Chapter Two

A Map Found

Awful & grand; I might say, beautiful, but for the melancholy Seriousness which must attend every Circumstance, where the Lives of Men, even the basest Malefactors, are at Stake. The Hills, the Woods, the River, the Town, the Ships, Pillars of Smoke—so terrible and incessant a Roar of Guns, few even in the Army & Navy had ever heard before—all heightened by a most clear & delightful morning, furnished the finest Landscape that either art and nature combined could draw, or the Imagination conceive.

— Ambrose Serle, describing the British assault on Manhattan at Kip’s Bay during the American Revolution, September 15, 1776

The first time I walked through New York City I wondered what giant or god had created such a place. Buildings like cliffs, avenues like canyons, traffic flowing like rivers, parks brimming with forests and urban fields, a landscape populated by people seemingly from every nation and all parts of the continent, moving rapidly and with a deliberate attitude about their business, even if that business was none at all. I was intoxicated. I felt amazed at the ambition of the place and humbled by the power that had created it, for neither giants nor gods had built the “awful & grand” city; generations of New Yorkers, poor and wealthy, native and immigrant, had created the metropolis over a span of nearly four hundred years. Those people had each come for their own reasons, with their own peculiar visions, to this particular piece of land and shore and decided through some strange, collective logic, to raise a city on a scale beyond the power of the imagination to conceive.

A law professor once described to me lying beneath the pillars of the George Washington Bridge as a child, cupping his hands around his eyes, and peering up the river to imagine the view that Henry Hudson might have seen as he sailed in on his small wooden ship. Jacob Astor, the industrialist, imagined a city where the wealth of an entire continent could accumulate in the hands of just a few men (and preferably one). Robert Moses, the planner, had a vision for New York City that included the automobile and access to ball fields and swimming pools and, in the midst of the Great Depression, reconfigured the city for the future. Michael Bloomberg, the mayor and billionaire, envisioned a future where the economy always hummed, with less traffic congestion, no smoking, and better subways.

Hudson’s vision, to the extent that he had one, was to get rich and then get out of town. Adrian van der Donck, the Jonkheer who gave his name to Yonkers, New York, came to New Netherland in 1641, stayed, and became wealthy. He wanted others to join him and populate his lands; he wrote a lengthy paean to his new home called the Narrative of New Netherland (1650), describing the land as “naturally fruitful and capable of supporting a large population, if it were judiciously allotted according to location. … [It] is adapted to the production of all kinds of winter and summer fruits, and with less trouble and tilling than in the Netherlands. … The air is pleasant here, and more temperate. … ”

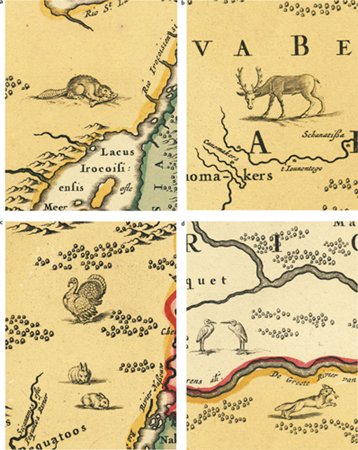

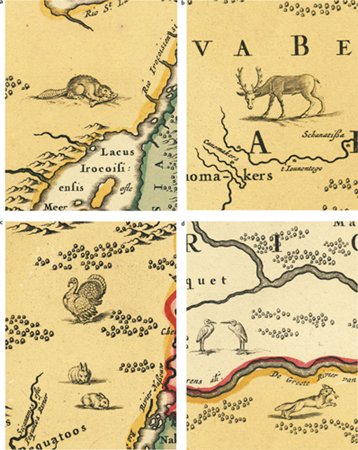

Many others agreed, describing not only the “sweetness of the air” (Daniel Denton, 1670), but also the “wonderful size of the trees” (Johann de Laet, 1633), “all sorts of fowls, such as cranes, bitterns, swans, geese, ducks, widgeons, wild geese, etc.” (Nicholas van Wassenaer, 1630), and “great quantities of harts and hinds …; foxes in abundance, multitudes of wolves, wild cats, squirrels—black as pitch, and gray, also flying squirrels—beavers in great numbers, minks, otters, polecats, bears, and many kinds of fur-bearing animals, which I cannot name or think of” (David Pietersz de Vries, 1633). Van Wassenaer complained, “[B]irds fill the woods so that men can scarcely go through them for the whistling, the noise and the chattering.” Peter Kalm had a problem with the noisy frogs (writing in 1748). Walking out of town, he noted, “[T]ree frogs, Dr. Linnaeus’s Rana arborea, are so loud it is difficult for a man to make himself heard.”

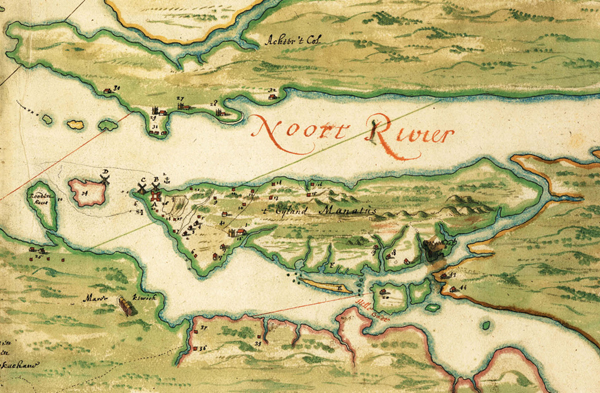

The Visscher Map, circa 1651, shows northeastern North America as the Dutch understood it in the years following Henry Hudson’s voyage. Manhattan is at the center of the map, at the mouth of the Hudson River, which in turn is the focus of the New Netherland colony. Europeans at the time knew the outlines of the continent, but were only beginning to explore its heart.

This detail of the inset image shows the small village of New Amsterdam as it appeared from just off the tip of Manhattan. Note the windmill, gallows, and rolling hills.

