THE SHAKING CAME IN VIOLENT BURSTS, STRONGER THAN ANYONE had felt before. Periods of slow regular oscillation followed by sharp grinding vibrations. Buildings were cracking open, and tools hurtled to the floor in the fishermen’s sheds by the wharf. To stay standing, you had to hold on to a wall or doorway. Dust rose from little landslides along the cliffs. It was 2:48 p.m. on a cloudy Friday afternoon in March. The shaking, which lasted six grueling minutes, felt as if it would never end.1

As the violent tremors faded away the tsunami sirens sounded their mournful cries, whooping from low to high. People already outside started to clamber up the cliff-side staircases from the port. In the lower town, seniors glanced out of their windows at the ugly concrete tsunami walls that separated them from the sea and hunkered down. Five years before, the sirens had sounded but no waves had arrived. This was probably another false alarm. It was a cold afternoon, with snow flurries, and venturing outside, standing around, had no appeal.

Among those who climbed up above the lower town, all eyes were on the sea, on the water in the harbor, and on the distant horizon seen between the headlands. As the minutes passed and nothing happened, they began to relax.

Kamaishi is a former steel town, situated in a drowned valley inlet on the remote mountainous coast of northeast Japan. In the 1970s, 12,000 people were employed in the steelworks and the town’s population was close to 100,000. The mill closed in 1988, and now the population was down to 40,000. The economy depended on fishing. In 2009 the government spent $1.5 billion on a 1.25-mile (2-kilometer) breakwater, rising up from the seafloor 200 feet (60 meters) below. Said to be the deepest and most expensive in the world, the breakwater was intended to revive the town by providing shelter from the Pacific swell for moored container ships. Yet no ships had come to call.

Kamaishi was known for having a “tsunami problem.” In 1896 the town had been wiped off the map in a deadly and unforeseen nighttime tsunami. The triggering earthquake, 180 miles offshore, was felt by ships out at sea but scarcely noticed on land. Two-thirds of the town’s population of 6,500 died when 1,800 houses and warehouses were washed away. The memory of that calamity preserved the lives of the survivors thirty-seven years later, on March 3, 1933, when they felt a strong nighttime earthquake and fled inland in their nightclothes. Even though the tsunami destroyed more than 7,000 homes and in some places lapped as high as 70 feet (20 meters), this time only 164 were killed out of a population of almost 32,000.

Now, in 2011, the older residents remembered the stories told by their parents of hiding on the edge of the forest in the night and hearing the tsunami demolish the town.

![]()

AS SOON AS THE SHAKING CALMED, THE TEACHING STAFF AT KAMAISHI East Junior High School attempted to muster their students into the school yard. They tried to take a roll call, but the electricity was out and the microphone didn’t work.2 Meanwhile, some students had already started running out of the school gate and uphill toward the preplanned evacuation site almost half a mile away (700 meters). Among them was fourteen-year-old Aki Kawasaki. He had just started baseball practice and was terrified that a tsunami was coming. Many others, however, like his classmate Kana Sasaki, only ran because everyone around them was running.

Japan prefectures and cities impacted by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami

At the neighboring Unosumai Elementary School, the teachers had begun evacuating children to the third floor of the school building. Seeing the junior high school students running, they changed the plan and sent the children to run alongside their older brothers and sisters.

When the children reached the evacuation site, an elderly woman told them that she feared the worst, that the earthquake was stronger than anything she had experienced. So they kept running to even higher ground, the older children holding the hands of the frightened younger ones.

Twenty minutes after the shaking ended, the watchers on the cliffs saw a dark line on the horizon that soon became whitened with surf. Where the breaking line of surf met the great breakwater at the steep-sided entrance to the open sea, furious currents could be seen raging between the concrete walls. Then the white water was bursting over the crest of the breakwater itself.3

The first water to arrive in the harbor boiled up over the quays, floating off some parked cars. Water in the streets moved sluggishly, but as the level rose it flowed like a fast river. The wooden two-story buildings, lifted off their foundations even when the water was little more than one or two meters deep, turned into battering rams that demolished warehouses and other buildings, which collapsed in on themselves in great clouds of dust and plaster. The clock on the gable of the Unosumai village hall stopped when it was immersed at 3:25 p.m.

The children turned and looked back at their schools. The tsunami was surging through the buildings, smashing houses and cars, and rising so high as to overwhelm the third floor of the elementary school; eventually it deposited a car on the roof. If they had waited another ten minutes, they would have drowned.

