Slowly, and with great effort, New York City recovered from the collapse, abandonment, and despair of the 1970s and 1980s, although the legacy of that period proved to be daunting. The crumbling maritime infrastructure along the Hudson and East Rivers would never be rehabilitated. Commercial use of the waterfront would never return. Newark Bay now served as the heart of the Port of New York, where the Port Authority had built one of the most modern container facilities in the world. The empty piers from another century, where generations of longshoremen labored, seemed to have no value whatsoever. No longer would freight from all over the world, cotton from the American South, or coal and iron ore from Pennsylvania cross from water to land. On the adjacent blocks, hundreds of factories and warehouses stood abandoned. Yet the Manhattan waterfront still remained. The death of New York City’s maritime world provided an opportunity for rebirth: to reimagine a waterfront that offered views of the Upper Bay and rivers surrounding the island, paths on which to walk and run, and an array of parkland to enjoy.

Once again, the question of public versus private enterprise and control took center stage. Would the rebirth of the Manhattan waterfront be directed and funded by the city of New York, or would the city turn to private ownership and capital to revitalize the shoreline? New York City’s history provides a precedent for both courses of action. From 1686 until 1870, the city ceded control of the waterfront to private interests, who constructed and maintained facilities to serve the city’s maritime commerce. When private enterprise failed to keep pace with both the flood of ships in the harbor and technological changes in the industry, the Department of Docks repurchased the waterfront and ran the port as a public enterprise.

A third alternative also existed, however: a public authority. Public authorities are institutions created by state governments. They exercise delegated political power and are run by appointed—not elected—executives. Many authorities have the legal right to issue tax-exempt bonds to finance projects and then keep the revenues that the bridges, tunnels, and airports generate. If the facilities generate a “profit” beyond expenses, then the authority has funding that can be used for new projects. An authority and its appointed board decide which developments to proceed with, and then obtain formal approval from elected officials.

Public authorities carry out crucial governmental functions. On the one hand, these entities act as local governments; on the other, they stand apart from the political system that created them, often wielding immense power without direct oversight or control. In New York State, there were 33 authorities in 1956, and 640 in 2004, ranging from the mighty Port Authority of New York and New Jersey to the Tuckahoe Parking Authority in suburban Westchester County.1 Public authorities built highways, bridges, and new infrastructure in the New York metropolitan region. Robert Moses used public authorities to become a preeminent power broker, shaping the future of New York City and the entire region.2 Moses never won an election, yet numerous governors of the state and mayors of New York City feared his power and seldom opposed his plans.

By the 1970s, the port and region’s first authority, the Port Authority, played an oversized role in the metropolitan region, but by then it was not alone. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, and myriad other large and small authorities have financed, built, maintained, and managed major components of the region’s crucial transportation infrastructure. For the rebirth of the waterfront, elected officials and private-interest groups at both the state and local levels turned to public authorities. Just as it had done in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the city of New York again surrendered public control of an incredibly valuable resource: the waterfront surrounding Manhattan Island.

