Carroll in Russia: Shopping for Photographs and Icons

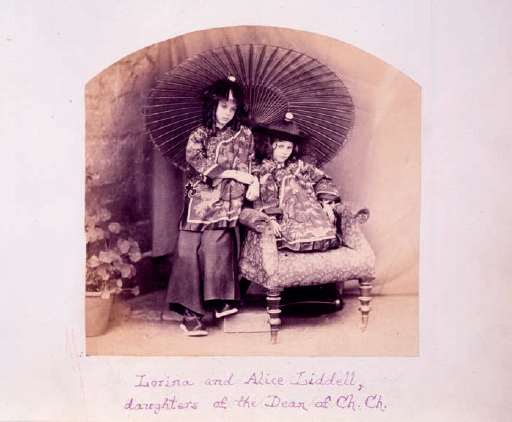

TWO CHILDREN IN IDENTICAL Chinese dress pose outdoors in front of a canvas backdrop (illus. 50). The elder, standing with her left foot raised on a wooden block, supports an open adult-sized parasol that rests over the back of a chair upholstered in Paisley fabric. Her sister sits squarely in the seat, legs drawn up under her. A potted geranium intrudes into the left-hand side of the print; so too does part of a stone wall that has escaped the cover of the backdrop. Stowed under the chair, a spare cushion further discloses the makeshift studio space just as the ruffled silk of one of the Manchu hats, conspicuously lacking a brim, compromises the authenticity of the Chinese costume. Taken in the spring of 1860, in the Deanery garden at Christ Church, Lorina and Alice Liddell in Chinese Dress took pride of place as the second photograph in Carroll’s large album A(ii).1

From March 1872 Carroll produced in the unadorned space of his ‘glass-house’ at Christ Church an increasing number of photographs of children masquerading in ethnic costumes.2 However, such ‘costume’ portraits from the 1870s were not simply owing to that purpose-built space, or the presence of theatrical and artistic influences he experienced in London. They were also the result of a monumental trip he made by train in the summer of 1867. Visiting Russia between July and September of that year, on what would be his only time abroad (and accompanied by his life-long friend, the renowned preacher Henry Parry Liddon), Carroll encountered in close proximity a diverse range of ethnic groups, alongside representations in contemporary cartes de visite, that shaped his subsequent photographic work. He did not take his camera with him on the Russian visit. Although his state-of-the-art portable Ottewill was comparatively small, the cumbersome nature of the accompanying equipment and chemicals would have made extended journeys by railway difficult.3 In Russia, in the absence of his own camera, Carroll hunted for photographs and recorded a wish to buy them. Indeed, on the lookout for cartes de visite at every opportunity, he frequently, if briefly, recorded their presence in the journal he kept in two notebooks.4 Liddon also kept a diary of the visit and on more than one occasion, sometimes with a sense of mild irritation, noted his travelling companion’s regular habit of ‘shopping for photographs’.5

50 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Lorina and Alice Liddell in Chinese Dress, 1860, albumen print.

None of the photographs Carroll bought on the Russian trip are known to have survived. Along with most other purchases they remain only as references in the diary. On his return home, however, distinctive aspects of the Russian experience combine in the staging of his photographs. Not only does Carroll increasingly dress up children for photography in costumes of those ethnic and national identities encountered on the visit, but he produces photographs embodying formal elements of contemporary nineteenth-century Russian cartes de visite. In addition, having encountered such photographs for sale alongside copies of Russian Orthodox icons, Carroll incorporates into his work post-Russia the suggestive proximity of the two types of souvenir. More emphatically, the shared capacity of ancient icons and popular cartes to generate physical traces of their referents newly informed Carroll’s attachment to metaphysical properties of the photographic medium.

While critics have paid little attention to Carroll’s Russian visit, maintaining it had little impact upon him since he never again travelled abroad,6 the rich visual experience of religious icon and secular photographic ‘type’ meant that after 1867, in revisiting Chinese and other costume photographs, Carroll contrived scenarios both formally and conceptually different from that realized in Lorina and Alice Liddell of 1860. Most noticeably he combined the distinctive material forms and metaphysical resonances of ‘photograph’ and ‘icon’. He did so in his increasing preference for photographing individual female children dressed in ethnic costume in interiors devoid of the decorative trappings of nineteenth-century studios.7

Carroll set out on his Russian visit on 12 July 1867, meeting Liddon at Dover to sail to Calais the following morning. En route the tour took in the cities of Brussels, Cologne, Berlin, Leipzig, Warsaw and Paris, where Carroll and Liddon visited the International Exhibition. The pair arrived in St Petersburg on 27 July, remaining in the city before catching the train to Moscow on 2 August. On 19 August they set off back to St Petersburg, where they remained until 26 August. Permanently poised between Asia and Europe, with its complex history of being invaded from east and west, the Russia that Carroll encountered comprised more than a hundred different ethnic groups. Moreover, it represented, as he himself claimed, an ‘ambitious’ destination for someone ‘who ha[d] never yet left England’ (v, 253). Liddon’s visit had a distinctly religious purpose: to experience at first hand the power of Eastern Orthodoxy. Along with William Palmer (1811–1879), Robert Eden (1804–1886) and Frederick George Lee (1832–1902), Liddon was a member of the Eastern Church Association, founded in 1863.8 Travelling at a time when the Russian Orthodox Church had become a key point of focus for church historians, the trip enabled him to conduct an unofficial inquiry into the issue of reunification. Carroll, on the other hand, in spite of having been ordained Deacon in 1861, had made his decision in 1862 not to proceed to full Holy Orders. Although not holding the High Church sympathies of his friend, Carroll was curious, however, about those aspects of ritualism with which he himself was at odds, and he went along with Liddon on many Orthodox Church visits.

Carroll’s Russian diaries function in important ways to negotiate his status as a ‘foreign’ traveller in a country undergoing profound political and demographic change. Closer to his fictional writing than the spare prose of his regular diaries, Carroll’s Russian memoir records the scrapes of the monolingual English tourist. Intrepid droshkie drivers and hotel waiters – unrelentingly promising ‘ze cold ham’ and ‘catching at the word [coffee] as if it were a really original idea’ – bear the weight of his sarcasm, marking the pages with a light-heartedness often found in Carroll’s letters (v, 275). Enjoying the rail journey, he is fascinated by the ‘elaborate conjuring trick[s]’ (v, 299) of train guards who produce beds from seatbacks and, equally, by the contortions of the language. On conversing with an English gentleman on the train from Königsberg to St Petersburg, Carroll notes an ‘extraordinarily long’ and ‘alarming’ Russian word, the English transliteration of which – ‘zashtsheeshtshayoushtsheekhsya’ – confirms his ‘rather dismal prospects’ of ‘pronouncing the language’ (v, 282–3). Moreover, the journal includes the occasional spontaneous sketch, such as the ‘cruet-stand’ formation of a church, to impress the superiority of hieroglyphics over speech.

