He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.

– Prov. 13:24 (quoted by Télesphore Gagnon’s lawyer, 1920)

In 1900 the writer Louis Fréchette, who was born in 1839, published his memoirs, in which he described the child-rearing practices of his childhood.

Parents and schoolmasters were certainly no more cruel in those days than today, but the vast majority, if not all, were entirely convinced that children could only go astray if they were not thoroughly beaten at least three times a week. A switch, a cane, a whip, and often even a stout stick, were considered essential tools for the improvement of youth and the salvation of younger generations. Bringing up children meant extreme flogging; punishing them meant breaking their bones. Such were the recommended means and method: “Fathers and mothers, chastise your children, take up the rod, beat them, tame them: each stroke that you give them adds a jewel to your future crown; break one of their limbs if you have to; it is better that your child go to heaven lacking an arm or leg than to hell with limbs intact.”1

Here Louis Fréchette was expressing himself with a humour that made it easier for him to evoke such painful memories. Besides, he did not dare to accuse parents of cruelty, preferring to attribute their severity to the influence of religion. But was the recommended method as harsh as he said? To find out, we undertook a systematic search in the pedagogical journals published between 1850 and 1920 that were aimed at a readership of teachers, selecting about thirty articles on child-rearing (see Table 1). Our second source consists of eight periodicals intended for parents, from 1873 to 1969 (see Table 2). Each of these had a distinguishing feature. For instance, Le Foyer Canadien was a family newspaper for Francophones living in Massachusetts. La Mère et l’Enfant was produced by a doctor who wished to reduce infantile mortality. La Famille and La Famille chrétienne both had priests as editors. The department store Le Bon Marché offered its customers the magazine La Femme. Le Coin du feu, and La Bonne Parole expressed the ideas of the earliest Quebec feminists. Finally, La Tempérance was a tool of the Franciscans in their campaign against alcohol. As can be seen from the titles, half of these magazines were meant for women and mothers and the other half for both parents, but none was aimed specifically at fathers.

In these eight magazines we found fifteen articles from before 1920 that dealt specifically with corporal punishment, five of them by priests (see Tables 3, 4, and 5). We supplemented this corpus with twenty or so books (six of them by Canadian authors), most of which are quoted in these articles. Unanimity reigned where the basic principles of education were concerned, but the manner in which they were applied varied considerably from author to author, some calling for extreme severity but others for greater moderation.

Table 1 Pedagogical Journals Published in the Province of Quebec, 1857–1969

Note: To avoid an excessive number of tables, in the tables 5, 10, 12, 13, 15, 17–19, and 21–26 we have given the combined data without indicating the chronological evolution. When a significant change took place during a specific period we have indicated this in the body of the text.

Table 2 Quebec Magazines for Parents, 1873–1969

Table 3 Distribution by Decade of Articles Dealing with Corporal Punishment in Quebec Family Magazines, 1873–1969

1873–79 |

1 |

|---|---|

1880–89 |

0 |

1890–99 |

7 |

1900–09 |

4 |

1910–19 |

3 |

1920–29 |

5 |

1930–39 |

8 |

1940–49 |

61 |

1950–59 |

72 |

1960–69 |

2 |

Total: 163 texts (99 articles and 64 replies) |

|

Table 4 Distribution of Articles Dealing with Corporal Punishment in Quebec Family Magazines, 1873–1969

PERIOD |

MAGAZINE |

NO. OF ARTICLES |

|---|---|---|

1873–74 |

Le Foyer canadien |

1 |

1890–91 |

La Mère et l’enfant |

0 |

1891–95 |

La Famille |

2 |

1893–96 |

Le Coin du feu |

3 |

1898–1901 |

La Famille chrétienne |

3 |

1908–12 |

La Femme |

0 |

1906–37 |

La Tempérance |

8 |

1913–34 |

La Bonne Parole |

5 |

1934–39 |

Familia |

3 |

1938–49 |

8 |

|

1939 |

La Femme de chez nous |

0 |

1937–54 |

La Famille |

19 + 14 letters |

1955–60 |

La Famille |

2 |

1944–69 |

Collège et famille |

19 |

1946–54 |

Le Foyer rural |

5 + 1 letter |

1949–57 |

L’École des parents |

20 + 10 letters |

1954–55 |

La Revue des parents |

1 |

1948–55 |

Le Devoir |

0 + 39 letters |

1967–68 |

La Femme canadienne française |

0 |

1968–69 |

Le Foyer |

0 |

Total: 163 texts; 99 articles and replies to 64 |

||

Note: Some magazines contained articles dealing with child-rearing, but none discussed corporal punishment specifically.

The French-Canadian contributors to these publications were all Roman Catholics. For them the ultimate objective of parenting was to equip the child with a moral foundation that would allow it to achieve heavenly bliss after death. A heavy responsibility thus weighed on parents, who would have to account to God for the fate of the children He had entrusted to them.

