The Parsell family. See here.

When the president of the British Columbia Board of Trade made an announcement in December 1900 that a new cement works was to be established at Tod Inlet, it was heralded as the beginning of a new enterprise for British Columbia that would have a “profound impact on the economic future of the Province.”23 Was this going to be another announcement with no practical follow-up, as had happened at the incorporation of Pacific Coast Portland Cement four years previous? Or would the “hand of industry” once again join battle with the “forces of nature” at Tod Inlet? It seemed promising for the latter.

W.A. Ward told the meeting of the board of trade in Victoria that a property had been purchased by a man called James Keith-Fisher, and that assays showed that the materials available at the site were suitable for the manufacture of cement. So who was this new man on the scene, and what was he up to?

James Keith-Fisher was an English businessman from New York who had come to Vancouver in July 1898. By February the next year he was a newly elected member of the Vancouver Board of Trade, and in October he was listed as the general manager of the British Columbia Portland Cement Company.

In 1899, the new British Columbia Portland Cement Company leased and then purchased the cement works of the CPR at False Creek in early February. By late February the company had announced plans to bring in some five railway carloads of new machinery from Copenhagen and New York. Keith-Fisher had had the cement tested in Montreal, and the results showed a tensile strength “of rare quality” and an “exceedingly good” fineness.

The Parsell family. See here.

In the Victoria Daily Times of February 1900, the purchasing agent for the City of Victoria requested tenders for 2,000 barrels “of White’s Portland Cement, or any other brand of Portland Cement of equal quality in strength to White’s.” White’s Portland Cement was a “celebrated” brand produced in Great Britain by the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers and available in British Columbia. Until cement production began in Western Canada, cement had to be ordered from British cement companies and shipped by the barrel around Cape Horn. In the United States, no cement companies operated on the Pacific coast until about 1900. Before that, institutions, governments and industries had ordered cement from Germany.

Keith-Fisher was in New York in November 1900 and in Montreal in December. The “Personal Intelligence” column of the Montreal Gazette of December 1900 listed J. Keith-Fisher (and, incidentally, Winston Spencer Churchill) as guests at the Hotel Place Viger in Montreal. Keith-Fisher was making the rounds … and undoubtedly talking about Portland Cement.

Portland cement is a finely ground manufactured mineral product resulting from combining the raw materials of crushed limestone and clay at a high temperature. When mixed with water and sand or gravel, the powdered cement solidifies to form the solid building material called concrete.

An English inventor, Joseph Aspdin, came up with this idea in 1824. He tried mixing burned ground limestone and clay to produce an “artificial cement” that would be stronger than that produced using plain crushed limestone. His idea worked. Aspdin named this new product “Portland cement” because it produced a light grey-brown concrete, similar in colour to the building limestone found on the Isle of Portland, on the south coast of England. (The best-known use of Portland limestone was in the rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London in 1666.)

Until the early 1900s, relatively small amounts of cement had been manufactured in North America. Wood and stone had met all building requirements, and few people envisioned any widespread use for cement. However, as cement plants multiplied, the new material became more available, and the use of cement soared. Cement was used in the foundations of brick buildings, in construction of bridges and in paving of sidewalks.

The Colton Portland Cement Company, near San Bernardino, California. Postcard in author’s collection.

The first two companies to produce cement in the American West were both in California. The Colton Portland Cement Company began producing cement near San Bernardino, about 100 kilometres east of Los Angeles, in about 1900. The town that arose near the plant was actually named Cement. The Pacific Portland Cement Company started production soon after at Suisun Bay, about 60 kilometres northeast of San Francisco.

Other than the small cement plant in Vancouver, built by the Canadian Pacific Railway Company in about 1890 to manufacture Portland cement for the railway’s own use, the only cement plant in Western Canada was a small, short-lived one erected near Princeton, BC.

At about the same time in Eastern Canada, businessman Robert Pim Butchart had joined other investors in developing a proposition to make Portland cement at Shallow Lake, near Owen Sound, Ontario. This was a new venture for Canada, and notable even for the continent. Butchart, born in Owen Sound in 1856, had inherited his family’s hardware and ship chandlery business. Knowing that a local cement plant could successfully compete with cement imported from England, he launched into cement production. This first venture at Shallow Lake was a failure. The bricks lining the kilns were unable to withstand the high temperatures needed to burn the limestone in the kilns. After consulting with a distant relative in the cement business in England, Butchart tried a different type of kiln and went on to build and operate two successful cement plants in Owen Sound and Lakefield, Ontario.24

Sensing a profitable new market, Butchart then turned his attention to the west. His interest in the western market led to the cement plant that he is best known for—the first large successful cement plant in British Columbia.

Butchart and his wife travelled to BC in 1902 to investigate the prospect of establishing a cement factory on the West Coast. He was undoubtedly aware of the lime-burning industry in British Columbia, and as an astute businessman, he would have been following the movement towards the manufacture of cement in Western Canada. Although I have found no record of such a meeting, I suspect that Butchart would have met with James Keith-Fisher and Joseph Wriglesworth. His investigation complete, Butchart returned to Ontario and set the wheels in motion to purchase land at Tod Inlet and establish the Vancouver Portland Cement Company Limited.

The new company was incorporated under the Dominion of Canada Companies Act in 1902. Its official purposes and objectives were “to search for, make merchantable, manufacture, use, produce, adapt, prepare, buy, sell, and deal in Portland cement and all kinds of natural and other cements and products into which cement enters either as a part or as a whole, and all kinds of building materials, and to dig, mine, dredge, or otherwise procure earth, marl, clay, stone, artificial stone, shale, slate, clay granite or other materials necessary to the manufacture of cements, building materials and other products aforesaid.”

The property the company purchased for the new cement works was the land that had been previously owned by John Greig and later, at the time of purchase, by Joseph Wriglesworth’s company. This was the area along the north sides of Tod Inlet and Tod Creek. (The land was subdivided into “sections” within “ranges”; in this case the property was in Section 15, Range 2W, where “W” means west.) The purchase included the lime kiln and quarry formerly operated by the lime burners.

The purchase of the old lime-burner property was complex. Property records show that by 1901, the old Wriglesworth property—once John Greig’s—belonged to James Edward Murphy of Meaford, Ontario. Butchart’s new company purchased 246 acres from Murphy in 1903. And who was Murphy? He was a colleague of Butchart’s and a vice-president of the Vancouver Portland Cement Company, of which Butchart was the managing director. Keith-Fisher, who was said to have purchased this property in 1900, never appears in the ownership records, and soon disappears from the scene. It seems that he went back to England, though his name still appears occasionally in newspapers as he travelled between Europe and the US.

At first the new cement company’s head office was on Toronto’s King Street. But by the time the plant was under construction, the company had set up a new headquarters on Bastion Street in Victoria.

A 1903 letter from Robert Butchart to William E. Losee, then manager of the Lakefield cement plant in Ontario, confirmed the decision to proceed with the cement plant at Tod Inlet. Construction began in June 1904. It was an early step at the beginning of a new industry in BC, and it would bring a new prosperity, and a promising new community, to the Saanich Peninsula.

The Vancouver Portland Cement Company brought in experienced personnel from Ontario to oversee the construction of the plant and to manage the production of cement. Two men, Robert Vincent and Charles Carney, came to Tod Inlet from the cement plant at Shallow Lake to help build the new plant. William Losee, from the Lakefield plant, was engaged as plant superintendent.

Chinese labourers working with barrels of cement during the construction of the plant in 1904. BC Archives.

The wharf and the partially constructed cement plant of the Vancouver Portland Cement Company at Tod Inlet, 1904. BC Archives I-56386.

Chinese workers constructing the first plant buildings in 1904, looking south. BC Archives.

One of the first priorities for the building of the cement plant was the construction of a substantial wharf suitable for receiving shipments of building supplies and the machinery needed for the mill. The old wooden wharf belonging to the Saanich Lime Company was undoubtedly useful at first, but a larger, stronger structure was needed.

The first wharf was constructed of wood early in 1904 so that equipment for the plant could be unloaded and moved into the building before construction was completed. It was about 11 metres wide and 60 metres long.

Designed to accept scows or barges on both sides, the end of the wharf was at just the right height so that loaded railway cars could be pulled from a barge onto one of three sets of tracks on the wharf. These tracks in turn led right into the plant building. The kilns, dryers and other machinery for the growing plant were all brought to the site on barges towed by tugs.

