The city of New York and its harbor remained, first and foremost, a place of commerce and trade. At first the waterfront developed to serve a small trading enterprise and, later, the maritime commerce of an emerging United States. All other activities—homes for the wealthy, a place to contemplate the natural beauty of the harbor and its surrounding rivers, and space for recreation—would be relegated to the interior of the island. Nothing could be allowed to interfere with New York’s profit-making enterprise, the source of wealth for the city and the country. In 1857, a report to the New York State Senate on “encroachment” in the harbor laid out the importance of using the waterfront for trade: “Maritime nations in every age have sedulously cherished their foreign commerce. Regarding it as an essential means of their prosperity, they have been careful to provide spacious and commodious harbors for its reception . . . [and] expended large sums in improving the natural advantages of their respective ports.”1

Ninety years later, the Merchant’s Association, the Real Estate Owners Association, and the Board of Trade and Transportation all opposed the expansion of Riverside Park, north of 72nd Street, to the edge of the Hudson River. They argued that the continued increase in commerce in the Port of New York would eventually require building new piers as far up the Hudson as 72nd Street and beyond. Maritime use, they argued, took precedence over increased park space.2

Despite the advantages of its superb harbor, the city of New York did not always dominate the trade of the colonies. During the American Revolution, including the British occupation of the city, its maritime commerce collapsed. The British controlled all shipping in the harbor and allowed only loyalists to trade. Estimates are that during this occupation, the city lost half of its population.

Just days after the British troops landed on Manhattan Island, a major fire broke out on the night of September 21, 1776, which destroyed 25 percent of all buildings in the city. The British accused the “rebels” of arson and placed the city under harsh martial law, which continued throughout the occupation. Neither Baltimore nor Boston nor Philadelphia suffered as much as New York. Many feared that the city would never recover and that one of its competitors would emerge as the new country’s major seaport.

Despite that pessimism, New York did rebound, led by a bold group of merchants and shipowners. Exports rose from less than $400,000 in 1783 to almost $3 million by 1793. The voyage of the Empress of China in 1784 symbolized the rebirth of the city’s maritime commerce. On a cold morning on February 22, the Empress departed from an East River pier and set sail for China by way of Cape Horn. Arriving in northern California, the sailors slaughtered seals for their fur, which was of great value in Asia, and then crossed the Pacific Ocean. Fourteen months later, on May 11, 1785, the ship arrived back in New York, setting off a large celebration. The voyage of the Empress created a trading link between New York and the Orient. The voyage was estimated to have netted profits in excess of 100 percent for the merchants who risked financing it, including Robert Morris of Revolutionary War fame. Despite the risks, New York merchants sent other ships to follow the Empress to China.3

After the Revolution, trade with Britain also resumed, despite the lingering bitterness on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Above all else, one overriding economic factor linked the new United States to Britain: cotton. By 1800, the Industrial Revolution, which would change the history of both countries and the entire world, was underway in England. A remarkable group of British craftsmen and entrepreneurs transformed the iron industry, built the world’s first steam engines, and developed the machinery to mechanize the production of thread and cloth. Soon the river valleys of northwestern England would see the rise of the first textile mills, creating an insatiable demand for raw cotton. With the profits from the cotton textile industry, England rose to become the world’s superpower.4

While trade across the Atlantic Ocean from New York to Britain expanded, political tensions remained. England soon found itself at war with France, a war that lasted for over a decade. England declared a total embargo on French imports and exports and used its navy to force other countries to cease their trade with France. British and French privateers began to raid Atlantic shipping vessels, including American ships. The British Royal Navy, by far the largest in the world, needed an endless supply of sailors. Among other practices, it began the impressment, or forced recruitment, of seamen from American ships, who were accused of being deserters.

President Thomas Jefferson’s ill-advised Embargo Act of 1808 prohibited any exports to foreign countries, which had a devastating impact on New York and all other major ports until the act was repealed a year later. Despite this repeal and the recovery of trade across the Atlantic Ocean, tensions between the United States and Britain continued and eventually led to another war in 1812. New York and its merchants suffered as privateers preyed upon American shipping based in the port. When that war ended in 1815, New Yorkers faced the daunting task of rebuilding the city’s maritime economy.

New York Harbor’s rise to a position of maritime supremacy began on the transatlantic waterway to Europe. To the east, across 3,000 miles of the North Atlantic, were the major European ports: London and Liverpool in England, and Le Havre on the Normandy coast of France. Albion describes the New York–Liverpool crossing as “the most important of all the world’s sea lanes . . . with branches leading to other British or continental ports.”5 This all-important route across the Atlantic Ocean constituted a crucial maritime highway, linking the cotton kingdom in the New World to the Industrial Revolution in the Old World. To secure this waterway, New York shipowners revolutionized the shipping industry, creating something completely new: service on fixed dates, or what Albion calls “square-riggers on schedule.”6

In ports throughout the world in the early eighteenth century, sailing vessels of all sizes arrived and departed without any specified schedules. Along the East River, ships leaving for Europe, traveling down the coast to the American South, or heading for New England by way of Long Island Sound waited until they were filled by cargo and passengers. Captains and shipping merchants frequented the Tontine Coffee House, on the corner of Wall and Water Streets, to study both the lists of incoming merchandise for sale and the notices of ships seeking goods and passengers for departure. Some boats advertised a date of departure, but most seldom departed on the advertised date, since the owners saw no reason for their vessels to sail without a full hold and simply postponed the departure. In the meantime, merchants had to wait to load cargo, and passengers had to find a boarding house for temporary accommodations, which cost more money. Transient ships serving New York picked up cargo wherever it could be found and moved from port to port with no set schedule. Merchants could not depend on the transients to deliver cargo to a particular port on any specific date. For example, in 1828, the Midas sailed from Salem, Massachusetts, to Portland, Maine, and then on to St. Thomas, Puerto Rico, Mobile, Le Havre in France, and finally to New York.7 Other ships sailed back and forth on a fixed route, such as New York to Boston or Havana or Mobile or London, but again with no predetermined schedule.