Weeks later, after the bodies had been pulled out of the piles of debris, after the unaccounted for were listed as “missing,” the tally for Kamaishi was 1,200 fatalities, or one person in thirty. Many of the victims were older people who had lived in the low-lying port area.4

Remarkably, however, every single student who was in school that day survived: all of the 212 junior high and 350 elementary school students. In other nearby coastal towns, there had been tragedies. In eleven out of the twenty-one schools inundated by the tsunami, the children had stayed in the building.5 At the Okawa primary school, 74 out of 108 children died.

The headlines proclaimed “The Miracle of Kamaishi.”6 Yet the story at Kamaishi was no miracle. Its children survived because of one maverick Japanese professor who had set out to teach them a completely different narrative about disasters and survival.7

![]()

WHO AT THE START OF THE NEW MILLENNIUM KNEW WHAT TO DO in a tsunami? The Boxing Day Indian Ocean earthquake on December 26, 2004, changed everything. This was the first oceanwide tsunami in forty years. In resorts along the west coast of Thailand, the tsunami surged into the beachside hotels midmorning. Tourists pointed their cameras and captured the first-ever movies of a great tsunami. One sequence shot from a headland shows the water draining out of a wide bay before a great wave rolled back in, overwhelming a man who had gone down to collect stranded fish and now stood spellbound as the gray-brown water surged over the beach.

Another movie captures the water flooding over the swimming pool and into the ground-floor patio of a hotel, rising slowly at first and then much faster. Guests are caught trying to hold on to railings as the water seethes around them, but the camera moves away before we see who managed to escape.

In Banda Aceh in northern Sumatra, a video cameraman was filming a wedding party on a second-floor rooftop balcony in the heart of the city. The scene starts with a call to watch a trickle of water arriving along the neighboring street. As the water grew deeper the current accelerated, filling with floating cars, until the tsunami came close to overwhelming the cameraman.

A tsunami has many different guises: sometimes a great wave breaks, but more often the water rises and rises, more and more alarmingly, for five to ten minutes. The original English term “tidal wave”—half tide, half wave in character—failed to evoke this monstrous terror; thus, in 1896, a more compelling word was borrowed from the Japanese: “tsunami,” or “the wave in a small village harbor,” is the local name for the kind of sudden rise in the sea that destroyed Kamaishi.

After the visceral experience of watching these movies, you can never again walk along a sandy shoreline without experiencing some subliminal mistrust of the ocean. On a malevolent whim, it seems, the benign waves can rise up and pounce far inland, dragging their spoils out to sea.

Tilly Smith, a ten-year-old English girl, was on holiday with her family in a beachfront hotel in Thailand. She had been taught about tsunamis by her geography teacher at Dane’s Hill School in Surrey only three weeks before.8 She had learned that when the sea mysteriously drains away far below low tide and the water streaks with rising bubbles, a tsunami is coming. Seeing the water slowly recede, and not waiting to ask an adult, Tilly took it upon herself to scream at all those around her to move to higher ground. Almost 100 people on that stretch of Mai Khao Beach followed her lead, and as a result, it was one of the few beaches on the island where no one drowned.

Toshitaka Katada, a professor of civil engineering at Gunma University in central Japan, visited the tsunami-ravaged coastlines of Thailand and Sumatra and considered the lessons to take back to Japan.9 On Sumatra he saw how tens of thousands had felt the strong earthquake shaking but had not thought to evacuate in the twenty to thirty minutes before the tsunami arrived. He saw the consequences of passivity. Everyone had waited for official instruction, but no order came. He marveled at the story of Tilly Smith. Children, he observed, can possess a fearless authority.

On Katada’s return to Japan, he was shocked to discover how little people worried about tsunamis. Even in the coastal towns along the Sanriku coast—the birthplace of the term “tsunami”—memories of the last great disaster, seventy years before, had faded. Through the 1980s, the government had constructed concrete tsunami walls to protect the low-lying ports, but as a result many coastal towns had given up their annual tsunami evacuation drills.

When Katada visited the schools in Kamaishi to talk to the children, he found that they had total confidence in the walls. Their sense of obedience was strong. If the adults did not run to higher ground, the children would not think of doing so themselves.

A story about a tsunami known to all children in Japan highlights this desire for official instruction.10 The story tells of how the wise village headman saved all the lives in his coastal village after a tsunami in late December 1854.