The doctrine of original sin made these advisers on child-rearing likely to see a mixture of good and evil tendencies in the souls of children.2 This meant that the former had to be cultivated and the latter combatted. The theories of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, with his belief in the innate goodness of the human being, were known and frequently cited, but always rejected. Some authors suggested that children’s personalities could be moulded like soft wax.3 Others preferred an analogy — well suited to a rural society — with the work of a gardener who uproots weeds as soon as they appear.4 In each case, the involvement of the parents was primordial. Indeed it was to this end that God had delegated part of His authority to them.

Table 5 Authorship of Articles and Replies to Letters on the Subject of Corporal Punishment in Quebec Family Magazines, 1873–1969

|

ARTICLES AND LETTERS |

AUTHORS |

|---|---|---|

Priests |

32 |

23 |

Laymen |

15 |

12 |

Laywomen |

48 |

29 |

Nuns |

1 |

1 |

Couples |

48 |

10 (5 couples) |

Anonymous |

18 |

18 |

Collective |

1 |

3 (1 priest and 2 laymen) |

Total |

163 |

96 individuals |

The primary duty of parents was to set their children a good example. In particular they had to take great care not to swear or blaspheme in their presence. Father Boncompain, a Jesuit preacher, told a piquant story on the subject. A mother, hearing, her little boy using bad words, prepared to spank him. But she stopped with her hand in the air when the child cried out to her, “But Mama, Papa says that all the time!”5

The principal warning given parents concerned the danger of spoiling children, in other words letting them do whatever they wanted, giving into all their whims, without ever scolding them to correct their misdemeanours. This detrimental tendency was ascribed to the selfishness and ill-conceived affection of parents who wanted to enjoy their children without troubling to bring them up properly. In fact, such parents did not really love their children, for genuine love was not blind and well able to administer punishment if required.6

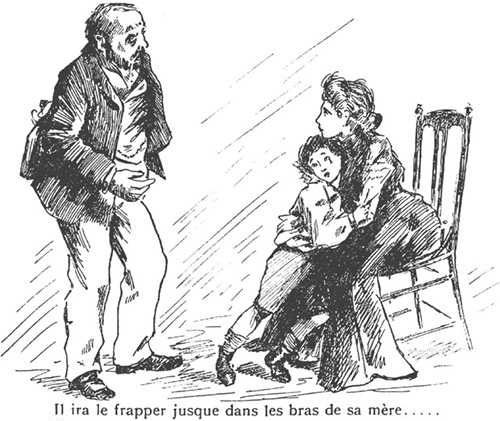

Illustration 1 “He will go over and strike him, even in his mother’s arms …”

A drunkard’s brutality was one of the first forms of violence toward children to be condemned in Quebec.

Source: “Le père brutal,” La Tempérance 4/2 (June 1909), 34. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Franciscans of the Province of St Joseph in Canada.

The contrary excess, which was condemned almost as frequently, consisted of treating children harshly at the risk of dulling their wits.7 Punishment administered in anger was disapproved of, for parents risked going too far.8 Excessive or too frequent beatings were also condemned, for they could produce a fearful, untruthful, or rebellious child. But the strongest blame was reserved for fathers with an excessive affection for the bottle who brutalized their children while drunk (see Illustration 1).9 This form of violence was characterized as ill-treatment rather than punishment, for its purpose was not to punish a misdemeanour. Similarly, some advised against beating children who wet their beds at night “when unable to help themselves.”10 But while suggesting medical treatments for bed-wetting, which was considered an illness, one advertisement confirmed that “when a child intentionally misbehaves it is proper to punish him.”11

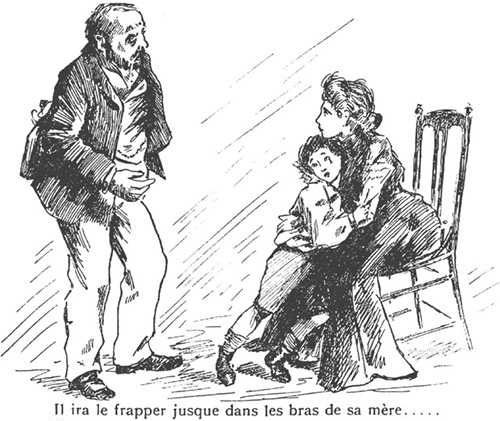

TOP LEFT Mr Bogeyman carries off naughty little boys. TOP RIGHT Mrs Bogeyman gives greedy little girls a thrashing. BOTTOM L Mr Bogeyman looks for liars to cut off their tongues. BOTTOM R Mrs Bogeyman shuts disobedient little girls in with the rats.

This engraving dates from around 1840. In Quebec, starting in the nineteenth century, child-rearing authorities forbade frightening children with such stories.

Source: Denis Martin and Bernard Huin, Images d’Épinal, © Musée du Québec and Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1995, with the kind permission of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and with the collaboration of the Musée départemental d’art ancien et contemporain and the Musée de l’image d’Épinal. Photo: MNBAQ, Patrick Altman.