The Gazette and Commercial Advertiser, the principal shipping newspaper published in New York in the 1800s, carried advertisements for boats leaving from the waterfront. On Friday, November 15, 1816, the Gazette advertised five vessels sailing for Liverpool, including the Nestor, “a superior and well known ship . . . built in the city of live oak and locust and coppered last year in Liverpool. Having now the principal part of her freight engaged and going on board, she is intended to sail by 25th inst. without fail.”8 The Nestor may have sailed by November 25, or perhaps not until December 25. On the same page, two ships advertised service to Dublin, and four to New Orleans. Hundreds of vessels came and left from New York in 1816, but none sailed on a fixed schedule. The same pattern prevailed in Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

On October 27, 1817, an ad appeared in the Gazette, with a woodcut across the top depicting four ships and announcing a “LINE OF AMERICAN PACKETS BETWEEN N. YORK AND LIVERPOOL.” A new era began that year, initiating a revolution in ocean transportation on the most important sailing route in the world. Five of New York’s prominent shipping merchants—Jeremiah Thompson, Isaac Wright, his son William Wright, Francis Thompson, and Benjamin Marshall—announced that their four ships, the Amity, Courier, Pacific, and James Monroe, would begin regularly scheduled service to and from Liverpool each month, departing on a specific day and time. The ad explained that “one of these vessels shall sail from New York on the 5th, and from Liverpool on the 1st of each month,” providing scheduled service to Liverpool every month of the year, leaving from Pier 16 on the East River, at the foot of Wall Street. The ships became known as packet ships, because of the packets of mail they carried across the Atlantic Ocean, which was a lucrative source of income (fig. 3.1).9

Figure 3.1. The Black Ball Line packet ship Isaac Webb leaving New York Harbor, bound for Liverpool, England. Source: Granger Archives

Jeremiah Thompson, a Quaker born in Yorkshire, England, in 1784, arrived in New York in 1801, at the age of 18. Thompson and his partners risked their considerable wealth on their new enterprise, the Black Ball Line, providing the bold leadership that drove the Port of New York to dominance in the Atlantic trade. They maintained a close business relationship with the Liverpool import firm of Crooper, Benson & Company, whose principal owner, James Crooper, also a Quaker, became a leader of the English antislavery movement. Jeremiah Thompson became one of New York’s wealthiest merchants and remained very active in the New York Manumission Society. Despite their personal beliefs, both Thompson and Crooper nevertheless built a transatlantic partnership inexorably tied to the cotton raised in the American South by millions of slaves.10

The Black Ball Line packets sailed in the spring, fall, and summer, as well as throughout the winter months, when the weather in the North Atlantic Ocean was at its worst. Promptly at 10:00 a.m. on January 5, 1818, with snow falling, the James Monroe cast off from Pier 16, trimmed its sails, and proceeded down the Upper Bay, through the Narrows, passed Sandy Hook, and set an easterly course for Liverpool, 3,000 miles away. On New Year’s Day, the Courier left Liverpool bound for New York.

The James Monroe landed in England on January 28, after twenty-three days of sailing west to east from New York. The Courier faced a much more daunting challenge, crossing the North Atlantic in winter from east to west. Battling against the prevailing winds, she did not reach New York until February, a passage of forty-seven days. By the time the Courier arrived in New York, the Amity had already departed from New York to Liverpool for February’s scheduled sailing. Given the prevailing westerly wind in the North Atlantic, the Black Ball Line ships averaged much faster passages from New York to Liverpool (twenty-four days, or more than three weeks) than the reverse (thirty-eight days, or more than five weeks). The longest averages for crossings by Black Ball ships occurred during the winter months, from December through March.11

With the wind pushing a sailing ship from behind, mariners referred to the voyage as sailing “downhill.” Ships like the three-masted Black Ballers, with square-rigged sails, faced a much more difficult challenge sailing upwind, with the wind coming from the west, when sailing to New York. The vessels had to tack back and forth, a difficult maneuver for a big sailing ship, especially with the wind blowing hard. To tack, the bow has to be turned across the wind and the sails shifted from one side of the ship to the other, which required great skill and timing with all hands on deck as almost the entire crew manned the maze of lines that controlled the sails. The captain, standing near the sailors who were on the wheel that steered the ship, waited for precisely the right moment to order the tack, while other sailors hauled on their assigned lines. Tacking with a big sea that was running 20- to 30-foot waves, in the middle of a freezing January night in the North Atlantic Ocean, tested the courage and fortitude of the captain and crew.

The Black Ball Line proved to be an immediate success, with their packets capturing the market for shipping high-value freight and wealthy passengers across the transatlantic waterway to Liverpool. The most important cargo carried by the first Black Ball packets consisted of cotton bales bound for England’s expanding cotton textile industry. On their return voyages, the ships brought British textiles and manufactured goods to New York, providing very substantial earnings for the owners.