The trip was fascinating for both men, not least for its timing. In 1861, just six years earlier, the Liberation of the Serfs had occurred in Russia, an event that had a major social and political impact upon the fabric of life. The emancipation of more than twenty million peasants was visibly evident throughout the country as itinerant workers searched for labour. Especially conspicuous to a European traveller was the influx of former serfs to the major cities of Moscow and St Petersburg. Yet Carroll travelled to Russia not only at a key moment of political reform but at a point at which major cities more generally were seeing massive physical transformation. St Petersburg and Moscow both presented remarkable examples of metropolitan centres with their mixture of peoples and particular cultural institutions. Although very different cities – St Petersburg, Peter the Great’s ‘window onto the West’, active as the main capital, and Moscow historically Slavophile – Carroll found them equally captivating. By the 1860s the building of the centre of St Petersburg was largely completed ‘plac[ing it] and Russia [architecturally] in the vanguard of the entire neoclassical movement’.9 Moscow, on the other hand, had ‘no clear pattern to the streets’ and it retained buildings and monuments ‘that linked the nineteenth century with the medieval past’.10

Carroll pronounced Moscow ‘a wonderful city’:

of white houses and green roofs, of conical towers that rise one out of another like a fore-shortened telescope; of bulging gilded domes, in which you see as in a looking-glass, distorted pictures of the city; of churches which look, outside, like bunches of variegated cactus . . . and which, inside, are hung all round with Eikons and lamps, and lined with illuminated pictures up to the very roof (v, 300–301).

In a sentence likening the architectural wonders of Moscow to the physical appearance of a telescope (and he carried his telescope with him on the trip), Carroll employs the simile of ‘a looking-glass’ to detail the mediating wonders of those ‘bulging gilded domes’ that produce ‘distorted pictures of the city’. Thus, recalling the ‘shutting-up’ reflex of the telescope from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), the simile metamorphoses to anticipate the looking-glass ‘pictures’ of Through the Looking-Glass published four years after the Russian visit. At the same time, visually conspicuous churches assume a metaphysical brilliance: their magical external effects anticipate the imagined visual treats awaiting a traveller on the inside, a plethora of icons burning in their dark interiors.

By contrast, but equally significantly, the formidable architectural presence of St Petersburg – the biggest port and one of the most important industrial, trade and financial centres of the country – profoundly affected Carroll. On first arriving there after an epic train journey of more than 28 hours, he notes the ‘wonder’ and ‘novelty’ of the monumental city: ‘the enormous width of the streets (the secondary ones seem to be broader than anything in London)’ (v, 284).

A SERF ON THE STAGE

A SERF ON THE STAGE

While, prior to the visit, Carroll had not expressed a particular interest in Russian history or culture, his approach to Russian life was refracted through the prism of contemporary British theatre, in the form of Tom Taylor’s The Serf, or Love Levels All, which he went to see at the Olympic three times during July 1865.11 That drama was itself commemorated photographically in contemporary cartes de visite that Carroll bought. A drama in three acts with Henry Neville, Kate Terry, Horace Wigan and H. H. Vincent in the principal roles, The Serf portrays Russia prior to the emancipation of the serfs, exploring themes of enslavement and peasant uprising. In a diary entry for 3 July 1865 Carroll comments on enjoying The Serf, while pronouncing the moral ‘very hazy’ (v, 85). On this day Carroll also ordered several photographs of the Terrys at Southwell’s shop. Theatricality regularly spoke to Carroll’s interest in purchasing photographs and, although there exists no record that those images he bought captured Kate Terry in her role from The Serf, a number of studio images of her in that 1865 performance survive (illus. 51).12 Moreover, as exemplified by Carroll’s wish to buy cartes of Kate Terry, the relationship of photographic portrait to dramatic spectacle is for him a complex one whereby the photograph supplements the theatrical experience and vice versa. Carroll went to see The Serf once more on 15 July, and again on 19 July, when he claims in his diary: ‘I like The Serf better every time I see it’ (v, 97).

51 London Stereoscopic Company, Kate Terry and Henry Neville in‘The Serf’, July 1865, albumen print.

While, as already noted in the previous chapter, Carroll frequently saw the same theatrical production on more than one occasion, The Serf becomes retrospectively significant following his documentation of the Russian tour that assimilates topographical and conceptual concerns of the drama. Indeed, the documentation in Carroll’s journal of village churches with their characteristic ‘dome and stars’13 might be straight out of The Serf. So, too, might be Carroll’s diary record of ‘the occasional apparition of a peasant in the usual fur cap, tunic and belt’ as marking the only interest in the ‘flat’ landscape from ‘the Russian frontier to Petersburg’ (v, 283). The play traces the eponymous ‘Serf’, Ivan Khorvitch, who, having disguised his identity, becomes an artist in Paris and falls in love with a Countess, Madame de Mauleon. His Russian nationality is soon revealed to the vengeful Karateff, however, who plots to undo him by exposing his enslaved state. At the point where his serfdom threatens to thwart his love, however, Ivan is revealed to have been a prince all along and Carroll consequently called into question whether, with the Serf restored to noble birth, any ‘levelling’ had in fact taken place.

Carroll’s Russian journal entries, which disclose a wish to record cultural differences visually, find precedent in the drama. In Act II of The Serf the Countess’s ethnographic curiosity about visiting an ‘authentic’ peasant cottage marks an important point in the plot that is mimicked in a visit Carroll records in detail in his diary for 15 August. In both cases the occasion attracts the eye of the artist desiring a picturesque subject, and the perspective of the ethnographer cataloguing visible difference. Madame de Mauleon, ‘curious’, as she claims, ‘to penetrate one of the serf’s huts’, demands her servant make a ‘sketch’ of the ‘cabins’.14 Carroll, by comparison, en route to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, or ‘New Jerusalem’, is so intent on sketching the scene of ‘a peasant’s cottage’ to which he and Liddon had applied ‘for bread and milk’ – as a pretext for seeing the interior and their ‘mode of life’ – that Liddon becomes perturbed at ‘losing ¾ of an hour’ in their onward journey to Voskresensk.15 After ‘two sketches’, one of the inside and one of the outside with the family group of ‘six of the boys and a little girl’, Carroll notes ‘it was very interesting to be able to realise for oneself the home of the Russian peasant’ (v, 326). Nevertheless, to sketch the scene turns out not to be enough; Carroll bemoans his lack of a camera, pronouncing the group a ‘capital’ subject ‘for photography’ but ‘rather beyond [his] powers of drawing’.

