Wine and Technology

Wine has always been a product of technology, and winemaking as we are familiar with it could not have been developed until ceramic expertise was harnessed for economic purposes during the New Stone Age. Today winemaking is a high-tech industry. But we were absurdly gratified recently to obtain a bottle of a wine that had been made in a simple clay vessel buried in the cool earth, just as was done with the very earliest wines about six to eight thousand years ago. Made in the eastern Caucasus from the venerable Rkatsiteli grape, this bone-dry pale-amber wine had an astonishing freshness to it, with a muted nutty fragrance that seemed to reach out across the millennia.

For centuries, winemakers were typically impoverished farmers who employed age-old methods using ancient equipment in gloomy cellars that were often shared with sheep, cattle, and geese. During the eighteenth century the general level of economic activity in the fabled wine-producing region of Burgundy was so low that entire villages would go into virtual hibernation during the winter. Even in more prosperous wine-exporting areas such as the Bordelais, winemakers tended to do business much as their predecessors had done since time immemorial: most grapes were made into wine purely for domestic consumption, or to sell in bulk to shippers. It was those merchants and other city dwellers, not the vine farmers, who built the impressive nineteenth-century chateaux that dot the countryside of the Médoc. In all but the most prestigious appellations, the wines themselves tended to be hit-or-miss, and were often oxidized, or coarse, or thin and acidic. Apart from being alcoholic, their main benefit was that they were usually safe to drink.

During the twentieth century everything changed as modern technology intruded, though the first material incursion of science into winemaking had already occurred in the nineteenth century, when Louis Pasteur demonstrated that bacterial growth was responsible for many kinds of spoilage. Previous advances in winemaking had been the result of trial and error, but Pasteur preached that knowledge of process could serve as a guide to procedure. Earlier, the French polymath Antoine Lavoisier had figured out the basic chemistry of fermentation, and the Italian scientist Adamo Fabroni had shown that in wine this process is implemented by yeast; but it was Pasteur who discovered in the 1860s that fermentation of wine involved an ongoing interaction between the yeasts and the sugars in the must. He also demonstrated that, despite the traditional addition of sulfur salts to discourage this, the yeasts could be overwhelmed by rapidly multiplying bacteria if too much oxygen was present. This led to his key message: to produce good wine, as much oxygen as possible had to be excluded from the process. One immediate result of Pasteur’s dicta was a great advance in the quality of sparkling wines, as winemakers regularly began to add sugar and yeast after the primary fermentation to guarantee a second fermentation in the pressure-resistant bottle. But for the most part, the ravages of phylloxera late in the nineteenth century postponed significant technological advances in wine production until well into the twentieth.

In the first half of the twentieth century the general quality of wines improved in all major wine-producing regions except the United States, where Prohibition brought progress to a halt. The quality of the average wine was enhanced largely through a general upgrading of vineyard and cellar management that was propelled, in part, by the establishment in several countries of appellation laws. These specified, for a particular region or appellation, and in greater or lesser detail, which grapes could legally be grown, how vineyards were to be managed, and how the grapes could be vinified if the wine was to bear the appellation’s seal—and thus sell for a higher price. But rather than spur innovation, these rules tended to entrench the best existing practices—and may still act as something of a brake upon innovation.

Significant new winemaking methods had to await the period following World War II, when professional schools of wine science finally began to exert widespread influence. In France, the science of oenology dates back to the establishment of the still-revered Jules-Émile Planchon’s institute of vine science at the University of Montpellier in the 1870s. But during the past century, the country’s most famous oenologist was Émile Peynaud, of the University of Bordeaux.

Peynaud, whose career spanned the first half of the twentieth century, was not just a laboratory investigator; he was a tireless adviser to numerous wine producers in the Bordelais and ultimately worldwide. He created the role of consulting oenologist (though emphatically not that of the celebrity “flying oenologist” cultivated by some of his students) that is crucial to the wine world today. An indefatigable experimenter, Peynaud believed that winemaking was not an art but a science, and he insisted that those he advised adopt new methods that, while expensive, resulted in many improvements. He started in the vineyard, where he vigorously advocated limiting the yield by pruning and by discarding excess or poorly ripening bunches of grapes. He required vignerons to carefully monitor the ripening process and to pick the grapes at the optimum moment. When he began his career, most grapes in the Bordelais were being picked far too early. This practice decreased the risk that problems due to weather would be encountered before harvest, but it also meant that many wines were weak, thin, and acidic. Peynaud changed all these protocols. In addition, he preached that only the best bunches should be used for the best wines. Grapes from a particular corner of the property, or from one vine rather than another, might be used to produce the estate’s flagship product, while others might receive “second” wine status. Peynaud’s approach involved laborious and expensive sorting of the grapes, but it paid off handsomely at the top end.

