35

The influence of selective migration patterns1

Abstract

The research reported here uses New Zealand data on smoking behaviour that was collected in the 1981, 1996, and 2006 national censuses. Evaluation of the extent to which differential migration patterns among smokers, former smokers, and nonsmokers have contributed to geographical inequalities in health in New Zealand suggests that the effect of selective migration appears to be significant over the long term. This effect includes the arrival of large numbers of nonsmokers from abroad to the most affluent parts of New Zealand. The recording of these events and the high quality of the census in New Zealand provides evidence of one key mechanism whereby geographical inequalities in health between areas can be greatly exacerbated across a country – differential migration by health status. This assertion has important implications for studies monitoring spatial inequalities in health over time, and research investigating “place effects” on health.

Key words:health inequalities • migration • mobility • New Zealand • smoking

Recent studies have consistently demonstrated that in most Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries over the past twenty to thirty years, there has been a polarisation in health between geographical areas (Davey Smith et al, 2002). Using various area-level measures of mortality and morbidity, researchers have tended to find that, although there have been considerable improvements in health at national levels, these gains have not been consistent in all regions. In particular, there is clear evidence that less socially deprived areas have tended to benefit disproportionately from these improvements. For example, in the United States, there are extensive health inequalities among local counties, and this divide has widened considerably in recent decades (Singh and Siahpush, 2006). Between 1980 and 2000 there was a 60 percent increase in the size of the gap in life expectancy between the poorest and richest tenths of the population (Pearce and Dorling, 2006). In New Zealand, life expectancy increased between 1981 and 2001 from 70.4 and 76.4 years to 76.3 and 81.1, for males and females, respectively, but these increases were not consistent for all regions of the country, and in some (more socially deprived) places, mortality rates actually grew (Pearce et al, 2006; Pearce, Tisch and Barnett, 2008). Regional inequalities in life expectancy in New Zealand increased by approximately 50 percent over this period (Pearce and Dorling, 2006), during a phase of rapid social and economic change in New Zealand society (Le Heron and Pawson, 1996).

There has been considerable attention given to unravelling the processes that establish and perpetuate geographical inequalities in health, and to include explanations relating to the characteristics of the people living in the areas (eg, age, sex, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity) but also features of the places themselves (eg, local resources and health services, area deprivation, and environmental disamenities such as air pollution). One potential driver of spatial inequalities in health is the process of health selective migration (Anderson, Ferris and Zickmantel, 1964; Kelsey, Mood and Acheson, 1968; Bentham, 1988). Research into health selective migration has considered whether “healthy” or “unhealthy” people have a greater or lesser propensity to move residence, as well as the implications of such movements for changing patterns in area-level health inequalities. If a sorting process occurs in which people in better health are more likely to move to (or remain in) less deprived areas, and those in poorer health are more likely to move into (or remain in) more deprived areas, then spatial inequalities in health will be exacerbated. Although the potential significance of selective migration effects for geographical studies has long been recognized (Anderson, Ferris and Zickmantel, 1964; Fox and Goldblatt, 1982), only recently have researchers attempted to quantify the effects of these processes on spatial inequalities in health. The health inequalities literature has not tended to examine selective mobility proactively as a partial account for the geographical patterning in health status and health-related behaviours. At best, health-related migration and mobility has been considered as a statistical artefact rather than a substantive area of academic enquiry (Smith and Easterlow, 2005).

Research in Great Britain has tended to demonstrate that selective migration and immobility has strengthened the relationship between area deprivation and various health outcomes including mortality (Brimblecombe, Dorling and Shaw, 1999; Norman, Boyle and Rees, 2005; Connolly, O’Reilly and Rosato, 2007), Type 2 diabetes (Cox et al, 2007), and ischemic heart disease (Strachan, Leon and Dodgeon, 1995). For example, an examination of 10,264 British residents enumerated as part of the British Household Panel Survey in 1991 found that at the local (district) scale the major geographical variations in age- and sex-standardized mortality could be attributed to selective migration (Brimblecombe, Dorling and Shaw, 1999). This effect was particularly pronounced among men. Similarly, using longitudinal data in England and Wales over a twenty-year period (1971–1991), Norman, Boyle and Rees (2005) found that the migrants who move from more to less deprived areas are significantly healthier than migrants who move from less to more deprived areas, and that the largest absolute flow was by relatively healthy migrants moving away from more deprived areas toward less deprived areas.

