterwards present to him as ‘the Harlequin’, Carroll requests Connie Gilchrist’s full name in order that he may record her presence in the pattern of an acrostic. Here, the encoded form of the acrostic serves as shorthand for recording, and a prelude to photographing the child.

In the light of Carroll’s response to the Living Miniatures and Lulu, Connie Gilchrist provides a case study of a London performer who became meaningful to him at this period of his life because, by way of contemporary painting, she connected theatre with photography. As a model for painters she was not exempt from the disreputable associations for a woman of such an occupation. Gilchrist crossed the class divide of respectability. Frederic Leighton painted her on many occasions; she modelled for him from the age of six, later appearing as Little Fatima (1875); as the model for all the young girl figures in the chorus of The Daphnephoria (1876); in The Music Lesson and Study: At a Reading Desk (both 1877); and in Winding the Skein (1878). Carroll enjoyed her metamorphosis from canvas to stage. James Abbott McNeill Whistler also famously painted Connie Gilchrist in her fabled ‘skipping rope’ role. In a life-size portrait entitled A Girl in Gold, later changed to Harmony in Yellow and Gold, he depicts her aged twelve in the short yellow tunic and high boots worn in her ‘skipping rope dance’ at the Gaiety (illus. 47). The child’s roles as stage performer and artist’s model increased her desirability as a model for photography.

47 James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Harmony in Yellow and Gold: The Gold Girl – Connie Gilchrist, 1876–7, oil on canvas.

Significant in this regard is Carroll’s record of taking Connie Gilchrist to the Royal Academy on 2 July 1877 to see Leighton’s paintings of her, The Music Lesson, in which she modelled as a girl learning to play a Turkish saz, and Study: At a Reading Desk, in which the child pores over a copy of the Qu’ran. In a real-life version of his dream of taking Polly Terry to see her older self perform, Carroll enjoys witnessing Gilchrist’s pleasure in seeing herself visually represented. In a sense, her narcissistic enjoyment justifies his wish to photograph her that, as he acknowledged in his diary, ran to excess. Indeed, referring to Connie Gilchrist a second time, he claims she is ‘about the most gloriously beautiful child (both face and figure) that I ever saw. One would like to do 100 photographs of her’ (vii, 29). Multiples of photographs represent the most reliable method Carroll knows of capturing what it means to watch Connie Gilchrist perform.

Yet a little over a year later, on 2 October 1878, Carroll comments in his diary upon a change in her appearance: ‘saw Little Dr Faust at the Gaiety: Connie Gilchrist was “Siebel”: she is losing her beauty, and can’t act – but she did the old skipping-rope dance superbly’ (vii, 140). She was thirteen at this point and, given the context, it is difficult not to read in terms of the onset of puberty what Carroll refers to as her loss of beauty. And yet in his rejoinder, ‘she did the old skipping-rope dance superbly’, Carroll’s claim rings with a sort of relief that, in spite of an inevitable loss of beauty, Gilchrist’s animated form as encoded in the dance will remain unaffected by physical maturity. Carroll extracts the highlight, Gilchrist’s skipping rope dance, from the entire performance. Animation is key to the appeal of the winning routine. It does not simply show off the child’s beautiful body. It shows her body moving in particular ways.

There is no verifiable photograph of Connie Gilchrist by Carroll, although many cartes de visite taken of the actress in professional studios survive. The following images give a sense of Carroll’s investment in her. The first carte shows a pared-down shot of her face in close-up (illus. 48). In the second publicity studio shot the young actress is pictured in elaborate attire, with the wooden handles of her signature skipping rope dangling from a table on the left-hand side of the image (illus. 49). This is Connie Gilchrist as Carroll would have seen her; the photograph conveys the elaborate nature of one of her get-ups that reveals parts of her body to androgynous effect.

48 Elliott & Fry, Connie Gilchrist, 1870s, albumen carte de visite.

49 Unidentified photographer, Connie Gilchrist, 1870s.

When Carroll’s personal effects were auctioned following his death, theatrical costumes featured in the list. Some were acquired by the Art and Antique Agency, 41 High Street, Oxford, and the following were advertised in its catalogue: ‘Fancy Dress, Used by Lewis Carroll’s Child Friends’. These included two ‘Fairy Prince Suits’ (one green satin and one crimson velvet); ‘Turkish Maiden Suit’; ‘Georgian Court Dress’; ‘Chinese Mandarin’s Robe’; ‘Red Fez’; ‘Basket of Flowers, two muslin caps, blue serge bodice, red and white cotton skirt (some being part of Dolly Varden costume)’.77 As this record and others testify, in a palpable sense, as photographs do, costumes serve as memorials to individual child performers and theatrical events. Indeed, they are in certain ways interchangeable. But they also preserve qualities lost to the photograph, most notably colour. The skirt, worn by Xie Kitchin as ‘Penelope Boothby’, is ‘red and white cotton’.

On several occasions Carroll had women friends, or the mothers of his child friends, make costumes specifically for him. While not unusual among painters, such practice further demonstrates how carefully he contrived and stage-managed in advance roles for his child ‘sitters’. Thus, on 26 June 1878 Carroll notes: ‘called on Mrs Coote, and borrowed Carrie . . . Took her home and arranged with Mrs Coote to sell me three old theatrical dresses of Carrie’s besides the new prince’s dress she is making for me’ (vii, 118). Moreover, since he often sought to reproduce roles that were interchangeable, a photographic session was very much about inhabiting costumes. For example, on 5 June 1871 Carroll refers to Chinese dress, borrowed from Mary Foster née Prickett, formerly governess to the Liddell children. On 21 March of the following year he notes: ‘called on Mrs Price to see the Greek dress she has made for me’ (vi, 205). Three girls were photographed in it: Beatrice Fearon on 3 May 1872, Julia Arnold on 20 May 1872, Xie Kitchin on 14 May 1873 (vi, 205). While it has been suggested Carroll bought such clothing ‘for use by models in his photographs to enhance the dramatic authenticity of his work’,78 as I have shown, Carroll invests in theatrical costumes in nuanced ways, some of them at a remove from ‘dramatic authenticity’.