European explorers were astounded by the abundance of wildlife in the New World, including (a) beavers (note, though, that beavers are herbivores and do not eat fish as depicted), (b) white-tailed deer or elk, (c) turkey and cottontail rabbits, and (d) a red or gray fox and cranes, as shown in these details from the Visscher Map.

Probably the most enthusiastic chronicler was Denton, who ends his account with the following extraordinary passage:

Thus have I briefly given you a Relation of New-York, with the places thereunto adjoyning; In which, if I have err’d, it is principally in not giving it its due commendation; for besides those earthly blessings where it is store’d, Heaven hath not been wanting to open his Treasure, in sending down seasonable showers upon the Earth, blessing it with a sweet and pleasant Air, and a Continuation of such Influences as tend to the Health both of Man and Beast: and the Climate hath such an affinity with that of England, that it breeds ordinarily no alteration to those which remove thither; that the name of seasoning, which is common to some other Countreys hath never been known; That I may say, and say truly, that if there be any terrestrial happiness to be had by people of all ranks, especially of an inferior rank, it must certainly be here. … [I]f there be any terrestrial Canaan, ’tis surely here, where the Land floweth with milk and honey. The inhabitants are blest with Peace and plenty, blessed in their Countrey, blessed in their Fields, blessed in the Fruit of their bodies, in the fruit of their grounds, in the increase of their Cattel, Horses and Sheep, blessed in their Basket, and in their Store; In a word, blessed in whatsoever they take in hand, or go about, the Earth yielding plentiful increase to all their painful labors.

It can be a bit hard to credit descriptions like these for any place, but especially for a place like New York City, which has changed so radically over the intervening centuries. After all, these writers wrote from their own perspectives and understanding of the landscape, with specific ends in mind; many such descriptions were advertisements to entice others to leave their familiar lives in Europe and take a chance coming to the New World. Having arrived, they couldn’t believe their eyes. These early accounts carry the enthusiasm of a real estate speculator or a tourist new to town.

But it is also appropriate to ask whether we find descriptions like this incredible because we have lost the ability to believe them. After all, few places on the planet today have the abundance of plant and animal life that was commonplace in the America these early settlers describe. The wildlife films produced by PBS or the BBC require carefully cropped shots and often months of filming in national parks to get the few minutes of “wild nature” we see on television. Psychologists explain that we form our impression of what nature “should be” from what we saw as children. The problem is, if the nature we knew as kids was impoverished before our time, we might never know what we are missing. We lack the proper baseline.

Fortunately, in the case of Manhattan, we have ways to confirm these fantastic descriptions of the New World from the scientific evidence that nature leaves us: pollen collected in layers at the bottom of still ponds, the width of tree rings hundreds of years old, the shape of rocks and the chemistry of water, and the profile of soil with depth. Ecologists, working backward from how ecosystems function today, make educated guesses about how they worked in the past, backcasting from general ecological principles to the specifics of what might have been. Archaeologists glean information from the leavings of former inhabitants—shell middens, fireplaces, potsherds, arrowheads, hammerstones, and bones. In most places, information like this is sufficient, in concert with historical descriptions, to assemble an idea of the ecological past, but it’s not perfect; it is like attempting to view a painting when most of the canvas is torn and missing. The picture is tantalizing but incomplete.

The same would be true for Manhattan except that we have a canvas. What makes the quest to understand Manhattan’s historical ecology different from that of other places is the existence of an extraordinary map. The British Headquarters Map is not from the time when Hudson first came to New York, in 1609; it is from over 170 years later, from 1782 or 1783 (we can’t date it exactly), from the end of a bloody and costly war: the American Revolution. It is not a map of Manhattan primeval, but a map of a colonial eighteenth-century island girded for battle, with farms, fields, roads, and fortifications, and a small provincial town at its tip. But what the British Headquarters Map shows, at a scale and with an accuracy remarkable in a map more than two hundred years old, is the natural landscape of the island—the topography, shoreline, streams, and wetlands—which makes it possible for us to understand and paint a portrait of “the finest Landscape that either art and nature combined could draw,” a portrait of Mannahatta.

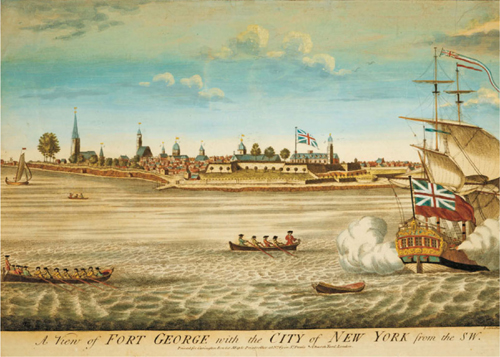

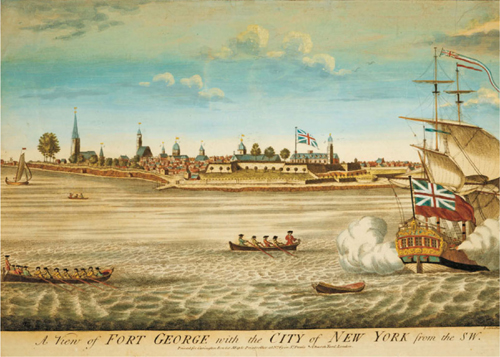

This view of Fort George and Lower Manhattan emphasizes eighteenth-century British control of the New York colony. Note the beaches beginning just below the fort and extending north under the steeple of Trinity Church.

