ISÈRE

The capital of Isère is Grenoble, the largest city within the French Alps, known for its universities, technology companies and its location, surrounded by mountains, an ideal base for lovers of winter and summer Alpine sports. In France people might also associate the surrounding countryside with walnuts, but few associate Grenoble with wine.

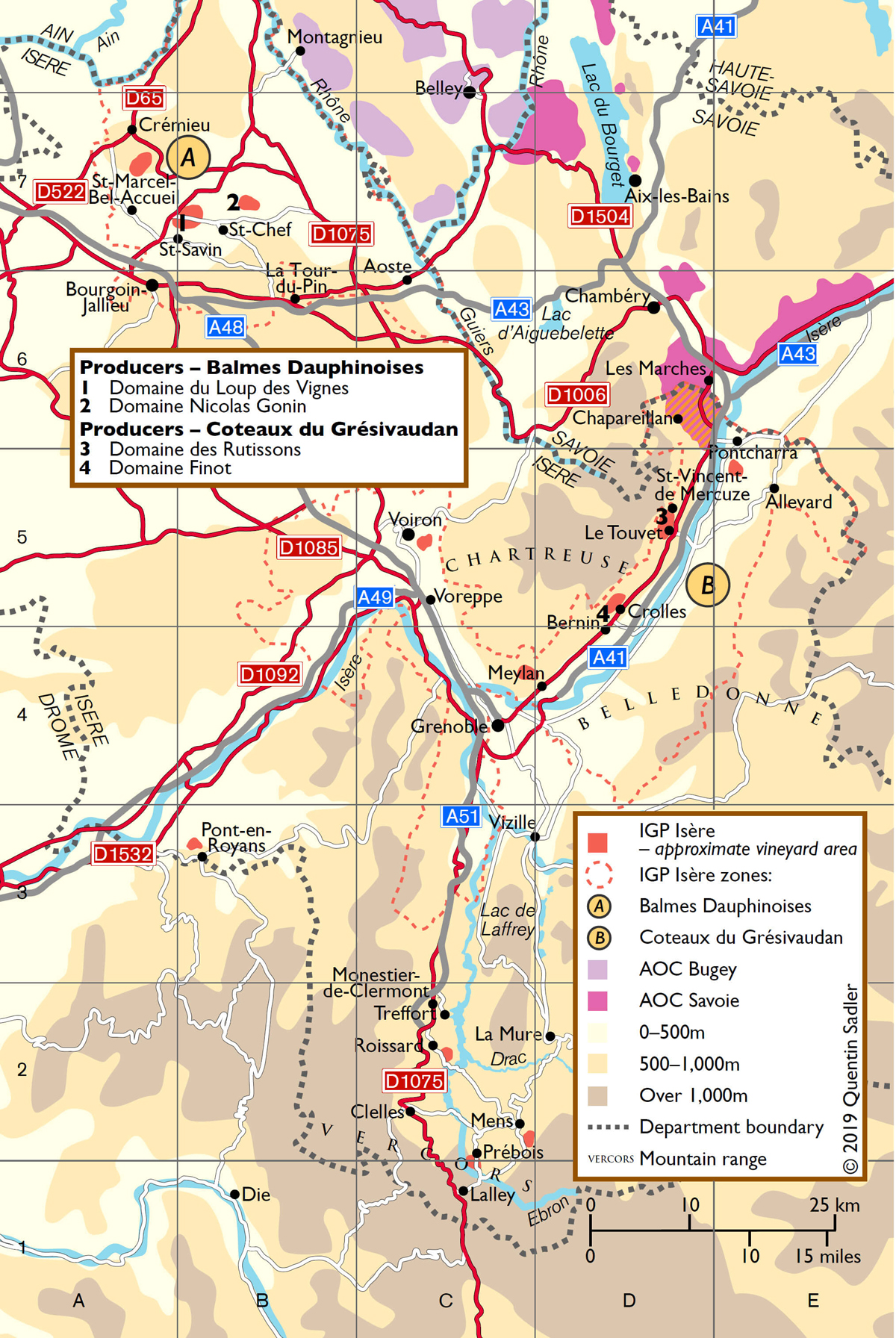

Isère’s most famous vineyards are to the west in the northern Rhône Valley, just south of the Roman city of Vienne – wines such as Côte Rôtie and Hermitage (both Syrah), Condrieu (Viognier), and the nearby IGP Collines Rhodaniennes, none within the scope of this book. In the far east of the department are the vineyards in the village of Chapareillan, below Mont Granier – these are included in the AOC Savoie, and produce the delicate white Jacquère wines of Abymes. In between these areas, and extending south of Grenoble, there are numerous hillsides that were once planted with vines. In the mid-19th century Isère had 30,000ha of vines, more than Savoie and Haute-Savoie combined, but between the catastrophe of phylloxera and the industrialization of the region, the vineyards declined dramatically, mostly planted with inferior hybrid varieties grown for local consumption.

The IGP Isère includes two specific zones, Balmes Dauphinoises and Coteaux du Grésivaudan, which are described in this chapter, along with selected producers. In the southeast of Isère is the Trièves, a high-altitude plateau, which at its pre-phylloxera peak had 300ha of vineyards and is now undergoing an exciting, albeit tiny, revival.

Also worth noting is a new vigneron, Antoine Dépierre, who has revived a small vineyard at his family home on the western foothills of the Vercors, near Pont-en-Royans. Antoine worked for a decade as a sommelier and hotelier internationally and manages his vineyards at Domaine Mayoussier along organic lines, ploughing with a horse – he organizes an annual wine fair, Le Salon du Vin à Cheval, inviting vignerons working with horses from all over France. And even the city of Grenoble itself now has a vineyard: the historic restaurant Chez Le Pèr’Gras, on the city’s Bastille hill, planted 1ha of Chardonnay and Verdesse vines in 2017 on a hillside where until the 1970s there were 5ha of vineyards providing wine for the restaurant. The vines are farmed organically.

The revival of these vineyards is promising, but it is very much in its infancy with at most 60ha in commercial production at the time of writing. Nearly all of the producers behind this revival are interested in preserving the heritage of the area as a once-great wine region by focusing on its rare grapes, and most farm organically too.