Hamaguchi Gohei lived up the hill from the bayside houses in the exposed Wakayama Prefecture town of Hirogawa, on the Kii Peninsula of southern Honshu. Late in the afternoon one day close to the end of 1854, he felt a long-lasting vibration. Within a few minutes, the sea began to recede, while on the distant horizon he saw a dark line growing thicker as it approached. Recalling a story told by his grandfather, he realized that a tsunami was on its way. How could he get the villagers below to evacuate inland? Running inside to bring out a burning log from his winter hearth, he turned the year’s precious harvest of rice stalks into a crackling, smoky bonfire. Seeing the wanton destruction, and believing that their feudal lord had gone mad, the villagers all rushed up the hill, then turned to watch the tsunami destroy their houses down below. It took another tsunami in 1933 for the Japanese to accept their tsunami affliction, after which the story was mainstreamed into the culture in the national schoolbook for fifth-graders.

Motivated by the story of Tilly Smith, Katada explored how to inspire children to take action in a future disaster and came up with “Tsunami Tendenko”—a policy that cut hard against the grain of conservative, “follow the instructions” Japanese culture.

Katada chose to focus on the frontline city of Kamaishi. Initially, the local teachers claimed that there was no time in the curriculum for disaster education. Then, in 2006, a tsunami scare followed a great earthquake off the Kuril Islands to the north. Fewer than one in ten of the children in the low-lying schools most at risk from tsunamis were evacuated. Each of the fourteen schools in Kamaishi subsequently agreed to Katada’s request to allocate ten hours a year to disaster education.

In March 2010, working with the teachers, Katada produced a manual in which he emphasized his three principles:

Don’t believe in preconceived ideas.

Do everything you can.

Take the lead in evacuation.11

Katada recognized that, when dazed and confused, people search for instruction:

Even though you know you should escape, you convince yourself that you are safe. When the alarm bell sounds you don’t want to believe that there is a fire. . . . You often need a second piece of information to make you flee—a smell of smoke—someone shouting “fire.” After an earthquake everyone looks around to see if their neighbors are responding. They feel reassured if their neighbor has not run. A temporary network of security is established—people convince themselves they have made the right decision. And then the tsunami attacks and everyone dies.

What Katada had seen in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami had taught him to distrust official hazard maps, “because no one can predict nature’s power.” He encouraged the children to trust in their instincts: “It takes a lot of courage to be the first person to run out of the room when the alarm bell sounds,” he wrote. “You have to be the first to run. And others around you will be inspired and will also make their escape . . . and you will save many people.” The children could not have known then how soon they would be called upon to turn these principles into action.

On the afternoon of March 11, 2011, Katada was in Hachinohe, a town near Kamaishi, to deliver a talk. When he was rocked by five minutes of intense shaking, he knew that this was a giant earthquake out in the ocean on the subduction zone and that a tsunami would inevitably follow. He was consumed with worry about all the children he had taught. Would they evacuate high enough? The live TV coverage from Kamaishi showed horrific scenes. When he heard the news later that all those who had been at school had survived, he was filled with emotion: “From the bottom of my heart I wanted to thank them.”12 Yet not everyone had heard his message. Some parents lost their lives waiting for their children to return home.

Those who chose to drive toward higher ground initially overtook those on foot, but then got blocked by congestion.13 In some towns the tsunami arrived before drivers could escape onto the embanked highway. (After an earthquake in Samoa only eighteen months before, for fear of the expected tsunami, everyone got into their cars. As a result, the principal coast road became blocked, and almost 200 people were drowned, many of them washed out to sea in their vehicles. To escape people only needed to walk to higher ground.14)

After the 2011 tsunami, the Ministry of Education authorized the return to school textbooks of the story of the village headman setting fire to the rice stalks. Yet there was some ambivalence about promoting Katada’s real-life lesson on the merits of civil disobedience.

![]()

WHETHER TO TRUST THE FLOOD WALLS OR EVACUATE WHILE THERE is still time—what information do people need so that they can take the right action? Is it education or concrete defenses that provides the greatest protection? We come to another extraordinary disaster of the new millennium: Hurricane Katrina and its storm surge.

In a storm surge the flood is driven by fierce winds blowing toward the coast. The stronger and more persistent the winds the higher the surge, which can last for hours—the time it takes a big windstorm or hurricane to pass. The wind-whipped waves of a storm surge ride inland, smashing everything fragile in their path; a tsunami, which drains faster and takes most of its debris out to sea, is said to be “tidier.”