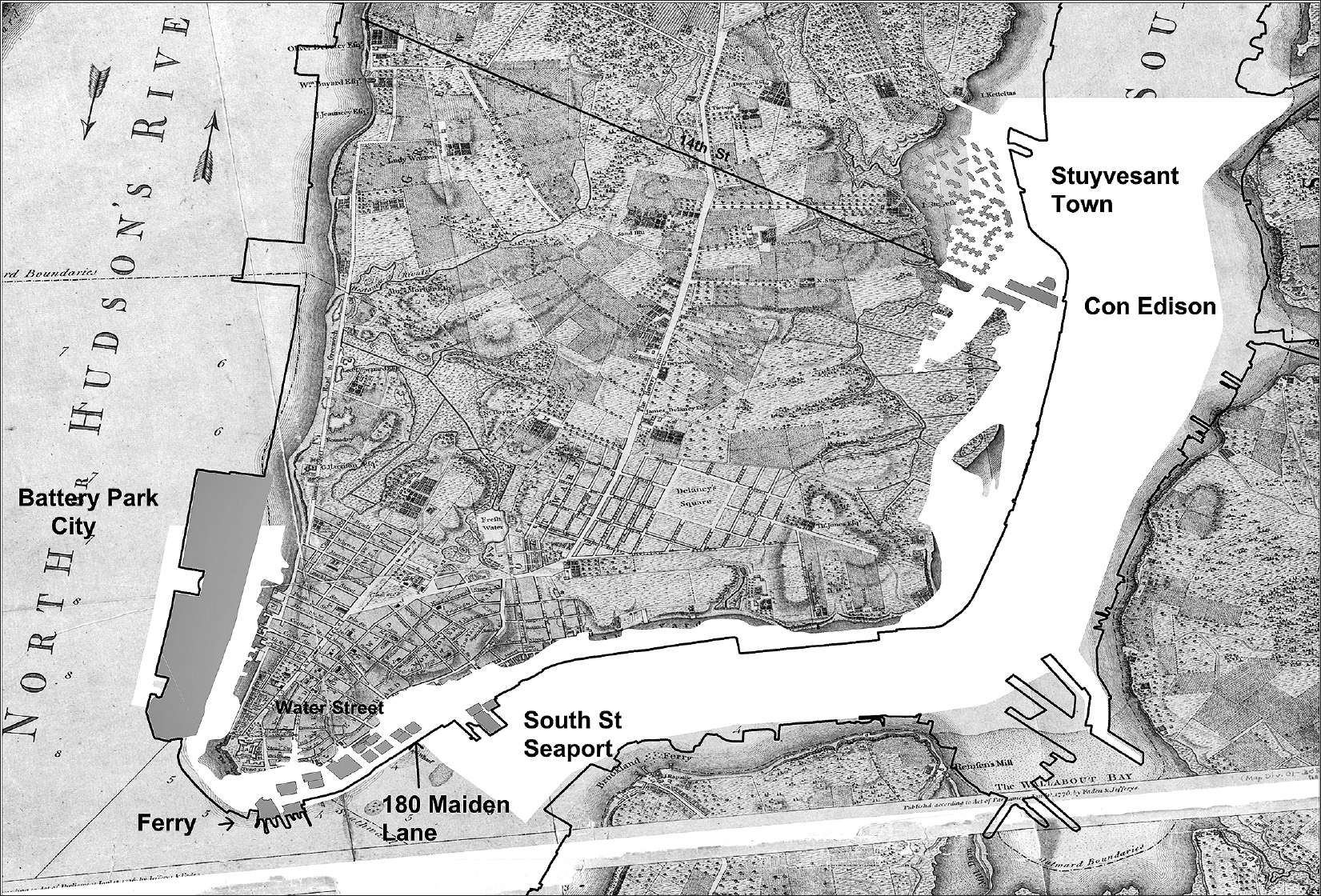

Redevelopment of the Manhattan waterfront began with plans to build new commercial space and housing at the southern tip of the island. Piers on the Hudson River, all the way from the Battery to Reade Street, no longer served either the shipping companies or the railroads and fell into disuse. In the early 1960s, two massive renewal projects began, which changed the waterfront in Lower Manhattan: the World Trade Center and Battery Park City. Neither the city, nor the State of New York, nor private developers built the Trade Center and Battery Park City; public authorities constructed both.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, a public authority created in 1921 to improve the railroad infrastructure serving New York Harbor, announced plans for the World Trade Center in 1961. How a public authority, created to solve the transportation problems in the port, could go into the commercial real estate business in Lower Manhattan is a complicated tale.3 Plans for the Trade Center’s twin office towers included 10 million square feet of office space. At the time, no private real estate developer would undertake such a massive project. Real estate interests complained that with a surplus of vacant commercial space in Lower Manhattan, they would never be able to compete with the tax-subsidized Trade Center. They also predicted that the Port Authority would never be able to lease all of the space.

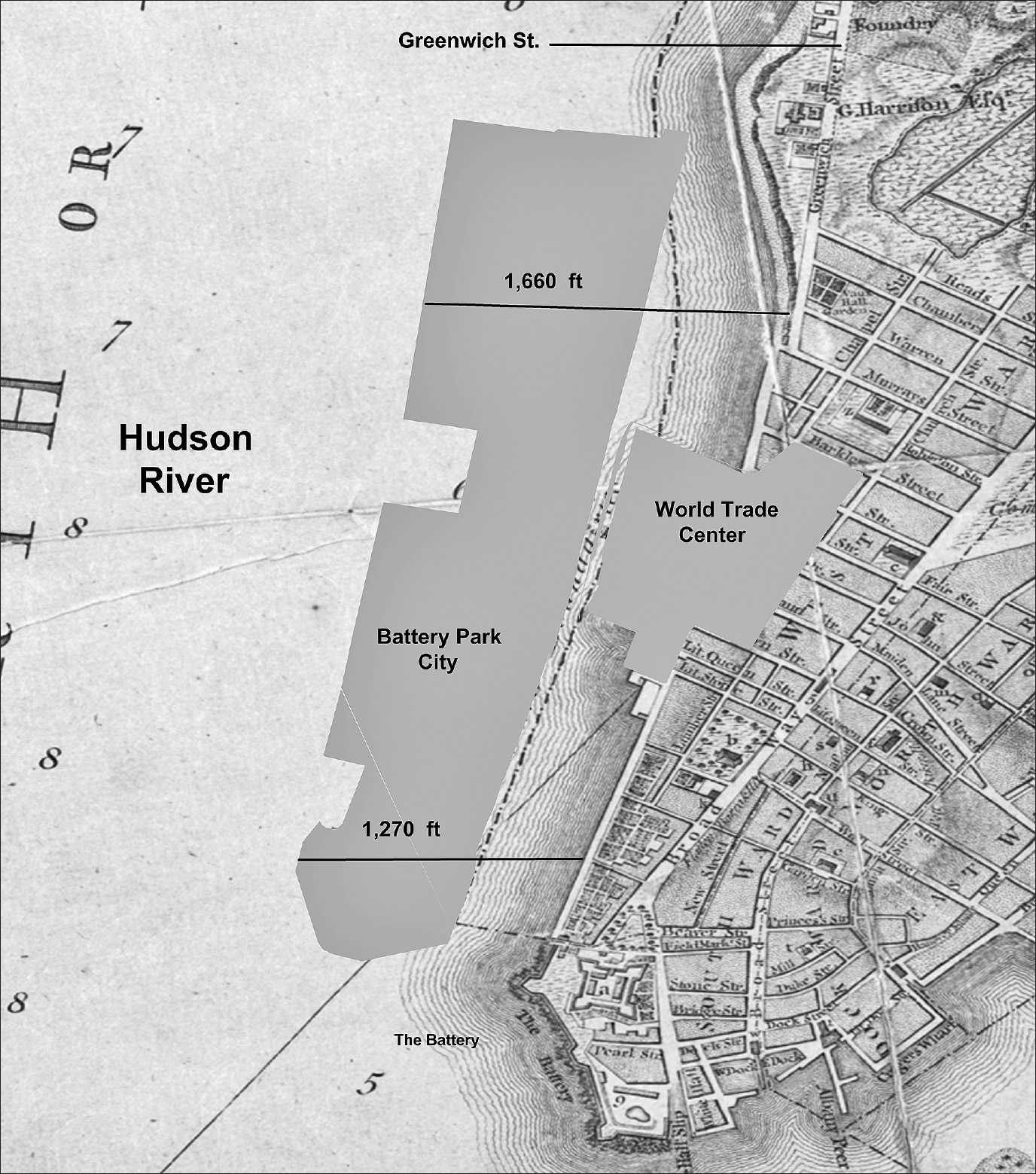

Excavation for the World Trade Center commenced in 1966, to the west of Greenwich Street between Cortlandt and Vesey Streets, on made-land created by water-lot grants, some of which were awarded before the Revolutionary War. Building the foundations for the twin towers required the excavation of 1,200,000 cubic yards of fill from that made-land along the Hudson River, posing a challenge: what was to be done with it? Excavated material could be hauled away, but at great expense. Since the adjoining piers on the river had been abandoned, a solution was readily at hand: create a massive new water-lot where the piers once stood. The 96 acres of new land—1 mile long and extending 900 feet out into the Hudson River—became the site for Battery Park City. The project created the largest single parcel of made-land in the city’s history. This new water-lot culminated a process of expanding the island out into the surrounding waterways, one that began in 1686. In 1776, Greenwich Street fronted the shoreline. The waterfront edge of the Battery Park landfill is one-third of a mile farther out into the Hudson River, at Reade Street (map 9.1). Plans for Battery Park City envisioned a new community, located where railroad freight and ships from all over the world had once arrived (fig. 9.1).

