The success of the packet lines and the expansion of New York’s waterway empire solidified the Port of New York as the most important in the country. As the city’s population continued to grow and its industrial bases expanded, demand for space on the waterfront increased exponentially. An ever-increasing number of ships arrived and departed each year, and thousands of canal barges brought the bounty of the Midwest to the port. Hundreds of small sailing vessels carried food and building materials from the nearby hinterland. For example, the US Bureau of Customs kept detailed records of vessels entering the United States directly from foreign countries. Between 1845 and 1860, the number of such ships rose from about 2,000 a year to over 3,500 in 1850, and then to 3,962 in 1860.1

Albion compiles data comparing foreign and coastal arrivals in 1835 to New York and to its closest rivals, Boston and Philadelphia. A total of 240 “ships,” at that time meaning three-masted sailing vessels, arrived from Liverpool: 168 to New York, 38 to Boston, and 34 to Philadelphia, making New York’s share 70 percent. From London, 50 ships arrived, with 44 going to New York. For the famed China trade, where Boston and Salem once dominated, 32 ships arrived on the East Coast from Canton, and 24 of these sailed through the Narrows to piers on South Street. New York also dominated the coastal trade routes to the American South, including the cotton ports of Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans. Ships arriving from the four southern ports totaled 1,066, with 712 coming to the Port of New York.2

In 1852, the New York Times began to publish the “Marine Intelligence” page almost daily, detailing arrivals and departures. The list, organized by type of vessel, included information identifying either the port the ships arrived from or their destination. New York’s merchants and shippers read the report with great care, to stay abreast of their competition. The “Marine Intelligence” page illustrates the global and coastal reach of New York’s maritime commerce by the 1850s. For example, on June 23, 1852, two steamships departed for Charleston and Glasgow, Scotland. Six sailing ships (three-masted) cleared for Spain, London, Charleston, Northern Ireland, and St. Stephen in New Brunswick, Canada.3 Thirteen smaller barks and brigs set sail for Cuba; Gibraltar; Mexico; Bermuda; Bremen, Germany; Bergen, Norway; Kingston, Jamaica; Nova Scotia; and Philadelphia. Thirteen schooners left for ports up and down the coast from Boston to Jacksonville, as well as one to Harbour Island in the Bahamas and another to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. In addition, ships docked at the port from other distant shores: Bremen, Marseilles, Rio de Janeiro, and Puerto Rico. Coastal ships included the Kelly from Savannah (a voyage of seven days) and the Moses from Charleston (five days in transit), both loaded with cotton either to be transferred to the packet ships bound for Liverpool or shipped via Long Island Sound to the New England cotton mills. Along with the largest of the sailing ships, thirty-one smaller schooners also arrived.4

The Alliance from Le Havre, France, with 348 passengers, made port after a trip of thirty-six days across the Atlantic Ocean. The Milicot, a British ship from Dublin, carried salt and 299 passengers. The Black Ball ship Isaac Wright, thirty-five days out of Liverpool, brought another 531 passengers. On this one June day in 1852, 1,178 people landed at the East River piers, almost all of them immigrants. Although they arrived on a crowded waterfront, filled with goods from all over the United States and the world, these passengers may have stopped and realized they had passed through the “golden door,” Emma Lazarus’s evocative description of New York, inscribed on the Statue of Liberty.