Peynaud was also active in the winery after the grapes had been crushed. He insisted on strict standards of hygiene to prevent bacterial growth, and he encouraged winemakers to replace the ancient oak barrels that had typically been used for aging wines. But above all, Peynaud believed in controlling the heat produced during fermentation. We noted in Chapter 6 that at excessively low temperatures yeast will become inactive and at high ones hyperactive, and Peynaud was adamant about maintaining ideal fermentation temperatures. His philosophy often mandated the abandonment of traditional large oak fermentation vats in favor of today’s ubiquitous stainless steel fermenting tanks, individually equipped where necessary with cooling coils or jackets—a technology initially developed in the Champagne region. Typically, such temperature-controlled vats are used not only during fermentation itself but also beforehand to cool the must and afterward to provide a stable environment for the young wine.

One special advantage of such equipment has been to allow high-quality wines to be made in regions such as Algeria, and even parts of southern France, that would otherwise be too hot to produce anything but the traditional plonk. Another favorite strategy of Peynaud’s, at least for certain wines, involved following the initial fermentation by an additional “malolactic” transformation. Implemented by inoculating the fermented must with bacteria that convert harsh malic acid in the wine to smoother lactic acid, this transformation comes at the expense of the wine’s acid backbone, and sometimes of the aromatic compounds present. Occasionally such softening happens naturally, but because of the tradeoffs involved, until Peynaud came along it had been mostly considered a problem. Nowadays, the virtues and vices of malolactic fermentation in specific circumstances remain a favorite subject of debate.

Peynaud’s introduction of a scientific perspective into the ancient craft of winemaking resulted in a revolution in the quality of Bordeaux wines, with reverberations among winemakers around the world. The top clarets became better and more reliable year after year, as producers took his advice to heart, and the quality of the lesser wines from Bordeaux—and ultimately from elsewhere—rose along with them. In later years, this result was amplified by the effects of the commercial transformation of the wine industry in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Though Peynaud towered over his contemporaries in influence, if the United States had an oenological sage of equivalent stature over the postwar period, it was Peynaud’s almost exact contemporary Maynard Amerine, a professor at the University of California, Davis. He, too, was an academic with his feet firmly in the outside world, consulting for numerous California wine producers as the industry began its renaissance following Prohibition and the tribulations of World War II. Amerine’s particular specialty was climate and vines; before the war, working with his older colleague Albert Winkler he had already determined that the same vine stocks produced different wines in different places, and that the most critical variable appeared to be temperature. Regardless of varietal, cool-country grapes took longer to ripen. They were also leaner, more acidic, and more deeply colored and extracted. Grapes grown in warmer places ripened faster and had higher sugar contents. At the same time, certain varietals did better in particular temperature ranges than in others. Using what became known as the “Winkler Scale,” Winkler and Amerine produced a map that indicated on the basis of temperature zones which varietals were best adapted to which regions of California. After the war, besides turning his interests toward the sensory perception of wine, explored in his Wines: Their Sensory Evaluation, Amerine energetically advised numerous up-and-coming California winemakers on where to plant which varieties, and trained many of the winemakers who eventually fanned out over the state to create the California wine industry as we know it today.