But Carroll also became attached to items of clothing worn by particular performers. Functioning as keepsakes, binding powerful memories, costumes additionally operate like photographs. Indeed, Carroll’s enthusiasm for costumes increased in the 1870s and this was the period in which he produced the largest number of costume photographs. In a letter of 13 February 1878 to the mother of Sallie Sinclair, whom he had seen as Cupid in the pantomime Robin Hood at the Adelphi on 8, 10, 15 and 17 January of that year, after expressing the hope the child will ‘escape the self-consciousness and thirst for admiration which so entirely spoils the naturalness and attractiveness of some beauties’, Carroll changes tack:

I take this opportunity of asking one more question. Is the ‘Cupid’ dress your own? And shall you have it in usable condition (say) at about Easter? And do you think you could then manage to bring her to Oxford for a day? I should very much like to get her into my studio, and take a lot of photographs of her, as ‘Cupid’ and in any ways you liked. I sometimes use glasses 10 inches by 8, and so could do a large picture of her.79

That question burgeons into three. It is not simply about a particular piece of theatrical clothing but also about what has come to attach to it. Crucially, Carroll stresses his wish ‘to take a lot’ of photographs of the child in this garb. His motive for creating such photographs becomes clear when he writes again to Mrs Sinclair with a different scheme in mind: ‘I have thought of a plan by which I can at once do you a photograph of Sallie, if you don’t mind the trouble of taking her to Haverstock Hill.’80 The suggestion is that the artist A. B. Frost ‘would make a drawing of “Cupid”’ and that Carroll would subsequently photograph it since, as he reasons, ‘drawings generally photograph extremely well’. The costume is vital to the representation: ‘If you consent to this, could you take her (and the ‘Cupid’ dress) on Saturday’.81

The intricacy of this proposed arrangement suggests an urgency to Carroll’s wish to have Sallie pictured photographically in the ‘Cupid’ dress. To that end, even a visual image at one remove from Carroll’s photograph will suffice. Moreover, by suggesting that he photograph a drawing of the child in the costume, Carroll is plainly most interested in harnessing the reproductive capacity of photography to commemorate the dress. While there exists no record of this photograph, another child, Arthur Hatch, appeared as ‘Cupid’ in an earlier photograph by Carroll.82

In the complex correspondence of theatre and photography, major importance accrues to the small body of the child in costume. On certain occasions, as I have demonstrated, the figure of a diminutive performer undergoes curious conceptual metamorphosis into the form of a doll or a clockwork toy. Moreover, it is specifically by means of the agency of photography that Carroll explores potential similarities between child performers and toys. Moving in reverse order from Sallie Sinclair, Connie Gilchrist, through ‘Little Ella’ and ‘Lulu’ to the Living Miniatures, the child inhabits a range of roles. Cross-dressed as a boy, a girl, an acrobat and in fairy garb, each of these examples from the London stage demonstrates the significance for Carroll of the child in theatrical costume. In an important regard costumes serve as props for his photography. It is conceivable, therefore, that once visually recorded, their physical existence no longer required, costumes might be discarded. But this was not the case. Nor did costumes lose significance when Carroll was no longer taking photographs in his Christ Church studio. Instead, he held on to them. Although like photographs, costumes would eventually fade, as material objects in their own right they preserved those imaginary and fantasy worlds to which they were originally connected. Not simply props for photographs but complementing them, retrospectively for Carroll costumes attached both to theatrical events and to those photographs subsequently generated to commemorate those events. As Carroll enjoyed the conceptual oscillation between the animate (performing) and inanimate (photographed) child performer, her costume itself embodied for him profound attachment to both photography and theatre.

Although the London theatre was a hugely important part of Carroll’s life, the miniature performer in the range of guises explored was one of its biggest draws. And she was so in large part because Carroll saw in her the capacity to be turned into a photograph. However, that transformation was an intricate one. Carroll did not aspire to simply take photographs of stage children in their roles. Instead, his wish to photograph them was mediated by their capacity to resemble a number of inanimate miniature forms such as dolls. While his childhood doll ‘Tim’ remained an object of childhood attachment worthy of a photographic portrait, an artist’s lay figure suggested a life-sized replica of a child to photograph. Carroll was equally fascinated by the graceful animation of the marionette and the very different stop/start mechanism of the clockwork toy. As I’ve shown, the medium of photography provided a means of capturing them. But the notion of ‘capture’ here is no simple matter. For Carroll creates complex processes of visual metamorphosis from stage to photographic print in which so much more is being represented in the child donning costumes than a theatrical scenario. Indeed, in its relation to the theatre, as in other aspects of his quotidian existence, Carroll invested the camera with a magical capacity to encode in both animate and inanimate miniature forms fluctuation between motion and stasis. With its paradoxical potential for metamorphosis, the ‘still’ photographic image became oddly commensurate with the vitality of the child performer. Photography preserved the coiled spring of motion ready to be reactivated at some future moment.