While Carroll’s attempted act of drawing reminds him of his attachment to photographing, The Serf vocalizes fundamental differences of photography from the hand-generated medium of painting when Ivan in his Paris studio, surveying the portrait of his model, claims ‘I could pitch brushes and palette to the devil when I measure what they can do with the face I carry in my heart.’ However, as the disguised Serf further contrasts the action of photography with his inability to convey the face of the beloved – ‘Oh! If I could only paint as the sun does, with a flash, and strike her living image from my soul upon the canvas! But I must toil, and toil, and feel her loveliness farther and farther beyond my reach’16 – he does not simply lament a likeness lost to his inferior powers of painting. He also recognizes the ability of photographic ‘sun’ painting to bring the original near, to realize ‘with a flash . . . the living image’ and transfer its metaphysical qualities to physical form. While travelling abroad Carroll experienced afresh the miraculous agency of photography.

SHOPPING FOR CARTES

SHOPPING FOR CARTES

In Russia Carroll substituted a perpetual impulse to ‘buy’ photographs for a lack of opportunity to ‘take’ them. In part, while enjoying the unique material and spiritual experiences of Moscow and St Petersburg, Carroll shops for photographs – as one might expect a typical nineteenth-century traveller to do – as mementos of those sights and works of art seen. Indeed shops, with their ‘enormous illuminated signboards’, are clearly a draw for Carroll in Russia as they had regularly become in London. His attraction to them resembles Leigh Hunt’s earlier fascination in which he likens the variety of London retailers to the bazaars of the ‘Arabian Nights’.17

Armed with a map and ‘a little dictionary and vocabulary’ (v, 289), Carroll strolled tirelessly around St Petersburg, an activity he claimed was ‘like walking about in a city of giants’ (v, 292). He pronounced the city ‘so utterly unlike anything [he] had ever seen’ that he ‘could (and) should be content to do nothing for many days than roam about it’ (v, 288). His ‘roam[ing]’ took him to the city’s many photographic studios. Indeed, as Charles Piazzi Smyth, Scotland’s Astronomer Royal and amateur photographer, noted eight years earlier in 1859 when visiting St Petersburg: ‘there is scarcely a more frequent sign to be met with along the principal streets than PHOTOGRAPHER; and all the specimens exhibited outside the studios, chiefly large-sized portraits, were amongst the finest things we have ever seen in that line’.18 Smyth’s reference to the display of photographs ‘outside’ the studios chimes with J. G. Köhl’s earlier observations of the city in Panorama of St Petersburg (1852). Köhl claims that, unlike Paris and London where ‘placards and colossal letters’ advertise to passers-by the wares of particular shops, St Petersburg with its ‘extremely limited reading public’ relies largely on ‘an abundance of pictorial illustrations’ to advertise its wares.19 Contemporary nineteenth-century Russian newspapers and journals document that by 1859, ‘in St. Petersburg alone’, the large number of photographers made them ‘difficult to name’.20

Prominent among those photographic images available were studies of Russian peasants by the Scottish photographer William Carrick (1827–1878), whose name was transliterated as B. Kappuk. It is likely that Carroll encountered examples of the photographic series of ‘Russian Types’, pictured according to their professions, that Carrick produced in carte de visite format between 1859 and 1878.21 Carrick’s studio was ‘on the top floor of number 19’ Petite Morskoi, a main thoroughfare in the centre of St Petersburg, and ‘a stone’s throw from St. Isaac’s Cathedral’.22 He had established the premises in 1859, and a letter from his mother notes that by February 1860, in addition to her son’s studio, there were ‘about a dozen other new photographers begun’ on the Petite Morskoi ‘and on the Nevsky’.23

52 William Carrick’s Chimney Sweep, St Petersburg, 1860s, albumen print.

On 20 August Liddon writes that he and Carroll ‘dined at a restaurant on the Morskoi, and afterwards went about the streets and got our photographs’.24 Their diaries indicate that both men were regularly in the vicinity of Carrick’s studio in the Petite Morskoi. Moreover, Carrick not only sold his cartes from his premises but offered them for sale in the main thoroughfare of the Nevsky Prospect.25 Carrick’s ‘types’ may be located within the tradition of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1851–2) and John Thomson’s Street Life in London (1877),26 both initially published in serial form, but also, as Julie Lawson indicates, in the context of examples of ‘the “Cries” of St Petersburg . . . depicted in numerous illustrated books produced in Russia and in Western Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries’.27 Lawson is right to suggest the influence upon Carrick of ‘the tradition’ of works by J. B. Le Prince and John Atkinson illustrated respectively by engravings and coloured lithographs. As Elena Barkhatova points out, ‘lithographic “russeries”, as well as “turqueries” or “chinoiseries”, were popular commodities for tourists’.28 In addition, Carrick’s interest in creating Russian ‘types’ shared characteristics of contemporary mid-nineteenth-century photographers working in St Petersburg and Moscow, such as Alfred Lorens, Jean Monstein and H. Laurent.29 Each of these photographers produced versions of Russian peasant subjects taken from the street into the studio to display to the camera the visible signs of their occupation. In both conception and staging such photographs anticipate Carroll’s subsequent costume pieces using child models.

Many of Carrick’s photographs aim to distil the individual trades of itinerant peasants who regularly flocked to the city from outside to provide services or hawk commodities. Knife-grinders, glaziers and coopers appear alongside fishmongers, glove and stocking sellers. Among this group Carrick’s Chimney Sweep (illus. 52) (1860s) serves as a modified Western archetype for the émigré photographer. With his kneed trousers, turned-out feet and startled look, emphasized by the prominent whites of his eyes, the ‘Sweep’ resembles a contemporary caricature from Punch. His symbolic and literary associations identify him as part of an established Western visual economy of poor manual labourers. For Dickens such workers were a regular peril to visitors to London who should ‘be on their guard against’ a sweep’s dangerously protruding ‘brush’.30 In terms of photographic monochrome the principally black and (a little) white sweep provides a subject perfect for displaying those contrasts required by the medium, contrasts especially welcome in Russia where the dark winters and relative lack of good photographic light during much of the year meant technical struggle for photographers. This Russian ‘type’ of sweep, however, who carries the distinctively European ‘ball and brush’ tools of the trade, appears initially incongruous located in a sequence of more ethnographically displayed ‘types’. At the same time, though, the soot-blackened persona of the sweep, like that of his compatriot the shoeblack, is also a fundamentally racialized one. As English photographers of the period turned their cameras to figures of the urban poor whose dirty trades marked their bodies in racialized terms, ‘Russian’ photographers took up subjects whose ethnicity was apparently transformed by the dirt of a manual trade. In Russia, this practice achieves a different register by the use of the term ‘black people’, which according to Köhl explicitly linked dirt with race.31

Other photographs by Carrick stress the trade of their subjects by those commodities pictured. Thus, for example, An Abacus Seller (1860s; illus. 53) shows a boy posed centrally in the frame as if stepping out. His head turned to three-quarters profile, he displays his wares to, and gazes directly at, the camera. A large shallow basket hangs from tapes around his neck at an angle to best display the variety of abacuses contained within it. In addition, the boy shows off in each hand examples of the visually distinctive form of his commodity. Of varying sizes within the basket, the stiff wooden frames of the abacuses, patterned by regular rows of beads, provide considerable visual interest within a monochromatic scheme. Likewise does the peak of his cap, together with the folds of his leather knee-high boots, which catch the light against the neutral ground. Like many of Carrick’s subjects, the Abacus Seller is laden with those commodities he sells and visually distinguishable by them. His purposeful look, and movement arrested in mid-flow, is set off by the very simple background and the line where the floor meets the wall suggesting, albeit very subtly, an indoor shot.

