Even some dramatic-looking creatures that make it into gardens, such as this longhorn beetle, are not familiar enough to the general public to have a common English name: this is Strangalia maculata.

Gardening for Minibeasts

There is a whole host of smaller garden species that might not, at first, seem like worthy recipients of your hospitality. Many of them, however, turn out to be fascinating in their own right and often these species are crucial items on the menus you hope to serve up for your larger garden guests.

Even some dramatic-looking creatures that make it into gardens, such as this longhorn beetle, are not familiar enough to the general public to have a common English name: this is Strangalia maculata.

After all the glam and attention-seeking celebrities of the garden-wildlife world – the A-list birds, beauty-queen butterflies and character-actor amphibians – the supporting cast often don’t get much of a look in. Most are small or even tiny, many are nocturnal, and some are decidedly ugly or even alarming.

Many are also ridiculously hard to identify, a frustration given that we humans delight in being able to give a name to everything (and tend to ignore those we can’t).

But while they may not have quite the allure of their larger brethren, these creatures and ‘lesser’ plants are certainly not ‘extras’. Nature, as we know, is one large interconnected web, where the smallest creatures underpin complex food chains. Take away the creepy crawlies, fungi and mosses and our garden wildlife hotel loses its foundations and comes crashing down.

Even many species that aren’t our favourites, such as this sarcophage fly, are both visually impressive, and an important part of the garden food chain.

Some insects that everyone has heard of, such as the grasshoppers, are actually quite rare in gardens, and need hard work on your part if they are to flourish there.

In fact, this section doesn’t even start to delve into the microscopic world, where, for instance, small lumps of soil are stuffed with hundreds of mites and springtails, thousands of tiny worms (nematodes), not to mention billions of bacteria.

But that still leaves us plenty of fascinating minor beasties that we can watch out for, get to know and try to help.

I realise that studying even one particular group of these to the point of precisely understanding their home needs is often a life’s work, but there are plenty of general principles we can apply to help satisfy them.

Grasshoppers and bush-crickets

These have long been popular little insects, perhaps because they don’t bite, their jump is amazing, and they make funny percussive noises in the grass and bushes (‘stridulation’).

All have the characteristic long-jumper back legs, so the simple way to tell the two groups apart is that grasshoppers have short antennae, bush-crickets have huge ones. Unfortunately, most gardens don’t seem to be great habitats for them, but see that as your challenge!

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: These are mainly insects of sunny climes, with only about 30 of Europe’s 650 species making it to the British Isles and only about 10 in Scotland. The few likely to turn up in gardens are Speckled Bush-cricket Leptophyes punctatissima, Oak Bush-cricket Meconema thalassinum, Dark Bush-cricket Pholidoptera griseoaptera, Meadow Grasshopper Chorthippus parallelus (right) and Common Field Grasshopper Chorthippus brunneus.

Habitats: Grasshoppers like open, sunny, undisturbed meadows where the grass grows quite long; bush-crickets live up to their name, liking thickets and hedgerows. Individual species have subtly different preferences.

Habits: They live to a large extent in sedentary colonies, where the males set up a territory by singing. Grasshoppers are usually active by day, bush-crickets most often at night. Bush-crickets in particular are difficult to find – try homing in on one singing and you will discover their ventriloquial powers. Most grasshoppers can fly; many bush-crickets can’t, although the Oak Bush-cricket most certainly can and is attracted to lit bedroom windows.

Food: Grasshoppers are vegetarian, eating wild grasses and some low-growing plants. Bush-crickets are usually partly or mostly carnivorous, eating caterpillars and other insects, although the Speckled Bush-cricket is partial to a bit of bramble or Raspberry leaf.

Breeding: Females lay eggs in or near the ground, or they insert them into plant tissue or behind bark. Most species winter as eggs, all the adults dying as winter draws in. They hatch as miniature versions of the adults in spring and moult up to ten times to reach maturity by late summer.

So… Why are grasshoppers and bush-crickets not a common sight in summer gardens? In the case of grasshoppers, lawns are usually too manicured for them to survive. In the case of bush-crickets, our shrubberies aren’t always a match for a good bramble thicket, but as both the Speckled and Oak have pitiful songs maybe we overlook them. If you can, turn your lawn into a sunny meadow and create a woodland garden, and success may come leaping your way.

The ridiculously long antennae on this grasshopper-like insect mark it out immediately as a bush-cricket (in this case a Speckled with its tiny and useless wing cases).

It is only by late summer that grasshoppers and their allies reach full size, like this Meadow Grasshopper. They will have moulted up to ten times by this stage.

Beetles

This is an almighty group of insects with all manner of body types and sizes, colours and life-styles. In the British Isles alone there are about 4,000 species, and most gardens will host hundreds of these.

The one thing they all have in common is that they have jaws they use for munching. Many adults have a rather rounded shiny ‘shell’ formed by the leathery forewings, which is a fantastic protective carrying-case for the delicate hindwings, which are used for flying. Famous groups of beetles include ladybirds, stag beetles and cockchafers, but there are also (deep breath) tiger beetles, ground beetles, dor beetles, dung beetles, longhorn beetles, leaf beetles, weevils… I could go on!

Some beetles are serious pests of crops or foodstores, but most are pretty, innocuous or even useful, either for us gardeners or for other wildlife. Think of the aphid-eating ladybirds, or just have a look through the diets of many of our favourite garden birds and you will see how many feature beetles and bugs in their diet.

