In the closing decades of the nineteenth century, thanks to mass circulation newspapers, the public discovered the phenomenon of abused children. To appeal to readers’ emotions, French journalists and novelists of the time used the term “child martyr.” In Quebec, starting from 1920, newspapers and popular literature endowed the Gagnon affaire with such resonance that the name Aurore came to evoke the concept of a “child martyr.”

After World War II the mass circulation press underwent a remarkable upsurge in Quebec before giving way to television during the 1960s. Among its reports the popular press continued to report stories of abused children.1 In 1953, anticipating that the readership would be significant enough to ensure the success of a tabloid devoted to criminal matters, Allô Police decided to specialize in the field. It aimed not so much to inform its readers as to arouse them emotionally, hence its preference for sordid, bloody stories, sensational headlines, photographs of corpses, and repulsive drawings that filled entire pages. The style matched the pictures: “Readers, do not faint at what you are about to read below,”2 warned the author of the first article, which dealt with an abused child in Quebec. More than once public figures criticized the publication, considering it a “school of immorality for youth.”3 During one investigation into the murder of a child by its mother, a “person in authority” declared to a journalist from Allô Police, “Maybe this woman was encouraged to do what she did by reading the story of the C. woman in your newspaper?”4 But even denunciations from the pulpit did not seem to affect its circulation.5

The abuse and murder of children were subjects too appetizing to escape the attention of Allô Police, especially since trials of this kind always attracted a large crowd. According to experts, this public curiosity could be explained by the fact that parents projected their own “aggressive impulses” on the accused so that they could then criticize and condemn them.6 So Allô Police was responding to a psychological need. Starting with its first year of publication, before turning to cases occurring in Canada, the tabloid devoted a dozen articles to similar instances from France and the United States. The fifty or so Quebec cases are not numerous enough to provide the basis for a refined statistical study. Indeed, the paper’s quest for sensationalism would not allow it.7 On the other hand, an analysis of the reporters’ comments is not without interest. To succeed in moving the public they had to express themselves in easily understandable terms and appeal to their readers’ emotions while respecting the limits of their sensibility to avoid disgusting them. The articles therefore reflected the feelings of the public while at the same time they helped to shape public opinion. The tabloid sometimes reproduced extracts from trials, quoting judgments, statements by witnesses, the accused, and psychiatrists, as well as comments expressed by jurors once the proceedings had ended — all valuable information that reveals the opinions of everyone involved on the subject of violence toward children. Finally, even if the period studied is relatively short, it is possible to trace an evolution in the opinions of the journalists and other individuals involved in the trials.

Between 1953 and 1965, Allô Police described fifty-four cases in Quebec of children beaten or killed by their parents or substitute parents.8 In addition to this basic corpus, an equal number of cases from France and the rest of North America provides a useful comparison.

In these fifty-four Quebec families, forty-six children died (seventeen girls and twenty-nine boys), while twenty-seven survived the abuse inflicted on them (eleven girls and sixteen boys). There were cases of collective ill-treatment or murders in nine families without regard to the sex of the victims. The ages of the beaten children ranged from eighteen months to fifteen years, with only one child being younger than two years. The children who died ranged in age from eight days to ten years. Twenty-one were under two. The most frequent causes of death were asphyxia and head injuries.

These cases took place in thirty-six localities, from Gaspésie to Abitibi, and from the Saint-Henri neighbourhood of Montreal to Westmount. Some of the tragedies were a result of poverty and ignorance, but journalists soon discovered that abuse was not confined to deprived environments. Even “in a cultivated country like France it is stupefying to find torturers of children.”9

The paper did not always indicate the outcome of the trial, making a statistical approach even more questionable. However, subject to some reservations, we can compare the distribution of verdicts according to the sex of the accused. Among the twelve men accused of causing the death of their child, four were declared insane, two were found guilty, and one received a suspended sentence, while in five other cases the verdict is unknown. Among the twenty-four women accused, fourteen were considered insane, two were acquitted for lack of proof, only one was found guilty, and the remaining seven verdicts are unknown. All those who received sentences had pleaded guilty to charges of manslaughter or criminal negligence. So, making due allowances, among the cases publicized in Allô Police a verdict of insanity was reached much more frequently in the case of women than of men.

As for those accused of abusing a child without it resulting in death, four of the ten men accused were found guilty and one was acquitted, while three of the thirteen women were found guilty and two were acquitted.10 The small number of known verdicts (ten out of twenty-three) is not sufficient to allow us to state categorically that the courts were more indulgent toward women than men. The comments of journalists and participants in the trial reveal the opinion of society about these crimes better than these incomplete statistics.

Since in the province of Quebec the name of Aurore Gagnon was synonymous with child abuse, no one will be surprised to find that Allô Police made the comparison in about ten cases. In 1955, relating the story of Pauline D., the headline chosen was “‘Recital’ of Horrors: A New Aurore, Child Martyr.” A month later, the case of Hélène bore the heading “Three Little Martyrs: Aurore, Pauline, and now Hélène.” Then, in the following year, a third case of the same nature bore the headline “Another Child Martyr: After Aurore, after Pauline, now It’s Barbara.” When similar cases took place in other countries the headline would be “An ‘Aurore’ in France” or “An ‘Aurore’ in New York.”11