Émile Peynaud (left) and Maynard Amerine

The impact of all these wine scientists’ efforts in the postwar period was twofold. Viticulturists grew more attentive to which varieties to grow given the locations of their vineyards, as well as to how best to grow and manage them. Winemakers, meanwhile, began to exert more control over the transition from grape to wine, carefully monitoring every stage of the process and intervening when they detected deviations from the desired course. As a result, in the early twenty-first century few wines are left to “make themselves.” Every winemaker with pretentions to quality has at his or her disposal laboratory facilities for real-time tracking of everything that happens in the vineyard and the winery. Even before the vineyard is planted, vine growers determine the optimum spacing of the vines, depending on variety and conditions. With careful pruning, and sometimes culling, they reduce the amount of fruit on each stem to increase the plant’s investment in each berry that remains. Viticulturists interested in making the most concentrated wine possible from their grapes might routinely discard a full third of the berries before allowing the rest to ripen. Foliage might be removed to increase the individual grape bunches’ exposure to the sun. Ripening grapes are regularly monitored for sugar and phenolic levels, and at top vineyards picking may be done in stages, so that only completely mature grapes are harvested.

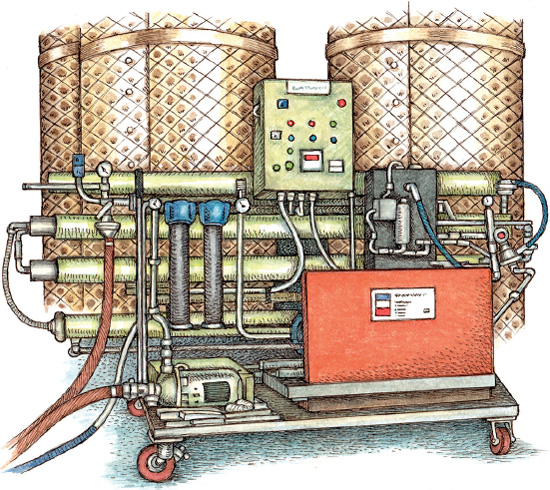

But today, if the best time for picking has been misjudged, or if bad weather threatens a harvest, technology will come to the rescue. To avoid weak coloration or flavors or aroma in the wine, or simply to increase the extract, the grapes can be “cold-soaked” under refrigeration before fermentation begins. Or reverse osmosis can help later in the process, by removing any volatile acidity or excess alcohol. Prior to fermentation, the reverse osmosis machine can also be used to eliminate from the must any excess water due to a rainy harvest—unless a vacuum evaporator has already achieved the same goal. Ultrafiltration will clarify the wine, and can also be used to remove oxidized phenolics. It will also take care of excessively bitter tannins, unless the winemaker prefers to damp those down by microoxygenation—a small amount of oxygen, in the right place at the right time, can actually help produce a soft and supple wine. Electrodialysis can adjust tartrate levels and acidity, and eliminate unwanted potassium. And so on. Before the advent of such modern technologies and practices, the best way to compensate for variations in grape quality from year to year was to adjust fermentation time and the blend of differently ripening varietals. Now all bets are off.

The armamentarium of interventions available to a winemaker nowadays is almost endless. Still, although technology is readily available to compensate for most problems encountered in viticulture, one thing remains unchanged: if the practices in the vineyard are right, less intervention will be needed to ensure that the wine turns out as the winemaker wishes. Nonetheless, at some point the wine has to mature, and even if the must is exactly as desired, there are many choices to make. The basic decision is whether to mature the wine in an inert material such as stainless steel or glass, with which it won’t interact, or in wood, almost invariably oak. If the latter route is chosen, many varieties of oak are available, differing in tightness of grain, embedded compounds, and other variables that will affect the wine. Small barrels of around 225 liters capacity have become the norm, but winemakers must still choose between having barrel interiors that are strongly toasted or not. Coopers traditionally bend the staves of their barrels over a fire, and some flame-char the staves more than others do, a practice that will affect the barrels’ influence on the wine. Another decision for winemakers is how often to change the barrels, because extract is lost with each usage. How long to leave the wine in the wood is also an issue: the longer the wine resides in the barrel, the more compounds it will absorb and the longer it will be exposed to tiny amounts of oxygen diffusing from the outside. Longer is not necessarily better—the choice is basically an aesthetic one—but if the winemaker is in a hurry, or the cost of new barrels is an issue, oak chips or worse can be added.

Reverse osmosis machine in a winery. Employing a sophisticated technique for filtering small molecules from newly fermented wine, machines like this one are often used to extract excess water due to rain near harvest time, to remove unwanted flavors, or to lower unduly high alcohol levels.