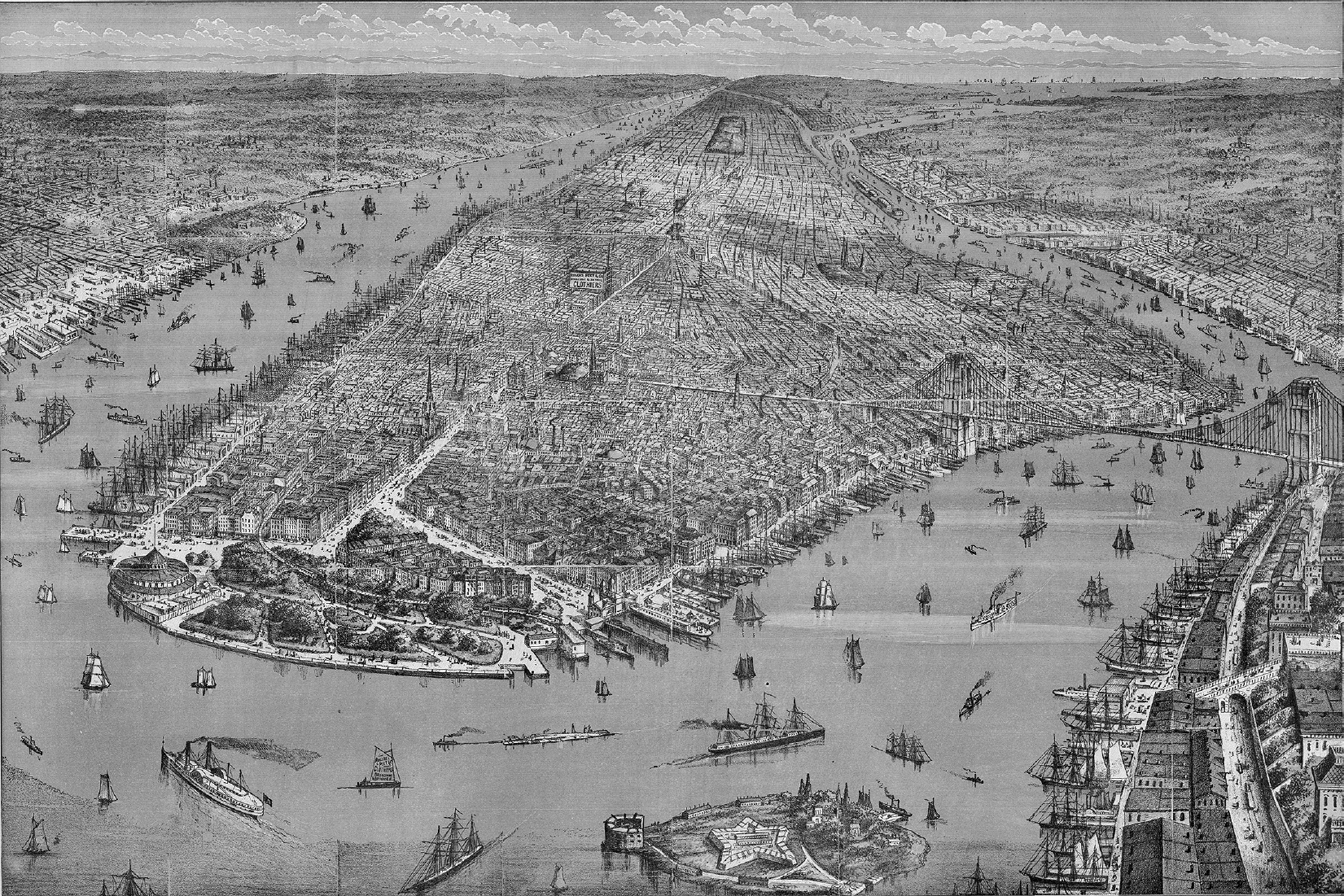

With thousands of ships in the port on a daily and weekly basis, the demand for pier space far exceeded the amount available. A New York State study of the harbor reported that on almost any given day, 300 ships waited for space on the waterfront. An 1879 lithograph of the port and the Manhattan waterfront illustrates the scale of its maritime activity (fig. 6.1). In the foreground are sailing ships and a steamer heading down the East River from Long Island Sound. Three-masted sailing ships occupy many of the piers along the Hudson and East Rivers, and hundreds of small sailing vessels ply the waters around the island. Every pier along the East and Hudson Rivers is filled. The Brooklyn Bridge connects Manhattan to the city of Brooklyn, and the piers along Brooklyn Heights to the south of the bridge are full.

Figure 6.1. The Port of New York and the Manhattan waterfront, 1879. By the 1870s, the port was the second busiest in the world. Hundreds of ships of all types and sizes crowded the harbor, the East and Hudson Rivers, and the Brooklyn waterfront (in the foreground). Source: Rogers, Peet & Company, 1879, Library of Congress

Not only did the world’s shipping make its way to New York, but the railroad era also drew all the country’s major rail lines to the port. After his shipping triumphs, Cornelius Vanderbilt dominated New York State’s railroad history in the second half of the century.5 Vanderbilt did not build railroads, he acquired them. His two most important acquisitions were the New York & Harlem Railroad and the Hudson River Railroad. Both of these had an incredibly valuable asset: their charters gave them the right to operate on Manhattan Island and to build their tracks in the middle of the city’s streets.

In 1831, the State of New York awarded a franchise to the New York & Harlem to build a railroad to connect the southern tip of Manhattan Island with the village of Harlem, today the area around 125th Street.6 The New York & Harlem’s first trains used horses for power, and its tracks ran up 4th Avenue, later renamed Park Avenue. In 1837, the railroad finally reached Harlem. The state legislature then extended its franchise to White Plains in Westchester County and, later, to Chatham in Columbia County, to join the Boston & Albany Railroad. Although never a prosperous railroad, the Harlem had one superlative asset: the right to operate on the island into Midtown Manhattan.

In 1846, the state legislature granted a charter to a group of investors from Poughkeepsie, New York, to build a railroad down the east side of the Hudson River to New York City. The Hudson River Railroad crossed the Harlem River at the northern tip of the island and then went all the way down the West Side to St. John’s Park Depot, blocks from city hall (map 6.1). Like the New York & Harlem, the Hudson River Railroad held the right to use the city’s streets along the river, an asset as valuable as the New York & Harlem’s Park Avenue rights. The Hudson River Railroad built tracks down the middle of 11th Avenue, 10th Avenue, and then south on Hudson Street to St. John’s Park Depot. The city had previously granted water-lots to private individuals to develop the port’s maritime infrastructure. Then, as the railroads arrived, the city and New York State granted the private railroad companies the right to another valuable municipal asset: the center of the city’s public streets.

Vanderbilt made a fortune during the Civil War, leasing his steamboats to the Union Army to transport troops and supplies. As the war drew to a close, he began to acquire shares of the New York & Harlem, Hudson River, and New York Central Railroads. The Central, in 1853, consolidated ten small upstate railroads built parallel to the Erie Canal, following the water-level route across the state. Vanderbilt became president of the Central and then set a plan in motion to combine it with the Hudson River Railroad, forming the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad. In a few more years, Vanderbilt had assembled a railroad system from New York City to Buffalo. He then acquired other railroads, extending his system to Chicago. His railroad empire grew to be the second largest in the country, after the Pennsylvania Railroad, always a fierce rival. The Central’s greatest asset remained its direct access to Manhattan Island. Vanderbilt constructed Grand Central Depot at 42nd Street, to serve as the primary passenger terminal in the city for all of his railroads until this structure was replaced in the beginning of the twentieth century by the magnificent Grand Central Terminal.7 The Central aggressively defended its monopoly on direct access to Manhattan and the right to use the city’s streets.8

Map 6.1. The Port of New York railroads, showing the New York Central Railroad in Manhattan and rival railroads in New Jersey. The New York Central freight operations enjoyed an enormous advantage, with tracks running along the Hudson River to St. John’s Park Depot in Lower Manhattan. All of the rival railroads’ tracks ended on the New Jersey waterfront, a mile short of their final destination. Source: Bill Nelson map from Kurt Schlichting, Grand Central’s Engineer: William J. Wilgus and the Planning of Modern Manhattan (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013)

All of the other major railroads in the country—the Baltimore & Ohio, the Erie, and the Pennsylvania—realized that their trains must reach the Port of New York. The smaller railroads serving New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania—the Central Railroad of New Jersey; the Lehigh Valley; and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western—also raced to offer passenger and freight service to the port. These railroads acquired track rights and built train yards in Jersey City, Hoboken, and Weehawken. Not one of them could bring trains onto Manhattan Island. All of their rail facilities terminated on the New Jersey side of the Hudson River, a mile-wide barrier (map 6.2). Hundreds of freight cars arrived on the Jersey shore each day, along with thousands of passengers, and both needed to cross the Hudson to their final destination: Manhattan.

Thus railroads on the New Jersey side desperately required space on the Manhattan waterfront. If not, they would fall behind their rivals. Therefore, at great expense, these railroads secured permanent access to the Manhattan shorefront. With long-term leases for piers and bulkheads, the railroads built large freight pier sheds on West Street. The Delaware, Lackawanna & Western shared its freight depot at Pier 13 with the Starin Line, which operated both Hudson River and Long Island Sound steamboats.