A third error to be avoided was frightening children by telling stories about bogey men, werewolves, ghosts, or other imaginary creatures. A popular print from 1840 shows how M. and Mme Croquemitaine [Mr and Mrs Bogeyman] beat naughty children, cut out their tongues, or shut them in with rats (see Illustration 2).12 From 1857 on, Quebec doctors and pedagogues were agreed in condemning such tales, which not only risked traumatizing children, but could even result in nervous illness.13

For the same reason, some people condemned the practice of shutting children up in dark rooms. From the middle of the nineteenth century, Charlotte Brontë and Victor Hugo had described the fear that the dark can cause in children. The English novelist told how, after being shut up inside a room where she imagined seeing a ghost, a little girl suffered a nervous shock, the repercussions of which remained with her into adulthood. The person responsible was an aunt who merely thought that she was eradicating the child’s bad tendencies. Charlotte Brontë was more concerned to describe the circumstances and consequences of this punishment than beatings administered with a rod, however much these were feared. Victor Hugo described the fate of Cosette who was abused by her foster parents: they sent her out in the dark of night to fetch water from a well deep in the forest.14 In 1893 a woman writer related in a Quebec magazine how she had seen a little girl of nine suffering from nervous spasms after a primary teacher had shut her in a cellar, threatening to have her devoured by rats.15 Twenty years later Georgine C. Lemaire would retell the same story, this time saying that the little girl died in the throes of horrible convulsions.16 On this point, however, the opinions of all writers did not evolve at the same rate. As late as 1919 one pedagogical journal endorsed unreservedly the attitude of a mother who shut her little five-year-old son up in a dark room to punish his poor behaviour (see Illustration 3).17

In 1919 some experts still accepted shutting the child inside a dark room as a legitimate form of punishment. Notice the mother’s calm and resolute air, the little girl’s sad eyes, and the grandmother’s sorrowful attitude.

Source: L’Enseignement primaire 41/3 (Nov. 1919), 172.

Once it was accepted that the aim of parenting was to bring children up in the way they should go without spoiling or terrorizing them, what was the appropriate method to achieve this objective? Among the range of opinions expressed, some opted for an authoritarian approach, making obedience the primary virtue of a child. In providing the ten rules of sound child-rearing that were addressed to parents in 1917, first place on the list went — just as in 1857 — to “Accustom your children to immediate, total obedience from the earliest age.”18 But by what means? Since an example is worth a thousand explanations, we cite the one provided by a certain Dr Abbott, in which he explained to parents how to “permanently tame the most intransigent nature” (see Box 1).19

Box 1 “How Children Are Taught to Obey”

Extract from a book by John S.C. Abbott, The Mother at Home, or The Principles of Maternal Duty Familiarly Illustrated, reproduced in French as part of an article in the Journal de l’Instruction publique (May 1857, 94–5).* Reverend John Stevens Cabot Abbott (1805–1877) was a Congregational Church minister. Philip Greven considers that his book represented “the moderated view of early 19th-century evangelicals.” Philip Greven, Child-Rearing Concepts, 1628–1861: Historical Sources (Itasca: F.E. Peacock, 1973), 113.

“Mary! Mary! You must not touch the book,” says a mother to her little daughter, who is attempting to pull the Bible † from the table.

Mary stops for a moment, and then takes hold of the book again.

Pretty soon the mother looks up and sees that Mary is still playing with the Bible. “Did you not hear me tell you that you must not touch the book?” she exclaims: “why don’t you obey?”

Mary takes away her hand for a moment, but is soon again at her forbidden amusement. By and by, down falls the Bible upon the floor. The mother rises in anger, and hastily gives the child a passionate blow, exclaiming, “There! The next time obey me.” The child falls upon the floor and fills the apartment with cries of resentment and anger, while the mother replaces the fallen volume, wondering why it is that her children did not obey her commands.

…

I was once, when riding in the country, overtaken by a shower, and compelled to take shelter in a farmhouse. Half a dozen rude and ungovernable boys were racing about the room, in such an uproar as to prevent the possibility of conversation with the father, who was sitting by the fire. As I, however, endeavoured to make some remark, the father shouted out, “Stop that noise, boys.”

They paid no more heed to him than they did to the rain. Soon again, in an irritated voice, he exclaimed,

“Boys, be still, or I will whip you, as sure as you are alive I will.” But the boys, as though accustomed to such threats, screamed and quarrelled on without intermission.

At last the father said to me, “I believe I have got the worst boys in town; I never can make them mind me.”

The fact was, these boys had the worst father in town. He was teaching them disobedience as directly and efficiently as he could. He was giving commands which he had no intention of enforcing, and they knew it.

…

And is there any difficulty in enforcing obedience to any definite command? Take the case of the child playing with the Bible. A mild and judicious mother says distinctly and decidedly to her child, “My daughter, that is not the book for you, and you must not touch it.” The child hesitates for a moment, but yielding to the strong temptation, is soon playing with the forbidden book. The mother immediately rises, takes the child, and carries her into her chamber. She sits down and says calmly, “Mary, I said that you must not touch the Bible, and you have disobeyed me. I am very sorry, for now I must punish you.”

