Birds bring one of the most obvious of wildlife pleasures to the garden, in all their colours, patterns and behaviours.

Gardening for Birds

Of all the groups of wildlife that people like to help in the garden, birds almost always come top of the list. I’m sure that the woodlice, spiders and wasps of this world find that very unfair, but birds have a lot going for them: they are visible, audible, often pretty and regularly entertaining.

If that wasn’t enough, they are often the gardener’s friend, mopping up slugs, snails, aphids and insects. And the one extra thing about them that can make us wildlife gardeners very happy is that birds respond really well to the help we offer them. If you do the right things, birds will spend more time in the garden, new species will take up residence and several can easily be encouraged to breed.

Birds bring one of the most obvious of wildlife pleasures to the garden, in all their colours, patterns and behaviours.

The species entries that follow cover the home needs of about 50 of the most regular visitors to our gardens. They start with the 12 commonest garden birds as revealed in UK surveys, such as the RSPB Big Garden Birdwatch, and then work through another 40 species in field guide order. But let’s sneak in some useful advice about the home needs of garden birds in general.

Habitat: Birds can be very picky indeed about what makes the ideal home. ‘Trees’ or ‘lawns’, for example, often aren’t enough – they need the right kinds of trees or lawns.

Habitat: Birds can be very picky indeed about what makes the ideal home. ‘Trees’ or ‘lawns’, for example, often aren’t enough – they need the right kinds of trees or lawns.

Food: Birds’ diets can be surprisingly varied, more so than what you can provide on the bird table. Your gardening will have to deliver much of the menu, and a ready supply of insects is critical for more species than you might think.

Food: Birds’ diets can be surprisingly varied, more so than what you can provide on the bird table. Your gardening will have to deliver much of the menu, and a ready supply of insects is critical for more species than you might think.

Territory: Breeding birds usually defend a territory. The better the habitat, the smaller the area they need, but even so it is unlikely that your garden will be large enough on its own. By understanding how much room birds need, you will be able to see how much of their home range your garden can provide, and how many other good gardens they’ll also need to use. Remember, one hectare (ha) is a bit bigger than a football pitch.

Territory: Breeding birds usually defend a territory. The better the habitat, the smaller the area they need, but even so it is unlikely that your garden will be large enough on its own. By understanding how much room birds need, you will be able to see how much of their home range your garden can provide, and how many other good gardens they’ll also need to use. Remember, one hectare (ha) is a bit bigger than a football pitch.

Nest site: Having somewhere to nest may sound obvious, but it is interesting how often this is the missing or substandard ingredient in gardens. Nest boxes are the solution for only a few species; without your help the rest often have to make do with very poor and vulnerable places, or they are forced into moving out into the countryside when the breeding season comes.

Nest site: Having somewhere to nest may sound obvious, but it is interesting how often this is the missing or substandard ingredient in gardens. Nest boxes are the solution for only a few species; without your help the rest often have to make do with very poor and vulnerable places, or they are forced into moving out into the countryside when the breeding season comes.

Nesting material: Note closely what material birds use for their nests – it can be hard for them to find what they need if we’ve gone and burnt, composted or thrown away all their preferred materials.

Nesting material: Note closely what material birds use for their nests – it can be hard for them to find what they need if we’ve gone and burnt, composted or thrown away all their preferred materials.

Broods: In order to raise enough chicks to maintain the population, many species must raise more than one brood in a season. On top of this, many clutches of eggs are predated or the adults are disturbed before their eggs hatch, so to pull off just one brood the female may need to re-lay her clutch, often in a new location.

Broods: In order to raise enough chicks to maintain the population, many species must raise more than one brood in a season. On top of this, many clutches of eggs are predated or the adults are disturbed before their eggs hatch, so to pull off just one brood the female may need to re-lay her clutch, often in a new location.

Birds and the law

All birds, their nests and eggs are protected by law, and it is an offence, with certain exceptions, to:

•intentionally kill, injure or take any wild bird,

•intentionally take, damage or destroy the nest of any wild bird while it is in use or being built,

•intentionally take or destroy the egg of any wild bird.

Blackbird

Turdus merula

A delightful and familiar presence in gardens, Blackbirds seem perfectly suited to our urban green spaces. With such a sublime song to boot, here’s one species we all want to help.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Very common throughout the British Isles, except in north-west Scotland and mountain areas. Our resident birds are boosted by winter visitors from Scandinavia.

Habitat: Versatile, but basically a bird of the woodland edge liking a mix of bare ground, leaf-litter and short grass, plus the shade of bushes and trees. Once rare in gardens, they now thrive in them, even in city centres, although they do best in ones that are large, leafy and lawned. They like somewhere to bathe, too.

Habits: They feed mainly on the ground, hopping a short way and then stopping, and bolting back into cover if danger is sensed. They toss leaves aside or scratch at the earth to uncover prey.

Food: Insects and worms all year; berries and fruit in autumn. They take some seed from bird tables.

Roost: Thick cover, such as evergreen trees or climbers.

Breeding: They breed freely in gardens. The nesting territory can be as small as 0.2ha, but is usually 1ha or so. They nest in trees and bushes (conifers and deciduous) up against the main trunk, in climbers against a wall, inside sheds and outbuildings, or in low tangled vegetation. The nest is a well-constructed cup of twigs, grasses and stems on a bed of moss, lined with mud and fine grasses. They raise two to three broods, occasionally more. The three to five eggs in each clutch are laid March–July and are incubated for two weeks. The young fledge two weeks after hatching.

So… Make life easier for Blackbirds and help them rear more chicks by mulching flower beds with leaf-litter, keeping a mown lawn, planting fruiting shrubs and trees (especially dense, thorny ones), and by planting climbers against walls.

Blackbirds, such as this beautiful, glossy male, love our ‘glades of grazed grass’ (AKA lawns) perhaps more than any other bird.

Robin

Erithacus rubecula

Familiar, approachable and inquisitive, the Robin is one of our best-loved birds. There’s plenty you can do to help them, especially to encourage them to breed.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Very common resident throughout the British Isles, except in northern Scotland and the mountains.

Habitat: Found wherever there are relatively mature trees that offer cool shade, a moist woodland floor, sunny glades and perching posts. They are very fond of recently turned soil.

Habits: Fiercely territorial throughout the year. They feed mainly on the ground, often watching from a low perch (such as a spade handle!) and then darting down to grab an insect. They don’t turn over leaf-litter.

Food: Crawling insects such as beetles, ants and earwigs, quickly taking advantage when we (or other animals) dig. In autumn they eat some seeds and berries. At the bird table, mealworms are ideal, but they avidly take fat, although they struggle to cling to most feeders.

Roost: In dense cover such as Ivy or thick conifers.

Breeding: Maintains a winter territory of often less than 1ha, and a summer territory of 0.25–1.5ha. They nest in a hollow, be it in a wall, a tree, an open-fronted nest box or strange places such as hanging baskets! The nest is a bed of dead leaves topped with a cup of grasses, hair, moss and more leaves. They raise two broods (one in the north). The four to six eggs in each clutch are laid March–June and incubated for 12–21 days. The young fledge 10–18 days after hatching.

So… Gardens are great for Robins in winter but are often pretty poor in summer. If you can develop a shady woodland garden, increase the number of safe nest sites and boost your beetles, you stand a much better chance of hosting a breeding pair.

The Robin’s red breast is a powerful signal to rivals to back off, or prepare to fight.

Blue Tit

Cyanistes caeruleus

If they were rarer, we’d be bowled over by the beauty of these little acrobats. It’s probably the easiest bird to get to breed in your garden, and one of the most regular at bird feeders.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: An abundant resident in lowland areas throughout the British Isles.

Habitat: Needs deciduous trees, especially oaks and birches, favouring sunny woodlands, parks, large gardens and hedgerows.

Habits: They work methodically from tree to tree, scouring branches and foliage for food, often dangling upside down. In winter, they wander in flocks with other tit species over an area of usually up to 10ha, although some are nomadic.

Food: Mainly insects and spiders gleaned from the trees, especially caterpillars in spring, but they also eat seeds, berries and nectar. Agile visitors to feeders, they take peanuts and sunflower seeds, and like to carry off large seeds to the safety of the trees – ‘tit takeaways’!

Roost: In a hole in winter; often in dense foliage in summer.

