Like technical analysis, market timing is controversial. Most market timing critics agree that “It’s not about timing the markets, it’s about your time in the markets.”

Every fundamental long-only investing style involves some form of “buy” and “hold.” The investor buys, having made a case for the investment, whether one with specific catalysts, or one closing the arbitrage between current valuation and intrinsic value, or both. This chapter is addressed to those who wish to avoid massive bear market losses, or “drawdowns.” Drawdown is a money-management term referring to any drop in investment value, no matter how short term. Even if the long-term return is, or would be, acceptable to excellent, drawdowns are scary.

Recall Chapter 1’s discussion about Morningstar’s analysis of investors in the highly successful CGM Focus Fund run by the extraordinary money manager Ken Heebner. Despite his long-term annualized outperformance, Morningstar concluded that most of Heebner’s investors lost money. His drawdowns—periods of substantial and impermanent paper losses—reinforced the average investor’s fear of selling at lows, rebuying at times of enthusiasm, and succumbing to bull market good feelings. Confirmation bias leads the average investor to buy high and sell low, losing money, just as in Morningstar’s study of the average investor in CGM Focus Fund.

Let’s think again about “time in the market.” The benefit of a long-short strategy using John’s short-side risk management and Tom’s long strategy is that, while both benefit from the techniques in this book, the long side need not concern itself with either timing or time in the market. It does not require expert technical analysis or market timing if the short book is managed with discipline according to John’s practical methods. Why? Because with John’s short book management, the long book can have time in the markets with the short exposure managed so that any drawdown magnitude is reduced.

In the real world, it is the rare manager who has steadfast clients—usually the result of either well-off relatives or a fabulous first year that provides goodwill for a very long time. If that were not true, no funds would close after a bad year and reopen—with investors incomprehensibly willing to take another ride—so that the manager can attempt a good first year again! It also is the rare investor who has the market-history knowledge, calm, and steadfastness to stick with it in a period of massive drawdown, such as in 2008–2009, 2000–2002, or, even further back, 1973–1974, when drawdowns were massive in both nominal and inflation-adjusted terms.

The long-only investor without the ability to conquer emotion—and/ or without permanent capital—has no choice but to use market timing and technical analysis. But the long-short investor can use the techniques in this book to reduce drawdown magnitude, conquer emotion, and increase wealth. Those with lower-magnitude drawdowns will have more assets under management.

And so let’s look at how to use market timing to avoid massive drawdowns—peak-to-valley declines—in bear and sideways markets.

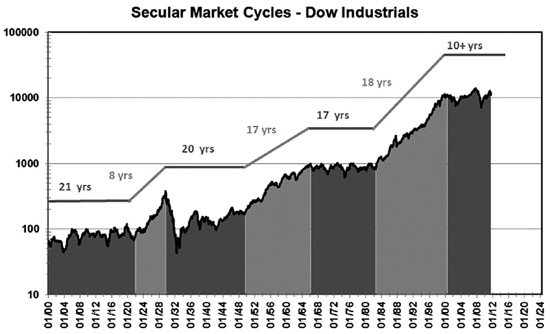

Bull and bear markets come and go in wavy patterns called secular and cyclical. A secular bull or bear market is a market that trends in a major direction up or down, respectively, for a long period of time, averaging 17 years. A cyclical bull or bear market is a market that trends up or down, respectively, within a secular bull or bear market and lasts a shorter time, one to four years.

For more than a century, the average secular bull market historically has lasted about 12 years, but the average secular bear market has lasted 21 years. Figure 8.1 illustrates bull markets and bear markets since 1900. The stock market does not go up in a straight line. There are periods of massive drawdowns and sideways markets. Identifying and avoiding those drawdown periods is the first step in market timing.

Figure 8.1 Secular market cycles over the last 111 years.

