The child was difficult to raise and I punished her several times with an application of the whip and a piece of wood.

– Statement by Télesphore Gagnon during the Coroner’s Inquest, February 1920

Louis Fréchette describes the zeal with which parents punished their children in his native village in the middle of the nineteenth century:

One could scarcely pass a corner of our village without hearing the howls of some youngster whose parents were adding a few jewels to their heavenly crown. I heard one woman say, “God have mercy on me! I’ll never be saved, I have too many children; I haven’t beaten half of them and my hand is worn out already.” “Why don’t you use a stick?” someone asked. “That’s worse,” she answered, “the other day I almost put my shoulder out beating my oldest with a willow rod.”

Apparently there was one exception in the village:

Mrs Horatio Patton, a fanatical Protestant lady who claimed that a child should not be beaten until all other ways to reprimand him had been tried: “Just look at that!” people said. “That poor woman is bringing up a pair of rascals that will end on the gallows, for sure. It’s true they don’t look any worse than the others; but it won’t take her long to spoil them if she keeps on like that.”1

Louis Fréchette stressed the fact that Mrs Patton was a Protestant in order to differentiate her from the Catholic parents who were under the thumb of their priests. But a comparative analysis of the texts written by Catholics and Protestants in Quebec pedagogical journals reveals that some severe and some more indulgent educators were to be found in both confessions.2

Louis Fréchette’s testimony, invaluable because of its rarity, bears more weight because it is complemented by other sources: legal separation cases in the Montreal judicial district, the files of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court in the same city, and newspaper reports. These three kinds of documents help us to understand where the people of the time drew the line between severe punishment and abuse.

Statements made between 1795 and 1919 during legal separation cases allow us, among other things, to glimpse the private lives of families and observe the scenes of violence that took place within them. This source has the advantage of including the rural region around Montreal in addition to the city itself. Obviously it has to be used with caution, for it does not necessarily describe the living conditions in most families, legal separations being exceptional in the nineteenth century. Furthermore, it was in the interests of each of the parties involved to vilify the other.3 While keeping in mind this inevitable bias in the documentation, it is possible to make use of witnesses’ comments to reconstruct the behavioural norms at the time, including the degree of tolerance for violence against children.

Parents considered it a right to strike their child, with no further justification required. When John K. asked his wife why she was beating their son, she answered that she was “the mistress of her child,” whereupon he struck her in his turn, telling the indignant neighbours that he was the master and could treat his wife as he liked.4 In this case, the use of physical force simply demonstrates the power relationship within this family. In general, however, witnesses described physical punishment as a duty that parents were obliged to perform, while respecting certain conditions.

Some thought that in the absence of physical punishment children would inevitably become insubordinate, though there was no unanimity on this point. In Senator Trudel’s family the children were schooled by a private tutor; their mother had forbidden this woman to strike them, suggesting instead that she make them kneel as a punishment. The tutor complained loudly about this lack of severity, which, in her opinion, was bound to make the little boys “unmanageable, disobedient, and disrespectful.”5 Dr M.’s wife left herself open to similar criticism: she was blamed for being too soft with her little girl, spoiling her, and tolerating faults from which she should have been cured.6

Children had to be beaten when they deserved it: this was one of the criteria that differentiated good and bad parenting. When George L. was accused by a witness of having cruelly beaten his son another witness intervened to state that he was “good for his children: he beat them when they deserved it.”7

To ensure it was legitimate, violence used on a child had to be meant to contribute to its upbringing. This was why striking a baby was inadmissible: an infant could not understand the meaning of such punishment.8 Beating a child who had not done anything wrong was also considered a form of abuse.

Among the different explanations for ill-treatment some appeared more frequently than others. Alcohol abuse came top of the list. The description of a father (more seldom a mother) coming home drunk in the evening, creating mayhem, insulting and abusing his wife and children, occurred in innumerable cases. Sometimes the children would be struck when they intervened to protect their mother, but it also happened that the father assaulted them directly. To pay for the drink they consumed, these “unworthy fathers” took the money their children had earned, or sent them out to beg. This stereotype, which was described in temperance literature in Quebec as well as in the United States, finds ample justification in the judicial archives of different Canadian provinces.9 In Europe also alcoholism was recognized as a factor in abuse.10

A second cause of ill-treatment was found specifically in blended families. Step-parents were accused of having no love for the children of a first marriage and beating them “for no rhyme or reason.” Making false accusations to prompt the father to beat his own children was an additional transgression attributed to stepmothers. Ambroise R.’s second wife was accused of this by witnesses appearing on behalf of her husband: not only had she struck her husband’s daughter “with a horsewhip, for no good reason,” but also “as a result of her lies” the husband “beat his child severely several times.”11 This portrait of a typical stepmother, which was also familiar in Europe (one example being Mme Fichini, in the Comtesse de Ségur’s Les Malheurs de Sophie),12 was a portent of the Gagnon case in the following century.

A third source of ill-treatment, less frequently mentioned, was favouritism on the part of a parent. Dr M.’s wife was also blamed for this: she preferred her daughters to her son, casting blame on him for offences committed by the other children, ill-treating him, and dealing him a blow he had not deserved. She apparently even admitted to hating the boy.13 Justified or not, such accusations show that society accepted corporal punishment only in response to children’s misbehaviour.

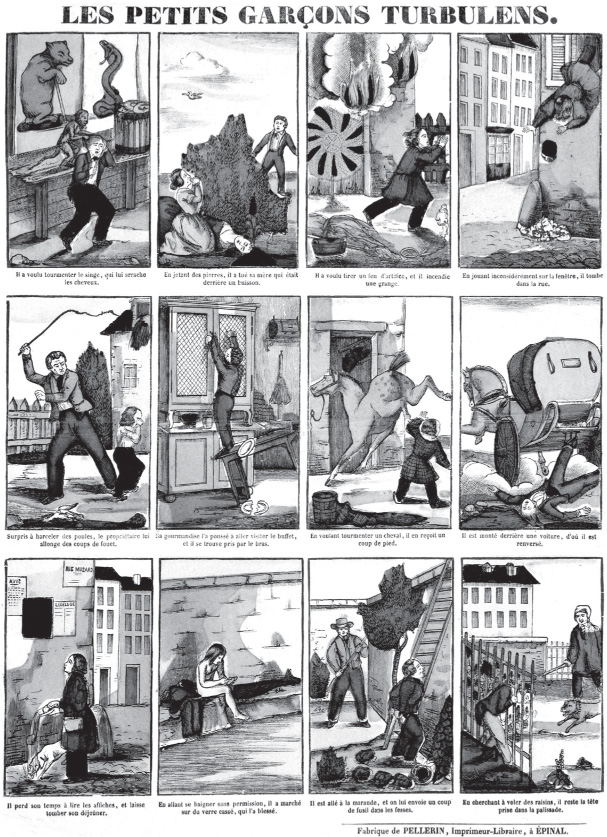

Even when a child deserved punishment parents were expected to observe reasonable limits. But in the nineteenth century what were these limits? A popular print from 1860 portrays the punishment of some mischievous little boys: one is beaten with a whip usually reserved for animals (see Illustration 5). Louis Fréchette did not at all depict himself as an abused child. Nevertheless, his father did on one occasion beat him using the whip from his stable, which the writer describes as “a punishment as serious as it was deserved”14 — enthused by an account of the Patriots’ battles, he had thrown a home-made bomb into the garden of some Anglophone neighbours! Sometimes children would be beaten with a rod. Joseph-Edmond McComber, born in 1874, remembered more than sixty-five years later his father lashing him on the legs with a switch torn from a cherry tree. He also called it a deserved punishment.15 It seems that the threshold of tolerance depended less on the instrument used than on the force of the blows and the frequency of the punishments, or at least this is what the testimony of a twelve-year-old boy from 1875 suggests: “On some occasions I did deserve a beating from my father but not very often, at least not as often as he did it.”16

The first limit to be respected was that the child’s life should not be endangered. In 1823 two neighbours reported parents who beat their children with a leather belt and a stick “too big to be used for beating any person with.” They also considered that these beatings were excessively harsh and inflicted “not for the purpose of correction, but for the sake of ill-using the children.” However, in reply to a question from the officer of the court, they replied that this ill-treatment was not such as to imperil the lives of these children, and as a result the case was dismissed.17

Illustration 5 “Unruly Little Boys”

TOP ROW, L TO R 1. He tries to tease the monkey, but it pulls out his hair. 2. He was throwing stones and killed his mother who was behind a bush. 3. He wanted to set off a firework but set fire to a barn. 4. Playing carelessly on the window ledge, he falls into the street.