In a brief period of time, the railroads pushed aside the maritime interests. For example, between the Battery and Cortlandt Street, the Pennsylvania Railroad leased Piers 2, 3, and 4 and the bulkhead between the piers. Up the Hudson River, the Lehigh Valley Railroad leased Pier 8, and the Central Railroad, Piers 10 and 11. Three ferries, two to New Jersey and one to Staten Island, had terminals on Piers 14 to 18. By the close of the Civil War, railroads and ferries occupied most of the waterfront along the Hudson River between the Battery and Gansevoort Street, just north of Greenwich Village.

For centuries, the Port of New York’s prosperity had rested on its international and coastal shipping links with Liverpool, Europe, the cotton ports in the American South, and the city’s inland waterway empire. Yet in the later fight for space, shipping companies—from the transatlantic steamships to small sloops and oyster boats—found themselves edged out, by both Vanderbilt’s lines and the other railroads whose tracks terminated across the river in New Jersey. As the short-term leases held by many of the small shipping companies expired, the railroads, with far more financial resources and political muscle, negotiated long-term leases for piers on the Hudson River.

The New York packet ships, and the clipper ships that followed during the era of the California Gold Rush, represented the culmination of the great age of sail. The Black Ball packet ship Yorkshire set that line’s record, sailing west from Liverpool in sixteen days, an average of over 150 nautical miles a day. During the gold rush, the clipper ships set records sailing to San Francisco and on to China. The steamship revolution, however, would eclipse even the great age of sail and dramatically reduce passage times, both on the Atlantic Ocean and on the Hudson River routes to Albany and Long Island Sound.

The Industrial Revolution brought steam power to the city’s waterway empire, offering faster voyages across the oceans, down the seacoast, or through the Sound to New England. Iron replaced wood as the primary construction material for ocean-going and coastal ships. With an iron skeleton and a hull built with iron plates, ships could be larger in both length and width and thus carry more freight and passengers.

The first use of steam power on ocean-going vessels involved sailing ships with an engine and paddlewheels, used as auxiliary power when the wind died. In 1817, a group of cotton merchants in Savannah, Georgia, contracted with the Flickett & Crockett boat yard on the East River to build a sailing ship with a steam engine and detachable paddlewheels.9 On August 22, 1818, the Savannah slid down the ways into the East River. In March of the following year, the steamer left New York for the run south to Savannah and reached that city in eight days. On May 24, the ship set off across the Atlantic Ocean for Liverpool, arriving twenty-seven days later. The Savannah steamed up the Mersey River to great fanfare, but in crossing the Atlantic, the ship mainly relied on the wind and had used its auxiliary steam engine for only 80 hours.

On both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, entrepreneurs raced to raise money to begin transatlantic steamship service. A steamship could make six or seven crossings a year, compared with three or four for the fastest packet ships. On the British side of the Atlantic, in 1839 the famous engineer and polymath Isambard Kingdom Brunel built the Great Britain in Bristol, England, for the Great Western Steamship Line. At 322 feet long, the Great Britain exceeded the length of the largest packet ship—the 216-foot Amazon on London’s Black X Line—by over 100 feet. Built with an iron hull, not wood like the packet ships, she had a screw propeller, which was more powerful and reliable than a paddlewheel. The true revolution came with this ship’s first crossing to New York, in fourteen days! The fastest passage of any packet ship in the half century between 1818 and 1868 took sixteen days, and most crossings averaged thirty-five days, more than double the Great Britain’s time. By crossing the Atlantic Ocean in twenty fewer days than the average packet ship, the Great Britain ushered in a new era that changed transportation and communications in the Atlantic World, nineteen years before the first transatlantic telegraph cable.

The success of the Black Ball and other Liverpool packet lines rested on their scheduled departures from New York and Liverpool, no matter what the weather, but the packets could not control the dates of their arrivals. While they averaged thirty-five days going across the Atlantic Ocean, passengers boarding in Liverpool had to hope the weather favored their crossing. The steamships, on the other hand, advertised both departure and arrival dates. New York newspapers reported when a steamship missed its scheduled arrival, something they seldom reported for packet ships. Once the steamship lines began regular service across the Atlantic, they competed to offer the fastest service, which further spurred innovations in ship design and the construction of more-powerful steam engines.

The British government offered substantial subsidies to carry the Royal Mail across the Atlantic Ocean. Samuel Cunard—who hailed from Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he operated a successful steam-ferry business—hurried to England and, with a group of Glasgow investors, bid on the mail contract. In 1839, Cunard won the contract to carry the mail twice a month, by steamer, from Liverpool to Halifax and then on to Boston, not New York. For decades, the proud Boston merchants watched as the Port of New York grew, while the maritime commerce of their city fell further and further behind. The Cunard Line’s service promised to reverse the decline of Boston’s port, and the first Cunard steamships to arrive there enjoyed a warm welcome. Cunard’s subsidy from the British government to carry the mail—£60,000 a year, which was the equivalent of over $300,000 in 1840—gave that line a substantial advantage over the competition. In 1848, with additional mail subsidies from the British government, Cunard added direct service to New York from Liverpool.

Once the Cunard Line began service, wealthy passengers abandoned the packet ships. Steamships soon carried the money and financial documents that underpinned the cotton web. Bills of exchange—the heart of the merchant banking system—which once were negotiated for three months’ duration, could now have terms of thirty days or less, substantially reducing the risk involved in the international cotton trade.10

On the American side of the Atlantic, New York merchants and shippers complained loudly about Cunard’s subsidy, and his steamship line would not remain without rivals. In the 1830s, the New York–based shipping firm of Israel Collins and his son Edward prospered, shipping cotton north by running a packet line between New Orleans and New York. In 1835, they loaded one of their New Orleans packets, the Shakespeare, with cotton and sent it to Liverpool. The ship returned to New York with textiles and manufactured goods. The profits thus earned convinced Edward Collins to start his own packet service to Liverpool, the Dramatic Line, the following year.

