Manhattan Island, just 22.4 square miles in total, 23 miles long, and, at 14th Street, 2.3 miles wide, would emerge as the most populous place in the United States and the country’s preeminent city. Until consolidation took place in 1898, the island alone constituted the city of New York. Brooklyn, across the East River on Long Island, was a separate city, and the outer boroughs remained largely rural farmland.

At the time of the first US census in 1790, the Atlantic seaboard cities—Boston, Newport, Philadelphia, and Baltimore—vied to capture the new country’s maritime commerce. By 1850, New York City’s population had soared to over half a million, and it reigned as the leading metropolis in the country. The growth and prosperity of the port explains the dominance of the city in the nineteenth century.

Manhattan became a global city by building maritime links across the oceans, along the Atlantic coast, and inland to the Midwest and New England. The shorefront of Manhattan Island, the boundary between water and land, served for hundreds of years as the center for the trade, shipping, and commerce of the nation as the port became the busiest in the world. No other activity took precedence over commerce. The shore remained a place apart, a world of piers and docks; longshoremen; and ships, tugboats, and ferries filled with cargo and freight; as well as a site where millions of immigrants entered the Promised Land.

Nature provided New York with a sheltered harbor, but to flourish, the port required a complex maritime infrastructure of wharves, piers, warehouses, and waterfront streets to facilitate the transfer of goods and people between water and land. A busy port depended on a large workforce of itinerant day laborers who lived nearby and would be available on the docks, in all weather, as ships arrived and departed.

A prosperous seaport needed substantial investment in its waterfront infrastructure to provide ships and merchants with access at reasonable costs. New York faced a challenge here: to find the necessary capital to build and expand its maritime infrastructure. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the city’s government did not have the responsibility or the fiscal resources to develop needed port facilities. To build this infrastructure, the city gave away a precious asset: the land under the water around the lower part of Manhattan Island. The municipal government awarded these water-lots to private individuals to build wharves and piers, surrendering public control of the waterfront.

For over 250 years, private enterprise ran the waterfront; the city played merely a peripheral role. By the end of the Civil War, chaos threatened the port’s dominance. In 1870, the city and the state created the Department of Docks to exercise public control and rebuild the port’s maritime infrastructure for the new era of steamships and ocean liners. A hundred years later, technological change—in the form of container shipping and jet airplanes—rendered Manhattan’s waterfront obsolete within an incredibly short time span. The maritime use of the shoreline collapsed, mirroring the near death of the city of New York in the 1970s. Ships disappeared and abandoned piers and empty warehouses lined the waterfront.

The city slowly and painfully recovered. The vacated waterfront allowed visionaries and planners to completely reimagine a shore lined with parkland. Along the revitalized waterfront, luxury housing has transformed the neighborhoods where Irish longshoremen once lived. A few remaining piers offer spectacular views of the city’s waterways. The rebirth has been driven by complex private/public partnerships, with the city of New York playing only a peripheral role. The contentious question of private versus public control of the waterfront remains a continuing issue in the twenty-first century.