Coteaux du Grésivaudan

Having flowed down the Combe de Savoie, the Isère cruises on towards Grenoble, dividing the Chartreuse Prealpine mountain range and the higher Belledonne Alps. The departmental boundary between Savoie and Isère falls in the vineyards of Abymes and technically the Grésivaudan valley begins there. The area between Pontcharra and Grenoble has always been the most planted area of the Grésivaudan, but when the IGP geographical limits were set the zone was also extended south and west of Grenoble on the northern and eastern foothills of the Vercors, where there are small vineyard areas.

Once a region much respected for its wine quality, over the past century vine plantings have declined to next to nothing for a multitude of reasons. Indeed, in 2018, the last wine co-operative of the valley (once there were seven), in Bernin, stopped making wine; local vigneron Thomas Finot takes the grapes from the 3ha still owned by co-operative members to make wines for his négociant label. While Thomas Finot and Domaine des Rutissons, both profiled here, battle to keep this valley alive with vines and wines, the biggest problem is the pressure from real estate, tempting landowners to sell their old family vineyards to house-builders. The value of constructible land can be more than 60 times the value of vineyard land (up to 5€/m2 for the latter, compared to 300€/m2 and more for constructible land).

There were originally many plantings on the more humid eastern side of the Isère river, especially around Allevard, but today the sole commercial vineyards are a couple of hectares owned by Domaine Chevalier Bayard near Pontcharra. On the Chartreuse foothills there are scattered plantings south from Chapareillan to the northern suburbs of Grenoble, but the densest area of plantings is in the area of the Manival stream, between St-Ismier and Bernin, on an alluvial cone, whose soil is more propitious for vines than for building. With vineyard altitudes varying from 300m to a little over 500m, this is a very hot and sunny area in summer, but the cold air comes down from the peaks at night, creating a favourable diurnal difference. The soils are mainly classic stony clay-limestone scree and extremely well drained, which helps combat the very high rainfall in this area, higher than in the Combe de Savoie, for example.

An old vineyard of Domaine des Rutissons above St-Vincent-de-Mercuze, with Le Grand Manti in the Chartreuse mountains behind.

