39 percent of stocks had a negative total return. (Two out of every five stocks are money-losing investments.)

39 percent of stocks had a negative total return. (Two out of every five stocks are money-losing investments.)

Most stocks lose money. That’s right, so forget about the financial services industry’s mantra to buy stocks and hold them forever. Ignore the moment-by-moment media anxiety—Dow up! S&P 500 down!—that plays to the emotions of fear and greed to grab your eyes, ears, and money. Instead, stay calm and look at the data, not the marketing.

Consider the longest secular bull market most people today have ever experienced, 1983 through 2007. Blackstar Funds studied all common stocks that traded on the NYSE, AMEX, and Nasdaq during this period, including those delisted.1 They then limited their research universe to the 8,054 stocks that would have qualified for the Russell 3000 at some point from 1983 through 2007. During this period the Russell 3000, accounting for 98 percent of U.S. stock liquidity, rose nearly 900 percent, yet:

39 percent of stocks had a negative total return. (Two out of every five stocks are money-losing investments.)

39 percent of stocks had a negative total return. (Two out of every five stocks are money-losing investments.)

18.5 percent of stocks lost at least 75 percent of their value. (Nearly one out of every five stocks is a really bad investment.)

18.5 percent of stocks lost at least 75 percent of their value. (Nearly one out of every five stocks is a really bad investment.)

64 percent of stocks underperformed the Russell 3000. (Most stocks can’t keep up with a diversified index.)

64 percent of stocks underperformed the Russell 3000. (Most stocks can’t keep up with a diversified index.)

A small minority of stocks significantly outperformed their peers.

A small minority of stocks significantly outperformed their peers.

Blackstar provides the stark reality supporting the last point: The best-performing 2,000 stocks—25 percent—accounted for all the gains. The worst performing 6,000—75 percent—collectively had a total return of 0 percent.

It’s obvious that a few stocks are responsible for all the market’s gains. This shows why it is essential to avoid the losers—and that there are valuable opportunities to profit from shorting, even in a bull market. But the long-only investor has it far worse: To garner real returns, that investor has to be extraordinarily lucky to pick only the outperformers and none of the portfolio-destroying disasters. The odds don’t favor this.

Imagine you are reading this in 1979 and we told you that General Motors, Woolworth’s, and Eastman Kodak—strong and undoubted Dow components2—would in 33 years all be bankrupt. You would never have believed us, yet it’s all happened. Large brand-name stocks give the illusion of stability, but there is none. They join the index long after their periods of greatest growth, when their size guarantees a future of GDP growth at best. What are the odds you would have picked only the survivors, let alone the winners?

But let’s assume for a moment that you possessed the extraordinary good fortune to pick only the 25 percent winners in the Russell 3000. You probably still don’t win. Human nature can’t take the pressure of the roller-coaster ride.

Consider Ken Heebner, whose results at Loomis-Sayles Peter Lynch called “remarkable.”3 Heebner opened his own mutual fund business, and on March 25, 2010, his CGM Focus Fund had racked up annualized returns of more than 18 percent since January 2000. That’s starting before the 2000–2002 crash and including 2008. These returns are unbelievable, but what happened? Investors behaved like … people. They poured money in after his 80 percent return in 2007, just in time for the fund’s 48 percent drop in 2008. Morningstar modeled the fund’s cash inflows and outflows to find that the typical investor actually lost 11 percent per year, despite CGM’s 18 percent annualized gains , selling during downturns in CGM’s performance and buying at upturns.4

Instead of buying more during or after Heebner’s or any other great investor’s disastrous periods such as calendar year 2008, investors sell. Heebner’s contrarian success comes with great volatility that most can’t handle. Investors chase last year’s winner, buying high and selling low.

If most stocks lose money and most investors’ emotions get in the way of profits, why invest in stocks at all?

The conventional wisdom for investing in the stock market is to grow savings beyond the rate of inflation. While experienced investors understand the concepts of nominal (the actual number) returns and real (the number minus inflation), most investors do not make this distinction. They are happy when their stocks are up nominally and unhappy when down nominally, even though inflation and deflation make the numbers irrelevant to what that investor has actually gained or lost. Real—inflation adjusted—returns are all that matter.

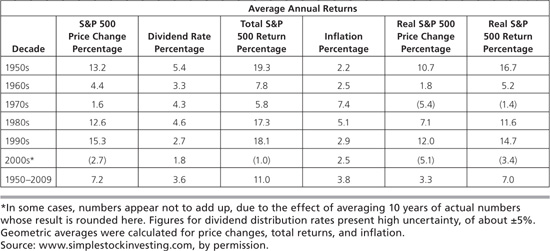

The conventional wisdom is right, because inflation does destroy the purchasing power of paper money. Unfortunately, whether the stock market provides the real returns to mitigate or eliminate that threat depends on when you happen to live. Average annual real returns may or may not be positive and, even if positive, may not be for long periods. Beating inflation is likely an accident of birth. Examine Table 1.1 of the S&P 500, including dividends, from 1950 to 2009.5

The 1950s skew the results dramatically. That decade produced the lowest annual inflation of all. Figure 1.1 shows the table information starkly and emphasizes the flat nominal returns from 1968 to 1983 and devastating real returns. Then, the 1980s and 1990s produced truly excellent annual real returns, followed by poor ones.

