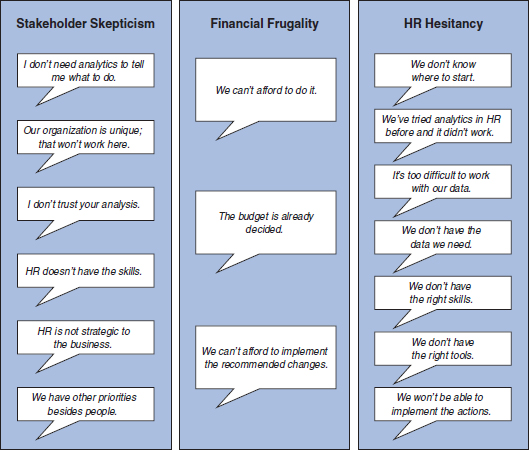

Figure 16.1 Categories of resistance to workforce analytics.

“Some people will say it will never work. That’s when the risk–reward analysis would be helpful: Determine the investment needed to get an early win, take on a smaller problem, demonstrate a win, then move on to more projects.”

—Mats Beskow

Director of Human Resources, Landstinget Västmanland

In their quest to bring analytics to the HR function, practitioners have faced many forms of resistance. These range from stakeholder concerns, to unwillingness to invest financially, to doubts from the HR function itself. All of these forms of resistance can be overcome.

This chapter discusses the following:

• Types of resistance to workforce analytics: Stakeholder skepticism, financial frugality, HR hesitancy.

• Suggestions for overcoming each type of resistance.

In their quest to bring analytics to the HR function, practitioners have faced many counterarguments. Types of resistance can be grouped into three general categories (see Figure 16.1):

• Stakeholder skepticism

• Financial frugality

• HR hesitancy

The first step when faced with resistance is understanding the underlying causes. Armed with that knowledge, you will be able to address the resistance and succeed in bringing analytics to HR.

Figure 16.1 Categories of resistance to workforce analytics.

Stakeholder skepticism can range from doubts about the value of analytics to doubts about the value of HR. Following are frequently heard expressions of doubt and suggestions for addressing them.

A stakeholder might resist analytics with a declaration of “I already know the answer” or “I know what the problem is and I know how to fix it.” This can be a particularly pervasive mind-set: All business leaders have had responsibility for managing people, and many consider themselves experts in people issues, given their achievements as a manager or executive. Therefore, the notion of people-related analytics might seem entirely unnecessary. However, if they think they already know the answers to their challenges, it is fair to ask, why haven’t they addressed them already?

You might think it’s clear that foregoing an analytical approach can lead to misguided and costly actions (or inaction), but your stakeholders might be less convinced. Our guidance is to first determine the underlying cause of the skepticism. Do you suspect that your stakeholder is worried about being proven wrong? If yes, the best course of action might be to enlist the services of a third-party partner who is better positioned to ask challenging questions and deflect any negative ramifications if the findings don’t confirm what the stakeholder expected.

In other cases, the underlying issue might be a reluctance to address a particular problem, a failure to acknowledge the problem, or an unwillingness to change the way things have always been done. In these circumstances, the solution might be to find a different, influential sponsor in the organization. Antony Ebelle-ebanda, Global Director of HCM Insights, Analytics & Planning at S&P Global (formerly McGraw-Hill Financial) advises: “Ensure you have a strong senior champion to move things forward. It is not enough to be doing great work. This doesn’t need to be a specific person or role, but it does need to be someone from the business who has influence.”

When leadership’s objection is that the company is unique and analytics won’t work, the response should be: That’s all the more reason to invest in workforce analytics (or, for that matter, any analytics). If the environment is truly unique, you need to understand what works and what doesn’t for the organization’s specific context. Being unique is not at odds with being analytical. Furthermore, analytics customized for your organization will enable the specificity needed for market differentiation and increased competitiveness.