Map 9.1. A 1776 map of the Hudson River and Lower Manhattan, with the footprints of Battery Park City and the World Trade Center superimposed. Battery Park City stands on the largest water-lot in Manhattan’s history. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layers: 1776 Ratzer map, New York Public Library, Map Warper; city lots for Battery Park City and the World Trade Center, New York City Planning Department.

Battery Park City includes upscale residential and commercial developments, built not by a private real estate company, but by a new public authority, the Battery Park City Authority (BPCA). The origin of this plan began in 1961 with David Rockefeller, who was the president of the Chase Manhattan Bank, the chairman of the Downtown Lower Manhattan Association (DLMA), and the brother of Nelson Rockefeller, the governor of New York. Concerned with the decline of the Wall Street business area and the rise of Midtown Manhattan as the center of the city’s commercial activity, the DLMA and the Rockefellers supported the Port Authority’s plans for the World Trade Center and the Battery Park City landfill. The DLMA argued that any downtown revitalization efforts must include housing, a departure from focusing on new office space.

Figure 9.1. The Battery Park City water-lot. Almost all of the piers from the Battery to Jay Street were not in use. Therefore, rather than load the excavated material from the foundations for the World Trade Center onto barges and then tow it to a distant landfill, the Port Authority created an enormous landfill in the Hudson River, adjacent to the twin towers. This new water-lot totaled over 90 acres. Source: Battery Park City Authority

Numerous problems in financing the massive project arose, and the first apartments were not completed until 1980. Battery Park City’s combination of offices, upscale housing, stores, and venues for leisure activities became a blueprint for the “new urbanism” of the 1980s, encouraging high-density redevelopment in cities as an antidote to suburban sprawl.4 Aaron Shkuda points to Battery Park City as an exemplar of that trend and of the evolution of New York City’s service economy, since “these residences were to serve as a company town for Wall Street, a new form of housing that would appeal to employees and keep them close to the office around the clock . . . as the New York economy was transforming to a post-industrial service system prior to the exponential growth of Wall Street after deregulation in the 1980s.”5

This new housing would be for the affluent, however, not the poor. In the 1930s, with the abandonment of the East River shipyards from Corlears Hook to 14th Street, the city of New York built thousands of subsidized apartments for the working class and the poor along the East River. Manhattan’s new waterfront renewal, despite pledges to the contrary, now includes only expensive condominiums and apartments and little in the way of affordable housing. The rebirth of the waterfront would serve multiple uses—for commercial space, housing, parkland, and recreation—but these would be mainly for the affluent in a post-industrial economy.

Figure 9.2. The Battery Park esplanade and the Hudson River shoreline. Battery Park City includes a park, which is open to the public, along the newly created waterfront from the Battery to Jay Street. Battery Park serves as the southern anchor for the stunningly successful Hudson River Park. Source: Battery Park City Authority

Battery Park City today is home to over 13,000 residents, and 36 acres of the development remain as open space. The market-rate rent for two-bedroom apartments here ranges from $5,600 to over $10,000 a month. The StreetEasy website lists a number of two-bedroom condominiums for sale, at over $2 million each.6 The most recent census data estimates that the average household income for Battery Park City residents is $316,718, far above Manhattan’s average of $132,839.7 A key part of the plan for this area included an esplanade and marina on the Hudson River, creating a shoreline park for the public (fig. 9.2), maintained by the BPCA with revenue generated by its real estate developments. This park, designed for public use, was paid for and controlled by a public/private authority, not by the city of New York.

In 1992, the city of New York published a new waterfront blueprint, officially recognizing the transformation that was taking place. Mayor David Dinkins had directed the New York Department of City Planning to undertake a major study of the waterfront—not for Manhattan alone, but for the city’s entire 578-mile shoreline. The long-range plan trumpeted that it “balances the needs of environmentally sensitive areas and the working port with opportunities for waterside public access, open space, housing, and commercial activity.”8 To deal with multiple constituencies spread throughout the metropolitan area’s five boroughs, the plan included commercial activity, along with increased public access and the federally required preservation of the natural environment. During the previous three centuries, the public had had little access to the water, and hardly any open space could be found along the lower Manhattan waterfront.

The 1992 plan envisioned a twenty-first century waterfront. It identified a number of priorities, with the first three focused on the natural environment. Maritime activity was relegated to fourth place. New York City’s waterfront would become a place where

• parks and open spaces, with a lively mix of activities, are within easy reach of communities throughout the city;

• people once again swim, fish, and boat in clean waters;

• natural habitats are restored and well cared for; and

• maritime and other industries, though reduced in size from their heyday, thrive in locations with adequate infrastructure support.9

For the first time in New York City’s history, an official plan acknowledged the stunning decline of the maritime world that once drove the city’s economy. A priority for the new waterfront was to set goals for the use of the shoreline as parkland, both for recreation and for some restoration of the natural environment. While the shore that Henry Hudson viewed in 1609 could never be restored, every effort would be made to mitigate hundreds of years of maritime exploitation of the waters surrounding Manhattan Island. Conspicuous by their absence, however, were details of how this restoration would be financed.