The results from studies of selective migration effects outside of Great Britain are more mixed. The findings of research in Australia (Larson, Bell and Young, 2004) and the United States (Landale, Gorman and Oropesa, 2006) concur with the British work and suggest that differential migration patterns between healthy and unhealthy groups are a key explanation in understanding the varying health outcomes in the providing and receiving areas. On the other hand, research in the Netherlands, Northern Ireland, and Norway demonstrates that selective migration patterns have had little, if any, effect on neighbourhood (Dalgard and Tambs, 1997; Connolly and O’Reilly, 2007; van Lenthe, Martikainen and Mackenbach, 2007), or urban– rural (Verheij et al, 1998) inequalities in health.

For example, van Lenthe, Martikainen and Mackenbach (2007) studied individuals aged twenty-five to seventy-four living in the city of Eindhoven in the Netherlands and found that after adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics at the individual level, selective migration made a negligible contribution to neighbourhood inequalities in health and health-related behaviours within the city; however, although 27,070 people were targeted to participate in this study, 30 percent of those approached refused to participate, and a further 45 percent of respondents were excluded because they did not reside within the city limits. The exclusion of this group seems surprising given that it has been established that the migration patterns between urban and rural areas tend to be selective. Further, respondents younger than twenty-five, and those who moved but whose location was unknown, were also excluded. Therefore, the study design might have minimized any measurable effects of selective migration patterns.

A study in Northern Ireland for the period 2000 to 2005 found that although there was evidence of significant variations in health between migrants and non-migrants, this differential had no impact on neighbourhood inequalities in health, partly because migrants out of deprived areas had a similar health status to the replacement in-migrants (Connolly and O’Reilly, 2007); however, the study period was a particularly unusual period of change in the recent history of Northern Ireland. Other than the former Yugoslavia and Cyprus, there are few other European examples where residential migration has been more disrupted by violence in the last three decades. Until recently, few people from affluent areas of the United Kingdom would consider moving even to prosperous areas of Northern Ireland and outmigration flows were high from many parts of Northern Ireland, not simply the poorest places (Dorling and Thomas, 2004). The unusual circumstances in Northern Ireland might have hindered the general patterns of differential migration that are evident in most OECD countries.2