The data require more analysis. Unless an investor dollar-cost averages (invests roughly equal sums at regular periods) in the S&P 500 with these dividend yields, that investor risks choosing the majority of stocks that do not produce the S&P’s average and/or have lower or no yield, reducing or eliminating the benefit of reinvesting dividends.6 Remember, most gains in the stock market averages come from a minority of stocks.

But even dollar-cost averaging is no panacea, because incomes and savings increase with age, and age reduces the time available for compounding. It is completely random whether a person’s high-wage-earning years and greater investing returns occur during high or low inflation and therefore times of high or low real returns. During tough economic times, income and savings may not increase with age.

Table 1.1 S&P 500 Nominal Versus Real (Inflation-Adjusted) Returns, 1950-2009

Figure 1.1 Nominal and Real (Inflation-Adjusted) S&P 500 Returns 1950–2009.

Source: www.simplestockinvesting.com, by permission.

And human nature also puts the kibosh on dollar-cost averaging. Benjamin Graham and David Dodd7 notably described the simple problem, captured by Jason Zweig:

Asked if dollar-cost averaging could ensure long-term success, Mr. Graham wrote in 1962: “Such a policy will pay off ultimately, regardless of when it is begun, provided that it is adhered to conscientiously and courageously under all intervening conditions.” For that to be true, however, the dollar-cost averaging investor must “be a different sort of person from the rest of us … not subject to the alternations of exhilaration and deep gloom that have accompanied the gyrations of the stock market for generations past.”

“This,” Mr. Graham concluded, “I greatly doubt.”8

Graham didn’t mean that no one can resist being swept up in the gyrating emotions of the crowd. He meant that few could. To be an intelligent investor, you must cultivate what Graham called “firmness of character”—the ability to keep your own emotional counsel. Otherwise, you risk ending up like Morningstar’s estimate of the average investor losing money in Heebner’s super-performing CGM Focus Fund, buying high and selling low.

To preserve the purchasing power of your money against inflation and grow it at a higher rate, you must invest early, with discipline, and for a long time or earn multiples of your wages later to make up for the shorter time period available as you age. You must be the rare exception to human nature—a superhuman being that can, unflinchingly and without emotion, dollar-cost average and reinvest dividends via an index fund for decades.

“In the long run, we are all dead.”

—JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES

All the common investment statistics used to support the case for owning stocks—as Jeremy Siegel argues in Stocks for the Long Run 9—are misleading at best. Siegel asserts that 130 years of market data prove that “stocks, in sharp contrast to bonds, have never suffered negative after-inflation returns over any 20-year period or longer.”10 He further adds that 200 years of data show that selling in a bear market is always wrong: “You take the pain, you hold your position, and you will be rewarded in the future.”11

How many investors building investments for retirement—for plain old self-sufficiency—are interested in twenty years of being even with inflation? Or that over 200 years , not selling in a bear market means you will be rewarded “in the future”?

This suggests, not that stocks are for the long run, but rather, that in the long run, we are all dead. And probably preceded by not having enough money, which more data will show us next.

Tax-advantaged accounts, such as 401(k) plans, postulate that a high return on pre-tax contributions compensates for anything other than hyperinflation. But this is no solution. During tough times, companies cut back on their employer matches and employees reduce or eliminate their contributions.12 Some people simply prefer foregoing “free” money—pretax and allowing greater future returns—to have cash now. Job loss takes away the choice of whether to have the benefits at all. Even among those who retain jobs and contribute to 401(k) plans, 22 percent had borrowed from their accounts by the end of 2010, which precludes them from further investing until they’ve paid off the loan.

No wonder the average balance in these accounts, for those over age 55 with ten years participation, was only $233,800 as of the end of March 2011. Overall, including those with or without a tax-advantaged plan, in 2011 the average 55- to 65-year-old had a net worth of $180,125 and the average for those 65 and older was $232,000.13 These amounts are simply insufficient as a base for old-age support14—and this is for the oldest, richest group in society, the large mid-boomer age cohort.

Among those who do save and invest, most unknowingly confuse stock market expectations with the concept of “store of value,” which is the notion that there is something absolutely safe—gold, real estate, timber, farmland, livestock, government debt, or stocks—that will retain value through all known and unknown events. In Wealth, War and Wisdom ,15 Barton Biggs studied data to determine if any investment vehicle was able to retain value through the worldwide dislocation of World War II, including inflation, periodic market closings and, in the case of eastern European countries and those absorbed into the U.S.S.R., tens of millions of investors, business owners, and landowners who endured 50-year market closes, worthless currencies, and the elimination of private property.

His conclusion? The best you can do is own some land with livestock, crops, and water. But, he emphasizes, even if you do have some, the neighboring have-nots will likely have more guns.

Most investors want both some “store of value” and real returns above inflation. They accept the necessity of stocks and the stock market, but they need the mindset of the short seller to manage stock risk. A short seller’s approach to risk, when combined with a sound, value-managed long side, is as close to the holy grail of store of value plus real returns as is possible for stocks.

The best long strategy is small-cap value, according to research by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French.16 The problem is that there is massive year-to-year volatility. The money manager employing this strategy alone would have had, for instance, a terrible 2008 followed by an incredible 2009. Because these peaks and troughs, even amid superior long-term performance, scare away most investors, few registered investment advisors (RIA) dare to use it, for fear of going out of business. RIAs accept the market average, also a ready defense against liability.