Despite all their differences, fulfilling these generic home needs will ensure you have a wide range of beetles using your garden, and then we’ll look in more detail at some of the best loved species.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Beetles are everywhere, but generally there are more species to the south and east of the UK – cold, damp conditions don’t suit them well.

Habitat: There’s a beetle for every habitat, but heathland, undisturbed flower-rich grasslands and especially woodland generally hold the most species, but gardens can be almost as rich.

Habits: Many are nocturnal. Even those that aren’t are often great at hiding, either by being well camouflaged, by living nocturnal lifestyles or by tucking themselves away among leaf litter, in deep vegetation, or in the soil. Most prefer not to fly, spending life on their feet, either on the ground or in vegetation.

Food: Some beetles use their biting jaws to eat plants, others to devour other creatures, and some to bore into live or dead wood. Most have larvae that are like maggots-with-legs with the same biting jaws (and tastes) as the adults.

Breeding: Most species survive the winter as eggs in the soil or behind bark.

So… Although beetle lifestyles are varied, if you aim to deliver these basics you will encourage a wide range of species and hence benefit the whole food chain above:

Plants, plants, plants. Whether trees, shrubs, climbers, flowerbeds or meadows, pack in whatever you can. Many of the vegetarian beetles have very picky needs, requiring a single plant species, so having more types of plant should mean more beetle diversity. Plant choice is also important – good old hawthorns or oaks are probably among the best for supporting lots of species.

Plants, plants, plants. Whether trees, shrubs, climbers, flowerbeds or meadows, pack in whatever you can. Many of the vegetarian beetles have very picky needs, requiring a single plant species, so having more types of plant should mean more beetle diversity. Plant choice is also important – good old hawthorns or oaks are probably among the best for supporting lots of species.

Provide plenty of rotting wood.

Provide plenty of rotting wood.

Use mulches, especially of leaflitter, for them to rove through.

Use mulches, especially of leaflitter, for them to rove through.

Compost heaps are great for both debris-eaters and predator beetles.

Compost heaps are great for both debris-eaters and predator beetles.

And, of course, don’t use insecticides.

And, of course, don’t use insecticides.

When we think of beetles, we tend to focus on the larger and more colourful species, but many such as these pollen beetles are small and easy to overlook – except as here when they gather en masse.

Soldier Beetles, such as this Cantharis rustica, visit flowers just like the Thick-kneed, but are there to hunt other insects.

One species of native ladybird that seems to have coped relatively well with the arrival of the invasive Harlequin is the Seven-spot, which can still be seen in large groups in spring, fresh out of hibernation.

Ladybirds

Perhaps the best loved of all groups of beetles, most of the 40 or so British species of ladybird not only look pretty funky but are also inveterate chompers of aphids, both as the familiar adults and as the rather aggressive-looking larvae, so they are well worth encouraging.

Common garden species include the Two-spot Adalia bipunctata, the Seven-spot Coccinella 7-punctata, and the black-spots-on-yellow 22-spot Psyllobora 22-punctata.

To meet their home needs, clearly don’t obliterate your aphids with chemicals, and also provide somewhere for adult ladybirds to hibernate – a good, diverse garden, with clumps of tall grasses, hollow plant stems, leaf litter and old trees should do the trick.

Sadly, the most frequently seen ladybird in most parts these days is the Harlequin Harmonia axyridis. Like a mutant ninja ladybird, this Asian import will happily munch on its smaller cousins. It arrived in 2004 in southern England, and has spread at alarming speed northwards, reaching Scotland within five years. At present there seems little we can do to combat them.

Here is one ladybird that proves that not all are aphid munchers – this is the 22-spot Ladybird, which feeds on mildews.

Stag beetles

Being our largest beetle – with males up to 7.5cm long and sporting dramatic ‘antlers’ – the Stag Beetle Lucanus cervus has lots of fans. It is found in southern England, where numbers are thought to be declining. I am lucky enough to have Stag Beetles breeding in my garden, and it is quite a sight at dusk on a summer’s evening to have the adults pass by in a flight best described as ‘lumbering’. The prime home need is rotting tree stumps such as those of old fruit trees. It is here that their white, bloated larvae will munch on their high-fibre, low-calorie diet for up to three or four years before emerging. You can create ideal conditions by burying a log of a suitable tree species, with the top just poking out of the ground.

The male Stag Beetle is our largest beetle, with ferocious looking ‘antlers’ that are used in head-to-head bouts with other males. If you are lucky enough to see one in the hand, I have always found them to be gentle giants.

Stag Beetle larvae are almost as impressive as the adults, but are rarely seen as they need to stay deep within their rotting log or else they would make an easy and satisfying meal for many a predator.

Bloody-nosed beetles Timarca

Handle these black, neatly-domed beetles and they will exude their own blood to desperately try and fend you off, hence their name. They are found in open grass habitats in the southern half of the UK and are peaceful vegetarians, feeding on bedstraw leaves. If you don’t have bedstraws in your garden, you won’t have the Bloody-nosed beetles, showing how even beetles can have very particular home needs.

The Bloody-nosed Beetle can often benefit from a helping hand. They can’t fly, and walk very slowly, so any that stray onto paths or roads risk being squashed without a kindly lift to safety.

Thick-kneed Flower Beetle Oedemera nobilis

Once you’ve seen the males of this green, metallic beetle, you’ll never forget them, for they are the original winner of the knobbly-knees competition. Only their hind legs have the swollen joints. You can find both sexes nibbling pollen at all sorts of summer flowers, from scabiouses to bindweeds. The larvae live in hollow plant stems, another reminder not to hack back everything to the ground at the end of autumn.