As well as the two profiles below, mention must be made of Michael Ferguson of Le Mas du Bruchet in Meylan. A South African, working in technology in Grenoble, he was a pioneer in growing, making and bottling Verdesse in his 1ha vineyard at his house (also a bed and breakfast), planted in 1998. He has been making several thousand quality bottles, vinified in oak, Burgundy style, since 2003. Another pioneer is Sébastien Bénard, who has planted a small vineyard near Voiron. He makes natural wines from a range of local and rehabilitated grape varieties, mostly labelled as Vin de France.

Domaine Finot

Since establishing his estate in 2007 the laid-back vigneron Thomas Finot has experienced somewhat of a moving feast with his production levels and wine range. Some years have presented climate challenges, especially affecting his young vines, and he keeps losing older vineyard parcels he has leased as the owners decide to sell their plots to property developers.

Thomas’ winery is located on a small industrial estate north of Grenoble in a garage-type building, a former microbrewery and previously a car repair business. It’s a wine hipster’s dream, but you might wonder why it appealed to him once you know that he was brought up in the vineyards of Crozes-Hermitage. As always, to understand a vigneron, you need to visit his vineyards. Drive just five minutes up the hill towards the jagged limestone cliff of the Dent de Crolles and you find yourself in wild parkland, full of hikers enjoying the dramatic views across to the Belledonne mountains. Interspersed among the forest are Thomas’ vineyard plots, some with very old vines, others newly planted and scattered across several nearby villages.

Audrey and Thomas Finot with the Belledonne mountains beyond.

When young, Thomas stayed close to home, studying wine first in Belleville, Beaujolais, and then in Vienne, while working in Crozes-Hermitage (today he has taken on the small plot of family vines, with assistance from an employee, and makes Crozes wines under the Domaine Finot name). But after his studies he worked in Corsica and later Switzerland. He loves exploring the mountains and it was on his regular drive back home from Switzerland that he discovered the Grésivaudan vineyards. He moved to Savoie and worked for a while with Michel Grisard in Fréterive and at Domaine des Ardoisières; he learned about organic and biodynamic viticulture, along with rare grapes, and decided to do his own thing, if only he could find vines in the Grésivaudan.

His early vineyards included Pinot Noir and Pinot Gris, but 2018 marked the last vintage as these are some of the vineyards he’s lost. He retains Chardonnay and Viognier along with some old vines of local varieties, and he started planting Verdesse, Altesse, Persan and Etraire from 2010. Thomas’ most exciting white variety is Verdesse, of which he has 1.7ha (including 0.3ha of old vines). For reds there is still some Gamay, 0.8ha of Etraire de la Dui (spelled Dhuy by him and including 0.25ha that is nearly 60 years old); and 1.2ha of Persan, including 0.35ha planted in 1994 by Daniel Zegna, a well-known local grower who worked to preserve the old varieties. In 2015 Thomas planted the very rare red Serénèze de Voreppe variety, rehabilitated by the CAAPG; once it has been classified with a new name, he hopes to plant the local white Ste-Marie-de-Biviers. He is certainly a fan of these old varieties, but is a realist too, and feels that international varieties provide an important visiting card, proving Isère is capable of making good wines.

Thomas converted all his vineyards to organics and became certified in 2014. He ploughs every other row and lets the natural vegetation grow in between; he uses plant preparations such as nettles and horsetail, alongside organic treatments. In his – frankly funky – cellar, Thomas has metal and plastic tanks, alongside barrels of a mixture of ages, bought second-hand from, among others, Philippe Bouzereau of Château de Cîteaux in Burgundy. He works in the cellar by instinct and tasting, though he is given an outside viewpoint at least once a year by his elder brother, Matthieu, who since 2003 has lived in Virginia, US, working as winemaker for King Family Vineyards. There are no recipes here, even though for reds he prefers punch-downs to pump-overs, each wine is treated differently: some reds are whole bunch, some are part destemmed; some whites have malolactic, some don’t; there are different oak uses and a skin-fermented Jacquère in the making. For Thomas, indigenous yeasts are essential, and he likes to keep low final sulphur levels.