But investors, money managers, and clients can obtain substantial compounding of absolute and relative returns. On the long side, this requires a small-cap value strategy and catalyst-driven special situations, using liquidation value, activist investing, corporate restructurings, and more. Such a strategy was developed by Benjamin Graham and used by his student, Warren Buffett, during his hedge-fund days prior to closing the fund and running Berkshire Hathaway full time, and it is supported by extensive studies analyzed in Tweedy Browne’s comprehensive overview.17 Small-cap value (which Tom presents in Chapter 6) when combined with the short techniques in this book, grows returns better than long investing alone.

Value is well known and studied exhaustively, while risk analysis and the practices of short sellers are not. Whether we entrust our money to others, invest it ourselves, or invest client money, we need to understand and employ the tools necessary to recognize aggressive accounting. This allows investors to avoid the blowups or use them for profit and to manage risk in a long-short portfolio. Lose less, make more.

Here are just a few of the reasons why learning to recognize aggressive accounting in order to avoid losers or, like short sellers, profit from it is essential to risk management and investing profits.

Legg Mason’s Bill Miller was perhaps the best-known proponent of the view that lowest average costs wins, yet the formerly record-holding mutual fund manager blew up all his accumulated gains through individual stock cataclysms. He owned all the infamous losers in the first decade of 2000—Enron, Freddie Mac, WorldCom, Wachovia, Bear Stearns, and AIG. Value investors act contrary to the market by averaging down to gain a better price on businesses they know well . Miller clearly didn’t know what he was buying well enough to justify taking extreme contrary positions with such large percentages of the portfolio.

The problem, to use one of his numerous disasters as the extreme example, is that, if you dollar-cost average a Bear Stearns that loses almost everything—it doesn’t matter. You’re finished. Do it enough times, and your pockets are inside out. The index, at least, is not going to zero, but individual stocks can. So if you dollar-cost average anything other than an index, you still have the problem of how to avoid the portfolio-destroying disasters. Repeat: With just a few blowups, Miller eliminated all his years of breaking records as the manager with the longest consistent streak of outperforming the S&P 500.18

To buy any individual stock, let alone take any contrary market position, you have to be able to identify earnings quality concerns in your companies’ financials, and you have to stay away from anything you don’t understand well enough to do so.

The universal stock performance benchmark, the S&P 500, is in many ways a momentum-investing tool. It works this way: As more and more investors buy a stock, the price rises, which brings a higher market capitalization. At some point the stock may reach the size at which it moves up the ladder of market caps into the S&P 500. If the stock increases more, it carries a greater share of the S&P 500 index itself, which is market-cap weighted. At the same time, investors may desert other companies in the index. These companies then drop in market cap and eventually fall off the index, representing a smaller share of it on the way.

Therefore, stocks’ greatest gains may precede entry into the august group of the top 500. The more they rise, the less they can gain on a percentage basis. If you are ExxonMobil with the number one market cap in 2011, what will it take to go up 10 percent, or 25 percent, let alone 50 percent or 100 percent? (Note: We believe that 2012’s number one company, Apple, is not typical—and at writing still not all that expensive. But when it or any company becomes such an overwhelming percentage of the index and you own it, it becomes doubly important to hedge.) And if you are a large company and your stock declines, the decline is far weightier. Ten years ago Yahoo! and AOL and Cisco Systems were all near the top of the S&P 500. Not today.

There are many index options available, but each has its own issues—whether it’s the broad Wilshire 5000 which, in effect, becomes an index for the economy, or an equal-weighted index, or one of the indexes of various market capitalization stocks where winners leave the index.

Indexes are the best of poor alternatives for anyone not investing in individual stocks. The minute that investors choose stocks, they have to learn about earnings quality.

Financial professionals really have no choice but to give clients what they want, like the familiar and “safe” Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Microsoft, Intel, and ExxonMobil. The RIA is hamstrung by human nature. Clients want riskless real returns, but they don’t know what that means. So Steve the RIA delivers the average, and in a bad year, he says, this is what the market did. He’s the broker equivalent of the company information technology professional who buys Microsoft or IBM or Intel products because he won’t lose his job if there’s trouble (“everyone else has it”), but risks losing it if he buys a lesser-known company’s better product that later causes problems.

RIAs rely heavily on modern portfolio theory and its asset-allocation practice. Most buy mutual funds representing supposed asset classes—growth, value, large cap and small cap stocks, gold, bonds, and so on—that ostensibly act differently from each other. Then they follow a strict percentage allocation among the funds and rebalance regularly—quarterly or annually—to return the funds to the correct percentage. This means that, if the mutual fund manager does well, RIAs who own the fund for clients sell that fund. No wonder mutual-fund managers are commonly compensated for being within a few percentage points of the market average and not for beating the benchmark by more than a few points.

Investors must learn enough about real risk from aggressive accounting to manage their own money, client money, or those who manage it for them, but no one really wants to hear about it. Optimism sells. From as long ago as when Edwin Lefèvre’s Reminiscences of a Stock Operator 19 chronicled early twentieth-century shorting, and even after the accounting scandals of the boom ending in 2000, it’s still considered un-American at best and criminally manipulative at worst to focus on anything negative about a company—let alone in a company’s reported information—that could affect its stock. Short-side thinking seldom appears in the Wall Street Journal or the Financial Times (whatever other considerable merits we find in these fine publications). The worst you’ll encounter is someone advising caution or that a stock is “overbought.” True risk management—not just mediocre mimicking of the overall market—doesn’t sell. Blind and baseless promotion does.