Migration effects

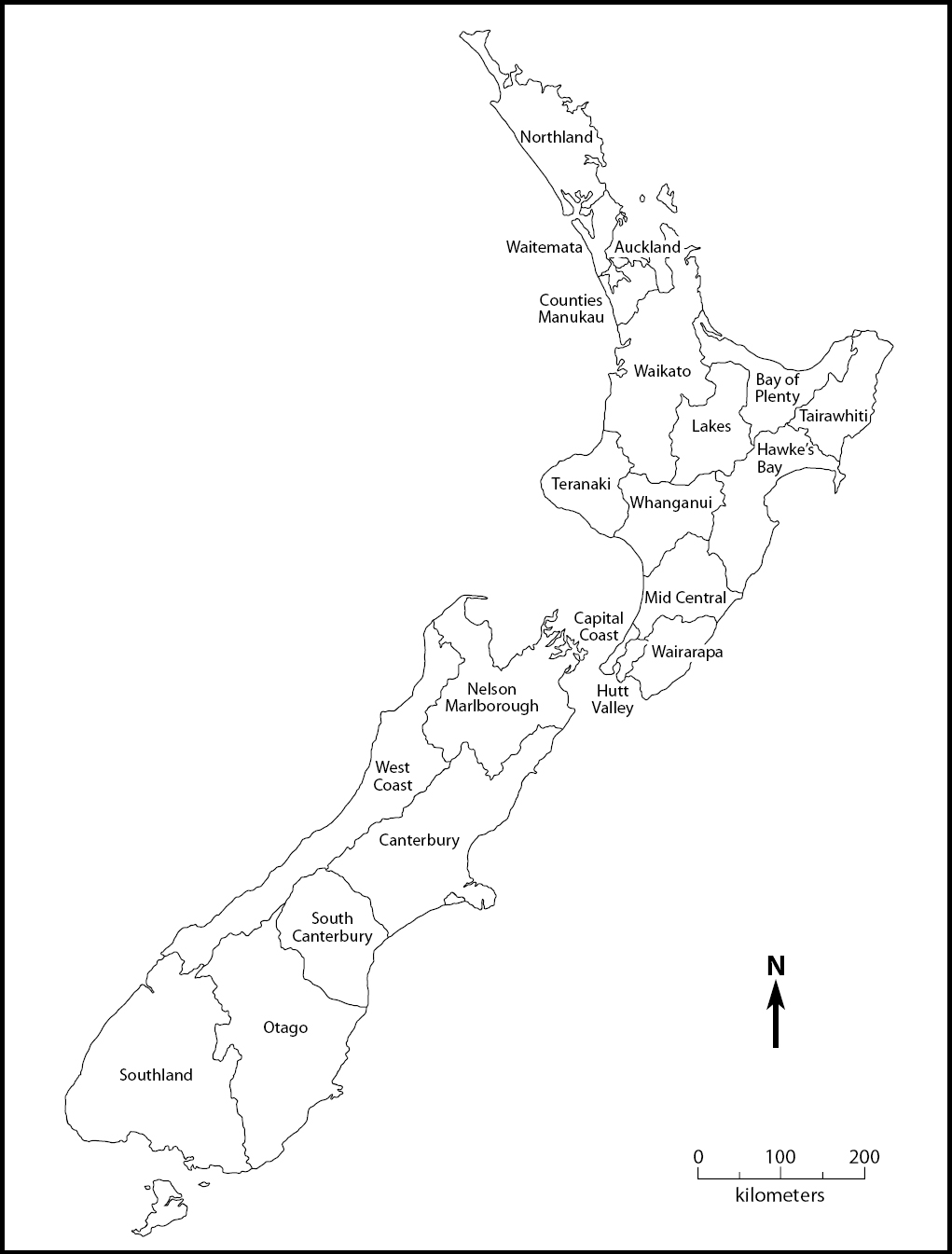

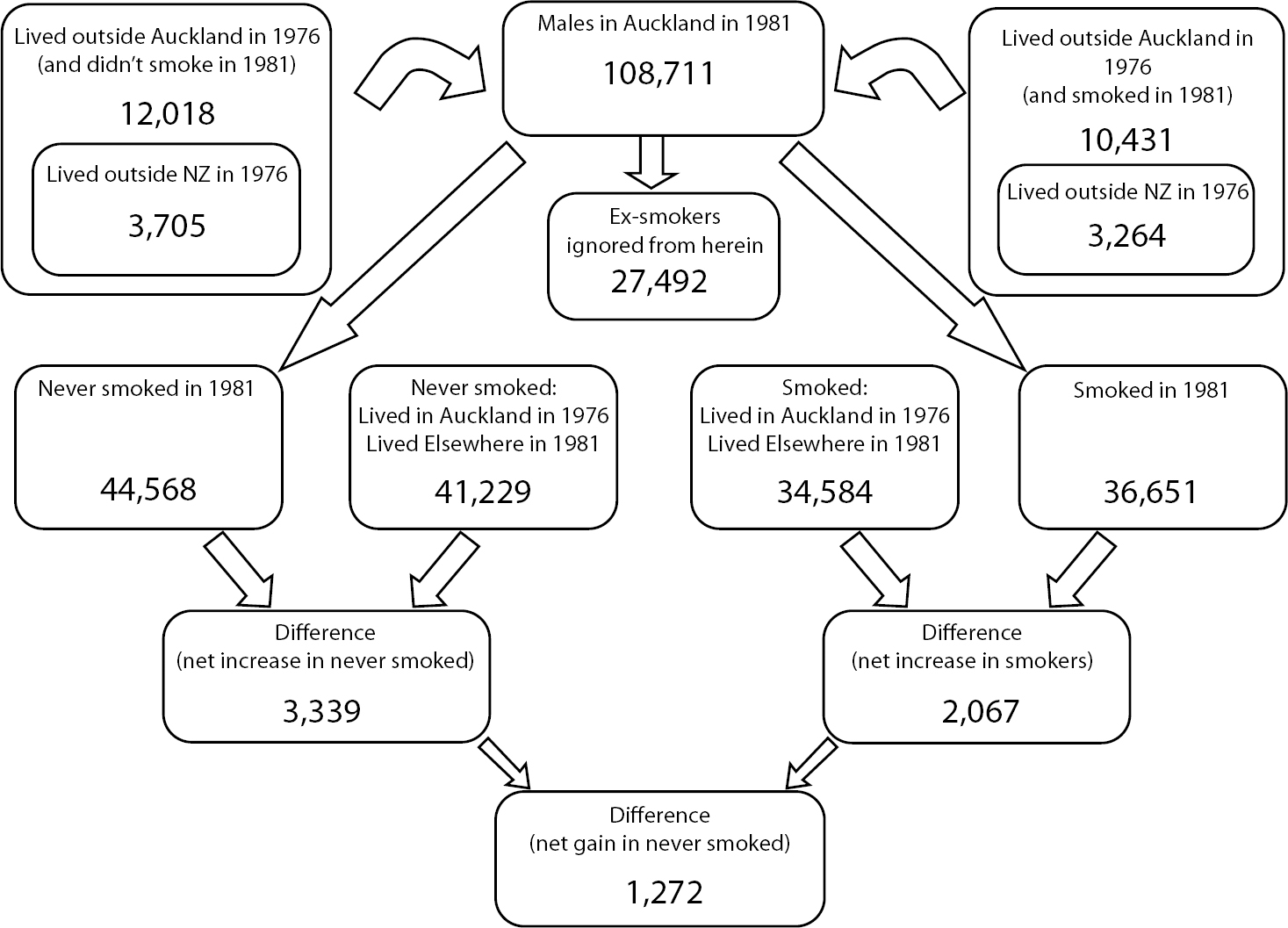

Demographic accounting was undertaken to first ascertain the net movement of smokers into each area due to internal migration within New Zealand. To determine the overall migration balance it was necessary to examine the movement of both smokers and nonsmokers into and out of each District Health Board (DHB, see Figure 1 for their boundaries). The methodology is best described by using an example (see Figure 2 for an outline of the methods). If more male smokers came to Auckland than left Auckland, then all else being equal, we would expect males living in Auckland to report worse health over time. In 1981, there were 108,711 males (aged fifteen and older) living in the Auckland DHB. Of these, 36,651 were smokers, and of this total 10,431 were living outside of Auckland five years previously (and of these migrant smokers, 3,264 had migrated into New Zealand during that period). Therefore, in 1981 just over one third of the males in the Auckland DHB were smokers; a third of male smokers had arrived in the Auckland DHB within the previous five years; and of this group of migrant male smokers, one third were new (past five years) arrivals into New Zealand. In addition, it is possible to calculate that a further 34,584 male smokers who had lived in Auckland in 1976 were living elsewhere in New Zealand by 1981. However, we cannot ascertain how many had left Auckland to live overseas, as these data are not collected. Therefore, ignoring emigrants, there were 2,067 (36,651 – 34,584) more smokers in Auckland in 1981 than in 1976.

Although there were more male smokers in Auckland in 1981 than in 1976, it does not necessarily follow that a higher proportion of males in the Auckland DHB were smokers in 1981 than 1976 because the overall population of the city grew over this period (and people who do not move might alter their smoking behaviour). To determine whether the overall migration balance of smokers and nonsmokers was positive or negative we must also consider the movements of those who have never smoked.