The stereotype of the wicked stepmother is, we recall, the oldest in the saga of abused children. No doubt this is why the story of Pauline D. received such extensive coverage. Between January and November 1955 Allô Police mentioned it in ten issues, and also reproduced the cross-examinations in their entirety. This was the case of a fourteen-year-old girl who was abused for months by her father and her “wicked stepmother.” Both of them beat her, burned her with cigarette butts, and humiliated her by forcing her to lick the soles of their shoes, drink urine, and eat her own vomit. Like Aurore Gagnon and most of the other abused children, Pauline did not mention this ill-treatment to anyone. It was her older brother who decided to reveal the situation to an aunt, who alerted the police. The trial that followed attracted a considerable audience and ended with “a severe lesson” for the parents in the form of two years’ imprisonment for assault.12

Journalists wrote about the case using a vocabulary that subsequently would recur regularly: “What might we call such behaviour? Sadism? Madness? The attitude of two degenerates? In any case, the treatments that [her parents] inflicted on little Pauline are almost beyond the most perverse, the most Machiavellian of imaginations.” The news that Pauline wanted to become a nurse aroused the sympathy of the public. The paper then created the Pauline D. Fund, which received contributions from different parts of Quebec and beyond. Finally, a former classmate wrote to her, “If your heart is full of pain, always keep a smile and forgive your enemies. Did Our Lord not pardon his executioners?”13 This advice is reminiscent of the ending of the play Aurore l’enfant martyre.

The tabloid took advantage of the opportunity to tell “the true story of the first Aurore the child martyr,” altering the facts to appeal more effectively to the public’s emotions. For instance, the article said that the sixteen-year-old Aurore had been subjected to such torture that she appeared to have the constitution of a ten-year-old. In fact, Aurore Gagnon, born in May 1909, was ten when she died. According to the writer, the “virago” ordered the little girl to drink a cup of bleach, made her walk barefoot through the snow, and “on the coldest winter nights refused to let Aurore into the house, forcing her to take refuge in the barn. And the next morning Aurore had to walk a mile and a half to school without any breakfast.” These abuses appeared nowhere in the transcript of the Gagnon trial. The journalist had invented them or borrowed them from the novels inspired by the case.14 At the same time he remained silent about the father’s brutality, further blackening the portrait of the “wicked stepmother.”

Initially the journalists emphasized this stereotype of feminine violence. For instance, they depicted the story of Barbara S. as the “eternal story of a stepmother jealous of the children from a previous marriage.”15 But they were not alone in doing so. During the Hélène case, a detective recounted the numerous cases of cruelty he had encountered throughout his career, remarking that “most often it was not the real parents that committed such acts, but fathers and mothers by marriage.” Yet stepmothers were only a minority of the abusive parents mentioned in Allô Police — no more than three.16 At the very beginning and up to 1956, journalists reserved the term marâtre for stepmothers and adoptive mothers. Subsequently, realizing that natural mothers were also capable of child abuse, they applied this derogatory term to them as well.

If the stereotype of the wicked stepmother personified the violence of a female parent, its masculine equivalent was the drunken, brutal father. This behaviour, stigmatized by Émile Zola in the nineteenth century, aroused similar indignation in the 1950s and 1960s. Allô Police relates a dozen cases of this kind (five from Quebec, one from Ontario, and six from France), but the comments made by journalists and judges give a better idea of the current opinion than these numbers.

Among all the individuals mentioned in Allô Police for abusing their children without actually killing them, the heaviest sentence was passed on Alphonse L., nicknamed “the torturer of Mackayville.” This “heartless father” admitted having punched, kicked, and beaten his eleven children with a bullwhip made of nine braided strips of leather. In addition, he came close to hanging them by passing a rope with a running knot around their necks, attached in such a way that they had to stand motionless on tiptoe for fear of being strangled. When a detective asked him why he did these things, he answered: “So I wouldn’t have the trouble of beating them. It’s not so tiring that way,”17 though sometimes he would also whip the children when they were in this position and unable to move.

The description of such “barbarous tortures” in Allô Police caused a sensation, and on the day of Alphonse L.’s trial the courtroom was completely full. A previous conviction for a “serious assault” on his fifteen-year-old daughter made his case worse. In addition, he had seldom worked since his marriage, and had always spent his money on drink. The family received assistance from the local social services, but since only the father was entitled to cash the cheque he took advantage of this to squander it on alcohol. If his wife protested, he beat her. During the trial, the judge did not mince words: “You are a re-offender, brutal, lazy, an inveterate alcoholic, a bad husband and an unworthy father. But what weighs heaviest is that you are a torturer of children.” Finding no attenuating circumstances, the judge considered it necessary to protect children abused by “vicious, cruel, and unnatural parents.”18 He therefore condemned the accused to five years’ imprisonment.

A drunken father breaches all the rules of conduct fixed by society. As a bad citizen he fails to feed his family, leaving it to public charity. As a bad husband he beats his wife. As a bad father he sets his children a deplorable example, and beats them for no good reason. The aversion he inspires is so strong that, in the rare cases when a son decided to do away with such a father, society (represented by the journalists and the jurors) did not conceal its approval. Allô Police reported two cases of the kind in Quebec, and a third in France.