The indexes reinforce the mythical stock market where something—somewhere—is enduring, when it isn’t. The indexes themselves are anything but. The retail investor is not going to pick only winners, and the indexes don’t help, because of their structure and human nature. Successful professionals will have too much money under management to reap real returns on the long side alone, because they can’t buy the less liquid small caps that Fama and French proved outperform. They can’t accumulate big enough positions to make a difference in their returns—“move the needle”—and so are restricted to large caps that mirror the indexes and the economy. Or they will fail to employ the short-side mindset to avoid massive drawdowns. There simply are neither indexes nor individual stocks for the long term.

With the tools in this book, investors will increase their chances of achieving high real returns by weeding out or avoiding the stocks that perform so poorly that they will ruin overall returns and possibly destroy capital permanently.

Everyone will have poor performers, even among stocks with good financials and business operations. No one ever has all the information about any investment, or about the future. But poor performers with fictitious revenue or deteriorating balance sheets are different. They can be identified, sold, or avoided. Savvy investors can attempt to profit from them by shorting the stocks. We believe that no investor must short a stock—though it can enhance returns. But we do believe that the short-selling expert’s tools—and the shorting mindset—can lead to successful investing, simply by avoiding the statistical basement revealed by the data.

This book does not advocate or explain shorting or selling based on overvaluation, fads, frauds, or poor business models, even though these make up the overwhelming majority of stocks sold short. Surprisingly, very bright fundamental investors—those who do bottom-up research on companies and their industries—will only short on these bases, even though they are willing to go long on stocks with specific catalysts. It’s as if investors with enormous skill at ferreting out value where no one else can find it suddenly have memory loss on the short side.

Why are these poor bases for shorting? Because overvaluation can continue indefinitely. Fads can do very well against all odds for a long time, not least because those who follow the fad will buy the stock. Frauds are very hard to identify until after the fact. China frauds in 2010–2011 fooled brilliant investors who had decades of success. Trying to identify business models that will fail is extremely difficult; determining when they will fail is all but impossible. Doing so requires that the investor be right, even when being right is impossible to know and the risks of being wrong are devastating.

Shorting or selling on those bases is simply too hard, risky, and unnecessary. We recommend waiting until there is aggressive revenue recognition, weakening balance sheets, and deteriorating cash flow trends. It’s the flip side of value-with-catalyst, which is fundamental analysis of value combined with a catalyst for stock market buying to boost the price to realize that value (see Chapter 6). So too, on the short side. Wait until there are negative catalysts for profits in the near future—a year or two at most, the rough time period that the value-with-catalyst investor seeks. It’s easier and more effective, the equivalent of “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes.”

It’s useful to look more closely at why those who insist on shorting only fads, frauds, and failing business models and those whose methods mean they have to be right, are wrong.

The conventional short seller’s first target is fads. This mindset says that a company like shoemaker Crocs will make money with a one-trick pony until a fickle public turns to the next thing and the stock dies. Here and elsewhere, short sellers short the stock and watch with disbelief as it rises until margin calls put them in a hospital bed.

Next come frauds, situations where short sellers are certain that fraud will send a stock to zero. How can they know? Legions of China small-cap stocks proved fraudulent in late 2010 and early 2011 and destroyed investors. Even cautious value analysts and money managers like John Paulson, famed for making billions with foresight of the housing collapse, took acid baths on these. Who knew that these and Tyco, WorldCom, Enron, and Elan were elaborately choreographed frauds until they were revealed to be? The handful that raised any questions were isolated. The media and company spin drowned them out.

The third favorite of the short investor is failure of a business model. As Netflix shares zoomed almost ten times from early 2009 to July 2011, investors all along the way were sure Netflix would fail, given the increasing cost of its content, competition from low-cost or free outlets such as Hulu, and other factors (see Figure 1.2). Well-known money manager Whitney Tilson shorted the stock and in December 2010 began a public written exchange with CEO Reed Hastings. (It was educational and riveting, and both deserve credit for putting themselves on the line.) Hastings converted him; Tilson covered his short at a loss in February 2011.

Unfortunately, Tilson’s short case was eventually proven correct as shares that shot to $300 collapsed in stages to the $70s as the year came to an end.20 Even the experienced are susceptible to human psychology and investment-world reality. How many investors shorting on the way up—a long steady rise—can withstand the broker’s margin calls on during that rise until the stock crashes (see Figure 1.2)?

The last of the four flawed shorting characteristics is that of the short seller who “needs to be right.” If the short seller is in the business of profiting from shorts only, rather than managing risk in a long-short portfolio through avoiding disasters beforehand, there is no choice: That short seller must be right. Professional short sellers must build substantial stakes in short bets, so even one going against them big time can destroy their business. Long-short investors can face problems when the short side of the portfolio goes seriously against them, but there is far less risk of permanently losing capital than there is for the short-only investor.

Figure 1.2 Netflix Stock 2009 to December 9, 2011.