It is crucial for an investor to understand the stock market’s historical major cycles. One of the first key periods in the past 70 years was a secular bull market from 1949 through 1966 (see Figure 8.2), which averaged 14 percent gains each year. Buy-and-hold investors choosing stocks that mirrored the averages—then almost exclusively the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA)—succeeded during this period, especially if they could periodically invest money and reinvest dividends. While lacking the index funds of recent decades and the more commonly used S&P 500, Russell, or Wilshire indexes, investors tended to buy the large, well-known stocks included in the DJIA and were, in effect, linking their returns to the DJIA.

Figure 8.2 Dow Jones Industrial Average—secular bull market 1949–1966.

The gains stopped a couple of times, with two large drawdowns in 1962 and 1966. From 1966 to 1982, there was a period during which the market gave buy-and-holders very little, thanks especially to the 1973–1974 bear market and the long-term loss to inflation. Few long investors could withstand 40 percent drawdowns, wiping out years of small gains. Figure 8.3, illustrating the DJIA from 1955 to 2004, shows a superficially sideways market from the mid-1960s to mid-1980s.

Figure 8.3 DJIA 1955-2004: Sideways market, mid-1960s to mid-1980s.

Within this seemingly flat trading range are the sharp gains and losses of cyclical bull and bear markets, respectively. The cyclical bull and bear markets within the 1966 to 1982 sideways market are shown in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.4 The “sideways” 1966–1982 market had sharp gains and losses.

Source: Copyright © 2006–2008, Crestmont Research, www.CrestmontResearch.com.

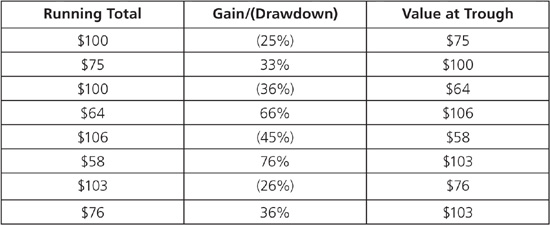

The ups and drawdowns of 1968–1982 reveal what was truly a secular bear market, as shown in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1. Magnitude of Gains and Drawdowns in 1968–1982 Secular Bear Market

Cyclical bear declines during this period totaled 146 percent, while cyclical bull gains equaled 211 percent, ending with a 3 percent gain against 50 percent inflation. Periodic investment and dividend reinvestment couldn’t make up for this dismal 16-year period, rightly called the “lost decade.”

By 2000, a 35- or 40-year-old, with a manageable mortgage, salary covering a 401(k), college fund, and discretionary cash for investing (admittedly a small segment of society, but perhaps the only one fitted for actual retirement someday) was 17 to 22 years old at the beginning of the 1982 bull market. This extraordinary 18-year bull market began with Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s breaking of inflation, the emergence from the recession, and a lengthy bull market in bonds (with declining interest rates—bond prices move in the opposite direction), along with confidence that reduced expectations of inflation.

Most investors knew precious little about the lost 1966–1982 period, and so those investors saw blue skies—with one brief drop in 1987 that only vindicated the new religion of “buy on the dips.” The index investor profited hugely from 1982 to 2000, with total returns of 1,100 percent and 2,600 percent, respectively, for the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq. The market rewarded those who stayed all-in with many annual double-digit gains of 20 to 25 percent for the S&P 500. However, investors had to withstand a 35 percent Nasdaq drop in 1998 and a 19 percent drop for the S&P 500, something human nature (and the Heebner example) would suggest didn’t happen.

In the late 1990s, individual investors entered the stock market in massive numbers. The investors now used the workplace 401(k) plans that increasingly replaced defined-benefit pension plans, with access to low-commission trades through online discount brokers. With the upward acceleration in market averages, the herd moved in. The 1987 crash, 1990 bear, and the 1998 Asian crisis and Long-Term Capital Management blowup were blips whose wakes only reinforced the mantra “buy on the dips.” By 1999, the young adults at the beginning of the 1982 secular bull were in their thirties, fully participating in the mad, final bull stampede—completely unprepared for the balloon’s long, slow deflation from 2000 to 2002. It seemed like that was simply a tech bubble—something that didn’t really affect well-known large caps, especially when the S&P 500 returned to pre-crash levels in 2007. But with the 2008–2009 crash, all was lost, and despite market rises after 2009, a lost decade-plus had not ended by 2011.