The Liverpool Customs’ bills of entry list the arrival of ships in Liverpool and the cargo they carried. The Black Ball Line’s William Thompson entered Prince’s Dock on July 16, 1825, its hold filled with 887 bales of cotton and 50 barrels of iron ore, with the value of the cotton far exceeding that of the iron ore.12 The voyage of the William Thompson illustrates the “cotton web,” which Gene Dattel describes as the first “truly integrated national and international operation, perhaps the first global business. Cotton connected the South with the North, the West, and Europe. Finance, politics, business structure, transportation, distribution, and international relations were all parts of the cotton web. A sophisticated business apparatus developed to service cotton production and the cotton textile industry.”13

The web linked the cotton plantations in the South to the docks along the East River, the counting-houses in New York City, the Black Ball ships crossing the North Atlantic to Liverpool’s Prince’s Dock, and the Crooper, Benson & Company import firm. From Liverpool, the web led to the satanic-like mills in Manchester and Birmingham. The voyage back across the Atlantic Ocean brought a flood of textiles, manufactured goods, and British silver and gold. New York shipowners and merchant bankers took their profits, and the remaining specie went farther south, to finance the plantations and slavery. Cotton played the key role in the growth of American maritime commerce, the Port of New York, and the First Industrial Revolution in England. Dattel points out that Karl Marx recognized that “without cotton you have no modern industry.” Marx also added, “Without slavery you have no cotton.”14 In the nineteenth century, cotton was the foundation for the wealth, power, and prosperity of both England and the United States.

The Black Ball Line enjoyed a monopoly on fast, scheduled service to Liverpool for five years. Competition came in 1822, with the announcement of the Red Star Line to Liverpool, with four ships. The Meteor departed New York on schedule on January 25, a red star painted on its foresail. The Black Ball Line responded immediately and announced the addition of four more ships, as well as departures twice a month instead of just once. With the addition of the Red Star Line, a total of twelve packet ships now provided scheduled service linking New York and Liverpool. In June 1822, another group of bold merchants started the Blue Swallowtail line of packets, and on August 8 the Robert Fulton left from the East River, bound for Liverpool. With three lines, packets now left New York on the first, eighth, sixteenth, and twenty-fourth of each month, with corresponding departures from Liverpool. Shippers and passengers could depend on direct, scheduled service from the Port of New York across the Atlantic every week of the month and every month of the year, no matter what the weather.

The New York packet lines also captured the mail business of the Atlantic World and, as international trade grew, their ships provided the most rapid and efficient communication between the United States, England, and continental Europe. New York newspapers became preeminent in the country, based on their access to the most up-to-date news from Britain and western Europe, carried on the packet ships.

No other American port offered comparable service. Packet lines were started in Boston and Baltimore, but with fewer ships and often-missed scheduled departure dates, they could not compete with the Port of New York. In just five years, New York cemented its lead as the premier port in the United States on the most important waterway in the world: across the Atlantic Ocean to Liverpool, the route Albion calls the “Atlantic shuttle.”15 Commerce across the Atlantic Ocean did not just involve Liverpool, however. London became the busiest port in both Britain and the world at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Two packet lines, the Black X Line and Red Swallowtail Line, began service to London in 1824. For thirty years, these two lines sailed between New York and London.

In France, the textile industry, centered in the Normandy region, made Le Havre the country’s most important port on the English Channel. Le Havre also traded in French luxury clothing and goods, which became the rage for all fashionable New York women. In 1822, Francis Depau and Isaac Bell announced a packet line to Le Havre, with four ships sailing every other month. The Old Line to Le Havre continued service between New York and France until 1851. Another packet line, the Second Line, began service to Le Havre in 1823. New York became the only port in the country where merchants and passengers could find reliable, scheduled service to England and France, which solidified New York’s lead over all other American ports in the Atlantic World.16

The success of these packet lines drew the international trade of the United States to the Port of New York. A New York State legislative committee compared the tonnage of imports to New York with those of London in 1830 and 1854. In 1830, the port of London handled 871,204 tons of foreign imports, and New York, just 353,769 tons, 40.6 percent of London’s total. By 1854, New York handled 1,919,313 tons of foreign freight, 71.9 percent of London’s volume (2,667,823). In just thirty years, New York had become the second-busiest port in the world.17

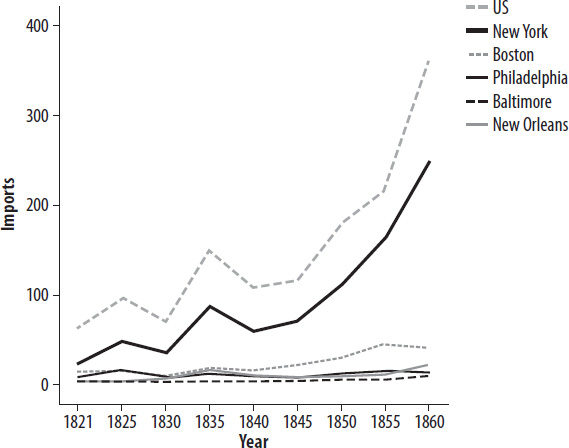

Chart 3.1. US imports at major ports, 1821–1860. The amounts for the imports are in millions of dollars. Source: Adapted from Robert Albion, The Rise of New York Port, 1815–1860 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1939), appendix 3, 391

As to overall US trade, between 1830 and 1855, the value of imports and exports grew dramatically. Exports increased from $73.8 million to $275.2 million, or 273 percent (chart 3.1). The value of a single commodity, cotton from the American South, dwarfed all other exports. Imports grew in parallel. With the packet lines well established by 1830, over 50 percent of the country’s imports were unloaded onto Manhattan’s piers.18

If the two primary cotton ports, Charleston and New Orleans, are removed, New York’s share of the country’s foreign trade, especially compared with its northern rival ports, increased dramatically. Over 50 percent of the exports from and two-thirds of the imports to the United States passed across the docks of New York. New York dominated the international maritime commerce of the entire country, while Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia fell far behind. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 created an inland waterway empire that reached as far west as Chicago and further cemented the Port of New York’s ascendency.