The plan’s focus on restoration followed in the footsteps of a truly remarkable environmental victory: the defeat of Westway, a federally financed highway project along the Hudson River.10 A high-powered coalition of politicians, labor unions, construction companies, and real estate moguls had used their collective political power to push through plans to replace the crumbling West Side Highway with a new superhighway. It would be built out into the river, in a deep concrete cut that then would be covered over, creating acres of new waterfront to be developed. Initially, the proposal seemed to generate almost universal support from the city’s power structure. The federally funded highway, requiring no expenditure by New York City, would bring billions of dollars to a city starved for investment and create thousands of high-paying construction jobs.

An improbable coalition of political activists, the Sierra Club, and local community leaders fought tooth and nail to defeat the plan. In a climactic legal battle, the Sierra Club sued the US Army Corps of Engineers in federal court. The Corps of Engineers had to comply with the legal requirement to conduct an environmental impact study for the proposed highway, which was mandated by the national Environmental Protection Act (1970) and the Clean Water Act (1972). The Corps of Engineers’ study initially found that Westway posed no environmental risk, especially to the striped bass population in the Hudson River. The Sierra Club’s experts disagreed. In 1985, Thomas P. Griesa, chief judge of the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, ruled in favor of the Sierra Club, and Westway died. The Village Voice’s Tom Robbins, celebrating the twenty-fifth anniversary of the defeat of Westway in 2012, summed up the victory:

We never built Westway, the crazed multi-billion-dollar-city-in-the-river landfill project that Presidents, governors, and mayors desperately fought to build back in the 1980s. You don’t remember this? Count your lucky stars. It was one of the last great attempted public arm-twistings by the Permanent Government—a bid to give the ever-campaign-generous real estate industry its most coveted desire: More Manhattan land on which to build. This week marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of one of the great citizen victories of our time: The defeat of Westway. A band of creative activists, aided by attorneys dedicated to public service, and back-stopped by a thoughtful and brave federal judge managed to beat the entire power structure of the city at its own game.11

New York did find a silver lining in the project’s defeat, however, since changes to the federal highway laws allowed the city to “trade-in” the US government’s initial funding of over $1.7 billion for Westway and use it to rebuild the city’s crumbling subway system. Without the Westway dollars, the rebirth of the subway would have been delayed for decades.

The Westway fight stimulated alternative plans. One of them imagined the shoreline as public space—a place to remind people daily that Manhattan is an island, surrounded by waterways. The waterfront, no longer gritty and dangerous, would become a place where the public could enjoy magnificent views and watch the sun set over the Hudson River and the Upper Bay. For the wealthy, the waterfront could evolve into a fashionable place to live. For the stylish, it could become a place to shop, dine, and visit an art gallery or museum. Thus, despite the Westway defeat, the shorefront remained contested space. Would people from all walks of life and income be welcome on the revitalized waterfront, or would it become a place apart, for only the rich and successful to enjoy?

Battery Park City’s promenade created the southern anchor for a new waterfront park to line the Hudson River, extending from the Battery to Riverside Park and then on to Inwood Hill Park, at the northern tip of Manhattan Island. The defeat of Westway and the removal of the elevated West Side Highway presented an opportunity to build a major section of a greenway around the entire island of Manhattan.12

In 1992, Governor Mario Cuomo and Mayor David Dinkins signed an agreement to have the city and the state join in funding the new park. Six years later, Governor Pataki signed legislation to create a new public authority, the Hudson River Park Trust, to manage the building of the park. The trust would oversee day-to-day operations and be funded by revenues generated within the park, to be used only for park purposes. This new authority would be self-financed by activities in the park, including a large parking garage on Pier 40 at Houston Street. The trust, not the city’s Parks Department, would run the park, a return to the concept of private, rather than public, development. Control rested with an appointed, not elected, governing board.

Over the next two decades, the trust spent $350 million to build the riverfront park. This new parkland rests on the bulkhead constructed by the Department of Docks in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The massive granite stones that cap the bulkhead are visible in sections of the walkway on the river. It is hard to imagine that the park would have been built if a new bulkhead had to be constructed, given the cost involved. As it was, the Hudson River Park Trust, in the face of economic challenges, formed a partnership with the Friends of Hudson River Park, a nonprofit organization founded to promote the building of the park. The latter’s mission, as a fundraising partner for the trust, is to seek private philanthropic support for the completion of the park and for its continued maintenance. Neither the state nor the city of New York provides ongoing financial support or directly manages the Hudson River Park. The Parks Department, part of New York City’s government, plays a very limited role in the new 550-acre park along the Manhattan waterfront. Instead, a public authority and a private philanthropic organization rule the park, with limited oversight from elected officials at both the local and state levels.

The crucial question of public versus private control remains contentious, however. A case in point occurred when the 2007 fiscal crisis strained the trust’s budget, and the organization ran deficits, which reached $9.5 million in 2014.13 Pier 40, at Houston Street, had become a major problem for the trust. It was built for the Holland-America Line by the Department of Marine and Aviation in the late 1950s, in a last-ditch attempt to save the shipping business on the Manhattan waterfront. The pier survived, and it became part of Hudson River Park, being used for parking and as a sports facility. The Pier 40 parking garage provided the trust with a major source of revenue: $6 million a year. Inspections later found that pilings supporting the pier had deteriorated and needed to be replaced, at an estimated cost of $100 million, well beyond the fiscal resources of the trust and the Friends of Hudson River Park.

One solution was for the city of New York and the state to finance the repairs for Pier 40. The original enabling legislation specifically allows that “additional funding by the state and the city may be allocated as necessary to meet the costs of operating and maintaining the park.”14 Public funding would have come with increased public oversight, however, so instead, the trust turned to private sources of capital. In 2014, the trust quietly negotiated a deal with the Atlas Capital Group, a real estate development company, to transfer development rights from Pier 40—in essence, the air rights—to the other side of West Street, in exchange for $100 million.15 Across the street, Atlas owns the St. John’s Terminal building, built as a rail-freight terminal at the High Line’s southern end. In the 1930s, freight trains traveled down the High Line to the terminal to deliver goods to Lower Manhattan. Since the demise of the High Line as a freight line, the five-story terminal building has served as a warehouse. UPS is currently the major tenant.