This is the male Thick-kneed Beetle – the females have much more shapely legs!

Wasp Beetle Clytus arietus

This beetle almost matches the Stag in terms of dramatic looks, with its black and yellow warning markings. It is quite harmless, despite its large size. Its larvae live in dry, dead wood such as willows and birches (showing how your log piles shouldn’t just be in damp, shady corners), while the conspicuous and fearless adults visit flowers.

The stunning Wasp Beetle is not at all related to wasps or hornets but has evolved the same yellow-and-black warning colours.

PROBLEM BEETLES?

A few beetles can be a bit of a nuisance for gardeners. Perhaps the most infamous is the Vine Weevil Otiorhynchus sulcatus, a regular in the top ten of garden pests. The root-chomping larvae are the main problem, especially in containers.

Meanwhile, two accidental imports are creating quite a stir: the bright-red Lily Beetle Lilioceris lilii from Asia can devastate lilies and other bulbous plants, while the Rosemary Beetle Chrysolina americana from southern Europe, metallic green with red stripes, is spreading like wildfire. Just pick off the adults if their nibbling is badly damaging your plants.

However, for most problem beetles, including the Garden Chafer Phyllopertha horticola and Cockchafer Melolontha melolontha whose larvae feed on plants roots, the best answer is a healthy, wildlife-rich garden where nature will find a balance.

Cockchafers can be seen as a menace because their grubs eat plant roots, but that’s where grub-eating Starlings and Rooks come into their own, nature’s own pest control.

True bugs

When I say ‘bug’, I mean the group of insects called the Hemipterans (literally, the ‘half-wings’), also known as the True Bugs, rather than ‘bug’ as in ‘any creepy-crawly’. They are a bit beetle-like but are even more diverse in form and lifestyle, with over 1,800 species in the UK including familiar groups such as the shieldbugs and aphids, but with a whole host of others such as flatbugs, barkbugs, groundbugs, damselbugs, mirid bugs and, yes, more. See also here for some very familiar water bugs, such as the pond skaters and backswimmers. And those noisy churring cicadas that lull you to sleep on tropical holidays? Yes, those are bugs too.

One common feature of all of them is that they have mouthparts shaped like a sharpened straw. This helps explain what aphids are doing when they cluster along your stems: each of them has pierced the stem and is merrily supping away as the plant tries to pump fluids up to its leaves.

Froghoppers and their relatives, the leafhoppers, are bugs, too; they hold their wings above their back like a ridge tent. They are plant eaters, and are quite abundant in gardens, with different species associated with particular plants. But it is the globs of froth exuded by froghopper nymphs with which we are most familiar – often called cuckoo spit, it is a protective cloak of bubbles within which the nymph can grow.

Shield bugs live up to their name thanks to their distinctive shape. There aren’t many widespread species, and they are commoner in the south.

HOME NEEDS

With so many species of bug, found in so many habitats, there are inevitable endless permutations of home needs. However, this is one group of species that will just automatically benefit from all the other things you do for wildlife in the garden.

So… Lots of plants of lots of different types and a lack of insecticides will mean lots of bugs and that, in turn, will mean lots of food for other wildlife.

PROBLEM BUGS

Being predominantly plant eaters, it is inevitable that some may cause us some grief when we are trying to grow a lovely plant and they think we are providing dinner.

Aphids are perhaps the biggest culprits. There are dozens of species: green ones are known colloquially as ‘greenfly’; black ones as ‘blackfly’; white ones as...yes, you get the picture. But they are most definitely bugs, not flies.

But aphids do have their uses. Many exude a sweet liquid called honeydew, which is harvested by ants and drunk by various butterflies and other insects. Aphids are also important in the diet of ladybirds, hoverfly larvae, lacewings and some birds. A world without them would be much the poorer, so just tolerate them if you can, and work hard to have a garden full of their predators to keep their numbers in balance.

Scale insects and mealy bugs are also true bugs, again sucking away at plants, but are perhaps most of a problem with houseplants and in the greenhouse. Focus on having a rich, varied ecosystem in your garden and if a plant is really susceptible to problem bugs, take that as a sign to try growing something else.

Bugs tend to grow in stages (instars), shedding their outer skin and expanding into their new one underneath. Each time they can look quite different – this is a late instar of what will become the all-green Common Green Shieldbug Palomena prasina.

This is the fairly common Dock Bug Coreus marginatus, which feeds on dock and sorrel leaves and seeds.

Flies

Why, oh why, would anyone want to garden for flies? Horseflies, bluebottles, mosquitoes, midges, dungflies – it is hardly a roll call of sought-after or cherished wildlife, and I can’t see The Wildlife Gardening Guide to Flies being a best seller.

Time for a spot of public relations on their behalf. Or at least on behalf of the wildlife that does love flies. For without flies, Swallows and House Martins, wagtails and warblers, and, of course, Spotted Flycatchers would all go rather hungry. In fact, flies feature heavily in the diet of species ranging from dragonflies to amphibians, and are vital links in many food chains.

When you think about it, how many of them actually bother you? Houseflies, yes, and if you live in the north and west I’ll agree that tiny midges can be hugely irritating. But there are more than 5,000 species of fly in the British Isles alone, and the vast majority of them never make a nuisance of themselves.