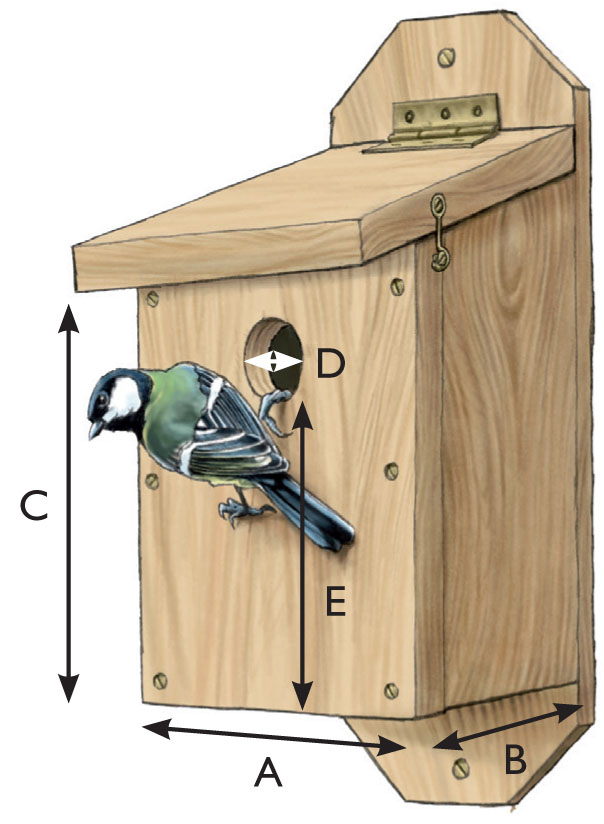

Breeding: Territory about 0.5–1ha. They nest in a tree hole, preferably 2–5m off the ground, and willingly use a nest box or hole in a wall. The nest is a thick wad of moss, fine grasses, wool and hair. They raise one brood (occasionally two). The 6–16 eggs in each clutch (fewer in small nest boxes) are laid in April–mid-May and are incubated for 12–16 days. The young fledge after 16–23 days.

So… Provide a nest box with a 25mm hole and keep those peanut and seed feeders topped up, but don’t stop there. If you want plenty of chicks to survive, you need trees full of insects. Go for leafy broadleaved trees, as large as you dare go.

For a bird that is essentially a woodland species, the Blue Tit does incredibly well in gardens, but it does still need lots of trees.

Great Tit

Parus major

This bulky, strident tit with its cheery ‘teacher teacher’ song is not quite as common in gardens as its cousin the Blue, but is still a regular visitor to feeders and nest boxes.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: A common resident throughout much of the British Isles.

Habitat: Likes deciduous trees and scrubby undergrowth, not too packed and with a few conifers, such as in woods, parks, gardens and hedgerows.

Habits: Forages through the trees, often low down in winter and even on the ground. Goes higher in spring to take caterpillars. Wanders about in small flocks in winter over an area of perhaps 4–8ha.

Food: Insects and spiders, especially moth caterpillars, beetles, flies and bugs. Also seeks berries and seeds in winter, including beechmast, hazelnuts and acorns. Takes peanuts and sunflower seeds at bird feeders.

Roost: In a hole (including nest box) in winter; in dense foliage in summer.

Breeding: A male defends a territory of 0.5–3ha. They nest in a tree hole, nest box or hole in a wall, making a nest similar to the Blue Tit’s only even more luxurious. They raise one to two broods. The 5–12 eggs in each clutch are laid April–May and are incubated for 12–15 days. The young fledge after 16–22 days.

So… The advice is the same as for Blue Tits, but the nest box holes should be 28mm diameter. To offer a garden stuffed with tree-living insects is the five-star hotel that will mean more Great Tits can raise more chicks.

The black line down the breast allows you to distinguish males (thick and solid line) from females (thin and patchy line, as here).

House Sparrow

Passer domesticus

From being the ‘common or garden’ bird, the House Sparrow’s calamitous decline was one of nature’s great mysteries. At last we know some of the things it needs to help it survive.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Common resident except in highland areas, but numbers are much reduced across almost all of the British Isles.

Habitat: Rarely seen far from habitation, they love allotments, stables and farmyards but are now found in far fewer gardens and are absent from many city centres.

Habits: In the breeding season, they live in small colonies of up to 20 pairs, but in winter may band up in flocks several hundred strong, often in stubble fields. They enjoy gossiping sessions (‘chapels’) in thick hedges and are fond of dust bathing. They always like to be close to cover but will readily perch on buildings.

Food: Seeds, taken mainly from the ground, especially cereals and grasses, plus some berries such as Elder. Insects such as caterpillars and aphids are crucial for the chicks. At bird tables, they enjoy sunflower hearts and peanut granules.

Roost: In autumn and winter, they gather in flocks in dense bushes; otherwise they roost in the nest.

Breeding: In the colony, nest entrances need to be at least 30cm apart. They prefer to nest in a hole in a building or nest box, preferably 3m up or more, but sometimes build free-standing domes in trees and climbers made of woven dry grasses. They fill nest holes with hay, too, and line the nest with hair, wool and feathers, and with aromatic leaves to ward off parasites. They raise two, three or even four broods. The three to five eggs in each clutch are laid April–August and are incubated for 11–14 days. The young fledge after 11–19 days.

So… Put up several nest boxes (with 32mm diameter holes) a couple of metres apart from each other, keep supplementary feeding year-round and provide nesting materials. But above all, fill the garden with insects: plant a hedge and deciduous shrubs, have a vegetable patch, don’t use chemicals... whatever it takes!

They may not be colourful, but there is something endearing about House Sparrows that perhaps we only appreciate now that their numbers are so depleted.

Starling

Sturnus vulgaris

Only now that its populations have plummeted do we fully appreciate the Starling’s full-on personality and star-studded plumage. This is a red-listed bird in need of help.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Abundant but declining resident throughout most of the British Isles, with numbers boosted in winter by birds from the Low Countries, the Baltic States and Scandinavia.

Habitat: Found in many habitats wherever there are nesting holes and grassland but especially on farmland and in gardens. Tends to avoid mountains.

Habits: Highly gregarious, hyperactive and curious, they often pick around livestock or flock with thrushes and Lapwings. They also like to bathe communally.

Food: In summer, they seek insects such as leatherjackets, beetles, flies and flying ants, plus worms. In autumn, they gorge on fruit and seeds such as elderberries and cereal grains. At bird tables, they take bread, sunflower hearts, fat, pastry, etc and can hang at feeders.

Roost: Famous for large winter ‘murmurations’, with astonishing synchronised flock manoeuvres, prior to roosting in reedbeds, conifers (including cypresses), on building ledges and seaside piers.

Breeding: They breed in a loose colony, each pair defending its nest. The colony feeds over an area of 10–80ha. They nest high up in a hole, mainly in buildings, but also in trees, cliffs, and in larger nest boxes with a 45mm entrance hole. Inside they make a robust cup of twigs and grasses lined with hair, wool and fresh leaves. They raise one to two broods. The three to six eggs in each clutch are laid April–May and are incubated for 11–15 days. The young fledge 21 days after hatching and are independent 10–12 days later.

So… On top of supplementary feeding, provide an insect-rich lawn, an Elder tree and a fruit tree, and why not put up Starling nest boxes?

Starlings find much of their food by probing in short grass, taking time out to preen and sing communally in trees and on overhead wires.

Chaffinch

Fringilla coelebs

A colourful and cheerful finch, usually top of the Big Garden Birdwatch charts in Scotland.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Abundant resident throughout almost all of the British Isles, with many more coming from Scandinavia in winter.

Habitat: In the breeding season, found wherever there are trees and bushes, but they really like a spread of big mature trees with lots of shrubs, and so do best in open woodlands and larger gardens. In winter, migrants will rove more widely on farmland.

Habits: A sometimes approachable bird, usually in small numbers in gardens, but larger flocks can build up in winter, especially on farmland.

Food: In winter, takes seeds of all sorts from the ground, including from cereals and grasses, the cabbage family and goosefoots. In summer, they are mainly insect eaters, taking aphids and caterpillars, and fly-catching in the trees. They are not very agile at feeders, preferring an open table or the ground, where they take sunflower seeds, rape seeds and linseed.

Roost: Alone, in a thick evergreen or thorn bush.

Breeding: The male defends a territory of 1ha or less but happily feeds outside it. The nest site is in a tree fork or out on a branch, most over 2m up and in a sunny spot. The neat, deep nest is a camouflaged cup of mosses and lichens, bound with spiders’ webs and lined with feathers and hair. They raise one, sometimes two broods. The four to six eggs in each clutch are laid late April–June and incubated for 10–16 days. The young fledge 11–18 days after hatching.

So… A typical large garden, with a mature tree or two, a shrubbery and well-stocked bird table, suits them very well. If that ‘mature tree or two’ can become three or four, and if you can grow an area of seed-rich flowers, all the better.

This is a natty male in his peachy breeding attire, but the white wing markings in the dark wing are the giveaway at all times of year for male and female Chaffinches.