MIDDLE ROW, L TO R 1. He is caught teasing some hens, their owner gives him a whipping. 2. Raiding the cupboard out of gluttony, he is trapped by the arm. 3. Teasing a horse, he gets a kick. 4. Climbing on the back of a wagon, he falls off on his head. BOTTOM ROW, L TO R 1. He wastes his time reading posters and drops his lunch. 2. He goes swimming without permission, steps on broken glass, and cuts himself. 3. He goes stealing and gets shot in the rear end. 4. Trying to steal some grapes, he gets his head caught in a railing.

Source: Denis Martin and Bernard Huin, Images d’Épinal, © Musée du Québec and Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1995, with the kind permission of the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec and with the collaboration of the Musée départemental d’art ancien et contemporain and the Musée de l’image d’Épinal. Photo: MNBAQ, Patrick Altman.

The second rule to be observed was that children should not be maimed — especially since among the lower classes manual workers needed all four limbs to earn a living. The French writer Jules Vallès refers to this. He made it a point of honour to tolerate beatings without shedding any tears, provided there was no risk of being maimed. “I had solid bones, I was tough, I was a man. I didn’t cry out as long as my limbs were not being broken, for I would have to earn a living. ‘Papa, I’m a poor boy, don’t leave me a cripple!’”18 The same rule prevailed in Canada. In 1851 one witness told how a farmer set about beating his daughter, aged about fifteen, using a willow rod. “He seemed to want to punish his children the usual way, without maiming them.”19

So, beatings with a whip or a switch were tolerated by society to a certain extent. On the other hand, kicks and blows with the fist were synonymous with brutality, as was dragging children by the hair20 or beating them until they bled. In rural areas a comparison with the way animals were treated came naturally to mind. In 1847 one farmer described how his neighbour kicked and punched a child of twelve and struck him with a whip-handle, all in such “a cruel manner that I thought he was striking an animal rather than his own child.”21 Taken together, these testimonies show that in the general practice of corporal punishment there were certain limits that could not be crossed without incurring the disapproval of friends and neighbours.

Beginning in 1912, the records of the Montreal Juvenile Delinquents’ Court (JDC) allow a glimpse of violence within families. This tribunal, created in 1910, was established to try young people under sixteen who had offended against either the Canadian Criminal Code or a provincial or municipal law, and to do so with no publicity, separately from adults. Parents could also bring before the JDC children they considered disobedient, runaways, incorrigible, or uncontrollable, and ask that under the provincial legislation of 1869 they be placed in an industrial or reform school. In addition to this punitive aspect, the Juvenile Delinquents’ Act of 1908 showed concern for the protection of children in its Section 29, which allowed action to be taken against any adult who committed an act resulting in a child becoming a delinquent, or that neglected some action that would prevent a child from becoming one. In 1912 an amendment was added authorizing the removal from the home of children abused by their parents.

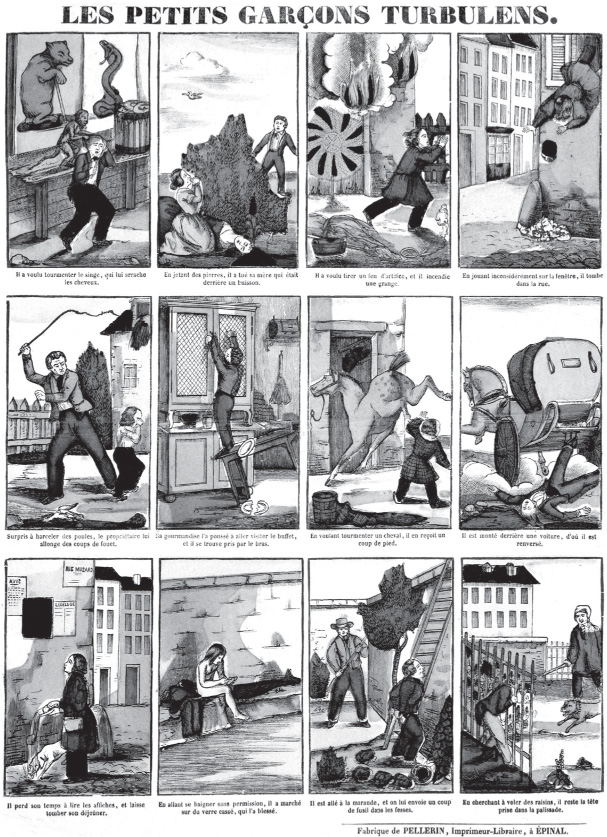

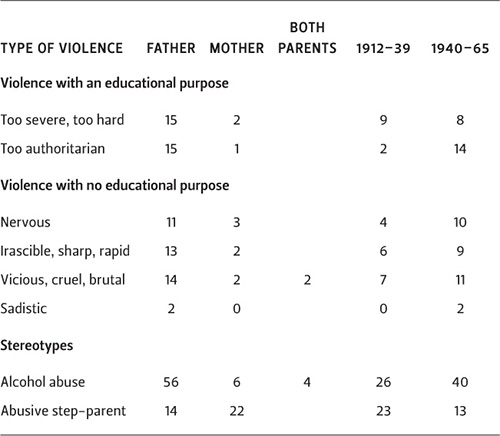

Because this was such an abundant source, we limited ourselves to a sample of fifty cases per decade, between 1912 and 1965 (see Table 6). To avoid repetition, we have provided an overall analysis of the source. Each case began with a “charge and complaint” concerning the behaviour of the child or its parents, and ended with the judge’s decision. Most of these files included a report on the inquiry written by the probation officer, an indispensable aid for the judge.22 These documents were by far the most interesting, especially early in the century. In addition to describing the personal and family circumstances of the child (age, nationality, schooling, religion, father’s occupation, the number of children in the family, income, etc.), it described the problem that had led to the court appearance, followed by comments and recommendations. Sometimes the file also included a medical report and a psychiatric evaluation. This source accordingly lent itself to statistical treatment in addition to the study of individual cases.

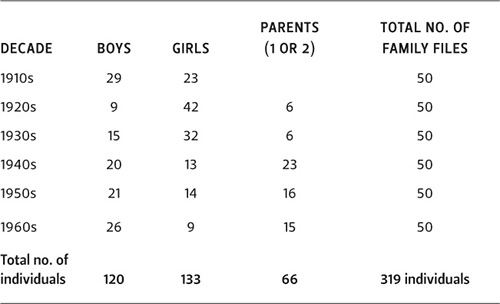

An overall view of the sample shows that during the first three decades most of the children were accused of delinquency, but that subsequently most were depicted as victims of a violent parent (see Tables 7 and 8). In forty-seven of these families the parents were immigrants — a number too small to lend itself to statistical analysis. At most the comment can be made that these families became more numerous during the economic crisis of the 1930s (see Table 9).