Matthieu is an off-site partner in Finot Frères, the négociant side of the business. From partly bought-in grapes, not always organic, the Tractor range is blended to reflect the area, with some grapes from nearby Savoie, Ain or Collines Rhodaniennes. Tractor Blanc is usually made from Jacquère and Chardonnay, sometimes with Pinot Gris; Tractor Rouge is usually Gamay, Pinot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. Tractor Rosé is Gamay. They are well-priced, simple, joyous wines for drinking young and with 15–20,000 bottles a year account for nearly half the volume of wine Thomas sells; this is likely to increase from 2018 with the extra fruit from the old Bernin co-operative growers.

The key wines under the domaine name are Verdesse, Persan and Etraire de la Dhuy. The Pinot Noir was consistently delicious, and Thomas makes his Etraire in a similar style, never chaptalizing, and one could say it’s a more Alpine and tannic version of Pinot, very much reflecting the vintage too. His Persan is more serious stuff for ageing, made more like his Crozes-Hermitage wines. Up to 2017 Thomas’ Verdesse has been bottled in 50cl as a late-harvest, off-dry style – showing characteristic grapefruit notes, along with a honeyed richness and stony character. With a greater quantity in 2018, a dry version is in the making, with nearly 15% alcohol; it is a splendid grape, and if anyone can tame it, and other rustic Isère varieties too, Thomas can. He works with a good team – Christian, his assistant, has worked with him since 2012, and Audrey, his wife, also teaches about wine and is the perfect leveller for Thomas’ ideas. At present exports stand at about 20% and they don’t look to increase this, preferring to sell to the pinnacle of restaurants and wine shops around France.

Domaine Finot

190 Impasse du Teura, 38190 Bernin

Tel: 06 84 95 21 44

Email: finot.thomas@gmail.com

Map ref: D5

Vineyards: 5.5ha

Certification: Ecocert

Visits: Preferably by appointment

Domaine des Rutissons

Laurent Fondimare is from Normandy, has no wine training and no family background in agriculture, but that was what he chose to study in Bordeaux, making many friends who later became vignerons. Moving to Isère he took up a career in agricultural real estate, something he still works in full time, but he harboured a dream of producing something from the land. In 2010 Laurent seized the opportunity to lease a hectare of old vineyards from Michel Bozonat, the grandfather of a friend of his children. In his eighties, Bozonat, a legendary vigneron in St-Vincent-de-Mercuze, was still farming cows, corn, walnut trees and some vines; a member of the now-defunct Le Touvet wine co-operative, he made his own wine too. He was of great help to Laurent in making his first wines. After five years building up his tiny wine estate, Laurent was joined by local friend, Wilfrid Debroize, a builder who was seeking a career change and was prepared to work full-time on the estate.

The project had begun as a real community venture: local residents assisted Laurent and later Wilfrid in every major step, from planting the vines to harvesting the grapes – today they still enjoy helping with harvest. In 2015, the pair received support from a local association, who found them a decent building to create a winery suitable for their growing production and it remains owned by the community. Thomas Finot and several Savoie vignerons, such as the Giachinos (who passed on a plot of Gamay they no longer wanted to farm), also helped them. Over the years Laurent and Wilfrid have planted several small plots with varieties historic to their area, grapes which fascinate them – Verdesse, Etraire de la Dui (spelled Dhui by them) and, more recently, Persan.

Having converted the vineyards to organics, the pair’s attitude is to limit the risks of crop failure; biodynamics interests them, but they realize this may be a step too far at the moment. In the rustic winery they do everything themselves, sometimes with borrowed equipment. The winemaking uses indigenous yeasts and low sulphur additions. Oeno Conseil do the analysis, but they bottle their own wines.

Laurent Fondimare and Wilfrid Debroize, the beasts of Domaine des Rutissons, pose in front of their ‘La Bête’ cuvée.