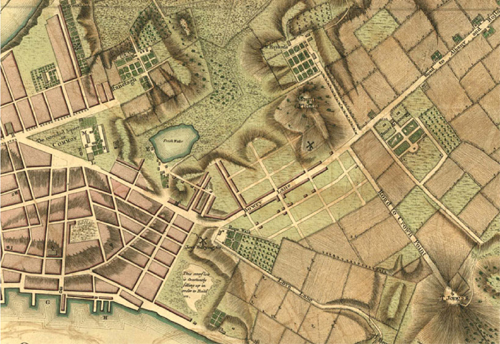

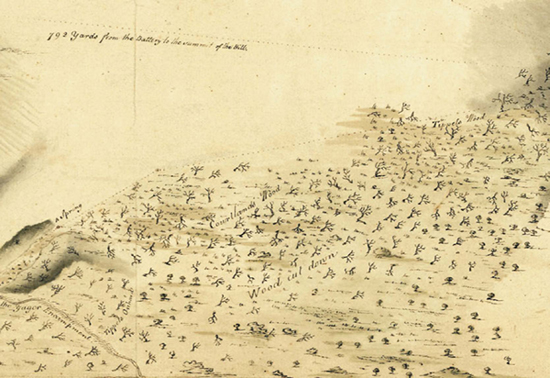

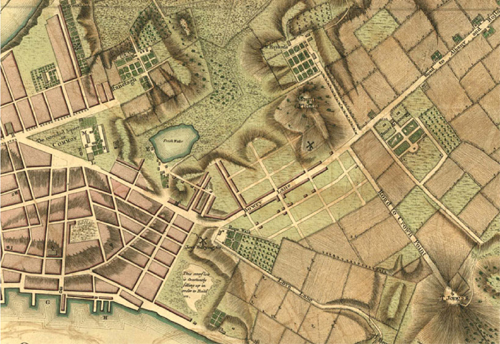

This detail from a 1766 plan of New York City before the Revolution, by British cartographer John Montresor, shows the outskirts of the city, where its blocks dissolved into farm fields (Uptown is toward the right). The note in the lower center reads, “This overflow is constantly filling up in order to Build on” and marks the former outlet stream of the Fresh Water into the East River.

This campaign map, engraved by William Faden, shows the disposition of forces on August 27, 1776, following the Battle of Brooklyn. After landing in southern Brooklyn and making a flanking attack across the glacial moraine at Jamaica Pass, the British army (red lines) was arrayed below Brooklyn Heights; the American army (blue lines) was redeployed along the Heights and the eastern shore of Manhattan Island, having been soundly beaten, but not destroyed.

The Campaign of 1776

To understand the British Headquarters Map and why it is so accurate, we have to go back to New York in 1776, in the second year of the Revolution, years before the map had been conceived. While the Founding Fathers debated the Declaration of Independence over that long summer in Philadelphia, the actual war was being fought around New York; for most of the next eight years, New York City would be at the center of the action.

In 1776, New York was the second largest city in the American colonies, with more than thirty thousand inhabitants (including black slaves and freemen), lagging just behind Philadelphia, and larger than Boston. Nevertheless, the city proper occupied Manhattan Island to only just north of today’s City Hall Park, with scattered buildings and farms in the Out Ward along the Bowery. Small settlements extended up the East Side to the small town of Harlem on the East River shore (located approximately where today’s East 124th Street meets the FDR Drive, under the on-ramp to the Triborough Bridge). Colonists cultivated apple orchards and planted wheat, barley, and rye alongside cows, pigs, and chickens on productive smallholder farms. Greenwich Village was just an intersection of two dusty country roads in a rolling landscape of fields and broken woods.

Despite its provincial character, New York was a center of both radical patriotic fever and wealthy Loyalist sentiment. In January 1770, tensions came to a head in the Battle of Golden Hill, when a boisterous group of “Liberty Boys” had a series of run-ins with British soldiers stationed in New York. The elderly British governor Cadwallader Colden (a noted botanist) and the rich, conservative Delancey family had just agreed to support the newly enacted Mutiny Act with an appropriation of two thousand pounds for quartering British troops in the city. During a fight in a wheat field in the middle of town, a group of Redcoats, after being provoked by the Liberty Boys, “cut down a Tea-Water man driving his Cart, and [injured] a Fisherman’s finger.” Some later claimed the “Battle of Golden Hill,” with its hurt heads and fingers, to be the first blood of the Revolution, predating the Boston Massacre by about six weeks. For its part, Golden Hill was named after the yellow celandine, an introduced flower, which bloomed between William and Fulton, John and Cliff streets in spring. The conflict would simmer in council chambers and flare up into mob demonstrations for another five years, until armed fighting broke out in 1775, with the shots fired on Lexington Green in Massachusetts.

What made New York essential to the armies vying for the colonies was the city’s strategic position at the mouth of the Hudson. The North River, as it was called then, could carry warships 120 miles, nearly to Albany, and from there it was only a few overland portages and long rows up Lake George and Lake Champlain to British Canada. With control of the Hudson, King George’s army could separate the fractious New England colonies from the rich agricultural lands of the mid-Atlantic. Control the Hudson, British military leaders in London reasoned as they regrouped in late 1775, and you control the rebellion. And to control the Hudson, you must first control New York.

This geography was not lost on the American Revolutionaries either. In March 1776, General George Washington moved his army south from New England to Manhattan, forcing the few British troops in possession onto naval vessels in the harbor and into fortifications on Governors Island. In late July the British landed a huge expeditionary army of British regulars and German mercenaries from Europe—over 22,000 men—on Staten Island; in August, they shifted these troops across the Lower Harbor on a hundred-plus British naval vessels, manned by 10,000 sailors—one of the largest amphibious operations of the age. The troops landed unopposed on the plains of Bushwick and Flatbush. The Battle of Brooklyn began three days later, in the early morning hours of August 26, when the British made a surprise flanking move over Jamaica Pass, turning Washington’s left flank and driving his army, with heavy losses, back to Brooklyn Heights, from where it had been deployed across the rocky hills of the glacial moraine, in what is now Prospect Park and Greenwood Cemetery.