Confined by the coast, the winds bulldoze a mound of water ahead of the storm, but if the water is deep or the storm front is narrow, the mound drains away, under or around the storm. Off the coast of Mississippi, you can wade out to sea for miles because the North American continent’s greatest river has filled the sea with sediment. And that is where the biggest of all Atlantic storm surges roll inland.

There is only one flood-walled city along the US coast, and that is New Orleans. Without its levees, the surf would break on Bourbon Street every day. Apart from the original city (the French Quarter) built on the natural river levee, the average elevation in New Orleans is six feet below sea level. The city was founded by the French in the eighteenth century, a palisade on the first dry land up the Mississippi River. Fur trappers could tramp through the bayou swamp between the river and sea-level Lake Pontchartrain a few miles to the north. From the late nineteenth century, as the city expanded, the swamps were pumped dry and the land sank like a desiccated sponge.15

By the start of the new millennium, Kamaishi had been flooded by tsunamis twice in little more than a century, while New Orleans was already on its third storm surge inundation since 1900. Yet residents of the Big Easy preferred not to dwell on the city’s watery history.

The first lesson from New Orleans is that flood defenses follow big floods. The damage demands some action. Wait too long, however, and politicians find something else to do with the money. New flood defenses need to be built high enough to withstand the latest floods, and then a little bit higher, depending on how much money can be found.

The second lesson for a sinking city is that, as sure as night follows day, big floods will eventually follow the flood defenses. And because the city is sinking, the next flood tends to be even deeper than the last.16

In 1915 a hurricane passed over New Orleans, driving a 6-foot surge in Lake Pontchartrain. Water flowed into the city, reaching 8 feet (2.5 meters) deep in some downtown areas. The city invested in some bigger pumps, built walls by the sides of the drainage canals, and created an embankment along the lake shoreline.