Collins carefully followed the success of Cunard’s steamship service to Boston and New York. In response to the subsidy provided by the British government, the United States Congress awarded a mail subsidy of $200,000 to Collins, and in 1848 he began the United States Steamship Line. He immediately ordered four new wooden steamships from the East River shipyard of Brown & Bell: the Atlantic, the Pacific, the Arctic, and the Baltic. John Morrison, in his History of American Steam Navigation, estimates the cost of each ship at $736,000, far more expensive than a Liverpool packet ship powered by sail alone.11

On April 27, 1850, Collins’s Atlantic left New York for Liverpool. Now Cunard would face stiff competition from an American line. The following year, the Baltic set a new record for the passage from Liverpool to New York: 9 days and 18 hours. No wonder the steamships captured the market for high-end passenger service across the Atlantic Ocean. For all of the fame of the Black Ball packet ships and their hard-driving captains, the fastest passage ever completed by a packet ship took sixteen days.

The Baltic’s record-setting speed came at a cost. The new steam engines, built by the Novelty Iron Works, proved to be unreliable and in need of constant repair: “The expenses at the end of every return trip to New York for repairs to the engines and boilers, after the vessels had been running a short time, was very great. Large numbers of mechanics being [sic] sent from the Novelty Iron Works, who worked day and night until the repairs to the machinery were completed, that in some cases were but a few hours before the time of sailing, that had become necessary by the heavy strain that had been put on the machinery during the voyage.”12 On one voyage, another Collins ship, the Atlantic, broke a drive shaft a few days after leaving and had to use its sails to return safely to New York for repairs. An army of mechanics from Novelty worked around the clock to repair the damage.13

Then disaster struck. On September 27, 1854, south of Cape Race at the southern tip of Newfoundland in Canada, the Arctic, racing through dense fog in hopes of setting another record, collided with the French ship Vesta. The captain of the Arctic turned north in a desperate attempt to reach Cape Race, but after 4 hours, the ship started to sink. Panic ensued on board. One newspaper reported that drunken passengers and crew members destroyed the bar, and liquor flowed in the scuppers along the deck. Some of the crew abandoned the passengers and seized two of the four lifeboats. In all, 35 crew members and only 14 passengers reached the coast of Newfoundland. The remaining passengers and crew—a total of 315 souls—perished, since even in late summer, the waters around Newfoundland are bitterly cold. Among the dead were Edward Collins’s wife, son, and daughter.

The calamity set off a flurry of demands to improve the safety of passengers traveling on the steamships, starting with new regulations mandating a sufficient number of lifeboats aboard, with space for all passengers and crew. A New York Times editorial assigned the major cause of the tragedy to “an entire lack of disciplined control over the crew of the ship. No authority enforced or directed their actions. While the passengers worked the pumps, the firemen, seamen, engineer . . . seem to have been seeking their own security.”14 Captain Luce did not survive to face harsh questioning about the breakdown in discipline. Yet with only four lifeboats on the Arctic, even the most heroic efforts of the captain and crew could not have saved all aboard.

Edward Collins, despite his personal tragedy, continued his headlong competition with Samuel Cunard. Fate, however, dealt him another blow. Just over a year after the Arctic tragedy, the Collins steamship Pacific left Liverpool on a cold January 25, 1856. Carrying only 45 passengers and a crew of 140, the Pacific went “missing” and disappeared without a trace.

Two maritime disasters in the space of two years led Congress to end the mail subsidies, and the Collins line went out of business. Collins and his New York State legislative allies had faced vicious opposition to the subsidies from southern interests, who saw the grants as a blatant effort to sustain the maritime supremacy of New York at the expense of the South. From that point on, British companies completely dominated the transatlantic passenger service for the coming decades and well into the next century.15

In the years that followed the demise of Collins’s line, transatlantic freight and passenger service continued to grow, as did the number of foreign steamship lines offering service across the Atlantic Ocean. By 1870, four British lines operated between New York and Liverpool, one provided direct service to and from France, and two German steamship companies ran between New York and the ports of Bremen and Hamburg.16

Not only did the European companies dominate the North Atlantic luxury passenger and high-value freight business, putting more and more ships in service each year, but the size of their ships also increased dramatically, a result of the switch from wood to iron in shipbuilding. This new generation of steamships, all iron-hulled, traveled at twice the speed of the fastest packet ships and, in moderate weather, sustained that speed for the entire voyage. Technological advancements revolutionized ship construction and led to an exponential increase in the power and efficiency of marine engines.

One of the first four Black Ball Line packets, the Amity, constructed in 1816, measured 106 feet in length, with a beam of 28 feet, and drew 14 feet of water (the depth of its hull below the waterline). The Amity carried 382 tons of cargo, a crucial measurement that determined the profitability of a ship, since the more tonnage that was carried, the greater the profit. By the end of the packet era, the Black Ball’s Amazon measured 216 feet, almost exactly twice the length of the Amity. In comparison, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the great transatlantic passenger ships would reach over 1,000 feet in length. The steamship revolution completely changed the requirements for a modern port’s maritime facilities, especially the need for much longer piers.

The Cunard Line provides a model for this revolution in ship technology. Samuel Cunard began his line running wooden-hulled, side-wheel paddle steamboats like the Britannia, which measured 207 feet in length, with a beam of 34 feet. The ship’s steam engine produced 740 horsepower and averaged a speed of 8.5 knots.17 The massive engine took up a great deal of space below deck, as did the coal bunkers. Cunard’s first iron-hulled steamship, the Persia, built in 1855, measured 370 feet, 163 feet longer than the Britannia. Its steam engine delivered much more power—4,000 horsepower—at an average speed of 13.8 knots. In 1862, the China, at 335 feet long, included a key technological improvement: the elimination of the side-wheel paddles and the substitution of a screw propeller. The propeller drastically increased efficiency, thus consuming less coal, at a significant savings in operating costs.