I will deal with the rather fun hoverflies separately, but here is a quick overview of some of the other prominent members of the fly family and their home needs.

HOME NEEDS

Different flies live very different lives, so pinning down home needs for them all would be a challenge. They do share some similarities in their life cycles, however. All lay eggs, which then hatch into legless larvae. These usually live quite a different life from the adults: some live in water, some in soil, some in live animals and others in plants, but most live as maggots in decaying matter, animal or vegetable.

The larvae then pupate – many pupae can still wriggle. When they hatch into the adult, most, but not all, flies can fly! Their mouthparts are adapted for sucking, the only problem for us being that some are sharp enough to pierce before they suck. But at least you now know that it is impossible to be bitten by a mosquito – you just get sucked by a very sharp straw!

So… Gardening for flies equals gardening for other wildlife. Although different fly species have such different needs, if you do the following you will create a garden where fly-eating wildlife will be happy:

Make a pond

Make a pond

Create compost heaps

Create compost heaps

Don’t use chemicals

Don’t use chemicals

Grow plenty of flowers

Grow plenty of flowers

And don’t worry – few flies will trouble you!

And don’t worry – few flies will trouble you!

DISCOURAGING UNWANTED FLIES

Houseflies can be limited through good kitchen hygiene, while midges and mosquitoes are most prevalent where water has turned stagnant. This tends to happen in open water butts, buckets, and ponds where organic matter such as leaves has been allowed to accumulate.

Lacewings are not true flies, but like hoverfly larvae they too eat aphids, making them the gardener’s friend. Hoverfly larvae even camouflage themselves using the empty skins.

Bee-flies are one of the signs of spring. Like small bumblebees with hair-thin legs, they hover in front of low-growing spring flowers such as lungworts and primroses to suck nectar with their tusk-like probosces, and then seek out the nests of bees where their grubs feed on bee larvae.

Many of the metallic flies such as this ‘greenbottle’ have maggots that undertake the rather unsavoury job of clearing the landscape of dead creatures, and so deserve our gratitude.

Hoverflies

Have you ever stood in the garden in a sheltered spot and watched a hoverfly live up to its name? It is an astonishing feat as it hangs motionless in the air, wings a-blur, somehow coping with any gust of wind. Suddenly, it will dart off, maybe to intercept a rival, often to then return to its little mid-air territory.

Rather fewer people notice hoverflies in the flower border, not because there are none there but because of their excellent disguise. Many bear the yellow and black ‘danger’ colours of bees, wasps and hornets, and some are even fluffy to pretend to be bumblebees. It is enough to fool many birds, which avoid eating them rather than risk being stung, when actually the hoverflies are totally defenceless. And it fools us too; on many occasions I have heard people noting the number of ‘bees’ visiting flowers when they are looking at these impersonators.

It means that, compared to bees, hoverflies are little celebrated for the pollination services they bring, but they ought to be.

There are some 280 or so species in the UK, and a good, wildlife-friendly garden can be home to 25 species or more. Jennifer Owen in her Leicester garden found 94 species over 30 years!

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Found in every garden, there are more species in the south, but some rarities are only found in the north.

Habitat: Especially fond of sunny, sheltered habitats with lots of flowers.

Habits: Adults spend a lot of time at flowers, tending to prefer those that have an open, ‘table-top’ shape.

Food: The one thing that people do know about hoverflies is that their larvae eat aphids, which is of course a Brownie point in most gardeners’ eyes. What may therefore surprise you is that, while this is true for many species, there are some hoverflies whose larvae actually feed on rotting vegetation or bulbs, or find tiny morsels in the mud in ponds, or even live as scavengers within the nests of social bumblebees and wasps.

So…

Grow lots and lots of flowers, especially those in the carrot ('umbellifers') and composite (dandelion- and daisy-type) families

Grow lots and lots of flowers, especially those in the carrot ('umbellifers') and composite (dandelion- and daisy-type) families

Dig a pond

Dig a pond

Create sheltered, sunny glade like habitats.

Create sheltered, sunny glade like habitats.

Drone-fly Eristalis: This group of 10 species are very common and are very similar in size, colour and shape to Honeybees. Their larvae are called ‘rat-tailed maggots’ and live underwater, eating detritus.

Bulb-fly Merodon equestris: Bearing an uncanny likeness to a bumblebee, its larvae burrow underground to feed on the bulbs of flowers such as daffodils.

Marmalade Hoverfly Episyrphus balteatus: This is the commonest of the many species that have black-and-yellow wasp-like markings. Their larvae are aphid eaters, crawling along plant stems like little pale maggots hunting their prey.

Hornet Hoverfly Volucella zonaria: Large enough and convincing enough to fool people that it is indeed a Hornet, like all hoverflies it is harmless. It has a fascinating lifestyle, the larvae live in wasps’ nests, acting as cleaners or dining on wasp larvae.

Ants

The fact that they form almost the entire diet of Green Woodpeckers is surely a good reason to want more ants in your garden. No? How about the fact that ants mop up all sorts of troublesome creepy-crawlies that would otherwise ravage your crops and flowers?

Actually ants are a mixed blessing because they also farm aphids, guarding them from predators. And, of course, no sunbather wants ants in their pants, and no cook wants them marching across the kitchen. But hopefully you can find a little place for them in your lives.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: There are about 50 ant species in the British Isles, with fewer the further north you go. Common garden species include the Black Garden Ant Lasius niger, Red Ant Myrmica rubra, Yellow Lawn Ant Lasius umbratus and Yellow Meadow Ant Lasius flavus.