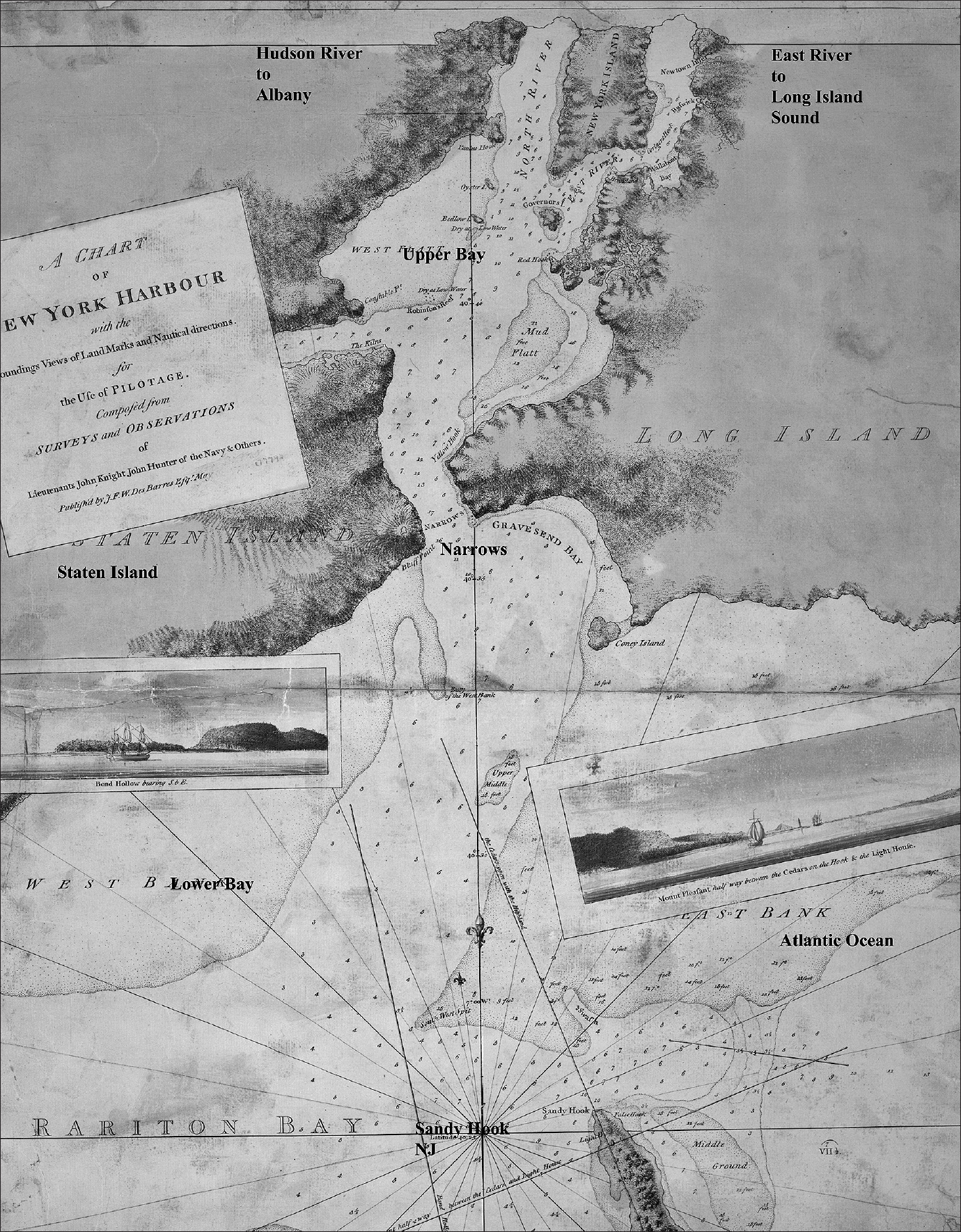

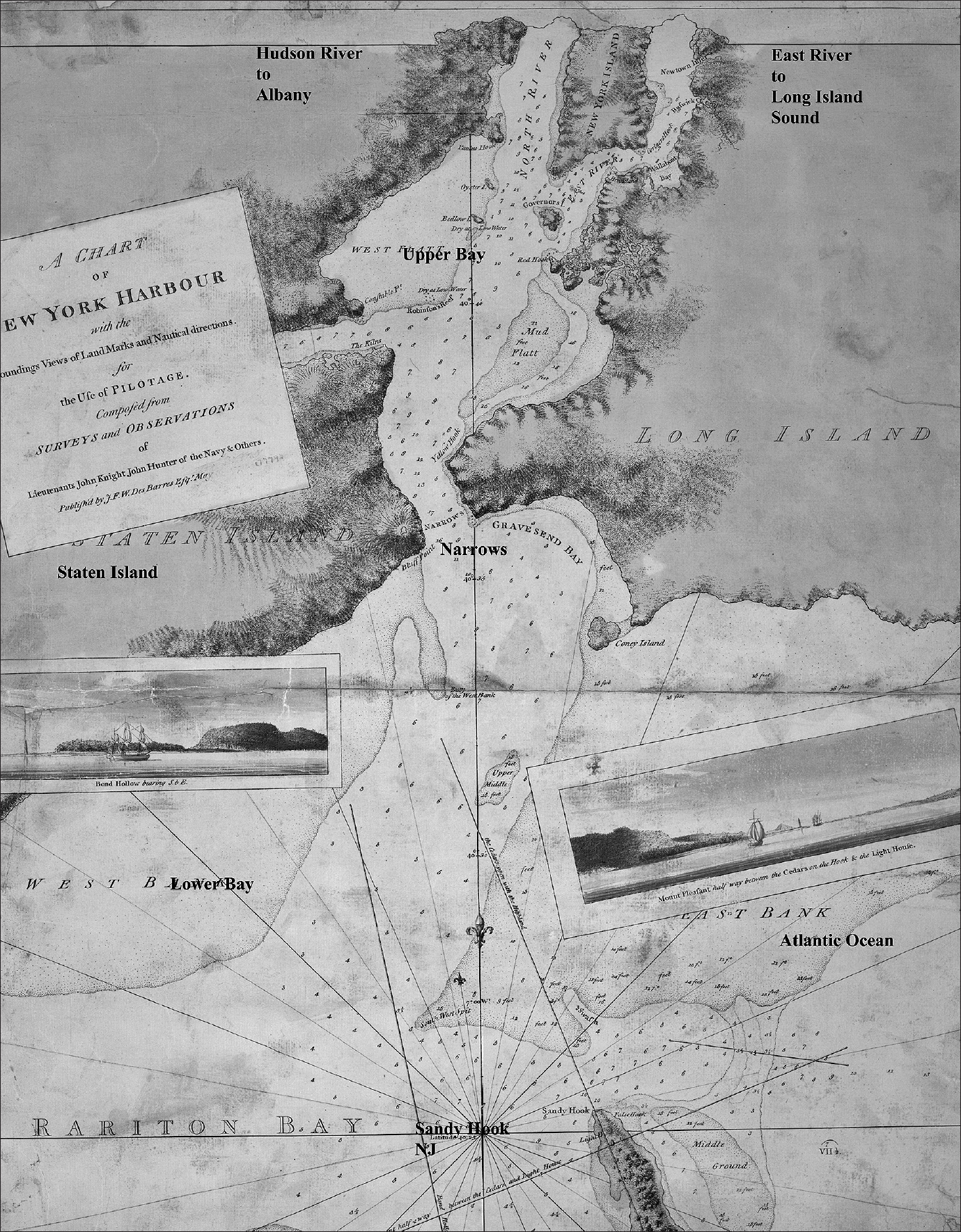

To the south of Manhattan Island lies New York Harbor, one of the greatest natural harbors in the world, providing deep but sheltered anchorage from all but the most violent ocean storms (map 1.1). Both Staten Island and the Brooklyn section of Long Island form a natural barrier between the harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. The waters of the Upper Bay offer space for hundreds of ships to anchor. Between Staten Island and Brooklyn, the Narrows forms a deepwater entrance. From the Upper Bay, the Hudson River leads north to Albany and to waterways across the state that reach the Great Lakes and the Midwest. The East River, a tidal estuary, connects to Long Island Sound and provides a protected passage to New England.

Map 1.1. New York Harbor, in 1779, showing the Narrows, the Upper Bay, and lower Manhattan Island. Source: “A Chart of New York Harbor, with the Soundings . . . ,” 1779, Map Division, New York Public Library

Land sloping gently down to the sea, deep water extending almost to the shoreline, and a minimal rise and fall of the tide offered an ideal location for maritime trade. Both the Hudson and East Rivers are tidal estuaries, and twice a day the tide floods (up the harbor and the rivers) and ebbs (down the harbor to the ocean). Sailing ships took advantage of the tidal currents to assist them in entering or departing from the harbor.

When the first Dutch ships arrived in New Amsterdam in 1624, they anchored in the East River, people and cargo were rowed ashore in small dories. The reverse took place as a ship readied for departure. Once the volume of shipping increased, the use of dories proved to be time consuming and expensive. A more efficient system involved building wood or stone structures: wharves (paralleling the shorefront), or piers (extending from the shoreline out into the water). Both simplified the unloading and loading of ships moored to the wharves or piers. On the shore adjacent to these structures, waterfront streets facilitated the transportation of goods and people inland.

The English captured New Amsterdam from the Dutch in 1664 and renamed the city New York. Two charters established the city of New York as a corporation—with its own government, consisting of a Common Council and a mayor—distinct from the colony of New York. The 1686 Dongan Charter and, later, the Montgomerie Charter of 1730 legally defined the waters around Manhattan Island to be the property of the city. The Montgomerie Charter specified that the city owned all of underwater land extending out from the island for 400 feet beyond the low-water line. It created a resource of immense value—water-lots adjacent to the shorefront—and gave the Corporation of the City of New York the legal right to grant the water-lots to private citizens.