Although local customizing is important, so is taking advantage of any existing relevant knowledge base before undertaking your project. Decades of scientific research have produced valuable insights on a wide range of work-related topics, and overlooking that knowledge would be counterproductive. Mark Huselid, Distinguished Professor of Workforce Analytics and Director of the Center for Workforce Analytics at Northeastern University, reflects: “We’ve been playing at workforce analytics, at various levels, for a long time. I hope to see greater integration of what we already know—domain-specific knowledge—into the questions and answers we’re looking at. I see a lot of analytics work that could be much better if the folks involved only knew there’s a body of literature on it.”

Avoid getting defensive if someone doesn’t view your work as credible. A lack of trust in the analysis, or a failure to appreciate the impact of people factors on the business, is best addressed by building positive relationships with the skeptics over time. Listen carefully to try to determine what specifically they don’t trust (for example, concerns about the data or unexpected findings that they don’t view as credible), but don’t feel that you always have to convince people you are correct. Make sure to listen and determine how you can be helpful in subsequent opportunities to address their business challenges.

“Start by understanding where you can be helpful. Delivering something useful for decision making, regardless of how simple or fancy it is, may help relationship building.”

—Jeremy Shapiro

Global Head of Talent Analytics, Morgan Stanley

In some organizations, the HR function has a reputation for focusing on the “soft” people side of things or lacking an analytical mind-set and quantitative skills. HR practitioners might even see themselves this way. If you face this type of reputational resistance, the best way to overcome it is with evidence to the contrary: Demonstrate your analytics prowess with your first project (see Chapter 9, “Get a Quick Win”).

If other functions in your organization, such as marketing or finance, are known to have strong analytical skills, you can benefit from their reputation by aligning your work with theirs and borrowing some skilled resources or ideas to get you started. Make those resources highly visible to fully benefit from their reputation. If this is not feasible, you need to hire or contract analytical people for your team. Ideally, they should be reputable analytics powerhouses (based on their previous experience or qualifications). With these resources, demonstrate your team’s own analytical contributions, and enable others in the HR function to think analytically and embrace an analytical approach. You will then be well on your way to altering the nonanalytical reputation of HR.

Some organizational leaders do not view HR as a strategic business partner and instead see the function as mainly administrative in nature. When faced with this perspective, your credibility might be in doubt simply through association with the HR function. The way to remedy this situation is to prove the skeptics wrong: Forge ahead with an analytics project and return with a solid story demonstrating the value to the business. Ian Bailie, Global Head of Talent Acquisition and People Planning Operations at Cisco, illustrates this point: “You find the least resistance in helping someone solve a problem they have. As a function, HR can sometimes be seen to be doing something because HR wants to do it rather than thinking of the business and what is of value to it.”

Focusing on what is of value to the business often leads to incorporating financial data into workforce-related analyses. This has the added benefit of boosting HR’s credibility by working with finance colleagues to demonstrate the quantitative nature of workforce analytics projects.

Another way to help business leaders appreciate the strategic value of workforce analytics is to raise awareness that leading organizations are increasingly embracing an analytical approach to HR. Your competitors are likely already applying analytics to the HR function and gaining an advantage as a result. Furthermore, the amount of data available for such analyses will only continue to grow. Ignore it at your peril; you will fall further behind if you do.

Finally, pay attention to how you communicate your analytical findings. Demonstrate your understanding of the business in the language you use, and draw a clear link between business challenges and your work. Make good use of storytelling and data visualization, to have the greatest influence. Eric Mackaluso, Senior Director of People Analytics, Global HR Strategy & Planning, ADP, shares: “We started focusing on storytelling, laying out a storyboard. The data tell you what’s happening; stories tell you why it matters. You have to frame it in a way people understand.” For more on this, see Chapter 17, “Communicate with Storytelling and Visualization.”