Habitats: Ants are mainly creatures of warm places, with the greatest number of species on sandy heaths and open grasslands. Some are found in woodland.

Habits: Ants live in colonies, with a social structure matched only by the social bees and wasps. It’s a utopian world of queens and their pheromone-controlled daughters, living in a ramshackle underground palace of corridors and chambers. A colony can persist for many years, with queens living three or four. Some species sting with formic acid, some spray the acid, and most also nip with their mouths.

Food: Most species eat a range of plant and animal matter, such as seeds, nectar and caterpillars. Many will climb trees as well as making ground raids. Worker ants that have found food lay a trail of scent for comrades to follow. Ants also milk aphids for honeydew, even taking them back to the nest to tend them.

Breeding: The queen sits within her chamber laying eggs, which workers take away to hatch, feed and guard. Many emerge as new workers, but in late summer there is a synchronised hatching of winged males and virgin queens. These fly up into the sky where they are eagerly picked off by wheeling Starlings, Swallows and gulls. The mated queens that survive come back down to start a new colony.

So… Ants do little damage in the garden, are very difficult to eliminate and are eaten by more garden birds than you’d realise, so tolerate them if you can. Brush the Yellow Meadow Ants’ little soil mounds back into the lawn if they offend you (if not, they make extra microhabitats). If you get Black Garden Ants in your kitchen, then an ant scout has found sweet food and it is time for you to get cleaning!

Wasps and Hornets

I bet the mention of wasps makes you think of those that plague your picnics, determined to get at your jam sandwiches. Yes, they can be a nuisance, but that is just a handful of species whereas there are an astonishing several thousand others that have no interest in you whatsoever.

They include ichneumon wasps, potter wasps, digger wasps. Most are small and solitary, and they just get on with their slightly grim lifestyle of catching insects, immobilising them with a quick sting and laying an egg on them so that the developing larvae can then feast on fresh meat. If you garden for other insects, solitary wasps will come.

Some tiny wasps lay their eggs in plant tissue, which prompts the plant to produce strange tissue called galls, within which the larvae feed. Oak apples, spangle galls on oak leaves and ‘robin’s pincushions’ on roses are all caused by wasps.

The wasps that worry us most are the stinging social wasps (including the Hornet Vespa crabro). They use chewed rotten wood to build football-sized, papier-mâché nests underground, in attics and sheds, or in hollow trees. These wasps have a similar colony structure to Honeybees, with a single queen and a large daughter workforce. The big difference is that worker wasps catch insects for their larvae (usefully getting rid of a lot of pests for us in the process). The adults drink sugary liquids, usually nectar, but will happily lap up soft drinks. It is only when they have become tipsy on the juices of rotting windfalls that they can become a nuisance and you should treat them with caution.

The Hornet is our largest wasp, and looks quite menacing as it steams about over flower borders looking for insect prey. They rarely sting humans, however.

Solitary wasps, such as this digger wasp, tend to be parasites, often laying their eggs on the caterpillars of butterflies or moths.

Spiders and harvestmen

Just the thought of gardening to benefit spiders may seem sheer lunacy to some people. The case for their defence is a compelling one, however, unless you are a complete arachnophobe:

They trap or grab millions of insects each year, many of which are pests of crops

They trap or grab millions of insects each year, many of which are pests of crops

They are themselves vital food for many garden birds.

They are themselves vital food for many garden birds.

Spiders’ webs are used by some birds such as Long-tailed Tits and Goldfinches to help build nests.

Spiders’ webs are used by some birds such as Long-tailed Tits and Goldfinches to help build nests.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: There are more than 600 species of spider in the British Isles. Many species are tiny, but they all have eight legs and a distinct waist. Harvestmen are cousins of the spiders, but with a simple rounded body and with just 23 species in the British Isles.

As with so many other groups of creatures, the further north you are, the fewer species to expect, but most gardens can expect to host dozens.

Habitats: Sunny woodlands, hedgerows and meadows are key habitats, especially near water, but there is a species for almost every habitat. The Woodlouse Spider Dysdera crocata, for example, is a common species of log piles and brick stacks.

Habits: There are several groups of spiders with quite different lifestyles. The most familiar are the orb-weaving spiders that spin the famous spiral webs and need suitable structures from which to hang them. There are many other ways of using silk, however, with many spiders just creating sticky mats or irregular scaffolding.

There are plenty of spiders that don’t use silk, hunting instead on foot. These include jumping spiders and wolf spiders. There are many that hunt at night, too, while the crab spiders sit and wait, often camouflaged in flowers, to ambush prey.

Food: The web-spinning spiders mainly target flying insects, but many of the hunting spiders will target other creepy-crawlies, too, and there are some spiders that specialise in hunting other spiders.

Breeding: Most spiders and harvestmen live for just one season and die at the start of winter. The females leave behind eggs either in a silk sac or in the soil or rotting wood. The eggs hatch in the spring as miniature versions of the adult, and usually soon disperse, either on foot or blown on strands of silk, called ‘ballooning’. A few species live for more than a year and seek warm sheltered places to spend the winter, such as in your bedroom!

So… Gardening for insects equals gardening for spiders which equals gardening for birds. Provide spiders with vegetation, trees, standing water, log piles, hedges – all will boost the numbers in your garden with you hardly noticing them.

The Wasp Spider – here the large and dramatic female – is a recent arrival in southern England, but is fast spreading northwards.