Figure 9.3. Pier 40, on the Hudson River waterfront. The concrete building inland, across West Street, is St. John’s Terminal, originally the southern terminus of the High Line. Source: Axion Images

The Atlas Group manages a real estate portfolio valued at $2.5 billion and proclaims expertise in “repurposing and repositioning existing properties.”16 In exchange for the $100 million, Atlas plans to use the air rights to build high-rise luxury housing where the St. John’s Terminal currently stands (fig. 9.3). This new, multistory construction would join numerous other luxury buildings that now line the Hudson River waterfront, extending from Chelsea to Greenwich Village, SoHo, and down to Battery Park City.

Massive reconstruction on the streets adjacent to the waterfront, now filled with luxury housing and renovated brownstones, symbolizes another dramatic change in the waterfront: the Irish neighborhoods have vanished. The few remaining longshoremen work at the vast container facilities in Newark Bay. Waterfront bars have disappeared or found new life as trendy upscale places with historical pictures on the walls, a nod to a working-class past.

One of the most iconic symbols of the rebirth of the waterfront, High Line Park (often referred to simply as the High Line), is not actually on the waterfront. After thirty years of protracted legal battles, in 1929 the New York Central Railroad and the city and state reached an agreement to remove the railroad’s tracks from 10th and 11th Avenues, eliminating Death Avenue and the West Side problem. At great expense—which was shared equally by the railroad, the city, and the state—the tracks were relocated to an elevated viaduct through the middle of the city blocks from 34th Street to St. John’s Terminal. The High Line included a number of sidings running directly into warehouses and factory buildings on the waterfront (fig. 9.4).

Figure 9.4. The High Line, the New York Central Railroad on the West Side. The tracks passed through the huge Manhattan Refrigeration Company’s cold storage building on Gansevoort Street, seen in the background. The elevated railroad tracks have now been transformed into an urban park. Source: Digital collections, New York Public Library

The High Line opened in 1934, in the midst of the Great Depression and shortly after the advent of the truck and highway revolution. When the Holland Tunnel opened in 1927, hundreds of trucks used the tunnel each day to haul freight back and forth to New Jersey, eliminating the need to float freight across the Hudson River to the railroad depots on the waterfront. The New York Central’s traffic on the High Line also declined. By the 1970s, the elevated tracks were overgrown by weeds and filled with debris, a stark symbol of the decline of the railroads and the City of New York.

Against all odds, and amid calls for the city to tear down the abandoned rail line, two West Side residents, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, formed the Friends of the High Line in 1999 and set out to save the elevated tracks. This was primarily a private initiative.17 They argued that the abandoned rail line could be redeveloped as an elevated park, modeled after the Promenade plantée in Paris. To build the elevated parkland, David and Hammond raised private funds for the project, eventually amassing over $150 million. The city initially contributed $50 million, and the first section opened in 2009, to rave reviews. Today, the High Line is one of the most visited tourist attractions in New York City.

Mayor Bloomberg officiated at the opening of the second section of the High Line on June 7, 2011. He argued that the total of $115 million contributed to it by the city was a sound investment. The success of the High Line, he continued, had led to over $2 billion in private investment, pointing to “the deluxe apartment buildings whose glass walls press up against the High Line and the hundreds of art galleries, restaurants, and boutiques it overlooks.”18

The High Line is a few blocks from Hudson River Park, and the two reinforced the transformation of the neighborhoods along the shore. A crowning jewel came with the announcement by the Whitney Museum of American Art that it would relocate to a new building at the southern end of the High Line, at Gansevoort Street. Designed by architect Renzo Piano, the new museum building stands between the High Line and Hudson River Park. Visitors can now walk along the High Line from West 34th Street to Gansevoort Street, visit the Whitney Museum, and then cross to Hudson River Park for a walk to Battery Park City—a journey through a new cityscape that epitomizes the rebirth of the waterfront.

Not only did High Line Park become a popular tourist destination, but the flood of people visiting it and the numerous art galleries and restaurants in Chelsea have also furthered the gentrification of a working-class waterfront. The city’s decision to rezone the blocks inland from the Hudson River opened the former warehouses and factory buildings in Chelsea and Greenwich Village for redevelopment. Warehouses were converted into art galleries, high-end apartments, and luxury condominiums; restaurants and upscale retailers followed.

In Greenwich Village, on the streets running from Hudson Street down to the river, where generations of Irish longshoremen lived, wealthy buyers have purchased the iconic brownstone buildings. In the 1870s, these brownstones were carved up into four or five apartments each, but many have now been converted back to single-family homes. The block on Bethune Street between Washington and Greenwich Streets retains its nineteenth-century appearance, with classic brownstones lining both sides of the street. For example, 32 Bethune Street (see map 9.2), with its exterior beautifully restored, has three floors, with steps down to the basement. The current estimated market value of this Bethune Street residence is over $5 million. Only the truly wealthy can now afford a restored brownstone, located a block and a half from Hudson River Park, in an area of Greenwich Village that once was replete with tenements for impoverished immigrants.

In the late nineteenth century, when much of the shipping in the port moved to the Hudson River, Bethune Street became a working-class neighborhood, where the men toiled on the waterfront. In 1880, two families lived at 32 Bethune Street: Joseph Hayes, an Irish immigrant; and Thomas McDonald, with his wife, three young children, and an Irish maid (table 9.1). By 1900, the McDonalds and Hayes had moved on, and two new families resided there. Mary Bailey and her sister Annie both worked to support their three siblings; and James O’Toole, who came from Ireland in 1870, worked down the street as a longshoreman.