Lionel P. suffered from a bad reputation. An unemployed carpenter and notorious alcoholic, he obliged his family to live on welfare. But he would often take the money to go drinking, beating his wife soundly when she protested. One day he even fired eight rifle shots close to her. Between 1932 and 1963 he was sentenced on ten occasions for drunkenness, refusal to provide, and attempted suicide. One day when he was threatening his wife, his seventeen-year-old son took a gun and fired three shots into him. Allô Police reported the case with headlines that made it obvious where its sympathies lay: “The drunken father who was starving his family has paid for his brutality” and, further on: “To protect his mother who was being beaten, he killed this drunken father who was drinking all the money.” The outcome of the case was described as follows: “The jury absolved the adolescent, who killed his drunken, debauched, quarrelsome father to protect his mother who was suffering beatings, cold, and hunger.”19

During the trial, the young man’s lawyer cleverly emphasized the contrast between the father, “a despicable individual, a drinker, debauchee, and sloth of the worst kind,” and the son, “a very good lad, a worker, who neither drinks nor smokes and hands over all his wages to his mother.”20 He easily convinced the jurors that his client had acted in self-defence, and they acquitted the boy after deliberating for only five minutes. Nevertheless, in setting him free, the judge reminded him of his filial duties:

You had to choose between two feelings: for your father and for your mother. Unfortunately, the deplorable misdemeanours of your father destroyed or weakened your feelings for him, while strengthening those for your mother. However, do not forget that this man, despite his many mistakes, will always be your father. In the future, do not try to sully his memory. Remember God’s commandment, “Honour thy father and thy mother, that thy days may be long …21

In this family the father was the true delinquent. In killing him to protect his mother, the son had prevented a greater evil and re-established a degree of family order, hence society’s approval. The judge’s final remarks were a reminder of a rule of conduct to be observed in spite of everything: respect for a father’s memory.

The stereotype of the drunken father was so powerful that it overshadowed other forms of paternal violence, especially in the case of excessively harsh fathers like Télesphore Gagnon. In the article published in 1955 that told the “true history of the original Aurore the child martyr,” the journalist said absolutely nothing about the injuries inflicted by the father, though he did mention that the latter was condemned to life imprisonment. And, in 1961, when Gagnon died, Allô Police insisted on the fact that “Télesphore Gagnon was not a criminal,” having been unaware of his wife’s actions: “If he lacked clear-sightedness, he never nourished any dark designs in his simple, peaceable carpenter’s heart. No, in the eyes of all Télesphore Gagnon was a decent, peaceable man, the victim of his married state.”22 The author of this article had clearly not perused the transcript of the Gagnon trials or the newspapers of the time. Instead, he had based his account on the novels and the play about “Aurore the child martyr,” and, like them, helped his readers to forget that a sober and apparently respectable man was capable of turning severity into cruelty.

The stereotypes of the wicked stepmother and the drunken father helped to maintain the illusion that child abuse occurred only in blended families, or in ones that were disorderly because of the father’s bad behaviour. But sometimes parents who until then had seemed beyond reproach would cause the death of a child. How could such troubling facts be accounted for? The answer was another stereotype, that of mental illness.

In 1860, Ambroise Tardieu commented on the difficulty of accounting for the cruelty of some parents. “I am not surprised that people are inclined to attribute [such acts] to some aberration of affective feelings, to a kind of madness,” he wrote, immediately adding that he had never encountered madness in the thirty-two cases he had analysed. Nowadays specialists admit that mental illness is one cause of abuse, but there is no agreement on the extent of the phenomenon. Some, especially Gelles and Straus, consider that this factor plays a part in 10% of cases at most,23 but that since it is those 10% that make the headlines they help to sustain the myth that the majority of abusive parents are mentally disturbed.24 In fact, Gelles and Straus cite a study by Ruth and Henry Kempe that showed that 10% of abusive parents suffer from a mental illness too serious for treatment to be possible, while the rest are curable.25

When Allô Police reported the story of children killed by their parents, especially if the victim was a baby or in cases of a collective homicide, the journalists’ initial reaction was often to ascribe the deed to mental illness. In presenting the case of Jean N., who had suffocated his three children with plastic bags, they stated: “For a father to end up killing his children, something must have gone wrong in his brain.” Otherwise, how could one explain “that a mother, after loving and cherishing for seven years a being to whom she has given the gift of life, should suddenly deprive this other self of its existence by fracturing its skull with a baseball bat? The very fact of asking the question is instantly repugnant to any human being.”26 The explanation provided by these journalists corresponds exactly to that given by Tardieu.

Lawyers often used insanity as a defence. When a psychiatrist confirmed this mental condition, the accused was found not guilty, or unfit to stand trial, and sent to a psychiatric facility until cured.

Psychiatrists participating in such trials as expert witnesses developed an almost teleological argument, especially when the accused was the child’s mother. They based themselves on the principle that a normal woman feels an instinctive love for her child. The very fact that she killed the child was proof that she was not in her right mind. The existence of mental illness allowed the dogma of maternal love to be reconciled with such a murderous act. Let us follow the reasoning of Dr Lucien Larue, Medical Superintendent at Saint-Michel Archange hospital, a specialist in mental illness, and Professor of Psychiatry at Laval University:

For anyone familiar with maternal love and the devotion of a mother who does not hesitate — and the examples are legion — to rush into a burning house or river water to save her little ones, a mother must have become mentally unbalanced to commit the murder she is presently accused of, and of which she claims to be innocent.27

This mental imbalance, which the psychiatrists of the time usually called “melancholia,” still appears today in lists of mental illnesses.28 Dr Larue has described its symptoms, showing that there is no contradiction with maternal love:

She was suffering from melancholia at the time. Such patients experience feelings of guilt and scruples, they fear damnation, and are profoundly dispirited. They think of killing themselves, and often also of killing those close to them to spare them suffering, as they believe. Their will power is utterly controlled by such ideas, and they are no longer free to choose between good and evil.29

In five trials Dr Larue insisted on the fact that the mothers had killed their children to spare them suffering in this life or in the next.30 They had therefore committed “altruistic” homicides, motivated, paradoxically, by maternal love.