From the earliest photographs of the plant, we know that Chinese workers were involved in construction of the first buildings. Among them may have been some of the men whom Peter Fernie had employed at his nearby lime-burning operation.

There is no official record of the Chinese members of the community at Tod Inlet until the Canada census of 1911. This is not unusual for early non-white communities in British Columbia. It is typical of the province at the time that for as long as the village of Tod Inlet existed, the directories for Vancouver Island’s communities listed the names and occupations of the white male inhabitants, but never listed any of the Asian immigrants, and seldom listed women. For Tod Inlet the existence of the Asian immigrants is mentioned in directories only once, in the Vancouver Island Directory for 1909: “Nearly 200 Orientals located here.”

Little is known of how the 200 or so Chinese workers originally came to Tod Inlet. The large number of them suggests they were probably hired through one of the companies specializing in bringing Chinese workers to British Columbia for various building projects, including the Canadian Pacific Railway.

As well as workers from Ontario and China, some local inhabitants were also hired. Wilfred Butler, who ran the store at the corner of V&S (now Veyaness) Road and Keating Cross Road, had the first contract to haul freight down to Tod Inlet. He used a big old wagon as a stagecoach to run supplies and people from the Keating Station of the Victoria & Sidney Railway to Tod Inlet. His first job was delivering a load of sand to the site, undoubtedly for mixing with cement as the buildings were constructed.

A First Nations dugout canoe on the wharf of the partially constructed cement plant, 1904. BC Archives I-56386.

The Vancouver Island Directory for 1909, the first to list the new community at Tod Inlet, gives an idea of the range of jobs performed by the men at the new cement plant. The most numerous were for the labourers at the plant (jobs taken by the “200 Orientals”). The 15 other jobs listed included oiler (there were 6), miller (3), then blacksmith, engineer, kiln burner, machinist and teamster (2 each), plus a manager, superintendent, chief engineer, chemist, clerk, coal grinder, carpenter and boilermaker.

As the plant went up, the new community of Tod Inlet began to grow, first with the builders, then the workers, and eventually with some families. The immigrant workers, however, didn’t enjoy the “privilege” of families at that time. There is no official record of men from the Tsartlip First Nation working at the plant, although an early photograph of the plant under construction does show a First Nations dugout canoe on the wharf.

The actual construction of the cement plant began in June 1904, with a large number of employees working double shifts. The factory was built on level ground between the shore of the inlet and the new quarry. In its first phase the cement plant consisted of five lime-concrete buildings grouped together, some sharing a common wall. The lime for these buildings was burned in the old lime kiln built by the former owners. The concrete walls were about six metres high, and in those buildings where the process created much dust, the walls were surmounted by a wooden framework about two and a half metres high. This open space, between the concrete wall below and the horizontal beam or wall plate above, was filled with wooden lattice work, allowing ample light and ventilation. The five buildings of the plant’s first phase were the coal house, the mill (including the kilns and grinding mills), the engine room, the boiler room and the stock house.

It seems that at least some of the cement used in building the plant itself may have been imported. In photographs, Chinese workers can be seen mixing and spreading cement from the standard 350-pound barrels that imported cement traditionally came in at that time.

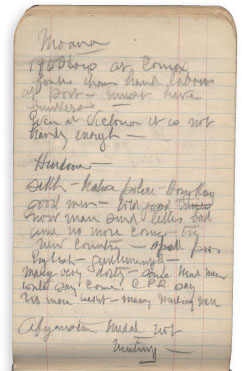

Robert James Parsell, an engineer, was hired to help install machinery in the plant. Parsell was the son of an engineer, and his father worked on the Great Lakes steamship Chicora. The Parsell family had arrived in Vancouver by train from Toronto in 1901 and made their way to Victoria on the CPR steamer Charmer. Parsell worked as an engineer on Victoria’s Outer Wharf. But when he heard of the plant being built at Tod Inlet, he joined up as a fitter and an engineer. Parsell left Victoria on March 3, 1905, on the Victoria & Sidney Railway’s train. He covered the last five kilometres to the plant on foot, because there was then no transportation from the Keating railway station to Tod Inlet.

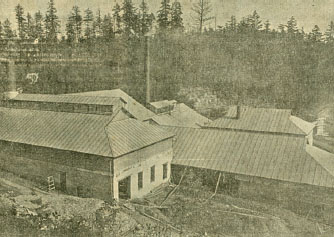

The cement plant under construction, looking east from the ridge, pictured in the Victoria Daily Times, 1905. Author’s collection.

Mary Parsell, James’s wife, was one of the first women to live in the village of Tod Inlet. Her memoirs, though written in 1958, are an important first-hand source of information on the people and early growth of the new community.

The CPR SS Charmer at Tod Inlet, about 1905. BC Archives.

Drilling in a limestone quarry, possibly at the Bamberton cement works. Still from the film The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement (BC Archives AAAA6718, 1963), presented with permission of the Lehigh Hanson Cement Company.

Positioning dynamite in the quarry. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See above.

While the plant buildings were going up, the new quarry was being prepared for the extraction of limestone. The Tod Inlet limestone deposit was a ridge running parallel to the inlet only about 300 metres from the shore, behind the new buildings. The new quarry was the second to be developed in the deposit. The first quarry was the one worked in 1869 by John Greig, then sold to Wriglesworth’s Saanich Lime Company. Although it was part of the lands purchased by the Vancouver Portland Cement Company, it had little suitable limestone left and was not used.

To expose the raw material, the labourers had to strip off the forest growth and the surface soil, which was less than a metre deep. The men drove an open cut 60 metres long and 6 metres deep through the overlying clay between the plant and the limestone, and two men opened up the new quarry with a steam drill along a 12-metre face. Their main technique for removing limestone was drilling followed by blasting.

After blasting, the Chinese labourers excavated the raw limestone by hand. It seems likely that the quarry workers would have also broken up the larger chunks of limestone after the blasting, before loading it into steel tram carts that they pushed downhill on the track to the storage bins at the plant.

Although there were more than 200 Chinese labourers at Tod Inlet, discovering their personal stories has been more than difficult. After some 50 years of off-and-on searching, I still know only the stories of just three men out of the hundreds, and only a small part of those.

The earliest personal story from the Tod Inlet Chinese community is that of Chow Dom Ching. Lorelei Lew, Chow’s granddaughter (whom I only met in 2017), has recorded her grandfather’s history. He worked at Tod Inlet between about 1903 and 1906 and had paid the Chinese head tax, which was a fortune at that time, to enter Canada. “Grandfather Chow was one of the Chinese supervisors at the Butchart’s limestone quarry and was very well paid. He helped hire Chinese workers for the quarry.”

Victoria architect and former mayor Alan Lowe told me of his grandfather, who also worked in the limestone quarry at Tod Inlet: “My grandfather’s name was Lowe Sai. They used to have our surname first, so his name was Lowe Sai…. My grandfather was born in 1888 in China. Initially, because of the Exclusion Act, he was unable to bring any family members over. And when my grandfather arrived in Canada, he paid the $500 head tax…. He came to Canada to look for prosperity … to look for a place so that his family could have a better life. He worked with the … cement factory back then, working as labourer…. That was probably in the early 1900s. He was probably not more than 20 years old. He went back to China to get married. He probably went back two other times, and he had two sons, one of them being my father. My father did not get to come to Canada until the Exclusion Act was lifted … so it was many, many years that my grandfather was away from China. He became a gardener for the well-heeled Caucasian families in the Uplands in the Oak Bay area.”

Many Chinese workers were in Canada just to make enough money to escape a life of poverty at home. When they had earned enough, they would return to China. For this and other reasons, few brought families with them. Also, fearing massive immigration from China, the Canadian government had passed the Chinese Immigration Act in 1885. This act established a head tax of $50 for each Chinese immigrant. At this time there was widespread opposition to Chinese workers coming to Canada, with the often-expressed fear that they would take jobs from settlers and immigrants from Europe, primarily Great Britain. The imposed tax was increased to $100 in 1900 and $500 in 1903, making it increasingly difficult for immigrants to bring their families. This resulted in a disproportionately male immigrant population.