Some leaders might not see the links among people-related decisions, actions, and business outcomes. If people are viewed as easily replaceable and interchangeable, the logic of investing time and resources into workforce analytics might not be immediately apparent. Although the wisdom of viewing the workforce in that manner can be debated, the role that analytics can play should be clear.

Luk Smeyers is Cofounder and Principal of iNostix by Deloitte.1 He describes a frequent challenge that he calls the accountability hazard: “As soon as managers from highly political, nontransparent, or even negative organizational cultures learn what HR analytics could mean for their organization, the business benefits become overshadowed by the risk of having areas of weakness, dysfunction, and incompetence exposed.”

This hazard recently affected Luk’s team: “Not long ago, we had to call a halt to a new HR analytics project after very animated internal discussions about who was responsible for the less pleasant potential analytical outcomes.” This presents a challenge for the workforce analytics leader who is investing time and resource into analytics projects, only to have them derailed at the action stage.

Based on his experiences, Luk offers some tips to help the workforce analytics leader and other HR professionals overcome this accountability hazard:

• Work in close collaboration with other departments to establish a co-creation atmosphere, with early engagement and buy-in from other functions.

• Develop strong support from business leaders early on specific analytics projects.

• Ensure that the privacy of employees is never violated, and stay away from “the hunt for the bad performer.”

• Strive for new insights so that managers willingly take accountability for actions because they support new ways of improving their businesses.

With these approaches, Luk has found that workforce analytics leaders can avoid the problems of accountability and ensure that actions can be implemented successfully. At the end of the day, analytics is impactful only if action is taken.

Even if people are viewed narrowly as merely a cost of doing business, people acquisition and lifecycle management processes can certainly be optimized using an analytical approach. And people costs, for which HR is usually responsible, are often the greatest operational costs in an organization (capital-intensive industries are an exception). Does any other expenditure of this magnitude escape analysis, tracking, and management with scrutiny and an eye toward optimization?

Perhaps more important is the recognition that, in most cases, without people, there is no organization. The viability and effectiveness of public and commercial institutions alike depend on the attributes of the workforce. Understanding the relationships of those attributes to outcomes requires an analytical approach.

A strong emphasis on managing costs can sometimes result in missed opportunities to create future value. This is true for many organizational decisions, including whether to invest in workforce analytics. Following are typical financial reasons for holding back and suggestions for addressing them.

When faced with this situation, we recommend asking this question: Can you afford not to do it? This is where the business case becomes crucial. The message you need to convey is how costly it can be, and how growth opportunities can go unrealized, when the people side of the business is run solely on intuition or the way things have always been done. Workforce analytics projects often result in substantial savings or improved productivity and effectiveness (see Chapter 6, “Case Studies”).

Considering that people costs are often among the highest in an organization, how can organizational leaders even think about not managing their biggest expenditure analytically? Patrick Coolen, Manager of HR Metrics and Analytics at ABN AMRO, agrees: “If you ask a business leader ‘Do you want to know how you make money on insights from people data?’ no one will say no.” And remember, the initial investment does not need to be big (especially when considered in proportion to total people costs). You can certainly start small and build as you go.

Perhaps leadership is interested in workforce analytics, but HR expenditures have already been allocated for the budgeting cycle. Under these circumstances, a little creativity might be in order. Identify where money is being spent and determine whether the workforce analytics team can take on some of the work and the associated budget. If you can do the work for the same cost (or less) while delivering incremental insights and value, you will garner support for investment in your team.

Ian Bailie of Cisco was able to do just this: “I’ve gone after money that was being spent on external work and used it to fund our analysts instead. We were able to deliver what external research was providing plus so much more. And that supports continued investment.”

Analytics projects should result in actions. Depending on the nature of the recommended actions, funding might be required to implement them. Planning for large-scale or costly changes should be anticipated in advance and built into your analytics project plan; where possible, choose less costly actions for your initial projects. When funding is, in fact, needed for the recommended actions, the business case again becomes an important tool.