Source: www.freestockcharts.com, by permission.

These four shorting characteristics provide no real risk management, but others can. This book’s unique tools do short sellers one better by making money in both bull markets—when short sellers can have real problems—and bear markets. That’s the difference between a short seller and a risk manager. Our tools manage risk in a way that works, no matter which direction the market is moving.

The case studies that follow show you how to use short sellers’ tools to manage risk, how to figure out which stocks you own should go, how to avoid others, and how to short some that may have even made money for you before, investing long.

Before we look at the case studies, we should note that there’s nothing magical or mysterious here. If you want to manage your risk, you need what Charlie Munger, vice-chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, defines in his characteristically blunt style as assiduity: “You gotta sit on your ass and do it.” Everything in this book is about information available for anyone to read. The problem is that most people don’t read it—and if they do, they don’t read critically. So, while companies provide the information, there is so much there that most don’t look at or know what it is that they’re looking at.

The first and most superficial level of communication from companies whose stocks you own are their press releases. PR departments take management information and spin it to reinforce the investor’s need to believe in an endlessly rosy future. The critical reader can glean tipoffs, but the volume of this material makes it an inefficient use of time.

Annual reports can be worse, glossy feel-good letters, rising charts, happy employees, and customers made giddy by the company’s products. This is about selling, selling, selling, and obfuscation. In one startling act of marketing and hubris during the biotech boom, photographs in Human Genome Sciences’ annual report for 2000 posed members of top management similarly to figures in the famous classical art behind them. (It’s easy to sympathize with the analyst who called it the “cheesiest thing” he had ever seen, but despite his accuracy here we suggest he get out more.21)

Don’t be distracted! The real bodies aren’t posing. They’re buried in the footnotes.

The next level is the Wall Street analyst report. These report authors are called sell-side analysts, because they want to sell their bank’s services to management, and they are cautious about writing anything critical. These include the toady analyst you hear on quarterly conference calls saying, “Great quarter, guys.” The reports may contain nuggets of useful industry information, but they won’t help you learn about risks for the specific company the analysts are courting.

The only information that matters comes from the company’s filings with the SEC. The real information is in the actual filing’s pages, and, more important, in the footnotes, where the data aren’t always presented in easy-to-read tables. Even some of the best analysts’ eyes glaze over at footnotes, but that’s where management discloses what the law says it must. Some of the best short sellers—whether short-only or managers of a long-short portfolio—miss or do superficial analysis of these details, because they focus on fads, frauds, failures, and the need to be right.

Crocs is a great example of a fad. These colorful shoes hit the market, and within months everyone had them—from children to your least fashion-conscious friend. Among investors, just about everyone knew rubber shoes wouldn’t survive the usual economic boom and bust—a full market cycle. By definition, a fad is going to be exciting for a while and then peter out. When that happened at Crocs, the company wouldn’t have other revenue channels through which to grow the business. But none of this makes a stock a good short, because people tend to buy consumer fads, and often, in the excitement, buy the stock, and momentum investors grab on for the ride.

Indeed, Crocs catapulted over six times, from $12 to $80. A lot of people made money; fads can be very, very profitable for the upside investor if entrance and exit are properly timed. But attempts to time the market can teach you some very harsh lessons (in Chapters 7 and 8, we’ll look at when market timing is warranted and can work).

There were plenty of investors shorting the stock at every price from $12 on up, and for many, this was what happened. Shorting stock requires a loan of shares from your broker. When the price of the stock you shorted (borrowed and sold) rises, your broker issues a margin call—requires you to put up cash against the loan to cover the rise in the stock’s price. Many investors who were short Crocs, got margin calls they couldn’t meet, were forced to cover (buy back the stock), and suffered enormous losses. This is why simply finding a fad and shorting it can never be called risk management. It’s added risk.

Crocs did eventually drop like a Mafia victim in cement (not rubber!) overshoes, but it was only a great short when it fell from its high of $80 back into the $50s and $60s, because that’s when John’s accounting analysis flagged the stock, finding the inventory issues buried in the footnotes. They also extended payment terms that got picked up in the DSO. There were crocks of Crocs in the stores and even more stacking up in their warehouse. It was foolhardy to short the stock before that, even though it was overvalued—selling for multiples of the little earnings it had—because there was no way to know that popularity wouldn’t drive the stock higher. An overvalued stock can simply become more overvalued.

But when signs showed that the revenue was accelerated—the extended payment terms gave customers the incentive to take on inventory even when inventory was already piling up—the company would no longer be able to sustain its growth trajectory. The catalyst was coming. When Crocs issued earnings reports showing increasing inventory—inventory it could not sell and which clearly made the growing revenues look unsustainable—the stock was in the $50s and $60s. As Figure 1.3 shows, the market soon figured out what John had already seen, and Crocs’ stock price plummeted to single digits.

Figure 1.3 Crocs: 2006–February 28, 2009.

Source: www.freestockcharts.com, by permission.

Did it hurt anyone to wait? No, and this is one fundamental thing about short selling that is so obvious that it is confounding—and ignored. You make as much money shorting a stock that falls from $70 to $5 (93 percent) as one that falls from $100 to $5 (95 percent). Waiting for the right time isn’t going to cost you money—in fact, it means you make money before the retail investor no longer props it up and the accounting issues can bring the real profits. Figure 1.3 shows this principle, where shorting at each black arrow point led to similar gains.