Greenfinch

Carduelis chloris

Once a common sight at winter bird feeders, their numbers have been ravaged by the disease trichomoniasis (see here). Your hygiene regime at feeders is critical.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found throughout most lowland areas of the British Isles, either as residents or moving short distances south and west for the winter.

Habitat: In the breeding season, they need a combination of trees and open ground rich in seeds, while in winter they sometimes move into farmland or coastal areas. Gardens suit them well.

Habits: In spring, males display in a weaving song flight above the trees, slowly beating their wings. Birds follow a daily routine visiting several feeding sites.

Food: Mainly large, hard seeds, taken from the ground, such as those of the cabbage family, cereals, docks and goosefoots. Will also eat berries including Yew, and rosehip seeds. Chicks are also fed insects, especially caterpillars, and spiders. At bird tables, they love sunflower seeds.

Roost: In winter, flocks gather at regular sites, often in dense evergreen shrubs or Ivy.

Breeding: Breeding pairs often nest in loose groups, with males defending just the area around the nest. They will travel quite a way to find food. The nest is built against a tree trunk or in the fork of a dense bush, small tree or creeper, deep in cover and often in conifers. It is a relatively large twig nest with grasses and mosses and lined with hair and feathers. They raise two broods. The four to six eggs in each clutch are laid May–July and are incubated for 11–15 days. The young fledge 14–18 days after hatching.

So… It’s especially important to keep feeders clean, and use hanging feeders where possible. Keep feeding into spring when Greenfinches struggle to find natural food. Provide roosting and nesting sites by planting a shrubbery or dense hedge of evergreens or thorns, and by growing Ivy up a wall or tree.

In winter, flocks of Greenfinches tend to sit high in trees. Then, when one bird drops down to food, the others are likely to soon follow.

Wren

Troglodytes troglodytes

What it lacks in size, this diminutive bird makes up for in volume. You can massively improve its fortunes in your garden by creating suitable nest sites and places to feed.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Abundant resident throughout the British Isles, only absent from uplands and open fields, but numbers are often low in gardens. Many die in cold winters.

Habitat: They prefer deciduous woodland with dense ground cover, especially along wet valleys, but are at home anywhere with tangled vegetation, rocks, log piles and thickets.

Habits: They behave rather like mice, exploring in, under and behind thick cover, rocks and logs, often near the ground.

Food: Small creepy-crawlies, especially beetles and spiders, but also bugs, small snails, flies, ants and woodlice.

Roost: Usually alone in vegetation such as Ivy, but groups may snuggle together in holes and nest boxes in cold weather.

Breeding: Males are territorial year-round, defending 0.5–2ha. Females wander blithely between males’ territories. The nest is made in a hollow against a tree trunk, in a tree fork, bramble pile or hole in a wall, often low down. It is a well-hidden domed chamber of grasses, leaves and moss lined with feathers and hair. The male makes up to a dozen and a female chooses her favourite! A male with a good territory may mate with two or more females. Each female raises two broods. The five to eight eggs in each clutch are laid April–July and incubated for 12–20 days. The young fledge 14–19 days after hatching.

So… You need to offer lots of possible nest sites and thousands of spiders and insects, so grow dense thickets, make several log and stick piles, plant hedges if possible, and cloak walls and fences with climbers, preferably over a trellis.

The shortest of wings and tail make nipping in and out of nooks and crannies all the easier for Wrens.

Dunnock

Prunella modularis

Dull in plumage, but not in character, this bird had an alpine origin but 200 years ago found a new home in gardens.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident and common throughout almost all of the British Isles, although scarce in the north and uplands.

Habitat: Anywhere there is dense, low cover in open habitats such as scrubby heaths, wasteland and hedgerows.

Habits: They spend much of their time on the ground, often deep in cover, hopping jerkily around and flicking their wings. They sunbathe regularly and get very excited when they meet each other. Males sing from prominent, though not high, perches.

Food: Spiders and insects such as ground beetles, weevils, earwigs, springtails, flies and caterpillars, plus worms and some weed seeds such as nettles, Yorkshire Fog grass and docks. May peck around underneath feeders and bird tables.

Roost: Alone or with a partner, 1–2m up in a dense thorny hedge.

Breeding: Each Dunnock maintains its own small territory (less than 0.5ha) overlapping with up to five others, with whom it has a complex mating system and hierarchy that would get tabloid tongues wagging. The nest is well hidden in a thick bush and is a cup of twigs, roots and leaves. They raise two to three broods. The four to six eggs in each clutch are laid March–August and are incubated for 12–13 days. The young fledge 11–12 days after hatching.

So… This is one bird where it is definitely your gardening rather than what you put on the bird table that will help. A good dense thorny shrubbery or a native hedge will work wonders and serve almost all their needs. I hate to say it, but a patch of Brambles and nettles would be good too.

The fine bill, streaky cheek and grey neck separate the Dunnock from the very similar female House Sparrow, but watch how it nervously flicks its wings constantly too.

Collared Dove

Streptopelia decaocto

This delicate dove swept dramatically across Europe in the 20th century and is now a fixture in gardens almost everywhere, although numbers may be on the wane.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Common resident throughout most lowland areas of the British Isles.

Habitat: Needs a few trees or elevated perches, plus open ground for feeding, but otherwise it’s more the availability of grain or seed that makes the difference, hence their love of farmyards and gardens.

Habits: They gather in small groups to feed on the ground. In spring, males coo monotonously from telegraph posts and high trees, and have a wing-clapping rise-and-glide display flight. They are often quite tame and a benign presence at bird tables.

Food: Mainly cereal grains, and will eat sunflower hearts at bird tables. They also eat weed seeds and a few invertebrates.

Roost: Usually in groups in dense evergreens or thorn bushes.

Breeding: A few pairs often nest within the same general area and share the same feeding sites. The nest, made of just a few sticks, is usually 2m or more up in trees, hedges and bushes, close to the trunk. They raise up to six broods a year. The two eggs in each clutch are laid March–October and incubated for 14–18 days. The young fledge at 15–19 days and are independent a week later.

So… Grow a tall hedge for nesting and provide grain-based seed at bird tables, or on the ground if safe from cats. Job done!

Collared Doves are prone to the disease trichomoniasis (see here), so keep bird tables clean.

Woodpigeon

Columba palumbus

This portly pigeon is proving to be an adaptable bird in gardens, with populations on the increase.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Abundant resident or partial migrant throughout almost all of the British Isles, although scarce in the mountains and north-west Scotland.

Habitat: Very adaptable, surviving in most places with trees, especially liking farmland with woods and spinneys, but increasingly doing well in gardens.

Habits: Gathers, often in flocks, to feed on open ground or sometimes on the woodland floor, retreating to the trees if disturbed. In the breeding season, the ‘lowing’ song is much repeated, and males display by flying steeply up, wing-clapping as they do, then stalling and gliding down.

Food: Mostly plant material, especially cereal seeds, Ivy berries, elderberries, and leaves of clovers, peas, beans and cabbages. At the bird table, they take sunflower hearts, grain, biscuits, cake… and lots of it if given the chance! They have quite a thirst too.

Roost: Tall trees with thick cover such as conifers or Ivy, using the same site each night.

Breeding: Males defend a small territory of a tree or two. The unsophisticated twig nest is built in the fork of horizontal branches in a tree or high bush. They raise one to two broods. The two eggs in each clutch are laid February–November and are incubated for 17 days. The young fledge three to five weeks after hatching.

So… Now that they have learnt to feel safe in gardens, Woodpigeons don’t need much more help. They can peck at peas, beans and cabbages in your vegetable patch, so be prepared to gently discourage them by carefully netting crops, and you can use scarecrows or dangle CDs that sparkle to startle them away.

A real success story in gardens, Woodpigeons are now commonplace in the suburbs as well as rural areas. The white neck patch and plain closed wing tell it apart from the Feral Pigeon.

Mallard

Anas platyrhynchos

What a mixed relationship the Mallard has with us, sometimes ending up in the pot, at other times living cosily alongside us and taking full advantage of our handouts.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident across almost all of the British Isles, with more birds arriving in winter from eastern Europe and Scandinavia.

Habitat: They visit large, shallow waterbodies, whether flowing slowly or still, especially if there is plenty of bankside vegetation.

Habits: Often approachable, even tame, happily waddling about on land. They frequently gather in flocks. Males chase females in flight as part of courtship.

Food: Well, where to start? Grass, waterplants, seeds (especially cereal grains), insects (midges, mayflies, etc), worms, tadpoles, fish, even carrion, plus, of course, bread, rice and other human handouts. They pick food off the ground, from the water surface, or up-end while swimming, and will feed at night.