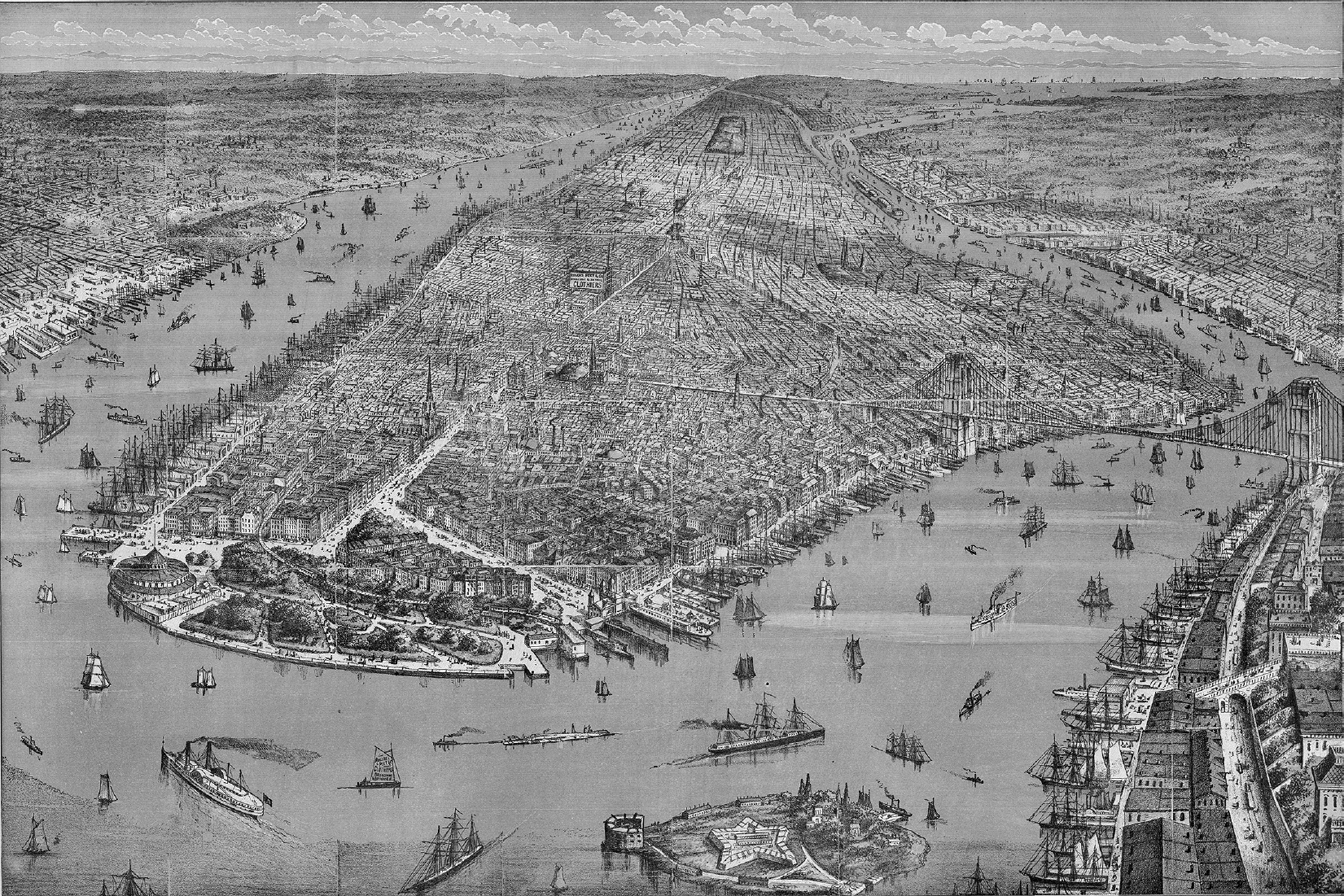

Technological innovations accelerated after 1881, when Cunard launched its first steel-hulled ship, the Servia. This new ship measured 545 feet long and averaged 16.7 knots. She was capable of crossing the North Atlantic in under eight days, given the right weather conditions. In 1893, the Cunard line built twin ships, the Campania (fig. 6.2) and the Lucania, both 625 feet long. They represented the height of luxury and confirmed Britain’s domination of transatlantic passenger service. The Campania’s twin steam engines produced 26,000 horsepower and drove the ship at an average speed of 22 knots. In May 1893, the Campania set a new record for crossing the North Atlantic westward: 5 days and 21 hours. Now a passenger or a shipping company could depend on scheduled service between England and New York in six days! In half a century, this revolution in ship construction changed the nature of Atlantic travel from crossing a hazardous, 3,000-mile ocean barrier in about forty days to a routine passage of a few days.

Figure 6.2. The Cunard Line steamship Campania, 1893. This new steamship was 625 feet long, three times the length of the Black Ball Line packet Isaac Webb. The new generation of ships required much longer piers, which the Department of Docks had to build at great expense. Source: Heritage Ships

