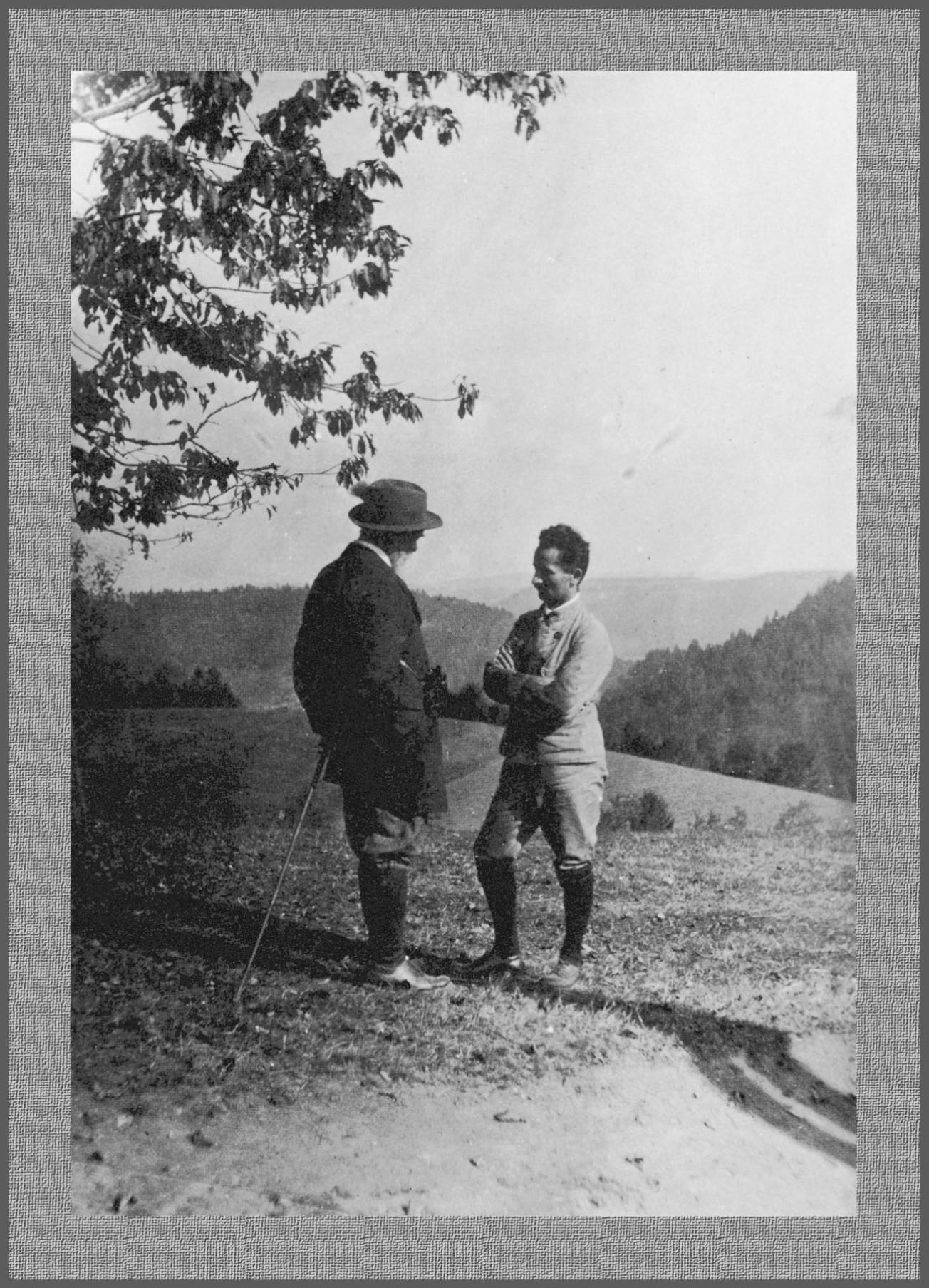

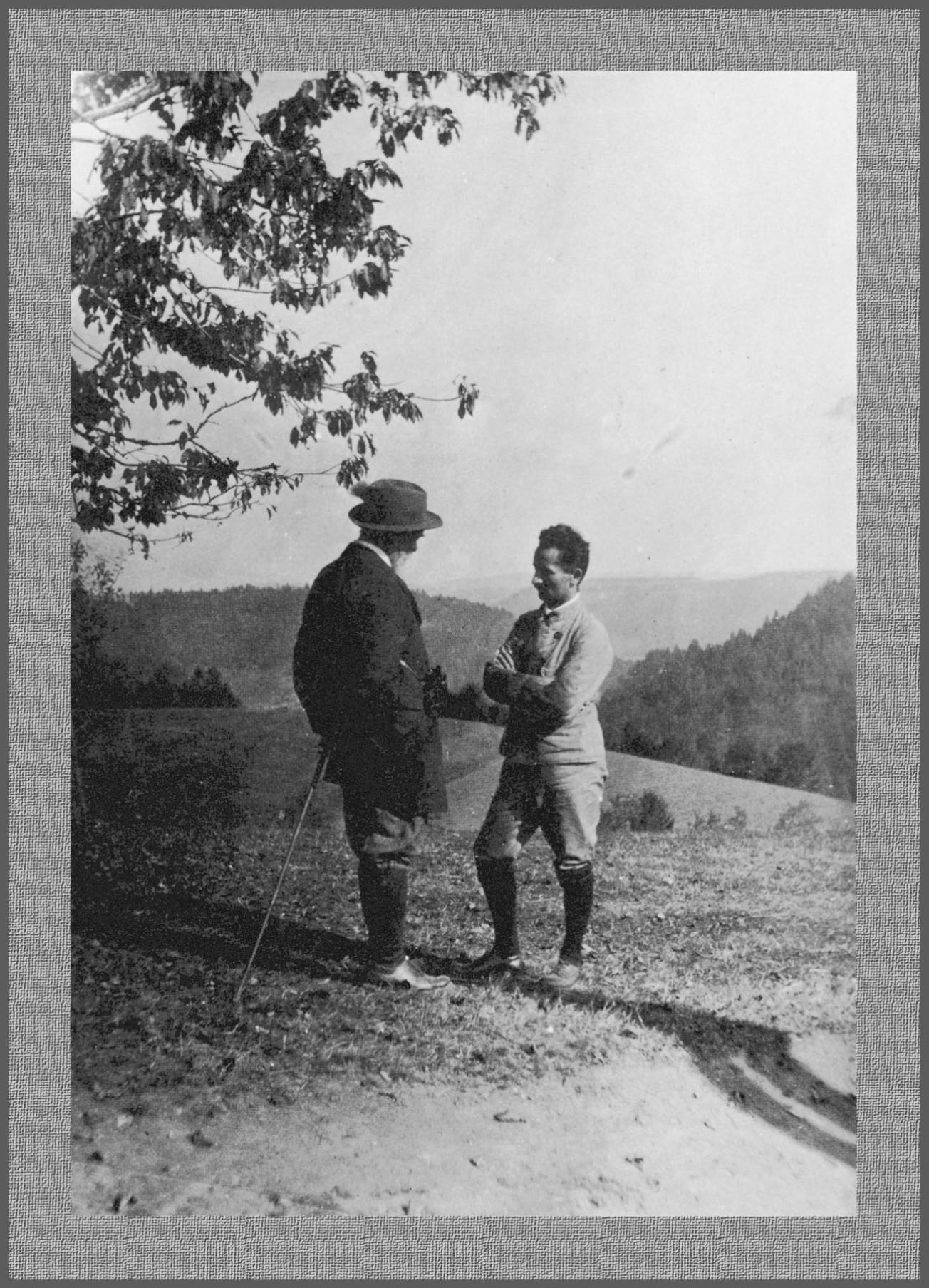

FIG. 6. Husserl und Heidegger 1921. Photo courtesy of J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart, 1986.

Being and Time: A Failed Masterpiece?