In addition to melancholia, Quebec psychiatrists diagnosed other illnesses capable of driving a person to infanticide. Epilepsy,31 psychosis, early dementia, or nervous depression were all disorders that could drive a mother irresistibly to commit a murder, rendering her incapable of distinguishing good and evil and therefore not responsible for her actions.

Journalists followed closely what psychiatrists said, either because they shared their convictions or because they wanted to provide an explanation that the public wanted to hear. They therefore stressed the fact that five of these mothers loved their children. Réjeanne B., for instance, “adored” her three little girls. But, as she declared to the police, believing that she was enslaved by a shameful vice and fearing that her girls had inherited it, she killed them to spare them eternal damnation. Janine C. also “adored” her children, yet she strangled her five-month-old in a fit of nervous depression.32

The explanation of mental illness was also used in cases of men accused of killing their children, except that psychiatrists abstained from fine-sounding statements about paternal love and did not diagnose melancholia, speaking instead of serious cerebral lesions or some mental illness with no specific name. The journalists did stress that two of these fathers loved their children, but they made the point less forcefully than in cases involving women. For instance, they quoted Raoul D.’s confession to the police after killing his wife and four children: “I feared for the safety and happiness of my family.” They also mentioned that Alain P. loved his two-year-old son, yet he killed him with a hammer. No one in the family contradicted this.33

However, the explanations given for mental illness were not the same for both sexes. Speaking of women, psychiatrists talked about “puerperal psychosis” as a consequence of giving birth or a miscarriage.34 In the case of Ginette C. the journalist explained, “The birth had been difficult: the young woman’s strength had been sapped. She was upset by a trifle. If the child cried, she panicked. Suddenly, a thought came into her sick mind: ‘He must not suffer.’ She adored him. She drowned little Brian so that he would not suffer in this life.” Réjeanne B. had become very “odd” after the “cruel disappointment” of giving birth to a stillborn baby. As for Francine M., “repeated miscarriages had literally exhausted her” physically and morally, and her nerves were affected. This explained why, in a moment of madness, she had murdered her ten-month-old son, even though she adored him.35

In the case of men, work-related fatigue or financial concerns arising from unemployment were cited instead — in other words the same explanation as for men’s nervosity, as we saw in the previous chapter. If Jean N. had killed his three children, it was because of overwork due to the construction of his house: “In his exhaustion he seems to have momentarily lost his mind.” The murderous act committed by Alain P. was attributed to his recent loss of employment, in addition to the occasional cerebral disturbance that periodically affected him. As for Réginald B., who had beaten his little four-year-old daughter to death, the journalists described him from the outset as “a decent man, easily angered but with a good heart, on the verge of a nervous depression.” He and his family lived in extreme poverty. “The poverty that strained his nerves, that exasperated him, got the better of him.”36

The journalists displayed sympathy for all these individuals. They referred to them using expressions such as “this unfortunate father,” “the unhappy mother,” or “a pitiful little mother.” One of them summarized the general impression: “Tragedies caused by insanity occur with alarming frequency in the province, but it seems that not much can be done about it apart from sincerely pitying the mentally ill and wishing for their cure.”37

This sympathy seems to have been shared by the public. When Raoul D. was acquitted on grounds of insanity a long sigh of relief was heard in the courtroom and, following the accused, several women burst into tears. Janine C., who strangled her baby, also enjoyed widespread sympathy, starting with the judge, once Dr Larue had convinced everyone that she had obeyed an irresistible impulse.38

These three stereotypes (the drunken father, the wicked stepmother, and the mentally ill) did indeed partly fit the reality. Recent studies have confirmed that alcohol abuse does in fact increase the risk of family violence,39 that children in blended families are particularly at risk,40 and that some parents who kill their children do suffer from mental illness.41 But such cut-and-dried portraits also helped to maintain the illusion that abusive parents were easy to recognize and categorize, and above all that they had nothing in common with “normal people.”

The man in the street, who was sometimes called for jury duty, was most reluctant to admit that biological parents could kill their children without the excuse of mental illness. By railing against drunken fathers and wicked stepmothers and showing pity for the mentally ill, Allô Police contributed to a Manichaean perception of parental violence that kept it in tune with its popular readership. But after witnessing a number of trials, journalists refined their critical sense and finally discovered, as social workers, probation officers, and popular newspaper columnists had already done, that some kinds of parental violence did not conform to the stereotypes. They noticed that apparently respectable biological parents could kill their children out of anger or hatred, or ill-treat them using the excuse that they were raising them properly. They did express such opinions in their articles, but cautiously, either because they were afraid to question the judgments of the courts or because they did not want to upset their readers by challenging their beliefs.

There is no neat dividing line between nervous depression (as mentioned in the newspapers) and mere nervosity, impatience, or anger. The old Latin saying that “Anger is a short-lived folly” and the popular Quebec expression poigner les nerfs, meaning “to lose patience” or “become angry,” show how imprecise the idea of violence was.

Among the cases of violence reported by Allô Police, fourteen parents (eleven women and three men) were described as edgy or impatient. The continuous crying of a child was a major source of exasperation: the paper reported fourteen cases of infants killed and two cases of children abused by parents (eleven women and five men) for such a reason. Indeed, some of the accused admitted it quite spontaneously: “I lost my temper with the child’s crying,” said Alexander G., who caused the death of a twenty-three-month-old infant by throwing him to the floor; “I lost my temper and killed the little one,”42 confessed Alice J., after battering her baby to death because it was crying.