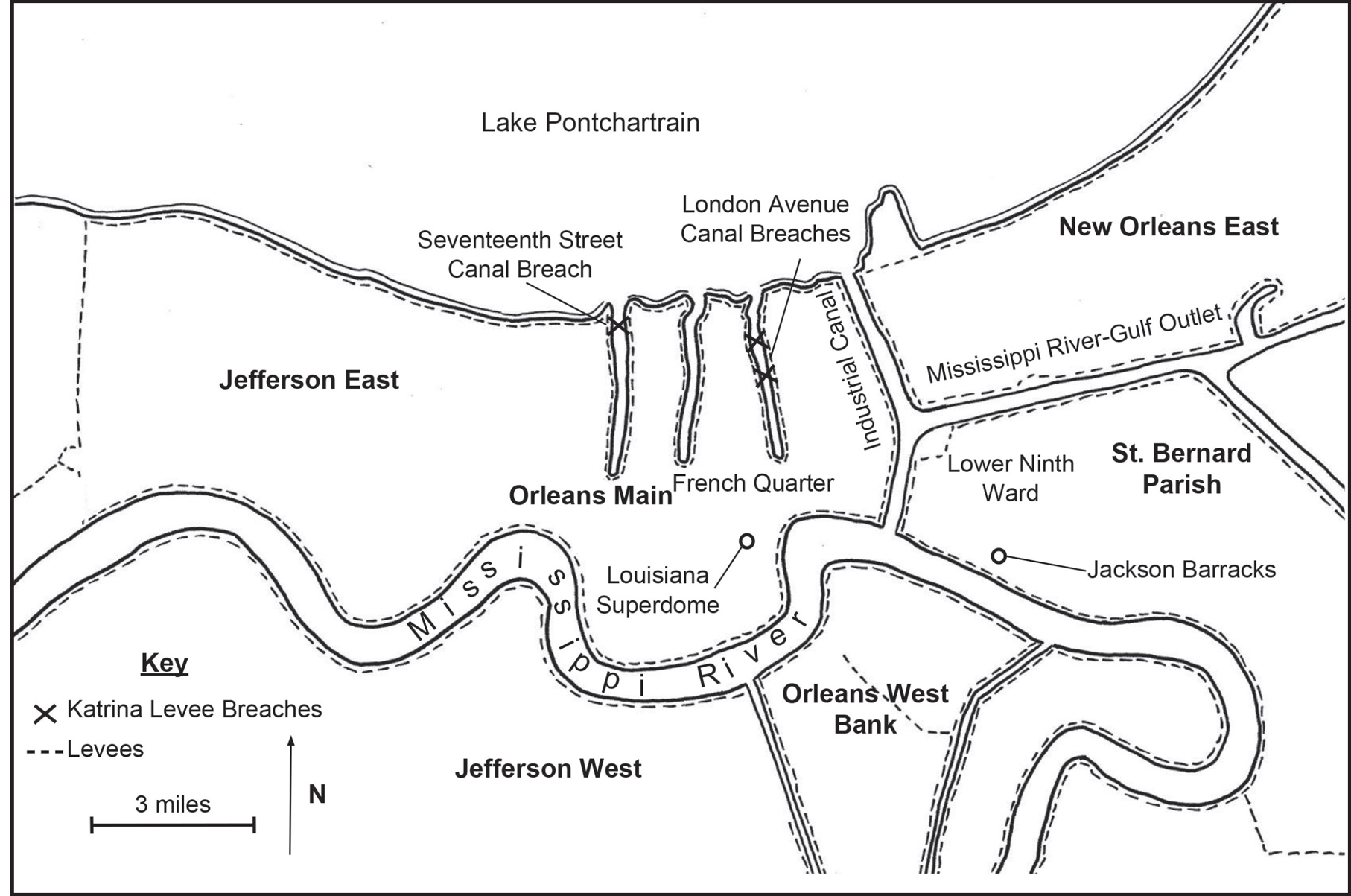

In 1947 a hurricane passed right over the city, breaching the embankment along Lake Pontchartrain.17 When the western wall of the Seventeenth Street drainage canal collapsed, thirty square miles of land in neighboring Jefferson Parish were inundated. Fifteen thousand people were evacuated. Holes had to be dug and blasted in the defenses to let the water escape back to the sea. The flood defenses were then raised, and land was reclaimed from the lake, inspiring a postwar boom in house building to the northeast of the city.

By the early 1960s, the city’s population was 625,000. In 1965, in a fit of grandiose geo-engineering, the US Army Corps of Engineers dug a shipping channel, linked with the Industrial Canal, to approach New Orleans from the open sea to the east.18 The channel, known as the Mississippi River and Gulf Outlet (MRGO, or “Mr. Go”), was cut 36 feet (11 meters) deep and 650 feet (200 meters) wide.

New Orleans canals and levees

Within months of the opening of the new channel, Hurricane Betsy, a Category 3 storm, came in from the Gulf of Mexico.19 The strong easterly winds ahead of the storm funneled a 12-foot (3.6-meter) mound of water straight up the newly constructed Mr. Go shipping channel to spill over the low embankments of the Industrial Canal and flood the whole eastern part of the city. Thirteen thousand houses were immersed in water up to nine feet deep, more than 60,000 people were made homeless, and 58 died. The defenses along Lake Pontchartrain held, so if not for the Corps of Engineers’ gift of the “Mr. Go” shipping channel, the city would have stayed dry. Betsy was the first US disaster to cost more than $1 billion.

Following Betsy and years of “white flight,” New Orleans never recovered its early 1960s population. The middle classes, unable to sell their properties in the lowest-lying parts of the city, left them to be rented to the poor.

In the same year as Betsy the US Congress passed the ambitious Flood Control Act, designed to flood-proof New Orleans and prevent a repeat of the flood disaster.20 Yet the money and the will behind the plan began to drain away as the memory of Betsy faded. In 1977 a federal court barred the construction of a proposed Lake Pontchartrain dam, on environmental grounds. With a reduced budget and diminished ambition, the Corps of Engineers began a long slow program to improve the defenses. Faced with homeowners unwilling to sacrifice any part of their waterside plots, the Corps had to construct very thin concrete flood walls along the drainage canals. In 2004 the city ran a “fire drill” for a direct hit from Category 5 “Hurricane Pam” with water up to 25 feet (7.5 meters) above sea level.21 According to the simulation, one-quarter of those who remained in the city would die.

![]()

ONLY A YEAR LATER, THE KATRINA TRACK FORECASTS WOULD PROVE remarkably consistent and accurate: the actual track was only 15 miles (24 kilometers) east of the track forecasted fifty-six hours earlier. On Sunday, August 28, 2005, the day before landfall, when the storm was at maximum Category 5 intensity, the National Weather Service (NWS) stated apocalyptically: “Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks . . . perhaps longer . . . human suffering incredible by modern standards.” The NWS office in New Orleans predicted the “partial destruction of half of the well-constructed houses in the city.”22

That would be warning enough, you might think, to get people to flee inland. Indeed, more than 90 percent of the city’s population had left following Mayor Ray Nagin’s mandatory evacuation order on August 28, when he warned that “the storm surge most likely will topple our levee system.” Yet tens of thousands either chose not to leave or had missed the available transportation options. Some wanted to protect their property from looters. Some had been discouraged by the evacuation terms, which forbade pets on the buses. Some who dismissed the order were remembering the false alarm evacuation for Hurricane Ivan the previous year. And many stayed through inertia, not really believing their lives were at risk, trusting in the flood walls.

