20

Educational mobility, England and Germany1

Good politics has always seen well-funded, public provision of education as a vital pathway to delivering the Good Society. This article draws on recent evidence from Germany and the UK to show that even in more equal societies, such as Germany, attention still needs to be paid by progressive politicians to education – in particular, the importance of non-elitist, comprehensive education systems for all, regardless of means.

Educational systems in England and Germany affect social inequalities in different ways. Social inequalities are narrower in Germany, but not thanks to German education systems. The English education system is highly discriminatory too, but it would be a mistake to believe that the German model is much better.

Germany follows an elite model of higher education.2 From the age of 10, children are allocated into different types of secondary schools. Admission to the Gymnasium (grammar school) leads to a qualification that allows university access after age 17. Hauptschule (secondary modern schools) are nowadays considered a dead-end path leading to limited chances in a highly competitive society. The latest statistics suggest that there is a very limited mobility between the different secondary school tracks – most of it leading “down” from Gymnasiums to the other tracks. The figures reveal growing inequalities, characterised by 8% of the 15-17 year olds leaving the educational system without any qualifications, and only 72% of 18-25 year olds gaining an upper secondary school qualification, which is now considered to be the minimum qualification for success in the labour market.3

In Germany gross enrolment in tertiary education remains at a level of approximately one third (graduation figures are considerably lower at 22%), being far lower than in other European countries. Federal governments4 never seriously attempt to change this, and even left-wing governments focused more on increasing education mobility by subsidising access to universities for the poor rather than enabling a higher university attendance rate overall. What appears to create more equal opportunities for all turns out to be ineffective. Exclusion from better education predominantly takes place when entering secondary school.

By 2007 public loans or grants only accounted for 13% of university students’ funding in Germany, some 53% of the support came from parents (or families). The rest was raised by the students themselves, loans and other sources. Thus support for the poor fails even for the few who gain a higher secondary qualification. In addition, political attempts to establish comprehensive schools to separate children at a later stage have taken off very slowly, not least because of the decentralised structure of education policy. Income inequality in Germany may be lower than in England but the gap between rich and poor there has been widening in recent years. Social status counts as much again now as it last did before the Second World War.5

England, achieved its most recent and (in contrast to Germany) quite radical changes in higher education under the New Labour government, which moved the country towards a partially private system, changing the funding structures considerably and greatly reducing the public subsidisation per student. Unexpectedly, the new policy proved to be successful in increasing the gross enrolment up towards 36% of those aged under 20, and probably 50% of those aged under 30 if these trends continue (which is a big if ). As a result, educational mobility is considered to be above average in Britain as compared to other affluent countries (higher ranking on educational mobility were Finland, New Zealand and Denmark). 6 A huge and largely unrecognised part of this success is the beneficial legacy of mass secondary comprehensive education. Education proves to be one of the few factors that reduce inequalities in England, although it fails to reduce inequality in general. Private education is important for the wealthy to distance themselves from the rest of the educational system.7 Of all the OECD countries the UK spends more than any other8 on private secondary education, almost all of that spending being in England.

Comprehensive secondary education helps partly wipe out the disadvantage the English suffer from concentrating almost a quarter of their resources on just 7% of children in private schools, children selected because their parents are rich. The most telling statistic that reveals this is that more children from the city of Sheffield attend university than from the city of Bristol. Sheffield is poorer but has the great advantage of very few private schools (unlike Bristol). 9 Scotland and Wales do even better in different ways. Northern Ireland still has its own problems with educational segregation, but by class more than religion (hence above we have mainly talked about England).

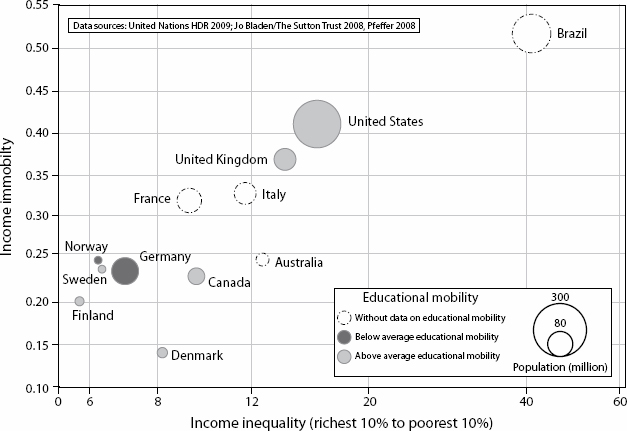

The graph below shows how it is possible for Germany, a country with high social equality and mobility to also have below average educational mobility. Radical changes in education happen seldom, but they do exist, such as the 1970s comprehensivation of British schools. More recently Sweden, for example, targeted educational inequality in the 1990s and went from a highly selective educational system towards comprehensive tertiary education provision now aimed at more than 80% of young people. However, the Swedes also experimented with parent-led schools which worked well at first but are currently causing problems.

High social mobility (represented by low ‘income immobility’ on the graph above) tends to reflect low social inequality. That is why all the circles line up so well in the graph above. However, the position of a country on this graph does not reveal whether its system of education is in general progressive or regressive. There are better places for good politicians to look than both Germany and England for how best to teach young people and thereby promote the Good Society.

Figure 1: Social/educational mobility and inequality – international comparisons