Antimodernism and “New Life”

FOR MANY YEARS, Heidegger’s great work of 1927 has been enveloped in myth—a myth of purity carefully cultivated by the Master himself. According to this legend, Being and Time, a work of unequivocal genius, emerged virtually ex nihilo. In Heidegger’s view, when questions of philosophical substance are at issue, scholarly influences or considerations of intellectual biography are beside the point. He once famously began a lecture course on Aristotle by observing, “He was born, he worked, he died”; the first and third terms of this sequence were, he intimated, irrelevant for an understanding of Aristotle’s importance as a thinker. As Heidegger once explained to a friend, “My life is entirely uninteresting.”1 Heidegger wished instead to be judged solely on the basis of his work—admittedly, a very strange stance for the man who coined the term “thrownness” (Geworfenheit) to describe the fundamentally contingent, non-self-generated character of human Being-in-the-world; the man who in Being and Time avowed that the enterprise of fundamental ontology unavoidably derived from the existential basis of his own individual standpoint.2 As Theodore Kisiel has formulated this problem: Heidegger’s apparent indifference to autobiography “flies in the face of the most unique features of Heidegger’s own philosophy, both in theory and in practice. For Heidegger himself resorted at times to philosophical biography by applying his own ‘hermeneutics of facticity’ to himself, to his situation, to what he himself called his ‘hermeneutic situation,’ precisely in order to clarify and advance his own thought.”3

FIG. 6. Husserl und Heidegger 1921. Photo courtesy of J. B. Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung and Carl Ernst Poeschel Verlag, Stuttgart, 1986.

As Heidegger legend has it, between 1915 and 1927 the Freiburg sage published nothing. Finally, at the end of this twelve-year period of authorial abstinence, Heidegger’s magnum opus miraculously emerged. This bit of received wisdom was famously codified in Heidegger’s (fictionalized) “Dialogue Between a Japanese and an Inquirer,” in which the Japanese’s tentative observation, “And so you remained silent for twelve years,” remains uncorrected by the “inquirer” (Heidegger himself).4 This studied neglect of the circumstantial aspects of Heidegger’s philosophy (a practice perpetuated by the editors of Heidegger’s Gesamtausgabe, who, following the Master’s wishes, have systematically refused to provide a critical apparatus for the edition) has made a systematic reconstruction of Heidegger’s early philosophical project—its Enstehungsgeschichte—a challenging enterprise. Only in the last few years, with the appearance of Heidegger’s early Freiburg lecture courses (1919–1923), has the situation begun to change significantly. On the basis of their publication, one can reproduce a semester-by-semester account of the intellectual path that culminated in Being and Time.5

Of course, even Heidegger himself was forced to avow that his life was not entirely uninteresting. Thus, throughout his life he selectively divulged useful biographical tidbits—albeit, often in a self-serving manner. In “My Way to Phenomenology” (1963) he tells the story of how, as an eighteen-year-old theology student, Franz Brentano’s dissertation on The Manifold Sense of Being in Aristotle served as his initiation into the mysteries of philosophy. The question that aroused the young gymnasium student’s interest was: “If being is predicated in manifold meanings, then what is its leading fundamental meaning? What does Being mean?”6 It was at this point that Heidegger’s basic philosophical question, the Seinsfrage or the “question of Being,” was established.

Two years later (1909–10), Heidegger discovered Edmund Husserl’s classic study, Logical Investigations, a book that remained checked out to his library carrel for the ensuing two years. Of particular value for Heidegger was Husserl’s powerful refutation of psychologism: the doctrine that the workings of the human mind can be understood exclusively in physicalist terms. From the standpoint of a young theology student interested in the way that thought and language are grounded ontologically in the word of God, such scientistic pretensions were both arrogant and sacrilegious. The task of theology, with the auxiliary aid of philosophy and logic, was to ensure that scientific hubris became conscious of its own limitations. In Logical Investigations, Husserl, following the lead of Brentano, established the difference between the psychological and logical aspects of judgment. Whereas the former were relative and contingent, varying from individual to individual, the latter, he claimed, possessed timeless validity. The truth value of a syllogism, argued Husserl, is independent of the psychological factors and mechanisms whereby it is realized. At a time when philosophy’s claims to autonomy were seriously under assault by the methods of the natural sciences, Husserl’s idea of “phenomenology as rigorous science” (the title of the philosopher’s celebrated 1909 Logos essay) played a crucial role in shoring up Heidegger’s own youthful intellectual inclinations and intuitions. In 1916, Husserl left Göttingen for an appointment at Freiburg. Heidegger would serve as his assistant for four years (1919–1923).

Much has been made of Heidegger’s Catholicism—his strict Catholic upbringing in provincial Messkirch (his father was the sexton at the local church), his seminary studies, his failed attempt to become a Jesuit circa 1915 (after three weeks of study, Heidegger was dismissed for reasons of health), and, finally, his painful break with the “religion of [his] youth” in 1917. Until recently, however, few have known how profoundly the twenty-year-old Heidegger was involved in the landmark debates over “modernism” (der Modernismusstreit) that rocked turn-of-the-century Germany. Heidegger was fond of citing Hölderlin’s maxim, “As you began, so you shall remain.” Unsurprisingly, insight into his profound youthful attachment to Catholicism goes far toward explaining his mature worldview.

Two years following German unification in 1871, Bismarck attempted to enforce Catholic allegiance to the new state via a series of compulsory and repressive mandates. The voluble Kulturkampf that resulted left wounds that would only heal very slowly. (Ironically, in the course of their struggle, German Catholics gained the support of many liberals who supported the principles of freedom of worship and conscience.) As Heidegger came of age circa 1910, Catholic mistrust of the German state remained keen; yet by then such mistrust had metamorphosed to an aversion to all aspects of modern society that threatened to bypass the values of religion and tradition. The historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler felicitously described Catholic immobilism during the Second Empire in the following terms:

In the 1864 Syllabus of Errors, an index of eighty “errors of the time,” orthodox Catholicism ranged itself implacably against liberalism, socialism and modern science. The call for increased ecclesiastical control of education and research reached totalitarian proportions…. The contempt felt by [the Roman Catholic Church] for the Protestant principle of toleration made coexistence with rival organizations or educational claims very difficult. Without doubt, Thomist neo-scholasticism, encouraged in its development by several popes since the mid-nineteenth century, also reinforced the anti-modernist character of Roman Catholicism at this time. This batch of theorems was opposed to the social mobility of the modern age and its notions of parliamentary representation and democratic equality. It cemented the backward-looking traditions of Catholicism and turned the values of a vanished world based on estates into an ideology. It sought to tie the nineteenth century into the strait-jacket of the medieval order while the tide of history moved in the opposite direction. Catholicism was even less likely than Protestantism to make an active and lasting contribution to the spread of parliamentary influence in Germany, to say nothing of its eventual democratization.7

The extent to which Heidegger’s youthful outlook was permeated by such unyielding Catholic perspectives becomes clear if one peruses the eight articles he wrote for the conservative Catholic journal, Der Akademiker, during the years 1910–12. As his biographer Hugo Ott, who unearthed these early articles, observes: “What the Der Akademiker contributions display is their embeddedness in a closed system of the Catholic worldview from an integral, anti-modern perspective. Martin Heidegger carries the banner of ultraconservative Catholicism with intense seriousness and great enthusiasm in the fields of theology, philosophy, and ethics.”8 Once again, Heidegger’s highly selective approach to autobiographical themes enters the picture, insofar as he inexplicably omitted his Der Akademiker essays from the collected works edition of his writings.