As is often the case, the wind forecasts had indeed been hyped. Like a pirouetting dancer stretching out her arms, the original Category 5 storm had both grown in size and weakened. In the middle of the morning of Monday, August 29, the weaker western sectors of Hurricane Katrina passed over the city of New Orleans. As the wind died down, reporters came out of their hotels and walked the streets, filming images of twisted roof metal and shifted tiles in the older buildings of the city’s French Quarter. The story in the main news feeds was that the city had once again “dodged a bullet,” escaping both major wind damage and the long-feared citywide flooding.23

Officials from the Orleans Levee District were responsible for monitoring the flood defenses. As the weather conditions deteriorated, the inspectors were withdrawn to hurricane shelters. The telephone system was almost completely dead, the mobile transmitters having been disrupted by power outages.

Ahead of the storm, the circulating winds had blown from the east, exactly as in Hurricane Betsy, pushing the storm surge straight up the Mr. Go channel. On the south side of the channel to the east of New Orleans, between 4:00 and 6:00 a.m. on the morning of August 29, 2005, the 18-foot (5.5-meter) surge overwhelmed the piled defenses and poured into impoverished St. Bernard Parish.24 Many houses were lifted off their foundations. At the Murphy Oil Corporation refinery, a massive, partly filled oil tank floated, broke, and spilled its contents over the town. The surge was still 16.5 feet high where it came into the Industrial Canal in eastern New Orleans. The first breaching occurred at 4:45 a.m.: the water spread over the 14-foot defenses into the lowland to the north of the city’s French Quarter as well as into the Lower Ninth Ward to the east of the canal. These were the areas flooded during Betsy—but now the water was three to four feet deeper.

The district commander of the Army Corps of Engineers, which was ultimately responsible for the defenses, ventured out at 3:00 p.m., but finding his path blocked by strong winds and debris, he returned to his bunker. He had encountered enough water to know that some key defenses must have failed.

The surge had not completed its mischief. The second phase of the flooding came from the north—from Lake Pontchartrain, as in the floods of 1915 and 1947. The three drainage canals, originally dug to allow water to be pumped out of the city, now turned the city into a lake. The flood walls along the canals were a minimum of 12.5 feet (3.8 meters) above sea level, and the surge coming in from the lake only reached 11 feet, so the concrete walls should have held; at around 9:00 a.m., however, the first thin concrete panels fell over.25 Once one panel had gone, the water surged through with such force that it tore out the neighboring panels, eroding chasms tens of feet deep.

The drainage canals passed through the lowest areas of the city—land that lies several feet below sea level—so water continued to flow into the city long after the hurricane had disappeared over the horizon. The operators of the city’s pumps had been evacuated for fear of the strongest hurricane winds. No one had considered how critical the pumps would be in the midst of an intense hurricane. In a circular irony, later that afternoon the pump house operators were unable to return to their pumps because the city had flooded.

The first that the New Orleans Police Department heard of their city’s inundation was late on Monday evening, when off-duty police officers called in from their flooded homes. That evening a private helicopter flew over the city and fed images to a local TV station. Only at 9:00 the following morning was the local commander of the Corps of Engineers able to get into his own helicopter to see that 90 percent of the city was underwater.

It had taken more than twelve hours for people to realize that New Orleans was flooded, and a whole day before the city could be inspected and mapped by emergency officials. One in six New Orleans police officers abandoned their post. Untold numbers of people died because of the delays in initiating rescue.

With water depths reaching 10 to 15 feet, twenty times more people died in Katrina than in Betsy in 1965. This was a disaster that had been well forecasted, a catastrophe of a kind that people believed was no longer possible in a developed country. The majority of the 1,464 Katrina fatalities listed for Louisiana were drowned in New Orleans. Of those who died, 56 percent were black and 64 percent were over sixty-five. (In the Japanese tsunami, 65 percent of those who died were over sixty.) Those who stayed in their single-story houses first had to climb into the attic space and then attempt to break through to the roof in the hope that they would be rescued. In some areas, however, even roofs became submerged. Almost two-thirds of the 147,000 properties in the city were flooded by more than four feet of water. When a large hospital complex was left without power after the ground-floor generators became submerged, doctors were forced during the chaos of helicopter evacuations to make decisions about who would live and who would die.26

