Barely bigger than a thumbnail, a young Common Frog – freshly emerged from the pond – may then spend the rest of its adult life in your garden if conditions are right.

Gardening for Reptiles and Amphibians

When I was about six, we sacrificed a corner of the lawn and dug a pond that was almost as deep as I was tall. Once filled, frogs arrived as if by magic, and every year we would watch for the first frogspawn, marvel as it hatched, delight at the wriggling tadpoles, and watch in wonder as they grew stumps that turned into legs.

Barely bigger than a thumbnail, a young Common Frog – freshly emerged from the pond – may then spend the rest of its adult life in your garden if conditions are right.

What made the experience all the more powerful was the fact that frogs were one of the few wild creatures I was able to touch. Many found themselves pounced upon and temporarily cupped in my little hands. Some I now suspect were actually trying to get away from the pond but found themselves ceremoniously carried back ‘where they belonged’. How they must have cursed me!

Reptiles and amphibians seem to create these kind of vivid memories for people. Interactions with them are often rare, but when they happen, they are filled with curiosity and delight. I love to lie awake on spring nights listening to toads gently bleating out their love songs.

So it might seem a shame that we have just a fraction of the almost 200 reptile and amphibian species found in Europe, but the few we have will give you much pleasure and are well worth gardening for.

The Common Lizard is a really attractive creature to have visit your garden. To see them you will need to creep up quietly – a heavy-footed or swift approach will see them dart for cover in the blink of an eye.

SNAKES

Few of us see a snake from one year to the next and yet age-old fears live on – I’m sure some of you are shuddering at the very thought of snakes in your gardens. Others are probably getting very excited at the prospect!

In reality only larger gardens tend to be suitable for snakes. But if you do have a chance to encourage them, please do, for these are amazing, rather shy and misunderstood creatures which are struggling as many of their favourite habitats are lost.

Adder

Vipera berus

Readily told by the zigzag line down its back, the Adder is very rare in gardens. It has a venomous bite that is dangerous to pets, children and the elderly, but it is a shy creature that only attacks if severely provoked.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Widely if thinly spread throughout much of mainland Britain, but absent from Ireland.

Habitat: They occupy a surprisingly wide range, favouring heathland especially, but also sunny hedgerows, open woodlands, riverside meadows, downs, dunes and moors. They are rare in gardens unless near these habitats. They like to warm themselves beneath sheets of corrugated iron or roofing material.

Habits: They hibernate throughout the winter, often in groups, underground in holes, burrows and among tree roots. The males emerge on warm days from late February onwards and bask. Females emerge a month later, and they all then move to preferred breeding habitats up to 2km away. Here rival males do the ‘dance of the Adders’, which is actually a wrestle for supremacy.

Food: Small mammals (voles and mice), plus some amphibians, lizards, etc. Young Adders eat insects.

Breeding: They first breed when three to four years old. Mating is in late April–early May. The 6–12 young develop inside the mother and are born live in very late summer or even delayed until spring.

So… Few gardeners have the chance to encourage them, and be mindful of children and pets if you do. Offer quiet undisturbed places, especially warm woodland gardens and places with heathland plants, with plenty of rodents to catch.

Grass Snake

Natrix natrix

A large non-venomous snake with prominent yellow and black markings on the head. They may lunge if provoked, but are more likely to roll over and play dead, their tongues lolling out.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found throughout much of southern England and Wales and some as far north as southern Scotland, but rare in the north and absent from Ireland.

Habitat: Mainly wet meadows, riverbanks and damp woods, but some drier hedgerows too. A secretive visitor to a surprisingly large number of rural gardens.

Habits: They hibernate in burrows and under large log piles, emerging in March or April. Surprisingly, they are good swimmers, often hunting in water and even able to stay submerged for half an hour.

Food: Frogs, toads and newts, plus some fish. Young Grass Snakes eat young amphibians and insects.

Territory: They may cover a wide area, even as large as 100ha.

Breeding: Males mature at three years, females at five years. After mating in spring, females lay about 30 sticky eggs in June–July in rotting vegetation such as sunny compost heaps and decomposing leaf piles, where the heat helps incubate the eggs. Several females often choose the same spot. Incubation lasts six to ten weeks, with the young hatching August–October.