Table 6 Distribution of the Files of the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court (JDC) and the Social Welfare Court (SWC), by Sex and Generation, 1912–1965

The total comprises 300 files, representing 300 different families, with 50 being taken from each decade. In constructing the sample, we took for each decade the first 25 files dealing with beaten children, starting with the initial year, followed by the fifth year. The 300 files bear the names of 319 individuals, since more than one name could appear at the top of the document. The 300 family files represent 734 cases of beaten children, since more than one child in the family could have been beaten.

Source: Archives of the JDC and the SWC of Montreal, 1912–65.

Notes: The files of the JDC numbered 1,200 per annum between 1913 and 1931, rising to 2,105 in 1949. Lucie Quevillon, Parcours d’une collaboration: Les intervenants psychiatriques et psychologiques d la Cour des jeunes délinquants de Montréal, 1912–1950, thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree in History, UQAM, 2001, 58.

Other statistical data are as applicable to the 1910s as to the 1960s. For one thing, the families represented in the sample almost all came from very modest backgrounds (see Table 10). Was violence really more common in such families? Not necessarily. First, since probation officers and members of charitable associations were mainly active among poorer families it was easier to observe the violence that took place there. Furthermore, recent studies have concluded that violence takes no account of social barriers, but that outreach workers were more ready to draw attention to cases occurring in the more humble social classes.23 Finally, it is possible that middle-class parents were reluctant to invoke the Juvenile Delinquents’ Act. The novelist Claire Martin relates that her father, a fairly wealthy engineer, frequently beat his children, who were born approximately between 1900 and 1920. The boys ran away more and more frequently, and, around 1930, one set off behind the wheel of his father’s car. The father thought of alerting the police, but his superior (a deputy minister) dissuaded him: “All the same, you’re not going to risk your son’s future!”24

Table 7 Distribution of Children as Delinquents and Victims in the Files of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Source: Archives of the JDC, and the SWC of Montreal, 1912–1965.

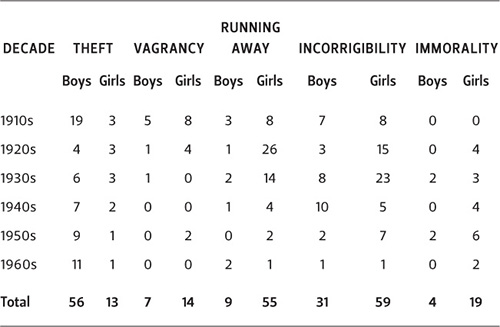

The nature of the charges differed markedly according to the sex of the child, with boys being more frequently accused of theft and girls of running away and immoral conduct. This may reflect differences in behaviour as well as different behavioural norms according to sex (see Table 11). There was considerable variety in the intensity of the violence, which ranged from a mere slap to flogging with a horsewhip (see Table 12). When the punishment was considered moderate and deserved, the investigators said so, which is not the least interesting aspect of these files.

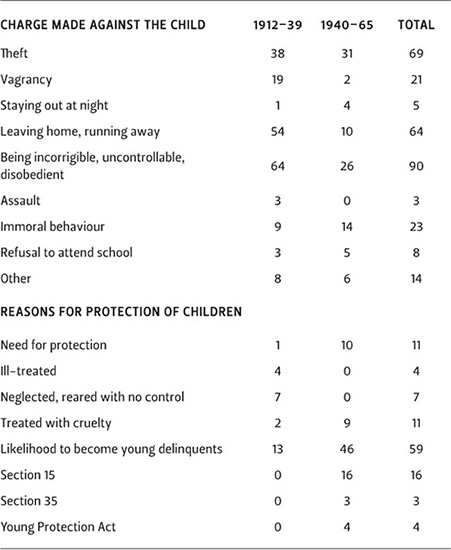

Table 8 Distribution of Grievances Outlined in the Accusations and Complaints Dealt with by the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Source: Files of the JDC, and the SWC, 1912–1965.

Note: Several charges or reasons to protect could appear in a single accusation. This explains why the total exceeds 300.

Table 9 Children of Immigrant Parents by Country of Origin and Period, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

NO. OF FAMILIES |

|

|---|---|

France |

1 |

Belgium |

1 |

England, Ireland, Scotland |

10 |

Russia, Poland, Romania, Lithuania |

11 |

Austria, Hungary, Germany |

7 |

Italy |

11 |

Greece |

1 |

Syria |

1 |

United States |

2 |

Barbados |

2 |

Total |

47 |

B BY PERIOD |

|

1910s |

11 |

1920s |

6 |

1930s |

14 |

1940s |

6 |

1950s |

3 |

1960s |

7 |

Table 10 Occupations of Parents, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

1 Heads of large businesses |

0 |

|---|---|

2 Senior public servants |

0 |

3 Partially indeterminate (1 & 2) |

0 |

4 Small shopkeepers and industrialists |

11 |

5 Local public servants |

0 |

6 Partially indeterminate (4 & 5) |

0 |

7 Business people |

3 |

8 Liberal professions |

3 |

9 Public administration |

0 |

10 Partially indeterminate (7, 8 & 9) |

0 |

11 Middle managers |

6 |

12 Scientists and skilled white-collar workers |

2 |

13 Partially indeterminate |

0 |

14 Office employees, semi-skilled, and unskilled white-collar workers |

6 |

15 Partially indeterminate (11–14) |

7 |

16 Farmers, stock breeders, and similar |

0 |

17 Artisans |

3 |

18 Partially indeterminate (16 & 17) |

0 |

19 Skilled workers |

20 |

20 Tradespersons |

45 |

21 Semi-skilled and unskilled workers |

103 |

22 Manual labourers |

0 |

23 Indeterminate |

5 |

24 Other |

42 |

25 No employment |

1 |

Note: This classification is based on the book by Gérard Bouchard, Tous les métiers du monde: Le traitement des données professionnelles en histoire sociale (Quebec: Presses de l’Université Laval, 1996). The total comes to only 257 because the parent’s occupation was not always mentioned in the files.

Table 11 Distribution by Sex of the Most Frequent Accusations on the Report and Complaint Forms, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

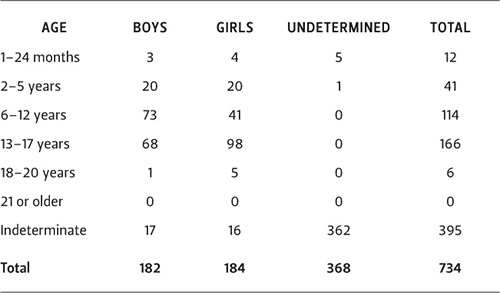

Among the children who suffered violence (in the broadest sense), boys and girls appear in almost equal numbers (see Table 13). Those whose sex was unknown generally came from families in which the father ill-treated all his children equally. The age of the victims tells us much more about the practice of child-rearing. During the preschool years children of both sexes suffered punishment to an equal degree. Between the ages of six and twelve more boys were punished than girls: we can surmise there was mischievous behaviour on the part of the “little fiends,” who were less submissive than their sisters and more likely to try their parents’ patience. But the situation was reversed in the adolescent years. As Carolyn Strange and Tamara Myers have shown, for girls a large city like Toronto or Montreal represented both dangers and opportunities for pleasure.25 Parents, obsessed by fear of a premarital pregnancy or, even worse, by the spectre of prostitution, kept a much closer watch on the activities of adolescent girls than on their brothers of the same age. To avoid a stain on the family’s honour they were prepared to resort to harsh measures such as beating or a request for detention in a reform school.26 Finally, it may seem surprising that infants of under twenty-four months appeared so rarely in the records. This can be explained by the facts both that doctors did not yet possess the necessary means to identify accurately the cause of injuries to these little ones and that the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court dealt mainly with adolescents.