In addition to estimating the short- and long-term anticipated benefits of the recommended actions, opportunity costs associated with inaction should be also modeled. These ideas can be conveyed with great effect by skillfully weaving scenarios and projections into a story linking the business problem to the analyses and to the recommended actions.

Sometimes the reluctance to embrace workforce analytics comes from the HR function itself. Potential causes of resistance are many, from not knowing where to begin, to having concerns about data, tooling, and the ability to follow through with actions. Following are common concerns from HR and suggestions for addressing them.

The thought of applying analytics to a workforce challenge can be overwhelming for someone who has never done it. If that describes you, the fact that you are reading this book is a good start! You might also want to bring in someone who has relevant experience to help you. Hire someone with data analytical skills (such as a data scientist or an industrial-organizational psychologist). Identify your business leaders’ key performance indicators (as an HR leader, you should be well positioned to do this—a useful line of questioning is “What keeps you up at night?” and “Which of your business metrics are you most concerned about?”) and think through how people-related issues influence those metrics. A skilled analyst can then help design and implement appropriate analytical approaches to address the business questions with people data.

Recent advances in technology and data management, along with analytics maturity and sophistication achieved by other functions such as marketing and finance, have opened up opportunities for HR that were not as readily available to practitioners in the past. Times have changed. The advent of cloud technology has brought tremendous computing power to people’s fingertips, and new data sources have become available along with methods and tools for analyzing them. Approaches used in other functions can be applied successfully to HR data (for example, customer churn analytics can serve as a model for analyzing employee attrition). If you’ve tried before, it’s time to try again. Yesterday’s challenges and roadblocks are likely a thing of the past.

“The advent of cloud technology has brought all this computing power to the fingertips of people in HR. Now everyone on the planet has access, when nobody had access before.”

—Josh Bersin

Principal and Founder, Bersin by Deloitte

Nobody’s data are perfect, but that should not prevent you from moving forward. If your data are particularly difficult to work with (incomplete, outdated, scattered across systems, and even buried in spreadsheets), scale down and start small. Begin your work with a business question that uses a well-contained, well-defined dataset. The key is to get started and build as you go.

Starting anew with workforce data can actually be a liberating experience. When Mariëlle Sonnenberg started as Global Director of HR Strategy & Analytics at Wolters Kluwer, no enterprise-wide HR information systems were in place. Although this might have been concerning for some team leaders, Mariëlle saw it as an opportunity: “Because of this, I was able to define a small number of metrics, and the HR teams became actively focused on collecting good-quality data and maintaining it. It is more difficult to go the other way, to start with one big system of data.”

Andre Obereigner, the Senior Manager of Global Workforce Analytics at Groupon,2 heard many reasons for procrastination as he was starting out: “We don’t know where to start. We don’t have the data we need. We don’t have the right tools. We don’t have the right skills.” However, when it comes to starting, he has a few tricks up his sleeve.

Andre started a project by himself to prove the value of analytics. The business problem concerned retention, but no one had data or skills or the right systems to quickly find out why retention was a problem. So Andre went out and gathered the data himself: “In 2013, I started by doing an EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa) exit survey in which we asked those who had resigned from Groupon to provide general feedback and recommendations for the organization.”

Andre’s skills alone were not enough. He needed tools, but he didn’t buy complex technology at that stage: “I used Tableau and imported the English-language data into it. I then cleaned and prepared it for the text prediction model. Initially, I had 100 to 150 responders and I went through each manually to come up with six different topics of feedback. I found features in the feedback that predicted the topics; then I could apply that to new feedback from more exit surveys.”

Andre’s success was mostly due to starting small, being persistent, and ensuring that he adapted as he went along. “The stakeholder was me at the beginning. I started this project on my own—I spoke with my manager to see if she would support me. It was part of my studies, but no one else really knew about this. I also worked on it outside of my regular work hours.”