Five wines are produced regularly: two whites – M. Leblanc (a light fresh Alpine wine from Jacquère with up to 20% Viognier) and a pure, very grapefruity Verdesse; and three reds – Mes P’tits Gars, an early-bottled juicy Gamay, La Bête, a rustic mountain beast made from a field blend from the old vineyards (the blend includes Mondeuse, Persan, Peloursin, Gamay, Etraire de la Dui, Alicante and the odd hybrid), aged in old oak, and a pure Etraire de la Dui, aged for up to a year in three-year-old barrels and representing this variety well. The whites are joined in some years by a cuvée named Les Ailés from late-harvested Viognier with around 20% Verdesse. As Verdesse represents almost half their plantings, in future they plan to make several different cuvées, possibly including a sparkling and a Burgundian-style oak-fermented wine – they note how flexible this grape is with its excellent levels of both sugar and acidity. The latest red wine release is Lettre R, first made in 2015 from 85% Etraire with 15% Verdesse, in a homage to Côte Rôtie (where Syrah may be blended with a little Viognier) – it is a little over-oaked to my taste but may well calm down. From the 2018 vintage they will make their first Persan.

Although they sell a little further afield, Laurent and Wilfrid would like nothing better than to convince the locals that their Grésivaudan wines are worth buying and drinking – to that end they participate as much as possible in local wine and gourmet fairs.

Domaine des Rutissons

3 Grand Rue, 38660 Le Touvet

Tel: Laurent Fondimare 06 64 86 33 20; Wilfrid Debroize 06 63 84 51 23

Email: contact@domainedesrutissons.fr

Map ref: D5

Vineyards: 5.5ha

Certification: Alpes Contrôles

Visits: Preferably by appointment

Balmes Dauphinoises

Known to most people simply as northern Isère, Balmes Dauphinoises translates as the ‘little valleys of the Dauphinois’. The area lies north of the towns of Bourgoin-Jallieu and La Tour-du-Pin between Chambéry and Lyon. Lyon was a major market for sales of Balmes Dauphinoises wines in the 19th century, as was Bourgoin, once an important silk- and textile-manufacturing town – Hermès has a factory there today. In the mid-19th century, St-Chef (a town also known for its tenth-century church and Roman-Byzantine frescoes) had about 1,000ha of vineyards and even in the 1940s there were 150ha, growing in particular Altesse, with very few hybrids.

Between the Alps and the southern end of the Jura mountains, this area is effectively a prolongation of Bugey: Montagnieu is located just to the north. Its soils are similar, of glacial origin with clay-limestone and a mixture of sandy loam, gravels and molasse on a series of mainly south-facing hillsides with vineyards at a relatively low altitude of 250–350m. Slightly northwest of the hills is a plateau area known as Isle-Crémieu, on limestone from various periods, most suited to white grapes – Nicolas Gonin has planted a small vineyard in this virtually abandoned area. The climate in Balmes Dauphinoises is continental, with cold winters and very hot days in summer, similar to the northern Rhône Valley (Côte Rôtie is only 50km away as the crow flies). However, the proximity of the Alps leads to very cool nights in summer and high rainfall, and it is even windier than Savoie or Bugey. Grapes here ripen earlier than other Isère vineyards.

There is no wine co-operative and just a handful of growers: the two most prominent and interesting are profiled below. A couple of other, longer-established vineyards sell locally, with a focus on sparkling wines.

Domaine Nicolas Gonin

When it comes to grape varieties Nicolas Gonin has a mantra, which is that everyone should grow ‘only grapes that are traditional to their region’ and the rarer they are the better. After his oenology degree in Dijon Nicolas wanted to establish his own estate near his family home but initially could not find enough vineyard parcels or suitable land. So he worked for wine estates including Château Gillette in Sauternes, Domaine Tempier in Bandol and California’s Ridge Vineyards and during this time discovered various old books on grape varieties, catching the rare grape bug in a big way. In his spare time, he learned about ampelography and the identification of grape varieties from two of the world’s top ampelographers – Thierry Lacombe and Jean-Michel Boursiquot – based at INRA (the French agricultural research centre).

Today, Nicolas’ studies into rare grapes, especially those once planted in the vineyards of Isère, are almost all-consuming. He is a vice-president of the CAAPG and spends every spare moment ferreting in back gardens to discover rare vines that might help preserve vine biodiversity. And he loves to travel the world spreading the word about Isère’s wines and its rare grapes.