The city used the water-lots to attract private waterfront investment. First the English governors, and later the city’s Common Council, granted water-lots to individuals, often the politically connected well-to-do who owned shoreline property. In return for a water-lot grant, the private owners had a legal obligation to build a bulkhead out from the existing shoreline into the river, which would serve as a wharf, as well as to construct a new city waterfront street for public use. They could also build a pier out into the surrounding rivers. Such requirements under the grants, however, did not include specific construction details. Fees paid to use the wharves and piers went to these private owners, not the city. In addition, the grantees filled in their water-lots, creating made-land along the shore that they could then develop. On this new made-land, the owners constructed warehouses, counting-houses, tenements, and factories. The use of water-lot grants and private investment ceded control of the waterfront from the city to private interests. The city could revoke the grants, but seldom did, and it exercised only weak regulatory power over the city’s most valuable asset: direct access to the greatest natural harbor in the world.

Thus the shoreline of the city moved out into the Hudson and East Rivers. Map 1.2 illustrates the water-lots and made-land in Lower Manhattan: along the Hudson River from Greenwich Street, the original shoreline, to the new wharves on West Street. This waterfront real estate, created on made-land, belonged to the grantees, not to the city of New York, and today it is among some of the most valuable real estate in the world. For 300 years, the granting of water-lots enlarged the island of Manhattan by 3.57 square miles, adding 2,286 acres (map 1.3).1

As the port grew, the city continued to use water-lot grants to facilitate the building of additional infrastructure along the East and Hudson Rivers, but the wharves alone could never meet the demand as the volume of shipping increased. By the Civil War period, captains, shipowners, and city merchants complained vociferously about the lack of pier space, the rotting wharves, poor maintenance, overcrowded waterfront streets, inadequate storage, corruption, and the gangs of thieves who pillaged the waterfront. Thunderous newspaper editorials warned that without dramatic improvements, New York City would lose maritime business to Boston, Baltimore, or Philadelphia. Private ownership had failed to build, maintain, and upgrade the essential infrastructure and threatened the port’s maritime supremacy.

In 1870, the city and the state of New York passed legislation to establish a public agency, the Department of Docks, to reassert public control over the waterfront. At great expense, the city purchased the wharves and piers from the private owners and set out to rebuild the waterfront, operating the port for the public good, not for private gain. The Department of Docks managed to accommodate vast changes in the harbor as the size of both cargo and passenger ships increased dramatically. The tables turned again at the beginning of the twentieth century, when shipping companies, business leaders, and even the corrupt longshoremen’s union warned of the coming demise of the harbor because of its mismanagement by the department. A whirlwind of change did arrive, but maladministration by New York City’s Department of Docks played only a tangential role.

Map 1.2. Water-lots on the Hudson River, from the Battery to Rector Street. The numbers on the map indicate the original Manhattan shoreline, with high water at Greenwich Street (1); the first water-lot grants, in the 1760s, from Greenwich Street to Washington Street (2); the second water-lot grants, in the 1830s, from Washington Street to West Street (3); West Street, a new waterfront street (4); and wharves and piers along the Hudson River (5). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: water lots, 1870 Department of Docks map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

Map 1.3. A 1776 map of Lower Manhattan, with a black line showing the modern shoreline. The numbers on the map indicate Stuyvesant Cove/Stuyvesant Town (1); Corlears Hook, on the Lower East Side (2); Battery Park (3); Battery Park City (4); the Freedom Tower / World Trade Center (5); Pier 40, on Canal Street (6); and Chelsea (7). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layers: 1776 Ratzer map, New York Public Library, Map Warper; shoreline map, New York City Planning Department.

Taking advantage of nature’s gifts, the Port of New York came to dominate three commercial waterway territories: the first, routes across the North Atlantic Ocean to and from Europe; the second, a coastal shipping empire to the American South and the Caribbean; and the third, inland transportation up the Hudson River to upstate New York, the Great Lakes, and Chicago, as well as up the East River, through Long Island Sound, to Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New England. The city’s most important international links stretched across the North Atlantic from New York to Liverpool in England and Le Havre in France. In the early nineteenth century, with relentless determination, the city’s shipowners captured the North Atlantic waterway. New York Harbor served as the center of the country’s export and import trade. All of New York’s maritime rivals fell far behind.