Three nights later, Washington evacuated his men across the East River, giving up the defense of Long Island and refortifying New York City. On September 15, the British continued the dangerous minuet, landing fifteen thousand troops five miles above the city proper on “York Island,” near Kip’s Bay—once again behind the American lines. A fifteen-year-old American private, Joseph Martin, described the massed red uniforms of the invading force “like a clover field in full bloom”—and then the cannonade started from four British warships armed with eighty cannons tied not a hundred yards from shore, just south of the site of the United Nations building. While the thin American line scattered, the British troops formed on top of Murray Hill (Mrs. Murray apocryphally offered the British commanders tea in her farmhouse as a delaying tactic), and Washington rapidly recalled his troops from town along the Greenwich Road, then through the woods of Midtown Manhattan to the Bloomingdale (our Upper West Side). The British had taken the city.

These next two views painted by Thomas Davies in November 1776 show the assaults that completed the British conquest of New York.

The assault on Fort Lee in New Jersey required a steep climb from the Hudson River to the top of the Palisades. Note the waterfall and sparse cover of eastern white pine on the rocky cliffs.

The simultaneous assaults on Fort George (middle foreground) and Fort Washington (background) were made through dense mixed deciduous forests fringed with fall color. The clear-cuts on the hills and the low-lying land around Sherman Creek provided positions for cannons.

Sharp skirmishes continued for several more days, particularly across Morningside Heights, around the present-day campuses of Columbia University and Barnard College, and near Point of Rocks in West Harlem. (Morningside Heights takes its name from the glow of the sun on the eastern slopes, as viewed from the Harlem Plains.) One clash took place in a buckwheat field near Broadway and 116th Street. In the dry woods and fields, Americans were giving as good as they got, but the overwhelming British land forces, supplemented by naval guns stationed in the Hudson River, eventually forced the Americans to retreat.

The desperate Rebels even tried a submarine attack, the first one in recorded history, to deter the British navy in New York Harbor. David Bushnell, a Connecticut inventor, had devised an oaken “Submarine Vessel [that] bore some resemblance to two upper tortoise shells, attached together.” The Turtle, as it was called, was outfitted with thick glass plates that, in clear waters, allowed enough light to penetrate to read a book at three fathoms (eighteen feet deep). Hand winches propelled it forward and sideways, a rudder gave it direction, and a valve and set of pumps enabled it to ascend or descend. Bushnell also invented the first torpedo (which he named after Torpedo nobiliana, a fish capable of delivering an electric shock of up to 220 volts). Bushnell’s torpedo contained 130 pounds of gunpowder, but during the inaugural engagement of the Turtle, a metal plate on the bottom of the target ship kept the bomb from attaching. Attempting to retreat, the volunteer submariner, Ezra Lee, lost his way. Surfacing to get his bearings, he was sighted by British soldiers on Governors Island; they pursued, ultimately causing Lee to let loose his torpedo bomb, which floated up into the East River, where it exploded harmlessly. On hearing the explosion in northern Manhattan, Washington’s second-in-command, the indomitable General Israel Putnam, said, “God curse ’em, that’ll do it for ’em.” Lee and the Turtle were saved by a whaleboat, which pulled them ashore in the dark.

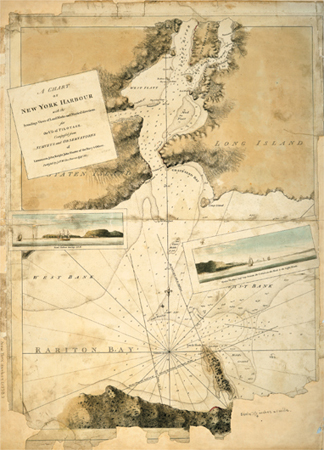

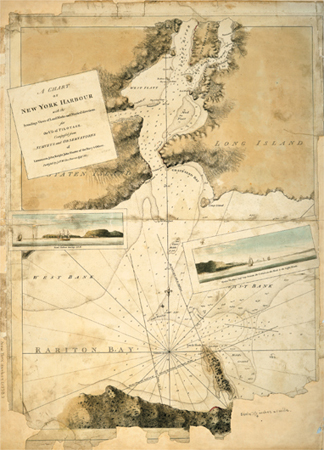

The British military created hundreds of maps of the New York City region during the American Revolution. J. F. W. DesBarres published this chart of New York Harbor in the Atlantic Neptune in 1779, with navigation views to help ships find their way through the sandbars that made entry into the harbor hazardous.

In October Washington decided that Manhattan Island could no longer be defended and retreated north, leaving a garrison of 2,300 men at Fort Washington, at the highest point on the island, in what we today call Washington Heights. British forces chased the American army through lower Westchester (our Bronx) and eventually to the White Plains, where yet another indecisive battle was fought. In November the garrison remaining on Manhattan surrendered to British forces after a fierce bombardment and assault, ending the armed resistance. The British renamed Fort Washington “Fort Kynphausen,” as it is labeled on the British Headquarters Map, in honor of the German general who led the attack.

The British had won the campaign for New York. They had driven Washington’s forces from Manhattan Island with casualties and hard lessons learned, but without the devastating loss that would have meant an early end to the war. The Rebel army, bloodied but largely intact, survived to fight another day. British forces would control New York City and Manhattan Island for the rest of the war, making occupied New York the headquarters of their operations and establishing a fortress for Loyalist Americans and British troops alike that swelled the city’s population more than twofold. But no one, on either side, really believed that the battle for Manhattan Island was over.