Sure, there were many years of strong returns, such as 2003 and 2009, and noncalendar year periods that did much better. But what really lost index investors the serious money was 2000–2002 and 2008. The investor in the S&P 500 index ETF (AMEX: SPY) from the beginning of January 3, 2000, to September 30, 2011, earned an abysmal –6.88 percent, a –0.61 percent compound annual growth rate. Index investors held on to their plummeting portfolios during some of the worst bear market crashes in history, with SPY falling 55 percent from its peak in October 2007 to its bottom in March 2009. The peak-to-valley change in price stunned many who watched their retirement savings cut in half. If they rode out 2000–2002 and stayed the course into 2007, they recovered. After that, though, the ride was seriously over. But the 55 percent loss—requiring a 123 percent gain to return to even—could have been avoided with a little market timing.

Figure 8.5 illustrates the two major drawdowns for the index investor who invested $100,000 in SPY from January 1, 2000, to October 1, 2011.

Figure 8.5 SPY: Two major drawdowns, January 2000–October 2011.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com. All charts referenced to AmiBroker are created using their tools and analysis, and by permission.

Figure 8.6 The reverse of Figure 8.5, showing the magnitude of drops.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Figure 8.6 emphasizes the magnitude of the 2000–2002 and 2008–2009 drops while Figure 8.7 is a month-to-month performance analysis of buying and holding throughout the 2001 to 2011 period.

Figure 8.7 SPY (S&P 500 ETF) buy-and-hold monthly returns, January 2000– September 2011.*

*Monthly results are for that individual month, while the right-hand column—the percentage gain or loss for the year—is cumulative (assuming an initial amount invested and rising and falling monthly).

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Notice the string of months that were consecutive losers, such as September 2008 through February 2009, equal in length from April 2002 through September 2002, but of massively greater magnitude. The more back-to-back losses an investor realized, the worse the negative compounding and drawdown, and the more portfolio destruction.

Recognizing secular markets is one thing, but recognizing the cyclical markets within them is what provides investors with ultimate gains. If investors can time these cycles—or even come close—they will have the ability to increase returns, reduce drawdowns, protect their capital, and stop buying antacids.

To demonstrate how large drawdowns can truly devastate a portfolio, look at Figure 8.8. It calculates the exponential impact of losses and how hard it is to overcome those losses as they grow. For example, if an investor loses 70 percent of a portfolio, it would take a 233 percent gain to return to the portfolio’s original value. The long-term would need to be very, very long indeed.

Figure 8.8 The impact of losses.

Source: Copyright © 2009 Crestmont Research (www.CrestmontResearch.com).

Figure 8.8 is a more dramatic representation of the concept discussed earlier in the chapter—that a 33 percent gain does not return to even a portfolio that’s dropped 33 percent (you would need a 50 percent gain). Avoiding losses is more important to preserving capital than participating in—or chasing the momentum of—gains.

Value investor Warren Buffett is cited for so much and so often that, if only half of what people said about him were true, he would be a deity. He, Benjamin Graham, and other noted pioneers of value investing have noted that, if you avoid permanent capital loss by buying cheaply—with a margin of safety—the gains take care of themselves. Buffett wrote in his hedge fund letters that he would likely do better than the market in bear markets and the same or a bit less in bull markets. Yet most investors chase gains, thinking that’s where the money is made. Where value investors and short-siders find agreement is that keeping the losses to a minimum is where you make the money. This doesn’t mean you’ll never have losses. It means you should avoid losing capital to such an extent that future returns won’t help you in restoring your wealth.

The market timing explained in this chapter provides the advantage of avoiding costly losses so that an attempted comeback will not be so burdensome. However, in order to understand market timing, you must first understand a small part of technical analysis.