On October 27, 1817, a woodcut ad appeared in a New York newspaper, announcing that as of the first week in January 1818, a new packet line of ships would begin monthly sailings from New York and, simultaneously, from Liverpool. The Black Ball Line, founded by five of New York’s leading Quaker shipowners and merchants, guaranteed service from an East River pier regardless of the weather, including if there was a full cargo or not. Not only did the owners of the Black Ball Line, at great financial risk, begin a transportation revolution, but the packets also created a new communications link across the North Atlantic. In addition to cargo and first-class passengers, the packet ships carried commercial mail. An international trading system required the fastest communication possible between New York and Europe. Letters of credit, private banking correspondence, bills of sale, and specie had to be sent back and forth, and the packet lines provided fast, scheduled service.

Rival packet lines to Liverpool followed: the Red Star Line and the Blue Swallowtail Line in 1822 and, later, the Dramatic Line (1835) and the New Line (1839). Packet ships left New York and Liverpool every week of the month, every month of the year. No other port in the United States offered anywhere near this level of service. The Port of New York had packet lines not only to Liverpool, but also two lines to London and three to Le Havre, strengthening the city’s hold on the ocean pathway to Europe (see table 4.1).

New York’s link to Liverpool allowed the city to control the cotton textile trade between the slave plantations in the American South and the textile mills in Lincolnshire in northwestern England, to which Liverpool provided access. The industrial revolution in England created an insatiable demand for the high-quality cotton grown in the South. For more than a century, cotton remained the most valuable product produced by the American economy, creating a direct link between slaves on the southern plantations and the nascent industrial workforce laboring in the satanic conditions of the textile mills in England. New York Harbor and its shipping industry played a pivotal role. Each year, tens of thousands of cotton bales carried north on coastal ships arrived on the piers along the East and Hudson Rivers. Once unloaded, the bales were carted along the waterfront to waiting packet ships bound for Liverpool. Textiles returned from Liverpool to be distributed throughout the country, including down the Atlantic coast to the South. Even cotton transported directly from the southern cotton ports to Liverpool arrived on ships owned or financed by New York’s shipping businesses.

The city’s merchant bankers developed a sophisticated system of international credit that enabled plantation owners in the South to purchase slaves and grow cotton and then consign the cotton to traders, who shipped it to England. In Liverpool, import merchants bought the cotton and then quickly sold it to the textile mills. Lastly, the swift packet ships returned from England carrying English gold and silver back to New York, for the bankers to use both to settle accounts, including the funds advanced each year to the plantation owners in the South, and, of course, to take their own substantial profits. Capital accumulated in the cotton trade enabled the New York bankers to finance the shipping industry, the city’s maritime infrastructure, and the burgeoning industrial revolution in the city and the United States.

A second crucial waterway linked New York with coastal ports in the South—Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans—that handled the eighteenth century’s key agricultural product: cotton. By 1832, New York’s shipowners established packet lines to all of the major southern ports. With scheduled service, these southern packets offered fast shipment of cotton to Liverpool, with the first leg running up the coast to the Manhattan waterfront, and the second leg traveling across the North Atlantic to England.

New Yorkers owned many of the cotton ships that sailed directly from the southern ports to Liverpool. The city’s merchants and bankers also provided crucial ancillary services: insurance, credit, export and import services with their Liverpool counterparts, and the settlement of international payments. The pivotal role played by New York—always at a substantial profit—infuriated the plantation owners and the southern cotton aristocracy. The maritime historian Robert Albion referred to the city’s dominance as “enslaving the cotton ports.”2

A third waterway empire ran to the north: up the Hudson River to Albany and then west by the Mohawk River to central New York. From northern Alabama to Maine’s border with Canada, the Appalachian Mountains separate the Atlantic seaboard from the Midwest and, in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, posed a serious challenge to travel. In upstate New York, a gap exists in the Appalachian Mountains along the Mohawk River and then across rolling countryside to Lake Erie, at Buffalo. What become known as the water-level route served as the ideal location for the Erie Canal and, later, the route of the New York Central Railroad across New York State and further west.

The Erie Canal had an enormous impact on the history of the Port of New York, linking Manhattan to Chicago, the great city of the Midwest, characterized by historian William Cronin as “nature’s metropolis.”3 New York captured the bounty of the Midwest. In return, imports from Europe bound for Chicago and the central states came through the Manhattan waterfront, transferred from ocean-going packet ships to Erie Canal barges.