A likely fad stock in the making is Rovio, the Finnish company that developed the hugely popular game Angry Birds. At this writing, Rovio has raised $42 million in venture capital and plans to go public in a few years. Short sellers will be watching. If Rovio does go public, it’s very possible that everyone not a child who loves Angry Birds will buy the stock. They will ignore the fact that electronic gaming is a remarkably difficult and fickle business in which to have repeat successes. It will make a lot of money for many people. But the time to short will be only when accounting analysis shows that the revenues aren’t real or aren’t sustainable. The Angry Birds thumb drives at Staples don’t bother us—yet. We wouldn’t short Rovio until seeing the whites of those Angry Birds’ beady eyes—when the revenue and earnings growth can’t continue.

What does this mean for you if you don’t want to short? Understand why you bought a stock. Know when your love of a product or a company or the buzz about one or the other has added risk to your portfolio because you’re following a fad. Avoiding the stock because it’s a fad makes sense, but buying it isn’t irrational when you can take advantage of the fad stock’s buyers. The problem is that holding it can be terminal, if you can’t or won’t look to see when the fad is going the other way, such as when inventory buildup signals the end of consumer demand. When you find this, sell in order to pocket your gains or reduce losses.

Short sellers take on unnecessary risk by focusing on fraud because frauds are preceded by accounting issues that can be identified.

Enron fell from the sky to bankruptcy in 2001, but forensic accountants weren’t surprised. It was clear the revenue wasn’t real if you knew where to look—and even if you didn’t. When the lonely but astute analyst pointed this out in an April 17, 2001, earnings conference call, Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling called him an unprintable name. Every major financial news organization covered this event. That should have been a red flag for every investor to start looking harder at everything Enron was saying and doing.

The problem is that constantly looking for fraud clouds your judgment. If you require a manager to be a crook, you start focusing on things you can’t know—the particular details that can prove a fraud, such as actually lying about products, sales, and more. It’s impossible to know when the lie is told and practiced, because people hide it. You might see indications, but if you are both wrong and short, you can lose a lot of money. If you’re just trying to figure out what to hold and what to sell, you can end up selling too soon or churning your account to the point that you can’t make any money.

Our process focuses on revenue. Until we see revenue problems—revenues that may be falling while inventories build and credit terms lengthen—we won’t bet on whether a company is a fraud. It is rational to want to short a fraud, but the correct focus is not on whether a manager is lying, but on whether a company is practicing financial chicanery.

Short sellers rightly look for business models that can fail, but they can’t know when to short without a specific catalyst that, if it materializes, will kill the company’s model and let them profit (or if you own it long, destroy your wealth). What many people do is say that some company, usually one with a massively high multiple of earnings or free cash flow, can’t continue. But it can, and it can do so indefinitely—that’s an “open situation.” A good example of the former is the municipal bond insurer Ambac, whose business model was unsustainable. Examples of the latter are Netflix, which had a high multiple that just got higher and higher until the edifice cracked, and the restaurant reservations system OpenTable.

Because the incentives to take on more debt are so great for certain businesses, and because, throughout history, credit has ebbed and flowed, spending time on the Ambac case may pay you back many times over in your investing life.

Ambac founded the municipal bond insurance (monoline) business in 1971, providing insurance to governments and companies against the possibility that the issuer of a bond they had bought would default. This would leave the insured short of assets and less able to meet its own obligations.

When buying a policy from any insurance company, the insured expects that the insurer will pay if the triggering event occurs—whether a car crash, death, medical cost, flood, or hail damage to a roof. Ambac’s customers paid for protection against the event of the bond issuer’s default.

Regulators require insurers to maintain capital levels against potential claims. The regulators don’t require capital equal to the potential losses from all policies, just as they do not require banks to maintain capital to cover all mortgages defaulting. These businesses make money taking in more than they pay out. They make more money by evaluating risk, so that they do not face losses equal either to their current capital or capital they can raise through debt.

The industry faces a dilemma. Insurers must maintain prudent underwriting standards so as not to face losses that wipe out their capital. But to make more profits for shareholders, they must also raise capital through debt—becoming more “leveraged”—to cover more potential losses, write more policies, and collect more premiums. There is an inherent tension between underwriting standards and profits generated through more policies and more debt leverage. We know from the credit crisis that banks, for example, threw underwriting standards to the wind to lend more to anyone. When the mortgages defaulted, the banks couldn’t cover their losses and blew up.

Ambac chose to raise more and more capital to maintain higher profitability. The credit rating agencies—as they did with countless others—rated Ambac highly, so lenders lent scads of money to Ambac at low cost. Because Ambac had a high credit rating, it attracted customers whose own lenders would delight at Ambac’s high rating and lend to Ambac’s insureds at lower rates. Everyone fed at the easy-money trough.

But Ambac went to the edge of the cliff. It insured collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), comprised of assets including mortgages. We all know what happened to all but the highest quality mortgages in the small minority of high-quality CDOs, and at this writing there is no sign that the United States or many other countries are in sight of recovery. Money is tight again.