Der Akademiker was founded in the spirit of Pope Pius X’s so-called “antimodernism” encyclical of 1907. In fact, the journal’s first issue contained a Preface by Pius X offering words of encouragement to his German followers in their struggle against modernist mores and values. At the time he composed these articles, Heidegger stood under the influence of the antimodernist theologian Carl Braig. (Braig allegedly coined the word “modernism.”) Heidegger acknowledged his profound intellectual debt to Braig nearly fifty years later when, in Zur Sache des Denkens, he praised Braig’s “penetrating kind of thinking.”9 In his own highly polemical writings, Braig railed against a modernism that was “blinded to anything that is not its Self or that does not serve its Self.” “Historical truth,” Braig continues, “like all truth—and the most brilliantly victorious is mathematical truth, the strictest form of eternal truth—is prior to the subjective ego and exists without it…. As soon as the ego of reason regards the reasonableness of things, they are not in truth…. No Kant will change the law that commands man to act in accordance with the way things are.”10

What Heidegger’s own contributions to Der Akademiker may have lacked in originality, they made up for in polemical zeal. For example, in his very first article (“Per Mortem ad Vitem”), he attacks, in the spirit of Pius X and Carl Braig, the modernist fascination with the vagaries of subjectivity:

In our day, one talks much about “personality.” And philosophers find new value-concepts. Apart from critical, moral, and aesthetic evaluation, they operate also with the “evaluation of personality,” especially in literature. The person of the artist moves into the foreground. Thus one hears much about interesting people. Oscar Wilde, the dandy; Paul Verlaine, the “brilliant drunkard”; Maxim Gorky, the great vagabond; the superman Nietzsche—all interesting people. And when one of these interesting people, in the hour of grace, becomes conscious of the great lie of his gypsy-life [sic], smashes the altars of false gods, and becomes Christian, then they call this “tasteless, revolting.”11

To Ibsen, Heidegger attributes the view that, “Happiness is possible only through a life of deceit.” He goes on to inquire, Do the great personalities we have mentioned find happiness? No, they find only death and despair insofar as “none of them had the truth.” All remained wedded to “individualism,” which is, Heidegger proclaims, a “false standard of life.” Higher life, he continues, will only triumph if lower forms of life are destroyed: “the will of the flesh, the doctrine of the world, paganism.” Heidegger’s impassioned conclusion is that:

The much-ballyhooed cult of personality can only flourish when it remains in intimate contact with the richest and deepest source of religio-ethical authority. This cannot, according to its nature, do without a venerable outer form. And the church will, if is to remain true to its eternal treasure of truth, justifiably combat the destructive influences of modernism, which is not conscious of the sharpest contradictions in which its modern views of life stand to the ancient wisdom of the Christian tradition.12

Yet Heidegger’s critique of the modern apotheosis of self remains unmarred by anti-intellectualism. He always justifies his standpoint in the name of logic, rigor, and a more exalted conception of “truth”—one that has been ignored by the (frivolous) modern glorification of subjective experience. Accordingly, he takes modern thought to task for its lax subjectivism, its having made perplexity and disorientation into a positive value. “Today,” Heidegger laments, “philosophy, a mirror of eternity, only reflects subjective opinions, personal moods and wishes.” In opposition to the amorphous tendencies of the modern self, Heidegger recommends “a strict, ice-cold logic [that] is inimical to the refined feelings of the modern soul. To strictly logical thought, which hermetically seals itself off against any affective influence of the soul, to each truly presuppositionless scientific work, there belongs a certain base of ethical power.”13

What is striking about these claims is the extent to which they anticipate Heidegger’s mature positions and views. It is clear that Heidegger’s lifelong ontological quest, centering on the question of Being, was first catalyzed in response to the disorienting pluralism and relativism of cultural modernity. His aversion to modern epistemology (the legacy of Descartes), beginning with Being and Time and culminating in the Nietzsche lectures of the 1930s, can in part be traced to the critique of modern thought articulated in these early writings. His pronounced disaffection with modern art and literature—in the 1966 Der Spiegel interview, Heidegger characterizes aesthetic modernism as essentially “destructive”—unambiguously originated in the mentalité of Kulturkampf.14 His semi-hysterical image of America as a relentless technological Moloch, as “the site of catastrophe,” develops from attitudes and convictions first expressed in the Der Akademiker texts.15 Finally, one may also trace Heidegger’s attraction to National Socialism as a “primordial” political phenomenon capable of redeeming Germany from the lacerations and divisions of modern “society” to the resolutely anti-modernist standpoint articulated in these early articles.16 As early as 1924 Heidegger publicly declared the need to place “our German Dasein on firm foundations.”

Heidegger always insisted that the orientation of fundamental ontology derived from the domain of “factical” experience, from the domain of “life” in its sheer immediacy. In Being and Time, he goes so far as to invoke a determinate “factical ideal of Dasein that underlies the on-tological interpretation of Dasein’s existence”; in other words, “facticity,” the domain of immediate experience, remains prior to first philosophy.17 And in a revealing letter to Karl Löwith in the early 1920s, Heidegger insists that his philosophizing derives from the “facticity” or existential immediacy of his own Being-in-the-world: “I work in a concretely factical manner, from out of my ‘I am—from out of my spiritual, indeed factical heritage/milieu/life contexts, from out of that which thereby becomes accessible to me as the living experience in which I live.’”18 All of these declarations indicate that the circumstantial aspects of Heidegger’s thought, far from being epiphenomenal or tangential, are of fundamental significance to understanding his philosophy.

Further insight into the autobiographical components of the “factical ideal” underlying Heidegger’s philosophy is provided by his recently published correspondence with Elisabeth Blochmann. Blochmann, who was half-Jewish, was originally a friend of Heidegger’s wife, Elfride. She had studied philosophy with Georg Simmel in Strasbourg and frequented Youth Movement circles in which Lebensphilosophie (Nietzsche, Simmel, Dilthey) was fashionable.

Though their correspondence hints at the fact that Heidegger and Blochmann were more than friends (Heidegger was frequently inspired to uncharacteristic bursts of lyricism), tangible proof as to the precise nature of their relationship is lacking. Their exchanges began during the concluding months of World War I, a period of national despair. It was a time suited for radical questioning: the nostrums and rationalizations of prewar life and thought seemed patently inadequate. In Heidegger’s view, the war had decimated everything except for the “force of personality or belief in the intrinsic value or belonging central to the ego”—a claim that betrays the marked influence of Husserl’s transcendental phenomenology.19 If any one book felicitously captured the Zeitgeist, it was Spengler’s Decline of the West, and a confrontation with Spengler soon became a mandatory rite of passage for right-leaning German intellectuals. Although he regarded Spengler’s historical typologies as ultimately superficial, Heidegger’s own obsession with the imperatives of “destroying” and “destruction” (destruieren, Abbau)—a veritable leitmotif during this period—harmonized perfectly with the postwar cultural Stimmung.20

In the correspondence with Blochmann, the young Privatdozent bares his soul. As Heidegger writes in an impassioned letter of June 15, 1918:

Spiritual life must again become truly real with us—it must be endowed with a force born of personality, a force that “overturns” and compels genuine rising—and this force is revealed as a genuine one only in simplicity, not in the blasé, decadent, enforced…. Spiritual life can only be demonstrated and shaped in such a way that those who are to share in it are directly gripped by it in their most personal existence…. Where belief in the intrinsic value of self-identification is truly alive, there everything that is unworthy in accidental surroundings is overcome from within and forever.21

Heidegger perceived the war as a great purgative out of which a new Germany might emerge. From a spiritual perspective, defeat on the battlefield would not constitute an irreversible setback; instead, it would serve to purify German culture of all that was artificial, tentative, and nonessential. It was the great acid bath out of which a deeper and more profound Germany would appear. A elemental Christian motif, reinterpreted through the prism of German romanticism and the war experience itself, underlay Heidegger’s perceptions: from death and destruction, “new life” would be born. As he observes to Blochmann in his letter of January 1919: “The new life that we desire, or that desires us, has dispensed with being universal, i.e. being false and two-dimensional (superficial)—its asset is originality—not the artificially constructed, but the evident content of total intuition.”22 In keeping with his self-understanding as part of a new German spiritual elite, he described the war’s “positive effects” in the following terms: “inwardly impoverished aesthetes and people who until now, as ‘spiritual’ people, have merely played with spirit the way others play with money and pleasure, will now collapse and despair helplessly—hardly any help or useful directives can be expected from them.”23

The reference to “total intuition” highlights the new, nonuniversal approach to knowledge Heidegger saw emerging from the phenomenological method. The key intellectual discovery for him during this period was the nearly untranslatable notion of Jeweiligkeit, a concept that figured prominently in Being and Time: the incomparable uniqueness of the spatio-temporal present and the related question of how one might represent it through concepts. Heidegger’s essential breakthrough to a new concept of temporality was contained in this idea. Traditional metaphysics strove to represent truth sub specie aeternae—that is, as something “universal”—to the detriment of the temporality and historicity of lived experience. By foregrounding the question of time, Heidegger sought to reverse this prejudice; subsequently, the appearance of Being in time, the uniqueness of the moment of its appearance (Kairos, der Augenblick), would occupy center stage in his thought. It was in this spirit that he chose as the epigraph for his post-habilitation trial lecture a saying from Meister Eckhart: “Time is that which changes and pluralizes itself; eternity remains simple.”24 The universalizing tendencies of traditional ontology remained indifferent to such concerns, and, hence, to experience as something meaningful, that is, as something lived. In a similar vein, in his habilitation study of the medieval philosopher Duns Scotus, Heidegger observed that, “What really exists is something individual [ein Individuelles].”25 Only a radically transformed conception of temporality could resolve the dilemma of the philosophical concept’s constitutional indifference to the singularity of experience.