Mary begins to cry, and to promise not to do so again.

“But, Mary,” says the mother, “you have disobeyed me, and you must be punished.”

Mary continues to cry, but the mother seriously and calmly punishes her. She inflicts real pain — pain that will be remembered.

She then says, “Mary, it makes me unhappy to punish you. I love my little daughter, and wish to have her a good girl.”

She then perhaps leaves her to herself for a few minutes. A little solitude will deepen the impression made.

In five or ten minutes she returns, takes Mary in her arms, and says, “Mary, are you sorry that you disobeyed me?”

Almost any child would answer “Yes.”

“Will you be careful and not disobey me again?”

“Yes, mother.”

“Well, Mary,” says her mother, “I will forgive you, so far as I can; but God is displeased; you have disobeyed Him as well as me. Do you wish me to ask God to forgive you?”

“Yes, mother,” answers the child.

The mother then kneels with her daughter and offers a simple prayer for forgiveness, and for the return of peace and happiness. She then leads her out, humbled and subdued. At night, just before she goes to sleep, she mildly and affectionately reminds her of her disobedience, and advises her to ask God’s forgiveness again. Mary, in childlike simplicity, acknowledges to God what she has done, and asks him to forgive her, and take care of her, during the night.

When this child awakes in the morning, will not her young affections be more strongly fixed upon her mother in consequence of the discipline of the preceding day? As she is playing about the room, will she be likely to forget the lesson that she has been taught, and again reach out her hand to a forbidden object? Such an active discipline tends to establish a general principle in the mind of the child, which will be of permanent operation, extending its influence to every command, and promoting the general authority of the mother and the subjection of the child.

I know that some others say that they have not time to pay so much attention to their children. But the fact is, that not one-third of the time is required to take care of an orderly family, which is necessary to take care of the disorderly one. To be faithful in the government of your family, is the only way to save time. Can you afford to be distracted and harassed by continued disobedience? Can you spare the time to have your attention called away, every moment, from the business in which you are engaged, by the mischievousness of your wilful children?

* The English text reproduced here is from the 1852 edition (New York: Harper & Bros.), 47–53.

† See n20, this chapter.

This text, which was published in French in 1857, exhibits almost all the characteristics of the authoritarian method that would later be denounced by Alice Miller. First, children’s boisterous behaviour is characterized as misbehaviour. Then, in his anecdote about the little girl and the book, the author fails to mention the child’s age and provides no information about her tastes or personality. Perhaps this was a little girl of school age who was already showing intellectual curiosity. Nor does he say whether the object of the dispute was a book intended for adults or children.20 If it was the latter, the desire to read it could be considered quite legitimate. But for the author none of that was important. The book was an object chosen at random. All that mattered was blind obedience to the mother’s orders. That is why she made no effort to forestall the girl’s disobedience, for instance, by putting the volume out of her reach or suggesting a different activity. As for the punishment, inflicted dispassionately but with enough severity to leave a lasting memory, it was intended to make the child humble, submissive, and respectful, and help her to make a mental connection between disobedience and suffering. The author took no account of the possibility that it might provoke anger or rebellion, encourage hypocrisy, or that the violence might be passed on to other children. Finally, the mother justifies her severity by declaring that she “loves her child and wants to make her good,” making an appeal to divine authority as an endorsement of her own: “You have offended God because you have disobeyed Him as you did me.” But the desire to ensure peace and quiet for parents by reducing children to silence is quite obvious.

So at what age should this training in unconditional obedience begin? Fernand Nicolaÿ, a French author known in Quebec, suggested that it should commence around the age of two or three — in other words as soon as the child begins to manifest a will of its own. “He must be brought to heel very young, reined in from the outset, or else you may never become his master.” After receiving two or three severe corrections a child would think twice before disobeying for no good reason, having learned from experience that he would come off second best. Nicolaÿ was emphatic: under no circumstances should there be any arguing with the child or use of indirect means to get him to obey, for “winning over is not winning,” and the child’s capitulation had to be total and absolute. With complete consistency Nicolaÿ declared that discipline should come before persuasion and severity before mildness. In this way parents would be armed with an authority that allowed them to give their children a strict upbringing, devoid of indulgence.21 The ultimate justification for such severity was the requirement to toughen the child to prepare it to confront the harsh realities of life.22

Some authors thought that the child should learn to obey even earlier, all the way from the cradle. No one suggested that babies should be beaten, but doctors did recommend resisting their whims to prevent them from turning into little tyrants. We should remember that these doctors were attempting to reduce the infant mortality rate by improving the quality of maternal care. To this end they prescribed a rigid timetable, allowing the mother to pick up the infant only for feeding, bathing, and changing diapers, after which it should be returned to its crib and left there without being rocked. No attention should be paid to its cries: it would eventually become accustomed to this system.23 Abbé Bethléem, a French priest familiar to the Québécois, offered the same advice: “We have seen a child crying for hours in its crib because it wanted its mother to pick it up. It was eight months old. It was already spoiled.” A spoiled child was what these authorities feared the most.24