Nicolas’ father Maurice, whose family has lived in Isère for over 500 years, farmed tobacco and vines; his uncle, Gaston Gonin, farmed 1ha of vines and Nicolas was able to take these over when he established his estate in 2005, at the same time taking on another 20-odd disparate parcels of bare land or vineyards, which he has replanted. Although originally he made Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Gamay and Pinot Noir, the last were grubbed up in 2015 as Nicolas wants to retain or plant only rare or traditional varieties. For whites he has Altesse, Verdesse, Jacquère and Viognier – the latter planted because there were so few local whites and he found evidence of it being grown traditionally, but he confesses that here it is at its northern limits; the reds are Mondeuse and Persan, plus 0.3ha of the ultra-rare Mècle de Bourgoin, a local variety which he helped rehabilitate and which resists drought well, hence thought of as ideal for the future. The first tiny production was in 2018. Mècle is the first really rare grape he has worked with personally and he hopes to plant Bia Blanc and Servanin soon.

Nicolas Gonin’s vineyards above St-Chef.

Most of Nicolas’ vineyards are in St-Chef, with the principal one being a steep, south-facing gravelly slope, Coteau de Trieux, which he has replanted with Altesse and Mècle. In the more calcareous soil of the Isle-Crémieu at St-Marcel-Bel-Accueil he has planted Verdesse and some Jacquère at very high density. Allowing the natural grass to grow throughout the vineyards and simply cutting and strimming, converting to organic farming was a priority for Nicolas and the estate was certified from 2012. Although he uses some plant preparations, his scientific mind makes him sceptical of biodynamics. In the vineyards his father gives him a hand, along with some seasonal workers.

Nicolas built a winery in 2005, installing simple equipment, mainly a series of old metal and fibreglass tanks; he has no interest in using oak barrels, saying they are against his religion and his banker is against them too. He is open to advice and in 2017 took on an oenologist from the Rhône Valley to provide extra feedback on his wines. Nicolas himself enjoys what he calls ‘wines of the north’ and this means he looks for acidity, so he often picks on the early side, especially as he likes to encourage malolactic fermentation. He says that the fact that his vineyards are grassed down gives better pH levels as well as a long finish to the wines.

Nicolas Gonin with his metal wine tanks.

In a decent year, Nicolas makes around 20,000 bottles, of which normally just under a third is his white blend, which changes over the years according to what grapes he has. The 2016 is 60% Viognier with 40% Altesse, and in 2017 the wine wasn’t made as all the Viognier was destroyed by frost. From two different vineyards, his pure Altesse can be very precise and elegant; the characterful Verdesse is very vintage-dependent in flavour, varying from the citrus character of a Jura Savagnin ouillé (and yes, it is likely to be related) to in warmer years a plum eau-de-vie character, but the key is the grape’s high natural acidity. Nicolas makes a delicious rosé from 100% Mondeuse, and a very light unchaptalized red Mondeuse. Despite the light alcohol – often below 10% – it has weight of flavour, showing the grape’s spice and red fruit flavours in equal measures. The deep-coloured Persan is prone to reduction so needs air to open it up, but it is Nicolas’ real pride and he exports it widely, believing it to have the most potential for the future. Overall, Nicolas sells half in Lyon, Grenoble, Annecy and other local markets, 40% to export markets, mainly the US, but also Canada, Japan, Norway and Switzerland, and the rest to top restaurants elsewhere in France.

Nicolas is a man on a mission and can alienate others – so much of his time is spent in bureaucratic fights to prove a rare vine’s heritage and rehabilitate it that he can be over-protective – I have worried that his own estate might suffer too. But for now, Nicolas’ wines are deservedly the most visible around the world and France too, waving the flag for Isère.

Domaine Nicolas Gonin

945 Route des Vignes, 38890 St-Chef

Tel: 04 74 18 74 81/06 10 39 25 15

Email: nicogonin@wanadoo.fr

Map ref: B7

Vineyards: 5.5ha

Certification: Ecocert

Visits: Tasting room, by appointment

Domaine du Loup des Vignes

Bubbly Stéphanie Loup (loup is the word for ‘wolf’ in French) grew up in St-Savin and studied wine at Belleville in the Beaujolais. She went on to work for Domaine de Méjane in Savoie, where she met her partner Mario Amaro Rabiço, a Portuguese who had emigrated to Savoie in 1998. In 2003, the couple took over an existing wine estate in her home village, with 6.5ha of vineyards. On a single steep slope, named Coteaux de la Rémonde, it rises from 260m up to about 350m, with a slope of 50% in places. Originally planted in the 1970s, today about two-thirds of plantings are Chardonnay with various other grapes – whites on the clay-limestone; reds (with a predominance of Pinot Noir) on the gravel. The large, rambling farmhouse where they live just below the vineyard slope has plenty of space not only for their young family but also for the winery and a tasting room. Today they make 30–40,000 bottles, sold almost exclusively direct to local consumers buying at the cellar and at local wine shows.