From the very beginning, Heidegger’s renewal of metaphysics was conceived of as part of an all-encompassing project of cultural and political renewal. In his first lecture course following World War I, On the Vocation of Philosophy, he announced prophetically: “The idea of science—and its genuine realization—signifies for the immediate consciousness of life a transformative intervention (however this may be conceived); it entails a change to a new attitude of consciousness and thereby a corresponding form of the movement of the life of spirit.” He supplements the foregoing observations by declaring: “Every great philosophy fulfills itself in a worldview.” In other words, unlike German idealism, genuine science does not leave the world around it unaffected.26

The Break with Catholicism

In 1917, Heidegger experienced a profound personal and religious crisis, an increasing sense of alienation from the religion of his youth. So momentous was this confessional parting-of-the-ways that Heidegger biographer Hugo Ott refers to it as “the first turn.” Throughout his boyhood, Heidegger was dependent on the largesse of the Catholic Church in order to finance his studies; but this dependency bred resentment, insofar as the fellowships he received often came with strings attached. For example, following his dissertation on “The Doctrine of Judgment in Psychologism” (1911), Heidegger sought to continue his studies of phenomenology and logic. Yet, upon receiving a stipend from the Foundation in Honor of St. Thomas Aquinas, he was forced to devote his energies primarily to the study of scholasticism.

In 1916, Heidegger and Elfride Petrie were betrothed. They were married the following year. Elfride came from a staunchly Protestant background. For Heidegger, the engagement seems to have crystallized a process of confessional disillusionment that had played itself out during the previous years. Heidegger’s father had been a sexton at the local church in Messkirch. For a period of thirteen years, his education had been generously funded by Catholic organizations and institutions. For these and other reasons, it would be difficult to overestimate the biographical significance of his formal break with Catholicism at the time of his engagement to Elfride.

Revealing testimony concerning this break was contained in the letter Heidegger wrote to one of his mentors, Freiburg University theology professor and priest Engelbert Krebs, in January 1919. As Heidegger avows:

Over the last two years I have set aside all scientific work of a specialized nature and have struggled instead for a basic clarification of my philosophical position. This has led me to results that I could not be free to hold and teach if I were tied to positions that come from outside of philosophy.

Epistemological insights that pass over into the theory of historical knowledge have made the system of Catholicism problematic and unacceptable to me—but not Christianity and metaphysics, although I take the latter in a new sense.27

Heidegger’s letter indicates both the constraints he felt as a philosopher working within the strictures of Catholic theology and the expectation that, given this new freedom of research, he would be able to reconcile the demands of Christianity and metaphysics. Of equal importance, however, is his allusion to the “epistemological insights” of German historicism. Since completing his habilitation study on Duns Scotus, Heidegger had begun an intensive study of Dilthey, whose work had elevated the idea of “historical knowledge” to the status of a first principle of the human sciences. Dilthey’s notion of “historicity,” which would become one of the central categories of Being and Time, reinforced Heidegger’s sense of the failings of traditional ontology—its aversion to temporality, its inordinate focus on “universality” and “eternity” at the expense of the singularity of the here and now. The idea of historicity helped drive home the notion of the irreducible uniqueness of events occurring in time.

As his alienation from Catholicism accelerated circa the mid-1910s, Heidegger undertook a confrontation with the essential texts of Protestant theology: the works of Augustine, Luther, Schleiermacher, and Kierkegaard. Yet he was less interested in the explicitly religious content of their thought than in its phenomenological aspects and significance—religious consciousness as a manifestation of intentional experience.28 Thus, he was less interested in Christianity as a vehicle of religious experience than in its status as a paradigm of experience sim-pliciter: the phenomenological deepening of the self concomitant with the personal experience of faith, the cultivation of the inner self (Innewerden), the advent of “self-consciousness” in the sense of German Pietism later appropriated by Hegel. In his 1920 lecture course, “Introduction to the Phenomenology of Religion,” in which Heidegger broaches many of these themes, he coins the term “Self-world” to describe the realm he is seeking.

Thus, in Heidegger’s view, the classic texts of the Protestantism offered privileged insight into the irreducibly singular nature of an individual’s encounter with God qua lived experience—experience that, as a result of Rome’s neo-Thomist and ecclesiastical biases, seemed of lesser significance in Catholic traditions. As Heidegger himself laments circa 1916 with scholasticism in mind: “Dogmatic and casuistic pseudo-philosophies, which pose as philosophies of a particular system of religion (for example, Catholicism) and presumably stand closest to religion and the religious, are the least capable of promoting the vitality of the problem.” Insofar as scholasticism, following the mistaken lead of Aristotle, attempted to take its bearings from the natural world rather than the domain of inner life, it “severely jeopardized the immediacy of religious life and forgot religion for theology and dogmas.”29 From the phenomenological standpoint revered by the early Heidegger, scholastic ontology stood in urgent need of “dismantling.” He believed that the phenomenological method alone could retrieve the experiential substrate in its primordial immediacy—a substrate that, throughout the history of metaphysics, had been repressed and distorted by the imposition of an alien ontology. In this way, Heidegger inquired into the primordial phenomenological relationship between self and world. In the words of one commentator: “On the threshold of his religious crisis of 1917, we find Heidegger already keenly interested in the phenomenology of religion, looking to it for insight into the notion of intentionality … as a vehicle for bringing a fossilized philosophy back to life.”30

Encountering Phenomenology

“Phenomenology: that’s Heidegger and me”—this was Husserl’s succinct characterization of the movement during the early 1920s, a glowing endorsement of Heidegger as his handpicked successor. His prophecy was borne out in 1928 when Heidegger acceded to Husserl’s chair at Freiburg. In the early 1920s, students arrived intending to study with Husserl and within weeks would switch to auditing Heidegger’s lectures and seminars. At times, Husserl himself encouraged them to make the shift. In her encomium written on the occasion of Heidegger’s eightieth birthday, Hannah Arendt emphasizes the subterranean renown that Heidegger enjoyed among German university students well before the publication of Being and Time.31