Roost: On the water’s edge, especially on islands, by day or night.

Breeding: A wide range of well-hidden nest sites are used, from dense cover such as bramble thickets, to more open rushy clumps, the tops of pollarded willows or inside hollow trees, and they will use nesting baskets. They sometimes nest in gardens that don’t have ponds – don’t worry, they usually know what they’re doing: leave well be. The nest is a grass cup stuffed with gorgeous thick down. They raise one brood. The 9–13 eggs are laid February–October and are incubated for 27–28 days. The young leave the nest when less than a day old, but do not fly until seven to eight weeks.

So… Supplementary duck food is available and is much more nutritious than sliced bread! But don’t overfeed – duck droppings can enrich the water in ponds.

Often seen on urban park pools, the Mallard is the only duck likely to visit garden ponds, and even then only large ones.

Pheasant

Phasianus colchicus

If you live near farmland, you may get wandering Pheasants under your feeders, especially if you feed grain to other birds. However, being a released gamebird, there is little need to encourage it.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident throughout most of the British Isles (except north-western Scotland). Populations are boosted by the huge numbers released each year for shooting.

Habitat: Woodland and woodland edge, and on farmland wherever they have access to thickets. They also need a good water source.

Habits: A social bird, with males establishing a clear pecking order. They spend most of their time on the ground, scratching and digging for food, and hate flying! They rarely move more than 1km from their birthplace. Males display from an open arena, loudly crowing and ‘drumming’ their wings.

Food: All sorts, but especially cereal grains and seeds, insects (beetles, flies and their larvae, etc) and worms, and plant food such as roots, shoots and berries. They are fond of acorns and blackberries.

Roost: Usually off the ground in trees or a thicket, and may spend much time sleeping.

Breeding: The male defends a territory of 0.5–5ha. The nest site is on the ground in thick vegetation, the nest being a barely lined depression. Females raise one brood. The 8–15 eggs are laid March–June and are incubated for 23–28 days. The chicks leave the nest on the first day and can fly short distances at only 12 days, but remain with their mother for 70–80 days.

So… If you live near farmland, you may get wandering Pheasants under your feeders, especially if you provide grain. A tray of water and a dense shrubbery for them to retreat into will also help.

Refugees from the farmland where they are released, garden Pheasants can sometimes lose their natural nervousness and caution.

Grey Heron

Ardea cinerea

A tall and mighty fishing machine, only likely to be seen in larger gardens with ponds.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found across much of the British Isles. Populations crash in hard winters.

Habitat: They like all sorts of shallow water that isn’t too fast flowing, but they are surprisingly attached to trees and rarely found far from cover. They nest colonially, usually in big trees near water, so are an unlikely breeder in gardens.

Habits: Generally wary of people, they loathe coming near to buildings, but in London they are now much more tolerant and approachable.

Food: Half a kilogram of fish a day! They also take amphibians, Grass Snakes, dragonflies and small mammals. They feed alone, often at dusk and dawn but even at night, stalking or statuesque at the water’s edge, catching their prey with a lightning strike.

Roost: Will rest on the ground near feeding sites by day or night.

So… Herons rarely come into gardens, but a garden pond stuffed with goldfish or froggy snacks is clearly very tempting to a Grey Heron flying over.

Should you wish to safeguard ornamental fish in your pond, there are various means of deterring Grey Herons.

Netting the pond is the most effective method, but is unsightly.

Netting the pond is the most effective method, but is unsightly.

Scarecrows work well – with creativity, these can become a work of art.

Scarecrows work well – with creativity, these can become a work of art.

Herons like to land near water and then walk up to it, so extend two wires or ribbons all around the margin, one 20cm off the ground, the other 35cm, as a visible deterrent, not a tripwire!

Herons like to land near water and then walk up to it, so extend two wires or ribbons all around the margin, one 20cm off the ground, the other 35cm, as a visible deterrent, not a tripwire!

Placing a model heron at the pond edge is likely to draw others in, not scare them away.

Placing a model heron at the pond edge is likely to draw others in, not scare them away.

With their dagger-like bill, enviable patience, and lightning reflexes, Grey Herons are master fishers, for whom goldfish inevitably present an easy and colourful target.

Sparrowhawk

Accipiter nisus

A dashing bird of prey, this is the raptor most likely to be seen in gardens, even in cities.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Widespread resident throughout the British Isles (except north-western Scotland).

Habitat: Wooded countryside and farmland, but they cope well with urban environments.

Habits: They hunt in low dashing manoeuvres along regular flightpaths, often close to the ground, nipping over hedges and fences to surprise their prey. They will also ambush prey from a perch. Usually seen singly, they spend much of the day resting and loafing. They fly above roof height to check out potential hunting sites, and they will circle high in spring to display.

Food: Birds, with the smaller male taking sparrows, buntings, tits and finches, and the female preferring thrushes, Starlings and doves but even taking Woodpigeons.

Roost: Alone in a tree, changing sites regularly.

Breeding: They hunt over an area of 1,000–5,000 hectares but defend a much smaller area for nesting. The simple stick platform nests are hidden high in conifers or large thorn bushes. They raise one brood. The four to six eggs are laid May–June and are incubated for 39–42 days. The young fledge after 24–30 days and are independent 20–30 days later.

So… Some people enjoy seeing them in gardens; others find it distressing. You can make things a bit more challenging for them by regularly changing the location of bird feeders, but remember that the presence of a top predator is always the sign of a healthy food chain and environment.

Sparrowhawks, with their orange eyes and barred underparts, can sometimes give fantastic close-up views in gardens – a mini-Tiger at work in our backyard jungles.

Kestrel

Falco tinnunculus

A rare garden visitor, this fabulous little falcon is famed for its precision-hovering over road verges, but its numbers are dwindling.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident or short-distance migrant across almost all of the British Isles.

Habitat: Open grasslands, such as downland and moorland, motorway verges and meadows. They also need safe perching places. A few pairs have adapted to city life.

Habits: Usually seen alone, they hover a few metres above the ground, sometimes beating their wings, sometimes just riding an updraught. They then plunge to the ground after prey. They sit for long periods upright on prominent perches such as tall buildings, telegraph posts, lamp-posts, bare trees and large rocks, and often choose to hunt in low light.

Food: Mainly voles, plus small mammals such as Wood Mice and a few beetles and other invertebrates. In urban areas, they will target small birds such as House Sparrows and Starlings.

Roost: In trees, on a cliff or on a building.

Breeding: Defends a small area around the nest, which is either an old Crow’s nest or a rudimentary cup of twigs and grasses on a building ledge, in a nook in a cliff or in a nest box. They raise a single brood. The three to six eggs are laid April–June and are incubated for 27–29 days. The young fledge after 27–32 days but are not independent for at least another month.

So… Not easy to help in the garden, and if you encourage Kestrels in urban areas they will probably feed on garden birds. But if you have the space in a rural garden, turn lawns into meadows so that voles can thrive and then wait for the ‘windhover’ to come.

While often confused with the Sparrowhawk, the Kestrel’s hovering behaviour and love of open spaces and elevated vantage points is as much a giveaway as any plumage feature.

Moorhen

Gallinula chloropus

The easiest waterbird to cater for, whose families will keep you soundly entertained if you can give them a big enough pond to play in.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: In lowland areas throughout the UK, wherever there are suitable bodies of water.

Habitat: Sheltered lowland pools, lakes, streams, ditches and rivers, including urban parks. They like at least some open water, so a tiny garden pond isn’t enough. They also need abundant aquatic plants and thick cover at the pond margins.

Habits: They usually live in pairs or family groups, spending most of their time either sculling jerkily across the water looking for food or clambering through vegetation at the water’s edge. They sometimes potter about on land, never straying too far from the edge.

Food: A mix of plant material, mainly aquatic, such as duckweed, pondweed, rushes, leaves, seeds and fruit, plus some invertebrates such as molluscs, worms, spiders and tadpoles, and even carrion. They will peck at seed under bird tables.

Roost: In trees or in dense aquatic vegetation.

Breeding: A pair defends a linear territory along the water’s edge, in which they breed and feed. Their nests are cups of twigs and stems lined with grasses and reed leaves, and are made in amongst dense pond plants or on a floating platform, or occasionally in waterside trees. They raise two to three broods. The five to nine eggs in each clutch are laid April–June and are incubated for three weeks. The young fledge at six to seven weeks.

So… Even though Moorhens don’t need a huge lake, only a few of us have enough space for a large enough pond to fully satisfy them. However, you may live close to a ditch, canal or river, in which case a well-vegetated pond may become a nice addition to their territory, and they may even breed there.

On city pools, Moorhens can become quite tame, but in rural areas they often remain shy and will scarper for cover – and even submerge – at the first sign of danger.