The journalists reported borderline cases in which it was difficult to be sure whether the death of the child should be blamed on mental illness or on just an angry reaction on the part of its mother. Such was the case of Giselle L. This thirty-year-old woman could not bear hearing her baby cry: it got on her nerves. On two occasions she felt like murdering the child, but did not put it into effect. Instead, she phoned her doctor who gave her a tranquillizer. But one day, when the ten-month-old began to cry, she lost patience and strangled it with a tie. Then she told her husband, “As usual, I lost control. I suffocated the baby.” She was seen by psychiatrists, and eight months later she was brought to trial. Dr Larue explained that she was suffering from depression at the time of the tragedy, and that she was now completely cured. The jury therefore acquitted her after deliberating for only five minutes.43

The case of Noémie L. was even more troubling. When her husband initiated separation proceedings and claimed custody of their only son, she drowned the thirteen-month-old in the bath, damaged her husband’s house and his car in a vain attempt to set fire to it, and then told her parents: “No one will get the child: I’ve killed him.” She later repeated to the police that she had killed her child so that her husband would not have him, and that she had vandalized the house so that he would get nothing. Such a deed corresponds to the “Medea complex,” named after the enchantress in the ancient Greek myth who killed her two sons to avenge herself on the husband who had abandoned her.44 In an initial article the journalist spoke, not unreasonably, of her “destructive rage.” Later, however, he showed more sympathy for the accused: “No doubt this unfortunate mother was acting under the impulse of a terrible nervous depression. Indeed witnesses … declared that shortly before the tragedy occurred she seemed to be in the grip of considerable nervosity.” The journalists therefore predicted that she would be acquitted on account of insanity. Indeed, fifteen months later, Dr Larue told the court that he had discovered in the patient “an epileptic propensity which made her subject to nervous depression,” and that she had killed “to spare her child the unhappiness that she herself was experiencing.” The jury accordingly found her not guilty without even withdrawing to deliberate.45

In these two borderline cases the psychiatrist was instrumental in the acquittal after claiming to have discovered evidence of mental illness. Witnesses who said they had noticed signs of nervosity in the accused helped to confirm his diagnosis, which had the advantage of supporting the idea that a mother in her right mind could not kill her own child.

In other cases the possibility of mental illness was never mentioned, and the jury had to decide if the accused (who pleaded not guilty) had killed his or her child in a moment of impatience. The twelve jurors bore a heavy responsibility because a guilty verdict for a charge of murder meant hanging. If they wanted to spare the accused such a punishment they could bring in a verdict of criminal negligence or manslaughter, which meant only imprisonment.

Louise L., a young mother of five, married to the owner of a large factory, was accused of killing her youngest child, a one-year-old boy. The doctor responsible for the autopsy stated that death had resulted from trauma to the head that could have been caused by falling against a hard object, or by blows delivered by a person. Two former maids testified that this mother would fling the child down on the kitchen counter and strike its head against it while holding it beneath the arms. On another occasion she had hit it on the head, causing it to lose consciousness. To justify herself the mother first mentioned her stay in a sanatorium and her fatigue after giving birth. Then she admitted, “Sometimes I get impatient, but I never threw Yves against the kitchen counter, even if I did sometimes put him down hard.” She explained why he had lost consciousness: “He fainted because he was too naughty.” As for his head injuries, “He had the habit of himself hitting his head against the walls to show his impatience.”46

She was acquitted by the jury. Why? According to the journalist “her repeated bouts of weeping were able to move the members of the jury.” After the trial one of them explained, “The two maids were too young to know anything about child-rearing, and they surely exaggerated when they said Louise L. had flung her child onto the kitchen counter. Perhaps she had set him down a little hard, like she said, but there’s nothing criminal in that.” He and his fellow jury members preferred to believe that the child had developed partial hydrocephalus from an accidental fall on the floor, and that he died from excessive crying, which had been fatal because of his fragile brain. Then came the explanation: “If Mme L. had been a bad mother like they wanted to make out, the neighbours would have noticed. But no neighbour of the L.s’ entered the witness box to say so.”47

This last sentence provides a good demonstration of jurors’ notion of an abusive mother. It was someone like Aurore Gagnon’s stepmother, who cold-bloodedly applied unusual tortures such as a red-hot poker and bread smeared with soap. Louise L. did not correspond to this stereotype of the bad mother. Far from it, indeed, for she was an attractive, elegant woman, the child’s biological mother, and the wife of an important industrialist. In addition, jurors believed it was impossible for a child to be abused without neighbours noticing. The kind of reaction exemplified by these jurors would later be explained by Richard Gelles: when an individual did not fit the stereotype of an abusive parent he or she had a good chance of evading suspicion.48

The reporters for Allô Police let it be known that they were far from satisfied with this verdict: “A jury refused to believe that this mother beat her child to death.” The comments printed in bold to stand out were even more explicit: “The stout miners of … favour the use of severe physical punishment to chastise unruly children. Such at least seems to be the opinion expressed by the twelve jurors of the Assize Court.”49

Louise L.’s acquittal can be partly explained by the fact that the doctor could not be completely sure whether the child’s injuries resulted from a fall or from blows inflicted by the mother. But even when a doctor was categorical on this point jurors were reluctant to admit that a parent could kill his or her own child, as is shown by the following case. In 1959, a man was accused of having killed his five-month-old. The child’s mother recounted how it happened:

Since the beginning of the afternoon he had been drinking white whisky with his father. Early in the evening, the baby cried. My husband went to hit him to make him keep quiet. I tried to stop him. He gave me a clout. He lifted the little one, and then let him drop, taking no care.… A little later he struck the child several times … several times, and with all his strength.50

The father’s version was different: the child’s mother had fallen on the stairs while holding it, which accounted for the traces of impacts on her face and on the child’s body. However, the doctor who had been called in shortly after the events noted the presence of bruises on the child’s head and over its entire body and was sure that if there had been a fall “the child would not have broken its neck but its nose.” In spite of this the jury allowed the accused the benefit of the doubt and found him not guilty. The reporter noted the surprise of the judge who was “obliged to accept [the verdict],” but told the accused, “You can count yourself lucky.”51

In two similar cases the accused pleaded guilty to manslaughter and, without using mental illness as an excuse, admitted they had acted out of nervosity and impatience. The reactions expressed by the journalists and the sentences imposed by the judge were greatly influenced at the time by the degree to which the profile of the accused did or did not correspond to the stereotypes described above.