In retrospective accounts of his philosophical path, Heidegger perennially downplayed the significance of his break with Husserl, insisting instead on the elements of continuity between his early career as a phenomenologist and his later status as a philosopher of Being. Yet, from the time of their earliest collaboration, cracks in the alliance were readily apparent. Husserl and Heidegger possessed fundamentally different conceptions of the mission of “science.” Whereas for Husserl phenomenology’s ultimate goal was to place philosophy on a rigorous objective footing (a longing for “apodeictic certainty” suffuses his early treatises on method), Heidegger, as we have seen, was motivated by a very different set of concerns. The celebration of “life” in its immediacy as an independent value and normative point of departure—an orientation that was central to Lebensphilosophie—was entirely foreign to Husserl’s approach. Although Heidegger had distinct methodological reservations about vitalism, he remained in solidarity with many of its critical aims. As he remarked in 1919: “Today the word ‘lived experience’ [Erlebnis] is so hackneyed and colorless that one would do best to leave it to one side were it not so directly central.”32 Paradoxical though it may seem, in their assessments of the great intellectual divide between rationalism and antirationalism, Husserl and Heidegger ultimately lay on opposite sides. Heidegger increasingly came to view Husserl’s emphasis on the nonsituated, transcendental ego as a type of phenomenological fundamentum inconcussum as an unacceptable methodological failing. In Heidegger’s view, it was Descartes’s res cogitans outfitted in phenomenological garb. Husserl understood phenomenology as a scientific redemption of the Enlightenment project that, while avoiding all taint of physicalism and materialism, remained true to the mission of first philosophy. As he remarked in a letter of 1935: “I want to establish, against mysticism and irrationalism, a kind of superrationalism which transcends the old rationalism as inadequate and yet vindicates its inmost objectives.”33 The phenomenological intuition of essences (Wesensschau) would accomplish this end, thus avoiding a regression to the unverifiable conjectures of traditional metaphysics. Correspondingly, transcendental phenomenology embraced the modern scientific values of clarity, light, and reason. Or, as Husserl once declared: “Only one need absorbs me: I must win clarity, else I cannot live; I cannot bear life unless I can believe that I shall achieve it.”34 Heidegger, conversely, in his search for unfathomable depths of primordial experience, remained convinced that truths yielded by analytical reason were shallow and of little import. As a modality of lived experience, “judging” is a species of “un-living,” polemicizes Heidegger. “The object-character (das Gegenständliche), the thing that is known, is as such dis-tant (ent-fernt), cut off from authentic lived experience.”35

An anecdote from their early collaboration in Freiburg well illustrates the nature of their substantive differences. A student who was auditing classes with both men, but whose allegiances lay with Husserl, registered the following complaint: “Dr. Heidegger is taking a mediating position by asserting that the primal I is the qualified ‘historical I,’ from which the pure I is derived by repressing all historicity.”36 Therein lay their basic disagreement. Husserl assumed that the transcendental ego’s purity depended on its being purged of all historical factors and influences. Historical contingency only sullied the purity of the transcendental standpoint. On one occasion, he went so far as to characterize “the pure ego and pure consciousness” as “the wonder of all wonders.”37 In Formal and Transcendental Logic, he insisted that, “Whether we like it or not, whether it may sound monstrous or not, the “I am” is the fundamental fact to which I have to stand up, before which, as a philosopher, I must never blink for a moment.”38 Only late in life with The Crisis of the European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology (1936) would Husserl belatedly prove receptive to the demands of history. There he argued (with astonishing naiveté) that Europe can avoid the abyss of impending nihilism only if it is able to reestablish the telos of first philosophy, whose thread has been lost amid a rising tide of scientistic and vitalist intellectual currents. For Heidegger, conversely, the Self’s receptivity to historicity (or temporality) was one of its indispensable attributes. As Heidegger observed: “In the theoretical attitude I am directed to something, but I have no living involvement (as a historical I) with this or that thing in the world.”39 In this way fundamental ontology, with its focus on the embodied attributes of “care,” “mood,” “solicitude, and “falling,” would outstrip the transcendental “I” of Husserlian phenomenology.

A remarkable 1919 lecture course, On the Vocation of Philosophy, represents the germ of Heidegger’s unique approach to the problems of first philosophy. Reading it gives one the sense of being privy to a portentous moment of intellectual discovery. Heidegger composed the lecture course in the midst of an emergency situation (Notzustand)—the revolutionary tumult of postwar Germany—and the semester in which it was delivered was appropriately known as the “war emergency semester” (Kriegsnotsemester). Here, Heidegger is preoccupied with the question of beginnings: only after this question has been satisfactorily treated will the vocation of science rest on sure footing. The transcript reveals Heidegger groping for a moment of phenomenological clarity that will found his philosophical project. He proceeds with a methodical rigor that suggests that the future of humankind depends on this discovery. In Heidegger’s words: “We stand at a methodological crossroads where the life and death of philosophy is at stake; we stand before an abyss: either an abyss of nothingness, e.g., absolute objectivism (Sachlichkeit), or a successful leap into another world—or, more precisely, into the world for the first time.”40

As Heidegger remarked in a letter to Löwith from the same period, his philosophy is inspired by a search for the unum necessarum—the “one thing that is necessary”; this pursuit is what motivates him in both philosophy and “existence.” There is no way, he avowed, that the two can be separated. “I am not concerned,” remarked Heidegger, “with a primary and isolated definition of philosophy—but rather only with that kind of definition that is related to the existential interpretation of facticity.” In the letter, he returns to this point repeatedly:

I do not make a distinction between the scientific, theoretical life and one’s own life…. The essential manner in which my facticity becomes existentially articulated is scientific research…. In this connection, for me the motive and goal of philosophizing is never to augment the store of objective truths, because the objectivity of philosophy … lies within the meaning of my existing.41

From these brief characterizations and self-descriptions one can see that Heidegger is driven by a concern to refound transcendental phenomenology in a manner that foregrounds the dimension of “factical/existential” concern, or “life.” The problem, however, was that in its current employment, the idea of life (das Leben) had succumbed to the fashionable, pseudopopular terms of value-philosophies and world-views. One of Heidegger’s major scientific aims was finally to place the diffuse and superficial orientations of Lebensphilosophie on a rigorous phenomenological footing.

In the early 1920s, Heidegger undertook a phenomenological search for what he calls an “Ur-etwas,” a “primordial something.” The encounter with this dimension of experience would propel the enterprise of fundamental ontology. Heidegger makes it clear that what he is searching for has nothing to do with the “sense data” (Locke) or “sensory manifold” (Kant) of modern epistemology. Epistemology’s model of experience has always been scientific experience, a model that succumbs to the tyranny of the theoretical and thereby perpetrates the “de-living of life” (Ent-leben des Lebens).42 Before “life”—that “primordial something”—can be experienced, it is made into an object of scientific cognition. For Heidegger, this primordial experiential stratum, though pre-theoretical, is already meaningful. (The positing of an abstract epistemological subject standing against an abstract object is a scientific construction). Fundamental ontology, conversely, does not foist an alien conceptual framework upon life. It is not primarily concerned with acts of “cognition,” whereby experience is mechanically synthesized through concepts. Instead, it reads off meanings that are already there or experientially pregiven. At one point, Heidegger refers to his approach as “illuminating comportment,” seeking thereby to distinguish it from the claims of epistemology.43 Rather than proceeding by way of analysis and judgment, and thereby producing true propositions or statements (Feststellungen), fundamental ontology employs the method of “hermeneutical intuition.”44 Ultimately, this methodological breakthrough mandates a rejection of the Aristotelian primacy of logos (the rational account) in favor of the notion of aletheia—truth as a ontological chiaroscuro of “concealment” and “unconcealment.” Fundamental ontology’s “hermeneutical intuitions” (later: “formal indications”) do not “still the stream of experience” but disclose meanings that are already present. Experience itself, the primordial encounter between self and world, far from being mute, and as always already meaningful, already contains an expressive dimension: it cannot help but speak to us if we reacquire the capacity to heed its signals. As Heidegger observes in a lapidary aside: “Philosophy as fundamental knowing is nothing other than the radical actualization of the facticity of life in its historicity.”45

One of Heidegger’s crucial discoveries of this period, one that would set him on the path toward Being and Time, was the idea of “facticity” (Faktizität) or “factical life.” With this notion, he sought to identify (as earlier with the “primordial something”) an irreducible and original (ürsprünglich) dimension of experience prior to the subject-object split. When one inquires into the incipient nature of experience as exemplified by the phrase, “there is …” (es gibt), one probes a level of primordial givenness that is prior to the differentiation of the world into discrete, individual objects. We inquire into something that simply “oc-curs” (sich er-eignet), we experience the world in its precategorial temporal “thereness” (Jeweiligkeit). We are interested not so much in the quiddity of beings (the level of pseudo-primordial questioning presupposed by metaphysics qua ontology)—their “whatness”—but in their how-ness, their basic existential modalities. For Heidegger, metaphysics, by preoccupying itself with the whatness or quiddity of beings (especially that of Dasein), inherently reifies experience; it defines Dasein’s basic existential modalities as essentially thinglike and thereby freezes temporality. In the lexicon of “onto-theology,” however, things have various functions (telei or aims) and so does “man,” the “rational animal.” Yet, by predefining human Being-in-the-world, metaphysics a priori eliminates a potential for primordial experience proper to the domain of “existence” or “factical life,” a domain that for Heidegger is our “ownmost” (eigenste)—our most authentic or most proper sphere.