Neither Chimney Sweep nor An Abacus Seller leaves uncertainty about the studio setting; very rarely does the photographer attempt to mask, or transform, the interior in these images from the 1860s. Prominent in such photographs circulating for the tourist trade are visual signatures of the pared-down, neutral studio setting. As a consequence, the placement of itinerant figures into the relative novelty of the photographic studio space grants to unlikely details a certain visual insistence. So, for example, some of Carrick’s shots register, in an otherwise unadorned studio, the seemingly inconsequential detail of a narrow but indelible skirting board that foregrounds decorative aspects of those costumes and commodities pictured.

53 William Carrick, An Abacus Seller, St Petersburg, 1860s, albumen print.

The familiar look of such Russian cartes anticipates the increasingly pared-down scene of Carroll’s costume photographs of the 1870s in which the same costumes and set-ups surface time and again. On his return home from Russia, Carroll becomes more insistent in his pursuit of costume photographs that, like Carrick’s, combine both ethnographic and theatrical elements. What is more, in leaving unadorned the studio space, those photographs Carroll began taking in the spring of 1872 in his Christ Church studio further resemble Carrick’s photographic ‘types’ of the 1860s. They do so in compositions in which a relatively barren space intrudes upon the fictional set-up in sometimes subtle, sometimes more overt, but nonetheless significant, ways. Moreover, even though none of Carroll’s extant prints, or recorded ‘sittings’, specify ‘Russian’ types, along with many specified nationalities, they incorporate generic shawls and scarves that suggest the multi-ethnic context that Carroll encountered in Russia.

54 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Beatrice Hatch, 16 June 1877, albumen print.

Beatrice Hatch (illus. 54), photographed in the studio on 16 June 1877, appears in costume that may be Russian. While Carroll does not identify her clothing, the headscarf and leather boots she wears are distinct from the costume worn by her sister, and designated as Turkish, in two photographs of Ethel Hatch in Turkish Dress, in both standing and seated versions, (illus. 55), taken on the same day. Moreover, both sisters resemble Carrick’s photographic subjects. Carroll also produced the seated version of Ethel in carte de visite format. In each photograph the child is positioned in a plain interior accentuating ethnic identity as evident in her clothing. In addition, the off-frame destination of each child’s look further suggests the photographic ‘type’ as an object of scrutiny. However, such photographs also recall other visual commodities Carroll purchased in Russia, most notably Orthodox icons. And while ancient icons are distinct from the modern forms of photographs, in their ontological status as images made by non-human agency – engaging the invisible as well as the visible – icons fundamentally anticipate them.32 Furthermore, for Carroll, as physical traces guaranteeing the magical presence of child subjects, photographs harbour the potential to incite devotion in a manner similar to icons.

55 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Ethel Hatch in Turkish Dress, 16 June 1877, albumen print.

In Russia, Carroll regularly combined the purchase of photographs with the purchase of icons. Liddon, too, recorded the purchase of photographs alongside icons and crosses.33 While the process of desire always exceeds its immediate object, in the Russian context, Carroll’s desire to buy photographs in the absence of being able to take them becomes entangled with an attraction to icons. Obliquely anticipating Carroll’s repetition of photographic subjects, nineteenth-century icon painters in Russia worked to patterns in the mass production of those Orthodox icons frequently sold alongside photographs. In the celebrated studios of icon painters individual workers engaged in piecework, each contributing a particular component of the composition. During his first days exploring St Petersburg, Carroll records his visit to the market principally in order to survey the ‘dozens’ of ‘little shops . . . devoted to the sale of Eikons’: ‘ranging from little rough paintings an inch or two in length, up to elaborate pictures a foot or more in length, where all but the faces and hands consisted of gold’. He promptly concludes ‘they will be no easy things to buy, as we are told shop-keepers in that quarter speak nothing but Russian’ (V, 291).

Typical of the replicas Carroll would have encountered, and one of the most commonly painted, was the Theotokos Kazan (Our Lady of Kazan; illus. 56), a holy icon of the highest stature within the Orthodox Church, brought to the new Kazan Cathedral in 1821 and considered the Holy Protector of St Petersburg.34 As Köhl points out, in St Petersburg the consumption of copies of sacred images is so ‘enormous’ and widespread that in the market ‘the little brass crosses, and the Virgins, the St Johns, the St Georges, and other amulets, may be seen piled up in boxes like gingerbread nuts at a fair’.35 Furthermore, purchasers routinely ‘buy a few scores at a time, as necessary to the fitting up of a new house, for in every room a few of these holy little articles must be nailed up against a wall.’36

Icons, like photographs, thus have the virtue of being both public and private objects. One may address one’s veneration to a saint in public while, since they occupy pride of place in Orthodox homes, one may also secretly devote emotion to an icon in private. Traditionally, icons were hung draped in the right-hand corner of the room ‘to be reverentially greeted by visitors’.37 But there were also many types of portable icons, including ones that folded, which merchants carried, for example, to be set up wherever they stayed on their travels. And in this quality of portability – to be treasured and opened for display when desired – icons anticipate one of the key virtues of the photograph as keepsake.