Another key part of the inland waterway empire, the East River, connects New York’s harbor to Long Island Sound. For over 90 miles, the Sound provides a protected water route to Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. From the Race, which marks the eastern end of Long Island Sound, the ocean passage to Narragansett Bay is less than 30 miles. On the north side of the Sound, the Connecticut River is navigable to a point north of Hartford, and then from the Massachusetts border to the middle of Vermont. Steamboats connected the Port of New York with cities along the Connecticut coast, Narragansett Bay, and Massachusetts, extending the commercial reach of New York City.

Local needs compounded the crush along New York City’s shoreline. The rivers, bays, and Long Island Sound connected the growing city with a hinterland that supplied basic needs: food, wood for cooking and heating, and building materials. All goods had to be transported by water to the Manhattan waterfront. In addition, a fleet of ferries carried thousands of passengers across the waters each day to Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, and New Jersey. These ferries, along with small sailing vessels, steamboats, and canal barges, competed for the limited space on the piers surrounding Lower Manhattan, adding to the congestion of people and goods on the waterfront.

For the Port of New York to grow and prosper, it needed more than nature’s gifts; the port’s infrastructure; and aggressive shipowners, merchants, and bankers. The thousands of ships in the harbor each year and the millions of tons of cargo that had to be moved across the waterfront required a large labor force. These men worked as day laborers, not as long-term employees, and they could never be sure of steady work. From the time of the Dutch, as each ship arrived or departed—from the largest ocean-going sailing ships to the small single-masted sloops or humble canal barges—the cry “along shore men” rang out, and hundreds hurried to the wharves and piers to secure a day’s work on the docks. Loading, unloading, and moving cargo remained a labor-intensive process for centuries.

The longshoremen worked long hours, in all types of weather. A brutal system of day labor became enshrined by the shape-up, where hundreds of men stood at the pier entrance, hoping to be hired for the day. Pier bosses demanded kickbacks, loan sharks worked the docks, and prostitution and crime flourished nearby. A code of silence prevailed. Any longshoreman brave enough to speak out was often found dead, floating next to the pier with his throat slit. In the early twentieth century, corruption prevailed in the longshoremen’s union, which failed to protect its members. Organized crime eventually controlled the docks and shook down the shipping companies, which paid bribes in exchange for labor peace. Cargo theft reached epidemic levels. Waterfront corruption extended to the highest level of politics in New York City and the state.

Longshoremen and other dockworkers lived a few blocks away, in the immigrant neighborhoods along the East and Hudson Rivers. Generations of immigrants, many from Ireland, worked the docks and endured lives of hardship and toil. A tribal way of life arose, where sons followed fathers down to the docks each day. On the nearby streets, the Irish waterfront laborers, their wives, and their children lived in crowded tenements. While their life was hard, many found refuge and spiritual support in the Catholic churches that served the waterfront.

After World War II, crusading journalist Malcolm Johnson and a Jesuit priest, Fr. John (Pete) Corridan, led the fight for reform on the waterfront. They battled the corrupt longshoremen’s union, the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA), to rid the piers of mobsters who controlled the daily work on the docks. Johnson wrote articles in the New York Sun detailing the crime and corruption there, a series for which he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1949. His main source was Fr. Corridan, a priest who dedicated his ministry to helping the Irish on the Manhattan waterfront. Corridan eventually ran afoul of the Archdiocese of New York, which received generous support from Catholic executives in the shipping companies and the senior leadership of the ILA.

Corridan provided Johnson and Budd Schulberg, a Hollywood screenwriter, with the material the latter used to write the script for the 1954 Academy Award–winning movie On the Waterfront, which starred Marlon Brando and was directed by Elia Kazan. This movie portrayed the dark world of the waterfront and generated enormous publicity, leading to calls for reform. Yet as long as ships continued to fill the harbor, business, political, and religious leaders turned a blind eye.