The British Headquarters Map

The British immediately set about fortifying the city and making preparations for a large-scale attack, which, as it turned out, never came. Despite numerous skirmishes and midnight raids nearby in the Bronx and New Jersey, the Americans could never find a plausible way to launch an assault against the well-guarded island. Meanwhile, the British took control of City Hall on Wall Street (the site of today’s Federal Hall) and made it their military headquarters; they established martial law and quartered troops with city residents. They redesigned and added on to the fortifications begun by the Americans. Small fortresses topped nearly every hill in Lower Manhattan: Bayard’s Mount, Jones Hill, Richmond Hill, and Corlear’s Hook all had their defenses; redoubts overlooked the Lispenard Meadows and the East River shore. (Several of these features can be seen on the detail of the British Headquarters Map that opens the chapter.) The British completed a wall that ran practically from one side of Manhattan to the other, along the line of modern-day Grand Street, and defensive walls were constructed behind the beaches along the Hudson River shore up to West Thirty-third Street. They dammed Minetta Water to create a lake in what is now the West Village, and farther north fortified McGown’s Pass; built a redoubt at Horn’s Hook, overlooking Hellgate (where Gracie Mansion is today); constructed three walls across Washington Heights; and garrisoned Fort Kynphausen, Fort Tryon, Marble Hill, and Cox’s Hill (our Inwood Hill). And, importantly for us, they found time to make maps. Maps, then as today, were essential data for prosecuting a war.

Maps served a variety of military purposes, especially for invading forces unfamiliar with the terrain. They provide leaders a means of rapidly coming to understand strategic factors—the dispositions of troops, the distances between places, the difficulty of travel, and the geographic relationships between different political units. Maps are also useful tactically—to plan surprise attacks, to place defenses, and to maneuver against the enemy (to draw him out, to box her in). Maps have been used in war since antiquity and were instrumental to the conduct of battle in the eighteenth century; they are even more crucial today. Modern militaries have generated many technologies that have revolutionized mapping: satellite imagery; the global positioning system (GPS); and the geographic information system (GIS), a means of analyzing maps using computers. Fortunately, these same technologies have found other uses—one can map trees as easily as bombs.

Before the Revolution began, from the time of the French and Indian War in the 1750s and 1760s through the opening of hostilities in 1775, a number of detailed surveys of North America had been undertaken by British cartographers. James Cook, who later charted Hawaii and much of the tropical Pacific, cut his teeth in surveys of the cold Saint Lawrence River. J.F.W. DesBarres mapped much of the colonial coastline in 257 plates of the Atlantic Neptune series, which were used for navigation well into the nineteenth century. Numerous surveys were conducted and maps drawn to delimit the boundaries of colonies in dispute, each colony viewing its territorial integrity as paramount, and the English authorities eager to consolidate their North American lands against the French and the Spanish.

These officers drew maps based on geodetic control, meaning that they located places according not only to local references, but also to where they were on the planet, with longitude and latitude fixed by astronomical observations. They mapped at carefully selected scales and used defined map projections, so that navigators could derive distances between any two objects from the map with a compass and ruler. They agreed on a set of standardized symbols, to show, for example, forests, coastlines, beaches, and wetlands, so that different maps had comparable conventions. To achieve these ends, most of these surveyors were trained at military academies, including the one in Greenwich, England, considered one of the best of its kind at the time. Their maps were not only accurate but beautiful, frequently supplemented by painted perspective views illustrating the appearance of the landscape for navigation. Unfortunately, the outbreak of wartime hostilities brought these ambitious, broad-scale surveys to an abrupt end.

The British Headquarters Map, circa 1782–83, once described as a “topographical and historical encyclopedia” of Manhattan before modern development, shows the original hills, streams, shoreline, and wetlands of the island.

However, wartime gave cartographers another motivation to produce exceptionally accurate maps. On Manhattan the British generals had a corps of well-trained, experienced cartographers attached to the engineers, the “Pioneer Guides,” and teams of professional surveyors at their disposal. And these mapmakers had time—seven years in total, from November 1776 to November 1783—to draft, redraft, and perfect their understanding of the landscape. For Manhattan and the surrounding area (mainly Staten Island, western Brooklyn, western Queens, and the western Bronx), the British army prepared hundreds of maps. Many of these are now housed in archives in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Created toward the end of the war, the British Headquarters Map was the culmination of their efforts. One expert has described it as “a topographical and historical encyclopedia of the area during the Revolution.” Drawn at a large scale, one inch to eight hundred feet, the map shows all of Manhattan Island and parts of Brooklyn in a detailed, colored manuscript covering two irregularly shaped sheets of paper, together over ten feet long and three feet wide. Features were sketched with pen and ink, then hand colored with blue, pink, brown, and green watercolor. Combinations of colors and hatching demarcate different features, including land use and infrastructure and natural features like hills, wetlands, and streams.

The British Headquarters Map documents the geography of significance to military planners: the fortifications and defensive works, the extent of the city proper, a small suburbia with treelined streets and backyards in today’s Chinatown, a road network extending from the city toward small settlements in Greenwich Village and Harlem, important crossroads, fields and orchards, individual buildings, estates, and even formal gardens and alleys of trees.

When I first saw the British Headquarters Map, I was attracted, like almost everyone else who examines it, to the topography. One can make out Murray Hill, the rocky slopes of Central Park, and the heights of northern Manhattan—Morningside Heights, Harlem Heights, Washington Heights, and Laurel and Inwood hills. But the British Headquarters Map also shows topography where today there is none—in Midtown, in the East Village, down through the Bowery, even under Downtown. There was once a hill just south of Wall Street, near the bronze Charging Bull at Bowling Green, not far from a stream along Beaver Street. What had happened to that hill?

But more than hills and dales, the British Headquarters Map also shows what to those hard-nosed military mapmakers were annoying tactical impediments, the same features which we would celebrate today as ecosystems: marshes, forests, beaches, rivers, ponds, streams, cliffs, coves, and bays. When I looked at the British Headquarters Map, I saw in the markings for “salt grass fields” the great green swards of salt marshes on the Lower East Side; in wavy blue hachures I saw red maple swamps in Times Square and precious bogs in Central Park; in dots I saw outlined sandy beaches on the Hudson River shore; and over the rest of the map, nearly everywhere across the upland, I saw the potential for forests—deep, old, massive forests. Even the human features told a story, for in the distribution of farms and orchards, the paths of the dirt roads were suggestions of the underlying soils and geology. I realized that the map provided important insight into the ecological foundations of the Manhattan landscape, the canvas of a natural landscape past, not just as it appeared in 1782, but as it existed long before, back in the time of Hudson, back when it was Mannahatta. The essential first hurdle to gaining that insight, though, was to lay the British Headquarters Map over a modern map of Manhattan and judge its fit. Could the geography of 1782 be matched to the geography of 2000?