Harvestmen can’t spin silk, and so hunt on foot. They have very long legs, but so do some spiders, so the way to tell them apart is that they have just one main body section, whereas spiders have two.

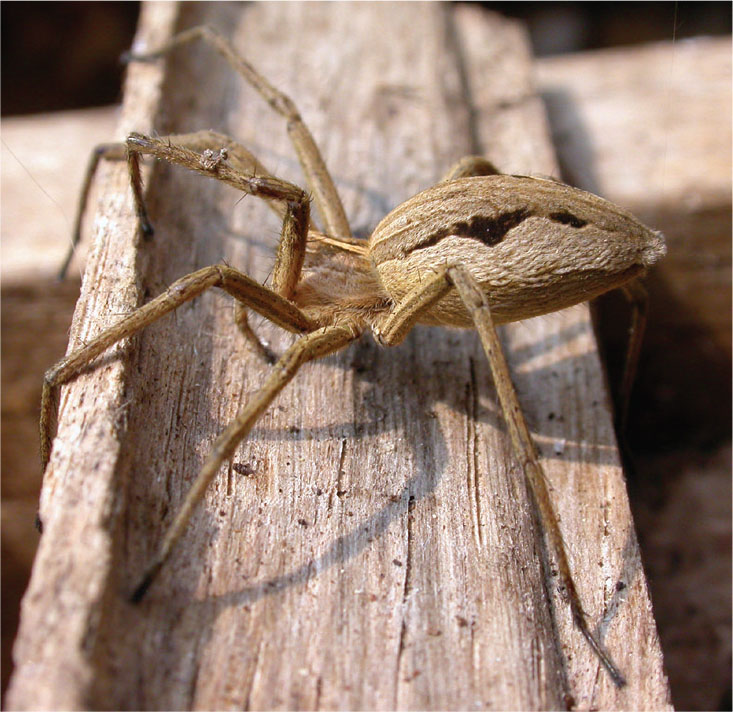

This Nursery-web Spider Pisaura mirabilis is a common garden spider, hunting on the ground for prey. During mating, the male offers the female a gift to distract her and avoid being munched by his bride.

Woodlice

Woodlice are those familiar little creatures that cluster under logs and bricks looking like miniature, silver, armoured tanks with articulated shells. Expose them to the light and there’s panic in the ranks. They have their uses in the wildlife garden, especially in the compost heap.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: There are five widespread species in the British Isles – the Common Rough Woodlouse Porcellio scaber, the Common Shiny Woodlouse Oniscus asellus, the Striped Woodlouse Philoscia muscorum, the Common Pill Woodlouse Armadillidium vulgare and the Common Pygmy Woodlouse Trichoniscus pusillus, with about 30 rarer species and every chance that one or more of these may be present in your garden.

Habitat: Woodlice are crustaceans, related to the crabs and shrimps, but they have found a way to survive on ‘dry’ land by hiding in dark, moist places such as under the bark of dead wood, in compost heaps, and among rock piles.

Habits: They tend to be gregarious, emerging only after dark on damp nights and rarely travelling far. Woodlice are eaten by various spiders, shrews, toads, and just a few birds such as Wrens.

Food: They eat large amounts of dead leaves and other spent organic matter, helping hugely in the decomposition process.

Breeding: Females have an internal, fluid-filled brood pouch where they incubate their eggs.

So… With a compost heap, log pile or ‘habitat’ pile, you should have all the woodlice you need, a little army helping to ensure that you don’t end up knee-deep in dead plant matter.

Turn over any brick or log that has been lying around for a while and you are likely to find harmless woodlice, such as this Common Woodlouse Oniscus asellus, one of your unpaid gardening helpers.

Millipedes and centipedes

They have lots of legs, yes, but there are more to these little arthropods than that. Centipedes are important venomous predators of the micro-world, and millipedes help in the decomposition of plant material.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: There are close on 50 species of both centipedes and millipedes in the British Isles, with at least some species in most areas of the country.

Habitat: They all need to keep out of sunlight in moist dark places such as in the soil, leaf-litter, under logs and stones, and in compost heaps.

Habits: Centipedes are flat, fast, fanged carnivores, hunting prey at speed and grabbing victims with pincer-like, venom-pumping front legs. Millipedes in contrast are generally slow-moving, burrowing vegetarians, with some looking like worms with hundreds of legs, others like woodlice, and others like centipedes!

Food: Centipedes eat caterpillars, spiders, small snails and worms; millipedes mostly eat decaying plant matter.

Breeding: They all lay eggs in the soil; very few show any level of parental care after that.

So… If you create a compost heap, develop a woodland garden, apply leaf-litter as mulch to your flowerbeds and build a log pile, you should be well away.

This is a particularly impressive centipede I found under rotting logs in my garden, which was about 5 cm long. The commonest species are typically 3 cm long or less.

Turning over logs is probably the best way to find millipedes – this one in my garden looked rather like a miniature vacuum cleaner hose on tiny legs.

Pond creatures

Beneath a pond’s surface is a universe in its own right where, throughout the warmer months, all of life’s trials are played out fiercely, day and night.

Earlier in this section we covered the headline-grabbers of the pool: the amphibians, dragonflies and damselflies. There are then usually a dozen or so other types of aquatic wildlife that are easily visible in an average garden pond, coming from all sorts of different animal groups. Here are the commonest with a brief summary of their home needs.