In Eastern Orthodoxy the icon is a manifestation of the divine, an imprint rather than a representation, and its status as a direct imprint emerges with the story of the Mandylion of Abgar, a piece of cloth bearing the miraculous image of Christ’s face imprinted upon it.38 Analogously, the photograph, as theorized in the nineteenth century, is miraculous in its physical trace of, and causal connection to, a referent. But as Geoffrey Batchen has demonstrated in the work of William Henry Fox Talbot, there occur vital questions concerning the nature of that ‘mode of inscription’ with which ‘nature reproduce[s] herself as a photographic image’.39

For Julia Kristeva, contrasting the Orthodox experience with the crisis of the modern European subject, the icon, which does not reveal all visibly to the eye, reflects ‘the exaltation of an ineffable religious inwardness’.40 In her discussion ‘Icon versus Image’, she particularly identifies the icon as ‘inscrib[ing being] rather than manifesting it’.41 Moreover, it is the icon’s status as ‘a graphein, a sensible trace, not a spectacle’42 that thereby, in Kristeva’s terms, distinguishes the ‘fixity’ of ‘the iconic – Byzantine economy’ of images from what she calls the greater ‘figurative flourishing of Catholicism’. Most crucially, as Kristeva understands it, an icon ‘is not limited to the gaze alone but engages our entire affectivity’.43

56 Theotokos Kazan (Our Lady of Kazan), 19th century, Orthodox icon, tempera on wood.

For Carroll, the Orthodox experience as he observes it in 1867, especially its engagement of the senses, enriches his own understanding of both religious and secular devotion. As early as his first visit to St Isaac’s Cathedral on 28 July, Carroll had been struck by the power, in situ, of the icons. ‘There are so few windows’, he writes, ‘it would be nearly dark inside, if it were not for the many Eikons that are hung round it with candles burning before them’ (V, 286). Icons in this way serve as lights literally illuminated by candles in the dark interiors of churches. Acknowledging as crucial to their meaning the conditions in which they were viewed, scholars have explored ‘vision’ in the context of icons in the Byzantine period as ‘more tolerant of uncertainty and obscurity’ than in the later Renaissance.44 They have shown how a vital element of the power of an Orthodox icon resided in its qualities of obscurity involved in the viewing experience itself. On visiting ‘the Cathedral Church in the fortress’ on 30 July, Carroll is again fascinated by the many icons ‘with candles burning in front of them’. On this occasion he sees ‘one poor woman go up to the picture of St Peter, with her sick baby in her arms’ and begin the process of ‘a long series of bowing and crossing herself’ as she addresses prayer to the saint. He is particularly struck both by the veneration with which she treats the icon and also by the visible weight of her conviction the saint will intercede on her behalf: ‘one could almost read in her worn, anxious face, that she believed what she was doing would in some way propitiate St Peter to help her child’ (V, 292).45

In a diary entry for 12 August regarding a visit to the Troitska Monastery, Carroll records having observed the work of boys who ‘are taught the two arts of painting and photography’:

In the painting-room we found so many exquisite Eikons, done some on wood, and some on mother-of-pearl, that the difficulty was to decide, not so much what to buy, as what to leave unbought. We ultimately left with three each, the limit being produced by shortness of time rather than any prudential considerations (V, 319).

The difficulty Carroll feels in having to leave some objects ‘unbought’ resembles the difficulty he finds in ‘leaving’ photographs. Newly confronted with such opportunities to buy Orthodox icons, Carroll is willing, as he is with photographs, to cast aside discretion. Even on a visit to ‘the Monastery of “New Jerusalem”’ on 15 August, after a monk has shown him and Liddon ‘all over the “Church of the Holy Sepulchre”, and out through the woods to see the “Hermitage” to which Nikon retreated during his voluntary banishment’, Carroll records:

On our way out, we bought at a sort of shop at the entrance, kept by the monks, small copies of the ‘Madonna of the three hands’ . . . painted to commemorate a vision of the Virgin Mary, seen in the way represented in the Icon, with a third hand and arm coming in from below (V, 328–9).

This is the only icon to which Carroll refers by name; perhaps he notes it because the ‘third hand’ is incongruous among the usual Virgins and St Peters.46 But he mentions it alongside reference to a curious optical toy, ‘an imitation ostrich-egg’: ‘On looking through it at the light, through a hole in one end, one saw a coloured representation, which looked almost solid, of a female kneeling before a cross’ (V, 328). This optical conceit, whereby a modern viewing mechanism of the popular peepshow discloses a sacred image, precisely dramatizes the implicit entanglement of ancient and modern, icon and photograph.

Not only did the material entanglement that characterized Carroll’s encounter with Russian culture influence his photographic practice, but it influenced his conceptual investment in the medium of photography. In their forms as treasured physical objects, souvenirs twinned with photographs, icons affected Carroll’s attachment to, and heightened his understanding of, the invisible power of the photographic medium.47 While the ancient painted form of an icon is distinct from the technological modernity of a photograph, nevertheless, on the Russian trip the two come together in curious ways as objects to which Carroll may address his fascination. Encountered in Russia, with their combination of touch and sight – their qualities of ‘traces’ and as ‘images’ – and thereby evading the distance of other forms of representation, icons and photographs both function for Carroll to guarantee a miraculous quality of presence that triggers memory, simultaneously evoking the anterior future tense.48 Carroll is therefore drawn to the very different material forms of photograph and icon both as imprints of extant ‘things’ and also as readily available commodities.

Carroll’s relation to the souvenir does not so much resemble what Susan Stewart describes as its capacity to signal ‘the nostalgia that all narrative reveals – the longing for its place of origin’,49 as it does ‘the romance of contraband’, in ‘its removal from its natural location’.50 At the same time, his intense wish to possess in portable form an indexical and easily reproducible portrait image represents a desire to experience ‘the icon’s oscillation between visible and invisible’.51 In Russia Carroll responds to the Orthodox icon as a spiritual imprint that allows the subject ‘an affective participation in divinity that remains outside of language’.52 While, for Kristeva, the icon animates cultural memory, for Carroll the ancient form of the icon confirms his investment in the modern function of the photograph to activate personal memory. More specifically, as Carroll witnesses the ardour with which Russians treat their icons, he identifies in a complex way with a version of that passion he himself feels towards treasured photographs. In the manner of copies, icons, like photographs, ‘enabl[e] individuals and communities to identify with a well-known image’ to which they might ‘attach their own stories’.53 For Carroll, the affective engagement elicited by an icon realizes and, by extension, legitimizes the type of engagement a photograph invites.

NIZHNI NOVGOROD: ‘A PEEP AT THE EAST’

NIZHNI NOVGOROD: ‘A PEEP AT THE EAST’

Icons and photographs were especially thrown into vivid relief for Carroll in the multi-ethnic context of the annual World’s Fair at Nizhni Novgorod that ‘brought together some twenty thousand merchants and one hundred thousand visitors from the four corners of the earth’.54 Following a three-day visit to Moscow, Carroll and Liddon set off for Nizhni on 6 August, and the former records the experience in detail, outlining especially the different ethnic types found there:

It was a wonderful place. Besides there being distinct quarters for the Persians, the Chinese, and others, we were constantly meeting strange beings, with unwholesome complexions and unheard-of costumes. The Persians, with their gentle intelligent faces, the long eyes set wide apart, the black hair, and yellow brown skin, crowned with a black woollen fez something like a grenadier, were about the most picturesque we met (V, 309).

