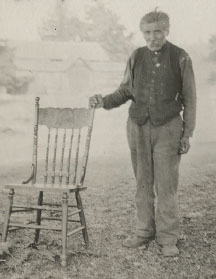

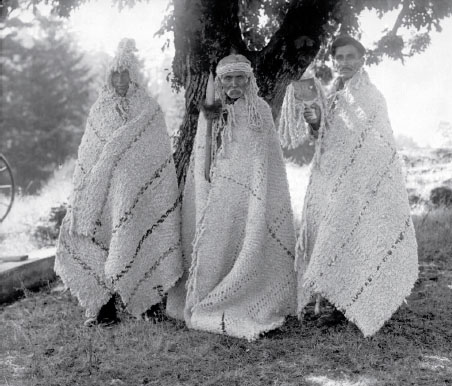

Leaders of the Tsartlip and Tseycum First Nations. See here.

Leaders of the Tsartlip and Tseycum First Nations. See here.

For hundreds and thousands of years, the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) people have lived in the area surrounding Tod Inlet. Once referred to as the “Saanich tribe,” the W̱SÁNEĆ First Nations—Tsartlip, Tsawout (East Saanich), Pauquachin, Tseycum and Malahat—are Straits Salish peoples. Since time immemorial they have occupied an area that extends from Saanich Arm in the west to the San Juan Islands in the east and from Mount Douglas north to Satellite Channel, as well as lands in the neighbouring Gulf Islands. A part of the larger group of Coast Salish peoples, they have lent their name to three of Greater Victoria’s municipalities and to the Saanich Peninsula itself.

ȽÁU,WELṈEW̱, renamed Mount Newton by settlers, means “place of refuge” in SENĆOŦEN.

The following version of the W̱SÁNEĆ creation story was written by Philip Kevin Paul of the Tsartlip First Nation in a paper for the Institute of Ocean Sciences in Sidney, BC:

Long before the first white man arrived on the shores of Vancouver Island, in a time when my people shared the Earth with all that is living, the people who lived here were given a name. This is the story of the Saanich People:

Once, long ago, the ocean’s power was shown to an unsuspecting people. The tides began rising higher than even the oldest people could remember. It became clear to these people that there was something very different and very dangerous about this tide.

An elder amongst the people brought everyone together and told them they would no longer be safe in their homeland, that they would have to move up into the mountains where they would be safe. He told them that they would have to gather together their canoes and all the rope that they could carry. He told his people that he did not know how long the tide would continue to rise, and that for this reason they would have to leave. So the people of this small village took some food, their canoes and all the rope they could carry and moved to the nearest mountain.

The sea waters continued to rise for several days. Eventually the people needed their canoes. They tied all of their rope together and then to themselves. One end of the rope was tied to an arbutus tree at the top of the mountain and when the water stopped rising, the people were left floating in their canoes above the mountain.

It was the raven who appeared to tell them that the flood would soon be over. When the flood waters were going down, a small child noticed the raven circling in the distance. The child began to jump around and cry out in excitement, “NI QENNET TŦE”—“Look what is emerging!” Below where the raven had been circling, a piece of land had begun to emerge. The old man pointed down to that place and said, “That is our new home, W̱SÁNEĆ, and from now on we will be known as the W̱SÁNEĆ people.” The old man also declared, on that day, that the mountain which had offered them protection would be treated with great care and respect, the same respect given to their greatest elders and it was to be known as ȽÁU,WEL,ṈEW̱—“The place of refuge.” Also, arbutus trees would no longer be used for firewood.

Paul comments on the important symbols within the W̱SÁNEĆ story of the flood: the arbutus tree, the raven, the mountain and the emergence of the W̱SÁNEĆ people. He emphasizes the importance of each symbol to his people and how the story is “a reminder of our relation to the animals, represented by the raven; to the plants, represented by the arbutus tree; to the Earth, symbolized by the mountain; and to the Creator (or God), shown by the emergence of W̱SÁNEĆ Saanich and by the rising flood waters.”1

First Nations people bake clams at Cordova Bay, north of Victoria, about 1900. Henry Muskett photograph. RBCM G-04231.

Tod Inlet is a significant part of the Tsartlip First Nation’s traditional territory. The Tsartlip people have not lived on the inlet itself for about 200 years, though traditional use of the area as a harvest camping site and for spiritual purposes has been virtually continuous.

To better understand the people who the legends and oral histories introduce, it is helpful to visit, investigate and explore the places where they lived over the past millennia. Tod Inlet itself gives us clues to their lives. Walking the inlet’s shoreline, across the water from where hikers walk today, takes us back to a time when people lived in and depended on the natural environment in a direct, personal and daily way.

In 1998, I walked and scrambled around the shoreline of Tod Inlet to see for myself the places where archaeologists had found evidence of people living long before the first contact with European explorers and settlers.