Arthur R., aged twenty, exasperated by the crying of his little three-month-old girl, smothered her while trying to quiet her. He admitted this at the trial: “I was upset, tired, and at breaking point because the little one never stopped crying. I closed her mouth to stop her bawling.… I don’t know what I did.… It was my nerves got me.”52 Even if what he did differed little from the action of Giselle L., who also admitted losing her self-control, this man was far from earning similar sympathy from the journalist. From the start of the case the paper depicted him as a “tough” who preferred riding his motorbike to family life and cared little for his responsibilities as a husband and father. A former boxer, he had often beaten his wife and had already been found guilty of injuring a child, but incredibly a judge had merely sentenced him to time served. “That’s what happens when you allow yourself to be touched,”53 said the second judge as he sentenced the re-offender to fourteen years.

Oswald W. caused the death of his four-month-old in very similar circumstances. Driven to distraction by the child crying during the night, he struck it with its bottle, likely a glass one. But when he gave in to impatience this twenty-five-year-old student, unlike Arthur R., did not have a “stiff back from excessively long outings on his motorbike.” He was tense and tired because he was writing a doctoral thesis. He wept in the presence of the police, saying, “I’ve lost everything. I’ve worked for nothing all these years.”54 The prospect of his career being ruined clearly affected him more than the death of his child. Yet he had the profile of a good citizen and benefited from the support of several individuals from university and scientific circles. His lawyer defended him eloquently: “He lost control of himself for five seconds. That does not make him a criminal in the meaning of the law.”55 He therefore got off with a suspended sentence. However, the prosecuting counsel and the judge ordered that he continue to be regularly followed by a psychiatrist, particularly since his wife had given birth to another child since the tragedy. This decision, which took the accused’s past life into account, also treated him as a mental patient deserving of sympathy.

Juries found it difficult to admit that without the excuse of a clearly identified mental illness a mother could kill her child out of mere impatience. The notion that she could act out of hatred seemed even more inconceivable. Yet such an intention was expressed in the advice columns, and admitted to psychiatrists and social workers. When the columnist Colette received a confession of that nature she viewed it as a pathological case, or as evidence of psychosis. Janette Bertrand also responded to a mother who wrote that she hated her child saying that she needed to obtain treatment as soon as possible.56

Allô Police reported a few cases of this kind. The hatred could arise from the child’s sex, as with Élise G., disappointed to have had a boy instead of a girl. Writing about an Isle-Maligne woman, the journalists spoke about a hereditary insanity that apparently took the form of hatred of the female sex: this mother apparently detested all women, even her own daughter. Valérie N.’s behaviour was just as peculiar: she felt a kind of hatred for her little daughter who had had a blood transfusion, saying that she was not hers any more because she no longer had her blood. Such an aversion could go as far as desiring a child’s death. One witness stated he had heard a woman say, as her son was being taken to hospital, “I hope they finish him off this time.”57

It was in Judith M. that the hatred and desire for death was most flagrant. She was accused of murder after the death of her four-year-old son. The lawyer for the Crown set out to prove that she hated her child and inflicted punishments on him that were out of all proportion to his age and his offence — in other words punishments that went beyond what was allowed by Article 43 of the Criminal Code. The doctors declared that the child had died from trauma to the head and were unanimous in saying that this was certainly caused by blows rather than by a fall on the stairs, as the mother claimed. Two neighbours gave evidence that they had seen her slapping her son, banging his head against the wall, and even breaking a broom handle over his head. A policeman reported the child’s words: “Mummy always hits me on the head.” The witnesses also said that the mother constantly repeated that “it would be good riddance if Kenneth died.” To a female warder who asked why she mistreated her child in that way she was said to have answered, “Because I don’t love him.”58

Such testimonies were very reminiscent of those heard during the trial of Marie-Anne Houde-Gagnon. Yet the defence lawyer was able to get one doctor to say that the scrapes on the victim’s back were “possibly” the result of a fall on the stairs. This sowed some doubt in the jurors’ minds. Furthermore, the young woman’s pregnancy made a favourable impression on the jury. When the words “Not guilty” were pronounced, the journalist heard a murmur difficult to define run through the courtroom: “Was it relief … or consternation?”59 The reporter’s own opinion was evident from his choice of the words “cruel mother,” and “punch bag,” to describe the mother and child. All these verdicts show how difficult it was at this time to prove the criminal responsibility of a parent for the death of a child.