For example, in 1902 Vancouver’s Chinese community was composed of 2,053 men and only 27 women, all of whom were married. For Vancouver Island’s Nanaimo District, which included Saanich and Tod Inlet, the 1911 census listed 2,889 men and 45 women who were born in China. Many of these men were employed in the coal mines in Nanaimo and Wellington.

Although most of the Chinese workers remain unknown and nameless, the story of Yat Tong, who worked at Tod Inlet for over 50 years, is well remembered by the people who grew up at Tod Inlet and by his former colleagues. Tong came to Canada in the early 1900s on one of what he called the “slave ships” from China. He worked on the railways until he became alarmed at the number of fatal accidents, then left to work at the cement plant in about 1912.

By the end of March 1905, the cement plant buildings and equipment were ready and the necessary personnel hired to start the manufacture of cement, just 10 months after beginning construction. Within another month, after testing, adjusting and likely more testing, quality cement was being produced.

The newspapers of Victoria and the province made no announcement of the plant being completed, nor of the first cement being bagged. We can imagine the community gathering, waiting to hear the machinery start up, making an occasion of it. But was there an official opening ceremony? Did Robert Butchart invite the company directors or shareholders to an event? Did the mayor or the premier attend? It seems not. The only announcements made were of the first shipment of cement from Tod Inlet in April 1905: the Victoria Daily Times tells us this first shipment was on board the barge Alexander, towed by the tug Albion.

So this major development in a large and promising new industry for British Columbia seems to have passed almost unnoticed. This is not really surprising, as the average citizen had little experience of cement and limited understanding of how it might be used.

One of the first recipients of the new cement from Tod Inlet, sold as “Vancouver Brand” in honour of Captain George Vancouver, was the city of Victoria. As part of a new street improvement project, Yates and Johnson Streets were to receive cement sidewalks—cement from Tod Inlet!25 A few months later, probably after people began to walk on the new cement sidewalks, interest increased to the point that there were excursions by boat to Tod Inlet and tours of the plant. Cement became a product people wanted to learn about.

In 1902 Robert Butchart had bought 19 acres of land north of the shores of Tod Inlet from Peter Fernie, the local farmer and former lime burner. The purchase included the Fernie farm and the Fernies’ small wood-frame house.

Fernie built a new house close to Tod Inlet, and the Butcharts lived in the Fernie cottage during the summer while they planned and built a stately new house closer to the cement plant. With his wife, Jennie, and their two daughters, Jennie and Mary, Butchart settled there permanently once their house was completed.

Soon after their house was built, Jennie began to organize a series of topical gardens around the house. It wasn’t long before the tours from Victoria, which came to visit the cement plant and learn about the process, also came to enjoy beautiful Tod Inlet.

One of the first records of formal tourist excursions to Tod Inlet dates from 1905. In July of that year an advertisement in the Daily Colonist announced an “Excursion to Tod’s Inlet on Saturday, August 5, including Inspection of Cement Works.” The excursion, organized by St. John’s Church, also included a “sail through the islands” and a “concert on board” the steamship City of Nanaimo, all for the price of 75 cents for adults and 50 cents for children.

The Tod Plant had been only open for four months when Robert Butchart, the managing director, was off on another business venture. In August 1905, the Victoria Daily Times reported that an R.P. Butchart had decided to begin the manufacture of Portland cement at Calgary, then still part of the Northwest Territories, to meet the demands of the prairie towns for cement. He had spent six weeks in the territories looking for an appropriate location and the right combination of natural materials. “The new works will not require Mr. Butchart’s direct attention for some time. He will, therefore, be in a position to give the Tod creek works his immediate supervision.”

Robert Butchart’s business interests were varied and numerous: timber, steamship lines, hardware, and firebrick and fireclay companies, not to mention cement. He served on boards as adviser or director, and he was also becoming known as a philanthropist. Butchart also loved fast cars and elegant yachts. He had joined what was to become the new Victoria Automobile Club in March 1905, a time when there were still very few automobiles in British Columbia, and was elected to two of the club committees. Butchart’s yachts were among the first pleasure craft in Tod Inlet.

After the Tod Inlet plant was finished, the Chinese labourers were mainly employed in excavating the raw limestone from the limestone quarry—by hand, as this was before the advent of the steam shovel. In those early days, safety precautions were few, and accidents were all too frequent. A tragic and fatal incident in the quarry was remembered by many because it was characterized by sacrifice.

Former cement worker and gardener Pat van Adrichem heard the story from his Chinese colleagues when they worked together in that same quarry. He shared that story with me in an interview in 2007: “In wintertime they used to heat the dynamite in a pail over the fire. Then they would stuff it in a hole…. It would go pretty quick-like…. One time this guy waited too long. One of what they call the straw boss, which was Chinese, he seen what was happening, so he grabbed the pail and ran with it, but it blew before he could get rid of it.”

Mary Parsell recalled the same incident: “Sing, boss of the Chinese crew, noticed that the explosive which had been placed by the fire to warm was becoming too hot. He grabbed the explosive up in his arms and started to run but before he had gone far it exploded blowing him to bits. Undoubtedly he saved the lives of many others at the expense of his own.”26

The Victoria Daily Times also published the news of the death of a man named Sing—perhaps the same incident—in September 1908: “Kop Sing, a Chinaman, was yesterday taken to St. Joseph’s hospital suffering from the result of injuries received at the Tod Inlet cement works. He died about 5 o’clock.”27

Mike Rice spent time at Tod Inlet with friends as a youth, and he lived and worked there in the 1950s. He was impressed by the “endless” lines of Chinese workers as they walked in single file from the plant up to their village at lunchtime. Rice was still upset, some 70 years after the fact, by the way the Chinese workers had been exploited. In an interview for the Sidney Review in 1987, he noted that for their high-risk work in the quarries, including the use of dynamite, the Chinese were paid roughly half what Canadian employees were, which was typical of the times. They were also forced to pay a part of their wages to the “bossman,” an interpreter and foreman for the Chinese crew. The Chinese never had any key position apart from this bossman. “Some worked night shifts. There was a greater number of Chinese than white folk working there. And a lot of the Chinese became very skilled. But they weren’t treated the same as us—not by any stretch of the imagination.”28

The labourers at the cement plant were paid 10 cents an hour for both straight time and overtime. They worked 10 hours a day, six days a week, and were paid out once a month.

Norman Parsell, Mary’s son, also remembered Chinese funeral processions. When the hearse took the deceased away, the mourners scattered thin rice paper along the road, each piece with many holes punched in it. Norman was told that these holes made it difficult for the devil to reach the dead man, since he had to pass through each hole first.

It was through the discovery of a single photograph in Canada’s national archives in 1978 that I first learned the Chinese were not the only immigrant workers at Tod Inlet. The photo of a Sikh cremation ceremony at Tod Inlet in 1907 opened a whole new chapter of the story for me.

From Mary Parsell’s memoirs I learned of the arrival of 40 “Hindu” workers at Tod Inlet in 1906, and the effect of this new cultural contact: “To us they were a strange looking company of men with their long beards and their strange head coverings. They used to stare at the women as if we too were something quite different being without veils. In the evenings they used to gather in the field at the back of our house and sing sad and mournful songs.”29 What Mary was hearing was the Sikh devotional and communal singing called “kirtan.” Normally sung in the Sikh temple or gurdwara, these songs are not necessarily sad or mournful. Kirtan can be done anywhere Sikhs may gather when there is no gurdwara.

The Sikh cremation at Tod Inlet, 1907, as it appeared in the Canadian Courier magazine. Bonnycastle Dale photograph.

At this time in Canada, all immigrants from India were called “Hindu,” regardless of their religion. This was not just common practice but official policy: in a 1907 amendment to the Provincial Elections Act, the legislative assembly of the province of British Columbia declared that “the expression ‘Hindu’ shall mean any native of India not born of Anglo-Saxon parents and shall include any person whether a British subject or not.” In fact, many of the men described were of the Sikh faith.

The discovery of the one photograph was tantalizing, but initially led me nowhere. I could find no other reference to the Sikhs and there were no personal names. Hoping to learn more, I ventured to the Victoria gurdwara on Topaz Avenue. There the Granthi—the reader of the Holy Book—directed me to the elders’ house, where I met Amrik Singh Dhillon. He recalled for me the stories of friends of his father who worked at the cement plant, and gave me the names of their descendants.