A Remarkably Accurate Map

In 1997, Robert Augustyn and Paul Cohen, private map dealers in New York, published Manhattan in Maps (Rizzoli, 1997), a book of maps of the city that they felt were not well known or sufficiently appreciated, especially maps that were in private collections or in European archives. Prior to their book, the only version of the British Headquarters Map that was available in America was a tracing done by the American antiquarian Benjamin Franklin Stevens, who published a set of lithographic copies in 1902. (Facsimiles can be found at the New York Public Library, the Brooklyn Historical Society, and City University Graduate Center in New York.) Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, the great early twentieth-century compiler of images of Manhattan, had published a small version of Stevens’s tracing in his epic Iconography of Manhattan Island (R.H.Dodd, 1917–29), but with uncharacteristically little comment. Even Stevens’s memoir gives the map only a single sentence.

In my work at the WCS as a landscape ecologist, I deal with a lot of maps from a lot of different places. In order to make these maps work together—whether the goal is saving tigers or understanding the history of New York—it is essential to get them into a common geography, so that maps of different kinds can be laid over one another, like layers in a cake. If I could “georeference” the British Headquarters Map to a known coordinate system, I could relate its depiction of the old hills and valleys to their modern street addresses and thus find that phantom hill near Bowling Green.

Critical to landscape ecology is the set of computer hardware, software, and spatial data called, collectively, a geographic information system. In a GIS, a map is really composed of two kinds of information: the spatial features (what we normally think of as the map) and an attribute database of numbers or words linked to features on the map. In the database each dot or squiggle on the map can have different kinds of associated information. For example, a stream might have its length, its width, and its flow rate associated as data; a hill might have measurements of its elevation, slope, and facing direction (called the aspect) tied to its representation. The GIS allows people to make distance and area measurements, to sort and query the databases, to analyze layers against one another, and to run ecological or other kinds of models. The police use GIS to analyze patterns of crime. McDonald’s uses GIS to figure out where to put restaurants. Internet surfers use a kind of GIS when they log on to Google Maps or MapQuest.

With these possibilities in mind and my curiosity piqued, one Sunday afternoon, after much internal debate, I took the initiative and sliced open my beautiful, well-loved, not to mention expensive, copy of Manhattan in Maps, then carefully extracted the pages of the British Headquarters Map. To get a clean scan, I had to lay the map flat against the scanner plate. Next, I downloaded a modern-roads layer of the city from the U.S. Census Bureau. Then I reassembled the pieces of the British Headquarters Map in the computer and began the laborious process of picking out “control points,” matching features on the British Headquarters Map to features in the city today.

These details from the British Headquarters Map show (a) Murray Hill, (b) Greenwich Village, (c) Harlem, and (d) Inwood, in northern Manhattan.

After a few hours of work, I had my first results: I had matched the British Headquarters Map view of Manhattan to the modern-road network of the city with a spatial error of about 250 meters (820 feet, or roughly two and a half football fields). Not bad, but not great either. I felt disappointed—it wasn’t clear that sacrificing my book had been worth it—but also intrigued; it was closer than I would have guessed. Strangely, most of the error came from the lower section of the city, which, rather than extending straight, in line with the rest of the island, pointed like the bottom of the letter J toward New Jersey. Manhattan looked vaguely like Italy. The problem was, of course, that Manhattan doesn’t have a toe like Italy—Manhattan is long and narrow and reasonably straight, as islands go.

A couple of nights later, I was again examining my reproduction of the British Headquarters Map when I noticed a faint dotted line that extended across the map about a third of the way up the island. Recall that the original British Headquarters Map was drawn on two large sheets. To assemble the full map, these sheets need to be overlapped. I thought, what if the mapmakers meant for them to be aligned along this dotted line rather than assembled straight across, as displayed in Manhattan in Maps? Using the computer again, I reoriented the upper sheet to match the diagonal line, then reassembled the map and applied my control points. The georeferencing this time was much better—only 100 meters (320 feet) off, and better still, New York no longer leaned toward New Jersey. It also solved another problem that I hadn’t noticed before. Although not immediately apparent on casual examination, the label for the East River was misaligned in the photograph that Cohen and Augustyn had published. The E in the label for the East River appears offset from the remaining letters ast River by several inches. Realigning the sheets properly fixed this label and restored the geometry of Manhattan, and resulted in a more precise match between Manhattan today and Manhattan circa 1782.

Emboldened by these results, I planned a visit to The National Archives of the United Kingdom, where the original British Headquarters Map is kept. Once there I found, to my amazement, that Manhattan in Maps wasn’t the source of the problem—the original map was! Someone had glued the two pieces of the British Headquarters Map together, but not in the right place. Nevertheless, I obtained a one-to-one photograph of the map from the archivists, had it professionally scanned, reassembled the high-fidelity version, gained access to a much more accurate digital road map of the city—and embarked on an eighteen-month-long period of research into place-names and accounts of Manhattan’s historical geography (see Appendix A). In spots where I knew both what the feature was on the British Headquarters Map and where it should lie in the modern geography of the city, I was able to place over two hundred control points.

This beautiful hand-colored 1776 map by Charles Blaskowitz shows Hellgate, between Horn’s Hook (Manhattan), where Gracie Mansion is today, and Hallett’s Point (Queens). Note the salt marshes on both sides, depicted with wavy, uneven hachures. This same area is depicted in the reconstructed view on this page.

The misaligned label for the East River on the British Headquarters Map was the final clue about how to assemble it correctly.