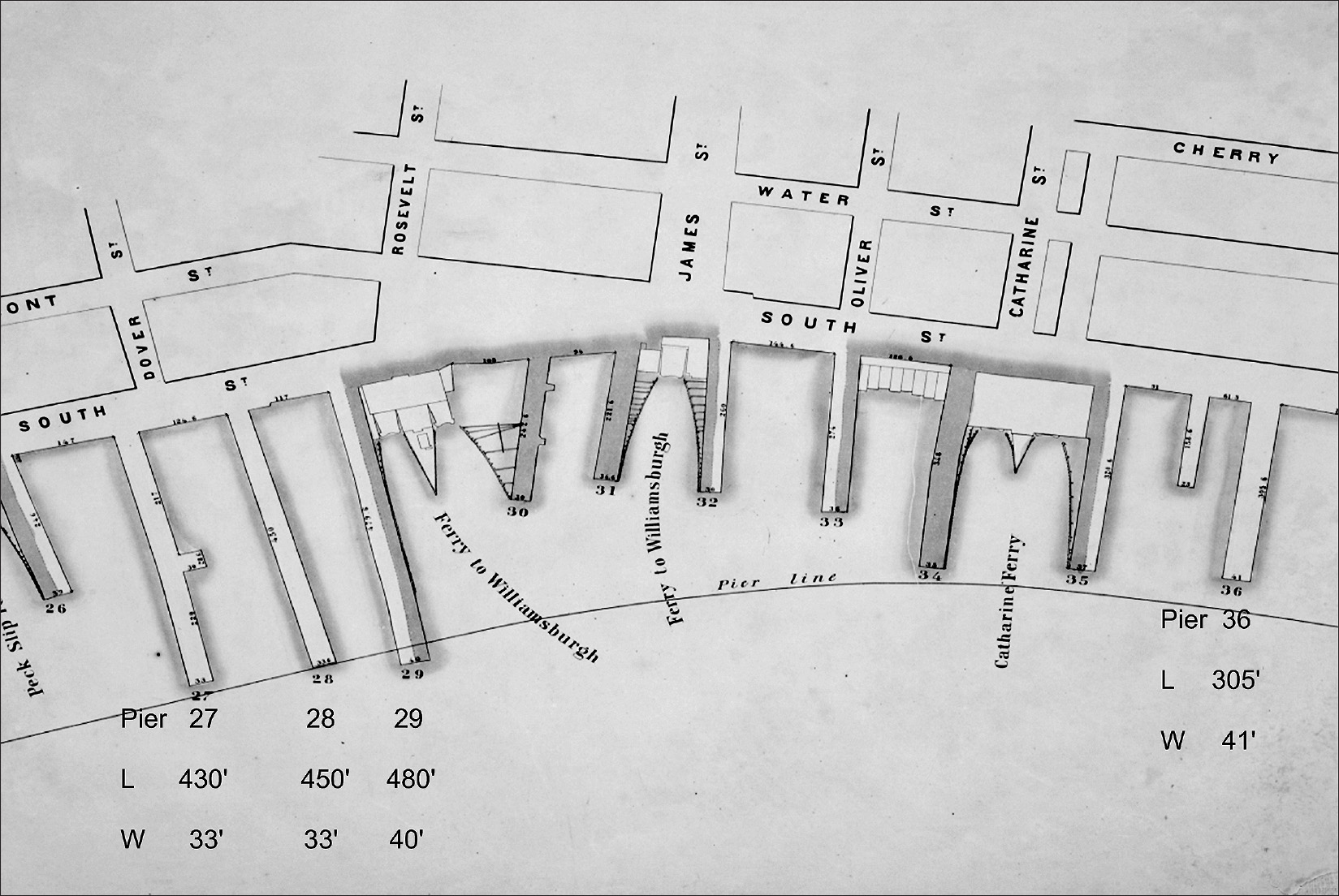

Steamships the size of the Campania could not find long-enough piers on the East River, which had been the heart of the city’s maritime world since the Dutch arrived. The Hudson River shoreline provided the only place where piers of sufficient length could be built to accommodate vessels as large as the new Cunard liners.18 The increased size of the ships, however, was not the only challenge the Port of New York faced. The quasi-private, quasi-public system on the waterfront, which began in the 1600s with the first water-lots, had created a hodgepodge infrastructure. Piers differed in length and width, and most did not include sheds or other structures to provide shelter for passengers and cargo. Few owners kept the river bottom dredged to the depth needed for heavier ships, or their wharves and piers in good repair.

The city and state of New York exercised little regulatory power. The city’s water-lot grants had transferred the responsibility for the port’s infrastructure to private owners. No single entity exercised control over the Manhattan waterfront, the surrounding waters, or the port as a whole. A New York Times editorial in 1857 emphasized the city’s need for an efficient, functioning harbor, since “upon this commerce the prosperity of our metropolis and all of the adjacent country depends.”19 As the foreign-based steamship lines arrived, they competed for space on the waterfront with coastal packets, Albany and Long Island Sound steamers, Erie Canal boats, ferries, and the powerful railroads.

Figure 6.3. South Street, on the East River, looking south from the Brooklyn Bridge toward the Battery. The bowsprits of the packet ships reached across the congested street. Counting-houses and warehouses crowded the adjacent streets in 1825. Source: Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Along the East River, the piers had been of adequate length to serve the first generation of packet ships. Vessels like the Amity would tie up to a pier with their bowsprits extending over South Street, pointing to the counting-houses across the street (fig. 6.3). While South Street provided illustrators and marine artists with romantic images of sailing ships and a waterfront atmosphere, the crowded piers and streets, with cargo strewn all over, symbolized the inefficiency and obsolescence of the East River waterfront.

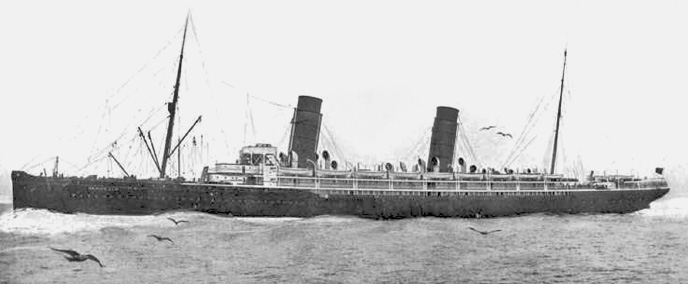

The piers along South Street, constructed by the water-lot grantees, varied in length and width. Piers 27, 28, and 29 all extended over 400 feet out into the East River and measured between 33 and 40 feet in width (map 6.2). By comparison, Pier 36, at a length of 305 feet, could accommodate ships measuring only less than 300 feet, not the Cunard’s longer liners, such as the Persia (370 feet) or the China (335 feet). The new generation of passenger and freight steamships had no choice but to move to facilities on the Hudson River.

Map 6.2. The East River piers, 1860. Prior to their takeover by the Department of Docks, the piers along the East River were a hodgepodge of different lengths and widths. Few had sheds to store cargo, and their private owners did not properly maintain the piers or keep the waterways dredged. On the map, the length (L) and width (W) of the piers is given in feet. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic pier map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

The question of extending piers of the necessary length out into the Hudson, in order to accommodate the new ships, created controversy. In 1837, the State of New York established virtual pier lines around Manhattan, beyond which piers could not be built (see the line on map 6.2). A number of the East River piers, already extending to the pier line, could not be lengthened farther. With no room to build longer piers along the East River, the shipping industry turned to the Hudson River, and the center of the maritime industry shifted to the West Side of Manhattan Island. The state’s pier lines on the Hudson, however, still did not allow for piers long enough to secure the transatlantic steamships, often 800 or 900 feet long.

Development along the Hudson shorefront followed the same pattern as on the East River: a haphazard, unplanned combination of private water-lots and pier construction, which created a jumble of private and city-owned wharves and piers. The Times editorial did not exaggerate, as the chaos along the shore did threaten the maritime commerce of the city and the entire port, since shipping companies and the European steamship lines had alternatives. They could move their facilities across the Hudson River to New Jersey, where Jersey City and Hoboken waited with open arms. To add to the threat, the cities of Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia never ceased their efforts to persuade, cajole, or bribe, if necessary, the maritime companies to relocate from the Port of New York.