Meeting Amrik was the beginning of a long search that slowly and steadily brought to life the story of this unique group of immigrants. He told me about the two ships that brought South Asian immigrants to Victoria and Vancouver in 1906. The people remembered the ships they arrived in not by the ships’ names, but by the number of South Asians on board: they called them “the 700 boat” and “the 800 boat.” These ships were the CPR trans-Pacific steamers Monteagle and Tartar.

Records at the gurdwara show that the Tartar brought a large number of people from Jandiala village (in the Jullundar district of Punjab), including Hurdit Singh Johl, Sadhu Singh Johal, his uncle Diwan Singh Johal, Partap Singh Johal and Takhar Singh Johal. All of these men worked at least briefly at the Vancouver Portland Cement Company plant at Tod Inlet.30

In this group also were Hardit Singh and Gurdit Singh (Dheensaw), from the village of Moron in the Punjab. Hardit and Gurdit Singh originally used Moron, the name of their village, as an identifying name. This was changed to Dheensaw at the request of their children when the meaning of the word in English was pointed out. (It was only in the 1940s and 1950s that the use of Singh as a last name, a traditional Sikh practice, began to be replaced by using the name of their home village and keeping Singh as a middle name.)

Jeet Dheensaw, son of Hardit Singh, shared with me, in an interview in 2007, the stories of their travels he had heard from his mother: “Why my father and my uncle left India … to get a better life, which they didn’t know they were going to get. They were very frightened and scared. They had heard stories of a vast land, open spaces, and just opportunities to do something … more than just living in the village, just tilling your own little farm, year after year and just surviving. Sikhs are quite industrious and adventurous … get itchy feet I guess, that’s what they had in them.”

Sometime before August 1906, the first group of Sikhs came to work at Tod Inlet, primarily as labourers, some likely as stokers and firemen for the plant’s furnaces and kilns. The Nanaimo Free Press of September 4, 1906, reported, “Hindus are now employed at the cement works at Tod inlet. If their immigration is allowed to proceed with, it will not be long before they become as serious a competitor as the Chinaman.”

The only first-hand account of the arrival of a group of Sikhs that I have found comes from a 1960 radio interview with Gurdit Singh Bilga, recorded by Laurence Nowry and held in the archives of the Canadian Museum of History.31

In 1906, when Gurdit Singh Bilga was only 18 years old, he heard about this new country called Canada, which was open to people from India. When he heard that you could earn a dollar a day, equivalent to three rupees, a great daily earning in India, he decided to make the trip. When he arrived in Victoria in October 1906, there were more than a thousand people from the Punjab already in Canada, and many were unemployed. The job situation was particularly bad in Vancouver and Victoria. He described his visit to Tod Inlet: “When we landed in Victoria, I heard there is a cement mill about 20 miles from Victoria. There is one of our friends, who is come from our village, he was a foreman over there. So we, about 30 or 40 people, go to that cement mill.” They learned that people working there were getting a dollar and a quarter a day for 10 hours of work. “So … my friend tried to the mill owner, if they could hire some more people. But unfortunately, is another foreman beside my friend, and some his friends coming the same ship as we coming. They went to the mill owner, they offer, they can supply the man for dollar a day. So he get the job, we been refused.”

Gurditta Mal Pallan, from his passport. Courtesy of Rupee Pallan.

The second group of Indian immigrants, mostly Sikhs, came from Jandiala in the fall of 1906. Among them was Gurditta Mal Pallan, a letter writer. He came straight from India with five or six people, male friends who travelled together on a ship from Calcutta (Kolkata) to Hong Kong. There they changed to a CPR ship headed to Victoria and Vancouver.

Mukund (Max) Pallan told me about his family history in a series of interviews in 2007 and 2008: “And my father, Gurditta Mal Pallan, came to Canada in 1906 with a group of people from the same village, Jandiala, where he used to live. Actually five people started together. They decided to come to Canada because a few of their friends, they were already here—they wrote back and said, ‘Come on over. It’s a big country, lots of jobs, and you will be happy here.’”

Victoria businessman Mony Jawl told me about his grandfather: “Well, my grandfather Thakar Singh emigrated from the village of Jandiala in the state of Punjab, in India, to Canada in 1906. He came with a group of others who were asked to come out to provide labour at the lime quarry at Tod Inlet. My understanding is that there were at least 10 or 12 people that were required and they were recruited from the village where my grandfather lived. They came to this country together, to work there.”

Jawl’s sister, Jeto Sengara, of Vancouver, also shared stories of Singh’s arrival in Victoria: “I remember when my grandfather Thakar used to tell us stories … about when he first came to Canada. They didn’t know where to live and there was no place to go. There was no temple at the time, so they pitched tents right where the Empress Hotel now is. And the group of men that had immigrated with my grandfather, they pitched tents there. There were mud flats there, and that’s where they lived and slept … My grandfather walked all the way up to the cement plant by Butchart Gardens.”

When G.L. Milne, medical inspector and immigration agent, was making inquiries in 1907 of some firms that had employed “Hindoos,” he contacted the Vancouver Portland Cement Company. He reported that the company “spoke rather favourably of them as they were a competitor with the Chinese who were inclined to strike for higher wages at times, and by their presence kept the wages at the usual rate of $1.50 per day.”33 Milne also referred to “another peculiarity of the Hindoo, they are divided into numberless ‘Casts’ which is a great hindrance to their being employed in numbers.”

Some of the men who came to Canada from the Punjab after 1904 were recruited by Canadian Pacific Railway agents in Hong Kong and Calcutta (Kolkata). Others were encouraged by individuals who may have seen immigration as a means of increasing their own incomes, such as Dr. Kaishoram Davichand. He was a Hindu Brahman doctor who had come to Canada in about 1904, with his young son and his wife, then said to be the only Hindu woman living in Canada. At an exhibition in Seattle, Washington, in 1905, Davichand and his son were offering “eastern palm reading” to visitors.

By 1907 he was encouraging immigration from his home country. He seems to have had an arrangement with several sawmills in the Vancouver area to supply men to work in the mills. As well as writing to villages where he was known or had relatives, he also sent tickets to men in these villages to encourage them to emigrate.

In July 1906 the Vancouver Daily World reported that Davichand had gone to Victoria in response to a letter from the Vancouver Portland Cement Company who wanted him to get “a number of Hindoos to work for them.”32

With encouragement from both individuals such as Davichand and companies like Canadian Pacific, immigration from India expanded until there were some 5,000 Sikhs in Canada by 1908. Most of them came in 1906 and 1907. The people who immigrated were mostly Sikh farmers and landowners, all from the same area of Punjab. In fact, many came in groups from the same villages.

But Milne was not well informed about the Sikh and the Hindu religions. His conclusion that “the Emigration of a large number of Hindoos into this country would not be desirable” was based on a lack of understanding of Sikhs and of the Indian caste system and was illogical at best. Sikhs, of course, have no caste system; even if they had, it is hard to see how this would have affected their usefulness as workers. Those who employed them described them as hard workers of good character. That good character, and the ability to withstand hard work and long hours, would be necessary in the harsh conditions inside the cement plant.

At the beginning, the cement plant at Tod Inlet had a powerhouse attached to the mill room with a battery of five tubular boilers fired partly by wood and partly by slack coal, which generated the steam necessary to run the plant machinery. “Slack coal” refers to small or inferior pieces of coal that burn at a high temperature, suitable for use in burning limestone—especially in cement factory kilns that process limestone.

Norman Parsell remembered that in the early days of the plant, before the switch to electrical power, the plant used steam engines of various sizes, some very large. “They had a large block of coal-fired return tubular boilers and the firemen and stokers were mostly East Indians.” When the plant was operating at full capacity, there were 11 engines to keep in order. A large Corliss steam engine drove the main power belt that operated the mill. There were smaller engines for individual phases of cement making. Norman’s father, engineer James Parsell, would move from one to the next, checking them when on duty.