In the United States the same difficulty prevailed until a team of doctors headed by Dr Henry Kempe undertook a nationwide research project in hospitals and district attorneys’ offices. The results were published in 1962 in an article entitled “The Battered Child Syndrome.” After pointing out the reluctance of doctors to believe that parents could ill-treat their children and that parents who did were not all mentally ill, they put forward a method based on the use of X-rays to recognize certain types of injuries that could not have resulted from a fall and must have been caused by an adult’s violence.60 This study provided doctors with a reliable way to identify battered children. Subsequently, as in the United States, laws and regulations were enacted in Canada requiring doctors to report cases of abuse to the police. Measures were also taken to facilitate collaboration between hospitals and social services in order to protect children more effectively.61

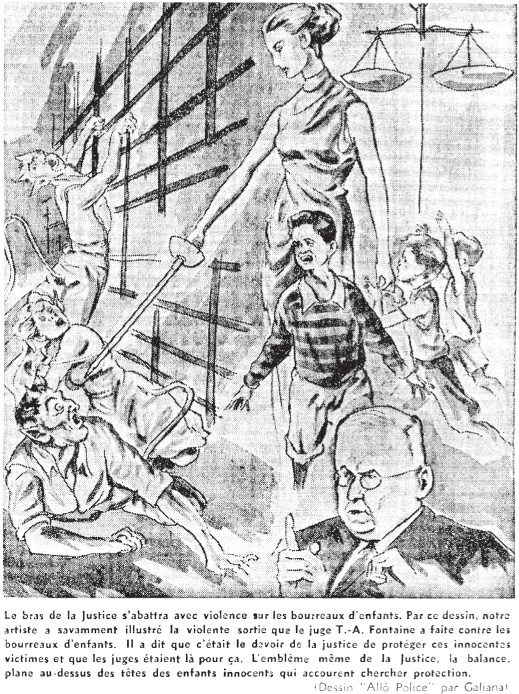

“Someone is needed to protect children against unnatural fathers, and that someone is the judiciary.” This declaration by the Judge T.-A. Fontaine which was reported in Allô Police in 1957, was accompanied by a drawing showing that “the strong arm of Justice will fall with violence on the torturers of children” (see Illustration 16).62

Despite the grandiloquent tenor of the words and drawing, we know that it was not easy to have the court recognize parents’ guilt, especially since Article 43 of the Criminal Code granted them the right to inflict “reasonable punishment.” Lawyers and judges were therefore torn between the desire to protect children and the obligation to respect this parental right. An argument on this subject between a prosecutor and a judge took place in 1956. The former wanted to bring a charge of “wounding with intention to mutilate,” while the latter considered that a charge of bodily harm was sufficient. The prosecutor was insistent: “We have to make an example; the public should be kept in a constant state of alert so that it can report other similar cases to the police.” The judge retorted, “I am not here to conform to trends in popular sentiment,” adding that even if he did not approve of corporal punishment it had to be recognized that “parents have the right to punish their children in the same way as certain educators in certain teaching establishments.”63

A judge therefore had to differentiate between a severe parent and a sadistic despot, which was not easy, because both sheltered behind the right to punish children.

Illustration 16 “The Long Arm of the Law”

The long arm of the law will fall with violence on the torturers of children. In this drawing our artist provides an eloquent illustration of Judge T.-A. Fontaine’s fierce outburst against the torturers of children. He declared it was the duty of the justice system to protect these innocent victims, and that is what judges are for. The very emblem of Justice, the scales, hovers above the heads of the innocent children, who are flocking in, seeking protection.

(Drawing by Galiana for Allô Police)

In an inflated style the journalist and the artist for Allô Police confronted the “torturers of children” and their “innocent victims.”

Source: Allô Police (1 Dec. 1957), 13.

Accused of having beaten his daughter with a chain, Alphonse L., the “torturer of Mackayville,” justified himself by saying that he wanted to know the source of the money that she brought back from school. “I just acted like a good father should,” he said. As for the other children that he beat after tying them up with a slip knot, “It was to make them do what they’re told. You know, children don’t always listen to what you tell them.”64

Allô Police listed a series of children’s faults that parents had punished with a beating. Monique B., aged five, committed the mortal sin of writing left-handed. Her father showered so many kicks and punches on her that the walls were spattered. A little boy of two and a half in Gaspésie refused to “pee on the potty.” His mother’s punishment left him with bruises all over his body, a split lip, a black eye, and a cut on his forehead. Toilet training caused some parents to resort to unusual punishments. Little Serge L. was still not trained at the age of four: his mother tried to tie off his penis to prevent him from urinating. Maryse C.’s little two-year-old girl was not trained either. Her mother therefore decided to make her eat whatever she left in her diaper with a spoon. When the child balked, her mother banged her head against a wall. Noël-Jean, aged six, still wet his bed. His parents kept him shut in the cellar for months. If he complained, a bucket of water was thrown over him. The police, alerted by his older brothers, refused to believe in such abuse until they discovered the child in a state of indescribable filth.65

Parents who ill-treated their children incurred the disapproval of their neighbours, yet a number of well-intentioned people recommended slapping as a way to discipline difficult children. A neighbour gave such advice to Hortense G.: “I found that little Liette was very nervous and spoiled, and got on her mother’s nerves. I even encouraged her to give a few little slaps to mould her character.” To this suggestion, the mother had replied, “I daren’t lay a hand on her, or I’d kill her.” And indeed she did end by drowning her in the bath. The doctor who looked after little David W. did not go so far as to advise his parents to strike the four-month-old, but it seems he did explain to them that “the child was bad-natured, which was why he woke up constantly and refused his feed.66 If he actually said such a thing, as the father asserted, how can we be surprised that the parents reacted with violence to the child’s tears instead of trying to discover their cause?

Corporal punishment was even used with children described as mentally slow. Barbara S., aged ten, was found to have numerous traces of blows after her teacher alerted the authorities. Her paternal grandmother found the suspicion of ill-treatment exaggerated: “Barbara is a difficult child. She is stubborn and backward,”67 suggesting that the punishment was justified. Some foster parents and even a judge shared this point of view, as can be seen from the following case.