The eroding shell midden near the water’s edge on the north bank of Tod Creek. David R. Gray photographs.

The present-day signs of those long-ago people are not obvious or dramatic. There are only half a dozen places along the shore where we can see certain evidence of their story. Clamshells—thousands of clamshells, in places forming a thick layer in the exposed banks at the high water level of the shore, and still slowly eroding out onto the lower beach—echo the story. These ancient banks of shells are known as middens, and they are prehistoric refuse piles, marking the places where people lived.

It is not difficult to imagine the people waiting for the low tides, carrying their handwoven cedar baskets down to dig for clams, their feet sinking into the soft, cool mud—and then gathering together as families, as a community, to bake the clams, preserve them and feast on them, casting aside the shells, an unthought gift to a future understanding.

The largest archaeological site in Tod Inlet is a shell midden some 180 metres long and 20 metres wide, on the north side of Tod Creek, extending from the creek mouth along the terraced shore of the inlet. Part of the site is covered by the cement foundation of a much more recent house. The midden is easily noticed from the water at low tide, though, as the shells are eroding out of the bank and are spread over the near shore. Among the shells found here are littleneck clam, butter clam, mussel and native (or Olympia) oyster. Based on the large area of the site, the massive accumulation of shells and fire-broken rock, and the variety of shellfish and other animal remains eroding from the site, archaeologist Grant Keddie suggested that the site might have once supported a permanent village.2 The only artifact found here during the archaeological studies in 1975 was a hand maul, a type of striking tool that functions as a hammer. This hand maul is of the nipple-topped type, a tool typical of the culture known to archaeologists as the Marpole Culture, named for the location of an important archaeological site in Vancouver. Based on the hand maul and in the absence of other artifacts, archaeologists suggest that people lived at this site at least 2,500 years ago.

I visited another site on the south bank of the mouth of Tod Creek that is also marked by shells visible on the surface and eroding from the banks of the creek. At most of the site, the shells are intact, and they include butter clamshells, littleneck clamshells and cockle shells. On the beach the shells are broken, probably due to recent traffic related to the nearby log dump from the 1950s. Just north of this site, in 1996, a team of archaeologists led by Duncan McLaren found a flat-top hand maul in the stream’s sandy-mud deposits. Flat-top mauls are associated with the Gulf of Georgia Culture, the culture that followed the Marpole Culture. This suggests that people continued to live at this site in the period from 1,200 to about 200 years ago.

Sketch of a flat-top hand maul found at Tod Creek. Watercolour by David R. Gray.

Hand mauls are a type of stone hammer used in cutting down trees, splitting planks from cedar logs with wedges, driving pegs and even caulking cracks in hulls of canoes. Finding two mauls in this small area suggests that it may have been a place important for felling trees in order to build houses or canoes.

My own archaeological excursions never brought me to a third important site, located in a bay on the northwest side of Tod Inlet, opposite Butchart Cove. This large site shows evidence of canoe runs, areas where large rocks were cleared away so that canoes could be hauled up onto the shore. Logging operations in the 1950s caused extensive damage here, but there are small, intact areas at both the south and the north ends of the site where parts of a larger midden remain, between half and three-quarters of a metre deep. The original midden extended about 110 metres along the shore and 12 metres inland. Archaeologists speculated that it may be the remnant of another village fortified against raiders from the north.

The number of people living at the Tod Inlet sites at any given time is difficult to assess. It seems likely that there would have been several extended families, probably living in a few large houses made of cedar logs and planks.

After visiting these sites, the obvious questions are when and why did people abandon them? Local biologist, fishing guide, teacher and amateur archaeologist Jim Gilbert, who had visited some of these sites in the 1970s, suggested two potential reasons for abandonment: changes in the environment and warfare. Gilbert thought the abandonment could be related to variability in climate, such as cumulative El Niño effects. He pondered the clues offered by archaeology and history that pointed to the possibility of warm water coming north, leading to a collapse in the dynamics of the marine life within Tod Inlet and Saanich Inlet. Perhaps there was no herring run in some years, no salmon or no lingcod. Could ecological change have prompted the move? Based on talking with Tsartlip Elders and his knowledge of the local oral history, Gilbert also pondered another explanation: raids by northern peoples.3

Dave Elliott Sr., Tsartlip Elder and author, described this warfare in his book Saltwater People (1983, revised in 1990): “We used to fight with the northerners. They used to come down and attack our homes, our villages. Many serious wars were fought with the Haidas and the Kwagulths [Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw]. They used to take slaves when they would raid our villages. We also took slaves, if we took prisoners. This is the way it was before.”

Tsartlip Elder Tom Sampson also recalled for me, from oral traditions that had been passed on to him, how in the early times, hundreds of years ago, when the Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw and Haida came, the men would send their families way up into the hills for safety.4

The house belonging to Tsartlip chief David Latasse, left on the waterfront, on the Tsartlip Reserve in 1922. RBCM PN11740.