The rod, considered indispensable by strict authors like Nicolaÿ, was not the only way to ensure children’s obedience: respect for their parents was another. Thus Father Boncompain disapproved of mothers who in their eagerness for affection pampered their babies, smothered them with kisses, showered them with syrupy, extravagant words, and almost made playthings of them. He believed that such immoderate displays of affection diminished the parents’ authority, as did the use of the familiar tu form of the pronoun, which resulted in excessive familiarity.25 (In the French translation of the example given by Dr Abbott the mother uses the more formal vous when punishing her daughter.) These unbending instructions are somewhat reminiscent of Jules Vallès’s memoirs: “I do not recall a single caress during the years when I was very small; I was never cossetted, stroked, or kissed; I was beaten a great deal. My mother held that children should not be spoiled, so she gave me a hiding every morning.”26

When it came to a beating, all these authors insisted that the punishment should be administered calmly. A French priest, Father Idoux, recounted how on one occasion his mother, in a fit of anger, decided not to beat her disobedient children. She waited three days before taking up the “terrible rod” because she considered that since she was no longer angry she could punish them to greater effect.27 This childhood memory is very reminiscent of a scene in the Ingmar Bergman film Fanny and Alexander when Alexander’s stepfather (a Protestant bishop) ceremoniously administers ten strokes of the rod to his buttocks after assuring him that he loves him with a stern, lucid affection.28 In contrast to these depictions of calm, resolute caregivers stands the contraindicated example of the shrieking virago who unleashes a shower of blows from a broom on her young rascals, accompanied by much bad language.29

If children had been accustomed to total submission from early childhood they could be expected to remain obedient throughout the difficult adolescent years and into adulthood. In this respect Abbé Idoux cited the example of his twenty-two-year-old brother who, if he did not wish to be exiled from the family home, was obliged to accept his mother’s orders without arguing after she forbade him to go out with friends, even though they were irrreproachable.30 Abbé Idoux, Joséphine Dandurand, and many others proclaimed that the virtue of obedience endowed children with a strong personality and a virile temperament; it enabled them to resist their passions.31 The spoiled child, on the other hand, already had one foot in hell according to Abbé Bethléem. Bethléem cited the examples of all the famous individuals such as Saint Augstine, Henri IV, and Louis XIII, who had experienced severe discipline in childhood — though he did fail to mention Martin Luther, who was brought up according to the same principles!32

Among the opinions expressed by proponents of strict parenting we find several principles of the “poisonous pedagogy” denounced by Alice Miller:

• Obedience creates strength.

• Shows of affection (sentimentality) are harmful.

• Parents should not give in to a child’s demands.

• Strictness and coldness provide a good preparation for life.

• Parents are always right.33

These Catholic authorities, like the Protestant ones studied by Philip Greven, found an endorsement in the biblical texts which they interpreted literally as the very will of God:34

Withhold not correction from the child: for if thou beatest him with the rod, he shall not die. Thou shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell. (Prov. 23:13)

A horse not broken becometh stubborn, and a child left to himself will become headstrong … (Ecclesiasticus 30:8)

He who spares his rod hates his son, But he who loves him disciplines him promptly. (Prov. 13:24)

The rod and rebuke give wisdom, but a child left to himself brings shame to his mother. (Prov. 29:15)

For good measure they ended with a proverb thought to express the wisdom of the ages: Qui aime bien châtie bien [“Spare the rod and spoil the child”]. In short, these rigorist authors almost considered corporal punishment a religious duty as well as a proof of parental love. So Louis Fréchette’s words, despite their humorous exaggeration, are not entirely without foundation.

The avowed intention of the advocates of authoritarian child-rearing went beyond the desire to eradicate the child’s depraved tendencies. Their desire to tame or subdue the child has the appearance of a battle of wills, a struggle between parent and child in which no quarter could be given. Such an approach involved a risk, for in a battle of this kind physical strength was on the side of the adults, and they often lacked a proper understanding of vague notions like “severity” or “reasonable punishment.”

Recommendations of severity were not restricted to works intended for parents. An item that appeared in La Patrie in 1910, entitled “L’éducation de la poupée,” showed a little girl re-enacting the events of her daily life with her doll: washing, dressing, lessons, visits, shopping, etc. When the doll misbehaves she is beaten like a naughty little girl (see Illustration 4). This was the author’s way of encouraging his young readers to accept the punishment inflicted on them and preparing them to bring up their own children in the same way. This is the process by which violence is reproduced, one that was later analysed and criticized by Miller, Straus, Greven, and many others.

Illustration 4 Bringing Up Dolly

LEFT “Missy, I’m off to market, I hope you’ll be good.” MIDDLE Dolly misbehaved, so she gets a whipping. Serves her right! RIGHT Dolly asks her mistress for forgiveness and promises to obey.

Source: “L’éducation de la poupée,” La Patrie (27 Aug. 1910), 2.