![]()

HURRICANE KATRINA WAS A HUGE HURRICANE. WITH ITS NORTHERLY track passing to the east of New Orleans, the city missed the worst of the storm surge, which tore into the Mississippi coastal towns of Biloxi, Gulfport, Pass Christian, and Bay St. Louis. The land rises gently from the beachfront in those towns, with their streets of grand Southern houses nestled among oak shade trees. This coast took the full force of the hurricane winds. Like the citizens close to the port at Kamaishi, Mississippi Gulf coast residents made a calculation about their own safety. Over the previous fifty years, the worst storm to hit this coast had been the notorious Hurricane Camille in 1969. That storm had been at maximum intensity, Category 5, at landfall and driven a terrible 21-foot surge that scoured houses off their foundations for the first three blocks inland. Katrina had reduced to Category 3 intensity, so anyone whose house had survived Camille assumed that they would be safe to stay indoors for the duration of the storm. They knew that because the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale told them so. They created in their minds an invisible wall beyond which the storm surge would not advance.

The Saffir-Simpson scale was designed two years after Camille to trigger evacuations ahead of deadly storm surges.27 The five-level scale tied together the central pressure of the storm, the speed of the accompanying winds, and the height to which the sea would rise: thus, according to the scale, a Category 3 storm with a 950-millibar central pressure and 120-mile-per-hour wind speeds would drive a 12-foot surge flood. The scale had become the standard currency of the hurricane season, but the link with water height was dangerously oversimplified.

Hurricane Katrina was a much larger storm than Camille. Even after becoming less intense, the storm was still pushing a Category 5 storm surge—a huge mound of water. The waves reached five feet higher than Camille all along the Mississippi coast, sweeping away all the houses four or five blocks in from the coast and killing 200 people who had thought they could sit out the storm. “Camille,” it was said, “killed more people in 2005 than it did in 1969.”28 The linked surge and wind Saffir-Simpson scale was officially retired in 2009.

The hundreds of home movies shot on December 26, 2004, and March 11, 2011, have dramatically expanded our understanding of tsunamis. However, a big storm surge arrives with the fiercest hurricane winds, blowing 120 miles per hour or higher, making it impossible to hold a camera steady, let alone stand. So the most savage storm surges have only been filmed through smeared windows streaming with rain.

In 2013, when Supertyphoon Haiyan was bearing down on the city of Tacloban in the Philippines, as civil defense personnel were attempting to get the low-lying residents to evacuate, the common response was, “Why should we be frightened of a storm surge?” People stayed to look after their homes, believing themselves protected by the invisible wall.

The surge rose to 20 feet (6 meters) in the city, even flooding the cyclone shelters. After the storm had passed and civil defense personnel were collecting the bodies of the 6,000 people who had drowned, the survivors asked: “Why didn’t you call the surge a ‘tsunami’? Then we would have evacuated.”29

![]()

ANYONE WHO STUDIES DISASTERS WILL REMIND YOU THAT, WHILE the agents of destruction—the tsunami or the storm surge—are natural, the outcomes are all too human and “unnatural.” Disasters are determined by what we build, where we choose to live, how we prepare, and how we communicate warnings. Before 2005, there was no maverick educator like Katada in New Orleans or Gulfport, Mississippi, to teach people to distrust official hazard information and to escape on their own initiative.

The flood wall is the simplest of all catastrophe remedies. It also exemplifies the challenges in searching for a cure. The remedy works only as long as the water level does not rise too high. Once overtopped, or breached, all those people who believe themselves and their property to be protected are in jeopardy. We call this the “cliff-edge effect.” Take one step further and you will fall off the cliff. Should the water rise another foot, the whole town goes underwater.

How high shall we build the flood wall? The construction engineers tell us that every extra unit of height means multiples of additional costs—the structure will need to be broader, the foundations deeper. Raising the wall has to be justified by economics. Imagine that the flood wall does not exist—what would be the costs of the flood damage? Yet the flood wall and what it protects are not independent of each other. Flood protection acts as a honeypot for developers. You only have to look at the growth of New Orleans through the 1970s and 1980s as thousands of homes came to shelter behind the walls. While the wall protects against ordinary floods, when one day an extreme water level overwhelms the defenses, the consequences are much more catastrophic than if the wall had never been built.

There is a broad spectrum of potential floods to be considered, from the high water levels that arise every year or two to the catastrophic extremes that happen once every century. For these extreme events, inevitably we will not have perfect information. The flood wall cannot protect against every eventuality. And then if we build a wall, the displaced water may flood some other worse-protected downstream town. Should we add that cost to our equation?