Tsartlip chief David Latasse on the Tsartlip Reserve in 1922. RBCM PN6165.

Anthropologist Diamond Jenness recorded in 1935 that Tsartlip Elders David Latasse and his wife—Jenness never refers to David Latasse’s wife by name, but the 1911 census lists her as Genevieve—attributed the destruction of their old village at the mouth of Tod Inlet (he called it Brentwood Bay) in about 1850 to either K’ómoks or Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw raiders, who attacked the settlement and burned its three long, shed-roofed houses along with several smaller ones.

In Saltwater People, Dave Elliott Sr. described his family’s connection to early Tsartlip history. His great-great-great-grandmother SEX̱SOX̱ELWET lost her husband and brother to northern raiders while she hid in the woods. They lived in a place now called Tsawout, on the east side of the Saanich Peninsula. In her shock and grief she wandered for many hours and came upon a beautiful meadow divided by four streams. Each stream had a name in her language. “This is where I will raise my son to be a man,” she thought, and later persuaded some of her people to move away from the place of grief to a place of hope. They established a village there called W̱JOȽEȽP, now called Tsartlip. Her son, ȻELOW̱ENŦET, became a strong and tough leader in his tribe, but he too, in old age, was killed by northern raiders. He left many sons, among them the ancestors of Dave Elliott Sr. The original name of the Tsartlip people is JESESIṈSET, meaning “the people that are growing themselves up.”

Dave Elliott Sr. lived with a sadness that the “beautiful way of life” had become only a story in history. Born in 1910 on the Tsartlip Reserve in Saanich, he grew up in two worlds, watching his old world of the canoe gradually transform into the wider world of international travel and space-age technology. He remembered the reef-net fishing from cedar canoes and the smell of woodsmoke from cooking fires of his childhood, and the traditional names for the geographical features of Saanich. He devoted his later years to teaching young people of his nation their own story.5

Most of the following information about the significance of Tod Inlet to the Tsartlip people over the last 100 years or so was shared with me in interviews with Elders of the Tsartlip in September and October 2001.

Tsawout Elder Earl Claxton Sr. remembered his uncles Dave Elliott Sr. and Tsartlip Elder Philip Paul, talking about Tod Inlet as an ideal place for fishing—in particular for spring salmon, because of the shallow sand bottom. In the evening they could always catch springs on the sandbar.

Philip Paul himself said to ethnobotanists Nancy Turner and Richard Hebda that his grandfather Thomas Paul (1864–1950) took the family to Tod Inlet for clams and seabirds. When hunting birds, one canoe would go into the inlet and scare the birds, which would then fly out low over the water up the narrows where the hunters would be waiting in their canoes.6

Tommy Paul (left) and Chief David Latasse of the Tsartlip First Nation and Chief Edward Jim of the Tseycum First Nation (right) in 1922. RBCM PN11743.

In an interview in 2002, Stella Wright from Tsartlip remembered the importance of fishing at Tod Inlet to her people in the days before the cement plant came: “In the spring when the herring spawned, the Tsartlip people used to go up to Tod Inlet. They would take a big cedar branch down to the beach and tow it behind a canoe to Tod Inlet. They would anchor it there, and when the herring spawned, the eggs [roe] would cling to the branches. They would later take it home and clean the roe off the branches. That seasonal delicacy was something the people used to talk about; getting ready for the herring, towing and anchoring the big branches. Different families would do it. They would row back and forth to keep an eye on the branches. As the boats started coming in and there was more traffic, the herring stopped coming in. For fishing, every young man owned a dugout canoe—no one owned a launch in those days. In early spring when the grilse [one-year-old salmon] came in, everybody went out fishing by canoe. Eventually gas boats took over. They did fish in Tod Inlet. Tod Inlet has always been a nice little place for fishing with a canoe.”

A First Nations canoe, adapted for rowing, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, about 1910. Bonnycastle Dale photograph. Courtesy of Kim Walker.

As a young boy, Ivan Morris of the Tsartlip Reserve watched the men and women in canoes, rowing, as they came home from Tod Inlet with their catch: “Our people went out there fishing for fish that they needed to survive.” At times, he recalled, they caught enough fish that they could sell some to get money to buy sugar.

The Tsartlip people used Tod Inlet for many practical purposes, but it also had a profound significance as a spiritual place. It was a place where spirit dancers went to complete their initiations and where young men and young women went to spend time alone, bathing in the cold waters and seeking spiritual insight and support.