So… This is a relatively easy snake to help. Create a pond fit for amphibians, a nice undisturbed rotting pile of vegetation in which the snakes can lay their eggs, big half-buried log piles where they can hibernate, and ensure they can slither easily under garden boundaries.

The sight of a snake might evoke primitive fears in us, but the Grass Snake is harmless, easily told from the Adder by its yellow collar and lack of zigzag markings down its back.

LIZARDS

Both the Slow-worm and the Common Lizard are more common than people realise, and both eat garden pests, so these are visitors well worth welcoming.

Slow-worm

Anguis fragilis

Seemingly part snake, part lizard and part worm, Slow-worms are harmless, legless lizards we rarely see but which probably visit many gardens.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found throughout much of Britain but absent from Ireland and upland areas.

Habitat: They like lush, moist vegetation warmed by the sun, so are found along hedgerows, woodland glades, scrubby areas, waste ground and heaths, and they adore open, undisturbed compost heaps.

Habits: They keep very much out of sight, slipping gently through the grass and undergrowth or even burrowing through loose soil and roots. They don’t often bask in the open, but are very fond of soaking up the heat beneath a corrugated sheet or rubber mat. They are especially vulnerable to cats.

Food: Slugs, worms, some snails, plus other small invertebrates, hunting often at dusk.

Hibernates: They overwinter underground in burrows or cavities, October–March.

Breeding: Young Slow-worms take several years before they breed. Females give birth to 6–12 young in spring, each in a membrane from which they quickly wriggle free.

So… This is definitely one species that will benefit if more of us make Wildlife Sunbeds (opposite), giving them somewhere that is snug and safe from predators. Alternatively, build an open compost heap that they can crawl into and out of, have corridors of lush vegetation and try to resist killing all those slugs!

With attractively polished bronze skin, Slow-worms can grow up to 40cm long and may live up to a decade. They can make a good dent in your slug population, so cherish them!

Common (Viviparous) Lizard

Lacerta vivipara

Common in the countryside but infrequent in gardens, they are the closest you will get to having little dinosaurs in your garden!

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Widespread but scattered across the British Isles.

Habitat: They like all sorts of habitats where there is undisturbed ground cover with plenty of sunlight and humidity, so are found on heaths, hedgebanks, sunny woodlands and in a few gardens.

Habits: They are sedentary, rarely straying more than a few metres from home. They bask avidly in spring and autumn, choosing a log, wall or fenceline to soak up the sun and raise their body temperature. On hot days they stay undercover.

Food: Insects and spiders, caught by day and by sight using the lizards’ lightning speed.

Hibernates: Underground in a frost-free hole, usually November–March.

Breeding: Young are born June–September, with usually six to ten live young to a litter, each wrapped in a membrane from which they break almost instantly.

So… Give them safe sunbathing platforms facing south – logs, rocks or wildlife sunbeds (see here) – near to lush vegetation where they can hunt. Build rock piles, preferably including boulders loosely buried deep in the soil under which they can rest overnight and hibernate.

Adult Common Lizards come in a range of colours and patterns, such as this one freckled with gold; their young are almost black.

How to make a wildlife sunbed

Reptiles, being cold-blooded, need to warm up before they can get going in the morning (I know the feeling). People who study wild snakes and lizards use this fact to their advantage by putting out corrugated sheets, either of iron or of modern roofing materials. These sheets warm up in the early morning sun much quicker than the surrounding vegetation, and the reptiles have an uncanny knack of finding them. All the scientists have to do is then wander from sheet to sheet, gently lifting them up to see who is warming their cockles underneath.

If it works in the countryside, I wondered why we don’t do more of that in gardens. So I now have four sheets in my garden, under which I expected to find Slow-worms but instead I discovered Grass Snakes! Not only that, but under one I have a huge ants’ nest. It is fascinating; lift it up in the morning and usually a consignment of ant larvae and pupae have been brought to the surface for a warm-up, but by afternoon, they have usually all been taken back underground.

But my favourites are the Field Voles which nest under the sheets, creating little domed nests out of dried grasses.

If you feel like giving it a go, here’s how to make your sunbed.

1.Buy a sheet of bituminous corrugated roofing material from your local DIY store. It normally comes in 2m x 1m sheets, so it may be too big for your car and you may need to get it delivered. You could use iron sheets but they can rust terribly and develop jagged edges, so roofing material is much safer to use with children.