Water beetles and their larvae

The big daddy of them all is the Great Diving Beetle Dytiscus marginalis, which can grow up to 35mm long. Both the adults and the larvae are ferocious enough to kill newts, tadpoles and goldfish. There are several smaller species of diving beetle, all still top predators. Even the several species of whirligig beetles Gyrinus, spinning crazily across the surface, are actually hunting prey.

True bugs

The four UK species of backswimmers Notonecta (below) are also formidable predators for their size. They swim upside-down, skulling with their long back legs and clutching an air-bubble to their chest. They catch prey using a venomous bite (they can give us a sharp nip, but the venom is designed for tiny creatures), and are good flyers.

There are several types of pond-skater Gerridae, which do as their name suggests – the long middle legs provide propulsion, the back ones steer and the front ones grab prey through the surface.

The Water Scorpion Nepa cinerea is a chunky beast up to 20mm long, stalking just under the surface and poking its spear-like rear end through the surface as a snorkel.

Water-boatmen are true bugs which rove the bottom eating plant particles and algae.

Backswimmers are powerful, upside-down rowers, but they are also good flyers, just like the other pond bugs. In fact, the only creatures you need to introduce to ponds are pond snails, because everything else will find its own way there..

Flies

Mosquitoes lay their eggs in rafts on the water surface. Their larvae and bull-headed free-swimming pupae hang down from the surface and wriggle off at your approach.

Midge larvae live in the mud of stagnant water and include the little red maggots (bloodworms) of non-biting Chironomid gnats.

The rat-tailed maggot is the larva of the Drone-fly Eristalis tenax and lives in stagnant water with a long breathing tube of a tail.

Caddis-fly larvae

Several species crawl about on the pond bottom, eating tiny fragments of whatever they can find and hiding in little home-made cases.

Molluscs

The Great Pond Snail Lymnaea stagnalis with its pointed spiral shell and the ramshorn snails Planorbis with their coiled discs are grazers, munching through algae.

Crustaceans

Gammarus is a genus of what are sometimes called ‘freshwater shrimps’ that are very common in ponds, wriggling about in the debris on the bottom and eating detritus, but they are strong if apparently lop-sided swimmers when disturbed.

The waterlice or hoglice of the genus Asellus are like small underwater woodlice with overlong legs. They too are cleaners, sifting through the pond’s ‘rubbish’.

There are two groups of fascinating microscopic crustaceans that are abundant in ponds. The name ‘water flea’ doesn’t do justice to the genus Daphnia, which cluster in large shoals and when magnified look like limbless, see-through jellybabies with horns. Cyclops is a club-shaped swimmer with four big horns, one eye, and egg sacs dangling from the hip. They all filter microscopic plankton.

So… All of these creatures have subtly differing needs, but you can accommodate many of them by creating a large pond with parts in sun and parts in shade, with deeper areas and plenty of shallows, with different substrates such as pebbles and gravel, and plenty of aquatic vegetation. However, keep rich organic material such as soil and leaves to a minimum if you want to reduce the risk of stagnant conditions and algal blooms.

Earthworms

Earthworms are the unsung heroes of your garden. Their design is simple – a muscular tube that eats its way through the soil. Earth and dead leaves go in the front end, travel down the gut and come out the other end partially digested. Each worm alone makes little difference, but a million or so per hectare in good habitat move mountains of soil and are vital for the decomposition of organic matter.

This activity is hugely beneficial to plants: it aerates the soil, aids drainage and gives roots channels they can easily penetrate. Worms also help break down organic matter making it more available to plants, and they bring essential minerals back to the surface in their wormcasts.

And, of course, worms feature in many creatures’ diets. To thrushes, Badgers, Hedgehogs, shrews and amphibians, they are not a delicacy but the main course. Worms are clearly worth nurturing.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: There are about 25 species of earthworm in the British Isles. They are quite difficult to identify, but most are widespread in suitable habitats.

Habitat: Different species tend to live in slightly different habitats, with species such as the Garden Earthworm Lumbricus terrestris, Anglers Red Worm Lumbricus rubellus and the Long Worm Allolobophora longa living under lawns and grasslands, and the Brandling Worm Eisenia foetida and Cockspur Worm Dendrodrilus rubidus in compost heaps, where huge numbers can gather. Worms can be found in most fertile soils apart from those that are very acidic, sandy or waterlogged, with good populations in undisturbed habitats such as unimproved grassland and woodland. Regular turning of the soil exposes them to predators, leading to far smaller numbers in such places.

Habits: Earthworms tend to live in the top 25cm of the soil, going deeper only in dry or cold weather. They usually remain active for most of the year.

Food: Large bits of organic matter are ingested together with soil particles and bacteria. Some worms come to the surface to yank big leaves down into their tunnels where they can soften them and munch in peace.

Breeding: Earthworms mature after about a year, and can then live for ten if they can avoid your Blackbirds! They are hermaphrodite, finding a mate in late summer either on the surface or within a burrow. They lie alongside each other, head to toe, and exchange sperm. Each then lays a cocoon of about 20 fertilised eggs in the soil.

So… Building up a healthy population of earthworms is clearly great for wildlife in the garden. Lawns, meadows and undisturbed woodland floors are preferable to turned soil, which is in turn better than concrete, gravel and decking. A compost heap that worms can get into will help too. In the vegetable patch, leave a fallow plot in your crop rotation.

It is best to clear autumn leaves off a lawn as they will otherwise smother and kill the grass, but a top-dressing in autumn that includes sieved leaf-mould and soil will help worms no end.