As Dave Elliott Sr. put it, “We knew there was an intelligence, a strength, a power, far beyond ourselves. We knew that everything here didn’t just happen by accident. We believed there was a reason for it being here. There was a force, a strength, a power somewhere that was responsible for it…. Our people lived on whales, seals, porpoises, and all the different kinds of fish, clams, oysters, crab. This was all the food of our people. This is how much we had. We were well nourished from that great food supply that was put here by the Creator, the Great Spirit.”7

Tod Inlet was still an important spiritual place for Tsartlip Elder Tom Sampson and his family in the 20th century. “It was sort of forbidden because it was where a lot of spiritual people went.” Tom’s great-grandmother Lucy Sampson told him that Tod Inlet was “a good place, but not until you were ready…. People went up into the hills to prepare for spiritual quests and stayed for days. They would take food: clams and fish and deer. That is why there are some middens at the top of the mountains.”8

Ivan Morris remembered Elder Louis Charlie telling of people going to Tod Inlet for new dances—longhouse dances. “I heard a lot about our people going over to Tod Inlet and living there for the winter, eating fish and clams.” In the spring, Elders always told them, they came back from Tod Inlet, walking home to the Tsartlip Reserve.

The stories told by the artifacts and structures found at the archaeological sites around Tod Inlet, when put together with the knowledge and memories related and recorded by Tsartlip Elders such as David Latasse and Dave Elliott Sr., offer at least a glimpse into the lives of the people who lived at Tod Inlet for countless generations before colonization changed things.

The following yearly round of activities of the Saanich people is based on information from Saltwater People (1990 edition), The Saanich Year by Earl Claxton and John Elliott (1993) and Diamond Jenness’s 1935 notes based on interviews with Tsartlip Elders David and Genevieve Latasse, and Tommy Paul, as published in the 2016 book The W̱SÁNEĆ and Their Neighbours: Diamond Jenness on the Coast Salish of Vancouver Island, 1935, edited by Barnett Richling. The information comes from both West Saanich (Tsartlip) and East Saanich (Tsawout) people.

We don’t know just how closely this rendering of a year’s possible activities represents the lives of the people who lived at Tod Inlet a thousand years ago or more, but the environment and the plants and animals of a century ago, which some of these memories reflect, would have been similar. Rather than starting the year in mid-winter, with the European tradition, I start this account in the spring, with the spawning run of the herring, an important event in the lives of the Tsartlip and in the natural cycle of life in Tod Inlet. The names of the months or seasons used by Elliott (1990 edition), Claxton and Elliott (1993) and Latasse in 1935 (as recorded by Jenness) are not identical, so I have included the variations.

New Zealand–born and Oxford-educated anthropologist Diamond Jenness (1886–1969) became the foremost of Canadian anthropologists. His first visit to Victoria was in 1913, when he joined the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913–1918 as it was launched from the city. During his three years with the expedition, he studied the Copper Inuit, little known to anthropologists, of the Coronation Gulf region of the Arctic. From August 1914 Jenness spent two years visiting, trading, travelling and living with the Copper Inuit. His experiences and the knowledge he gained were documented not only in five volumes of expedition reports, but also in two still-popular books for general readers (The People of the Twilight and Dawn in Arctic Alaska). Jenness collected a huge variety of ethnological materials: from clothing and hunting tools to stories, games and sound recordings of dance songs. On his return from the expedition, Jenness enlisted in the Canadian Army and served overseas for two years as a gun spotter. In 1935 Jenness spent several months interviewing Elders of the W̱SÁNEĆ (Saanich) people and recording their way of life, stories and legends.9 During World War II he was Deputy-Director of Intelligence in Ottawa. His experiences with Canada’s Indigenous peoples from coast to coast while working for the National Museum of Canada resulted in a major work, The Indians of Canada, published in 1932.

The spring run of herring, which spawn in this month, was an important component of this season of fishing. At sea the men also caught cod, grilse, spring salmon and halibut. They hunted deer and elk on land.

Hunting seals and ducks, and fishing for spring salmon, cod and grilse occupied the men in May, while the women began the annual harvest of blue camas bulbs, spring gold (or wild carrots) and rushes for making mats.

During the three-week camas season, W̱SÁNEĆ people left their villages and camped on San Juan Island near their camas harvesting grounds. They also fished for halibut in the deep waters of the Gulf Islands. This was also a time for visiting neighbouring villages and occasionally holding potlatches.

The people of the Tsartlip village left for Point Roberts on the mainland to begin two months of fishing, first for sockeye and then for humpback (or pink) salmon. The women gathered berries and dried the seeds of the consumption plant (wild celery) for flavouring fish and meat.

In this month the men took on the additional activities of building and repairing canoes, and sometimes a trip to the coastal mountains of the mainland to hunt mountain goats. These were added to the regular fishing, hunting and gathering of berries.

The Tsartlip people returned to their village early in the month and prepared their houses, graveyards and wood supplies for the coming winter. Some men went hunting for seals, sea lions and sea otters by canoe, out among the islands. Late in September they would begin harvesting chum salmon as they approached the Goldstream River spawning grounds.