2.I then cut the sheet into two 1m x1m squares, which don’t look quite so obvious when placed in the garden, and are easier to lift and lower without risking hurting the creatures underneath. Whatever you do, don’t try to saw the roofing material! The bitumen covering will just clog the teeth of the saw in moments and you won’t be at all happy. Use a Stanley knife instead, pushing through into a soft surface like a lawn.

3.I then drill a couple of holes and thread some string through as a handle. It means I don’t have to put my hand underneath the edge of the sunbed to lift it up, very important it there is any chance that you have Adders using your garden.

4.Then put your sheets out in sheltered locations around the garden. I spread mine in a range of sunny and half-shady positions, as different creatures like different conditions.

5.When lifting the sheets, do so slowly and gently, look for just a few seconds, and then gently lower it back down. Ration yourself to looking only once a week or so, or your residents may get twitchy about being disturbed too often.

AMPHIBIANS

These much-loved species have the incredible ability to survive both in water and on land, the adults often breathing through their skin as much as with their lungs. We also get to witness the miracle of metamorphosis from spawn to tadpole (or eft) to adult. Oh, and they are good pest-controllers into the bargain.

Common Frog

Rana temporaria

It’s hard not to like frogs. Big pop-up eyes, a wide smile and a penchant for munching on slugs make these leaping pond-dwellers all-round favourites.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found throughout most of the British Isles from sea level almost up to the snow line.

Habitat: They use all sorts of undisturbed habitats wherever there is unpolluted shallow fresh water nearby (preferably without fish) and some shady moist places. They will breed in the same pools as toads and newts.

Habits: Sedentary by nature, they spend much of the year out of water, rarely moving more than 1km from the breeding pond. They find food among thick damp vegetation, and shelter in moist places such as log piles and among rocks.

Hibernation: October–February, usually in the mud at the bottom of ponds and ditches, where they breathe through their skin, but occasionally in damp, dark, sheltered locations out of water such as deep leaf-litter and log piles.

Food: They eat slugs, worms, flies, beetles and other insects, catching faster creatures using their whip-like tongue. The tadpoles eat algae, neatly cleaning the sides of ponds.

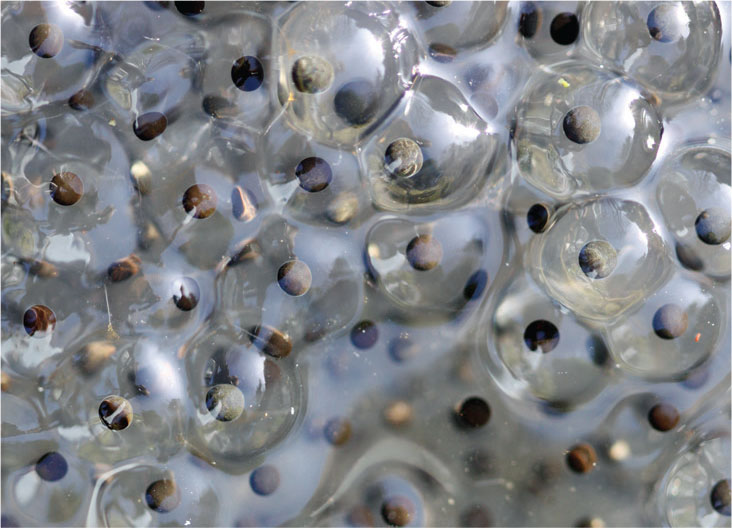

Breeding: Frogs breed by their third year, and migrate back to their pond by night in February or early March. There, the males chorus to attract females. Pairs join up, males claiming a female by climbing on her back in a tight grip (amplexus). Females often lay more than 1,000 eggs in clumps of floating spawn. The eggs hatch after 10–21 days. Froglets leave the pond from about late June.

Threats: Spawn is eaten by newts and can be killed by late frosts. Tadpoles are eaten by dragonfly nymphs, diving beetles, newts, fish, Blackbirds, Crows, Grey Herons and Mallards. Froglets succumb to Hedgehogs and garden birds, and adults to Grey Herons, Foxes and cats. Many adults are also killed on the roads, and some die during hibernation if the pond freezes and vegetation rots under the surface. The big killer, though, is disease.