From the 1981 census we can calculate that of the 108,711 males living in the Auckland DHB, 44,568 never smoked, and of those some 12,018 had been living outside of Auckland DHB five years previously (and of these 3,705 migrated to New Zealand during this period). Therefore, in 1981 41 percent of males in Auckland had never smoked, of whom 27 percent had moved into the city, in turn of whom 31 percent had arrived into the country. Some 41,229 men who had never smoked and lived in Auckland in 1976 now lived elsewhere. So the balance of never-smokers to Auckland by 1981 was 3,339 (44,568 − 41,229). Again we have to ignore emigrants. If we consider the overall change in the balance of smokers that can be attributed to selective migration patterns during the period from 1976 to 1981 in the Auckland DHB, then we find that there was a net gain of 2,067 smokers and 3,339 never-smokers, which resulted in a 1,272 net gain in never-smokers in 1981 compared to 1976. This figure represents 1.2 percent of the male population of the Auckland DHB. These calculations were completed for males and females in all DHBs across the country for each time period for which smoking data were collected (1981, 1996, and 2006). To investigate the potentially different influences of internal and international migration on the smoking balance, the analyses were repeated with immigrants excluded from the calculations3.

Figure 1: District health boards across New Zealand (2006)

Figure 2: Flowchart depicting the methods used to calculate the smoking migration balance in the Auckland district health board (1981)

Conclusion

This study has investigated the complex nature of migration streams to exemplify how geographical inequalities in health across regions of New Zealand are significantly influenced by the health (in this case smoking status) of the population entering and leaving each area. The results add to the international evidence that selective migration is an important process in explaining regional inequalities in health. It is important that future studies of spatial inequalities in health account for the potentially important effect of selective mobility that might otherwise lead to interpretations of ecological associations and area effects that are, in fact, artifactual. Accounting for the selective mobilities of people with varying health outcomes, needs, and experiences is an important domain for future research endeavour. Augmenting the understanding of health and mobility provides a considerable opportunity to enhance the appreciation of geographical processes in explaining and addressing inequalities in health.