The largest fair in Europe, as S. Frederick Starr points out, like other fairs in Russia ‘that dominated rural trade’, Nizhni Novgorod juxtaposed ‘peasant crafts and cheap western style goods to meet the traditional tastes of the local populace’.55 Its unprecedented mix of ethnicities and displays of commodities provided a context in which Carroll might not only situate the subjects of cartes de visite purchased in St Petersburg and Moscow but witness what he calls those ‘unheard-of costumes’, costumes he would subsequently contrive to reproduce in his photographic studio.56 In addition, the fair set modern photographs (such as Carrick’s peasant ‘types’) alongside ancient icons in a place that felt more Eastern than any other he and Liddon visited on the trip.

Carroll records spending ‘most of the afternoon [7 August] wandering through the fair, and buying Eikons etc.’ (V, 309) while Liddon captures the momentous effect upon himself of the Asian peoples and their customs when he notes in his diary: ‘I am delighted to have been at Nijni Novgorod. It is a peep at the East – the only one I have ever had in my life.’57 Liddon’s ‘peep at the East’ was, for Carroll, differently manifest in the form of dramatic spectacle. For on the evening of 7 August, while Liddon retired to bed, Carroll attended the Nizhni Theatre, ‘the plainest [theatre he] ever saw’. The play was Aladdin:

57 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Xie Kitchin as ‘Tea Merchant’ ‘On Duty’, 1873, albumen print.

The performance, being entirely in Russian, was a little beyond us, but by working away diligently at the play bill, with a pocket-dictionary, at all intervals, we got a tolerable idea of what it was all about. The first, and best, piece was Aladdin and his Wonderful Lamp, a burlesque that contained some really first-rate acting, and very fair singing and dancing. I have never seen actors who attended more thoroughly to the drama and the other actors, and looked less at the audience (V, 311).

Carroll was intrigued by seeing Aladdin in the context of Nizhni Novgorod for the tale, added by Antoine Gallard to the original collection of One Thousand and One Nights, is Middle Eastern, but its story set in China. John O’Keefe dramatized the tale for the Theatre Royal in Covent Garden in 1788, and Carroll saw various British productions of Aladdin.58 The experience of the play in the multi-ethnic context of the World’s Fair prompted him, late that same night and without any ink to hand, to write in pencil to his sister Louisa: ‘the whole place swarms with Greeks, Jews, Armenians, Persians, Chinamen etc., besides the native Russians.’59

The ethnic and religious groups encountered at Nizhni are precisely those Carroll created photographically on his return home in the miniature forms of dressed-up child models. His particular interest in Chinese subjects found expression in two of the first costume photographs he took in his Christ Church studio: Xie Kitchin as ‘Tea Merchant’ ‘On’ and ‘Off Duty’ (1873). In these images Carroll uses tea chests for props as he signals ethnicity through occupation as well as dress. The staging in ‘On Duty’ (illus. 57) corresponds with one of Carrick’s ‘types’ as the tea merchant poses with her commodity against an interior wall marked by a skirting board. ‘Off Duty’ (illus. 58), by comparison, with chests in disarray, pictures the child figure of the merchant in relaxed pose. Although the costumes are the same as those worn by Lorina and Alice Liddell twelve years before, the conception and staging of the photographs is markedly different. Xie Kitchin represents a ‘type’, not only as designated by her costume, but by the nature of her labour; to this end the tea chests form an important part of the composition.60 Gone is the generic chair of the ‘Chinese’ composition of 1860; in its place are ‘authentic’ props used in a manner reminiscent of those in Russian photographic cartes by Carrick and his contemporaries such as Laurent.

58 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Xie Kitchin as ‘Tea Merchant’ ‘Off Duty’, 1873, albumen print.

Following the Russian trip, Carroll took a number of other images using Chinese costume. In particular he made an extended visit (from 5 to 14 July 1875) to photograph at Oak Tree House, Hampstead, the home of the artist Henry Holiday, resulting in an album of 24 photographs presented to Holiday.61 On this occasion Carroll borrowed a Chinese costume from Heatherley’s Art School and the robe did the rounds of several models.62 A photograph of 10 July 1875 entitled A Chinese Bazaar (illus. 59) shows Daisy Whiteside taken at Oak Tree House. The daughter of William Whiteside, a merchant and farmer in India, the child appears in a frontal full-length portrait in the aforementioned Chinese dress against a plain backdrop. Her right hand rests on a vase displayed on a lacquerware box, while in her left she holds a fan. The commodity of tea is here replaced by Chinese porcelain and, in an attempt at a version of a pidgin English market cry he may have heard at Nizhni, Carroll’s inscription in his signature violet ink in the bottom, left of centre, reads: ‘Me givee you good piecey bargin’.

59 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), A Chinese Bazaar, 1875, albumen print.

60 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Rose Laurie as ‘the Heathen Chinee’, 1875, albumen print.

As in Xie Kitchin as Tea Merchant ‘On’ and ‘Off Duty’, props – here vase and lacquerware box – together with caption, clearly denote a mercantile context. Such contextualization according to a ‘type’ of occupation was not something Carroll had contrived before the Russian trip. Furthermore, on the same day Carroll photographed Daisy Whiteside, he took Rose Laurie as ‘the Heathen Chinee’ (illus. 60) in the same costume, sitting beside the same props with a quote from Bret Harte’s poem ‘Plain Language from Truthful James or the Heathen Chinee’.63 A token reference to cheating at gambling appears in the card the child holds in her left hand and the deck spilled in her lap.

Carroll’s photograph of Honor Brooke as ‘a Modern Greek’ (illus. 61), taken on 13 July 1875 on the same visit, stages those Greek subjects he had encountered alongside Chinese ones at Nizhni, but its oval format emphasizing the face of the sitter creates a different visual register. As the child subject sits cross-legged looking intensely at the camera, her body appears swathed in ethnic costume such that only her face, bare feet and hands are revealed. However, a closer look identifies the Chinese costume and fan from those shots of Whiteside and Laurie taken three days before. Transferring costumes in such a way from one child to another, from one ‘type’ or nationality to another, Carroll indicates not so much an ethnographic but a generic look. In addition, though, the format of the print, accentuating the girl’s look as requiring a return, resembles that of an icon.

Yet there is a different sense in which all three of these photographs from Carroll’s Holiday Album fix their child figures with a regularity characteristic of the icon. Moreover, in ‘A Modern Greek’ as in A Chinese Bazaar, an inscription forms an integral part of the image; a quotation in Greek reads (‘My life, I love you’) from Byron’s well-known ‘Maid of Athens’.64 In this image, the combination of the masquerading child with calligraphy – the photographic medium juxtaposed with the devotional nature of the text – recalls not only the visual effects of orthodox icons but their incorporation of inscription.