Maintenance was neglected along both of Manhattan’s shorelines. Piers literally fell apart, and the slip space between piers, silted up with debris and sewage, was not dredged. Venal harbor- and dockmasters, appointed by the state to manage the waterfront, demanded bribes to obtain dock space, and criminal gangs stole freight at all hours of the day and night. Chaos reigned. A New York Times editorial proclaimed: “Abuses of every kind exist in this harbor, whose aggregate is imposing a heavy tax upon all ships and merchandise seeking this port. Prominent among them are the abuses connected with the piers and docks of the City.”20 The Times warned that without sheds and warehouses, cargo left on the open piers is “exposed to the depredation of thieves and pirates who swarm like locusts,” stealing over $1 million of merchandise a year.

An article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine described the heroic efforts of the New York City Harbor Police to battle the “dock rats”: gangs of young thieves who lived under the piers and preyed on the maritime commerce.21 Junk shops on South and West Streets fenced these stolen goods. Organized gangs smuggled goods from ships at night, to evade import taxes. With few officers and only one steam-powered patrol boat, the police were waging a losing battle to control crime on the waterfront, a struggle that continues to the present day.22

City merchants, foreign shipping interests, owners of coastal packet lines, captains of small schooners, and ferry companies complained and demanded change. To add insult to injury, the railroads now controlled a huge part of the waterfront. The 1857 editorial in the Times captured this anger and frustration: “Lawlessness and Filth reign supreme on our wharves and every cargo landed on the foul and dilapidated piers which fringe the East and North [Hudson] Rivers is more or less injured by these causes. The slime of the City sewers and the wash of ever-filthy streets of New York and Brooklyn is deposited in every dock shoaling the water.”23 By the mid-1850s, New York City’s merchants, shipping companies, mariners, politicians, civic leaders, and press all realized that the increased crowding, chaos, and deterioration along the Manhattan waterfront posed a dire threat to the very source of the city’s wealth.

Eventually the politicians in New York City and the New York State Legislature could no longer ignore these myriad problems. In 1855, the legislature passed an act “for the appointment of a commission for the preservation of the harbor of New York from encroachment and to prevent obstructions to the necessary navigation thereof.”24 The powerful New York Chamber of Commerce, whose members included the prominent merchants and shipping companies in the city, supported the commission. The ever-corrupt Democratic Tammany machine, which benefited from the chaos, corruption, and status quo on the waterfront, resisted.

The act directed the commissioners to recommend new regulations limiting the construction of piers farther out into the rivers, and the commissioners also devoted a great deal of energy to the problems on the shoreline: the piers, wharves, and bulkheads. Over the next two years, the commissioners took testimony from forty-seven witnesses, including private pier owners, wharfingers (individuals who managed piers either for private owners or the city of New York), harbormasters, merchants, shipowners, and longshoremen.

The commissioners pinpointed the central problem: the incredibly complicated division of ownership and responsibility along the Manhattan shoreline. They traced the problem back to the system of water-lot grants that transferred ownership of this real estate from the city of New York to private individuals. Although the water-lot grants required private owners to build and maintain their bulkheads and piers, the city had little real power to ensure that the piers were properly constructed and maintained. No single city department had direct oversight of the waterfront, and the absence of governmental responsibility and enforcement led to the crisis: “[Regarding] the enforcement of the laws for the government of the harbor . . . under the present system, this duty, in the City of New York, is committed to the superintendent of wharves and slips, to the harbor and dock masters, and to the police and is performed by none. The wharves remain uncleaned. . . . They are in bad repair. . . . In short every regulation which has been established, whether for the preservation of the harbor, or for the protection of the merchant or the wharf owner, is disregarded, and remains a dead letter, from the absence of a supervisory and controlling power.”25

S. A. Frost, a wharfinger for twenty-four years, managed a number of piers for private owners: Piers 16, 17, and one-half of 18 on the East River, plus 447 feet of bulkhead. Frost testified that the piers cost $93,606 to build and that wharf fees, all from transient ships, totaled about $11,000 a year. After costs of $2,794, this generated a net return of 8.8 percent.26 The private owners of the piers persistently complained that the then current fees did not generate an adequate return and continuously lobbied the state to raise them significantly, but the commissioners’ final recommendations did not include an increase. On the contrary, they compared the port fees in New York with those in Baltimore, Boston, and Philadelphia and found that these were higher in the latter three cities. Raising its fees would undercut the Port of New York’s cost advantage.

Other testimony documented the deplorable condition of the piers and bulkheads, including some that had simply collapsed into the water. Few piers had covered pier sheds. Cargo, once unloaded, if not carted away immediately, simply sat on the docks in all weather, causing significant damage to it. Filth of all sorts accumulated between the piers, requiring repeated dredging that the private owners delayed as long as possible. Isaac Orr, who was engaged in dredging operations in New York Harbor, reported that the average accumulation of deposits of filth and garbage in the slips on the Hudson River to be 5 feet every three years, and along the East River, “about a foot per annum.”27 Wharfinger S. A. Frost added that the filth required dredging every two years, because of deposits, “principally from the sewers and the wash of the streets. Another cause is from dumping rubbish from houses and factories into the slips, at night. Rubbish is also thrown in from vessels.”28 Frost also testified that the harbormasters, who assigned arriving ships to an open dock, demanded bribes to let them dock quickly:

Q. Do you know if unauthorized charges are made by public officials for obtaining berths?

A. I have frequently had complaints from captains of vessels of such charges being made. . . .

Q. Is the practice you refer to well known and notorious?

A. It is.29

The commissioners’ report documented the corruption surrounding the harbormasters and led to further investigation. In 1862, the New York State Senate established a committee to “examine into the affairs, and investigate the charges of malfeasance in office of the harbor masters of New York.”30 Witnesses called to testify suffered from what the commissioners termed “know-nothing-ism” and refused to provide details about the bribery on the waterfront. Other testimony focused on theft and crime. All of the piers hired night watchmen, but the thieves often outsmarted them, threatened violence, or offered sufficient bribes for the watchmen to look the other way. Shipping interests in the port faced not only deteriorating piers, overcrowding, and delays, but they also had to deal with serious corruption and crime.