As discussed in Chapter 7, technical analysis is based on the premise that market prices for a particular market, such as equities, reflect the fundamental driving forces of supply and demand. Just as market timing is misconstrued as somehow predicting the future, so too is technical analysis. Neither does, but they both follow the truth that prices are determined by supply and demand.

Most technical analysts will examine price action in the form of price charts. By studying charts over different timeframes, an investor can start to recognize patterns of market behavior and apply them toward market timing.

Contrary to popular belief, market timing is not predictive, but rather responsive to market shifts between bulls and bears. Hence, the investor is actually trying to be rational and use tools, rather than being distracted by emotion. Removing emotion is what market timing and technical analysis attempts to do.

Market timing does not care what products a company manufactures or if the CEO is your best friend. Instead, market timing cares only about the price action of the underlying security. Nevertheless, investors who understand risk also understand that making choices is unavoidable. Most of the time, the choices are between greater risk and greater potential reward versus lower risk and lower return. If an investor wants to achieve a maximum return, most of the time he or she will choose the greater risk for greater reward. However, the best investors know that, with premeditated calculation, they can achieve greater returns with less risk. This is really no different from long strategies to calculate potential reward for risk. It just uses market timing and technical analysis to do it.

Investors must consider that, if there are ways of maximizing risk-adjusted return or risk associated with the expected return by participating in bull markets while avoiding bear markets, then they must learn them, practice them, and see if they work. The use of a few technical indicators related to price action can achieve the desired results.

One important indicator is the moving average, as discussed in Chapter 7. A simple moving average is derived by calculating the stock’s average closing price over a certain number of periods. For example, a 50-day simple moving average (50 DMA) is the sum of 50 consecutive daily closing prices divided by 50. As the days move forward, the moving average is recalculated—that’s why it’s “moving.”

Moving averages smooth out price action, so the investor can better interpret a trend. If the moving average is going up, the trend is up. If two moving averages of different period lengths were to cross, it would indicate a change in trend.

A useful though ominous-sounding gauge measuring the shift between bull and bear markets is the “Death Cross.” The 50 DMA shows supply and demand for a stock reflected in its price over almost two months, while the 200 DMA does the same over almost seven months. A Death Cross occurs when the 50 DMA breaks below the 200 DMA. This shows that short-term demand is falling relative to longer-term demand and indicates a shift in market sentiment.

The importance of the 200 DMA can go beyond whether the 50 DMA crosses it. Some investors will sell their positions if they move below the 200 DMA, while others will not buy any trading below it. Because many technical investors will not trade in a security below the 200 DMA, it is considered a major support line. If the stock is above the 200 DMA, when the 50 DMA crosses below it, the investor heads for the exit. Moving averages are psychologically important whether applied to an individual security, an index, or a broad market—no matter what the investor is buying or selling.

How well do moving average crossovers—specifically the Death Cross—perform in interpreting the future action of a security or index? Figure 8.9 highlights the S&P 500 with a 50 DMA and 200 DMA. When the 50 DMA (dotted line) crosses above the 200 DMA (solid line), you can see the bull market uptrend. When the 200 DMA (solid) crosses above the 50 DMA (dotted), the bear market downtrend appears. Overall, the indicator provides a good reference for bullish up trends and bearish down trends.

Figure 8.9 S&P 500 using 50 DMA and 200 DMA.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

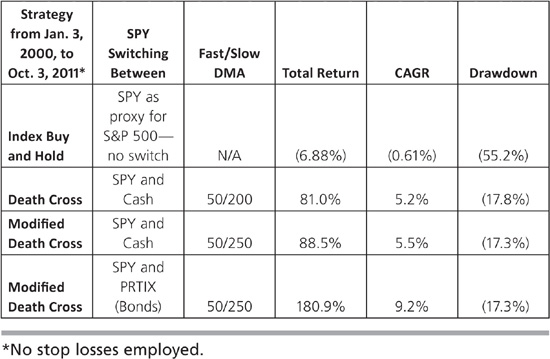

Recall that the index investor fully invested in this 2000–2011 period lost –6.88 percent for –0.61 percent CAGR. Using the 50 DMA–200 DMA Death Cross signal to move SPY to cash and back again yielded an 81 percent gain with a 5.2 percent CAGR and only a –17.8 percent drawdown. This demonstrates how even the simplest of technical analysis techniques can boost investment results.