The key point we make here is that the time to short Ambac was not when it was leveraged 125 to 1.22 If credit had continued flowing like Niagara Falls, Ambac and countless others could conceivably have stayed on the merry-go-round indefinitely. This was the same situation that led investment banks like Lehmann Brothers to lever assets to shareholder equity as much as 30 to 1, with disastrous results.23

In a bull market, you can use leverage, make acquisitions, and do all sorts of things, because easy credit allows almost any business to raise money. But as we know from 2008, credit markets can seize up faster than a motor with no oil when the market turns bearish. When the money tap is turned off, a business model that depends on huge leverage suddenly dries up and becomes unsustainable. That’s the catalyst and when you should short a business model. Once John saw the credit market dry up, he shorted Ambac, which eventually went bankrupt.

Until fall 2011, the most public business failure debate concerned whether Netflix was a good short. Many investors had made piles of money on its stock, which seemed only to move up. The skeptics’ major arguments were that it was selling at such high multiples that growth couldn’t keep up and that deals with the content providers would be renegotiated at higher rates that hurt margins, meaning that the high multiples would contract and the stock would dive.

For years, management did a brilliant job managing the transition from mailing of discs to online streaming. Netflix had more subscribers than the largest cable company, Comcast, and had increased market share and reduced the costs of sending out DVDs. All of this boosted the company’s revenues and profits. There were no signs of accounting manipulation to make Netflix look better than it was.

Netflix was an “open situation.” There was nothing yet to keep the stock from going up, even if in the long run it might face ruin or competition. Few businesses—even first movers like Netflix—see their advantage exist forever. But why short “hoping” for a decline in five, ten, or more years? You have to see management using accounting aggressively to mask deterioration in their business. Until then, the situation is “wide open.”

Netflix shares multiplied almost six-fold in 18 months and tripled in 14 to July 2011. Those who shorted on valuation got destroyed. Meanwhile, the company continued buying back shares without regard to valuation, even as its share price exceeded bubble-era multiples. When buybacks are not opportunistic, they mask options grants or—worse—raise the question of whether they are specifically to transfer shareholder wealth to options holders and insider sellers. Worst, at the time that the buybacks continued without regard to valuation, CEO Hastings was selling under a prearranged trading program—not illegal, but not good.

On top of that, Hastings was spending valuable time engaging money manager Whitney Tilson to convince him that his Netflix short investment case was wrong.24 Then the company bungled communications over what it might do with its physical disc business and shares plummeted. And when Netflix revealed at its third quarter report on October 24, 2011, that it had lost 810,000 subscribers25 and admitted that it would be unprofitable for the next quarter, the stock collapsed 35 percent in one day to $77. It’s hard to believe Hastings didn’t see the trouble ahead when the company was buying back stock at $218 and he was making the bull case in public debating Tilson.

Another open situation was the aptly named OpenTable, debated almost as widely as Netflix. For a time, who could say that every restaurant in America that takes reservations wouldn’t be using OpenTable? And then other countries? Or that some company like Amazon or eBay or Google (who knows?) wouldn’t pay a huge premium to add it to its arsenal? Indeed, Google ponied up for Zagat for the first signs of competition.

Then holes began to form in the OpenTable cloth. It changed the amortization period for its software installation, using a reduced customer life—the period it retains a restaurant customer—which makes revenue and earnings look good, but only by borrowing from both down the road. Its frontloading revenue recognition was confirmed by weak deferred revenue trends. Days sales outstanding (DSO)—the time between when the company makes a sale and receives the revenue—rose dramatically, suggesting that customers had trouble paying, or that the company extended more favorable terms, or both. The stock was a profitable short in late 2011. (Later, a buyback forced a short squeeze. It was a poor company allocation of capital and a short-term fix only, so OpenTable again became a profitable short.)

The time to sell or short is not when you think a business model can’t survive. The time is when the numbers suggest that management is covering up poor performance and when the stock has already begun to fall. We want to time our actions by seeing specific catalysts through our detailed financial statement analysis of revenues, inventory, accounts receivable, loss reserves, and more.

Typical short sellers have to take large positions and defend them—often publicly and for a long time—in order to make money. They are not risk managers; they are money managers who see their circle of competence—their best chance to make money—as identifying fads, frauds, and failing business models and betting big. Short sellers who do not have a long-short portfolio—who only short—cannot afford to be wrong. Thus, they are the most vocal and public promoters of their positions.

By running a long-short portfolio, managers can use shorting to manage risk and can simply close a position when it goes against them. Yet you still see them writing and presenting a “terminal short”—a short only worth it because it’s “sure” to go to zero. Why do they have to short only when they see a 100 percent gain as a “sure thing” (a short can only gain 100 percent) when, at the same time, they will make a long investment in an undervalued stock with a 40 or 60 percent upside? Plus, despite having declared a “terminal short,” many cover the short right away, closing the position with only a slight profit. Long investors seem to lose all sense when they turn to shorting. This deprives them of the real benefits of a long-short portfolio.

But there is a difference between being right and making money. Many very good long investors—excellent at valuation and business analysis—don’t fully grasp quality of earnings and signs of aggressive accounting. They may know enough to be comfortable avoiding a stock, but they lack confidence when it comes to identifying negative catalysts to actually short the stock.