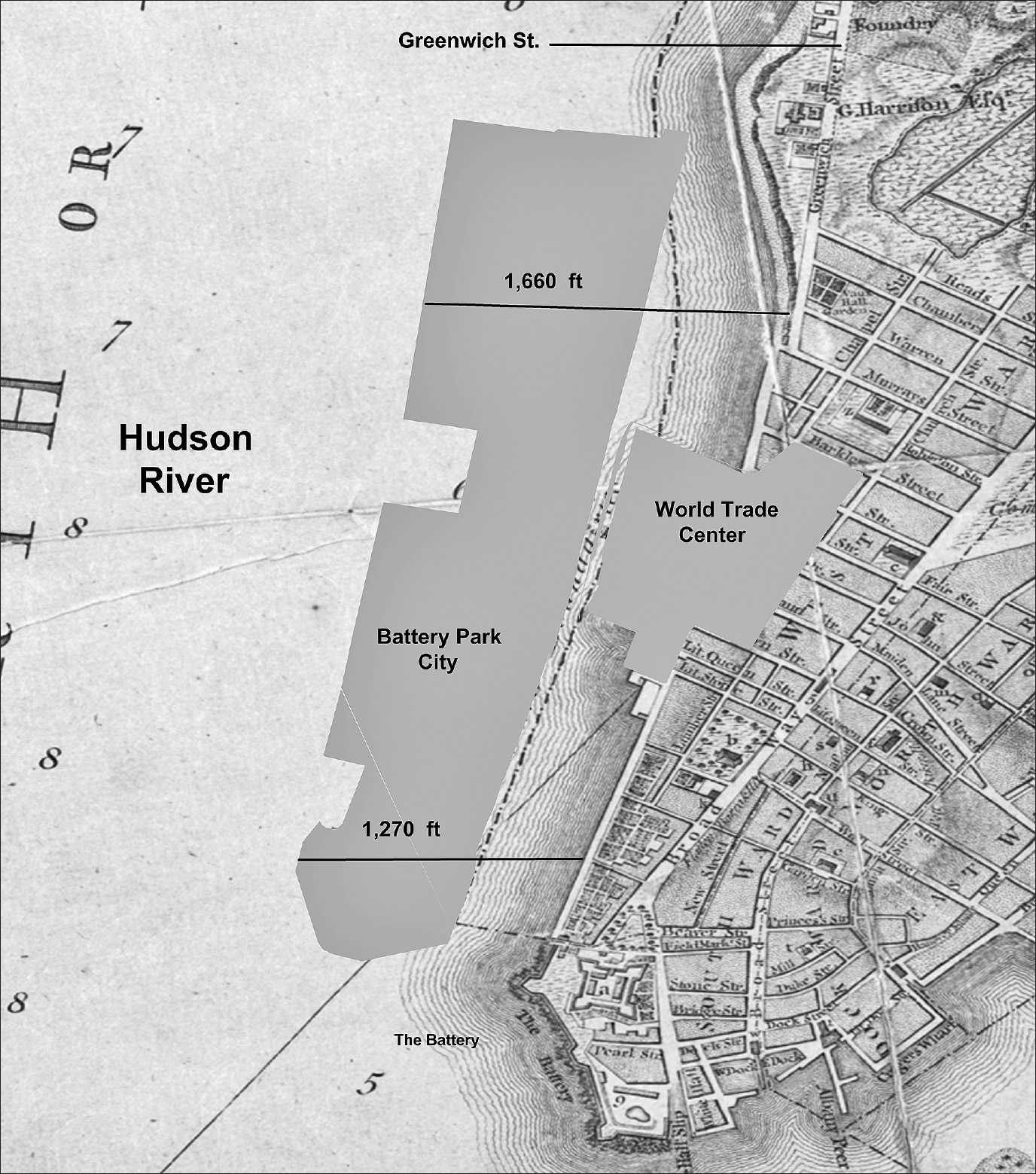

The Irish longshoremen and the working-class residents on Bethune Street are long gone, as is the close-knit surrounding neighborhood that Jane Jacobs celebrated in her classic work, The Death and Life of Great American Cities.19 On Bethune and the other Greenwich Village streets adjacent to the Hudson, the gentrification has been stunning. The eight neighborhoods (designated as census block groups) between West 14th and Canal Streets (map 9.2) are home to a population significantly wealthier, whiter, and better educated than the average city resident (table 9.2). Not surprisingly, these neighborhoods have an average household income well above the average for Manhattan.

Table 9.1.

Census data, 32 Bethune Street

Sources: “New York City, Enumeration Districts,” United States Federal Census for the years 1880, 1900, 1910, and 1920, www.ancestry.com [accessed spring 2016].

Map 9.2. Hudson River neighborhoods in Greenwich Village. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: building footprints, New York City Planning Department. Other source: census block groups, US Bureau of the Census, “2014 American Community Survey (ACS),” American Factfinder, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t/ [accessed March 10, 2016].

The Meatpacking District, the southern terminus of the High Line (map 9.2, #1), has household incomes that are more than two times the Manhattan average. The district is filled with luxury condominiums, fancy restaurants, upscale stores, and trendy bars, just as Mayor Bloomberg had envisioned. In 1992, the city’s plan for a revitalized waterfront proposed using the shoreline as a place for all to gather, but now only the rich can afford to live nearby.

Table 9.2.

Greenwich Village population, by block groups, in 2014. The block group numbers refer to the areas shown on map 9.2.

Source: US Bureau of the Census, “2014 American Community Survey (ACS),” American Factfinder, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/searchresults.xhtml?refresh=t/ [accessed March 10, 2016].

The rebirth of the waterfront has not been limited to Greenwich Village. On Manhattan’s West Side, from 38th Street in Chelsea south to the Battery, the number of people living along the shore has grown dramatically from the depths reached in the 1970s. The 1970 census reported that 8,063 people lived in this 3.7-mile section along the Hudson River. By 2014, the population had risen to 28,597, an increase of over 250 percent.20 As new apartments and condominiums are completed, and with hundreds more on the drawing boards, the number of people on the West Side waterfront will only increase. No longer do the men go down to the docks for the shape-up, as the Irish did. Rather, both the men and women living there earn high salaries in the city’s post-maritime, post-industrial economy.