In the vineyards, they work manually and with a tracked vehicle, letting the grass grow between the rows and using herbicide underneath the vines once or twice a year; they limit treatments as much as possible. Winemaking is simple, using native yeasts and rarely chaptalizing except occasionally for Mondeuse and Syrah. Two versions of Chardonnay are made at different sugar levels: even the so-called dry version has some noticeable residual sugar, which appeals to their clients. There is another intriguing, exotic, off-dry, rich white, A Pas de Loup (meaning ‘at wolf’s pace’), which is usually a blend of late-picked Velteliner Rouge Précoce (Malvoisie) and Viognier (a variety that Stéphanie likes and has planted more recently). The varieties are harvested together at a slightly raisined stage, giving a white that provides a powerful reflection of their warm vineyard site and is the most interesting wine from the domaine.

Stéphanie makes Pinot Noir by crushing but not destemming the grapes and giving around a week’s maceration with pump-overs. The result reveals decent fruit character, if a touch hard. Also spoilt a little by hard tannins is La Meute (an old name for wolf), a Mondeuse/Syrah blend, which shows a lovely mineral character to the fruit. A medium rosé and a range of sparkling wines are also made.

All Domaine du Loup des Vignes’ vines lie on the Coteaux de la Rémonde in St-Savin.

Stéphanie and Mario are doing a wonderful job in keeping alive an important vineyard hillside of the Balmes Dauphinoise and Stéphanie is an excellent ambassador for Isère wines. I get the sense that if they chose to make a leap forward in various aspects of both farming the vines and making the wines they could have a much greater wine quality, warranting higher prices and wider markets.

Domaine du Loup des Vignes

10 Chemin de la Rémonde, 38300 St-Savin

Tel: 04 74 28 95 82/06 03 40 25 97

Email: loupdesvignes@sfr.fr

Web: domaineduloupdesvignes.com

Map ref: B7

Contact: Stéphanie Loup

Vineyards: 7.5ha

Visits: Tasting room open daily except Wednesdays and Sundays

Trièves

If there is one area in this book that has tried hard to steal my heart, it is the Trièves. Located southeast of Grenoble near the borders of the Drôme and Hautes-Alpes departments, this remote, high-altitude, sparsely populated plateau lies between the Vercors and the Dévoluy Prealpine ranges at an altitude between 700m and 800m. Unlike the other Isère wine areas, the Trièves lies just into the southern Alps, with a hint of Provençal air. With no big towns or industry nearby, it is a haven for environmentalists and mountain lovers.

Samuel Delus in his young Onchette vineyard.

The story of the revival of the Trièves vineyards tells of the dogged determination of a group of individuals to bring their vineyard area back to life and in doing so create a sustainable living for others. They also wanted to save an emblematic grape variety, Onchette, which was on the brink of extinction. In the middle of the 19th century there were about 300ha of vineyards in the Trièves – all the locals grew vines for family use – but by 2007 there were just 8ha owned by 50 people, mainly growing hybrids. Today there are new plantings by five vignerons of about 12ha of Vitis vinifera destined for commercial production and since 2015 a few hundred bottles of wines have been released. An association of local individuals and businesses, presided over for many years by Gilles Barbe, is largely responsible for this success.

However, the first would-be pioneer was Samuel Delus, now president of the association. In around 2000 Samuel decided to give up his audio-visual technology career in Paris to return with Naomi, his English wife, to Prébois, where he still had family and had indeed met Naomi, who had been working at the local ecology centre, Terre Vivante. His plan was to establish a wine estate in Prébois, and due to the paucity of good vineyards available to buy, he needed to plant, for which you need permission and a track record. Samuel retrained in wine, worked at an uncle’s vineyard in Provence, and sought advice in nearby Savoie, but despite repeated requests the authorities blocked him from planting due to restrictions on planting rights in France, especially outside AOC areas.