Émile Peynaud was often attacked on the grounds that his scientific prescriptions amounted to an industrial formula for a soulless, standardized product. But in reality, this acute observer was exquisitely aware of terroir, as well as of the pitfalls of bad vine growing and winemaking, and he insisted that method be accommodated to place. What’s more, his approach resulted in dramatic practical improvements: Peynaud’s efforts unquestionably elevated the overall quality of wines made around the world, as much at the bottom end of the market as at the top. We are much better off for them. Still, Peynaud’s insistence on rigor has produced a strong temptation among some to believe that there is an optimum procedure—and even an optimum product—in winemaking, an idea that was subsequently reinforced by the Parker generation of critics. It’s certainly true that if the winemaker uses the formidable technology available to match an ideal set of parameters in the fermenting must, the wine will probably be good but is unlikely to be particularly interesting or innovative. This is one reason that, while table wines today tend to be of a much higher standard than their predecessors of half a century ago, they also tend to be more uniform.

Still, the scale of production also makes a huge difference, and it is remarkable how reliably large-scale winemaking operations can produce a standard product from grapes brought in from many different vineyards, sometimes kilometers apart, and make it consistent from bottle to bottle and year to year. For a large producer developing or maintaining a brand, this consistency is important. But it will come at the cost of nuance. Remarkably good wines have been produced on an industrial scale, but no great or truly exciting ones. The ones that really engage your attention are invariably produced in small lots, usually from specific places. Under such conditions the winemaker is able to handle each batch as the individual entity it is, and tailor its treatment to its specific characteristics. Providing this intensive care is not simply a function of the winemaker’s intuitive genius and experience. It also requires the ability to charge enough for the wine to cover the high costs incurred without the economies of scale available to large producers.

Love the new approach or loathe it, adding climate science and chemistry to the traditional pursuits of wine production has inevitably shifted the balance between grape and terroir, and between terroir and control. As particular places became identified by the grape varietals that could or should be grown there, terroir as an abstraction has lost a bit of its mystique, while the grapes themselves have become to some extent subordinated to technological manipulation. For example, much to their chagrin, at a 1976 blind tasting in Paris a French panel of judges had extreme difficulty in discriminating top white Burgundies and red Bordeaux from Chardonnays and Cabernet Sauvignons produced in California. Even worse, a Cabernet from the Napa Valley took top honors. Paradoxically, the California winemakers had consciously been striving to emulate French models, which made their triumph something of a backhanded compliment to their cisatlantic colleagues. But the result was also evidence of a growing international convergence of style, something that was made possible by the increasing dominance of modern technology. Such developments engendered a wistful sense of loss among many, as commentators began to deplore the globalization of wine during the waning years of the twentieth century.

Naturally, there are still many mavericks who buck the trend: people like Josko Gravner of Friuli, on the border between Italy and Slovenia, who makes his highly regarded wines in huge clay pots buried in the ground, as his remote predecessors did in antiquity; or his neighbor Stanko Radikon who, emulating his grandfather in equipment if not in processes, macerates his white wines for several months in huge tapering oak vats. Both these radical departures from current best practices are taking place in the small town of Gorizia; and it is winemakers like Gravner and Radikon, in viticultural regions all over the world, who are making today’s most interesting wines—albeit not always wines that are to everybody’s taste, or even that their greatest fans would want to drink every day. Still, however unconventional they and their products may be, the majority of today’s innovative winemakers are acutely conscious of terroir—of the patches of land to which they are both economically and emotionally attached. And their labors have shown that technical perfection in the making of wines can actually allow terroir to express itself to greatest advantage.

Nonetheless, some undeniably great wines, like the Grange Hermitage produced by Penfolds in Australia, deliberately shun the idea of terroir as defined by a specific place. The producers of Grange make a point of assembling the best Shiraz grapes from prized but widely separated vineyards, with the aim of allowing the character of the varietal to dominate (though small quantities of other grapes are sometimes also included nowadays to add balance where needed). Grange is a powerful and highly individual wine, unlike anything else, including top Shiraz-based but single-block wines made nearby, such as Henschke’s almost equally legendary Hill of Grace. The message of both is that technological perfection need not get in the way of either terroir or varietal character. Idiosyncrasy of place, or of grape, need not be lost simply because the winemaker has gone to great lengths to avoid procedural mistakes.