Mary Parsell told a story in her memoir of a potentially fatal accident in the mill: “One night when my husband was on duty in the engine room, he was walking around to the various machines to see that each one was functioning properly … As he walked past the door opening into the mill he saw Fred Chubb standing pale and dazed looking, clad only in a suit of underwear. Upon enquiry as to what was the matter, Fred pointed to the huge fly wheel spinning around and around and said, ‘I have just been around on that.’ He had caught his sweater sleeve on a set screw and in a second he was caught up and whirled around. I do not know how many times he was carried about on that wheel but I know that his sweater was almost reduced to its original yarn and his new overalls were in ribbons. It was a miracle that he survived. Yet, with the exception of a few bruises and scratches, he was unhurt. Recently he was telling my son about this incident and he said that my husband took off his coveralls and gave them to him to wear.”34

John Hilliard Lewis wasn’t so lucky. Working in the mill room on a mould for the cement piers, he ducked under a moving belt while going down into an excavation. He was struck on the head by the bolts holding the ends of the belt together. He died the next day from a fractured skull, according to the Victoria Daily Times for December 4, 1905.

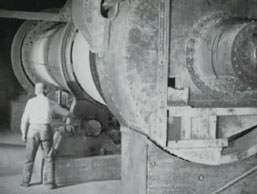

The largest and most complicated building in the cement plant was the mill room, where the large cylindrical crushers, rollers and kilns transformed the raw limestone and clay into cement.

When the men in the limestone quarry had finished loading the tram carts, they pushed them down the rails to the mill room, the first of the plant buildings. The tram-lines ran over a line of separate storage bins for raw clay and limestone, and into the crushing plant. The clay and limestone were carried separately on the tram-line and went on different paths into the plant.

The rough limestone rock was sent first into a crushing plant known as a Gates crusher. From there the crushed limestone was discharged into a rotary dryer, a hollow, wrought-iron cylindrical shell 1.5 metres in diameter and 13 metres long. The dryer rotated on tires, with a slight inclination down from the feeding end. It was heated in part by hot waste gases that were fed back from the kiln into the dryer. These gases passed into the lower end of the dryer, meeting the crushed material and drying it, then passed out the upper end into a separate brick chimney stack that was 19 metres high. As the cylinder revolved, the crushed material travelled through the dryer and was discharged automatically.

The crushed and dried limestone then passed from the rotary dryer into a screw conveyor, which carried it horizontally to a bucket-elevator. The elevator fed the partially crushed limestone into the Krupp ball mill, a horizontally revolving iron shell about two metres in diameter and two metres long. In the mill, which was lined with a heavy chilled-iron screen, were round steel “cannonballs.” As the mill revolved, the cannonballs rolled over and through the crushed limestone, grinding it to a fine texture. From the Krupp mill another screw-gear raised the fine limestone and deposited it into a storage bin capable of holding 50 tons.

The clay arrived at the plant over the same tram-line as the limestone, but went directly into a Potts disintegrator, where a pair of rollers with revolving knife-like teeth disintegrated the clay. From there it passed into the same dryer into which the limestone was fed. The dryer was used alternately for limestone or clay, as required. The clay, already fine enough and needing no further grinding in the Krupp mill, went directly from the dryer to the ground-clay stock bin, located beside the ground limestone bin.

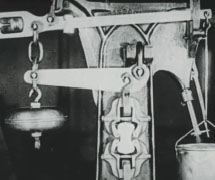

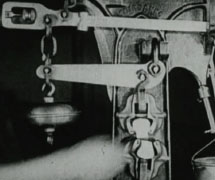

The dryers in the plant. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

The ball mill. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

At this point the materials, which until this point had been treated and handled separately, were mixed. The men weighed the desired amount of both limestone and clay and gradually discharged the materials into a horizontally placed screw conveyor, which thoroughly mixed the two ingredients. From an elevated hopper bin, the mixed materials were fed down into two tube mills for further mixing and grinding.

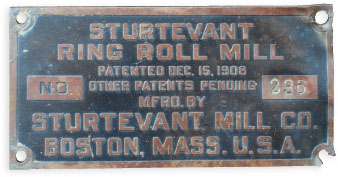

Manufacturer’s plate from a 1908 roll mill at Tod Inlet. David R. Gray photograph.

The tube mills were iron tubes about 1.5 metres in diameter and 7 metres long, lined with hard flint stones embedded in cement. When the tube was rotating, larger round flint pebbles would roll over and through the ground limestone and clay, thoroughly mixing and grinding the materials. Next, the materials were fed into the rotary kiln, a horizontal iron tube mounted on rollers, 2 metres in diameter and 22 metres in length.

The noise in the plant must have been deafening. A contemporary account of a visit to a cement mill described the noise as the material was fed into the rotary kiln as “a rattle and din much resembling the discharge of musketry.” Difficulty with hearing, if not outright deafness, must have been a constant risk for the many workers who spent 10 hours a day, if not longer, in the mill.

The kiln, lined with firebrick, was heated to a temperature of 2,700°F (1,482°C) by the burning of fine, dry coal dust. As the kiln rotated, the crushed limestone and clay slowly passed through and were fused together by the heat, forming the “cement clinker” that when pulverized would become cement.

The kilns at the Tod Inlet plant. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

Looking through the kiln door. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

The cement plant showing the first brick chimneys, about 1906. Author’s collection, from BCCC photo album.

To break up large clumps of clinker without entering the kiln, workers fired a large kiln gun through the open door. The additional noise, as well as the heat the workers would endure with the kiln door even briefly open, is almost unimaginable.

The hot gases from the kiln were directed to the large central chimney stack. The first main stack at Tod Inlet was made of brick and stood 26 metres tall. Some of the hot gases were conducted back to the rotary dryer, providing enough heat to dry the incoming clay and limestone, and probably heating the building beyond comfort as well.

Next, the red-hot clinker went into the rotary cooler, another revolving iron cylinder about 1.5 metres in diameter and 15 metres long. The rotary cooler was set on an incline, and as cool air was let in, the clinker cooled as it moved down the tube. When the clinker was cool enough to permit handling, it was mainly the Chinese and Sikh labourers who screened out any large clinkers and broke them up with sledgehammers.

Looking into the kiln at the lumps of forming cement as they tumble with the rotation of the kilm. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

Adding gypsum to the imestone powder. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See here.

Jeet Dheensaw relates his family memories of the work: “It was hard, dusty, breaking rocks, like breaking rocks and stuff, nothing by machinery…. They never had any machinery there.”

After the cement left the cooler, the workers added gypsum to the mix. Gypsum was a necessary ingredient that acted to slow the setting time of the cement. The company had to bring gypsum in from various sources: Vancouver, Alaska, California, even France.

After being broken up by hand, the combined material was fed into a Bonnet ball mill, 1.5 by 2.5 metres in size, where it was partially crushed. From the Bonnet mill a screw conveyor took the material to another tube mill for final crushing to the level of fineness required for the finished product.

From the tube mill the cement went into storage bins in the adjoining stock house to await sacking. From the bins, men poured the cement into 87.5-pound (39.7-kilogram) sacks for storage or shipment. A bag warehouse and sack cleaner room provided more storage and workspace for handling the sacks. The new method of shipping 87.5 pounds of cement in burlap sacks was based on the old barrel system: four 87.5-pound sacks weighed 350 pounds—the same as the old “barrel” of cement.

Gypsum is a sedimentary rock formed from the evaporation of salt water. It is found in large deposits worldwide at sites where there has been evaporation of sea water. A mineral containing sulphur and oxygen, in its massive or solid form it is called alabaster. As well as being important for making quick-setting building cement, gypsum is also used in the manufacture of plasters (including plaster of Paris) and plasterboard. Some of the gypsum brought to Tod Inlet from Alaska probably came from the Pacific Coast Gypsum mine, on Chichagof Island, Alaska, near Juneau in the Alaska panhandle.

Loading bags of cement on the wharf at Tod Inlet in 1907. Bonnycastle Dale photograph. Courtesy of Kim Walker.

Gurditta Mal Pallan’s first job at Tod Inlet was to fill the 87.5-pound bags with cement powder and carry them half a block to a waiting scow. He was a strong man and could handle the heavy work easily, but the dust compromised his lungs, so he looked for another job. By Christmas of 1906 he had moved to downtown Victoria and found work with BC Electric installing streetcar tracks, working 10-hour shifts for 10 cents an hour.

One of the newspaper reports relating to the Sikhs of Tod Inlet was a somewhat sensational article that appeared in the Victoria Daily Times in August 1906.