The early colonial maps of the New York waterfront identify a number of shipyards along the East River between Wall Street and Corlears Hook. By the early 1800s and the beginning of the packet lines, the demand for larger ships led to the need for expanded shipyards. The waterfront north of Corlears Hook and south of 14th Street became the center of the port’s shipbuilding. Just north of where the Williamsburg Bridge now stands, Jacob Westervelt began building packet ships in the 1820s and, over the next three decades, built fifty-five of them, more than any other shipbuilder. The Brown & Bell yard at Houston Street completed two packet ships in 1821, the William Tell and the Orbit, and, over the next two decades, ten more packets for the Black Ball Line were built in that yard.19 The third major shipyard was that of William Webb, whose son continued building into the clipper and steamship eras.20 These shipyards were an integral part of the port’s maritime world and became internationally famous for the design and construction of the packet ships that battled the westerly gales in the North Atlantic in winter.

Often a packet ship arrived in New York from Europe bruised and battered. To make the next scheduled sailing, the owners had no choice but to have the ship towed up the East River to one of the shipyards for repair. The skilled shipwrights at the Brown & Bell or the Westervelt yards labored night and day to refit the ship, often at great expense, in time for the next scheduled departure. High shipyard bills became a routine cost for the New York packet lines.21

The fame of the packet ships depended not only on sailing according to schedule, but also on having the shortest passages across the Atlantic Ocean, particularly in the winter months, when they sailed west to New York. Battling the prevailing westerly winds and winter storms, the captains of the packets relentlessly drove their ships day and night. They shortened sail only when absolutely necessary. The fate of the ship depended on the crew, who often were laboring on deck or up the masts in a howling gale, soaked to the bone. Albion describes the sailors who crewed the packet ships as “tough men” who toiled for small wages in extremely perilous conditions. Danger abounded. In the middle of a black night, with a gale raging, snow falling, and ice on the rigging, the risk involved is hard to imagine.

From January through June in 1853, the marine newspapers carried stories of the deaths of eleven seamen on the Liverpool packet ships. On February 14, 1853, on the Albert Gallatin, Joshua Remick fell from a yardarm and drowned. As the captain wrote in the ship’s log, “It blowing a gale at the time, could not save him.” The following month, a log entry for the Queen of the West recorded: “12 days from Liverpool, carried away the foreyard [a yardarm on the first mast], foretopmast [top section of mast], lost sails. . . . At the same time Moses Stone, seaman, of New York fell from the masthead and was drown[ed].” With a gale blowing, the Queen of the West could not stop and search for Stone, knowing that he was doomed.22 Later in the year, on June 23, Peter Mulligan, sailing to Liverpool on the New York, fell overboard and drowned.

Sailors made their homes in the boarding houses and tenements lining the streets leading down to the East River waterfront. In crowded Ward 1 along the East River, the 1850 census counted over 16,000 people, including wealthy merchants living near the Battery, Irish immigrants, and a population of sailors farther up toward Corlears Hook. In November 1850, the census takers boarded all ships berthed on the East River, to enumerate the officers and seamen living on board. The census included sixty-five ships, with a total of 2,698 crew members, a few officers, and the rest simply listed as seamen, almost all of them born in New York.23 The 1850 US census counted Peter Mulligan among eighteen seamen aboard a ship berthed on the East River, in New York’s Ward 1. Born in New York, Mulligan, 47, the second-oldest crew member, served with John Haight, 17, the youngest.24

Men who made their living at sea often were not literate and were regarded as reprobates. They lived hard lives, many never married, and they died young. Even the Protestant religious reformers, who labored to improve the lives of sailors, viewed them with ambivalence. In 1828, members of the Brick Presbyterian Church founded the American Seamen’s Friend Society, to “improve the social, moral and religious condition of seamen . . . to rescue them from sin and to save their souls.”25 This society, along with the Marine Bible Society (1817) and the Society for Promoting the Gospel among Seaman in the Port of New York (1818), built a mariners’ church on Roosevelt Street, near the East River.

The Seaman’s Friend Society focused on the lives of sailors and their moral redemption. The society published the Sailor’s Magazine, which could be scathing in its descriptions of the seamen’s lives. An 1837 article gave a nod to the hardships they faced but then condemned their wayward life on the waterfront:

A sailor’s life is proverbially a hard one—his toils and sufferings are great—one would naturally suppose that at the end of a voyage he would take care of the small pittance he had hardly earned . . . or in enjoyment of some rational amusement and furnish him with instruction that would prove useful in the after life. . . . They seem to have no thought beyond the present moment—they often seek for pleasure in the indulgence of sensual appetites, at the expense of the moral or intellectual.

The sailor too often divides his time between his boardinghouse, which is often kept by a sharper or pickpocket, a grog shop and a brothel. He associates with the vilest of the vile and sacrifices alternatively at the shrine of intemperance and licentiousness . . . to lure him from the paths of sobriety, virtue and honor.26

Hundreds of grog shops and brothels crowded the East River waterfront and nearby streets, and sailors risked their lives on drunken sprees. On a hot August night in 1861, John Williams, a sailor, and a number of his shipmates spent the night drinking in a barroom at 346 Water Street, on the East River. Most of them “became drunk,” and a fight ensued. One of the sailors, Augustin Barco, pulled a knife and slashed Williams, “cutting him so severely that his liver was injured and his intestines came out.” He died on the barroom floor.27 A police officer immediately arrested Barco, who was later sentenced to prison.