The months of September and October saw more travel between villages, as this was an important time for potlatches. During the month of the “shaker of the leaves” or “winds and falling leaves” (WESELÁṈEW̱), it was a good time to hunt deer and elk, and to catch ducks using aerial nets suspended between trees over a bay or inlet. Other nets were floated on top of the water to catch diving ducks as they came up to the surface.

The people moved back to their home villages on the Saanich Peninsula from their summer and fall travels to the Gulf Islands. The newly caught food would be safely stored for winter.

As the people settled down for winter, travel by the men was limited to hunting and fishing close to home, and by women only to gather fern roots and clams.

Salmon spawning grounds of Goldstream River, October 2018. David R. Gray photograph.

Tod Inlet in winter. David R. Gray photograph.

The month of ŚJELȻÁSEṈ was a time of winter storms and sometimes snow, a time to be at home in warm and comfortable houses. This was the time for winter dances, visiting and storytelling. It was also a time for important work: For the women, a time to make baskets, mats and blankets. For the men, a time for making tools and utensils, carving, finishing lumber for houses and working on canoes.

The long winter moon is called SISET, meaning “old one,” and was a time of continuing storytelling, winter dances, visiting and feasting—a time of legends and family histories.

From December to February people generally remained in the village. When the weather was good, the men fished offshore for cod or grilse, or hunted ducks. The women gathered clams and seaweed, but it was the dried fish and berries, and other plants gathered during the summer, that formed their main winter diet.

ṈIṈENE is the month of “offspring” or “young ones.” During the last moon of winter, the people continued with the regular annual indoor work of carving and making baskets and other necessities of life. It could also be a time for the first duck hunting, but only close to the village. As the tides changed, the people knew the herring would soon arrive, and the busy seasons with them. This is the season that deer fawns are born, and so the end of deer hunting.

The hunting of seals and catching of spring salmon, cod and grilse supplied fresh food in March. This month marked the end of winter spirit dances, but also the holding of ceremonies by the secret Black Dance society. The society dancers painted their faces black or wore wooden masks representing the thunderbird, the wolf, and Skwanelets, the fish spirit. Tom Paul remembered that his father owned a large wolf mask with a mouth that could be opened and closed.

During this moon the people hunted brant geese, harvested clams, oysters and mussels, and harvested strips of cedar bark. Before the days of raising sheep, people used dog and mountain goat hair for spinning yarn to make clothing. The local breed of a small white woolly dog shed at this time as the weather warmed.

“Salish dog” at Tsawout in November 1935. This 14-year-old dog had been shorn each year for its wool. Diamond Jenness photograph. Canadian Museum of History Archives 79346.

Sketch of HMS Plumper in BC waters from the Illustrated London News, 1862. Note the Indigenous canoe. Author’s collection.

The first recorded European sighting of Tod Inlet dates from the British Royal Navy’s exploratory voyages of the mid-1800s. Captain (later Admiral) George Henry Richards surveyed several parts of the BC coast in the steam sloop HMS Plumper between 1857 and 1859 and in HMS Hecate in 1862. During a survey of Saanich Inlet in 1858 he gave the name “Tod Creek” to the whole area now known as Brentwood Bay and Tod Inlet.

The “Tod” refers to John Tod (1794–1882), an employee of the Hudson’s Bay Company who later became a member of the council of government for the Vancouver Island colony in 1851, and of the later Legislative Council. As both were living at Victoria in 1857, it is likely that Captain Richards and John Tod knew each other socially, as well as professionally.

Before Captain Richards explored Saanich Inlet and Tod Inlet, he served in the Arctic on one of the expeditions searching for Sir John Franklin. During the British Naval Franklin Search Expedition of 1852–1854, George Henry Richards was captain of HMS Assistance under Sir Edward Belcher. In 1852 Richards and Belcher sailed up Wellington Channel and wintered at Northumberland Sound on the northwestern peninsula of Devon Island. In the late winter and spring of 1853, Richards and his men sledged along the north coast of Bathurst Island to Melville Island and back, a return journey of 1,300 kilometres. This small party was one of the first to explore north of Bathurst Island, now the site of one of Canada’s newest national parks. Bathurst Island was also the site of the High Arctic Research Station, where I spent many years studying muskoxen and other arctic wildlife. I love the connection that Captain Richards was among the first Europeans to see Tod Inlet and also among the first Europeans to explore Bathurst Island, the two places in the world that I have spent the most time “exploring”!

But why was an inlet called Tod “Creek”? In British English, the word “creek” refers to “a narrow recess or inlet in the coastline of the sea, or the tidal estuary of a river; [or] an armlet of the sea which runs inland in a comparatively narrow channel”10 and offers facilities for harbouring and unloading smaller ships. All of these describe Tod Inlet perfectly. The use of “creek” to describe a small stream or tributary of a river is a North American peculiarity.