In 2004 and 2006, there were brief periods called “whipsaws,” periods when the 50 DMA crossing the 200 DMA signaled the trader to exit the market, only to turn around and direct a return to the markets a few weeks later. Whipsaws are frustrating. Expanding the 200 DMA to 250 days can eliminate the whipsaws and their losses. Figure 8.10 represents a modified Death Cross using a 250 DMA instead of the 200 DMA.

Figure 8.10 Modified Death Cross: 250 DMA.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

In the modified Death Cross, from January 2000 to October 2011, the investor would have achieved a total gain of 88.5 percent or 5.5 percent CAGR and –17.3 percent drawdown.

Further performance improvements can be achieved, however. Instead of selling SPY and going to cash on the sell signal, sell SPY and buy an intermediate-term bond index, such as the T. Rowe Price U.S. Treasury Intermediate Fund, (NYSE: PRTIX) or the iShares Barclays 7–10 year Treasury ETF (NYSE: IEF), which only began trading in July 2002, limiting a complete comparison for 2000–2011. We’ll delve into this more in a bit, but for now, know that, when investors see a greater potential gain in bonds rather than stocks, large amounts of capital move from stocks to bonds. When enough of it does so, this reduces demand for stocks and the broad stock market declines. Switching to PRTIX on a sell signal grows the total gain to 181 percent with a CAGR of 9.2 percent. The drawdown remains at –17.3 percent.

Table 8.2 summarizes the performance from January 2000 to October 2011 of buying and holding the S&P 500 proxy SPY, the original 50 DMA × 200 DMA Death Cross, the modified 50 DMA × 250 DMA Death Cross, and the modified Death Cross switching to PRTIX instead of cash.

Table 8.2 Comparison of Results from Four Strategies

Figure 8.11 shows the equity curve and drawdown analysis of a portfolio that invested in the modified Death Cross switching between SPY and PRTIX from 2000 to October 2011. The equity curve demonstrates the growth of the account value starting with US$100,000. Figure 8.12 illustrates the drawdown analysis of Figure 8.11, but also showing percentage dips in account value when holding in the same period. Figure 8.13 shows the month-to-month results over the same time period.

Figure 8.11 Modified Death Cross: Switching between SPY and PRTIX.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Figure 8.12 Drawdown analysis of Figure 8.11, using percentage dips in account value.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Figure 8.13 Monthly results using modified Death Cross switching between SPY and PRTIX.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

You can see that the returns are much better and drawdown is superior for all Death Cross methods, especially the modified Death Cross switching between SPY and PRTIX.

Just as the switch between stocks and bonds is important, so too is the switch between small-cap stocks and large-cap stocks. Small-cap stocks serve as leading indicators of directional changes in the market, because investor cash flows into small caps rather than large caps when bond returns are unfavorable. However, because small caps have higher volatility—their relative illiquidity means prices rise and fall more in response to buying and selling volumes—the average investor thinks they are bigger risks than large-cap stocks, which don’t experience as much price fluctuation.

But volatility is not the same as risk. For the same reason investors act on emotion at drawdowns, they also tend to withdraw large amounts of capital from small caps when they believe those assets are more volatile and appear riskier. Detecting capital withdrawal from small caps can serve as an early indicator of overall market changes.

Several methods can detect the movement of capital from stocks to the bond market and back. A simple way to see the changes in momentum between the two is to divide a small cap stock ETF index by an intermediate-term bond ETF index and plot the result on a chart over time. By dividing the small-cap index by the bond index, the ratio of the two will fall faster as the small-cap index decreases in price (numerator decreasing) and bonds increase in price (denominator increasing). The movement of the resulting ratio indicates money flowing into equities when the stock/bond spread indicator is rising or money moving out of equities into bonds when it is falling.