The 1860 census enumerated a John Williams, a 30-year-old sailor, and his wife Mora, who were residing in a rooming house along the East River, in Ward 4. It was run by Margret Whitson, from Ireland.28 Unlike many sailors, Williams had a spouse and did not live in one of the notorious seamen’s boarding houses, but he was murdered in a bar on Water Street. A day before the murder of Williams, the body of another sailor, Patrick Kearney, was found in the East River, at the foot of Montgomery Street. The coroner ruled that Kearney, age 45 and a native of Ireland, “drowned while intoxicated.”29

Not only did the sailors fight with one another, but the waterfront toughs, who owned the bars, could also be as vicious. On a Saturday night in December, a year earlier, a police officer came across a sailor named Henry Bentaus, who was lying on the sidewalk on Albany Street. “Believing him to be drunk,” the office took Bentaus to a cell in the police station to sleep off his inebriation. The next morning the police found Bentaus dead in the cell and, on close examination, discovered that his skull was fractured. An investigation found that Bentaus and a fellow sailor, Henry Smith, had been drinking in a bar at 11 Albany Street, owned by Philip Collins. An argument over the price of drinks escalated, and Collins “snatched up a club and struck the deceased upon the head.”30 Smith fled for his life, and the police arrested both Collins and his wife, who had participated in the attack.

Like the longshoremen who worked the docks, sailors did not have permanent employment. They were paid by the month, but only while at sea. Once a voyage ended, they received their wages and, battered and bruised, they repaired to the nearest saloon or brothel along the East River to nurse their wounds and tell sea stories.

Seamen faced danger not only on the Atlantic Ocean, but also in the boarding houses, where rapacious owners waited to prey upon them. Boarding house scamps prowled the docks, waiting for a ship to arrive. They then scrambled aboard, with a bottle of rum under their coats, to offer a welcoming toast and steer the weary sailors to a boarding house as soon as they received their pay for the voyage. At the boarding house, food and liquor flowed, and once a seaman had spent his last dime, he lived on credit. In a few weeks he ran up a tidy sum owed to the boarding house, which he could not pay. Usually the bills were wildly padded and, since many sailors could not read, they were victimized. In this situation, a sailor faced just one course of action: to go down to the docks, find a ship ready for sea, sign the papers, and collect a one-month advance on his wages, which the boarding house owner immediately seized. This advance-wage scam persisted for decades, and over 200 boarding houses on the waterfront made tidy sums fleecing the seamen.

A Sailor’s Magazine editorial railed against the advance-wage system as “always wrong. . . . It is the main trunk of evil. . . . Many are sold under this system like sheep for the shamble.”31 Sometimes a wily sailor would simply disappear and not return to the ship. The landlord instead “sends the man to ship he wishes to get rid of, and the man who owes him the most. . . . He [the landlord] often finds force necessary to get his men upon the ship.” In some cases the sailors were kidnapped. In December 1857, a Mrs. Walters went to the police station and charged that her sailor brother, Alexander Chalmers, had been forcibly taken aboard the Liverpool packet Jacob A. Westervelt. Chalmers had been living at a notorious boarding house at 76 Roosevelt Street, run by Henry Boorman, where he “was knocked down and cruelly beaten and robbed of all money in his possession, amounting to $14,” his advance on wages.32 The police boarded the ship and searched it but did not find Chalmers. They returned again on Sunday morning. One officer climbed the mast and found Chalmers, bruised and beaten, hidden under a sail. The police then arrested Boorman. Their investigation found that the landlord “has been carrying on this kidnapping business for a long time” and, in the opinion of the prosecutor, “in a manner so flagrant as to secure incarceration in Sing Sing.”33

Protestant reform ministers and the New York Chamber of Commerce launched a campaign, led by the Seamen’s Friend Society, to end the practice of advance wages and have all the sailors’ boarding houses registered and inspected by the police. The New York Times reported on the reform efforts to end the advance-wage system and instead offer sailors a wage increase of $5 a month if they signed on without advance payment. The reform seemed to be moving forward in 1857, as “one hundred and fifteen New York ship-owners immediately signed an agreement to pay no more advance wages after the first day of July, 1857.”34 The voluntary effort failed, however. Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia shipowners refused to go along, and the sailors in New York, against their own self-interest, resisted ending the advance-wage system.

As long as ships crowded the Port of New York, the city remained the temporary home for the tens of thousands of sailors who lived itinerant lives and often died young, racked by rheumatism and consumption from years spent at sea. They might sail one voyage with a good crew, and another with the scrapings of the bars on South Street, with some of the crew members shanghaied drunk and sold by landlords to an outgoing ship. Joseph Conrad captured the poignancy of the deepwater sailors’ lives: “A gone shipmate, like any other man, is gone forever and I never met one of them again. But at times the spring-flood of memory sets with force up the dark River of the Nine Bends. . . . Haven’t we, together and upon the immortal sea, wrung out a meaning from our sinful lives? Good-bye, brothers! You were a good crowd. As good a crowd as ever fisted with wild cries the beating canvas of a heavy foresail; or tossing aloft, invisible in the night, gave back yell for yell to a westerly gale.”35

Just as the New York packets dominated the North Atlantic route to Liverpool, London, and Le Havre, the city’s shipowners and merchants gained control of the waterway routes along the Atlantic seaboard to the southern cotton ports. Almost at the exact time the Black Ball Line began service to Liverpool, a number of packet lines initiated scheduled service south to the cotton ports: Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and the all-important New Orleans. Despite the significance of the cotton trade, Albion argues that the role of the southern packet lines has never received the same level of research afforded the transatlantic packet ships. Coastal shipping data is scarce, since the US Customs Service gathered detailed information regarding imports and exports to foreign countries, but little regarding coastal service.36