The main reason for this aversion is this: You have unlimited gains on the long side versus, at most, a 100 percent loss. But a short offers at most a 100 percent gain versus potentially unlimited losses. But show us an investor who actually holds a short that goes against them extremely. Earnings quality analysts don’t short without analyzing short interest and days to cover in order to avoid the squeezes that lead to margin calls, covering at any cost, and catastrophic losses. The “unlimited losses” argument is only relevant to the unprepared short seller.

Whether selling a stock to avoid a blowup in your portfolio or to actively short, it’s essential to know some considerations that aren’t necessary to investing on the long side. If a lot of shares are sold short and the stock is thinly traded, the slightest good news could be very bad. Many people have borrowed shares, betting on a decline, after which they will return the shares to the lender and pocket the difference. If things go the wrong way and volume isn’t high, they can get stuck having to cover their short (buy the shares back to deliver to the lender) at any price as it rockets up from increased demand. Let’s look at the two key ways to avoid this pain: percentage of float sold short and days to cover.

For the first, use online sources to find the amount of shares shorted of a stock. Compare that to the float. Float means the shares that can be freely traded any given day, excluding restricted shares, insider holdings, and shares held by those with more than 5 percent ownership. The higher the percentage of shares sold short (short interest) of float, the greater the risk that any positive news can send shares soaring, because demand will exceed supply. This is a classic short squeeze. The short sellers’ losses mount, they begin to cover, and their buying drives the price up further. No wonder any investor who ignores this metric often endures painful losses.

The second metric is days to cover. Here, divide short interest by average daily share volume traded. This is an indicator of how tough it would be if all the short sellers had to cover at once. If days to cover are low, there is likely enough volume to allow short sellers to exit their positions relatively easily. If days to cover are many, then the risk of not being able to exit as prices rise is too high, and the dreaded short squeeze looms again.

The best way is to focus on aggressive accounting and avoid shorting where everyone else is also doing it, such as with fads or suspected frauds. It’s a head-scratcher why contrarian investors on the long side don’t check to see how much company they have on the short side.

Instead of needing to be right, wait for the obvious indicator of accounting trouble and act then. You have your negative catalyst. This reduces risk and also the need to be massively right on one single position or risk serious portfolio loss through a couple of short positions in a long-short portfolio. This guarantees a two-fold edge. Tactically manage positions. Do not make massive bets on fads and ride them through a market cycle. Use fundamental and trading skills where your advantage is greatest: in accounting. You are less likely to get destroyed in any position and definitely not overall.

Sometimes, even if you are right, you still can be wrong. America Online (AOL) was making people rich before it merged with Time Warner and crashed. On October 26, 1998, AOL had a P/E ratio of 205, yet it broke out and zoomed. Anyone shorting on valuation was in a world of hurt when AOL peaked in April 1999 at a P/E of (ready?) 532! You can lose capital permanently with just one trade like that. The ambulance doesn’t get there in time.

But a lot of successful short sellers didn’t bet against the company on valuation, which would be bad enough, because everyone who had an AOL account was an owner or potential buyer of the stock. There actually was an accounting issue. Sensible, sound investors shorted, based on AOL’s capitalizing marketing expenses, treating them as an asset. AOL took its marketing expense off its income statement, which inflated its earnings per share.

The catch is that by the time this accounting issue of 1995 and 1996 had passed, it didn’t make a difference. The company no longer needed the capitalization of an expense to appear profitable. Nothing was fictitious about AOL’s revenue, which grew an astonishing 50 percent to 100 percent per quarter as the company dominated its space. The eventual small SEC fine was a mosquito bite. The short sellers did indeed identify an accounting issue. It just didn’t matter.

In this book we emphasize how financial analysis prevents the mistake where an investor unearths an accounting issue but does not understand whether it matters or not in the real world. AOL was playing with accounting by capitalizing expenses, but it wasn’t playing with revenue. It can be a terrible sign if a company capitalizes marketing expenses, but not when, as with AOL, demand is so explosive that revenue growth overwhelms the expense issue, just as a skyscraper overwhelms the old house next door that a recalcitrant owner refused to sell. The next chapter is on revenue recognition, because almost all aggressive accounting and earnings quality issues originate there.

That’s one reason why our process helps categorize accounting issues according to the most problematic. The best situation is aggressive revenue recognition masking softening demand. Those who did not see the revenue for the capitalized expenses—the accounting forest for the trees—and shorted AOL got killed and weren’t around to profit when the stock did finally collapse after the merger with Time Warner.26

Focus on the real accounting issues and don’t let the accounting grain of sand distract you from the beach as at AOL. Keep away from the emotion of having to be right.

The rest of this book looks at how to use the short seller’s toolkit to avoid the traps and time our actions. We’re going to show how we identify aggressive accounting, manage risk, and tactically manage positions.

Focusing on risk management, rather than making big profits from shorting, is a good way to manage your portfolio risk and keep growing your wealth. After all, as the tech and housing crashes have shown us, one of the very best ways to make money is by avoiding loss. Learn how to look at the fine print, and you can make and keep money passing on, selling or yes, even shorting, many stocks. We will show you when to make a change in your portfolio and how to spot that right moment. Most people see only the money they make from their successes, but the reality is that they can make as much or more by not losing it all on one stock or a bear market. Minimize risk and loss and you maximize wealth.

But what we do also works in bull markets. So bull or bear market, any investing weather, this is why the correct short-selling analysis works.

We open and close with this simple point: Most stocks lose money. Why should it be yours?