Table 12 Types of Violence Described in the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

GENERAL |

|

|---|---|

Beatings |

71 |

Cruel beatings |

15 |

Brutal beatings |

21 |

Severe beatings |

3 |

Hard beatings |

2 |

Violence |

2 |

Correction, corporal punishment |

5 |

Excessive correction |

2 |

Wrongful beating, for no reason, without cause |

7 |

Abuse, ill-treatment |

8 |

Assault |

1 |

Striking |

6 |

Spankings |

8 |

Volleys of blows |

2 |

“Raising a hand” |

1 |

BLOWS WITH THE BARE HAND |

|

Slaps |

1 |

Boxing on the ear, cuffs |

3 |

Raps |

13 |

Slaps in the face |

17 |

Slaps on the head |

13 |

BLOWS WITH AN OBJECT |

|

Stick |

17 |

9 |

|

Various objects |

13 |

Horsewhip |

2 |

Whip |

7 |

Switch |

1 |

Hose |

2 |

Strap, belt |

30 |

VARIOUS FORMS OF ILL-TREATMENT |

|

Kicks |

27 |

Punches |

28 |

Pulling hair |

9 |

Pulling ears |

2 |

Gripping the throat, choking |

5 |

Squeezing the arms |

2 |

Biting |

3 |

Pinching |

3 |

Scratching |

3 |

Blow causing a nosebleed |

1 |

Throwing an object (dish or utensil) |

5 |

Throwing a child against the wall |

1 |

Throwing children in the river |

1 |

Breaking an arm |

1 |

Maiming a child |

1 |

Table 13 Distribution of Beaten Children, by Age and Sex, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Note: The total exceeds 300 because more than one child could be beaten in the same family.

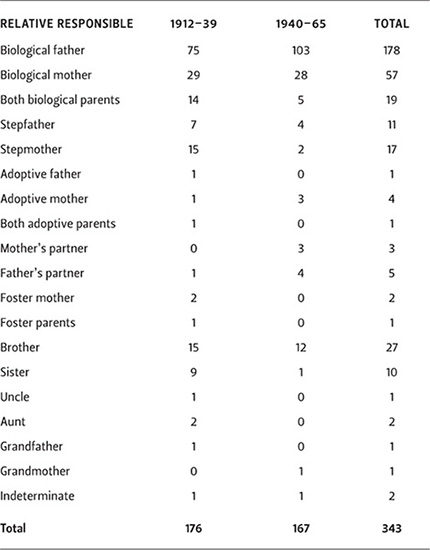

In the majority of cases it was the biological father who beat the children, whatever their age or sex (see Table 14). Husbands were three times as likely as wives to act in this manner. This corresponds to the situation described by Lionel Groulx in 1923: in traditional French-Canadian families it was the father who took responsibility for enforcing discipline, using a switch if necessary.27 Anne-Marie Sohn found the same in France: “When corporal punishment is used, it is more usually paternal rather than maternal. On this point folklorists, sociologists, and the archives are in complete agreement.”28 The role of disciplinarian played by fathers exposed them more often than their wives to accusations of abuse. Among the families in our sample, twenty-four men and just one woman were sentenced to prison, whether by the juvenile court or another tribunal, for brutal treatment of their children. In blended families, on the contrary, violence was more often attributed to stepmothers than to stepfathers.

Table 14 Family Members Who Beat the Children, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Note: The total exceeds 300 because more than one individual could strike the children in a single family.

The motives invoked by parents in justifying their actions varied depending on the sex of the child. Boys were mostly accused of theft (more or less serious), while girls were beaten more often than their brothers for leaving the house after this had been forbidden (see Table 15). But violence could also have its source in the parents’ personality, and the probation officers’ perception of it evolved over more than fifty years. These two factors have to be taken into account if we wish to reach a proper understanding of the various types of parental violence (see Table 16).

In carrying out the initial investigations into juvenile delinquency in Montreal in the 1910s, probation officers discovered that violence was common in these families. In the first place, this was due to the difficult living conditions of the labouring classes. As Émile Zola depicted masterfully in his novel Germinal, and as the historians John Bullen and Bettina Bradbury have shown for nineteenth-century Canada, children’s wages, however modest, were indispensable to working-class families. They allowed families to escape poverty or to raise their mediocre standard of living, as Bettina Bradbury has pointed out.29 This even caused some parents to take their children out of school at as early an age as eleven or twelve so that they could work and contribute some additional income.30 While admitting the need for this, probation officers found that parents sometimes went too far, especially those who forced their little girls of eight or nine to sell newspapers in the streets despite the winter cold, threatening to beat them if they lost any money.31

On the other hand, the big city offered children many temptations: cigarettes and candies for sale in the corner store and the “moving picture shows” that probation officers saw as a real passion. To afford such pleasures some would steal small sums from their parents.32 The reaction of the latter was, at least in part, explained by their financial situation. Even the better-off might have feared that their son was a budding thief, starting by taking pennies from his parents, moving on to shoplifting, and finally burglary.33 But also, when parents were earning only $1.25 a day as day labourers or house cleaners34 such petty pilfering had a substantial impact on the family budget. This explains the harsh punishments administered in working-class environments: one impoverished mother denounced her ten-year-old son to the juvenile court for having stolen various sums totalling around fifty cents, while a longshoreman flogged his son whom he suspected of having stolen $10 from a lodger in the home.35

Table 15 Distribution by Sex of the Causes of Parental Displeasure According to the Reports of Probation Officers, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912-1965

BOYS |

GIRLS |

|

|---|---|---|

Theft |

69 |

23 |

Truancy |

24 |

22 |

Housework |

2 |

13 |

Control of wages |

6 |

8 |

Lack of respect |

1 |

5 |

Going out |

15 |

43 |

Note: These data differ from those in Table 11 because the probation officers’ reports contained more varied information than appeared on the denunciation and complaint forms.

Preoccupied by the cares of daily survival, many parents did not have the leisure to find ways to settle problems with their children except by beating them. During the earliest years of their activity probation officers accepted this violence as a fact of life. Like several of their contemporaries (educators, judges, journalists) they believed that some children had “vicious instincts,”36 so they tended to approve of harsh punishments. For instance, Marie Clément (the first female probation officer) wrote about Jeanne, a sixteen-year-old: “The child has a nasty expression, will not listen to her parents, is disrespectful, never wants to attend school, does not want to do anything in the home, and only wants to roam the streets and go to the moving pictures. Her exasperated parents have been driven to violence, striking her with a hockey stick.”37 This way of expressing it suggests that the probation officer did not blame the parents very much, and did not take seriously the adolescent’s claim that she “believed she had always been ill-treated.” Likewise, in the case of Peggy, aged fourteen, Marie Clément noted: “She escapes her parent’s surveillance and she misbehaves. Lately, after what may have been rather brutal punishment, she ran away from home.”38 Once again the probation officer is less concerned about the punishment, which she simply finds may have been rather brutal, than about the behaviour of the girl, who had ended in a house of prostitution.