A group of New York shipowners and merchants, with the same drive to succeed as the Liverpool packet-line owners, started the Charleston Shipping Line in 1822, which continued service until 1849. The Charleston Line operated a total of twenty-one ships. The Bulkley shipping family of Southport, Connecticut, a small seaport located in the town of Fairfield on Long Island Sound, started a second Charleston line in 1843, which lasted only until 1850. The Savannah Line began service to Georgia in 1824, while the Mobile Line first sailed in 1826.37

Fast, reliable, scheduled sailing led to the success of New York’s southern lines, just as it did with the North Atlantic packets. For Liverpool merchants exporting textiles and manufactured goods to the South, it proved to be more reliable and faster to send cargo to New York and then south on a packet ship than to ship it directly from Liverpool to Charleston or New Orleans. Albion’s label for New York’s control of both the transatlantic and southern marine highways is “enslaving the cotton ports.” He states: “The chief exports from New York included cotton, rice and naval stores, grown hundreds of miles to the southward, while the South received most of its foreign imports by way of New York, instead of going to Europe direct, [so] these commodities [especially cotton] have to travel about two hundred miles further. . . . Also there was the added costs of unloading the commodities from one ship and loading them into another at New York.”38

During the nineteenth century, a very small fraction of American imports from Europe went directly to the South. In 1850, US imports totaled $178 million; only 7.1 percent came through the ports of Charleston and New Orleans, while the Port of New York accounted for 58 percent. By far the most important southern packet service was the one linking the city of New York to New Orleans. Four major packet lines served New Orleans, beginning in 1821 and continuing until the Civil War. The largest, the Holmes Line, operated twenty-eight packet ships, starting with the Edwin, the Chancellor, the Lavinia, and the Crawford in 1824, to their last ship, the Glad Tidings, in 1858. New Orleans became the major southern cotton port and, by the mid-1840s, was home to more millionaires, whose fortunes were created by the rise of the empire of cotton, than any other city, including New York.39 The southern packet lines directly tied the Port of New York to the American South and its cotton empire.

With over a hundred packet ships on regular schedules between New York and the southern ports, a great deal of the cotton shipped to Liverpool and Le Havre first went to New York. There it was unloaded, carted from one pier to another, then reloaded onto a Liverpool or Le Havre packet, and carried across the Atlantic Ocean. New York shipping interests profited handsomely. Not only did they own the Atlantic packet ships, but the leading New York merchants also invested in the southern lines. In addition, they owned many of the ships sailing directly from Charleston and New Orleans to Liverpool, further controlling the cotton trade.

Generations of American history books include a map of the “cotton triangle,” with the first leg being cotton shipments from the South to Liverpool; the second, textiles and industrial goods from Liverpool to New York; and the third, imports from Europe to the South by way of New York. In many cases, this “triangle” had only two legs: from the South to New York and on to Liverpool; and then back to New York, with the ships’ holds filled with imported textiles, manufactured goods, specie, and bills of credit to be settled by the New York banks.

Throughout the entire nineteenth century, the American economy’s most valuable product was cotton. All other agricultural and industrial activities paled by comparison. At its heart, the cotton kingdom rested on the labor of an enslaved population of African Americans, as did the economy of the United States. “Cotton had indeed a phenomenal place in the whole American economy; a dominance never since obtained by any single American product of factory and field.”40 In the rise of King Cotton, the port and city of New York played the pivotal role.

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and the annexation of the Mississippi Territory in 1804, created a vast inland empire for expansion. President Thomas Jefferson envisioned the settlement of these territories by independent white pioneers, who would labor on their small family farms and provide the bedrock for a democratic polity. Manufacturing would remain in Europe, while, in the American heartland, an agricultural economy built around the small family farm would flourish.

In the South, Jefferson’s dream never became reality. On the contrary, an empire of cotton emerged, dependent on “the expansion of black slavery; the racial privilege of the ‘empire for liberty’ contained within it the seeds of the Cotton Kingdom.”41 Slavery dominated the tobacco, rice, turpentine, and wood economies of the original southern states along the Atlantic seaboard. The first US census, in 1790, counted a slave population of 697,624, with 90 percent (628,107) in Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. With the Louisiana Purchase and the expulsion of the Native Americans there, vast new lands in the Mississippi River Valley were opened to the cotton boom. In 1820, the slave population of Alabama, western Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana totaled 183,358, and it grew to 385,982—an increase of 110 percent—in just a decade.42 By 1840, the slave population in the Deep South exceeded the number in the original southern states. Walter Johnson claims that, between 1800 and 1830, over 1 million slaves were moved from the coastal southern states to the Mississippi River Valley, in what he calls a “river of dark dreams.” He estimates that one-third left with “their masters as part of intact plantation relocations, the other two-thirds of whom were traded [i.e., sold] through a set of speculations that was quickly formalized into the ‘domestic slave trade.’ ”43 Owners and slave drivers chained the slaves, bought in Maryland or Virginia, and then mercilessly drove them south to the Mississippi River Valley.

Cotton production increased in the first decades of the nineteenth century and then soared in the three decades before the Civil War. On the new plantations in the Mississippi River Valley, the transported slaves cleared the land, planted cotton, and then harvested it in the sweltering heat of late summer and early fall. During the harvest season, the overseers herded the slaves into the fields at sunup and worked them until sundown. The overseers demanded that each adult slave pick 100 pounds of cotton a day, with their children often toiling beside them.