The strong-handed approach to child-rearing was endorsed by some men of law. In 1843, when Canadian parliamentarians were discussing the creation of reform schools that would allow young delinquents to be removed from adult prisons, one MP named Dunlop declared that children should simply be whipped and sent to bed.35 At the turn of the century, Judge Lafontaine, who sometimes had to deal with such young people, remarked that in several cases, the whip applied with prudence and moderation was the only effective remedy,36 and even a member of the Society for the Protection of Women and Children was of the opinion that children who stole should be whipped in front of the court by a policeman.37 This last example is a particularly good illustration of the distinction made at the time between corporal punishment and physical abuse. However, these apologists for the “poisonous pedagogy” had to confront dissenters convinced that the whip was not an adequate solution for all the problems of child-rearing.

Not everyone shared the strict approach of Nicolaÿ or Father Boncompain, who considered the whip an essential tool in raising children. Some opted for a gentler method, including Abbé Mailloux, the author of one of the first child-rearing manuals written for parents.38 While granting the need for “salutary punishment” to suppress undesirable tendencies, he expressed the opinion that “one should strike children only rarely, when other means of correction have proven ineffective.” Contrary to Nicolaÿ, who advised putting discipline before persuasion and severity before kindness, Mailloux suggested treating the child as a rational being and reserving punishment for serious misdemeanours. This priest also understood that the mere prospect of physical punishment was enough to induce fear in children and could cause more harm than good. To convince his readers he quoted the case of a quick-tempered child whose father believed he should be dealt with severely:

Two men were brought in carrying rods. The father then had the child seized and gave the order to beat him. Suddenly, the child turned pale and stopped crying out and weeping. His anger gave way to stupor. He was questioned, but gave no answer: he had just lost the use of his mental faculties and remained a half-wit.39

Abbé Mailloux also differed from Dr Abbott in not considering boisterous behaviour a serious fault in children. “Let them romp, run, and have innocent fun. Their health and their age require it.” And if “this noise, these cries and chases” exasperate the parents, they should suffer in patience, for it was one of the minor afflictions of their condition. As a model he quoted St Philip Neri, who said in similar circumstances, “Provided they are not offending against God I would allow them to break sticks on my back.”40

On his list of faults and misdemeanours deserving punishment Abbé Mailloux put disobedience no higher than in third place, after anger and pride. For him, stubbornness was a vice among others that one should attempt to correct by reasoning with children, by imposing various punishments on them, and as a last recourse, having them solemnly reprimanded by the parish priest.

Taking his inspiration from a method that dates back to Quintilian, Abbé Mailloux also advised that before undertaking to raise children parents should observe their characters in order to understand them properly, and then correct their faults by practising the contrary virtues. Then he proceeded to the enumeration reproduced in Box 2: “There are characters stubborn and quick tempered, bold and brazen, concealed and counterfeit, fundamentally bad, … gay and frivolous, frank and open, gloomy and melancholy, gentle and sympathetic, well-behaved and docile.”41 This classification, imbued with moralism and taking no account of the stages in a child’s development, may seem naive and rudimentary to us. However, the author does have the merit of having tried to understand different temperaments and to adapt the style of upbringing to each, instead of recommending the whip indiscriminately. When a child appeared to be less perfect or well behaved than others, he suggested that the parents should show it more affection and compassion in order to help it improve, just as they would care for a child who was ill. This was advice that modern psychology would not disown. Finally, this author listed several biblical quotations in praise of children’s obedience, but never cited those proverbs that mention the use of the rod. Instead he quotes St Paul’s advice: “Fathers, provoke not your children to anger, lest they be discouraged” (Col. 3:21).42

The ideas of Abbé Mailloux, who expressed serious reservations about corporal punishment, would reappear in the pastoral letter on child-rearing published by the Canadian archbishops in 1894. While insisting on training children to be obedient, they declared that corporal punishment was the least effective remedy of all, and invited parents to forestall misbehaviour in order to avoid the need to repress it.43

Box 2 Indications of Character

See this child who stamps his feet if he is refused something, who will never give in, who always has to have his way, who throws whatever object comes to hand at the head of anyone who displeases him, who sulks at anyone who frustrates him, who sheds tears accompanied by sharp, intermittent cries, who a day after some irritation still has not forgotten it, who cannot bear anything, and whose mother cannot make him keep still: his is a stubborn, peevish character.

Look at this little lad with shining eyes who challenges your gaze, who fears nothing, who cries only when he has been [scolded] at length, whose tears come in a roar, you might say, who laughs at everything and stands up to anything, even to punishment, who strenuously denies his faults, who likes noisy games and battles and shouts at the top of his lungs; this young lad has a daring, impudent character.

Examine this little girl with the sly expression who hits her little brother whom she is cradling, who pinches him and then blames him for crying out, who is watching out from the corner where she is eating a stolen sweetmeat, who reduces her little sister to tears and asks her at the top of her lungs what is upsetting her, who is angelic to look at but who is busy watching out for the chance to do something nasty when no one is watching, who caresses her mother when she is present and cares nothing for her behind her back, who has just gone where her mother forbade her to go and denies it without a blush, who pretends to cry when her mother corrects her, who proclaims her friendship a thousand times to a companion whom she then despises, who seems an angel but is really a demon: this unfortunate little one has a hidden, secretive nature.