At the other end of the spectrum, the endless meddling in the wine production process that technology now facilitates has made possible the marketer’s dream: a global standardization of wine in a style appealing to a mass clientele. It is a triumph of technology that so much decent, drinkable wine can be produced on the vast scale on which the wine industry now operates, especially when compared to the seas of plonk produced in the past. But while those workmanlike wines are easy to enjoy, especially with food, they are far from what the very best handcrafted wines, grown in specific situations and individualistically vinified, have to offer. A good wine and a perfect one are worlds apart, distinguished not only by terroir and labor-intensive attention but also by a high degree of artistry. Nonetheless, those of us who love the element of surprise in wine have much to hope for as science advances. Science is no enemy of originality and subtlety in wines; as long as it is used to enhance the quality of the original grapes, rather than to disguise problems originating in the vineyard, we can hope for further serendipitous discoveries.

No account of wine’s place in science or human experience can avoid the subject of fraud. For, as long as certain wines have been judged to be superior to others, there have been fakes. Greeks and Romans frequently complained about the manipulation and mislabeling of wines. Pliny the Elder, for one, was vexed by a superabundance of fraudulent wine: at one time there was so much Falernian sloshing around in ancient Rome that most of it couldn’t possibly have been genuine. In the fourteenth century Chaucer urged caution on wine buyers, especially when purchasing Spanish products, while during his sojourn in Paris the claret-loving Thomas Jefferson rapidly learned the wisdom of buying directly from the vineyard instead of trusting to the wiles of wine merchants. Indeed, it is to Jefferson’s time that we may trace the origins of what we might call the modern period of wine fraud. By the late eighteenth century, when Jefferson was developing his buyer’s instincts, winemakers had started using easily stacked cylindrical glass wine bottles, sealed with corks. Correspondingly, British aristocrats in particular had begun the practice of laying down bottles of long-lived wines—top clarets, Madeiras, Ports, Hocks, some Burgundies—for later consumption: a tradition that had begun after it was discovered that some wines continued to develop complexity in the bottle.

This evolution of the wine occurred as the oxygen in the air trapped below the cork—and to a minor extent diffusing through it—interacted with the compounds in the wine. Tough, highly extracted wines such as those produced in Bordeaux benefited particularly from being cellared, as the alcohols and acids in them softened and the tannins began to separate out. Although such wines were initially intended for later consumption by the purchaser or his descendants—you laid wines down for your grandson, even as you drank your grandfather’s—the new form of packaging eventually created the conditions for a secondary market to develop, as bottles of older wines became rarer and more valuable. This was when the labels started to become as precious as what was in the bottle itself. In a traditional winemaker’s cellar bottles were—and are—stored unlabeled, identified purely by the location of the bins in which they reside. Hence the presumably apocryphal, but certainly venerable, story of the cellar boy who came running up the stairs crying in a panic, “Master! Master! The cellar has flooded and the bottles are floating everywhere!” at which the cellar master calmly smiled and said, “No need for alarm, young lad. The labels are all safe and dry up here in my desk!” There was no such luck in a New York City wine warehouse during Hurricane Sandy, in which flooding has led to litigation that is likely to run on for some time—especially because it turned out that the wines were not insured. But the lesson is clear: from time immemorial there have been opportunities for substitutions and malfeasances along the supply chain leading from producer to consumer. And the invention of the bottle offered a range of new possibilities.

In the mid-twentieth century, two trends intersected. First, many members of the postwar aristocracy found themselves under financial stress but in possession of a lot of old wine. This fact did not escape the attention of auctioneers, who energetically cultivated the second trend, in which older top clarets and other age-worthy wines, preferably pre-phylloxera, were becoming increasingly sought after by collectors. During the 1960s appetite for these wines grew enormously, as reflected in skyrocketing prices at auction—despite the growing probability that the wines would be well past their prime because, no matter how hard and tannic a wine is to begin with, or how beautifully it may evolve in the bottle, eventually age takes a toll. Wines do not live forever. But in a larcenous world skyrocketing prices for what were basically prestige items, not necessarily destined to be drunk, made deception more profitable and less likely to be detected, and some notable scams began to stand out against the more usual minor fraud.