The pressure by private interests to build on and develop the waterfront remains unabated. The creation of the Hudson River Park Trust as a private/public partnership proved to be a bold move to revitalize the riverfront, and the requirement that the park be self-financing defied the accepted logic of a public park. Yet with no continuing public financial support, the park had no alternative but to turn to private interests to save Pier 40. The trust, in return for the needed funds, had to trade a valuable asset: expansive views of the Hudson River.

The proposed development around Pier 40 has drawn much criticism. The Atlas Capital Group’s plans for five residential buildings include commitments to set aside a portion of the 1,500 planned new apartments as affordable housing. At a public hearing in November 2015, New York State Assembly member Deborah Glick, who represents the area, raised the issue of how “affordable” would be defined. A New York Times editorial called the project a “win-win” for the West Side of Manhattan, but it did not directly address the issue of who would have enough money to rent an apartment or buy a condominium there.21 In 2016, the average condominium in Manhattan sold for $2 million. If the ten penthouses in the proposed buildings sell for $10 million each, the trade-off is certainly a win for their private developer, who will easily cover the $100 million in pier renovations and can then profit from the remaining 1,490 apartments. Time and again in recent years, developers promise to include affordable housing, but citizens of modest means remain priced out or have to use the “poor door” in the back of the building.22

Another controversial private proposal further illustrates the contemporary battle over control of the waterfront. Following private negotiations with the Hudson River Trust in 2014, Barry Diller and his wife, Diane von Furstenberg, whose philanthropy supported the High Line, announced plans to fund the construction of a 2.4-acre island north of Pier 55, at West 13th Street.23 The proposed island park would serve as a venue for concerts and the arts. Diller and von Furstenberg pledged $113 million to privately fund the project, which immediately set off another storm of controversy. Environmental groups objected. Critics charged that the public would have to pay park entrance fees to attend performances on the new island, which would be connected to Hudson River Park, although the trust gave assurances that parts of the island would be free for all to visit, even when concerts were scheduled.

In a New York Times editorial entitled “The Billionaires’ Park,” David Callahan argues that this controversy illustrates the city’s abandonment of its responsibility to fund public spaces for all to enjoy freely. In the nineteenth century, New York City led the world by providing public parks and public institutions that served as models of civic responsibility: Central Park, Bryant Park, and the New York Public Library. Callahan claims: “Private wealth is remaking the city’s public spaces. . . . While it’s hard to argue with more parks, or the generosity of donors like Mr. Diller, this isn’t just about new patches of green. It’s more evidence of how a hollowed out public sector is losing its critical role, and how private wealth is taking the wheel and having a growing say over basic parts of American life.”24 The city of New York has abnegated its responsibility and left the rebirth of the waterfront in the hands of public authorities and private philanthropy.

Opposition to the proposed island continued, led by a small but loud group of community activists and secretly funded by Douglas Durst, a New York real estate billionaire. After two years of legal battles, with the cost estimate rising to over $250 million, Mr. Diller announced on September 13, 2017, that “Because of huge escalating costs . . . it was no longer viable for us [referring to his wife] to proceed.”25

The apparent end of the Diller island plan echoes the battle over Westway in the 1970s. New York’s power structure, including Governor Andrew Cuomo, Senator Chuck Schumer, Mayor Bill de Blasio, and the local community board all supported the plan. A New York Times editorial criticized the opponents of the plan as part of a now “familiar dynamic in New York when the well-heeled put their money behind a new idea: an assumption that something untoward is afoot, including privatization,” yet added, “Private money is not necessarily to be shunned.”26 The Times editorial does not offer guidance on how to balance the public good against private interest, an issue that has embroiled the use of the Manhattan waterfront for hundreds of years.

Private development continues unabated on the made-land along the Hudson and East Rivers, with one grandiose plan following another. Despite its high real estate prices, Manhattan’s waterfront has been transformed and made accessible. Anyone who knew New York in the 1970s could not have imagined the greenway that now almost entirely encircles Manhattan Island. Once a wasteland of abandoned piers, crumbling highways, and empty warehouses, the shoreline is today a place where millions enjoy the waterways that surround the island. A dangerous, dirty, and polluted shoreline has been reclaimed for recreation and open space.

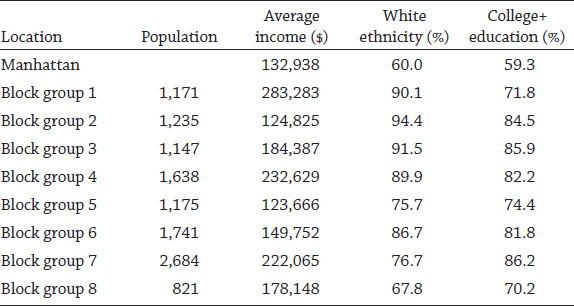

One inexorable consequence of the relentless development and redevelopment of the Manhattan waterfront over time remains: the waterfront that Henry Hudson and the early Dutch settlers saw has literally disappeared. As map 9.3 illustrates, the made-land along the Manhattan shoreline today extends out from the original shore into the Hudson and East Rivers, but it is only a few feet above sea level. Thus this redevelopment of the waterfront has ignored potential environmental challenges. As Hurricane Sandy reminded the city, the waters that surround Manhattan—once and still a source of wealth—may now, in an era of global warming, prove to be a major threat.

The flooding from Superstorm Sandy inundated Lower Manhattan, putting it under as much as 4 or 5 feet of water, resulting in billions of dollars in damages. Along both rivers, the water covered almost all of the made-land that was created by filling in water-lots over the centuries, including the largest water-lot of all: Battery Park City. In many areas of Lower Manhattan, the shoreline drawn on the 1776 Ratzer map marks the high-water line of Sandy’s flooding and coincides with the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) current flood zones.

Hurricane Sandy engendered $18 billion in damages. In New York City, forty-three people died. Water covered the open space in Battery Park City and flooded the buildings along the East River from Water Street to the river’s edge, including the ferry buildings at the Battery and the South Street Seaport. The Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel flooded, as did the subway tunnels connecting Manhattan to Brooklyn. The L line at 14th Street—between Manhattan and Williamsburg, in Brooklyn—will be closed for eighteen months, beginning in January 2019, to repair the flood damage from Sandy. Disaster also struck the Con Edison plant at 14th Street, which exploded, plunging Lower Manhattan into darkness for days without electricity. The Con Ed generating plant sits on a water-lot created in the 1830s. Moreover, half of Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village stands on the made-land, which was once Stuyvesant Cove, clearly visible on the 1776 Ratzer map.