The benefits are all in the future. How do we scale their value in terms of today’s money? What is the time frame over which we are looking to earn back our original investment? Thirty years? Fifty years? What discount rate shall we use for future costs? It makes a big difference in how we calculate the benefits of flood protection.

Imagine a giant set of antique weighing scales. In one pan we put all the costs of building the flood wall. In the other pan go all the savings of the floods that will not happen. We need to adjust the scales for the number of years of the comparison, move the weights in and out, and raise and lower the flood walls until the scales are balancing at our target—the maximum benefit for the least cost. For example, we may want the benefits of flood losses saved to be three times the costs of building the flood walls. Then we can determine how high to make the flood walls.

Fifty years ago, when flood walls were being designed for New Orleans and Kamaishi, it was beyond the state of knowledge—and computing power—to evaluate the full spectrum of possible floods. Both projects instead focused on a single “design flood.” For Kamaishi, it was the tsunami from an offshore earthquake that was considered credible.30 For New Orleans, it was the storm surge from the Standard Project Hurricane (SPH), an idealized fast-moving Category 3 storm.31 The description of the Standard Project Hurricane was vague and arbitrary: “the most severe storm that is considered reasonably characteristic of a region.” In 1969 Hurricane Camille was a Category 5 storm at landfall just to the east of New Orleans, but it was conveniently ignored—dismissed as “too far outside the norm.”

No one asked too many questions about where these scenarios came from or how they could be improved. Once you had the scenario, all the engineering questions suddenly became a lot easier. You built the wall to protect against that particular flood.

New Orleans is surrounded by flood walls. Before 2005, there had never been a risk assessment to identify the weakest links. After Katrina, puzzled as to why the walls had been built so low, surveyors discovered that the benchmarks used to level the city’s flood defenses had themselves sunk 16 inches (400 millimeters) unnoticed.32 The whole southern Louisiana delta region, it turns out, including New Orleans, is slumping steadily into the deep waters of the Gulf.33

Compare the attention given to flood protection in New Orleans before and after Katrina!34 The irony of a catastrophe is that the funds to prevent it only become available after it has happened. The horse has to bolt for the stable door to be closed. After the flood, the Corps of Engineers was invited to develop a plan to protect the city and had no problem in obtaining $14.45 billion (more than the cost of all the Katrina flood damage in the city) to raise the level of protection enough to ensure that the annual chances of a flood would be below one in 100.35 And the much-cursed Mr. Go shipping canal was finally dammed with thousands of tons of rock and ship gates, so that it could never again direct the flood into the heart of the city. The Corps of Engineers built flood walls to withstand another storm like Katrina. However, in a direct hit from a Category 5 storm—considered the “500 year event”—the surge flood could be another 6 to 10 feet (1.8 to 3 meters) higher. The Corps claimed it would cost at least $70 billion to protect against that eventuality—five times what Congress had authorized.36 Even in the national political crisis that followed Katrina, the check was not completely blank.

In Kamaishi, the national government announced that it would spend $650 million to rebuild the broken breakwater in the harbor. Not to repair it would have implied that the original decision was wrong, and that is not the Japanese way.37 The government also announced that it would spend one trillion yen (almost $10 billion) on more tsunami walls in the three prefectures that were the worst hit in 2011.38 At Koizumi, south of Kamaishi, a $14.7 million wall is planned, even though the village has now been relocated three kilometers inland. Not prepared to give up fighting disasters with concrete, the government remains committed to extending the ugly coastal “Great Wall of Japan.”

Kamaishi and New Orleans, two coastal cities in decline, lavished with money after their floods, and doomed to be on perpetual life support, challenge us to ask a fundamental question. Does having a flood wall increase the numbers drowned? This may sound like a ridiculous question—of course a wall to prevent flooding should save lives. Yet what if more people come to live in harm’s way behind the flood wall? What if, faced with the choice of evacuating inland ahead of an impending storm surge or tsunami, people choose to stay because they believe the wall will protect them and then, as happened in Kamaishi and New Orleans, they are wrong in their judgment? What if the “cure” causes more casualties than no intervention?

There are no tsunami walls along the Pacific coast of Chile. In the great nighttime Chile earthquake and tsunami of 2010, some 200 people were drowned. In the daytime 2011 Japan tsunami, despite (or because of?) the tsunami walls, the toll was 20,000.