The 1857 commissioners’ report pointed to the dramatic differences between the ports of New York, Liverpool, and London regarding the costs associated with creating the facilities necessary to accommodate the world’s shipping. In both London and Liverpool, the local governments invested a fortune to build wet basins along the shore. In London, the Thames River waterfront could not accommodate large docks, so, at great expense, excavations were carried out to create wet basins and then build docks and warehouses to enclose each basin with “massive walls of hewn stone, and fitted with every appliance for the protection and speedy lading [loading] and discharge of cargo . . . [that] comprise one thousand seventy-one acres varying for sixteen to twenty-five feet in depth, and costing sixty-five millions of dollars.”31 In Liverpool, the government constructed 174 wet basins, creating 14 miles of enclosed wharves at an estimated cost of more than $200 million, the equivalent of $6 billion today.

By comparison, in 1857 the city of New York owned eighteen piers on the East River and twenty-six along the Hudson, whose construction costs amounted to just over $1.8 million, a small fraction of the amount incurred by Liverpool and London.32 Along the Manhattan shoreline, a bulkhead at the high-water line and relatively simple wooden piers built out into the rivers sufficed. New York Harbor’s unparalleled topography allowed the construction of a maritime infrastructure at minimum expense. The private water-lot grantees had invested as little as possible and earned handsome returns. Collectively, they saw little reason to increase their investment.

The commissioners considered a number of reform proposals, including raising wharf fees and adding a duty on the landed cargo, to provide additional income to be used to repair and, in some cases, rebuild the piers entirely. After two years of work, the commission decided to not recommend raising fees for the use of the piers, since the threat of shipping companies moving to Boston, Philadelphia, or across the Hudson River to New Jersey loomed. Adding a duty on incoming cargo, to be paid by the merchants, also generated strong opposition.

Instead, the commission focused on the lack of clear responsibility for overall management of the port and the waterfront. To solve this problem, the report recommended that New York State establish a “board of commissioners with exclusive powers over the harbor within the jurisdiction of this State.”33 Three commissioners would be appointed by the governor and the New York State Senate, and the mayors of New York City and Brooklyn would serve as two additional commissioners. The clear intent of this recommendation was to replace the private/public sharing of power over Manhattan’s waterfront, going back more than 200 years, with an authority responsible to the state government, not to the city of New York alone.

To no one’s surprise, the mayor, the Common Council, and Tammany Hall opposed any plan to shift local control to the state, despite the seriousness of the existing problems and the threat that maritime commerce would leave the port. An overall authority for the port, independent of the seemingly intractable political corruption in the city, would have to wait another sixty-four years, until the formation of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey in 1921. In the short run, no serious efforts to improve the port facilities followed after the commissioners released their report. If anything, the waterfront became more crowded and, at the same time, more dilapidated in the decade before the Civil War.

Reform in the Port of New York was further delayed by the Civil War. In 1867, the commissioners of the Sinking Fund undertook a major study of the city-owned piers. This fund was established in 1817 by New York City’s new charter, in order to manage the city’s indebtedness. To avoid political corruption, the fund used dedicated revenues to pay the city’s outstanding bonds and ensure its creditworthiness. Fees from water-lot leases went directly to the Sinking Fund, and the commissioners supervised the city-owned piers and bulkheads.

The Sinking Fund’s commissioners completed a detailed study of “the conditions of the wharves, piers, and slips belonging to the city,” including estimates of their present value, the amount required to rebuild them, and their value when repaired.34 City engineers surveyed every city pier and adjoining bulkhead. For each, they included a detailed drawing of both the pier and the bulkhead, with their dimensions and the depth at low water. This exhaustive two-volume study represents the first time any civic body had compiled a detailed mapping of sections of the Manhattan waterfront’s infrastructure.

For example, on the Hudson waterfront, Pier 33, at Jay Street, was 523 feet in length and stretched beyond the pier line established by the state as the outer boundary for any pier along the Hudson River. The report described this pier as being in “poor condition.” An extension on the right side needed to be removed. At the outer end of the pier, the 21-foot depth at low water could accommodate large ships, but along the pier the depths reached only 9 feet, which required dredging. West Street had no water at low tide, so even the smallest ships or barges could not tie up to the bulkhead. The report estimated the then current value of the Jay Street pier at just $50,000, given its dilapidated condition, and it required $25,000 in repairs, including dredging. Once repaired, the pier’s value would increase to $125,000, and the city would have a functioning 500-foot pier to accommodate larger ships using the port. On the East River, Pier 29, at the foot of Roosevelt Street, adjacent to the Williamsburg Ferry terminal (see map 6.2), needed to be completely rebuilt. The outer section of the pier had collapsed into the river and could not be used. The deplorable condition of this city-owned pier mirrored the condition of most of the piers and bulkheads along the Manhattan shorefront.

The estimated cost to repair and rebuild just the city-owned piers totaled $1,119,685. To extend all the piers out to the pier line added another $791,550, for an overall total of $1,911,235. When repaired and extended, the value of the piers and bulkheads would increase to over $20 million from their then current $15 million.35 The city, however, faced a daunting problem: how to finance the needed work. In 1867, the entire budget for the city of New York totaled $5 million.36 The estimated amount required for rebuilding the waterfront would be the equivalent of 38 percent of all spending in 1867. In the context of New York City’s 2016 budget of $75 billion, 38 percent amounts to $28 billion. Moreover, the cost estimates did not include upgrading the hundreds of private piers and bulkheads. Where would the city and the private owners find such staggering sums?

If the thousands of Erie Canal boats could not find space in New York’s harbor, the Boston & Albany Railroad stood ready to load the bounty of the Midwest onto freight cars in Albany and deliver it to the port of Boston. Across the Hudson River, only a short ferry ride away, Jersey City and Hoboken eagerly waited for the transatlantic steamship companies to relocate to their piers. (In the 1860s, the Cunard Line did move to Jersey City for a brief period of time.) The Pennsylvania Railroad threatened to divert its huge freight traffic from New York to Philadelphia if the transatlantic and coastal shipping companies moved their operations to the latter city’s piers on the Delaware River.

The 250-year evolution of the hybrid system of private/public control of the waterfront on Manhattan Island had failed to keep pace with the inconceivable growth of the Port of New York and its maritime industry. A solution had to be found, or the dominance of the port and the economic vitality of New York City and the entire port region would be at risk.