Black-headed Gull

Larus ridibundus

This relatively dainty gull (compared to the robust Herring Gull) is familiar from sports fields and the seaside, and is a winter drop-in visitor to a few gardens.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Breeds across the British Isles but in a relatively small number of often large colonies in protected wetlands. In winter, they are much more widespread.

Habitat: In summer they are found on saltmarshes, shallow lakes and gravel pits. In winter, they are more catholic, visiting coasts, estuaries, gravel pits, reservoirs, urban park lakes, rubbish tips, playing fields and arable farmland, but only a few gardens.

Habits: A gregarious gull, often gathering by day to preen and bathe. They only come into gardens to scavenge kitchen scraps.

Food: They take mainly worms and insects, following the plough avidly. They also snatch food from the water surface or by shallow plunge-diving. They will circle high to take flying ants in summer.

Roost: In large flocks at sea, on estuaries and reservoirs.

So… Encouraging them into gardens by providing food may attract larger gulls and is probably best avoided.

The Black-headed only retains a dark smudge behind its eye in winter, but the small build, red bill and red legs should give it away.

Herring Gull

Larus argentatus

The archetypal seagull, included in any child’s drawing of the seaside, but now unfortunately sometimes coming into conflict with people as its breeding habits change.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: In the breeding season they are found around much of our coast, although increasingly in cities; they travel widely inland in winter.

Habitat: They once bred predominantly on seacliffs but have undergone massive declines there. The rapid rise in rooftop populations, mainly in coastal towns, has not offset these losses. In winter, they are regular on beaches, rubbish tips, estuaries, sports fields and farmland.

Habits: A large, rather imposing and very gregarious gull, often loud and sometimes quite fearless of people. They make long feeding flights of up to 50km to find food. Problems can arise when pairs are nesting, including noise, fouling and ripping open rubbish bags. Also, if you stray near their eggs or chicks they see it as a threat and can dive-bomb to try to frighten us away. They generally avoid actual contact, but if people cower rather than fending them off, they can be bold enough to have a peck.

Food: Almost everything! They eat dead fish, shellfish and crabs on the tideline and at sea, but they are very adaptable and follow the plough for worms, scavenge fish offal in ports and grab human rubbish in the street, on beaches, in gardens and at dumps. They often harry and rob other gulls. But they don’t eat bird seed or cling to feeders.

Roost: Outside the breeding season, many travel each evening to spend the night on reservoirs or the sea.

Breeding: They form large loose colonies on cliffs or rooftops. They especially like flat roofs, or will wedge their nest, made of grass, moss and seaweed, behind or between chimneys. They lay one brood of two to four eggs April–June, incubated for 28–30 days. The young fledge after 35–40 days.

So… Nationally, this is a declining bird that most certainly shouldn’t be vilified. However, when gulls come into conflict with people, neither side wins. Do not feed them and use peck-proof bin-bags or put rubbish out in a closed bin. Restrict yourself to feeding bird seed in feeders for smaller birds.

If gulls are a problem on your property or you want to deter them from nesting, the only sustainable solution is to block potential nest sites. Use netting or anti-bird spikes, but do it in winter and not when the birds are actually nesting; remember breeding birds are protected by law.

The Herring Gull has a bill capable of ripping into unguarded bin bags, and has taken readily to nesting on roofs, which mimic its original cliff top home.

Feral Pigeon

Columba livia

Its ancestors may have been wild Rock Doves living on cliffs, but our high-street pigeons are escaped or lost domestic pigeons and their descendants.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Common and sedentary resident throughout most urban and coastal areas.

Habitat: They need tall buildings or cliffs to perch and nest on, plus a source of fresh water. They especially like abandoned buildings, railway stations, under bridges and big public buildings.

Habits: They loaf in flocks on roofs, wheeling down to the ground to feed. In parks and city squares they can become incredibly tame, strutting and cooing around our feet.

Food: They probably eat more human food than natural, enjoying everything from bread and chips to cheese, and feeding all night in well-lit areas. At bird tables they take most scraps and birdseed.

Roost: Under cover high on buildings.

Breeding: Can breed when less than a year old. They nest in loose colonies on ledges and in nooks and crannies, usually preferring elevated sites and building a rough cup of stems and roots. They raise five or more broods a year. The two eggs in each clutch are laid mainly February–November (but have been recorded in every month) and are incubated for 16–19 days. The young fledge at 25–35 days and are attended by their parents for up to another ten days.

So… Some people in urban areas, who see little other wildlife, are fond of pigeons; those who have to deal with their fouling of buildings, pavements and public places are not so keen. In gardens, they can provoke disputes between neighbours, so it is usually best not to encourage them. If so, use bird feeders that exclude pigeons and keep them out of potential nesting areas with netting as long as you are sure they are not nesting at the time.

Any Feral Pigeon without a metal ring on its leg is likely to have been raised in the wild; those with rings are ones lost by their owner.

Rose-ringed Parakeet

Psittacula krameri

This noisy, in-your-face, bright-green parrot looks set to stay – and spread. Urban myths surround its introduction – were they off the set of The African Queen, or escapees from Jimi Hendrix parties? Whatever the reason, numbers are booming.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: This introduced species is found mainly in the London area, but is expanding into north Kent, Berkshire and Surrey. Another small population is well-established in south-east Kent.

Habitat: Although originally a tropical species, they are doing fine in urban and suburban gardens and parks, but need tall trees with nesting holes.

Habits: They travel widely during the day to look for food, often in groups, and rarely descending from the trees. Often very noisy, their squawk can be piercing.

Food: Largely fruits (apples, pears, grapes, etc), berries, cereal grains, seeds and nuts, but also flower buds and nectar. They readily take peanuts and seed mixes at bird tables.

Roost: In winter, they make long journeys daily to communal tree roosts where several thousand birds can gather. In the breeding season, they roost in or near their nest.

Breeding: Loosely colonial, a pair just defends their nest hole, which is either an old woodpecker hole or a natural one lined with just a few wood shavings. There is a single brood. The three to four eggs are laid January–June and incubated for 22–24 days, the young fledging at 40–50 days.

So… Be aware of the potential problems – as well as their noise and boisterous behaviour at bird feeders, they can strip fruit trees, and there are concerns that they may oust native hole-nesting species such as Starlings. Use feeder guards if you want to keep them from food.

Parakeets are relatively dominant birds at the bird table, with a powerful hooked bill to boot.

Barn Owl

Tyto alba

Usually seen as a pale ghost in the half-light or headlights as it floats along verges and hedgerows, it’s hard to find a bird with more charisma.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident if very scarce throughout most lowland areas of the British Isles, although a rarity in Scotland.

Habitat: Mainly farmland with scattered hedges, trees and small woods, especially where there are ample rough verges, margins and unimproved pasture. Often found on the edges of villages but not in urban areas. In gardens, rare in all but the largest.

Habits: They head out at dusk to hunt alone, slowly quartering grassy areas a couple of metres above the ground, hovering if something catches their eye (or ear). They sometimes pause for a while on the ground or a fence post. The screech call of the male is chilling.

Food: Small mammals, especially voles and mice, plus a few birds and amphibians.

Roost: By day in an undisturbed dark hideaway in barns and ruins, occasionally in bushes.

Breeding: A pair maintains a territory throughout the year of 40–250ha. They nest in a dark hole, often in a barn or ready-made nest box, sometimes in a cliff or quarry, but they need a big, flat floorspace. No nest is created within the hole. There is one brood, exceptionally two. The four to seven eggs in each clutch are laid April–August and are incubated for 30–31 days. The young fledge at 50–55 days and are independent a month later.

So… If you have a small garden, there’s unfortunately little you can do. If you have a large rural garden, create a meadow; it will only provide a small part of their huge hunting territories but that could be critical. Barn Owl nest sites are often in short supply, so if you have the chance, erect a box either in an outbuilding or on a pole in an undisturbed part of the garden, facing east, north-east or south-east.

Occasionally seen as a ghost in the headlights, the Barn Owl is almost white underneath, and has a fearsome screaming call. Populations are still perilously low, so help them if you can.

Tawny Owl

Strix aluco

Rarely seen but often heard, this is the hooting owl that kids like to mimic. It’s a surprisingly frequent visitor to gardens with large trees, even in urban areas.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident across much of Britain, even to some altitude, but absent from Ireland.

Habitat: They need mature trees in woods, copses, churchyards, parks and large gardens.

Habits: They hunt almost exclusively at night, either in flight or from an elevated perch. Their short wings allow them to twist and turn, and they will plunge into bushes to catch roosting birds. Males mainly call in late autumn and spring. Can be highly aggressive at the nest.