So… A pond is essential – make sure there are shallow areas in sunshine and plenty of aquatic vegetation. But don’t ignore their other needs. In particular, damp meadow areas full of insects and slugs and moist sheltered flowerbeds are important, as are hideaways under rocks, bricks or logpiles. The best time to clean out ponds is October, in between breeding and hibernation, and check meadows and long grass before mowing.

FROGS AND DISEASE

There have been some devastating outbreaks of disease in some parts of the country in recent years, in particular the ranavirus, which is thought to have been brought in from North America. It is untreatable, with large numbers of Common Frogs, some Common Toads and even newts dying each year, usually in the heat of midsummer. They become lethargic and emaciated, and can develop secondary infections and lesions. To reduce the risks, don’t move frogspawn between ponds, which can transfer the disease, and if you suspect frogs have the disease in your garden, report it to www.gardenwildlifehealth.org.

Frogspawn is usually laid in shallow, sunny water. The higher the temperature of the water, the faster the spawn tends to hatch.

When a pond develops a large frog population, as here in my tiny suburban garden, the surface can become a mass of bodies during the mating season.

Common Toad

Bufo bufo

Toads inspire so much affection that each year, all over the country, volunteers spend many cold spring evenings helping them cross roads safely as they migrate back to their breeding ponds.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Throughout much of Britain but absent from Ireland.

Habitat: They live in surprisingly dry (although not overdry) habitats throughout much of the year, including woodland, hedgerows, scrub and rough grasslands, but need access to a shaded and moist hollow by day such as under a log or stone. They breed in a pond, often quite large and deep, and do well in ponds with fish because toadpoles taste awful. (‘Toadpole’ isn’t a real word, but it ought to be.) They are scarcer in gardens than Common Frogs, and rare in urban gardens.

Habits: Generally nocturnal and solitary, they wander slowly through vegetation and leaf-litter looking for prey, before returning to their regular daytime hideaway. They hibernate October–March underground in a mouse burrow or under a woodpile or compost heap, sheltered from frost and predators. Males emerge by early March, females somewhat later. They are preyed upon by Grass Snakes, but most deaths are on roads, during the stress of courtship, or are caused by disease.

Food: Insects (such as beetles and ants), spiders, worms, snails and some slugs. Toadpoles feed on algae.

Breeding: In spring, males and females migrate back to traditional breeding ponds, which can be 1km away. Here males call and wrestle, often at night, and when they find a female, climb on her back in a tight grip. Females then stay in the pond just long enough to lay their eggs. Each female can lay up to 8,000 eggs. The eggs hatch after 10–20 days into toadpoles, which are black and gregarious; they then metamorphose and leave the pond when only just over 1cm long.

So… A pond, of course, is key – the bigger you can make it the better. Make sure there are some aquatic weeds, such as Hornwort, and shallow areas in the sun. In addition, you need to make it easy for toads to actually get into your garden and to the pond – those Hedgehog Highways under fences are just the ticket. Add plenty of good feeding areas (leaf-litter, moist tall grass, flower borders and shrubberies), and a wide range of undisturbed retreats including log piles (half buried if possible), compost heaps and jumbled bricks.

Unlike the clumps of frogspawn, toadspawn is laid in long strings wound around waterweed (top). ‘Toadpoles’ (bottom) are blackish-brown, much darker than the brown and grey of Frog tadpoles.

The warty skin, the swollen poison gland behind the eye, and the lack of a dark, smooth cheek-patch are the easy ways to tell a toad from a frog. But beware, frogs in particular come in all sorts of colours!

Newts

Even small garden ponds are likely to harbour a newt or two. Looking rather like swimming lizards, they might not have caught the public imagination in the same way frogs and toads have, but newts still have plenty of character.

In the UK, their profile would be even lower were it not for the large, rare and protected Great Crested Newt Triturus cristatus, which grabs the headlines when its presence stops wildlife habitat being lost to ‘development’. You need a licence in the UK to collect or even handle them.

Few people realise that newts can actually be watched relatively easily. The secret is a special Newt-watching Device (NWD). Battery operated, they come in a range of colours and sizes, and are sold under the name ‘torch’.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Your garden is most likely to support the Common Newt Triturus vulgaris, often called the Smooth Newt, which is widespread throughout the British Isles. Don’t discount finding the Palmate Newt Triturus helveticus, however, especially in western Britain (but not Ireland). It looks much like the Common, but has an unspotted throat and males have webbed back feet. Finding the Great Crested is not out of the question in Britain (although again Ireland misses out).