Table 16 Distribution of Types of Violence by the Sex of the Parent and by Period, from the Records of the JDC and the SWC, 1912–1965

Note: For the first six categories we have avoided duplication by listing only the dominant character trait of the abusive parent. However, there is some duplication in the last two categories.

In addition to this kind of violence intended to teach a lesson, probation officers had to deal with cases that they described as ill-treatment and that closely resembled those described in separation cases. First there was violence due to alcohol. The file on Odilon, from 1912, reveals as much about the situation itself as about the reaction of the probation officer. The parents (the father was a carter and the mother a daily domestic helper) appeared to be poor citizens and alcoholics who fought frequently. The father, who had previously spent nine months in prison, beat his children brutally, causing them to run away. The eldest, aged thirteen, led on his younger siblings, played hooky, and smoked cigarettes. The investigator had no illusions about the parents’ motivation: “It appears that it is mainly to be rid of their child rather than to protect him that they have brought this matter to court.” But he was scarcely more indulgent toward the child: “The little boy is certainly vicious, badly brought up, and seems quite intelligent, but it is easy to see that he is the child of alcoholics.”39

The animosity of a step-parent toward a child of a first marriage also attracted the attention of outreach workers in the field. Augustin’s file, from 1916, provides a typical example. His father accused the boy of being “a runaway, a thief, a liar, stubborn, disobedient, incorrigible, and uncontrollable.” The parish priest confirmed these accusations: Augustin had “a two-fold passion for stealing and running away. Please help this good father who is most distressed to see his child like that, but who is most determined to try to save him.” After making enquiries the probation officer told a different story: “This child has a stepmother who ill-treats him. I am informed of this by trustworthy people. In my opinion the child runs away so often out of fear of the mother.”40

A third form of ill-treatment observed by probation officers was extreme punishment causing injury. In 1919, a man complained about his runaway fifteen-year-old, but the latter responded by accusing his father of flogging him often with a whip. In fact, the injuries to his legs that had been noticed on his arrival at the detention centre proved the truth of his claim.41

Whether it was a matter of deserved punishment (according to the parents and sometimes the probation officer) or ill-treatment (according to the child and witnesses), these acts of violence often produced the same result: running away from home, or “desertion,” to use the terminology of the day. Probation officers quite soon became aware of this cause-and-effect relationship. Following the cases of Odilon (aged thirteen in 1912) and Augustin (aged ten in 1916), they noticed that after the age of eight a child might seek salvation in running away, like little Alphonse. His parents described him as sly, stubborn, disobedient, thieving, and lying. “His greatest vice is deserting from home,” wrote the probation officer. “I believe this is because the parents punish him too physically, he gets far from them to avoid being beaten.”42

Probation officers noted another consequence of violence: it worsened the character of certain children. Antoine, aged fourteen, had a “formidable drinker” for a stepfather. Marie Clément wrote in her report, “The mother claims that her son has become coarse and rough since his stepfather has been ill-treating him.”43 The use of the word “claims” seems to indicate that the officer did not entirely accept this explanation. Her colleague, J.-E. Tétrault, was more sympathetic toward Léon Lemire, aged ten, whose mother had accused him of stealing 50 cents. “The child seems to me to have been raised very harshly and even beaten for no reason, which has inclined him to be cantankerous and aggressive.”44 There seems therefore to have been very little difference between ill-treating a child (like Antoine) and bringing him up very harshly (like Léon), but in each of these cases the probation officers considered that treatment of this kind only worsened the child’s disposition. These observations concur with the opinion expressed by an educator as early as 1858, as well as with the results of the most recent studies.45

While probation officers were discovering the undesirable consequences of violent parenting, Father Boncompain continued to preach the advantages of the whip in obtaining the obedience of adolescents. “Severity is necessary, otherwise you will be led by the nose,” he wrote in 1918. It is true that he also advised against treating a child harshly, for that would make him deceitful, lying, or rebellious. But how could the balance between love and the fear that he recommended be maintained?46 Where should the boundary be set beyond which punishment became so harsh that it aggravated existing problems?

To explain the most serious problems, doctors, like probation officers, hesitated between the influence of the environment and the existence of vicious instincts. The latter explanation is reminiscent of the theory of degeneration that dates from the nineteenth century but which still permeated psychiatric thinking in the early twentieth century.47 The story of Odilon, mentioned above, was a good illustration of this, as was that of Estelle, aged ten in 1912. Estelle was two years old when her father was sentenced to ten years for ill-treating his wife and two children. All three bore the marks of the father’s brutality. Since the mother was dying, the baby was entrusted to the Grey Nuns, and Estelle was adopted by a cleaning woman. Even though she was well cared for, the little girl developed the habit of stealing things from the house of her adoptive mother to give to her playmates. Sent to boarding school, she tried to set fire to the house and was later expelled everywhere she went because the nuns found her uncontrollable. “She is vicious by temperament and atavism,” concluded Marie Clément. A medical report contains a description of her fits: “The child seemed to be in the grip of some great terror, cried out, threw things, and seemed to have no awareness.” Despite her adequate intelligence, she was unable to pay attention. The doctor believed that because of these “delirious manifestations” and her bed-wetting she was “a probable case of epileptic derangement.” Another doctor noted “a certain degree of intellectual weakness and instinctive moral perversion, resulting from an incomplete development of her intelligence and moral and affective faculties.”48 Both doctors advised that she be interned in an asylum, so she was sent to Longue-Pointe. Neither of them saw a link between the fear manifested by the little girl during her fits and the fear she must have felt when her father brutalized her. But starting from such tentative beginnings doctors would eventually reach a better understanding of the psychosomatic disorders caused by violence against children.

While probation officers were accumulating observations and reflections that served to enlighten judges but that then remained buried in the archives, journalists were revealing the existence of “child martyrs” to the public.

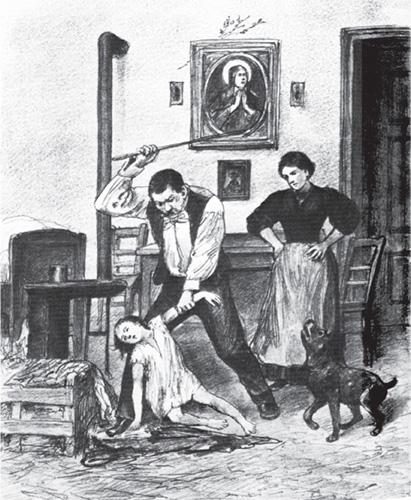

The phenomenon of children abused and even killed by their parents has no doubt existed in every period, but it was only in the second half of the nineteenth century that there was any talk of “child martyrs.”49

The expression first emerged in a medico-legal study by the forensic physician Ambroise Tardieu, who was describing the abuses inflicted on children whose lives were no better than “a long martyrdom.”50 Subsequently, the expression became a journalistic and literary concept that awakened the sensitivity of the public just when the mass circulation newspapers were coming into existence in France. An illustration entitled “The Child Martyr” showed a father using a stick to beat a very young child who is about to lose consciousness (see Illustration 6). In his novel L’Assommoir Émile Zola described the “martyrdom” of little Lalie Bijard, beaten to death by her father, a drunken Parisian labourer. This novel, initially published as a serial in 1876 and as a book the following year, marked the start of a public opinion campaign that resulted in the adoption in 1889 of a law to protect abused children.51 That same year Great Britain passed the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act. The same concern to protect children manifested itself in the United States, where historians date from 1874 the first “recorded case of child abuse.”52

Illustration 6 The Child Martyr, 1877

Source: Paris, Bibliothèque nationale. Illustration reproduced in Michelle Perrot, ed., Histoire de la vie privée, vol. 4, De la Révolution à la Grande Guerre (Paris: Seuil, 1987), 278.