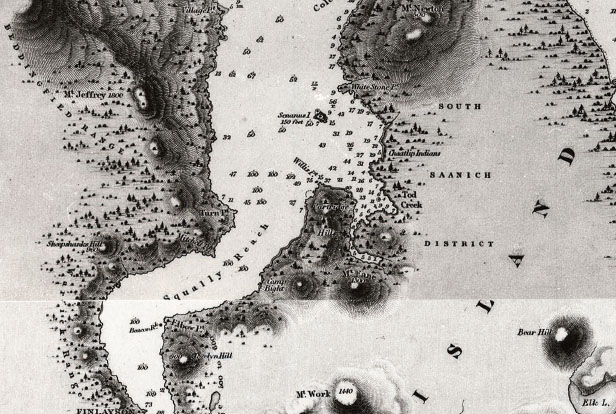

Based on Richards’s survey, the 1864 publication The Vancouver Island Pilot gives the following description of Tod Creek: “Tod Creek is 2 miles southward of Cole bay. Senanus Island, a small wooded islet, 150 feet high, lies off its entrance with deep water on either side of it. There is anchorage in the outer part of the creek in 15 fathoms. A short distance within it narrows rapidly and winds to the southward and south-east for three-quarters of a mile, with a breadth of less than a cable, carrying 6 fathoms nearly to its head.”11

By 1936 the British Columbia Pilot had applied the name “Tod Inlet” to what had been called Tod Creek, and maps now showed the name Tod Creek applied only to the stream as we know it today.

The earliest European visitors viewed lands on the Saanich Peninsula, once referred to simply as North and South Saanich, as productive lands suitable for agriculture. In his book Four Years in British Columbia and Vancouver Island (1862), Richard Mayne describes the northern part of the Saanich Peninsula as “some of the best agricultural land in Vancouver Island. The coast here … is fringed with pine [Douglas fir]; but in the centre it is clear prairie or oak-land, most of it now under cultivation.”12

In a somewhat underhanded arrangement, Sir James Douglas had “purchased” the land from its Indigenous stewards in February 1852. The Tsartlip people were not properly informed of the content and meaning of the agreement, nor were they actually paid anything other than blankets, and the “X” marks that were considered signatures all looked the same, according to Elder Dave Elliott Sr.13 The treaties Douglas signed reserved to the First Nations the “liberty to hunt over the unoccupied lands, and to carry on our fisheries as formerly” in the vast treaty area, which included Tod Inlet.

Following the first survey of 1858, 18,000 acres were marked off for pre-emption by settlers, in allotments of 100 acres for single men and 200 acres for married men. Pre-emption is the “purchase, or right of purchase, of public land by its occupant, (usually at a nominal price), on condition of his or her improving it.”14

The Pemberton map of Saanich Peninsula in 1859 shows no features at Tod Inlet. In the South Saanich District the only locations identified near Tod Inlet were “Senanus I.,” “Chawhilp Inds.,” and “Stelly’s.”

When the electoral district of Saanich, which included Tod Inlet, was created in 1858, only 21 names were on the voters’ list, and only eight represented residents of Saanich District. William Sellick (who was not actually a resident of Saanich District at that time) first pre-empted the land on the north side of Tod Inlet in 1859, then forfeited and sold it at auction to Bishop George Hills in 1861. The Right Reverend Bishop Hills, bishop of British Columbia, who arrived in Victoria in 1860, was particularly interested in land in North Saanich, and he purchased several hundred acres, including part of the present site of Sidney—probably as speculation on behalf of the Anglican church. The land the bishop purchased at Tod Inlet was sold in 1866 to a Thomas Pritchard. The land changed hands again that same year, this time going to farmer George Albert Thomas. Thomas and his wife, Elizabeth (née Watson), lived in Saanich until their deaths in 1909 and 1916.

Saanich Inlet and Tod Creek. Part of Haro Strait and Middle Channel, an 1862 map based on the surveys by Captain Richards and the officers of HMS Plumper. Engraved by J&C Walker. City of Vancouver Archives AM1594-: Map 839.

Other early farmers in the area included Peter C. Fernie, German immigrant William A. Pitzer, John Sluggett, and Peter Bartleman, a farmer and blacksmith. Bartleman’s wife, Janet, was from the Tsartlip First Nation. Their sons, Issac and Gabe, later made a significant impact on the Tsartlip community.

The land on the west and south sides of Tod Inlet was in what was originally called the Lake District because of the many lakes to the south. One of the largest landowners in that area was the Victoria Water Works.

In the 1850s, as wooden buildings were replaced by larger buildings of brick or stone, a need for lime to make mortar and plaster developed. Though farmers had long used lime for fertilizer, the use of lime as a building material increased demand for it and led to a flourishing of small lime kilns. The 1887 British Columbia Directory notes that “an excellent quality of lime is obtained in [Saanich and the Lake District], which … finds a ready market in Victoria and Vancouver.”15 Tod Inlet became an important locality for this new enterprise of lime burning.