By 1839, cotton production in the Deep South accounted for over 60 percent of the total cotton production in the United States. In 1860, at the start of the Civil War, three cotton states—Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana—grew 78.8 percent of the total. Each bale weighed approximately 400 pounds.44 In 1810, the number of bales produced in the South totaled 285,800 and rose to a staggering 4,696,553 bales fifty years later.

Long before America’s industrial revolution, an agricultural revolution in cotton dominated the country’s economy, foreign trade, and the Atlantic World. A wide-spanning cotton web linked the American South, the Port of New York, Liverpool, and northern England, based on black slavery in the South and wage slavery in the textile mills in Manchester.45 Cotton fully dominated the exports of the United States.46 By 1830, fifteen years after the War of 1812, cotton totaled over 50 percent of all exports. By comparison, flour, the bounty from the Midwest shipped from the Port of New York, accounted for a modest percentage of all exports: 9.1 percent in 1840, and 4.8 percent in 1860. Cotton production in the South recovered after the Civil War, and once again cotton exceeded the value of all other exports.

New York–based ships provided just one component of New York’s involvement. The city’s merchant banks provided the financing to grow the cotton and transport it from the plantations to the cotton ports and then across the Atlantic Ocean. A complicated system of credit from the New York merchant bankers allowed the cotton planters, paid once a year, to finance their operations until the cotton reached Liverpool and the mills in Manchester. Payments arrived in New York on the packet ships, and the counting-houses settled accounts. Dattel argues that “cotton propelled New York to commercial dominance” throughout the nineteenth century. New Yorkers played the roles of “the financier, the shipper, the insurer, the factor, the broker, the mill owner . . . [and] the merchant.”47

Brown Brothers, a firm of New York shippers and bankers, illustrates the complexity of the international cotton business. Alexander Brown, the founder, emigrated from northern Ireland in 1800 and settled in Baltimore, where he opened an importing firm. As his business grew, he sent his sons to open branches elsewhere in the United States and in Liverpool. In 1810, William Brown formed Brown Shipley in Liverpool, which became one of the largest cotton importers in England. His brother James moved to New York and, in 1825, established Brown Brothers & Company, today Brown Brothers Harriman.

In the 1850s, Brown Brothers’ estimated worth grew to between $12 and $14 million, and “cotton was one of their main interests.”48 The firm seldom bought cotton in the South for its own account. Doing so was always a risk, given the price fluctuations between paying the planter and then selling the cotton in Liverpool four months later. Rather, Brown Brothers served as middlemen, taking cotton on consignment from the South and then brokering the cotton on its arrival in Liverpool, generating a safe, profitable commission of 2.5 percent. Brown Brothers also arranged for shipping and insurance, adding additional fees.

Their most valuable service involved managing the credit that underpinned the entire cotton web. In 1838, on consignment, the firm handled 1,163,155 bales of cotton exported to Liverpool—15.8 percent of all American cotton—and their commission income totaled $199,738. All of the buying, shipping, and sales involved letters of credit, or bills, which constituted legal tender and could be sold or traded in the southern cotton ports, New York, Liverpool, and London. The trade always involved a discount on the face value of the bills, to assuage the risk involved in buying and selling on credit instead of with hard currency. In 1827, the bills traded by Brown Brothers totaled $132,918.44.49 With their related firm of Brown Shipley in Liverpool, Brown Brothers in New York moved a vast amount of English and American specie back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean, a service for which the packet ships charged a hefty premium. Between November 1826 and December 31, 1827, Brown Brothers shipped $760,538.98 in specie from Liverpool to New York to settle accounts.

In his prize-winning book, Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Sven Beckert contends that merchants, such as Brown Brothers, “were more often independent intermediaries. They specialized not in growing or making, but in moving. At great headwaters such as Liverpool [and New York] they constituted the market; they were the visible hand.”50

Brown Brothers played another key role in the cotton web, serving directly as what were known as factors in the South. Factors worked out of the southern cotton ports and specialized in providing credit and management services directly to the plantation owners:

A so-called factor had to first provide the planter with credit to acquire slaves, land and implements. This factor probably drew on London or New York bankers for these resources. Once the cotton had ripened the factor would offer the cotton for sale to exporting merchants in New Orleans [or in other southern ports], who would sell it to importing merchants in Liverpool who would also provide insurance on the bales and organize the shipping. . . . Once in Liverpool, the importing merchant would ask a selling broker to dispose of the cotton. As soon as a buying broker found the cotton to his liking, he would forward it to a manufacturer. . . . The web of cotton consisted of tens of thousands of such ties.51

Brown Brothers opened offices in the major southern cotton ports, including New Orleans, in order to provide the services Beckert enumerates. Had the credit system not been available, the expansion of the cotton web into the Deep South would have faltered, and the economic justification for the expansion of slavery would have been decisively weakened. Entries in the books of their New Orleans office record in detail the credit advanced to the plantation owners. For example, this office kept track of all credit advanced to the Bellevue Plantation in Saint James Parish, Louisiana, which was near Lafayette: from the mundane $4 for water buckets, and $70 to repair a cotton gin, all the way up to the salary of the plantation’s overseer, one John M. Denneut, which was $800 “for one year to Dec. 31, 1843.”52 Robert Watson, the overseer of the Stamps Plantation, received cash advances of $200 and $400, recorded in March 1844, and then, farther down the page, an entry that simply reads, “Paid A. Peter for two Negroes Maurice & Jean Baptise . . . Cash Dec. 19, 1843, $1,300.” Another entry documents the purchase of additional land to expand the cotton slave economy, stating, “Paid Theo Edwards order for A. S. Robertson for the Amt. being lands purchased . . . $3,350.”53