Map 9.3. A 1776 Ratzer map of Manhattan Island, with a black line showing the modern shoreline. The shaded area represents the current FEMA flood zone. In an era of climate change, the made-land on the Manhattan waterfront remains vulnerable. Hurricane Sandy flooded the Con Edison plant on 14th Street, plunging the entire southern part of the island into darkness. On the Wall Street waterfront, hundreds of millions of dollars of commercial property sits on what was once the East River. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layers: 1776 Ratzer map, New York Public Library; shoreline, lots, and building footprint maps, New York City Planning Department; floodplain map, Federal Emergency Management Agency.

The relentless development along the rivers on water-lot land has left billions of dollars of New York City real estate vulnerable to climate change and storms of Sandy’s intensity. For example, 180 Maiden Lane, built on made-land on the East River, is one of fourteen office buildings between the Battery and Maiden Lane. It is a forty-one–story Class A building, built in 1982, that contains over 1 million square feet of office space. Hurricane Sandy flooded the basement, forcing tenants to find alternative office space for months, until the water damage was repaired. In January 2015, the building, valued at $435 a square foot, sold for $470,000,000—almost half a billion dollars for one office building on the corner of Maiden Lane and South Street.27 The new owners of 180 Maiden Lane must reckon with the risk of future storms.

The fourteen nearby buildings between the Battery and Maiden Lane total 13,657,595 square feet, and their commercial value is over $5.9 billion (at $435 a square foot). All of these buildings sit on made-land from some of the first water-lots on the East River, and all were flooded by Sandy. They stand in the FEMA flood zone for Lower Manhattan. The risk, moreover, is not limited to this one part of the Manhattan shore. It includes all of the made-land created over hundreds of years.

As New York City plans for the future, the threat of rising sea levels and violent storms is a problem that will have to be dealt with pragmatically. The question of control of the waterfront persists, and it complicates efforts to address global warming. The city, primarily through zoning and building codes, exercises only limited regulatory power over development on the waterfront. The federal government’s FEMA regulations do deal with the issue of building in a flood zone, but existing property is grandfathered in.

On the Staten Island and Long Island shorelines devastated by Hurricane Sandy, both the federal government and the state’s government have recommended buying out private owners of the most vulnerable shoreline property. If a similar approach were to be used for Manhattan property lying in the FEMA floodplain, staggering questions would arise. Where would the billions of dollars required to purchase the commercial and residential property on made-land around Manhattan come from? Where would the private businesses and luxury residential housing relocate to? Another option is to build enormous dikes and walls, as the Netherlands has done. Yet dikes around Manhattan Island would destroy access to the city’s waterfront.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the Department of City Planning published Vision 2020 in March 2011, five months before Hurricane Irene and a year and a half before Hurricane Sandy. Mayor Bloomberg’s foreword presents a clear mandate: to continue to “reclaim one of our most valuable assets—our waterfront.”28 The report hailed the work done to date and listed priorities for going forward: “These projects are part of the most sweeping transformation of an urban waterfront in American history. And as we serve as an engine of economic growth for America and the world, we will invest in initiatives that will help New Yorkers green their communities and build a more economically sustainable city. Jobs and the environment, affordable housing and open space, waterborne transportation and in-water recreation—all these priorities have informed Vision 2020’s goals for our City’s more than 550 miles of shoreline.”29

The Vision 2020 plan did not anticipate the ferocity of Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. For instance, at the Battery on the night of October 29, 2012, at the height of Sandy, the water rose 14 feet above low water—much higher than the bulkhead around Lower Manhattan—flooding the residential and business districts, with their private property on made-land. To protect the city in the future requires setting priorities to save the waterfront from rising storm waters and establishing the respective responsibilities of both the city and private-property owners.

A year after Superstorm Sandy, Mayor Bloomberg unveiled a $20 billion plan to protect New York from the next hurricanes.30 The 450-page report, A Stronger, More Resilient New York, includes detailed proposals to strengthen the shoreline of the entire city.31 The study identified the consequences of the historic expansion of the shoreline, “with areas along these coasts now lying at or near the water level. Examples of these low-lying areas include Lower Manhattan.”32 All of the valuable properties along the rivers are vulnerable, including 180 Maiden Lane, the proposed St. John’s Terminal development, and the controversial Diller–von Furstenberg island.

Among the plans considered in this report are giant storm barriers across the Narrows and the East River, to be closed when major storms approach. The model for these barriers is the massive storm gates the Dutch have built to protect their country, which lies below the level of the North Sea. Such barriers, however, would take years to be approved, cost between $20 and $25 billion, and require millions of dollars for annual maintenance. The Bloomberg plan did not recommend building the barriers, arguing instead for an “integrated flood protection system” for Manhattan Island and other vulnerable shorefronts. The integrated plan includes “deployable floodwalls,” with moveable posts and panels to be installed when storms threaten, and then to be removed after the storms pass. No cost estimates are provided, but the report identifies operating challenges: storage, heavy equipment to erect the posts and panels, a sizable workforce, and regular emergency practice drills.33 Whatever plan is eventually implemented, it will be incredibly controversial and expensive.

A glittering cityscape has arisen on the once gritty-waterfront of Manhattan Island. The Atlantic World of commerce, based on shipping and the railroads, that generated the original prosperity of New York City has been eclipsed by the world of finance and wealth. New fortunes have completely transformed the neighborhoods where millions of immigrants first settled. On the new waterfront, most of the redevelopment has been carried out by private capital, not by the city of New York. As with the use of water-lots to create a maritime infrastructure in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the city has once again ceded the future of the waterfront to a powerful combination of public authorities and private interests. It remains to be seen whether this complex arrangement of private/public control will meet the environmental challenges to come.