Thomas Jefferson himself figured in the most notorious recent scandal, entertainingly chronicled by Benjamin Wallace in The Billionaire’s Vinegar. During the middle 1980s, a few ancient-looking bottles of wine from the Bordelais began to appear at auction and at select tastings attended by a coterie of well-to-do wine fanatics. What made these bottles remarkable was not just their age—they were marked with the years 1784 or 1787—but that the initials “Th. J.” were also engraved on them. Hardy Rodenstock, the German collector who put them up for auction, claimed not only that they were part of a cache discovered in a walled-off cellar during the demolition of a house in Paris, but that the initials stood for “Thomas Jefferson.” Here, by implication, were bottles that had been destined for Jefferson but had not reached him by the time he left Paris for the United States in 1789. Although Jefferson experts at Monticello declined to authenticate the bottles, the claimed provenance was largely responsible for the first of them, a 1787 Lafite, selling in London, at the end of 1985, for the equivalent of $156,000: four times as much as had ever been spent previously on a bottle of wine. The buyer was the American publishing magnate Malcolm Forbes, who put the wine on public display under hot exhibition lights, with the well-publicized result that the cork shrank and fell into the wine. Forbes had apparently not planned to drink the wine, but after this unfortunate incident nobody will ever know what that putatively ancient—and certainly monetarily precious—liquid tasted like.

One of Hardy Rodenstock’s “Th. J.” wine bottles, sold at auction to Malcolm Forbes and never drunk

With great fanfare, Rodenstock next produced a 1787 Mouton from the Jefferson cache at a private tasting held, in 1986, at the chateau itself. All in attendance pronounced it a great wine, still drinking well and developing in the glass. After this triumph, Rodenstock returned to the auction circuit with a 1784 Chateau d’Yquem, a Sauternes that, as an intensely sweet wine, had in principle the best chance of the lot of drinking well after two centuries. And although the authenticity of the Lafite sold earlier remained a matter for dispute, the Yquem went for a hefty $57,000. Now fast forward, via more sales and tastings, to a “supertasting” of 115 vintages of Lafite held in New Orleans in 1988, and for which Rodenstock supplied a bottle of the 1784. The wine was judged a disaster. Reportedly it was not simply oxidized, as were some other old Lafites; rather, it was qualitatively different. It was dark and acidic, and it didn’t gracefully die in the glass, as an oxidized great wine would be expected to do. Many were puzzled, but the unfazed Rodenstock shortly afterward privately sold four more bottles from the Jefferson cache, plus some other eighteenth-century wines, to the hugely wealthy collector Bill Koch. The total value of the deal, completed through intermediaries, may have been close to $400,000.

As time passed Rodenstock’s wine business blossomed, his discoveries of old wines became if anything even more extraordinary, and the tastings he supplied became increasingly rarified and extravagant. At the same time, doubts about the authenticity of his wines grew in some quarters, perhaps contributing to a general decline in the prices paid for old wines at auction as the 1980s came to an end. Eventually an appraisal of one private cellar that had been largely sourced from Rodenstock revealed a high proportion of probable fakes. These included one of the Jefferson bottles—a 1787 Lafite—that was sent to a laboratory for testing. While the sediment in the bottle was shown to have characteristics compatible with a two-hundred-year-old wine, the liquid itself yielded tritium and radiocarbon levels suggesting a much later origin, in the 1960s or 1970s. After these findings, the wine’s German owner was prepared to concede it was a fake, a new wine in an old bottle that had retained its sediment. But even as legal actions and counteractions were launched, and more scientific testing was done, Rodenstock himself continued to prosper.

A significant change occurred in 2005, when Bill Koch began to have doubts about his four Jefferson bottles. He hired a private investigator, who discovered that the engraving on the bottles had been done with a modern dental drill. Other apparently incriminating circumstantial evidence emerged, and Koch brought suit directly against Rodenstock in New York City. The suit was thrown out in 2008 because the court decided it did not have jurisdiction; but by then the gig was up. Both Rodenstock and many luminaries of the wine world found themselves discredited, and even now both the legal and the sensory ramifications of the saga are far from being sorted out.