Have you seen this little boy who can never be satisfied, who asks for bread and jam but throws it on the floor after a single bite and then asks for another, who hits his little sisters and laughs to see them cry, who snatches from them a toy they love and breaks it, laughing at their tears, who punches his little brother and crows when he knocks him over, who laughs when his Mama scolds him, who gets in a rage when he is punished and threatens to repeat the deed for which he was beaten, who does not love a living soul, not even his unhappy mother, who steals and then denies it, whom no one can win over, not by punishment, nor kindness, nor gifts, nor tears? This little boy will drown his parents with sadness if they are unable to correct his bad character.

Children with a gay, frivolous temperament are easy to recognize. They are always content and good humoured, they laugh and are easily entertained, they pick up a game but drop it immediately to pick up another that they also abandon a moment later. They like to run, jump, and try the patience of others, they laugh and cry almost together, they pay little heed to reprimands and go on repeating the same bad behaviour, they whine and beg a thousand times to obtain a thing, yet once they have it they no longer want it, they begin some little task, devote themselves to it body and soul, but then leave it half-finished and move on to another that they finish no more than the first. Such children are shallow and fickle.

This little child who says what he thinks, who suffers punishment with resignation and admits his errors, who simply admits the wrong he has done and is sorry for it, who never seeks concealment in doing or saying what comes into his mind, who pays a positive or negative compliment with the same candour, who loves his brothers and sisters greatly, this little boy exposes his soul for his Mama to read like an open book; he has a frank and open personality.

This little girl with sad, pale features, who almost never laughs, who does not like to play with other children, who often weeps for no reason and whose tears have a mournful quality, whom one cannot rebuke without grieving her, who prefers her own company, who never thinks of play, who seems to rack her brains for a reason to be sad, this little girl is already unhappy and will make those who must live with her unhappy also, for hers is a gloomy, melancholic temperament.

This little child who never hurts his brothers and sisters, who does not lose his temper when annoyed, who kisses his little sister who has played tricks on him and cries because her mother punished her for it, who willingly shares the candies he has been given and never eats one without offering them round, who listens to his mother’s advice and begs forgiveness with tears in his eyes for some naughty thing he has done, who gives away a valued possession to cause pleasure for another, who loves his mother and father dearly and whose greatest fear is making them grieve, who goes to caress his mother when he sees she is sad and gives her a kiss to cheer her, this charming child can say like Solomon: “I am a well-born child, and God has granted me a good soul.” For this child has a good, docile character.

Source: Abbé Alexis Mailloux, Le Manuel des parents chrétiens (Quebec City: L’Action sociale, 1909 [1851]), 55–8.

Some lay authors thought along similar lines and pointed out the disadvantages of the strong-handed approach to child-rearing. “Gertrude” also advised allowing the “little pests” free rein.44 Dr La Rue felt that above all children’s characters should be taken into account. If they responded to kindness and reason, corporal punishment should be carefully avoided since it could only embitter them while failing to correct their faults.45 The worst mistake that parents could commit, wrote another, was to try to break their child’s will. Far from making children submissive, such repression risked making them even more obstinate when with a little tact their obedience might easily have been obtained.46 The behavioural problems of many children, added a third, arise from the irritation provoked by such “bad management.” Those treated harshly by their parents would be inclined to act in the same way toward their brothers, sisters, and playmates, whether because of the example they were given or because of their tendency to avenge themselves upon others for the blows they had received — a “tendency to vicarious retaliation.”47 This analysis would be taken up over a century later by Alice Miller and other authors.48

If they were to act properly, wrote an Anglophone author in 1886, all parents required some knowledge of psychology. It would prevent them from committing errors of judgment, like the mother who said, on hearing her six-month-old baby crying, “I believe he knows he is doing wrong.”49 Children also needed affection, and there were consequences if they were deprived of caresses. These did not preclude discipline, wrote Bersot, but they did moderate it. And he took to task those parents who imposed trials and tribulations on their children claiming it was a preparation for the difficulties of life: “They should not be so harsh; life will be harsh enough.”50

The differences between parenting with the rod and an approach based on reasoning are obvious, but most authors borrowed elements from both approaches. Monsignor Ross was one such. He advised studying children’s characters,51 interpreted the biblical texts circumspectly, and stressed the disadvantages of disciplining with a rod, for it risked breaking the child’s will on the pretext of bending it. “If we had fewer flexible spines revealing the souls of slaves, the rights of the French Canadian race would not be in such jeopardy.”52 Yet he did not go as far as to rule out corporal punishment entirely:

Parents who see their little man of three and four and even younger express his imperious determination to have his way by cries, clenched fists, and threatening glances, it would be a mistake to seek some high-flown reflections to make him understand that he has overstepped the mark. When a severe or sorrowful glance, or the appropriate tone of voice from his father or mother are unable to calm him, there remains the remedy, very instructive in such circumstances, of a good spanking, which will attract to less excitable regions the flow of blood to the brain which had exasperated him. This is the case in which the advice of Proverbs is literally applied: “Do not withhold correction from a child, for if you beat him with a rod, he will not die.”53

Here Monsignor Ross is taking up Nicolaÿ’s ideas. He fails to understand the risk of breaking the child’s will (though he does fear such a prospect) and affecting his subconscious mind from as early as the preschool years. It would be up to psychoanalysts, Alice Miller in particular, to explore these consequences of corporal punishment.