Under the headings of “Hindus are in Great Distress” and “Being Cared for by City Until Decision is Reached as to Their Disposal,” the article starts with “Hindu Invaders have struck Victoria.” The writer describes how 15 Sikhs had left the employment of the Vancouver Portland Cement works at Tod Inlet, walked to Victoria and camped on Fourth Street without tents or food. When concerned citizens appealed to the mayor of Victoria, police constables brought the Sikhs to the patrol shed at city hall. The reporter gives us one of the few written descriptions of the early immigrant Sikhs and their belongings: “Heavy brass basins here and there and a large black pot of rice are the only evidences of food…. Only one speaks even imperfect English. He is an old man, a former member of one of the Sikh regiments and bears on his breast an imperial medal for one of the Chinese campaigns…. They attempted to work at Tod Inlet, but could not stand the dust. Complaints of bronchitis and throat troubles seem to be the chief cause of their quitting.”35

Sikhs at the Tod Inlet wharf with scarves around their necks to combat the cement dust, 1907. Bonnycastle Dale photograph. Courtesy of Kim Walker.

Gurditta Mal Pallan told his son Max about how the people at Tod Inlet did indeed get sick: everyone, he said, was coughing from the coal and cement dust. No precautions were taken officially, but the Sikhs tied extra clothes around their necks to cover their mouths and noses. It was mostly the Chinese workers who unloaded the coal. The resultant silicosis was especially fatal in combination with tuberculosis.

A May 1909 story in the Victoria Daily Times headlined “Chinese Fireman Dies Suddenly” describes the fate of fireman Joe Do Yen, who suffered a heart attack while working in the boiler room and collapsed on a pile of coal. He was found by his friends but was beyond medical help. His body was taken to Victoria, where he was to be buried in the Chinese Cemetery at Harling Point, between Gonzales Bay and McNeill Bay.

The special firebricks used to line the kilns were of different sizes, shapes and places of manufacture and were imported both from Vancouver and Scotland. They had to be replaced periodically as they became worn out or broken. Pat van Adrichem, who worked in the kilns at the Bamberton cement works, described for me the process of replacing the firebricks. The men working with the kilns watched for red areas on the outside metal of the kiln where heat was coming through, indicating faulty bricks. When such areas were spotted, workers were sent into the kiln to pull out and replace the bricks. The only bricks sometimes retained were the larger bricks at the end of the kiln. Although they waited until the kiln cooled down before entering, it was still hot enough in the kiln that the workers would get blisters on their feet, even through their boots. Workers used picks, bars and mattocks to remove the hot bricks, which were all keyed in together. As they cleared one side out, the operator would revolve the kiln slightly to allow loose bricks to fall and the men to get at another area. At Tod Inlet they loaded the loose bricks into wheelbarrows to get them out of the kiln and dumped them at the shore or used them as fill.

Firebrick made by Clayburn (a Vancouver company) discarded from the kiln, at the shore of Tod Inlet near the wharf. Glenboig and Snowball from Scotland are other brands of brick you can find there. David R. Gray photograph.

The Tod Inlet wharf with barge and tugboat unloading machinery for the cement plant, 1906–1907. Author’s collection, from BCCC photo album.

By 1905, the company was making cement piles to support the structure of the wharf where equipment and supplies were unloaded. These giant piles were pointed at one end, with a metal pile-shoe to facilitate driving them into the seabed with a piledriver. When the wharf was extended, sometime after 1907, these new, long-lasting piles were driven into the sea floor in a long L-shaped pattern.

The coal to power the cement mill was unloaded from barges and carried directly up to the coal house on a conveyor belt from the wharf. The coal house was situated directly beside the mill room on the west side.

Beyond the coal house and slightly apart from the mill were the other major company buildings—the blacksmith shop, the machine shop and the office building.

The forge and bellows in the blacksmith shop, 1965. David R. Gray photograph.

The blacksmith shop was a one-storey concrete building east of the mill house. There the blacksmith and his assistants created the ironwork needed for the plant and took care of tools, machines and even horses. Bill Ledingham was the first man in charge of the blacksmith shop, followed by Douglas J. Scafe. The equipment in the shop included a large forge and a round bellows made of wood and leather.

To the east of the main plant outbuildings were four other smaller buildings—the laboratory, the cookhouse, the larder and small storage shed—and the larger two-storey bunkhouse.

The small wood-frame chemistry laboratory stood between the plant and the cookhouse. It was in use by July 1905. The first chemist was Mr. Highberg; the second, Adolph Neu, later took up residence in Tod Inlet with his family. The chemist took samples from the kilns, slurry tanks and ball mills several times daily to ensure the quality of the cement. The large kilns had lidded holes through which samples could be taken. Because the raw limestone was of varying quality in the quarry, the finished cement also varied in quality depending on its internal chemistry. As the test results were received, adjustments could be made in the mixing process.

Adolph Neu had been the head chemist at the cement plant at Colton, California, in 1903. In May he was demonstrating the apparatus for testing the tensile strength of cement at a street fair in San Bernardino. In October he had been issued a patent for a new oil burner that produced a higher and steadier heat than those used previously. In June 1904, he left the Colton plant to accept a position with the Hudson Cement works in Hudson, New York. One wonders if perhaps Butchart, searching for an excellent chemist, had found him at a competitor’s laboratory.

Exterior of the company laboratory in the early 1900s. BC Archives A-09160.

Taking a sample of the cement. Still from the film The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement (BC Archives AAAA6718, 1963), presented with permission of the Lehigh Hanson Cement Company.

The cement testing machine. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See above.

The briquette breaking in the testing machine. Still from The Manufacture of “Elk” Portland Cement. See above.

Mary Parsell noted that “each batch of cement was always very carefully tested in order to retain the high standard required.”36 Jennie Butchart and her two teenage daughters sometimes assisted Mr. Highberg in the testing of the cement at the laboratory.

The cement was tested in two ways: the sand test and the tensile test. The sand test required that 95 per cent of the cement powder pass through a mesh with 10,000 perforations per square inch. In the tensile test, a square inch of cement had to withstand a force equal to 450 pounds.

Cement samples were moulded into briquettes shaped like a solid figure eight or a short dog bone, three inches long, one inch thick and an inch wide at the narrowest point, and were stamped with a date or number for identification. These were kept underwater for five weeks before testing. The rounded ends of the briquette were clamped to the cement tester, and a small pail on the beam end was slowly filled with lead shot until the sample broke. Tests in 1905 showed that the Tod Inlet cement could withstand a strain of 950 pounds, much higher than the industry standard. Other apparently handmade briquettes found on the shore of Tod Inlet near the plant, shaped like a cookie or sand dollar, 7.5 centimetres in diameter, with numbers inscribed by hand, were probably used for the first rounds of testing as the plant was coming into operation.

A newer cement briquette from Tod Inlet, on top of an illustration in Scientific American Supplement, 1913. David R. Gray photograph.

Broken cement test briquettes on the shore. David R. Gray photograph.

The cookhouse was where the single men who lived in the bunkhouse had their meals. Several Chinese men worked for the company as cooks, either on the company ships or in the company cookhouse. The cooks grew vegetables and raised livestock, mainly pigs. Pat van Adrichem, a former gardener at Tod Inlet, remembers seeing corrugated tin used in the village to keep the pigs enclosed, and pig skulls were certainly numerous in the old Chinese midden above Tod Creek.

When Mary Parsell first arrived at Tod Inlet, she had some difficulty getting used to the necessity of ordering food once a month to come in on the company boat. When they ran short, the “Chinese cook would sell us one loaf of bread but he never looked too pleased when we asked for it. After all, he had a large gang of men to feed and both he and his helpers worked hard.”37

The company built a large two-storey concrete bunkhouse for the single men, halfway between the plant and the village of wooden company homes where the married men lived with their families. When the men’s bunkhouse was built, it included a large room at one end that the company allowed the villagers to use for recreation, including card games and parties.

A dam was constructed on Tod Creek in 1904 or 1905 to create a reservoir from which to pipe water to the cement plant and village. The chairman of the Victoria Fish and Game Club spoke to Robert Butchart in 1905 about the dam obstructing fish from reaching Prospect Lake from Tod Inlet.38 At the time, Butchart promised to construct a fish ladder, but if it was built at all, it did not last long and it was never effective.

Once the mill began operations, large quantities of coal were burned in the boiler room, creating huge amounts of ash and cinders. The ash and cinder residue was initially used for surfacing on the roads and paths that led from the mill to Lime Kiln Road. Some was also used in the construction of the plant buildings. With his team of horses and dump cart, the company teamster, Billy Greig, the son of the former lime burner, carried the excess to the shore in front of the bunkhouse. There he dumped it over the banks of the inlet, extending both the steep banks and the shoreline below. The company horses were kept in the concrete stable that stood between the family houses and the Chinese village.