John Greig, born in Burness, Orkney Islands, in 1825, arrived in Victoria in 1854 after working for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He bought land at Parson’s Bridge, near View Royal, built a lime kiln and went into business as a lime burner. As the limestone there was of not of good quality, “he went scouting about and discovered Tod Inlet.”16 In 1869 Greig purchased 219 acres of land there, and in 1870 he became the area’s first lime burner. He moved to Tod Inlet, built a log cabin and a lime kiln, and continued to produce lime with the help of his several sons.

The early Greig/Wriglesworth lime kiln at Tod Inlet, about 1904. The small building to the right was probably the office building for the Saanich Lime Company. BC Archives G-06193.

In a 1904 photograph (12 years after Greig died), we can see some details of this early lime kiln. As this type of kiln was fed from the top, and the lime extracted from the bottom, these kilns were often built against a hill or rock outcrop. Greig’s kiln was on level ground, so there was a ramp leading to the top, up which the raw limestone was carried to be dumped into the body of the kiln. The side wings probably offered shelter and storage space for the lime.

Greig also farmed, and his property at Tod Inlet was called Burness Farm after his birthplace in Scotland. Priscilla Bethell, Greig’s great-great-granddaughter, recalled John saying that he sold the property to his second-oldest son, Robert, for “$10 and a Stetson Hat” when the Hudson’s Bay Company began buying lime from San Juan Island rather than Tod Inlet.17 This source of competition, which hampered Greig’s business, was one of the earliest large-scale lime kilns on the Pacific coast. It was located at Roche Harbor on San Juan Island, just 25 kilometres northeast of Victoria across the American border. Greig and his wife, Margaret, lived out the remaining years of their lives at Tod Inlet. He died in 1892.

Peter Fernie, Tod Inlet’s second lime burner, is listed in the 1890 city directory as a lime burner at the Lake District. Fernie owned and farmed 60 acres on the east side of Tod Inlet, north of the main body of the inlet. The Fernie house had a foundation of rock and lime, and the farm well was a beautiful one, lined with brick.

Peter Fernie burned lime in a beehive-type kiln for use by local farmers. According to the Canada census of 1891, he employed a total of nine men, including an American named C. Kane as a lime burner and three Chinese men as wood choppers, at his lime kiln. Though Fernie died in 1892, the 1901 Canada census described him as “Head” of the family, with a servant, James Gray. Peter is listed as a farmer, James as a farm labourer.

The third of the lime burners was an Englishman, Joseph Wriglesworth, born in Yorkshire in 1840. Wriglesworth was a water diviner, a volunteer fireman and a member of the Odd Fellows fraternity. He was also a lime merchant and a lime burner at Tod Inlet between about 1892 and 1904. Wriglesworth came to Canada from England in 1862, travelling across the Isthmus of Panama. After a brief and unsuccessful foray into the Cariboo goldfields, he returned to Victoria, built the London Hotel on Johnson Street and became a businessman and politician. By 1881, at the age of 38, Wriglesworth was married with five children and living on Yates Street in Victoria.

In the May 1, 1885, Daily Colonist, there is an ad under the heading “Home Productions” that reads, “Saanich Lime and San Juan, Roche Harbor Lime for sale by J. Wriglesworth, corner of Yates and Blanchard streets.” His storefront advertised “Lime, Plaster, Hair, Cement &c.” (The hair was probably horsehair, used as a binding material in mortar and plaster.)

He served on the Victoria city council for many years, and in 1886 he ran for election to the provincial legislature. During a speech before his potential electors, he received cheers for his comment that he had no axe to grind and would take particular notice that he turned no stone to grind other candidates’ axes.

It seems that Wriglesworth prospered in his lime business, and he was described as an “extensive lime burner.” An advertisement in the Victoria Daily Colonist in 1887 offered wholesale lime from the Saanich Lime Company, in what seems to be a joint venture by Wriglesworth, Caleb Pike’s operation in the Highlands (southwest of Tod Inlet), the Raymond lime kiln near Esquimalt Harbour and Greig’s Tod Inlet kiln. Wriglesworth’s company, J. Wriglesworth & Co., was associated with the US-based San Juan Lime Company in 1889, and a year later with the Saanich Lime Company.

The Saanich Lime Company was incorporated in 1890, with Joseph Wriglesworth, William Fernie and Peter Fernie as trustees. The company was formed “to acquire by purchase, operate and carry on, and extend the lime-kilns on Tod Creek and Highland district, now being carried on at the above-named places.” The company office was at 127 Yates Street, Wriglesworth’s store and home.

The Victoria Daily Times of September 1, 1890, reported that the steamer Rainbow had brought 205 barrels of lime from Saanich to Victoria. The report is one of the earliest records of a large ship entering Tod Inlet for commercial purposes. Rainbow was a 108-foot, 150-ton steam-powered wooden schooner. After delivering the lime to Victoria, she headed to Texada Island, north of Nanaimo, to carry 436 barrels of lime to Vancouver on their way to a final destination of Seattle, Washington.