WORMS AND LAWNS – NUISANCE OR FRIEND?

I realise that not everyone loves the humble worm. Groundsmen and aficionados of ‘the perfect lawn’ see them as a curse because of the casts that Allolobophora worms leave on the surface. Some people find these unsightly, and they do offer a place for weeds to germinate. As a result, worm-killing chemicals are still widely used, but the tragedy is that these kill all earthworms, not just those that make casts. A lawn without worms will then need much more spiking and fertilising than one with, and will be far worse for wildlife in general. Anyway, it is no big deal to brush the wormcasts in once dry, so I’d like to think that everyone can learn to love the worm and all the benefits it brings!

A good compost heap can squirm with tangled masses of Brandling Worms.

Slugs and snails

So what are you going to do to encourage slugs and snails in your garden? (Cue: shrieks of horror from aghast readers whose strawberries, hostas, potatoes, etc, they endlessly devour.) Don’t worry; read on to find ways of controlling them without harming other wildlife.

But I’m going to be brave and start with a little plea: they are a natural part of our environment and a key link in food chains. Clearly the countryside survives with them, so maybe if we understand their home needs we can work out how to better live with them.

HOME NEEDS

Distribution: Snails and slugs are found pretty much everywhere, but the number of species thins out quickly as you head north.

Habitat: Of the 80 or so species of snail in the British Isles and 30 or so slugs, most live in damp habitats such as woodland, but a few have found ideal conditions in our gardens. Snails are especially common on lime-rich soils, as the minerals there are important building materials for their shells.

Habits: Slugs and snails are molluscs, the group that includes seashells, but they have evolved to survive on land. Nevertheless, they still need damp conditions, and so escape becoming sun-dried by hiding by day under logs and stones and, in the case of many slugs, burrowing deep into the soil. In very dry spells, snails will seal themselves into their shells with a dried layer of mucus. Most people don’t realise that some species, such as the attractive yellow-and-brown whorled Brown-lipped Cepaea nemoralis and White-lipped Snail C. hortensis, are more help than hindrance, preferring to eat dead and rotting vegetation or fungi rather than living plants. See them as friends!

The main problem species are:

Garden Snail Helix aspersa, the big one up to 40mm across with brown flecks

Strawberry Snail Trichia striolata, a small, rather flattened snail to 14mm diameter

Grey Field or Netted Slug Deroceras reticulatum, grey with darker flecks to 40mm long, which prefers feeding on the surface

Garden Slug Arion hortensis, to 30mm long, dark with a pale stripe down the side; a burrower

Keeled or Budapest Slug Tandonia budapestensis, to 60mm, with an orangey stripe down the middle of the back, also a burrower, and Large Black Slug Arion ater, up to a whopping 200mm long, often black with an orange stripe along the foot, and really just a problem with seedlings.

Breeding: Slugs and snails are hermaphrodite, with every individual having both sets of sexual organs. All are able to mate with any other of their species and all then lay eggs. These are deposited in loose soil, 30–80 at a time, up to six times a year, and are pale, rather jelly-like and round.

COPING WITH SLUGS AND SNAILS

Grow plants that snails and slugs avoid; many herbs and other aromatic plants are an ideal place to start.

Grow plants that snails and slugs avoid; many herbs and other aromatic plants are an ideal place to start.

Place slug and snail hideaways (rock and log piles, compost heaps) away from vulnerable plants.

Place slug and snail hideaways (rock and log piles, compost heaps) away from vulnerable plants.

Seedlings are most at risk, so propagate them indoors and plant them out when well advanced.

Seedlings are most at risk, so propagate them indoors and plant them out when well advanced.

Grow vulnerable vegetables in raised pots, and harvest potatoes early.

Grow vulnerable vegetables in raised pots, and harvest potatoes early.

Use cloches made of plastic drinking bottles pushed into the soil around small plants.

Use cloches made of plastic drinking bottles pushed into the soil around small plants.

They don’t like anything that dries their mucus, so lay barriers of crushed eggshells, soot, sharp sand, bran, woodash and human hair. None are guaranteed to work, but all should have some effect.

They don’t like anything that dries their mucus, so lay barriers of crushed eggshells, soot, sharp sand, bran, woodash and human hair. None are guaranteed to work, but all should have some effect.

Lure them with their favourite things, such as upturned half grapefruits or wilting cabbage leaves, and then relocate them to places where they aren’t a problem.

Lure them with their favourite things, such as upturned half grapefruits or wilting cabbage leaves, and then relocate them to places where they aren’t a problem.

Use copper tape and sheets of matting impregnated with copper to give them a mini-electric shock.

Use copper tape and sheets of matting impregnated with copper to give them a mini-electric shock.

If you must kill them, give them a nice way to go! Sink jars full of bitter ale into the ground. Keep the rim 2cm above the soil surface to avoid killing ground beetles, and cover with a raised stone ‘lid’ to avoid the risk of tipsy Hedgehogs and pets.

If you must kill them, give them a nice way to go! Sink jars full of bitter ale into the ground. Keep the rim 2cm above the soil surface to avoid killing ground beetles, and cover with a raised stone ‘lid’ to avoid the risk of tipsy Hedgehogs and pets.

Slugs and snails – such as this Large Black Slug – tend to be one of the gardener’s biggest nightmares. For creatures that move so slowly, they manage to get everywhere under cover of darkness to cause havoc.