The post office for the new village of Tod Inlet was located in the two-storey company office building, just east of the cement plant. In 1904, local businessman Wilfred Butler’s offer to deliver mail to Tod Inlet was accepted by the postmaster general, and the community had received its official name. Mail service to the Tod Inlet Post Office began on May 1, 1905. Butler’s job was to collect mail at the Keating Station of the Victoria & Sidney Railway each morning (except Sunday) and deliver it to the new post office “with dispatch.” He was then required to get the return mail from Tod Inlet to the Keating Station by 5:54 p.m. to catch the Victoria-bound train.

Oil painting of horses in the company barn at Tod Inlet, 1924, by Joseph Carrier (1850–1939). Carrier family collection. David R. Gray photograph.

The cement barn in the 1960s. David R. Gray photograph.

The post office opened in the office building on the same day mail service began, with H.A. Ross, treasurer of the Vancouver Portland Cement Company, as postmaster. When the first directory entry for Tod Inlet appeared in the Vancouver Island Directory for 1909, it listed an assistant postmaster: W.E. Losee, superintendent of the cement plant.

The postal service wasn’t the only way of communicating. The city directories for Victoria from 1910 on describe the Tod Inlet connections to the telegraph system by road: “Stage connects twice daily with V. & S. Ry. at Keating which is the nearest telegraph office distant 2½ miles.”39 The first telephone in Tod Inlet was not installed until 1910.

The local maps of 1905 show Lime Kiln Road reaching the shore of Tod Inlet at the site of the new village. Maps based on topographical work done in 1909 show both the road leading to Tod Inlet and other smaller roads leading to Butchart Cove and the Fernie farm, as well as a loop through the cement plant, and a longer road across Tod Creek to the southeast. This road leading east from the Tod Inlet community and south across Tod Creek towards Durrance Lake first appears on a 1909 map, and it is also shown in 1911 and 1921. (The lake itself is man-made, designed as a source of water for the industrial works at Tod Inlet.) A house marked between the hills is probably the house known locally as the Beetlestone cabin, owned by John Beetlestone, an early farmer of the area. The 1911 census also mentions Lime Kiln Road, under the name of Cement Works Road.

Gus Sivertz, a local columnist in Victoria, described what it was like to travel to Tod Inlet down Lime Kiln Road in the early 1900s: “One reached Tod Inlet by the simple expedient of boarding the old V & S railway at Victoria, riding its dusty and swaying carriages to Keatings and transferring to a stage coach—really! It was a wonderful ride in strawberry time and if one was reasonably fast afoot he could jump down at a hill, leap a fence and snatch a handful of sun-ripe strawberries and race ahead to catch the stage before the horses started to trot down the next slope. At Tod Inlet the driver held his team hard and his foot was pressed down on the brake as the stage seemed to want to override the horses on the last steep incline.”40

The Parsell family at their old house-tent in 1906. Courtesy of Norman Parsell.

Tod Inlet quickly became a thriving community. As the plant was built and the beginning of production loomed, the arrival of new personnel and their families and the hiring of large numbers of labourers began to create a rugged pioneer community.

In May 1905 Mary Parsell and her three children took the Victoria & Sidney Railway to Keating Station, where they were met by a man driving a horse-drawn buggy. On their way to Tod Inlet they passed just four houses along Keating Cross Road. The Lime Kiln Road down to Tod Inlet ran through dense bush and then down a long, steep hill. “I felt extremely nervous as we continued going down and down. At last we reached home, a tent twelve feet by twenty feet with board floor and boarded sides two feet high.”41 Wilfred Butler II, who ran the stagecoach as a teenager as soon as he was able to handle the horses, found it a challenge holding the brakes on the long hill down to Tod Inlet.

The tent, the Parsells’ first shelter, was the former home of superintendent Losee’s family and included a leaky lean-to kitchen with a cookstove. The tent was close to the active quarry, and before each round of limestone blasting, quarry boss James Thompson or one of his men would warn Mary to take her children a safe distance away. The small pieces of flying rock that frequently hit the tent did little damage, but “one day a huge rock landed just beside our dwelling and if it had been a direct hit, there would have been plenty trouble.”42

In the fall of 1905, the Parsells were able to move into one of the newly built houses along the road leading to the Chinese quarters. Within a year there were seven more houses, all built by Thomas Tubman, a local carpenter and builder contracted by the cement company. After their tent dwelling, a newly built house in the village seemed deluxe to Mary Parsell. It was also significant to the community. In 1910, during the construction of a new cement plant on the west shore of Saanich Inlet, the manager of the British Columbia Telephone Company came to Tod Inlet looking for a suitable place for a telephone to be installed. The most suitable place turned out to be in the Parsell house.

While living in the village, Norman Parsell and his sister Ella walked to the West Saanich School in what is now Brentwood, “a long walk for six-year-olds, especially in the rain.” In those days much of their route was just bush. The distance was about three and a half kilometres, and it would have taken the children close to an hour to walk. The original school had been built in 1880 at the corner of Sluggett and West Saanich Roads. A new school, still only one room with a pot-bellied stove and outhouses, opened in 1908 and operated until 1952. There were lots of children in the village, and all went to West Saanich School.

The Parsell family moved to a second house at the top of the upper row of houses, by the gate, to get away from the aerial tram-line that often spilled limestone from the overhead buckets. They stayed there until 1912. In that year they bought six acres about a kilometre and a half up Lime Kiln Road from the village, beside the Pitzer family property, and built a new house. The Pitzers were farmers, a large and friendly family who had lived there since 1891. As Norman Parsell put it, “a nicer family would be hard to find.”

The Vancouver Island Directory for 1909 lists 31 residents of Tod Inlet. As usual, the immigrant labourers were not listed, though their presence was recognized: “nearly 200 Orientals located here.” Peter Fernie, retired, and John Beetlestone, farmer, are the only two men listed who were not associated with the cement industry. By 1910 the cement plant was described as employing 250 men, of whom only 32 were listed in the directory. The Canada census of 1911 lists 368 employees of the plant: 239 workers living in the Chinese camp, 63 in the “Hindu Camp,” 56 in the bunkhouse and 10 men as heads of families in the village.

Henderson’s 1913 directory only lists 25 men, 21 of whom were employed by the cement plant—mostly the married men of the village.

The others were Herbert Hemmings and Frederick Simpson, farmers; Hugh Lindsay, a gardener for the Butchart family; and Robert Hunter, keeper of the small store at the top end of the village.

The social life at Tod Inlet was created from within, mostly by the wives and children of the cement company employees. It was an important part of life in the isolated community, keeping morale high in families and giving a sense of community belonging.

Dances and card parties were held in the cookhouse dining room, with permission from the plant manager, William Losee. Everyone attended these events. The cook would make a large cake as a contribution. Mary Parsell remembered Billy Greig, the company teamster, taking a dozen or so residents to dances at the Saanichton Agricultural Hall in the hay wagon.

Although there has never been a church in Tod Inlet, Sunday services were held in the community for about a year and a half, beginning about 1909. The church services and Sabbath school took place in the kitchen of the Parsell home, with the Reverend Frederick Letts as minister. When the West Saanich Hall was built in 1911, the Tod Inlet residents held services there. They then moved to the new Sluggett Memorial Church the next year in what is now the village of Brentwood Bay.

The Chinese labourers lived apart from the other workers in a group of roughly built dwellings above Tod Creek. The road to the Chinese quarters passed between the rows of new houses that were constructed in 1906–1907 for the white employees and their families. The Chinese labourers mostly built their own houses. To Norman Parsell, the houses always looked makeshift, but they seemed to withstand the elements. Most of them had few windows, and they always seemed to be dark inside. There were no wives or families in that part of the village.

Four to six men lived in each house, but they ate together in one large building. Gardener Alf Shiner remembered them using a large communal pot. Dem Carrier, who grew up at the inlet, used to take fresh cod up to the village to sell. He remembers most vividly the smell of incense and the clutter in the houses; the village was “pretty ramshackle, pretty poor living structures: low, dark, dingy. Terrible place to live, really.”