Food: Small mammals and small birds such as sparrows, Starlings, thrushes and doves. Also amphibians, young Moles, plus some beetles, worms and even fish.

Roost: By day on a high branch, often up against the trunk; sometimes in holes. A pair will roost together in winter.

Breeding: A pair holds a territory all year, which can be as small as 5ha but usually 10–100ha. Many don’t breed every year. When they do it is usually in a tree hole, or occasionally in a special nest box. There is a single brood, the two to four eggs being laid March–May and incubated for 28–30 days. The young fledge at 25–30 days, clambering from the nest when still down-covered, and are independent a month later.

So… If you increase the number of smaller birds and mammals in your garden, Tawny Owls will benefit, although be cautious about encouraging them to breed due to their aggressive nature.

A master of camouflage in its daytime tree roost, many a time you will have been watched by a Tawny Owl without you knowing a thing about it.

Swift

Apus apus

If you live several storeys up, you are particularly well-placed to help these aerial masters and address their chronic shortage of nest sites and population decline. You may be rewarded by their exuberant screaming chases over the rooftops.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: In summer, found across most of the British Isles.

Habitat: Uninterrupted airspace with insects. They come to land only to nest on cliffs and the human equivalent, tall buildings.

Habits: They arrive back from Africa in May and leave by early August, and have a lot to pack in to their three months here. They fly in loose flocks at a great height and for huge distances, chasing the best weather, and courting, mating and sleeping on the wing. When visiting their nest, which must have a clear flight line to it, they take several approaches to make a successful landing. Once inside, they can only shuffle about on their tiny legs.

Food: Flying insects and wind-borne spiders, but they avoid bees and wasps. Adults collect a ball of insect pulp in their throat to bring back to the young.

Roost: High in the sky most of the year, but in the nest through the breeding season.

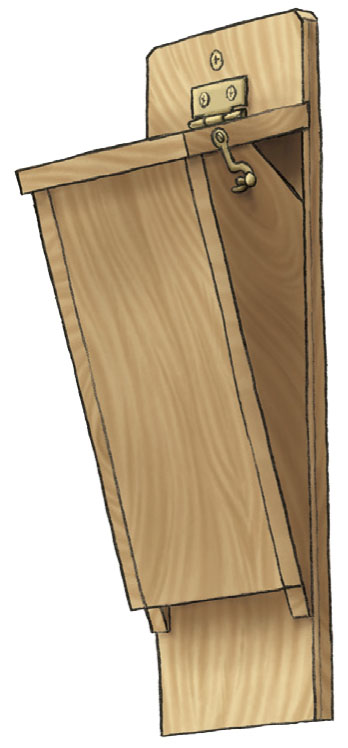

Breeding: They nest colonially, up to a few dozen pairs in the local area. They mainly use flat internal roof spaces in old buildings or special Swift nest boxes, returning to the same site each year and making a modest nest cup of feathers and saliva. They raise a single brood. The one to four eggs are laid in June and incubated for 18–24 days, the young fledging after 37–56 days.

So… If you have a house wall where a Swift box can be placed, preferably under the eaves on the second storey or higher, it is sorely needed (see here). Maybe there is somewhere suitable at your workplace too. Playing tapes of Swift calls in May to attract them increases your chances of success.

Let the RSPB know where you see Swifts flying low over houses in summer – we would like know to build up a better picture of where they are surviving.

Green Woodpecker

Picus viridis

It’s a thrill if this charismatic joker, moss-green with a bold red cap and highwayman’s mask, comes hopping about your lawn.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Localised resident throughout the British lowlands; absent from the far north of Scotland and from Ireland.

Habitat: Open deciduous woodland, parkland and orchards, with unimproved grassy areas.

Habits: They seek ants in warm grassy banks and in trees, and can be rather nervous, fleeing with a characteristic bounding flight and ‘yaffling’ call.

Food: Ants and their grubs are vital, licked up using their very long, sticky and sharp-tipped tongues. They will take other insects where available, including from behind bark.

Roost: In a tree hole.

Breeding: A pair defends a territory of 30–100ha. The nest is an unlined hole in a tree 30–50cm deep, the entrance 6cm wide; they either excavate their own or reuse an existing site. Each pair raises a single brood, the five to seven eggs being laid April–July and incubated for 17–19 days. The young fledge after three to four weeks.

So… You’ll be hard pushed to encourage them into small or urban gardens, but if you live in the country or near suitable habitat, keep those lawns chemical free, boost your ant population and retain dead standing trees where possible. It is also worth trying a large nest box – although they may modify the box a bit for you!

A woodpecker on a lawn may seem incongruous, but this is prime habitat for the Green Woodpecker, an ant-licking specialist.

Great Spotted Woodpecker

Dendrocopos major

The commonest woodpecker in gardens, but each visit is still exciting. It’s quite easy to draw them onto your feeders, but your challenge is to fulfil even more of their needs.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident or short-distance migrant throughout Britain, but rare wherever trees are scarce. Very rare in Ireland.

Habitat: They like plenty of good-sized trees, especially a mix of deciduous and conifers.

Habits: They spend most of their time shimmying up branches and hammering out insects from the bark. They can cling well to bird feeders, but are often wary. Males drum in spring to attract a mate, often on resonant wood but sometimes on a telegraph post.

Food: Insects found in trees throughout the year. In autumn and winter, they take seeds from pine, spruce and Larch cones, and the fruit/nuts of Hazel, Hornbean, Beech and oak trees. At bird feeders they like peanuts, sunflower hearts and fat. They will take some bird eggs and nestlings in spring.

Roost: In an old hole or large nest box.

Breeding: The breeding territory is small, but they feed over a wider area. They hammer out a nest hole 3–5m off the ground in a dead or dying tree, often using the same one year after year. The entrance is 5–6cm wide and the chamber 30cm deep. They raise one brood. The four to seven eggs are laid April–July and are incubated for 10–13 days, with the young fledging 20–24 days after hatching.

So… Bird feeders are the easiest way to try to get regular visits. In addition, leave dead standing timber wherever possible (a real rarity in gardens) and, for the long term, plant suitable tree species, especially birches.

A Starling-sized black-and-white woodpecker with a big blob of white on the wing is the Great Spotted. The sparrow-sized Lesser Spotted is now very rare.

Swallow

Hirundo rustica

A bird that country folk will know well and city dwellers almost never see – if you are visited by these harbingers of spring, treasure them.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Summer visitor from sub-Saharan Africa (and even South Africa) to most of the British Isles.

Habitat: Mainly farmland, often near water, and avoiding woods, uplands and urban areas.

Habits: They arrive here in April and May, and fly low and fast over grassy fields, especially around cattle and horses or over water. They only land on the ground to collect nesting materials. They are gregarious outside the breeding season, mixing with martins and gathering on wires. On migration, thousands pass along the coast, departing south in September and October.

Food: Flying insects, especially flies, plus flying ants, aphids and others.

Roost: In the breeding season, they roost in the nest or nearby. On migration, they drop into reedbeds, tall grasses and maize fields to spend the night.

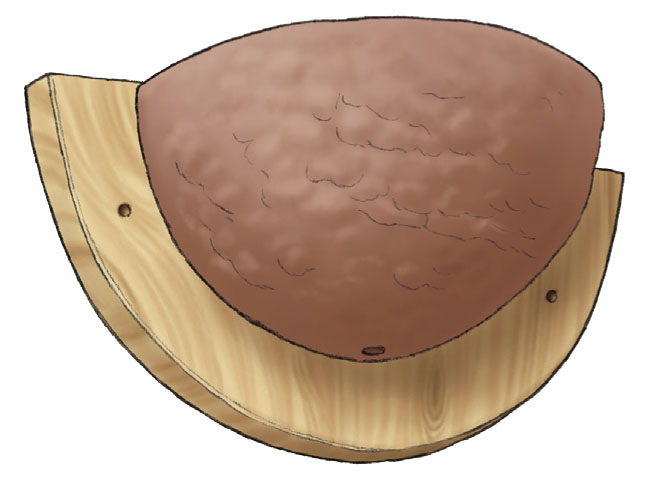

Breeding: They often nest in small colonies, just a handful of pairs, with many returning to the same site each year. The nest is almost always in an open building such as a barn, stable, outbuilding or porch on a beam, ledge or shelf, and is a half-cup of mud and straw, lined with feathers. They raise two to three broods. The four to five eggs in each clutch are laid May–August and are incubated for 11–19 days. The young fledge 18–23 days after hatching.

So… If you live near open pasture, offer them a suitable nest site by leaving a barn window or outhouse door open. You will hopefully be rewarded with loyal repeat guests.

Swallows have a red face and deep blue throat band, unlike the House Martin which has a plain white underside and white rump.