At first unbeknown to Samuel, just down the road in Mens, an enthusiast of the local agricultural heritage, Gilles Barbe, a hydroelectric engineer by profession, was galvanizing the locals, with whom in 2008 he formed the association Vignes et Vignerons du Trièves. Their idea was to work together to preserve what vineyards still remained, make the wines communally, create a conservatory of old vines and eventually create employment too. Preservation of the local environment and its biodiversity was important to them, and one inspiration was the French author Jean Giono (1895–1970), who had a mountain home in the Trièves and had often written about the local wine’s impact on the rhythm of life here. Samuel was able to work for the association, planting new vineyards from 2010 (the association could obtain permission to plant experimentally, on the basis that the wine is not sold for profit). He was also able to help them set up and make wine in a communal winery the association established in Prébois. The CAAPG assisted with rehabilitating the local Onchette variety and with identification of other traditional varieties, which include Douce Noire, Persan, Joubertin and Durif for reds; and Verdesse, Bia Blanc and Altesse for whites. Philippe Grisard of Savoie was a great mentor to Samuel.

Nearly all the vineyards on the plateau are now farmed organically, with care taken to maintain biodiversity with fruit trees and other crops around. Among the highest altitude vineyards in France, the climate is one of extremes, with frost a big risk, though the middle of the plateau, where most of the vineyards are, is usually spared hail. With the issue of planting rights having been somewhat relaxed, there is a more positive future and the area may apply for the right to use the IGP Isère label too – currently wines have to be labelled Vin de France.

View of the Dévoluy range from some of Samuel Delus’ vineyards in Prébois.

The Trièves pioneers

Domaine de l’Obiou

Web: domainedelobiou.fr

Samuel Delus gave this name to his estate in homage to the highest mountain of the Dévoluy, which dominates the plateau. His own first vineyards were planted in 2012, originally under the association auspices, and he now has just under 2.5ha in Prébois, not yet all in production, organically certified by Ecocert. On a predominantly limestone soil, with some glacial till, he grows all the local grape varieties mentioned above, along with Pinot Noir, Gamay, Gamaret, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay and Viognier, and from this large range makes red and white blends. Samuel has created a vaulted winery underneath his old family village house, originally where sheep were kept. He works with indigenous yeast and low sulphur levels, and ages both colours in old oak for at least a year after six months in stainless steel. Samuel is wary of high acidity and is convinced he needs long ageing to soften the wines; I loved the mountain freshness and rustic character in two vintages I’ve tried of his Conservatoire red from about half Gamaret with Persan and Onchette. For now, the whites do not reflect their Alpine origins so much, but these are early days in this estate’s development.

Gilles Barbe in one of Domaine Les P’tits Ballons’ vineyards in Mens.

Domaine Les P’tits Ballons

Email: domainelesptitsballons@orange.fr

Les P’tits Ballons is the 1ha estate of gorgeously sited vineyards around Mens, run officially by Pascale Barbe, formerly a librarian and the wife of Gilles, now retired, who of course lends a big hand. Originally association vines, they have Onchette among many other varieties and use the association winery in Prébois to make their wines, first released and sold locally in 2018.

Domaine Jérémy Bricka

Email: jeremybricka@hotmail.com

Jérémy Bricka is someone to look out for in future. With the aid of the community of Roissard, who wanted to have a vineyard again in their village, between 2015 and 2018 he has planted 4ha on a steep marl and schist slope above the Ebron river and aims to build up the estate to about 5ha. Jérémy worked for eight years for Domaine Guigal in the northern Rhône, giving him excellent experience in working on steep slopes. In 2011 he came to the Trièves as one of the founders of the Domaine des Hautes Glaces whisky distillery and fell in love with the area. He sold out of the distillery in 2015. There is a hectare each of Altesse and Douce Noire, along with Verdesse (a small first harvest in 2018); other varieties planted are Mondeuse Blanche, Persan and Etraire de la Dui, farmed organically. Jérémy’s small winery is at his home in Mens.

Others who have established small vineyards commercially are Jérémy Dubost and Maxime Poulat.