The Parsell family often had Chinese friends come to their house in small groups for lessons in English. Norman remembered the names Wong, Fong, Sam and Wing among them.

Opium pipe bowls found at Tod Inlet in the 1960s. P. van Adrichem collection. David R. Gray photograph.

At Lunar New Year, the Parsells visited the men who worked for James in the furnace room and were given gifts of firecrackers, ginger and lychees—and always Chinese lilies for Mary, whose friendship they particularly appreciated. She felt a real sense of trust between them.

It is unfortunate that we have no accounts of life at Tod Inlet from the Chinese workers themselves. Those who do tell the stories of the relations among the races at Tod Inlet from a white perspective remember them as excellent, even as anti-Chinese riots were taking place nearby in Vancouver. Chinese labourers were not popular then in Canada, and in some areas of British Columbia, anti-Asian racism was rampant—and at times vicious.

Another impact of the poor working conditions, along with the laws and regulations that prevented family from joining the immigrant workers, may have been the use of alcohol and opium by the overworked and lonely men. After the Chinese village was abandoned, the area where it had stood was identifiable by the abundance of various liquor bottles: rice wine, gin, whisky and beer from around the world. Also conspicuous were the tiny, fragile glass bottles or vials known as opium bottles, and the ceramic bowls of opium pipes. Several stores in Victoria’s Chinatown were still legally selling opium in 1905: Shon Yuen & Co., at 33 “Fisguard” Street, and Tai Yeu & Co. were listed in Henderson’s Directory for Victoria as “opium dealers,” and Lee Yune & Co. as “opium manufacturers.” The use of opium was not banned until 1907. As opium poppies grow well in Victoria, it seems that some workers chose to grow their own rather than buying from the sources in Victoria.

The “Hindu Town” at Tod Inlet, showing the living conditions of the Sikhs at the plant. In other archives the photo is titled An East Indian Farm, Tod Inlet, Saanich. The two-storey Chinese bunkhouse is just visible in the background on the right. BC Archives A-09159.

When Dem and I walked through the old Tod Inlet village area in 2007, we stopped at a circular cement ring with a hole in the middle, in front of the old bunkhouse foundation. “The flagpole was in the centre here, where you see the hole in the ground. The whole garden was raised up, it was full of poppies, which we always assumed to be opium poppies…. Our parents told us to stay away, don’t handle them, but of course we did. We used to take the heads off, get the milky substance all over our hands…. I’m sure they were opium poppies, and obviously grown by Chinese people.”

Max Pallan also remembered stories about the use of opium from his dad, Gurditta Mal Pallan. “The Chinese loved opium. It helped them work, gives them stamina and strength. My dad tried it too, but then he got sick. He threw the tin away: ‘I’m not going to use it.’”

The Sikhs at Tod Inlet had a separate kitchen and bunkhouse from the Chinese workers. In 1907 the Sikh bunkhouse was described as “a small one-storey bunk house, some seventy feet by forty.”43

Jeet Dheensaw, son of Hardit Singh, who arrived in 1906, remembered his mother’s stories of the Sikhs living in shacks with dirt floors, using cardboard for insulation and flour sacks as blankets. Material possessions were virtually non-existent. There were few houses, and the men slept four or five in one room. She said the men had no raincoats at first, and they got used to working in the rain, as they did not want to spend their wages on new clothing. They preferred to use “old stuff” left behind by others over spending money on new things.

Jeet remembers, “My dad and my uncle, that group of people, used to just have shacks there, working and staying in shacks, making their own food and living on dirt floors. In winter it got bitter, so they used to put planks down, but that’s all. They survived. When something fell down, they just added up another board or something and stuffed newspapers, whatever they could get their hands on, if nothing else mud even, just to keep the elements away. There was nothing, no beds, no tables and chairs.”

The Sikh brick ovens at Tod Inlet in 1968 (left) and 1979 (right). Alex D. Gray (left) and David R. Gray (right) photographs.

One man was assigned to do the communal cooking for the Sikh community, and each worker gave one day’s wages to the cook each month. One of the men who prepared the food in exchange for money was named Katar. Katar Singh was a blood relative of Hardit and Gurdit Singh, known as “Uncle” to Jeet Dheensaw and remembered as very strong. The Sikhs at Tod Inlet apparently followed the tradition of using two cooking fires side by side: one for cooking lentils and vegetables, the other for cooking chapati (flatbread) on a steel plate griddle. Norman Parsell and the other young boys living at Tod Inlet often watched the Sikhs cooking their chapati on an iron plate over an outdoor fire and were often invited to join the meal.

Lorna Pugh (née Thomson) told me a story of her father, Lorne Thomson, and Claude Butler Sr., hunting up in the Partridge Hills above the inlet in about 1910 and being caught by the darkness. They decided to stay the night up there rather than run the risk of going over one of the cliffs in the dark. When they came down at dawn the next day, they came out of the woods opposite the Sikh village: “After crossing Tod Creek they approached the Hindu campsite, where the Hindu employees of the cement company lived. The cook offered them tea, for which they were very grateful. The water was heated in a large brick trough, and the cook dipped his finger … into the trough to test the temperature of the water before giving them their tea…. It was hot and helped them to continue on their way home.”

There are remnants of two brick structures near the trail that branches off from the main trail in what was the Chinese village. These are typical of Indian cooking ovens and are the only physical evidence of the Sikh community that remains there today.

Amrik Singh Dhillon of Victoria heard stories from his father, Bachan Singh, about the details of the life of his friends, Gurdit and Hardit Singh (Jeet Dheensaw’s father), both workers at Tod Inlet. They ate mostly beans, dal or roti, though they also made pancakes, and drank tea. They used lids from food cans as cups, and made serving utensils from a can on a stick. At that time, a 50-pound sack of flour cost one dollar, butter was 25 cents a pound, and beans 5 cents a pound. The men chewed the ends of willow tree branches to make improvised brushes for cleaning their teeth.

Gurditta Mal Pallan told his son Max how the Sikhs at Tod Inlet walked six kilometres up to the Prospect Lake Store to buy groceries. Two men would go every two weeks or so by turn. He said they carried the food, clothes, socks and dollar bottles of whisky back in a kind of tub on their heads. They also walked to the nearby farm to buy chickens and eggs. The Sikhs carried water from the creek in two large buckets, each at the end of a pole carried over the shoulder. Baths were taken only once a week. A committee arranged the finances for purchase of food and supplies and computed each man’s share at the end of the month. In general, anyone visiting from India and hoping for a job was fed free for a month. For newcomers, after the first month, expenses were paid by a sponsor until they got a job.

Max Pallan also recalled his father’s memories of their day of rest from the early days of the cement works in 1906: “Every Sunday, just about every Sunday, Mrs. Butchart, she used to have a, just like open house, all the workers from the cement mill, and she used to serve tea. They made a special trip to go to the Butcharts’ residence and look around in her garden, which was very small at that time … but still Mrs. Butchart came out herself and greeted everybody and said ‘Hello,’ and served tea there in the garden. My dad and other friends who came from India were very excited that a rich lady like that was giving that much time to the workers and to the foreigners.”

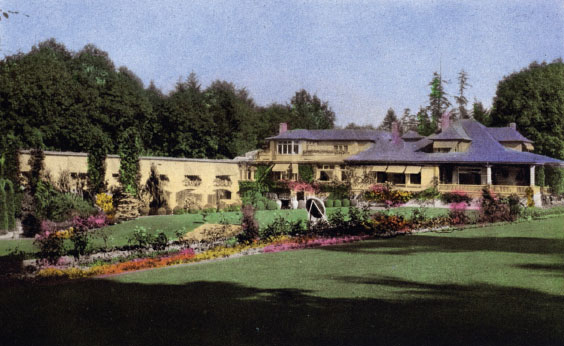

The Butchart residence and surrounding garden, 1930s. Postcard in author’s collection.

In 1907 there was a very serious outbreak of typhoid fever at Tod Inlet. Tod Creek, which provided the community’s drinking water, flowed through miles of open ditch on its way from Prospect Lake, and during the summer became seriously polluted. The company soon switched to drawing drinking water from a spring located just east of the houses at Tod Inlet. Water from the creek was still used for the cement plant and for irrigation, and the use was heavy enough that no surplus came over the dam at what is now Wallace Drive.

For its first few years of operation, the Tod Inlet plant steadily increased production of cement, and its capacity rapidly doubled.