In the end, the project was a success: “At the beginning of 2015, our new global head of HR wanted to have a global exit survey. So we made adjustments to the EMEA one and got going.” If Andre had been put off back in 2013 by all the reasons why not, it would have been almost impossible to do the global project two years later.

Andre’s motto? Don’t take “We can’t” for an answer.

All hope might seem lost when you really need a particular piece of data and it’s nowhere to be found in the organization. But chances are, there’s a way forward. Get creative. Look at what you do have available, and try to think of ways to approximate the data you need by combing existing data elements or tapping into less traditional data sources. You always have the option of initiating new data collection. As Mariëlle Sonnenberg’s experience shows, not having to deal with legacy systems can be beneficial in its own right.

Also keep in mind that many more sources of readily available data exist today than in the past, along with tools to analyze different data types. For example, internal and external social media data might provide useful information for testing some of your hypotheses, and modern tools provide the means of analyzing topics, trends, and sentiment.

A base level of knowledge is needed to successfully bring analytics to the HR function. However, you might be able to acquire those skills in a cost-effective way. Explore opportunities to borrow skilled people from another function in the organization, or consider hiring an intern: Interns are often exposed to the latest and greatest in data analytic techniques, and many highly skilled students are eager to gain some real-world experience. Contacting local colleges and universities can be a good starting point for connecting with talented analytics students.

Sophisticated software can be extraordinarily powerful and valuable, but it’s perfectly fine to start simple. Many practitioners will tell you that their most impactful projects started with rather simple, rudimentary analyses. In fact, some highly skilled practitioners even lament the dearth of opportunities to apply sophisticated analytics techniques to their organization’s most pressing challenges. Complexity is not a requirement for analytics success. Ubiquitous spreadsheet software might even suffice in providing the basics you need for an initial analysis—for example, plotting distributions of your data, calculating average differences across groups, and computing correlations.

Although it’s true that analytics are of limited value if follow-up actions aren’t implemented, concerns about the ability to implement actions should not prevent you from bringing this potential source of value to your organization. Instead, think through the possible outcomes of the analytics, as well as the associated actions. For example, if you are analyzing which recruiting sources yield the best-fit candidates, you might prepare to abandon some recruiting sources and further invest in others. Discussing these potential actions with your stakeholders before you begin the analyses might be helpful so that you prepare them for the possible outcomes and actions (for example, their favorite recruiting source, their alma mater, might be deprioritized).

Having these conversations up front helps you substantially mitigate the implementation risks. Ian O’Keefe, Managing Director and Head of Global Workforce Analytics at JPMorgan Chase & Co. offers this advice: “Always ask the question ‘What would you do if you knew the answer to this?’ Ask it at the start of the analyses and again when you finish, and then you still won’t have asked it enough.” In addition to preparing for potential outcomes in advance, we recommend focusing on Quick Win projects to get started because these projects are characterized by less implementation complexity.