The ideological thrust of Heidegger’s discussion is clear. As was standard procedure for the German intelligentsia during the Great War, he enlists philosophy in the service of a “critique of civilization.” He views it as a weapon in the struggle against the values of “modernity” and the “West”: “Everything modern,” comments Heidegger, “is characterized by the fact that it slinks away from its own time in order thereby to produce an ‘effect’ (busy-ness, propaganda, proselytizing, economic cliques, intellectual profiteering).”46 Such lamentations concerning modernity, reminiscent of similar polemics from the Der Akademiker texts, resurface in the criticisms of “curiosity”—one of the basic modalities of the “they-self”—in Being and Time. Thus, Heidegger defines curiosity as a perennial search for “novelty” or the new. It is an extension of modernity’s preoccupation with “busy-ness” (das Betrieb), and, as such, an essential mode of self-forgetting Dasein—Dasein’s refusal to be a Self. As Heidegger explains: “When curiosity has become free, it concerns itself with seeing not in order to understand what is seen … but just in order to see. It seeks novelty only in order to leap from it anew to another novelty…. It does not seek the leisure of tarrying observantly, but rather seeks restlessness and the excitement of continual novelty of changing encounters.”47 In the German, there is an added parallelism, insofar as curiosity—Neugier—is etymologically related to neu or new.

Philosophy, declaims Heidegger in 1923, has no interest in solving problems of “universal humanity and culture.” Nor can its concern for “existence as the temporally determinate possibility of Dasein” become an “object of universal reasoning [Räsonnements] and public discussion.” Staunchly opposed to the values of “public reason,” Heidegger selfconsciously embraces the particularist standpoint of factical experience, which is always that of an individual self: “The Being of factical life is characterized by the fact that it is in the How of the Being of self-possibility. The ownmost possibility of itself that Dasein (facticity) is … is called existence.”48 When facticity or existence is at issue, as is always the case with fundamental ontology, the Protestant leitmotif, mea res agitur—“my life is at stake”—always come into play.

Heidegger’s discussion of facticity prefigures his later employment of Dasein: a being that is neither “subject” nor “object” but, qua “Being-in-the-world,” ontologically prior to both. Facticity is the “site of Being” (later, Heidegger identified this site as the “clearing” or Lichtung) in the same way as Dasein is the site of Being in Being and Time. In On the Vocation of Philosophy, Heidegger’s “Analysis of the Structure of Lived Experience” (Analyse der Erlebnisstruktur) distinctly foreshadows the “existential analytic” of Being and Time.

Phronesis and Existenz

“Being is said in many ways”—so begins chapter 7 of Aristotle’s Metaphysics. This was the remark that catalyzed the young Heidegger’s interest in philosophy. Yet he quickly became disillusioned with Aristotle’s response. Although many things are predicated of Being, “obviously,” concludes Aristotle, “that which ‘is’ primarily is the ‘what’, which indicates the substance of a thing.”49 Hence, for Aristotle, primary being—that which is “most real”—equals “substance” (ousia), which he goes on to define as that which remains the same throughout and despite all change. But early on, Heidegger felt that substance metaphysics—an orientation that dominated the history of ontology for 2,500 years—with its inordinate focus on the “whatness” of things, could not do justice to the wonder of “factical life”; nor could it account for the modalities of Dasein, whose essentially temporal nature defies fixedness or permanence. As the philosopher Werner Marx has appropriately observed: “When in our day a philosopher expressly poses the question of Being no longer as a question of essence and expressly thinks no longer in the sense of ousia or substance, we must regard this attempt as a veritable revolution.”50

Nevertheless, despite his pronounced reservations about substance metaphysics, Heidegger was convinced that the regeneration of first philosophy could only be achieved by way of a systematic reappraisal of Aristotle’s thought. Between 1921 and 1924, Heidegger taught no fewer than ten lecture courses or seminars related to Aristotle’s philosophy; about half bore the understated, nondescript title, “Phenomenological Interpretations of Aristotle.”

The key Aristotle text for Heidegger during this period—crucible years for the genesis of Being and Time—was Book VI of the Nichomachean Ethics. There Aristotle specified the different types of knowledge that were appropriate for various modalities of Being. Nous was a pure knowing suitable for cognizing unchanging first principles or pure Being. Poeisis was a type of knowledge that resulted in the production of objects. And, most important from Heidegger’s point of view, phronesis was a form of knowledge appropriate to men and women acting in concert with one another for the sake of living virtuously. In the Nichomachean Ethics, Aristotle went on to assay and categorize the essential human virtues. He stressed that in view of the multifarious and ever-changing nature of human affairs, knowledge of human action could never be absolute: “Let it be assumed that there are two rational elements: with one of these we apprehend the realities whose fundamental principles do not admit of being other than they are; and with the other we apprehend things which do admit of being other.”51 The second type of knowledge—phronesis—was proper to the domain of human practical life, and it inspired Heidegger’s view that a hermeneutical, rather than metaphysical, approach would be the most fruitful point of departure for existential analysis. Unlike the material objects produced by poeisis, Dasein was the source of its own motion; and, as self-moving, it possessed, unlike physical objects, the capacity to be a “Self”—a potential that Heidegger came to view as one of the distinguishing features of Existenz. Only Dasein exists; things in the world simply are.

Heidegger came to view Aristotle’s insight as the key to how one should conceptualize “factical life” or Being-in-the-world. Above all, Aristotle’s directives reinforced his sense of how fundamental ontology ought not to proceed: it should not begin with a reliance on the precepts and prejudices of “substance metaphysics”; for by proceeding in this way, it would subject Dasein’s Being to metaphysical standards and norms wholly inappropriate to it. Should it pursue this course, first philosophy would (as it so often had in the past) become an enterprise of mismeasure.

In Heidegger’s view, the approaches of ontology (Aristotle) and epistemology (Descartes) were equally misguided. One emphasized the primacy of substance, the other that of the knowing subject. The authentic phenomenological point of departure—“factical life”—was prior to both aspects, Heidegger believed, just as a “phenomenological intuition” is neither entirely subjective nor objective. Only an approach that takes this fact into account can do justice to our primordial encounter with Being.

In retrospect, it must be said that the “existential analytic” or “Dasein-analysis” of Being and Time represents a strange hybrid. On the one hand, from the Nichomachean Ethics, Heidegger assimilated a standpoint that emphasized the primacy of practical reason. In consequence, he understood Dasein’s Being in terms of the precedence of a series of “world-relations” related to Aristotlelian pragmata. Our relationship to the world of things is not primarily technical-scientific; it is not essentially concerned with “world mastery.” Instead, “things” fundamentally represent a site or horizon of human interaction; they constitute a “world” in the nonphysicalist, existential sense. The things of our everyday dealings are not undifferentiated “objects” confronting a disembodied “subject”; they are not simply present-at-hand (vorhanden). Instead, as objects of use, they implicitly stand in an integral, even semi-fraternal relationship to the men and women who manipulate them. It is this dimension of Being and Time that stands resolutely opposed to the modern epistemological conception of the self as self-positing subjectivity.

At the same time, this worldly, affirmative, Aristotelian side of Being and Time is offset by another dimension: the Protestant-theological aspect that derives autobiographically from Heidegger’s disillusionment with Catholicism circa 1917. These two dimensions comprise an uneasy admixture. Heidegger’s Protestantism manifests itself in his discussion of “falling” (Verfallen) as one of the fundamental traits of Dasein. It is this dimension that accounts for fundamental ontology’s bleakness: its Augustinian, angst-ridden view of human life.