In Quebec, the expression “child martyrs” first surfaced in 1885 in the account of a trial that took place in France.53 The expression came spontaneously to the minds of writers in Catholic countries, who were accustomed to religious images, while it was used less frequently in the Anglo-Saxon countries with their Protestant culture.54 Thus, Zola spoke of the “flesh of the martyred innocent” in writing about little Lalie: “In churches people worship female saints being scourged, their nudity less pure than hers.”55 Later a Quebec journalist would make the same comparison about a child of two years: “Over his grave might be written: ‘Here lies a true angel. He was an angel in his innocence, and a martyr in the suffering he endured.’”56 The stress placed in this way on the innocence of the victim underlined the difference from punishment incurred by rebellious children. This difference was significant at the time, for even judges would not hesitate to recommend a flogging, though a moderate one, to eradicate children’s vicious tendencies.57

But did contemporaries who were accustomed to parental severity perceive this distinction? In his autobiographical novel published in 1879, Jules Vallès blamed his parents not only for having brought him up too strictly but also for having allowed a neighbour to “martyrize” his little girl of ten. “They would tell her she should not misbehave and cause distress to her father”!58 The writer’s parents therefore considered the countless beatings that caused the death of this child to be well-deserved punishments.

The theme of the child martyr, so frequent in French newspapers,59 also appeared in the Quebec press, in both serialized novels and news reports. Among the former was Le Nid vide, which appeared in La Presse in 1900 and told the story of a little girl kidnapped by street performers and ill-treated by a female member of the troupe.60 Where news reports were concerned, a survey of three newspapers from between 1870 and 1919 allowed us to identify fifty-three genuine cases, reported by journalists, involving fifty-nine abused children and the same number of abusers (see Table 17).61 Ten of these reports used the expression “child martyr.” The children were equally divided between the two sexes (twenty-three boys, twenty-three girls, and thirteen whose sex was not indicated), with a median age of ten — exactly the age of “Aurore, the Child Martyr” (see Chapter 3). The injuries they sustained had left marks (bruises, burns, and fractures) and caused the deaths of six of them (see Table 18). The journalists, who found most of their information in police stations or the courts, mostly described incidents that occurred in Montreal (thirty-two) and a few (nine) in the rest of the province, in Ontario (four), and in France (one).62 The stories became known either because of an intervention by neighbours (sixteen cases), family members (five cases), or other individuals, or because the child itself made a complaint to the police.

Four of the victims were orphans or destitute, recruited in England by philanthropic societies and placed in Canadian families. The youngest were adopted, while the oldest were bound by an employment contract that provided for a wage. But the difference between the two situations was far from clear, and all were required to do as much work as their strength allowed.63 “When you’re paying, you want value for your money,”64 said one farmer’s wife. One can imagine the abuses to which such a system was prone: cases were found almost everywhere in Canada of undernourished, poorly clothed, overworked, and beaten children. After one death, the woman responsible for the region of Montreal declared, “Really there have been so many cases of ill-usage in the past that it would occupy the judges fully for quite a while if they could all be raked up.”65

The accused, like those who appeared before the Juvenile Delinquents’ Court, were almost all from modest backgrounds.66 In one case, however, the reporter pointed out that “the father is one of the most prominent citizens of Chicoutimi,”67 showing that abuse was nevertheless not restricted to the working class. The aggressor was usually the father rather than the mother, except when step-parents were involved: there were eight stepmothers and two stepfathers. The majority of abusive adults were males: thirty-seven men and twenty-one women (see Table 19). Among the accused, five were acquitted for lack of sufficient proof, sixteen were found guilty, and the outcomes of twenty-two other cases are not known. The sixteen known sentences range from a simple fine (six cases) to life imprisonment.68

The total number of these articles, which varied in length, was not large enough to allow us to make a very refined statistical analysis of the abuses inflicted on children, but it does make it possible to study the way in which journalists treated their information, the popular reaction, and that of the judges, as well as the measures taken to protect the children.

In treating the subject of physically abused children, journalists were trying to capture their readers’ attention and play on their emotions rather than to inform them, hence the choice of sensational phrases and headlines such as “incredible barbarism,” “unparalleled cruelty,” “unnatural parents,” etc. The adjectives “heartless” and “brutal” were applied to men, while the women were described as “wicked stepmothers,” “viragos,” and “tigresses.” The latter were also frequently referred to as “the … woman,” as in “the D. woman” or “the B. woman,” a formula that has no masculine equivalent. Along with others, this points to the fact that violence toward children seemed worse if a woman was responsible.

Table 17 Age Distribution of Abused Children, from Quebec Newspaper Reports, 1870–1919

NO. OF CASES |

|

|---|---|

19 years |

1 |

17 years |

1 |

15 years |

1 |

14 years |

2 |

13 years |

2 |

12 years |

3 |

11 years |

2 |

10 years |

8 |

9 years |

2 |

8 years |

1 |

7 years |

4 |

6 years |

2 |

5 years |

1 |

4 years |

1 |

2 years |

1 |

25 months |

1 |

20 months |

1 |

4 months |

1 |

Not indicated |

24 |

Total |

59 |

Sources: Montreal Star, 1870, 1873, 1880, 1883, 1893, 1903, 1913, 1923; La Presse, 1886, 1890, 1896, 1900, 1906, 1910, 1913, 1916, 1920, 1926; and La Patrie, 1880, 1885, 1890, 1895, 1900, 1910.

Table 18 Harm Inflicted on Abused Children, from Quebec Newspaper Reports, 1870–1919

NO. OF CASES |

|

|---|---|

Burning |

2 |

Scalding |

2 |

Exposure to cold |

4 |

Kicking |

4 |

Punching |

8 |

Beating (stick, rod, ruler) |

5 |

Beating (whip, horsewhip, strap) |

4 |

Striking |

1 |

Pulling ear |

1 |

Striking and beating |

18 |

Ill-treatment |

13 |

Beating, brutality, cruelty |

3 |

CONSEQUENCES |

|

Death |

6 |

Broken leg |

2 |

Broken arm |

1 |

Twisted legs |

1 |

Sources: Montreal Star, 1870, 1873, 1880, 1883, 1893, 1903, 1913, 1923; La Presse, 1886, 1890, 1896, 1900, 1906, 1910, 1913, 1916, 1920, 1926; and La Patrie, 1880, 1885, 1890, 1895, 1900, 1910.

Table 19 Aggressors of Abused Children, from Quebec Newspaper Reports, 1870–1919

Father |

25 |

|---|---|

Mother |

6 |

Stepfather |

2 |

Stepmother |

8 |

Teacher |

6 (5 men, 1 woman) |

Adoptive parents |

2 couples |

Adoptive father |

1 |

Foster mother |

2 |

Grandparents |

1 couple |

Uncle |

1 |

Aunt |

1 |

Not specified |

1 |

Total number of aggressors |

59 (37 men, 21 women, 1 not known) |

No. of stories published |

53 |

No. of beaten children |

59 |

Note: It is by pure chance that the total number of aggressors is equal to that of the abused children. In fact, a child could be beaten by more than one person, and a family could include several abused children.

Sources: Montreal Star, 1870, 1873, 1880, 1883, 1893, 1903, 1913, 1923; La Presse, 1886, 1890, 1896, 1900, 1906, 1910, 1913, 1916, 1920, 1926; and La Patrie, 1880, 1885, 1890, 1895, 1900, 1910.