House Martin

Delichon urbica

To have House Martins nesting under the eaves was one of my childhood joys – their gentle night-time chatter just outside the window is a comforting sound of summer.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: In summer, found throughout most of the British Isles, although numbers have fallen considerably. They migrate to Africa for the winter, although exactly where they go is poorly known.

Habitat: Birds of the air, they zip about high in the sky and only come down to earth to breed, collect nesting materials and drink. They are most frequent over habitation and areas of water.

Habits: They arrive in April and May, and spend much time flying around in loose flocks catching insects, only coming low if chilly weather forces insects down. Mud for their nests is collected from the ground. In autumn, large numbers pass along the coast and gather on wires, with most having left by early October.

Food: High-flying insects, especially flies and aphids but also beetles and flying ants, brought to their young in sticky blobs – lucky them!

Roost: Usually in the nest, arriving after dark, but some may sleep on the wing. On migration they will roost in the nests of other House Martins.

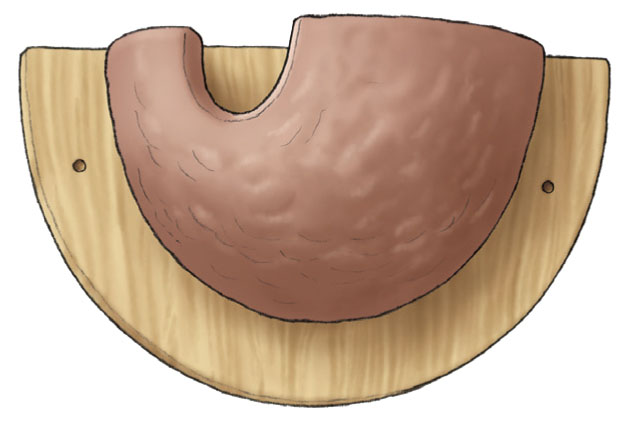

Breeding: They nest in colonies, most fewer than five pairs but some of several hundred. They build a virtuoso nest of 1,000 pellets of mud, lined with a few feathers, usually on buildings or bridges and at least 3m up on a vertical wall under the eaves. Pairs will reuse and repair the previous year’s nest. They raise one to three broods. The three to five eggs in each clutch are laid May–August and incubated for 14–16 days. The young fledge 22–32 days after hatching.

So… If you have a high wall with eaves, put up an artificial nest. If one pair finds it, others will probably build alongside. Be prepared to wipe up droppings from the window sills beneath the nests, but it is a small price to pay for their company. Why not create a mud puddle for them on open ground too?

House Martins need to be able to swoop up to their nest at speed and without hindrance – few will nest under the eaves of a bungalow, or where there are trees nearby.

Pied Wagtail

Motacilla alba

Rather energetic and restless, this is more a bird of driveways and roadside gutters than back gardens, but there’s the chance you may be able to help it nest.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident throughout most of the British Isles, but they are only a summer visitor to higher ground and northern Scotland.

Habitat: Likes open places, often by still or slow-moving water such as lakes and canals. Also regular wherever the ground is bare or freshly turned, where vegetation is very short, or where flies are abundant, such as closely grazed pasture, ploughed earth, playing fields, seashores, sewage farms and farmyards. Around gardens, they visit large lawns, roads, roofs, car parks and paved areas.

Habits: They walk and run across the ground, chasing small insects or picking them from the surface, their tail wagging relentlessly. They rarely perch in trees by day and are often quite tame.

Food: Mainly flies such as midges and craneflies, plus some beetles and aquatic insect larvae. They take a few seeds, especially in winter, so will scavenge under bird tables for fragments.

Roost: In the breeding season, they roost alone in their territory. In winter, they gather in large flocks in reedbeds, high-street trees and supermarket roofs, travelling many kilometres each evening to join the throng.

Breeding: A pair defends a territory of at least 3ha. They nest in holes or crevices, often in stone buildings or walls, frequently close to ground level. Their nests are cups of twigs and grasses, lined with soft feathers and wool. They raise one to three broods. The four to six eggs in each clutch are laid April–July and are incubated for 11–16 days. The young fledge 11–16 days after hatching.

So… A mown lawn and sunny bare-edged pond may prompt them to visit, but they will still probably prefer to spend time on your drive! If you are fortunate enough for them to be regular, you might try an open-fronted nest box to entice a pair to breed.

The fine bill of the Pied Wagtail gives away the insect-eating lifestyle, and the horizontal carriage is the mark of a runner, not a tree climber.

Grey Wagtail

Motacilla cinerea

Even longer and waggier-tailed than the Pied Wagtail, this denizen of fast water can sometimes stray into gardens in winter.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found sparsely throughout much of the British Isles where they are residents or short-distance migrants.

Habitat: In the breeding season they are tied to fast-flowing streams where the water churns over rocks and weirs, especially those in wooded valleys with gravel bottoms and boulder-strewn margins. Some move into more lowland and even urban areas in winter but still near water.

Habits: As with the Pied, they hop, skip and jump along the water’s edge. They can hover, and for a bird with such a long tail, they make surprisingly agile flying sorties after insects.

Food: All sorts of insects from damselflies to mayflies to midges, plus caddis flies and their larvae.

Roost: In winter they gather in small flocks, often in reedbeds.

Breeding: Few breed in gardens. Territories follow the course of a river, with most nests made in traditional sites next to water in bankside holes, cracks and crevices.

So… If you are fortunate to live alongside a stream, you may be visited regularly. For the rest of us, try a large garden pond with open stony margins and a bubbling water feature.

In winter, when most Grey Wagtails are seen in gardens, they have lost their bright yellow underparts and black chin, but the yellow under the extra-long tail should give them away.

Waxwing

Bombycilla garrulus

What a bird! So elegant, so unpredictable – everyone wants a visit from a flock of these elusive northern wanderers.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: They breed no closer than northern Scandinavia, but each winter they push south and west, reaching Britain annually, especially eastern counties. Numbers vary from almost none in some years to thousands in others.

Habitat: In winter, most likely to be seen in urban environments, from housing estates to supermarket car parks.

Habits: They are very gregarious in winter, their strange, high, bell-like call drawing in other Waxwings as they rove nomadically, almost desperately, in search of food. They often perch high in trees, and then zoom off to converge on berry-laden trees and bushes.

Food: They are berry and soft-fruit specialists, gorging on twice their body weight a day, with most food taken from a tree rather than the ground. Rowan berries are a favourite, but by the time they arrive in the UK few are left for them. Hawthorn berries (haws), crab apples, rosehips and almost any other berry are all taken avidly.

Roost: In trees.

So… There are so many other advantages of growing berry-bearing trees that you might as well go for it and plant as many as your garden will allow in the hope that one day you will be lucky.

What a bird! With its wild crest, apricot-coloured suit and heavy eyeliner, if you attract a winter troupe of Waxwings you will be the envy of your neighbourhood.

Black Redstart

Phoenicurus ochruros

A perky little fella, like a soot-coloured Robin, this UK rarity has a curious penchant for rooftops and industrial landscapes.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: A scarce migrant and winter visitor to English east and south coasts, with a few breeding in south-eastern England and the Midlands.

Habitat: They like rather dry, barren, stony places, avoiding trees, wetlands and lush vegetation, and have adapted well to rooftops. In winter in England, they visit undercliffs, coastal harbours and warehouses, while in summer they are found around factories, power stations and urban ‘green’ roofs. They made use of bombsites after the Second World War.

Habits: They hop and run over rocks and roof tiles, dashing to grab insects, quivering their rufous-tinged tail. One bird often remains faithful to a small feeding area. Males sing from elevated vantage points such as gable ends.

Food: Insects, such as beetles, ants, bugs and grasshoppers, plus spiders. They also take some berries and a few seeds.

Roost: Hole in a cliff or building.

Breeding: The territory can be as small as 0.5ha but up to about 5ha. The nest is built in a hole in a building, rock face or nest box. It is a cup of moss, leaves and plant stems, lined with softer material. They usually raise two broods. The five eggs in each clutch are laid May–June and incubated for 13–17 days. The young fledge 12–19 days after hatching but a family may stick together for several more weeks.

So… This is one species you are more likely to see on a summer European holiday, whereas in England you are very lucky if they visit your garden. However, if you live or work in an urban location in an area known for them and you have the chance to influence the development of ‘green’ roofs, they are the best way of helping this unusual bird.

A bit of a continental speciality, a few urban or coastal rooftops in Britain play host to this sooty little bird with a russet tail that it likes to shimmy repeatedly.

Fieldfare

Turdus pilaris

Bold and noisy, this attractive thrush with its exuberant ‘chack chack’ call is one of the evocative wild sounds of winter.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: A winter visitor in large numbers, wandering nomadically throughout the British Isles.