Organized crime endures on the waterfront, not on the piers in Manhattan or Brooklyn, but in the giant container port in Newark, New Jersey. Sixty-plus years after the movie was first released, a nephew of a mobster earned $400,000 a year at Port Newark; he never was off the clock, even when at home in bed. Three successive Newark longshoremen’s union presidents were convicted of extortion, and investigators dug up $51,900 in a longshoreman’s backyard—a payoff destined for the mob.4

Dramatic change did come to the New York waterfront, but not through a reform of the longshoremen’s union or the expulsion of gangsters from the docks. Instead, a technological revolution—in the form of a simple metal box 20 feet long, 8 feet wide, and 10 feet tall—rendered Manhattan’s complex waterfront infrastructure and its system of day labor obsolete in a short period of time. The container revolution began in April 1956, when Malcom McLean, a trucking and shipping executive, loaded twenty-four containers aboard his ship, the Ideal-X, in Port Newark, across the Upper Bay from the Manhattan waterfront, and set sail for Houston, Texas.

In the space of twenty years, such containers completely transformed the maritime world that had dominated the economy of Manhattan Island and the waterfront for hundreds of years. This type of shipping needed port facilities with both vast spaces around the piers to store the containers and easy access to the country’s new interstate highway system, neither of which existed on the crowded Manhattan waterfront. In a heartbeat, the maritime world that had occupied this area for over 350 years relocated across the Hudson River to Newark Bay in New Jersey.

On the piers, silence fell. Only a few ships arrived along the Hudson River or Brooklyn waterfront from across the Atlantic Ocean, the Midwest, New England, the American South, or anywhere else. New York’s waterway empire vanished. The Department of Marine and Aviation, the successor to the Department of Docks, could not find shipping companies willing to lease piers at any cost. Longshoremen and their union struggled to preserve waterfront jobs, but nothing could hold back the wave of technological change. A way of life for the longshoremen disappeared, and their tight-knit waterfront neighborhoods changed dramatically. Along the Hudson and East Rivers, pier after pier stood abandoned and, in some cases, fell into the river. The luxury ocean-liner business faded away, as people could now travel by air to Europe or anywhere in the world. Neither public nor private enterprise, and no amount of public or private investment, could save the maritime world along Manhattan’s waterfront.

In the 1960s, the Manhattan waterfront and the entire city of New York entered an extended period of decline and despair. The elevated West Side Highway, adjacent to the Hudson River piers, collapsed from a lack of funds for proper maintenance, a fitting symbol of decline. In the late 1970s, the city of New York careened toward bankruptcy. Crime, drugs, and abandonment prevailed on the waterfront and in the surrounding neighborhoods.

Slowly, and with great effort, the city recovered from decades of decline, and this rebirth included reimagining the use of Manhattan’s waterfront. Its commercial use would never return but the shoreline could become parkland and recreation space, a place to be reminded daily that Manhattan is an island surrounded by waterways. Now the waterfront’s most valuable asset proved to be the views from ashore, not the water-lots below the rivers.

A massive plan to rebuild the West Side Highway led to a bitter fight over the future of the waterfront on the West Side. The Westway conflict stimulated alternative plans that imagined the shoreline as a public asset. This reinvigorated shoreline would become a place for New Yorkers and tourists alike to enjoy magnificent water views and watch the sun set over the Hudson River and Upper Bay. For the wealthy, the waterfront would become a desirable place to live, and for the fashionable, a trendy locale in which to dine or visit a gallery. Despite the defeat of the Westway proposal, the shorefront still remains a contested space. Will people from all walks of life and levels of income be welcome on the revitalized private/public waterfront, or will it become a place set apart, for only the wealthy to enjoy?

The rebirth of the Manhattan waterfront has justly received universal praise. Yet in an era of climate change, three centuries of creating made-land around the island has left the city facing another daunting challenge. The filling in of Stuyvesant Cove between 14th and 26th Streets on the East River created the land where Stuyvesant Town, a huge housing complex, sits just a few feet above high water. Battery Park City and the Freedom Tower, which replaced the World Trade Center, have similar elevations above the Hudson River. Lower Manhattan’s shoreline today sits offshore, some distance from the 1776 waterfront. Extensive valuable real estate stands on this made-land.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy devastated the Manhattan waterfront and the shoreline communities throughout the city, Long Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut. The extraordinary high tide, driven by the onshore winds, caused enormous damage and flooded Battery Park City and Lower Manhattan, including the subways and the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. At 14th Street, a Con Edison power plant exploded, plunging Lower Manhattan into darkness. Climate scientists predict that with rising sea levels, an ordinary hurricane or even a storm with high winds will pose the same danger as Superstorm Sandy did, putting the revitalized shoreline and the city at grave risk. Despite the success of Manhattan’s waterfront rebirth, the threat posed by global warming will remain a major challenge for New York City in the twenty-first century.