“Georeferencing” the British Headquarters Map in a geographic information system (GIS) allowed us to overlay the modern-road grid. Note the match between the colonial and modern streets.

Adding another layer to the GIS shows the modern building footprints against the eighteenth-century geography of the city.

The final georeferencing of the British Headquarters Map places its features within 40 meters (130 feet, or equivalent to about half a north-south block in Midtown Manhattan) of Manhattan’s modern streets. Moreover, many of the features shown on the British Headquarters Map have historical documentation in other sources, often with descriptions dating from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. There are hills with names like Verlettenberg, Golden Hill, Mount Pitt, Mallesmitsberg, Richmond Hill, and the Kalck Hoek; valleys called Bloemmarts Vly, Smits Fly, Konaande Kongh, and Manhattanville Pass; streams like the Maagde Paetje, Lispenard’s Creek, Minetta Water, Saw Kill, and Old Arch Brook. These titles reflect the layers of Native American, Dutch, British, and American naming that enlivens the history of New York City. Moreover, the georeferenced map means that not only are the named features available to us, but all the unnamed features are as well—the details of the slopes, wiggles, and bends of an entire island are unveiled for study. The British Headquarters Map opened up a past natural landscape, Mannahatta, at a scale unique in the study of historical ecology. Everything that follows, everything this book is about, suddenly became possible.

But there was still one more question that needed to be answered, a question a friend once asked me: Why was the map so accurate?

Why So Accurate?

Actually georeferencing the British Headquarters Map with this precision begs the question, how could these eighteenth-century cartographers have made a map with so much detail and spatial accuracy? Most attempts to reference historical maps like the British Headquarters Map to modern coordinate systems yield poorer results, so much so that it is out of fashion in historical studies to even try. Today maps are “texts” to be read for what they tell us about the perspectives and prejudices of times past—not necessarily as accurate records of actual geography. Such high levels of spatial fidelity from eighteenth-century maps are only known from a few English county maps georeferenced in the 1970s. It was clear that in controlled, domestic environments—the English countryside, for example—eighteenth-century surveyors could do a high-quality job. But what about during a war on a faraway continent?

The answer is not so clear, but I have a hypothesis. I believe that the British Headquarters Map is an accurate depiction of the landscape because of the fortunate confluence of three factors: one part strategy, one part affection, and one part ambition—as it turns out, not an uncommon recipe in the history of great New York creations.

First and most importantly, New York City was strategically significant throughout the war, a Loyalist center, the location of the British headquarters in the Americas, and a vital port for embarking troops and necessary materials from Europe. As the center of the British war effort, the headquarters was attended by the best the army had to offer, including cartographers. Although we don’t know who exactly drew the British Headquarters Map, we do know that many famous British cartographers worked in New York around the time it was drawn. Among these was Captain John Montresor, who had offered his tent to the American Patriot Nathan Hale the afternoon before his hanging in September 1776; for a time Montresor owned Ward’s Island, or Montresor’s Island as it was called until Rebels burnt his house in 1777. Another was Charles Blaskowitz, who drew several fine manuscript maps, now in the Library of Congress and other archives. Two mapmakers from Scotland, Andrew Skinner and George Taylor, produced a striking water-color map of the river valleys of the Bronx, showing the numerous streams and tidal wetlands of its fecund shores. These men and others produced maps of beauty and surprising accuracy.

Second, there is the personality and personal history of Sir Henry Clinton, the general in charge for the longest period of any British general during the war. Clinton had personal reasons for a particular affection for the Manhattan geography. His father had been governor of the New York colony in the 1740s and ’50s; he spent his main teenage years (1743–46) growing up nearby, on Long Island. Clinton’s first military posting was on Manhattan as a lieutenant of fusiliers in 1745. He later served in Germany during the Seven Years’ War, where maps were central to the conduct of war. Frederick the Great once wrote, “Above all, a general must never move his army without being instructed about the place where he leads it and without knowing how he will safely get it to the ground where he wants to execute his plans.” Clinton took this advice to heart.

Moreover, Clinton was by inclination a man of maps. Professor William Wilcox wrote in his 1945 biography of the general that Clinton was at his best as a planner, and “his plans were based, above all, upon sound geographical premises. He had a strategist’s instinct for a map. … He was continually advising his friends to look at one, and assuming that they would see in it what he did, an outline of future operations.” It was Clinton who suggested the flanking move around Washington’s position in 1776 through Jamaica Pass and who criticized his fellow commanders, particularly his superior, Lord William Howe, for their lack of geographic sense. Clinton had urged before the assault at Kip’s Bay that Howe land north of Washington at King’s Bridge and cut off all of the Rebel army before it could escape Manhattan, as it eventually did. The suggestion was overruled, much to Clinton’s vocal annoyance (subtlety and discretion were not Clinton’s strong suits).

Unfortunately, if it was Clinton who ordered the creation of the British Headquarters Map (we don’t know for certain, but it seems likely), he was not able to stay on in America to see the final benefit of his mapmaking diligence. Like his predecessor Howe, who was sacked after General John Burgoyne’s failure in 1777, Clinton was recalled to London after General Charles Lord Cornwallis exceeded his orders and marched north when he should have stayed in the South, becoming trapped at Yorktown and thus losing his army and effectively ending the war for the British in 1781. Clinton took the fall for Cornwallis even though he was two hundred miles away in New York and had told Cornwallis previously to stay out of Virginia. Regardless, it was Clinton who returned to England a failure.

Clinton’s name is nowhere mentioned on the British Headquarters Map, suggesting it was not complete at the time of his dismissal, but interestingly, his successor’s name is everywhere. The British Headquarters Map may be so accurate because of Clinton’s predilections and his mapmaking team, but the credit for the map, with its beautiful depiction of a landscape prepared for war, may have belonged to Clinton’s replacement, the last British commander in chief, Sir Guy Carleton.