To bring out the unusual nature of the offence, journalists stressed the immigrant status of certain accused. Numbering seven among the forty-one cases occurring in Quebec,69 they were over-represented, for in 1921 only 4.9% of the population had an ethnic origin other than French or British.70 Were the customs of these immigrants, especially those from Eastern Europe, really harsher than those of the French Canadians or North Americans of Anglo-Saxon extraction? The recollections of Maxim Gorki and some novels by the Comtesse de Ségur,71 both born and raised in Russia, seem to confirm that this was the case. What is certain is that the Montreal journalists never missed an opportunity to point to the barbarity of these foreigners. They wrote, for instance, about a “Pole, a brute with repugnant features, accused of having beaten his child ferociously.” And during the trial of Anna D. (the first name is fictitious), a Polish immigrant, they referred to the “sad state of affairs existing among a certain class of immigrants. They originate from the dregs of society in the country of their birth or are of a crass ignorance bordering on criminality.” Another article bore the ironic heading: “Russian Customs: A Practical Way to Punish Children.” It described the father “gripping one of his children aged twelve by the throat and striking him in the face with his fist, while his nineteen-year-old son held him by the legs and joined in beating him.” This father later explained to the judge that “in his country that was how bad people were punished.”72

Nevertheless, most of the accused were French or English Canadians. In their case the journalists tried to explain their aberrant behaviour by attributing it to mental illness, anger, a “temporary derangement,” or drink, “which makes a man resemble a beast.” The “T. woman,” accused of ill-treating the children from her husband’s first marriage, was described as “suffering from delirium” and “raving mad.”73 The “prominent citizen” of Chicoutimi who burned his child’s hands to the bone was suffering from “a fearsome anger.”74 As for excessive drinking, it was an accusation levelled at more than a third of the fathers accused of brutality (nine out of twenty-five). When none of these explanations applied (as in the case of a female prisoner who held her child by the legs in order to fracture its skull against a wall),75 they spoke of “unnatural parents,” “monsters,” or “barbarians.” In short, as the sociologists Gelles and Straus would later discover, the reporters believed that abusive parents were not normal people76 or that at least they were not of sound mind when they acted in such a way.

Journalists did not attach the same importance to all the cases brought to their attention. For instance, stories about brutality committed by drunken fathers, even though frequent, invariably merited only a brief mention. Other judiciously chosen cases, however, were given coverage that could last for days or even weeks.

In 1890, an early case considered worthy of interest involved Margaret B., an orphan of sixteen who had come from England and was “cruelly ill-treated” by the farming couple to whom she had been entrusted. In imposing a fine on the guilty parties, the Montreal Recorder insisted on the duty of magistrates to protect children brought from overseas by charitable organizations for, if they were ill-treated in Canada, “we will look like savages.”77 This remark shows why the judge and journalists paid special attention to this case: the reputation of Canadian society was at stake.

Six years later another case made the headlines. A grandmother, Mme B., was accused of having inflicted “atrocious tortures” on her grandchildren. These, a girl of ten and a boy of fifteen, listed the abuses they had suffered: beatings with a stick, pricking with pins, and rotten food. The grandmother also forced the little girl to stand in front of an open window wearing a wet dress, exposed to the winter chill. She also drew a cord tight around the girl’s tongue until it was swollen. As for the boy, she forced him to go barefoot into the winter snow with the result that he was frostbitten and five of his toes had to be amputated. Since the doctor and a neighbour confirmed the children’s allegations, the judge condemned the woman to life imprisonment.78 In this case it was the unusual character of the punishments conceived by the grandmother that aroused the curiosity of the huge crowd that filled the courtroom.

The case of Anna D. surpassed all previous ones in its scale. This Polish immigrant, the mother of two children born of a first marriage, was remarried to a widower who had two sons from a previous marriage, aged thirteen and two. A third child was born of the second marriage. When the little two-year-old boy died suddenly on 17 July 1906 and the doctor refused to sign the death certificate, the stepmother fled, which looked very much like an admission of guilt. La Presse immediately spoke of a “marâtre,” and a “child martyr,” and called for a “punishment to serve as an example to all cruel stepmothers” should she be found guilty.79

During the autopsy, the doctors discovered that little Jan had nine broken ribs and a great number of internal lesions that were the cause of death. At the coroner’s inquest a witness claimed to have seen the stepmother kicking and striking the child with her fist.80 The “D. woman,” having been found by the police, was subjected to a preliminary enquiry. She entered the courtroom wearing a “sad, resigned” expression, carrying her infant of a few months in her arms. While the witnesses were being heard she clenched a medal in her fist and her “red lips moved gently as if in a silent prayer.”81 The journalists immediately changed their tone. Though they had seemed so sure of her guilt at the start of the inquest, now they wrote:

The D. woman … won the sympathy of the public when she appeared in the dock. She was holding a very young infant in her arms. Her bearing and physiognomy were far from giving the impression that everything that has been said of her, depicting her as a cruel stepmother, was truthful enough to survive the test of cross-examination under oath.82

When the trial for murder began before the Court of Assizes, reporters noted that “the accused had a modest appearance and features in which one could discern total frankness” — and she continued to cradle her baby in her arms. Some of the evidence was favourable: a neighbour stated that the two-year-old child was malformed; her husband stated that little Jan had fallen from the balcony a few days before his death, an excuse that would be invoked in many other cases of suspicious death. Another witness declared he had been mistaken in his evidence before the coroner’s inquest. The lawyer for the accused set out to show that the child had died as a result of his fall on the steps. Then he delivered an eloquent speech for the defence, drawing tears from several jurors and a number of persons in the room with its “supremely pathetic” conclusion. In the end the jury found the accused guilty of manslaughter, she was condemned to three years’ imprisonment.83

The interest of this case consists in the reversal of opinion that took place among the journalists and public as soon as the accused appeared in court with the baby in her arms. This picture of motherhood, more powerful than all the evidence, aroused widespread feelings of pity. Henceforth the expressions “wicked stepmother” and “child martyr” would be banished from the newspaper. The sight of a young mother cradling her infant was incompatible with the image of the cruel stepmother, which explains the verdict and the relatively lenient sentence. Several decades later, the sociologist Richard Gelles would explain how the outreach workers allowed themselves to be influenced by their stereotypical notions of abusive parents.84

“The death of a child as a result of ill-treatment arouses a wave of indignation and cries out for vengeance,” wrote one journalist early on in the Anna D. affair. The judges sometimes shared this indignation and some of them made very harsh statements, notably Judge Robertson in commenting on the actions of Mme B.: “It is one of the most revolting crimes, the most diabolic, of which a woman can be accused.” To the S.-J. couple, accused of having shut up their child in a shed in December in addition to beating him, the judge declared, “It is an atrocity with no name. You are not worthy to live among human beings. Civilized people would never do such a thing.” On two occasions the judge went as far as to tell the accused that their unworthy conduct cried out for revenge.85

Yet the civil and criminal laws in effect in Quebec granted parents and teachers the right to administer “reasonable” punishment to the children in their care. Judge Loranger established initial criteria for what was “reasonable” in 1864, during a civil trial involving an elementary school teacher who had beaten a six-year-old pupil, but the same criteria were applicable to parents. Corporal punishment, said the judge, should only serve an educational purpose and “correct unruly children,” and should not be motivated by “arbitrariness, whim, anger, or ill-humour.” It should, furthermore, be proportionate to the “nature of the offence and the age of the pupil,” and not result in any danger to the child’s health.86

Judges in Montreal based themselves on the same criteria. They considered punishment unacceptable if it risked harming children’s health, such as exposing them to cold in the depths of winter or hitting them hard enough to draw blood, especially on the head. In judging the D. couple, accused of ill-treating Margaret B., the Recorder allowed them a similar authority to that of parents, but added that they did not have the right to abuse it. Since the little girl had bruises on her body and a head wound caused by “the virago with whom she was in service,” the judge considered it obvious that brutal treatment had taken place. He therefore sentenced the couple, hoping that it would serve as “a good lesson for those who are in the same situation.”87

Was punishing the guilty enough to ensure that children were protected? Clearly not: the sentencing of the D. pair in 1890 did not prevent the death of another young immigrant sixteen years later in similar circumstances, when his employer (or adoptive father) would be accused of manslaughter.88 The Society for the Protection of Women and Children of the City of Montreal, founded in 1882, set out to prevent such tragedies. It had brought eight of the cases that occurred in our sample to the attention of the courts. Occasionally the Salvation Army intervened in the same way.