The New Orleans office arranged to forward the Bellevue cotton, on consignment, from New Orleans to Brown Shipley in Liverpool. In Liverpool, Brown Shipley brokered the sale of “291 Bales Cotton as follows,” with a commission of 5.5 percent for Brown Brothers. The cotton sold in Liverpool was paid for in pounds sterling and generated $653.40 in commissions. The New Orleans office also charged the plantation $323.60 for shipping the cotton from New Orleans to Liverpool. The ledger books of the Brown firms include what was listed as “profits” for the Charleston, Galveston, New Orleans, Mobile, and Savannah offices, which totaled $58,691 in 1871 and $62,946 in 1872, each the equivalent of well over $1 million today.54

Brown Brothers financed both sides of the Atlantic cotton web and provided the indispensable money, contacts, and expertise to further the most complex commercial relationship of that time period. New York served as the all-important nexus for a century or more. Even the bloody Civil War proved to be merely a temporary interruption.

On the other side of the Atlantic World, the Industrial Revolution created an insatiable demand for cotton, the product of American slavery. A remarkable group of mechanics and artisans in northwestern England began a revolution with innovations in iron making, steam engines, and—most importantly for cotton production in the United States—the mechanization of the textile industry. Without the demand from the English textile mills, there would have been little financial incentive to expand the cotton empire in the Deep South.

Liverpool, Lancashire’s window on the Atlantic World, grew to be one of the world’s busiest ports, with cotton as its chief import. By 1826, cotton from the United States accounted for 65 percent of all cotton imports to Liverpool from across the Atlantic Ocean. Between 1830 and 1835, it grew to 75 percent and, by 1845, to 80 percent.55

The New York–Liverpool packet lines created a virtual marine highway, with cotton ensuring that both port cities flourished. In 1818, the Black Ball Line packets carried 2,004 cotton bales and 6,447 barrels of flour. The following year, that line’s freight to Liverpool included 3,210 cotton bales and 3,232 barrels of flour. Cotton had greater value than flour, as freight charges were higher for transporting cotton bales.56 From the very beginnings of the Black Ball Line and the other Liverpool packets, shipping cotton to Liverpool and textiles back to New York generated a major portion of the profits.

The Port of New York captured a significant share of the cotton shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, shortening the “cotton triangle” to two legs. To illustrate the cotton trade’s importance to the Port of New York, in September 1828, fifty-two American ships arrived in Liverpool, transporting a total of 38,995 bales of cotton. Each ship carried an average of 750 bales. The amount shipped directly from New York was 9,828 bales, or 25.2 percent of the total, and that coming directly from New Orleans, 10,034 bales.57 Thirty years later, in September 1855, twenty-four American ships carried 50,828 bales of cotton to Liverpool, with an average of over 2,000 bales on each ship. New York’s share of the total was 22.5 percent, while the ships sailing directly from New Orleans carried 38 percent of the American cotton arriving in Liverpool.

The port of Liverpool, on the north side of the Mersey River, provided the crucial point linking the Deep South to England’s textile revolution. The rise of Liverpool as England’s great entry port parallels the rise of the Port of New York, but the physical geography of that river and the Liverpool waterfront differed dramatically from New York’s.

The Mersey River has the second highest tidal rise and fall in Britain. At low tide, mud flats extend from the shore well out into the river, so piers could not be constructed. For Liverpool’s port to prosper, the city of Liverpool, at great public expense, set out to build a marine world completely different from the Manhattan waterfront. The solution was to build wet basins along the shore, which ships could enter at high tide. Then the basin gates would be closed, and the ships moored to waterside quays. As the tide receded, the basins remained full of water.

Liverpool constructed Old Dock, the first of many wet basins, in 1715. By 1821, with the completion of Prince’s Dock, the total cost of the basins exceeded £2.6 million, a vast sum for that time.58 The city borrowed the money for construction and then charged each ship entering the basins, in order to pay back the principal and the interest. The city also managed the docks and used surplus revenue to maintain the basins as a public service. Shipping drawn to Liverpool increased dramatically, just as it did in the Port of New York. On the other side of the North Atlantic waterway, along the Manhattan waterfront, private owners with water-lot grants built additional wharves and piers at a much lower cost.

The building of the Liverpool basins provides an example of public as opposed to private enterprise, such as in the case of the piers and wharves in the Port of New York. To be fair, the amount of capital needed to construct the costly wet basins was beyond the resources of the Liverpool merchants. Liverpool prospered with this public investment in the waterfront. In a history of the rise of the port of Liverpool, published in 1825, Henry Smithers summarizes the impact of the city’s investment, listing “the advantages derived from the accommodations afforded shipping by the new docks [wet basins]. They attracted new streams of commerce to the port . . . and amply repaid the investments therein. . . . The docks served to find employ for an industrious and annually increasing population. . . . Increasing wealth . . . [resulted] once [the] ‘poor decayed town of Liverpool’ reared her head and claimed to rank with the great commercial ports of ancient and modern times . . . and even with London, that emporium of the British empire and of the commerce of the world.”59

This description mirrors the rise of the Port of New York, with one important distinction: a reliance on private capital and private initiative. The city of New York ceded waterfront development to private interests, something Liverpool never did. Liverpool’s public control of the waterfront included regulation of the longshoremen, 100 years before major reforms took hold in New York. In Liverpool the longshoremen no longer had to face the shape-up, but instead worked regularly in a specific basin.

Across 3,000 miles of ocean, New York and Liverpool played complementary roles in the transatlantic waterway empire’s cotton web. The rise of the port and the city of New York to commercial dominance depended on the elaborate cotton web, which ran from the slave plantations in the Deep South to New York and, through Liverpool, to the textile mills in Manchester.