In November 1890, the Times noted that Vancouver Island lime was beginning to find a good market on the BC mainland, and that shipments from Saanich were being made quite frequently. The article, entitled “Lime Shipments,” also recorded that the paddlewheel steamer R.P. Rithet had brought over a large number of empty barrels and was leaving “for the kiln to unload the barrels and take on 800 more barrels of lime headed for New Westminster…. This shows that the people of Vancouver Island are beginning to use their lime which so long laid untouched, while San Juan Island reaped the benefit.”18

The Saanich Lime Company described their assets in the Victoria Daily Colonist in 1891 as part of a proposal to form a joint stock company to expand their works: “The property of the company is situated on Tod Creek, Saanich Arm, about eleven miles from Victoria, the creek being well sheltered and deep watered, the land comprising 435 acres…. On the land in question there are two draw-kilns of the latest pattern, and capable of burning 130 barrels of lime per day; the quarries are close to the kilns and reached by good macadamized roads, which can be used by tramways. There is also a substantial wharf, with 14 feet of water…. The buildings, outhouses, stables, and other structures are of the best material and most improved workmanship.”19 The company also had a wooden warehouse in Victoria capable of holding 600 barrels of lime.

It seems that Wriglesworth eventually bought the Greig property at Tod Inlet from Robert Greig, the son of John Greig, sometime after John’s death in 1892.20 It is not clear whether Wriglesworth bought the property for himself or on behalf of the Saanich Lime Company.

By 1892 Wriglesworth & Co. owned 225 acres of land along the north shore of Tod Inlet and Tod Creek. In 1893, the Saanich Lime Company announced that Wriglesworth had been “appointed sole agent for the sale of our Lime.” Wriglesworth sent a sample of the limestone to England for testing, and when the sample showed good potential, he tried, unsuccessfully, to interest Victoria businessmen in developing a new industry—probably the making of cement.

An 1895 map of the “South Eastern District” of Vancouver Island is the earliest map I could find that shows Lime Kiln Road—now Benvenuto Avenue. The road appears on this map as an extension of Butler Cross Road, leading west from West Saanich Road towards, but not all the way to, the shores of Tod Inlet. The next east-west roads to the north are Sluggett Road and Stelly’s Cross Road.

The Vancouver City Directory for 1896 lists Joseph Wriglesworth of Victoria, the CPR Cement Works of Vancouver, and four others under the heading of “Lime, Plaster & Cement Dealers.”

The Canadian Pacific Railway Company had decided to build a factory in Vancouver to produce cement for their construction work in Western Canada in the early 1890s. They built a factory on the shores of False Creek and began making cement. The quality of the cement was not up to expectations, so in 1894 they hired an experienced British cement worker. Within a short time the quality had improved enough to match any cement produced in Britain or Germany.

Limestone has great quantities of calcite, a common carbonate mineral and a rock-forming material. Calcite and dolomite, and the rocks containing them, are valuable sources of calcium and magnesium carbonates, which are used in the cement industry (in making Portland cement) as well as in the iron and steel refining process (as a flux in blast furnaces). Limestone is an organic sediment, derived from animal fragments compacted into rock layers. Organic limestones are formed when coral reef builders inhabiting warm, shallow seas secrete calcium carbonate. (Sedimentary limestone rock becomes marble when metamorphosed.)

Local journalist Robert Connell described the origin of the Tod Inlet limestone rock formation as “reefs girding the volcanic islands of the warm Jurassic or Triassic sea, and when the countless swarms of coral animals built them as their many-patterned homes out of the lime of the waves. And since then, in the strange transmutation of things, the contents of this quarry has passed into the walls of human habitations.”21

The Vancouver Province and the Victoria Daily Times reported in August 1896 that a new company, the Pacific Coast Portland Cement Company, had applied for incorporation to take over both the Saanich Lime Company’s location on Tod Inlet and the Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s cement works on False Creek. The Vancouver-based company was to carry on business as a manufacturer of Portland cement and lime. But the plan apparently never materialized. Tod Inlet was to remain a quiet backwater for the time being.

Through the first few years of the 20th century, there were no new developments at Tod Inlet. An article in the Victoria Daily Times on July 22, 1905, describes what a “Victoria sportsman” would have encountered at Tod Inlet at the beginning of 1904.

He … followed what is still known as the Limekiln Road, until, descending a long grade, he saw the blue waters of Todd [sic] Inlet through the foliage which grew thickly on its shores. No sign of life, or of human occupation marked the scene, excepting the scamper of a band of deer which hurried up the precipitous banks across the bay as he dropped his canoe in the water. A tumbledown wharf, a deserted lime kiln, and the almost unused road leading to them, alone marked where the hand of industry had left its impress on the spot, only to be withdrawn as if the futility of a fight with the forces of nature had been recognized.22