While it was common for Carroll to include such inscriptions in his albums of photographs, following his Russian visit, he increasingly supplements his photographs with inscriptions reminiscent of the presence of textual elements encountered in icons. Indeed, Carroll’s photographs of the 1870s recall examples both of Russian types and of Orthodox icons bought during the trip. By sleight of camera, the direct and earnest look in the eyes of a saint, with bare face and hands offset by elaborate but uniform compositional elements, translates into an analogously elaborate and repeatedly staged photographed figure of a child. Set against plain grounds, the faces and directions of the looks of Carroll’s costume ‘types’ seared into the photographic emulsion resemble the sacred figures of icons imprinted onto their gold grounds. As images not produced by hands, Carroll’s photographs of child-sized ‘China merchants’, Greeks, Turks and more generically represented nationalities convey qualities of presence comparable to those of icons.

61 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Honor Brooke as ‘a Modern Greek’, 1875, albumen print.

On 23 August, close to the end of his stay in Russia, having returned to St Petersburg via Moscow following his time at the fair at Nizhni Novgorod, Carroll made the following extended entry on the left-hand side of pages 15 and 16 in his journal:

In our wanderings, I noticed a beautiful photograph of a child, and bought a copy, small size, at the same time ordering a full length to be printed, as they had none unmounted. Afterwards, I called to ask the name of the original, and found that they had already printed the full length but were in great doubt about what to do, as they had asked the father of the child about it, and found he disapproved of the sale. Of course there was nothing to do but return the carte I had bought: at the same time I left a written statement that I had done so, expressing a hope that I might still be allowed to purchase it (V, 345).

This fifteen-line record, separated from the narrative run of his Russian diary as a whole, appears in a place normally reserved for items added at later dates. The note details a complex, and what would become an increasingly familiar, situation in the case of Carroll’s photographs of other people’s children, namely negotiation around an image. He sees a ‘beautiful photograph’ of an unknown child – in a sense for him the same as a photograph of ‘a beautiful child’, since medium and subject are in some ways commensurate – and he wishes to own copies of it. Carroll enters into conversation with the photographer regarding the logistics of ordering ‘a full length print’ because there are ‘none unmounted’ – the mount presumably making it more difficult to incorporate it into an album – but then returns to ask the name of ‘the original’.

On requesting the child’s name, Carroll encounters a hurdle: the studio ‘were in great doubt about what to do’ since, he confides, the photographer had consulted the father who ‘disapproved of the sale’. While in his regular diaries and letters comparable requests are fairly common – Carroll asks the permission of parents to take photographs of their children, or to gain a copy of a photograph, sometimes after having ‘seen’ them only once – there is a difference here. For Carroll deals with a Russian photographer over the image of a child, not only previously ‘unknown’ to him, but ‘unseen’ by him other than in the form of a likeness.

This incident details the circumstances of a photographic transaction in a way distinct from other entries in the Russian journal that simply record ‘shopping for’ photographs.65 Indeed, Carroll’s attempt to purchase this particular photograph stands in for the all-pervasive nature of his attachment to photographs of children. Significantly, just as on his visits in England Carroll desires to know the names of those children he meets, and in representations he uses the formulation ‘the original’ to refer to a child subject, in Russia the practice remains the same. At one level to want to know the sitter’s name is a gesture at making ‘respectable’ the wish to own the photograph; there is a sense in which an anonymous child is troubling to Carroll. At another, Carroll’s desire to put a name to the face represents the inverse of his request to his publisher Macmillan, two years later at the time of the German and French translations of Alice, to invite each child reader of all subsequent editions to put a face to a name by sending a photograph of herself. Macmillan promptly put a stop to that impulsive gesture by pointing out with considerable irony the prospect of a ‘Shower Bath filled a-top with bricks instead of water’ as equivalent to the unwieldy number of ‘cart-loads’ of ‘cartes’ Carroll would duly receive.66 Yet, in a sense, cart-loads of photographs are precisely what Carroll wants. There can never be too many and, as the Russian trip testifies, they need not be photographs he has taken himself. Such is the miraculous lure for him of the photographic image, in particular the image of a child.

It has proved impossible to determine the identity of the child in the St Petersburg photograph or the studio from which Carroll purchased it. Moreover, it is only possible to speculate how, at the mercy of his ‘vocabulary’, Carroll might have conducted what appears to have been a fairly elaborate transaction unless, of course, the photographer spoke English. Carroll may have come across the photograph in the window of the photographer’s or, as was more likely the case, singled it out from the albums of prints available to view inside; this was his common practice when visiting studios in London. However, regardless of how Carroll ‘noticed’ the image, his comment reveals the importance to him of securing prints.67

A subsequent note in his journal of 26 August provides a satisfactory resolution to the earlier uncertainty regarding the photograph: ‘the photographer called (“артистический фотография” at No. 4 Great Morskoi) to bring the pictures, as the father, Prince Golicen (?), had given them leave to sell them to me’ (V, 349) Critics have not translated the two words in Cyrillic that Carroll records in the entry for 26 August.68 At first glance they appear to indicate the name of the photographer but instead the transliteration: ‘Artisticheskaya Photographiya’ means ‘Artistic Photograph’ or ‘Artistic Photography’.69 Thus, Carroll’s note most likely preserves the name of the studio from which he bought the photographs (the sign advertising the premises at 4 Great Morskoi), or the name-stamp on the prints. While the inverted commas suggest a proper name, from his status as amateur Carroll may be ironically drawing attention to the ‘high’ art aspirations of the photographer. The title ‘Artistic Photography’ may equally refer to the types of ‘theatrical’ photographs that Carroll coveted in London thereby indicating the material difference of this particular establishment from the many regular carte de visite studios in St Petersburg. Whatever the case, this comparatively brief entry three days after the first would remain elliptical without the earlier gloss on the involved history of the transaction.

Carroll’s note of 23 August, retrospectively anticipating the arrival of the photographs on 26 August – in the nick of time since that day he and Liddon finally left St Petersburg for good – is thus distinctive, but its purpose is far from clear. In practical terms, the record of the photograph may operate to remind Carroll of the previously dependable role of humility in securing desired photographic sittings. Yet, while the reference resembles an addendum, an examination of the ink indicates it was most likely written at the same time as the rest of the entry. In purposefully separating it from the body of the text, therefore, Carroll makes the first entry bear the weight of the larger importance of photographs to memory in his experience of Russia. In this context, the note for 23 August resembles an aide-mémoire for Carroll recalling the aesthetic impact of the ‘beautiful photograph’ discovered on one of many shopping ventures in St Petersburg. But, essentially, read in sequence the first reference to the photograph anticipates, and the second commemorates, a momentous purchase.

Yet there exists no description of the ‘beauty’ of the photograph. Instead, rather like the elusive ‘Winter Garden photograph’ of Roland Barthes’s mother that Barthes claims not to reproduce because it would remain meaningless to anyone but himself, Carroll’s lost photograph gains power from its material absence, from its phantom status in the text.70 Furthermore, Carroll’s words that hold the photograph as allusion also powerfully trigger that which, like an icon, is beyond language. In so doing, they signal afresh the significance of the Russian visit to his investment in the photographic medium.