The D. case gave the judge the opportunity to remark that instances of cruelty toward children were unfortunately more numerous than people believed, an observation repeated the very next day by a journalist.89 Among the cases that remained hidden, those concerning babies aged under two were perhaps the most frequent. Our sample contains only two of these, and this is certainly because of the difficulty at the time of correctly identifying the causes of their deaths. For instance, we did not see any mention of radiography (then a very recent technique) to detect fractures in children who were believed to have been abused.

Other causes of death were even more difficult to verify, as in the case of the child of F.R. Before his death a friend of the mother had warned the police that the father ill-treated his little boy because he suspected the child was not his. As the boy was dying his mother told Dr Paquet that her husband had forced her to wean the baby and that he had fed it a gruel that made it sick. When the four-month-old vomited the father held it up by its feet, head down, and struck it. The mother, who was herself often beaten by her husband, did not dare to intervene.90 After the child’s death, the doctor declared that its body was covered with bruises and that a crime had been committed. But a second doctor who had also attended the child told the coroner’s jury that he had never noticed any traces of violence on the body, and the assistant coroner declared that these marks were simply signs of death seen in cases of anaemia in very young children. The inquest ended with a verdict of “death from general debility,” and the journalist concluded from this that “this whole story was nothing more than women’s gossip.”91

Older children were more likely to survive. Some ran away from a home where they were ill-treated and themselves lodged a complaint with a police station or a charity. Such was the action taken by Michel B., aged fourteen. After the death of his father, ill-treatment by his stepmother caused him to leave Hamilton and come to Montreal, where he sought refuge in a police station.92 Margaret B. acted in the same manner.93 Among the nine children who chose to run away, all those whose age is given were between twelve and fifteen — in other words, of an age when many poor children began to work outside the home.94 This was also the age of Marie-Jeanne Gagnon, Aurore’s sister, at the time of her parents’ trial.

Younger children did not dare to leave the family home, both because they did not know where to go and because they were unaware of their rights. For instance, little Philéas S.-J., aged seven, was astonished to learn that his father and stepmother had been imprisoned for ill-treating him.95 It also happened that a child would deny having been subjected to ill-treatment out of fear of the abusive parent. Mme B.’s granddaughter, aged ten, did not dare inform the doctor that her grandmother had ill-treated her because she was afraid of being beaten afterwards.96 The denial was even more obvious in the case of young C. His father had struck him in the middle of the street, attracting a crowd of onlookers. During the trial that followed, three witnesses described the scene, but the accused denied everything and “young C. assured, speaking like a parrot, that his father had not struck him with his fist.” A perspicacious reporter commented that the boy seemed to be inspired by fear of his father’s authority.97

Interventions by neighbours, despite their frequency, did not always meet with success. Anna D.’s neighbours had often warned the father that his wife ill-treated his son, but never managed to convince him.98 And when a boarder at Mme K.’s house tried to interfere on seeing her beat her child two or three times a day, she was told to mind her own business or look for somewhere else to live.99

When a parent was found guilty and sentenced, what became of the children? Three ended up in a reform school or some charitable establishment (notably the little S.-J. boy, who declared he was quite happy to go to live in a nice warm school). Six were placed in foster homes in the hope that they would be better treated there than in their previous homes; Margaret B. was among them. It seems that the others were left with their families, and one has to wonder how brutal parents would have treated them after their release.

The judges and reporters who waxed indignant at the ill-treatment inflicted on children never questioned the principle of corporal punishment. Yet the link between the two is evident in at least a dozen cases. It was to punish her nephew who was making too much noise playing with his friends that his aunt threw boiling water over him.100 It was to punish his five-year-old son who had set fire to a mattress while playing with matches that the citizen of Chicoutimi burned his hands to the bone.101 The judges considered these deeds to be absolute abuse, like blows and kicks. One of them expressed a warning against the abuse of authority, but none questioned parents’ right to punish.

Were parents acting in good faith when they punished their children so harshly? In certain cases the journalists and the judge were outraged at the indifference and harshness of the accused, like the Frenchman who thrashed a child until its blood ran but told the court that the beating he had given as a punishment was not severe enough to do any harm.102

Some parents were unable to grasp the meaning of the word “reasonable” as applied to their right to punish, and could imagine no alternative to a beating to teach a child a lesson. J.C., who was condemned to a fine of $10 or a month in prison for repeatedly punching his son, swore that he would never again punish his child, even if the latter was to end as a criminal.103 Like the parents described by Louis Fréchette he was expressing his conviction that failing such a recourse the child would inevitably go to the bad.

___________

In Quebec, like in France and other countries, in the second half of the nineteenth century society discovered the existence of abused children. Journalists’ insistence on blaming drunken fathers, wicked stepmothers, and brutal immigrants helped to perpetuate myths that were destined to last until they were castigated by sociologists in the 1970s.104 Journalists also revealed the consequences of excessively severe punishment. However, they depicted those responsible as monsters or unnatural parents. This powerful stigmatization led to some perverse consequences, as has been pointed out by Catherine Rollet, including allowing parents to believe that they had nothing in common with the monsters depicted in the newspapers, and making it more difficult to understand the link between corporal punishment and abuse.105 Even judges, officers of the juvenile court, and the members of the society for the protection of children, though better placed than anyone to observe these problems, were satisfied to deplore abuses without questioning parents’ right to use physical punishment. That this kind of punishment could have an effect contrary to what was desired would soon be discovered by the officers of the juvenile court, but the reports that they wrote remained sealed, and so could not be used to enlighten public opinion.

The major daily newspapers like La Presse and La Patrie mostly reported cases that occurred in Montreal. In this way they helped to create the impression that the phenomenon of family violence was restricted to urban dwellers, the working class, and the poor. In fact, however, city children benefited from a degree of protection because of the proximity of neighbours who would sometimes intervene on hearing their cries, and also thanks to the societies for the protection of children that operated in major centres such as Montreal and Ottawa. Yet this protection had its limits. In particular it was of little use to babies because of the lack of effective ways to diagnose the cause of their deaths. And above all, in a society in which working-class life was extremely hard, in which it was considered normal to start working for strangers at as early as twelve, and even sooner in the case of young immigrants, excessively harsh punishments were very likely to pass unnoticed among the other forms of suffering inflicted on these children. As Ian Hacking has noted, cruelty toward children was just one among many forms of cruelty.106

The picture of the “child martyrs” painted in newspapers and novels did however awaken the sensibility of the public. In 1900 Louis Fréchette could cast a critical eye on the harshness of the parenting methods prevalent fifty years earlier and denounce the deeds of certain elementary school teachers, while failing to recognize that it was possible for parents to treat their children with equal cruelty.