Carleton Takes Over

The third factor behind the British Headquarters Map’s accuracy may have been Carleton’s ambition. Carleton was technically Clinton’s senior, having been made general four months before Clinton in 1763; he had served honorably in Canada, first under General Wolfe during the French and Indian War and then in defense of Quebec in 1775, but a bitter personal dispute with Lord George Germain, the American secretary, kept Carleton in Quebec and out of the top British post in North America. In the darkening days of an unpopular war, however, Germain was sacked, thus giving Carleton an opening through which he could finally rise to the coveted post, though too late to have any real military impact.

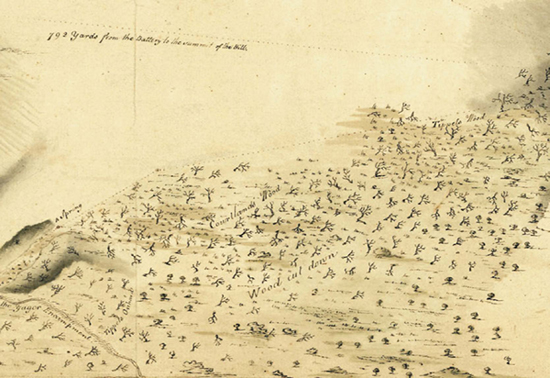

This detail from a 1778 map of King’s Bridge, in northern Manhattan, shows the devastation brought to bear on Manhattan’s forests during the Revolution, lamented by George Washington in 1781. Note also the indication of a spring and the names of the woods.

In the years after the war, liberated New York City rebuilt. This view of Wall Street from 1789 shows the Old City Hall, now Federal Hall, the former British headquarters during the hostilities and later the place where George Washington was sworn in as the first U.S. president.

The British Headquarters Map may have contributed to Carleton’s and Clinton’s relative places in history. Six reference notes on the map document Carleton all over the island preparing the city for an attack, which after 1781 was highly unlikely. “Sir Guy Carleton stops work on defenses”; “Sir Guy Carleton orders defenses extended to the right”; and so on, keyed with neat letters to locations on the map. Indeed, from a certain perspective, the map presents a testament to the energetic efforts of Carleton to defend a city and countryside flourishing even as it’s being girded for war. A series of strategically placed, well-connected forts, bastions, and walls encircle the city; orchards stand in stately lines; mansions appear with formal gardens; fields are planted across the Harlem Plains—all seems well.

The problem was, all was not well with the city or the countryside. The city had burned twice during the war, once in 1776 and again in 1778, fires that left nearly half of New York City in charred ruins. Trinity Church would not be rebuilt until 1790. Similarly, the countryside was in bad shape. The winters of 1779/80 and 1781/82 were particularly harsh and frigid; the cold was so severe that New York Harbor froze solid enough for the British to drag their cannons from Staten Island back over the ice to the Battery in Manhattan. In the cold, the price of firewood skyrocketed, creating enormous pressure on the forests and standing wood of any kind. Orchards, fences, buildings, ships, and, of course, the remaining forest itself were consumed for firewood, desolating the landscape. George Washington personally reconnoitered the northern part of the island from the adjoining Fordham Heights in 1781, observing the scrubby wasteland where thick woodlands had once stood. He wrote in a letter, “[T]he Island is totally stripped of Trees, & wood of every kind; but low bushes … appear in places which were covered with wood in the year 1776.”

The British Headquarters Map, accurate in so many aspects of the natural landscape, seems to have some significant omissions when it comes to the human landscape. To what end? It seems that in its final incarnation, the British Headquarters Map, begun as a mapping tour de force for Clinton, became a propaganda piece for Carleton’s successful administration back in England. In a time before photographs, it was compelling visual testimony to his work. The map returned to England with Carleton’s papers and passed from there eventually through the War Office into the British National Archives. (Clinton’s papers, in contrast, eventually found their way into the archives at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan.) After the war, Carleton remained in favor, and was created First Lord Dorchester and reappointed governor of Quebec. Today he is remembered in the names of grammar schools across Canada and by Carleton University in Ottawa. Clinton was ignominiously forgotten, spending the last twenty years of his life writing a long, defensive account of his actions in America, resentful of his friends and colleagues. He is a footnote to history. We have no further record of the British Headquarters Map until Stevens gave it that name in 1900.

Whatever its origins and purposes, the British Headquarters Map is a remarkable record of Manhattan Island’s landscape; the backbone of its ecology; and the canvas on which the nature of Mannahatta could be drawn, with specificity and precision. By placing the map in the modern geography and stripping away the eighteenth-century farms, fields, and towns, we have the opportunity to travel back in time toward the 1609 landscape, to envision what Hudson and his small crew had found. The British Headquarters Map means that we can frame the fundamentals of nature in the right places and in the right configurations, and thus take the first step toward discovering a new way of seeing what came just before New York City.

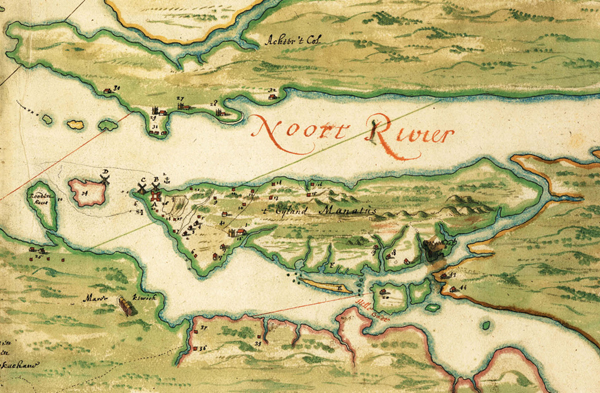

The Manatus Map, from 1639, is the first depiction of Manhattan as an island. Note in this transposed detail the prominent windmills, the tidal inlets, the Lenape settlement in Brooklyn, and the indications of Manhattan’s hilly terrain.