Habitat: In the breeding season, the Common enjoys still, shallow pools and even ditches and flooded tyre tracks, preferably neither too exposed nor shadowed. The Palmate especially likes pools in broadleaved woodlands, while Great Cresteds like water depths of at least 50cm. Once the breeding season is over, newts leave the water and head to all sorts of grassy and leaf-litter habitats.

Habits: In water, they tend to live on the bottom. Great Cresteds form leks where the males gather to display at night. Out of water, adults hide by day and emerge at night to rove through the undergrowth looking for prey. It is unusual to see a newt away from water even though they spend much of their lives on dry land. The adults are predated by snakes, Hedgehogs, cats and small mammals, and the larvae (‘efts’) by frogs, toads, dragonfly larvae and water beetle larvae.

Hibernation: November–February, in a damp sheltered nook such as under log piles or rocks or among tree roots.

Food: Adults eat insects, slugs, worms and small snails. The efts are carnivorous and eat aquatic insect larvae, small freshwater crustaceans, and are notorious for eating frogspawn and tadpoles.

Breeding: Adults usually return to their breeding ponds on wet nights during February–April, the females laying 200–400 eggs, stuck individually to waterweeds. The frilly efts hatch after one to four weeks and live alone, with some overwintering before metamorphosing into adults.

So… A pond is clearly a vital thing to provide, but they also need all those out-of-water hunting habitats and suitable places to hide and hibernate. So dig a pond, create log piles and rock piles, and make sure you have areas of uncut grass, deep leaf-litter and thick ground vegetation.

It may seem odd to see a newt out of water, but they spend more of their year on land than in water. This is a female Common Newt heading back to her breeding ditch in spring.

A male Common Newt (above), in breeding dress and with a fiery belly, has a crest all along his back, but it is nothing like the wild spiky crest of the Great Crested Newt.

Make an amphibian hibernaculum

If you needed somewhere dark to sleep for weeks on end during the winter where you wouldn’t dry out, where you wouldn’t freeze, but wouldn’t get too warm either, and where predators couldn’t get at you in your dozy, vulnerable state, where would you go in a garden?

That’s the challenge facing our amphibians. Some Frogs elect to swim down to the mud at the bottom of ponds, but many of them and also our Toads and newts try to find somewhere drier to wriggle down into, preferably a little way underground.

If you’ve made a logpile, that may do the trick, or they may snuggle into the base of a compost heap or even under a shed. But the following design is thought to offer some of the best conditions for them.

1.You’ll need some chunky waste materials such as lumps of hardcore, broken bricks and old logs – the kind of things that are lying around in many gardens.

2.If you are on free draining soils, dig a hole about 30–50cm deep in a shady location; if you can, make your hole a metre or so across. If you are on really wet, impermeable soils, don’t worry about this step.

3.Now fill your hole with your bulky material, or on wet soils just pile it all up on the surface. Keep going until you have quite a mound. Aim for the pile to be stable, with lots of possible entrance holes into a labyrinth of different-sized chambers and passageways. Small newts and froglets can wriggle into gaps barely a centimetre across; large toads may need ones 6–8cm or so wide. It doesn’t matter if your hibernaculum looks rough and ready but if you want you could aim for some architectural merit in how you arrange everything.

4.If you dug soil out, you can sprinkle some back onto the pile, but you don’t want the rain to swill too much of it into the cracks and crevices which might clog up all those chambers you created.

5.As a finishing touch, you could sprinkle some wildflower and wild grass seed on and around the pile so that the amphibians have some cover as they enter and leave their winter dormitory. It will also help bind together any soil you put on the pile.

It should now last for several seasons, and some amphibians may even return to it year after year.

Prepare an area of shady ground – this is a great way to use a forgotten corner of the garden.

Dig a hole – if amphibians can get underground in winter, the conditions are much more constant.

You could just create a random mound, or you could get creative, like my ‘Froghenge’.

Fill with large rocks, making sure there are lots of different sized gaps for everything from large Toads to tiny Froglets to wriggle into.