Heidegger’s Protestant-theological inclinations are especially prominent in a recently rediscovered 1922 draft of Being and Time, “Phenomenological Interpretations with Respect to Aristotle.” As in Being and Time, Heidegger begins by characterizing “factical life” (Dasein) in terms of “care”: “in the concrete temporalizing of its Being it is concerned about its Being, even when it avoids itself.” However, for reasons that are far from clear, in Heidegger’s existential ontology self-evasion or faithlessness quickly predominates: “The most unmistakable manifestation of this is factical life’s tendency towards making things easy for itself”—falling away from the tasks of being a Self or authenticity. In Heidegger’s reading, the breach between fundamental ontology’s existential radicalism and all competing paradigms of truth and meaning is well-nigh total:

When factical life authentically is what it is in this Being-heavy and Being-difficult, then the genuinely appropriate way of access to it and way of truthfully safe-keeping it can only consist in making it difficult. All making-easy, all misleading currying of favors with regard to needs, all metaphysical reassurances based on what is primarily book-learning—all of this leads already in its basic aim to a failure to bring the object of philosophy within sight and within grasp, let alone to keep it there.52

In its quest for authenticity, Dasein is perpetually thwarted by a “basic factical tendency of life: a tendency towards the falling away from one’s own self and thereby towards falling prey to the world, and thus the falling apart from oneself.” “The tendency towards falling is alienating,” observes Heidegger, insofar as “factical life becomes more and more alien to itself in its being absorbed in the world.”53 In this way, Dasein’s self-understanding becomes progressively “world-laden” (welthaft): it tends to view itself as an entity or thing rather than as a (self-moving) Existenz; it thus bypasses opportunities for authenticity or self-realization. In essence, “life hides from itself.” Or, as Heidegger bluntly expresses a similar thought: “factical life … is for the most part not lived as factical life.”54 The seducements of alienation and falling away are most acute in the case of death. It is Dasein’s attitude toward death as an ultimate instance or boundary situation (Grenzfall) that determines whether it is able to temporalize its existence authentically.

Why was Heidegger’s view of Being-in-the-world so tendentiously grim? Does he, moreover, provide an adequate justification of his conception of human existence as characterized by the modalities of self-avoidance, alienation, and “falling?”

To take up the second question first: issues of justification have traditionally been one of fundamental ontology’s major weaknesses. Heidegger’s manner of philosophizing is, by contemporary standards, old school. He is uninterested in problems of ordinary language. Such problems are a priori devalued insofar as they derive from the inferior sphere of “everydayness.” As we have seen, this sphere, which has been colonized by the “they-self,” can make no serious contributions to matters of philosophical substance. The standpoint of the sensus communis, he believes, can only mislead. For Heidegger, philosophizing is an intrinsically aristocratic enterprise. As he remarked in his 1935 lecture course, “Truth is not for every man, but only for the strong.”55 In stark contrast with the pragmatist tradition (Peirce, Mead, and Dewey), his philosophical disposition is devoid of democratic sympathies. For Heidegger, the act of philosophizing suggests privileged access to a hermetic dimension of Existenz: the primordial experience of Being. In his estimation, almost all previous efforts in the realm of first philosophy are of such inferior worth that the very idiom of philosophical thought (Denken) must be recast from the ground up. Yet, as several critics have observed, by systematically shunning ordinary language and preferring unwieldy neologisms, a whiff of linguistic authoritarianism pervades Heidegger’s approach. Such lexical pomposity seemingly demands of readers a posture of compliant submission; it has the perlocutionary effect of compelling them to acquiesce passively in the face of definitive and grandiose proclamations. In the last analysis, it seems impossible to separate Heidegger’s philosophical authoritarianism from the question of his political authoritarianism. While the foregoing criticisms in no way disqualify the project of fundamental ontology, they do suggest some important caveats concerning its reception.

To be sure, the existential despondency that pervades the outlook of Being and Time is a peculiarly German inheritance. Many of the misanthropic tropes he employs are the stock and trade of German romanticism, stripped of the prospect of religious salvation and inscribed with an element of hard-edged, existential realism. Heideggerian Angst expresses the world-weariness of the romantic sensibility in an age when the hopes and consolations of an earlier era seem both anachronistic and unconscionably sentimental. In his philosophy, the romantic nexus between suffering and nobility of character has been filtered through the horrific images of Germany’s war experience. As far as German traditions are concerned, this was a point of no return. Of course, Heidegger never experienced these horrors personally. For a time he served as a weatherman, providing meteorological data in the event of gas attacks. But soon he was accorded a medical discharge (heart palpitations once again; in later years, he became so self-conscious about his poor service record that he provided false accounts in curriculum vitae). Nevertheless, the Kriegerlebnis (war experience) soon became an obligatory point of reference for Germany’s national conservatives. In particular, Heidegger’s emphasis on Being-toward-death as a touch stone of authentic existence strongly betrays such historical influences and residues.

Heidegger’s existential realism invites comparison with the political philosopher Carl Schmitt. Like Heidegger, following World War I Schmitt overcame a resolutely Catholic background to embrace political existentialism. Transposed to the sphere of international relations (Völkerrecht), political existentialism seemed to demand an end to “worldviews” (read: Wilsonianism) and a return to a purportedly non-ideological realism. Yet, insofar as Schmitt’s “realism” was ideologically directed against the West’s “universalism,” it became a de facto legitimation of German particularism—an expression of the ideology of the German “way.” Schmitt’s political existentialism culminated in the following claim from The Concept of Political (which appeared in 1927, the same year as Being and Time): “The high points of great politics are the moments in which the enemy comes into view in concrete clarity as the enemy”—so much for Western shibboleths about cosmopolitanism or the “rights of man.”56 In Political Romanticism, his first book following the Great War, Schmitt sought to distinguish the romantic incapacity for authentic political decision—which he viewed as a nineteenth-century atavism—from the new German mentality that had been forged in the crucible of the war experience: masculinist, fearless, resolute, and hard—the ethos of Hitler’s Schützstaffel avant la lettre. Heidegger, too, had imbibed much of this ethos: resoluteness (Entschlossenheit), in contrast with the vacillating ambiguity of the “they,” was one of the hallmarks of authenticity.57

Fundamental ontology performed a Husserlian epoché (reduction) upon the totality of inherited worldviews and cultural traditions. Whereas transcendental phenomenology utilized the reduction for epistemological purposes (in order to secure the cognitive ideal of “pure knowing”), Heidegger, in keeping with his Scholastic training, employed it for ontological ends. But once “essence” (essentia) had been bracketed as redolent of “substance metaphysics,” what was it that remained—the naked fact of existence in its unadulterated “thatness”? While there can be no doubting the boldness, novelty, and timeliness of this philosophical gesture, it ultimately led to an intellectual blind alley. In the tradition of onto-theology, existence was ensured of meaning insofar as it was provided with metaphysical guarantees or grounds: essence preceded existence, which secured a place for it (existence) within a larger, meaningful whole. After the systematic deconstruction of the history of ontology, “factical life” became devoid of underlying support. In a representative play on words, Heidegger celebrated this dilemma. Grund (reason or ground) had given way before the Ab-grund (groundlessness or abyss) of naked existence as such. At one point in Being and Time, Heidegger implored his readers to summon up the “courage for Angst” (Mut zur Angst). Following this initial radical act of deconstruction, the ensuing discussion of “tradition” and “handing down” (Überlieferung) in Division II of Being and Time could not help but sound hollow and insincere.

Heidegger’s solution to the problem of nihilism or meaninglessness followed the proverbial German formula of a Flucht nach vorne: he decided to seize the bull by the horns. Instead of fleeing the essential nihilism of the human condition by becoming “world-laden” (absorbed in the world), fundamental ontology would simply embrace it; “thinking the abyss” became its badge of honor.