Prosecutors and coroners invited neighbours to keep their eyes open and report cases of child abuse,68 but such initiatives did not always meet with success, as two students discovered in 1962.

Pierre X. was described as a difficult child of below average intelligence who was bullied at home and at school. The social services therefore put him in a foster home. Two students who boarded in the same house saw the child being struck with a ruler whenever he made mistakes in his homework. Then the foster parents decided to cure him of his habit of playing with matches. The daughter of the house, aged sixteen, informed the young men that she was going to prepare a cold bath for Pierre; then she asked them for matches. Shortly after, hearing the child’s cries, the two students recorded them on tape to preserve some proof. They then alerted the social services, who withdrew the child from the home. The doctor found bruises on his arms and hands, and ulcerations on his buttocks of a type encountered in burning cases.

A trial ensued. The child stated that his foster parents had plunged him into a bath of icy water and burned his buttocks with matches. The lawyer for the defence suggested that the child played with fire so often that he could well have burned himself. Furthermore, the judge rejected the testimony of the child because it was not corroborated by any eyewitness. A teacher informed the court that Pierre X., who was disobedient and untruthful when he first came to school, had subsequently improved. The judge drew the conclusion that “it can reasonably be presumed that his stay with the accused has something to do with this improvement.69 In his judgment he placed no blame on the foster mother for striking a child to punish him for his learning mistakes.

His final conclusion was that the only proven punishments were a cold bath and deprivation of the boy’s evening meal, which were inflicted in order to cure the boy’s arsonist proclivity. Since the law authorized corporal punishment and recognized its traditional effectiveness, and that a punishment could not be called unreasonable if it resulted only in minor injury, the accused was acquitted. “What was considered torture was merely discipline,” read the headline in Allô Police.70 This acquittal can be explained by the fact that in a criminal trial the accused must always be given the benefit of the doubt. But the judgment once again shows the blurred line between reasonable punishment and ill-treatment.

___________

In spite of its sensationalism and the excesses in its language and illustrations, Allô Police helped to inform the public of the existence of abused children. By virtue of that fact the tabloid was a useful counterweight to an overoptimistic declaration made by the journalist Odette Oligny in 1955: “We are living, thank God, in a country where corporal punishment is not in favour. In Canada you won’t find any ‘child martyrs,’ and people remember the indignation that the Gagnon case provoked in its day.”71

During the 1950s and 1960s the readers of popular tabloids could find in Allô Police all the causes for violence that appeared in the advice columns during the same period: alcohol, nervosity, and the brutality or animosity of biological parents and step-parents. In its pages social workers could observe cases similar to those they dealt with every day. An attentive reader could find confirmation of the confidences made to the advice columnists: some parents took their severity to the point of cruelty, others hated a child enough to beat it mercilessly, while several justified their actions by claiming that a child was ill-natured and deliberately provoked its parents’ anger. During the 1960s, experts would note the same phenomena in the United States72 and in English Canada.

The analysis of the cases reported in Allô Police leads to a conclusion that would be confirmed by psychologists: that all parents experience violent impulses.73 Indeed, Dr Spock said that anger was natural.74 But truly adult individuals are able to control their violence. Others give it free rein: “These are in general immature, impulsive individuals, who were themselves ill-treated by their parents in childhood”75 and who display a “repetition compulsion that drives them to reproduce with the child what they themselves have experienced.”76 The death of children as a result of brutal treatment did not occur solely in less privileged environments or ones prone to alcoholism. Violent parents were found in all social classes, and could be very well educated and highly esteemed by those around them, with no previous mental problems.77 The case of Oswald W., described above, is a particularly good instance of this. Claire Martin’s father was another good example.

But it was very disturbing to think that aggressive tendencies, and even the urge to kill, could exist in parents, especially in mothers. Certain psychiatrists seem to have felt a need to be reassured about the solidity of the maternal instinct. This explains why they insisted for so long on the altruistic homicide of sufferers from depression, a form of mental illness that “makes one believe in a distortion of the maternal instinct rather than its unacceptable absence.”78

In perpetuating the stereotypes of the wicked stepmother, the drunken father, and the mentally ill parent, Allô Police helped to reassure its readers. Parents who did not identify with any of these three categories could conclude that they were entitled to continue administering corporal punishment “for the good of their children.”79 This was not without risk, for we know today that typical cases of abuse are usually linked to such punishment.80

Comments made by judges, journalists, and witnesses during criminal trials reveal the extent of the courts’ tolerance on the eve of the Quiet Revolution. They tolerated slapping, beating with a ruler for mistakes in schoolwork (even in the case of “slow” or “backward” children), icy cold baths, and, in general, any kind of beating as long as the resulting injuries were minor. As for psychological repercussions, they were never taken into consideration. The more sensitive individuals who denounced such treatment encountered a legal obstacle in the form of Article 43 of the Criminal Code and its possibly liberal interpretation by a judge.

The ultimate consequence of this legal tolerance of corporal punishment was the “martyrdom” and occasionally death of children who had been punished too harshly. But as we have seen juries often refused to believe that a biological parent could kill a child out of impatience or hatred. Only the publication in 1962 of the research by the American pediatricians would allow the magnitude of the phenomenon of child abuse, of which Allô Police provided only a glimpse, to be recognized. Shortly afterwards psychiatrists overcame their horror at the conduct of abusive parents and undertook their treatment with the respect due to any human being, helping them to resolve the unconscious problems that had prevented them from loving their children, and treating them with the same kind of respect.81