Between 1850 and 1919, moralizing and severity predominated in the advice given to parents. Throughout the entire period only three authors among those who wrote in family magazines advised never striking children. Several authors writing in pedagogical journals recommended that corporal punishment be abolished in schools, though a few, such as Joséphine Dandurand and Elizabeth Oakes, did sometimes recommend it be retained in the home.54 This exception was based on the conviction that parents felt an innate love for their children that mitigated their severity.55

However, some signs of change began to appear at the end of the nineteenth century. It was at this time that experimental pedagogy and psychology were born. Alfred Binet (best known for developing the first IQ tests) declared in 1898 that the observation and scientific analysis of children’s behaviour were destined to replace the empirical knowledge accumulated over the preceding generations.56 Binet maintained that a study of children’s psychology would prove more useful to their upbringing than corporal punishment, finding that “nothing is more distressing than the face of a beaten child.”57 Psychoanalysis also came on the scene. In 1905, in an essay on infant sexuality, Freud, basing himself on the example of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, pointed out that spanking was one of the causes of masochism, and endorsed those authorities who wanted to spare all children corporal punishment.58 Some years later he approached the problem of parenting in a more general way, stressing the extent to which “a pointless or narrow-minded severity in child-rearing contributes to the formation of nervous diseases.”59 But Freud did not always contradict traditional notions, for he also wrote that “neuropathic parents, who usually exhibit an unrestrained tenderness, will awaken a disposition for neurotic diseases in the child.”60 The “New Education,” a term dating from 1898, would draw on the contribution of these scientific disciplines.

___________

The child-rearing authorities who wrote before 1920 had several points in common: the predominance of the moral and religious aspects of child-rearing, an argument based on the Bible, the writings of the Church Fathers and their personal experience, and the rarity of references to psychology, a science as yet little known in Quebec. All advised avoiding two pitfalls: spoiling children and treating them too harshly. That said, there was a gulf between the proponents of a strict upbringing and those who advocated the use of reasoning. Furthermore, the reader will have noticed that in his book published in 1851 Abbé Mailloux advised much less severity than Father Boncompain in 1914 and 1918, showing that notions of child-rearing have not always evolved toward greater leniency.

The stories told by some authors reveal how they themselves reacted to the violence inflicted on them in childhood. Abbé Idoux, brought up strictly by a mother who demanded unconditional obedience, approved of such a method and recommended it to all parents. He provides an excellent example of the way the “poisonous pedagogy” denounced by Alice Miller and Philip Greven is passed on to others. Louis Fréchette, brought up less strictly by a father who alternated displays of affection and corporal punishment, dared to castigate the excessive severity for which he blamed the influence of the clergy of his day. These two examples show that adults did not automatically reproduce the approaches to upbringing that they themselves had experienced, as was also stressed by sociologists at the end of the twentieth century.61

The notions of child-rearing expressed in Quebec differ little from those put forward in the rest of Canada. There also, parents were warned against the two extremes of unlimited indulgence and excessive severity. During a conference on the protection of children held in Toronto in 1894 several participants expressed the opinion that whipping was the best solution to the problem of juvenile delinquency. The principal advocate of the children’s protection movement, John Kelso, instead counselled love, studying the child’s character, using patience, and giving individual attention, though he did not completely exclude the possibility of reasonable corporal punishment.62 Things were no different in the United States. We have seen that the ideas expressed by Reverend Abbott and quoted in the Journal de l’Instruction publique coincided with those of Nicolaÿ and Father Boncompain. In addition, in 1874, a board member of the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children clearly endorsed whipping disobedient children, despite his desire to protect the victims of excessively harsh parents.63 So, in short, in the rest of North America there was a range of opinions similar to those observed in French Canada.

The child-rearing advice contained in Quebec books and periodicals was able to reach the wider public by way of Sunday sermons and parish retreats. Father Boncompain, for instance, initially preached at retreats before he published his sermons in the Montreal Bulletin paroissial de l’Immaculée Conception, which had 50,000 subscribers.64 His first book, Autour du foyer canadien, found its way into more than 12,000 homes and was apparently distributed as an end-of-year prize in normal schools.65

Among the varied opinions available to them, parish priests and other preachers could choose what they preferred according to their own character and upbringing. The testimony by Louis Fréchette seems to show that severity was predominant in the priestly view. It remains to be seen if the general public paid attention to this advice, and if so how it was interpreted and put into effect.