As Wallace emphasizes in his book, the key to such sorry tales, as so often in confidence trickery, lies in the willing collaboration of scammer and victims. Ignoring warning signs that had been available even before the first Jefferson bottle was sold, some of the most distinguished palates in the wine world had pronounced the fakes to be outstanding wines, elegant and durable representatives of their improbably remote period. Clearly, far too often the story was not the wines themselves but what their drinkers wanted them to be. The human brain is a mysterious organ, making connections that may or may not accurately reflect reality.

But the Rodenstock affair is only the best-publicized and longest-running of many such sagas. As long as collectors are prepared to pay enormous prices for rare bottles of wine, there will be those willing to supply them, whether genuine or not. Opportunities for fraud abound, particularly among top wines from the later decades of the twentieth century that continue to soar in value, and are contained in undistinguished, machine-made bottles. To make it even easier for counterfeiters at the highest end, rumors abound that there are nowadays precise recipes available for faking almost any kind of wine. Even simpler, though, it is also possible to give an old wine a new identity with a sought-after label, either forged or recovered from an old bottle. Indeed, it is nothing short of amazing how cavalierly the forging of labels has been done: sometimes bogus labels can be identified simply from spelling errors. Still, a few top producers are now guarding against forgery by incorporating markers into their labels, much as banknote printers do, and by using stronger glue to attach them to the bottles. Bottles are also being made more distinctive.

One of the most recent old-wine scandals has Rodenstockian resonances—though in financial terms the ante has by now been considerably upped. In 2003 Rudy Kurniawan, an Indonesian wine connoisseur with a reputedly awesome palate, burst onto the southern Californian megatasting scene. He quickly contrived to establish an almost gurulike presence among the nation’s elite wine consumers, even as he entered the auction market, initially as a conspicuous buyer of rare wines (which helped drive up prices) and later as a major consigner of sought-after wines from Burgundy and Bordeaux. At two New York auctions in 2006, the contents of a cellar widely believed to have been his grossed a world-shattering, and frankly ludicrous, total of over $35 million. Once the shock had worn off, the sheer superabundance of rare wines at these auctions raised questions; by 2009, doubts hovered over the authenticity of any wine that had passed through Kurniawan’s hands. The Indonesian had by this time stopped taking even elementary precautions, consigning to auction several lots of a wine that had not begun production until several years after the vintage indicated on the bottles. So blatant was this fraud that the proprietor of the vineyard concerned felt compelled to be present at the auction to ensure that the bottles claimed to be from his grapes were not sold.

Early in 2012, FBI agents raided Kurniawan’s home in a Los Angeles suburb and found a trove of what they described as wine-counterfeiting paraphernalia. Evidence included a corking device, numerous foil capsules, hundreds of fake labels for wines dating back to the nineteenth century, and records indicating the purchase of large quantities of inexpensive Burgundy wine. In December 2013 Kurniawan was found guilty on two counts of mail fraud, and in 2014 he was sentenced to ten years in jail. Meanwhile, the world of super-grandiose wine-collecting and flashy wine-swilling once again has egg on its face, while—inevitably—the Kurniawan episode has been supplanted by newer scandals.

But before we conclude that wine counterfeiting is a problem encountered only by the rich and ostentatious, consider other relatively recent instances of wine fakery that have affected less prominent people. In 1985, Austria’s export wine industry almost went under after it was discovered that a few wine producers had added small quantities of diethylene glycol (used in many brands of automobile antifreeze) to their white wines. They had taken this step to boost the apparent sweetness and body of otherwise thin and acidic wines, and thus make them more appealing to unsophisticated wine drinkers in neighboring Germany. No wine drinkers were harmed by the ethylene, and the consequent restructuring of its wine industry ultimately led to a huge increase in the quality of wines produced in Austria. But the next year, in Italy, at least twenty people died after drinking cheap wines that had been adulterated with methanol to raise their alcohol levels.