1927: Anno Mirabilis

In 1927, Being and Time appeared in Husserl’s Yearbook for Phenomenological Research. Its hasty composition was in part a response to external constraint: Heidegger was not yet a full professor (Ordinarius) at Marburg, and the publication of a significant work was a necessary precondition for promotion. (In 1926, he had been refused an appointment at the University of Berlin due to a dearth of publications.) Heidegger wrote Being and Time in a remarkable creative burst between the spring and fall of 1926. During the writing, he frequently expressed deep reservations about the project in his letters to Jaspers. “On the whole, this is for me a transitional work,” observed Heidegger in May. Six months later, as the treatise neared completion, he confided to Jaspers that his estimation of the work’s value was not “excessively high”; although, having completed it, he had “learned to understand … what greater ones have aimed at.” Upon finishing it in December, he suggested to Jaspers that Being and Time’s chief merit was that it allowed him to work through a number of pressing philosophical problems and themes; having finished it he could get on with more promising philosophical work.58

Heidegger’s own methodological uncertainties were mirrored in the ambiguities of the book’s structure. It opened with a suggestive quote from Plato’s Sophist that placed the “question of Being” in the foreground and set the tone for the long introductory chapter, “The Exposition of the Question of the Meaning of Being”: “For manifestly you have long been aware of what you mean when you use the expression ‘Being.’ We, however, who used to think we understood it, have now become perplexed.” However, it proved difficult to reconcile the avowed focus on the Seinsfrage with the nature of the text that followed, which was preponderantly oriented toward existential rather than ontological concerns—i.e., concerns pertaining to the Being of Dasein. The question of Being resurfaces fleetingly at the book’s conclusion as a type of promissory note. Tellingly, Heidegger had announced that Being and Time was only the first book of a two-part work; Part II, Time and Being, was never written. In essence, and strange as it may seem, Heidegger spent twelve years climbing a philosophical ladder that would lead to the publication of Being and Time; when he reached the top, it seems, he threw the ladder away.

In Heidegger’s subsequent lectures and essays, the figure of Dasein is conspicuous by its absence. For example, his 1929 Freiburg University inaugural address, “What Is Metaphysics?”, represents a watershed insofar as the question of Being receives unambiguous pride of place; the Being of Dasein has ceased to be the primary focus of his inquiry. Heidegger’s discourse centers on the centrality of “nihilation” or “nothingness,” the attitude we must assume in the face of our customary, complacent relationship to the Being of beings. The concept of “nothingness” thereby indicates the radical degree to which the totality of “beings” must be reduced or “bracketed” in order for philosophy to accede to the heartland of “Being.”

Many of these issues surfaced in the legendary 1929 debate with Ernst Cassirer in Davos, Switzerland. Cassirer had been warned in advance about Heidegger’s frankly nihilistic relationship to all inherited cultural forms and unconventional personal bearing: Heidegger viewed himself as a revolutionary and iconoclast, a rugged outdoorsman who was scornful of conventional academic mandarin mores. And although Heidegger viewed the debate as insufficiently confrontational, contemporary observers were of an entirely different mind. The neo-Kantian Cassirer, author of a four-volume work called The Logic of Symbolic Forms, viewed culture as the indispensable bulwark that kept the fragile contingency of the human existence at bay. At one point in the debate, he sought to bring matters to a head by asking whether Heidegger wished to “destroy” the “entire absoluteness and objectivity” of culture in favor of the vagaries of human finitude. The battle lines thus drawn, Heidegger insisted that contemporary culture was a form of narcosis that prevented individuals from realizing their true freedom. Instead of seeking refuge in its stupefying blandishments, individuals, he insisted, must be returned to their existential nakedness and “the hardness of fate.”59

The trend toward a direct meditation on Being unmediated by the habitudes of Dasein continued with the important essays of the early 1930s: “On the Essence of Truth,” “Plato’s Doctrine of Truth,” and “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry.” In all of these texts, the question of the “meaning of Being”—which Heidegger came to view as fatally tainted by anthropological suppositions—cedes to the question of the “truth of Being.” Even when Dasein makes an ephemeral reappearance in later texts (e.g., the 1947 “Letter on Humanism”), Heidegger takes to hyphenating it—Da-sein—to emphasize that what is at stake is the “there” of “Being” rather than an entity one might confuse with human being. Upon reviewing these texts, there can be no doubt that the Kehre or “turn” in Heidegger’s thought dates from shortly after the appearance of Being and Time—not, as is commonly assumed, from the late 1930s.

A major indication of this drastic shift of emphasis may be found in the 1943 afterword to “What Is Metaphysics?” Whereas in Being and Time Heidegger had claimed that “Only so long as Dasein is—that is, the ontic possibility of the understanding of Being—‘is there’ Being,” in the 1943 postscript his characterization of the relationship between Being and beings underwent a complete volte-face, stressing the sovereign primacy of Being: “Being indeed essences without beings, but beings never are without Being,” claims Heidegger.60 And in the contemporaneous “Recollection in Metaphysics” (1941) he declares emphatically in the same spirit: “The history of Being is neither the history of man and of humanity, nor the history of the human relation to beings and to Being. The history of Being is Being itself and only Being.”61 How might one account for this revolutionary change of direction in Heidegger’s approach?

Reconstructing Heidegger’s developmental path, it is clear that his motivating concern was a reformulation of the question of Being. Yet, along the way, and coincident with his fateful abandonment of the “religion of his youth,” Heidegger became convinced, in good Lutheran fashion, that one could only gain phenomenological access to our primordial encounter with Being via the route of Dasein or human being. It was precisely in this sense that he affirmed in Being and Time that “Only so long as Dasein is … is there Being.” His preoccupation with the classic texts of Protestant theology during the late 1910s and early 1920s, as well as his ensuing concentration on Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics (where the modalities of areté or human excellence are at issue), reaffirmed his conviction that he was pursuing the right course. Clearly, from an existential standpoint, the results were provocative, fascinating, and virtually without philosophical precedent; the end result is the “existential analytic” of Being and Time, the crowning achievement of Heidegger’s early philosophy.

Yet, from a scholastic-ontological standpoint, the results were disappointing. Despite its pathbreaking nature, Heidegger’s great work of 1927 made little headway in addressing (let alone resolving) the question of Being. Commentators were at pains to reconcile the two apparently competing agendas of Being and Time, one existential, the other ontological. Clearly, the goal of fundamental ontology was to reconcile these two areas of concern. But given Being and Time’s inordinate focus on the vagaries of existential analysis—on the various modes of Dasein’s Being-in-the-world—there was little room left for an autonomous treatment of the Seinsfrage.

In her encomium on the occasion of Heidegger’s eightieth birthday, Hannah Arendt proffered the following astute observations concerning the ontological impetus underlying the Master’s philosophy:

The storm that blows through Heidegger’s thinking—like the one that still sweeps toward us from Plato’s works after thousands of years—does not originate from the century he happened to live in. It comes from the primeval (aus dem Uralten), and what it leaves behind is something perfect that, like all that is perfect, returns home to the primeval.62

With these words, Arendt has faithfully captured the motivations underlying the “turn” in Heidegger’s thought from existence to Being.

Heidegger’s fascination with Being’s primeval origins would, of course, take him back well beyond Plato. Ultimately, he perceived Plato’s doctrine of Being as insufficiently radical. According to Heidegger, with his theory of ideas, Plato had introduced a fatal separation between sensible and supersensible worlds, a division that would become the signature of Western metaphysics in its entirely—as well as the hallmark (at least in Heidegger’s estimation) of its perdition. The theory of ideas sought the truth of Being not in Being itself, but in something “subjective”: the Eidos (idea) qua “representation”; and what was “representation” other than a subjective construct? Heidegger sought to undo the fatal conflation of Being with representational thinking via the antisubjectivist orientation of the “turn.” Ultimately, he sought inspiration and direction in the pre-Socratic doctrines of Parmenides and Heraclitus; he believed that their philosophy offered a glimpse of authentic “proximity” to Being (Nähe) in its pristine, antediluvian glory—a glimpse unequaled by the representatives of post-Socratic thought. Kisiel speaks felicitously of Heidegger’s primordial fascination with “the It that empowers theoretical judgments” (as in: “it occurred to me” or “it so happened”): “Throughout his long career, Heidegger will never seek to surpass this central insight which gives priority to the impersonal event enveloping the I which ‘takes place’ in that Event.”63 To be sure, the results often sounded far-fetched and ponderous to modern ears; to wit, his portentous claim in a 1938 lecture course that “Being is the trembling of the Godding.”64 Although it would be foolish to minimize the importance of his multiple—at times breathtaking—changes of philosophical direction, one can safely say that Heidegger’s fundamental question remained the one he first posed in his dissertation on Brentano: the question of Being. Thus, the line from Hölderlin he was fond of citing would be an especially appropriate epigram to characterize the thrust of his life’s work: “As you began, so will you remain.”