It is not surprising that the singled-out photograph of a child from 1867 is missing since the majority of photographs Carroll bought in his lifetime, along with many of those he took himself, were either lost or destroyed after his death. Yet since the circumstances of the purchase of this particular photograph would have remained unknown without the diary entry, this itself substitutes for all those unnamed photographs Carroll bought on the trip to Russia. Its very presence raises larger questions about Carroll’s desire for photographs in the Russian context, especially as they relate to the form of the icon. In a sense, a reader is required to imagine (for Carroll to remember) the lost photograph, but not in any simple visual conjuring of the image of a child subject. Rather, the record of the photograph functions in a manner analogous to the visually identifiable and familiar image of a saint in an icon. It guarantees a reassuring, because miraculously generated, sameness.71 For Carroll, the singled-out photograph alludes to a body of photographs of children he has by this time begun to amass, while at the same time pointing forward to those photographs he will more insistently create on his return.

It is in these terms, along with its assignment to an exclusive space on the verso of the entry for 22 August, that the diary entry indicates the lengths Carroll was prepared to go to secure photographic souvenirs. In turn, the unidentified photograph is a reminder that, in Russia in the 1860s, Carroll encountered photographs intricately bound with other commodities, most specifically portable copies of icons. Moreover, the connection between photographs and icons was essentially more than a material one. It was not simply because photographs were precious reproducible commodities to adorn private spaces that for Carroll they resembled Orthodox icons. Yet neither does the connection rest entirely with the fact that, like an icon-painter, a photographer is distinguished from an artist as ‘one who “reveals” (raskryvayet) an already extant image and the truths it embodies’.72 Fundamentally for Carroll, as sacred objects, icons elicit legitimate reverence in ways he would like photographs to do and, consequently, in Russia he buys icons, and wants to buy them, with an enthusiasm he usually reserves for photographs.

Understandably, witnessing devotion to an icon affected Carroll and Liddon differently. While Liddon was impelled to compare with his knowledge of the Catholic Church what he experienced in Russia, Carroll was in part affected by the passionate spirituality of the Orthodox faith because the devotion to icons he witnessed everywhere resonated with the power of a treasured photographic portrait. But, of course, icons are problematic when they become idols, and iconoclasm perpetually concerns Liddon as he tries to understand the Eastern Church in relation to the Roman. Indeed, so impressed is Liddon by the ‘Great Celebrations in St Isaac’s Cathedral’ that he thus writes to the Reverend William Bright, Professor of Ecclesiastical History at Oxford: ‘of course, the ritual was elaborately complex – bewildering – indeed, to an English mind. But there was an aroma of the fourth century about the whole which was quite marvellous.’73 Liddon is especially struck by ‘the troops of infants in arms [who] were brought by their mothers and soldier fathers to kiss the Icons’ and, in identifying the exuberance of the people’s devotion to the Eastern Church, Liddon claims:

to the outward eye she is at least as imposing as the Roman. To call her a petrification here in Russia would be a simple folly. That on the other hand she reinforces Rome in the Cultus of the Blessed Virgin Mary and other matters, is too plain to be disputed.74

Yet, Carroll, on the other hand, is attracted to what he calls the ‘gorgeous services’ precisely for ‘their many appeals to the senses’, although he reacts negatively to some aspects of Orthodox ritual, claiming on one occasion it makes him ‘love’ the ‘plain, but to [his] mind far more real service of the English Church’ (V, 288).

62 Lewis Carroll (C. L. Dodgson), Xie Kitchin as ‘Dane’, albumen print, 1873.

Carroll is simultaneously fascinated by the icon as venerated object and as modern commodity to be carried off in a suitcase. Indeed, along with various unspecified photographs, he leaves Russia with ‘a beautiful photograph of a child’ and a range of Orthodox icons. But popular cartes de visite and popular Orthodox icons conceptually intervolved throughout the trip did not subsequently become entirely discrete entities for Carroll. Rather, on his return, he rehearsed the conceptual entanglement and complex congruence of the two indexical forms of representation in his developing preference for photographing a female child in a bare interior, her face emphasized against elaborate costume. In addition to those ‘costume’ photographs already considered, such correspondence is most apparent in Xie Kitchin as ‘Dane’ (1873; illus. 62) in which Carroll’s favourite child model returns the gaze of the viewer in a way suggestive of the intensity and direct visual contact of an icon while approximating, in direct frontal pose, one of Carrick’s ‘types’. This photograph was a personal favourite of his, and Carroll reprinted it many times, even having special coloured enamelled versions made to give as gifts.75 Indeed, part of the attraction of this photograph for Carroll resided in its design for show in a domestic setting; the pleasure it afforded him to distribute the portable treasured image to friends to display in their homes in the manner of an icon.

Throughout his visit to Russia, Carroll thereby connected the affective power upon Russian subjects of their icons with what he had come to recognize as his own intense investment in particular photographs. While an Orthodox Russian’s relationship to the ‘mystery’ of Mary was very different from his own participation in the effective ‘mystery’ of a photographic subject, nonetheless the photograph of a female child seemed to ensure for Carroll a version of what according to Kristeva the ‘mystery of Mary’ offered a ‘believer’, that is, ‘an almost infinite sensory freedom’.76 Moreover, in Russia Carroll’s experience of reverence to the spiritual imprint of an icon offered him a precedent for, and in a certain sense sanctioned, his increasingly insistent engagement with photographs. Perpetually troubled during the 1860s by being at odds with his father’s beliefs, and regularly recording in his diaries extreme guilt in neglecting his clerical and academic duties for the pleasures of photography and the theatre,77 Carroll reacted to the spiritual devotion to icons in part because it allowed him to understand afresh – and to some extent legitimize – the compelling nature of a photograph as an imprint and not simply a representation.

Many Orthodox icons increase in power according to their slow erasure by kisses of the devout. They are carefully preserved. There exist unwritten laws against their destruction. But just as icons are ‘embraced’ and ‘kiss[ed] with the eyes’ to be ‘taken into the memory’,78 photographs bring together vision and touch to nourish memory. Carroll treasures photographs because, as emanations of their referents, they afford a corresponding synaesthetic response. Acknowledging as approximate to rapture the response he feels in the presence of the image, Carroll would like to kiss a photograph as an Orthodox Russian kisses an icon. Indeed, increasingly after 1867, the photograph of a child incites Carroll to embrace with his eyes, and take in with his memory, a sensible trace of presence. St Petersburg, with its readily available cartes and equally plentiful icons ‘piled up like gingerbread nuts at a fair’, newly and distinctively endorses Carroll’s fascination with the indexical power of photography.