Even the most distinguished winemaking regions are not immune. In 1973, just as the fine-wine boom was beginning, the long-established Bordeaux firm of Cruse & Fils Frères, proprietor of the Cinquième Cru Château Pontet-Canet, found itself caught up in a scandal that involved falsified records which allowed ordinary red table wines to be mislabeled as Appellation Contrôlée Bordeaux. Although not personally concerned in the scandal, the family patriarch, Herman Cruse, committed suicide, the business was disgraced, and the château was lost, while consumers discovered that they had paid high prices for an inferior product. By 1998, when prices had increased yet more, another prominent claret producer, the Troisième Cru Château Giscours in the heart of Margaux, had also become embroiled in scandal. The property was accused of diluting its second wine of the 1995 vintage with wines from different years and regions, and of adding adulterants such as milk and fruit acids. Two employees were indicted, but the result of the litigation was never made public. Despite such episodes, Bordeaux prices have continued their inexorable rise.

One of the latest furors has hit Bordeaux’s great rival region, Burgundy. In mid-2012 it was announced that the French authorities had begun investigating one of Burgundy’s largest wine producers and shippers, the house of Labouré-Roi, on charges of fraud involving a staggering 1.5 million bottles of wine destined to be sold to consumers all over the world. Charges included blending in wines from external appellations, topping up fermenting musts from highly reputed vineyards with cheap table wines, and mislabeling. It is significant that the alleged fraud was discovered not through sensory evaluations, but by an audit that revealed that the physical volume of Labouré-Roi’s wines had remained constant despite the expected losses to evaporation. Still, the large scale of the reported scam was hardly unprecedented, even for a prestigious appellation; in 2008 it was alleged in the Italian press that possibly millions of liters of wine marketed under the expensive Brunello di Montalcino label had not been made from 100 percent Sangiovese grapes as required by law, but were cut with cheaper grapes brought in from outside Montalcino. This “Brunellopoli” scandal reverberated so widely that the U.S. government threatened to ban all Brunello imports that could not be proven by laboratory testing to be pure Sangiovese.

The threat was not an empty one, because at least in theory it is possible to test for both locality and varietal. Each vine-growing region has a unique stable isotopic makeup for carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, and a database of isotopic ratios exists for many regions of the world where food is produced. Because the isotopic composition survives the winemaking process, any wine can be tested for its general area of origin. Authentication to varietal is also now possible via two techniques based on DNA. One involves the infusion of DNA from the vines themselves into the ink that is used to print the labels on wine bottles. Some Australian wineries are using this method to track and authenticate their products. The other approach involves directly isolating DNA from the wine; fermentation is one of many food-processing methods that do not destroy DNA in the final product. Once the DNA of the wine in a bottle is isolated and sequenced, the sequence can be compared to others in the grape stud-book to determine the vine strain used to make the wine. This approach has been utilized for years to identify caviar, some of which comes from endangered sturgeon species. With the right equipment, the DNA from processed caviar can easily be isolated and compared with a database of fish sequences to identify the species from which it came. In all such approaches, the DNA from the source of the wine or the foodstuff is used as a “barcode” to identify the species or variety of origin.

The authentication methods we have just described are new, and hold promise for the future. But the lesson of history is clear. At the top end, a lot more of many prestigious wines has probably been drunk than was ever produced; at the low end, the threat of adulteration of cheaper wines with cattle blood, battery acid, and other unpleasant additives is unlikely to go away, particularly if climate change increasingly threatens producers with poor growing conditions. Of course, those buying old and rare bottles have always been taking a risk, and many of the world’s leading restaurants warn their customers that if they order a rare wine beyond a certain age there will be no swirling, sniffing, and sipping followed by sending it back. That is probably as it should be, certainly as regards the condition of the wine. Someone has to bear the risk. And while guaranteeing the wine’s origin is a different matter, at this market level the caveat emptor rule seems fair. What is more, for those in search of the genuine grandes dames of wine, the Internet already overflows with more or less useful advice on how to detect a faked old bottle.

For everyday consumers, it will be business as usual. As long as there is a buck to be made by adulterating wines, someone will be doing it. If we want to be sure that we are drinking what we think we are, at present we are largely dependent either on our own knowledge and sensory evaluations or on official vigilance. Despite the promise of technology, in an age of deregulation it seems unlikely that the authorities will in future be more helpful than they have been in the past. For the most part, consumers will continue to be on their own—unless, of course, someone develops a wine-testing app: a discreet little probe, connected to a vast database via smartphone.