Habitat: In winter, they like open farmland, preferably with grassland but also use stubble fields, and they are regular in orchards. They often perch in spinneys and tall hedgerow trees.

Habits: In winter, they travel around the countryside in flocks sometimes several hundred strong, stopping in one area for a while, then moving on. They feed mainly on the ground, hopping about boldly, often with Redwings and sometimes Starlings, dashing to the refuge of trees and bushes if alarmed. In gardens, we see them most often in hard weather when hunger overrides nervousness.

Food: Insects, worms, slugs, berries and fruit. They are particularly fond of haws.

Roost: In flocks in thorny thickets, hedges and young conifer plantations.

So… When hard frosts come, put a few halved apples out on an open lawn not too close to cover and watch for these perky thrushes to arrive. If you have room to grow a Hawthorn, get planting!

It is often in the coldest weather that, with a few judiciously placed apples, we get our best chance to see Fieldfares in back gardens. Listen for the loud ‘chacking’ call.

Song Thrush

Turdus philomelos

Not too long ago, there were more Song Thrushes than Blackbirds in gardens. Not so now, so this rather reticent master-songster needs our help.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident throughout almost all of the British Isles, with more arriving in winter from northern and eastern Europe. Some British birds migrate south in winter.

Habitat: They need trees and bushes with grassy areas, damp soils and leaf-litter, so they enjoy woods, parks, churchyards and gardens.

Habits: They search for food, usually alone, close to the cover of bushes, hopping and then pausing to listen, and often flicking over leaves. The males’ resonant, creative songs are delivered from a high vantage point.

Food: Markedly seasonal diet, taking worms in winter, caterpillars, beetles and other insects in summer, snails in late summer, and then fruit and berries in autumn such as currants, blackberries and elderberries. Snails are beaten against a favourite rock (‘anvil’) to extract the flesh.

Roost: Thick bush, usually on their own or in a pair.

Breeding: Each nesting territory can be as small as 0.2ha, but they will feed outside of that. The nest is built on a branch close to the trunk of a tree or shrub, in creepers against a wall, or sometimes in thick cover near the ground. It is a well-made cup of twigs, grass and moss, lined with a smoothed plaster of mud, dung and woodchips. They raise two to three broods. The three to five eggs in each clutch are laid March–August and incubated for 10–17 days. The young fledge 11–17 days after hatching.

So… Give them a garden full of worms, don’t kill your snails, plant some berry bushes or a mixed hedge, and don’t sweep up all that leaf-litter. If you can really enhance those nice moist and shady conditions, you have a good chance of enticing a pair to stay.

Song Thrushes tend to winter in the same areas each year, so one in your garden one year may be the same you see the next.

Redwing

Turdus iliacus

A delicate winter thrush from Scandinavia and beyond, rarely seen in gardens until freezing weather strikes.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: A winter visitor across most of the British Isles.

Habitat: During winter, they visit grassy fields, preferably with nearby cover such as hedges and woodland edges, and they also rootle among leaf-litter. Berry-rich hedges are favoured, and they will abandon inhibitions and come into parks and gardens in harsh conditions.

Habits: Large flocks arrive by night in October and November when their thin ‘seee’ calls can be heard overhead. They rove around the countryside looking for good feeding sites, moving either when the weather changes or the food is exhausted. They usually feed on the ground, hopping and stopping across short turf, although they quickly fly into cover if disturbed.

Food: On arrival in autumn, they will gorge on berries and other fruit, in particular haws, but much of their time is spent looking for ground invertebrates such as beetles and their larvae, caterpillars, worms and snails.

Roost: In dense cover, such as evergreens, thorny thickets or dense woodland.

So… Be ready when cold weather comes to put out windfall apples on the lawn. If you have space for a Hawthorn or Rowan – or several – then there is every chance that your resident Blackbirds may leave a few berries for them.

The pale stripe over the eye and the ‘bleeding’ side separate the delightful Redwing from the similar Song Thrush.

Mistle Thrush

Turdus viscivorus

This is the thrush with a football rattle call and a song that can be heard for miles. You’ll need a big lawn and tall trees to keep this one happy!

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident throughout almost all of the British Isles, although rarely in large numbers.

Habitat: They need tall trees and large expanses of open, closely cropped natural turf, so they enjoy parkland and the grounds of country homes, orchards and a few large gardens. They also require berry-bearing trees in winter.

Habits: They hop purposefully across open short turf, chest out. Usually the only gatherings are of small flocks in autumn. The male sings early in the year, even in storms (hence the country name, ‘Stormcock’), from the tops of tall trees. Pairs will guard favourite berry trees from all-comers in winter.

Food: Invertebrates through much of the year, especially beetles but also worms, slugs and flies. Favoured berries include Yew, Rowan, Ivy, Mistletoe, Purging Buckthorn and Holly.

Roost: In trees and bushes, often high up in evergreens.

Breeding: They defend a relatively small territory of 1–15ha, but feed over a large area in which other pairs may nest. The nest is built very high up on a thick tree branch, sometimes in a conifer, and is a large cup of twigs, moss and mud, lined with plenty of dry grasses. They raise two, sometimes three broods. The three to five eggs in each clutch are laid March–June and are incubated for 12–15 days. The young fledge 14–16 days after hatching.

So… Those of you with large lawns have the best chance of success, as long as they are rich in beetles. If you live anywhere near open meadows, parks or sports fields, you too can hope for a visit, so consider growing a fine Holly or Rowan on your boundary so that a pair may come to claim it.

Notice how the breast spots on the Mistle Thrush are round on a white background, compared with teardrops on buff of the Song Thrush. It is unusual to see this larger cousin of the Song Thrush in small gardens.

Blackcap

Sylvia atricapilla

A warbler that comes to bird tables? It’s a strange modern phenomenon from this curiously adaptable little insect-eater.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Common and increasing summer visitor to much of southern Britain; scarce but increasing in Ireland and Scotland. Some birds that breed in central Europe winter in southern Britain.

Habitat: In summer, a bird of mature deciduous woodland, rare but getting more frequent in large gardens. However, wintering birds in Britain are regularly seen in suburban gardens, especially in the south and west, and migrants turn up in many coastal gardens.

Habits: In summer, they spend much of their time in the treetops, but they need a good shrubby understorey too. In winter, they still require trees and shrubs but also come onto bird tables and feeders for food. They can be very loyal to an area of gardens for several weeks.

Food: In the breeding season, they eat insects. They then switch to berries in later summer, enjoying elderberries, blackberries, currants, buckthorns, honeysuckles, Fig, Strawberry Tree, Ivy and more. They eat pollen in spring, such as Goat Willow. At bird tables, they are especially fond of fat and cut apples, but will take peanuts, cheese and coconut.

Roost: In dense cover.

Breeding: They defend a small territory, often less than 1ha. They nest low down in dense cover, often in bramble or nettle patches. They build a lovely cup of grasses, leaves and spiders’ webs, finely lined with grasses and hair. They raise one, sometimes two, broods. The four to five eggs in each clutch are laid April–June and are incubated for 10–16 days. The young fledge 8–14 days after hatching.

So… In larger gardens, encourage them to breed by creating a woodland feel, full of a thick understorey where they can nest safely. In winter, many of us will be treated to a visit if we offer a constant supply of apple halves and fat balls.

A black topknot on grey is the adult male Blackcap’s uniform; in females the crown is coppery.

Goldcrest

Regulus regulus

So small and seemingly vulnerable, you would never suspect that this fragile little bird can fly hundreds of miles over water or survive the Scottish winter.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Resident throughout much of the British Isles. Many more come here in winter from Scandinavia.

Habitat: In the breeding season, found mostly in mature conifers. They can survive where there are just a few, such as Yews in churchyards, but most live in plantations of spruce, Larch and fir. They are more widespread on migration when they visit mixed trees, including Sycamores, and shrubs in hedges and gardens where they often latch onto tit flocks.

Habits: They need to eat almost constantly, and so flit about restlessly, usually high in a conifer. They sometimes seem in a world of their own, oblivious to our presence. In winter, they tend to stick to fixed feeding areas. Populations crash in hard winters.

Food: Insects such as springtails, bugs and moth caterpillars, spiders, plus a few spruce and pine seeds. They are very rare at bird feeders.

Roost: In dense conifer foliage, often several birds huddled together.

Breeding: They defend a territory of around 1ha, nesting high on the ends of conifer branches and building a warm ball of moss, lichens and spider silk entered through a tiny hole. They raise two broods. The 7–12 eggs in each clutch are laid May–July and incubated for 15–17 days. The young fledge 17–22 days after hatching.