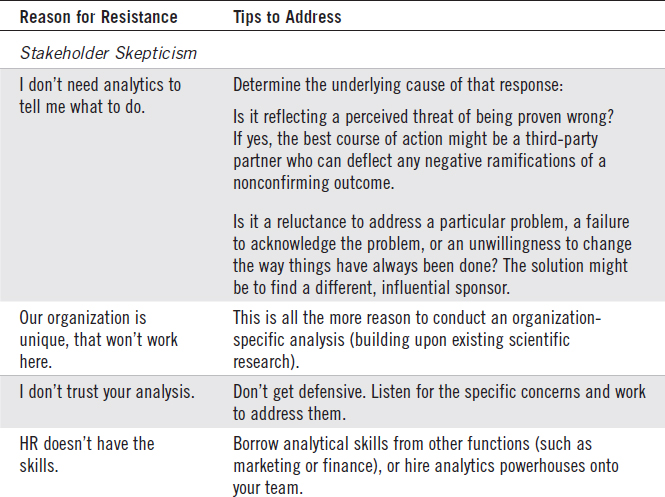

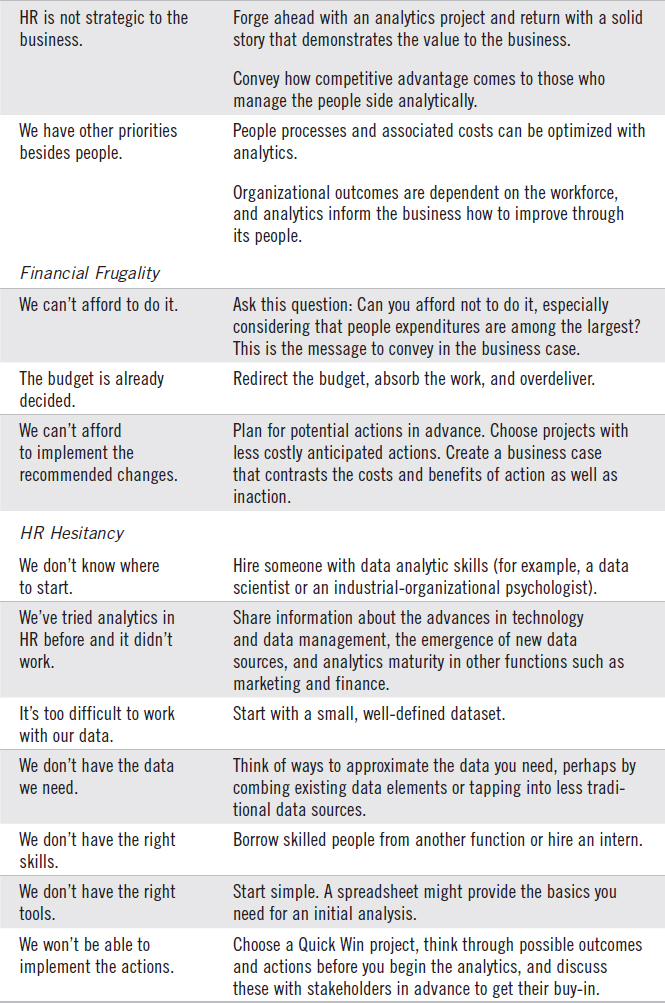

In summary, you might encounter several types of resistance in your efforts to bring an analytical approach to HR. Each is best addressed with logic and assistance from experienced colleagues and practitioners (see Table 16.1).

Table 16.1 Reasons for Analytics Resistance and Tips for Addressing Them

Efforts to bring workforce analytics to an organization are sometimes met with resistance. For almost any reason offered for why workforce analytics “won’t work here,” an appropriate counterargument can be made. The following tips can help successfully overcome resistance:

• Understand how your organization views the value of analytics.

• Identify the sources and the nature of resistance by spending time listening to others’ perspectives.

• Determine the underlying cause of resistance, such as skepticism, perceived threat, lack of trust, lack of understanding, perception of insufficient skills, or unwillingness to invest.

• Choose how to overcome the resistance; possible actions include educating, demonstrating value, partnering for skills, starting small, keeping it simple, making your case, and helping the resistor succeed.

1 iNostix by Deloitte is a team of market-leading predictive HR analytics experts based in Belgium. It offers clients a unique combination of senior expertise in HR management and data science. iNostix was founded by Luk Smeyers and Dr. Jeroen Delmotte in 2008 and was acquired by Deloitte in 2016 (www.inostix.com).

2 Groupon (NASDAQ: GRPN) is a global e-commerce marketplace that connects millions of subscribers with local merchants by offering activities, travel, goods, and services in more than 28 countries. According to its website, it is building the daily habit in local commerce, offering a vast mobile and online marketplace where people discover and save on amazing things to do, see, eat, and buy. It was founded in 2008 and is headquartered in Chicago (www.groupon.com).