To use this as a market timing indicator, a point of reference needs to be established where the spread indicator ratio is above the reference line and small-cap prices are increasing while bond prices are decreasing. This causes the indicator to rise faster. A moving average of the small-cap/bond spread indicator can provide this threshold, as shown in Figure 8.14.

Figure 8.14 Moving average of small-cap/bond spread indicators.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Unfortunately, using an unmodified spread indicator will result in numerous whipsaws, because the indicator fluctuates as stock and bond index prices change day to day. Figure 8.15 shows equity curves for the iShares Russell 2000 Index ETF (NYSE: IWM) of small-cap stocks, the iShares Barclays 7–10 Year Treasury ETF (NYSE: IEF), and the stock/ bond spread indicator in the bottom pane.

Figure 8.15 Stock/bond spread indicator: IWM (stocks) and IEF (bonds).

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

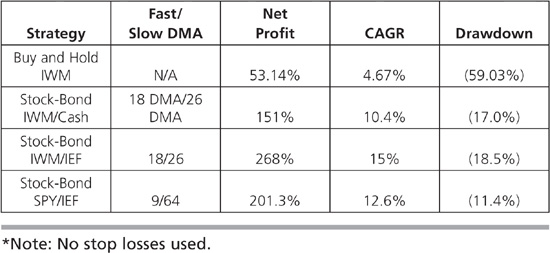

From July 2002 to September 30, 2011, the performance of switching between the Russell 2000 Index ETF (IWM) and cash yielded a 151 percent gain with a 10.4 percent CAGR and a –17 percent drawdown. Overall performance can be enhanced by switching to bonds via IEF when the timing indicator issues a sell signal of IWM. Switching between IWM and IEF yields a total return of 268 percent with a CAGR of 15 percent and drawdown of –18.5 percent. This contrasts with a buy-and-hold result of IWM for the same time period of 53.1 percent total return, 4.7 percent CAGR, and –59.0 percent drawdown.

Figure 8.16 shows the equity curve for a portfolio that invested in the stock/bond spread indicator from 2002 to the end of September 2011 starting with $100,000, Figure 8.17 shows the month-to-month results of this system over the same time period, and in Figure 8.18, we see the profit distribution of the trades. Notice how there are more winners than losers, and that the bulk of the losses are moderate and acceptable.

Figure 8.16 Stock/bond spread indicator: equity curve.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Figure 8.17 Stock/bond spread indicator: monthly returns.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

Figure 8.18 Stock/bond spread indicator: profit distribution.

Source: AmiBroker, www.AmiBroker.com.

A stock/bond spread indicator can be formed with other major market indexes as well. Table 8.3 summarizes the performance of a buy and hold strategy for IWM, the IWM/cash switch indicator, the IWM/IEF switch indicator, and the SPY/IEF switch indicator (using a short 9 DMA and longer 64 DMA, which research shows as optimal for this switch indicator).

Table 8.3 Comparing Results from Four More Strategies over a Period from June 3, 2002 to September 30, 2011*

Market timing does not care about emotions. It only cares how the market performs. Measuring how the market performs and creating a system around the data creates a trader’s edge. That edge produces success.

Part 1 showed what to look for. And Part 2, ending with this chapter, shows how and when to act on it. The following and final chapter gives the research supporting the practical advice in this book—but not before our offer to you on market timing.

In addition to this chapter’s market timing signals, there is another very useful proprietary signal. This market composite signal is derived from several different signals generated on different markets. Combining them into a composite yields still stronger returns with less drawdown, eliminating a number of whipsaws and capturing the majority of intermediate-term trends. By optimizing over a series of various buy and sell combinations, when any one signal goes on a sell, the composite signal will generate a sell. Conversely, when all go on a buy, the composite signal generates a buy order. To receive the buys and sells generated by the composite signal free, please visit our website at www.deljacobs.com.